Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Group Limited (formerly called Woolworths Limited) [2020] FCAFC 162

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Appellant | ||

AND: | WOOLWORTHS GROUP LIMITED (ACN 000 014 675) (FORMERLY CALLED WOOLWORTHS LIMITED) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

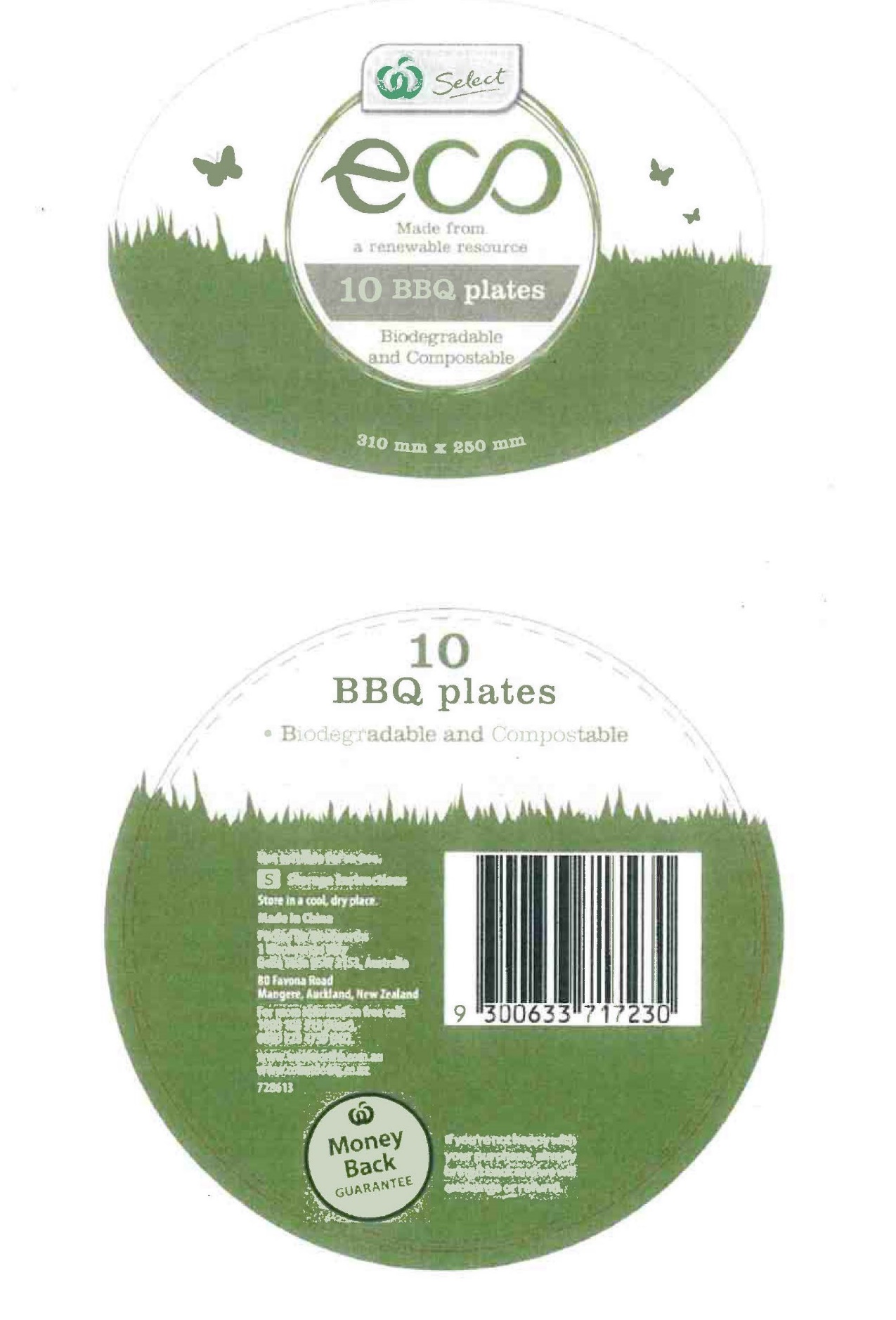

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of and incidental to the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 This appeal concerns the promotion and sale of certain disposable products by Woolworths Group Limited (formerly called Woolworths Limited) (Woolworths), a major Australian supermarket chain.

2 In the period between November 2014 and November 2017 (the relevant period), Woolworths sold in its Australian supermarkets and through its online store a range of disposable cutlery and crockery under the label “Select Eco” (the products).

3 The disposable cutlery comprised knives, forks and spoons and the disposable crockery comprised a variety of plates and bowls.

4 The Select Eco cutlery was made of Crystallised Polylactic Acid (CPLA). CPLA is a material made from polylactic resin which, in turn, is made from fermented corn starch, talc (or chalk) and other additives.

5 The Select Eco crockery was made of bagasse (as to 98.8%) and certain chemicals. Bagasse is a fibrous matter that remains after sugarcane or sorghum stalks are crushed in order to extract their juice.

6 Both CPLA and bagasse are non-toxic organic materials and, upon decomposition in an appropriately managed environment, both may be used as a soil additive.

7 The packaging in which the products were sold featured the statement “Biodegradable and Compostable”. That packaging also contained the statement: “Made from a renewable resource”.

8 An example of the packaging in which the products were sold is the packaging for the 10 BBQ Select Eco plates set which is reproduced below:

9 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) considered that, by offering for sale and selling the products in packaging which featured the statements specified at [7] above and which resembled the get-up typified by the packaging reproduced at [8] above, Woolworths represented to consumers that the products would biodegrade and compost within a reasonable time when disposed of:

(a) Using domestic composting; or

(b) In circumstances ordinarily used for the disposal of such products, including conventional Australian landfill

and thereby engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). We shall refer to these alleged representations as “the par 4 pleaded representations”.

10 Accordingly, on 2 March 2018, the ACCC instituted a proceeding against Woolworths in this Court in which it claimed declarations, injunctions, pecuniary penalties, publication orders and costs in respect of alleged contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL constituted by Woolworths’ conduct in offering for sale and selling the products in the packaging which we have described at [7] and [8] above.

11 After a four day trial in September 2018, the learned primary judge dismissed the ACCC’s proceeding with costs (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2019] FCA 1039).

12 The ACCC appealed her Honour’s decision and by this judgment, we determine that appeal. For the reasons which follow, we have decided to dismiss the appeal with costs.

The Issues at Trial

13 The ACCC articulated its case in the Amended Concise Statement filed by it on 17 April 2018 (ACS). Woolworths answered that case in the Concise Response filed by it on 2 May 2018.

14 After describing the products, the packaging in which those products were sold and the suppliers and manufacturers of those products to Woolworths, the ACCC set out the par 4 pleaded representations (at par 4 of the ACS).

15 The ACCC then contended that the par 4 pleaded representations were representations as to future matters (par 13 of the ACS) and that Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making those representations (pars 5 to 10 and 13 of the ACS). The ACCC also argued that, in the circumstances of this case, s 4 of the ACL was engaged (par 13 of the ACS) with the consequence that the par 4 pleaded representations should be taken to be misleading.

16 The ACCC also relied upon an alternative case which it pleaded in pars 11 and 14 of the ACS in the following terms:

11. Further or alternatively to paragraphs 5 to 10 above, the Environmental Claim Representations [being the representations pleaded at par 4 of the ACS] were false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive because the Select Eco Products were not biodegradable and compostable within a reasonable period of time when disposed of:

i. using domestic composting; or

ii. in circumstances ordinarily used for the disposal of such products, including conventional Australian landfill.

…

14. Further or alternatively to paragraph 13, the Environmental Claim Representations were false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive for the reasons set out in paragraph 11 above.

17 In addition to relying upon s 18 of the ACL, the ACCC alleged that, by making the par 4 pleaded representations, Woolworths:

(a) Made false or misleading representations that the products were of a particular quality, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL;

(b) Made false or misleading representations that the products had performance characteristics, uses or benefits, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(c) Engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics or suitability for purpose of the products, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

18 At all relevant times, ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g), 29(2), 29(3) and 33 of the ACL were in the following terms:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3–1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

Note: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5–3.

…

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

…

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation of a kind referred to in subsection (1)(e) or (f), the representation is taken to be misleading unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the representation is not misleading; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the representation is not misleading.

…

33 Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of goods

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this section.

19 Woolworths admitted making the statements which we have set out at [7] above on the packaging in which the products were sold. However, it denied that those statements conveyed the par 4 pleaded representations or the representations pleaded at par 11 of the ACS. Woolworths also denied that those statements constituted representations with respect to future matters and, for that reason, also denied that it was obliged to make any enquiries to substantiate the truth of those statements. It contended that the statements in question were statements about the characteristics or inherent features of the products and, as such, were statements of present fact. It argued that all of the products were, in fact, biodegradable and compostable and that, for that reason, the statements which it made about them were true.

20 Woolworths also contended that, if, contrary to its primary argument, the statements on the packaging were representations as to future matters, it had reasonable grounds for making them and, for that reason, did not contravene s 18 of the ACL.

21 Woolworths also denied that it contravened any of s 29(1)(a), s 29(1)(g) or s 33 of the ACL by offering for sale and selling the products in the packaging described at [7] and [8] above.

The Judgment of the Primary Judge

22 The primary judge concluded that the ACCC had failed to prove that, by the labelling on the packaging of the products, Woolworths made the par 4 pleaded representations or the representations alleged in par 11 of the ACS. Her Honour found that, by that labelling, all that Woolworths represented was that two of the inherent features of the products were that they were biodegradable and compostable, and nothing more. The primary judge also found that these representations were statements of present fact, were not representations with respect to future matters and were true. Accordingly, her Honour dismissed the ACCC’s case. These findings are her Honour’s primary conclusions and constitute the ratio decidendi of her decision.

23 The primary judge also considered the question of whether, if, contrary to her primary findings, the relevant statements on the packaging of the products did constitute representations in the terms alleged by the ACCC at par 4 of the ACS and were also representations as to future matters, the ACCC had proven that Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making those representations. Her Honour found that, if she assumed those two matters (contrary to her primary findings), the ACCC had proven that Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making the par 4 pleaded representations.

24 The primary judge also addressed the ACCC’s alternative case (as to which, see pars 11 and 14 of the ACS) upon the assumption that she was wrong in her primary conclusions. Had it been relevant, her Honour would have concluded that the par 11 representations were not misleading or deceptive or false because, had they been made, they would have been true.

25 At [13]–[49] of her Reasons, the primary judge described the products, explained how Woolworths came to purchase and offer those products for sale and described where and how those products were displayed. Her Honour noted that the products were sold both online and in store.

26 At [43], her Honour described the positioning of the products in Woolworths’ stores in the following terms:

… They were located in an aisle and on shelves amongst other disposable crockery and cutlery products, serviettes and other products intended for use in eating and drinking. They were displayed close to Woolworths’ “Essentials” range of similar products, including paper crockery and plastic cutlery, and also appear, from the photographs, to be located amongst a number of other brands of mostly plastic products.

27 The primary judge noted (at [46]) that there were no instructions on the packaging of the products on how to dispose of them nor was there any indication as to whether consumers needed to do anything to the products before disposing of them.

28 At [51]–[77], the primary judge outlined the issues in dispute and briefly addressed each party’s submissions as to those issues.

29 At [57], her Honour noted that the ACCC’s allegation that the products were represented as being capable of biodegrading and composting “… within a reasonable period of time …” was an allegation of implied representation. The ACCC accepted that the words “… within a reasonable period of time …” did not appear on the packaging but nonetheless asserted that those words should be implied as part of what was represented when proper regard is paid to the context and circumstances in which the products were sold.

30 At [78]–[144] of her Reasons, the primary judge identified the relevant statutory provisions (ss 4, 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL) and the relevant legal principles upon which she proposed to act.

31 At [85]–[136], her Honour discussed a number of authorities concerning “future matters”. She did so by reference to three aspects which she mentioned at [85] thus:

There are three aspects of the applicable principles to be considered:

(a) what is meant by a “representation with respect to any future matter” in s 4;

(b) what is the onus borne by the representor for the purposes of s 4; and

(c) if that onus is discharged, what the applicant must prove, in relation to reasonable grounds.

32 At [86], her Honour said that she accepted Woolworths’ submissions as to the meaning of the phrase “representation with respect to any future matter” (as to which, see [54] of the primary judge’s Reasons). She also noted that the approach which she took to the meaning of that phrase is consistent with the approach taken by Gleeson J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 992 (Kimberly-Clark) at [276]–[286] esp at [285].

33 At [87]–[91], her Honour said:

Woolworths submits the phrase is concerned with:

… representations, such as predictions, promises, forecasts and opinions as to future events where the factual matter represented is not capable of being true or false at the time the representation is made (because it lies in the future).

(Original emphasis.)

The ACCC submits that language is too narrow, and does not accommodate authorities which have applied s 4 to situations where there is “a representation of likely performance”. It also relies on descriptions such as whether the representation has “an aspect of futurity about it”, referring to the observations of Foster J in GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1; 133 IPR 190.

Woolworths’ submissions should be accepted. They reflect the text of s 4, when seen in its context, and having regard to its purpose. Those are the governing principles for construing the phrase: see my summary of the relevant authorities in Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 228 LGERA 255 at [44]-[46].

However, some preliminary observations should be made. The purpose of s 4 is facultative: it does not itself impose any separate or different liability. The prohibitions remain in the operative provisions in Ch 2 of the ACL. In circumstances to which it applies, s 4 imposes an evidentiary onus on a representor, but maintains the legal onus on the party alleging a contravention of Ch 2 of the ACL: see in particular confirmation of this in s 4(3)(b). Conversely, s 4(3)(a) makes it clear that compliance with the evidentiary onus does not necessarily result in rejection of the alleged contravention: rather, it simply places the party making the allegation of contravention in the usual position of being required to prove the allegation on the balance of probabilities. As Foster J said in GlaxoSmithKline at [137]:

It is an evidentiary provision only and does not reverse the legal or persuasive burden which the applicant bears of establishing that reasonable grounds for making the representations did not exist (see also Crowley v WorleyParsons Ltd [2017] FCA 3 at [71]).

Where the deeming effect of s 4(2) is displaced by the adducing of “evidence to the contrary”, then the ultimate onus of proving the absence of reasonable grounds will remain with the party alleging contravention: here, the ACCC.

34 The primary judge then referred to certain passages in McGrath v Australian Naturalcare Products Pty Ltd (2008) 165 FCR 230 (McGrath) at 274–277 [166]–[176] and at 277–284 [177]–[197] (per Allsop J, as his Honour then was); Thompson v Mastertouch TV Services Pty Limited (1977) 15 ALR 487 at 495 (per Franki J); and Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (Global Sportsman) at 88 (per Bowen CJ, Lockhart and Fitzgerald JJ).

35 At [97]–[105] of her Reasons, her Honour then said:

I consider this was the kind of construction of the term “future matter” that was adopted by Nicholas J in Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 227; 113 IPR 11. The facts in Samsung concerned television commercials and related internet, cinema and point of sale advertising undertaken by LG to advertise and promote a range of 3D televisions that employed a particular form of 3D technology. Samsung alleged the advertising contravened s 18 and s 29(1)(a) of the ACL. Some of the representations conveyed by the advertising were said to be about “future matters”. For example, as Nicholas J explained at [82], one advertisement was alleged to convey a representation that “conventional 3D TVs can only be viewed in the dark” and also to convey a representation that “a person watching conventional 3D TV will have to do so in the dark”, which Samsung alleged to be false or misleading.

The parties referred the Court to [85] of his Honour’s reasons, but what his Honour said at [83] is also important:

Most of the representations which Samsung alleges were conveyed by the TVCs consist of representations about the performance characteristics of conventional 3D TVs and LG Cinema 3D TVs. Each of these representations is pleaded as, and in substance is, a statement of fact. Whether or not the TVCs also convey representations with respect to future matters depends upon the proper characterisation of the representations actually conveyed.

At [84], Nicholas J then set out his understanding of the operation of s 4:

The expression “future matter” is not defined by the ACL. The same expression as used in s 51A of the TPA, was also not defined. However, when read in context, the expression is not hard to understand. A “representation with respect to any future matter” for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL and, before it, s 51A of the TPA, is a representation which expressly or by implication makes a prediction, forecast or projection, or otherwise conveys something about what may (or may not) happen in the future.

At [85], Nicholas J distinguished between a statement about the “character” of a representation and conclusions that might be drawn from that character:

It is important to distinguish between the representation actually conveyed by a product advertisement and what conclusions might be drawn from it. A person may reasonably infer from the statement “this is a 3D TV” that he or she will be able to view the TV in 3D at some time in the future. However, this does not change the fundamental character of the representation which is one made with respect to an existing state of affairs. In this case I am satisfied that none of the representations conveyed by the TVCs can be characterised as having been made with respect to a future matter.

Then at [86], Nicholas J distinguished the authorities about health and therapeutic products (referring specifically to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1161; 95 FCR 302 which concerned an electrified mat, represented to have particular health effects once a person slept on it). His Honour relevantly said:

The representations made, as found by his Honour, were broadly to the effect that as a result of its emission of negative ions, the mat benefits the health of persons who sleep on it. That decision, and others concerned with the efficacy of therapeutic products that are said to offer health benefits when administered or used as directed, are distinguishable from the present case. In such cases the representation is made with respect to a future matter in that the consumer is told that if he or she uses the product a particular health benefit will be obtained at some time in the future. I do not think it is possible to tease any such representation out of any of the TVCs in issue in this proceeding.

That conclusion is consistent with his Honour’s interpretation of the term “future matter” as involving a prediction, forecast or projection.

I accept Woolworths’ submissions that this construction of “future matter” as involving a prediction, forecast or projection is also consistent with the concept of “reasonable grounds”, present in both s 4 and in s 51A. Representations about the future inherently involve an opinion or prediction of some sorts, and thus involve the disclosure of a (present) state of mind by the representor. The purpose of the “reasonable grounds” criterion is to require an appropriate basis for the state of mind (being the opinion or prediction) disclosed by the representation. Whether or not there were reasonable grounds for the representation about what might happen in the future would be relevant to establishing the character of the representation as misleading, or false, or deceptive. This point is, with respect, well made by Rares J in Ackers v Austcorp International Ltd [2009] FCA 432 at [359] and [363]:

When, as here, the representation is an assurance of an income stream over a period, it has the character of a prediction or forecast. It is about a future state of affairs which can only be verified by future experiences over the term of 10 years. Such a representation has a character distinct from that of a statement about rent which is currently due and payable. The latter is a statement with respect to an existing or present state of fact. The maker of a representation with respect to a future matter cannot know, however sure he or she is, that it will come true…

…

Section 51A recognises that representations with respect to a future matter can be objectively misleading or deceptive if the prediction turns out in due course to be wrong. If s 52 operated in that unqualified way, because of the consequence of future error it would create liability for every representation about future matters, however responsibly the representation may have been made at the time. So, s 51A ordinarily affords a representor an important protection in making such a wrong prediction if, when making it, the representor had reasonable grounds for doing so.

Despite the submissions made by the ACCC, I do not consider this construction is in substance any different to a construction which uses the language of “likely performance” of a product. A “prediction” may be a form of representation about “likely performance”. So might a “forecast”. Altering the language used in this way does little to elucidate the meaning of the phrase in s 4.

The ACCC gives a large number of examples in its written closing submissions (at [71]-[80]) to support the proposition that the term “future matters” extends to the “likely performance” of a product. As I understand it, that proposition is said to be applicable to the present case because the labelling “biodegradable and compostable” is said by the ACCC to involve a representation as to the “likely performance” of the cutlery and the dishes following their disposal. Aside from the authorities to which I refer below, I do not consider any of the authorities on which the ACCC relies suggest a meaning of the phrase “future matter” which is different from the meaning of a prediction, forecast or projection, and that they do not suggest anything other than that where a “future matter” is involved, there is an opinion being expressed by the representor about what will happen at some future time.

36 At [106]–[112], the primary judge reviewed several authorities in which representations as to the likely performance of a product were under consideration.

37 At [113]–[136], her Honour discussed the correct interpretation of s 4 of the ACL, including, in particular, whether, in order for a representor to have reasonable grounds for making a representation with respect to a future matter, the representor must actually rely upon the information, facts or circumstances said to constitute the reasonable grounds (as to which, see Sykes v Reserve Bank of Australia (1998) 88 FCR 511 (Sykes) at 513–515 (per Heerey J)). The primary judge favoured this view: See, for example, the observations which she made at [129]–[130], where she said:

Most importantly in my opinion, the text of s 4(1), read with s 4(2), clearly supports the position for which the ACCC contends. Subsection (1) is concerned with whether the person making the representation “does not have” reasonable grounds. The only sensible way to understand that phrase is that at the time of making the representation, the representor herself or himself, or through its corporate actors, “had” – as in fact possessed – a basis which can be objectively described as reasonable, for what was represented. The text directs attention to the information which in fact provided the basis for the statements or conduct. It does not direct attention to whether there were reasonable grounds for the making of the representation. Rather, the text focuses on whether the representor “had” such grounds.

In that sense, the debate over whether the representor needs to adduce evidence of “reliance” might be something of a distraction from the statutory text of s 4. Reliance might be implicit, or inferred. Using the language I have used above in an attempt to explain the meaning of the provision as I understand it, the question asked by the text of s 4(1) (read with the effect of s 4(2)) is:

Did the person who made the representation about a future matter possess information which, assessed objectively, gave that person a reasonable basis for making the representation?

38 At [137]–[144], the primary judge discussed a number of authorities which addressed particular points arising out of the ACCC’s alternative case (ie its case as pleaded in pars 11 and 14 of the ACS).

39 At [145]–[299] of her Reasons, the primary judge discussed and determined what representations Woolworths had made by the wording placed on the labels on the packaging of the products.

40 At [148]–[155], her Honour discussed the evidence of Professor Clarke, Mr Nolan and Mr Leake as to the meaning of the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable”. Her Honour preferred the evidence of Professor Clarke and Mr Leake to that of Mr Nolan. That evidence is recorded by the primary judge at [149]–[150] in the following terms:

Professor Clarke’s evidence was:

The terms “biodegradable” and “compostable” refer to inherent properties of a given material. At any time, scientists can measure how much of a material can be consumed by organisms within a set timeframe (and thus how much of the material will biodegrade) to demonstrate the property of the material.

By way of illustration of the concept of “inherent properties”, consider a piece of wood. Wood is combustible. This is an inherent property of the material. Similarly, iron is corrodible. This is an inherent property of the material. I could conduct simple experiments to demonstrate those existing inherent properties by, for example, burning the wood or leaving iron in salty water.

Mr Leake’s evidence was:

Compostability and biodegradability are inherent characteristics of all organic materials. A hardwood chip of, say, Red Gum is inherently biodegradable. It may take many years to completely disappear in soil, but this does not change the fact that it is biodegradable. Although it will survive composting almost unaltered, except that its colour will darken and there will be a reduction of lower molecular weight components, it plays a useful role in composting by providing structure and aeration and, in my view, is therefore also inherently compostable.

41 At [156], her Honour said:

In this proceeding, despite the broader descriptions found in some of the authorities to which I referred in [Shape Shopfitters Pty Ltd v Shape Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 865; (2017) 124 IPR 435] at [100]-[101], it appears to be common ground that the relevant section of the public can be appropriately described as consumers, and indeed more specifically as consumers shopping for disposable cutlery and dishes, who may have been doing so either in a Woolworths store during the relevant period, or online during the relevant period. The parties are then not agreed about what attributes these consumers should be found to have.

42 At [157]–[166], the primary judge made a number of findings as to the attributes that the relevant class of consumers should have.

43 At [158], her Honour concluded that the dominant message of the labelling on the packaging of the products was that those products were different from their plastic counterparts, in that they were more environmentally friendly because they were made of organic material and were capable of breaking down in landfill and capable of being composted.

44 At [159]–[160], the primary judge identified some attributes of the ordinary reasonable members of the relevant class of consumers. At [160], her Honour said that there would have been a cross-section of consumers including:

(a) Those in a rush to buy disposable cutlery and/or dishes for a function or event;

(b) Those consciously looking for environmentally friendly products;

(c) Those planning far ahead for future events or purchasing disposable cutlery and/or dishes to have at home “just in case”;

(d) Those browsing and undecided about purchasing disposable cutlery and/or dishes at all;

(e) Those who knew about composting, and those who did not;

(f) Those who practised composting, and those who did not; and

(g) Those who had an accurate understanding about what “biodegradable” means, and those who did not.

45 At [162]–[163], her Honour said:

Woolworths spent proportionally more time in its closing submissions on the characteristics to be attributed to the reasonable consumer than did the ACCC. I accept the following matters submitted by Woolworths:

(a) these were not expensive products and so were not products consumers would have spent a long time pondering over;

(b) the placement of the Products with other disposable dishes and cutlery, including plastic products, meant consumers would have interpreted the labels “biodegradable and compostable” in part by comparison with plastic products and would have understood the Products were different to plastic products;

(c) due to the prevalence of recycling facilities and practices, consumers would have known about the separation of some kinds of waste so that it does not end up in landfill, but would also have understood most household waste ends up in landfill or a “rubbish dump”;

(d) due to the general publicity about waste management, recycling and waste disposal, consumers would have understood that rubbish can last for a very long time in the environment and that it is desirable to reduce waste remaining in the environment;

(e) most consumers would have had some understanding that composting is a specific method of disposing of organic waste, and that it can be done at home;

(f) most consumers would have understood that if waste products are composted, they are not going into landfill or a “rubbish dump”;

(g) most consumers would have known compost is a useful product for the garden; and

(h) most consumers would have understood “biodegradable” to mean something different from “compostable”.

To this I add the following findings:

(a) Most consumers may not have had a technical or deep understanding of the meaning of “biodegradable”, but would at least have understood, from the prefix “bio” and the verb “degrade”, that it has something to do with organic material, and the breaking down of material.

(b) Relatively to other disposable dishes and cutlery, the Products had a price premium: consumers would have expected they were paying a price premium because the products were more environmentally friendly in terms of how they could be disposed of.

46 At [164], the primary judge held that it was not only consumers who were actively engaged in home composting or composting-like disposal methods who would have been affected or influenced by the use of the word “compostable” on the labelling on the products. Her Honour held that that statement would have spoken to a wider class of consumers. In that paragraph, her Honour said:

… it would have spoken to consumers who were to some extent ill-informed or confused about the circumstances necessary for compost to be produced, and for the composting process to occur. This view does not affect my ultimate findings in Woolworths’ favour, and indeed reinforces my opinion that the phrase as a whole – and the words within it – would be understood as speaking to the inherent qualities or capacities of the products in a general way.

47 At [165], the primary judge held that the word “compostable”, especially when used in combination with the word “biodegradable”, spoke to all those consumers who have some concerns about environmental matters. At [166], her Honour held that the word “compostable” would have had a particular resonance with those consumers who were actively engaged in home composting.

48 At [167]–[206] of her Reasons, the primary judge set out her findings as to the representations that were conveyed by the use of the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable” on the labels affixed to the packaging of the products and her reasons for making those findings. In these paragraphs of her Reasons, her Honour also addressed and made findings as to whether the representations, as found, were with respect to future matters.

49 At [167]–[175], the primary judge said:

Determining what representations were made

In Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 358 ALR 683 at [74], Perram J said (Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreeing):

Whether particular conduct results in a representation is a question of fact ‘to be decided by considering what [was] said and done against the background of all surrounding circumstances’. Further, where the question is whether a representation has been made to a large group of persons such as, as here, potential purchasers, the issue of whether the representation has been made ‘is to be approached at a level of abstraction not present where the case is one involving an express untrue representation allegedly made only to identified individuals’: as to both propositions see Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45; 169 ALR 677; 46 IPR 481; [2000] HCA 12 (Campomar) at [100]-[101]. The primary judge expressly recognised the first of these principles at [338] and observed that those circumstances included ‘the circumstances in which the respective products are sold to the public’.

The question is: objectively, what was conveyed to consumers with the attributes I have described above by the use of the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” in the context in which it appeared on the Products, taking into account how and where they were displayed?

In Campomar at [105] the High Court put the question thus:

The initial question which must be determined is whether the misconceptions, or deceptions, alleged to arise or to be likely to arise are properly to be attributed to the ordinary or reasonable members of the classes of prospective purchasers.

It may be accepted, as the ACCC submits, that “biodegradable and compostable” is a whole phrase and care should be taken not to break it up. Further, I accept, as the ACCC submits, that in a supermarket context, there is likely to be something of an “intuitive” reaction from shoppers to the labelling, so that no overly scientific approach should be taken to how the words “biodegradable” and “compostable” would be understood by reasonable consumers.

However, it is also true there were two words used in the phrase, and the Court must decide how a reasonable consumer would, in the circumstances, have understood them when they were used in the context of a single phrase on the labels of the Products. That does depend to some extent on how a reasonable consumer would have understood each of the words singularly, as well as in combination.

In my opinion, it is of some significance that the words on the labelling were adjectival, with the suffix “-able” on them. That is not to suggest consumers would have taken some grammatical approach to ascertaining their meaning, far from it. Rather it is to say that, intuitively, consumers would have understood by the adjectival form that the words were describing the qualities of the Products, or the characteristics of the Products. I find that this phrase, expressed as it was in adjectival form with the suffix “-able” attached, would have been understood by consumers in the same kind of way as the word “recyclable”, which is used in very similar contexts.

It was common ground between the parties that the word “recyclable” is found on labels, and on packaging. The parties differed about the utility of the analogy to the impugned phrase in this proceeding, but I consider there is a strong analogy. The adjective “recyclable” is readily understood by the reasonable consumer as indicating the capacity of a product to be recycled, or put through a recycling process. It is readily understood as an indicator to consumers about how they are able to dispose of a product that has such a descriptor on it. It is a word that has become extremely common in product labelling, not just as part of environmental messaging, but including that context.

I find the reasonable consumer would have understood the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” in the same way: as a description of the capacity of the Products to be disposed of in a particular way because of their inherent qualities; that is, that the Products were “capable” of biodegrading and “capable” of being composted.

The recycling comparison is a good one, and one I am satisfied reasonable consumers would readily make. Consumers understand that recyclable products will only in fact be recycled if they are treated appropriately in a recycling facility. The reasonable consumer understands that fact does not alter a product’s state, or inherent qualities, as a “recyclable” product, but it does affect whether that capacity or capability, and benefit to the environment, comes to fruition. I am comfortably satisfied that during the relevant period, consumers would have understood this distinction.

(Emphasis in original)

50 As to the meaning of “biodegradable”, when used on the Select Eco product packaging, her Honour made the following findings (at [177]–[179]):

Biodegradable

I find that a reasonable consumer would have understood the basic meaning of “biodegradable” as able to be broken down, because of what the Products were made of. I find the reasonable consumer would have understood that the Products were not made from ordinary plastic. The reasonable consumer would have understood this from the use of the adjectival description, from looking at the other labelling (for example, “Made from a renewable resource”) and from the environmental messaging conveyed by the use of green colours, the word “Eco” and images of grass and butterflies. The labelling itself did not indicate what the Products were made from, and I find the reasonable consumer would not have understood any more about the make-up of the Products than that they were not made from ordinary plastic, and that this meant they were made from organic materials.

I am not satisfied a reasonable consumer would have understood that the breaking down process is performed by micro-organisms, or that variations in conditions in landfill or other environments where the waste is placed might accelerate or slow down that process, or the length of time that process might take. In my opinion these are more scientific or technical aspects of the meaning of “biodegradable” that would not have been understood by the reasonable consumer when she or he saw the word used adjectively on a product label in a supermarket (or while shopping online).

As I have noted above, I find that the reasonable consumer would have understood the word “biodegradable” in the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” to mean that the Products were capable of breaking down, or biodegrading, because of what they were made of: that is, because of their inherent qualities.

51 As to the meaning of “compostable”, when used on the same packaging, her Honour made the following findings (at [180]–[187]):

Compostable

I find a reasonable consumer would have understood that the term “compost” refers to organic materials, and that compost can be made by placing organic materials together in a pile, a container or a bin, and that the kinds of materials which are put into compost are often food scraps but also other materials such as paper and plant material.

I find that the word “compostable” was likely to be understood by the reasonable consumer as referring to something that was a useful product for the garden, and for healthy soil, so that consumers would have understood that the Products were capable of being turned into something that could be used in the garden or to improve soil quality.

I find that consumers would have understood that if a product is “compostable”, that is a different and separate quality from being “biodegradable”. They would have understood that from the fact the two different words were used in the phrase on the label of the Products, and from what I have found to be the likely general understanding of what it means to describe a product in each of those ways.

I am not satisfied that a reasonable consumer shopping for disposable dishes and cutlery would have had any detailed understanding of composting processes. I find that most consumers may have seen, or come to know about, facilities such as home composts and compost bins, but I do not consider there is any evidentiary basis to conclude that consumers looking at the Products either in a Woolworths store or online during the relevant period were likely – as a general proposition – to understand how the composting process works or have any experience with how it works. There would certainly have been some consumers who did, and as I have found above, that may have given such consumers a particular interest in the Products. There is insufficient evidence to find that the majority, or even a significant number, of consumers looking at the Products in Woolworths’ stores or online would have had any real knowledge about composting processes.

However, I do not consider these findings affect one way or the other the correct and appropriate conclusion on the evidence about the nature of the representations made by Woolworths on the labelling of the Products. Whether or not the ordinary consumer had knowledge of the composting process would not, in my opinion, have affected how the consumer would have understood what was being represented by the use of the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” in the overall context of these Products, including the overall packaging. Experienced composters or not, I find the consumer would have understood the phrase as meaning no more than that the products were capable of biodegrading, and were capable of being composted – in the same way the consumer would have understood the use of the description “recyclable” to refer to the capacity of a product to be recycled, no matter what the consumer’s level of knowledge (sophisticated or otherwise) about how recycling programs operate, or what the different processes are for recycling different kinds of products.

These conclusions are supported by the opinion of Professor Clarke, in that part of his report responding to some of the ACCC’s evidence. At [97] of his report, Professor Clarke stated:

I have read the affidavit of Ms Deirdre Ellen Griepsma dated 23 July 2018. In response to that affidavit I make two points:

(a) Whether a material is biodegradable or compostable is a property of the material - not a property of how it is handled. As long as a material is biodegradable and compostable under suitable conditions, that material is biodegradable and compostable.

Earlier in his report, at [83], Professor Clarke also stated the following:

Where biodegradable or compostable material is placed in landfill, it will eventually degrade. However, given the heterogeneous nature of landfill conditions referred to above, that material may degrade quickly (if in the presence of moisture and other degrading organic material) or much more slowly (if it is dry). Even if that material degrades only very slowly in such conditions, it remains properly described as “biodegradable” or “compostable” - in contrast to other materials which are placed in landfill (and which are clearly not “biodegradable” or “compostable”), such as polyethylene, polypropylene, glass and other synthetic substances. The availability of ideal conditions in which a biodegradable or compostable material will degrade or compost is not necessary for that material to have the inherent property of biodegradability or compostability, or to be properly described as “biodegradable” or “compostable”.

These conclusions are also supported by the evidence of Mr Leake, which I have set out at [150] above.

(Emphasis in original)

52 At [188]–[191], the primary judge made the following findings as to the meaning of the whole phrase “biodegradable and compostable” in the context in which it was used on the product packaging:

What representations were conveyed by the whole phrase, in its context?

During the relevant period, I find that the representations conveyed to the reasonable consumer either shopping in a Woolworths store or online, and looking at the labelling on these Products, in the packaging in which they were presented, was that the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” was describing a capacity or capability that each Product had. The representations were that the Products were capable of biodegrading, and also capable of being turned into compost. Consumers would have understood that the Products needed to be disposed of and treated appropriately for those capacities or capabilities to be realised, and for any environmental benefit to come to fruition.

I reject the propositions implicit in the ACCC’s case in this proceeding that there is any more to be implied into the statements on the labels than what I have found above.

Contrary to the ACCC’s submissions (see for example [11] of its closing submissions) I do not accept that the reasonable consumer would have understood the labels on the Products to convey the impression that if placed in landfill (or a “rubbish dump”) the products would both biodegrade and turn into compost. I am satisfied the reasonable consumer would have understood composting is a different process, even if she or he did not have a detailed understanding about what the process involved. In my opinion the representations that were conveyed were that the Products were capable of biodegrading, and – separately – were capable of being turned into compost. That is what would have been understood.

My findings about the nature of the representations made by the labels with the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” on them means that I do not accept the ACCC’s submissions that, in order to avoid misleading or deceiving consumers, the labels needed to have some kind of qualification, direction or instruction on them. As I have found, the reasonable consumer would have understood the statements as indicating the capacity of the Products: they needed no further explanation or qualification.

(Emphasis in original)

53 At [192]–[195], the primary judge discussed the question of whether the representations had a temporal aspect as contended by the ACCC. Her Honour rejected the ACCC’s contention that the representations conveyed by the labelling, taken in context, included the additional (implied) representation to the effect that the products would break down or compost “within a reasonable period of time”. At [193]–[195], her Honour said:

However, I do accept that phrase as used on the labels (like the word “recyclable”) conveyed the representation that the Products were capable of biodegrading if sent to landfill or a “rubbish dump”, and could be composted by one or more of the composting methods that are likely to be broadly familiar to consumers, such as some form of home or community composting, or organic waste collection by local councils. I am satisfied consumers would have understood these processes may take some time, and perhaps some considerable time, but I do not consider there was any temporal aspect incorporated into the representations themselves. In this sense, what consumers might or might not understand about the time biodegradation processes or composting processes might take is beside the point in terms of the Court determining what was conveyed to consumers by the representations: see Aldi Foods at [86] (Perram J, Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreeing).

Although the ACCC contends it is Woolworths’ approach which imbues the ordinary and reasonable consumer with a “high degree of knowledge about the environmental processes of biodegradation and composting”, in fact I consider it is the ACCC’s approach which tends to have this effect. It attributes to consumers who were purchasing these disposable products, which were clearly labelled as not suitable for re-use, a level of reflection, knowledge and consideration that I do not consider is objectively realistic in the context in which these Products were likely to have been purchased. These Products were intended to be disposed of after one use. The use of the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” on the labelling does not convey anything about how long the Products might take to degrade, or to turn into compost. It is unrealistic to assume consumers who were purchasing these Products would have been turning their minds to such matters. The Products were full of environmental messaging - in words, graphics, and colours. They were displayed and offered as an alternative to disposable plastic dishes and cutlery. The message conveyed by the phrase in its context was that the Products were capable of breaking down and being turned into something useful in the soil. Although there were two words in one phrase, as I have already noted, I consider the message conveyed was that there were two ways the Products could be broken down for environmental benefit: that is, by composting, or by biodegrading in landfill.

There is simply no objective basis for the ACCC’s asserted “temporal aspect” to the representations. To the contrary, the absence of any qualifying words or explanations on the packaging reinforces the impression I have found the phrase created in context: that it spoke to the capacities and inherent qualities of the Products, and no more.

(Emphasis in original)

54 The findings which the primary judge made at [167]–[195] make clear that she did not accept the ACCC’s contention that the representations as found were with respect to a future matter or future matters within the meaning of that phrase in s 4 of the ACL: See [196].

55 At [197]–[202], her Honour said:

The representations were not in the nature of a prediction, forecast or projection about a future event. As Woolworths submits, one feature of a future representation is that it is not capable of being true or false (or, I might add, misleading) at the time the representation is made, because the state of affairs to which it relates lies in the future.

The representations might be described as being about the “performance characteristics” of the dishes and cutlery (cf Samsung at [83]), but a more accurate description is that the representations concerned the inherent characteristics of the Products, derived from what they were made from. Their capacity to biodegrade, and their capacity to turn into compost, was a function of their constituent ingredients. That in turn concerned an existing state of affairs, not a future one.

The capacity or capability of the Products to biodegrade and to be used in compost was a feature or characteristic which was able to be proven, or ascertained, in the present. That is what occurred with Mr Brosig’s test: the fact that the Products broke down and composted was a function of what they were made from, combined with the environment into which they were placed, which allowed their capacity or capability to be fulfilled. If the ACCC had conducted its own testing, perhaps (although it seems unlikely) there would have been some conflicting evidence. We will never know.

I see an analogy, as I have noted, with the word “recyclable”. That is also a description of the features or characteristics of a product, derived from what it is composed of. Whether or not it is, in fact, recycled, and turned into something that is re-usable or useful will depend on the environment into which it is placed, and whether that environment allows its features and characteristics to be fulfilled.

I accept Woolworths’ submissions that there are a number of other adjectival descriptions of products which fall into the same category, such as “poisonous”, “flammable”, “non-toxic” or “washable”. All of these are adjectival descriptions because they are describing the characteristics of a product, derived from its ingredients. All deal with a present state of affairs, that is either true or false, and which can be tested or ascertained as a matter of fact. The fact that the testing or proof of the capacity of the product is something that will happen in the future – when the product is used or disposed of – does not alter the nature of the representation. Rather, that is how the present representation about the features of a product is fulfilled (or not fulfilled, as the case may be).

The ACCC seeks to distinguish some of these adjectival descriptions from the phrase in issue by submitting that descriptions such as “flammable” or “washable” concern an “immediately demonstrable fact”. However, that is simply to distinguish between the length of time taken by a process before a product’s features become apparent or are fulfilled. The description “flammable” may refer to an “immediate” outcome, or one that occurs rather more slowly. The same is true of a phrase such as “poisonous”: the effects of the poison may take some time to manifest themselves, or they may not. A description such as “carcinogenic” is another example of an adjectival description of a product where the features or characteristics of the product to which the description relates may take quite some time to manifest themselves. It is nevertheless still a description of present fact, capable of being tested and proven to be true or false.

56 At [207]–[280], the primary judge addressed the question of whether Woolworths had reasonable grounds for making the par 4 pleaded representations upon the following assumptions, namely that:

(a) Her Honour’s primary conclusions that the representations conveyed by the labelling related only to the inherent characteristics of the products were wrong;

(b) The representations conveyed by the labelling included the implied representation that the products would biodegrade or compost within a reasonable time; and

(c) The representations conveyed by the labelling were with respect to future matters.

57 At [209], her Honour held that Woolworths had adduced “evidence to the contrary” for the purposes of s 4(2) of the ACL and that it had adduced sufficient evidence to remove the operation of the deeming provision in s 4(2). These findings meant that the ACCC was obliged to prove that Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making the par 4 pleaded representations and that the ACCC bore the onus of proof in this regard.

58 At [285]–[288] of her Reasons, the primary judge said:

I accept the ACCC’s submission that there is no evidence about the state of mind of those in Woolworths responsible for deciding to make the impugned Products available for sale, with the labelling as it was; and there is no evidence of actual reliance by any relevant decision-maker within Woolworths on the information received by Woolworths Hong Kong from Huhtamaki: see generally [Bathurst Regional Council v Local Government Financial Services Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 1200] at [2827] (Jagot J). As to what is required to establish the state of mind of a corporation in circumstances where a matter such as reliance needs to be established, I accept the ACCC’s submission that the following statement of principle from the High Court in in Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd [1995] HCA 68; 183 CLR 563 at 582–583 is applicable:

As Bright J said in Brambles Holdings Ltd v Carey [(1976) 15 SASR 270 at 279; and see at 275-276, per Bray CJ; at 281-282, per Mitchell J]:

“Always, when beliefs or opinions or states of mind are attributed to a company it is necessary to specify some person or persons so closely and relevantly connected with the company that the state of mind of that person or those persons can be treated as being identified with the company so that their state of mind can be treated as being the state of mind of the company…”

In the absence of any witness, or any direct evidence adduced by Woolworths as to the range of persons who might be said to be identified with the company in this way, I accept the ACCC’s submission that the Environmental Claims Policy indicates approval for sale of a product containing environmental claims must be given by Woolworths’ “Senior Management Group” responsible for the product sale, or the Group’s nominee. There is no evidence this occurred in respect of the Products.

There were, as I have identified above at [229]-[230], some highly relevant statements in the Huhtamaki information, such as the executive summary and general conclusion sections of the OWS test reports in relation to bagasse products. What is missing, however, is evidence about who within Woolworths was aware of this information, understood it related to the impugned Products, and relied on it as part of making the decision that there was a sufficient basis to make the representations as alleged by the ACCC.

Instead what appears to have happened, I infer, is that no one within Woolworths in Australia undertook any consideration of whether there was a reasonable basis for the representations to be made on the packaging of the Products. There is also no evidence about precisely who even decided on the use of the phrase in question. Again, I emphasise these findings are made in the context of the representations being as alleged by the ACCC and as I have set out at [214] above. If, contrary to my own conclusions, that is what was alleged, and it was as to future matters, then I accept the ACCC has proven that Woolworths formed no opinion, let alone an objectively reasonable one, about whether it had a basis to make those claims. There was simply no inquiry made, on the evidence before me. Somewhere, in Woolworths’ documentary records, there may have lain documents that could have been examined, although they would have needed to have been examined for consistency with some of Woolworths’ existing policy positions, and to see whether they objectively established these Products would turn into compost in a reasonable period of time. None of that occurred, on the evidence. It was Ms Ho of Woolworths Hong Kong who sourced the Products and asked for the information from Huhtamaki, but on the evidence engaged in no evaluation of it. She cannot possibly be identified as the responsible person for the decision to make the representations on the packaging of the Products eventually sold in Australian Woolworths stores.

59 At [294]–[299], her Honour set out a summary of her conclusions as to the context of the alleged representations and as to the operation of s 4 of the ACL in the circumstances of the present case in the following terms:

Summary of my conclusions on the alleged representations and on s 4 of the ACL

In summary, I have found the representations made by the words “biodegradable and compostable” affixed to the labels on the Products, read in the context of the packaging as a whole and the circumstances in which the Products were made available for sale both in store and online, were that the Products were capable of breaking down in landfill, and capable of being turned into compost.

I have found the labelling carried no representation as to a time period in which these processes would occur.

I have found the representations were not related to any future matters, but were representations as to present fact, based on the composition of the Products and their capacity to break down and be turned into compost.

If, contrary to these findings, the representations were a) in the form alleged by the ACCC, and b) were as to future matters, then I have found:

(a) Woolworths adduced evidence to the contrary for the purpose of disengaging the deeming effect of s 4(2); but

(b) the ACCC has discharged its burden of proving Woolworths had no reasonable grounds on which to make the representations.

That is because although there was information provided by Huhtamaki to Woolworths Hong Kong that provided some grounds to believe the impugned Products were capable of being turned into compost, and capable of biodegrading, including some information that the composting process could occur within a reasonable period of time, there is no evidence that any person to whom Woolworths’ state of mind can properly be attributed looked at this information and relied upon it, before or at the time the representations were made.

The absence of any direct evidence about the process followed by Woolworths to approve these Products for sale containing the claims as they were made (recalling this on the alternative hypothesis I have set out at [214] above) means it is easier to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that Woolworths in fact formed no opinion about the existence or otherwise of a reasonable basis for the claims it made on the packaging of the impugned Products. There was an obvious failure in the circumstances to follow Woolworths’ own policy concerning the making of environmental claims, and the absence of any evidence from those involved in at least some aspects of the decision-making process supports the findings I have made.

60 At [300]–[415], the primary judge examined and determined the ACCC’s alternative case (that is, the case which it pleaded at pars 11 and 14 of the ACS). At [300]–[307], the primary judge described that case and stated her conclusion that the representations, as found, were true. Her Honour said:

As I noted earlier in these reasons, the ACCC’s alternative s 18 case arose by way of an amendment to its Concise Statement, and is alleged in the alternative to its allegations under s 4.

Since I have determined that the representations were not representations relating to future matters, the ACCC can only succeed if I accept its alternative s 18 case. This is the second of the two-stage process to which I referred to at [84] above. It falls to be determined on the findings I have already made, namely that the representations made by the use of the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” on the packaging of the impugned Products were that the Products were capable of breaking down in landfill and were capable of being turned into compost: see [188] above.

It was common ground that the ACCC bore the onus of proving its allegations in its alternative case. To recap, those allegations, as expressed at [11] of the amended Concise Statement, are:

Further or alternatively to paragraphs 5 to 10 above, the Environmental Claim Representations were false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive because the Select Eco Products were not biodegradable and compostable within a reasonable period of time when disposed of:

i. using domestic composting: or

ii. in circumstances ordinarily used for the disposal of such products, including conventional Australian landfill.

(Emphasis added.)

This formulation in bold followed the formulation of the “Environmental Claim Representations” alleged in [4] of the Amended Concise Statement.

In answer to this allegation, Woolworths denies having made the representations as alleged. I have made findings consistent with Woolworths’ position on the nature of the representations: see [188]-[191]. The representations which I have found were made on the labelling of the impugned Products were, in my opinion, not false, or misleading, or deceptive.

Woolworths then also contends in its Concise Response (at [11]) that in any event, and in answer to the ACCC’s case as alleged, the impugned Products “were, in fact, biodegradable and compostable”. In its closing submissions, Woolworths further contends the evidence established the Products would biodegrade and compost “no slower than many other forms of organic waste”. For the reasons I set out below, I find that to be the case.

The findings to which I have just referred go further than they need to. The ACCC bore the onus of proof on the allegations of contravention of ss 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL in this proceeding. It has proven neither that the representations as alleged were made, nor even if they had been, that they were false or misleading or deceptive, or likely to be misleading or deceptive. That is because the ACCC has failed to prove that the impugned Products would not biodegrade in landfill within a reasonable period of time, and it has failed to prove that the impugned Products were not compostable within a reasonable period of time using domestic composting (landfill being irrelevant because the parties agreed no organic material composts in landfill). To be clear, the ACCC had to prove the negative and has failed to do so.

However, on Woolworths’ evidence, I am also satisfied on the balance of probabilities of the positive proposition: namely that the impugned Products will biodegrade in landfill within a reasonable period of time, and are compostable within a reasonable period of time using domestic composting (landfill being irrelevant because the parties agreed no organic material composts in landfill).

(Emphasis in original)

61 At [329]–[331], the primary judge said:

Conclusion

There was no real disagreement at trial that the impugned Products were capable of biodegrading in landfill, or a “rubbish dump”, and were capable of being turned into useful and usable compost. There is no need to go to any of the contested evidence to reach this conclusion.

On the representations as I have found them to have been made, the ACCC’s s 18 case must fail.

On the representations as alleged by the ACCC, has the ACCC proved its case?

My conclusions that the ACCC has also not discharged its onus of proof on its own formulation of the alleged representations are based largely on the expert evidence adduced by Woolworths, which I found persuasive. I have canvassed some of that evidence already. What remains is to put that evidence in the context of the test conducted by Mr Brosig, which is primarily relevant to the ACCC’s formulation of the alleged representations. As I have noted, this evidence is of sufficient weight to satisfy me of the positive propositions I have set out at [307] above.

62 At [390], her Honour said:

… Mr Brosig’s test had probative value for the time the impugned Products would take to turn into useful and usable compost outside an industrial composting system setting. Although that precise time cannot be derived from his test, given the comparatively quick decomposition into useful compost which occurred during his trial, I am prepared to infer that the impugned Products were, on the balance of probabilities, likely to turn into useful compost within a reasonable period of time – that is, within a matter of months rather than years. Of course, that finding is not necessary because the ACCC bears the onus of proof to establish the falsity of the representations as it alleges those representations were made. I am not only persuaded it has not discharged its burden of proof, I am positively satisfied that the impugned Products were capable of, and do, break down into useful compost, and will do so outside an industrial composting facility in a home composting environment. How long they take to break down will depend on how closely and properly managed the home composting environment is, which I explain below.

63 At [416]–[419], the primary judge dealt with the ACCC’s cases based upon ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL as follows:

Sections 29 and 33

Woolworths is correct to submit, as it did in its reply submissions, that the ACCC made few submissions on the alleged contraventions of ss 29 and 33 of the ACL. The only substantive submissions made appear in [131] of the ACCC’s submissions:

Accordingly, in the absence of Woolworths having established actual (subjective) reliance on (objectively) reasonable grounds, the representations are by the operation of s 4 deemed to be misleading, and contravened the following sections of the ACL:

(a) s 18, as the representations were made in the course of trade or commerce;

(b) s 29(1)(a), as the representations were to the effect that the Select Eco Products were of a particular standard, quality and value;

(c) s 29(1)(g), as the representations were to the effect that the Select Eco Products had particular performance characteristics and benefits; and

(d) s 33 as the representations concerned the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of the goods.

(Footnote omitted.)

These allegations must fail for the same reasons as the s 18 allegations fail: the representations were not as alleged, they did not relate to future matters and even if they were as alleged, they were not false, misleading, or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive. Indeed, on the evidence I have found they were accurate.

There are further problems with these brief submissions, as Woolworths points out. Insofar as s 29(1)(a) is concerned, there was no representation as to the Products being of an indicated or certain standard or quality: see Gardam v George Wills & Co Ltd (No 1) [1988] FCA 289; 82 ALR 415 at 423 (French J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1595 (Perry J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Safety Compliance Pty Ltd (in liq) [2015] FCA 211; ATPR 42-493 (Farrell J). Insofar as s 29(1)(g) is concerned, the ACCC did not specifically allege what “performance characteristics” or “benefits” Woolworths represented the impugned Products had, other than what was conveyed by the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” itself. This allegation must fail for the same reasons the s 18 allegation fails. The same observation can be made about the terms of s 33.

The positive findings I have made about the characteristics of the impugned Products would also mean the alleged contraventions of these provisions must fail. This is the likely reason little time was expended by the ACCC on submissions about these provisions: they stand or fall with the s 18 allegations, at least at a basic level. More may indeed be required, but what this might involve was not developed by the ACCC, which had the onus of proof.

The Appeal

64 In its Amended Notice of Appeal, the ACCC relies upon four grounds of appeal.

65 By ground 1, the ACCC contends that the primary judge erred in failing to find that the representations made by Woolworths as found by her Honour at [188], [190] and [294] of her Reasons were, in whole or in part, with respect to a future matter because they constituted a prediction, promise, forecast or opinion as to a future matter that the products would biodegrade or turn into compost when that outcome was dependent on the time, method and/or conditions of disposal and treatment. This ground assumes that the only representations that Woolworths made were constituted by the express statements in writing on the labelling of the products that those products were “biodegradable” and “compostable”. Nonetheless, by this ground, the ACCC seeks to contend that the representations which her Honour found were made, in whole or in part, with respect to a future matter or future matters. We are not convinced that such a case was articulated by the ACCC in the ACS or litigated at trial. However, Woolworths did not submit that we should not entertain grounds 1 and 2 because they raise matters not argued below. In those circumstances, we will permit grounds 1 and 2 to be maintained.

66 By ground 2, the ACCC argues that the primary judge ought to have found that:

(a) Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making the representations as found; and

(b) The representations, as found, were misleading by reason of the application of s 4(1) of the ACL with the consequence that Woolworths contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

67 Ground 2 is dependent upon the ACCC succeeding on ground 1.

68 By ground 3, the ACCC contends, in the alternative to grounds 1 and 2, that the primary judge erred in failing to find that:

(a) Woolworths made the par 4 pleaded representations; and

(b) The par 4 pleaded representations were in whole or in part with respect to a future matter or future matters.

We note that the term “the alleged representations” adopted by the ACCC in grounds 3 and 4 is a shorthand description for the par 4 pleaded representations.

69 By ground 4, the ACCC argues that the primary judge ought to have found that the par 4 pleaded representations were misleading by reason of the operation of s 4(1) of the ACL and that, by making those representations in circumstances where it did not have reasonable grounds for making them, Woolworths contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

70 The ACCC has not appealed the primary judge’s decision to reject the whole of its alternative case. This was confirmed by Senior Counsel for the ACCC at the hearing of the appeal: See Transcript p 3 ll 34–35 and Transcript p 21 ll 9–14.

71 Woolworths relied upon a Notice of Contention filed on 23 August 2019 which specified the following matters in support of the proposition that the judgment of the primary judge should be affirmed on grounds other than those relied upon by the primary judge:

Grounds relied on

1. If, as alleged in ground 3 of the Appellant’s Notice of Appeal (and contrary to the conclusion of the learned trial judge) the Appellant’s pleaded representations were in fact made, then those representations were not representations with respect to any future matter. Rather, they were representations as to the presently existing character or qualities of the products (i.e. that they were biodegradable and compostable within a reasonable period of time). As the learned trial judge found at [307], any such representations (if made) were true and correct. They were therefore not misleading or deceptive.

2. To the extent that the learned trial judge concluded that the Appellant’s pleaded representations, if made, would be representations with respect to a future matter, then her Honour erred for the reasons set out in paragraph 1 above. However, the Respondent disputes that the learned trial judge made any such finding. Although the Appellant suggests in ground 3 of its Notice of Appeal that her Honour did make such a finding by reference to the judgment at [57], that paragraph must be read with:

a. the observations of the learned trial judge at [58] and [201]–[206];

b. the chapeau to [297];

c. the treatment by the learned trial judge at [307] of these matters as presently existing factual matters which were true (with her Honour earlier concluding at [197] that one feature of a future representation is that it is not capable of being true or false at the time it is made); and

d. the observations of the learned trial judge at [421] and [422].

72 At Transcript p 24 ll 13–19, Senior Counsel for the ACCC stated for the record a concession which he understood had just been conveyed to him by Senior Counsel for Woolworths concerning the question of whether Woolworths had reasonable grounds for making the representations as found and for making the par 4 pleaded representations (the making of which was, of course, denied by Woolworths) upon the assumption that this Court should find that one or other of those sets of representations was made with respect to a future matter or future matters. At that point in the appeal hearing, Senior Counsel for the ACCC said:

Okay. Well, I’m assisted by my friend who has just mentioned that they’re not going to take issue with the submission that, if we’ve established a future matter, that [sic] the finding as to the absence for reasonable grounds should apply in respect of both the representations pleaded, as well as the representations found. That’s what I understand their concession to be. I’ve got that correct. Thank you. There’s an extensive discussion about what Woolworths should have done and didn’t do, but I don’t need to trouble the court with it in light of that concession. …

73 That concession meant that, if this Court were to accept the ACCC’s contention that whatever representations were made by Woolworths (either the representations, as found, or the par 4 pleaded representations) were made with respect to a future matter or future matters, then Woolworths accepted that the ACCC had discharged its onus of proof in respect of its contention that Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making the relevant representations.