FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Chi Cong Le v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCAFC 178

ORDERS

NSD 492 of 2019 | ||

Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the first respondent’s costs as agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 This is an appeal from orders made by a judge of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia by which an application for judicial review of a decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal was dismissed. The Tribunal had affirmed a decision of a delegate of the first respondent, the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, to cancel the appellant’s Class BS (Subclass 801) (Partner) visa.

Introduction

2 Visa applicants are required to answer all questions and to give or provide correct answers in their visa application forms: Migration Act 1958 (Cth), s 101. An answer to a question is incorrect even if the applicant did not know that it was incorrect: s 100. A visa applicant must, as soon as practicable, inform an officer of the Department (being the Department responsible for the Migration Act per s 19A of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth)) in writing of any new circumstances that make an answer in a visa application form incorrect, and advise what the correct answer is: s 104. If an applicant becomes aware that an answer in a visa application form is incorrect, he or she must, as soon as practicable, notify an officer of the Department of that incorrectness and of the correct answer: s 105. Each of those obligations is not affected by the fact that the Minister or an officer had access to any information: s 106.

3 Section 107 provides that the Minister may give notice of an intention to cancel a visa for non-compliance with, inter alia, the s 101 obligation to give correct answers, so that the visa applicant has an opportunity to address the alleged breach. Any response must be considered: s 108. A visa can only be cancelled upon s 101 grounds for an act of non-compliance identified in the s 107 notice: s 109. Sections 107, 108 and 109 apply whether the non-compliance was deliberate or inadvertent: s 111.

4 A notice under s 107 does not preclude a further notice asserting a different act of non-compliance; and non-cancellation, despite an act of non-compliance, does not preclude cancellation for a different act of non-compliance: s 112.

5 In the present case, no issue has been raised concerning the form or content of the s 107 notice given to the appellant. The issue arising out of that notice is whether the same answer given in two visa application forms to substantially the same question was incorrect.

6 The appellant applied for, and was granted, a succession of three visas, filling out the requisite form for each:

(1) on 10 November 2009, he was granted a Prospective Spouse (subclass 300) visa;

(2) on 16 March 2010, he was granted a temporary Partner (subclass 820) visa; and

(3) on 3 April 2012, he was granted a permanent Partner (subclass 801) visa.

7 In the application forms for the first visa, the appellant was asked (at question 77):

If you are in a de facto spouse, fiancé(e) or interdependent relationship, are you related to your partner by blood, marriage or adoption?

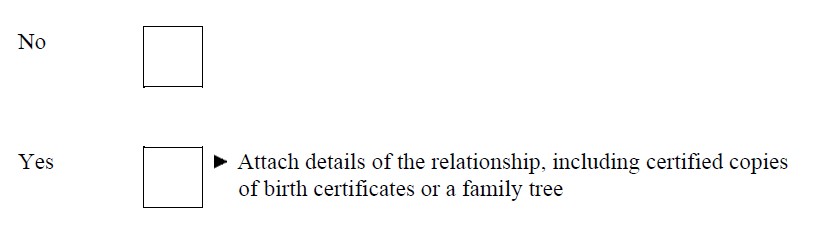

8 In the application for the second visa, substantially the same question was asked (at question 76): “If you are in a de facto or fiancé(e) relationship, are you related to your partner or fiancé(e) by blood, marriage or adoption?” That question was accompanied by the same two boxes for the appellant to indicate his response, reproduced above. The question 77 in the first visa application form and question 76 in the second visa application form may conveniently be described as the relationship question. The appellant ticked the “No” box in both visa application forms in answer to the relationship question. It was common ground before the primary judge that his sponsor was his first cousin, because their respective mothers were sisters.

9 On 24 August 2016, a delegate of the Minister sent a notification of intention to consider cancellation under s 109 of the Migration Act. Amongst other information, the s 107 notice referred to the appellant ticking the “No” box on both visa application forms in response to the relationship question. The notice stated that this constituted incorrect information because the appellant had “not declared the blood relationship between yourself and your sponsor” and advised that his permanent visa was therefore liable for cancellation.

10 In response to the s 107 notice, the appellant’s migration agent made submissions in writing to the effect that the answer “No” to the relationship question was not incorrect. This was not accepted by the delegate, who cancelled the appellant’s permanent visa. The appellant’s stance that the answer “No” to the relationship question was correct was maintained before the Tribunal and the primary judge, and is maintained on appeal, albeit with some greater degree of sophistication than at the Tribunal and judicial review stages.

11 The Tribunal found that the correct answer to the relationship question was “Yes” and that therefore the answer “No” constituted non-compliance with the s 101(b) obligation that “no incorrect answers are given or provided”. The primary judge found no error on the part of the Tribunal. The central issue that was before the Tribunal and the primary judge, and is now before this Court, is the meaning of the phrase “are you related to your partner [or fiancé(e)] by blood”.

12 A further issue before the primary judge and on appeal was whether there was a jurisdictional error by the Tribunal in failing to advise the appellant about documents thought to be covered by a certificate under s 375A of the Migration Act. It was common ground that the Tribunal was incorrect to proceed upon the basis that the certificate was valid. In fact, the certificate was invalid because the formal requirements of s 375A(1)(a) were not met. The importance of this is that the appellant was entitled to have access to, or a copy of, any written material that was before the Tribunal unless, relevantly, s 375A applied to the material: s 362A(1). The appellant was not provided with a copy of those documents until some time after the Tribunal had affirmed the delegate’s decision.

13 The Tribunal (at [10]) expressly stated that the certificate was valid and that the documents to which the certificate (purportedly) related were “not relevant to whether the [appellant] answered the questions on the visa application form correctly” and made no further reference to those documents or their contents.

Before the Tribunal

The relationship question

14 On the topic of whether the answer “No” to the question “are you related to your partner by blood” was incorrect, the Tribunal, after considering submissions made on behalf of the appellant, said (at [42]-[46]):

[42] In this case the wording of the question casts the net wider in that it includes other people to whom the applicant is “related by blood”. It does not ask whether the person is a “relative” of the sponsor and provide a definition of the term relative. The term “related by blood” is not defined in the Act whereas the term “relative” is defined. In using this term the legislature included a broader category of people in specifically stating it in this way. The Tribunal considers this was done for a specific purpose. However in phrasing the question in this way, the Tribunal considers that it also introduced a degree of ambiguity as the term, ‘related by blood’, can include very distant relatives, which could go to the point of absurdity.

[43] The Tribunal considers that the use of the term “related by blood”, while it may have been designed to widen the scope of people to be taken into consideration, lacks clarity in that it is a broad category, which is also not defined in the Act and therefore it is unclear what the correct response to the question should be. However, the Tribunal considers that the form of the question requires the applicant to disclose the existence of any known blood relationship no matter how distant. In most cases where this was a distant relationship this would then be considered as not relevant to the decision whether or not to grant the visa.

[44] In considering whether or not the applicant gave the correct answer to the question asking him whether he was related by blood to [his] sponsor, the Tribunal has taken into consideration the fact that in this case the applicant was very closely related to the sponsor. Their mothers were siblings. The applicant gave evidence at the hearing that he was not aware of the relationship although as stated above, the Tribunal does not find this to be credible. The Tribunal considers this is something he would have been well aware of and, while it would not have automatically precluded him from being granted the visa, it would have indicated to the Department that it may need to investigate the relationship more fully.

[45] The Tribunal considers that had the applicant declared on the application form that he was related by blood to the sponsor, and that in fact they were first cousins, the Department may have had reason to examine whether or not the relationship was genuine more fully. The Tribunal considers as they were first cousins living in the same village for several years, it is unlikely that they would have met each other in the years before the sponsor moved to Australia. The Tribunal considers that the applicant did not declare his blood relationship with the sponsor because he did not want the Department to investigate the genuineness of the relationship in more detail.

[46] For these reasons, the Tribunal finds that there was non-compliance with s 101(b) by the applicant in the way described in the s.107 notice.

15 Having decided that there was non-compliance by the appellant with s 101(b), the Tribunal turned to the question of whether the discretion to cancel his visa should be exercised under s 109. The Tribunal noted that it was required to consider any response to the s 107 notice in respect of non-compliance and have regard to any prescribed circumstances: s 109(1)(b) and (c). The Tribunal listed the circumstances prescribed for the purposes of s 109(1)(c) in reg 2.41 of the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth), being:

(a) the correct information;

(b) the content of the genuine document (if any);

(c) whether the decision to grant a visa or immigration clear the visa holder was based, wholly or partly, on incorrect information or a bogus document;

(d) the circumstances in which the non-compliance occurred;

(e) the present circumstances of the visa holder;

(f) the subsequent behaviour of the visa holder concerning his or her obligations under Subdivision C of Division 3 of Part 2 of the Act;

(g) any other instances of non-compliance by the visa holder known to the Minister;

(h) the time that has elapsed since the non-compliance;

(j) any breaches of the law since the non-compliance and the seriousness of those breaches;

(k) any contribution made by the holder to the community

16 The Tribunal noted that while the above list was mandatory, it was not exhaustive, citing authority to that effect. The Tribunal went through each of the prescribed circumstances as were found to be applicable, finding in relation to the correct information (at [50]):

In this matter the Tribunal is satisfied that, in stating on his application forms for the 300 prospective spouse visa and on the 820 partner visa that he was not related by blood to the sponsor, the applicant did not give or provide correct information to the Department and accordingly breached s 101(b). In doing so, the applicant failed to give information to the Department which may have caused it to examine the genuineness of the relationship in greater detail in determining whether to grant the visa. While the information provided was not directly relevant to the grant of the visas, it was relevant in that the Department may have examined the issues involved in the application more fully and possibly decided to refuse the visas.

17 After considering a range of other circumstances, the Tribunal concluded (at [64]):

The Tribunal has decided that there was non-compliance by the applicant in the way described in the notice given under s.107 of the Act. Further, having regard to all the relevant circumstances, as discussed above, the Tribunal concludes that the visa should be cancelled.

The s 375A certificate

18 On the topic of the certificate under s 375A, the Tribunal said during the course of the hearing, (at page 3 of the transcript, lines 40-47):

Now, before I proceed any further, Mr Representative, there is a certificate on a number of documents on the department file, and that’s a certificate under section 375A. The first group of certificate[s] contains information relating to internal procedures and third party information in internal procedural documentation. I find that that certificate is valid and therefore they can’t be released to the applicant. However, anything that I refer to in those documents I will specifically address, if I do need to refer to them.

19 In its reasons, the Tribunal stated (at [10]):

At the start of the hearing the Tribunal advised the applicant’s representative that there is a certificate under section 375A of the Act on the folios in the Department file. The certificate states that the information on these folios relates to internal Department procedures and third-party information. The Tribunal is satisfied that the certificate is valid but that the information in these folios is not relevant to the matter. The documents relate to Departmental procedures and third parties and are not relevant to whether the applicant answered the questions on the visa application form correctly.

20 The Tribunal made no other reference to the documents referred to in the s 375A certificate.

21 It is common ground that the s 375A certificate was invalid. The appellant had earlier requested access to documents in accordance with s 362A(1), which included the documents referred to in the invalid s 375A certificate that were not provided. The appellant asserted before the primary judge, and continues to assert on appeal, that failure to provide him with access to the documents referred to in the s 375A certificate was a jurisdictional error.

Before the primary judge

The relationship question

22 On the topic of whether the answer “No” to the question “are you related to your partner [or fiancé(e)] by blood” was incorrect, the primary judge said (at [14]-[20], challenged paragraph emphasised):

[14] The Tribunal noted that the relevant questions did not ask the applicant whether he was a “relative” of his sponsor. As stated above, that term is defined and does not include first cousins. The Tribunal found that the wording of the question casts the net wider in that it includes other people to whom the applicant is related by blood, other than those defined as ‘relatives’.

[15] The Tribunal found the question required the applicant to disclose the existence of any known blood relationship no matter how distant. The Tribunal found that where a distant relationship existed, that distance would be considered as not relevant to the decision of whether or not to grant the visa. The Tribunal found that where the relationship was as close as first cousins, and was a fact about which the Tribunal found the applicant was aware, answering, Yes, would have indicated to the Department that it may need to investigate the relationship more fully. The Tribunal stated that being first cousins did not automatically preclude the applicant from being granted the visa.

[16] However, no absurdity arises in the case before this Court.

[17] In my view, the Tribunal was correct to find that an applicant who knew that he was the first cousin of the sponsor provided an incorrect answer to the question, “Are you related to your partner by blood”, when he answered, “No”.

[18] The Tribunal found that the applicant did not declare his blood relationship with the sponsor because he did not want the Department to investigate the genuineness of the relationship in more detail. The Tribunal made those findings in the context of acknowledging in certain circumstances the term “related by blood” could be extended to the point of absurdity, such that it would be unclear as to what the correct response might be.

[19] The Tribunal’s rationalisation that it may well be relevant to the Department in considering the genuineness of a relationship to have regard to the closeness of that relationship, without it meaning an automatic preclusion from the granting of the visa, is correct.

[20] In the circumstances, the Tribunal’s findings were open to it for the reasons it gave and are without error.

The s 375A certificate

23 On the topic of the s 375A certificate, the primary judge concluded (at [35]-[39], challenged paragraphs emphasised):

[35] The rationale of the Tribunal’s exercise of discretion appears to be in the applicant’s failure to give information to the Department which may have caused it to examine the genuineness of the relationship in greater detail in determining whether to grant the visa. As stated above, the Tribunal itself did not proceed to consider the genuineness of the relationship or whether it was contrived in any way. The Tribunal concluded in stating as follows:

“64. The Tribunal has decided that there was non-compliance by the applicant in the way described in the notice given under s.107 of the Act. Further, having regard to all the relevant circumstances, as discussed above, the Tribunal concludes that the visa should be cancelled.”

[36] The Tribunal clearly stated that it confined the relevant circumstances to those it discussed in its decision.

[37] The Court is entitled to take the Tribunal at its word in assuming that if there was anything in the s.375A documents, that the Tribunal “specifically address” those with the applicant. The information contained in the documents was not ultimately relevant to the rationale which the Tribunal applied in exercising its discretion to cancel the applicant’s visa.

[38] Accordingly, I find that the Tribunal’s breach in failing to give the applicant an opportunity to comment on the information was not a material breach and that the disclosure of the documents would not have resulted in a different decision, having regard to the way in which the Tribunal framed its decision.

[39] I am satisfied there is not a realistic opportunity that the Tribunal’s decision could have been different if the documents had been disclosed so as to allow the applicant to provide submissions for those reasons.

24 On the related topic of the failure of the Tribunal to comply with s 362A of the Migration Act by failing to give him access to the documents referred to in the invalid s 375A certificate, the primary judge found that this did not constitute a jurisdictional error as alleged. Her Honour concluded (at [42]-[45], challenged paragraph emphasised):

[42] The applicant relied on Sandhu v Minister for Immigration (2015) 236 FCR 63 (“Sandhu”) where Logan J found a breach of s.362A of the Act per se would amount to jurisdictional error.

[43] However, the applicant acknowledged in the more recent case of Singh v Minister for Immigration [2017] FCA 1443 at [138], Siopis J read Sandhu as qualified by the observations of the Full Court of Minister for Immigration v Dhillon (2014) 227 FCR 525 (Allsop CJ, Murphy and Pagone JJ). In Dhillon at [15], the Court found that s.362A of the Act would be breached only in circumstances where access might reasonably have affected the decision of the Tribunal.

[44] For the same reasons I gave in determining that there was no denial of procedural fairness in failing to give the applicant the information in the documents covered by the s.375A certificate, Ground 5 must fail.

[45] In short, the Tribunal’s disavowance of any reliance on the documents, its failure to mention the documents and its failure to raise any issue to which they may be relevant, has the result that, had the documents been produced under s.362A of the Act, they could not have reasonably affected the decision of the Tribunal.

The grounds of appeal

25 The notice of appeal contains the following three grounds:

1. The Federal Circuit Court erred at [17] by finding that an applicant who knew that he was the first cousin of a sponsor provided an incorrect answer to the question “Are you related to your partner by blood”, when he answered “No”, thereby engaging the visa cancellation provisions in sections 101, 107, 108 and 109 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act).

2. The Federal Circuit Court erred at [37]-[39] by finding – in circumstances where documents before the second respondent were subject to a certificate under s 375A of the Act and not therefore provided to the appellant – that there had been no error by the second respondent because the documents were not material to the decision under review.

3. The Federal Circuit Court erred at [45] by finding – in circumstances where documents before the second respondent were the subject of a request by the appellant under s 362A of the Act but not provided to the appellant – that there had been no error by the second respondent because the requested documents were not material to the decision under review.

Ground 1

Competing arguments

26 The appellant submits that, although application forms are not legislative instruments (citing AIU17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCA 520 per Allsop CJ at [32]-[33]), it is nevertheless appropriate to consider the meaning of questions in approved forms in the context of the enactment under which approval has been given and by reference to the usual rules of statutory interpretation. Taking that approach, the appellant suggests several principles of statutory construction, detailed below, which he contends, in combination, demonstrate that the phrase “related to your partner by blood” is directed to whether the applicant is in a marriage that would be recognised in Australia. Section 23(1)(b) of the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth), makes void any marriage within a “prohibited relationship”, defined in s 23(2) as marriages between a person and an ancestor or descendent of the person, or between a brother and sister (including half siblings). The appellant therefore submits that because first cousins are not in a prohibited relationship, the correct answer to the question was indeed “No”.

27 In reaching the above conclusion, the appellant acknowledges that the plain meaning of “related by blood” suggests that first cousins would fall within the description, because the dictionary definition of “blood relation” is “a person related to another by birth or consanguinity; a kinsman. Hence blood relationship, consanguinity, kinship”: English Oxford Dictionary (Second Edition: 1989). The word “consanguinity” is defined as “the condition of being of the same blood; relationship by descent from a common ancestor; blood relationship”. However, the appellant submits in relation to the phrase “related to your partner by blood”:

(1) If all the words in the phrase are to be given meaning and effect, the words “to your partner” must be considered in the context of an application for a partner visa. Thus, he argues, the question posed by the phrase is not just directed to the question of being related by blood. Rather, by analogy, the approach of Perry J in Salama v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCA 2 at [60]-[61] should be applied. Her Honour interpreted an ambiguous reference to the word “married” in an online application form for a partner visa with reference to a “pop-up” explanation of that word, as well as its context in the definition of “spouse” and “married relationship” in the form as being directed to the requirements for a valid marriage under the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth).

(2) The context of the relationship question in the Form 47SP (by which the appellant applied for the first Prospective Spouse (subclass 300) visa also suggests that the question is directed to whether a visa applicant is in a marriage which would be recognised in Australia, again noting that s 23 of the Marriage Act makes void any marriage between persons within a “prohibited relationship”, as defined in a way that does not include first cousins.

(3) The principle of statutory interpretation that account must be taken of the consequences of giving a particular meaning to a provision, especially where a literal application of a particular interpretation would result in an absurd result, should be applied. The appellant submits that the potentially absurd consequence of construing the phrase as applying to any two persons who are descended from a common ancestor is illustrated by Adelaide Motors Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1942) 66 CLR 436 in which the term “relative” in a taxation statute was defined to include “a husband or wife or a relation by blood, marriage or adoption”. Latham CJ said (at 444):

A cousin fifty times removed is a relative under this definition. Possibly a sufficiently extensive investigation would show that nearly everybody in Australia, and millions of people outside Australia, are “relatives” of nearly everybody else in Australia within this definition. … This provision was properly described in Himley's Case [(1933) 1 KB 472 at 487)] as both bewildering and ridiculous.

The appellant contends that, for the same reason, it would be absurd to construe the phrase “related to your partner by blood” as applying to any two persons who are descended from a common ancestor, being impossible to identify and potentially unlimited in size.

(4) The phrase ought to be construed to give effect, so far as its language permits, to the context and purpose of the legislation, citing Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 at [70]. In this context, the appellant contends that the relationship question is directed towards ascertaining whether:

(a) an applicant meets the criteria that he or she either intends to marry a person who is an Australian citizen, permanent resident or eligible New Zealand citizen, per Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth), Sch 2, cl 300.211; or

(b) whether they are the spouse or de facto partner of an Australian citizen, permanent resident or eligible New Zealand citizen, per Migration Regulations, Sch 2, cl 820.211(2).

“Spouse” is relevantly defined in s 5F(1) of the Migration Act as two persons who are “in a married relationship”, which in turn is relevantly defined in s 5F(2)(a) as, in part, being “married to each other under a marriage that is valid for the purposes of this Act”. Pursuant to s 12 of the Migration Act, for the purpose of deciding whether a marriage is to be recognised as valid for the purposes of that Act, Pt VA of the Marriage Act applies as if it did not contain s 88E (dealing with recognition of foreign marriages).

28 In light of the foregoing, the appellant submits that both the delegate and the Tribunal were “disingenuous” when they stated that the appellant’s failure to disclose that his wife was his first cousin was relevant to the genuineness of the relationship, because the relationship question was directed to “prohibited relationships” within the meaning of the Marriage Act. The appellant was not in a prohibited relationship, so he was not required to answer “Yes” to the relationship question. It follows, he submits, that there was no non-compliance with s 101(b) of the Migration Act and the cancellation provision in s 109 was not engaged.

29 The Minister submits that the ordinary meaning of “related to your partner by blood” conceded by the appellant is not displaced as suggested for the following reasons:

(1) The fact that the possible entitlement to a partner visa would not necessarily be affected by a familial relationship with a sponsor does not displace this “ordinary meaning” in the context of the relationship question in each visa application form. That is, the Minister submits, because the phrase in issue was simply directed to whether the appellant and the sponsor were “related by blood”, not to whether the marriage was permissible under Australian law – the wider former inquiry should not be read as confined by, or directed only towards, the latter narrower inquiry.

(2) The Minister submits that the appellant’s reliance on Salama is misplaced. The visa applicant in Salama was required to select his relationship status from a list of options, one of which was “married”. As the online form indicated in a “?” dropbox, reproduced in her Honour’s judgment, “married” described a situation where the visa applicant and partner “have entered into a marriage which is legally recognised and documented”. It was against this very different context and background that Perry J said (at [60]-[61]) that the word “married” meant a marriage that was recognised in Australian law. Her Honour’s comments therefore do not support the proposition that the relationship question in this case is confined to ascertaining whether the appellant was in a relationship that would be recognised as a marriage under Australian law.

(3) Rather, the Minister submits, the question “are you related to your partner [or fiancé(e)] by blood” was relevant to both the nature and the bona fides of the appellant’s relationship with the sponsor, not just the former: that is, both legality and genuineness. It could be relevant in all sorts of other ways. The primary judge was therefore correct to find (at [19]), that the Tribunal did not err in rationalising that “it may well be relevant to the Department in considering the genuineness of a relationship to have regard to the closeness of that relationship, without it meaning an automatic preclusion from the granting of the visa”.

(4) As an alternative, and without diminution of the preceding arguments, the Minister submits that even if the question were not relevant to the determination of the appellant’s visa application, this would not assist the appellant. That is because visa applicants are under an absolute obligation to give truthful answers to questions in visa application forms under s 101, and there will be non-compliance even though the applicant may have been unaware that he or she was providing incorrect information (s 100). Nothing in the text of the Migration Act suggests that the absolute obligation to give correct answers is limited only to questions confined to visa criteria. The appellant breached this absolute obligation by providing incorrect answers to the relationship question “are you related to your partner by blood” and thereby failed to comply with s 101(b).

(5) The Minister points out that the appellant’s contention that the term “related by blood” has a breadth that is potentially expansive or even absurd was taken into account by the Tribunal at [42]-[44]. The Tribunal observed that it “can include very distant relatives, which could go to the point of absurdity”, but considered that the form of the question required the appellant “to disclose the existence of any known blood relationship no matter how distant”.

(6) The Minister also points out that the Tribunal observed that discretion could deal with most cases where the relationship was so distant as not to be relevant to a decision to grant or not grant the visa, but that here the appellant was “very closely related to the sponsor” and, while the relationship “would not have automatically precluded him from being granted the visa, it would have indicated to the Department that it may need to investigate the relationship more fully”.

(7) The Minister therefore submits that a question which seeks to gain information that may be of assistance in investigating a relationship is not absurd, but rather serves a legitimate purpose. Here, the appellant and his sponsor were first cousins, their mothers being sisters, and the Tribunal (at [44]) therefore correctly characterised the appellant as being “very closely related” to the sponsor. A relationship of this kind was therefore both within the ordinary meaning of the phrase “related by blood” and relevant to the decision-maker’s task. The relationship question “are you related to your partner [or fiancé(e)] by blood” reached the relationship between the appellant and his sponsor, requiring the answer “Yes”.

(8) The Tribunal and the primary judge were correct and this ground should fail.

Consideration

30 The Tribunal’s conclusion at [43] that the form of the relationship question required the appellant “to disclose the existence of any known blood relationship no matter how distant” should not be read as being contrary to ss 100 and 111. The obligation to give a correct answer does not depend on any knowledge of the existence of the relationship, but the appellant in fact knew that his then fiancé was his first cousin. The point that the Tribunal was making is that no issue of absurdity in disclosing that she was a distant relative arose in this case.

31 Despite the complexity of the competing arguments, the live issue is whether there is any compelling reason to depart from the ordinary meaning of the words “related by blood”. The form is not a contract or a statute. It follows that there is no basis for the application of principles of statutory construction, albeit that reasoning in that jurisprudence may be helpful in a given case by way of analogy. Rather, the meaning of a question posed in a visa application form should not be approached with undue formality or complexity, but with a practical bent having regard to the myriad of reasons, both obvious and obscure, in seeking particular information. It should not entail, contrary to what the appellant effectively submits, any requirement to conduct legal research or obtain legal advice.

32 It follows that the ordinary meaning of words or phrases in a visa application form should not lightly be departed from. The appellant has not demonstrated that any departure from the agreed ordinary meaning of the relationship is warranted. There is much force in the Minister’s submission that the question is directed both to the legality and to the genuineness of the relationship, but it is not necessary to decide that. It is possible that other reasons presently exist for the question, or may exist in the future. It was a straightforward question requiring a straightforward answer. The appellant and his sponsor were first cousins, and it is therefore plain that they were “related by blood” in the ordinary meaning of that phrase.

33 There is no need to consider hypothetical situations in which a more distant relationship is not disclosed and perhaps not even known to exist. Such a situation can wait for a case in which the issue of a more distant blood relationship actually arises, which may be quite unlikely to occur. How distant the relationship is, and whether a visa applicant knew about it, is relevant to the exercise of the discretion, not to the correctness of the answer.

34 This ground of appeal must therefore fail.

Grounds 2 and 3

35 The appellant addresses these grounds concisely, having earlier gone into the detail of the information that was in the documents referred to in the s 375A certificate, which indicate live questions about the legitimacy of other relationships between the extended family of the appellant and his sponsor. The appellant argues that the contents of those documents were material to the decision of the Tribunal in the sense that non-disclosure operated to deny him the opportunity to give evidence or make arguments which thereby deprived him of the possibility of a successful outcome, citing Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA [2019] HCA 3; 363 ALR 599 at [2]-[3], and [48]-[49].

36 That denial is said to have taken place because the documents withheld revealed that the sponsor’s father had migrated to Australia with the sponsor’s mother, then sponsored a second Vietnamese wife, then attempted to sponsor the appellant’s mother. The delegate dealing with the visa application by the appellant’s mother had considered that the sponsor’s father and the appellant’s mother had been grossly dishonest about their visa claims. The inference was therefore that the family was involved in contriving relationships to bring non-citizens to Australia, being an express finding made by the delegate in relation to the appellant’s mother’s visa application. This was also implicit in the referral of the documentation to the delegate for consideration in respect of the appellant’s visa application. The documents referred to in the s 375A certificate stated several times that the relationship between the appellant and his sponsor was very likely to have been contrived and was not genuine.

37 The appellant contends that the withheld information was therefore not mundane or anodyne, citing a Federal Circuit Court of Australia case on the topic. To the contrary, he submits, it was highly relevant to the credibility of the appellant, which was a live issue, and the subject of adverse findings by the Tribunal. He submits it was also relevant to the discretion as to whether or not to cancel the appellant’s permanent visa by reference to the circumstances in which it occurred and any other instances of non-compliance by the visa holder known to the Minister. The appellant therefore submits that reliance on the invalid s 375A certificate and the consequential failure to provide the documents to him under s 362A(1) was material to the Tribunal’s decision and caused the decision-making process to miscarry by a denial of procedural fairness.

38 The submissions for the appellant proceed as though the information in the documents referred to in the s 375A certificate, and not provided to him, were relied upon by the Tribunal in support of the adverse conclusion reached. He is, in substance, arguing that he was not given an opportunity to answer that adverse material. The problem with that submission is that the Tribunal made the express finding that the information in those documents was not relevant. Whether that conclusion was right or wrong, the Tribunal did not take them into account. As the primary judge pointed out at [37] (reproduced at [23] above) her Honour, and equally this Court, were entitled to take the Tribunal at its word in saying at the hearing (reproduced at [20]) that “anything that I refer to in those documents I will specifically address, if I do need to refer to them”, although it was not clear that this would be raised with the appellant first, as her Honour appears to have inferred, having regard to the strictures imposed by a valid s 375A certificate. It is open to infer, however, that the Tribunal did not even consider those documents, given that the description given to them is drawn from the face of the invalid s 375A certificate, and given that the decision was made on the basis of an incorrect answer, without any need to delve into any issue of whether the relationship between the appellant and his sponsor was genuine. As the Minister points out, the High Court said in SZMTA, in relation to a similar certificate provision in s 438 of the Migration Act, (at [47]):

The drawing of inferences can be assisted by reference to what can be expected to occur in the course of the regular administration of the Act. Although it is open to the Tribunal to form and act on its own view as to whether a precondition to the application of s 438 is met, the Tribunal can be expected in the ordinary course to treat a notification by the Secretary that the section applies as a sufficient basis for accepting that the section does in fact apply to a document or information to which the notification refers. Treating the section as applicable to a document or information, the Tribunal can then be expected in the ordinary course to leave that document or information out of account in reaching its decision in the absence of the Tribunal giving active consideration to an exercise of discretion under s 438(3). Absent some contrary indication in the statement of the Tribunal’s reasons for decision or elsewhere in the evidence, a court on judicial review of a decision of the Tribunal can therefore be justified in inferring that the Tribunal paid no regard to the notified document or information in reaching its decision.

39 Thus the Tribunal, in the regular administration of the Migration Act, was entitled to treat the s 375A certificate as valid and can be expected in the ordinary course to leave the documents referred to in that certificate out of account, noting that the form of the certificate did not enliven any discretion to provide the documents to the appellant: see ss 375A(1)(b) and 376(1)(b).

40 The appellant has not established that the Tribunal even read the documents referred to in the s 375A certificate, let alone that it took them into account, contrary to what appears on the face of the Tribunal’s reasons.

41 There cannot be any denial of procedural fairness, at least in these circumstances, in not being given an opportunity to comment on adverse material that, rightly or wrongly, was considered irrelevant and therefore not taken into account. It follows that there was no error in the primary judge finding that the failure of the Tribunal to provide the documents to the appellant was not material because it could not have made a difference to the outcome. As the majority pointed out in SZMTA at [45], “[a] breach is material to a decision only if compliance could realistically have resulted in a different decision”. Being deprived of an opportunity to address adverse material that was not relied upon could not realistically have resulted in a different outcome.

42 As the substratum for both grounds 2 and 3 is misconceived, both grounds should fail.

Conclusion

43 The appeal must be dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding forty-three (43) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Nicholas, Katzmann and Bromwich. |

Associate: