FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Minister for Home Affairs v Ogawa [2019] FCAFC 98

Table of Corrections | |

In [21], “(1)”, “(2)” and “(3)” has been replaced with “(a)”, “(b)” and “(c)” respectively |

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

COLLIER J:

1 I am very grateful that I have had the opportunity to read in draft the judgment of Reeves J, and the joint judgment of Davies, Rangiah and Steward JJ, in this matter.

2 I agree with the reasons of Reeves J, and support the orders his Honour proposes.

I certify that the preceding two (2) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Collier. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

REEVES J:

3 I have had the benefit of reading in draft form the reasons for judgment of the majority. Subject to the following observations, I agree with their Honours’ reasons and conclusions with respect to the unreasonableness issue raised by appeal ground 2. That is to say, I agree with their Honours that the primary judge erred in holding that the Minister’s decision concerning the petition Dr Ogawa submitted to the Governor-General seeking a pardon was legally unreasonable.

4 The observations I would wish to add on that issue are as follows. The prerogative to which Dr Ogawa’s petition was directed, namely the prerogative of mercy, is entirely within the remit of the Executive. It may therefore be exercised by it for legal, or non-legal reasons, including for political reasons (see Osland v Secretary, Department of Justice (2008) 234 CLR 275; [2008] HCA 37). That being so, it is difficult to see how the Minister could be expected to assess from its contents whether it would be likely to succeed in gaining the pardon it sought. This, all the more so, where the Minister was only one member of the Executive and he was not the Minister responsible for the Department of the Executive that usually handles petitions of this nature (the Attorney-General’s Department). It is true that the Minister said in his reasons that there was “no evidence that … such an appeal, or pardon, is likely”. However, I do not take that comment to reflect a view on the petition’s prospects. Rather I take it as a reference to the lack of any evidence that the Executive had, for example, given an indication that a decision on the petition was imminent. If such evidence had existed, having regard to the provisions of s 501(10) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act), it may have been relevant to the reasonableness of a decision to proceed in the face of an indication of that kind. However, no such evidence was proffered in this matter and its absence, combined with the matters mentioned above, make the challenge to the Minister’s decision on this unreasonableness ground all the more unmeritorious.

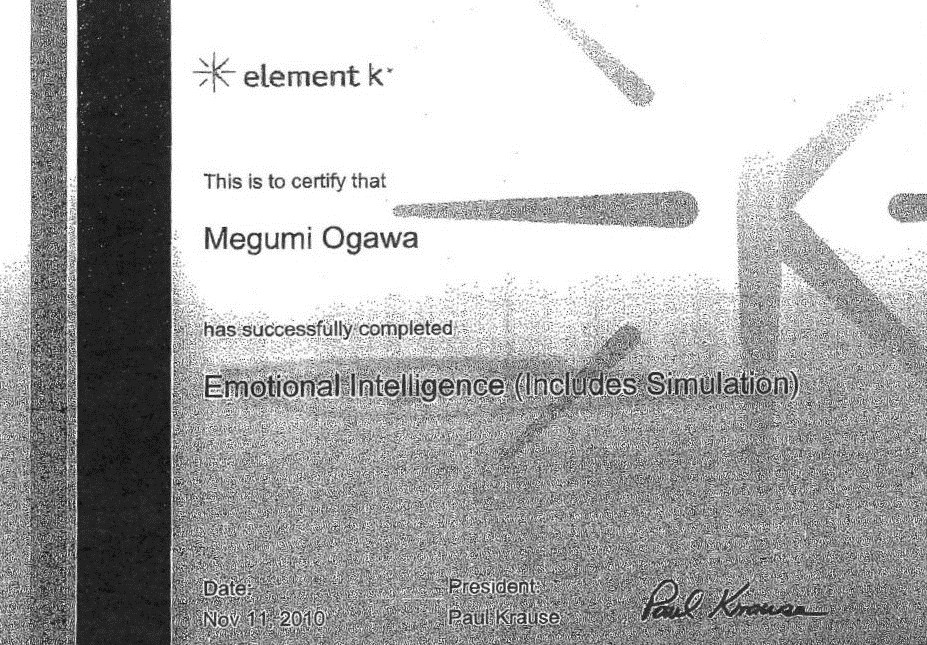

5 However, with the exceptions outlined below, I respectfully disagree with their Honours’ reasons and conclusions with respect to appeal ground 1. The exceptions are, first, that I agree with their Honours’ reasons and conclusions with respect to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate. On that aspect of appeal ground 1, their Honours have concluded that Dr Ogawa has not demonstrated that the Minister failed to have regard to the information in that Certificate or that, even if he did so fail, he did not commit a jurisdictional error because, even if that information were considered, it was not “material” in the sense that it would have denied Dr Ogawa the possibility of a successful outcome in her visa application. Accordingly, I respectfully agree with their Honours’ ultimate conclusion that the primary judge erred in concluding to the contrary.

6 Secondly, I agree with their Honours that the parties, and therefore the primary judge, appear to have dealt with the two pieces of information at the centre of appeal ground 1 – the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter – on the footing that they were submitted as additional information under s 55 of the Act. Specifically, that they “were furnished by Dr Ogawa to the Minister after she made the visa application but before the Minister made his decision” (see [36] of the primary judge’s reasons). However, I agree with the majority that this approach appears to ignore the contents of the letter from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection dated 2 February 2016 (sic 2017) quoted below (at [20]) which make it relatively clear that both pieces of information were submitted in response to the invitation contained in that letter. Furthermore, I agree with their Honours that, by its terms, that letter constituted an invitation which engaged the provisions of ss 56 and 58 of the Act.

7 Thirdly, and relatedly, I also agree with their Honours that this difference in approach does not affect the outcome of this aspect of this appeal. That is so because both of those sections are expressly confined to relevant information. Section 56(1) expressly refers to information that the Minister “considers relevant” (emphasis added). To similar effect, s 55(1) expressly refers to any “additional relevant information” (emphasis added). Furthermore, it is the Minister’s subjective opinion as to the relevance of the information that is determinative under both sections.

8 That brings me to my first area of disagreement with their Honours on appeal ground 1. It concerns Dr Mark Whittington’s letter. On that aspect of appeal ground 1, their Honours have concluded that the primary judge was correct in determining that the Minister failed to have regard to the information in that letter, that he thereby breached his obligations under s 56(1) of the Act, that the information contained in that letter was material in the sense described above and, accordingly, the Minister’s failure to consider that information constituted jurisdictional error.

9 The first two of these conclusions rely on their Honours’ construction of s 56 to the effect that the Minister is required to have regard to each piece of information that he gets in response to an invitation made under that section. For the reasons that follow, I do not, with respect, consider that the text, context and purpose of s 56 support that construction.

10 It is appropriate to begin with the text of s 56 and, in particular, the word “information”. The ordinary and natural meaning of that word is: “knowledge communicated or received concerning some fact or circumstance” (see Macquarie Dictionary (Macquarie Dictionary Publishers Pty Ltd, 6th ed, 2013); and see also VAF v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2004) 236 FCR 549; [2004] FCAFC 123 at [24] in the context of s 424A(1) and Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA (2019) 93 ALJR 252; [2019] HCA 3 (SZMTA) at [28]) in the context of Division 4). This meaning suggests that the material sought by, and submitted in response to, an invitation under s 56 (or as additional information under s 55) must communicate some knowledge with respect to a pertinent fact or circumstance.

11 Next, in considering the text of s 56, it is convenient to turn to the word “get”, or “gets”. The section provides that the Minister may “get any information that he or she considers relevant” (emphasis added) and, if the Minister “gets such information” (emphasis added), he or she “must have regard to that information in making the decision whether to grant or refuse the visa”. Thus, while the first usage of the word “get” operates prospectively, the second usage fixes the temporal point of reference as the point at which the Minister receives or obtains the information concerned. Next, it is notable how the word “information” is repeated and how those repetitions are interlinked in the text of s 56. Specifically, and in reverse order, the concluding words “that information” refer back to the words “such information” and those words, in turn, refer back to the words “any information that [the Minister] considers relevant”. Accordingly, when the section is read as a whole, I consider it requires the Minister to have regard to that information which he or she gets as a result of an invitation and which, once he or she obtains that information, he or she subjectively considers to be relevant. Conversely, neither the relevance of a piece of information, nor the obligation to have regard to it, is determined by the act of providing the information in response to the Minister’s invitation.

12 In my view, this construction is consistent with the context and purpose of s 56. As to context, it is to be noted that s 56 appears in Subdivision AB of Division 3 of Part 2 of the Act (ss 51A to 64) which is headed “Code of procedure for dealing fairly, efficiently and quickly with visa applications”. To that end, the first section of that Subdivision, s 51A(1), provides that: “This Subdivision is taken to be an exhaustive statement of the requirements of the natural justice hearing rule in relation to the matters it deals with”. Consistent with this provision, ss 54 and 55 respectively require the Minister (subject to the qualification mentioned above about relevance) to have regard to “all of the information in the application” as defined in s 54(2) and “any additional relevant information” the applicant gives to the Minister under s 55.

13 If the information falls into one of those categories, the Minister must have regard to it in the sense that he or she must engage in “an active intellectual process” directed to it (see Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 252 FCR 352; [2017] FCAFC 107 at [45] and Minister for Home Affairs v Buadromo (2018) 362 ALR 48; [2018] FCAFC 151 at [42]). If the Minister does not do so, he or she will have breached one or other of those sections and, if the information is “material” in the sense that there was “a realistic possibility that the [Minister’s] decision could have been different if [he] had taken [it] into account” (see SZMTA at [48]), the Minister will have committed a jurisdictional error in determining the visa application concerned.

14 Those provisions, and others in Subdivision AB, are self-evidently directed to providing fairness to visa applicants. However, s 56 is of a somewhat different character. It provides the Minister with a discretionary power to obtain information he or she wants bearing on a visa application. The Minister may obtain that information from the visa applicant, or from any person he or she wishes to. The latter being so, it is difficult to see why fairness to the visa applicant requires that, where the Minister exercises that discretionary power, he or she must have regard to all information obtained in response, however relevant or irrelevant it may be. Moreover, apart from not providing any additional element of fairness to a visa applicant, such an approach would be likely to significantly, and adversely, affect the efficiency and speed of the processes for dealing with visa applications.

15 In applying this construction to the facts and circumstances of this matter, there is, in my view, a number of things that need to be noted at the outset. First, in this appeal, this Court is required to conduct a real review of the primary judgment and to reach, and give effect to, its own conclusions on the issues of fact and law raised by it. In conducting that review, this Court is required to accord due weight to the advantages that the primary judge possessed, particularly where matters of credit are involved, or where the drawing of inferences is finely balanced (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Egg Corporation Ltd (2017) 254 FCR 311; [2017] FCAFC 152 at [126]–[132] (per Besanko, Foster and Yates JJ) and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 356 ALR 582; [2018] FCAFC 78 at [486]–[491] (per Greenwood, Middleton and Foster JJ)). However, in this case, the primary judge cannot be said to have possessed a particular advantage over this Court because his Honour did not hear any oral evidence and no issues of credit therefore arose. Further, because his Honour relied entirely on the same written record that is before this Court, the primary judge was in no better position to determine what inferences should be drawn from the primary facts evidenced by that record.

16 Secondly, Dr Ogawa bore the onus to establish, as a question of fact, that the Minister had committed jurisdictional error in making his decision with respect to her visa application (see Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZGUR (2011) 241 CLR 594; [2011] HCA 1 at [67] (per Gummow J with whom Heydon and Crennan JJ agreed at [91] and [92] respectively) and Plaintiff M64/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 258 CLR 173; [2015] HCA 50 at [24] per French CJ, Bell, Keane and Gordon JJ). With respect to this ground of appeal, that meant that Dr Ogawa had to establish that the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and/or Dr Whittington’s letter communicated knowledge that was relevant to a fact concerning her visa application and that the Minister did not have regard to that information when he made his decision regarding her application, thereby breaching s 56 (or s 55) of the Act.

17 Thirdly, and relatedly, to the extent that the discharge of that onus involved the drawing of an inference, where one or more competing inferences were available, Dr Ogawa must establish that the inference she advances “might reasonably be considered to have some greater degree of likelihood”. Conversely, she will fail to discharge that onus if the competing inferences are “of equal degree of probability” (see Holloway v McFeeters (1956) 94 CLR 470 at 480–481 (per Williams, Webb and Taylor JJ)).

18 Finally, even if Dr Ogawa establishes that the Minister committed a breach of s 56 with respect to Dr Whittington’s letter, to succeed in establishing that breach constituted jurisdictional error, she must also establish that the information concerned was material in the sense described above (see at [13]).

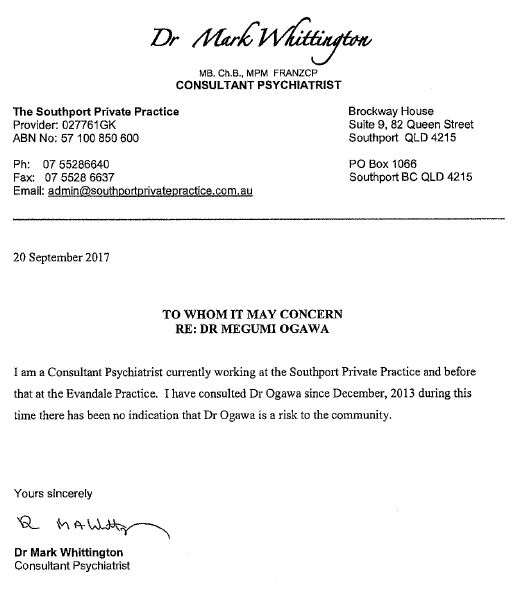

19 With these principles in mind, it is convenient to turn, finally, to Dr Whittington’s letter. As already mentioned above, that letter was submitted in response to an invitation contained in a letter dated 2 February 2016 (sic 2017) that was sent to Dr Ogawa on behalf of the Minister. The letter was headed “Notice of intention to consider refusal of your visa application under s501(1) of the Migration Act 1958”. Attached was a definition of the expression “character test” and a body of other materials. In a section of the letter entitled “Invitation to comment”, Dr Ogawa was invited to “provide information on whether [she passes] the character test, and on whether the decision-maker should exercise his or her discretion to refuse [her] application for a visa”. The letter went on to require Dr Ogawa to provide any such information in English and stated that her response may be sent by mail or email. It also set out details of the kind of information Dr Ogawa may provide, which included “letters of support from … family, friends, employer or others”.

20 In response, Dr Ogawa submitted a vast quantity of materials. The details of those materials were set out in the Minister’s written submissions on this appeal, the accuracy of which Dr Ogawa accepted in her written submissions. They disclose that, in the period from February 2017 to October 2017, approximately 800 pages of materials were submitted by, or on behalf of, Dr Ogawa. Consistent with the terms of the invitation above, they included “the submission and statements provided on her behalf by colleagues, friends and other members of the community” referred to at [33] of the Minister’s reasons. Dr Whittington’s letter, it is important to note, comprised one page of those materials. Furthermore, while those materials also included the “submission” mentioned in the Minister’s reasons above, that document did not specifically refer to, or rely upon, Dr Whittington’s letter, nor make any submissions about its importance in, or its relevance to, Dr Ogawa’s visa application.

21 Dr Whittington’s letter is reproduced in the reasons of the majority so it is unnecessary to set it out in these reasons. In essence, it communicated the following three items of knowledge to the Minister:

(a) as at 20 September 2017, Dr Whittington was “a Consultant Psychiatrist currently working at the Southport Private Practice” and previously “at the Evandale Practice”;

(b) he had “consulted Dr Ogawa since December, 2013”; and

(c) during this period “there [had] been no indication that Dr Ogawa [was] a risk to the community”.

22 Clearly, the salient piece of information communicated by that letter was that in item (c) above. The piece of information in item (b) above is, in my view, ambiguous. Taken literally, it means that Dr Whittington sought advice or counsel from Dr Ogawa when the context suggests the reverse, namely that Dr Ogawa consulted him. Assuming in Dr Ogawa’s favour that this was so, and having regard to item (a) above, the knowledge communicated by the letter can therefore be reduced to the statement that, from Dr Whittington’s consultations with Dr Ogawa as a Consultant Psychiatrist over a period of approximately three years and nine months, there was no indication that Dr Ogawa was a risk to the community.

23 There are a number of things to be noted about this statement. First, the barest details were provided of its factual foundation. That is to say, beyond identifying the period during which the consultations were undertaken, the letter did not provide any other details. Specifically, it did not disclose important facts such as: the number of times during which Dr Ogawa consulted Dr Whittington; the duration of those consultations; the observations he made about her behaviour during those consultations; the history he obtained from her; what treatment, if any, he provided to her; or his diagnosis of her mental condition and its prognosis. Secondly, it was devoid of any explanatory reasoning process which demonstrated how Dr Whittington had applied his expertise as a Consultant Psychiatrist to the facts disclosed to him about Dr Ogawa’s condition and state of mind to reach the conclusion that there was no indication that she was a risk to the community. Thirdly, the letter did not engage directly with the Minister’s invitation which sought information about the character test and the exercise of his discretion to refuse Dr Ogawa’s visa application. This lack of engagement was compounded, in my view, by the failure to illuminate the significance of Dr Whittington’s letter in the submission mentioned above. Fourthly, Dr Whittington did not illuminate the type of risk to which he was referring. To provide a non-exhaustive list, it may have been the physical risk to members of the community if Dr Ogawa were, in the future, to commit crimes of a similar kind to those she had committed in the past. Or it may have been the more general risk to the community associated with any future re-offending by Dr Ogawa. Or, if Dr Ogawa had some form of psychiatric condition for which she was receiving treatment from Dr Whittington, it may have been the risk to the community posed by that condition becoming psychotic.

24 It is common ground that there was no specific mention of Dr Whittington’s letter in the Minister’s reasons. At its highest, it may have fallen into the general reference in those reasons to “submission and statements” (see at [20] above). Apart from the Minister’s reasons, Dr Whittington’s letter was also not specifically mentioned in the departmental submissions provided to the Minister but, again, it may have fallen into the similar general reference described above. One of three inferences is therefore open. It may be inferred that the Minister considered the information in Dr Whittington’s letter and decided that it was not sufficiently relevant that he needed to have any regard to it. Or, it may be inferred that the Minister considered the letter and decided that it was sufficiently relevant but, after having had regard to it, he decided that it did not constitute a reason for refusing the application and, therefore, it did not warrant specific reference in his reasons. Or, it may be inferred that the Minister did not consider, and did not have regard to, the letter at all. For the reasons set out above, only the last of these three inferences will, in my view, avail Dr Ogawa in establishing a breach of s 56 (or s 55) of the Act.

25 Having regard to the matters discussed above and, in particular: the form of the invitation that was offered to Dr Ogawa, namely to submit information on the character test and the exercise of the Minister’s discretion to refuse her visa application; the circumstances in which Dr Whittington’s letter was provided to the Minister, namely as one page in a vast quantity of materials without any accompanying submission to identify its significance or relevance; and the content of the letter, namely as containing an assertion about risk without providing the details of its supporting factual basis, or its underlying reasoning process, I do not consider that inference has a greater degree of likelihood than the other two described above. It follows that I do not consider Dr Ogawa has discharged her onus to establish, as a fact, that the Minister committed a breach of either of s 56 (or s 55) of the Act.

26 Alternatively, even if it were to be assumed that the Minister had breached either of those provisions of the Act, having regard to the deficiencies in Dr Whittington’s letter as outlined above, I do not consider there is a realistic possibility that the Minister would have come to a different decision on Dr Ogawa’s visa application if he had considered that letter. Hence, I do not consider that that breach, if it occurred, constituted jurisdictional error.

27 For these reasons, it is my respectful view that the primary judge erred in concluding that the Minister breached the Act in not having regard to Dr Whittington’s letter or that, even if the Minister did commit such a breach, in concluding that that breach involved a jurisdictional error. Accordingly, I consider that the Minister has made out both aspects of ground of appeal 1. That being so, since the Minister has demonstrated error in the primary judgment with respect to each of his grounds of appeal, I consider his appeal must be upheld. It follows, in my view, that the orders on the appeal should be:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The orders of the Federal Court of Australia of 9 February 2018 be set aside.

3. The respondent’s further amended originating application to the Federal Court of Australia filed on 21 December 2017 be dismissed.

4. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of Federal Court proceeding QUD605/2017.

5. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.

I certify that the preceding twenty-five (25) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Reeves. |

Associate:

Dated: 19 June 2019

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

DAVIES, RANGIAH AND STEWARD JJ:

28 On 18 October 2017, the appellant (the Minister) made a decision under s 501(1) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act) refusing an application made by the respondent (Dr Ogawa) for a Partner (Temporary) (Class UK) Visa (Temporary Partner Visa).

29 On 9 February 2018, a single judge of this Court quashed the Minister’s decision. The Minister appeals against that judgment.

30 The primary judge held that the Minister failed to comply with his obligation under ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act to have regard to two items of information that had been provided by Dr Ogawa. His Honour also held that it was legally unreasonable for the Minister to refuse to defer his decision in circumstances where Dr Ogawa had petitioned the Governor-General for a pardon and a decision had not yet been made upon that petition. The Minister submits that his Honour erred in both aspects of the judgment.

31 We will proceed by describing the relevant legislative provisions, the Minister’s decision and the judgment of the primary judge before considering the parties’ submissions.

The legislation

32 Section 47(1) of the Act provides that the Minister is to consider a valid application for a visa.

33 Section 65(1) of the Act provides, relevantly, that after considering a valid application, the Minister, if satisfied that the grant of the visa is not prevented by s 501, is to grant the visa, or, if not so satisfied, is to refuse to grant the visa.

34 Section 501 of the Act provides, relevantly:

501 Refusal or cancellation of visa on character grounds

Decision of Minister or delegate—natural justice applies

(1) The Minister may refuse to grant a visa to a person if the person does not satisfy the Minister that the person passes the character test.

Note: Character test is defined by subsection (6).

…

Character test

(6) For the purposes of this section, a person does not pass the character test if:

(a) the person has a substantial criminal record (as defined by subsection (7)); or

…

Otherwise, the person passes the character test.

Substantial criminal record

(7) For the purposes of the character test, a person has a substantial criminal record if:

…

(d) the person has been sentenced to 2 or more terms of imprisonment, where the total of those terms is 12 months or more; or

…

Concurrent sentences

(7A) For the purposes of the character test, if a person has been sentenced to 2 or more terms of imprisonment to be served concurrently (whether in whole or in part), the whole of each term is to be counted in working out the total of the terms.

…

Pardons etc.

(10) For the purposes of the character test, a sentence imposed on a person, or the conviction of a person for an offence, is to be disregarded if:

(a) the conviction concerned has been quashed or otherwise nullified; or

(b) both:

(i) the person has been pardoned in relation to the conviction concerned; and

(ii) the effect of that pardon is that the person is taken never to have been convicted of the offence.

35 Section 501G of the Act provides, relevantly:

(1) If a decision is made under subsection 501(1)…to:

(a) refuse to grant a visa to a person; or

…

the Minister must give the person a written notice that:

(c) sets out the decision; and

(d) specifies the provision under which the decision was made and sets out the effect of that provision; and

(e) sets out the reasons (other than non-disclosable information) for the decision; and

…

(4) A failure to comply with this section in relation to a decision does not affect the validity of the decision.

The Minister’s decision

36 Dr Ogawa is a citizen of Japan who arrived in Australia on 24 November 1999. On 27 March 2009, she was convicted in the District Court of Queensland of two counts of using a carriage service to harass in contravention of s 474.17 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), and two counts of using a carriage service to make a threat to kill in contravention of s 474.15. The two counts under s 474.17 involved Dr Ogawa sending 83 emails on 13 and 14 April 2006 to various email addresses at the Federal Court of Australia and making 176 telephone calls to Registries and Chambers of the Court between 13 April and 19 May 2006. The two counts under s 474.15 involved Dr Ogawa making threats to kill an officer of the Court and two Registrars of the Court.

37 Dr Ogawa was sentenced to concurrent terms of six months’ imprisonment on each count. She was also convicted of contempt of court and sentenced to four months’ imprisonment. As a result of her convictions, she does not pass the character test as defined in ss 501(6), (7) and (7A) of the Act. That was a matter that Dr Ogawa disputed before the Minister, but not before the Court.

38 On 12 April 2013, Dr Ogawa made a combined application for a Temporary Partner Visa and a Partner (Residence) (Class BS) Visa.

39 On 2 February 2017, in a letter wrongly dated 2 February 2016, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (the Department) provided Dr Ogawa with a notice informing her that the Minister or his delegate intended to consider whether there were grounds under s 501(1) of the Act to refuse to grant her a Temporary Partner Visa. The notice invited Dr Ogawa to “comment or provide information on whether you pass the character test, and on whether the decision-maker should exercise his or her discretion to refuse your application for a visa.”

40 Between 20 February and 1 October 2017, Dr Ogawa provided the Department with submissions and a mass of supporting documents. The documents included certificates demonstrating courses she had completed, documents said to demonstrate community participation, letters of support, academic articles, reports and various other documents.

41 Among the documents Dr Ogawa provided to the Department was a certificate stating that she had successfully completed an “Emotional Intelligence (Includes Simulation)” course with an organisation called “element k” (the Emotional Intelligence Certificate). She also provided a report or letter from Dr Mark Whittington, a psychiatrist, dated 20 September 2017, who reported that he had consulted Dr Ogawa since December 2013 and expressed the opinion that during that time there had been no indication that she was a risk to the community (Dr Whittington’s letter).

42 Dr Ogawa also provided to the Department a copy of a petition sent to the incoming Governor-General in 2014 and an earlier petition sent to the previous Governor-General in 2013 seeking a pardon or, alternatively, a referral of her case by the Commonwealth Attorney-General to the Queensland Court of Appeal pursuant to s 672A of the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld). The later petition superseded the earlier one.

43 In a submission to the Minister dated 8 April 2017, Dr Ogawa said, referring to the 2014 petition:

In any event, in light of s 501(10) of the Migration Act 1958, it is premature to decide that the Visa Applicant does not pass the character test prior to the final disposition of the petition submitted by the Visa Applicant.

44 At the time of the Minister’s decision, no decision had been made upon the 2014 petition.

45 On 10 October 2017, the Department provided a submission to the Minister asking him to consider Dr Ogawa’s application for a Temporary Partner Visa. The submission was accompanied by a draft statement of reasons for decision and a number of documents, including the documents that had been provided by Dr Ogawa to the Department.

46 On 18 October 2017, the Minister made the following decision:

I have considered all relevant matters including an assessment of the character test as defined by s 501(6) of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act), and all information before me provided by or on behalf of Dr Megumi OGAWA in connection with the possible refusal of her application for a Partner (Temporary) (Class UK) visa.

…

Dr Ogawa has not satisfied me that she passes the character test. I have decided to exercise my discretion under s 501(1) of the Act to refuse Dr OGAWA’S visa. I hereby refuse Dr OGAWA’s application for a Partner (Temporary) (Class UK) visa. My reasons for this decision are set out in the attached Statement of Reasons.

47 The Minister’s statement of reasons began by considering the character test under s 501(6) of the Act. The Minister noted Dr Ogawa’s contention that she passed the character test, but rejected that submission, finding that she had a substantial criminal record and that she did not pass the character test. The Minister also said at para 10:

While I acknowledge that a Petition for pardon was made to the Governor-General of Australia in 2014, at present there is no evidence that there is an appeal of Dr Ogawa’s convictions underway or that such an appeal, or pardon is likely.

48 The Minister then turned to consider the exercise of his discretion under s 501(1) of the Act. The Minister considered various matters under the headings “Protecting the Australian Community”, “Criminal conduct”, “Risk to the Australian Community”, “Expectations of the Australian community”, and “Other Considerations”. For the purposes of this appeal, it is only necessary to describe the Minister’s discussion under the heading “Risk to the Australian Community”. The Minister said, relevantly:

22. In making my decision I considered that Australia has a low tolerance of any criminal or other serious conduct by visa applicants or those holding a limited stay visa, reflecting that there should be no expectation that such people should be allowed to come to, or remain permanently in, Australia.

23. I have taken into consideration that Dr OGAWA has applied for a Partner (Temporary) (Class UK) visa, for the purposes remaining in Australia with her partner and also for continuing employment. I have considered the risk of harm to the Australian community in the context of the permanent stay period and specific purposes of the visa application.

24. I have considered whether Dr OGAWA poses a risk to the Australian community through re-offending by having regard to any mitigating or causal factors in her offending, and giving consideration to the steps Dr OGAWA has undertaken to reform and address her behaviour. I have also taken into account Dr OGAWA’s overall conduct and her insight into the offending.

25. I have taken into consideration Dr OGAWA’s comments regarding the circumstances of her offending an I acknowledge that Dr OGAWA was frustrated with the justice system in general and in particular how her case against the University of Melbourne was being handled by the courts. I acknowledge Dr OGAWA’s view that the convictions recorded against her constitute a miscarriage of justice and that she has filed a petition to the Commonwealth Attorney-General for her case to be referred back to the Queensland Court of Appeals.

26. I accept that Dr OGAWA was experiencing frustration and stress, however, I do not accept that frustration or emotional stress justifies criminal conduct. I note Dr OGAWA has made no submissions in relation to her ability to manage future difficult situations, such as completion of courses in anger management.

27. I note that in sentencing Dr OGAWA, the court took into account her mental state at the time and that Judge Durward acknowledged that Dr OGAWA may have been suffering from a personality disorder but that her mental function was not compromised to an extent in which she was unable to participate in her trial. Furthermore, Dr OGAWA has not presented any evidence to indicate that she was mentally impaired at the time of her offending nor has her mental state been identified as a causal factor in her offending.

…

33. I accept Dr OGAWA has an otherwise unblemished criminal record and that she is well regarded in her field both professionally and personally. I have had regard to the submission and statements provided on her behalf by colleagues, friends and other members of the community, including prominent and well respected members of the Australian community.

…

35. Nevertheless, I accept that Dr OGAWA has remained conviction free for some 11 years and that her behaviour in the community since her release from prison has been disciplined.

36. In light of Dr OGAWA’s ongoing minimisation of the impact of her offending, unwillingness to accept the reality of her conduct and established difficulty in managing stressful situations„ I find that Dr OGAWA remains an ongoing risk of reoffending, albeit it low in light of her subsequent lawful conduct. If Dr OGAWA did engage in further criminal conduct of a similar nature, it could result in significant psychological harm, or fear of physical harm, to a member of the Australian community.

37. In relation to her conviction for contempt, Judge Durward noted that Dr OGAWA’s counsel tended (sic) an apology to the Court. I note too that Judge Durward rejected her apology, finding it not to be genuine after having provided Dr OGAWA with multiple opportunities to desist from her behaviour. Should Dr OGAWA again behave in a manner that caused her to be convicted of contempt there is a risk that this behaviour would pose a "real risk of undermining public confidence in the administration of justice" as noted by Judge Durward.

(Underlining added. Errors in original.)

49 The Minister concluded:

45. I considered all relevant matters including (1) an assessment against the character test as defined by s. 501(6) of the Act and (2) all other evidence available to me, including information provided by, or on behalf of Dr OGAWA.

46. Dr OGAWA has committed a serious crime, namely making threats to kill. I find that her offending involved implied violence and that her actions caused both emotional and physical distress to her victims. I find that members of the Australian community could be exposed to further emotional harm should Dr OGAWA reoffend in a similar manner. I could not rule out the possibility of further offending by Dr OGAWA and in my view, the Australian community should not tolerate any further risk of harm.

47. In reaching my decision I concluded that Dr OGAWA represents an unacceptable risk of harm to the Australian community and that the protection of the Australian community outweighed any countervailing considerations above.

48. Having given full consideration to all of these matters, I decided to exercise my discretion to refuse to grant Dr OGAWA’s application for a Partner (Temporary) (Class UK) visa under s. 501(1) of the Act.

(Underlining added.)

50 It may be observed that the Minister did not expressly refer to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate or to Dr Whittington’s letter in his statement of reasons.

The judgment of the primary judge

51 Dr Ogawa applied to this Court for review of the Minister’s decision pursuant to s 476A(1)(c) of the Act.

52 Dr Ogawa represented herself in the hearing before the primary judge. She relied upon six grounds. The primary judge upheld the second and fifth grounds. It is unnecessary to discuss his Honour’s reasons for rejecting the remaining grounds.

53 The second ground was that the Minister failed to accord Dr Ogawa procedural fairness when considering “Risk to the Australian Community”. Dr Ogawa submitted that the Minister had failed to consider two items of information she had given to the Minister, namely the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter. Dr Ogawa argued that the Minister’s failure to have regard to that information was contrary to the requirements of ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act.

54 The primary judge observed that the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter had been furnished to the Minister after she made her visa application but before the Minister made his decision. His Honour held that, accordingly, ss 54 and 55 of the Act were applicable to each of these two items of information. His Honour considered that each item of information was relevant to the Minister’s consideration of any risk that Dr Ogawa would reoffend.

55 The primary judge then said that although the Minister had expressly chosen to consider the subject of risk in the exercise of his discretion, something further should be said about that subject. His Honour discussed the judgment of the Full Court in Moana v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 230 FCR 367, where Rangiah J held at [66] (North J agreeing) that in the exercise of the discretion under s 501(2) of the Act, the Minister is required to consider whether there is a risk of harm to the Australian community posed by the continued presence of the visa holder in Australia and to take into account any such risk. The primary judge observed that in subsequent judgments of the Full Court, reference had been made to an “unresolved tension” between the majority judgment in Moana and observations made by Kiefel and Bennett JJ in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v Huynh (2004) 139 FCR 505 at [72] and [74]. His Honour expressed a preference for the views expressed by the majority in Moana.

56 The primary judge then returned to consideration of ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act. His Honour observed that those provisions oblige the Minister to “have regard to” information given by a visa applicant. However, his Honour said that the decision would only be invalid if the Minister failed to have regard to relevant information.

57 The primary judge then considered whether the Minister had failed to have regard to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter. The Minister had stated that he had considered “information provided by, or on behalf of Dr Ogawa”, but his Honour said that this was not conclusive. His Honour noted that neither of the two items had been expressly referred to in the Minister’s statement of reasons. His Honour then referred to aspects of the Minister’s reasons which tended in favour of a conclusion that the Minister had failed to consider either piece of information.

58 The Minister had stated at para 26 of his reasons that, “I note Dr Ogawa has made no submissions in relation to her ability to manage future difficult situations, such as completion of courses in anger management.” His Honour observed, however, that Dr Ogawa had provided the Emotional Intelligence Certificate, as well as a certificate demonstrating completion of a subject called “Managing Conflict (includes Simulation)” (the Managing Conflict Certificate). His Honour noted that the precise content of each subject was not identified in the certificates. However, his Honour reasoned that any finding by the Minister that the certificates were not relevant to Dr Ogawa’s “ability to handle future difficult situations”, required express identification and consideration. His Honour considered that by necessary inference, flowing from the absence of an explicit reference to the certificates, and reading the reasons as a whole, the Minister did not have regard to the certificates.

59 The primary judge observed that there was no express reference in the Minster’s reasons to Dr Whittington’s letter. The Minister had stated at para 33 that, “I have had regard to the submission and statements provided on behalf of colleagues, friends and other members of the community, including prominent and well respected members of the Australian community.” His Honour said that the content of Dr Whittington’s letter of 20 September 2017 was “not just a statement by a member of the community”, but a considered opinion by a specialist in a pertinent discipline in respect of the very consideration which the Minister properly regarded as relevant. His Honour found that the likely inference was that the Minister did not have regard to the information in Dr Whittington’s letter.

60 The primary judge reached the conclusion that the Minister had not had regard to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate or Dr Whittington’s letter by considering, in conjunction with the failure to refer to either of them, the failure to refer to the Managing Conflict Certificate, and by reading the reasons as a whole, including the error made at para 26 of those reasons.

61 The primary judge found that the requirement in ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act to have regard to the information provided by Dr Ogawa was breached by the Minister. His Honour found that the information that was not considered was relevant and might have made a difference to the outcome of the visa application. His Honour held that, accordingly, the Minister’s decision should be quashed.

62 Dr Ogawa’s fifth ground was that the Minister’s decision was legally unreasonable. One basis of that ground was that it was unreasonable for the Minister to proceed to determine the visa application when the petition to the Governor-General for a pardon was pending.

63 The primary judge observed that Dr Ogawa had made a submission to the Minister that, in light of s 501(10), it was premature to decide that she did not pass the character test pending the final disposition of the 2014 petition.

64 The primary judge considered that Dr Ogawa’s current petition was detailed and forensically sophisticated and not a bare request for a pardon or an Attorney-General’s reference. His Honour considered that the petition contains a “scholarly rationale for why it is submitted that the Criminal Code offence convictions should be quashed”. His Honour found that “the petitions themselves therefore contain evidence by reference to which a likelihood that they might receive favourable consideration, if only to the extent of persuading the Commonwealth Attorney-General that there ought to be a reference, might be measured”.

65 The primary judge accepted that the Minister had considered at para 10 of his statement of reasons, the possibility of deferring his decision because of the pendency of the petition but determined not to do so for the reasons set out in that paragraph. His Honour said that the difficulty about the reasons was that they did not engage at all with the contents of the 2014 petition, in circumstances where that petition contained evidence by reference to which the likelihood of success might be measured. His Honour considered that the reasons did not disclose any analysis of the submissions made in the petition which would warrant any conclusion as to the likelihood that either a reference would be made at all or, that by the outcome of an appeal or a pardon, the offences might have to be disregarded.

66 If the offences were quashed on appeal following a reference by the Attorney-General, or the subject of a pardon, the effect of s 501(10) of the Act would be that the sentence in respect of those offences would have to be disregarded, with the result that Dr Ogawa would not have a “substantial criminal record”. His Honour considered that the refusal to defer the decision was unreasonable in outcome and that, further, because it entailed an unreasonable refusal of the deferral request, the decision was unreasonable or plainly unjust.

67 For these reasons, the primary judge upheld the application for review and quashed the Minister’s decision.

The notice of appeal

68 The notice of appeal to this Court relies upon the following grounds:

1. The [primary judge] erred in finding (Judgment at [60]) that in the Minister’s decision dated 18 October 2017, to refuse the Applicant visa pursuant to s501(1) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Decision), breached the requirements of ss54 and 55 of the Act in exercising his discretion under s501 (1) of the Act, as:

(a) An assessment of risk to the Australian community, is not a mandatory relevant consideration, but merely a permissive consideration, the consideration of which does not result in invalidity of the Decision;

(b) The two items of information alleged to have not been considered (being a certificate of completion of a course "Emotional Intelligence" and a letter from Dr Whittington) were matters "personal to the visa holder" and therefore not mandatory relevant considerations on the exercise of the discretion under s501 (1) of the Act;

(c) In any event, on a proper interpretation of the Minister’s reasons for his decision, he did take into account the two items of information.

2. The [primary judge] erred in finding (Judgment at [100]) that the Minister’s decision to refuse the deferral request was legally unreasonable, in circumstances where:

(a) his Honour erroneously considered that the Minister had not engaged with the contents of the petition, which was the basis for the deferral request;

(b) his Honour erred in the standard of reasonableness applied to the Minister’s decision, in the following circumstances:

(i) this was a decision exercising the unfettered discretion under s501 of the Act;

(ii) the matter the basis of the deferral request was a Petition to the Governor General for a pardon of her convictions which had been in 2013 to the previous Governor General and updated to the current Governor General in 2014;

(iii) any consideration of a deferral request must carry with it a temporal consideration of the time sought by the deferral request. It is not a requirement of unreasonableness for the decision-maker to await the outcome of a relevant process for an unspecified and unidentifiable time frame.

The submissions

69 The Minister submits that the primary judge’s reasoning for quashing the decision relied upon the proposition that the risk to the Australian community is a mandatory relevant consideration under s 501(1) of the Act and, as such, the Minister’s failure to take into account the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter was a failure to act in accordance with ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act.

70 The Minister submits that risk to the Australian community is not a mandatory relevant consideration. He submits that the “unresolved tension” between Moana at [66] and Huynh at [72] and [74] should be resolved in favour of the view taken in Huynh.

71 The Minister submits that even if the risk to the Australian community is a mandatory relevant consideration, Moana and other authorities establish that the Minister has no duty to evaluate that risk in any particular way or to quantify that risk. The Minister submits that his Honour erred by requiring the Minister to quantify the risk of harm to the Australian community and to do so by reference to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter. His Honour also erred by assuming that Moana necessarily requires that all information on the subject of risk be considered as a mandatory relevant consideration. Further, his Honour’s approach is said to be inconsistent with the acceptance in Moana that the Minister is not required to take into account factors personal to the visa holder when considering the risk of harm.

72 The Minister submits that while the Minister did consider the risk of harm to the Australian community, that does not transform the question of risk, nor any document going to risk, into a mandatory relevant consideration.

73 The Minister also submits that his Honour erred by finding that the Minister’s statement that, “Dr Ogawa has made no submissions in relation to her ability to manage difficult situations, such as completion of courses in anger management” contained error. The Minister submits that “properly understood and beneficially construed”, the Minister made no such error because, firstly, no submissions to that effect had been made, and, secondly, there was no basis to infer that the Minister did not consider the Emotional Intelligence Certificate.

74 The Minister also submits that there is no basis to infer that the Minister did not have regard to Dr Whittington’s letter. The Minister stated in his reasons that he had regard to the submissions and “statements provided on her behalf by colleagues, friends and other members of the community”. The Minister submits that this shows that he did have regard to Dr Whittington’s letter.

75 The Minister submits that s 54(1) and s 55(1) do not require him to have regard to every piece of information, but only information which is relevant. Further, the Minister submits that his obligation is analogous to that described in Minister for Home Affairs v Buadromo (2018) 362 ALR 48; [2018] FCAFC 151 at [41], namely to engage with the submitted material as a whole, rather than to have regard to each individual piece of information submitted.

76 The Minister also submits that the primary judge erred in finding that the Minister’s decision was legally unreasonable. The Minister concluded at para [10] of his reasons that there was no evidence that a pardon was likely, and submits that was a finding which it was open to make. Further, his Honour is said to have erroneously considered whether or not deferral should have been granted, rather than whether or not in making the decision, the Minister went beyond the bounds of the discretion conferred by s 501(1) of the Act.

77 The Minister submits that the primary judge failed to have regard to the particular statutory context of s 501(1) of the Act, and to the broad unfettered nature of the discretion conferred by that provision. In particular, s 55(2) provides that the Minister is not required to delay making a decision because the applicant might give further information. The Minister also relies upon ss 54(3), 63(1) and 51A. The Minister submits that these provisions reinforce that the statutory context is inconsistent with his Honour’s construction of s 501(1), which narrows the ambit of permissible decision-making.

78 The Minister submits that although the primary judge accepted that if the convictions were quashed or a pardon granted with the effect described under s 501(10)(b) of the Act the respondent could reapply for a Temporary Partner Visa, his Honour failed to have regard to that matter.

79 The Minister submits that there was no unreasonableness in the Minister making his decision without awaiting the outcome of the petition. The Minister was entitled to consider that it was preferable to reach a decision under s 501(1) of the Act without awaiting the outcome of the petition.

80 Dr Ogawa submits, essentially, that the primary judge was correct for the reasons given by his Honour.

81 In addition, Dr Ogawa submits that an obligation arose under s 56(1) of the Act for the Minister to consider all the information she provided at the Minister’s invitation. Further, she submits that the relevance of information under ss 54(1) and 55(1) must be tested objectively, and not by reference to the Minister’s subjective view of its relevance. Dr Ogawa submits that, on either basis, the Minister was required to have regard to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter, but failed to do so.

Consideration

82 The decision to refuse Dr Ogawa the grant of a Temporary Partner Visa was made personally by the Minister under s 501(1) of the Act. The application for review of that decision was made under s 476A(1)(c) of the Act. It was necessary for Dr Ogawa to demonstrate jurisdictional error on the part of the Minister: cf Plaintiff S157/2002 v The Commonwealth of Australia (2003) 211 CLR 476 at [76].

83 The primary judge held that the Minister had committed jurisdictional error in two respects. The first was failing to comply with the requirements of ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act to have regard to the information contained in two documents Dr Ogawa gave to the Minister. The second was that the Minister’s refusal to defer consideration of the visa application pending a decision upon the petition to the Governor-General was “unreasonable in outcome” and “plainly unjust”.

84 The notice of appeal alleges that his Honour erred in holding that there was jurisdictional error on each of these bases. We will consider each ground of the notice of appeal in turn.

Whether the primary judge erred in finding that the Minister breached the requirements of ss 54(1) and 55(1) of the Act

85 The first ground of the notice of appeal, as expressed and argued, is premised upon the proposition that the primary judge’s decision relied upon risk to the Australian community being a mandatory relevant consideration in the exercise of the Minister’s discretion under s 501(1) of the Act. However, it is plain from his Honour’s reasons that this premise is not established. While his Honour expressed a view in obiter dicta that risk to the Australian community is a mandatory relevant consideration, that view had no influence on the outcome of the case. His Honour observed that the Minister had taken into account risk to the Australian community by finding that Dr Ogawa posed such a risk. His Honour’s reasoning was that the Minister failed to have regard to the information in the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter, and as that information was relevant to whether there was such a risk, the Minister had failed to comply with ss 54(1) and 55(1).

86 It follows that it is unnecessary to consider the Minister’s submission that there is “unresolved tension” between Moana and Huynh, and that Huynh should be preferred. We merely observe that in Le v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 237 FCR 156 at [51], Rangiah J sought to demonstrate why there is no such tension.

87 Part 2 of the Act has the heading, “Arrival, Presence and Departure of Persons”. Subdivision AB of Division 3 of Pt 2 is headed, “Code of Procedure for Dealing Fairly, Efficiently and Quickly with Visa Applications”, and consists of ss 51A–64.

88 Section 51A(1) of the Act states that:

This Subdivision is taken to be an exhaustive statement of the natural justice hearing rule in relation to the matters it deals with.

89 Accordingly, ss 54, 55, 56 and 57 of the Act each contain a part of the natural justice hearing rule in relation to an application for a visa. Section 54 provides, relevantly:

54 Minister must have regard to all information in application

(1) The Minister must, in deciding whether to grant or refuse to grant a visa, have regard to all of the information in the application.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), information is in an application if the information is:

(a) set out in the application; or

(b) in a document attached to the application when it is made; or

(c) given under section 55.

…

90 Section 55 of the Act provides:

55 Further information may be given

(1) Until the Minister has made a decision whether to grant or refuse to grant a visa, the applicant may give the Minister any additional relevant information and the Minister must have regard to that information in making the decision.

(2) Subsection (1) does not mean that the Minister is required to delay making a decision because the applicant might give, or has told the Minister that the applicant intends to give, further information.

91 Section 56 of the Act provides:

56 Further information may be sought

(1) In considering an application for a visa, the Minister may, if he or she wants to, get any information that he or she considers relevant but, if the Minister gets such information, the Minister must have regard to that information in making the decision whether to grant or refuse the visa.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), the Minister may invite, orally or in writing, the applicant for a visa to give additional information in a specified way.

92 It is unnecessary to discuss the other provisions of Subdivision AB, except to observe that in Plaintiff M174/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2018) 353 ALR 600; [2018] HCA 16, it was held at [11]–[12] that compliance with s 57(2) of the Act is (despite s 69) a condition of the valid performance of the Minister’s duty under s 65(1) to consider a valid application.

93 Although the parties referred only to ss 54 and 55 of the Act in the proceedings before the primary judge, s 56 is also relevant. That is because the letter of 2 February 2017 written on behalf of the Minister invited Dr Ogawa to, “provide information on whether you pass the character test, and on whether the decision-maker should exercise his or her discretion to refuse your application for a visa.” The letter required Dr Ogawa to provide any such information in English and by mail or email. The letter was an invitation by the Minister for Dr Ogawa “to give additional information in a specified way” within s 56(2). The material subsequently provided by Dr Ogawa was given in response to that invitation.

94 In Win v Minister for Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2001) 105 FCR 212, the Full Court, considering s 424(1) of the Act, a provision dealing with the review tribunal’s powers and cast in similar terms to s 56(1), held at [19]-[23] that “information” can include “untested assertions made by an informant”. In our view, the content of the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter fall within this description.

95 Section 56(1) of the Act provides that when the Minister gets information, he or she “must have regard to that information” in making the decision whether to grant or refuse the visa. The similar language of s 54(1) was described by Weinberg J in A v Pelekanakis (1999) 91 FCR 70 at [45] as plainly giving rise to a “duty” that is “mandatory”. The requirement in s 424(1) to “have regard to” information was described in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZKTI (2009) 238 CLR 489 at [36] as a “limitation” upon the power to get information that the review tribunal considers relevant. In our opinion, the imperative language of s 56(1), together with its role as part of the statutory natural justice hearing rule, indicates that compliance with the provision is a necessary pre-condition for the valid performance of the Minister’s duty under s 65(1): cf SAAP v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2005) 228 CLR 294 at [68], [136], [173], [208]; Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2018) 359 ALR 1; [2018] HCA 34 at [23]–[24].

96 Since s 56(1) of the Act applies, it is unnecessary to consider whether the Minister has any additional obligation to consider the information provided by Dr Ogawa under ss 54(1) and 55(1). While the parties agreed that any obligation under ss 54(1) and 55(1) is limited to having regard to relevant information, there was argument as to whether relevance is to be determined subjectively by the Minister, or objectively by the Court reviewing a decision of the Minister. That issue does not arise under s 56(1), which is expressed in quite different terms. Under that provision, the Minister may get any information “that he or she considers relevant”. The Minister, by getting information, has necessarily considered the information to be relevant. It is the Minister’s opinion of relevance, not the Court’s opinion, that determines whether the Minister has an obligation under s 56(1) to have regard to the information provided in response to the invitation.

97 However, the Court will be required to consider the objective relevance or materiality of the information when deciding whether any failure to comply with that obligation amounts to jurisdictional error: cf Hossain at [30], [72].

98 It may also be observed that the Minister’s consideration that the information he or she proposes to get pursuant to s 56(1) is relevant is made in advance and independently of the Minister’s decision upon the application for the visa under s 65(1): cf Plaintiff M174/2016 at [9]. Until it is obtained and considered, the Minister cannot know whether the information will ultimately prove to be relevant to the decision: cf Win at [19]. It follows that the Minister, after having regard to the information, might find it to be irrelevant and disregard it when making the decision.

99 The Minister submits that s 56(1) of the Act does not require the Minister to have regard to every piece of “information” provided by the visa applicant in response to an invitation, but only to the submitted material as a whole. The Minister relies on Buadromo. That case was concerned with s 501CA(3) of the Act, a provision dealing with revocation of a visa cancellation, which requires the Minister to “invite the person to make representations” and, implicitly, to take into account the representations made. The Full Court held at [41] that s 501CA(3) requires the Minister to consider the representations as a whole, but does not require the Minister to consider the individual statements contained in the representations. However, the language of s 56(1) of the Act is different. It deals only with “information”. A “representation” under s 501CA(3) is a broader term than “information”. Section 501CA(3) itself distinguishes between “representations” and “information”. In our opinion, the passage relied upon by the Minister at [41] of Buadromo has no application to the Minister’s specific obligation under s 56(1) to have regard to “information”.

100 Section 56(1) allows the Minister to “get any information that he or she considers relevant” but, requires that, if the Minister gets such information, he or she “must have regard to that information” (emphasis added). In our opinion, the language of s 56(1) makes it clear that the Minister is required to have regard to all of the information the Minister gets, including information that is provided in response to an invitation to the visa applicant. The purpose of the requirement is evidently to ensure that the Minister does not merely discard the information he or she gets without first having regard to the significance or otherwise of that information.

101 What is the Minister required to do in order to comply with his obligation to “have regard to” information under s 56(1) of the Act? In Singh v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural Affairs (2001) 109 FCR 152, Sackville J held that s 54(1) requires application of “an active intellectual process” directed at the information. That view was approved in NAJT v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs (2005) 147 FCR 51 at [46], [212]; see also Tickner v Chapman (1995) 57 FCR 451 at 462, 476 and 495; Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 252 FCR 352 at [45]. That requirement may be regarded as part of an obligation imported by the use of expressions such as “consider” and “have regard to” to give proper, genuine and realistic consideration to the relevant matters: see Bondelmonte v Bondelmonte (2016) 259 CLR 662 at [43]; cf. Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Maioha [2018] FCAFC 216 at [42].

102 The Minister’s obligation to have regard to information under s 56(1) of the Act requires the Minister to engage in an active intellectual process directed at the information. In other words, the decision-maker must actively think about the information: He v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 255 FCR 41 at [52].

103 There is a distinction between the making of a decision by the Minister and the written notice given under s 501G(1) of the Act setting out his or her reasons: cf Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Yusuf (2001) 206 CLR 323 at [30]; Semunigus v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [1999] FCA 422 at [19], approved in Semunigus v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2000) 96 FCR 533 at [11], [55], [101]; Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZQOY (2012) 206 FCR 25 at [40]. The distinction is that the making of a decision involves a mental process, while the reasons provide evidence of the mental process engaged in by the decision-maker: He at [79]. It is not necessary for reasons to refer to every piece of evidence advanced, as, for example, some evidence may be irrelevant, or its consideration may be subsumed into findings of greater generality: Applicant WAEE v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2003) 236 FCR 593 at [46]–[47]. It may also be observed that the Minister’s obligation under s 501G(1) is limited to setting out findings on those questions of fact which he or she subjectively considers to be material: cf Yusuf at [68]. However, where the reasons do not expressly refer to an issue, an inference may, but will not necessarily, be drawn that the issue was not adverted to as part of the decision-maker’s mental process: Applicant WAEE at [47]. In Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Sabharwal [2018] FCAFC 160, the Full Court said at [76]:

76 The written reasons of the Minister may, and generally will, be taken to be a statement of those matters considered and taken into account. If something is not mentioned it may be inferred that is not been considered or taken into account. Whether it is appropriate to draw such an inference must be considered by reference to the facts of each particular case and the Minister’s reasons as a whole. The reasons must be construed in a practical and common-sense manner and not with an eye keenly attuned to the perception of error.

(Citations omitted.)

104 That leads to the question of whether the Minister did or did not have regard to the Emotional Intelligence Certificate and Dr Whittington’s letter. The answer falls to be determined primarily from the statement of reasons.

Dr Whittington’s letter

105 It is convenient to begin with Dr Whittington’s letter. That letter is as follows:

106 The Minister’s statement of reasons does not expressly mention Dr Whittington’s letter. However, the Minister submits that he should be understood as having referred to that letter when he said at para 33:

I have had regard to the submission and statements provided on her behalf by colleagues, friends and other members of the community, including prominent and well respected members of the Australian community.

107 Dr Whittington was Dr Ogawa’s consulting psychiatrist. He cannot be described as a “colleague” or a “friend” of Dr Ogawa. His letter was not a “submission”. Therefore, on the Minister’s argument, Dr Whittington and his letter would have to fall within the description of “statements provided on her behalf by …other members of the community”.

108 There are only two possible inferences. Either, the Minister had regard to Dr Whittington’s letter, or the Minister overlooked that letter. The issue is which inference is to be preferred.

109 The Minister’s submission requires the passage at para 33 of his reasons to be read literally. On a literal construction, Dr Whittington is a member of the community and his letter contains a statement. However, a reading of the phrase “statements provided on behalf of…other members of the community” as intended to refer to a letter containing a psychiatric opinion from Dr Ogawa’s consulting psychiatrist would be quite artificial. There are indications to the contrary found, not only in the language used, but from the context, including the nature of the issue the Minister found crucial (risk to the Australian community) and the content of Dr Whittington’s letter and its significance to that issue.

110 As the primary judge pointed out, Dr Whittington was not just a member of the community. He was Dr Ogawa’s consulting psychiatrist. If the Minister had regard to the letter, it is likely he would have expressly referred to Dr Whittington as Dr Ogawa’s psychiatrist. The Minister referred at para 27 to the absence of evidence that Dr Ogawa was mentally impaired at the time of her offending, so that psychiatric evidence was regarded by the Minister as significant to his decision. That makes it probable that he would have referred to the psychiatric evidence that was present if he had considered Dr Whittington’s letter.

111 It was crucial to the Minister’s decision that Dr Ogawa posed an ongoing risk to the Australian community because of the risk that she might reoffend. That may be seen from the Minister’s conclusion at para 46 that, “I could not rule out the possibility of further offending by Dr OGAWA”, and at para 47 that “Dr OGAWA represents an unacceptable risk of harm to the Australian community.”

112 The risk of a person reoffending must be a function, at least in part, of the condition of the person’s mind. Dr Whittington, as a psychiatrist, has obvious expertise in relation to the functioning of the human psyche. He expressed the opinion that during the period of her consultations with him, “there has been no indication that Dr Ogawa is a risk to the community”. That was an opinion apparently reached as a result of the application of his expertise to his observations of Dr Ogawa over a period of four years. An obvious inference capable of being drawn was that as Dr Ogawa had provided no indication of being a risk to the community over the past four years, she posed no such risk in the future. As was observed by the High Court in Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Guo (1997) 191 CLR 559 at 575, “determining what is likely to occur in the future will require findings as to what has occurred in the past because what has occurred in the past is likely to be the most reliable guide as to what will happen in the future”. It was, of course, open to the Minister to reject Dr Whittington’s opinion and to reject that inference, but if he considered and rejected those matters, it is likely that he would have said so. It is highly improbable that, had he considered it, the Minister would not have at least commented upon the opinion of an expert upon the very issue that the Minister found at para 47, “outweighed any countervailing considerations”.

113 A further indication that the Minister did not have regard to the information in Dr Whittington’s letter is found in the Departmental submission to the Minister that accompanied the draft statement of reasons. The submission stated:

Letters in support of DR OGAWA’s visa application and character in general have been provided by DR OGAWA’s colleagues and a former student along with other community members, including her local barista, the manager of a B & B she frequents and her doctor.

(Underlining added.)

114 The reference to “her doctor” was to Dr Bruce Watts, who had provided a letter dated 9 February 2017 in support of Dr Ogawa. The letter was not a medical report, and merely contained statements that he, “always found her to be a pleasant person full of interesting information” and that he considered her, “to be of good character”. If a doctor who provided a non-medical letter of support merited an express reference as “her doctor”, it seems probable that if the author of the submission had read Dr Whittington’s letter, which expressly dealt with a psychiatric issue, he would have expressly referred to that letter, and referred to Dr Whittington as “her psychiatrist”. The author evidently thought it was important enough to expressly mention by occupation, “her local barista” and “the manager of a B & B”. The fact that the author did not refer to “her psychiatrist” strongly suggests that he overlooked Dr Whittington’s letter, and that the error spilled over into the statement of reasons drafted for the Minister, which the Minister adopted by signing.

115 The Minister submits that his statement of reasons should be given “a beneficial construction”. In Collector of Customs v Pozzolanic Enterprises Pty Ltd (1993) 43 FCR 280 at 287, the Full Court stated that an administrative decision-maker’s reasons, “are not to be construed minutely and finely with an eye keenly attuned to the perception of error”. In Minister for Immigration & Ethnic Affairs v Wu Shan Liang (1996) 185 CLR 259, the High Court observed at 272 that this passage, “recognise(s) the reality that the reasons of an administrative decision-maker are meant to inform and not to be scrutinised upon over-zealous judicial review by seeking to discern whether some inadequacy may be gleaned from the way in which the reasons are expressed”.

116 However, that approach does not demand that any ambiguity be resolved in favour of the decision maker: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union v Abigroup Contractors [2013] FCAFC 148 at [190]. In the absence of any express reference to Dr Whittington’s letter, it is the Minister who relies upon the ambiguity of para 33 of his reasons. However, the language of that passage, together with the matters of context we have pointed to, demonstrate that the ambiguity should be resolved against the Minister. The Minister’s reasons cannot be construed as referring to Dr Whittington’s letter.

117 The Minister made general statements that, “I have considered all relevant matters including…all information before me provided by or on behalf of Dr Megumi OGAWA”, and, “I considered all relevant matters including…all other evidence available to me, including information provided by, or on behalf of Dr OGAWA”. These statements demonstrate that the Minister believed that he had considered all the relevant information. However, no person can know what he or she has overlooked. That is what has been described in other contexts as an “unknown unknown”—the Minister does not know what he does not know. The Minister’s general statements are not inconsistent with the Minister having overlooked Dr Whittington’s letter.

118 In Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSRS [2014] FCAFC 16, the Full Court said at [34]:

In some cases, having regard to the nature of the applicant’s claims and the findings and evidence set out in the reasons, it may be readily inferred that if the matter or evidence had been considered at all, it would have been referred to in the reasons, even if it were then rejected or given little or no weight.

119 In our opinion, this is such a case. We consider that the Minister failed to have regard to the information in Dr Whittington’s letter in breach of his obligation under s 56 (1) of the Act.

120 Whether that error amounted to jurisdictional error depends upon whether the information overlooked was “material”. Dr Ogawa is not required to demonstrate that the information is likely to have changed the outcome, but only that it denied her a possibility of successful outcome, or could realistically have resulted in a different decision: cf Hossain at [30], [72]; Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA [2019] HCA 3, (2019) 363 ALR 599 at [45], [128]. Dr Whittington’s letter contained an expert’s opinion upon matters that the Minister considered critical to his decision, namely whether Dr Ogawa posed a risk to the Australian community and the extent of that risk. The Minister’s assessment was that Dr Ogawa posed a low but unacceptable risk. The Minister’s assessment of whether there was any risk and the extent of any risk may realistically have been different if he had regard to Dr Whittington’s opinion. It follows that the decision may realistically have been different. The Minister’s error was therefore a material error.