FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Clifton (Liquidator) v Kerry J Investment Pty Ltd trading as Clenergy [2020] FCAFC 5

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 172, “rr 20.15(1) and (2)” has been replaced with “rr 20.14(1) and (2)”. |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the respondent/cross appellant to file a further amended notice of cross appeal in the form annexed to its second further amended interlocutory application filed on 5 November 2018 (Interlocutory Application) and marked C.

2. Save to the extent provided by these Orders, the Interlocutory Application be otherwise dismissed.

3. The appeal be dismissed.

4. The respondent’s notice of contention filed on 18 July 2018 be dismissed.

5. The cross appeal be allowed:

(a) Order 1 made in proceeding SAD 261 of 2014 on 24 November 2017 be set aside; and

(b) proceeding SAD 261 of 2014 be remitted to the primary judge or another judge of the Court for determination of the following question:

Was Solar Shop Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) insolvent within the meaning of s 95A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) on 31 July 2011?

6. The appellant/cross respondent’s notice of contention filed on 18 July 2018 be dismissed.

7. The respondent/cross appellant file and serve its submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 261 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 14 days of the date of these Orders.

8. The appellants/cross respondents file and serve their submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 261 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 28 days of the date of these Orders.

9. The question of costs of proceeding SAD 261 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

SAD 342 of 2017 | ||

BETWEEN: | TIMOTHY JAMES CLIFTON AND MARK CHRISTOPHER HALL IN THEIR CAPACITY AS LIQUIDATORS OF SOLAR SHOP AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (IN LIQ) (ACN 092 562 877) Appellant | |

AND: | WUXI SUNTECH POWER CO. LIMITED, (PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA) LICENSE NUMBER 320000400001498 Respondent | |

JUDGE: | BESANKO, MARKOVIC AND BANKS-SMITH JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 February 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the respondent/cross appellant to file a further amended notice of cross appeal in the form annexed to its further amended interlocutory application filed on 5 November 2018 (Interlocutory Application) and marked C.

2. Save to the extent provided by these Orders, the Interlocutory Application be otherwise dismissed.

3. The appeal be dismissed.

4. The respondent’s notice of contention filed on 19 July 2018 be dismissed.

5. The cross appeal be allowed:

(a) Order 1 made in proceeding SAD 275 of 2014 on 24 November 2017 be set aside; and

(b) proceeding SAD 275 of 2014 be remitted to the primary judge or another judge of the Court for determination of the following question:

Was Solar Shop Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) insolvent within the meaning of s 95A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) on 31 July 2011?

6. The appellant/cross respondent’s notice of contention filed on 18 July 2018 be dismissed.

7. The respondent/cross appellant file and serve its submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 275 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 14 days of the date of these Orders.

8. The appellants/cross respondents file and serve their submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 275 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 28 days of the date of these Orders.

9. The question of costs of proceeding SAD 275 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

SAD 343 of 2017 | ||

BETWEEN: | TIMOTHY JAMES CLIFTON AND MARK CHRISTOPHER HALL IN THEIR CAPACITY AS LIQUIDATORS OF SOLAR SHOP AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (IN LIQ) (ACN 092 562 877) Appellant | |

AND: | SMA SOLAR TECHNOLOGY A.G. (JOINT STOCK COMPANY) (GERMANY) REGISTRATION NUMBER HRB 3972 Respondent | |

JUDGE: | BESANKO, MARKOVIC AND BANKS-SMITH JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 February 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the respondent/cross appellant to file a further amended notice of cross appeal in the form annexed to its further amended interlocutory application filed on 5 November 2018 (Interlocutory Application) and marked C.

2. Save to the extent provided by these Orders, the Interlocutory Application be otherwise dismissed.

3. The appeal be dismissed.

4. The respondent’s notice of contention filed on 19 July 2018 be dismissed.

5. The cross appeal be allowed:

(a) Order 1 made in proceeding SAD 276 of 2014 on 24 November 2017 be set aside; and

(b) proceeding SAD 276 of 2014 be remitted to the primary judge or another judge of the Court for determination of the following question:

Was Solar Shop Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) insolvent within the meaning of s 95A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) on 31 July 2011?

6. The appellant/cross respondent’s notice of contention filed on 18 July 2018 be dismissed.

7. The respondent/cross appellant file and serve its submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 276 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 14 days of the date of these Orders.

8. The appellants/cross respondents file and serve their submissions, not exceeding five pages in length, on the question of the costs of proceeding SAD 276 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal within 28 days of the date of these Orders.

9. The question of costs of proceeding SAD 276 of 2014, the appeal, the Interlocutory Application and cross appeal be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[4] | |

[5] | |

[9] | |

[16] | |

[21] | |

The appointment of voluntary administrators and of the Liquidators | [28] |

[29] | |

[33] | |

[36] | |

[43] | |

[45] | |

[49] | |

[54] | |

[60] | |

[72] | |

[77] | |

[77] | |

[88] | |

[91] | |

[98] | |

[104] | |

[115] | |

[119] | |

Review of discovery since the commencement of the hearing of the appeal | [128] |

[132] | |

The effect of the Liquidators’ ongoing failure to make proper discovery | [190] |

[211] | |

[212] | |

[214] | |

[235] | |

[236] | |

[309] | |

[309] | |

[323] | |

[333] | |

[336] | |

[337] | |

[366] | |

[381] | |

[389] | |

[390] | |

[392] | |

[393] | |

[412] | |

[423] | |

Ground 5 of the appeals and grounds 1 and 2 of the cross appeals | [424] |

[432] | |

[437] | |

[455] | |

[456] | |

[459] | |

[471] | |

[472] | |

[474] | |

[477] | |

[479] | |

[498] | |

[504] | |

[516] | |

[533] | |

[542] | |

[552] | |

[557] | |

[564] | |

[576] | |

[579] | |

[583] | |

[585] | |

[611] | |

[618] | |

[626] | |

[631] | |

[644] | |

[648] | |

[649] | |

[650] | |

[655] | |

[661] | |

[662] | |

[663] | |

Other items said to be available/excluded as at 30 April 2011 | [668] |

Access to cash and cash equivalents/trade and other receivables | [668] |

[672] | |

[673] | |

[674] | |

[675] | |

[676] | |

[676] | |

[679] | |

[680] | |

[681] | |

[682] | |

[687] | |

[687] |

THE COURT:

1 There are three appeals before the Court brought by Timothy James Clifton and Mark Christopher Hall in their capacities as joint and several liquidators (Liquidators) of Solar Shop Australia Pty Limited (in liquidation) (Solar Shop). The Liquidators challenge findings made by the primary judge in response to a separate question about the date on which Solar Shop became insolvent within the meaning of s 95A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act): Clifton v Kerry J Investment Pty Ltd trading as Clenergy [2017] FCA 1379.

2 The respondents to the appeals are respectively Kerry J Investment Pty Limited trading as Clenergy (Kerry J), Wuxi Suntech Power Co Limited (Wuxi) and SMA Solar Technology A.G. (SMA) (collectively Respondents). Each of Kerry J, Wuxi and SMA has filed a cross appeal and a notice of contention in the appeal against it. The Liquidators have filed notices of contention in the cross appeals. Whilst the Respondents were separately represented and filed separate written submissions, in effect the Respondents each adopted the submissions of SMA (or, as to the issue of inventory, Kerry J). Therefore, when we refer to the submissions of the Respondents it is on the basis that those submissions are made jointly. On occasion for clarity we refer to the submissions of an individual Respondent but regardless those submissions are taken to have been made by the Respondents jointly.

3 The hearing of the appeals spanned some five days and assumed a level of complexity because it became apparent that two documents had not been discovered to all of the Respondents. The effect of this revelation, and the relief sought as a consequence, is further described below. Before turning to it and to the substantive issues raised by the appeals and cross appeals, it is convenient to set out the background facts.

4 The following background facts, which we understand not to be in dispute, are taken substantially from the primary judge's reasons.

5 Solar Shop was incorporated on 20 April 2000. It carried on business as a supplier and installer of solar energy systems and, until 2009, solar water heating systems.

6 Solar Shop had three wholly owned subsidiaries: Solar Hut Pty Limited (Solar Hut) which engaged in online sales under the name “SunSavers”; Solar Financial Solutions Pty Limited which offered finance to purchasers under the name “Sunworks”; and SA Commercial Solar Pty Limited which promoted large-scale solar systems for commercial applications under the name “CommSolar”. Solar Shop also held a 50% interest in Sunray Tracker Pty Limited and a 40% interest in Metropolitan Metering Assets Pty Limited.

7 The shareholders in Solar Shop and their respective holdings changed over time such that:

(1) from April 2003 until about 12 February 2007 Adrian and Tanya Ferraretto were its sole shareholders holding shares in their own capacity and as trustees for the A and T Ferraretto Family Trust;

(2) on or about 12 February 2007 Solarise Pty Ltd (Solarise), a company associated with Mr Russell Mourney, acquired a substantial holding in Solar Shop and members of Solar Shop’s management also acquired shares;

(3) on 6 May 2009 HMC Australian Private Equity Fund 1 GP, LP (HAPE 1), a private equity fund managed by Harbert Management Corporation (Harbert), acquired shares in Solar Shop for a consideration of $7 million by acquiring shares from the Ferrarettos, Solarise in its capacity as trustee for the Mourney Family Trust and Mr Stone and Ms Morris in their capacity as trustees of the Morristone Family Trust; and

(4) in October 2010 Solar Shop bought back shares associated with the Ferrarettos for $10 million and the Ferrarettos sold shares to HAPE 1, its CEO, Anthony Thornton, and Solar Shop Australia Management Team Pty Ltd (SSAMT).

8 As at 19 October 2010 Solar Shop’s shareholders comprised:

(1) HAPE 1 which held 36,152 shares or 50.2%;

(2) Mr and Mrs Ferraretto who held 20,849 shares or 28.9%;

(3) Mr Thornton who held 11,112 shares or 15.4%;

(4) James Leggett who held 2,292 shares or 3.2%; and

(5) SSAMT which held 1,637 shares or 2.3%.

Solar Shop’s arrangements with its financiers

9 Westpac Banking Corporation (Westpac) was Solar Shop’s banker. On 19 October 2010 Solar Shop entered into a facility agreement with Westpac (2010 Facility Agreement) which superseded a business finance agreement that it had entered into with Westpac in 2009 dated 4 May 2009 (May 2009 Business Finance Agreement).

10 Pursuant to the 2010 Facility Agreement Westpac agreed to make six different facilities available to Solar Shop, each referred to as “tranches”. Relevantly:

(1) tranche A comprised an overdraft with a decreasing limit: $3.5 million until 30 October 2010, $2.5 million in the period from 31 October to 29 November 2010 and $1.0 million from 30 November 2010; and

(2) tranche F was a bill acceptance discount facility with a limit of $10 million. Its principal purpose was to fund Solar Shop’s share buy-back from the Ferrarettos.

11 Clause 8.2 of the 2010 Facility Agreement required Solar Shop to make quarterly repayments of principal of $500,000 each, commencing on 31 December 2010 and ending on 30 June 2012, and to repay the balance of tranche F (and the balance owing under any other tranches) on or before the termination date, 19 October 2012.

12 Pursuant to a loan agreement dated 6 May 2009 between Solarise, Mr Mourney, Solar Shop and HAPE 1 (Solarise Loan Agreement), Solarise provided unsecured vendor finance for the shares it sold to Solar Shop (Solarise Loan). Relevantly in that agreement:

(1) clause 1.1 included the following definitions:

Bank means Westpac Banking Corporation (ABN 33 007 457 141)

Bank Debt means all the money and amounts (in any currency) that [Solar Shop] is or may become liable at any time (presently, prospectively or contingently, whether alone or not and in any capacity) to pay to, or for the account of, the Bank pursuant to the terms of the Bank Finance Documents.

Buy-Back Date means the date on which the Share Buy-Back Agreement completes and the Buy-Back becomes effective.

Permitted Payment means:

(a) any payment that the Bank has consented to in writing; or

(b) any payment permitted under clause 6.4.

Repayment Date means in respect of any amount of the Principle Sum that is not a Notified Claim Amount or Respective Proportion Amount that earliest of:

…

(b) the second anniversary of the Buy-Back Date; and

…

Solarise Debt means all money and amounts that [Solar Shop] is or may become liable at any time (presently, prospectively or contingently, whether alone or not and in any capacity) to pay to or for the account of Solarise in accordance with the terms of this agreement.

Subordination Period means the period from the date of this document until the second anniversary of the Buy-Back Date.

(2) clause 4.1 required Solar Shop to repay the principal sum, $5,178,682.13, to Solarise on “the Repayment Date”, 22 May 2011;

(3) clause 5 provided that interest accrues daily on the Principal Sum (as defined) plus any capitalised interest from time to time at the interest rate calculated in accordance with the specified formula; and

(4) clause 6 provided that:

6.1 Solarise Debt subordinated

Solarise acknowledges and agrees that the Solarise Debt and all related rights, claims and payments are subordinated and postponed to, and rank in priority after, the Bank Debt and all related rights, claims and payments, on the terms of this agreement. [Solar Shop’s] obligations and liabilities in respect of the Solarise Debt are conditional (only to the extent set out in this agreement) on the Subordination Period ending.

6.2 Solarise Debt not payable

Despite any agreement to the contrary, during the Subordination Period none of the Solarise Debt is payable or repayable except for the purpose of a Permitted Payment.

6.3 Continuing subordination

The Subordination applies to the present and future balances of the Bank Debt and Solarise Debt. Solarise agrees and acknowledges that the Subordination is irrevocable and a continuing subordination until the Subordination Period ends, and is not discharged by any payment, settlement of account, an Insolvency Event or anything else.

6.4 Permitted Payment

If at any time all of the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) no Bank Debt is due and unpaid;

(b) no Subordination Default subsists;

(c) neither [Solar Shop] nor Solarise is in breach of the provisions of this agreement; and

(d) no Insolvency Event had occurred in respect of [Solar Shop]or Solarise,

[Solar Shop] will pay, repay, satisfy or discharge, and Solarise may receive and retain payment of, the following amounts due at that time in respect of the Solarise Debt:

(a) accrued interest in accordance with the terms of this agreement; and

(b) payments of the Principal Sum in accordance with the terms of this agreement; and

(c) amounts notified by the Bank to [Solar Shop] in writing as being permitted under this clause.

13 On 20 May 2009 Westpac, Solarise and Solar Shop entered into a deed of subordination (Subordination Deed) which relevantly included:

(1) at clause 1 that:

“Business Finance Agreement” means the Business Finance Agreement dated 4 May 2008 between Westpac and the Borrower “Debts” means the Westpac Debt and the Solarise Debt;

“Debts” means the Westpac Debt and the Solarise Debt;

…

“Permitted Payments” has the meaning stipulated in clause 8;

…

“Solarise Debt” means the aggregate of all monies, debt and liabilities owing from time to time now or in the future on any account or remaining unpaid by [Solar Shop] to Solarise pursuant to the Loan Agreement”

“Subordination Default” means any one or more of:

(a) the occurrence of a “Default Event” as defined in the Business Finance Agreement;

(b) [Solar Shop’s] failure to pay any Westpac Debt or Solarise Debt when due or within any applicable grace period;

(c) the Westpac Debt or Solarise Debt becoming due and payable before its due date other than at [Solar Shop’s] option.

“Westpac Debt” means the aggregate of all of the amounts owing from time to time on any account by [Solar Shop] to Westpac pursuant to the Business Finance Agreement, or pursuant to the Westpac Securities, whether actual or contingent, present or future including, without limitation, all of the facilities under the Business Finance Agreement;

“Westpac Securities” means those securities listed as security the facilities provided by Westpac to [Solar Shop] under the Business Finance Agreement;

(2) at clause 4 titled “Subordination” that:

4.1 The Lenders and [Solar Shop] agree that the Solarise Debt is subordinated to the Westpac Debt.

4.2 Until:

4.2.1 the Westpac Debt has been paid or satisfied in full; or

4.2.2 the Solarise Debt is repaid with the written consent of Westpac, payment by [Solar Shop] to Solarise of the Solarise Debt or any part of it is postponed, despite any other arrangement to the contrary, except for the Permitted Payments and subject to this Deed.

(3) at clause 5 that Solar Shop agrees with each of Solarise and Westpac that it may not, without Westpac’s prior written consent and for so long as any of the Westpac Debt (adopting the definition from the Subordination Deed) remains outstanding, among other things, make any payment in satisfaction of the Solarise Debt other than the Permitted Payments; and

(4) at clause 6 that Solarise agrees with Solar Shop and Westpac that, so long as any of the Westpac Debt remains outstanding, Solarise must not, without Westpac’s prior written consent or otherwise as permitted by the Subordination Deed, among other things, receive any payment or thing of value in satisfaction of any part of the Solarise Debt other than the Permitted Payments or demand, sue for or take any other action to cause or enforce payment of any of the Solarise Debt except the Permitted Payments.

14 Clause 8 of the Subordination Deed titled “Permitted Payments” was central to the issue raised both before the primary judge and on appeal about the time at which the Solarise Loan fell due for repayment. It relevantly provided:

8.1 If, at any time, all of the following conditions are satisfied:

8.1.1 no Westpac Debt is due and unpaid; and

8.1.2 no default under the Business Finance Agreement subsists; and

8.1.3 neither Solarise or [Solar Shop] are in breach of the provisions of this Deed; and

8.1.4 no Insolvency Event has occurred in respect of Solarise or [Solar Shop]; and

8.1.5 no Subordination Default subsists,

then [Solar Shop] may pay, repay, satisfy or discharge Solarise, and Solarise may receive and retain payment of the amounts contemplated in the Amortisation Schedule in the manner and at the times contemplated by the Amortisation Schedule (“Permitted Payments”).

8.2 To avoid doubt:

…

8.2.2 If [Solar Shop] does not make a capital payment (“Unpaid Capital Payment”) on the date which that capital payment is permitted to be made in accordance with the Amortisation Schedule (“Relevant Capital Payment Date”), [Solar Shop] may make the Unpaid Capital Payment at any time following the Unpaid Capital Payment Date, provided:

(a) the conditions set out in this clause 8 are satisfied; and

(b) [Solar Shop] notifies Westpac in writing within 2 business days of the date when the Unpaid Capital Payment is actually made.

8.3 Notwithstanding anything else in this Deed or the Loan Agreement, any payments by [Solar Shop] in connection with the Solarise Debt (whether to Solarise, Harbert or anyone else) which are not Permitted Payments must not be made without Westpac’s prior written consent (which will not be unreasonably withheld or delayed).

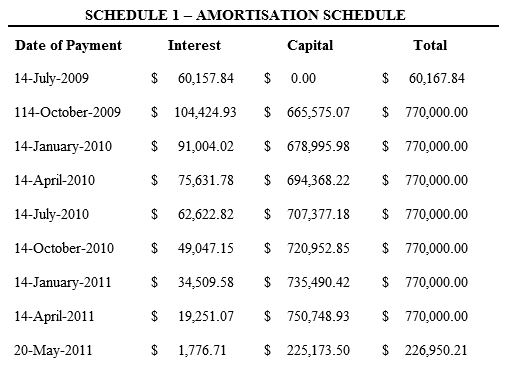

15 The Amortisation Schedule referred to in cl 8 provided:

Note: The interest payments set out in the table above have been calculated on the basis that capital payments will be made on the Dates of Payment. [Solar Shop] may, but is not obliged to, make the capital payments on the Dates of Payment. If [Solar Shop] does not make any capital payments, or makes reduced capital payments, the interest payable on each Date of Payment will increase accordingly.

In addition, if the amount of the interest payments are increased from time to time, as a result of the [non] payment of capital, the total amount payable by [Solar Shop]to Solarise will increase over the term of the Loan such that the total amount permitted to be paid on 20 May 2011, when taken together with the total permitted payments on each of the other Dates of Payment, will need to increase to allow [Solar Shop] to make a payment to Solarise of the total amount of capital due and payable under the Loan Agreement together with all interest accrued in accordance with the terms of the Loan Agreement, provided that the total capital payable will not exceed $5,178,682.13.

16 Renewable energy certificates (RECs) assumed some importance both in the proceedings before the primary judge and on appeal. They are a form of incentive under a scheme established by the Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000 (Cth) (Renewable Energy Act). From about January 2011 the RECs which were at issue in the proceedings became known as “small scale technology certificates”, but Solar Shop continued to refer to them as RECs.

17 Relevantly s 26 of the Renewable Energy Act provides that: a REC is not valid until it has been registered; when the Regulator has been notified that a REC has been created, it must determine whether the REC is eligible for registration; and if the Regulator determines that a certificate is eligible for registration, it must create an entry for the certificate in the relevant register and record the person who created the REC as its owner.

18 Customers purchasing a solar system from Solar Shop were entitled to RECs upon installation of the system based on the power generation capacity of the system installed. That is, the higher the capacity the greater the entitlement. Once generated, RECs could be sold to a clearing house established under the Renewable Energy Act or privately to a purchaser for a negotiated price.

19 Solar Shop agreed with its customers at point of sale to purchase their RECs in exchange for a reduction in the purchase price of the system. Solar Shop would later sell the RECs so acquired, endeavouring to do so at a profit. However, there was a risk that the clearing house or market price would decline in the period between Solar Shop’s entry into the consumer contract with its customer and the time, usually several months later after installation was complete, when the consumer became entitled to the RECs and could assign them to Solar Shop.

20 The effect of the RECs scheme was that Solar Shop had two income streams: the amounts paid by consumers for the solar systems they purchased and the amounts derived from the sale of RECs.

21 On 9 December 2010 Solar Shop informed Westpac that its operating profit had declined significantly and that, as at 31 December 2010, it was likely to be in breach of covenants in the 2010 Facility Agreement. This position was confirmed by letter dated 15 February 2011 when Solar Shop informed Westpac that it was in breach of three of the four financial covenants in cl 12.12 of the 2010 Facility Agreement.

22 On 12 January 2011 Westpac appointed John Hart of Ferrier Hodgson to undertake an independent review of Solar Shop’s financial performance and status. The purpose of the review was to enable Westpac to obtain a better understanding of Solar Shop and to consider:

(1) Solar Shop’s:

(a) immediate and medium term cash flow requirements;

(b) ability to continue to trade and to meet its obligations;

(c) current available strategies to assist with a turnaround in profitability and cash flow; and

(2) the alternatives available to Westpac in the event that it needed to realise its security.

23 On 28 February 2011 Ferrier Hodgson reported to Westpac (First Ferrier Hodgson Report). In its executive summary Ferrier Hodgson reported, among other things, that:

(1) between July 2010 and 31 December 2010 Solar Shop’s growth had slowed and it had incurred an operating loss after tax of $1 million;

(2) Solar Shop recognised revenue on completion of installations rather than on receipt of a confirmed order with deposit paid;

(3) as at 31 December 2010 Solar Shop had a backlog of over 3,600 installations which represented future revenue of over $70 million;

(4) in the six months to 31 December 2010 installations had averaged 676 per month against orders received of 879 per month. Had installations kept pace with the rate of sales, revenue may have been approximately $20 million higher and a net profit after tax of approximately $3 million achieved compared with the loss of $1 million;

(5) evidence of mismanagement or fraud had begun to emerge in Sunsavers;

(6) an internal review of Sunsavers completed by Solar Shop in February 2011 indicated that estimated EBITDA had been overstated by approximately $3.2 million;

(7) the decline in net profit before tax was mainly due to:

(a) the decline in revenue and gross margin percentage for Sunsavers;

(b) reduced gross margin percentage for Solar Shop offsetting revenue growth;

(c) increased costs in anticipation of growth not covered by growth in gross margins; and

(8) as at 31 December 2010 Solar Shop had cash on hand of approximately $5.5 million. The cash position improved in the six months from 1 July 2010 to 31 December 2010 as a result of liquidation of RECs, the deferment of approximately $3.2 million in creditor payments through arrangements with three major suppliers and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), reduction in accounts receivable and reduction in solar rebates receivable.

24 The First Ferrier Hodgson Report contained a number of recommendations including that Westpac:

(1) “give strong consideration to continuing to support” Solar Shop, at least in the short term including by providing additional guarantee and forex requirements sought by Solar Shop, subject to Solar Shop achieving satisfactory performance criteria based on its forecast;

(2) give consideration to continuing to reserve its rights in respect of the existing breaches of covenants;

(3) monitor Solar Shop’s performance on a monthly basis, including achievement of its required rate of installations;

(4) notify Solar Shop that it should not make any repayment of the Solarise Loan without Westpac’s approval;

(5) assess Solar Shop’s financial position as at 30 April 2011, including assessment of the then current order backlog and forecasts for the balance of 2011;

(6) subject to Solar Shop’s financial performance, give consideration to the extent to which it may permit a part payment of the Solarise Loan; and

(7) make any repayment of the Solarise Loan subject to a reduction in Westpac’s own debt to at least $3 million to improve Westpac’s security position.

25 On 28 April 2011 Solar Shop informed Westpac that it was “not in compliance” with the same three financial covenants in cl 21.2 of the 2010 Facility Agreement as had been notified in December 2010 and February 2011. On 27 May 2011 Westpac wrote to Solar Shop confirming the breaches of covenants, reserving its rights to take action in relation to those breaches, noting that it did not waive the “events of default” and that as a result of those breaches all facilities provided by Westpac to Solar Shop “are on demand”.

26 On 19 July 2011 Ferrier Hodgson provided Westpac with a second independent business review of the Solar Shop group performance in the period from 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2011 (Second Ferrier Hodgson Report). In that report Ferrier Hodgson:

(1) noted a number of issues about the group’s performance including that revenues were down by $13 million, EBITDA was $7 million below the revised budget, there were continued below budget performances as installation targets were not met for a variety of reasons and RECs were being sold at a price less than had been paid for them; and

(2) made recommendations including that, subject to compliance with certain conditions including that Harbert and/or other shareholders immediately inject $5 million into the business and that there be deferral of the current repayment proposal of the Solarise Loan, Westpac “may consider granting the request to 12 month deferral of debt amortisation” but that it should not “increase the overdraft facility from $1.0m to $3.0m, the deferral of vendor loan payments will alleviate the requirement for this funding”.

27 Westpac did not agree to increase the overdraft limit nor did it agree to waive payment of the amortisation payments of $500,000 per quarter in relation to the tranche F facility (see [10] above).

The appointment of voluntary administrators and of the Liquidators

28 On 21 October 2011 the directors of Solar Shop appointed voluntary administrators. On 25 November 2011 a meeting of creditors resolved that Solar Shop should be wound up and the Liquidators were appointed as joint and several liquidators.

THE FIRST INSTANCE PROCEEDINGS

29 The Respondents were each suppliers to Solar Shop. The Liquidators commenced proceedings against each of those entities seeking to recover amounts for unfair preferences pursuant to s 588FF of the Corporations Act as follows:

in proceeding SAD261/2014 against Kerry J (Kerry J Proceeding) the sum of $417,075.26 or, in the alternative, the sum of $327,449.46;

in proceeding SAD275/2015 against Wuxi (Wuxi Proceeding) the sum of US$1,814,066.80; and

in proceeding SAD276/2014 against SMA (SMA Proceeding) the sum of €2,445,850.21 or, in the alternative, €1,800,797.89,

(collectively, First Instance Proceedings).

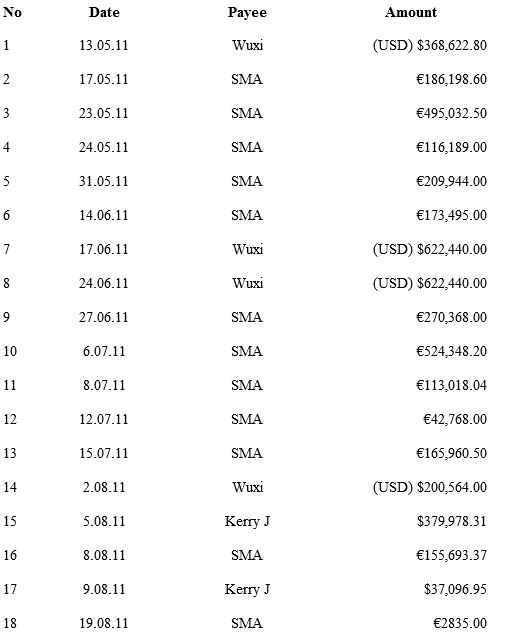

30 By reason of the definitions in ss 9, 513B and 513C of the Corporations Act, the relation back day for Solar Shop is 21 October 2011 and the relation back period is 22 April 2011 to 21 October 2011. The payments received by each of Kerry J, Wuxi and SMA in that period which were the subject of the First Instance Proceedings are:

The Liquidators contended that Solar Shop was insolvent at the time it made each of these payments and the Respondents disputed that was so.

31 On 25 May 2016 orders were made in each of the First Instance Proceedings pursuant to r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) that a separate question be heard and determined which was in the following terms: “did [Solar Shop] become insolvent within the meaning of s 95A of the Corporations Act and, if so, when?”. The Court also ordered that the hearing of the separate question in each of the First Instance Proceedings was to take place concurrently.

32 On 24 November 2017 the primary judge delivered judgment on the separate question. His Honour found that the Liquidators had not proved that Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 January 2011, 30 April 2011 and 31 May 2011 and determined the separate question in each of the First Instance Proceedings by holding that Solar Shop had become insolvent by 31 July 2011: reasons at [366]-[367]. It is from those findings that the appeals and cross appeals that are now before the Court are brought.

33 Before the primary judge, the Liquidators sought a finding that Solar Shop was insolvent by not later than either 31 January 2011; in the alternative, 30 April 2011; or, further in the alternative, 22 May 2011. The primary judge noted that SMA and Kerry J contended for different dates: SMA contended that Solar Shop had not become insolvent until 29 July 2011 and possibly not until 4 August 2011 and Kerry J submitted that it had not become insolvent until 9-16 August 2011. The primary judge expressed the view that, because of the terms of the separate question, the Court was not confined to any of those dates and did not accept the Respondents’ submission that the Liquidators were confined to the three dates they had nominated: at [6].

34 The evidence before the primary judge was entirely documentary. The Liquidators, Kerry J and SMA each obtained reports from forensic accountants. Relevantly, the Liquidators obtained four reports from Brian Morris and SMA obtained two reports from David Lombe, one dated 4 December 2015 (First Lombe Report) and the second dated 9 September 2016 (Second Lombe Report). However, the parties agreed that, instead of the Court dealing with the numerous objections that were made to the forensic accountants’ reports, they would have the “status of an aide to the submissions of the party retaining them” which, his Honour observed, is contemplated by r 5.04(3) item 19 of the Rules and is consistent with the approach adopted by Gordon J in Noza Holdings Pty Limited v Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCA 990: at [7].

35 Having observed that the Liquidators bore the onus of establishing Solar Shop’s insolvency, the primary judge considered each of the matters relied on by the Liquidators to establish Solar Shop’s insolvency as at the dates for which they contended.

36 The first matter that the primary judge considered was the Solarise Loan because, central to the Liquidators’ case, was their contention that the Solarise Loan became due and payable on 22 May 2011 and that Solar Shop did not have the resources, nor any plan, at any time during 2011 to repay that loan when it did so. It was common ground that the question of whether the Solarise Loan became due and payable on 22 May 2011 turned principally on whether it remained subordinated after that date to the Westpac Debt. At [83] of the reasons, his Honour noted that that question gave rise to the following issues:

(a) did the Subordination Deed operate to make the Solarise Loan subordinate to the Westpac Debt only to 22 May 2011?

(b) alternatively, did Westpac agree in May 2011 to [Solar Shop] executing an agreement with Solarise which rendered the whole of the Solarise Debt then due and payable on demand?

(c) alternatively, did the Subordination Deed, by reason of the principles of abandonment, cease to be “valid and efficacious” as and from the time of the tripartite negotiations involving Westpac, Solarise and [Solar Shop] in October 2010 in relation to the negotiation of the new facility agreement?

(d) alternatively, did an indemnity obligation in an agreement made between [Solar Shop] and Solarise in May 2011 give rise to a new debt which was immediately due and payable on [Solar Shop's] failure to pay the Solarise Debt on 22 May 2011?

37 In relation to the first issue, the primary judge found that the Subordination Deed did not operate to make the Solarise Loan subordinate to the Westpac Debt only until 22 May 2011. His Honour held that, while Solar Shop had been authorised to make the Permitted Payments which would have had the effect of repayment of the Solarise Loan by 22 May 2011, it was not required to do so. The parties thus contemplated that the Solarise Debt may continue past 22 May 2011. The primary judge found that, as Solar Shop did not make the Permitted Payments to Solarise before 22 May 2011, it could only make a payment after that date with Westpac’s prior written consent, which could not be unreasonably withheld. Accordingly the primary judge concluded that this basis for the claim that the Solarise Loan was due and payable on 22 May 2011 failed: at [96]-[97].

38 In relation to the second issue, the primary judge found that cl 8.3 of the Subordination Deed did not have the effect of an agreement by Westpac to Solar Shop entering into a fresh agreement with Solarise which, in turn, had the effect of making the Solarise Debt due and payable on demand: at [110]-[113].

39 In relation to the third issue, the primary judge rejected the Liquidators’ contention that Solar Shop, Westpac and Solarise were, from the time of entry into the 2010 Facility Agreement, proceeding on the basis that the Subordination Deed was no longer operative and had been abandoned: at [128]-[133].

40 The fourth issue concerned the effect of cl 9 of an agreement referred to by the primary judge as the 2011 Solarise Agreement which was the subject of an email dated 19 May 2011 from Mr Mourney to Mr Thornton and Jeremy Steele, a director of Solar Shop appointed as a representative of Harbert. Mr Mourney’s email attached the 2011 Solarise Agreement and noted that he had it “drafted as discussed to allow us to continue past 22 May if required”. Clause 9 of the 2011 Solarise Agreement was titled “Indemnity” and provided:

[Solar Shop] must indemnify Solarise against all claims and all losses, costs, liabilities and expenses incurred by Solarise, arising wholly or in part from an act or omission of [Solar Shop] or its employees, agents or contractors in relation to this agreement.

41 The primary judge rejected the Liquidators’ submissions that cl 9 of the 2011 Solarise Agreement created an obligation, distinct and separate from Solar Shop’s debt obligation, which was not subject to the Subordination Deed and that as soon as Solar Shop failed to pay the Solarise Debt, after demand was made for it on 27 May 2011, Solar Shop’s liability under the indemnity in cl 9 crystallised. The primary judge referred to his earlier finding that the Subordination Deed continued in force and that Solarise remained bound by cl 6 of that deed from receiving any payment in satisfaction of its debt, taking any action to recover its debt or receiving any money from Solar Shop directly or indirectly. Thus, even if cl 9 of the 2011 Solarise Agreement gave rise to a separate obligation, it could not have been enforced by Solarise: at [135]-[136].

42 The primary judge concluded that Solar Shop’s liability to Solarise remained subordinated to the amounts owing to Westpac and, that being so, the Solarise Loan did not become due and payable while the indebtedness to Westpac remained outstanding. For that reason the Solarise Debt could not be taken into account at any of the alternate dates of insolvency for which the Liquidators contended: at [136].

Solar Shop’s liability to the ATO

43 The primary judge then turned to consider Solar Shop’s liability to the ATO, which the Liquidators contended was another matter which resulted in a finding of insolvency at each of the alternate dates propounded by them.

44 Having considered the evidence, the primary judge found that it was apparent that Solar Shop was unable to meet its taxation obligations, it did not make payment arrangements with the ATO until the amounts owing were overdue and, when it did make such arrangements, it often defaulted: at [154]. The primary judge was satisfied that the Liquidators’ inclusion of Solar Shop’s liability to the ATO at each of the alternative dates at which they contended Solar Shop was insolvent was appropriate: at [170].

Overview of the Liquidators’ claims of insolvency

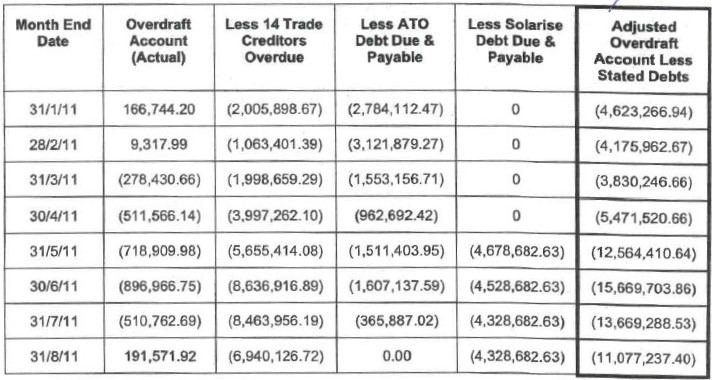

45 Before the primary judge, the Liquidators sought to prove Solar Shop’s insolvency as at each of the dates on which they contended that it was insolvent by reference to the debt position at a succession of month ends. For that purpose the Liquidators relied on an “aide memoire”, marked as exhibit P4, which analysed Solar Shop’s debt position at month end for each month in the period January to August 2011 (Aide Memoire). The Aide Memoire included for each month the aggregate of Solar Shop’s overdraft balance, the amounts said to be due to its 14 principal trade creditors, the debt to the ATO and, for the period 31 May to 31 August 2011, the amount of the Solarise Debt said to be due and payable.

46 At [173]-[176] of the reasons, the primary judge made the following observations about the Aide Memoire:

Although [Solar Shop] had hundreds of trade creditors, the Aide Memoire records [Solar Shop’s] indebtedness to only 14. The Liquidators selected these creditors as a matter of convenience because they considered [Solar Shop’s] own Aged Creditor Reports in respect of all the creditors to be unreliable.

The Liquidators relied on the figures in the column headed “Adjusted Overdraft Account Less Stated Debts” as indicating the debts due and payable at the various month ends which [Solar Shop] was unable to pay.

The Respondents challenged the accuracy of a number of the figures in the Aide Memoire and pointed to other features not taken into account by the Liquidators. I will refer to them below. The Respondents accepted, however, the accuracy of the figures in the column headed “Overdraft Account (Actual)”. Those figures are derived from the Westpac account statements.

In these reasons, I will adopt the framework set out in the Liquidators’ Aide Memoire. It will be necessary in addition to have regard to the circumstances more generally concerning [Solar Shop’s] debts and the resources available to it, especially given that the Liquidators did not provide a cash flow analysis for [Solar Shop] for any of the three dates by which they contended that it was insolvent.

47 The Aide Memoire provided:

48 The primary judge considered Solar Shop’s solvency as at the three dates on which the Liquidators contended it was insolvent, 31 January 2011, 30 April 2011 and 22 May 2011, and found that the Liquidators had failed to establish that it was insolvent at any of those dates.

49 The primary judge noted at [177] that as at 31 January 2011 the Liquidators relied on the following indicia of insolvency:

(a) [Solar Shop] was in breach of its banking facilities, rendering its bank debt of approximately $17 million payable on demand;

(b) more than $1.2 million of amounts due to the 14 significant trade creditors were outside terms and accordingly overdue (in addition to those which were current and not overdue);

(c) [Solar Shop] owed $2,784,112.47 to the ATO and was unable to pay that amount without a payment plan;

(d) the combined effect of overdue creditors and the outstanding debt to the ATO was that [Solar Shop] owed $3,854,907.68 which was outside terms, and $2,854,907.68 in excess of its overdraft limit;

(e) [Solar Shop] had sustained a trading loss of $1.946 million in January 2011 (although the evidence to which the Liquidators pointed to support this proposition was [Solar Shop’s] trading performance for the first seven months of the 2011 financial year);

(f) the forecast profits from one arm of the business (Sunsavers) were overstated;

(g) by 31 January 2011, it was apparent that [Solar Shop] had no resources available to meet the repayment of the Solarise Loan of over $5.2 million which was to fall due on 22 May 2011;

(h) by 31 January 2011, [Solar Shop’s] shortage of working capital was endemic and thereafter it was outside terms in paying its creditors and in paying the debt to the ATO.

50 The primary judge made the following findings:

(1) while Solar Shop was in breach of covenants in the 2010 Facility Agreement it continued to have access to the facilities provided by Westpac; the monies advanced pursuant to the 2010 Facility Agreement had not been declared due and payable by Westpac; and, while the breach of covenants put Solar Shop in a vulnerable position, that was not a significant indicia of insolvency: at [188];

(2) as at 31 January 2011 amounts were overdue to seven of the 14 trade creditors included in the Aide Memoire. The Respondents accepted that amounts were due to each of these creditors but disputed that the amounts were outside trading terms in relation to five of them, namely Optimum Media Direction Pty Limited (Optimum), Fasteners Australia Pty Limited (Fasteners), BlueScope Distribution Pty Limited (BlueScope), Lawrence & Hanson Group Pty Ltd (L&H) and Matrin Australia Pty Limited (Matrin). The primary judge undertook the task of identifying the terms of trade between Solar Shop and each of those five trade creditors in order to establish whether the amounts shown as owing to each of them in the Aide Memoire as at 31 January 2011 were in fact due. His Honour found that:

(a) the Liquidators had not proved Solar Shop’s trading terms with Optimum such that a finding could not be made that Solar Shop was outside agreed payment terms in relation to the amount of $86,922.50 due to Optimum as at 31 January 2011 or at either of the alternative dates for which the Liquidators contended: at [194];

(b) Solar Shop was outside the agreed payment terms in respect of the amount of $130,000 due to Fasteners as at 31 January 2011: at [200];

(c) BlueScope had reached some agreement with Solar Shop which was reflected in Solar Shop’s pattern of payment to it such that his Honour was not willing to find that Solar Shop was outside the agreed trading terms in relation to the amount of $292,000 due to BlueScope as at 31 January 2011 or the amounts due as at any of the alternative dates relied on by the Liquidators: at [206];

(d) Solar Shop was outside the agreed payment terms in relation to the amount of $141,976.67 due to L&H as at 31 January 2011: at [211]; and

(e) there was an implied agreement between Solar Shop and Matrin for extensions of time within which Solar Shop was to pay Matrin’s accounts. Thus his Honour was not satisfied that the amount of $35,860 was due and payable to Matrin: at [217];

(3) in relation to the January 2011 trading loss of $1.946 million, the primary judge was of the opinion that the fact that a loss is incurred in one month is not of itself a strong indicator of insolvency. After making a number of observations about trading in January, his Honour noted that the same profit and loss statement on which the Liquidators relied to support the trading loss also showed that Solar Shop’s net profit after tax for the 12 month period ending in January 2011 was $538,000. The primary judge concluded that he did not regard the trading loss for January 2011 as a significant factor: at [220]-[223];

(4) the primary judge accepted that the apparent fraud in the Sunsavers business had a significant impact on Solar Shop at a time when it was experiencing other cash flow difficulties but noted that the Liquidators did not suggest that its effect required an adjustment to the figures in the Aide Memoire at any of the dates upon which they relied. His Honour observed that, instead, it helped to explain the financial position of Solar Shop at the various dates under review: at [229]; and

(5) given the earlier finding that the Solarise Loan was not due and payable on 22 May 2011, the position in relation to it as at 31 January 2011 did not have to be considered.

51 Having regard to those findings the primary judge found that the amount for “Adjusted Overdraft Less Stated Debts” to be included in the Aide Memoire as at 31 January 2011 should be $2,899,344.94.

52 The primary judge then turned to consider whether Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 January 2011. At [237] his Honour accepted that in determining that question it was appropriate to have regard to all of the resources available to a company by which it could meet its debts and said:

Even if it could be said that the whole of the trade receivables and REC receivables were not immediately available to [Solar Shop] to meet its debts, it seems probable that a sufficient amount could have been realised within a relatively short time so that [Solar Shop] could meet the due debts of $2.9 million. Some of the cash and cash equivalents could also have been used for that purpose.

53 The primary judge was not therefore satisfied that the Liquidators had shown that Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 January 2011.

54 In relation to 30 April 2011 the primary judge noted at [242] that, in addition to those matters relied on by the Liquidators as at 31 January 2011 to prove insolvency, they relied on:

(a) by 30 April 2011, [Solar Shop’s] debt of $2.444 million to another supplier, Bosch Solar Energy AG (Bosch), had become overdue and was never brought back within terms;

(b) the adjusted overdraft account less stated debts figure in the Aide Memoire was now $5,471,520.66; and

(c) the spot price for RECs had fallen from approximately $38 to $25 during the first two weeks of April, with the effect that [Solar Shop’s] assets had declined materially, as had its proceeds from ongoing trading.

55 In relation to the amount due to Bosch Solar Energy AG (Bosch), the primary judge was satisfied that Bosch’s terms required payment of a 10% deposit and payment in full of the balance within 60 days of shipment. The primary judge found that there was an uncertainty about the dates of shipment from which the 60 days commenced to run which “precluded satisfaction that the Bosch debt on which the Liquidators relied was due and payable as at 30 April 2011, although it was probable that it had become due by at least 16 May 2011”. Thus the primary judge did not consider that the Bosch debt should be taken into account in determining Solar Shop’s solvency as at 30 April 2011: at [249]-[252].

56 The primary judge considered the amount owing to the 14 trade creditors recorded in the Aide Memoire as at 30 April 2011 and noted that the Respondents disputed that the amounts shown as owing to Optimum, Fasteners, BlueScope, L&H and Matrin were due and payable as at that date. For the reasons already given in relation to 31 January 2011 his Honour was not satisfied that the amounts of $467,000, $476,000 and $229,000 were due and payable to Optimum, BlueScope and Matrin respectively. However his Honour was satisfied that the amounts of $105,000 and $276,000 were due and payable to Fasteners and L&H. Accordingly his Honour found that the trade creditors figure for 30 April 2011 in the Aide Memoire should be $2,825,155.59. The primary judge also found that the amount drawn on the overdraft should be excluded because it was not due and payable as at 30 April 2011. Thus the figure for the “Adjusted Overdraft Account Less Stated Debts” included in the Aide Memoire should be $3,787,848.01 or $3.8 million in round figures: at [257]-[259].

57 The primary judge then turned to consider whether Solar Shop had resources available to it as at 30 April 2011 to meet debts of $3.8 million. His Honour considered cash at bank, cash equivalents, trade receivables and RECs receivables, the latter of which assumed some importance to the determination of the issue.

58 In relation to the RECs receivables at [262]-[264] his Honour said:

[Solar Shop’s] balance sheet in its management accounts showed that the RECs receivable amounted to $6.369 million. It appears that this figure was based on an average price for RECs of $36 whereas at the end of April, the spot price was $26. This suggests that the value of the RECs at the end of April 2011 was not $6.369 million but $4.6 million. It also meant that [Solar Shop] could dispose of the RECs only by incurring a loss.

It is convenient to record here that the spot price of RECs continued to decline reaching a low of $19.75 on 21 June 2011 and did not return to $26 until 8 August 2011.

I will refer in relation to later months to some matters bearing upon the extent to which the RECs were readily saleable. For the present, it is sufficient to note that sale of the RECs held at 30 April 2011 would have been more than sufficient to meet the debts which were due and payable at that date.

59 The primary judge concluded that when account was taken of the trade receivables, RECs receivables and some of the cash resources, it could not be concluded that the Liquidators had proved that Solar Shop was insolvent as at 30 April 2011.

60 The final date relied on by the Liquidators was 22 May 2011, a date which was selected because that was when, on the Liquidators’ case, the Solarise Debt became due and payable.

61 The primary judge noted that he had found that the Solarise Debt did not become due and payable on 22 May 2011, because it remained subordinated to the Westpac Debt, and that the Liquidators had not provided any other analysis of the position as at 22 May 2011 that would warrant a finding that Solar Shop was otherwise insolvent as at that date. That being so, the primary judge considered the position as at 31 May 2011, for which there was some financial evidence and thus some analysis was possible.

62 The primary judge commenced his analysis of the position as at 31 May 2011 with the amounts said to be overdue as at that date to the 14 trade creditors in the Aide Memoire and which were recorded at [271] as follows:

Optimum Media (rounded) $467,000.00

Fasteners (rounded) $108,000.00

Wuxi (rounded) $1,199,000.00

BlueScope (rounded) $495,000.00

IPD Group (rounded) $263,000.00

L&H (rounded) $250,000.00

Matrin $68,875.84

Enerdrive $180,180.00

Clenergy $181,484.09

Bosch $2,444,155.59

Total $5,656,695.22

63 For the reasons already given the primary judge excluded Optimum, BlueScope and Matrin from the analysis but retained Fasteners and L&H. His Honour had already accepted that the Bosch debt was due and payable as at 22 May 2011 and thus also found that it was due and payable as at 31 May 2011.

64 That left for consideration the debts said to be due to Wuxi, IPD Group Limited (IPD Group), Enerdrive Pty Ltd (Enerdrive) and Kerry J. His Honour concluded that Solar Shop’s debt to Wuxi was due and payable on or about 26 May 2011 and that the debts due to Wuxi, Enerdrive and Kerry J were properly included in the Aide Memoire, but found that the debt due to IPD Group should be excluded.

65 As it is an issue that assumed some importance on the cross appeals, it is useful to provide some further detail of the primary judge’s findings in relation to the debt due to Wuxi. The primary judge noted that Wuxi’s trading terms were “100% T/T net 90 days from B/L date” which he understood to mean that payment was required in full within 90 days of the bill of lading date. His Honour observed that Wuxi’s invoices did not include a bill of lading date but did include an “ETD” or “estimated time of departure” date and that Solar Shop had been generally compliant with Wuxi’s terms of trade in late 2010 and early 2011: at [273]-[275].

66 The Liquidators relied on an invoice issued on 23 February 2011 for US$1,244,880 which was due and payable on or about 26 May 2011 and which was paid by Solar Shop in two equal instalments on 17 and 24 June 2011 respectively.

67 Before the primary judge SMA submitted that the payment of $1,199,000 should not be regarded as outside terms as at 31 May 2011 because Solar Shop had a payment arrangement in place with Wuxi which was evident from an email exchange between Mr Thornton and Wuxi in December 2010. However, the primary judge found that the payment plan referred to by Mr Thornton in his email was not proved in evidence. At [279]-[280] his Honour said:

I accept that this exchange evidences Wuxi’s agreement to a payment plan in respect of an amount then due to it (and probably explains the late payment of the debt due in January to which I referred earlier). However, I do not consider that the exchange can reasonably be understood as evidencing an agreed departure from Wuxi’s terms of trade in respect of its subsequent supplies. Mr Thornton’s reference to “near term” cash restraints suggests that he was seeking only some short term relaxation of Wuxi’s terms of trade, as do the reasons he gave for the request. I also note in this respect that [Solar Shop] did not conduct itself as though it had a payment plan: on the contrary, it complied with Wuxi’s usual terms of trade.

It is also pertinent to record that on 1 June 2011, Mr Thornton proposed to Wuxi that it accept the transfer of RECs “over the next 45 days at a risk adjusted discount cash flow” in exchange for a payment plan. Wuxi responded by asking for the proposed payment schedule. That exchange is inconsistent with there having been an existing payment plan. There is no evidence that [Solar Shop] and Wuxi later agreed upon a payment plan, and I reject the submission of counsel for SMA to the contrary. The best I think that can be said is that given the history, [Solar Shop] may have had some prospect of negotiating a payment plan with Wuxi, but that does not alter the circumstance that its debt to Wuxi was due and payable by on or about 26 May 2011.

68 The primary judge found that, upon excluding the amounts due to Optimum, BlueScope, Matrin and IPD, the Solarise Debt and the amount that Solar Shop had drawn down on the overdraft, the figure for the “Adjusted Overdraft Account Less Stated Debts” should be $5,887,223.63 or in round terms $5.9 million: at [293]-[294].

69 The primary judge then considered whether Solar Shop had sufficient resources available as at 31 May 2011 to meet the debts which were due and payable. His Honour noted that the RECs, which were valued in the balance sheet at $12.704 million based on an average cost of about $36.00 per REC where the average spot price as at 31 May 2011 was $25.15, could be sold but that Solar Shop would have experienced difficulty in doing so quickly. Based on Solar Shop’s sales of RECs during 2011 his Honour concluded that the RECs were liquid to an extent but that there were limitations on its ability to sell them quickly: at [307]-[310].

70 The primary judge found that as at 31 May 2011 Solar Shop had approximately $1.7 million in cash together with whatever amount could be realised from trade and other receivables and the RECs receivables to meet debts then due and payable of $5.9 million. His Honour noted that the question was not just whether Solar Shop was able to pay its debts but whether, ignoring temporary illiquidity, it was able to do so when they were due and payable. His Honour said that, while it can be accepted that there may be a distinction between a failure to pay debts when due and an inability to pay them, in this case, subject to one qualification, the distinction was not real. His Honour found that the effect of the evidence was that Solar Shop “was willing to pay its debts if only it could”. His Honour addressed the “qualification” at [314] as follows:

It is evident that [Solar Shop] was reluctant to sell the RECs when that would mean that it would incur a loss. That is understandable. I take into account therefore that its omission to sell all available RECs by 31 May should not be regarded as an inability to sell them, even if there were some limitations on their liquidity.

71 The primary judge concluded that, even taking into account the limitations on the saleability of RECs, they were sufficient to meet the debts due and payable at 31 May 2011 and that, while it was understandable Solar Shop was reluctant to sell them, the RECs were an asset which could be sold to meet its debts. Accordingly the primary judge held that the Liquidators had not proved that Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 May 2011.

Solar Shop’s solvency as at 31 July 2011

72 Having considered and rejected each of the alternatives put by the Liquidators as dates on which Solar Shop was insolvent, the primary judge considered whether Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 July 2011. This date was selected because of SMA’s contention by reference to the “report of Mr Lombe”, that Solar Shop had become insolvent by 29 July 2011 or 4 August 2011.

73 The primary judge undertook his analysis as at 31 July 2011 by reference to the Aide Memoire. His Honour excluded the debts owing to Optimum and IPD Group, the overdrawn balance on the overdraft and the Solarise account and found that the figure in the column headed “Adjusted Overdraft Account Less Stated Debts” should be $8,364,620.20 or $8.365 million (rounded).

74 In relation to the assets available as recorded in Solar Shop’s management accounts to meet that debt, the primary judge excluded the cash and cash equivalents and reduced the RECs receivables figure to $6.47 million. The price used for RECs in the balance sheet was not clear. However, his Honour assumed that it was based on an average price of $36.00 when the spot price of RECs as at 31 July 2011 was $23.00. He made a reduction to reflect that fact.

75 The primary judge noted that the adjusted RECs receivable figure and RECs receivable CBA figure (“CBA” being a reference to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia) exceeded the “Adjusted Overdraft Account Less Stated Debts”. His Honour observed that this might suggest that Solar Shop was solvent because it could have recourse to the RECs to meet the debts which were then due and payable. However, his Honour considered that other factors should be taken into account including:

(1) the limitations on the liquidity of RECs;

(2) that the management accounts for the month of July 2011 reported trade creditors totalling $20.17 million, which exceeded the total owing by the 14 trade creditors included in the Aide Memoire. His Honour found that it was realistic to infer that several of those trade creditors were outside terms;

(3) Solar Shop’s own cash flow forecast for the period 27 May 2011 to 12 August 2011 which confirmed that its cash flow problems were becoming more evident. That said the primary judge noted that he understood that the position as at 31 July 2011 was not as severe as the cash flow analysis predicted because Solar Shop had in fact sold 374,300 RECs between 26 May 2011 and 31 July 2011 and held a significant number of RECs, but there still remained a substantial cash flow deficiency as at 29 July 2011;

(4) Harbert’s pursuit of possible further investment during July and August 2011 never came to fruition. Relevantly, the primary judge found that during June and July 2011 Solar Shop had the prospect of additional funding from Harbert and Harbert was willing to participate in arrangements for further funding. However, by 31 July 2011, Harbert’s own conditions had not been satisfied. The primary judge concluded that as at 31 July 2011 funding from Harbert was not sufficiently certain such that it could be a resource to be considered in relation to Solar Shop’s solvency;

(5) on 16 June 2011 Solar Shop made a number of requests of Westpac which only acceded to one of those requests, namely an increase in its forex facility to $10 million. Westpac was prepared to continue its facility pending receipt of the Second Independent Business Review but was otherwise not prepared to provide additional facilities other than in limited ways;

(6) in the Second Ferrier Hodgson Report Ferrier Hodgson recommended that Westpac’s continued support should be subject to Harbert or other shareholders immediately injecting $5 million into the business. In addition in the First Lombe Report, Mr Lombe noted that the solvency and future trading of Solar Shop was contingent on it obtaining a cash injection of $5 million from Harbert and Westpac’s continued support and that the absence of either would be fatal to Solar Shop’s solvency; and

(7) by 31 July 2011 Solar Shop was being harried by other of its creditors.

76 The primary judge thus concluded that Solar Shop was insolvent as at 31 July 2011.

THE APPEALS AND THE DISCOVERY ISSUE

77 The appeals were initially set down for hearing for two days commencing on 6 August 2018.

78 On the first morning of the hearing SMA foreshadowed an application to adduce fresh evidence on appeal. That application concerned one document being the first two pages of an email chain included at tab 83 of part C of the appeal book and which was an email dated 10 June 2011 from Jenny Lu at Wuxi to Mr Thornton (10 June Email). The balance of the email chain which was included at tab 83 of part C of the appeal book commenced at page 3 (Tab 83 Document).

79 As the Liquidators did not consent to the inclusion of the 10 June Email in the appeal book, later that day SMA filed an interlocutory application in the appeal against it (SMA Appeal) seeking an order that at the hearing of the SMA Appeal the Court receive the 10 June Email into evidence. SMA also filed an affidavit in support sworn on 6 August 2018 by David Anthony Gordon, a solicitor in the employ of SMA’s solicitors with responsibility for the day to day conduct of the matter on behalf of SMA. Mr Gordon’s evidence included that the 10 June Email was not in evidence in the First Instance Proceedings, was not discovered in the SMA Proceeding and was not known to SMA until after 6.00 pm on 3 August 2018, the last business day before the commencement of the appeals on 6 August 2018. Mr Gordon also gave evidence about the relevance of the 10 June Email to the issues in the SMA Appeal including his opinion of the effect that the 10 June Email would have had on the findings made by the primary judge had it been available to and tendered by SMA in the SMA Proceeding.

80 On 7 August 2018 the Liquidators filed and served in each of the appeals an affidavit sworn on that day by Justin David Courtney, a consultant to the Liquidators’ solicitors with the primary conduct of the appeals on behalf of the Liquidators (First Courtney Affidavit). In that affidavit Mr Courtney explained, among other things, that:

(1) the Tab 83 Document had been discovered in the SMA Proceeding;

(2) it was only in the course of the hearing on the preceding day that it had come to his attention that SMA had not had discovery of the whole of the Tab 83 Document and was seeking to adduce the 10 June Email as fresh evidence on appeal;

(3) nearly two years later he could not specifically recall why he did not include within the tender bundle for trial or make discovery in the SMA Proceeding of the whole of the Tab 83 Document including the 10 June Email;

(4) having reviewed the discovery made in the Wuxi Proceeding, the whole of the Tab 83 Document, i.e. including the 10 June Email, was discovered in that proceeding; and

(5) in the time available he had sought out and identified a bundle of emails which were exhibited as “JDC2” to the First Courtney Affidavit and which touched on the topic the subject of the Tab 83 Document and 10 June Email but he was unable to ascertain whether that bundle of emails represented all of the documents on that topic.

81 On 7 August 2018 the appeals were adjourned part heard and orders made for the Respondents to put on any applications they wished as a result of the issues raised by the First Courtney Affidavit.

82 On 20 August 2018 SMA filed an amended interlocutory application in the SMA Appeal and Kerry J and Wuxi each filed an interlocutory application in the appeals to which they were respondents. In those applications the Respondents each relevantly sought orders that the Liquidators provide further and better discovery in accordance with orders made in the First Instance Proceedings (see [91]-[94] below) and that at the hearing of the appeals and the cross appeals the Court receive further evidence including the 10 June Email and a second email dated 27 July 2011 from Stephanie Wu to Carey Peck which was included in JDC2 to the First Courtney Affidavit (27 July Email). The Respondents each filed an affidavit in support of their respective interlocutory applications.

83 On 23 August 2018 the Liquidators filed an affidavit sworn by Mr Courtney on that date in each of the appeals (Second Courtney Affidavit).

84 On 24 August 2018 the appeals were listed before the Court. Orders were made requiring the Respondents to file and serve any further affidavits and any draft amended interlocutory applications and for the Liquidators to file and serve any further affidavits.

85 Each of the Respondents and the Liquidators filed and served further affidavits. At that point the Respondents each proposed and sought leave, which was subsequently granted, to file amended interlocutory applications. Relevantly, by way of their respective amended interlocutory applications in each of the appeals the Respondents now seek orders that:

(1) pursuant to s 25(2B)(bb) and/or s 28 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act) and/or r 36.74(a) of the Rules the appeal and cross appeal be dismissed;

(2) pursuant to s 23 and/or s 28 of the Federal Court Act and/or r 1.33 and/or r 5.23 of the Rules the First Instance Proceedings be dismissed;

(3) in the alternative to orders dismissing the appeals and cross appeals, pursuant to s 27 of the Federal Court Act, at the hearing of the appeals and/or cross appeals, the Court receive the 10 June Email and the 27 July Email; and

(4) in the alternative to orders dismissing the appeals and cross appeals and in the event that the cross appeals are not dismissed, the Respondents each be granted leave to file a further amended notice of cross appeal.

86 The draft further amended notices of cross appeal which each of the Respondents seeks leave to file relevantly:

(1) include in each case as ground 1A that the Liquidators failed to comply with the orders for discovery made in the First Instance Proceedings; and

(2) seek the following additional relief:

1A. Paragraph 1 of the orders made by the Court on 24 November 2017 be set aside and the proceeding be remitted to the primary judge for determination of the following questions, following the provision of further and better discovery by the Appellants:

a. whether an amount of $4,849,577.59 was due and payable by the Company to Wuxi Suntech as at 31 July 2011;

b. whether an amount of $2,444,155.59 was due and payable by the Company to Bosch as at 31 July 2011;

c. whether any of the Company’s inventory was available to pay debts that were due and payable;

d. such other questions as permitted by the primary judge on application by the Respondent; and

e. in light of the answer to the questions in a to d above, and otherwise in accordance with the findings made by the primary judge in the judgment delivered on 24 November 2017, whether the Appellants have proved that the Company was insolvent as at 31 July 2011.

1B. The additional evidence on the remitted hearing be limited to:

a. the evidence before the primary judge; and

b. any additional documents discovered to the Respondent by the Appellants since the conclusion of the hearing before the primary judge.

(underlining omitted.)

87 On 7 February 2019 the part heard appeals, cross appeals and each Respondent’s respective amended interlocutory application in which the orders described in [85] above are sought (collectively Interlocutory Applications) were listed before the Court for hearing.

88 The Interlocutory Applications and the Respondents’ draft further amended notices of cross appeal raise the issue of whether the discovery given by the Liquidators in the First Instance Proceedings was adequate and, if not, the consequence of any such inadequacy. In order to consider those issues it is first necessary to set out the Liquidators’ evidence on the process followed by them in providing discovery in the First Instance Proceedings. That evidence is comprised in the First Courtney Affidavit, the Second Courtney Affidavit and a further affidavit sworn by Mr Courtney on 5 October 2018 (Third Courtney Affidavit).

89 The Respondents raised a number of objections to the Second Courtney Affidavit and the Third Courtney Affidavit but subsequently withdrew their objection to [4] of the Second Courtney Affidavit and indicated that they were content for the Court to deal with the balance of their objections, which they characterised as objections to opinion evidence given by Mr Courtney, as a matter of weight.

90 Before setting out the available evidence about the discovery process and the effect of that evidence we make a general observation about the evidence relied on by the Liquidators. Once the issue of adequacy of discovery had been raised by the Respondents, the Liquidators bore the onus of establishing the steps they took to comply with the Court’s orders for discovery and satisfying the Court that they were, in the circumstances, adequate. The information relevant to that inquiry was solely within their knowledge. But, despite the attempts by the Liquidators to provide a complete picture of the steps they took in complying with the orders for discovery, they have not succeeded in that task. The Liquidators rely on the three affidavits sworn by Mr Courtney. However, notwithstanding Mr Courtney’s attempts to provide an explanation of the steps undertaken, his evidence provides an incomplete picture. Mr Courtney does not provide a full explanation of why the Liquidators proceeded as they did in relation to their treatment of some categories of documents nor does he explain why the Liquidators did not disclose to the Respondents at the time of giving discovery the sources and extent of the documents that were reviewed. Those matters are addressed below.

Discovery in the First Instance Proceedings

91 Orders for discovery were made in each of the First Instance Proceedings.

92 In the Kerry J Proceeding on 20 November 2014, the Court ordered that mutual discovery be made between the parties by 20 March 2015 and on 28 October 2015 the Court ordered the parties to file and serve supplementary disclosure lists on or before 16 November 2015.

93 In the SMA Proceeding on 21 September 2015, the Court ordered the Liquidators to provide discovery to SMA in the following categories:

1 Communications between Harbert Management Corporation (Harbert) and/or HMC Australian Private Equity Fund 1 GP, LP (HMC), and/or any entity or person associated with or acting on behalf of Harbert or HMC, and the Company between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

2 Communications between Westpac Banking Corporation (including any subsidiaries or related entities of Westpac Banking Corporation) or any person acting on its behalf and the Company and/or any persons acting on its behalf between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

3 All documents referring or relating to the possible provision of money to the Company via debt or equity created, sent or received between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

4 Communications, other than invoices and purchase orders, with suppliers to, and any other creditors of the Company between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

5 Internal communications between officers, Directors, staff or employees of the Company referring or relating to the financial position and/or insolvency and/or related issues of the Company between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

6 Minutes of, or papers for, any board meetings held by the Company between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

7 Communications, including any retainer agreements. discussion and options papers and/or advices, between the Company or any person acting on its behalf and 333 Capital Pty Ltd (trading as 333 and/or 333 Group) or any person acting on its behalf between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

8 Communications including any retainer agreements, discussion and options papers and/or advices, between the Company or any person acting on its behalf and any solicitors providing advice in relation to the financial position and/or insolvency and/or related issues, between 1 June 2011 and 30 September 2011.

94 On 12 February 2016 the Court made an order in the Wuxi Proceeding for the parties to provide “standard discovery” by 18 March 2016.

95 The Liquidators served lists of documents:

(1) in the Kerry J Proceeding on 6 May 2015, 20 November 2015 and 1 August 2016;

(2) in the SMA Proceeding on 26 October 2015; and

(3) in the Wuxi Proceeding on 18 April 2016.

96 When the tender bundle for the First Instance Proceedings was finalised the Liquidators served a supplementary list of documents in each of the First Instance Proceedings containing the documents in the tender bundle (Supplementary List of Documents).

97 The list of documents filed in the SMA Proceeding on 26 October 2015 and the Supplementary List of Documents filed in the SMA Proceeding on 1 August 2016 were in evidence before us. Each of those lists includes an affidavit sworn by Mr Clifton, one of the Liquidators, in identical terms save for the date on which the affidavit was sworn. In those affidavits Mr Clifton relevantly deposes that:

…

2. The [Liquidators] have made reasonable enquiries as to the existence and location of the documents specified in the order.