FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd

[2020] FCAFC 130

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The appellant (ACCC) appeals from orders of the Federal Court made on 11 October 2019, dismissing a proceeding that had been brought by the ACCC against the respondent (TPG).

2 TPG is a retailer of mobile, internet and home telephone services. It supplies services to consumers on a prepaid basis, meaning that customers are required to pay TPG in advance for the TPG services selected by them. Since 14 March 2013, TPG has marketed on its website and in brochures a variety of personal mobile, internet and home telephone plans. Each such plan required a fixed monthly amount to be paid by the customer in advance for the particular service (mobile, internet and home telephone) that was included in the plan acquired by the customer.

3 The proceeding brought by the ACCC concerned the terms of TPG’s mobile, internet and home telephone plans that related to a “prepayment” of $20. In order to enter into a plan, customers were required to make a “prepayment” of $20 (or more if nominated by the customer) for service usage that was not within the included value of the plan acquired. The prepayment was debited from the customer’s nominated bank account or credit card. Usage charges incurred by the customer for services not within the included value of the plan were deducted by TPG from the prepayment amount or balance. The terms of TPG’s plans stipulated that:

(a) when the balance of the prepayment fell to below $10, TPG will debit a sufficient amount from the customer’s bank account or credit card (if available) to restore the prepayment amount (Automatic Top-Up Term); and

(b) when the customer cancelled their plan, the unused balance of the prepayment was forfeited to TPG (Forfeiture Term).

4 It was common ground at trial that the combined effect of those terms was that, in the ordinary case, when the customer cancelled their plan there would be a minimum prepayment balance of $10 that would be forfeited to TPG. The minimum prepayment balance would exist because, if the customer used services before the plan cancellation took effect that caused the balance of the prepayment to fall below $10, TPG would automatically “top-up” the prepayment in accordance with the Automatic Top-Up Term. Thus, when the plan cancellation took effect, the amount of the prepayment balance would ordinarily lie between the minimum balance of $10 and the default amount of $20 (or a higher amount if nominated by the customer). The precise balance at cancellation would depend on the customer’s service usage that was not within the included value of the plan in the lead up to the date of cancellation.

5 The evidence showed that in certain limited circumstances (which accounted for a very small percentage of cases) a TPG customer was able to use all of the prepayment for the service while their plan remained on foot, including where the automatic top-up payment was not received by TPG (either by virtue of some error, or because the customer took steps to withdraw their authority for that payment) or where the customer used all of the value of the prepayment prior to cancellation but before the automatic top-up occurred. Ultimately, TPG did not seek to rely on those circumstances at trial (which were described as accidental) and no reliance was placed on them on the appeal.

6 The ACCC’s case at trial involved two causes of action. The first was that TPG’s description of the prepayment on its website and in brochures involved misleading conduct contrary to ss 18 and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) or false or misleading representations contrary to ss 29(1)(b), (g) and (i) of the ACL. The second was that the prepayment terms were void under s 23 of the ACL as unfair terms. The primary judge dismissed both causes of action. On this appeal, the ACCC relied only on the first cause of action, and only on ss 18 and 29(1)(b), (g) and (i) of the ACL. In short, it contends that the primary judge erred in failing to find that TPG’s description of the prepayment on its website and in brochures involved misleading conduct or false or misleading representations.

7 In respect of its case based on ss 18 and 29(1)(b), (g) and (i) of the ACL, the ACCC alleges that TPG’s advertising material for its mobile, internet and home telephone plans communicated two representations (which we will refer to collectively as the Prepayment Representations):

(a) that the “prepayment” was an advance payment for services that the customer could use, and the full amount of the prepayment could be used for telecommunications services before the customer cancelled their plan (Prepayment Use Representations); and

(b) that the purpose of holding the “prepayment” funds was to apply them to the payment of telecommunications services and that, if the prepayment was not required for that purpose, it would be returned to the customer (Prepayment Refund Representations).

8 The ACCC alleged that each of the Prepayment Representations was false or misleading because, on the cancellation of the plans, the balance of the prepayment, which would ordinarily be a minimum of $10, would be forfeited to TPG.

9 For the reasons that follow, we consider that the primary judge’s conclusion that the Prepayment Representations were not made by TPG was correct and we therefore dismiss the appeal with costs.

Relevant facts

10 The only facts relevant to the appeal were the content of statements made on TPG’s website and in its brochures concerning the prepayment for its mobile, internet and home telephone plans and the context in which those statements were made. There was no dispute in relation to those facts which we summarise in the paragraphs that follow, drawing upon the findings of the primary judge as well as the screen shots of TPG’s website and copies of pages of its brochures which were annexures to the statement of agreed facts tendered in evidence. We note that certain of the screen shots and pages of the evidence to which we were taken on the appeal were not included in the annexure to the primary judge’s reasons. However, there was no dispute between the parties that the screen shots and pages to which we were taken, and on which the ACCC placed emphasis, were in evidence at trial.

11 The ACCC addressed the webpages and brochure pages on which it relied largely in the order in which they would likely be viewed by a consumer considering the purchase of a TPG plan. We have adopted the same approach in the summary of the relevant facts that follows. We have also only reproduced the evidence relating to TPG’s mobile phone plans. Similar material existed for TPG’s internet and home telephone plans and neither party suggested that there was any relevant difference in the language used in respect of those plans.

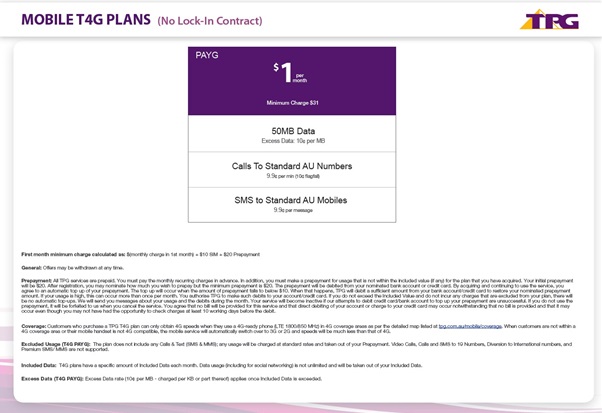

12 Annexure A to the statement of agreed facts contained screen shots of TPG webpages offering mobile phone plans and was the start of the “purchasing pathway” when a customer sought to acquire a TPG mobile plan through TPG’s website. The first such webpage is reproduced as Annexure 1 to this judgment. The ACCC relied on the following statements made on that webpage:

(a) The headline offer on the page is a mobile plan for $45 per month. Immediately underneath that figure is a statement that $85 is the minimum charge in the first month. Immediately underneath that statement is the following explanation, in slightly smaller type, of why the minimum charge in the first month is $40 more than the monthly price:

Minimum charge includes $20 for the SIM plus $20 Prepayment Outside Included Value”.

The ACCC contends that the latter statement, $20 Prepayment Outside Included Value, conveyed both of the Prepayment Representations.

(b) Immediately below the headline offer are a number of tabs, one of which is headed “Terms & Conditions” which takes the consumer to a copy of TPG’s standard terms and conditions. We will return to that document below, although ultimately it has no bearing on the issues in the proceeding.

(c) Next, the webpage contains reference to plans with alternative prices from $19.99 per month up to $45 per month. In respect of each price, the webpage states the minimum charge in the first month (which is $40 above the plan price) and has a hyperlink called “Critical information summary”. We will return to the content of that link below.

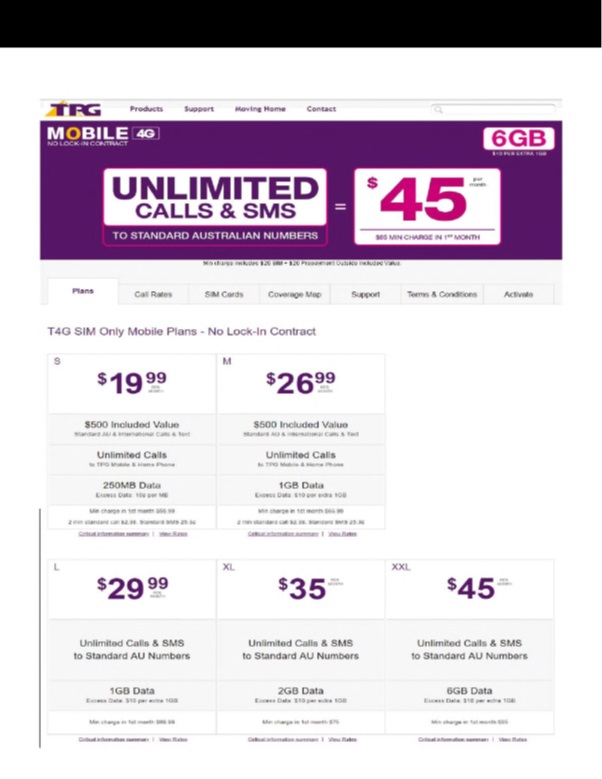

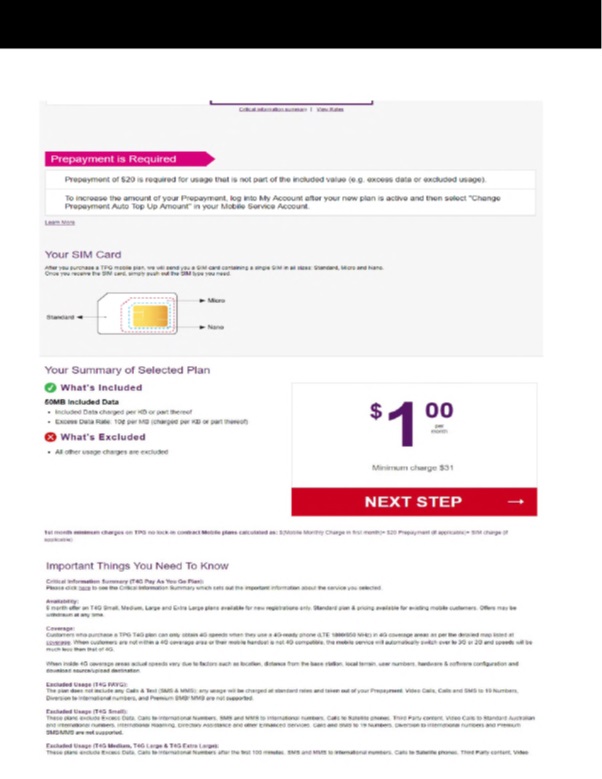

13 The second such webpage (which also formed part of Annexure A to the statement of agreed facts) is reproduced as Annexure 2 to this judgment. We infer that this webpage appears when a person clicks on the $35 plan on the preceding page (Annexure 1). The ACCC relied on the following statements made on that webpage:

(a) The headline offer on the page is a mobile plan for $35 per month. Immediately underneath that figure is a statement that the minimum charge in the first month is $75. Immediately beneath that is a “BUY NOW” button.

(b) On the line below the headline offer, in relatively small type, there is an explanation of the minimum charge in the first month. It is worded as follows:

1st month minimum charges on TPG no lock-in contract Mobile plans calculated as: $(Mobile monthly charge in first month) + $20 SIM charge + $20 Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value

Again, we note that the ACCC contends that the words “$20 Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value” conveys both of the Prepayment Representations.

(c) The underlined words are a hyperlink to a section of the same webpage headed “Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value” (which follows the heading in larger capitalised type “IMPORTANT THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW”) and which contains the following paragraph (which we will refer to as the Prepayment Terms):

All TPG services are prepaid. You must pay the monthly recurring charges in advance. In addition, you must make a prepayment for usage that is not within the included value (if any) for the plan that you have acquired. Your initial prepayment will be $20. After registration, you may nominate how much you wish to prepay but the minimum amount is $20. The prepayment will be debited from your nominated bank account or credit card. By acquiring and continuing to use the service, you agree to an automatic top up of your prepayment. The top up will occur when the amount of prepayment falls to below $10. When that happens, TPG will debit a sufficient amount from your bank account/credit card to restore your nominated prepayment amount. If your usage is high, this can occur more than once per month. You authorise TPG to make such debits to your account/credit card. If you do not exceed the Included Value and do not incur any charges that are excluded from your plan, there will be no automatic top-ups. We will send you messages about your usage and the debits during the month. Your service will become inactive if our attempts to debit credit card/bank account to top up your prepayment are unsuccessful. If you do not use the prepayment, it will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service. You agree that no bill will be provided for the service and that direct debiting of your account or charge to your credit card may occur notwithstanding that no bill is provided and that it may occur even though you may not have had the opportunity to check charges at least 10 working days before the debit.

As can be seen, the Prepayment Terms include the Automatic Top-Up Term and the Forfeiture Term. The Prepayment Terms appear in a number of pages of TPG’s website and brochures. In respect of the Prepayment Terms, the ACCC relied on the heading “Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value” and the statement “If you do not use the prepayment, it will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service”. The ACCC contends that both the heading and the latter statement convey the Prepayment Use Representations; i.e. that it was possible for a customer to use the prepayment prior to cancellation of the service.

(d) Immediately following the heading “IMPORTANT THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW” are hyperlinks to the Critical Information Summary for each of the advertised mobile plans.

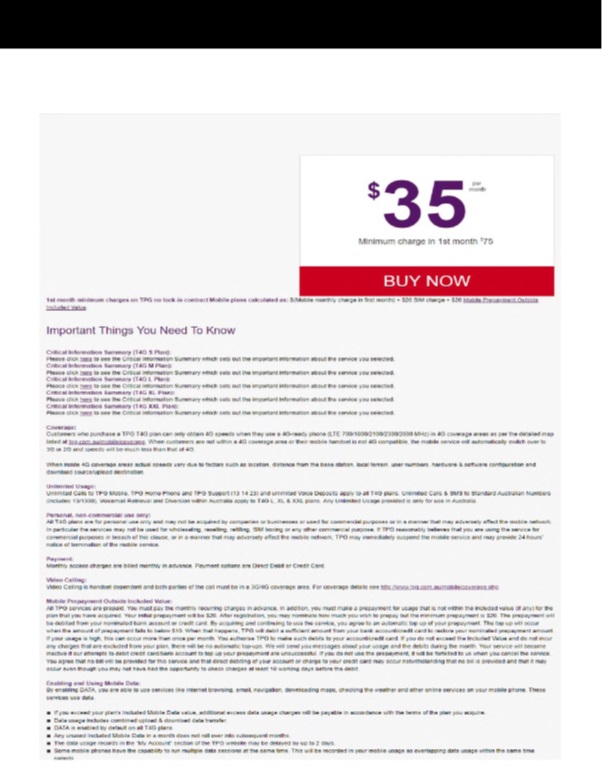

14 The purchasing pathway for a TPG mobile plan continued through screen shots of TPG’s website which were shown as Annexure I to the statement of agreed facts. It is not necessary to reproduce the whole of Annexure I. However, reproduced as Annexure 3 to this judgment is a screen shot of the webpage that appears as the second step in the purchasing pathway when selecting a mobile plan. The ACCC relied on the following statements from that webpage:

(a) Under the prominent heading “Prepayment is Required”, the following statement appears:

Prepayment of $20 is required for usage that is not part of the included value (e.g. excess data or excluded usage).

The ACCC emphasised the fact that prepayment is described as being “for usage”, and argued that this conveys both Prepayment Representations.

(b) Under the button “NEXT STEP” in respect of the selected plan (in the example, a $1 per month plan), and by way of explanation of the stated minimum charge of $31, the following statement appears:

1st month minimum charges on TPG no lock-in contract Mobile plans calculated as: $(Mobile monthly charge in first month) + $20 Mobile Prepayment (if applicable) + SIM charge (if applicable).

(c) Under the prominent heading “Important Things You Need To Know”, the following information appears:

Excess Data (T4G Small, T4G Medium, T4G Large & T4G Extra Large)

These plans have a certain amount of Included Data each monthly billing cycle. If at any time in a billing cycle you use more than the amount of Included Data, we will charge $10 out of your Prepaid Balance to increase the amount of Included Data available in that particular billing cycle by 1GB. If there is insufficient funds in your Prepaid Balance, your Mobile Data will become inactive until your Prepaid Balance is topped up to a sufficient level.

Charges for Excess Data (T4G Small, T4G Medium, T4G Large T4G Extra Large):

Example of charges:

1MB excess data: We will charge $10 out of your Prepaid Balance which will give you an extra GB to use for the billing period.

Over 1GB excess data: We will charge another $10 out of your Prepaid Balance which will give you another extra GB to use for the billing period.

The ACCC relied particularly on the use of the phrase “prepaid balance” as conveying the notion that a customer has a running account that can be used for services, thereby reinforcing the Prepayment Representations.

(d) Also under the heading “Important Things You Need To Know”, the Prepayment Terms are reproduced under the heading “Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value (T4G PAYG)” (this version of the Prepayment Terms differs immaterially from the version reproduced above).

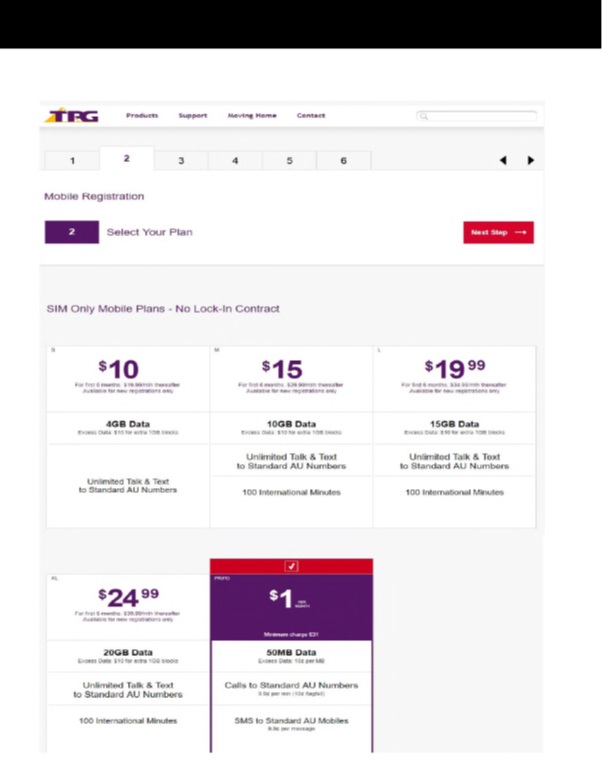

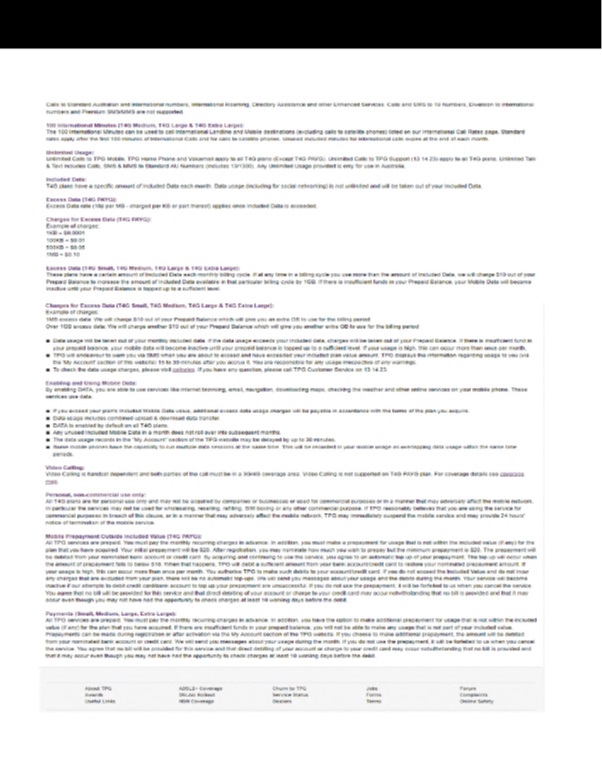

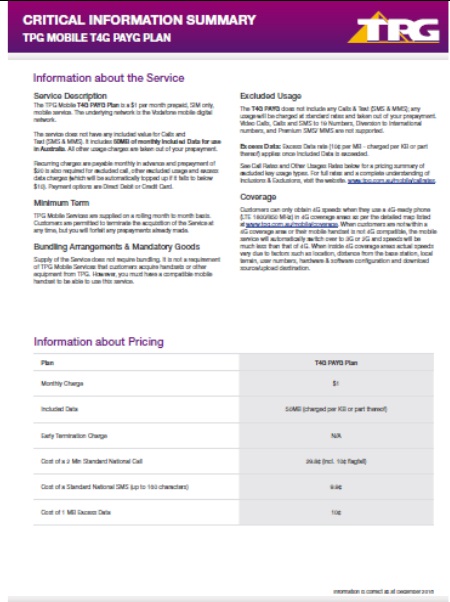

15 Annexure O to the statement of agreed facts is an example of a webpage containing the Critical Information Summary for one of TPG’s mobile plans, which is required by the Telecommunications Consumer Protection Code. That webpage is reproduced as Annexure 4 to this judgment. The ACCC relied on the following statements made on that page:

(a) Under the heading “Service Description”, the following passage appeared:

The TPG Mobile T4G PAYG Plan is a $1 per month prepaid, SIM only, mobile service. The underlying network is the Vodafone mobile digital network.

The service does not have any included value for Calls and Text (SMS & MMS). It includes 50MB of monthly Included Data for use in Australia. All other usage charges are taken out of your prepayment.

Recurring charges are payable monthly in advance and prepayment of $20 is also required for excluded call, other excluded usage and excess data charges (which will be automatically topped up if it falls to below $10). Payment options are Direct Debit or Credit Card.

The ACCC relied particularly on the statement that “other usage charges are taken out of your prepayment” as conveying the notion that the prepayment can be used for the purchase of services, thereby reinforcing the Prepayment Representations.

(b) Under the immediately following heading “Minimum Term”, the following sentences appeared:

TPG Mobile Services are supplied on a rolling month to month basis. Customers are permitted to terminate the acquisition of the Service at any time, but you will forfeit any prepayments already made.

While this is a further statement of the Forfeiture Term, the ACCC argued that it fails to state clearly that ordinarily the customer will forfeit a minimum of $10 on cancellation of their service.

16 Annexure S to the statement of agreed facts contains extracts from TPG’s brochure concerning its mobile plans. The extracts relied on by the ACCC are reproduced at Annexure 5 to this judgment. The ACCC relied on the following statements appearing in those extracts:

(a) Immediately below the box depicting the $1 per month plan is the statement:

First month minimum charge calculated as: $(monthly charge in 1st month) + $10 SIM + $20 Prepayment.

(b) Below that, opposite the heading “Prepayment”, are the Prepayment Terms.

17 Annexure X to the statement of agreed facts contains a copy of TPG’s standard terms and conditions. It is unnecessary to reproduce the whole of the standard terms and conditions, and neither party placed any significant reliance on the document. However, the ACCC drew attention to section 7 of the terms, headed “usage”, and the first sentence of clause 7.1 which stated: “You acknowledge that charges will be incurred when the service is used”. The ACCC argued that that term conveyed that charges would only be imposed on customers for services that are used.

The statutory provisions

18 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides as follows:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

19 Section 29(1)(b), (g) and (i) of the ACL provide (relevantly) as follows:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of … services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply of ... services:

…

(b) make a false or misleading representation that … services are of a particular ... value … ; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that … services have … uses or benefits; or

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of … services.

20 It can be seen that s 18 prohibits conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, whereas s 29 prohibits the making of a false or misleading representation. Conduct that contravenes s 18 may involve, but need not involve, the making of a false or misleading representation: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 (Campbell) at [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ, referring with approval to Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592 (Butcher) at [103] per McHugh J. In the present case, though, the ACCC’s allegations do concern the making of an allegedly false or misleading representation in the form of the Prepayment Representations. It is necessary to consider the ACCC’s allegations in the way in which they were expressed in the pleadings (through the form of a concise statement) and presented at trial.

21 Although s 18 takes a different form to s 29, the prohibitions are similar in nature. Whilst s 29 uses the phrase “false or misleading” rather than “misleading or deceptive”, it has been said that there is no material difference in the two expressions: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] per Gordon J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 at [40] per Allsop CJ; Comite Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell [2015] FCA 1110; 330 ALR 67 at [170] per Beach J.

22 The applicable principles concerning the statutory prohibition of misleading or deceptive conduct (and closely related prohibitions) in the ACL are well known and there was no dispute between the parties concerning those principles. The central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 200 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45 (Campomar) at [98]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG Internet) at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; Campbell at [25] per French CJ. A number of subsidiary principles, directed to the central question, have been developed:

(a) First, conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility of it doing so: see Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (Global Sportsman) at 87, referred to with apparent approval in Butcher at [112] by Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ; Noone (Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria) v Operation Smile (Australia) Inc (2012) 38 VR 569 at [60] per Nettle JA (Warren CJ and Cavanough AJA agreeing at [33]).

(b) Second, it is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 per Stephen J (with whom Barwick CJ and Jacobs J agreed) and at 234 per Murphy J; Puxu at 197 per Gibbs CJ; Google Inc v ACCC (2013) 249 CLR 435 (Google) at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(c) Third, it is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Google at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ. Evidence that a person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive within the meaning of the statute. The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself: see Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ.

(d) Fourth, it is not sufficient if the conduct merely causes confusion: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ and 209-210 per Mason J; Campomar at [106]; Google at [8] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(e) Fifth, where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]-[105]; Google at [7] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

23 The primary judge referred to a further or alternative test for whether conduct that is directed to the public generally or a section of the public is misleading: whether a significant number of persons to whom the conduct is directed would be led into error (PJ at [41] and [42]). On the appeal, TPG relied on the test, submitting that it is necessary for the ACCC to show that a “not insignificant number” of reasonable persons within the relevant class of persons (prospective purchasers of TPG’s services) have been misled or deceived or are likely to be misled or deceived. No substantive argument was directed to the correctness of that test by the ACCC and our decision in this appeal does not turn upon it. Nevertheless, we consider it appropriate to record our view that the test is, at best, superfluous to the principles stated by the High Court in Puxu, Campomar and Google Inc and, at worst, an erroneous gloss on the statutory provision. We make the following brief observations:

(a) The origin of the “significant number” test can be traced back to decisions of Franki J in Weitmann v Katies Ltd (1977) 29 FLR 336 (at 343) and Wilcox J (as a member of a Full Court) in 10th Cantanae Pty Ltd v Shoshana Pty Ltd (1987) 79 ALR 299 (at 302). In both cases, the test appears to have been formulated by adoption of principles applied in the law of passing off. However, it has long been settled that the proper construction of s 18 is not controlled by analogous common law or statutory remedies: see, for example, World Series Cricket v Parish (1977) 16 ALR 181 at pp 198-199 per Brennan J (as a judge of the Federal Court), referred to with approval in Puxu at p 198 per Gibbs CJ and at 204-205 per Mason J, and Campomar at [97].

(b) The test has never been embraced by the High Court. As early as 1981 in Puxu, the High Court formulated the relevant question as the effect of the impugned conduct on reasonable or ordinary members of the class of persons to whom the conduct was directed: see at 199 per Gibbs CJ and 210 per Mason J. In the High Court cases that have followed Puxu, particularly Campomar and Google, the test has always been stated in substantially the same terms.

(c) The correctness of the “significant number” test was doubted by Finkelstein J at first instance in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Exchange Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 955; 202 ALR 24 at [11] and, a short time later in .au Domain Administration v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424; 207 ALR 521 at [22]-[26], Finkelstein J concluded that the test had been overtaken by the test stated by the High Court in Campomar. In the appeal from the National Exchange decision, the Full Court expressed the view that the “significant number” test was merely an alternative way of expressing the test stated by the High Court in Campomar: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investment Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 49 ACSR 369 (National Exchange) at [23] per Dowsett J and at [70] per Jacobson and Bennett JJ.

(d) Despite the view expressed by the Full Court in National Exchange, the “significant number” test has been referred to and applied in a number of cases in the Federal Court, often in the context of “passing off” type cases. In particular, the test was applied by Tamberlin and Siopis JJ in Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd (2008) 171 FCR 579 at [45]-[48], by Greenwood J in Bodum v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 98; 280 ALR 639 at [209] (with whom Tracey J agreed), and by Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ in Global One Mobile Entertainment Pty Ltd v ACCC [2012] FCAFC 134 at [108], [111]. But these cases did not resolve the question whether it was a different and additional test to the principles stated by the High Court.

(e) More recently, in Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; 118 IPR 239, Beach J made passing reference to the test, stating that he was inclined to the view that if, applying the Campomar test, reasonable members of the class would be likely to be misled, then such a finding carries with it that a significant proportion of the class would be likely to be misled (at [270]). But later, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 2) [2017] FCA 709 at [42] and in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2)(2018) 266 FCR 147 at [2279], his Honour said he had become inclined to the view that a finding that reasonable members of the class would be likely to be misled does not necessarily carry with it that a significant proportion of the class would be likely to be misled, so that a finding of a "not insignificant number" of members of the class being likely to be misled is an additional requirement that needs to be satisfied.

(f) Respectfully, we disagree. Whether or not speaking of a reasonable member of a class implies as a matter of strict logical necessity that one is speaking of a significant proportion of that class (cf. Dowsett J in National Exchange at [23]), nothing in the language of the statute requires the court to determine the size of any such proportion. We would emphasise the point that Dowsett J made in National Exchange at [24] that the test of reasonableness involves the recognition of the boundaries within which reasonable responses will fall. In our view it does not require any attempt to quantify, even approximately, the hypothetical reasonable individuals who have a particular response. The idea that such quantification is possible will almost always be an illusion, and illustrates how the test of "a not insignificant number" distracts from the terms of the statutory prohibition and the guidelines to its application laid down in Campomar.

(g) While, in our view, s 18 of the ACL (and analogous provisions) do not require the satisfaction of the “significant number” test in order to establish contravention, a party may choose to put its particular case that way. That is, it is open for a party to seek to establish that conduct is misleading by establishing that persons were in fact misled, and in such cases it may be necessary to establish that the number of such persons was significant in order to persuade the court that the conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive: see National Exchange at [23]. But that will be a function of how the case is put; it is not a requirement inherent in the statute.

24 Consistently with our view that the “significant number” test is at best superfluous and at worst an erroneous and distracting gloss, we consider it appropriate to approach the ACCC’s arguments on the basis of the principles stated by the High Court in Puxu, Campomar and Google Inc and to ignore the “significant number” test. Nevertheless, we note that our conclusion would not change even if we were to apply the “significant number” test.

25 A question that commonly arises is whether a publication or communication is misleading when it contains a misleading statement in one place but also contains another statement, perhaps in a different place in the publication or communication, which remedies the misleading character of the first statement. Ultimately, the question is one of overall assessment of the publication or communication. The correct approach was summarised by Edelman J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corp (No 3) [2016] FCA 196; 337 ALR 647 (at [214]) (upheld in Valve Corp v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2017) 258 FCR 190, noting that there was no challenge to his Honour’s relevant statements of principle (recorded at [158]):

One consequence of the need to consider the conduct in light of all relevant circumstances is that any allegedly misleading representation must be read together with any qualifications and corrections to that statement. Hence, although a qualification to a statement might be effective to neutralise an otherwise misleading representation, this might not always be so, particularly if the misleading representation is prominent but the qualification (often linked to the representation by an asterisk) is not: Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Limited v Cassidy [2003] FCAFC 289; (2003) 135 FCR 1, 17 [37] (Stone J). As Keane JA expressed the point, the qualifications must have “the effect of erasing whatever is misleading in the conduct”: Downey v Carlson Hotels Asia Pacific Pty Ltd [2005] QCA 199 [83].

The reasoning of the primary judge

26 The primary judge concluded (at PJ [65]) that there were two fundamental difficulties with the ACCC’s case. The first was that it assumed that a reasonable and ordinary consumer would not read the entirety of the Prepayment Terms on TPG’s website or in its brochures. The second was that it relied on a “myopic” approach to the meaning of the word “prepayment”.

27 As to the meaning of the word “prepayment”, the primary judge concluded that it is artificial to give the word as much work to do as the ACCC’s case requires, and the meaning for which the ACCC contends is not reasonably open (at PJ [67]). His Honour accepted the submission of TPG that the word “prepayment” does not convey that the payment will be refunded if it is not used (at PJ [72]). His Honour found that, when the Prepayment Terms are read, they disclose that if the prepayment is not used on cancellation of the service, it will be forfeited to TPG (at PJ [69]-[70]).

28 His Honour therefore concluded that the statements in the TPG webpages and brochures on which the ACCC relied did not convey the Prepayment Representations (at PJ [74]).

The ACCC’s arguments

29 The ACCC submitted that the word “prepayment” ordinarily conveys payment in advance for goods or services to be provided, observing that the Macquarie Dictionary (5th Edn, 2009) defines “prepay” as “1. To pay beforehand; 2. To pay the charge upon in advance” and the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th Edn, 2007) defines the word as “1. Pay postage on (a letter, parcel, etc.) before posting; 2. Pay (a charge) in advance”. In this case, the service to be provided for the prepayment was access to “excluded usage” (i.e. telecommunications services beyond what was included as part of the bundle covered by the monthly payment). The ACCC argued that that meaning of the word in the context of the TPG website and brochures was reinforced by the repeated statements that TPG services are “prepaid”. The effect of such statements was to emphasise that the consumer must pay in advance for the services.

30 The ACCC submitted that the word “prepayment”, in the context of TPG’s plans, also implicitly conveyed the notion that if the prepayment was not required for the purpose of “excluded usage”, it would be returned to the customer. The ACCC argued that, in the same way as a customer who made a payment for a service that was not provided could expect a refund, so too a person who makes a prepayment for a service that is not provided would also expect a refund (especially, in circumstances where such services could not be accessed).

31 The ACCC submitted that while the TPG prepayment would be used for the provision of “excluded usage” services during the term of the relevant plans, upon the cancellation of the plans at least part of the prepayment (a minimum of $10) would be incapable of being so used because it would be forfeited to TPG. This fact rendered the use of the word “prepayment” misleading.

32 The ACCC further submitted that the misleading use of the word “prepayment” by TPG was not corrected by the Prepayment Terms that were also published on the TPG website and in its brochures. First, there was no reason to think that a consumer would find, read and absorb the Prepayment Terms, particularly in the face of the clear representations in the headline sections (referring to the prepayment of $20). In that respect, the ACCC argued that the Forfeiture Term, within the Prepayment Terms, was the second last sentence towards the end of a “long, wordy, complex and dull clause”. Second, even if they did read the Prepayment Terms, and particularly the Forfeiture Term, the terms were insufficient to overcome or qualify the misleading impression created by the headline sections. In that respect, the ACCC argued that the Forfeiture Term commences with the clause “If you do not use the prepayment”, suggesting that a customer would be able to use the prepayment prior to the final cancellation of the service.

TPG’s arguments

33 TPG’s primary submission is there was nothing about the use of the word “prepayment” in the context in which it was used which conveyed that the full amount of the prepayment, or the balance remaining prior to cancellation by the customer, could be used, or that any unused balance of the prepayment would be refunded if unused at cancellation.

34 TPG submitted that the word “prepayment”, comprising the prefix “pre” and the word “payment”, merely conveyed that the relevant payment is made in advance of a relevant supply. The word was aptly used by TPG because it allowed customers to access value for services outside the included value of their plan. Customers were able to expend the initial prepayment for such services, and every topped-up prepayment in the same manner, until they cancelled their plan. The forfeiture of the balance of the initial or topped-up prepayment at the time of the customer’s cancellation (depending on whether and the extent to which the customer had utilised the prepayment) has no bearing upon the payment’s character as a prepayment, but merely means that the payment was a prepayment on terms. TPG argued that there is nothing about the use of the word “prepayment” in the context in which it was used which conveyed, in and of itself, what the terms of the prepayment were, and did not convey that the terms were that the full amount of the prepayment could be used or that the balance remaining prior to cancellation by the customer would be repaid.

35 TPG further submitted that, if, contrary to its submissions, the word “prepayment” conveyed the impression that the prepayment was able to be used in its entirety, any such impression was dispelled by the clear disclosure of the Forfeiture Term within the Prepayment Terms. It argued that the Forfeiture Term was prominently displayed and that consumers reading the Forfeiture Term would understand that they would lose any unused portion of the prepayment made (either as part of the initial $20 prepayment or as part of a “topped-up” payment) at the point of cancellation.

Consideration

36 We agree with the conclusion of the primary judge that the statements in the TPG webpages and brochures on which the ACCC relied did not convey the Prepayment Representations, largely for the reasons stated by the primary judge.

37 As accepted by Senior Counsel for the ACCC, the ACCC’s case is focussed on the forfeiture of the balance of the prepayment upon cancellation of the plan by a customer. In the ordinary case, the balance will be a minimum of $10 with the result that almost all customers (who cancel their plans) will forfeit an amount of prepayment. Prior to cancellation, the prepayment is applied by TPG in payment of “excluded usage”, being services outside (or above) the included value of the plan. No complaint is made about that application of the prepayment, or the arrangements for “topping-up” the prepayment during the course of the plan. In practical terms, the ACCC’s case is that, by using the word “prepayment”, TPG represented to consumers that they would be able to use up the prepayment prior to the end of their contract and they would not forfeit any part of the prepayment at the end of their contract.

38 The ACCC’s case fails primarily because TPG’s use of the word “prepayment” in the statements relied on by the ACCC does not convey the terms on which the prepayment would be held and applied by TPG, particularly at the end of the contract. The words and phrases relied on by the ACCC do not carry that burden. The use of the word “prepayment” in the statements relied on by the ACCC merely conveyed that a payment in the specified amount was required when signing up to the plan and that it was a payment which would be applied toward services outside (or above) the included value of the plan. In itself, the word prepayment is silent on how any balance of the prepayment would be treated at the end of the contract. If a consumer wished to know what would occur at the end of the contract, they had to read further. If they did, they would be informed that the balance would be forfeited to TPG.

39 We agree with the submission of Senior Counsel for TPG that an analogy can be drawn with another commonly used word “deposit”. In and of itself, the word “deposit” does not convey whether the deposit will be returned to the payer and in what circumstances it will be returned. The terms on which a deposit is to be held, and whether it will be returned on certain events, is a matter that requires explanation in further terms and conditions and is not implicit in the use of the word itself.

40 This is not a case in which a publication or communication conveyed a dominant message (for example, in large print at the commencement of the publication or communication) which was later qualified by statements in fine print. Indeed, many of the words and phrases on TPG’s webpages and in its brochures on which the ACCC relied were themselves in relatively fine print. In no sense could the words and phrases be characterised as dominant. But more importantly, they did not convey the message alleged by the ACCC. We note the following matters about the webpages and brochures relied on by the ACCC:

(a) In the webpage reproduced as Annexure 1 (the start of the purchasing journey), the phrase “Minimum charge includes $20 for the SIM plus $20 Prepayment Outside Included Value” below the headline offer is written in small print. It cannot be described as conveying a dominant message. Rather, its purpose within the webpage is to explain why the minimum charge for the first month of the plan exceeds the monthly charge for the plan by $40. It can be accepted that a consumer reading that phrase would not know how the prepayment is to be used and applied, other than knowing that it is a mandatory payment and that it relates to services outside the included value within the plan. To know more, the consumer would need to read further. A short way below that phrase on the webpage is the hyperlink to the Critical Information Summary. The Summary provides further information concerning services within the “included value” of the plan. It states clearly that other usage charges are taken out of the prepayment. It also states clearly that the prepayment will be automatically topped up if it falls to below $10. The Summary then states that TPG’s (mobile) services are supplied on a rolling month to month basis; that customers are permitted to terminate the acquisition of the service at any time; but if the service is terminated, the customer will forfeit any prepayments already made. In our view, the Critical Information Summary clearly and directly answers the question that a customer may have about the prepayment: upon cancellation of the service, the balance of the prepayment will be forfeited.

(b) Similar observations can be made about the webpage reproduced as Annexure 2 (which we infer is the second step in the purchasing journey). On the line below the headline offer, in relatively small type, there appears the statement: “1st month minimum charges on TPG no lock-in contract Mobile plans calculated as: $(Mobile monthly charge in first month) + $20 SIM charge + $20 Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value”. Again, the statement cannot be described as conveying a dominant message and its purpose within the webpage is to explain why the minimum charge for the first month of the plan exceeds the monthly charge for the plan by $40. It conveys nothing about how the prepayment is to be used and applied (other than that it is a mandatory payment for services outside the included value within the plan). The use of the hyperlink reinforces that an explanation of the terms of the prepayment is to be found elsewhere on the website. The hyperlink takes the viewer a short way down the page to where the Prepayment Terms are set out. We reject the ACCC’s characterisation of the Prepayments Terms as a “long, wordy, complex and dull clause”. It is not excessively long and is written in commendably plain English. It contains a clear statement that the prepayment will be forfeited to TPG when the customer cancels the service, contradicting the central tenet of the ACCC’s case.

(c) Annexure 3 depicts the third stage of the purchasing journey when a customer is selecting their plan. On the second page, under the prominent heading “Prepayment is required”, the following sentence appears: “Prepayment of $20 is required for usage that is not part of the included value (e.g. excess data or excluded usage)”. Senior Counsel for the ACCC described this statement as the best example. While it can be accepted that the font size of that sentence is larger than some of the other examples relied on by the ACCC, we do not accept that the words, in the context in which they are used, convey the Prepayment Representations. The words convey the message, previously stated in the webpages reproduced as Annexures 1 and 2, that a customer who wishes to sign up to the plan is required to make a prepayment of $20 which will be applied towards usage that is not part of the included value. The words convey no more and do not answer the question of what is to happen to the balance of the prepayment upon cancellation of the plan. The explanation for that is provided a short way down the page in the section headed “Important Things You Need To Know”. There is nothing misleading in that presentation of information to the customer. Nor do we accept the ACCC’s submission that the statements, under the heading “Important Things You Need To Know”, describing excess data and the charges made for using excess usage, convey the Prepayment Representations. While those statements explain that TPG will take such charges from the prepayment, the statements say nothing about the return of the prepayment at the end of the plan. That topic is addressed, in a clear and intelligible manner, in the Prepayment Terms which follow a short way down the document.

(d) Annexure 4 contains the Critical Information Summary, which was a hyperlink from the first webpage reproduced in Annexure 1, and is referred to earlier. The information contained in the summary is to the same effect as already discussed. The statement on which the ACCC relied, that “other usage charges are taken out of your prepayment”, is an accurate statement. Again, it conveys nothing about the return of the prepayment at the end of the plan. That topic is addressed under the immediately following heading “Minimum Term”, where the customer is informed that they are permitted to terminate the plan at any time, but will forfeit any prepayments already made. There is nothing misleading about the information that is communicated.

(e) Annexure 5 is an extract from TPG’s brochure concerning its mobile plans. It contains materially the same information as on the website which has been considered above. Further, the Prepayment Terms are reproduced in a manner that has equal prominence with all other statements relied on by the ACCC. In our view, and for reasons already expressed, the Prepayment Representations are not conveyed by this page.

41 The ACCC placed some emphasis on the Forfeiture Term within the Prepayment Terms which were published in a number of places (see Annexures 2, 3 and 5). The Forfeiture Term stated that: “If you do not use the prepayment, it will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service”. The ACCC argued that the phrase “if you do not use the prepayment” implied that a customer would be able to use all of the prepayment prior to cancellation, which in the ordinary case would not occur (because of the automatic top-up when the balance got to $10). We agree that the expression of the Forfeiture Term could possibly be made clearer. For example, it could have been worded: “The balance of the prepayment will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service”, or other syntactical variations of that sentence. However, we do not consider that the Forfeiture Term was false or misleading. It was accurate in its own terms, in that any amount of the prepayment that was not used would be forfeited when the customer cancelled the service. While it did not spell out in terms that, in the ordinary course, a minimum amount of $10 would be forfeited, in our view the Forfeiture Term sufficiently conveyed to customers the contractual condition that the outstanding balance of the prepayment would be forfeited at the end of the plan. Most importantly, we do not consider that the Forfeiture Term conveyed the Prepayment Representations alleged by the ACCC; in our view, it conveyed a contrary message.

42 Finally, we do not consider that clause 7.1 of TPG’s standard terms and conditions takes the ACCC’s case any further.

Conclusion

43 In conclusion, we agree with the primary judge that the pages of TPG’s website and brochure relied on by the ACCC do not convey the Prepayment Representations. That conclusion results in the dismissal of the ACCC’s appeal.

I certify that the preceding forty-three (43) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Wigney, O'Bryan and Jackson. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE 1

ANNEXURE 2

ANNEXURE 3

ANNEXURE 4

annexure 5