FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation [2019] FCAFC 115

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The cross-appeal be allowed.

3. The parties confer and file agreed or competing orders reflecting these reasons for judgment by 4:00pm on 19 July 2019.

4. The matter be remitted to the primary judge for any hearing or orders on the remedies to be awarded.

5. The appellants/cross-respondents pay the costs of the respondents/cross-appellants of and incidental to the appeal and the cross-appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GREENWOOD J:

Background

1 These proceedings raise an important question concerning the extent to which a patentee, by reason of the statutory grant of “exclusive rights” to “exploit the invention” and authorise others to do so in s 13 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the “Act”) can prevent a person who has acquired title to a patented product (either the first buyer or a subsequent buyer) from, put simply for present purposes, manipulating or “repurposing” (as it is described) the patented product for subsequent sale, and to prevent persons from importing such repurposed products into Australia for sale, and selling such products.

2 Assuming that an answer to the patentee’s claim of infringement by importation and sale of a “repurposed product” is a contended right of re-supply of “a product” deriving from the first sale of a patented product by the patentee (or its agents), a question arises as to the true source and scope of that right and whether an article emerging from the various steps constituting the so-called repurposing process might no longer remain characterised as a product derived from the first sale but rather a new article of manufacture reflecting an exercise of one of the exclusive rights conferred upon the patentee, that is, the right to “make” the product the subject of the patent: s 13(1), s 3, Schedule 1 of the Act.

3 Seiko Epson Corporation (“Seiko”) contends that the appellants’ (treated collectively for present purposes) infringed its patents in suit by importing, offering for sale and selling printer cartridges which embody each of the integers of claim 1 of each patent. The appellants, however, assert an implied licence derived from Seiko’s unrestricted sale of the original Seiko Epson cartridges. Those cartridges were later subjected to a sequence of steps described at [73] of the primary judge’s reasons and more fully described at section 6 of the primary judgment. Those steps had the effect of bringing into existence the articles imported, offered for sale and sold by the appellants. The primary judge found that the appellants did not hold an “implied licence” to do so as to products within categories 4, 5, 6 and 7 (of the table at [73] of the primary judgment) imported for sale and sold prior to April 2016. The primary judge held that the appellants did hold an implied licence as to products within the categories of products imported and sold after April 2016.

4 Calidad appeals from the orders of the primary judge relating to its current products. Seiko cross-appeals in relation to the dismissal of its case concerning Calidad’s former products.

5 These proceedings also raise an important question of whether the exclusive rights vested in the patentee in relation to a patent for an invention for a product, are exhausted at the point of first sale consistent with the United States Supreme Court authorities such as Impression Products Inc v Lexmark International Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1523 (2017); United States v Univis Lens Co., 316 US 241 (1942); Quanta Computer, Inc., v LG Electronics, Inc., 553 US 617 (2008); Kirtsaeng v John Wiley & Sons Inc., 568 US 519 (2013); Boston Store of Chicago v American Graphophone Co., 246 US 8 (1918); United States v General Elec. Co., 272 US 476 (1926).

6 However, in this appeal, we are asked by the parties not to examine the jurisprudential foundation for the doctrine of exhaustion as it applies in the United States and might apply in Australia should the High Court of Australia choose to adopt such a doctrine but rather, we are asked to proceed on the footing that for the purposes of patent law in Australia, the principles to be applied are those deriving from a decision of the Privy Council in the eleventh year of the 20th Century in National Phonograph Company of Australia Limited v Menck (1911) 12 CLR 15 (“Menck PC”) in which Lords Macnaghten, Atkinson, Shaw, Mersey and Robson (with the reasons read by Lord Shaw) reversed a 1908 decision of the High Court in National Phonograph Company of Australia Limited v Menck (1908) 7 CLR 481 (“Menck HC”). We are asked to take that course because the appellants “accept” that the Federal Court of Australia is bound by Menck PC “or, if not strictly bound, would follow that decision”: appellants’ submissions at para 7.

7 The appellants nevertheless assert that the primary judge (“PJ”) fell into error by failing to apply a doctrine of exhaustion of rights at the point of first sale but say that those grounds (grounds 6 and 7 of the notice of appeal) form part of the grounds of appeal simply for the purpose of preserving an opportunity for the appellants to contend before the High Court (should this proceeding ultimately be the subject of special leave to appeal to the High Court) “that the consequence of a patentee selling a patented article is that all rights in the article are completely exhausted” [emphasis added]. That was the position adopted by the majority (or plurality) in the High Court in Menck HC in 1908 consistent with the early United States authorities: Griffith CJ, Barton, O’Connor JJ, with a significant dissent by Isaacs J; and a separate judgment by Higgins J in apparent agreement with Isaacs J.

8 This question has not arisen squarely before the High Court in a patent case since 1908 although observations about the principles discussed in Menck PC were the subject of discussion in an important copyright case (although not a patent case) in Interstate Parcel Express Co. Pty Ltd v Time-Life International (Nederlands) B.V. (1977) 138 CLR 534 (“Time-Life”): see especially the observations of Gibbs J at 540-542; and Stephen J at 552-553. Although the subject matter of that decision concerns questions arising under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), the appellant in that case contended that the sale of books by or on behalf of the copyright owner imports a licence to sell them anywhere in the world and in order to support that proposition, the appellant called in aid the line of cases decided in relation to patents. That contention required their Honours to first consider the effect of those cases and the propositions they stand for as a matter of principle in patent law.

9 For my part, I accept, of course, that the question of whether an exhaustion of rights doctrine is to form part of the patent law of Australia on behalf of the citizens of this country is a matter to be determined by the High Court of Australia in the discharge of its role as the highest court of appeal at the apex of the Australian appellate structure, assuming their Honours grant special leave to appeal in the relevant class of case.

10 Having regard to the position taken by the appellants, submissions have not been directed to the Full Court about a contended exhaustion doctrine. The respondents, of course, do not therefore confront that proposition. It would not be appropriate to embark upon any consideration of that doctrine or the foundation principles developed by the United States Supreme Court which caused their Honours, in that country, to adopt it as an appropriate position in the patent law of the United States for the citizens of that country.

11 However, in relation to the question of whether the Federal Court of Australia is bound by Menck PC, it must be remembered that the statutory formulation considered in Menck PC and in Menck HC was the formulation of the grant contained in s 62 of the Patents Act 1903 (Cth), enacted 116 years ago. That section provided that the effect of a patent is to “grant the patentee the full power, sole privilege and authority, by himself [or herself], his [or her] agents, and licensees during the term of the patent to make, use, exercise and vend the invention within the Commonwealth” [emphasis added] in such manner as to the patentee seems appropriate so that the patentee “shall have and enjoy the whole profit and advantage accruing by reason of the invention during the term of the patent”.

12 The particular form and language of the grant is set out in the First Schedule to the 1903 Act. The 1903 Act was amended in 1906, 1909, 1910, 1921, 1930, 1932, 1933, 1935, 1946 and 1950. The whole of the Acts of 1903, 1909, 1921, 1930, 1933, 1935 and 1946 were repealed by the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) which was, in turn, repealed by the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). Much legislative activity has flowed under the Parliamentary bridge since the decision in Menck PC in 1911, including the consideration by the Executive and the Parliament of the report of the Industrial Property Advisory Committee dated 29 August 1984 entitled Patents, Innovation and Competition in Australia aspects of which were taken up in the formulation of the Patents Bill 1990 (Cth) (the “Bill”).

13 The present statutory formulation of the grant of rights is in these terms:

Exclusive rights given by patent

13. (1) Subject to this Act, a patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to exploit the invention.

(2) The exclusive rights are personal property and are capable of assignment and of devolution by law.

(3) A patent has effect throughout the patent area [as defined in Schedule 1 to the Act].

14 As to the term “exploit”, Schedule 1 to the Act provides this definition:

exploit, in relation to an invention, includes:

(a) where the invention is a product – make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things; or

(b) where the invention is a method or process – use the method or process or do any act mentioned in paragraph (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

15 An invention, of course, means any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention: s 3, Sch 1, of the Act. It is not necessary to recite the “archaic language” of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (Bristol-Myers v Beecham Group [1974] AC 646, Lord Diplock at 677) or its more contemporary reformulation seeking to translate some of the archaic language into a more modern formulation.

16 As to cl 13 of the Bill concerning the exclusive rights given by patent which became s 13 of the Act, the Explanatory Memorandum for the Bill as tabled in the Senate says this at para 24:

While the definition [of the term “exploit”] makes it clear that certain acts are capable of being held to infringe a patentee’s rights, it does not mean that a person who performs one of those acts will always be held to infringe. Clause 13 is not intended, in particular, to modify the operation of the law on infringement so far as it relates to subsequent dealings with a patented product after its first sale. This applies particularly where a patented product is resold or where it is imported after being purchased abroad. It is intended that the question whether such a resale or importation constitutes an infringement in a particular case will continue to be determined as it is now, having regard to any actual or implied licences in the first sale and their effect in Australia, and to what is often known as the doctrine of “exhaustion of rights” so far as it applies under Australian law.

17 Accordingly, it is necessary to consider the principles derived from Menck PC as they apply to the findings of fact in the case at hand and consider the source, scope and content of any implied licences that arise out of a sale of a product the subject of the patent or patents in suit.

The relevant facts within which the questions in issue arise

18 I will attempt to synthesise the material findings of fact as much as possible.

19 Seiko, the first respondent, is a manufacturing company which sells printer products including printer cartridges (including cartridges for inkjet printers) under the trade mark “Epson”. It sells or authorises the sale of these printer cartridges (described by the primary judge as the “original Epson cartridges”) worldwide. The original Epson cartridges embody the invention claimed in two patents in suit described as the “643 patent” and the “239 patent”. Eleven different types of original Epson cartridges are relevant to the proceedings. Each cartridge is compatible with one or more Seiko printers. When the ink in an ink cartridge runs out, the cartridge must be replaced. Seiko has a worldwide business that supplies replacement cartridges for its printers: PJ at [1] and [3].

20 Ninestar Image (Malaysia) SDN BHD (“Ninestar”) is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of generic printer consumables which includes toner and inkjet printer cartridges. It has been operating for over 13 years and supplies products to over 100 countries. Ninestar, for a fee, obtains used original Epson cartridges from third party suppliers who have collected them. The primary judge observes that it is unclear on the evidence whether the third party suppliers acquired the cartridges from the original consumers of the original Epson cartridges or otherwise obtained them. The primary judge found it likely that a portion of the original Epson cartridges have been sold or given, by the original consumers, to third party suppliers and that otherwise the used original Epson cartridges have come into the hands of third party suppliers by a variety of means including “perhaps, collection from recycling facilities”: PJ at [67]. Ninestar’s products include Epson printer cartridges originally sold by Seiko and which, once used and discarded by the customer, are collected (by whatever means) and restored by Ninestar to working condition. Ninestar also restores cartridges originally made by other original equipment manufacturers including HP, Canon, Brother, Lexmark and Dell: PJ at [64].

21 Ninestar has modified 11 different original Epson cartridges used and discarded by a Seiko customer to produce five different products imported into Australia and sold by Calidad Distributors Pty Ltd (“CDP”), the third appellant. CDP operates a business that competes with Seiko in the supply of replacement cartridges for Seiko’s printers in Australia. CDP sells five different restored cartridges described as the Calidad cartridges. They are the 250 cartridges; the 253 cartridges; the 258 cartridges; the 260H cartridges (high capacity volume); and the 260S cartridges (standard capacity volume). These products are promoted in Australia as “remanufactured Epson cartridges”: PJ at [3], [70] and [71].

22 Eleven different original Epson cartridges were modified by Ninestar to produce these five Calidad products. These five Calidad products are compatible with particular Epson printers sold by or with the permission of Seiko. The primary judge notes at [71] that the parties accepted that in broad terms there are four steps undertaken by or with the approval of Ninestar in the modification of the 11 original Epson cartridges so as to make these five Calidad products. The four steps are these (PJ at [71]):

(a) the preparation of the cartridge for ink refill (preparation);

(b) the refilling of the printer cartridge with ink not supplied by Seiko or with Seiko’s approval (refilling processes);

(c) the replacement, reprogramming or resetting of the memory chip (memory replacement/reprogramming);

(d) the research and development work in order to make alterations to the contents of the memory chip when it is in either “normal mode” or “test mode”.

23 The primary judge observes that some of the steps have changed over time for each of the Calidad cartridges and there are some variations to the steps applied to different models. In the result, although there are five Calidad products as earlier described, the proceedings addressed nine different categories of the Calidad products, each reflecting particular work performed so as to create a category of Calidad product. At [73], the primary judge sets out a table which identifies the nine categories of Calidad product. The first four categories (categories 1, 2, 3 and A) are concerned with cartridges sold after April 2016 (excluding the Calidad 260H product which was the original Epson cartridge described as T200XL), otherwise called the current products. The table as to those four categories identifies each of the steps taken to produce the particular Calidad category. The second part of the table sets out the Calidad cartridges sold by CDP before April 2016 (categories 4, 5, 6, 7 and B), otherwise called the former products. The table sets out the steps taken by Ninestar to produce each of those particular Calidad product categories. I will return to the table at [73] of the primary judgment later in these reasons.

24 There was (and remains) no dispute that each of the former and current Calidad products imported into and sold by CDP in Australia “fall within the scope of claim 1 of each patent”: PJ at [4]; appellants’ submissions at para 4.

25 Notwithstanding that concession, the primary judge notes at [4] that CDP contended that it had a complete answer to Seiko’s allegation (and that of its exclusive distributor, Epson Australia Pty Ltd) of patent infringement. The answer was said to be that Seiko released the original Epson cartridges “on the market” and, upon their sale, Seiko authorised, or is taken to have authorised, any purchaser or subsequent owner of the cartridges to treat them as an “ordinary chattel” and that Seiko “implicitly authorised Ninestar to refill and modify the original Epson cartridges, after which Ninestar was free to sell them to Calidad who was then free to import them into Australia and sell them”: PJ at [4]. That answer is said to derive from the application of Menck PC to the facts of the case. Alternatively, CDP contended that Seiko’s exclusive right to exploit the invention does not include the right to prevent the owner of the patented product from repairing or refurbishing it or from having subsequent dealings in that refurbished product including importing the product into Australia for sale.

26 At [200], the primary judge set out the integers of claim 1 of the 643 patent in these terms:

200. The 643 patent has 40 claims. Claim 1 provides as follows (for convenience, integer numbers have been added):

[1] A printing material container adapted to be attached to a printing apparatus by being inserted in an insertion direction, the printing apparatus having a print head and a plurality of apparatus-side terminals, the printing material container including:

[2] a memory driven by a memory driving voltage;

[3] an electronic device driven by a higher voltage than the memory driving voltage;

[4] a plurality of terminals including a plurality of memory terminals electrically connected to the memory, and a first electronic device terminal and a second electronic device terminal electrically connected to the electronic device, wherein:

[5] the plurality of terminals each include a contact portion for contacting a corresponding terminal of the plurality of apparatus-side terminals,

[6] the contact portions are arranged in a first row of contact portions and in a second row of contact portions, the first row of contact portions and the second row of contact portions extending in a row direction which is generally orthogonal to the insertion direction,

[7] the first row of contact portions is disposed at a location that is further in the insertion direction than the second row of contact portions,

[8] the first row of contact portions is longer than the second row of contact portions, and,

[9] the first row of contact portions has a first end position and a second end position at opposite ends thereof,

[10] a contact portion of the first electronic device terminal is disposed at the first end position in the first row of contact portions and

[11] a contact portion of the second electronic device terminal is disposed at the second end position in the first row of contact portions.

27 There is no dispute that if CDP makes good its contention at [25] of these reasons, that answer holds good for the claims of the 239 patent. The primary judge concluded that CDP infringed both patents in relation to the former Calidad products but not the current Calidad products. CDP appeals from the orders of the primary judge consequent upon those findings. The primary judge reached those conclusions by first identifying the legal principles to be applied in resolution of the dispute. The primary judge then isolated the questions that his Honour considered needed to be answered and then answered those questions having regard to the particular findings of fact.

28 The primary judge observed that:

(1) Section 13(1) of the Act confers an exclusive right on the patentee during the term to exploit the invention (and authorise others to do so) and that right, where the invention is a product, includes the right “to use it”.

(2) The exclusive right to use a product means that upon sale (or resale) the patentee “will have continuing control of the use” of a product the subject of a patent: PJ at [81].

(3) Thus, the patentee could “impose limitations” on the buyer’s use of such a product: PJ at [81]. Such a buyer could “never” consider himself or herself “entitled to all the usual incidents of ownership”: PJ at [81].

(4) However, this notion of a statutory right (by reason of the scope of the grant conferred by s 13(1) of the Act) to impose limitations upon the use of a patented product creates a “tension” between the normal attributes of ownership of goods and an entitlement in the patentee to exercise continuing control over “any use” of the patented product after the point of first sale: PJ at [81].

(5) One method of resolution of this tension is a construction of the scope of the statutory grant of the term “exploit” in relation to an invention where the invention is a product (as here, and as a matter of consistency where the invention is a method or process) that exhausts all things (rights) falling within the definition of exploit (which, of course, is an inclusive definition), at the point of “first authorised sale”: PJ at [82]. However, an exhaustion of rights doctrine is not part of the law of Australia.

(6) The tension is otherwise resolved according to the principles adopted in Menck PC.

29 As to those principles, the following matters should be noted.

30 The starting point is put this way in Menck PC at 22:

To begin with, the general principle, that is to say, the principle applicable to ordinary goods bought and sold, is not here in question. The owner may use and dispose of these as he thinks fit. He may have made a certain contract with the person from whom he bought, and to such a contract he must answer.

[emphasis added]

31 However, a buyer simply in his or her “capacity as owner” is not bound by any restrictions in regard to the use or sale of the goods “and it is out of the question to suggest [as Isaacs J suggests] that restrictive conditions run with the goods”: Menck PC at 22. Further, “[i]t would be contrary to the public interest and to the security of trade, as well as to the familiar rights attaching to ordinary ownership, if any other principle applied”: Menck PC at 22. The “real point of difficulty” is the “enforcement of that principle” without impinging upon the grant by the State of a right of property in the form of a patent monopoly “to make, use, exercise, and vend the invention … in such manner as to him seems meet”. This point of difficulty is described in this way:

This is, of course, with reference to the grant of the right as a sole right, that is to say, put negatively, with a power to exclude all others from the right of production, etc, of the patented article, and also with reference to the imposition of conditions in the transactions of making, using and vending, which are necessarily an exception by Statute to the rules ordinarily prevailing: Menck PC at 22.

[emphasis added]

32 The “doctrine” (adopted by Isaacs J and (probably) Higgins J in Menck HC in rejecting the majority view of an exhaustion of rights), to the effect that conditions imposed on the buyer by the patentee run with the goods would, if adopted, effect a radical change in the law of personal property: Menck PC at 23 and 24.

33 However, if the restriction upon alienation, use or otherwise of the goods purchased arises from the fact that the person has become the owner “with the knowledge brought home to him of the limitation of his rights of alienation or otherwise” [emphasis added], then “there seems to be no radical change whatever”. Such limitations “are merely the respect paid and the effect given to those conditions of transfer of the patented article which the law, laid down by Statute, gave the original patentee a power to impose” [emphasis added]: Menck PC at 24.

34 These principles were said (Menck PC at 24) to “harmonize” the rights of the patentee with the rights of the owner. One of those harmonizing principles is put this way (Menck PC at 24):

[W]here a patented article has been acquired by sale, much, if not all, may be implied as to the consent of the licensee to an undisturbed and unrestricted use thereof. In short, such a sale negatives in the ordinary case the imposition of conditions and the bringing home to the knowledge of the owner of the patented goods that restrictions are laid upon him [or her].

[emphasis added]

35 These harmonized principles are restated in this way (Menck PC at 28):

In their Lordships’ opinion, it is thus demonstrated by a clear course of authority, first, that it is open to the licensee, by virtue of his statutory monopoly, to make a sale sub modo [without restrictive conditions], or accompanied by restrictive conditions which would not apply in the case of ordinary chattels; secondly, that the imposition of these conditions in the case of a sale is not presumed, but, on the contrary, a sale having occurred, the presumption is that the full right of ownership was meant to be vested in the purchaser; while thirdly, the owner’s rights in a patented chattel will be limited if there is brought home to him the knowledge of conditions imposed, by the patentee or those representing the patentee, upon him at the time of sale.

36 The reference in that passage to “a clear course of authority” is a reference to the observations of the Lord Chancellor, Lord Hatherley, in Betts v Willmott (1871) L.R. 6 Ch. App., 239 at 245. That case concerned a circumstance where a patentee had a manufacturing facility in England and in France. The defendant sold in England a product embodying the integers of the patent. The product had not been manufactured by the patentee in England and the patentee could not prove that the product was not made in the patentee’s facility in France. If made in the patentee’s facility in France, could it be sold in England? Lord Hatherley L.C. said this at 245:

[W]here a man [or woman] carries on the two manufactories himself, and himself disposes of the article abroad, unless it can be shewn, not that there is some clear injunction to his agents, but that there is some clear communication to the party to whom the article is sold, I apprehend that, inasmuch as he has the right of vending the goods in France or Belgium or England, or in any other quarter of the globe, he transfers with the goods necessarily the licence to use them wherever the purchaser pleases. When a man [or woman] has purchased an article he [or she] expects to have the control of it, and there must be some clear and explicit agreement to the contrary to justify the vendor in saying that he has not given the purchaser his licence to sell the article, or to use it wherever he pleases as against himself. He cannot use it against a previous assignee of the patent, but he can use it against the person who himself is proprietor of the patent, and has the power of conferring a complete right on him by the sale of the article.

[emphasis in bold added]

37 It is also a reference (at Menck PC at 25 and 26) to the remarks of Cotton LJ in Société Anonyme des Manufactures de Glaces v Tilghman’s Patent Sand Blast Co. (1883) 25 Ch. D., 1 at 9 (“Tilghman’s case”) in these terms:

When an article is sold without any restriction on the buyer, whether it is manufactured under one or the other patent, that, in my opinion, as against the vendor gives the purchaser an absolute right to deal with that which he so buys in any way he thinks fit, and of course that includes selling in any country where there is a patent in the possession of and owned by the vendor.

[emphasis added]

38 As to the power to impose restrictions on the use of a patented article, the following remarks of Wills J in Incandescent Gas Light Co. Ltd v Cantelo 12 RPC 262 also formed part of that line of authority mentioned in Menck PC at 28:

The sale of a patented article carries with it the right to use it in any way that the purchaser chooses to use it, unless he knows of restrictions. Of course, if he knows of restrictions, and they are brought to his mind at the time of the sale, he is bound by them. He is bound by them on this principle: the patentee has the sole right of using and selling the articles, and he may prevent anybody from dealing with them at all, inasmuch as he has the right to prevent people from using them, or dealing in them at all, he has the right to do the lesser thing, that is to say, to impose his own conditions. It does not matter how unreasonable or how absurd the conditions are. It does not matter what they are if he says at the time when the purchaser proposes to buy, or the person to take a licence, “Mind, I only give you this licence on this condition”, and the purchaser is free to take it or leave it as he likes. If he takes it, he must be bound by the condition.

[emphasis added]

39 The following observations of Dowsett J in Austshade Pty Ltd v Boss Shade Pty Ltd (2016) 118 IPR 93 at [80] are, in my respectful view, a useful distillation of the principles derived from Menck PC. There are three propositions identified by his Honour.

40 The first proposition is this:

• [T]he principle applicable to ordinary goods bought and sold is that the owner may use and dispose of those goods as he or she thinks fit. Notwithstanding any agreement which such owner may have made with the person from whom he or she bought the goods (by which he or she is bound contractually), he or she is not bound, in his or her capacity as owner, by any restrictions concerning the use or sale of the goods. Hence it is, “out of the question” to suggest that any such restrictive conditions run with the goods. The rights of an intermediate owner in that “capacity” are to be distinguished from the contractual arrangements which may bind him or her in dealing with the person from whom the goods were acquired. The point is that the intermediate owner may give to his or her purchaser, good title to the goods, notwithstanding any contractual restriction imposed upon the intermediate owner at the time of his or her acquisition of the goods.

41 The second proposition is this:

• [T]he general doctrine of absolute freedom in the disposal of chattels of an ordinary kind is, in the case of patented chattels, subject to the restriction that the person purchasing them, having knowledge of the conditions attached by the patentee, which knowledge is clearly brought home to him at the time of sale, is bound by that knowledge and accepts the situation of ownership subject to the limitations. In other words, a patentee may bind the power of a purchaser to deal with the goods, but such limitation will only bind a subsequent purchaser from that purchaser if the former has, at the time or purchase, actual knowledge of the limitations.

42 The third proposition is this:

• [I]n the case of such a resale, it is not presumed that conditions imposed on the vendor by the patentee will bind the subsequent purchaser. Rather, the sale will be presumed to have vested the full right of ownership in the subsequent purchaser unless the conditions imposed by the patentee have been brought home to him or her at the time of sale. Hence it is not sufficient that the ultimate purchaser may know of the patent and its application to the goods acquired. There must be actual knowledge of the limitations imposed by the patentee at the time of the first sale.

43 In Time-Life at 541, Gibbs J thought it odd to describe the sale of an article as importing a licence in the buyer to use it. It seemed to his Honour “a misuse of words” to say that a person who sells an article consents to its being used “in any way that the buyer wishes”. However, his Honour also observed that the statement that a patentee who sells a patented article gives the buyer his licence to use it has often been repeated by distinguished judges and that Menck PC affirms that the consent or licence of the patentee to use an article might be implied from the sale of the patented article. His Honour at 541-542 also regarded the following statement of Buckley J in Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik v Isler [1906] 1 Ch. 605 at 610 as “a correct statement of the patent law”:

If a patentee sells the patented article to a purchaser and the purchaser uses it, he, of course, does not infringe. But why? By reason of the fact that the law implies from the sale a licence given by the patentee to the purchaser to use that which he has bought. In the absence of condition this implied licence is a licence to use or sell or deal with the goods as the purchaser pleases: Thomas v Hunt; Betts v Willmott. If the patentee sells, imposing no restriction or condition upon his purchaser at the time of sale, he cannot impose a condition subsequently by delivery of the goods with a condition indorsed upon them. … Unless the purchaser knows of the condition at the time of purchase and buys subject to the condition, he has the benefit of an implied licence to use free from condition.

[emphasis added]

[citations omitted]

44 In Time-Life, Stephen J at 549 regarded the principles derived from Betts v Willmott and Tilghman’s case (as explained in Menck PC) as being:

… confined to the quite special case of the sale by a patentee of patented goods and as turning upon the unique ability which the law confers upon patentees of imposing restrictions upon what use may after sale be made of those goods. If the patentee, having this ability, chooses not to exercise it and sells without imposing any such restrictions, the purchaser and any successors in title may then do as they will with the goods, for they are then in no different position from any purchaser of unpatented goods. But, to ensure that consequence despite the existence, albeit in the instance unexercised, of this power on the patentee’s part, the law treats the sale without express restriction as involving the grant of a licence from the patentee authorising such future use of the goods as the owner for the time being sees fit. The law does this because, without such a licence, any use or dealing with the goods would constitute an infringement of the patentee’s monopoly in respect of the use, exercise and vending of the patent. A sale of goods manufactured under patent is thus a transaction of a unique kind because of the special nature of the monopoly accorded to the patentee; the licence, whether absolute or qualified, which arises upon such a sale is attributable to the existence and character of that monopoly. Absent that monopoly, peculiar to patents, there is no occasion for any licence.

[emphasis added]

45 Before turning to the way in which the primary judge framed the questions to be answered in resolving the controversy at trial, it is necessary to note some features of the original Epson cartridges as sold by Seiko (or its agents or its exclusive distributor) and some aspects of the facts.

46 The original 11 Epson cartridges contained an “integrated circuit” (otherwise generally described as a “chip”) mounted on or connected to an “integrated circuit board”: PJ at [46]. One of the things a user (consumer) wants to know when using an inkjet printer and a printer cartridge is the progressive use of ink from the cartridge. Typically, the printer has a number of sensors to detect whether the cartridge is installed; the ink level in the cartridge; whether paper is in the tray; whether a paper jam has occurred etc. Typically, at the priority date (and as at the trial date) the common way to store information about the remaining level of ink in a printer cartridge was by means of an integrated circuit on the printer cartridge itself: PJ at [37].

47 Integrated circuits (of varying kinds) are commonly interchangeably called “chips”. They are simply a collection of electronic components arranged on semi-conductor material (typically silicon) so as to enable the circuit to control the flow of one or more electrical currents through the circuit to express some particular functionality. These integrated circuits called, relevantly, EEPROMs enable the stable storing of data (“non-volatile memory family” of integrated circuits) even when the power source to them is switched off. Storing information about the volume or level of ink contained in a cartridge in the memory in the integrated circuit on the cartridge itself allows a range of cartridges to be used (containing a small, medium or large volume of ink) interchangeably on the same printer. However, the only function of the memory on the printer cartridge is to store information and communicate it to the main processor in the computer when prompted. Storing information about ink levels on an integrated circuit (EPPROM) on a printer cartridge requires a communication protocol to be established between the cartridge EPPROM and the main processor in the printer. The instructions over a data line between the processor and the integrated circuit on the cartridge enables the processor to read the binary values stored on the chip on the cartridge. Similarly, the processor can “write data” to the memory chip on the cartridge over a data line by causing a “charge pattern” to be altered by changing the binary values (011010, for example) stored in the integrated circuit on the cartridge.

48 The particular relevance of these communications between the printer processor and the integrated circuit on the cartridge is that once the ink reservoir in the cartridge is below a threshold level, firmware in the processor will recognise the level and prevent the printer from printing the print job. The printer processor will not allow the print task to occur until an ink cartridge is installed whose integrated circuit (containing the relevant sequence of binary charges) affirms, to the processor, a level of ink in the cartridge to enable the print job to be completed: PJ at [44].

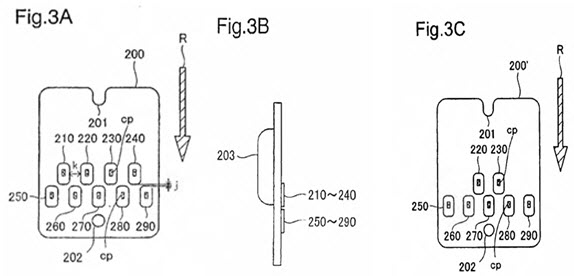

49 The primary judge (at [44]) observes that:

This means that, even if the ink cartridge is refilled, if the data stored on the memory on the cartridge still indicates an inadequate ink level, the main processor will recognise the ink cartridge as empty and will prevent the print job from occurring.

50 And at [45] the primary judge observes that:

In addition to storing binary code about the ink levels, the memory on the cartridge may also have fields that relate to other information that is communicated to and interpreted by the main processor in a similar manner to that described above. This could include, for example, the type of ink, the colour of ink, the brand of the cartridge, the date of manufacture etc. The memory could also contain a field relating to the serial number of the cartridge, which would enable the main processor to determine when a cartridge has been changed.

51 Returning to the Seiko Epson cartridges specifically, each of the 11 original cartridges contain an integrated circuit (chip) connected to a circuit board although different models have different chips resulting in differing compatibility between printers and cartridges: PJ at [46]. Original Epson cartridges are designed so that a compatible printer is able to read and process data in the chip. The chip stores data such as “volume of ink, the cartridge, date of manufacture and model number”: PJ at [47]. Each chip is comprised of an array of individual memory cells each storing a single binary “bit” of information (0 or 1) at a unique location on the chip determined according to the state of the electrical charge according to the absence (binary bit, 1) or the presence (binary bit, 0) of electrons: PJ at [50].

52 When an Epson cartridge is in operation in a printer, the cartridge chip is in “normal mode”. After manufacture, the chip is operated in “test mode”: PJ at [51]. The primary judge observes at [62] that ultimately the parties were not in substantial dispute about the sequence of steps taken by Ninestar to modify the Epson cartridges. The particular steps taken in relation to the relevant original Epson cartridge to bring into existence each category of Calidad product (the current products: categories 1, 2, 3 and A); the former products: categories 4, 5, 6, 7 and B) are described in detail in the reasons of the primary judge. It is not necessary to set out all of the detail of that analysis here. These things, however, should be noted.

53 As already mentioned, Ninestar “obtains” “used original Epson cartridges” (originally sold by Seiko or its agents) from third party suppliers: PJ at [67]. Those suppliers have either “collected them” by acquiring them from the “original consumers” (original users of the patented product) “or otherwise” (perhaps from recycling bins). The primary judge found that at least some of the original cartridges were sold or given to third party suppliers by those consumers. Some may have been collected from recycling bins. When Ninestar acquires them, the information stored in the memory chip on each cartridge records that the cartridge is “used”. Placing the cartridge (with memory cells storing a sequence of 0s and 1s in a charge arrangement determined by interactions between the processor and the cartridge’s integrated circuit during the working life of the original Epson cartridge), in a compatible printer, will result in the memory chip in the cartridge telling the printer processor that the cartridge is “empty”: PJ at [68].

54 At this point, the printer cartridge, as manufactured, as a product embodying the “invention” exhibiting all of the integers of each patent in suit, has reached the end of its useful life. It is a spent force, as compared with the state of the cartridge during its working life as an original Epson cartridge. The cartridge chip tells its symbiotic printer that it can no longer do its job of providing a reservoir of ink for transmission onto a page to produce the image or text that the consumer wants the printer to produce and the chip in the cartridge disables the printer from performing the print function.

55 Nevertheless, the cartridge, exhausted of ink, remains a “printing material container” adapted to be attached to a printing apparatus as contemplated by integer 1 of each patent and it continues to exhibit each of the integers 2 to 11 as set out at [26] of these reasons. Because it is exhausted of ink, it is no longer capable, notwithstanding the presence of all of the integers of the claims, of enabling the printing function of the processor.

56 However, the cartridge, discarded or sold by the original consumer, once gathered in by Ninestar, is subjected to the steps generally described at [22] of these reasons. Put simply, Ninestar “prepares” the cartridge so as to enable it to be refilled with ink by doing particular things to the physical cartridge/container. It then refills the cartridge with ink not supplied by Seiko or its agents. It then either replaces the memory chip on the cartridge (storing the digital arrangement of bits reading “empty”) with a new chip or it resets the existing chip to enable it to function in “normal mode” with refilled ink. It then operates the cartridge in “test mode” and “normal mode” to be satisfied of the alterations made, or to be made, to the content of the memory chip to enable it to operate in either mode (a “research and development” step).

57 All of this results in “a repurposing” of the original cartridge to enable it, in its repurposed form, to function in a way that exhibits each of the integers of the two patents set out at [26] of these reasons even though it may also exhibit other features, as “a product”, in addition to those features represented by the integers of claim 1 of each patent. In her Honour’s reasons in this appeal, Jagot J has set out the table from [73] of the primary judge’s reasons which identifies each Calidad product; the original Epson product from which it was derived; and a summary of the steps taken by Ninestar to “repurpose” the original cartridge so as to produce the Calidad product. Her Honour also sets out the relevant findings of the primary judge concerning the modifications made to the various categories of cartridges. It is not necessary to set those matters out again here. Jagot J also sets out the primary judge’s discussion of the two patents. The primary judge recognised, of course, that the parties proceeded on the footing that there is no material difference in the disclosures in the body of the specification of the 643 patent and the 239 patent and there is no material difference between claim 1 of the 643 patent and the content of claim 1 of the 239 patent. Thus, the primary judge’s discussion was confined to the 643 patent as a convenient way of describing the patent specification and the integers of claim 1 in each case. Again, it is not necessary to set those matters out here.

58 As earlier mentioned, it is common ground that the products imported into Australia, offered for sale and sold by CDP, exhibit each of the integers of claim 1 of the 643 and 239 patents. The acts of infringement relied upon by Seiko for the purposes of s 120 of the Act as an infringement of Seiko’s exclusive rights conferred by s 13 are those acts of importing a product (where, as here, the invention is a product), keeping it for sale, offering it for sale and selling the product, all of which fall within the definition of “exploit” in Sch 1, for the purposes of s 13 of the Act. Calidad answers that claim by saying that Seiko sold the Epson cartridges without imposing any restrictive conditions or limitations on the use that might be made of the patented product by the buyer (or, for that matter, without imposing any restrictive limitations concerning any of the acts falling within the definition of exploit). Calidad says that no restrictive conditions or limitations were imposed on it even if Seiko imposed restrictions on its buyer. Calidad says that each of the acts of infringement relied upon by Seiko as falling within s 13 of the Act are comprehended by a licence arising upon the sale of the patented product without restriction. That licence entitles, it is said, CDP to import the article under challenge exhibiting the integers of claim 1 in both patents; to keep the article for sale; to offer it for sale; and to sell it.

59 Seiko says that a licence arising upon a sale by it or its agents of the patented product, without any restrictive conditions or limitations (although it asserts that the very configuration of the cartridge contained “inherent restrictive conditions constituting relevant limitations”), gives rise to a very limited licence in the buyer to “use” the product the subject of the patent, to resell (and probably to import it into Australia) but not to subject the product to the sequence of steps described at [22] of these reasons and also at [73] of the primary judge’s reasons which, when properly examined, can only be characterised, it is said, as an act of manufacturing (otherwise called “repurposing”) of the original Epson cartridge by Ninestar so as to bring into existence a new article of manufacture which, so made, exhibits all of the integers of claim 1 of each patent.

60 At that point, Ninestar is said to be exercising Seiko’s s 13 exclusive right of “making” a product “in relation to the invention” (using the introductory words in the definition of exploit), exhibiting each of the claim 1 integers. Calidad is said to be infringing each patent by importing, keeping for sale, offering for sale and selling that product. Calidad also says that the various steps undertaken by Ninestar also amount to undertaking “repairs” to, or “refurbishment” of, the product sold by Seiko and those acts fall within the licence enjoyed by the buyer of the original Epson cartridge such rights not expressly withheld by Seiko at the time of sale to its buyer.

61 Calidad says that Seiko’s grant of exclusive rights, in these circumstances, does not include a right to prevent Calidad from importing, keeping for sale, offering for sale and selling a repaired or refurbished product. Seiko says that the steps undertaken by Ninestar are not properly characterised as repairing or refurbishing the Seiko product and CDP’s conduct of importing, keeping, offering and selling the product does not fall within the scope of any implied licence recognised by law.

62 In determining whether CDP enjoyed a licence to import for sale, keep for sale, offer for sale and sell, any of the products in the product categories set out in the table at [73] of the primary judgment, the primary judge was required by Menck PC, to answer the following questions in order to resolve the controversy between the parties.

63 First, did the patentee, Seiko, either by itself or its agents, impose or attach any restrictive conditions on the sale of the patented products in its dealings with its buyer?

64 Second, if so, what is the content of the relevant restriction?

65 Third, if so, was knowledge of the restriction “clearly brought home” to that buyer?

66 Fourth, since any restrictive condition, clearly brought home to Seiko’s buyer, does not “run with the goods” and an intermediate owner may give good title to the goods to his or her buyer notwithstanding any restriction imposed on the seller, has, in fact, any restriction adopted by Seiko and clearly brought home to its buyer, also been clearly brought home to CDP?

67 Fifth, if no restriction was imposed on the sale of the patented product by Seiko or its agents, what exactly is the scope and content of any licence enjoyed by the buyer (and each and every subsequent intermediate buyer of the patented product), implied by law? In other words, the licence implied by law (if any) is a licence to do what exactly?

68 In my respectful opinion, the primary judge asked and answered the first four questions but asked and answered an entirely different question so far as question 5, as required by Menck PC is concerned. Rather than examine the true scope and content of any licence arising in Seiko’s buyer (capable of being exercised by subsequent buyers), in all the circumstances, the primary judge examined a question of whether an implied licence was brought to an end, extinguished or terminated by the conduct of Ninestar in making modifications to the original Epson products: PJ at [164] and particularly at [178]. The question that must be answered as required by Menck PC is what exactly is the scope and content of any licence in the buyer (and subsequent buyers) arising out of the sale by the patentee or its agents of the product the subject of the invention (and thus, the claims defining the monopoly), when no limitation or restriction is imposed at the time of that sale.

69 The conduct complained of either falls within the scope of a licence or it does not.

70 In this case, the primary judge found that although Seiko might have imposed, expressly, some restrictions or limitations on the buyer of the original Epson cartridges at the point of sale, “[f]or its own reasons, it has chosen not to”: PJ at [134].

71 Next, the primary judge considered whether the original Epson cartridges sold by Seiko or its agents, were sold subject to restrictive conditions imposed on the buyer built into the memory chip of each original Epson cartridge such that the “condition”, deriving as a matter of inference from the physicality and functionality of the memory chip in the cartridge (and, in turn, the cartridge’s relationship with the printer) is that “the original Epson cartridge is not to be used in a relevant Epson branded printer where at least one of the following circumstances applied: (a) the ink in the original Epson cartridge has dropped below a threshold level; (b) the cartridge has already been ‘used’ and is ‘empty’; and (c) where applicable, the original Epson cartridge is not compatible with the Epson branded printer”: PJ at [120].

72 Seiko contended that these restrictive “conditions” are programmed into each memory chip to give “effect” to the “restrictive conditions and physically embody them”. For the reasons identified at [127] to [137], the primary judge rejected the “inherent restrictive conditions” argument. The primary judge was correct to do so.

73 Next, the primary judge found at [128] to [143] that no restrictive conditions were brought home to Calidad. The primary judge was correct to so find.

74 Having addressed those matters, the primary judge described as “the elephant remaining in the room” the “fact” of modifications having been made by Ninestar to the original Epson cartridges and Calidad’s importation of the “modified products” (being the products under challenge in the principal proceeding). The question the primary judge posed was: to what extent do the modifications affect the implied licence? (PJ at [144]).

75 As to the fact of the modifications, I gratefully accept the detail of those modifications as described by Jagot J in her Honour’s reasons in this appeal drawn from the findings of the primary judge and the subject of her Honour’s further analysis of the modifications. It is not necessary for me to set out those matters again here.

76 As to the scope and content of any licence, the foundational principles are to be found in Menck PC as earlier identified but also in the affirmation of those principles by Gibbs J and also Stephen J notwithstanding that the discussion of the question as to the scope of an implied licence arising for the purposes of patent law, did not arise for determination in quelling a controversy between parties concerning the terms of an implied licence of a patent. The decision in Time-Life concerned questions arising in relation to the law of copyright. At the moment in time when their Honours in Time-Life were examining the notion of an implied licence so far as the patent law of the Commonwealth is concerned in order to address the argument raised by analogy to the patent law authorities, the statutory terms of the grant of rights were those determined by the Patents Act 1952 (Cth).

77 Section 13 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) frames the grant in terms of an exclusive right to exploit and the term “exploit”, where the invention is a product, disposes of the old word “vend” and comprehends (although the identified classes of rights are expressed in inclusive terms) particular acts. They are: to make the product; to hire the product; to sell the product; to otherwise dispose of the product; to offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of the product; to use the product; to import the product; to keep the product for the purpose of “doing any of those things”.

78 Those are the acts included within the term exploit in relation to “an invention” where the invention is a product. The specification for the patent application must disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art; disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; and end with “a claim or claims defining the invention”: s 40 of the Act.

79 Thus, the “invention” is defined by the claim or claims.

80 The claim or claims defining the invention “must be clear and succinct and supported by matter disclosed in the specification”: s 40(3). The claim or claims must relate to one invention only: s 40(4).

81 When s 13 of the Act grants a patentee the exclusive rights to exploit the invention (and to authorise others to do so), those exclusive rights are concerned with the invention as defined by the claim or claims and where the term “exploit” uses the phrase, “in relation to an invention, includes, where the invention is a product”, the term “exploit” is contemplating an invention defined by the claim or claims relating to one invention only.

82 Where a patentee (or its agents) sells a product where the invention is that product all of the rights described at [77] of these reasons comprising the statutory grant are reserved to the patentee. The patentee, at the point of first sale of such a product, might elect to prescribe the things the buyer is able, or not able, to do with the product so purchased. The product might be sold, for example, on terms that the buyer can “use” the product but not “sell” or “hire” or “otherwise dispose of” the product or “keep it” for the purpose of doing anything other than using the product. However, in the absence of any prescription by the patentee or its agents (that is, any form of withholding) at the point of first sale, the buyer acquires a licence of the patent to exercise in relation to the product (being the expression of an invention defined by a particular claim or claims), “all of the normal rights of an owner including the right to resell” [emphasis added]. That formulation is drawn from Blanco White as a distillation of the effect of the earlier authorities including Menck PC and affirmed by Gibbs J and Stephen J in Time-Life as a correct statement of the patent law in this country: see [43] and [44] of these reasons. That right has also been described by Cotton LJ as “an absolute right to deal with that which he [or she] so buys in any way he [or she] thinks fit …”: see [37] of these reasons.

83 If the scope of the patent licence implied by law is understood, consistent with Menck PC and the authorities already discussed, by reference to “all the normal rights of an owner” or the “absolute right” to deal with the product as the buyer thinks fit, that right would bring within the scope of the implied licence, rights which would fall within the statutory description of “exploit”, to this extent: to “hire, sell, otherwise dispose of the product, offer to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things”.

84 The scope of the implied licence, however, does not include a right to “make” the product being a right exclusively reserved to the patentee. The “owner” of a product, where the invention defined by a claim or claims, is that product, does not enjoy, by reason of ownership, a right to make an infringing product.

85 Once Ninestar undertook modifications to the original Epson cartridges which are properly characterised as making an article constituting a product embodying the integers of a claim defining Seiko’s invention, Ninestar stepped outside the scope of the licence. The licence did not come to an end by reason of the modifications. Nor was it discharged or repudiated by Ninestar’s conduct. The scope and content of the licence simply did not comprehend an implied licence in the buyer or Ninestar or anybody else to subject the original Epson cartridges to a sequence of modifications so as to bring into existence a new article of manufacture the result of which, properly characterised, is a “making” of a product the subject of Seiko’s invention defined by reference, relevantly, to claim 1 of the 643 patent and the 239 patent.

86 Calidad’s entitlement to import the modified product so described above rises no higher than the limitations in the implied licence relating to Ninestar’s conduct. CDP has imported into Australia for sale, kept for sale, offered for sale and sold, a product which does not fall within the scope and content of the implied licence. Calidad has thus infringed Seiko’s patents. Apart from these observations, I otherwise agree with the observations of Jagot J and Yates J on the remaining questions in issue in the appeal.

87 The appeal ought to be dismissed and the cross-appeal allowed, having regard to the content of the modifications as described by Jagot J.

I certify that the preceding eighty-seven (87) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Greenwood. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JAGOT J:

1. The appeal and cross-appeal

88 The appeal and cross-appeal with which these reasons for judgment deal concern the sale of printer cartridges. The appellants, referred to as Calidad, imported printer cartridges for sale in Australia. These cartridges had been originally manufactured and sold by the first respondent/first cross-appellant, Seiko, and, after use, the cartridges had been discarded, collected and modified overseas by a company unrelated to Calidad to enable reuse and sold to Calidad to enable importation and sale in Australia.

89 Seiko contended that Calidad’s conduct of importing, offering to sell and selling the re-purposed printer cartridges infringed Australian Patents Nos 2009233643 and 20123219239 respectively. Calidad contended that it did not infringe the patents because Seiko’s unrestricted sale of the cartridges meant that Calidad had an implied licence in respect of all cartridges. The primary judge held that Calidad had an implied licence authorising its conduct in respect of some of the cartridges and did not have such a licence in respect of other of the cartridges, depending upon the extent and character of the modifications of the cartridges necessary to make them capable of re-use.

90 In the appeal and cross-appeal Calidad and Seiko both contended that the primary judge was in error, Calidad’s position being that the implied licence applied to all of the cartridges and Seiko’s being that the implied licence did not apply to any of the cartridges.

91 I consider that Calidad’s appeal should be dismissed and Seiko’s cross-appeal allowed. The implied licence arising on Seiko’s unrestricted sale of the printer cartridges did not extend to any of the modifications necessary to enable the cartridges to be re-used. The modifications did not amount to the repair of any cartridge. Rather, in each case, the totality of the modifications constituted the making of a new embodiment of the invention claimed in the patents, being conduct outside the scope of the licence implied by Seiko’s act of sale without express restrictions brought to the notice of the original purchasers of the cartridges at the time of sale.

2. The primary judge’s reasons

2.1 Introductory matters

92 The primary judge’s reasons in Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403; (2013) 133 IPR 1 disclose all relevant primary facts. I adopt the same abbreviations as the primary judge.

93 As the primary judge explained, Seiko sells or authorises the sale of printer cartridges (original Epson cartridges) worldwide. The original Epson cartridges embody the invention in each of Australian Patents Nos 2009233643 and 20123219239. After initial sale and use, third parties including Ninestar Image (Malaysia) SDN. BHD (Ninestar) modified the cartridges to enable them to be filled with ink and re-used, and then sold the cartridges to Calidad which imported them and sold them in Australia: [1].

94 The primary judge described the relevant issue in this way at [2]:

The central dispute in these proceedings concerns the right of a patentee to control or limit what may be done with a patented product after it has been sold. This gives rise to consideration of the intersection of the general rights of property ownership in a chattel once sold, and the monopoly rights conferred on a patentee under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Act). When a patentee sells a chattel that embodies an invention claimed in a patent, can the patentee restrain the subsequent use made of it by a purchaser or a successor in title to the purchaser? This case explores that question…

95 The primary judge identified that 11 different types of cartridges are relevant to these proceedings. Each is compatible with one or more printers. As sold by Seiko, the cartridges are not capable of re-use and when the ink in any cartridge runs out the cartridges need to be replaced. The primary judge continued at [3]:

… Seiko has a lively, worldwide business that supplies replacement ink cartridges for its printers. Calidad operates a business that competes with Seiko in the supply of replacement ink cartridges for Seiko’s printers in Australia. The Calidad products are sold under 5 different Calidad product numbers (250, 253, 258, 260H and 260S) (Calidad products). Eleven different original Epson cartridges (T0711, 125, 126, 18, ICLM50, 98, 73N, 133, 138, T200 and T200XL) were modified by Ninestar to produce one or other of the Calidad products. To complicate matters, different modifications were made at different times.

96 While the appeal and cross-appeal concern only the alleged infringement of the patents, the primary judge was burdened with other claims which are no longer pressed. To the extent patent infringement is concerned, the primary judge said this at [4]:

… Seiko contends that Calidad infringes the claims of its patents by importing and selling the Calidad products. Calidad accepts that its products fall within the relevant claims of the patents, but submits that it has a complete answer to the allegation of patent infringement based on the fact that Seiko released the original Epson products on the market and, upon their sale, authorised any purchaser and subsequent owner of the cartridges to treat them as an ordinary chattel. More particularly, Calidad submits that Seiko implicitly authorised Ninestar to refill and modify the original Epson cartridges, after which Ninestar was free to sell them to Calidad who was then free to import them into Australia and sell them.

97 The primary judge explained his conclusion at [4] in these terms:

… In the United States, upon the first sale of a product that embodies a claimed invention, the patent rights in that product are said to be exhausted, which means that the patentee can no longer exert control over the product; Impression Products, Inc. v Lexmark Intern., Inc. 137 SCt 1523 (2017) (Lexmark). In Australia, a different principle has developed which arises from National Phonograph Co of Australia Ltd v Menck (1911) 12 CLR 15 (Privy Council) (National Phonograph). Applying the principles set out in that case, I have found that Seiko’s infringement claim succeeds for Calidad’s past range of products, but not in respect of its current products…

98 The primary judge also noted at [10] that the parties agreed that “it was only necessary for the Court to consider one claim of one patent in order to determine the patent infringement issues (being claim 1 of the 643 patent)”.

2.2 The technology

99 It is sufficient to adopt the primary judge’s description of the technology at [24] to [40], the most salient parts of which are set out below.

100 “A printed circuit board or integrated circuit board is a non-conductive material (such as plastic or fibre glass) that has electronic components mounted onto it. The electronic components are connected together to form one or more working circuits or assemblies via strips of a conducting material (such as copper), which are printed or etched onto the board (also known as ‘traces’)”: [24].

101 The electrical components on a printed circuit board generally include traces, pads, one or more integrated circuits which connect to the board via leads, and “discrete electronic components (such as, for example, transistors, capacitors, inductors, light emitting diodes (‘LEDs’))”: [25].

102 “Integrated circuits (also known as ‘chips’) are a collection of electronic components arranged on a piece of semi-conductor material (such as silicon). The components are connected in such a way to enable the circuit to control the flow of one or more electrical currents through the circuit in order to achieve some useful function”: [26].

103 “Piezoelectric devices are devices that are made of certain materials (for instance ceramics or quartz) which mechanically respond when the voltage is applied and removed. They generally require high voltages and both the high voltage requirement and the fact that they respond mechanically when a voltage is applied means that piezoelectric devices are not generally built into integrated circuits”: at [28].

104 “The electrical currents that flow through an integrated circuit and between integrated circuits and/or other discrete components on one or more printed circuit boards often constitute digital information in the form of bits, which are the smallest unit of data, comprising single binary values, either 0 or 1”: at [29].

105 “Integrated circuits (and the boards on which they sit) can be designed to perform a number of different functions. For example, in relation to printers, they can include memory, which stores digital information, and communication devices between the printer and the computer (for example in a Universal Serial Bus (USB), or Ethernet)”: [30].

106 “Short circuiting is a problem for any electrical circuit. Short circuiting occurs when an accidental path is created in an electrical circuit, which results in an electrical current moving down an unintended path … In cases where a high voltage is directed onto a low voltage circuit, this can also cause the components in the low voltage circuit to fuse, thereby rendering it (and consequently the electrical device) unusable. This is because modern integrated circuits, which tend to be powered at quite low voltages, are susceptible to damage from higher than specified voltages”: [31].

107 “An electronic printer is a device that takes an electronic representation of an image and produces an impression of that image on a medium (such as paper). Printers in the Australian household consumer market generally include inkjet and laser printers. Inkjet printers have a number of very small nozzles through which liquid ink is forced, in the form of small droplets, onto the paper. Laser printers produce an image electrostatically on an intermediate surface. That electrostatic image attracts toner and applies it to the paper, using heat to set the toner onto the paper”: [32].

108 “Inkjet printers (as well as most other printers) comprise hardware and firmware. Hardware is the physical machinery that exists inside the printer. Firmware is the software or set of instructions programmed onto the hardware. Electronic printers generally also need to be associated with a printer driver, which is a piece of software commonly installed on the computer that is connected to the printer”: [33].

109 The key aspects that inkjet printers commonly include are, as described in [34]:

(a) a power source, which includes a converter that converts the mains electricity (which in Australia is 240 volts) to a lower voltage that is useable by the printer hardware;

(b) a communications interface which provides an electrical or wireless interconnection with a computer (this could be via, for example, USB, Ethernet, Wireless network (“wifi”) or Bluetooth technology);

(c) a main processor, which would typically be an integrated circuit on a printed circuit board of the type described above, that handles all the basic system functions that control the printer mechanism and convert the image data into ink ejection control signals.

(d) the main processor will have some memory which may be on the same integrated circuit or an external integrated circuit on the printed circuit board. A memory is an integrated circuit that commonly contains cells that store electrical charge (which represents the binary data that I refer to above) and circuitry to read and write the electrical charge to the cells. The main processor addresses cells to read and write binary data. The pattern of the bits represents the digital data;

(e) one or more ink cartridges (colour inkjet printers commonly utilise four colours, cyan, magenta, yellow and black; the colours will commonly be housed in four separate cartridges, however, others have multi-colour cartridges with separate ink orifices for each colour);

(f) a printhead assembly, which contains the components (including the nozzles referred to above and the heating element or piezoelectric device). The printhead assembly ejects the ink from the ink cartridges onto the page (in some cases the printheads are located in the ink cartridges but in other cases the printheads are located on the printer itself). The printhead assembly, if separate from the ink cartridge, commonly includes a needle designed to pierce the ink cartridge to enable ink to flow, via tubes and sometimes a filter, down to the nozzles, where a heating element or piezoelectric device cause droplets of the ink to be pushed out of the nozzles onto the paper;

(g) a carriage, which holds the ink cartridges and printhead assembly, that is attached to a mechanism to move the carriage (including the ink cartridge and the printhead assembly) along the width of the paper;

(h) a feed paper mechanism, which commonly includes paper input and output trays and one or more rollers and motors that interact to feed the paper through the printer; and

(i) a control panel to allow the user to interact with the operation of the printer.

110 The inkjet printer may also have, as described at [35], a number of sensors to detect (for example):

(a) whether the ink cartridges are installed in the printer;

(b) the ink levels in the printer cartridges;

(c) whether the lid of the printer is open or closed;

(d) whether there is paper in the input tray;

(e) whether there is too much paper in the output tray; and

(f) whether there is a paper jam in the printer.

111 The primary judge explained:

37 There are many ways in which the information about the remaining ink levels can be stored. However, a common way as at December 2005 (priority date) and today was to store the remaining ink level information on an integrated circuit on the printer cartridge itself. These types of integrated circuits are called EEPROM, and form part of a non-volatile memory family. The data stored in the memory in this family can be retained by the integrated circuit even when it is not powered (another example of a type of memory that falls into this class is a flash drive, also known as a USB memory stick).

38 By storing the information about the ink levels in a memory on the printer cartridge, the information about how much ink is in the printer cartridge is transportable with the cartridge, so the ink information is retained even if the cartridge is removed and replaced or moved to another printer.

39 Having memory on the ink cartridge itself also allows physically identical ink cartridges containing different amounts of ink (for instance small, medium and large volume cartridges) to be sold and used in the same printer. This is because the available ink volume can be determined from information written to the memory on the cartridge.

40 Storing the information concerning the ink levels on an integrated circuit on the printer cartridge requires a communication protocol to be established between the memory on the cartridge and the main processor in the printer… The information on the memory is stored as bits, i.e. as a series of binary numbers (0s and 1s), which is described above.

2.3 The original Epson products

112 “The original Epson cartridges are cartridges sold by or with the permission of Seiko and have the Epson model numbers T0711, 125, 126, 18, ICLM50, 98, 73N, 133, 138, T200 and T200XL. They contain an integrated circuit chip mounted on or connected to a printed circuit board (or integrated circuit board). Different models of the original Epson cartridges have different types of memory chips located on the rear of the integrated circuit boards, and have differing compatibility with Epson printers”: [46].

113 “Original Epson cartridges are designed so that a printer with which they are compatible is able to read and process the data in the memory chip. The memory chips store information regarding the printer cartridge, such as the volume of ink, the status of the cartridge, its date of manufacture and model number. Each category of information is stored in its own memory address on the memory chip”: [47].

114 “The memory chips in the Epson cartridges have two different modes, ‘normal’ mode and ‘test’ mode. When in operation in the printer, a printer cartridge’s chip will be in normal mode. The ‘test mode’ is accessed when testing the chips after manufacture and when certain types of data in certain types of Calidad products is re-written”: [51].

2.4 The Calidad products

115 The original Epson cartridges have been sold by or with the permission of Seiko: [66]. Ninestar, for a fee, obtains used original Epson cartridges from third party suppliers who have collected them. The primary judge said that “it is likely that a portion of the original Epson cartridges have been sold or given by the consumers to the third party suppliers, and that otherwise they have come into the hands of the third party suppliers by a variety of means, including, perhaps, collection from recycling facilities”: [67].

116 As the primary judge explained:

68 At the time when Ninestar acquires the original Epson cartridges, the information on the memory chip records that the cartridge is “used” such that when it is inserted into a compatible printer, the printer will not work because the information conveyed from the memory chip to the printer is that the cartridge is empty.