FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

SITTING AS THE COURT OF DISPUTED RETURNS PURSUANT TO SECTION 354(1) OF THE COMMONWEALTH ELECTORAL ACT 1918 (CTH).

Garbett v Liu [2019] FCAFC 241

ORDERS

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA SITTING AS THE COURT OF DISPUTED RETURNS PURSUANT TO SECTION 354(1) OF THE COMMONWEALTH ELECTORAL ACT (CTH). | |

Applicant | |

AND: | First Respondent AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 December 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to orders 2 and 3 below, the petition be dismissed.

2. Mr Simon Frost have leave to file and serve on or before 7 February 2020 any submissions as to why the Court should not direct the Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia to inform the Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia of the finding of the committal of an illegal practice under s 329(1) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by Mr Frost at least in respect of the characterisation of the corflutes as discussed in [153] in the reasons published today in order that there be compliance with s 363 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

3. On or before 7 February 2020, the parties file written submissions on costs of no more than 3 pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA SITTING AS THE COURT OF DISPUTED RETURNS PURSUANT TO SECTION 354(1) OF THE COMMONWEALTH ELECTORAL ACT (CTH). | |

VID 1019 of 2019 | |

BETWEEN: | OLIVER TENNANT YATES Applicant |

AND: | JOSHUA ANTHONY FRYDENBERG First Respondent AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION Second Respondent |

JUDGES: | ALLSOP CJ, GREENWOOD AND BESANKO JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 december 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to orders 2 and 3 below, the petition be dismissed.

2. Mr Simon Frost have leave to file and serve on or before 7 February 2020 any submissions as to why the Court should not direct the Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia to inform the Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia of the finding of the committal of an illegal practice under s 329(1) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by Mr Frost at least in respect of the characterisation of the corflutes as discussed in [153] in the reasons published today in order that there be compliance with s 363 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

3. On or before 7 February 2020, the parties file written submissions on costs of no more than 3 pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 By two petitions filed pursuant to s 353(1) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (the Act) on 31 July 2019 in the Melbourne and Sydney Registries of the High Court of Australia, Ms Naomi Leslie Hall and Mr Oliver Tennant Yates challenged the validity of the election of Ms Gladys Liu and Mr Joshua Frydenberg for the seats of Chisholm and Kooyong, respectively, at the election held in May 2019. On 18 September 2019, by orders of a Justice of the High Court, Ms Hall was replaced as petitioner by Ms Vanessa Claire Garbett and the two petitions were transferred to this Court pursuant to s 354(1) of the Act. Ms Garbett was entitled to vote in Chisholm and Mr Yates was a candidate in Kooyong. We will refer to the petitions as the Chisholm petition and the Kooyong petition.

2 Each challenge concerns signs (referred to as corflutes) placed at polling stations in both electorates that were said to be likely to mislead or deceive an elector in relation to the casting of a vote in alleged contravention of s 329(1) of the Act (set out more fully later).

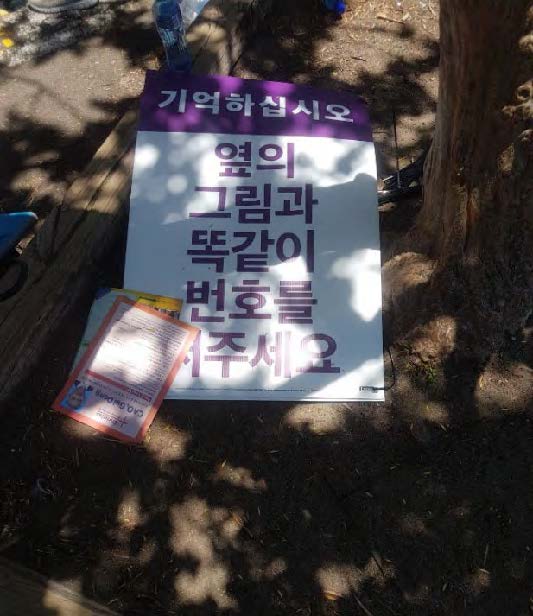

3 The corflutes were in Chinese script, both traditional and simplified. The corflutes were in purple and white colours. The purple hue was similar to the purple hue used by the Australian Electoral Commission (the AEC) in its signage at polling stations. At a number of polling places the corflute was placed near or adjacent to a sign of the AEC. Paragraph 35 of the petitions alleges that the corflutes said in translation:

Correct voting method

On the green ballot paper, put 1 next to the Liberal Party candidate

And in the other boxes, fill in the numbers in sequence, from small to big

or:

The right way to vote:

On the green ballot paper

fill in 1 next to the candidate of Liberal Party

and fill in the numbers from smallest to largest

in the rest of the boxes

or:

The correct way to vote:

Fill in 1 next to the Liberal Party candidate on the green ballot and fill in numbers from small to large successively in other boxes

4 The translation is accepted by the defences to the petitions as correct. There was no Chinese language evidence as to any nuance or range of meaning to a Chinese reader of the signs, and the matter is to be approached by reference to the English translations, with the words having the meaning, and nuance, that they have in English.

5 Each of Chisholm and Kooyong has a substantial Chinese speaking community, both Mandarin and Cantonese. We will refer to the evidence in due course, but the communities comprise people born in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

6 The essence of the complaint is that voters who saw, read and understood the signs would or may have considered them to be a direction by the AEC as to the correct way to vote, such that electors were being told that the only way to cast a correct (and so valid) vote was to vote for the Liberal Party or that the AEC was officially instructing people to vote for the Liberal Party.

7 The signs were authorised by Mr Simon Frost, the registered officer of the Liberal Party of Australia (Victoria Division) who was the Acting State Director of the Liberal Party (Victoria Division).

8 The petitioners allege that Mr Frost, Mr Frydenberg and Ms Liu committed an illegal practice by contravention of s 329(1) and seek declarations and orders that Mr Frydenberg and Ms Liu were not duly elected or that the two elections are absolutely void.

THE ACT AND THE JURISDICTION OF THE COURT

9 Part XXII of the Act provides for the existence and operation of the Court of Disputed Returns. By s 354(1), the High Court shall be the Court of Disputed Returns and shall have jurisdiction either to try the petition or refer it for trial to the Federal Court of Australia. By s 354(2), when a petition has been so referred for trial (as it was by the High Court on 18 September), the Federal Court shall have jurisdiction to try the petition and shall, in respect of the petition, be and have all the powers and functions of the Court of Disputed Returns. By s 354(6), the jurisdiction conferred by s 354 may be exercised by a single Justice (of the High Court) or by a single Judge (of the Federal Court). It is clear from the permissive use of the word “may” in s 354(6) that more than one Justice or Judge may exercise the jurisdiction. In the circumstances of the petitions and of the wider potential consequential importance of the relief sought in the petitions, the Court was constituted by the Chief Justice and two Judges of the Court.

10 By s 353(1), the only way the validity of any election or return may be disputed is by petition addressed to the Court of Disputed Returns.

11 Section 355 sets out the requisites of the petition as follows:

Subject to section 357, every petition disputing an election or return in this Part called the petition shall:

(a) set out the facts relied on to invalidate the election or return;

(aa) subject to subsection 358(2), set out those facts with sufficient particularity to identify the specific matter or matters on which the petitioner relies as justifying the grant of relief;

(b) contain a prayer asking for the relief the petitioner claims to be entitled to;

(c) be signed by a candidate at the election in dispute or by a person who was qualified to vote thereat, or, in the case of the choice or the appointment of a person to hold the place of a Senator under section 15 of the Constitution or section 44 of this Act, by a person qualified to vote at Senate elections in the relevant State or Territory at the date of the choice or appointment;

(d) be attested by 2 witnesses whose occupations and addresses are stated;

(e) be filed in the Registry of the High Court within 40 days after:

(i) if the polling day for the election in dispute is not the polling day for any other election—the return of the writ for the election; or

(ii) if the polling day for the election in dispute is also the polling day for another election or other elections—the return of whichever of the writs for the election in dispute and that other election or those other elections is returned last; or

(iii) if the choice or the appointment of a person to hold the place of a Senator under section 15 of the Constitution is in dispute—the notification of that choice or appointment.

12 Section 356 provides for the deposit when filing the petition of $500 as security for costs.

13 Section 357 provides for a petition disputing an election to be filed by the AEC.

14 By s 358, no proceedings shall be had on the petition unless the requirements of ss 355, 356 and 357 are complied with. Some flexibility is given to the factual foundation of the grounds of the petition (see paras 355(a) and (aa)) by s 358(2) which is as follows:

The Court may, at any time after the filing of a petition and on such terms (if any) as it thinks fit, relieve the petitioner wholly or in part from compliance with paragraph 355(aa).

By s 358(3), the Court may not act under sub-s (2) unless it is satisfied that:

(a) in spite of the failure of the petition to comply with paragraph 355(aa), the petition sufficiently identifies the specific matters on which the petitioner relies; and

(b) the grant of relief would not unreasonably prejudice the interests of another party to the petition.

15 By s 359, the AEC is entitled by leave of the Court to enter an appearance, be heard on the petition, and by such, to be a respondent. This occurred in both petitions pursuant to leave granted on 18 September by a Justice of the High Court.

16 The powers of the Court of Disputed Returns are provided for by s 360:

(1) The Court of Disputed Returns shall sit as an open Court and its powers shall include the following:

(i) To adjourn;

(ii) To compel the attendance of witnesses and the production of documents;

(iii) To grant to any party to a petition leave to inspect in the presence of a prescribed officer the rolls and other documents (except ballot papers) used at or in connexion with any election and to take, in the presence of the prescribed officer, extracts from those rolls and documents;

(iv) To examine witnesses on oath;

(v) To declare that any person who was returned as elected was not duly elected;

(vi) To declare any candidate duly elected who was not returned as elected;

(vii) To declare any election absolutely void;

(viii) To dismiss or uphold the petition in whole or in part;

(ix) To award costs;

(x) To punish any contempt of its authority by fine or imprisonment.

(2) The Court may exercise all or any of its powers under this section on such grounds as the Court in its discretion thinks just and sufficient.

(3) Without limiting the powers conferred by this section, it is hereby declared that the power of the Court to declare that any person who was returned as elected was not duly elected, or to declare an election absolutely void, may be exercised on the ground that illegal practices were committed in connexion with the election.

(4) The power of the Court of Disputed Returns under paragraph (1)(ix) to award costs includes the power to order costs to be paid by the Commonwealth where the Court considers it appropriate to do so.

17 Section 362 concerns the declaring void of elections for illegal practices. By s 352(1), the phrase “illegal practice” is defined as meaning a contravention of the Act or of the regulations. In this case, the alleged contraventions concern s 329. Section 352(1) also defines “bribery”, “corruption” and “undue influence” as meaning a contravention of s 326 (as to bribery or corruption) and a contravention of s 327 or s 83.4 of the Criminal Code (as to undue influence). Section 362 is in the following terms:

(1) If the Court of Disputed Returns finds that a successful candidate has committed or has attempted to commit bribery or undue influence, the election of the candidate shall be declared void.

(2) No finding by the Court of Disputed Returns shall bar or prejudice any prosecution for any illegal practice.

(3) The Court of Disputed Returns shall not declare that any person returned as elected was not duly elected, or declare any election void:

(a) on the ground of any illegal practice committed by any person other than the candidate and without the knowledge or authority of the candidate; or

(b) on the ground of any illegal practice other than bribery or corruption or attempted bribery or corruption;

unless the Court is satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected, and that it is just that the candidate should be declared not to be duly elected or that the election should be declared void.

(4) The Court of Disputed Returns must not declare that any person returned as elected was not duly elected, or declare any election void, on the ground that someone has contravened the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 or the Radiocommunications Act 1992.

18 Section 365 dealing with “immaterial errors” is in the following terms:

No election shall be avoided on account of any delay in the declaration of nominations, the provision of certified lists of voters to candidates, the polling, or the return of the writ, or on account of the absence or error of or omission by any officer which did not affect the result of the election:

Provided that where any elector was, on account of the absence or error of, or omission by, any officer, prevented from voting in any election, the Court shall not, for the purpose of determining whether the absence or error of, or omission by, the officer did or did not affect the result of the election, admit any evidence of the way in which the elector intended to vote in the election.

19 No party submitted to the contrary of the proposition expressed by Gaudron J in Hudson v Lee (1993) 115 ALR 343 at 345; 67 ALJR 720 at 722 that s 362 provides exhaustively as to the general grounds on which an election may be invalidated or declared void, albeit subject to the different question of qualification: Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30; 199 CLR 462 at 511 [121] (Gaudron J).

20 The distinction between bribery and undue influence, on one hand, and any other illegal practice on the other, is drawn by sub-ss 362(1) and (3). The full subtleties of the operation of these two sub-sections, for instance if bribery or undue influence occurred with the knowledge but not authority of a candidate, need not be explored. It is sufficient to recognise that for present purposes, the Court must not declare that Ms Liu or Mr Frydenberg was not duly elected nor declare the two elections (or either of them) void unless the Court is satisfied that the results or result of the elections or election were or was likely to be affected and that it is just that she or he should be declared not to be duly elected or the election (in respect of her or him) should be declared void.

21 By s 363, if the Court of Disputed Returns finds that any person has committed an illegal practice, that is to be reported to the Minister.

22 By s 363A, the Court of Disputed Returns must make its decision on a petition as quickly as is reasonable in the circumstances.

23 The nature of the jurisdiction is also illuminated in ss 364 and 368:

364 Real justice to be observed

The Court shall be guided by the substantial merits and good conscience of each case without regard to legal forms or technicalities, or whether the evidence before it is in accordance with the law of evidence or not.

368 Decisions to be final

All decisions of the Court shall be final and conclusive and without appeal, and shall not be questioned in any way.

24 Section 368 is subject to the operation of s 75(v) of the Constitution.

25 Part XXI of the Act (ss 322 to 351) deals with electoral offences. Section 329 is in the following terms:

(1) A person shall not, during the relevant period in relation to an election under this Act, print, publish or distribute, or cause, permit or authorize to be printed, published or distributed, any matter or thing that is likely to mislead or deceive an elector in relation to the casting of a vote.

(4) A person who contravenes subsection (1) commits an offence punishable on conviction:

(a) if the offender is a natural person—by imprisonment for a period not exceeding 6 months or a fine not exceeding 10 penalty units, or both; or

(b) if the offender is a body corporate—by a fine not exceeding 50 penalty units.

(5) In a prosecution of a person for an offence against subsection (4) by virtue of a contravention of subsection (1), it is a defence if the person proves that he or she did not know, and could not reasonably be expected to have known, that the matter or thing was likely to mislead an elector in relation to the casting of a vote.

Note: A defendant bears a legal burden in relation to the defence in subsection (5) (see section 13.4 of the Criminal Code).

(5A) Section 15.2 of the Criminal Code (extended geographical jurisdiction—category B) applies to an offence against subsection (4).

(6) In this section, publish includes publish by radio, television, internet or telephone.

The petitions and the issues

26 Before descending to the detail of the petitions and the evidence, the structure of the issues derived from the Act and the petitions should be expressed, and important questions of construction of the Act resolved.

27 The Court has power to declare that either or both Ms Liu and Mr Frydenberg was or were not duly elected or that her, his or their election or elections was or were absolutely void. That power is engaged if any person committed an illegal practice. There will have been an illegal practice committed, relevantly here, if a person printed, published or distributed, or caused, permitted or authorised to be printed, published or distributed any matter or thing (being here, the corflute) that was likely to mislead or deceive an elector in relation to the casting of a vote. Even if the answer to that question be in the affirmative, the power can only be exercised if the Court is satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected and that it is just to exercise the power.

28 So, the broad issues are (1) Were the corflutes likely to mislead or deceive an elector in relation to the casting of a vote? (2) Was anyone, and if so who, responsible for that, in the language of s 329(1): printing, publishing or distributing or causing, permitting or authorising the printing, publishing or distributing of the corflute? (3) Was the result of the election likely to be affected? and (4) Is it just to order the relief sought, if otherwise available?

29 These questions are partly factual questions. There are, however, matters of the meaning of relevant provisions that bear importantly upon the resolution of the petitions.

The questions of statutory construction

30 We will commence by a discussion of the main issues of construction thrown up, principally by reference to the matters raised by the parties, and then by reference to the enactment histories of the relevant sections.

Section 329(1): “in relation to the casting of a vote”

31 Section 329(1) has a field of operation constrained by the phrase “in relation to the casting of a vote”. The provision is not concerned with a matter or thing which is misleading or deceptive and which might influence an elector in forming a judgment or making a decision as to the candidate or party for whom, or in favour of which, to vote. It is concerned with the casting of the vote. The distinction and the limitation of the prepositional phrase “in relation to the casting of the vote” were explained in Evans v Crichton-Browne (1981) 147 CLR 169. There, in relation to a predecessor provision to s 329 (paras 161(d) and (e)), the petitioners claimed that advertising had been untrue or incorrect. The issue before the High Court on stated cases was expressed by the Court at 147 CLR 201 as follows:

In each case the respondents contend that even if statements of this kind were made, and were untrue or incorrect, they were not statements of the kind to which s. 161 (e) refers. It is apparent that the statements relied on by all the petitioners were intended, and may have been likely, to influence an elector in forming his judgment, and making his decision, as to the candidate for whom, or the political party in favor of which, he would cast his vote. The respondents however submit that s 161(e) does not apply to statements of that kind; the application of that paragraph is limited, they say, to untrue or incorrect statements intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with an elector in or in relation to acts which he must perform in order to record his vote in accordance with the decision he has made or makes at the time. The question is, does s 161(e) refer to statements intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with an elector in or in relation to his choice of the candidate or candidates for whom he will vote, or does it refer only to statements intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with an elector in such a way that his choice when made is not properly expressed or given effect by the physical act of voting?

(Emphasis added.)

32 Section 161 was relevantly as follows:

In addition to bribery and undue influence the following shall be illegal practices:

…

(d) Printing, publishing, or distributing any electoral advertisement, notice, handbill, pamphlet, or card containing any representation of a ballot-paper or any representation apparently intended to represent a ballot-paper, and having thereon any directions intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote:

(e) Printing, publishing, or distributing any electoral advertisement, notice, handbill, pamphlet, or card containing any untrue or incorrect statement intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote:

…

Provided that nothing in paragraphs (d) and (e) of this section shall prevent the printing, publishing, or distributing of any card, not otherwise illegal, which contains instructions how to vote for any particular candidate, so long as those instructions are not intended or likely to mislead any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote.

33 The Court drew the clear distinction (at 147 CLR 204) between casting a vote and deciding for whom to vote. At 204-205, the Court said the following:

The use of this phrase in s 161(e) suggests that the Parliament is concerned with misleading or incorrect statements which are intended or likely to affect an elector when he seeks to record and give effect to the judgment which he has formed as to the candidate for whom he intends to vote, rather than with statements which might affect the formation of that judgment. Certainly par (d) of s 161 is concerned only with a particular instance of a misleading or incorrect statement of that kind, namely a statement contained in a document representing, or apparently intended to represent, a ballot-paper. For example, a document in the form of a ballot-paper, which contained directions that a ballot-paper must be marked in a manner different from that provided by the Act, or in a manner that would favour a particular candidate, would, if the other conditions were satisfied, fall within the prohibition of s 161(d). It seems reasonable to conclude that s 161(e) was intended to deal with misleading or incorrect statements of a similar kind, even though not contained in a representation of a ballot-paper. For example, a statement contained in a newspaper advertisement that a ballot-paper should be marked in a way that would not conform to the requirements of the Act and which would render the vote invalid might mislead or improperly interfere with an elector in the casting of his vote. The same might be true of a statement that a person who wished to support a particular party should vote for a particular candidate, when that candidate in fact belonged to a rival party. An erroneous statement as to the hours or place of polling which had the result that an elector (perhaps in a remote country district) failed to get to a polling booth in time to vote would have misled that elector in relation to the casting of his vote, although it would not have misled him in casting his vote, since in the case imagined no vote was cast. The insertion of the proviso to s 161 at the same time as pars (d) and (e) confirms the construction suggested.

(Emphasis added.)

34 The distinction was further explained at 147 CLR 207-208, as follows:

With all respect to the arguments presented on behalf of the petitioners, we can see nothing in the context provided by the Act as a whole, or in the general considerations of policy upon which the petitioners relied, which warrants a departure from the natural meaning of the words of par. (e), which, we hold, refer to the act of recording or expressing the political judgment which the elector has made rather than to the formation of that judgment. It would no doubt be too narrow to regard the casting of the vote as the mere act of putting the paper in the ballot-box the words would appear to refer to the whole process of obtaining and marking the paper and depositing it in the ballotbox. However, the words clearly do not refer to the whole conduct of the election, which begins before and ends after the votes are cast.

(Emphasis added.)

35 That distinction has been recognised consistently as applicable in the context of s 329: Webster v Deahm (1993) 116 ALR 223 at 227-228; 67 ALJR 781 at 784; Peebles v Burke [2010] FCA 838; 216 FCR 387 at 390 [10]; and Faulkner v Elliot [2010] FCA 884; 188 FCR 373 at 375-377 [13]-[15].

36 The application of that distinction to the facts here may not be self-evident, but in our view is ultimately clear. The distinction is one between the formation of the political or voting judgment of the elector, and its recording or expression. As shall be seen below in discussing the terms of the petitions and the evidence (see in particular [144], [152] and [153] below), the petitioners seek to fall within the purview of the provision by focusing on what they say was the misleading statement that the only way to cast or record a valid vote was to vote for the Liberal Party or that the official instruction of the AEC was to cast or record a vote for the Liberal Party. Each of these ways of putting the case may be seen not to be a complaint about the formation of any political or voting judgment by the elector, but about directing electors in a misleading way as to how to cast their votes. As will be seen in the discussion of the history of the forerunners to s 329(1), this kind of misrepresentation was described in 1911 in Parliament (correctly in our view) as “palpable” (see [77] below), and directed to the casting of the vote.

Section 329(1): “likely to mislead or deceive”

37 The constraining effect of the phrase “in relation to the casting of a vote” is relevant to the meaning of the whole provision. The meaning of “likely to mislead or deceive” is to be taken from the whole section, its place in the Act and from the enactment and re-enactment history, and the wider context of that. Relevant to the approach of the Court in Crichton-Browne was the necessity for robust, free and uninhibited debate in the political sphere. It is a large step (although it was briefly taken in 1983 for one year: see [89] below) to constrain political discourse and argumentation by prohibiting misleading statements or conduct in that discourse. That step was taken in trade and commerce. But the field of contest in politics is broader and more apt to a width of debate where differences of views as to what is misleading or deceptive, in particular among political partisans or between opponents, may move into questions that are scarcely justiciable: cf the point made in argument by Mr Gleeson QC in Crichton-Browne 147 CLR at 197. The protection of the casting of the vote, however, is the protection of the expression or recording of the political judgment of the elector. Such can be seen as of great importance: Smith v Oldham (1912) 15 CLR 355 at 362. This distinction and the importance of the protection of the expression of choice of the elector tends in favour of the proposition that the word “likely” in s 329(1) is not limited to what is more probable than not.

38 There is authority for the proposition that “likely” in s 329(1) does not mean a mere possibility. In Goss v Swan [1994] 1 Qd R 40 at 41, in an extempore judgment, Derrington J said:

Moreover, as the provision says, there must be a likelihood of misleading, not a mere possibility of it.

39 In Minnikin v Chrisholm [2015] QSC 18 at [11], Daubney J, in an extempore judgment, followed Goss v Swan.

40 It does not follow from these cases, however, that “likely” means “more probable than not”, or “proved on the balance of probabilities”. Section 329 was introduced in its current form by the Commonwealth Electoral Legislation Amendment Act 1983 (Cth). By that time, this phrase had been construed at an appellate level under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) as meaning a “real or not remote chance or possibility [of misleading or deceiving] regardless of whether it is less or more than fifty per cent.” See Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87, applying Deane J in Tillmanns Butcheries Pty Ltd v Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union (1979) 42 FLR 331 at 346. In another context of personal injury, the High Court construed “likelihood of injury” in the same way: Sheen v Fields Pty Ltd (1983) 58 ALJR 93 at 95 and 96. Chief Justice Bowen was a member of the bench in Global Sportsman. He also sat on Tillmanns Butcheries. In that earlier case, in dealing with the word “likely” in the Trade Practices Act, Bowen CJ recognised the variety of meanings such a word can carry: more probable than not, a material risk such as might happen, inherent likelihood, and some possibility. At 42 FLR 340, Bowen CJ noted that the circumstances to which the provision (s 45D of the Trade Practices Act) apply are so various as to create a hesitation in him:

…to place a gloss on the section by preferring one meaning of “likely” rather than another for the determination of this particular case.

41 In that passage Bowen CJ was recognising how the facts of the particular case may inform the application of the phrase. Nevertheless some clarity of content of meaning is necessary to be given. The section is dealing with what might mislead or deceive in casting a vote. This is not merely cause to wonder about a circumstance or create confusion about a choice, but mislead or deceive in relation to an act, that is, the casting of the vote. It is the vote of “an elector”. In the light of those words, we do not find the cases concerned with the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the public in trade practices cases concerned with consumer protection of great assistance. In Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at 84-85, the Court discussed the appropriate level of abstraction to approach deception of the public. The attribution of characteristics necessary in a consumer context was recognised by the Court to be affected, as Gibbs CJ had pointed out in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199, by the fact that legislation that could impose burdens on someone even if he, she or it acted honestly and reasonably should not be construed as operating for the benefit of people who failed to take reasonable care of their own interests. The very different statutory context here is the protection of the casting of the vote of electors expressed by reference to what is likely to mislead or deceive an elector. That singularity in expression (“an elector”) tends against any broad limitation to the ordinary or reasonable elector, without any possible naïvety or gullibility and of ordinary intelligence. It may be the naïve or gullible to whom the misleading matter is directed. Elections can be won and lost by one vote; every vote (however gained) may count. The enactment history of s 329(1) (and s 362) discussed in detail below (and to which the Court was not referred in any detail by any party) also makes clear that the recent enactment of the Trade Practices Act before 1983 is of marginal relevance to understanding the meaning of the word “likely” when used in ss 329(1) and 362(3), and in their forerunner provisions.

42 Nevertheless, some degree of reasonableness may well attend the assessment of whether a matter or thing is likely to mislead or deceive: Liberal Party of Australia (Victorian Division) v Rae [2019] VSCA 13 at [16]. What is to be judged likely to be misleading or deceptive is any matter or thing which can be printed, published or distributed. Thus, it is some communication about, or in relation to, casting a vote that can be objectively assessed. What makes it likely misleading or deceptive to an elector may be derived from the context of the communication, or its content, or the apparent target or aim of the communication. The protection of the casting of the vote of an elector is achieved by asking oneself whether it is likely that an elector would be misled or deceived in some way in relation to the casting of her or his vote. Whether that likelihood should be asked of the gullible or naïve or ordinary elector in part depends upon the circumstances. In the ordinary course, if a reasonable person would read and understand material in a way that is not misleading, that will probably be the end of the matter. That it is possible that someone with some particular vulnerability would read and understand it in a way that could be said to be misleading may not suffice to characterise the matter or thing as likely to mislead or deceive an elector. If, however, it is likely that people with a certain vulnerability will read and understand material in a way that is misleading, that may suffice to characterise the matter or thing as likely to mislead or deceive an elector. The answer to that question of characterisation may be more easily arrived at if it can be shown that the matter or thing was aimed at electors with that particular vulnerability. Much will depend on context and the particular circumstances.

43 A construction of s 329 that something is likely to mislead or deceive an elector if there is a real chance that an elector will be misled or deceived is apt to protect the core of the electoral process at the heart of a democratic society – the casting of the vote by individual electors, not as ordinary or reasonable consumers in trade and commerce taken to look after their own personal interests, but as citizens not to be tricked in relation to how they cast their votes. This gives full recognition to the real life hurly-burly of political discourse and engagement, but full protection to the conclusory casting of the vote after the hurly-burly has dimmed outside. This construction accords with the enactment history of s 329(1) and its forerunners. It also underpins and does not impede the freedom of political communication.

Section 362(3): “the result of the election was likely to be affected”

44 Whilst s 329(1) acts to protect the individual elector in the casting of his or her vote, s 362(3) protects the integrity of the will of electors generally where bribery or undue influence (whether actual or attempted) do not compromise the election. Thus the will of the majority is to be respected unless the Court is satisfied that the result of the election was “likely to be affected”. The “result of the election” is the return of the particular candidate who is elected, not the margin or margins between candidates: Australian Electoral Commission v Johnston [2014] HCA 5; 251 CLR 463 at 485 [56]; Kean v Kerby (1920) 27 CLR 449 at 458.

45 The protection of the casting of the vote is achieved not only by the proscription of the conduct in s 329(1) but also by the deterrence involved in making it a criminal offence. However, the step of setting aside the collective choice of the electorate is only to occur if that choice has likely been brought about by the misleading or deceptive matter or thing.

46 Once again the word “likely” or the phrase “likely to” must be construed. On one view, the democratic process can be seen as better vindicated (where there is no bribery or undue influence) by not declaring a candidate not duly elected or by not declaring an election void unless the court is satisfied that it is probable, that is more probable than not, that the result of the election was affected. Setting aside the apparent will of the majority is no light matter. However, as will be seen, that appropriate caution may be seen to be well vindicated by a less definite or stringent requirement, especially in the light of the impossibilities of proof of the effects or consequences of some illegal practices. This is especially so if what is considered to be a “real chance” is informed by the recognition of the need for deep respect for the franchise, the electoral process, and the role of the AEC.

47 In Kean v Kerby 27 CLR at 455, Isaacs J said that the Act should be construed “as a whole, and in favour of the franchise…”. The primary role of a court of disputed returns is to protect the integrity of the franchise: Australian Electoral Commission v Towney (1994) 51 FCR 250 at 255.

48 It is clear from these considerations, the ordinary meaning of the word “likely”, and the various authorities that the possibility of the result being different is not sufficient: Wasaga v Tahal (1991) 33 FCR 438 at 448; Australian Electoral Commission v Lalara (1994) 53 FCR 156 at 165-166; Shaw v Wolf (1998) 83 FCR 113 at 134-135; Kelly v Campbell [2002] FCA 1125 at [20]-[21]; Green v Bradbury [2011] FCA 71; 191 FCR 417 at 428 [53]; Scott-Irving v Oakeshott [2009] FCA 487; 256 ALR 442 at 451 [40]. Whilst these cases are unanimous that a higher requirement than possibility is encompassed within “likely”, they are not unanimous as to whether “likely to be affected” means more probable than not (Wasaga v Tahal and Shaw v Wolf) or something less, such as a real chance in the Tillmanns Butcheries sense (AEC v Lalara, Kelly v Campbell, Green v Bradbury and Scott-Irving v Oakeshott).

49 In the cases other than Wasaga v Tahal and Shaw v Wolf, the decision as to the meaning was not determinative: In Lalara the result was overwhelming – 95% of votes were improperly rejected. In Kelly v Campbell, Green v Bradbury and Scott-Irving v Oakeshott the petitions were summarily dismissed. That consideration weighs in favour of Wasaga v Tahal and Shaw v Wolf. However, the reasoning of Spender J in Wasaga v Tahal was heavily dependent upon cases in which the legislation was more definitive than the language in s 362(3). He first referred to Re Vehicle Builders Employees’ Federation of Australia (SA Branch) (1987) 13 FCR 350 at 353 in which Keely J dealt with an election under the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth). The relevant section (s 165(4)) provided that a prerequisite to the making of a declaration that an election is void was that the Court form an opinion that, due to irregularity, “the result…may have been affected.” These words were contrasted by Keely J with s 185 of the Electoral Act 1929 (SA) considered in Crafter v Webster (No 2) (1980) 23 SASR 321: no “election shall be declared void on account of any…error…which is not proved to have affected the result of the election” (emphasis added by Keely J); and with the then s 194 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 considered in Kean v Kerby, that “No election shall be avoided…on account of the…error of any officer which shall not be proved to have affected the result of the election” (emphasis added by Keely J). Justice Spender also referred to Bridge v Bowen (1916) 21 CLR 582 which concerned s 56 of the Sydney Corporation Act 1902 (NSW) which provided that if it appeared that an alderman was “unduly elected” the Court may order that he be ousted from office. The circumstances in Bridge v Bowen were that 13 persons who were not qualified to vote personated others in order to vote. The second and third candidates (the second being elected, the third not) were divided by less than 13 votes. By majority, the High Court overturned the Supreme Court and refused to interfere with the election. What had to be shown, it was held, was the fact of undue election. In stinging remarks upon the making of the orders, Griffith CJ (in dissent, with Barton J) said at 635:

As a majority of the Bench are of a different opinion from that taken by my brother Barton and myself, the appeal will be allowed. But I think it my duty to invite public attention to the state of the law as now laid down. It is this : In elections conducted by ballot when there is no means of identifying the votes given by individual voters, a vote given by a successful personator is, at common law, unless otherwise expressly declared by Statute, as effective as a vote given by a genuine elector. It follows that when it is shown that personators sufficient in number to turn the scale have succeeded in voting the election is, nevertheless, valid, and cannot be set aside.

This decision governs elections to the Federal Parliament and to most of the State Parliaments, as well as municipal elections. But, although I am bound to accept it as correctly declaring the law until it is overruled or the law is altered by Statute, I cannot believe that it expresses the deliberate will of the Parliament or the people of the Commonwealth.

50 As will be seen below, when Bridge v Bowen was used in relation to the Act in Kean v Kerby, the Parliament sought to repair the position to something less definite and in accord with the common law of elections, favoured by Griffith CJ and Barton J in Bridge v Bowen, albeit in connection with the forerunner of s 365, not of s 362(3).

51 The distinction made by Merkel J in Shaw v Wolf was between “might” and “likely” in the following paragraph at 83 FCR 134-135:

The election involved a relatively small number of votes (952) for a relatively large number of candidates (34) for 12 elected positons. The evidence does not suggest that the removal of candidates such as Mr Lesage and Ms Oakford is likely to have an effect on the election of other candidates. Mr Lesage’s preferences were distributed in any event. The probable effect of the removal of candidates depends on numerous factors including the number of votes for the candidates removed, whether they are removed at the same time, the quota, first preference votes received by various candidates and the flow of preferences. The illegal practices in the present case might have affected the election but I am unable to conclude that it is likely that they did so.

In this context, the contradistinction of “might” and “likelihood” is not necessarily to be understood as the same as the contradistinction of “real chance” and “more probable than not”.

The text and enactment history of the relevant legislative provisions

52 More assistance is gained by an examination of the text of the legislation and the relevant enactment history.

53 If a finding of a court or its opinion or satisfaction is the subject of a provision it may be taken that, unless the statute reveals to the contrary, that fact, opinion or satisfaction will be reached to the requisite standard of proof, whether on the balance of probabilities or some higher standard, and affected or not by considerations such as in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336.

54 So, if a statute provides that an election is not to be declared void unless something has been “proved to have affected the result of the election” or not to be declared void on account of something which “did not affect the result of the election”, it might be thought that such a provision provides (good contextual reason aside) for proof on the balance of probabilities of the affectation of the result. This was the reasoning of Isaacs J in Kean v Kerby in 1920 in respect of s 194 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the forerunner of s 365) which employed the first of the above phrases. This was also the reasoning of Isaacs J earlier in 1916 in Bridge v Bowen where similar language was used that “it appeared to the Court that the person was unduly elected” (emphasis added). Section 365 employs the second of the above phrases and (subject to consideration of the amending enactment history after the handing down of Kean v Kerby discussed at [82]-[86] below) might be seen to require the Court to find a state of facts or state of affairs: the “error [etc] which did not affect [or did affect] the result of the election”. This language is different to that in s 362(3) which speaks of the Court being satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected. The drafter did not, perhaps, need to insert the word “likely” before the phrase “to be affected” to convey the need for proof on the balance of probabilities that the election “was affected”. The phrase “likely to be affected” can be seen as different and conveying something less definite than the proof of a fact or state of affairs.

55 The meaning of “the result of the election was likely to be affected” and the understanding that it is different from, and something less definite than, proof of the fact that the election was affected is assisted by an examination of the enactment history not only of s 365, but also of ss 329 and 362.

56 The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (as enacted) (the 1902 Act) provided in Pt XV for Electoral Offences. By s 173, the following acts were prohibited and penalised to “secure the due execution of this Act and the purity of elections”:

(a) Breach or neglect of official duty

(b) Illegal practices, including –

(a) Bribery

(b) Undue influence

(c) Electoral offences.

57 Sections 174 to 179 defined and criminalised the acts in (i) and (ii) (a) and (b).

58 Section 180 in its original form identified three other matters, in addition to bribery and undue influence, to be illegal practices, being:

(a) Any publication of any electoral advertisement, hand-bill or pamphlet or any issue of any electoral notice without at the end thereof the name and address of the person authorizing the same, and on the face of the notice the name and address of the person authorizing the notice;

(b) Printing or publishing any printed electoral advertisement hand-bill or pamphlet (other than an advertisement in a newspaper) without the name and place of business of the printer being printed at the foot of it;

(c) Any contravention by a candidate of the provisions of Part XIV, of this Act relating to the Limitation of Electoral Expenses.

59 Section 181 provided for criminal punishment of any illegal practice.

60 Section 182 provided for further electoral offences and their punishments in a table. These included falsely personating someone to secure a ballot paper, fraudulently taking a ballot paper out of a polling booth and interfering with ballot boxes, and voting more than once.

61 Part XVI (ss 192-206) provided for the Court of Disputed Returns. Section 197 (the forerunner of s 360(1)) set out the powers of the Court. Section 199 was in similar terms to the present s 364. Section 200, with the sidenote “Immaterial errors not to vitiate election”, was in the following form:

No election shall be avoided on account of any delay in the declaration of nominations, the polling, or the return of the writ, or on account of the absence or error of any officer which shall not be proved to have affected the result of the election.

62 There was no provision expressly directed to how the Court should deal with, or any constraints on it in dealing with, the various illegal practices, including bribery, undue influence and electoral offences, in exercising its powers in s 197, including the powers in s 197(iv) and (vi) to declare someone not duly elected or any election absolutely void.

63 Chanter v Blackwood (1904) 1 CLR 39 (Chanter (No 1)) and Chanter v Blackwood (1904) 1 CLR 121 (Chanter (No 2)) concerned the election for the House of Representatives for the Division of Riverina in December 1903. There were two candidates. The elected candidate won by five votes (out of 8,677 formal votes). The dispute concerned the informality or formality of certain marked ballot papers. Three questions were stated that were the subject of Chanter (No 1). The first two concerned the mandatory or directory character of provisions of the 1902 Act dealing with marking the ballot paper. The third was whether the Court had jurisdiction, and if so what, with respect to illegal practices. The context of this issue being raised was explained by the Chief Justice at 1 CLR 56-57:

The third question raised by this petition is, whether the High Court has any and what jurisdiction with respect to illegal practices. I am afraid I am responsible for putting the question in that form, and it does not exactly raise the question I desired to be decided. This Court has clearly jurisdiction to administer the law, whatever the law is, and, if the law is that a candidate who is guilty of an illegal practice is not duly elected, this Court has clearly jurisdiction to say so. The real question is whether, by the law applicable to elections for the House of Representatives, a candidate guilty of an illegal practice as defined by the Electoral Act is disqualified from being elected. Sir John Quick expressly disclaimed any intention to set up that the respondent was liable to lose his seat under what is called the Common Law of Parliament, that is the Common Law relating to the House of Commons. It is said that by the Common Law of England relating to the House of Commons (I do not quite understand the expression) a candidate guilty of bribery at Common Law forfeited his seat. Whether that law is part of the Common Law of Australia or not is a question which I should be very sorry to decide without much fuller argument than has been possible on this occasion. I say this because there are very weighty authorities to the effect that Parliamentary law is not introduced into the colonies, and therefore not into the Commonwealth. I refer to the opinion of Sir A. Cockburn, A.G., and Sir R. Bethell, S.G., (Feb. 15, 1856, quoted in Forsyth’s Cases and Opinions on Constitutional Law, at p. 25), and the decision of the Privy Council in Kielly v Carson, (1843) 4 Moo. P.C., 84. We are fortunately relieved from the necessity of determining that point. All we have to decide is whether, under the provisions of the Statute Law before us, a candidate is incapable of election if he has committed one of the acts prohibited by the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

64 The Chief Justice first dealt (at 57-58) with the question whether, in circumstances of certain acts being criminal offences and where Parliament has omitted from the Act any express power in the Court to declare that such any act such had been committed by a candidate and to empower the Court to deprive him of his seat if he had, the Court had power to do either. At 1 CLR 58, Griffith CJ said:

So that we find [referring to Colonial and State legislation] a uniform course of legislation all to the same effect, by which the conditions under which a candidate can become incapable of election, were expressly laid down, and when power was intended to be given to the Committee of Elections and Qualifications or other tribunal to determine the question, it was expressly conferred. Then we find the Commonwealth Parliament in this Electoral Act deliberately omitting any such provision. In these circumstance, I do not think that it can be inferred that this Court has power to declare that a candidate is guilty of an electoral offence, or to declare that, if he has been so guilty, he shall forfeit his seat.

65 The Chief Justice then (at 1 CLR 58-59) quoted at length Lord Coleridge CJ in Woodward v Sarsons (1875) LR 10 CP 733 at 743-744 on the common law of elections. The passage should be quoted in full because it commended itself to the Chief Justice and Barton J (at 1 CLR 64). It was cited and was the subject of discussion because there was real doubt expressed by the Court whether it had any power to interfere with an election even if most serious illegal practices had taken place. Lord Coleridge CJ said:

As to the first point, we are of opinion that the true statement is that an election is to be declared void by the Common Law applicable to parliamentary elections, if it was so conducted that the tribunal which is asked to avoid it is satisfied, as matter of fact, either that there was no real electing at all, or that the election was not really conducted under the subsisting election laws. As to the first, the tribunal should be so satisfied, i.e., that there was no real electing by the constituency at all, if it were proved to its satisfaction that the constituency had not in fact had a fair and free opportunity of electing the candidate which the majority might prefer. This would certainly be so, if a majority of the electors were proved to have been prevented from recording their votes effectively according to their own preference, by general corruption or general intimidation, or to be prevented from voting by want of the machinery necessary for so voting, as by polling stations being demolished, or not open, or by other of the means of voting according to law not being supplied, or supplied with such errors as to render the voting by means of them void, or by fraudulent counting of votes or false declarations of numbers by a Returning Officer, or by other such acts or mishaps. And we think the same result should follow if, by reason of any such or similar mishaps, the tribunal, without being able to say that a majority had been prevented, should be satisfied that there was reasonable ground to believe that a majority of the electors may have been prevented from electing the candidate they preferred. But, if the tribunal should only be satisfied that certain of such mishaps had occurred, but should not be satisfied either that a majority had been, or that there was reasonable ground to believe that a majority might have been, prevented from electing the candidate they preferred, then we think that the existence of such mishaps would not entitle the tribunal to declare the election void by the Common Law of Parliament.

(Emphasis added.)

66 In the reasons of Barton J at 1 CLR 64-65 there is recorded a different view of Willes J as to the effect of bribery:

It may be that the Common Law as stated on the high authority of Mr. Justice Willes, is that a single act amounting to bribery whether by treating or otherwise, committed by a candidate or his authorized agent, would avoid the whole election; but on that point His Honor the Chief Justice has read a passage from Woodward v Sarsons, supra, which seems to point the other way, and to require that, even at Common Law, the corrupt practice proved must be general in its character so as to have permeated the election, possibly on the part of both parties, so that it is no election at all, or that the corrupt practice must either have affected the result or given reasonable ground for belief that it might have affected it, so that what purported to be an election was not a free and pure election. In the meantime it is sufficient for us to answer the question which arises out of the reference put to us, together with the argument of Sir John Quick in the negative; that is to say, the question as re-stated by the Chief Justice, and argued for the petitioner, namely, whether under the Commonwealth Electoral Act a single act of bribery or treating would defeat an election. We are therefore relieved from answering that broad question of jurisdiction put to us in the original question, and I think it is fortunate that the Court is so relieved.

67 In Chanter (No 2), when the Court (constituted only by the Chief Justice) was sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, it was proved that the votes of electors not entitled to vote sufficient in numbers to “turn the scale” had been counted. The election was declared void. In so doing the language of Lord Coleridge CJ was employed by Griffith CJ (at 1 CLR 130-131):

In these circumstances can I say that the majority of the electors may not have been prevented from exercising their free choice? Suppose that, instead of 91 persons voting who had no right to vote, 91 persons who had a right to vote had come and claimed to vote, and were not allowed to vote. Clearly those persons would have been prevented from exercising their right to vote, and the election must have been declared void. I cannot see that any other result can follow when a number of persons, sufficient to change the majority into a minority, if they all voted against the candidate having the majority, have wrongly been allowed to vote. I cannot enquire how they actually voted. It is clear that they may have voted for the respondent in which case the petitioner's majority would be larger, or that they may have all voted for the petitioner, in which case the respondent would have been elected. But the numbers being as they are, it is impossible for me to say that the majority of the electors may not have been prevented from exercising their free choice.

68 The headnote to Chanter (No 1) is relevantly in the following terms:

The High Court has no jurisdiction under the Statute to avoid an election on the ground that one of the candidates has by himself or his agents been guilty of illegal practices, unless there is reasonable ground for believing that the result of the election may have been affected by such illegal practices.

Quare, whether by the Common Law of the Commonwealth the High Court has jurisdiction to avoid an election on the ground of a single act amounting to bribery at Common Law, committed by or on behalf of a candidate.

69 The above is the enactment context to relevant parts of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1905 (No 26 of 1905) (the 1905 Amendment Act). The 1905 Amendment Act made important changes to Pt XV1 to remedy the obscurity and potentially serious difficulty exposed in Chanter (No 1). First, sub-ss (2) and (3) were added to s 197 equivalent to sub-ss 360(2) and (3). Thus, the Court was empowered to exercise its powers as, in its discretion, it thinks just and sufficient (sub-s (2)) and “it is hereby declared that the power of the Court to declare that any person who was returned as elected was not duly elected, or to declare an election absolutely void, may be exercised on the ground that illegal practices were committed in connexion with the election” (sub-s (3)). So, the doubt as to the existence of power was clarified in pellucid and emphatic language.

70 How that jurisdiction was to be exercised and the different consequences of bribery and undue influence, on the one hand, and other illegal practices, on the other, were provided for in a new s 198A (which was the forerunner of s 362) as follows:

198A. (1) If the Court of Disputed Returns finds that a candidate has committed or has attempted to commit bribery or undue influence, his election, if he is a successful candidate, shall be declared void.

(2) No finding by the Court of Disputed Returns shall bar or prejudice any prosecution for any illegal practice.

(3) The Court of Disputed Returns shall not declare that any person returned as elected was not duly elected, or declare any election void –

(a) on the ground of any illegal practice committed by any person other than the candidate and without his knowledge or authority; or

(b) on the ground of any illegal practice other than bribery or corruption or attempted bribery or corruption,

unless the Court is satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected, and that it is just that the candidate should be declared not to be duly elected or that the election should be declared void.

71 It can be seen that the view of Willes J in respect of bribery (and, indeed, undue influence) was enacted. Secondly, and most relevantly here, the wording of the proviso after para (3)(b) is to be read in the context of Lord Coleridge’s expression of the common law of elections in 1875 in Woodward v Sarsons, referred to in Chanter (No 1), in particular the passage emphasised at [65] above.

72 When one examines the debate in the House of Representatives on the Bill that produced the 1905 Amendment Act, the relevance of Chanter (No 1) is most evident. The Bill was partly the outcome of recommendations of a Committee of the House. Mr Groom was the Minister for Home Affairs who moved that the Bill be read a second time. In discussion about illegal practices he participated in an exchange on 7 November 1905, as follows:

Mr Groom… In Part XVI., provision is made to remedy a defect in the Act. Honorable members will remember that when the High Court came to deal with an allegation against a successful candidate of illegal practices in connexion with his election, it held that it had no jurisdiction to entertain the charge. Speaking from memory, I think their decision was that, if they could entertain it at all, it would have to be shown that illegal practise had been carried on to such an extent as to have really affected the election.

Mr Chanter… They said they had no jurisdiction.

Mr Groom... I think they said that if the common law applied at all, it would be only to that extent. They held that in the particular case, Chanter v. Blackwood, they had no jurisdiction whatsoever. We propose, in this Bill, to give the Court power to declare that any person returned as elected was not duly elected, or to declare an election absolutely void, on the ground that illegal practices were permitted in connexion with this election.

In Clause 51,. Proposed substituted clause 198A, it is provided that –

If the court of disputed returns finds that a candidate has committed or attempted to commit bribery or undue influence, his election, if he is a successful candidate, shall be declared void.

Then, in sub-clause 3 of the same clause; it is provided that –

The Court of disputed returns shall not declare that any person returned as elected was not duly elected or declare any election void –

(a) On the ground of any illegal practice committed by any person other than the candidate, and without his knowledge or authority; or

(b) On the ground of any illegal practice other than bribery or corruption or attempted bribery or corruption unless the Court is satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected, and that it is just that the candidate should be declared not to be duly elected, or that the election should be declared void.

73 Given the clear reference to Chanter (No 1) in the House, the importance of Lord Coleridge’s statement of principle in the common law of elections, the distinguishing of bribery (and undue influence) from other illegal practices in s 198A, and thus the enshrining of the views of Willes J in respect of the consequences of the former, there can be little doubt that that part of the proviso “unless the court is satisfied that the result of the election was likely to be affected” was an attempt to encapsulate the aspects of Lord Coleridge’s views or at least something less than proof of the fact that the result was affected, since language that tended to such a meaning was already available in s 200. There is every reason to view the Parliament as placing in s 198A the two aspects of the common law of elections expressed by two such eminent judges (Lord Coleridge and Willes J) of then recent times. Thus “likely to have been affected” can be seen as a real chance, or to paraphrase Lord Coleridge: that a majority has been prevented, or there are reasonable grounds to believe that a majority might have been prevented. Of course, it is important to attend to the language of the statute and not that of Lord Coleridge. This provision has been re-enacted into modern times. Over the period of those re-enactments the concise expression of Tillmanns Butcheries has encapsulated a convenient expression of meaning of the phrase “likely to” in an appropriate context. Consideration of the 1905 Amendment Act and its enactment history and the wider common law context of such make it plain that the context is apt for this meaning of the words.

74 The next important piece of enactment history occurred in the passing of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1911 (Act No 17 of 1911) (the 1911 Amendment Act). Relevantly, there was added to the electoral offences in para 180(a) (which by this time had been amended by the 1905 Amendment Act and Act No 18 of 1906) and in paras 180(b) and (c), offences in paras (d) and (e) and the proviso to the whole section. Paragraphs (d) and (e) were the forerunners of s 329(1) and were, together with the proviso to that section, in the following terms:

(d) Printing, publishing, or distributing any electoral advertisement, notice, hand-bill, pamphlet, or card containing any representation of a ballot-paper, or any representation apparently intended to represent a ballot-paper, and having thereon any directions intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote;

(e) Printing, publishing, or distributing any electoral advertisement, notice, hand-bill, pamphlet, or card containing any untrue or incorrect statement intended or likely to mislead or improperly interfere with any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote.

Provided that nothing in paragraphs (d) and (e) of this section shall prevent the printing, publishing, or distributing of any card, not otherwise illegal, which contains instructions how to vote for any particular candidate, so long as those instructions are not intended or likely to mislead any elector in or in relation to the casting of his vote.

75 The record of the discussion of the Bill that led to the 1911 Amendment Act in Committee on 19 December 1911 is illuminating. A version of paras (d) and (e) had been drafted by Mr Wise which he accepted had been “hastily drafted late at night”. This version was replaced by a version of paras (d) and (e) and of the proviso that was proposed by Mr Fisher, the Prime Minister. Mr Fisher’s proposal was in the form as enacted, except that the proviso was expressed to be limited to instructions “not intended to mislead any elector”. The discussion was clear that the words “or likely” should be inserted in the proviso to reflect the substance of both paras (d) and (e). The discussion of these matters is revealing. Mr Wise referred to events that had occurred in a recent Victorian election in the district of Benambra and which had come to the attention of the member for Maribyrnong (who had moved the original paras (d) and (e)). Apparently, a card had been used in that election on one side of which was the direction to “vote for the progressive candidate”, signed by the Secretary to the Women’s National League. On the other side was what purported to be a copy of the ballot-paper for the division in which the figures 1 and 2 had been placed in squares opposite the two candidates’ names. At the bottom of the notice there was printed:

Unless you mark your paper as above it will be void.

76 This had also been published in the Argus newspaper, but withdrawn when the Department of Home Affairs called attention to it. (The similarity of such a statement to the translations of the statements on the corflutes in this case is striking.) Mr Wise is recorded as saying (at p 4852):

There would have been no objection to the direction, “If you wish to vote for Craven, mark your ballot papers thus,” but to say that the vote would be void if marked otherwise was a deliberate attempt to mislead the electors, such as we should discountenance. The proviso covers all cards honestly issued.

77 Discussion then took place about the need not to restrict the proviso to honesty alone. Two further matters should be noted. First, it appears clear that everyone in the discussion thought that with the addition of the words “or likely” to the proviso that the card used in Benambra would be covered by the provision. No one suggested it was not “in or in relation to the casting of the vote.” Secondly, there was discussion of the likelihood of anyone actually being misled. Mr Mahon (Coolgardie) said at 4853:

In paragraphs d and e the words “directions intended or likely to mislead,” are used, but in the proviso only the words “directions intended to mislead” appear. It seems to me that the same language should be used in both portions of the amendment. What directions would be likely to mislead would be difficult to decide. What might mislead an innocent like myself would not mislead experienced politicians like the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. This provision will probably give the police magistrates who have to deal with the cases brought under it a fine opportunity to display their political bias. They are sure to find that directions issued on behalf of their friends are not likely to mislead any intelligent person. If we think the electors not sufficiently intelligent to avoid being misled by the palpable misrepresentations which are sometimes circulated, we should leave no loop-hole for conflicting decisions under which one man may be punished and an other escape.

(Emphasis added.)

78 Whilst not too much can perhaps be taken from Mr Mahon’s doubts about the impartiality of some magistrates, one is assisted by the whole discussion in that the provision can be seen to be directed to “any elector”, the “innocent” and the “experienced”. It is at least an indication that one does not eliminate the less than astute or less than careful elector from the intended operation of the section. After all, the vote of the unintelligent, innocent, gullible or inexperienced voter is equal to the vote of the intelligent, worldly, astute or experienced voter.

79 This background assists in a conclusion that a statement that voting for a particular candidate and in a particular order in order to cast a valid vote is misleading or deceptive in relation to the casting of an elector’s vote and that it is likely to mislead or deceive if it is apt to mislead even unintelligent electors by palpable misrepresentations that are unlikely to mislead electors of reasonable intelligence and astuteness.

80 The decision in Bowen v Bridge in 1916 provoked strongly worded dissenting judgments of Griffith CJ and Barton J. The case did not concern the 1902 Act as amended, but a New South Wales statute. Chief Justice Griffith saw the majority as overturning Chanter (No 1) and (No 2), as well as other cases of Hirsch v Phillips (1904) 1 CLR 132 and Blundell v Vardon (1907) 4 CLR 1463. That this debate occurred in 1916 does not remove the contextual importance of the Chanter cases to the passing of the 1905 amendments.

81 In 1918 there was a consolidation and amendment of the 1902 Act as amended in Act No 27 of 1918 (the 1918 Act). Section 180 became s 161, s 182 became s 170, s 197 became s 189, s 198A became s 191, and s 200 became s 194.

82 In 1922, an amendment was made to s 194 (the old s 200). The amendment was provoked by the decision of Isaacs J (sitting alone as the Court of Disputed Returns) in Kean v Kerby. At 27 CLR 457-458, Isaacs J referred to Chanter (No 2) at 131 and Bridge v Bowen. He said that the former (Griffith CJ’s dispositive reasoning) could not be reconciled with the majority’s decision in the latter. He then referred to the text of the relevant English statute in comparison to s 194, as follows at 27 CLR 458:

In England it is enacted that no election shall be declared invalid by reason of non-compliance with the election rules or mistake in the use of the forms, if it appears to the tribunal (1) that the election was conducted in accordance with the principles laid down in the body of the Act, and (2) that such non-compliance or mistake did not affect the result of the election. In other words, if the matter is left so that the mistake may have affected the result, the election may be declared invalid. Under our Act it is different. By sec. 194 it is provided that “No election shall be avoided … on account of the … error of any officer which shall not be proved to have affected the result of the election.”

83 At 27 CLR 459, he resolved the case by reference to Bridge v Bowen, as follows:

The case of Bridge v. Bowen shows that, in view of the onus, unless the fact of intention is proved, the election, so far as it depends on the refusals I have mentioned, cannot be disputed. The matter must be determined on principle.

84 Thus, Isaacs J introduced into Commonwealth electoral law, as he and the majority had in relation to the New South Wales provision in Bridge v Bowen, a need, if the onus was to be discharged, of proving how people would have or did vote. Immediately after the above passage at 459 he continued at 459-460:

The fundamental common law principle is that “elections ought to be free.” That basic principle was reaffirmed and enforced by the Statute 3 Edw. I. c. 5. It lies at the root of all election law. For centuries parliamentary elections were conducted by open voting. Freedom of election was sought to be protected against intimidation, riots, duress, bribery, and undue influence of every sort. Nevertheless it was found necessary to introduce the ballot system of voting. The essential point to bear in mind in this connection is that the ballot itself is only a means to an end, and not the end itself. It is a method adopted in order to guard the franchise against external influences, and the end aimed at is the free election of a representative by a majority of those entitled to vote. Secrecy is provided to guard that freedom of election. It is common ground, however, that in some cases, which need not be particularized, the Court is at liberty to inquire how a person voted. Sec. 190 provides that “the Court … may inquire into the identity of persons, and whether their votes were improperly admitted or rejected, assuming the roll to be correct.” Reading that section with sec. 194 (already quoted), it cannot be doubted that in some instances of actual voting it is proper for the Court to ascertain how a person voted. It is, in my opinion, impossible to contend that a person who was refused a ballot-paper altogether is in a worse position to defend his right of voting than if he had received a ballot-paper and his vote had been wrongly disallowed. And in such a case how is he to protect his right of franchise, which is the most important of all his public rights as a member of a self-governing community? The ballot, being a means of protecting the franchise, must not be made an instrument to defeat it. When a vote is recorded in writing, no doubt the writing itself is the proper evidence of the way the elector intended to vote. When it is not recorded, the only means of establishing that intention is the evidence of the elector himself. That is the only mode of protecting the right which an elector has endeavoured to exercise and has been prevented by official error from exercising.

85 This decision led the Parliament in s 25 of Act No 14 of 1922 (the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1922) (the 1922 Amendment Act) to omit the words “shall not be proved to have affected” and insert in their stead “did not affect” and to insert the proviso to s 194 now seen in the proviso to s 365 (see [18] above).

86 In debate in the House of Representatives on 14 September 1922 the proposed amendments were discussed. The Attorney-General, Mr Groom, said in the Second Reading Speech at pp 2268-2269 of Hansard:

Clause 27 [which became s 25] embodies another important amendment. The point with which it deals arose in the disputed Ballarat election. The principal Act provides —

No election shall be avoided on account of any delay in the declaration of nominations, the polling, or the return of the writ, or on account or the absence or error of an officer which shall not be proved to have affected the result of the election.

Mr. Justice Isaacs, in his judgment in the case of Kean versus Kerby, said —

The Australian Act differs very considerably from the English legislation in several respects relevant to this case. Particularly I refer to the duty of the Court in the case of official errors. In England it is enacted that no election shall be declared invalid by reason of noncompliance with the election rule or mistake in the use of the forms, if it appears to the tribunal (1) that the election was conducted in accordance with the principles laid down in the body of the Act, and (2) that such non-compliance or mistake did not affect the result of the election. In other words, if the matter is left so that the mistake may have affected the result, the election may be declared invalid. Under our Act it is different. By section 194 it is provided that " no election shall be avoided . . . on account of the . . . error of any officer which shall not be proved to have affected the result of the election." The "result" means the return of the particular candidate, and not the number of his majority.