FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

McGlade v South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Aboriginal Corporation (No 2) [2019] FCAFC 238

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applications be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the costs of the respondents, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

WAD 546 of 2018 (LEAD APPLICATION) WAD 549 of 2018 WAD 557 of 2018 WAD 565 of 2018 (OTHER FILES NAMED IN THE SCHEDULE) | ||

BETWEEN: | MARIANNE MACKAY Applicant | |

AND: | SOUTH WEST ABORIGINAL LAND & SEA COUNCIL ABORIGINAL CORPORATION First Respondent STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Second Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Third Respondent NATIVE TITLE REGISTRAR Fourth Respondent | |

JUDGES: | ALLSOP CJ, MCKERRACHER AND MORTIMER JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 19 DECEMBER 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applications be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the costs of the respondents, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

[1] | |

[13] | |

[16] | |

[37] | |

[37] | |

[38] | |

[40] | |

The Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA decision (the McGlade decision) | [41] |

[85] | |

[86] | |

[92] | |

[106] | |

[108] | |

[116] | |

[122] | |

[125] | |

[131] | |

[132] | |

[134] | |

[135] | |

[135] | |

[172] | |

[195] | |

[205] | |

[239] | |

[245] | |

[252] | |

[254] | |

[269] | |

[279] | |

[279] | |

[294] | |

[297] | |

[303] | |

[304] | |

[343] |

THE COURT:

1 The applicants seek judicial review of six decisions of the Registrar to the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) to register six indigenous land use agreements (ILUAs). The applicants are in two groups. In the first group of applicants, the application by Ms Mingli Wanjurri McGlade has been treated as the lead application (the McGlade applicants/applications). In the second group of applicants, an application by Ms Marianne Mackay has been treated as the lead application (the Mackay applicants/applications). The Mackay applicants adopt the same arguments as those advanced in support of the McGlade application, but raise a further independent ground which also falls for consideration.

2 The challenge to the Registrar’s decisions concerns her registration of six ILUAs on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements under s 199A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA).

3 The six ILUAs pertain to a large area in the South West of Western Australia (the Settlement Area). The Settlement Area has been the subject of numerous native title determination applications or claims by the Noongar people. Some date back to the 1990s. None of them, however, has led to a successful determination that the Noongar people hold native title rights and interests over any part of the Settlement Area. The ILUAs, taken as a totality would implement an agreement between the State of Western Australia and representatives of the Noongar people that would have the effect of settling all native title claims of those people.

4 The ILUAs were intended to give effect to a final settlement of native title claims that had been negotiated by the first respondent, the South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council Aboriginal Corporation (SWALSC), and the State over several years (the Settlement). SWALSC’s involvement in these negotiations accorded with instructions given to it by representatives of family groups represented in registered Noongar claims, as well as input obtained from other Noongar people, including through dozens of community meetings.

5 Under the Settlement, the State would provide a package of benefits (with an estimated value of $1.3 billion) in return for the Noongar people surrendering all native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters in the Settlement Area, consenting to determinations that native title does not exist and validating potentially invalid acts that have been carried out by the State in the Settlement Area. The ILUAs purport to deal with a final settlement of the native title claims in respect of an area of over 200,000 square kilometres.

6 The Noongar people are indigenous Australians who claim native title rights in respect of land and waters in the South West of Western Australia, from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the south coast. There are between 30,000 and 40,000 Noongars in Western Australia. Most of them live in Perth.

7 Part of the Noongar history concerning the NTA proceedings includes Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 153 FCR 120 where Wilcox J recognised (at [841]-[848]) the right of the Noongar people to occupy, use and enjoy lands and waters in the Perth metropolitan area, subject to the principle of extinguishment. That decision, finding the existence of native title rights, was reversed on appeal in Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84. Since that time, the State and other parties have engaged in negotiations resulting in the six ILUAs.

8 The six registered ILUAs the subject of these judicial review proceedings are:

(a) the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2017/014 (the Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA);

(b) the Ballardong People Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2017/012 (the Ballardong People ILUA);

(c) the South West Boojarah #2 Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2017/013 (the South West Boojarah #2 ILUA);

(d) the Whadjuk People Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2017/015 (the Whadjuk ILUA);

(e) the Gnaala Karla Booja Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2015/005 (the Gnaala Karla Booja ILUA); and

(f) the Yued Indigenous Land Use Agreement, WI2015/0019 (the Yued ILUA).

9 It is the authorisation process mandated by the NTA for the registration of ILUAs which is the focus of attention in these challenges. Between January and March 2015, there were six meetings conducted. Persons identified as holding native title in respect of the area covered by each ILUA were invited to the meetings, as well as persons who claimed they were entitled to hold native title in respect of those areas. A central feature of the meetings was that they were held “on country”, being locations within the Settlement Area for each of the proposed ILUAs. Thus:

(a) the meeting to authorise the Gnaala Karla Booja ILUA took place on 31 January 2015 in Bunbury (approximately 173 km from Perth);

(b) the meeting to authorise the South West Boojarah #2 ILUA took place on 14 February 2015 in Busselton (approximately 195 km from Perth);

(c) the meeting to authorise the Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA took place on 21 February 2015 in Katanning (approximately 250 km from Perth);

(d) the meeting to authorise the Yued ILUA took place on 7 March 2015 at Gingin (approximately 68 km from Perth);

(e) the meeting to authorise the Ballardong People ILUA took place on 14 March 2015 at Northam (approximately 83 km from Perth); and

(f) the meeting to authorise the Whadjuk People ILUA took place on 28 March 2015 in Cannington in Perth.

10 The McGlade applicants contend that the Registrar erred in finding that the authorisation conditions for registration were satisfied. In particular, they submit that the Registrar could not have found, as she did, that all the people identified as holding native title rights in respect of the Settlement Area had authorised the making of each ILUA.

11 In the challenges brought by the Mackay applicants, it is contended that the subject of each of the ILUAs was native title held by all Noongar people. However, it is contended that the notices inviting attendees to each authorisation meeting did not invite all Noongar people who held that native title to the meetings to consider the six ILUAs. Rather, it is said that those invitations were limited to descendants of particular Noongar people. This point was raised with the Registrar, but the Registrar, it is contended, failed to consider the point and reached a conclusion on the basis that a subgroup of the common law native title holders could authorise each ILUA. The Mackay applicants argue that this is an error of law.

12 A direction was given under s 20(1A) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) for the judicial review applications to be heard and determined by a Full Court.

13 The two tranches of applications are judicial review proceedings based on specific grounds of asserted legal error. It is important to emphasise that these proceedings are not at large or in the nature of a de novo appeal. Nor do the proceedings engage questions of merit either as to the terms and content of the ILUAs or as to the reasons why the ILUAs are opposed (other than the specifically asserted legal errors).

14 But, as will be seen, the Registrar was required to form a view as to the reasonableness of certain actions. Within that limited context, the factual conclusions that were to be reached by the Registrar in arriving at that view are relevant to the legal errors asserted on this application. Quite appropriately, the applicants have not raised in these proceedings all the complaints pressed on the Registrar but have confined the arguments to specific matters said to give rise to the asserted legal errors. It is not necessary, therefore, to review the entire catalogue of concerns ventilated before the Registrar.

15 The challenges raised by both sets of applicants are made pursuant to the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (the ADJR Act). Section 5 of the ADJR Act sets out those grounds upon which judicial review of administrative decisions, such as the determination of the Registrar, may be advanced. Section 5 relevantly provides:

5 Applications for review of decisions

(1) A person who is aggrieved by a decision to which this Act applies that is made after the commencement of this Act may apply to the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court for an order of review in respect of the decision on any one or more of the following grounds:

…

(e) that the making of the decision was an improper exercise of the power conferred by the enactment in pursuance of which it was purported to be made;

(f) that the decision involved an error of law, whether or not the error appears on the record of the decision;

…

(h) that there was no evidence or other material to justify the making of the decision;

(j) that the decision was otherwise contrary to law.

(2) The reference in paragraph (1)(e) to an improper exercise of a power shall be construed as including a reference to:

(a) taking an irrelevant consideration into account in the exercise of a power;

(b) failing to take a relevant consideration into account in the exercise of a power;

…

(Emphasis added.)

16 The provisions addressing the making and registration of ILUAs are in Div 3 of Pt 2 of the NTA. This Division relates to the future use of land and water the subject of a native title claim. The provisions were added by the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth).

17 ILUAs may come in many formats and may pertain to a wide range of matters, including matters of far less significance than the ILUAs under consideration in this dispute. Before an ILUA is binding it must be registered and before it is registered the native title holders, generally through their representatives, must agree to the future use of land and waters the subject of native title.

18 Section 24AA(3) of the NTA concerns the validity of future acts contemplated in ILUAs. It provides:

24AA Overview

…

Validity under indigenous land use agreements

(3) A future act will be valid if the parties to certain agreements (called [ILUAs] … – see Subdivisions B, C and D) consent to it being done and, at the time it is done, details of the agreement are on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements. An indigenous land use agreement, details of which are on the Register, may also validate a future act (other than an intermediate period act) that has already been invalidly done.

(Emphasis added.)

19 There are three categories of ILUAs as dealt with in subdiv B, C and D of Div 3: body corporate agreements; area agreements; and alternative procedure agreements. Each type of ILUA is subject to different requirements as to the persons who must be parties to the agreement, its content and the procedures involved in the making and registration of the ILUA.

20 This dispute concerns “area agreements”, which are addressed in subdiv C. They are a common type of ILUA and are used where there is no registered native title body corporation in relation to the whole of the area the subject of the agreement, for example, where there has not been a final native title determination in relation to that area: see s 24CC of the NTA.

21 Significantly, for the purpose of these applications, area agreements may extinguish native title rights: s 24CB(e) of the NTA. An area agreement will not take statutory effect until it is registered by virtue of ss 24EA-24EBA of the NTA.

22 Section 251A in Div 4 of Pt 15 of the NTA provides for the authorisation of an ILUA by persons who hold native title in relation to the area the subject of the ILUA.

23 In summary, s 251A contemplates that persons holding native title in the area covered by an ILUA may authorise the making of the ILUA in one of two ways. If there is a traditional decision-making process which “must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind”, the authorisation is to be given or not given in accordance with that process. Where there is no such process, the making of the ILUA is to be authorised in accordance with a decision-making process “agreed to and adopted by” the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title. This section is discussed in greater detail below, but it is relevant to note that it is the latter process which is the focus in these reasons.

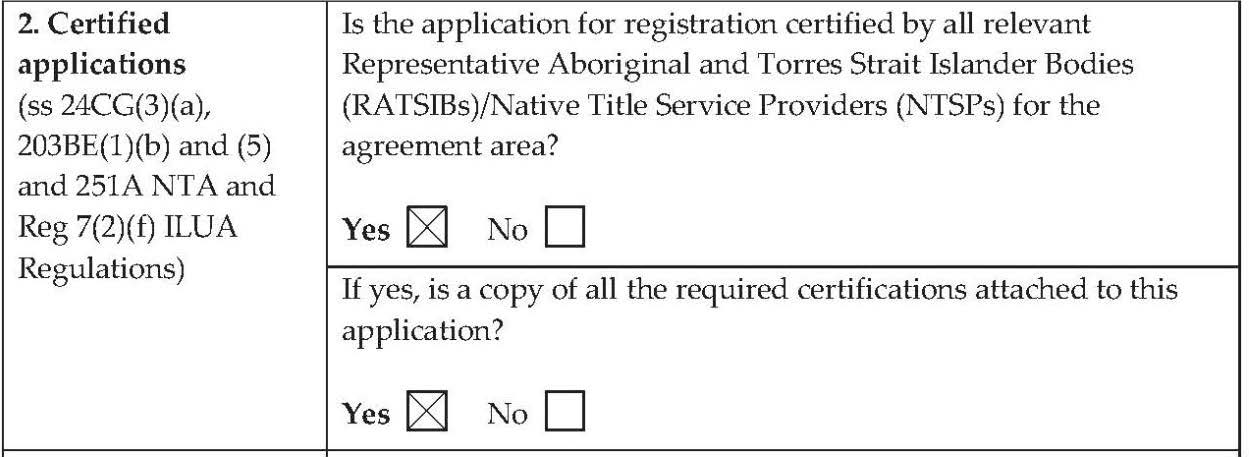

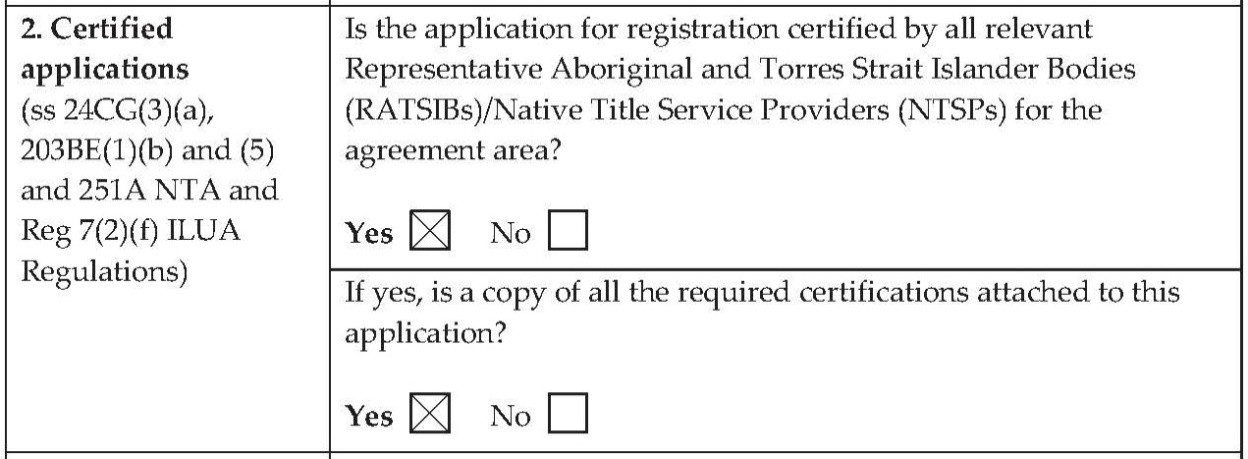

24 In the present circumstances, SWALSC, as the representative body, has certified in the case of each of the six ILUAs that it is of the opinion that all reasonable efforts were made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the ILUA have been identified and, secondly, that all the persons so identified have authorised the making of the ILUA. This certification procedure is provided for by s 203BE of the NTA which is, relevantly, in these terms:

203BE Certification functions

General

(1) The certification functions of a representative body are:

(a) to certify, in writing, applications for determinations of native title relating to areas of land or waters wholly or partly within the area for which the body is the representative body; and

(b) to certify, in writing, applications for registration of indigenous land use agreements relating to areas of land or waters wholly or partly within the area for which the body is the representative body.

Certification of applications for determinations of native title

(2) A representative body must not certify under paragraph (1)(a) an application for a determination of native title unless it is of the opinion that:

(a) all the persons in the native title claim group have authorised the applicant to make the application and to deal with matters arising in relation to it; and

(b) all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the application describes or otherwise identifies all the other persons in the native title claim group.

Note: Section 251B deals with authority to make the application.

…

Statement to be included in certifications of applications for determinations of native title

(4) A certification of an application for a determination of native title by a representative body must:

(a) include a statement to the effect that the representative body is of the opinion that the requirements of paragraphs (2)(a) and (b) have been met; and

(b) briefly set out the body’s reasons for being of that opinion; and

(c) where applicable, briefly set out what the representative body has done to meet the requirements of subsection (3).

Certification of applications for registration of indigenous land use agreements

(5) A representative body must not certify under paragraph (1)(b) an application for registration of an indigenous land use agreement unless it is of the opinion that:

(a) all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the agreement have been identified; and

(b) all the persons so identified have authorised the making of the agreement.

Note: Section 251A deals with authority to make the agreement.

Statement to be included in certifications of applications for registration of indigenous land use agreements

(6) A certification of an application for registration of an indigenous land use agreement by a representative body must:

(a) include a statement to the effect that the representative body is of the opinion that the requirements of paragraphs (5)(a) and (b) have been met; and

(b) briefly set out the body’s reasons for being of that opinion.

25 An application for registration of an area agreement is dealt with by s 24CG of the NTA, which is these terms:

24CG Application for registration of area agreements

Application

(1) Any party to the agreement may, if all of the other parties agree, apply in writing to the Registrar for the agreement to be registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

Things accompanying application

(2) The application must be accompanied by a copy of the agreement and any other prescribed documents or information.

Certificate or statement to accompany application in certain cases

(3) Also, the application must either:

(a) have been certified by all representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area in performing their functions under paragraph 203BE(1)(b) in relation to the area; or

(b) include a statement to the effect that the following requirements have been met:

(i) all reasonable efforts have been made (including by consulting all representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area) to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the agreement have been identified;

(ii) all of the persons so identified have authorised the making of the agreement;

Note: The word authorise is defined in subsection 251A(1).

together with a further statement briefly setting out the grounds on which the Registrar should be satisfied that the requirements are met.

…

26 As will be seen from s 24CG(3)(a), in circumstances where a representative body has given the certificate under s 203BE(5), an application for registration must include the certification or a statement that the requirements under s 203BE(5)(a) and s 203BE(5)(b) of the NTA have been met.

27 There are then procedural requirements for the Registrar to give notice to various persons under s 24CH of the NTA. Section 24CI of the NTA then provides for objections to registrations to be made by persons who claim to hold native title. Objection on the ground that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) and s 203BE(5)(b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification is expressly contemplated. Section 24CI(1) is in these terms:

24CI Objections against registration

Making objections

(1) If the application was certified by representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area (see paragraph 24CG(3)(a)), any person claiming to hold native title in relation to any of the land or waters in the area covered by the agreement may object, in writing to the Registrar, against registration of the agreement on the ground that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification.

…

(Emphasis added.)

28 The Registrar is required by s 24CJ of the NTA to decide whether or not to register the ILUAs at the end of the notice period. Section 24CK imposes a requirement on the Registrar in the following terms:

24CK Registration of area agreements certified by representative bodies

Registration only if conditions satisfied

(1) If the application for registration of the agreement was certified by representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area (see paragraph 24CG(3)(a)) and the conditions in this section are satisfied, the Registrar must register the agreement. If the conditions are not satisfied, the Registrar must not register the agreement.

First condition

(2) The first condition is that:

(a) no objection under section 24CI against registration of the agreement was made within the notice period; or

(b) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, but they have all been withdrawn; or

(c) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, all of them have not been withdrawn, but none of the persons making them has satisfied the Registrar that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification of the application by any of the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies concerned.

Second condition

(3) The second condition is that if, when the Registrar proposes to register the agreement, there is a registered native title body corporate in relation to any land or waters in the area covered by the agreement, that body corporate is a party to the agreement.

Matters to be taken into account

(4) In deciding whether he or she is satisfied as mentioned in paragraph (2)(c), the Registrar must take into account any information given to the Registrar in relation to the matter by:

(a) the persons making the objections mentioned in that paragraph; and

(b) the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies that certified the application;

and may, but need not, take into account any other matter or thing.

(Emphasis added.)

29 There are two key definitional provisions which stand in juxtaposition to each other in a way which illustrates the legislative intention concerning authorisation of the making of ILUAs. The first of those provisions is s 251A, the terms of which will be examined closely in due course. The second is s 251B, which deals with authorisation for the purposes of making a native title determination application, rather than for the making of an ILUA. Those sections provide:

251A Authorising the making of indigenous land use agreements

(1) For the purposes of this Act, persons holding native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by an indigenous land use agreement authorise the making of the agreement if:

(a) where there is a process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind—the persons authorise the making of the agreement in accordance with that process; or

(b) where there is no such process—the persons authorise the making of the agreement in accordance with a process of decision-making agreed to and adopted, by the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, in relation to authorising the making of the agreement or of things of that kind.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), when authorising the making of the agreement, a native title claim group may do either or both of the following:

(a) nominate one or more of the persons who comprise the registered native title claimant for the group to be a party or parties to the agreement;

(b) specify a process for determining which of the persons who comprise the registered native title claimant for the group is to be a party, or are to be parties, to the agreement.

251B Authorising the making of applications

For the purposes of this Act, all the persons in a native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise a person or persons to make a native title determination application or a compensation application, and to deal with matters arising in relation to it, if:

(a) where there is a process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind—the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise the person or persons to make the application and to deal with the matters in accordance with that process; or

(b) where there is no such process—the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise the other person or persons to make the application and to deal with the matters in accordance with a process of decision-making agreed to and adopted, by the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group, in relation to authorising the making of the application and dealing with the matters, or in relation to doing things of that kind.

30 It is common ground that the onus of demonstrating that the requirements of s 203BE(5) of the NTA were not satisfied lies with those who make the objection: Bright v Northern Land Council [2018] FCA 752 per White J (at [49]).

31 The statute requires (in relation to this onus) a demonstration that s 203BE(5)(a) and s 203BE(5)(b) of the NTA have not been satisfied, rather than an absence of certification or an absence of opinion justifying the certification as referred to in subs (5). The parties have correctly approached these proceedings as though it is the matters within s 203BE(5)(a) and s 203BE(5)(b) which are and were in contest before the Registrar.

32 The Mackay applicants argue that the Registrar erred in being satisfied that the ILUAs were authorised within the meaning of s 251A(1)(b) of the NTA.

33 In Fesl v Delegate of Native Title Registrar (2008) 173 FCR 150, Logan J had occasion to consider the effect of the word “all” in s 24CG(3)(b)(ii) of the NTA and observed (at [26]) that in relation to authorisation of an area agreement, the word “all” does not, when read together with s 251A and in the context of the NTA as whole, mean that a single dissentient or non-participant will invariably have an ability to veto the authorisation of an ILUA.

34 His Honour considered (at [71]) that the following principles applied in relation to s 251B and mutatis mutandis to s 251A of the NTA:

…

(a) the effect of the s 251B is to give the word “all” in, materially, the table which appears below s 61(1) a more limited meaning than it might otherwise have;

(b) in those cases where there is no relevant traditional decision-making process, s 251B does not mandate any one particular decision-making process, only that it be one that is agreed to and adopted by the persons in the native title claim group or compensation group;

(c) “agreed to and adopted by” imports the giving to all of those whose whereabouts are known and have capacity to authorise a reasonable opportunity to participate in the adoption of a particular process and the making of decisions pursuant to that process;

(d) unanimous decision-making is not mandated;

(e) agreement to a particular process may be proved by the conduct of the parties even in the absence of proof of a formal agreement.

35 His Honour continued (at [72]):

Section 251A plays an identical role in relation to native title group “authorisation” decisions as referred to in s 24CG(3)(b)(ii) to that which s 251B plays in relation to native title claim group “authorisation” decisions under s 61 of the [NTA]. The language employed in s 251A compared to that in s 251B is very similar and each gives content to the word “authorise” in a provision in which the word “all” appears in relation to the making of “authorisation” decisions. The analogy of application between the two sections is indeed a close one. In my opinion therefore, each of the propositions which I have distilled from cases concerning s 251B has like application, mutatis mutandis, to the meaning and effect of s 251A and in relation to the impact of that section on “authorisation” for the purposes of s 24CG(3)(b)(ii) of the [NTA]. In turn that means that the Delegate was entitled to conclude that the “second condition” for which s 24CL of the [NTA] provides was satisfied.

36 The cases concerning authorisation within the meaning of s 251B(b) (for the purposes of an application to replace an applicant under s 66B of the NTA) have reiterated the principles that s 251B(b) does not require that “all” of the members of the relevant claim group be involved in making the decision. The key question will be whether a reasonable opportunity to participate in the decision-making process has been afforded by the notice for a relevant meeting. The usual question is whether the notice was sufficiently clear to enable persons to whom it has been addressed to judge for themselves whether or not to attend a meeting and to vote for or against a proposal: see, for example, Lawson on behalf of the ‘Pooncarie’ Barkandji (Paakantyi) People v Minister for Land and Water Conservation for the State of New South Wales [2002] FCA 1517 per Stone J (at [25] and [27]-[28]); Dingaal Tribe v State of Queensland and Ors [2003] FCA 999 per Cooper J (at [8] and [32]); Coyne v State of Western Australia [2009] FCA 533 per Siopis J (at [27]-[51] and the cases therein cited); Weribone on behalf of the Mandandanji People v State of Queensland [2013] FCA 255 per Rares J (at [40]); and TJ v Western Australia (2015) 242 FCR 283 per Rares J (at [91]).

37 The grounds advanced for the McGlade applicants are in these terms:

Misinformation provided to native title holders

1. In deciding that the first condition in s 24CK(2)(c) of the NTA was satisfied, the Registrar failed to take into account as a relevant consideration the uncontradicted material that:

(a) the persons holding native title in relation to the land covered by the ILUA had wrongly been advised by the Third Respondent (SWALSC) that the only process by which the ILUA could be authorised within the meaning of s 251A of the NTA is by those voting in person at a meeting “on country”[.]

2. On the basis of the uncontradicted material, the Registrar erred in law in finding that the first condition in s 24CK(2)(c) was satisfied.

Incarcerated native title holders denied opportunity to participate

3. The Registrar erred in law in finding that the first condition in s 24CK(2)(c) was satisfied, in circumstances where:

(a) as SWALSC well knew, a significant number of native title holders were unable to attend the authorisation meeting as they were incarcerated;

(b) those persons were not given an opportunity to participate in the authorisation process.

Native title holders not afforded reasonable opportunity to participate

4. The Registrar erred in law in finding that the first condition in s 24CK(2)(c) was satisfied in circumstances where most native title holders were not afforded a reasonable opportunity to participate in the authorisation process.

Particulars

There are at least 15,000 adult Noongar persons.

No provision was made for casting a vote otherwise than in person at the authorisation meeting.

Most Noongar people resided in Perth. The authorisation meeting was held at a distance of approximately 250 kilometres from Perth.

38 The grounds advanced for the Mackay applicants are as follows:

1. The [Registrar] erred in law in concluding that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land and waters in the areas covered by the WI2015/005 Gnaala Karla Booja ILUA, WI2015/009 Yued ILUA, WI2017/012 Ballardong People ILUA, WI2017/013 South West Boojarah #2 ILUA, WI2017/014 Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA and WI2017/015 Whadjuk People ILUA authorised each ILUA.

PARTICULARS

(a) The [Registrar] proceeded on the erroneous basis that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land and waters in respect of each of the ILUAS were properly identified by [SWALSC] as the members of one or more of the groups of Registered Claimants or Other Claimants identified by the SWALSC for each of the ILUA areas; and

(b) Further, the [Registrar] misdirected herself by proceeding to limit those she assessed to be all the persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land and waters in respect of each of the ILUAs by reference only to whether they were descended from apical ancestor lists set out in the Notices of Authorisation meetings for each of the Agreement Areas prepared by the SWALSC; and

(c) The Registrar, if she had properly directed herself, would have proceeded on the basis that there is a single communal native title held by a single Noongar native title community and that all members of the single Noongar native title community ought to have been invited to each meeting convened to authorise each of the ILUAs for each of the Agreement Areas within the area of the Single Noongar Claim area in order to conclude that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land and waters in the areas covered by each of the ILUAs authorised or had an opportunity to authorise entry into each ILUA.

39 Each of the applicants seeks orders setting aside the Registrar’s decisions and costs.

40 As might be expected, there is much common content in each of the Registrar’s decisions. That common content is not repeated in these reasons. The challenges raised can be addressed by reference to the decisions directly affecting the two lead applicants.

The Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA decision (the McGlade decision)

41 In the Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar ILUA decision, which is mirrored by the other five ILUA decisions (save for some voting and other details), the Registrar noted that the ILUA was one of six agreements that had been negotiated by SWALSC and the “Noongar Negotiation Team” on behalf of the Noongar people of the South West and the State to implement the proposed South West Settlement. She noted that the objective of the South West Settlement was to resolve all native title determination applications brought by the Noongar people across the South West region of Western Australia and referred to the meeting which had been held in respect of the ILUAs (referred to at [8]). The Registrar outlined the chronology, including the litigation in McGlade v Native Title Registrar (2017) 251 FCR 172 (McGlade (FCAFC)) and the ruling in that case that the Registrar did not have jurisdiction to register four of the agreements as not all parties comprising the registered native title claimants had signed them. Reference was made to the amending legislation, which responded to that deficiency.

42 The Registrar then proceeded to detail the information which had been considered pursuant to s 24CK(4) of the NTA, noting that she was required to examine any information given by the objectors and the representative body that certified the application and that she may, but need not, take into account any other matter or thing. She said that the material she had taken into account was:

• the information contained in the application for registration, agreement and accompanying documents;

• the geospatial assessment and overlap analysis (geospatial assessment) dated 29 August 2017;

• the geospatial end of notification overlap analysis dated 12 January 2018;

• the material provided to the Registrar during the process of procedural fairness; and

• the results of [her] own searches using the NNTT’s mapping database.

43 The Registrar then turned to examine the legislation and the relevant case law, noting in relation to s 24CK of the NTA that if the conditions of s 24CK(2) and s 24CK(3) are satisfied, she must register the ILUA, and if they are not satisfied, she must not register the ILUA.

44 Addressing the first condition for registration, the Registrar set out s 24CK(2) and s 24CI(1) of the NTA and proceeded to examine the objections having regard to the requirements of those provisions and concluding (at [53]) that each objection was validly made (as distinct from being correct).

45 The Registrar set out her understanding of the nature of the task involved in relation to s 24CK(2)(c) of the NTA, noting the requirements of s 203BE(5).

46 The Registrar followed the decision of White J in Bright to the effect that s 24CK(2)(c) of the NTA required objectors to discharge an onus to satisfy the Registrar that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) and s 203BE(5)(b) were not satisfied. In examining the certificate containing the required statement of opinion by SWALSC, the Registrar noted that the certificate also provided details of that opinion, including the following:

3.1 The efforts that have been made to ensure that all people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area have been identified have included the following:

(a) As part of the South West Native Title Settlement negotiations, during 2012 SWALSC and the State requested the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) to provide formal Notice of the Wagyl Kaip and the Southern Noongar registered native title claims inviting any Noongar person who could trace descent from one or more of the named apical ancestors listed in the Notice or who considered there were additional apical ancestors who were relevant to the claims to contact the NNTT by 20 April 2012, the date set out in the Notice to receive or request further information about the claims. Subject to NNTT processes new information that may lead to identification of new apical ancestors was provided to SWALSC for further research purposes.

Throughout and during the South West Native Title Settlement negotiation phase, at the request of SWALSC and the State the NNTT conducted extensive historical and current geospatial data searches providing data analysis information of registered and unregistered claims in the South West, including for the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar registered native title claim areas.

From the commencement of and during the South West Native Title Settlement negotiation phase SWALSC provided information to Noongar people about the South West Native Title Settlement negotiations process and intention to carry out negotiations for the proposed Agreement and for Noongar people to contact SWALSC to assist SWALSC to identify those people who hold or may hold native title in the Agreement area.

These efforts confirmed that the members of the native title claim groups for the following native title determination applications - to the extent that they asserted such native title rights and interests - were people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area:

(i) WAD6286/1998 (Alan Bolton & Ors - v- the State of Western Australia & Ors (Wagyl Kaip)) (Wagyl Kaip Claim);

(ii) WAD6134/1998 (Dallas Coyne & Ors and State of Western Australia & Ors (Southern Noongar) (Southern Noongar Claim);

(iii) WAD33/2007 (Gerald Williams & Ors and State of Western Australia (Wagyl Kaip - Dillon Bay People) (Wagyl Kaip - Dillon Bay People Claim); and

(iv) WAD6006/2003 (Anthony Bennell & Ors v State of Western Australia (Single Noongar Claim (Area 1)) (Single Noongar Claim).

(b) In addition to the above efforts, SWALSC has commissioned - and has relied on the findings of - an extensive research program to identify those people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area. This program included:

(i) the ethno-historical, anthropological and genealogical research undertaken to support the lodgement (and litigation) of the Wagyl Kaip Claim and the Southern Noongar Claim; and

(ii) the fieldwork and further research that contributed to the production of the Anthropologist’s Report produced in connection with the lodgement (and litigation) of the Single Noongar Claim.

(c) Since the commencement of the South West Settlement negotiations, SWALSC’s research section has engaged in a specific connection research process as agreed with the State in the Heads of Agreement dated 2009. This connection research process involved “Agreed Facts” sample genealogies reviewed with the State Solicitor’s Office (SSO) and the production of Apical Ancestor Reports for the purposes of the negotiations and identification of the Native Title Agreement Groups.

(d) During the Settlement ILUA negotiation period, SWALSC’s research section has focused on this connection research process, which required reading and analysing all available sources of information relevant to the area of the relevant Settlement ILUA (in this case, the Agreement Area) in an effort to determine the identity of:

(i) the Aboriginal people who (prior to European settlement of the South West in 1829):

A. by the traditional laws they acknowledged and the traditional customs they observed, had a connection to the Agreement Area; and

B. held rights and interests in relation to the land or waters in the Agreement Area that were possessed under such traditional laws and traditional customs,

(together, WK & SN Apical Ancestors); and

(ii) the descendants of these WK & SN Apical Ancestors (WK & SN Area Descendants).

(e) Numerous types of sources were consulted during this process, including (but not limited to) early 20th century ethnographic materials and genealogies (such as those of Daisy Bates and Norman Tindale), the diaries of early colonists and explorers, Native Welfare Department files sourced from the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and donated by SWALSC clients, Western Australian Birth, Death and Marriage Records, Mission records, published materials and oral histories of SWALSC clients. SWALSC Anthropologists have a high degree of familiarity with the source materials relevant to the regions of the South West (and the area of the Noongar Claims) to which they have been assigned.

(f) In consulting these materials, SWALSC Anthropologists applied a historiographical methodology, weighing the value of materials based on the context in which they were produced and interrogating potential underlying biases and inaccuracies in the materials. The same rigour was caused and applied to materials whatever their provenance. The research process described above often resulted in the identification of new and/or challenging information - often involving the identification of new WK & SN Apical Area Ancestors and WK & SN Area Descendants, which was then communicated to the applicant on the Wagyl Kaip and the Southern Noongar Claims (WK & SN Applicant) through the Wagyl Kaip Claim and the Southern Noongar Claim Working Parties. Where the Anthropologist reached a high degree of certainty about a research conclusion and communicated this to the WK & SN Applicant, this resulted in the recognition of new WK & SN Apical Area Ancestors in addition to those described in the native title claim group description for the Wagyl Claim (as it was described in the Federal Court Form 1 that commenced that claim). The group of WK & SN Apical Area Ancestors and WK & SN Area Descendants identified by this extensive and rigorous process of research came to be known (and is described in the Agreement) as the Native Title Agreement Group (NTAG) for the Agreement Area.

(g) Throughout 2013 and the first half of 2014, SWALSC’s Anthropologists focussed on consolidating the research materials to produce a finalised NTAG description for the Agreement Area that was provided to the SSO. Internal reports were produced addressing each WK & SN Apical Area Ancestor, establishing their connection to the Agreement Area. An accompanying genogram showing the Noongar family groups (i.e. WK & SN Apical Area Descendants) who were descended from each WK & SN Area Ancestor were also produced. Where the SSO was unable to identify any WK & SN Apical Area Ancestors based on their materials, extracts of these reports were provided.

(h) On 3 September and 17 September 2014, SWALSC held two “Agreement Information Meetings” for the WK & SN Applicant. These meetings included a presentation of the information underpinning the identification of the WK & SN Area Ancestors and the Agreement Area NTAG, a display of the genograms and information about the proposed process to seek the authorisation of the making of the Agreement in accordance with the requirements of the [NTA].

(i) The NTAG description for the Agreement Area, which defines those who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area, is regarded by the SWALSC Research Section as being as inclusive and accurate as possible.

3.2 It is SWALSC’s opinion, the above efforts represent all reasonable efforts that could, and should, have been made to ensure that all people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area were identified.

47 The Registrar then recorded the assertions of the objectors, noting that many of the objections were either identical or contained similar material and, therefore, were made on similar grounds. The Registrar noted that there was an objection that the research process was deficient, a ground not pursued in the present application. The Registrar also noted the ground which is pursued by the Mackay applicants, namely that SWALSC should have invited to the authorisation meeting, and sought authorisation, from all members of the Noongar community. This was described as the Miller objection, being lodged by Mr Kevin Miller. The Registrar then set out the response to the objections given in 2018 by SWALSC and the Native Title Agreement Group (NTAG), who were described as the group of Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar Apical Area Ancestors and Wagyl Kaip & Southern Noongar area descendants identified by the extensive research by SWALSC’s anthropologists. The Registrar noted (at [65]-[74]):

[65] In the 2018 Response, SWALSC and NTAG make the following assertions and comments in response to the Williams objection:

• SWALSC has not failed to satisfy the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) by including in the NTAG individuals with historical associations to the agreement area. The NTAG differs significantly from the native title claim groups described in the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar claims because of the detailed and expansive research programme undertaken by SWALSC following execution of the Heads of Agreement. This research resulted in identifying more ancestors who had a connection to the agreement area, tracing ancestry of some ancestors back to or at least closer to sovereignty, and showing some ancestors on the Form 1 not having a connection to the agreement area. The objectors do not define what is meant by ‘historical associations’, but if the intent is that some ancestors are not traditional owners but only came to live in the area due to historical factors such as migration and deportation, the assertion is denied. SWALSC made extensive efforts to ensure that all people who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land or waters in the agreement areas as detailed in SWALSC and NTAG’s 2016 Response. Since the lodgement of the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar claims, extensive anthropological research has been conducted to identify all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land and waters within the agreement area. It is submitted that this process, which included the commissioning of an expert anthropological report by Dr Kingsley Palmer that was filed in Court in support of the Single Noongar claim, intensified following execution of the Heads of Agreement with the ‘Agreed Facts’ process and involved SWALSC anthropologists undertaking research to establish genealogical connection of claim group members to the apical ancestors in the agreement area. The sample genealogies were scrutinised by the State’s researchers who provided further information from the State government databases, and after further discussion, negotiation and scrutiny, resulted in final versions agreed upon by SWALSC and State researchers. The Apical Ancestor reports, produced pursuant to the Heads of Agreement, incorporated the findings from the Agreed Facts process and sought to describe the ancestors who, in the authors’ opinion, possessed rights and interests in relation to land and waters within the agreement area at sovereignty on 18 June 1829. The objective of the research programme was to identify those ancestors who were traditional owners of land and waters within the agreement area at sovereignty or settlement by Europeans. It is therefore submitted that the research programme did not result in the inclusion of individuals only with historical association.

• The objectors further assert that the agreement allows for certain classes of people to be incorporated into the NTAG in the future. Traditional Noongar law and custom stipulates that rights to Noongar country can be gained both by lineage (or in some cases marriage, adoption or other links) and by knowledge. SWALSC’s research programme is ongoing and SWALSC remains open to the prospects of supplementing the NTAG where warranted by further information and on the basis that the existing members of the NTAG agree. Nevertheless, it is submitted that the assertions by the objectors are not relevant to the task here.

• The assertion that SWALSC undertook its research programme and developed its amended NTAG ancestor list without consulting the Noongar community is denied. The 2016 Response details the efforts taken by SWALSC to consult with the community including the role of the Working Party in appointing the negotiation team that represented the Noongar people in the Settlement negotiations, the Working Party and applicant meetings held to consider the progress of the negotiations, the extensive community information programme undertaken by SWALSC from 2013 at which apical ancestor updates were given, and updated description of the claim groups published on SWALSC’s website from October 2014. The objectors were also either a Director of SWALSC, member of the Noongar Negotiation Team, appointed to the Working Party as family representatives or a member of the applicant for the Wagyl Kaip claim who also executed the agreement in this capacity, indicating that they were privy to information about the Settlement. The objectors should have raised these matters in the community information sessions and the authorisation meeting to persuade others to vote against the authorisation of the agreement, but did not and instead were ‘championing’ the agreement.

[66] As indicated above, SWALSC and NTAG also rely on their 2016 Response which provides information in relation to the efforts taken to meet the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a), which are outlined in my reasons below.

[67] SWALSC and NTAG submit that efforts parties to a proposed ILUA can take to identify, and invite to participate in negotiations, persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the proposed ILUA area include:

• contacting the NNTT for assistance with searches;

• publicly advertising the intention to commence negotiations in a variety of media as well as sending personal notice to known claim groups in the proposed area;

• inviting people who hold or may hold native title to attend information sessions and consultations about the proposed ILUA; and

• making other reasonable inquiries that can include the commissioning of anthropological research.

[68] It is submitted that the inquiries made for the Settlement ILUAs ‘were either the same as, or certainly were supported and strengthened by, those made by SWALSC in the exercise of its statutory NTRB functions, including those under ss.203BB(1)(a) and 203BJ(b) of the’ Act, which are summarised at [3.1] in the certification. It appears from the certification that the efforts made were both expansive and inclusive, and incorporated:

• ‘extensive public notification and other efforts to advertise the proposed ILUA processes to as broad a pool of prospective native title holders as possible, with a view to inviting all who might consider themselves to be “Other Claimants” to contact SWALSC with any information they had (including as to their apical ancestors) connecting them to the proposed Agreement Areas’;

• requesting NNTT assistance with geospatial data searches and other research into historical and current claims, both registered and unregistered, across the Settlement Area; and

• a comprehensive, wide-ranging and detailed program of anthropological, ethno-historical and genealogical research to identify the people who hold or may hold native title in relation to the whole of the Settlement Area.

[69] SWALSC and NTAG contend that the research program has:

• supplemented understanding of the claim groups for each Noongar claim;

• enabled development of a set of agreed facts for the registered Noongar claims and the Single Noongar claims;

• resulted in greater knowledge of those who hold or may hold native title in the area for each of these Noongar claims; and

• resulted in a reformed set of ancestor lists for all Noongar claims in question.

[70] SWALSC and NTAG say that between March and June 2012, the NNTT provided assistance and advertised the apical ancestor lists for the registered Noongar Claims nationally, in an effort to identify those people who may not currently be included in the membership of the applicable native title claim group. The NNTT received a total of 401 inquiries, with eight providing additional information on ancestors not listed. Of these, three had already been identified by SWALSC researchers for inclusion, two more needed to be added and, of the remaining three, there was either insufficient evidence to include them as an apical ancestor, and/or their descendants were already included through other apical ancestors.

[71] SWALSC and NTAG submit that specific connection research, undertaken in accordance with a process agreed with the State following the execution of the Heads of Agreement in late 2009, required reading and analysing all available sources of information relevant to each agreement area in an effort to determine the identity of:

• the Aboriginal people who (before 1829) by the traditional laws they acknowledged and the traditional customs they observed, had a connection to each Agreement Area, and held rights and interests in relation to the land or waters in each Agreement Area that were possessed under such traditional laws and traditional customs; and

• the descendants of these ancestors.

[72] The certification provides details of the extent of this anthropological research program as well as the rigour with which it was conducted, resulting in the anthropologist reaching a high degree of certainty as to the identity of apical ancestors not currently listed on the application filed in respect of each Noongar claim, and the descendants of these ancestors. This finding was then communicated to the applicant on the relevant Noongar Claim.

[73] SWALSC and NTAG say that the groups of ancestors and descendants identified by this research are the NTAGs for the agreement areas, and that the description of the NTAG for each agreement area represents ‘the most anthropologically accurate formulation currently achievable of the people who hold or may hold native title rights and interests in relation to each Agreement Area’.

[74] It is contended that ‘SWALSC’s expansive and inclusive approach to identification meant that, whether or not they were also members of the NTAG, people were identified as people who hold or may hold native title in each Agreement Area if they were members of … registered and unregistered Noongar Claims that overlapped with the Agreement Area’. SWALSC and NTAG further submit that ‘by any measure and notwithstanding Objections made (without giving particulars) to the effect that SWALSC had made insufficient and misconceived efforts to satisfy the Identification Requirement, the efforts made to identify the people who hold or may hold native title in each Agreement Area must be regarded as having been reasonable’.

(Citations omitted.)

48 Some of the objectors asserted that the research efforts were flawed and they strongly contended that the outcome and process undertaken by SWALSC did not identify the “right people for country” and SWALSC had only showed traditional owners contempt and deceit throughout the process.

49 The Registrar commenced her consideration of the two s 203BE(5) requirements by noting that there is no definition in the NTA of what constitutes “all reasonable efforts” in the context of s 203BE(5)(a). She noted the responsibility of the representative body to not certify an application for registration of an ILUA unless it is of the opinion that “all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by an agreement have been identified”. The Registrar was of the view that “all reasonable efforts” should take into account the particular facts and circumstances. It was a question of fact, as noted by White J in Bright, to be determined by the particular circumstances of the given case.

50 White J’s discussion of the expression in Bright (at [131]-[133]) was then cited, which included the following observations:

Section 203BE(5) “does not oblige the representative body itself to make the requisite reasonable efforts” (at [131]).

It can form an opinion required for its certification on the basis of efforts made by others (at [131]).

Section 203BE(5) does not contain any temporal specification with respect to the required efforts (at [132]).

Section 203BE(5) of the NTA did not require that all persons who hold or may hold native title in the area in question have been identified, but only that the representative body be of the opinion that all reasonable efforts had been made to ensure that they had been identified (at [132]).

51 The meaning of the expression “persons who hold or may hold native title” in light of explanation of Reeves J in QGC Pty Ltd v Bygrave (No 3) (2011) 199 FCR 94, and his Honour’s observation for the need for an expansive and inclusive approach, was noted by the Registrar. She understood that she was not required to consider whether all potential native title holders had been identified or whether she agreed with the views formed by the representative body about “all persons who hold or may hold native title” in relation to the land and waters covered by the agreement area. Rather, it was whether the material showed that the representative body’s views were shaped as a consequence of reasonable efforts (at [81]). To satisfy her that all reasonable efforts had not been made would require the objectors to show that SWALSC’s efforts to ensure all persons who hold or may hold native title in the area had been identified were wanting such that the efforts and subsequent views could not be said to be reasonably based (at [81]).

52 The Registrar did not consider her task was to speculate about the correctness or otherwise of the anthropological research results, but noted (at [84]) that the material to which she referred demonstrated that SWALSC had manifestly investigated the persons who hold or may hold native title in the areas through extensive research. She concluded the objectors had not satisfied her that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) of the NTA were not satisfied.

53 Importantly to these applications and in relation to the second requirement, namely, authorisation under s 203BE(5)(b) of the NTA, the Registrar noted (at [95]) that in addition to the information referred to above, the certificate by SWALSC included the following information:

Notice of Authorisation Meeting – Proposed Agreement

4.4 In order to give all of the people identified as people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area a reasonable opportunity to make an informed decision about whether to attend the Agreement Authorisation Meeting and to participate in the authorisation processes for the Agreement, it was necessary to advertise and broadcast the intention to hold the Agreement Authorisation Meeting to as many of such people as was practicable.

4.5 To this end, SWALSC caused a Formal Notice of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting to be prepared - for wide distribution in a broad range of newspapers, including in several newspapers of State-wide and regional circulation and in a national newspaper catering mainly or exclusively for the interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders. This Formal Notice provided comprehensive details and information about the location, date, time, logistics and purpose of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting. The Formal Notice also gave a comprehensive description of those people (as to whom, see paragraph 4.1 above) who, to that point, had been identified as people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area. These people were collectively referred to in the Formal Notice as the “Identified Native Title Group”. It also invited anyone else who considered that they held native title to the area to contact SWALSC.

4.6 SWALSC caused a full page advertisement of the Formal Notice to be placed in:

(a) the Koori Mail on Wednesday, 14 January 2015 and Wednesday, 28 January 2015;

(b) the Weekend West (West Australian) on Saturday, 24 January 2015; and

(c) the Albany Advertiser on Thursday, 5 February 2015 and the Great Southern Herald on Thursday , 5 February 2015.

4.7 The Formal Notice for the Agreement Authorisation Meeting was supported by a General Reminder Notice, which SWALSC caused to be placed in:

(a) the Weekend West (West Australian) on Saturday, 14 February 2015;

(b) the Great Southern Herald on Thursday, 19 February 2015; and

(c) the Albany Advertiser on Thursday, 19 February 2015.

4.8 The Formal Notice and General Reminder Notice were supported by a General Notice that was very widely distributed in State-wide, regional and Aboriginal special interest newspapers. The General Notice, which was in the form of a Schedule of the Authorisation Meetings for all of the Settlement ILUAs, included the details for the Agreement Authorisation Meeting. SWALSC caused advertisements of the General Notices to be placed and to appear in:

(a) the Koori Mail on Wednesday, 17 December 2014 and Wednesday, 14 January 2015;

(b) the Weekend West (West Australian) on Saturday, 13 December 2014;

(c) the Countryman on Thursday, 8 January 2015;

(d) various metropolitan community newspapers from 6 to 9 January 2015;

(e) the Great Southern Herald, Narrogin Observer and Manjimup-Bridgetown Times on Wednesday, 7 January 2015;

(f) the South Western Times, Central Midlands & Coastal Advocate on 15 January 2015 and Albany Advertiser on Thursday, 8 January 2015;

(g) the Busselton-Dunsborough Times on Friday, 9 January 2015;

(h) the York & Districts Community Matters on Friday, 9 January 2015; and

(i) the Harvey-Waroona Reporter on Tuesday, 13 January 2015.

4.9 This extensive advertising of both the Formal Notice and General Notice advertisements were supported by a program of information about the Authorisation Meetings for all of the Settlement ILUAs to further ensure that the Identified Native Title Group had the opportunity to become aware both of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting and of the Authorisation Meetings for all of the other Settlement ILUAs. The program of information was caused to be implemented by SWALSC to maximize coverage using varied media and forms of communication, including the SWALSC website, social media, mail out of letters (using a database of known addresses) to SWALSC Members, an Authorisation Meeting pre-registration program and a telephone contact program. This program was supported by an extensive Noongar community “face to face” information meeting program prior to and leading up to the Authorisation Meeting.

4.10 In this regard, SWALSC caused:

(a) a schedule of details of the six Settlement ILUA Authorisation Meetings, including the Agreement Authorisation Meeting, to be posted to the SWALSC website from 12 November 2014 and to be given out at Community Information Meetings;

(b) a mail out on 18 August 2014 of an information package on the South West Settlement (using a database of known addresses) to SWALSC Members. This information package included copies of the “Summary Guide to the Settlement Documents” and the “Quick Guide to the Settlement”, copies of both which were also posted to the SWALSC website, as well as of the General Notice and Schedule of all six Authorisation Meetings. Importantly, this information included details both of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting and of the Authorisation Meeting pre-registration program;

(c) the implementation and promotion of an Authorisation Meeting pre-registration program from August 2014, giving an early opportunity for Noongar people to identify eligibility to attend the Agreement Authorisation Meeting. Promotion of the program was carried out through General Notices, social media posts, mail out to SWALSC Members and by “face-to-face” consultation at Family and Community meetings;

(d) the undertaking of a telephone contact program, which commenced on 4 December 2014, to provide details of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting, including of the Identified Native Title Group for the Agreement. Members of the Identified Native Title Group were given the opportunity to pre-register up until 6 February 2015, as provided in the Formal Notice;

(e) radio announcements providing details of all of the Settlement ILUAs and associated Authorisation Meetings to be made on Noongar Radio and Koori Radio between 6 January 2015 and 29 January 2015;

(f) meetings of the South West Claims Working Party and Named Applicants Meetings to be convened in accordance with its functions under the [NTA] and consistently with meetings convened since the commencement of those claims - in particular between 2010-2014, providing extensive updates on the South West Settlement process including details about the Agreement Authorisation Meeting process (and Authorisation Meeting details); and

(g) a meeting of all of the South West Claims Named Applicants (including the WK & SN Applicant) to be called and convened on Wednesday, 17 December 2014. The meeting provided information on the proposed Settlement ILUAs (including the proposed Agreement), the role of the Applicant for each Noongar Claim and details of the proposed Authorisation Meetings (including the Agreement Authorisation Meeting to be held on Saturday 21 February 2015).

Authorisation Meeting - Proposed Agreement

4.11 SWALSC has undertaken and commissioned substantial preparation, planning and legal services to meet the requirements under s.251A of the [NTA] with respect to the proposed Authorisation of the making of the Agreement. This preparation included the establishment of an Authorisation Plan and Authorisation Meeting procedures.

4.12 The people present at the Authorisation Meeting for the proposed Agreement were verified for eligibility to participate in the authorisation process as members of the Identified Native Title Group by applying the relevant procedure (as described below) to enable their entry to, and participation in, the Agreement Authorisation Meeting.

4.13 SWALSC arranged for the Agreement Authorisation Meeting to be facilitated by a person independent of SWALSC. In addition, independent Legal Counsel (a QC) attended the Agreement Authorisation Meeting to provide independent legal counsel and advice. Finally, an independent person acted as Returning Officer to officiate the decision-making process of the Agreement Authorisation Meeting.

4.14 During the Agreement Authorisation Meeting, the independent Facilitator convened an information session, to provide an opportunity for the meeting attendees to be given information about the South West Settlement and the proposed Agreement, and a question-and-answer session, to provide an opportunity for people to participate in discussions in an open forum. Discussions were facilitated to ensure that as many participants had an opportunity to speak, express their views and ask questions on the South West Settlement process generally, and the proposed Agreement in particular.

4.15 Also during the Agreement Authorisation Meeting, meeting attendees had the opportunity to seek independent legal advice. It was observed that a number of people approached the independent Legal Counsel to seek his advice, both formally and informally.

4.16 The members of the Identified Native Title Group present at the Agreement Authorisation Meeting engaged in a full discussion on the requirements for the adoption of a decision-making process for the proposed authorisation of the Agreement - be that a mandatory traditional process under section 251A(a) of the [NTA] or an agreed and adopted process under section 251A(b). As well as the detailed discussion, meeting attendees had the benefit of an address by the independent Legal Counsel in relation to the relevant requirements. It was acknowledged that the members of the Identified Native Title Group in attendance at the Authorisation Meeting:

(a) had been identified as people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area; and

(b) included people who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising such native title.

4.17 Following the discussion and address mentioned in paragraph 4.16 above, proposed Authorisation Resolution 1 was read out to the Authorisation Meeting (a copy of the final Authorisation Resolutions is attached at Annexure A to this document). A majority of the members of the Identified Native Title Group present at the Agreement Authorisation Meeting subsequently voted by a show of hands to pass Resolution 1.

4.18 By passing Resolution 1 in its entirety, the members of the Identified Native Title Group present at the Agreement Authorisation Meeting:

(a) confirmed that the Agreement Authorisation Meeting was a proper meeting of the Identified Native Title Group, of which they were satisfied that adequate notice was given;

(b) confirmed that there was no particular process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the people who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title in relation to the Agreement Area, must be complied with in relation to authorising such things of the making of the proposed Agreement;

(c) in the absence of any such process, agreed and adopted (in relation to making a decision about authorising such things as the making of the proposed Agreement) a decision-making process constituted by majority decision by secret ballot of all of the meeting attendees; and

(d) agreed and acknowledged that:

(i) a decision made in accordance with this agreed and adopted decision-making process will be taken to be a decision of all of the people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area; and

(ii) no person will have a right to challenge or veto a decision made in accordance with that process.

4.19 A full discussion was then held on the main resolution, Resolution 2, in its entirety.

4.20 Following the discussion mentioned in paragraph 4.19 above, Resolution 2 was read out to the Agreement Authorisation Meeting - again, in its entirety.

4.21 Resolution 2 was moved, seconded and passed by an overwhelming majority by secret ballot by the attendees at the Agreement Authorisation Meeting. In accordance with the process of decision-making agreed and adopted by the passing of Resolution 1, the effect of this majority decision to pass Resolution 2 is that all of the people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area must be taken to have (among other things):

(a) authorised the making of the Agreement;

(b) authorised and directed the people comprising the applicant on each of the native title determination applications mentioned in paragraph 3.1(a) above, as well as any other members of the Agreement Area NTAG who wish to do so, to sign the Agreement as Representative Parties for all of the people who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area;

(c) agreed to, and promised to support, the State making an application to have the Agreement registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements; and

(d) acknowledged and confirmed their understanding that such registration of the Agreement is intended ultimately to result in:

(i) the surrender to the State of all native title rights and interests that might exist in relation to land or waters in the Agreement Area; and

(ii) the applicant for each of the native title determination applications mentioned in paragraph 3.1(a) above seeking the making by the Federal Court of one or more determinations that native title does not exist in relation to the area within the external boundaries of each such application.

4.22 Following the Agreement Authorisation Meeting, SWALSC caused letters to be sent to each member of the WK & SN Applicant providing details regarding the execution of the Agreement. A majority of the people comprising the WK & SN Applicant have signed the Agreement, with the last of such people executing the Agreement on 2 April 2015.

4.23 SWALSC has also caused letters to be sent to the members of the applicant for the Single Noongar Claim inviting those of them who wished to be named as Representative Parties to sign the Agreement.

…

(Emphasis added.)

54 The Registrar then sets out the resolutions, Resolution 1 and Resolution 2, referred to above. Resolution 1 (also referred to as the First Resolution) provided the decision-making process for the authorisation of the ILUA (on the basis that there was no applicable traditional decision-making process). Resolution 2 (also referred to as the Second Resolution) provided for the authorisation of the ILUA in accordance with that process. It is to be noted that what is recorded in 4.21 above in respect of the manner in which Resolution 2 was passed varied from meeting to meeting as to whether done by secret ballot count or show of hands and as to the extent of the majority.

55 The Registrar then recorded the assertions of the objectors, noting:

[96] I understand the objectors also assert that not all persons identified as holding or who may hold native title in the area covered by the agreement authorised the making of the agreement. In particular, the objectors assert that a reasonable opportunity was not provided to participate in the adoption of a particular process, making decisions pursuant to that process and/or the conduct at the meeting and that the specific process of authorisation of the agreement was flawed. As indicated earlier in my reasons, many of the objections were either identical or contained similar material and therefore were made on similar grounds. Rather than restating each ground, I provide the following summary of each. In particular:

• The meeting attendees were misinformed about the requirements of the authorisation meeting resulting in the adoption of an incorrect decision-making process instead of one that allowed vote by post or proxy, that denied many native title holders the ability to participate in the authorisation process.

• There was no attempt to distinguish who was entitled to participate in either of the two-step decision-making process required by s 251A, namely a decision to determine the authorisation process and a decision about whether the agreement should be authorised, and in fact the same individuals were permitted to vote on each issue.

• Not all the persons who hold or may hold native title in the agreement area were given an opportunity to attend or participate, such as due to being incarcerated in prison, distance of the authorisation meeting, travel arrangements or failure to accommodate voting by proxy or postal vote, resulting in insufficient attendance.

• No alternative and impartial view was provided apart from those in support of the agreement.

• Intimidation and/or inappropriate/biased behaviour by SWALSC staff, security, police and/or other groups, such as in relation to voting in favour of the agreement.

• The voting process was unclear.

• A traditional decision-making process that decisions are to be made by elders, was required to be followed but was not and/or comments about the decision-making process were ignored.

• A predetermined secret ballot/voting process was imposed or based on the minority.

• A reasonable opportunity to be heard at the meeting was not provided, such as the microphone being turned down for some attendees and comments were ignored.

(Citations omitted.)

56 The Registrar recorded (at [97]) the response from SWALSC and NTAG in their 2018 response as follows:

• Responding to the Miller objections, it is asserted that:

- The objector says that many of the people who have authorised the making of the agreement are the wrong people to speak for country. It is noted that SWALSC took extensive steps, as described in the 2016 Response, to ensure that all the persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the agreement area were identified, including undertaking a rigorous research programme which was scrutinised and informed by, and agreed with the State.

- The objector was not excluded as he was a registered attendee at the authorisation meetings for the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar ILUA and Whadjuk ILUA. The objector also attended the South West Boojarah #2 ILUA authorisation meeting where he spoke briefly against the Settlement and then chose to leave.