FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nationwide News Pty Limited v Rush [2020] FCAFC 115

Appeal from: | |

File number: | NSD 679 of 2019 |

Judges: | WHITE, GLEESON AND WHEELAHAN JJ |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | DEFAMATION – appeal from judgment in respect of three publications found to be seriously defamatory – seven separate defamatory imputations – award of damages including interest totalling $2,872,753.10 – on appeal, apprehension of bias grounds wholly abandoned – whether the primary Judge erred in finding that two of the publications conveyed one of the pleaded imputations – whether the Judge erred in rejecting the appellants’ defence of justification, on the basis of credibility findings – whether the primary Judge had disavowed reliance on witness demeanour in making the credibility findings – whether the Judge erred in finding that the evidence of the appellants’ primary witness was unreliable –whether the Judge erred in finding that the evidence of the primary witness concerning the incidents alleged by the appellants was uncorroborated – whether the Judge erred in finding that a text sent by the respondent to the appellants’ primary witness was not inappropriate – whether the Judge erred in refusing leave to the appellants late in the trial to amend their filed defence so as to raise new particulars of justification. DAMAGES – assessment of damages for non-economic loss – aggravation of damage – Triggell v Pheeney – whether the pleading of a defence of truth was unjustified – whether publication of contents of defence in newspaper unjustified – matters published recklessly and in a sensationalised and extravagant manner where the appellants had not made adequate inquiries before publication of the matters and had not spoken to the complainant – defence alleging truth filed when the appellants had not still not spoken to the complainant – defence not capable of supporting imputations sought to be justified – no error by the Judge in finding that the conduct in pleading and then publishing allegations in the defence was unjustified. DAMAGES – assessment of damages for non-economic loss – proper construction of s 35 of the Defamation Act –whether the decision of the Victorian Court of Appeal in Bauer Media Pty Ltd v Wilson (No 2) [2018] VSCA 154; 3 VR 111 is plainly wrong – argument raised for the first time on appeal – whether expedient in the interests of justice to entertain argument – Bauer Media not shown to be plainly wrong. DAMAGES – assessment of damages for non-economic loss – whether the award of $850,000 for non-economic loss was manifestly excessive – imputations extremely serious – aggravation of harm by the appellants – respondent devastated and distressed – very high award of damages for non-economic loss warranted – little utility in comparing award with other cases – award of $850,000 not beyond what was appropriate. EVIDENCE – whether opinion evidence of witnesses who knew the respondent was admissible – whether there were undisclosed facts supporting opinions – no error in overruling objection. DAMAGES – assessment of damages for economic loss – whether respondent’s incapacity to earn income was pleaded – held that incapacity of the respondent to earn was pleaded and maintained at trial. EVIDENCE – principles in Jones v Dunkel – whether respondent gave evidence of the effect of the publications upon his capacity for work – whether any occasion to draw adverse inference – held that respondent gave evidence of the effect of the publications upon him – no occasion to draw adverse inference – reasons of Handley JA in Commercial Union Assurance Co of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 explained. DAMAGES – assessment of damages for future economic loss – choice of period over which future loss of earning capacity estimated – application of Malec v J C Hutton Pty Ltd [1990] HCA 20; 169 CLR 638 – no error by Judge in estimating future economic loss. |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 44, 66, 69, 135, 140 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 37M, 37N, 47A(1) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 2.32 Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) ss 3(a), 6, 25, 28, 29, 34, 35, 36 |

Cases cited: | Andrews v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd [1980] 2 NSWLR 225 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; 371 ALR 545 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Comalco Ltd (1986) 12 FCR 510 Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd [1993] HCA 15; 177 CLR 485 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hellicar [2012] HCA 17; 247 CLR 345 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2005] NSWSC 149; 190 FLR 242 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2005] NSWCA 152; 218 ALR 764 Bauer Media Pty Ltd v Wilson [2018] VSCA 68 Bauer Media Pty Ltd v Wilson (No 2) [2018] VSCA 154; 56 VR 674 Berrigan Shire Council v Ballerini [2005] VSCA 159; 13 VR 111 Bibby Financial Services Australia Pty Limited v Sharma [2014] NSWCA 37 Bickel v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd [1981] 2 NSWLR 474 Brandi v Mingot (1976) 12 ALR 551 Braverus Maritime Inc v Port Kembla Coal Terminal Ltd [2005] FCAFC 256; 148 FCR 68 Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 Canale v GW and R Mould Pty Ltd [2018] VSCA 346 Carson v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd [1993] HCA 31; 178 CLR 44 Cassell & Co Ltd v Broome [1972] AC 1027 Cerutti v Crestside [2014] QCA 33 Cerutti v Crestside Pty Ltd [2016] QCA 33; 1 Qd R 89 Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd [1998] HCA 37; 193 CLR 519 Chulcough v Holley [1968] ALR 274; 41 ALJR 336 Commercial Union Assurance Co of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 Commonwealth v Amann Aviation Pty Ltd [1991] HCA 54; 174 CLR 64 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 Concrete Pty Ltd v Parramatta Design & Developments Pty Ltd [2006] HCA 55; 229 CLR 577 Costello v Random House Australia Pty Ltd [1999] ACTSC 13; 137 ACTR 1 Coulton v Holcombe [1986] HCA 33; 162 CLR 1 Coyne v Citizen Finance [1991] HCA 10; 172 CLR 211 Crampton v Nugawela (1996) 41 NSWLR 176 Cripps v Vakras [2014] VSC 279 Cummings v Fairfax Digital Australia and New Zealand Pty Ltd [2018] NSWCA 325; 366 ALR 727 Dasreef Pty Ltd v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21; 243 CLR 588 David Syme v Mather [1977] VR 516 Ex parte Harper; Re Rosenfield [1964-5] NSWR 58 Ex parte Harper; Re Rosenfield [1964-5] NSWR 1831 Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Gayle [2019] NSWCA 172; 372 ALR 287 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings [2012] HCA 55; 250 CLR 503 Forrest v Askew [2007] WASC 161 Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 Garcia v National Australia Bank Ltd [1998] HCA 48; 194 CLR 395 Gayle v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] NSWSC 1838 Harbour Radio Pty Ltd v Tingle [2001] NSWCA 194 House v The King [1936] HCA 40; 55 CLR 499 Jadwan Pty Ltd v Rae & Partners (A Firm) [2020] FCAFC 62 Jadwan Pty Ltd v Rae & Partners (A Firm) (No 2) [2020] FCAFC 95 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298 Kingsfield Holdings Pty Ltd v Sullivan Commercial Pty Ltd [2013] WASC 347 KSMC Holdings Pty Ltd v Bowden [2020] NSWCA 28 Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; 243 CLR 361 Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; 372 ALR 383 Leech v Green & Gold Energy Pty Ltd [2011] NSWSC 999 Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water Corp v Di Masi [2014] VSCA 104; 43 VR 348 Mahony v J Kruschich (Demolitions) Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 37; 156 CLR 522 Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; 52 NSWLR 705 Malec v J C Hutton Pty Ltd [1990] HCA 20; 169 CLR 638 Martin v Norton Rose Fulbright Australia (No 2) [2020] FCAFC 42 McDonald’s Corp v Steel [1995] 3 All ER 615 Milliman v Rochester Ry Co 3 App Div 109; 39 NYS 274 (1896) Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; 264 CLR 541 Murray v Raynor [2019] NSWCA 274 Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Rush [2018] FCAFC 70 Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66; 110 ALR 449 New South Wales v Ibbett [2006] HCA 57; 229 CLR 638 Nikolaou v Papasavas, Phillips & Co [1989] HCA 11; 166 CLR 394 O’Donnell v Reichard [1975] VR 916 Paff v Speed [1961] HCA 14; 105 CLR 549 Pahuja v TCN Channel Nine (No 2) [2016] NSWSC 1074 Planet Fisheries Pty Ltd v La Rosa [1968] HCA 62; 119 CLR 118 Poniatowska v Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd (No. 2) [2020] SASCFC 5 Praed v Graham (1889) 24 QBD 53 R v E (1996) 39 NSWLR 450 R v Sorby [1986] VR 753 Random House Australia Pty Ltd v Abbott [1999] FCA 1538; 94 FCR 296 Ratcliffe v Evans [1892] 2 QB 524 Rayney v Western Australia (No 9) [2017] WASC 367 Re Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust [1991] FCA 344; 30 FCR 491 Rigby v Associated Newspapers [1969] 1 NSWR 729 Rizhao Steel Holding Group Co Ltd v Koolan Iron Ore Pty Ltd [2012] WASCA 50; 287 ALR 315 Rogers v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2003] HCA 52; 216 CLR 327 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 357; 359 ALR 473 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 550; 359 ALR 564 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Limited (No 5) [2018] FCA 1622 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 6) [2018] FCA 1851 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 8) [2019] FCA 1382 Sparks v Hobson [2018] NSWCA 29; 361 ALR 115 Stallion (NSW) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia [2019] FCA 1306 Steele v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1974] 2 NSWLR 348 Sutcliffe v Pressdram Ltd [1991] 1 QB 153 Teubner v Humble [1963] HCA 11; 108 CLR 491 The Herald & Weekly Times Ltd v McGregor [1928] HCA 36; 41 CLR 254 The Herald & Weekly Times Ltd v Popovic [2003] VSCA 161; 9 VR 1 Triggell v Pheeney [1951] HCA 23; 82 CLR 497 University of Wollongong v Metwally (No 2) [1985] HCA 28; 60 ALR 68 Uren v John Fairfax & Sons Pty Ltd [1966] HCA 40; 117 CLR 118 Vakras v Cripps [2015] VSCA 193 Wagner v Harbour Radio [2018] QSC 201 Wagner v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd [2019] QSC 284 Water Board v Moustakas [1988] HCA 12; 180 CLR 491 Weatherup v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2016] QSC 266 Woolcott v Seeger [2010] WASC 19 Zierenberg v Labouchere [1893] 2 QB 183 Zwambila v Wafawarova [2015] ACTSC 171 Collins on Defamation (Oxford University Press, 2014) Gatley on Libel and Slander (12th edition, Sweet & Maxwell) Spencer Bower, The Law of Actionable Defamation (2nd edition, 1923) Wigmore on Evidence (3rd edition, 1940) |

Registry: | New South Wales |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Solicitor for the Appellants: | Ashurst Australia |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr B Walker SC with Ms S Chrysanthou |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | HWL Ebsworth Lawyers |

ORDERS

First Appellant JONATHAN MORAN Second Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. On or before 10 July 2020 the legal practitioners for the parties confer in relation to the question of costs of the appeal, and the form of orders as to costs that the Court should make.

3. On or before 17 July 2020 the parties file and serve any submissions as to costs, not to exceed three pages.

4. On or before 24 July 2020 the parties file and serve any submissions as to costs in reply, not to exceed three pages.

5. If the parties at any relevant point file an agreed note as to costs, further compliance with Orders 2 to 4 above is dispensed with.

6. Subject to any further order, the question of costs shall be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 Between 28 November 2015 and 9 January 2016, the Sydney Theatre Company (STC) performed the Shakespearean tragedy King Lear at the Roslyn Packer Theatre in Sydney. The respondent to the appeal, Mr Rush, who is a well-known actor, played the role of King Lear. Ms Erin Jean Norvill played the role of Cordelia.

2 Just under two years later, the first appellant, Nationwide News Pty Limited (Nationwide News), published three matters concerning Mr Rush’s conduct during the STC production of King Lear. Two of the publications were editions of The Daily Telegraph newspaper and the third a billboard poster. The second appellant, Mr Moran, was the author of the articles concerning Mr Rush in the two editions of The Daily Telegraph. Although none of these publications mentioned Ms Norvill, it later became apparent that they had been prepared with reference to conduct of Mr Rush said to have been reported by Ms Norvill.

3 The primary Judge found that the three publications were seriously defamatory of Mr Rush (Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496) and, by orders made on 11 April, 10 May and 23 May 2019, awarded him damages including interest, totalling $2,872,753.10.

4 The appellants now appeal against that judgment. Their grounds of appeal are multiple: three complain of aspects of the conduct of the trial and, initially, included an allegation of apprehended bias; one complained of the finding that the publications conveyed one of the pleaded imputations; four complained of the Judge’s rejection of the defence of justification (which was the appellants’ sole substantive defence); and eight concerned aspects of the award of damages.

5 During the hearing of the appeal, the appellants wholly abandoned their grounds of appeal alleging apprehended bias.

6 We consider that all of the remaining grounds of appeal fail and that the appeal must be dismissed. Our reasons follow.

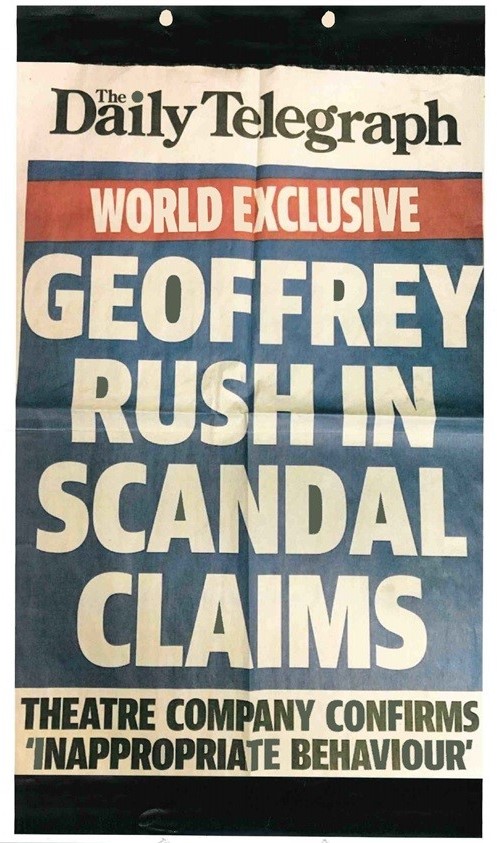

7 The poster (the first impugned matter) was published on 30 November 2017 and, in large bold font, promoted the edition of “The Daily Telegraph” published that same day:

The Daily Telegraph WORLD EXCLUSIVE GEOFFREY RUSH IN SCANDAL CLAIMS THEATRE COMPANY CONFIRMS ‘INAPPROPRIATE BEHAVIOUR’ |

8 The poster is reproduced in Annexure A to these reasons.

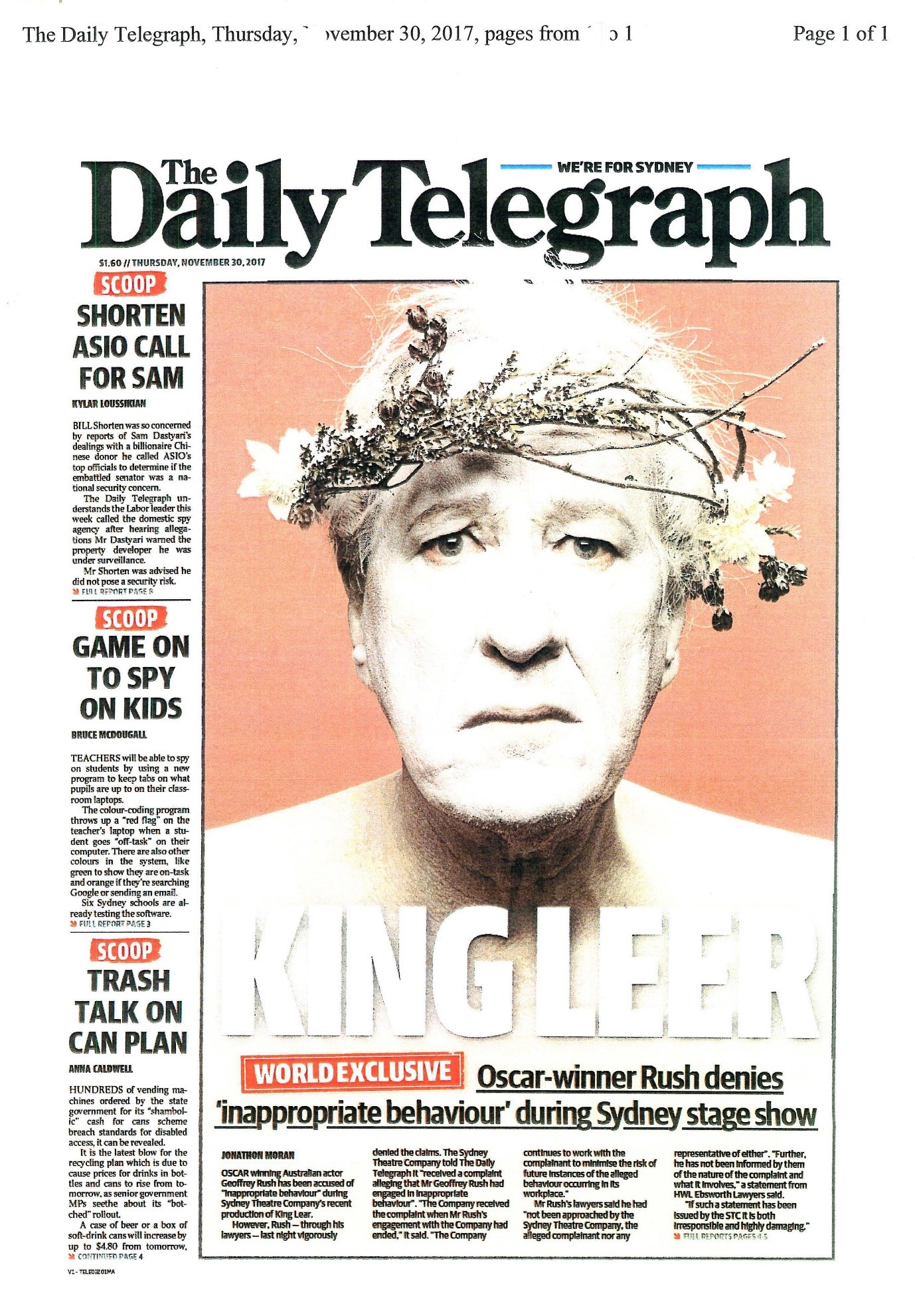

9 The second publication was the edition of The Daily Telegraph on 30 November 2017 (the second impugned matter). On its front page, it featured a large photograph of a bewildered looking Mr Rush dressed as King Lear with the title “KING LEER”. The heading to the accompanying article on the front page, under the photograph of Mr Rush, was “WORLD EXCLUSIVE Oscar-winner Rush denies ‘inappropriate behaviour’ during Sydney stage show”. The article reported that Mr Rush had been accused of “inappropriate behaviour” during the STC production of King Lear, and reported that Mr Rush denied the truth of the allegations.

10 The text of the article on the front page of The Daily Telegraph on 30 November 2017 was as follows:

OSCAR winning Australian actor Geoffrey Rush has been accused of “inappropriate behaviour” during Sydney Theatre Company’s recent production of King Lear.

However, Rush – through his lawyers – last night vigorously denied the claims. The Sydney Theatre Company told The Daily Telegraph it “received a complaint alleging that Mr Geoffrey Rush had engaged in inappropriate behaviour”. “The Company received the complaint when Mr Rush’s engagement with the Company had ended,” it said. “The Company continues to work with the complainant to minimise the risk of future instances of the alleged behaviour occurring in its workplace.”

Mr Rush’s lawyers said he had “not been approached by the Sydney Theatre Company, the alleged complainant nor any representative of either”. “Further, he has not been informed by them of the nature of the complaint and what it involves,” a statement from HWL Ebsworth Lawyers said.

“If such a statement has been issued by the STC it is both irresponsible and highly damaging.”

11 The front page of The Daily Telegraph published on 30 November 2017 is reproduced as Annexure B to these reasons.

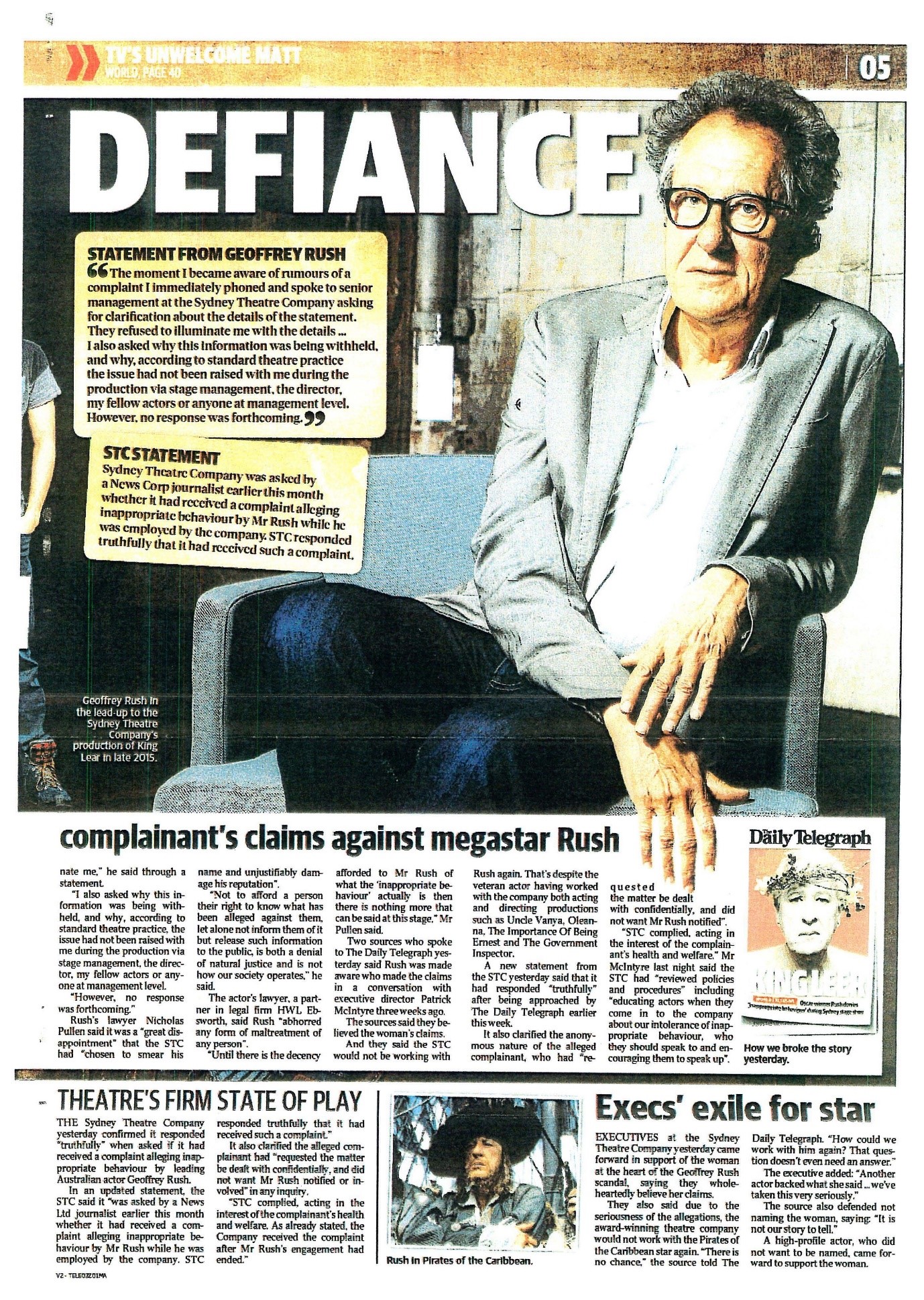

12 Pages four and five of the same edition of The Daily Telegraph contained a two page spread concerning Mr Rush. These pages had at their head an overline in white against a red background stating “Oscar-winner Geoffrey Rush denies complaint made in Sydney Theatre Shakespeare production”. Page four had a large bold headline “STAR’S BARD BEHAVIOUR”. An article concerning Mr Don Burke, who had been accused, amongst other things, of being a “sexual predator”, was printed on page five immediately adjacent to the article concerning Mr Rush.

13 The text of the article on pages 4 and 5 concerning Mr Rush was as follows:

OSCAR-winning Australian actor Geoffrey Rush has been accused of “inappropriate behaviour” during the Sydney Theatre Company’s recent production of King Lear.

But the star vigorously denies the allegations and says the company has never told him of any allegations of wrong doing.

The Daily Telegraph can today reveal that one of the country’s most successful actors was the subject of a complaint during the production of King Lear.

It is understood the allegations of inappropriate behaviour occurred over several months. The local production of the classic William Shakespeare play ran from November 2015 to January 2016 at the Roslyn Packer Theatre.

There were also several months of rehearsals.

“Sydney Theatre Company received a complaint alleging that Mr Geoffrey Rush had engaged in inappropriate behaviour,” a spokeswoman said to The Daily Telegraph.

“The Company received the complaint when Mr Rush’s engagement with the Company had ended. The Company continues to work with the complainant to minimise the risk of future instances of the alleged behaviour occurring in its workplace.

“The complainant has requested that their identity be withheld.

“STC respects that request and for privacy reasons, will not be making any further comments.”

In a strongly worded legal letter, lawyers for Rush at HWL Ebsworth last night said he had never been involved in any “inappropriate behaviour” and that his “regard, actions and treatment of all the people he has worked with has been impeccable beyond reproach.

“Mr Rush has not been approached by the Sydney Theatre Company and the alleged complainant nor any representative of either of them concerning the matter you have raised,” the letter states.

“Further, he has not been informed by them of the nature of the complaint and what it involves.”

The letter from the legal firm’s partner Nicholas Pullen goes on to say that Rush has not been involved with the Sydney Theatre Company or its representatives for a period of more than 22 months.

“In the circumstances, if such a statement has been issued by the STC it is both irresponsible and highly damaging to say the least.

“Your ‘understanding’ of what has occurred is, with the greatest respect, simply fishing and unfounded.

“It does not warrant comment except that it is false and untrue.”

Rush has worked with the STC many times – both acting and directing productions like Uncle Vanya, Oleanna, The Importance of Being Ernest, You Can’t Take It With You, King Lear and The Government Inspector.

Rush won the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1996 for his role as David Helfgott in the movie Shine and was nominated for the best supporting actor role two years later for Shakespeare in Love.

His other Oscar nominations include best actor in 2000 film Quills and for The King’s Speech in 2011 in the same category.

He has found fame for becoming one of the few people to have won acting’s “Triple Crown” – the Academy Award, the Primetime Emmy Award and the Tony Award.

The 66-year-old married father-of-two and Melbourne resident is also the president of the Australian Academy of Cinema Television and Arts and is expected to attend the annual AACTA Awards at The Star Event Centre next week.

14 Pages 4 and 5 of the second impugned matter are reproduced as Annexure C to these reasons.

15 The third publication was the edition of The Daily Telegraph of 1 December 2017 (the third impugned matter). Under the front page heading “WE’RE WITH YOU”, The Daily Telegraph reported that two STC actors had spoken in support of the then unnamed actress who had accused Mr Rush of touching her inappropriately during the production of King Lear. The full text of the article on page 1 of the 1 December 2017 edition was as follows:

TWO Sydney Theatre Company actors yesterday spoke out in support of the actress who has accused Oscar winner Geoffrey Rush of touching her inappropriately during the stage production of King Lear.

Rush – one of Australia’s biggest stars – was yesterday continuing to vehemently deny the claims.

Meyne Raoul Wyatt, who also appeared in King Lear, said he believed the allegations. “I believe (the person who) has come forward. It’s time for Sydney Theatre Company and the Industry in Australia and worldwide as a whole to make a stand,” Wyatt said.

And Brandon McClelland, who has worked alongside the actress, urged others to believe the complaints. “It wasn’t a misunderstanding,” he said.

Two STC sources said the company stood by her claims. Both said the company wouldn’t work with Rush again. Despite denials, Rush was told who made the claims in a phone call with executive director Patrick McIntyre weeks ago. Mr McIntyre last night said the STC had “reviewed policies” about “inappropriate behaviour”.

16 Pages four and five of The Daily Telegraph edition on 1 December 2017 also comprised a double page spread of articles relating to Mr Rush. Each article was written by Mr Moran. The first article had the heading “HR overhaul to lift curtain on bad deeds”. The text of that article was as follows:

THE Sydney Theatre Company has revised its HR policies in a bid to ensure it maintains a safe environment for staff.

Executive director of the STC Patrick McIntyre (below) said it was important actors feel safe to speak up and believes maintenance of confidentiality to be key.

“We have reviewed policies and procedures in place and that includes educating actors when they come in to the company about our intolerance of inappropriate behaviour, who they should speak to and encouraging them to speak up,” Mr McIntyre said.

Mr McIntyre’s comments come after the STC confirmed it had received a complaint by a staff member over allegations of “inappropriate behaviour” by Oscar winner Geoffrey Rush. Rush vehemently denies any wrongdoing.

Mr McIntyre stressed that he and the executive team at the theatre company have a duty of care to ensure all staff feel safe and respected in the workplace.

“This isn’t about creating drama and blame but if everyone holds each other accountable, we create the kind of workplace we all want to be in,” he said. More broadly, Mr McIntyre suggested it is a wideranging issue for the industry to address in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal.

“Many still view that speaking up comes with adverse repercussions,” he explained.

“This is a trust issue that the industry needs to work towards resolving and the observance of confidentiality is key to this. If people don’t trust us with their stories, they won’t speak up.”

The HR overhaul follows preliminary findings of an Actors Equity survey aimed at theatre actors which found that 40 per cent of respondents claimed they had directly experienced sexual harassment, bullying or misconduct.

Oscar winner Kevin Spacey became embroiled in the ongoing controversy rocking the entertainment industry with numerous victims coming forward – including 20 complaints from his time as artistic director at London’s Old Vic Theatre between 2004 and 2015.

A law firm’s investigation into allegations about Spacey stated: “Despite having the appropriate escalation processes in place, it was claimed that those affected felt unable to raise concerns and that Spacey operated without sufficient accountability.”

17 A second article under the heading “ACTS OF DEFIANCE” referred to the support provided by two actors who had worked with the actress making accusations against Mr Rush. The full text of that article is as follows:

TWO actors who work with the Sydney Theatre Company yesterday publicly threw their support behind the actress who has accused Oscar-winner Geoffrey Rush of touching her inappropriately during the stage production of King Lear.

It comes as Rush – one of the country’s most successful actors – was yesterday continuing to vehemently deny claims he inappropriately touched a cast member of the local production of the classic William Shakespeare play.

Rising young actor Meyne Raoul Wyatt, who appeared in King Lear, said he believed his castmate’s version of events.

“I was in the show,” Wyatt, who has also starred in Neighbours and Redfern Now, wrote on Facebook yesterday after The Daily Telegraph broke the story.

“I believe (the person who) has come forward. It’s time for Sydney Theatre Company and the industry in Australia and worldwide as a whole to make a stand on this behaviour!!!!”

And Brandon McClelland, who has worked alongside the woman at the centre of the alleged complaint and is in the company’s current production of Three Sisters, urged others on Twitter to believe the actress.

“It wasn’t a misunderstanding. It wasn’t a joke,” he posted.

McClelland’s tweet was also reposted by several other Sydney theatre actors as the story dominated social media yesterday.

The STC production of King Lear ran from November 2015 to January 2016.

The 66-year-old acting legend yesterday said he “immediately phoned and spoke to senior management” at the STC when he became aware of rumours there was a complaint.

But he said the STC refused to give him any details.

“They refused to illuminate me,” he said through a statement.

“I also asked why this information was being withheld, and why, according to standard theatre practice, the issue had not been raised with me during the production via stage management, the director, my fellow actors or anyone at management level.

“However, no response was forthcoming.”

Rush’s lawyer Nicholas Pullen said it was a “great disappointment” that the STC had “chosen to smear his name and unjustifiably damage his reputation”.

“Not to afford a person their right to know what has been alleged against them, let alone not inform them of it but release such information to the public, is both a denial of natural justice and is not how our society operates,” he said.

The actor’s lawyer, a partner in legal firm HWL Ebsworth, said Rush “abhorred any form of maltreatment of any person”.

“Until there is the decency afforded to Mr Rush of what the ‘inappropriate behaviour’ actually is then there is nothing more that can be said at this stage.” Mr Pullen said.

Two sources who spoke to The Daily Telegraph yesterday said Rush was made aware who made the claims in a conversation with executive director Patrick McIntyre three weeks ago.

The sources said they believed the woman’s claims.

And they said the STC would not be working with Rush again. That’s despite the veteran actor having worked with the company both acting and directing productions such as Uncle Vanya, Oleanna, The Importance Of Being Ernest and The Government Inspector.

A new statement from the STC yesterday said it had responded “truthfully” after being approached by The Daily Telegraph earlier this week.

It also clarified the anonymous nature of the alleged complainant, who had “requested the matter be dealt with confidentially, and did not want Mr Rush notified”.

“STC complied, acting in the interest of the complainant’s health and welfare.” Mr McIntyre last night said the STC had “reviewed policies and procedures” including “educating actors when they come in to the company about our intolerance of inappropriate behaviour, who they should speak to and encouraging them to speak up”.

18 A third article appeared under the heading “Statement for acting veteran blasts STC ‘smear’”. Its full text was as follows:

MANAGEMENT for Oscar-winning actor Geoffrey Rush issued a comprehensive statement yesterday denying allegations of “inappropriate behaviour” during the 66-year-old veteran actor’s time with the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of King Lear.

The statement, following The Daily Telegraph’s exclusive report yesterday, took aim at the Sydney Theatre Company, alleging that it had “chosen to smear his name and unjustifiably damage his reputation”.

It also claimed that: “His treatment of fellow colleagues and everyone he has worked with is always conducted with respect and the utmost propriety.

“The allegation made against Mr Rush comes from a statement provided by the Sydney Theatre Company,” it reads.

The widely released document says it is understood that the STC’s own statement concerns a complaint made to it more than 21 months ago.

“To date, Mr Rush or any of his representatives have not received any representations from the STC or the complainant.

“In other words, there has been no provision of any details, circumstances, allegations or events that can be meaningfully responded to.”

It goes on to quote Mr Rush:

“The moment I became aware of rumours of a complaint I immediately phoned and spoke to senior management at the Sydney Theatre Company asking for clarification about the details of the statement.

“They refused to illuminate me with the details.”

The statement then says Mr Rush can only reiterate that he denies being involved in any “inappropriate behaviour” whatsoever.

19 A fourth article had the heading “THEATRE’S FIRM STATE OF PLAY”. The text of that article was as follows:

THE Sydney Theatre Company yesterday confirmed it responded “truthfully” when asked if it had received a complaint alleging inappropriate behaviour by leading Australian actor Geoffrey Rush.

In an updated statement, the STC said it “was asked by a News Ltd journalist earlier this month whether it had received a complaint alleging inappropriate behaviour by Mr Rush while he was employed by the company. STC responded truthfully that it had received such a complaint.”

It also clarified the alleged complainant had “requested the matter be dealt with confidentially, and did not want Mr Rush notified or involved” in any inquiry.

“STC complied, acting in the interest of the complainant’s health and welfare. As already stated, the Company received the complaint after Mr Rush’s engagement had ended.”

20 The final article appeared under the heading “Execs’ exile for star”. The text of that article was as follows:

EXECUTIVES at the Sydney Theatre Company yesterday came forward in support of the woman at the heart of the Geoffrey Rush scandal, saying they wholeheartedly believe her claims.

They also said due to the seriousness of the allegations, the award-winning theatre company would not work with the Pirates of the Caribbean star again. “There is no chance,” the source told The Daily Telegraph. “How could we work with him again? That question doesn’t even need an answer.”

The executive added: “Another actor backed what she said … we’ve taken this very seriously.”

The source also defended not naming the woman, saying: “It is not our story to tell.”

A high-profile actor, who did not want to be named, came forward to support the woman.

21 The two page spread contained five photographs of Mr Rush.

22 Pages 4 and 5 of the 1 December 2017 edition of The Daily Telegraph are reproduced in Annexure D to these reasons.

23 In the weeks preceding 30 November 2017, the events which gave rise to the #MeToo movement had occurred. The Hollywood film producer, Harvey Weinstein had been portrayed in public and social media as a sexual predator who had committed acts of sexual assault and/or sexual harassment. The Hollywood actor Kevin Spacey had also been portrayed as a sexual predator who had committed acts of sexual assault and/or sexual harassment. Those events formed part of the context on which Mr Rush relied in alleging that he had been defamed.

The STC production of King Lear

24 The STC production of King Lear was directed by the well-known theatre director, Mr Neil Armfield AO. The Judge accepted that Mr Armfield is a close colleague and friend of Mr Rush.

25 As already indicated, Mr Rush played the lead role of King Lear and Ms Norvill played the role of Cordelia, one of King Lear’s three daughters.

26 Ms Helen Buday played the role of Goneril, the eldest of King Lear’s daughters. Ms Helen Thomson played the role of Regan, the third of King Lear’s daughters.

27 Ms Robyn Nevin AM played the role of the Fool.

28 Mr Max Cullen played the role of the Earl of Gloucester, Mr Alan Dukes the role of the Duke of Albany, Mr Nick Masters the role of the Duke of Burgundy, Mr Colin Moody the role of the Duke of Cornwall, and Mr Jacek Koman the role of the Earl of Kent.

29 Mr Mark Winter played the role of Edgar, the Earl of Gloucester’s legitimate son. Mr Meyne Wyatt played the role of Edmund, the main antagonist in the play and illegitimate son of the Earl of Gloucester. Mr Wade Briggs played the role of Oswald and Mr Eugene Gilfedder played the Knight and messenger. Mr Simon Barker and Mr Phillip Slater played the role of two musicians. The Judge found that, in addition to this cast of 14, a large number of other people were directly involved in one way or another in the production. The total number involved in the production was of the order of 45.

30 The STC commenced rehearsals for the performance on 12 October 2015. Four preview performances of the play were presented before full audiences between 24 and 27 November 2015. As indicated, the STC presented its production of King Lear between 28 November 2015 and 9 January 2016, both dates inclusive.

31 The final scene in King Lear involves Lear grieving over the body of Cordelia who has been killed by Edmund’s betrayal. In the STC production, Mr Rush carried Cordelia’s body (Ms Norvill) on stage from a position just off stage, lay her on the floor and then, while engaged in dialogue with Mr Dukes, mourned over her body. This involved Mr Rush touching Ms Norvill. Much of the evidence on which the appellants relied for the defence of justification concerned the conduct of Mr Rush which was said to have occurred in the rehearsals for, and the performance of, this final scene.

The findings of the primary Judge

32 The trial of the action occupied some 15 days. In addition to his own evidence, Mr Rush led evidence from Mr Armfield, Ms Nevin, Ms Buday, Mr Fred Schepisi AO (the film director), Mr Fred Specktor (Mr Rush’s American agent), Ms Robyn Russell (an American media attorney), Mr Michael Potter (a forensic accountant) as well as seven other “reputation” witnesses, including his wife Ms Jane Menelaus, who gave evidence of Mr Rush’s reputation and of their observations of him. The appellants led evidence from Ms Norvill, Mr Winter, Mr Richard Marks (an American media attorney) and from Mr Tony Samuel (a forensic accountant).

33 The Judge found that each of the three publications conveyed imputations which were defamatory of Mr Rush.

34 In relation to the billboard poster, the Judge found that it conveyed the imputation that Mr Rush had engaged in scandalously inappropriate behaviour in the theatre, at [217]. Although the appellants had denied on their pleadings that the poster did convey this meaning, they accepted at the trial that this imputation had been conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader, at [115].

35 The Judge found that the articles published on 30 November 2017 conveyed the following imputations, at [61] and [218]:

(a) that Mr Rush is a pervert;

(b) that Mr Rush behaved as a sexual predator while working on the STC’s production of King Lear;

(c) that Mr Rush engaged in inappropriate behaviour of a sexual nature while working on the STC’s production of King Lear; and

(d) that Mr Rush, a famous actor, engaged in inappropriate behaviour against another person over several months while working on the STC’s production of King Lear.

36 The Judge found that the articles published on 1 December 2017 conveyed the following imputations, at [64] and [219]:

(a) Mr Rush had committed sexual assault while working on the STC’s production of King Lear;

(b) Mr Rush behaved as a sexual predator while working on the STC’s production of King Lear;

(c) Mr Rush engaged in inappropriate behaviour of a sexual nature while working on the STC’s production of King Lear;

(d) Mr Rush had inappropriately touched an actress while working on the STC’s production of King Lear;

(e) Mr Rush is a pervert;

(f) Mr Rush’s conduct in inappropriately touching an actress during King Lear was so serious that the STC would never work with him again; and

(g) Mr Rush had falsely denied that the STC had told him the identity of the person who had made a complaint against him.

37 With one or two exceptions, the appellants had denied at trial that either of the second or third impugned matters had conveyed the above imputations but, as indicated, that part of their defence was not successful. The appellants appeal against only one aspect of these findings of the Judge, namely, the finding that the second and third impugned matters conveyed the imputation that “the applicant is a pervert”.

38 The only substantive defence of the appellants at trial was the claim that all but one of the imputations alleged by Mr Rush were substantially true. They alleged that he had in fact engaged in scandalously inappropriate behaviour of a sexual nature in the theatre; that he had in fact committed sexual assault in the theatre; that he was in fact a pervert; that he had in fact behaved as a sexual predator; and that he had inappropriately touched an actor while working on the STC’s production of King Lear.

39 These contentions were based on claims that Mr Rush had, during the STC production of King Lear, amongst other things, made lewd gestures and acted in a sexually inappropriate and predatory manner towards Ms Norvill, that he had intentionally touched one of her breasts during one of the preview performances, and that he had touched Ms Norvill’s lower back as he was about to carry her on stage during the final scene in the play.

40 The Judge found that the appellants had not proved on the balance of probabilities the substantial truth of any of the imputations conveyed by the appellants’ publications and, accordingly, that their defence of justification failed. It followed that Mr Rush was entitled to an award of damages.

41 The Judge found that Mr Rush had an “exemplary reputation” prior to the appellants’ publications. The evidence of several witnesses called by Mr Rush supported that conclusion.

42 The Judge considered that the damage to Mr Rush’s reputation both in Australia and internationally had been substantial. His Honour considered that Mr Rush was entitled to a substantial award by way of compensatory damages, including aggravated damages. The Judge held that the assessment of the damages to which Mr Rush was entitled should take account of the circumstances in which the appellants had published the impugned matters as well as their conduct occurring thereafter. His Honour also considered that the cap on the amount which could be awarded for non-economic loss pursuant to s 35 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) was inapplicable, having regard to s 35(2). In the application of s 35(1) and (2), the Judge followed the decision of the Court of Appeal in Victoria in Bauer Media Pty Ltd v Wilson (No 2) [2018] VSCA 154; 56 VR 674 (Bauer Media).

43 The Judge awarded Mr Rush damages totalling $2,872,753.10 as follows:

non-economic loss including aggravated damages – $850,000;

past economic loss including pre-judgment interest – $1,060,773;

future economic loss – $919,678; and

pre-judgment interest on the non-economic loss – $42,302.10.

The Further Amended Notice of Appeal

44 The appellants’ Further Amended Notice of Appeal (FANA) filed on 5 July 2019 contained 20 grounds. Before the hearing of the appeal, the appellants abandoned Ground 20 and indicated that Ground 6 should be regarded as a particular of Ground 5. That meant that, at the commencement of the appeal hearing, the appellants were pursuing 18 grounds of appeal.

45 Those 18 grounds are in four categories:

(a) grounds concerning the Judge’s conduct of the trial (Grounds 1-5 and 7). These grounds include complaints that aspects of the conduct of the Judge during the trial gave rise to an apprehension of bias (Grounds 1-4), that by reason of seven matters, the Judge had denied the appellants procedural fairness (Ground 5), and that the Judge had erred in disallowing, on the 12th day of the trial, the application by the appellants to amend their defence so as to plead further matters of justification (Ground 7);

(b) the finding that the imputation that “the applicant is a pervert” had been conveyed by the second and third impugned matters (Ground 8);

(c) the rejection of the appellants’ defence of justification (Grounds 9-12); and

(d) the damages awards (Grounds 13-19).

46 The relief sought by the appellants in the FANA was the allowing of the appeal, the setting aside of the Judge’s orders giving effect to his award of damages and the entry of judgment in their favour. In the alternative, the appellants sought the remittal of the proceedings for retrial before a different Judge, together with the setting aside of three interlocutory orders made by the Judge which had been adverse to the appellants. During the course of the appeal hearing, the appellants’ position with respect to the relief they sought in the event that the appeal was successful in whole or in part, was modified.

The apprehension of bias grounds

47 It is appropriate to record some matters concerning the appellants’ claims of an apprehension of bias by the Judge, even though these claims were wholly abandoned by them during the afternoon of the first day of the two day appeal hearing.

48 Prior to the delivery of judgment on 11 April 2019 (which contained the award of $850,000 for non-economic loss and indicated the basis on which the awards for past and future economic loss should be computed), the appellants had not made any application that the Judge should recuse himself on the grounds of an apprehension of bias. On delivering judgment, the Judge listed a case management hearing for 10 May 2019. His Honour’s intended purpose in doing so was to hear from the parties concerning orders in relation to the filing of further evidence and submissions in respect of the assessment of the damages for economic loss and further submissions in relation to injunctive relief, costs and interest.

49 At the hearing on 10 May 2019, the appellants made an oral submission that the Judge should recuse himself from considering any further contested matters in the proceedings, in particular, Mr Rush’s application for further injunctive relief. The Judge then listed the appellants’ oral application for recusal and Mr Rush’s application for permanent injunctions for hearing on 20 May 2019. At the request of the parties, the hearing on that day was adjourned to 23 May 2019.

50 By 23 May 2019, the appellants had presented the Judge with the form of an interlocutory application seeking an order that he recuse himself from further determining the proceedings. His Honour granted the appellants leave to file the application and the hearing proceeded on the basis that they would do so. However, the application was not filed. At the conclusion of the submissions concerning the claimed apprehended bias, the Judge refused to recuse himself and said that he would publish reasons later. His Honour’s formal order on 23 May 2019 was that the “interlocutory application filed by the respondents dated 23 May 2019 seeking an order that his Honour Justice Wigney recuse himself from further determining the proceedings is dismissed”. Plainly, his Honour made the order in those terms in the belief that the appellants had exercised the leave granted to them. The Judge then determined the outstanding issues and made orders awarding Mr Rush damages for past and future economic loss, as well as orders concerning other matters, which it is not necessary to detail presently.

51 The first Notice of Appeal, which included four grounds alleging apprehended bias, was filed by the appellants on 1 May 2019. An Amended Notice of Appeal was filed on 7 June 2019 and the FANA was filed on 5 July 2019. Apart from two particulars which were abandoned, the effect of the amendments filed on 7 June and 5 July 2019 was, amongst other things, to enlarge the matters on which the appellants relied for their claims of apprehended bias.

52 An allegation of bias by a judge, whether actual or apprehended, is a serious matter. It should not be made lightly. In defamation proceedings in which an applicant is successful, special care should be exercised before such allegations are made. That is because claims of apprehended bias go to the very integrity of the trial process and are accordingly likely to undermine in the eyes of the public the vindication of the applicant’s reputation which the judgment represents. Junior counsel for Mr Rush drew attention to this effect on 10 May 2019 when the appellants first made their oral application that the Judge recuse himself.

53 The appellants’ intention to pursue claims of apprehended bias on the appeal was confirmed in the summary of submissions filed on 23 September 2019 in anticipation of the appeal hearing, by the appellants’ request that the Court listen to tapes of statements made by the Judge during the trial, and by the appellants’ senior counsel at the commencement of the appeal hearing.

54 At the appeal hearing, the Court drew the appellants’ attention to passages in Concrete Pty Ltd v Parramatta Design & Developments Pty Ltd [2006] HCA 55; 229 CLR 577. Kirby and Crennan JJ (with whom Gummow ACJ agreed on this point) said:

[117] … An intermediate appellate court dealing with allegations of apprehended bias, coupled with other discrete grounds of appeal must deal with the issue of bias first. It must do this because, logically, it comes first. Actual or apprehended bias strike at the validity and acceptability of the trial and its outcome. It is for that reason that such questions should be dealt with before other, substantive, issues are decided. It should put the party making such an allegation to an election on the basis that if the allegation of apprehended bias is made out, a retrial will be ordered irrespective of possible findings on other issues. Even if a judge is found to be correct, this does not assuage the impression that there was an apprehension of bias.

(Emphasis added)

55 It was apparent that the adoption of the approach stated by Kirby and Crennan JJ would cause the Court some difficulty in structuring a judgment in the particular circumstances of this case. However, it was necessary for the appellants to make the election of which their Honours spoke, as success by them on their claims of apprehended bias could not result in the primary relief which they sought, namely, the entry of judgment in their favour on Mr Rush’s claims.

56 Senior counsel then said that the appellants would consider their position in this respect.

57 Later that day, as already indicated, senior counsel informed the Court that the appellants no longer pressed the apprehension of bias claims nor the claim of denial of procedural fairness in Ground 5. After some further submissions, the Court invited the appellants to consider applying to amend the FANA so as to withdraw the grounds containing the claims of apprehended bias. On the following morning, the appellants made that application, and it was granted.

58 By the Second Further Amended Notice of Appeal (2FANA) filed on 5 November 2019, the appellants withdrew Grounds 1-6 inclusive and confirmed that Ground 20 was abandoned.

59 The appellants’ abandonment of its claims of apprehended bias and the amendment of the notice of appeal means that there is now no suggestion that the decision of the Judge was affected in the manner which the appellants once claimed. We note, moreover, that, at the time of the abandonment of the claim, the precise nature of the bias which it was said that the reasonable fair minded observer may have apprehended had not been made clear.

The imputation that Mr Rush was a “pervert” (Ground 8)

60 This ground relates to the Judge’s findings at [135] and [195] that the 30 November 2017 and 1 December 2017 articles conveyed the imputation that Mr Rush was a pervert. On the hearing of the appeal, senior counsel for the appellants accepted that this ground of appeal was relevant only to damages.

61 On the appeal, the appellants contended that the Judge had erred in rejecting their interpretation of the word “pervert”, being a person who is, by contemporary standards, a sexual deviant or someone who engages in sexual behaviour that would be regarded as not just offensive, but disgusting as well as bizarre. The appellants gave as an example, a “peeping Tom”. In contrast, according to the appellants, mere sexual harassment would not be properly described as “perverted”. The appellants argued that their interpretation is consistent with the dictionary definitions set out by the Judge at [138] of his Honour’s reasons which, his Honour acknowledged, “tended to involve some form of sexual abnormality or deviance”.

62 At [140] of the Judge’s reasons, his Honour stated –

[I]n my view the common or everyday meaning of “pervert” is somewhat broader than the rather narrow dictionary definitions. For example, the ordinary reasonable reader would be likely to consider that a person, particularly an older man, who leers at younger women or men in a lecherous, lewd or licentious manner, particularly in a workplace setting, would rightly be called a “pervert”. Indeed, in Australia at least, a man who engages in such behaviour is often called a “perv”, which is a colloquial or shortened form of the word “pervert”. The Macquarie Dictionary defines the colloquial expression “perv” (or “perve”) as a “sexual pervert” and the expression to “have a perv (perve)” as “to look at something, with or as if with lustful appreciation” or “to look lustfully”. The impression conveyed by the article was, at the very least, that Mr Rush was a “perv” or pervert in that sense.

(Emphasis added)

63 The appellants argued that the Judge wrongly equated the noun “pervert” with the slang verb “to perve”, submitting that, in ordinary language the two concepts are quite distinct. The appellants argued that the verb rarely connotes behaviour that ordinary members of society would regard as sexually deviant and may simply mean “to look lustfully”. To look lustfully might in some circumstances be regarded as reprehensible but not as the conduct of a sexual deviant. In contrast, a “pervert” or a person who is “perverted” is rarely, if ever, considered in a positive light.

64 The appellants submitted that the Judge wrongly concluded that, because the noun “perve” may be synonymous with “pervert”, the verb “perve” must therefore connote behaviour that is “sexually deviant or perverted”.

65 Mr Rush submitted that the imputation that he was a pervert followed from the other imputations found to be conveyed by the imputations, which included that he:

(a) behaved as a sexual predator;

(b) engaged in inappropriate behaviour of a sexual nature;

(c) committed sexual assault; and

(d) inappropriately touched an actress.

66 Mr Rush submitted that the Judge gave detailed reasons for finding that this imputation was conveyed by the second matter complained of (at [127]-[146]) and by the third matter complained of (at [195]-[201]), and for finding that the appellants were arguing for an elevated meaning of the word “pervert”, that is a meaning which was not the natural and ordinary meaning.

67 Although the Judge found the appellants’ interpretation of the imputation to be unduly narrow, his Honour also made findings adverse to them on the basis of that narrow interpretation. Thus, the appellants’ contention goes nowhere.

68 Specifically, as to the 30 November 2017 articles, the Judge found at [139] that the articles as a whole conveyed the impression that Mr Rush was someone who acted in a sexually abnormal or deviant way. His Honour found that the conduct conveyed was “more than just offensive and objectionable” and that, having regard to Mr Rush’s age and standing, it would also be considered by most ordinary reasonable people as sexually abnormal or deviant. His Honour also found that the suggestion that Mr Rush was a “sexual predator” also suggested some form of sexual abnormality or deviancy.

69 As to the 1 December 2017 articles, the Judge found at [200] that, even if the word “pervert” is to be given the narrow meaning contended for by the appellants, “the ordinary reasonable reader would be likely to consider that a senior actor who committed sexual assault, or behaved as a sexual predator, or engaged in inappropriate behaviour of a sexual nature, or inappropriately touched an actress, in the course of a major theatre production, had engaged in sexual conduct which was bizarre, unnatural or abnormal”.

70 In any event, we agree with the Judge that the ordinary reasonable reader is likely to consider a person who engaged in the conduct conveyed by the publications to be a “pervert”, particularly in so far as it concerned behaving as a sexual predator, and a man’s use of authority or stature in the workplace to obtain sexual gratification by inappropriately touching a non-consenting co-worker. On the Judge’s unchallenged findings, the relevant publications went well beyond suggesting that Mr Rush had “perved” on Ms Norvill.

71 Accordingly, this ground of appeal fails.

The rejection of the defence of justification

72 By [13] of their Second Further Amended Defence (2FAD) to Mr Rush’s Statement of Claim, the appellants alleged that all but one of the defamatory imputations alleged by Mr Rush were substantially true and thereby invoked s 25 of the Defamation Act and its interstate and Territory counterparts. The exception was the imputation pleaded in [10(g)] of the Statement of Claim, namely, that “[t]he applicant had falsely denied that the Sydney Theatre Company had told him the identity of the person who had made a complaint against him”. The appellants did not seek to justify that imputation.

73 At the trial, the appellants did not seek to justify another of the pleaded imputations, namely, the imputation pleaded in [10(f)] of the Statement of Claim that Mr Rush’s conduct in “inappropriately touching an actress during King Lear was so serious that the [STC] would never work with him again”. They accepted that Mr Rush was entitled to judgment on the imputations pleaded in [10(f)] and [10(g)] of the Statement of Claim.

74 The Judge recorded that it was the appellants who had the onus of proving on the balance of probabilities that the imputations conveyed by the impugned matters were substantially true and noted that, in considering the evidence, it was appropriate to have regard to the seriousness of the allegation made and the gravity of the consequences following from a particular finding. In this respect, the Judge referred to Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34, 60 CLR 336 at 362; Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66, 110 ALR 449 at 450 and to s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

75 The Judge noted that the allegations pleaded by the appellants in support of the defence of justification related entirely to Mr Rush’s behaviour towards Ms Norvill, at [230]. His Honour summarised the appellants’ particulars as involving eight key allegations and used the summary as the framework for his reasons concerning the plea of justification. It was not suggested that there was any error in the Judge’s summary. The eight matters were:

(i) on one occasion (pleaded to have occurred between about 26 and 30 October 2015) when Mr Rush and Ms Norvill were rehearsing the final scene of the play in which King Lear grieves over Cordelia’s dead body, Ms Norvill saw Mr Rush “hovering his hands over her torso and pretending to caress or stroke her upper torso” and then making “groping gestures in the air with two cupped hands, which gestures were intended to simulate and did in fact simulate him groping and fondling [Ms Norvill’s] breasts”, at [232]. That incident was said to have occurred in front of other members of the cast and perhaps crew;

(ii) during the rehearsal period from about 12 October to 23 November 2015, Mr Rush “regularly made comments or jokes about [Ms Norvill] or her body which contained sexual innuendo”, at [233]. This conduct was also said to have often occurred in the presence of members of the cast and crew;

(iii) during the rehearsal period, Mr Rush would “regularly (every few days) make lewd gestures in [Ms Norvill’s] direction” and “[o]n a number of occasions this comprised [Mr Rush] looking at [Ms Norvill], sticking his tongue out and licking his lips and using his hands to grope the air like he was fondling [Ms Norvill’s] hips or breasts”, at [234];

(iv) during a promotional interview with Elissa Blake, a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald, Mr Rush described having a “stage-door Johnny crush” on Ms Norvill, at [235];

(v) during a preview performance of the play between 24 and 27 November 2015, Mr Rush departed from the way that the last scene had been repeatedly rehearsed in that he “did not touch [Ms Norvill’s] hand and face … but rather [he] moved his hand so that it traced down [Ms Norvill’s] torso and across the side of her right breast”, at [236]. In relation to this allegation, the appellants also claimed that on the following day, the director of the play, Mr Armfield, had given Mr Rush an oral “note”, apparently in the presence of other cast members, by which he directed that Mr Rush should make his performance in the last scene more “paternal” as it was becoming “creepy and unclear”. Mr Armfield was also said to have directed Mr Rush not to stroke Ms Norvill’s body but to place his hand lightly on the side of her face and arm instead;

(vi) the sixth allegation concerned Mr Rush’s conduct during the final scene of the play in which, as already noted, he carried Ms Norvill onto the stage. Immediately before that occurred, Ms Norvill stood on a chair backstage in the prompt side wings so as to facilitate Mr Rush lifting her into his arms. The appellants alleged that, in a performance occurring between 14 and 26 December 2015, before lifting Ms Norvill from the chair, Mr Rush placed his hand on her lower back over her shirt, moved his hand under her shirt and along the waistline of her jeans, brushing across the skin of her lower back. The appellants alleged the movement to have been “light in pressure, slow and … deliberate”, and to have lasted for about 20-30 seconds, at [237];

(vii) this allegation concerned conduct similar to the sixth but was said to have occurred during a performance in the period between 4 and 9 January 2016. The appellants alleged that while Ms Norvill was standing on the chair, Mr Rush started to touch her lower back on top of her shirt and then gently rubbed his fingers over her lower back from right to left; and

(viii) on 10 June 2016, Mr Rush sent a text message to Ms Norvill in which he said that he thought about her “more than is socially appropriate”.

76 The Judge noted the appellants’ contention that the conduct of Mr Rush which they alleged was intentional and constituted scandalously inappropriate conduct in the workplace.

77 It was not in issue that Mr Rush had said, during the course of an interview with a journalist on 17 November 2015 promoting the STC performance of King Lear, that he had a “stage-door Johnny crush” on Ms Norvill. The evidence also established that Mr Rush had, on 10 June 2016, sent a text message to Ms Norvill in which he said, amongst other things, that he thought about her “more than is socially appropriate”. The Judge found, however, that neither of these statements supported the appellants’ plea of justification in relation to any of the pleaded imputations, at [526]-[529], [656].

78 The Judge found that the appellants had not proven any of the remaining six allegations, at [459], [502], [576], [610], [634].

79 The appellants called two witnesses to give evidence in support of the allegations they made in support of the plea of justification. These were Ms Norvill and Mr Mark Winter.

80 The evidence of Mr Winter was, the Judge noted, limited as it concerned only two of the matters on which the appellants relied, being (it seems) the first and the fifth, at [345].

81 This meant that the principal evidence on which the appellants relied for their defence of justification was that of Ms Norvill.

82 Mr Rush himself gave evidence concerning the appellants’ allegations and led evidence from three other witnesses: Mr Armfield, Ms Nevin and Ms Buday.

83 Before making his findings about each of the appellants’ allegations, the Judge made some general findings about the credibility and reliability of the six witnesses who gave evidence concerning them. We will return to some aspects of those findings shortly. For the present, however, we note that the Judge concluded that “[o]n the whole, … Mr Rush was a credible witness who gave honest and reliable evidence about the critical events in question”. His Honour regarded the evidence of Mr Armfield, Ms Buday and Ms Nevin as honest and reliable.

84 The Judge doubted the reliability and credibility of Ms Norvill’s evidence on critical matters. He gave detailed reasons for that conclusion. Many of the appellants’ submissions on the appeal were directed to these findings. Counsel for the appellants acknowledged that, in order for the appellants to succeed in their challenge to the Judge’s rejection of their defence of justification, it was necessary for them to show that the Judge’s findings concerning the credibility and reliability of Ms Norvill as a witness should be overturned. We will return to the Judge’s assessment of Ms Norvill’s evidence shortly.

85 As already noted, Mr Winter’s evidence was of relatively narrow compass. The Judge identified three matters which suggested “considerable doubt” about the reliability of his evidence generally. These were Mr Winter’s acknowledgement that his recollection of relevant events was “vague”, the fact that his description of the events in question was “not entirely consistent” with Ms Norvill’s evidence, and the “rather matter-of-fact way” in which Mr Winter had given his evidence.

The grounds of appeal concerning the defence of justification

86 Four of the appellants’ grounds of appeal concerned the Judge’s rejection of the defence of justification.

87 By Ground 9, the appellants contended that the Judge should have found that each of the six disputed incidents did occur and should have found that Mr Rush’s text of 10 June 2016 was “inappropriate”. The appellants did not challenge the Judge’s rejection of their defence concerning the “stage-door Johnny crush” comment.

88 By Ground 10, the appellants contended that the Judge had, in seven separate respects, erred in finding that Ms Norvill was “an unreliable witness prone to exaggeration and lacking in credibility”. Ground 11 is in effect a particular of Ground 10(b) because it is a complaint that the Judge had erred by relying on an email of 6 April 2016 from Ms Annelies Crowe (the Crowe email) in his assessment of the credibility of Ms Norvill. Ground 12 is in effect a particular of Ground 10(e) because it is a complaint concerning the Judge’s assessment of the evidence of Mr Winter, and of the extent to which it supported the evidence of Ms Norvill.

89 The approach required of an appellate court in determining challenges to findings of fact made by a trial judge is settled. In Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 at [25]-[29], Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ said:

[25] Within the constraints marked out by the nature of the appellate process, the appellate court is obliged to conduct a real review of the trial and, in cases where the trial was conducted before a judge sitting alone, of that judge's reasons. Appellate courts are not excused from the task of "weighing conflicting evidence and drawing [their] own inferences and conclusions, though [they] should always bear in mind that [they have] neither seen nor heard the witnesses, and should make due allowance in this respect". In Warren v Coombes, the majority of this Court reiterated the rule that:

"[I]n general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge. In deciding what is the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge but, once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it."

As this Court there said, that approach was "not only sound in law, but beneficial in … operation".

[26] After Warren v Coombes, a series of cases was decided in which this Court reiterated its earlier statements concerning the need for appellate respect for the advantages of trial judges, and especially where their decisions might be affected by their impression about the credibility of witnesses whom the trial judge sees but the appellate court does not. Three important decisions in this regard were Jones v Hyde, Abalos v Australian Postal Commission and Devries v Australian National Railways Commission. This trilogy of cases did not constitute a departure from established doctrine. The decisions were simply a reminder of the limits under which appellate judges typically operate when compared with trial judges.

[27] The continuing application of the corrective expressed in the trilogy of cases was not questioned in this appeal. The cases mentioned remain the instruction of this Court to appellate decision-making throughout Australia. However, that instruction did not, and could not, derogate from the obligation of courts of appeal, in accordance with legislation such as the Supreme Court Act applicable in this case, to perform the appellate function as established by Parliament. Such courts must conduct the appeal by way of rehearing. If, making proper allowance for the advantages of the trial judge, they conclude that an error has been shown, they are authorised, and obliged, to discharge their appellate duties in accordance with the statute.

[28] Over more than a century, this Court, and courts like it, have given instruction on how to resolve the dichotomy between the foregoing appellate obligations and appellate restraint. From time to time, by reference to considerations particular to each case, different emphasis appears in such reasons. However, the mere fact that a trial judge necessarily reached a conclusion favouring the witnesses of one party over those of another does not, and cannot, prevent the performance by a court of appeal of the functions imposed on it by statute. In particular cases incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony will demonstrate that the trial judge's conclusions are erroneous, even when they appear to be, or are stated to be, based on credibility findings.

[29] That this is so is demonstrated in several recent decisions of this Court. In some, quite rare, cases, although the facts fall short of being "incontrovertible", an appellate conclusion may be reached that the decision at trial is "glaringly improbable" or "contrary to compelling inferences" in the case. In such circumstances, the appellate court is not relieved of its statutory functions by the fact that the trial judge has, expressly or implicitly, reached a conclusion influenced by an opinion concerning the credibility of witnesses. In such a case, making all due allowances for the advantages available to the trial judge, the appellate court must "not shrink from giving effect to" its own conclusion. Finality in litigation is highly desirable. Litigation beyond a trial is costly and usually upsetting. But in every appeal by way of rehearing, a judgment of the appellate court is required both on the facts and the law. It is not forbidden (nor in the face of the statutory requirement could it be) by ritual incantation about witness credibility, nor by judicial reference to the desirability of finality in litigation or reminders of the general advantages of the trial over the appellate process.

(Citations omitted)

90 The required approach was summarised most recently in the joint judgment of Bell, Gageler, Nettle and Edelman JJ in Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; 372 ALR 383 at [55]:

A court of appeal is bound to conduct a "real review" of the evidence given at first instance and of the judge's reasons for judgment to determine whether the trial judge has erred in fact or law. Appellate restraint with respect to interference with a trial judge's findings unless they are "glaringly improbable" or "contrary to compelling inferences" is as to factual findings which are likely to have been affected by impressions about the credibility and reliability of witnesses formed by the trial judge as a result of seeing and hearing them give their evidence. It includes findings of secondary facts which are based on a combination of these impressions and other inferences from primary facts. Thereafter, "in general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge" …

(Citations omitted)

91 The judgment of the Full Court of this Court in Jadwan Pty Ltd v Rae & Partners (A Firm) [2020] FCAFC 62 at [402]-[415] also contains a comprehensive review of the authorities which we gratefully adopt.

The appellants’ submissions as to the application of these principles

92 The appellants accepted that any finding of fact by the Judge based to any substantial degree on his assessment of the credibility of a witness should stand unless it can be shown that his Honour failed to use, or palpably misused, his advantage or had acted on evidence which was inconsistent with facts incontrovertibly established by the evidence or which was glaringly improbable. They submitted, however, that in this case, the Judge had “expressly disavowed” reliance on witness demeanour as providing the basis for his findings in relation to Ms Norvill’s reliability and credibility as a witness. The consequence, so the appellants submitted, is that this Court is in as good a position as the Judge to decide on the proper inferences to be drawn from the evidence; that the Court is obliged to weigh the conflicting evidence afresh; and that the Court is obliged to draw its own inferences and conclusions. The appellants also submitted that, given the disavowance of reliance on witness demeanour which they attributed to the Judge, it was not necessary for them to show that his Honour’s conclusions on his assessment of Ms Norvill’s evidence were “glaringly improbable”.

93 In our view, the appellants’ submission that the Judge had specifically disavowed reliance on witness demeanour involves a significant over simplification of his Honour’s reasons and should not be accepted. When properly understood, it is apparent that the Judge did not eschew reliance on his observations and assessments of the witnesses as they gave their evidence. It is apparent, on the contrary, that they were matters to which he did have significant regard. We state our reasons for this conclusion in the section of reasons which follows.

94 The Judge commenced his assessment by noting that witness demeanour is one consideration which may assist a judge in resolving conflicts in evidence, at [307]. It is apparent that in doing so, his Honour was using the word “demeanour” with its conventional meaning in this context, that is, as encompassing the matters which can be observed while the witness gives evidence and which are not apparent, whether in whole or in part, from the written record. These include the appearance of the witness and the manner in which he or she gives evidence. It is these matters which give trial judges advantages not shared by appellate judges.

95 The Judge noted, however, that it is well accepted that there are limitations on the inferences which can be drawn from the appearance of witnesses and referred, in this respect, to passages in the reasons of Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ in Fox v Percy at [30]-[31] concerning research which has cast doubt on the ability of judges to tell truth from falsehood accurately on the basis of appearance, at [308]. The Judge then noted other factors which may assist in determining the credibility of a witness and the reliability of his or her evidence: consistency with any previous account given by the same witness of the events in question; the plausibility and apparent logic of the events described by the witness; and the consistency of the witnesses’ account with other objectively established events, at [309]. His Honour then said that consideration of these matters is often a surer guide to the reliability of the evidence given by a witness about disputed events, at [309].

96 Having made these general observations, the Judge said, at [310]:

This is a case where such considerations, as opposed to witness demeanour, provide the main key to the resolution of the conflicts in the evidence.

(Emphasis added)

97 The appellants submitted that, by his statement in [310], the Judge had “expressly disavowed reliance on witness demeanour as providing the basis for his findings in relation to Ms Norvill’s reliability and credibility as a witness”.

98 A number of matters belie the accuracy of this submission. Instead, the Judge was indicating only that he would have particular regard to the considerations which he had identified in [309].

99 First, the Judge’s statement in [310] was not directed to the assessment of Ms Norvill’s evidence only, but to the evidence of all the witnesses who gave evidence about the matters on which the appellants relied for the plea of justification.

100 Secondly, the Judge described the considerations other than witness demeanour as the “main key” to the resolution of the conflicts in the evidence, not as the “sole key”.

101 Thirdly, it is apparent that, in the reasons which followed, the Judge did not exclude from consideration altogether his observations of the demeanour of the witnesses and of the manner in which they gave their evidence. As the Judge’s assessment of the witnesses is relevant not only to the appellants’ present submissions, but also to other grounds, we set out passages in the reasons which are indicative of the Judge’s use of demeanour.

102 In relation to Mr Rush, the Judge said that “[n]othing in his demeanour” suggested that he was not giving an accurate and honest account of the relevant facts and circumstances; that Mr Rush “did not appear” to be giving long-winded answers (as the Judge found that he had on some topics) to avoid answering the questions; and that Mr Rush “presented” as a highly articulate and analytical person who was, “by his very nature” prone to giving such complex and wordy responses. The Judge also said that he viewed some of Mr Rush’s evidence about a conversation he had had with a Mr Trewhella shortly before 14 November 2017 as “less than impressive” but did not consider that his evidence about that one issue was such as to cast doubt on the reliability of his evidence as a whole.

103 In relation to Mr Armfield, the Judge said:

[320] Mr Armfield was an impressive witness. There was no issue about his credibility as a witness or the reliability of his evidence generally. Nationwide and Mr Moran did not suggest that any of his evidence should not be accepted. Despite his obviously close friendship with Mr Rush, I consider that he gave forthright, honest and reliable evidence about the facts and circumstances relevant to the allegations. Nationwide and Mr Moran did not submit otherwise.

(Emphasis added)

104 The Judge described Ms Buday as being, in some respects, “a unique, if not, rather unusual witness”, noting that she had, on more than one occasion, sung her answer to a question. His Honour assessed Ms Buday as “a difficult witness at times” who had occasionally been “needlessly disrespectful” to senior counsel for the appellants and “contemptuous” towards the appellants. Plainly, these were assessments based on the manner in which Ms Buday had given her evidence. The Judge took into account Ms Buday’s close friendship with Mr Rush but concluded that, despite these features, she had given “clear, direct and forceful answers to the questions … put to her in relation to the events and circumstances in question”. That assessment too turned at least in part on the Judge’s observations of Ms Buday as a witness. The Judge concluded:

[322] … I can see no reason why her evidence should not be accepted as being reliable. Nationwide and Mr Moran ultimately did not advance any submissions in relation to Ms Buday’s credibility as a witness, or put forward any reasons why any of her evidence should not be regarded as reliable. It certainly was not suggested that she was not telling the truth about her observations about the rehearsals and the interaction between Mr Rush and Ms Norvill.

105 The Judge described Ms Nevin as “an impressive witness”, saying that her “frankness and candour” on one issue on which she was challenged was to her credit, at [325]. The Judge concluded that Ms Nevin was “a frank, forthright and honest witness, and that her evidence was reliable”.

106 The Judge commenced his assessment of Ms Norvill’s evidence by reference to the difficulties which persons making allegations of sexual assault or sexual harassment often experience. He referred to the vulnerability of their position, the stress involved in giving evidence about such matters and the distress which being required to recall such matters can cause. His Honour noted that many of these considerations applied in Ms Norvill’s circumstances and said that he had taken them into account in assessing her evidence, at [328].