FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Cassimatis v Australian Securities and Investments Commission

[2020] FCAFC 52

ORDERS

First Appellant JULIE GLADYS CASSIMATIS Second Appellant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs of and incidental to the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GREENWOOD J:

1 This appeal is said, by the appellants, to present a unique opportunity to examine the content, scope and operation of s 180 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the “Act”) because it is said to be the only case in which the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”) has alleged that directors acted in contravention of only s 180 of the Act and of no other duty or obligation arising under Chapter 2D.1 of the Act.

2 The appellants, Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, are former directors of Storm Financial Pty Ltd (“Storm”). At the time of the contravention of s 180(1) by the appellants as found by the primary judge, Storm was engaged in the business of providing financial services in the form of financial product advice to investors for the purposes of Division 3 of Part 7.7 of Chapter 7 of the Act. It had an Australian Financial Services Licence (“AFSL”) for that purpose. It had many investor clients both retail and wholesale. Shortly before the intense period of the Global Financial Crisis in the second half of 2008, Storm was a highly profitable company with annual revenues of $77M and consolidated gross assets of $120M: primary judge (“PJ”) at [1].

3 In particular, Storm provided financial product advice characterised as “personal advice” to retail investors or retail clients (for the purposes of ss 776B and 944A of the Act) which had the effect of engaging the obligations required to be discharged by Storm under s 945A of the Act. That section of the Act addresses the topic of the requirement cast upon the financial advice provider to have “a reasonable basis for the advice given to the client”. The primary judge found that Storm had failed to discharge the obligations cast upon it by s 945A(1)(b) and s 945A(1)(c).

4 Section 945A(1), at the time of the contraventions, provided that a providing entity (Storm) must only provide financial advice to the client (a retail client) if three elements were satisfied. The first element required the providing entity to “determine” the “relevant personal circumstances” of the client in relation to giving the advice and to make “reasonable enquiries” in relation to those personal circumstances: s 945A(1)(a). The text of the second and third elements was in these terms:

945A Requirement to have a reasonable basis for the advice

(1) The providing entity must only provide the advice to the client if:

(a) …

(b) having regard to information obtained from the client in relation to those personal circumstances, the providing entity has given such consideration to, and conducted such investigation of, the subject matter of the advice as is reasonable in all of the circumstances; and

(c) the advice is appropriate to the client, having regard to that consideration and investigation.

Note: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see subsection 1311(1)).

5 The “relevant personal circumstances” of the client was defined to mean “such of the person’s objectives, financial situation and needs as would reasonably be considered to be relevant to the advice”: s 761A of the Act.

6 The contravention of s 180(1) of the Act by the appellants, as found by the primary judge, involved, put simply, the following findings and reasoning. I will return to aspects of these matters later in these reasons.

7 First, in providing financial advice to clients, the appellants were deeply, directly engaged in managing the provision of financial advice by Storm to clients. At [21], the primary judge described the degree of control over Storm exercised by Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, as directors, as “extraordinary”.

8 Second, in exercising this degree of control over Storm, the appellants required, and thus allowed, Storm to deploy, in the provision of financial advice to retail investors, the Storm financial model (otherwise called the “Storm model”). Although the elements, as found by the primary judge, of the Storm model are explained later in these reasons, it is sufficient for present purposes to note that it involved advising clients to adopt a debt strategy of “double gearing” by obtaining loans secured over the homes of investors and also obtaining a “marginal loan” so as to invest in weighted index funds; to establish a “cash reserve”; and to pay Storm’s fees. The Storm philosophy in providing financial advice, as articulated to prospective clients at education workshops, was that “clients should embrace debt rather than be scared of debt”: PJ at [54]. In particular, the appellants required, and thus allowed, the Storm model to be deployed in the provision of financial advice to a group of investors who were “particularly vulnerable financially”.

9 Third, in doing so, the appellants failed to exercise their powers of management, as directors, and failed to discharge their duties owed to Storm, as directors, in the management of the provision of financial advice by Storm, with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they were a director of Storm, in Storm’s circumstances, and if they occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within Storm, as the appellants.

10 The primary judge observed at [21] that Mr and Mrs Cassimatis used their powers as directors to create an environment in which, as they were aware, it was almost inevitable that the Storm model would be applied to people with a “high degree of financial vulnerability”. The investors falling within the class of “relevant investors” (PJ at [17]) for the purposes of the analysis of the contended contraventions were 11 individuals, each of whom exhibited the following characteristics (PJ at [18]):

(i) they were over 50 years old;

(ii) they were retired or approaching and planning for retirement;

(iii) they had little or limited income;

(iv) they had few assets, generally comprised of their home, limited superannuation, and limited savings; and

(v) they had little or no prospect of rebuilding their financial position in the event of suffering significant loss.

11 At [18], the primary judge found that although there were other investors who had these five characteristics, ASIC’s case had been proved only in relation to the relevant 11 investors.

12 At [21], the primary judge observes that these five characteristics illustrate a class of people who were, or were amongst, the most vulnerable of Storm’s clients. The primary judge also found that due to the extraordinary degree of control exercised over Storm by the appellants, as directors, they would “reasonably have been aware that the Storm model was applied to financially vulnerable clients including [the 11 relevant investors]”. At [22], the primary judge found that a reasonable director, with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, discharging those responsibilities in Storm’s circumstances, would have realised that the application of the Storm model to investors exhibiting the five characteristics of the 11 relevant investors, was likely to involve inappropriate advice, and a reasonable director (with the responsibilities of the appellants and in Storm’s circumstances) would have taken some alleviating precautions to prevent the giving of that advice. The primary judge also observed at [22] that his Honour had reached that conclusion with a “strong awareness” of a contextual understanding that “a director’s powers to act are, of the very nature of corporations, ones which often require risks to be taken”.

13 As to the 11 relevant investors exhibiting the five characteristics described at [10] of these reasons, a feature of particular significance in ASIC’s primary case was that a group of investors called the “Part E investors” and the “Schedule investors” exhibited the characteristic that they were “retired” or “approaching and planning for retirement”. That contention, in relation to each field of investors, was contested and, in the end result, the primary judge found that the appellants had contravened s 180(1) of the Act, and that Storm had contravened provisions of the Act, in respect of the following 11 investors who were retail investors and approaching (or at) retirement. They are:

(a) Mr Paul Dodson and Mrs Valerie Dodson;

(b) Mr Robin Herd and Mrs Cecily Herd;

(c) Mr Raymond Higgs and Mrs Lorna Higgs;

(d) Ms Carlyn Knight;

(e) Mr Peter Madden and Mrs Barbara Madden; and

(f) Mr Malcolm Walker and Mrs Janet Walker.

14 Fourth, in failing to discharge the obligations arising under s 180(1), the appellants caused or permitted Storm to contravene s 945A(1)(b) and s 945A(1)(c). The same conduct of the appellants caused or permitted Storm to contravene s 912A(1)(a) and s 912A(1)(c). Those two sections required Storm to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its licence were provided “efficiently, honestly and fairly” and that it complied with the financial services laws as defined.

15 The primary judge found that the contraventions of s 945A(1)(b) occurred because Storm did not give “such consideration” to the subject matter of the advice given to the vulnerable investors, and did not conduct “such investigation” of the subject matter of the advice, “as was reasonable in the circumstances”: PJ at [23]. The contraventions of s 945A(1)(c) were found to have occurred because Storm provided financial advice which was “not appropriate” to those vulnerable investors “having regard to the consideration and investigation of the subject matter of the advice that ought to have been undertaken”: PJ at [23]. I will return to the basis for these findings later in these reasons.

16 It should be noted that ASIC’s contention, in the primary proceeding (PJ at [33]), was that in causing financial advice to be given to the vulnerable investors in a manner which caused Storm to contravene s 945A(1)(b), s 945A(1)(c), s 912A(1)(a), s 912A(1)(c) and s 1041E(1) of the Act (although no convention of s 1041E(1) was established by ASIC), the appellants exposed Storm to a foreseeable risk of the following harm:

(i) being found guilty of an offence under s 1311 of the Corporations Act;

(ii) cancellation or suspension of Storm’s AFSL by action under s 915C(1)(a) of the Corporations Act;

(iii) a banning order by action under s 920A of the Corporations Act;

(iv) court orders under s 1101B(1)(a)(i) of the Corporations Act; and

(v) civil proceedings by the [vulnerable] investors.

17 Fifth, the contraventions of ss 945A(1)(b), 945A(1)(c), 912A(1)(a) and 912A(1)(c) exposed Storm to a risk of harm which was a foreseeable consequence of the failure to exercise their powers, and discharge their duties, with the degree of objective care and diligence required by s 180(1) of the Act. The foreseeable risk of harm to Storm arising out of Storm’s contraventions of those sections of the Act mentioned above was found to be twofold. First, the contraventions by Storm “would have (and did have) devastating consequences for many investors in that class [the vulnerable investors exhibiting the five characteristics]” and, second, the discovery of those breaches would have “threatened the continuation of Storm’s [ASFL] and Storm’s very existence”: PJ at [23].

18 The primary judge found that emblematic of the “devastating consequences” confronting each of the 11 vulnerable investors exhibiting the five characteristics described at [10] is the set of circumstances of Mr Paul Dodson and his wife, Mrs Valerie Dodson. The primary judge summarised those circumstances at [11] to [14] of his Honour’s reasons. However, having regard to the consequences, as found, for this group of 11 investors, it is useful to examine the emblematic circumstances of Mr and Mrs Dodson in just a little more detail as set out by the primary judge at [167] to [182] of his Honour’s reasons, as follows (in particular, noting the end position Mr and Mrs Dodson found themselves in as reflected at [182]):

167 When Mr and Mrs Dodson were advised by a Storm representative their circumstances were as follows. Mr Dodson was 60 years old. His wife was 55 years old. They had a combined total income before tax of $58,996 per annum which included a double orphan pension of $3,640 per annum. They were the guardians of a girl whose parents had died.

168 In 2003, Mr and Mrs Dodson sold the cake shop that they ran for 18 years. Mr Dodson started night shift work in a job doing security and traffic control. Mrs Dodson worked in aged care. They had saved superannuation, and had an investment with a Colonial managed fund, with a combined total of just over $300,000. After expenses plus 10%, they had $9,410 surplus funds each year. They owned their own home which was worth around $460,000. They had lived there for 27 years. Mr Dodson had a heart condition. They wanted to travel in retirement. Storm understood that he and his wife were “preparing for retirement in a few years”.

169 Mr and Mrs Dodson had limited investment experience. They had owned residential property and had units in the Colonial fund but they had never owned shares or investment property and had never had a margin loan.

170 In 2003, Mr and Mrs Dodson met the fund manager for the girl for whom they were guardians, Mr Fullerton-Smith. He had managed the girl’s funds following the death of her father. In the second half of 2007, Mr and Mrs Dodson discussed with Mr Fullerton-Smith the prospect of investing in the Storm model. Mr Fullerton-Smith became their Storm adviser.

171 Mr and Mrs Dodson attended the education workshop. After that, Mr Fullerton-Smith prepared a Confidential Financial Profile which Mr and Mrs Dodson signed. Their Confidential Financial Profile described their objectives as:

To live self-sufficiently and be happy until the day you die.

Travel in retirement.

172 Mrs Dodson also initialled the option on page 22 under the heading “Personal Profile” which said:

I am prepared to accept volatility if in the medium to long term the investment growth is higher and the risks over that term are minimal or eliminated.

173 In November 2007, Mr and Mrs Dodson received advice from Storm in an SOA. In internal communications on Phormula, Storm officers had considered advising Mr and Mrs Dodson to take an 80% mortgage over their home but had concluded that:

I am not sure if they will get an 80% lend so have assumed 60% against the home (this can be adjusted if need be) plus some margin lending for an investment of $315K.

174 Mr and Mrs Dodson were advised: (i) to borrow $276,000 from the Bank of Queensland to invest in indexed funds; (ii) to borrow $90,000 against that investment as a margin loan from Colonial Margin Lending, using their existing Colonial managed funds worth approximately $65,000 as security for their margin loan; and (iii) with the debt of $386,000 to obtain an investment of $315,000 in indexed funds, and reserves of approximately $21,000 in the Macquarie Investment Management Limited Cash Management Trust. The remainder, $26,960, was to be paid to Storm for its fees.

175 The investment by the Dodsons in indexed funds was ultimately as follows:

(1) $222,000 in the Storm Australian Industrials Indexed Trust;

(2) $105,000 in the Storm Australian Resources Indexed Trust; and

(3) $18,000 in the Storm Australian Technology Indexed Trust.

176 Mr and Mrs Dodson accepted Storm’s recommendation. They deposited $500 per month into the Macquarie Cash Management Account. All of the interest payments from the loans were paid out of the Macquarie Cash Management Account or the interest was capitalised.

177 On 18 April 2008, Mr and Mrs Dodson received an SOAA from Storm. The SOAA recommended that they borrow an additional $53,994 from their existing margin loan with Colonial Margin Lending and use the borrowed funds to:

(1) invest $2,000 in the Storm Australian Technology Indexed Trust;

(2) invest $36,000 in the Storm Australian Industrials Indexed Trust;

(3) invest $12,000 in the Storm Australian Resources Indexed Trust; and

(4) pay Storm’s fees of $3,994.

178 They accepted that recommendation and signed the documents provided by Storm.

179 On 5 September 2008, shortly before the full impact of the GFC, Mr and Mrs Dodson received another SOAA from Storm which recommended that they borrow an additional $10,000 from their existing Colonial Margin Loan and deposit the additional borrowed funds into their Macquarie Cash Management Trust Account to build cash reserves. They accepted Storm’s recommendation.

180 On 8 October 2008 and 21 October 2008, Storm wrote to Mr and Mrs Dodson in relation to what Storm described on 21 October 2008 as “what is proving to be unprecedented world events”, namely the GFC. Storm advised them [to] switch up to 100% of their portfolios out of shares and into cash. They accepted Storm’s recommendation.

181 In January 2009 Storm went into voluntary administration.

182 Prior to investing with Storm, Mr and Mrs Dodson owned their own home. They had a Colonial investment and superannuation totalling $300,000. They had no substantial debt. Mr and Mrs Dodson now have a home loan on their house of $287,000 (with an offset of $197,000), a line of credit drawn to $32,000, and no Colonial investment. Neither has been able to retire. Mr Dodson continues to work as a casual security officer and Mrs Dodson continues to work as an aged care worker.

19 The circumstances in which Mr Robin Herd and Mrs Cecily Herd found themselves should also be noted as described by the primary judge at [183] to [201] of the primary judge’s reasons. The circumstances are these.

Mr and Mrs Herd (Part E investors)

183 Mr and Mrs Herd were married for 54 years. Until they retired in 1992, Mr Herd was a school principal, and Mrs Herd was a teacher. For the decade after they retired, Mr and Mrs Herd relied solely on their superannuation funds and part pension as a source of income.

184 Immediately before investing with Storm, Mr and Mrs Herd had a combined income of approximately $39,000 which was their aged pension, investments and dividends. They were debt free. Mr and Mrs Herd had concerns about their declining financial base.

185 In August 2007, Mr and Mrs Herd invested with Storm. In their Confidential Financial Profile, Storm estimated their assets to be $689,879. They had no liabilities.

186 Mr and Mrs Herd had limited borrowing or investment experience prior to becoming clients of Storm. They had owned a residential and investment property (for which they had borrowed money), but had never owned shares or units in a managed fund and had never had a margin loan.

187 In mid-2006, Mr and Mrs Herd were contacted by Mr O’Brien, a Storm representative who invited them to attend a Storm workshop in the Redcliffe area. Mr Herd recalled that the presentation was about how investors could make money from borrowing funds against their assets. Mrs Herd remembered how the speakers had talked about “good debt and bad debt”, about “using money to make money” and that a good way of achieving success was to use the equity in the home to borrow funds. Mrs Herd also remembered being shown lots of facts, figures and graphs.

188 Between mid-2006 and November 2006, Mr and Mrs Herd attended at least two further meetings with Mr O’Brien. They provided him with information for their Confidential Financial Profile which described their objectives as:

To increase my retirement income.

189 They described their risk profile as:

I am prepared to accept volatility if in the medium to long term the investment growth is higher and the risks over that term are minimal or eliminated.

190 Mr and Mrs Herd accepted Storm’s SOA recommendations. They signed each of the documents provided by Storm. Storm recommended that Mr and Mrs Herd:

(1) borrow $222,000 from the ANZ Bank and $240,000 as margin loan from Macquarie;

(2) cash out $152,000 from existing allocated pension polices;

(3) use these funds to invest $525,000 in the Storm index funds and to pay Storm’s fees of $41,793; and

(4) use their home, valued at approximately $480,000, as security for the loan from the ANZ bank and the margin loan from Macquarie Margin Lending.

191 On 20 March 2007, Mr and Mrs Herd were given an SOAA which recommended that they (i) borrow an additional $53,719 from Macquarie, and (ii) use the borrowings to invest $50,000 in the Storm index/trust funds and to pay Storm’s fees of $3,719. They accepted the recommendations.

192 On 16 July 2007, Storm sent Mr and Mrs Herd a second SOAA making the same recommendations again to borrow an additional $53,719 from Macquarie, and to use the borrowings to invest $50,000 in the Storm index/trust funds and to pay Storm’s fees of $3,719. Again, they accepted the recommendations.

193 On 17 August 2007, Storm sent Mr and Mrs Herd a third SOAA which recommended that they (i) borrow an additional $74,009 from Macquarie; (ii) use $69,000 of the borrowings to invest into existing investment funds; and (iii) use the remainder to pay Storm’s fees of $5,009. Again, they accepted the recommendations.

194 On 20 October 2007, Storm sent Mr and Mrs Herd a fourth SOAA which recommended that they:

(1) redeem $20,000 of their investment in Storm index/trust funds;

(2) deposit the funds into their cash reserve; and

(3) replace the withdrawn funds by borrowing an additional $20,000 from their existing margin loan with Macquarie to invest in Storm index/trust funds.

195 In late 2007, Storm also recommended that Mr and Mrs Herd refinance their home loan from ANZ to NAB and increase the amount of their home loan from the $220,000 to $304,000. They accepted this recommendation.

196 On 29 July 2008, Storm advised Mr and Mrs Herd that their margin loan was in buffer at 81.66%. Storm recommended that they link $25,000 of the funds from their cash reserve to their margin loan. Mr and Mrs Herd accepted Storm’s recommendation.

197 On 8 October 2008, following the GFC, Storm recommended that Mr and Mrs Herd switch up to 100% of their portfolio out of equities and into cash, and obtain a refund of pre-paid interest. In a second letter on the same date, Storm recommended that Mr and Mrs Herd switch up to 50% out of equities and into cash. Mr and Mrs Herd did not speak to anyone from Storm about the letters. They accepted Storm’s recommendations by signing the letters. At no time did Mr Herd receive any advice about a margin call.

198 Mr and Mrs Herd had no specific recollection of closing out their investments in the Storm index funds. Initially they were unaware that most of their Storm index funds were redeemed to cash and deposited in their cash reserve account. In December 2009, they redeemed their remaining investments and deposited the funds in their bank account. They received less than $10,000 for the redemption. When they closed their margin loan account they were charged a break fee of approximately $10,000.

199 Mr and Mrs Herd were unable to meet repayment obligations on their home. They sold their home in around July 2009 for $483,000. The proceeds of the sale went to paying off their NAB home loan debt. The remaining proceeds were deposited in their bank account.

200 Before Mr and Mrs Herd invested with Storm, they had a comfortable life. Subsequently, they relied on the charity of their family, and had had to give away or sell their possessions at well below cost. They moved in to a house in Caboolture which they purchased with their remaining savings. They used their full age pension for day to day living expenses.

201 On 31 October 2014, Mr Herd died from a heart attack. He was 77 years old.

20 I will return to the relationship between the circumstances of the vulnerable investors in the context of the corporation’s circumstances and the responsibilities of the directors within the corporation, later in these reasons. It should be noted that the contravention of s 180(1) of the Act by the appellants, as found by the primary judge, occurred in circumstances where the company was solvent and in circumstances where Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, as directors, were the owners of all of the issued shares in the company: PJ at [2].

21 It is convenient at this point to set out the text of s 180 of the Act as it was at the time of the conduct in question. Section 180, as enacted as part of the Act in 2001 (although the particular text took this form in March 2000 for reasons relating to the legislative history of s 180) was, and remains, in these terms:

180 Care and diligence – civil obligation only

Care and diligence – directors and other officers

(1) A director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they:

(a) were a director or officer of a corporation in the corporation’s circumstances; and

(b) occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the corporation as, the director or officer.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 1317E).

Business judgment rule

(2) A director or other officer of a corporation who makes a business judgment is taken to meet the requirements of subsection (1), and their equivalent duties at common law and in equity, in respect of the judgment if they:

(a) make the judgment in good faith for a proper purpose; and

(b) do not have a material personal interest in the subject matter of the judgment; and

(c) inform themselves about the subject matter of the judgment to the extent they reasonably believe to be appropriate; and

(d) rationally believe that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation.

The director’s or officer’s belief that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation is a rational one unless the belief is one that no reasonable person in their position would hold.

Note: This subsection only operates in relation to duties under this section and their equivalent duties at common law or in equity (including the duty of care that arises under the common law principles governing liability for negligence) – it does not operate in relation to duties under any other provision of this Act or under any other laws.

(3) In this section:

business judgment means any decision to take or not to take action in respect of a matter relevant to the business operations of the corporation.

22 I will return to aspects of s 180 later in these reasons, however, for present purposes, these things should be noted.

23 First, the question of whether the appellants engaged in conduct in contravention of s 180 begins and ends with the text of the section as the embodiment of the objective standard of the degree of care and diligence required of directors in the exercise of their powers and the discharge of their duties (taking due account, in construing the text, of the history leading to the adoption of the text), as applied to the facts as found.

24 Second, the inquiry as to whether a director has failed to meet the objective standard required by s 180(1) is a fact-intensive analysis, of the kind undertaken by the primary judge in this case.

25 Third, s 180(1) is engaged when a director (or other officer) “exercises a power” or “discharges a duty” and accordingly it is important to identify the power or the duty being exercised or discharged and the source of the power or duty. Once engaged, the section mandates an objective standard of care and diligence in the exercise of that power or the discharge of that duty. As to the engaged scope of the section, the scope of the definition of the term “officer” in s 9 of the Act should be noted: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v King [2020] HCA 4, 11 March 2020, Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ at [34]; Nettle and Gordon JJ at [185] and [186].

26 Fourth, with great respect to the primary judge, it seems to me that the circumstance that the appellants eschewed any reliance on the business judgment rule in s 180(2) as part of their defence does not mean that s 180(2) is to be disregarded in construing the text of the section, in context, to determine whether s 180(2) has any contextual bearing upon the construction of the integers of s 180(1).

27 Fifth, and critically, s 180(1) is normative and its burden is a matter of public concern not just private rights. It is an expression of the Parliament’s intention to establish an objective normative standard of the degree of care and diligence directors must attain or discharge in exercising a power conferred on them or in discharging a duty to be discharged by them. The objective standard is to be measured by the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they were a director of the corporation “in the corporation’s circumstances” and occupying the particular office held by the director (which, for example, might be as an executive director or as a non-executive director of the corporation), and having the same “responsibilities within the corporation” as the director whose conduct is impugned. Those “responsibilities”, contemplated by s 180(1), are not just statutory responsibilities imposed upon the director by the Act but include “whatever responsibilities” [original emphasis] the director has “within the corporation, regardless of how or why those responsibilities came to be imposed on that [director]”: Shafron v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2012) 247 CLR 465, French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ at [18]. The primary source of the powers to be exercised by directors and the duties to be discharged by them are to be found in the Memorandum and Articles of Association for the company (the “Constitution”), the Act, any responsibilities of the director within the corporation and the scope, according to the jurisprudence, of the powers and duties of governance to be exercised by the directors. To the extent that any other legislation casts, or purports to cast, statutory obligations on a person holding the office of a director or officer of a corporation, a question will arise of characterisation of the statutory instruments to determine the content and scope of the obligation and the relationship between those obligations so arising and s 180(1). That question does not arise in this case.

28 Sixth, the normative character of the obligation can be seen by recognising that, although it is commonly said that the statutory formulation of the degree of care and diligence required of directors by s 180(1) reflects the degree of care and diligence now required by both the body of law we call equity and the common law, the remedial and regulatory consequences of rendering the obligation a normative standard of Australia’s statutory corporations law is significantly different. A contravention of s 180(1), as a civil penalty provision, requires the Court to make a declaration of contravention: s 1317E(1); the elements of the declaration are set out at s 1317E(2); a pecuniary penalty may be imposed of up to $200,000 taking into account the statutory factors: s 1317G; a compensation order may be made requiring the director to compensate the corporation for damage suffered resulting from the contravention: s 1317H; and, on application by ASIC, the Court may disqualify the director from managing a corporation for a period the Court determines to be appropriate: s 206C(1).

29 Seventh, as to the relationship between the objective standard of care and diligence required of directors by s 180(1) and the duty of care and diligence of directors at common law and in equity, s 180(2) provides that a director who makes a business judgment (in conformity with the integers of the subsection) is taken to meet the requirements of s 180(1) “and their equivalent duties at common law and in equity”. The section seems to treat the objective standard required by s 180(1) as equivalent to the duties at common law and in equity.

30 Eighth, notwithstanding the normative character of s 180(1), the section does not operate to exclude duties arising at common law and in equity (whether equivalent to the objective standard of s 180(1) or otherwise). Section 185 of the Act provides that s 180 (and also ss 181 to 184) have effect in addition to, and not in derogation of, any rule of law relating to the duty or liability of a person because of their office (or employment) in relation to a corporation and the section does not prevent civil proceedings being commenced for breach of such a duty or liability. It seems clear enough that subsections 180(2) and (3) were intended to operate as something akin to safe harbour provisions making clear that a director would not find himself or herself in contravention of s 180(1) or equivalent obligations at common law and in equity if the integers of those subsections were satisfied. Thus, the savings provision in s 185 does not apply to s 180(2) and s 180(3). In any event, s 180(2) and s 180(3) seem to be “of little, if any, practical utility” (The Changing Position and Duties of Company Directors, Nettle J, Melbourne University Law Review (2018), Vol 41, 1402 at 1417) having regard to the observations of Austin J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich (2009) 236 FLR 1 at [7269] to [7278]. That approach was followed in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (2011) 190 FCR 364, 427 at [197] and [198] (“ASIC v Fortescue”), Keane CJ, Emmett J and Finkelstein J agreeing; see also ss 1317S and 1318 of the Act. This probably explains why the appellants abandoned any reliance upon s 180(2) in the primary proceedings. In ASIC v Fortescue at [199], Keane CJ made this observation about the relationship between s 180(1) and s 180(2) in the context of that particular case:

A separate but related answer to Forrest’s attempt to rely upon the business judgment rule is that s 180(2) cannot be construed as affording a ground of exculpation for a breach of s 180(1) where the director’s want of diligence results in a contravention of another provision of the Act and where that other provision contains specific exculpatory provisions enacted for the benefit of the director.

31 Ninth, as to the source of the power being exercised, the appellants were exercising powers as directors in the management and governance of Storm. As a matter of general principle, the business of the company is to be managed by or under the direction of the directors and the directors may exercise all of the powers of the company except any powers that the Act or the company’s Constitution (if any) require the company to exercise in general meeting: see also s 198A of the Act. Finally, as to the utility of shorthand phrases such as “stepping stones” to liability on the part of the director, I make observations about that matter at [79] of these reasons.

Some aspects of the findings of the primary judge

32 It is now necessary to return to some of the findings of the primary judge critical to the finding of a contravention of s 180(1) by the appellants.

33 As to the “Storm model”, these aspects of the financial model and the processes surrounding it should be noted. The process adopted by Storm when advising clients had a number of stages which rarely took fewer than three months to complete: PJ at [45] and [46]. The stages of the process included:

(1) a preliminary appointment or “primer” meeting;

(2) an education workshop;

(3) a Confidential Financial Profile meeting and preparation of cash flow;

(4) a review or reviews of the recommended cash flow with the prospective client and subsequent steps including the preparation of the SOA [Statement of Affairs];

(5) a presentation of the SOA;

(6) the signing by the client of the loan documents and investment documentation, and the investment processing;

(7) further investment “steps”; and

(8) no exit plan.

34 At the education workshops, which were generally presented by Mr Cassimatis or employees chosen by him (PJ at [48]), prospective clients were told that the fundamental investment method recommended by Storm was to build wealth by using home loans and margin loans to borrow funds to invest in index funds: PJ at [51]. For almost 90% of the clients of Storm, Storm’s advice was to obtain a loan secured over the client’s house, as well as a margin loan, and to use the funds from these loans to invest in “index funds” based on the “ASX300”: PJ at [82]. The ASX300 is a market capitalisation weighted index made up of the 300 largest companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).

35 Storm also encouraged further investments to be made based on movements in the share market. The recommended investment advice was that if the market fell by 10% or more from the date of the initial investment, a further investment should be made using the client’s cash reserves so as to lower the average cost of the total investment. If the share market rose in value by 10% or more from the date of the initial investment, a further investment should be made by increasing the margin loan so that the ratio of the loan to the value of the client’s investment (the “LVR”) was returned to the ratio prevailing at the time of the initial investment: PJ at [51(4)].

36 At the Confidential Financial Profile meeting, prospective clients were asked to read and identify and initial a statement of the degree of volatility and risk they were prepared to accept in making investments. There were four categories of risk identified by Storm: PJ at [61]. Category 3 was: “I am prepared to accept volatility if in the medium to long term the investment growth is higher and the risks over that term are minimal or eliminated” [original emphasis]: PJ at [61]. Storm’s adviser was trained to say that Storm is “going to recommend that you invest in a volatile asset, but a safe volatile asset, and that’s why we invest in ‘supershares’” and “that’s what this third statement is all about”: PJ at [62]. The investors were also told that “[w]e’re asking you to take on the risk of a volatile asset but a safe volatile asset”: PJ at [62]. However, the “safety” of that “volatile asset”, that is, the investment in the ASX300 index fund, resided, according to Risk Category 3, in the capacity or willingness of the client to weather volatility over the “medium to long term” so that the risks inherent in volatility might be minimal or eliminated over that term.

37 Once the Confidential Financial Profile was completed and verified by the client, the Storm “data entry team” or “input cell” would enter information from the client into a cash flow spreadsheet. By late 2007, Storm had developed a database called “Phormula” and client information was then entered into that database. Initially, only the appellants had authority to prepare a cash flow. By 2006, the “cash flow committee” or “compliance cell” began to prepare cash flows, although preparation of cash flows remained “tightly controlled”: PJ at [67] and [68].

38 The cash flow was prepared in an Excel spreadsheet which included all of the client’s income and expenditure. Formulas in the spreadsheet modelled a suggested investment plan. Every plan was done over a 17 year period irrespective of the age of the client: PJ at [68].

39 Although the cash flow involved many standardised formulas, different approaches were taken for different classes of client. If a client was not retired, an overall debt ratio of 60% or less (with a home loan of 80%) would be used, and capital growth was not generally the sole source of funding for the recommended borrowings. However, for a client who was retired or nearing retirement age, the overall debt ratio was 50% or less (assuming a home loan of 60%): PJ at [69].

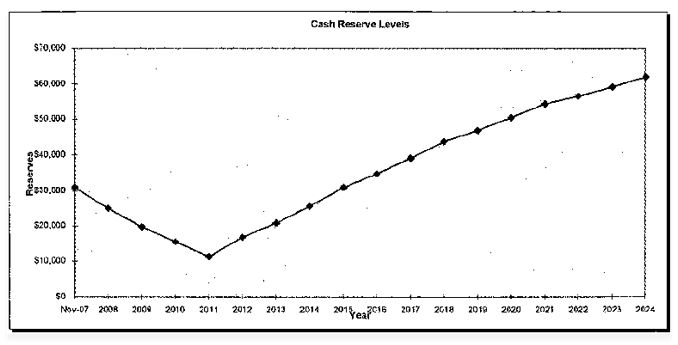

40 A critical component of the cash flow statement was a provision for a client’s “cash reserves”, otherwise called, a “cash dam”, held in a Cash Management Trust. The cash flow statement showed reserves of cash over a 17 year period having regard to the client’s revenue and expenses flowing from the investment recommendations; the client’s contributions and distributions; and an assumed rate of return: PJ at [70]. The primary judge observes that Storm’s practice was to leave a minimum of 12 months of interest servicing in the client’s cash reserves: PJ at [70]. A cash flow would not be approved if the client’s cash reserves were not predicted, by the cash flow statement, to increase over time.

41 However, the primary judge notes at [71] that if the cash reserve was not shown as “growing” (assuming no growth in the value of the investment itself), “the parameters were changed to allow growth in the investment, such as after a period of between two and five years for retirees”: PJ at [71]. However, these adjusted cash flows “did not factor in any period of negative growth (ie any decline in the value of the index funds)”: PJ at [71].

42 The significance of this approach to preparing a cash flow and establishing “cash reserves” for a client was put this way by the primary judge at [72]:

It will be apparent from this discussion that, as Mr McMaster explained [the expert accepted by the primary judge], the “cash flow” was not really a cash flow and that “cash reserves” were not actually cash reserves. The formulas calculated “cash reserves” as a combination of cash and growth in the index funds. The index funds were relatively liquid so that clients could generally sell them when they wanted (at least prior to the GFC) but they were not actually cash. Not only did the spreadsheet treat the growth in index funds together with cash, but it also assumed that the growth would not be liquidated because it was assumed that there would be dividends and further growth; the cash rate would only be applied to the actual cash balance of the cash reserves unless cash reserves became “negative” (because the cash had all been used and the growth had been liquidated).

[original emphasis in italics, emphasis in bold added]

43 For many clients, three cash flows would be prepared. The “recommended cash flow” was called the “viability cash flow”, which reflected the considerations described at [34] to [41] of these reasons. It formed the basis for the SOA to the client. It showed the lowest investment returns of the three cash flows. Mr Cassimatis described it as a plan that could survive under adverse conditions, but that other cash flows were more realistic: PJ at [74]. Once the prospective client was satisfied with the viability cash flow (after presentation of it to the client in a one-on-one meeting with the adviser over a period of two to four hours), a sequence of steps would then be implemented to give effect to the elements reflected in the viability cash flow leading to the final version of the delivered SOA. Consistently with the Storm model, Storm would send Statements of Additional Advice (SOAAs) to advisers for its investor clients or sometimes directly to investors to make additional “step investments” if the market fell or rose by 10% or the client’s circumstances changed: PJ at [10]. For example, Mr and Mrs Herd were given four SOAAs between 20 March 2007 and 20 October 2007. In the case of Mr and Mrs Higgs, they received seven SOAAs between 29 November 2006 and 22 January 2008.

44 In the result, as mentioned at [34] of these reasons, for almost 90% of the clients, Storm’s advice was to obtain a loan secured on the client’s home and a margin loan as well and use the funds from these loans to invest in index funds based on the ASX300. As to the remaining 10% of the clients, the primary judge observes that they were generally young people who did not have an asset base such as a family home and Storm’s advice to them was to obtain a margin loan or a personal loan to invest in indexed share funds: PJ at [82].

45 Ultimately, the primary judge found that a reasonable director with the appellants’ responsibilities, and in Storm’s circumstances, would have realised that the application of Storm’s investment model to the 11 vulnerable investors, exhibiting the five characteristics earlier described, was “likely to involve inappropriate advice” such that a reasonable director with those responsibilities and in Storm’s circumstances, would have taken alleviating precautions to prevent the giving of that advice to those vulnerable investors in order to satisfy the degree of care and diligence required by s 180(1).

46 The primary judge found that there were four essential reasons why Storm acted unreasonably within the terms of s 945A(1)(b) of the Act. The primary judge observes that the conclusions relating to those four reasons were reached in the context of the circumstances concerning Mr and Mrs Dodson, although the conclusions applied equally to the other nine relevant investors: PJ at [250]. The four reasons were these.

47 First, Storm did not give reasonable consideration to, or conduct reasonable investigation of, alternative investment strategies for those investors who were retired or who were approaching retirement: PJ at [251].

48 Second, Storm did not adequately determine the objective of its advice given to these investors, which required measurement and, where possible, quantification: PJ at [261].

49 Third, Storm did not conduct an adequate “sensitivity analysis” before advising the investors: PJ at [274]. The primary judge accepted the expert evidence of Mr McMaster that many financial planners conduct sensitivity analyses (although the practice was not universal) and that a proper sensitivity analysis exhibited these features:

Sensitivity analysis is designed to see how the client is affected if different outcomes occurred – good outcomes as well as poor outcomes – and it’s designed to show the change in equity that would occur in the event that these various outcomes came to pass, and it can be put in front of a client and shown to them,

“Look, the average return of this type of investment over the last 10 years has been X and if we had that average investment return over the [next] year, this is the outcome you would expect.

If, on the other hand, we had a negative return of the same amount, this is the outcome you would expect. If, on the other hand, we had, you know, a significant downturn, this is the outcome you could expect and if we had a significant upturn, this is the outcome you could expect,”

and by doing that, the client very clearly understands the type of risk they’re taking if any of these outcomes occur.

50 Fourth, and closely related to proposition three, Storm did not give reasonable consideration to the income of the investors “in all their circumstances”: PJ at [285]. The primary judge at [286] found that one important respect in which Storm’s consideration of the income of the investors was not reasonable, was that it did not conduct an analysis of the client’s actual cash flow, independently of the proposed investment, to determine whether the client had capacity to fund the costs associated with the borrowings and any margin calls to the extent not covered by income from the investments: PJ at [286].

51 Having considered those matters, the primary judge considered that the advice was not suitable for the relevant investors for the following three reasons.

52 First, Storm inappropriately classified the relevant investors as “Balanced investors” and advised them as such when in truth, they exhibited the characteristics of a “Conservative investor” as each of those terms are explained in the primary judge’s reasons.

53 Second, Storm included the family home of the investors in their asset portfolio for investment purposes. The primary judge notes that the evidence of the experts (about which there was agreement), and which the primary judge accepted, was that generally, the closer a person gets to retirement, the less attractive it will be to borrow against the family home: PJ at [325]. The primary judge observed that the qualification “generally” had been added by Professor Valentine because there are some investors who have the wealth or income to be able to manage a borrowing secured against the family home. However, the primary judge observed that in the case of the relevant investors, all of them “had limited wealth and limited income”: PJ at [325].

54 Third (and the primary judge observes of this consideration that it operated independently of the other two matters), in all the circumstances the advice to the relevant investors to utilise the Storm model was “generally inappropriate”.

55 As to the first of those reasons, the primary judge identifies four further reasons why an adviser could not reasonably have reached the conclusion that the relevant investors were “Balanced investors” rather than “Conservative investors”.

56 As to the second reason, the primary judge observed that without an analysis of the risk of the investment portfolio, independently of the risk to the family home, it would be inappropriate to advise the client to use the family home as part of an investment portfolio: PJ at [327].

57 As to the third reason, the primary judge concluded that the advice was inappropriate because the circumstances of the relevant investors meant that a double-geared investment which was concentrated in the share market was not appropriate for them as it involved high risk. The primary judge accepted the ultimate conclusion reached by Mr McMaster (an expert accepted by the primary judge) that the reason why the investors “suffered so badly” during the GFC was: “the concentration of investment assets in share market investments; the high level of debt relative to investment assets; and the absence of financial capacity to maintain their position during a downturn in markets”: PJ at [329]. At [330], [331] and [332], the primary judge said this:

330 To these reasons must be added the possibility of a significant market fall. The extent of the GFC was not a matter which Storm could reasonably have foreseen at the time of the advice given in the SOAs to investors, although the experts agreed that a fall of up to 10% could have been predicted. Nevertheless, even without the benefit of hindsight, the three matters to which Mr McMaster referred left the investors exposed to significant downturns in the market. A significant downturn, potentially exceeding 10% by a considerable margin, such as 22%, was a possibility [as to which the primary judge had expressed observations at [281]].

331 The experts agreed in their report that “a financial planner should generally not advise a retired person or a person nearing retirement to invest in high risk investments”. They also agreed that generally negative gearing is “high risk within a period of approximately 5 years to retirement”.

332 This point applies to all the relevant investors. …

The degree of control over Storm exercised by Mr and Mrs Cassimatis

58 A further factual matter that needs to be noted which is central to the primary judge’s finding of a contravention by the appellants of s 180(1) is the extent to which the appellants exercised control over Storm.

59 The primary judge observed that the notion that the appellants were responsible for Storm’s operations “at a high level” was not contested, although in order to determine whether their conduct gave rise to a contravention of s 180(1), it remained necessary to examine the extent of their control and the degree to which their control permeated through Storm from the highest levels of executive management to even mundane day to day activities.

60 The primary judge was satisfied that the evidence established that the appellants “had knowledge of and an extraordinary degree of control over every aspect of the Storm model and Storm’s operations including the day to day business of Storm even after the company had acquired more than 2,000 clients”: PJ at [113]. The primary judge also found that the control asserted over Storm by the appellants “was extensive to the point that it substantially stifled much possibility of dissent or contradiction, as they would have been aware”: PJ at [113]. The primary judge then identified eight separate matters going to the extent of the control exercised by the appellants.

61 Those eight matters were these.

62 First, Mr and Mrs Cassimatis controlled the Executive Committee and the Board of Storm. Mrs Cassimatis approved all draft agendas, Board papers and minutes. Mr Cassimatis chaired Board meetings. The primary judge accepted evidence that the independent, non-executive directors of Storm were “passive” at Board meetings.

63 Second, even apart from management level decisions, the appellants asserted “a high level of control over all aspects of Storm’s finances from the most serious to the most mundane”. Mr and Mrs Cassimatis gave instructions that no-one was allowed into the accounting team’s room in the head office without their authority and although Mr Barrett was the Chief Financial Officer, he could not make any payment, no matter how small, without the approval of Mrs Cassimatis when she was available: PJ at [120].

64 Third, the appellants had considerable control over the financial advisers and the process for giving advice concerning the Storm model. The primary judge accepted evidence that the appellants took the position that Storm advisers made no decisions. Rather, Storm’s “specialists” or “financial engineers” would formulate the content of and prepare all advice to clients and the appellants insisted upon approving any advice to a client which did not meet Storm’s mandated investment parameters: PJ at [121].

65 Fourth, the appellants asserted significant control over the education workshops. All changes to slides had to be approved by the appellants: PJ at [124].

66 Fifth, the appellants asserted significant control over the preparation of the cash flows and Mr Cassimatis was the main designer of the spreadsheet and formulae used in those spreadsheets. The primary judge accepted evidence that the appellants set the parameters used in the preparation of cash flows and, for a number of years, nobody other than Mr Cassimatis tested the cash flow modelling. Moreover, even when some control over the cash flows was relinquished and authority delegated to particular individuals, “Mr and Mrs Cassimatis still approved the cash flows”: PJ at [125].

67 Sixth, Mr Cassimatis led the presentations to external parties often in the presence of Mrs Cassimatis. Mrs Cassimatis would contribute to the presentations. The presentations involved education seminars, update meetings, meetings where the content of proposed advice was presented by Mr Cassimatis to the client, presentations of the Storm model to high profile prospective clients and other meetings: PJ at [129].

68 Seventh, the process of giving advice in an SOA was “tightly controlled by Mr and Mrs Cassimatis”. The primary judge accepted evidence that every Authorised Representative of Storm was primarily trained by Mr Cassimatis, with Mrs Cassimatis also providing some training in relation to compliance issues: PJ at [131]. The primary judge observed that the SOAs were prepared centrally based on a template and that Mrs Cassimatis was responsible for the changes to the SOA template. Until about 2006, Mr Cassimatis or Mrs Cassimatis “approved every SOA”. Although some authority was delegated, advisers were not permitted to create or amend an SOA: PJ at [132]. The primary judge accepted evidence that Mr and Mrs Cassimatis frequently said words to the effect that the giving of any advice to Storm clients that was inconsistent with the Storm system of advice would not be countenanced: PJ at [133].

69 Eighth, the appellants developed Storm’s relationship with external bodies.

70 At [136], the primary judge makes this observation:

Despite the extraordinary control that Mr and Mrs Cassimatis had over Storm, and despite the lack of dissent about which they were aware, to a limited extent they did encourage some approachability and transparency, and on some occasions they raised the possibility that others might take responsibility for “some” issues. As I have explained, these broad statements did not have much effect. …

The relationship between the contended contraventions of s 180(1) by the appellants and contraventions by Storm of other provisions of the Act

71 An essential aspect of the finding by the primary judge of failure on the part of the appellants to discharge the degree of care and diligence required by s 180(1), is the finding that the appellants ought to have been reasonably aware that the application of the Storm model to the 11 vulnerable investors involved Storm not giving such consideration to the subject matter of the advice to those clients, as was reasonable in all the circumstances, and not conducting such investigation of the subject matter of the advice, as was reasonable in all the circumstances. Those failures of due care and diligence on their part resulted in a finding of a contravention by the appellants of s 180(1).

72 Moreover, the failure of the appellants to discharge an obligation of due care and diligence as required of them by s 180(1) also finds expression in this way. A reasonable director, with the responsibilities of the appellants, and in Storm’s circumstances, would not have provided advice to the 11 vulnerable investors that was not appropriate to them having regard to the consideration and investigation of the subject matter of the advice that ought to have been undertaken.

73 Although the matters at [71] and [72] have the effect of giving rise to contraventions by Storm of s 945A(1)(b) and s 945A(1)(c) respectively (and in both cases contraventions by Storm of s 912A(1)(a) and s 912A(1)(c) respectively), they are matters that arise for Storm because the appellants, as directors, failed, in terms of the descriptive content of their conduct at [71] and [72], to exercise the degree of due care and diligence required of them by s 180(1) having regard to their position as directors, the degree of control they exercised over Storm and the features of the Storm model they applied to the relevant investors.

74 The conduct at [71] and [72] is the expression of failures on the part of the appellants as directors, in contravention of s 180(1), which had the effect of giving rise to contraventions by Storm. The finding that the appellants should have been reasonably aware that Storm did not give reasonable consideration, in all the circumstances, to the subject matter of the advice given to the vulnerable investors, and that Storm did not conduct an investigation of the subject matter of the advice that was reasonable, in all the circumstances, is the content of their failure to discharge the obligations arising under s 180(1). These failures are primary direct failures on the part of the appellants to discharge the obligation cast upon them by s 180(1) measured by the objective standard of that section as earlier described.

75 Thus, it is critical to keep firmly in mind that although, in the primary proceeding, ASIC contended for contraventions of ss 945A(1)(b), 945A(1)(c), 912A(1)(a) and 912A(1)(c) by Storm (and made good those contentions, leaving aside the contention, which was unsuccessful, of a contravention by Storm of s 1041E(1)), it did not contend that the appellants contravened s 180(1) of the Act because Storm contravened those sections of the Act. That would be to invert the true position. ASIC contended for conduct, on the part of the appellants, that bore the characteristics of the failures described at [71] and [72], as found by the primary judge as already described, and those failures engaged a contravention by them of their obligations under s 180(1) to exercise their powers of management and discharge their duties of management with the degree of care and diligence required of them by the subsection.

76 Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, by their conduct, as described, in contravention of s 180(1), caused Storm to contravene those sections.

77 The finding of contraventions of those sections of the Act by Storm, and the need for ASIC to make good those contended contraventions, was critical to the case under s 180(1) against the appellants not because the contraventions by Storm of those sections of the Act would give rise to a contravention by the directors of s 180(1) in the form of some sort of dystopian accessorial liability, but rather because the contraventions by Storm, deriving from the conduct of the appellants themselves, as described, contained within it a foreseeable risk of serious harm to Storm’s interests (that is, a potential loss of its AFSL; a threat to Storm’s very existence; and suit by the vulnerable investors to address the consequences of the advice given to them and thus the contraventions by Storm), which reasonable directors, with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, standing in Storm’s circumstances, ought to have guarded against.

78 In failing to guard against that foreseeable harm flowing from contraventions by Storm, the directors failed to discharge the degree of care and diligence required of them by s 180(1).

79 The contraventions of the particular sections of the Act by Storm were, of course, material to the foreseeable risk of serious harm to Storm which the appellants, as a matter of primary obligation on their part, were required to guard against, in the exercise of their powers of management and the discharge of their duties of management, by exercising the required statutory degree of objective care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise in their position, in the corporation’s circumstances and having the same responsibilities within the corporation as the appellants, particularly having regard to the degree of control the appellants exercised over Storm in the way described at [58] to [70] of these reasons. Had ASIC not been able to establish conduct that engaged contraventions of the sections of the Act by Storm as found, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to sustain the contention that the appellants engaged in a contravention of s 180(1) by failing to guard against a foreseeable risk of serious harm to Storm which was said to have arisen out of such contraventions. Importantly in this context, shorthand phrases such as stepping stones to liability on the part of a director or officer are unhelpful and apt to throw sand in the eyes of the analysis. The appellants were not found to have contravened s 180 of the Act because the corporation contravened the Act. The contraventions of the Act by Storm were a necessary element of the harm, but not sufficient by themselves to result in a contravention of s 180 by the appellants as directors. The foundation of the liability of the appellants resides entirely in their own conduct in contravention of the objective degree of care and diligence required of them by the statutory standard contained within s 180 of the Act.

Some observations of the primary judge in relation to s 180(1) of the Act

80 It is necessary to note some observations of the primary judge about s 180(1) of the Act.

81 The first thing to note is that at [469], the primary judge accepted that there is a large body of authority which has treated s 180(1) as a duty which is owed only to the company, even when it is enforced by ASIC or when public sanctions are sought.

82 The primary judge accepted the appellants’ contention that the principal proceeding was concerned only with the due care and diligence obligation in relation to the discharge of their duty to manage Storm. The primary judge found that although the discharge of the duty to manage Storm gave rise to a duty to “consider Storm’s interests” [original emphasis], that duty did not “require a narrow construction of Storm’s interests which is limited only to the interests of its shareholders”: PJ at [478]. The primary judge proceeded on the basis that the “public duties” of the appellants as directors in managing Storm, “would only be contravened if they acted contrary to Storm’s interests rather than contrary to any general norm of conduct” [original emphasis] and the notion of “Storm’s interests” should not be construed narrowly: PJ at [478]. That being so, the primary judge identified three “important aspects” of the “dominant test” for the “content of the duty” arising under s 180(1).

83 First, the reference to reasonably foreseeable harm to the corporation at the time of the contended failure to exercise care and diligence (deriving from Ipp J’s formulation in Vrisakis v Australian Securities Commission (1993) 9 WAR 395 at 449-450 (“Vrisakis”), in the context of contended contraventions of s 229(2) of the Companies (Western Australia) Code 1961 (WA), is “best understood” as a reference to harm to any of the interests of the corporation and thus all of the corporation’s interests are relevant when undertaking the process of “balancing” the foreseeable risk of harm against the potential benefits that could reasonably have been expected to accrue to the company from the impugned conduct: PJ at [480].

84 The primary judge observes that one reason that the concept of harm ought not to be construed narrowly is that the “overarching question” raised by s 180(1) is one of “due care and diligence” in the exercise of powers, and the broad terms of the objective statutory standard do not confine the interests of the corporation which fall for consideration in complying with that standard: PJ at [481].

85 The primary judge considered that no proof of actual loss to the corporation is required by s 180(1) and harm to its interests including “reputation” might also accrue without prospective loss: PJ at [481]. The primary judge observes that harm includes “non-pecuniary consequences” for a corporation: PJ at [482].

86 Moreover, the corporation has “a real and substantial interest in the lawful or legitimate conduct of its activity independently of whether the contended illegality of the conduct will be detected or cause loss” [original emphasis]: PJ at [482]. One reason for “that interest” is the corporation’s reputation and its existence as a vehicle for “lawful activity”: PJ at [482]. At [484], the primary judge says this:

484 Although these non-financial concerns about legality of conduct are relevant considerations, in this case the potential consequences of the alleged failures to comply with the law were also serious financial threats to Storm including a potential threat to its very existence by the loss of its AFSL.

87 Second, the reference to “balancing” in the assessment of due care and skill in Vrisakis is not practically susceptible of any quantitative estimate. The task involves a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action. It is a forward-looking exercise to try and understand what a reasonable person would have done, not a backward-looking exercise to steps which would have avoided the relevant harm: PJ at [485] to [487].

88 Third, the scope of the duty arising under s 180(1) is to be determined “in the terms of that section”, with the result that the consideration of the foreseeable risk of harm, together with the potential benefits that could reasonably have been expected to accrue to the company from the conduct in question, must take place from the perspective of the corporation’s circumstances and the office and the responsibilities of the director: PJ at [488] and [495]. The primary judge observed that this notion has significance in this case “because of the vast responsibilities assumed by Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, and the strength of control that they asserted over Storm” [emphasis added]: as to which see [58] to [70] of these reasons.

89 At [680], the primary judge, having explained and having made findings concerning the conduct that gave rise to contraventions of s 945A(1)(b) and s 945A(1)(c), finds that “[t]hese breaches were not merely reasonably foreseeable”, rather, “[a]t the time of the breaches, a reasonable director with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis should have regarded them as likely” [original emphasis].

90 At [681], the primary judge makes this observation:

681 … In particular, having regard to their responsibilities and Storm’s circumstances there was a strong likelihood of one or more breaches such as (i) a lack of reasonable consideration of alternative investment strategies; (ii) inadequately determining the objective of advice given; (iii) inadequate sensitivity analyses being performed; and (iv) a failure to consider a client’s cash flow independently of proposed income to determine the client’s ability to fund interest payments or margin calls.

[emphasis added]

91 Thus, it can be seen, that the primary judge regarded the matter of the breaches as not just “likely” but a “strong likelihood”.

92 Several factors contributed to the primary judge’s finding that a reasonable director, with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis and in Storm’s circumstances, should have regarded the contraventions of s 945A a strong likelihood.

93 First, no one was more familiar with Storm’s clients, the Storm model and its application than Mr and Mrs Cassimatis: PJ at [684].

94 Second, Mr and Mrs Cassimatis exercised their powers as directors and used their “considerable assumed responsibilities to create circumstances which involved their extremely significant control over Storm and its affairs, and over its advisers”: PJ at [691].

95 Third, Mr and Mrs Cassimatis exercised their powers as directors to create education workshops which involved “strong suggestions” to potential investors “to use greater debt for investing than the investors would otherwise have been prepared to do”, including using their powers as directors to encourage the application of the Storm model “to persons who would include retired, or near-retired investors with limited income, few assets, and little or no prospect of rebuilding their financial position in the event of suffering significant loss”. The primary judge observes that these were investors “who a reasonable director with Mr or Mrs Cassimatis’ responsibilities should have concluded had an appropriately conservative approach to investment”: PJ at [692] and [693].

96 Fourth, Mr and Mrs Cassimatis used their powers as directors to create an environment in which there were few circumstances in which clients of Storm were not advised to invest using the Storm model, and those cases where clients were not advised to invest using the model, were “almost all cases where the client simply had no capacity to borrow necessary funds or where the capacity to borrow was too limited given the client’s needs for income”: PJ at [695].

97 The primary judge’s conclusions on this topic at [696] are set out below:

696 In summary, my ultimate conclusion without relying upon hindsight is that a reasonable director of a company in Storm’s circumstances and with Mr or Mrs Cassimatis’ responsibilities would have been aware of a strong likelihood of contravention of the Corporations Act if he or she exercised his or her powers to cause or permit the Storm model to be applied to clients who were in the class pleaded by ASIC, particularly investors who were retired or near retirement with few assets and limited income. Or, to put this conclusion in negative terms, a reasonable director of a company in Storm’s circumstances and with Mr or Mrs Cassimatis’ responsibilities would have been aware of a strong likelihood of contravention of the Corporations Act if he or she did not exercise his or her powers to prevent or prohibit the Storm model from being applied in such indiscriminate circumstances which included application to clients who were retired or near retirement with few assets and limited income.

98 At [697], the primary judge makes the important observation that each of the contraventions of s 945A(1) as found “was caused or permitted by the exercise by Mr and Mrs Cassimatis of their powers and control over Storm” [emphasis added].

99 As to the unique advantage (and related to the observation at [697]), Mr and Mrs Cassimatis had, within Storm, in understanding the application of the Storm model to the circumstances of investors, because of the office they held and their responsibilities within the corporation, the primary judge made these observations at [700]:

700 … [A] reasonable director with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis would have been aware that the extent of his or her responsibilities within Storm gave each of them a degree of knowledge and understanding of Storm which no other person came close to approximating. They would have been aware that this knowledge and understanding of the Storm model and its application was apparent to others. The reasonable director in their position might have drawn some comfort for a conclusion that the basic Storm model was not defective in its fundamentals or its application. But, there would have been little comfort that they could have drawn from these matters to conclude that the advice given by advisers to vulnerable clients in the position of the relevant investors was appropriate. In other words, any approval or absence of warning came from others who had far more limited knowledge of, and far more limited access to, the Storm model, Storm’s clients, and the application of the Storm model to its clients than Mr or Mrs Cassimatis.

100 In addressing the topic of “the consequences of contravention and the burden of alleviating action”, the primary judge expressed these important observations at [772]:

772 Mr and Mrs Cassimatis focused heavily upon the alleged lack of foreseeable likelihood of potential or actual breach. But, provided a breach is reasonably foreseeable, the likelihood of breach is only one matter to be considered in an assessment of the duty of care and diligence. Other crucial matters include the consequences of breach and the burden of alleviating action. Even if I had concluded that contraventions of the Corporations Act were reasonably foreseeable but unlikely (rather than my conclusion that they were likely) the consequences of breach were so significant, and the burden of alleviating action so minimal that it is still possible that a contravention by Mr or Mrs Cassimatis might have occurred. The alleviating action could have taken many forms such as for Mr or Mrs Cassimatis to take any steps to put in place any procedures for SOAs not to advise the application of the Storm model to persons in the pleaded class, broadly persons near or at retirement with few assets and limited income.

101 At [773], the primary judge notes that the “extent” of the adverse consequences that occurred for the 11 vulnerable investors was “undoubtedly” a result of the Global Financial Crisis. The primary judge also notes the content of the appellant’s submissions that there were also other contributing causes to the losses suffered by the vulnerable investors. The primary judge then says this at [773]:

773 … Nevertheless, the existence of other possible causes does not detract from the significance of another cause of the relevant investors’ loss, which was the inappropriate advice by Storm. If Storm had not inappropriately advised the relevant investors to mortgage their home and invest using the Storm model then they would not have invested in this way [in] the first place and would not have been exposed.

102 At [774], the primary judge expresses the following observations concerning the “real possibility” of discovery, at some point, of the likely breaches of s 945A; the characterisation of the consequences of such discovery as “catastrophic for Storm”; and the state of realisation a “reasonable director” would have reached, in Storm’s circumstances, with the responsibilities of Mr and Mrs Cassimatis:

774 Although many of the relevant investors suffered significant, life-altering, losses after the GFC, these losses were neither necessary nor sufficient for Storm’s breach of s 945A of the Corporations Act. Further, although losses of this nature, whether due to the GFC or any other large market fall, might have been one way that the application of the Storm model to vulnerable investors became clear to many people outside Storm, the discovery of these breaches by Storm was not necessarily dependent upon these losses. It is not necessary to speculate upon the different ways that the breaches might have come to the attention of ASIC, whether by an adviser, a client, a competitor, a bank, or otherwise. The short point is that the likelihood of breaches, and the not insignificant size of the class of potentially vulnerable investors (retirees, with limited income and few assets) was such that the breaches were likely to be discovered at some point. At the very least, a reasonable director with Mr and Mrs Cassimatis’ responsibilities, and in Storm’s circumstances, should have realised that discovery of the likely breaches was a real possibility. And the consequences of discovery were catastrophic for Storm.

103 At [775], the primary judge observes that Storm was authorised by its AFSL to provide financial product advice for various classes of financial products including interests in managed investment schemes including index funds. The primary judge observes that the nature and seriousness of the contraventions by Storm were such that an action under s 915C of the Act to suspend or cancel Storm’s AFSL licence was “a real possibility”, and that consequence was not merely one which put Storm’s interests in jeopardy, but rather, “it was a threat to the very existence of Storm because s 911A of the Corporations Act requires a person who carries on a financial services business in Australia to have an AFSL”.

104 The primary judge found that “any reasonable director” would have taken this possibility “extremely seriously”.