FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

CLM18 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 170

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent INFORMED REFERRAL TO STATUS RESOLUTION OFFICER Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed with costs.

2. Orders 2 and 3 made by the Federal Circuit Court of Australia on 7 May 2019 be set aside.

3. The parties bring in short minutes of order to give effect to these reasons within 21 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1 The Appellant is a Sri Lankan national of Tamil ethnicity. He arrived in Australia in October 2012 by boat without a valid visa and was taken to Christmas Island, an external territory of the Commonwealth situated in the Indian Ocean around 1,550km north-west of Australia and around 350km south of the Indonesian island of Java. It is unclear from the appeal papers but it appears likely that the boat he was travelling on was intercepted at sea by Commonwealth officials who then took him to Christmas Island. By s 5 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (‘the Act’) a person ‘enters Australia’ if they enter the ‘migration zone’. The migration zone is defined in s 5, relevantly, to include the area consisting of the States and Territories above the mean low water mark. The Territories are defined by s 5 to include the internal and external territories to which the Act extends. Section 7(2) extends the operation of the Act to the ‘prescribed territories’, an expression further defined in s 7(1) to include the Territory of Christmas Island. Consequently, Christmas Island is part of the migration zone.

2 Because the Appellant was not an Australian citizen, he was a non-citizen within the meaning of s 5. Once he was in the migration zone he was an unlawful non-citizen because he did not hold a valid visa: s 14. The Appellant was therefore a person who entered Australia by sea and became in consequence an unlawful non-citizen. A person who enters Australia by sea at an ‘excised offshore place’ and who becomes thereby an unlawful non-citizen is taken by s 5AA to be an ‘unauthorised maritime arrival’ (‘UMA’). This matters because the Territory of Christmas Island is defined by s 5 to be an ‘excised offshore place’. Consequently, the Appellant is an unauthorised maritime arrival.

3 On his arrival at Christmas Island the Appellant therefore acquired two legal statuses for he was both an unlawful non-citizen and an unauthorised maritime arrival. The consequence of the former was that s 189(1) required him to be held in immigration detention. The consequence of the latter was that he was ‘unable’ to apply for any kind of visa because s 46A(1) deems any visa application made by an unauthorised maritime arrival not to be valid. The necessity for a visa application to be valid is significant as the Minister’s power to issue a visa under s 65 is delimited by the requirement that the application be a valid one.

4 That the Appellant was ‘unable’ to apply for a visa is relevant because there exists a class of visa known as a Bridging E visa which may be issued to persons who are ‘unwilling or unable’ to make a valid application for a visa: reg 2.25 of the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth). Since the Appellant was unable to make a valid application for a visa because of s 46A(1) the Minister, subject to other presently immaterial requirements, was empowered to issue the Appellant a Bridging E visa and to do so without any application by him for that visa: reg 2.25. On 20 August 2013, the Minister issued the Appellant a Bridging E visa and he was released from immigration detention, having been held therein for around ten months. The issue of this visa meant that the Appellant became a lawful non-citizen within the meaning of s 13, but it did not relieve him of the status of being an unauthorised maritime arrival. That status turned only on him having entered Australia by sea at an excised offshore entry place and, at that time, having become in consequence an unlawful non-citizen. The status was not erased when the Appellant subsequently ceased to be an unlawful non-citizen.

5 Although the bar in s 46A(1) continued to prevent the Appellant from applying for a visa (because he was an unauthorised maritime arrival), there existed in the Minister another power under s 46A(2) to lift the bar imposed upon the Appellant by s 46A(1) and to invite him to apply for a specified class of visa. On 23 May 2016 the Minister exercised this power in the case of the Appellant so as to permit him to apply either for a temporary protection visa (‘TPV’) or a safe haven enterprise visa (‘SHEV’). He wrote to the Appellant by letter bearing that date informing him that he had lifted the s 46A(1) bar. Both a TPV and a SHEV have as one of the criteria for their grant that the applicant is a person to whom Australia owes protection obligations under the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as amended by the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (‘the Refugees Convention’). A TPV has a maximum duration of three years and a SHEV has a maximum duration of five years. Both have certain social security entitlements attached to them although the latter encourages the holder to be resident in regional Australia. In 2014 the TPV and SHEV replaced various classes of protection visa which had conferred rights of permanent residency on the holder. This occurred on the passage of the Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Act 2014 (Cth).

6 There then followed a period in which the Department repeatedly wrote to the Appellant reminding him of the Minister’s invitation to him to make an application for a TPV or a SHEV. The Minister has a power under s 46(2C) to revoke an earlier lifting of the bar under s 46A(2). The correspondence sent by the Minister to the Appellant at one point observed that the Minister could revoke his decision to lift the bar if no application for a TPV or SHEV was forthcoming.

7 On 21 May 2017 the Minister announced in a media release entitled ‘Lodge or leave – Deadline for illegal maritime arrivals to claim protection’ that persons in the position of the Appellant who had not applied for a TPV or SHEV would need to do so by 1 October 2017 otherwise they would not be permitted to apply thereafter. This was reiterated in a further media release on 1 September 2017 titled ‘Last chance for [UMAs] as application deadline approaches’. On 19 September 2017 the Minister exercised the power under s 46A(2C) to revoke earlier determinations by him that the bar should be lifted in relation to a number of persons including the Appellant. The revocation was expressed to take effect on 1 October 2017. For technical reasons relating to weekends and a public holiday in New South Wales, the revocation most likely took effect on Tuesday 3 October 2017. Despite that, in these reasons in the interests of clarity I will refer to the cut-off date as being 1 October 2017. The Appellant did not apply for a TPV or a SHEV by this date (or, if it matters, by 3 October 2017 either).

8 The Appellant’s Bridging E visa expired on 29 July 2017. It is not clear whether this occurred because the visa itself was expressed to expire on that day or on the occurrence of some event which itself took place on that day. However, this is not material to any issue. When the visa expired the Appellant became once again an unlawful non-citizen under s 14 since he was a non-citizen without a valid visa. Thus by the time the Minister revoked the Appellant’s ability to apply for a TPV or SHEV on 1 October 2017, he was already an unlawful non-citizen.

9 By s 189(1) of the Act, an officer who knows or reasonably suspects that a person in the migration zone is an unlawful non-citizen is required to detain that person. On 18 January 2018 the Appellant was apprehended at a car wash by an officer and detained under s 189(1). By s 196(1) an unlawful non-citizen who has been detained under s 189 must be kept in immigration detention. By s 198(5) an unlawful non-citizen who has been detained and who has not made an application for a substantive visa in accordance with s 195(1) must be removed from Australia as soon as reasonably practicable. As at 18 January 2018 when he was detained the Appellant had not made an application for a substantive visa. An obligation of removal therefore arose under s 198(5) and the Department began to make arrangements for that eventuality. Although the Appellant’s challenge in the Court below and the present appeal extends to some of these initial administrative steps, for reasons which will shortly become apparent, they are legally irrelevant in light of subsequent events.

10 On 28 February 2018, after those immaterial steps had nearly been completed, the Appellant lodged an application for a SHEV. He did this by a letter from the Refugee Advice & Casework Service (‘RACS’) bearing that date. If the application was barred by s 46A(1) the writer asked the Department to treat it as a request to raise the bar under s 46A(2). The letter contained detailed submissions about the risks that the Appellant would face if he were returned to Sri Lanka.

11 It appears that this letter was received by the Department the next day on 1 March 2018. There is also material which suggests that it was received on 28 February 2018. It is not necessary to determine which is correct. On 2 March 2018 the SHEV application was rejected on the basis that it was invalid as the Minister had not lifted the bar under s 46A(2).

12 Guidelines had been issued by the Minister instructing when the Department should make a recommendation to him to consider lifting the bar under s 46A(2) in relation to a person who had failed to apply for a TPV or SHEV by the 1 October 2017 deadline. These were entitled ‘Minister’s s 46A(2) Guidelines – Procedural Instruction’ (‘the Guidelines’) and were issued on the same day, 19 September 2017, that the Minister had decided to revoke the Appellant’s ability to apply for a TPV or SHEV with effect from 1 October 2017. These Guidelines revised earlier guidelines. There is authority for the proposition that s 61 of the Constitution provides the power to make guidelines to instruct the Department on what kinds of case the Minister should be approached about to consider whether to exercise his power under s 46A(2) to lift the bar. The issue of such guidelines may be seen ‘as an executive function incidental to the administration of the Act and thus within the scope of the executive power which “extends to the execution and maintenance … of the laws of the Commonwealth”’: Plaintiff S10/2011 v Commonwealth [2012] HCA 31; 246 CLR 636 at 655 [51] (‘Guidelines Case’) per Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Bell JJ.

13 One of these guidelines issued by the Minister was to this effect:

Cases should be referred to me for consideration of the exercise of my public interest power where:

• [An unauthorised maritime arrival] has raised protection [sic] plausible protection claims, did not lodge a TPV or SHEV application before I revoked their initial s46A bar lift determination with effect from 1 October 2017, and has objective evidence of compelling and compassionate reasons that were beyond their control for missing the application deadline.

14 This guideline did not instruct the Department to carry out such an inquiry. Instead, it simply instructed the Department that if those requirements were met the case should be brought to the Minister’s attention so that he could consider whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2) to lift the bar.

15 The Department then set about determining whether the Appellant had plausible protection claims and whether there was objective evidence of compelling and compassionate reasons that were beyond the Appellant’s control for missing the application deadline; that is to say, it began to investigate for itself whether the Appellant fell within the guideline set out above. This required two inquiries: whether there were plausible protection claims and whether there were compelling and compassionate reasons beyond the Appellant’s control which explained why he had missed the 1 October 2017 deadline. It is to be noted that the guideline requires both conditions to be satisfied. For example, if the Department had been satisfied that there were protection obligations in respect of the Appellant but did not think there were compelling and compassionate reasons explaining why he had not lodged his application in time, the terms of the direction would appear to require the Department not to refer Appellant’s case to the Minister.

16 In the Appellant’s case, the first of these topics (protection obligations) was dealt with by the Department in the following fashion. First, on 2 March 2018 (after the visa application had already been rejected), an official known as an ‘Informed Referral to Status Resolution Officer’ (‘IRSR Officer’) produced a document entitled ‘Informed Referral to Status Resolution’ (‘IRSR’). The introductory paragraph on the first page of this document indicated that it would outline:

the known individual circumstances as they relate to Australia’s international non-refoulement obligations to assist Status Resolution to determine an appropriate pathway for a [UMA] who has been invited to apply for a protection visa but has not engaged in the process and has not lodged a protection visa application.

The reference to non-refoulement obligations was a reference to obligations imposed upon Australia not to return persons to a place where they face a real and substantial risk of serious harm. The content of these obligations is, to an extent, controversial and the formulation in the previous sentence is not intended to be definitive but only illustrative. It is not controversial, however, that the obligations are imposed by Arts 2, 6 and 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Art 33 of the Refugees Convention and Art 3 of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSSJ [2016] HCA 29; 259 CLR 180 at 189 [9] (‘SZSSJ HCA’); CRI026 v The Republic of Nauru [2018] HCA 19; 92 ALJR 529 at 536 [23]-[24].

17 Secondly, the IRSR Officer then considered the position of the Appellant. When she did so she had before her the letter from RACS dated 28 February 2018. That letter contained detailed submissions on the issue of whether Australia was subject to any non-refoulement obligations in respect of the Appellant. Indeed, the IRSR Officer set out the details of that submission at pp 4-6 of the IRSR. Before the primary judge and in this Court it was accepted by the Minister that the Appellant was not invited by the IRSR Officer to comment or make submissions. Strictly this is correct, but any such failure would not have involved, in itself, a breach of the rules of procedural fairness because, in fact, the Appellant did make an extensive submission on the issue of non-refoulement on 28 February 2018 and the IRSR Officer took that submission into account in reaching her conclusions.

18 Thirdly, the IRSR Officer then considered detailed information about the position of Tamils who were returned to Sri Lanka. In doing so the IRSR Officer made extensive use of country information about Sri Lanka which was adverse to the interests of the Appellant. It was common ground that this country information was not put to the Appellant for comment.

19 Fourthly, having surveyed the Appellant’s detailed submission on the non-refoulement issues and the adverse country information the IRSR Officer had obtained for herself, she concluded that Australia did not have any non-refoulement obligations in respect of the Appellant. This decision bore the date 2 March 2018.

20 Fifthly, on 3 March 2018, another official described only as the ‘Director’ ticked a box on the same document which appeared next to the words ‘I agree with the assessment’.

21 These five steps were encompassed in the first eleven pages of the IRSR. In effect, returning to the language of the Guidelines, the IRSR Officer had concluded—and the ‘Director’ had agreed—that the Appellant did not have plausible ‘protection claims’ where that expression is understood to be a reference which includes non-refoulement obligations.

22 The second issue, which was whether there were compelling and compassionate circumstances which prevented him from submitting an application by the 1 October 2017 deadline, was dealt with in the final two pages of the same IRSR. This time an official called the Protection Caseload Resolution Officer examined the circumstances in which the Appellant had missed the deadline. She had before her the submission made on the Appellant’s behalf by RACS which also dealt with the reasons the Appellant had failed to comply with the 1 October 2017 deadline. The Protection Caseload Resolution Officer concluded that the Appellant did not have compelling or compassionate reasons for failing to lodge his visa application before 1 October 2017. That conclusion was dated 9 March 2018. On the same page of the IRSR there were two boxes for the ‘Director’ to tick indicating agreement or disagreement with the conclusions of the Protection Caseload Resolution Officer. However, neither box has been ticked. There is also a field for the insertion of a date for the Director’s conclusion but this too appears not to have been completed.

23 There seems therefore to have been three conclusions reached:

(1) the conclusion of the IRSR Officer dated 2 March 2018 that Australia did not have any non-refoulement obligations with respect to the Appellant;

(2) the agreement with that conclusion by the Director dated 3 March 2018; and

(3) the conclusion of the Caseload Resolution Officer dated 9 March 2018 that there were no compelling or compassionate reasons why the Appellant had failed to lodge his application by 1 October 2017.

24 There was no actual direct evidence in this Court of any decision within the Department not to refer the Appellant’s case to the Minister. However, it is clear that such a decision was made. On 28 March 2018, an official wrote to RACS and informed it that the Department had treated the invalid application for the SHEV as a request for Ministerial intervention under s 46A(2). The letter informed RACS that the ‘request was assessed against the Minister’s section 46A(2) Guidelines, and found not to meet these guidelines as a case to be referred to the Minister.’ It is an inescapable inference that somewhere between the three conclusions referred to above and that letter an official, perhaps the ‘Director’, concluded that the Appellant’s case did not meet the Guidelines and would, therefore, not be referred to the Minister.

25 Mention was made above of certain other administrative steps taken after the Appellant was first taken into immigration detention on 18 January 2018. Those steps consisted of a very similar IRSR process to that conducted in March 2018. However, that process was disrupted by the Appellant’s application for a SHEV on 28 February 2018. The IRSR process just referred to above supplanted this earlier process rendering it legally irrelevant. The actual decision which matters is the decision not to refer the matter to the Minister and the earlier IRSR process is not causally connected to that conclusion. The earlier IRSR process may therefore be disregarded, contrary to the submissions of the Appellant.

26 The Appellant was then a person who was being detained under s 189(1) (as already noted), who had entered Australia after 30 August 1994 and who had not been immigration cleared since he entered Australia. Consequently, he was a person to whom s 193(1)(b) applied. Being a person to whom s 193(1)(b) applied and being also a person who had failed to make a valid application for a visa whilst in the migration zone, he was required to be removed as soon as was reasonably practicable by reason of s 198(2). On 11 May 2018 officials served on the Appellant a notice of an intention to remove him from Australia on 15 May 2018. The Appellant commenced a proceeding in the Federal Circuit Court on 14 May 2018 initially challenging the decision to remove him under s 198(2) on the basis that he had made a valid application for a visa. On 17 May 2018 the Federal Circuit Court ordered the Minister not to remove the Appellant from Australia. The Appellant’s claim for judicial review was determined by the Court below on 30 April 2019: CLM18 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCCA 1106. It dismissed the claim. The primary judge found at [2] that the Appellant remained in immigration detention, however, this Court was informed that he had subsequently been released.

27 In this Court, the Appellant submits (as he submitted in the Court below) that, inter alia, the procedure adopted by the IRSR Officer in reaching the conclusion on 2 March 2018 that Australia did not have any non-refoulement obligations with respect to the Appellant was procedurally unfair. It was procedurally unfair because the IRSR Officer utilised country information which was adverse to the Appellant and upon which he was not given any opportunity to comment: Plaintiff M61/2010E v Commonwealth [2010] HCA 41; 243 CLR 319 at 356-357 [91] (‘Offshore Processing Case’).

28 Consistently with that principle, the Minister did not dispute that if a duty of procedural fairness existed then it was breached.

29 The Appellant submitted that the process by which the non-refoulement issues were determined in the IRSR of 2 March 2018 was subject to a duty to afford him procedural fairness. There were said to be a number of reasons for this. First, the decision embodied in the IRSR was part of a process in which the Minister had decided to consider whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2) to lift the bar in relation to the Appellant. Secondly, the power in s 46A(2) has two aspects: a power to consider whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2) and then an actual exercise of that power either by lifting or not lifting the bar. Thirdly, and consequently, the Minister’s decision to consider whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2) was itself an exercise of the power in s 46A(2) albeit the exercise was not complete. Fourthly, as the exercise of a statutory power, s 46A(2) was subject to an obligation of procedural fairness unless the Act manifested a sufficiently clear intention to the contrary, which it did not. Fifthly, since the IRSR was a step along the way to (or ‘under and for the purposes of’) assisting the Minister in the exercise of a power which was itself subject to an obligation of procedural fairness, it followed that the entire process had to be procedurally fair. If some step along the way compromised the procedural fairness of the process the duty would be breached. Sixthly, because the IRSR had been conducted without giving the Appellant an opportunity to comment on the adverse country information it followed that the Minister’s exercise of the power in s 46A(2) to consider whether to raise the bar had resulted in a process which was procedurally unfair. Seventhly, that want of procedural fairness could not be remedied by certiorari because there had been no decision not to lift the bar which could be quashed. Nor was it amenable to mandamus because the Minister was under no obligation to exercise the power in s 46A(2) since s 46A(7) was explicit in saying that the Minister was under no such duty. However, declaratory relief could be granted in the form of a declaration that the Minister’s exercise of the initial aspect of the power in s 46A(2) was unlawful because the IRSR process had been conducted without affording the Appellant procedural fairness.

30 The second to seventh propositions should all be accepted as they are directly established by the High Court’s decision in the Offshore Processing Case. The Minister did not dispute any of them. In fact, there were only two issues between the parties: (a) the factual question of whether the Minister had made a personal procedural decision to consider whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2); and, (b) assuming an affirmative answer to that question, whether any sufficient interest of the Appellant was affected by the impugned decision-making process so as to enliven an obligation of procedural fairness.

Was there a personal procedural decision by the Minister under s 46A(2)?

31 The Appellant, supported by the Australian Human Rights Commission (‘AHRC’), which was granted leave to appear as amicus curiae, submitted that the Minister had made such a decision on 19 September 2017. It was on that day, it will be recalled, that the Minister issued the new Guidelines to the Department setting out what kinds of cases should be brought to his attention involving persons such as the Appellant for the purposes of him considering whether to exercise the power in s 46A(2). It was also on that day that the Minister had made the decision to revoke his earlier decision in relation to the Appellant (and others) to lift the s 46A(1) bar so that an application for a TPV or SHEV could be made. In addition to those activities, however, the Minister also ‘noted’ a Departmental submission to him which explained how the Department would be assessing the non-refoulement obligations of the Commonwealth with respect to persons in the position of the Appellant.

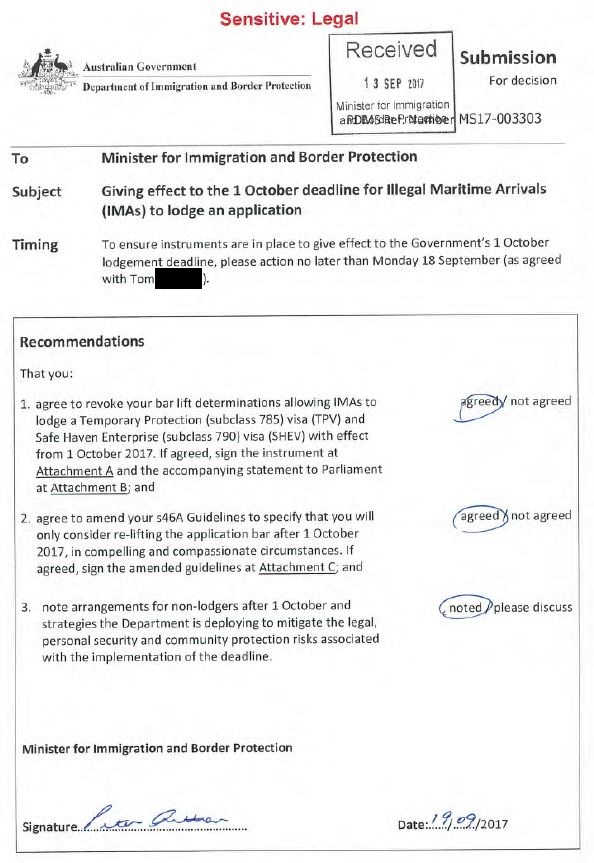

32 Because the Minister’s handwriting is relevant to the issues which arise it is useful to set out the first section of the document which records the Minister’s decision making (with redactions applied to Officers’ names):

33 It will be observed that the document takes the form of a Ministerial submission which was received by the Minister on 13 September 2017. Attachment A is the instrument by which the Minister revoked his earlier determinations to lift the bar. The instrument operated in relation to a number of persons including the Appellant. By s 46A(4) the Minister is required to place a statement before Parliament when that power is exercised. Attachment B is a draft statement to Parliament drafted for that purpose. It will be seen that the Minister has circled the word ‘agreed’.

34 Attachment C was the proposed new form of the Guidelines. As will be seen, the Minister agreed to the new Guidelines by circling the word ‘agreed’ next to recommendation 2.

35 Paragraph 3 refers to the ‘arrangements for non-lodgers’ that the Department was proposing to deploy. These arrangements are then set out in the submission. The relevant paragraphs are 5, 6 and 9-15. It is necessary to set them out in full:

5. Arrangements to support the referral of [UMA] non-lodgers for the grant of the Final Departure Bridging E Visa and for cessation of SRSS are being finalised.

6. The Department continues to monitor and put in place arrangements to mitigate legal, personal security and community protection risks associated with the implementation of the deadline.

Background

…

Non-lodgers – next steps

9. IMAs who do not lodge before the deadline will be referred to Status Resolution officers in the Department’s State and Territory offices. They will be granted a Final Departure Bridging E visa. Community Protection Division has begun assessing the vulnerability of [UMA]s who have not lodged a TPV or SHEV application to determine their eligibility for ongoing support if they do not engage in the process. Those with no identified vulnerability will have services ceased and income support removed as per the 2017-18 Budget measure, immediately after the application deadline, those identified with a potential vulnerability will be invited for interview to determine next steps towards departure and if support services are required. Interviews will be scheduled from 5 October 2017. The specific criteria guiding the Department’s decision making in relation to support services are that the person is unable to depart Australia due to:

• Medical advice that the person is not fit to travel;

• A community protection risk or risk to others that can be mitigated by access to medication or treatment; or

• An immediate self-harm risk.

10. Concurrently, the Department will undertake an assessment of each [UMA]’s entry interview, records of any previous claims raised and country information to identify any potential protection based barriers to removal. If non-refoulement issues are raised that suggest that removal might be in breach of Australia’s obligations under international law, the Department will prepare a submission for your consideration setting out options for status resolution, including re-lifting the bar to fully assess protection, or granting a long-term Final Departure Bridging E Visa.

11. Non-lodgers who do not take steps to depart voluntarily and those who disengage from the Department will be referred to the Australian Border Force (ABF) under Operation BADIGEON. Any non-lodger who poses a risk to the Australian community will be allocated the highest priority response by ABF.

12. Some [UMA]s who do not lodge by 1 October 2017 may later approach the Department and seek your re-intervention to lift the s 46A bar and allow them to lodge an application. Under our current s 46A Guidelines any [UMA] seeking to claim protection would be referred for your consideration. The revised Guidelines for your consideration and signature at Attachment C would narrow that scope. Where [a UMA] has not made an initial TPV or SHEV application before 1 October, they would only be referred to you where they have objective evidence of compelling and compassionate reasons for missing the application deadline that were beyond their control. You also retain the capacity to personally request that a matter be referred for consideration of a new bar lift.

13. A small number of [UMA]s will not be able to lodge an application before 1 October due to acute mental or physical health reasons that render them unable to put forward protection claims in any meaningful way. Some of these individuals are known to the Department and it is anticipated that others will come to attention in the weeks and months following the application deadline. The Department proposes to put forward submissions allowing you to consider alternative status resolution under your Ministerial intervention powers.

14. Despite the Department’s multi-faceted direct and indirect outreach to [UMA]s about the need to apply and the consequences of not meeting the 1 October deadline, the revocation o the s 46A bar and efforts to enforce removals for non-lodgers who entered Australia with the specific objective of seeking protection is not without legal risk.

15. There are three key areas that are likely to result in legal challenge.

• Your decision to revoke your original bar lift determination;

It might be argued that, in the absence of an express exclusion, the rules of natural justice apply to the exercise of the revocation power under s 46A(2C) and that this requires that each affected person be given an opportunity, in advance of the exercise of the power, to make representations as to why it should not be exercised in their case. We would argue that this is impractical in the present context and that, instead, each potentially affected adult [UMA] has received a minimum of two direct letters from the Department communicating the application deadline and the consequences of not meeting it. This has been supported by outreach through culturally and linguistically diverse media outlets, SRSS providers, community organisations and direct phone calls from the Department’s Status Resolution officers.

• Inability of those who miss the deadline to lodge an application and put forward claims;

The Department will have referral processes in place to ensure that any protection claims raised after the application deadline are assessed by protection officers. The amendments to your s 46A Guidelines at Attachment C do not preclude [UMA]s who are found to meet Australia’s international obligations being referred to you to consider re-lifting the bar.

• Involuntary removal of [UMA]s who came to Australia to seek protection;

The Department will conduct an on the papers assessment of each non-lodger ahead of any planned removal. This assessment will be informed by current country information, claims raised during initial screening processes and entry interviews, and any other claims previously raised with the Department.

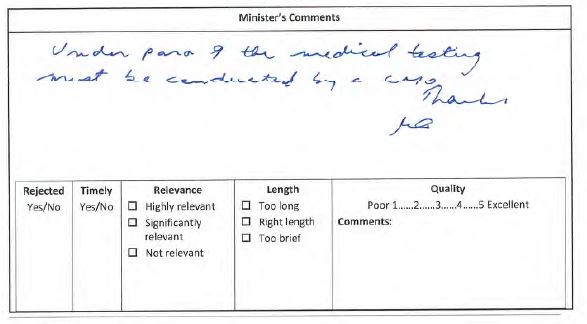

36 On the front page, in relation to these arrangements the Minister was proffered a choice in relation to these arrangements between ‘noted’ and ‘please discuss’. The Minister has circled ‘noted’. Under the Minister’s notes the Minister has also written in his own handwriting ‘Under para 9 the medical testing must be conducted by a CMO [Commonwealth Medical Officer]. Thanks.’

37 In SZSSJ HCA the High Court described the process by which dispensing powers such as s 46A(2) operate at 200 [53]-[54]:

First, each section confers a non-compellable power that is exercised by the Minister personally making two distinct decisions: a procedural decision, to consider whether to make a substantive decision; and a substantive decision, to grant a visa or to lift the bar. The Minister has no obligation to make either decision, and neither the procedural decision nor the substantive decision of the Minister is conditioned by any requirement that the Minister afford procedural fairness.

Second, processes undertaken by the Department to assist in the Minister’s consideration of the possible exercise of a non-compellable power derive their character from what the Minister personally has or has not done. If the Minister has made a personal procedural decision to consider whether to make a substantive decision, a process undertaken by the Department to assist the Minister's consideration has a statutory basis in that prior procedural decision of the Minister. Having that statutory basis, the process attracts an implied statutory requirement to afford procedural fairness where the process has the effect of prolonging immigration detention. If the Minister has not made a personal procedural decision to consider whether to make a substantive decision, a process undertaken by the Department on the Minister’s instructions to assist the Minister to make the procedural decision has no statutory basis and does not attract a requirement to afford procedural fairness.

38 The Appellant submitted that the Minister’s actions showed that he had made a ‘personal procedural decision’ as described in [53] so that the Department’s activities thereafter, including the IRSRs, were statutory in nature for the reasons given in [54]. The principal question is whether the evidence shows that the Minister made a personal procedural decision.

39 The AHRC submitted that a relevant matter was that it could be inferred that the Minister had read the submission document. The evidence supports the drawing of that inference which was not resisted by the Minister. The handwritten notation by the Minister about the operation of para 9 of the submission and his direction in relation to it, that medical testing be conducted by a Commonwealth Medical Officer, shows not only that the Minister read the submission but that he read it with care and grasped its detail. The Appellant submitted that the fact that the Minister circled the word ‘noted’ was really in the nature of an approval especially when read in contradistinction with the alternative ‘please discuss’.

40 In the same vein, also relevant is the comment under the heading ‘Minister’s Comments’. One reading of the comment is that the Minister was saying ‘If you decide to go down the path you describe in para 9 and obtain medical advice that the person is not fit to travel, please be sure to use a Commonwealth Medical Officer’. Another reading is that the Minister was indicating that he was content for the procedures to be carried out save that they were to be modified to the extent he indicated. Also relevant is the fact that the submission was dealing with a non-trivial number of persons. At para 1 the submission suggested that the ultimate size of the non-lodging cohort would be about 800 persons. What the Department was saying to the Minister was, therefore, that it was about to undertake a substantial process involving a significant number of persons.

41 The AHRC submitted the situation was on all fours with the situation in SZSSJ v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] FCAFC 125; 234 FCR 1 (‘SZSSJ FC’, and together with SZSSJ HCA, ‘SZSSJ’) where the Full Court had a made finding of fact (not disturbed on the subsequent appeal to the High Court) that there had been a personal procedural decision. In that case the personal details of 9,258 persons had accidentally been made available on the internet by the Department. This created the possibility of sur place claims. The Secretary of the Department had written to all 9,258 persons to tell them that their positions would be reviewed as part of its normal processes. These normal processes had involved a non-statutory assessment of non-refoulement issues by means of a Departmental procedure known as an International Treaties Obligations Assessment (‘ITOA’). The Full Court drew this conclusion of fact at 24 [80]:

The specific matter is that in this case the Secretary of the Department has written to the 9,258 people affected by the Data Breach to tell them that their position will be reviewed. Given the magnitude of the event from an administrative perspective, the Secretary’s decision, as stated in his letter of 12 March 2014, to have the Department assess any implications for each of those people personally ‘as part of its normal processes’, the very considerable budgetary expense in conducting 9,258 such reviews, their continuing detention for a period of six months until the making of the decision to use an ITOA process to conduct those reviews, the significance of Australia’s international obligations in respect of the 9,258 persons affected by the Data Breach and the ITOA processes which were then instigated, we consider it unlikely that the Minister is not personally aware of the Data Breach and the processes contemplated in the Secretary’s 12 March 2014 letter.

42 Here, so the AHRC submitted, there was a significant cohort of persons involved and the deployment of the IRSR process would be resource intensive. Further, the case was stronger than SZSSJ because there was direct evidence that the Minister knew about the process because the submission informed him of it. The Full Court in SZSSJ FC observed at 24-25 [82]:

Granted that the Minister is personally aware of the ITOAs, it seems an unavoidable inference that he has already decided to consider these 9,258 matters under his dispensing powers. If he has not decided to consider the non-refoulement claims, why has he suffered the ITOA process to be carried out on his behalf? Further, given that, in a case such as the present, Australia’s international obligations relating to non-refoulement can only be given expression under domestic law through the exercise of the Minster’s own personal powers in ss 48B, 195A and 417, we would hesitate to conclude that the Minister has put in place a structure in which persons making claims relating to non-refoulement were not given the opportunity to have the only officer of the Commonwealth who can vindicate those claims under Australian law consider them. It seems to us that such a state of affairs would be a breach by Australia of its non-refoulement obligations.

43 The AHRC submitted that the present process was also analogous to what had occurred in the Offshore Processing Case. In that case the Minister had publicly announced that a particular administrative process would be applied to an even larger cohort. That, along with other matters, led the High Court to infer that the Minister had, in that case, entered upon the exercise of the bar lifting power in s 46A(2).

44 The Minister, on the other hand, emphasised differences with SZSSJ. The procedure involved in the present case did not involve contacting a cohort of all persons affected by an adverse event. Rather, it was not concerned with any event, was merely a short process conducted on the papers to facilitate the Department’s own internal arrangements, and did not ‘seek, invite or require’ any decision from the Minister. Further, the IRSR process led to no direct outcome. In addition, in this case the IRSR process did not extend the time that the Appellant stayed in detention. The opening word of para 10 was ‘concurrently’ and this meant that the IRSR process was carried out in parallel with the process in para 9; accordingly it was said to be ‘designed never to prolong detention’. The steps in para 9 were plainly directed to the process of removal and would make any detention whilst they were taking place lawful under the Act. (This aspect of the matter is relevant not only to the issue of whether the Minister had made a personal procedural decision but also to whether any sufficient interest of the Appellant was affected by the process. I return to that topic below.)

45 The learned primary judge approached the matter in this way. Her Honour noted the two step nature of the power in s 46A(2) as involving a procedural decision to consider whether to exercise the power and a substantive decision as to whether the bar should or should not lifted. Her Honour identified, correctly with respect, that conduct which occurs prior to the procedural decision cannot be statutory in nature. Next the primary judge reasoned that the processes described at para 10 of the Ministerial submission were part of the Guidelines or of the same nature as the Guidelines (‘I am not persuaded that the steps at [10] … [are] entirely distinct from the Guidelines’). The significance of that observation is that it is established that the Guidelines do not provide evidence of a personal procedural decision by the Minister under s 46A(2): Guidelines Case. Her Honour then observed that the word ‘noted’ which had been circled by the Minister was in contradistinction with the word ‘agreed’ in relation to the other proposals contained within the submission. Ultimately, her Honour put the matter this way at [141]:

As was the case with the guidelines under consideration in Plaintiff S10, the Minister’s noting of paragraph 3 of the recommendation, and thus of the Departmental process described at [10], did not involve a decision of the Minister acting under s.46A(2) (or s.195A) to consider whether to consider the exercise of the power conferred by the section. The noting of the paragraph does not constitute or evidence the making of a decision by the Minister.

46 With respect to the learned primary judge, this involved error. Whilst no doubt at the granular level, the substantive decision must post-date the procedural decision, her Honour erred in failing to appreciate that in cases involving decisions affecting significant numbers of people (‘cohort cases’) the High Court in the Offshore Processing Case and this Court in SZSSJ FC have inferred an anterior procedural decision by the Minister from activities by the Department or the Minister. In the Offshore Processing Case it was the fact that the Department had publicly announced that the entire cohort of unauthorised maritime arrivals would be processed using a particular quasi-administrative procedure that led the Court to infer a decision by the Minister to consider the exercise of his powers for the whole cohort. So too in SZSSJ FC the Full Court reasoned in a similar fashion that there must have been a Ministerial decision to process the cohort in that case in a particular way. The learned primary judge did not appreciate that this required an analysis of whether such a decision could be inferred. Her Honour was distracted from this approach, perhaps understandably, by the statements in SZSSJ HCA that indicate that the procedural decision antedates the substantive decision. However, this does not remove the need to identify whether there is some anterior procedural decision, especially in cases involving entire cohorts of people. Where a cohort is involved, this makes much more likely that a procedural decision by the Minister was made because as the cohort increases in size it becomes much less likely that one can plausibly accept the Minister was not involved in the decision.

47 Accordingly, error is demonstrated and it falls to this Court to draw its own inferences about the matter: Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; 142 CLR 531 at 551. I do not read ‘noted/please discuss’ the same way as the primary judge did. The learned primary judge’s reading of ‘noted’ as simply connoting that the Minister was being informed is not consistent with ‘please discuss’ being the alternative. If it were purely for information then there could be nothing to discuss. So too, the handwritten remark by the Minister about the need in relation to para 9 to ensure that a Commonwealth Medical Officer was used shows not only that the Minister was approving the Department’s proposed procedures but that he was also invited to, and did, modify them in relation to para 9.

48 Nor would I accept that the Ministerial submission was to be seen as being of the same nature as the Guidelines. The Guidelines are pitched at the level of regulating what should be referred to the Minister and what should not be. They are not concerned with the actual processing of the cohort. On the other hand, the submission at paras 9-10 is not of that nature. It instead provided for a particular process in respect of a particular class of persons. Thus, whilst it is established the Guidelines do not provide evidence of a procedural decision by the Minister, that is not the case in relation to the submission.

49 Accordingly, I would accept that in his responses to the Ministerial submission on 19 September 2017 the Minister did make a personal procedural decision to consider lifting the s 46A(2) bar in relation to the entire cohort. In reaching that conclusion I have not disregarded the Minister’s submission that para 6 showed that the Department was still formulating its procedures. However, I do not read para 6 as detracting from the inference that the Minister had decided that the Department should proceed in the manner set out in paras 9 and 10.

Was a sufficient interest of the Appellant affected?

50 The Minister next submitted that even if there were a personal procedural decision by the Minister in this case, there would still be no sufficient interest of the Appellant to engage any duty to afford procedural fairness. A lynchpin in the reasoning in the Offshore Processing Case was that the procedure adopted lengthened the period of time during which a person was being held in immigration detention while it was carried out. It was the interest of the person in not being in detention for a longer period of time which was found to be the interest which generated the obligation of procedural fairness. The High Court explained it this way at [76]-[77]:

Rights or interests affected?

Contrary to the submissions of the Commonwealth and the Minister, the Minister’s decision to consider whether power should be exercised under either s 46A or s 195A directly affected the rights and interests of those who were the subject of assessment or review. It affected their rights and interests directly because the decision to consider the exercise of those powers, with the consequential need to make inquiries, prolonged their detention for so long as the assessment and any necessary review took to complete. That price of prolongation of detention is a price which some claimants may have paid without protest. After all, they sought entry to Australia and this was the only way of achieving that end. And they claimed that return to their country of nationality entailed a real risk of persecution. But even if it were the fact that individuals were content to have detention prolonged, that must not obscure that what was being done, for the purposes of considering the exercise of a statutory power, had the consequence of depriving them of their liberty for longer than would otherwise have been the case.

Because the Minister was not bound to exercise power under either s 46A or s 195A, no matter what conclusion was reached in the assessment or review, it cannot be said that a decision to consider exercising the power affected some right of the offshore entry person to a particular outcome. The offshore entry person had no right to have the Minister decide to exercise the power or, if the assessment or review were favourable, to have the Minister exercise one of the relevant powers in his or her favour. Nonetheless, once it is decided that the assessment and review processes were undertaken for the purpose of the Minister considering whether to exercise power under either s 46A or s 195A, it follows from the consequence upon the claimant’s liberty that the assessment and review must be procedurally fair and must address the relevant legal question or questions. The right of a claimant to liberty from restraint at the behest of the Australian Executive is directly affected. The claimant is detained for the purposes of permitting the Minister to be informed of matters that the Minister has required to be examined as bearing upon whether the power will be exercised.

51 Here, so the Minister submitted, it was apparent from para 10 of the Ministerial submission that the process of examining the non-refoulement claims was to be carried out ‘concurrently’ with the steps described in para 9. The steps in para 9 were directed at the process of removal and were plainly authorised by the Act. For example, para 9 showed that one of the steps taken was to ascertain whether the person involved was fit to travel. Unlike the Offshore Processing Case and SZSSJ, therefore, any examination of the non-refoulement claims in the IRSR process could not extend the period of time that the person was detained since they were going to be detained for that period of time whilst other statutory inquiries were carried out.

52 The primary judge found at [148] that the Appellant’s detention was not, in fact, prolonged by the carrying out of the IRSR process. No challenge is made to that finding. The AHRC submitted, however, that the correct question was not whether the Appellant’s detention was extended. Rather, the point was that the potential existence of non-refoulement obligations were understood to be barriers to removal which in itself raised the possibility that the detention might be prolonged. The submission that the non-refoulement obligations were understood to be barriers to removal rested on an email exchange within the Department. This email exchange occurred in the context of the Department seeking to have the Appellant psychiatrically tested so as to assess whether he had good reasons why he had not lodged his SHEV application prior to 1 October 2017. As part of that internal discussion one official sent this email to another on 22 January 2018:

Hi [name]

Thanks again for taking the time to discuss [the Appellant’s] case with me earlier.

As discussed, we will refer the client’s protection claims to our colleagues in order to assess whether there are any protection barriers to removal.

In regards to his claims regarding his mental health condition, grateful if you could request that he provide us a mental health assessment from a qualified professional; in short, we require documentary evidence in support of why he was unable to lodge before the deadline.

Once we receive this we will be able to further progress his case.

Regards,

[name] Protection Caseload Resolution Section Humanitarian Program Capabilities Branch | Refugee and Humanitarian Visa Management Division Visa and Citizenship Group Department of Home Affairs

53 Assuming that this does show that an assessment of non-refoulement obligations was understood by the Department to be a barrier to removal, this only goes in aid of the submission that there was a possibility that the detention might be extended at the time the Minister was considering the submission. However, the Offshore Processing Case and SZSSJ HCA both identified the interest that generated the procedural fairness obligation as the actual interest in not having the detention prolonged whilst the process was carried out. Neither directly supports the contention that a sufficient interest is demonstrated by proving that there is a possibility that the detention might be extended.

54 The extensive nature of what may constitute an ‘interest’ for this purpose was explained by Mason J in FAI Insurances Ltd v Winneke [1982] HCA 26; 151 CLR 342 at 360 in these terms:

The fundamental rule is that a statutory authority having power to affect the rights of a person is bound to hear him before exercising the power … The application of the rules is not limited to cases where the exercise of the power affects rights in the strict sense. It extends to the exercise of a power which affects an interest or a privilege … or which deprives a person of a “legitimate expectation”, to borrow the expression of Lord Denning M.R. in Schmidt v. Secretary of State for Home Affairs [[1969] 2 Ch 149 at 170], in circumstances where it would not be fair to deprive him of that expectation without a hearing …

(Citations omitted.)

55 Of course, the language of ‘legitimate expectation’ should now be eschewed: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v WZARH [2015] HCA 40; 256 CLR 326 at 335 [30] per Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ and 343 [61] per Gageler and Gordon JJ. Conceptually, I do not accept that for an interest to be affected sufficiently to attract an obligation of procedural fairness it needs to be shown that the interest will certainly be affected. It is sufficient that it be shown that there is ‘some clear form of possible adverse affectation’. That expression comes from Aronson M, Groves M and Weeks G, Judicial Review of Administrative Action and Government Liability (6th ed, Thomson Reuters, 2017) at p 419 and is the authors’ attempt to synthesise the modern state of the interest test. I agree with it.

56 Consequently, I accept in principle that a possible extension of the Appellant’s detention may be a sufficient interest to attract an obligation of procedural fairness. I do not accept that such an interest will be sufficient where the possibility of the extension of the detention is de minimis. It remains necessary therefore to ascertain whether the possibility in this case is de minimis.

57 I turn to an assessment of that issue shortly. In the meantime, it is useful to note two further matters. First, I do not accept the submission made on the Appellant’s behalf that the relevant interest of his which was apt to be affected was his interest in remaining in Australia. Whilst it seems to me that that interest is much more conceptually compelling than the interest in extended detention, the High Court endorsed the latter rather than the former in the Offshore Processing Case. No doubt that reasoning has certain consequences such as, for example, the fact that the submissions contemplated in the Offshore Processing Case were submissions about the eligibility of the person for a visa whereas the interest affected was their continued detention whilst the assessment was carried out. But it is not the role of an intermediate appellate court to question these matters.

58 Secondly, the assessment of the interest is to be made at the time the decision-making process is first initiated by the Minister’s personal procedural decision under s 46A(2). In this case, that was 19 September 2017. The issue therefore is not whether, in fact, the Appellant’s detention was extended by the IRSR process but rather, whether at 19 September 2017, there was a non-trivial possibility that it would be. This is a question which is not to be approached with the benefit of hindsight.

59 Turning then to an assessment of the extent of the possibility that the Appellant’s detention might be extended by the IRSR process, there are some factors which tend to suggest the possibility was low. The submission at para 10 required the IRSR process and the medical steps in para 9 to be carried out ‘concurrently’. There could be no doubt that the steps in para 9 were directed towards a statutory purpose under the Act viz the fitness of the person to travel. Detention for the purposes of para 9 would be lawful. Since the two processes were concurrent it would follow that para 9 did not contemplate that there would ever be a need for a person to be detained for para 10 purposes independently of their being detained for para 9 purposes. I do not accept, for the reasons I have already given, that the fact that the detention was not extended is the correct question.

60 Despite those matters I do not accept that the possibility that the Appellant’s detention might be prolonged was de minimis. This is for a number of reasons. First, ‘concurrently’ in this context does not mean simultaneously but is really more closely related to the concept of parallel processes of administration. What the Department was saying was that it would commence both processes and perform them in parallel. I do not think that it could reasonably be taken from the word ‘concurrently’ that the two processes had to start at the same time and finish at the same time.

61 Secondly, an added reason for thinking that is it seems likely that the removal process in para 9 was carried out by different officials to those conducting the IRSR process in para 10.

62 Thirdly, it is likely that the removal process was likely to involve administrative steps involving more than one official and, as the IRSR process shows in this case, where that occurs there are inevitably turn around delays. This would make it very unlikely that the two processes might be expected, viewed at the time when the Minister made the personal procedural decision, to reach their conclusion at the same moment.

63 Fourthly, and tending in the same direction, there is the fact that the assessment procedures contemplated in para 9 are quite straightforward by comparison to the processes which must be carried out under para 10 which involve an entire analysis of the Commonwealth’s non-refoulement obligations. It is inherently more likely that the IRSR process would take a longer time than the para 9 procedure. And, of course, these effects were only likely to be compounded given that a cohort of around 800 was to be processed. But one does not need to go that far; it is enough to say that it seems unlikely that they would end at the same time. As at the date of the Minister’s personal procedural decision the possibility that the IRSR process might prolong his detention was not de minimis.

64 In my opinion, a sufficient interest is established. The consequence of the Minister having made a personal procedural decision and of the Appellant having a sufficient interest to attract the rules of procedural fairness is that, because he was not shown the adverse country information, he was denied procedural fairness. As noted above at [28], the Minister did not dispute that if an obligation of procedural fairness was owed, it was breached in the Appellant’s case. I would therefore uphold grounds 3 and 4. The appeal should be allowed and the parties given an opportunity to frame the appropriate form of the relief.

IRSR process as an exercise of non-statutory executive power of the Commonwealth

65 As an alternative aspect of ground 4, the Appellant relied on the AHRC’s submission that the IRSR process should be seen as an exercise of Commonwealth executive power under s 61 of the Constitution. It is not necessary to deal with this argument. Nor is it necessary to deal with the AHRC’s further argument that the Minister was responsible for the IRSR process as administrative activity within his Department as a result of the principle of Ministerial responsibility reflected in s 64 of the Constitution.

Conclusion

66 I have had the advantage of reading in draft the reasons of Robertson and Abraham JJ. Their Honours would dismiss the Appellant’s appeal insofar as it relates to grounds 1 and 2. I agree with their Honours’ conclusions and their reasons for those conclusions. I would propose these orders:

(1) The appeal be allowed with costs.

(2) Orders 2 and 3 made by the Federal Circuit Court of Australia on 7 May 2019 be set aside.

(3) The parties bring in short minutes of order to give effect to these reasons within 21 days.

I certify that the preceding sixty-six (66) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Associate:

ROBERTSON AND ABRAHAM JJ:

Introduction

67 This appeal is from the judgment of a judge of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia delivered on 30 April 2019, with final orders being made on 7 May 2019. By those final orders, the application to that Court was dismissed, with costs. These reasons deal with whether the exercise of the revocation power in s 46A(2C) Migration Act 1958 (Cth) was subject to procedural fairness (ground 1) and whether the appellant was afforded procedural fairness in the exercise of the revocation power in s 46A(2C) (ground 2).

68 As summarised by the primary judge, the appellant was born in 1994 and is a Sri Lankan citizen of Tamil ethnicity. He arrived at Christmas Island by boat in October 2012 without a valid visa to enter Australia. In August 2013 he was granted a bridging visa E (since expired), and released into the community. On 18 January 2018, the appellant was located in the community and detained under s 189(1) of the Migration Act. He was subsequently taken to Villawood Immigration Detention Centre. He has now been released from detention.

69 On 11 May 2018, an officer of the Department of Home Affairs served on the appellant a Notice of Intention to remove him from Australia on 15 May 2018 under s 198(2) of the Migration Act (Removal Decision). Pursuant to orders of the Federal Circuit Court made on 17 May 2018, the Minister was restrained from removing the appellant from Australia.

70 By his amended application under s 476 of the Migration Act dated 25 May 2018, the appellant challenged the Removal Decision. The ground for this challenge was that the appellant had made a valid application for a Safe Haven Enterprise (subclass 790) visa (SHEV) in 2018 which was not affected by a purported decision of the Minister under s 46A(2C) on 19 September 2017 to revoke an earlier decision under s 46A(2) in about May 2016 by which the appellant was allowed to apply for a visa. In the alternative, the appellant by his amended application said that the Minister personally made a procedural decision on 19 September 2017 to consider the exercise of his powers under ss 46A and 195A of the Migration Act, and alleged that the assessment of protection based barriers to removal undertaken by the Department of Home Affairs in relation to the appellant was unlawful as the appellant was not afforded procedural fairness in relation to the assessment. The appellant filed a further amended application dated 1 May 2019.

71 The primary judge recorded at [4] that the parties ultimately agreed that, in substance, there were two issues raised by the appellant. The first issue was whether the Minister’s exercise on 19 September 2017 of his power under s 46A(2C) of the Migration Act in revoking his determination to allow certain persons (including the appellant) to lodge an application for a Temporary Protection visa (TPV) or SHEV under s 46A(1) (Revocation Decision) was subject to a requirement of procedural fairness, and, if so, what procedural fairness required in the circumstances, and whether the appellant was afforded it. These are now grounds 1 and 2 in the appeal.

The central statutory provision

72 Section 46A of the Migration Act provides:

46A Visa applications by unauthorised maritime arrivals

(1) An application for a visa is not a valid application if it is made by an unauthorised maritime arrival who:

(a) is in Australia; and

(b) either:

(i) is an unlawful non-citizen; or

(ii) holds a bridging visa or a temporary protection visa, or a temporary visa of a kind (however described) prescribed for the purposes of this subparagraph.

(1A) Subsection (1) does not apply in relation to an application for a visa if:

(a) either:

(i) the applicant holds a safe haven enterprise visa (see subsection 35A(3A)); or

(ii) the applicant is a lawful non‑citizen who has ever held a safe haven enterprise visa; and

(b) the application is for a visa prescribed for the purposes of this paragraph; and

(c) the applicant satisfies any employment, educational or social security benefit requirements prescribed in relation to the safe haven enterprise visa for the purposes of this paragraph.

(2) If the Minister considers that it is in the public interest to do so, the Minister may, by written notice given to an unauthorised maritime arrival, determine that subsection (1) does not apply to an application by an unauthorised maritime arrival for a visa of a class specified in the determination.

(2A) A determination under subsection (2) may provide that it has effect only for the period specified in the determination and, if it does so, the determination ceases to have effect at the end of the specified period.

(2B) The period specified in a determination may be different for different classes of unauthorised maritime arrivals.

(2C) The Minister may, in writing, vary or revoke a determination made under subsection (2) if the Minister thinks that it is in the public interest to do so.

(3) The power under subsection (2) or (2C) may only be exercised by the Minister personally.

(4) If the Minister makes, varies or revokes a determination under this section, the Minister must cause to be laid before each House of the Parliament a statement that:

(a) sets out the determination, the determination as varied or the instrument of revocation; and

(b) sets out the reasons for the determination, variation or revocation, referring in particular to the Minister’s reasons for thinking that the Minister’s actions are in the public interest.

(5) A statement under subsection (4) must not include:

(a) the name of the unauthorised maritime arrival; or

(b) any information that may identify the unauthorised maritime arrival; or

(c) if the Minister thinks that it would not be in the public interest to publish the name of another person connected in any way with the matter concerned—the name of that other person or any information that may identify that other person.

…

(7) The Minister does not have a duty to consider whether to exercise the power under subsection (2) or (2C) in respect of any unauthorised maritime arrival whether the Minister is requested to do so by the unauthorised maritime arrival or by any other person, or in any other circumstances.

The judgment of the primary judge

73 At [22], the primary judge said that as the appellant arrived in Australia by sea at an excised offshore place (Christmas Island) without a visa he was an “unauthorised maritime arrival” pursuant to s 5AA(1) of the Migration Act. As an unauthorised maritime arrival, he was precluded by s 46A(1) of the Migration Act from lodging a valid application for a visa unless and until the Minister exercised his power under s 46A(2) to lift the s 46A(1) bar.

74 At [27], the primary judge said that during 2015, after the passage of the Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Act 2014 (Cth), the Minister commenced making a series of determinations under s 46A(2) lifting the bar for unauthorised maritime arrivals who arrived at and entered Australia after 13 August 2012, but before 1 January 2014, and who had not been taken to a regional processing country. Prospective applicants were notified in writing, and invited to apply for a TPV or a SHEV.

75 In the appellant’s case, the primary judge said at [28], by a letter dated 23 May 2016 addressed to the appellant, the Minister exercised his discretion under s 46A(2) to lift the statutory s 46A(1) bar, and invited the appellant to make a valid application for a TPV or a SHEV. The letter was sent to the appellant at a Strathfield South address in Sydney.

76 Between 30 November 2016 and 22 September 2017, the primary judge found at [30], the Department sent the appellant five more letters, inviting him to apply for a TPV or SHEV, and, in the third and subsequent letters, informing him of adverse consequences if he did not so apply.

77 By April 2017, the primary judge found at [35], the appellant had not applied for a protection visa.

78 On 21 May 2017, the primary judge found at [39], the Minister issued a media release headed “Lodge or leave – Deadline for illegal maritime arrivals to claim protection” in which he announced that the government had that day set a deadline for unauthorised maritime arrivals (then referred to as “Illegal Maritime Arrivals” or “IMAs”), such as the appellant, to prove that they were genuine refugees and owed protection obligations by Australia. The media release stated that they must lodge applications for processing by 1 October 2017.

79 On 12 September 2017, the primary judge found at [44], the Department made a written submission to the Minister for decision on steps necessary to give effect to the 1 October deadline that had been announced on 21 May 2017. On 19 September 2017, by the process described in Perram J’s reasons at [31]-[33], the Minister agreed to revoke his bar lift determinations, and to amend his s 46A guidelines, and signed three attachments. He noted Departmental arrangements for non-lodgers after 1 October 2017.

80 On 22 September 2017, the primary judge found at [45], the Department sent a sixth letter to the appellant titled “Last notice – 1 October 2017 – deadline to apply for a Temporary Protection visa or a Safe Haven Enterprise visa” in which the appellant was advised that if he was seeking protection in Australia he must apply by 1 October 2017. The Department advised that the Minister had made a decision under s 46A(2C) of the Migration Act to revoke or cancel his determination that allowed the appellant to apply for a TPV or SHEV, and that the revocation or cancellation would take effect on 1 October 2017. The appellant was advised that if he did not apply before 1 October 2017, he would be barred from applying for a TPV or a SHEV and would need to make arrangements to depart Australia. If he did not make arrangements to depart he would be subject to detention and removal from Australia. This letter was returned to sender on 19 October 2017.

81 The primary judge stated the following conclusions:

113. In my view, the particular statutory scheme in which s.46A(2C) is situate (s.46A read as a whole), the emphatic language and the limited circumstances in which s.46A(2C) operates – only where the power in s.46A(2) has been exercised, and only to persons who had been afforded dispensation from the s.46A(1) bar or a sub-set of such persons – lead to the conclusion that the provision evinces the necessary intendment to displace a requirement that the Applicant be afforded procedural fairness before the Minister made the Revocation Decision. I do not consider that it is necessary to evince a necessary intendment in accordance with the principle in Annetts, as explained by the High Court in Plaintiff M61 [[2010] HCA 41; 243 CLR 319] and SZSSJ [[2016] HCA 29; 259 CLR 180], that s.46A(2C) be “dispensing”.

114. Further support for my conclusion can be found in Plaintiff M79/2012 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2013] HCA 24; (2013) 252 CLR 336, per French CJ, Crennan and Bell JJ’s consideration at [32], [39], [40] and [42] of the crucial feature of s.195A – that it was matter for the Minister to judge whether it was in the public interest whether and for what purposes to exercise the power.

115. Should I be wrong, I consider that the Applicant was afforded procedural fairness in the exercise by the Minister of the revocation power of s.46A(2C) by the Revocation Decision. Procedural fairness is afforded when the procedure adopted is reasonable in the circumstances to afford an opportunity to be heard to a person who has an interest apt to be affected by the exercise of power: see SZSSJ at [82] – [83].

82 As the primary judge said at [118], it followed that she found that there was no jurisdictional error in the Revocation Decision, the SHEV application was invalid, and the Removal Decision was valid.

The notice of appeal

83 The amended notice of appeal is in the following terms:

Grounds of appeal

1. The Court erred in finding the exercise of the revocation power in s 46A(2C) Migration Act 1958 (the Act) was not subject to procedural fairness.

2. The Court erred in finding in the alternative that the appellant had been afforded procedural fairness in the exercise of the revocation power in s 46A(2C) of the Act.

3. The Court erred in finding the Minister did not make a personal procedural decision to consider the exercise of his powers under ss 46A or s 195A of the Act by way of the process set out at [10] of the Ministerial Submission.

4. The Court erred in finding that the second and third IRSR processes were not subject to procedural fairness, and that they were not ‘migration decisions’ subject to the jurisdiction of the Court under s 476(1) of the Act.

Orders sought

1. That the appeal be allowed;

2. That the orders of the Federal Circuit Court made on 7 May 2019 be set aside and in lieu thereof:

a. A declaration that the decision of the first respondent made 19 September 2017 under s 46A(2C) of the Act to revoke his determination to lift the bar under s 46A to allow the appellant to apply for a protection visa is contrary to law and invalid.

b. A writ of mandamus issue requiring the first respondent to determine the appellant’s application for a Safe Haven Enterprise (subclass 790) visa according to law.

c. An order in the nature of certiorari setting aside the first respondent’s decision to remove the appellant.

d. An injunction issue restraining the first respondent’s officers or agents from removing the appellant from Australia

Further or in the alternative to orders a - c:

3. A declaration that the second and third IRSR processes were unlawful and invalid, the appellant not having been afforded procedural fairness in relation to the assessments.

4. That the first respondent pay the appellant’s costs of this appeal and of the Federal Circuit Court proceedings.

5. Such further orders the Court deems fit.

The submissions of the parties

84 The appellant submitted that the primary judge erred, at [113], in finding that the exercise of the revocation power in s 46A(2C) was not subject to procedural fairness, and, at [115], in finding that, in the event that the Revocation Decision was subject to procedural fairness, the Minister had afforded the appellant procedural fairness. It followed, at [118], from each of these findings that there was not the jurisdictional error in the Revocation Decision that the appellant had claimed, and therefore the appellant’s SHEV application was invalid. The appellant submitted that his proposed removal was not required or authorised by s 198(2)(c)(ii) of the Migration Act, as he had made a valid application for a SHEV on 28 February 2018 which had not yet been finally determined. The validity of the SHEV application was not affected by the purported revocation of the lifting of the s 46A(1) bar by the Minister on 19 September 2017, the appellant submitted.

85 The appellant submitted that the presumption of procedural fairness was implied as a condition of the exercise of the statutory power and was not displaced. Section 46A(2C) was not a “dispensing” or “empowering” provision in the sense described in Plaintiff S10/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2012] HCA 31; 246 CLR 636; rather, the function of s 46A(2C) was to destroy existing rights, the appellant submitted.

86 As to legislative context, the appellant submitted that it was significant that s 46A(2A) allowed the Minister to specify a limited period within which the s 46A(1) bar was to be lifted, and that this limited period might apply only to certain classes of unlawful maritime arrivals, referring to s 46A(2B). As to the circumstances of an individual not being a mandatory relevant consideration in the exercise of the revocation power, the appellant submitted that individual circumstances were not necessarily inimical or irrelevant to a conception of the public interest any Minister might hold.

87 The appellant submitted that the primary judge was wrong to say, at [109], that “the Applicant was in the same position in the period immediately before the Revocation Decision as the plaintiffs in Plaintiff S10: see [80].” The Migration Act had enabled each of the plaintiffs in Plaintiff S10 to apply for a visa, the appellant submitted, and each application was considered by a departmental officer and by a Tribunal on merits review. The appellant submitted that he was barred from applying for any kind of visa.

88 Turning to whether procedural fairness was afforded, the appellant submitted that procedural fairness required that the appellant be put on notice of the case he had to meet, which meant identifying the particular statutory power under which the Minister would be acting and the public interest criterion for its exercise. Procedural fairness was not afforded, the appellant submitted, simply by putting the appellant on notice that the Minister might or would exercise an unidentified revocation power if the appellant did not lodge a visa application by a certain date. The Minister did not give the appellant a reasonable opportunity to be heard about why the revocation should not be exercised in his case, the appellant submitted. In addition to his actual claims for protection in his SHEV application, his reasons might have included his own statements, and assessments by medical health professionals which concurred with the IHMS psychiatrist’s “ongoing diagnosis of a panic disorder with agoraphobia” which “may impose a barrier to participating in his immigration processes and lodging applications”.