FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 83

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The Appellant pay the Second Respondent’s costs as assessed or agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

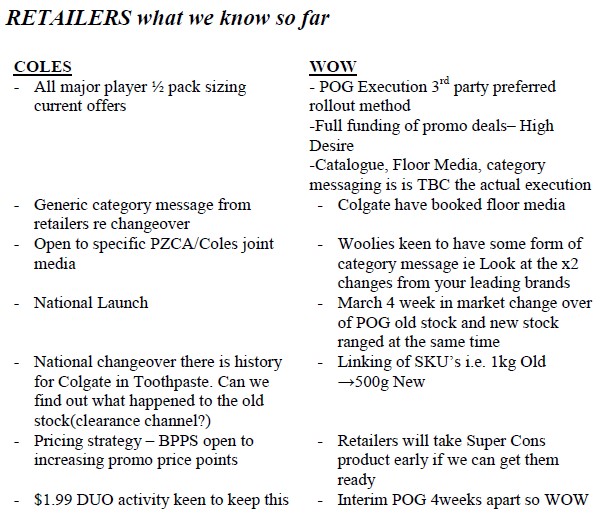

1 In the year 2008, the Australian laundry detergent market was large with approximate sales of $500 million. The Respondents, PZ Cussons Australia Pty Ltd (‘Cussons’) and Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (‘Colgate’), together with Unilever Australia Limited (‘Unilever’) (collectively, ‘the Suppliers’) were the largest manufacturers and wholesale suppliers of laundry detergents in the Australian market having between them around an 80% market share.

2 In March 2009 there was a significant change in the market for powdered laundry detergents. The Suppliers each launched new formulations of their existing laundry powders which were twice the concentration of their existing powders. They supplied these new ‘ultra-concentrate’ formulations (as they were called) to their main customers: Woolworths Limited (‘Woolworths’), Coles Group Pty Ltd (‘Coles’) and the wholesaler, Metcash Limited (‘Metcash’). Over a relatively short period, and at approximately the same time, they ceased supplying their standard concentration laundry powders to Woolworths, Coles and Metcash, although they did continue to supply some of these powders to other independent retailers and variety stores. The overall effect, however, was that in a large part of the market for laundry powders all of the standard concentrate products disappeared and were quickly replaced by ultra-concentrate products.

3 Arising out of this event, the Appellant (‘the Commission’) sued Colgate and Cussons alleging anti-competitive conduct on their part. It also sued Woolworths and an officer of Colgate contending that they were knowingly concerned in or a party to the alleged contraventions. The Commission did not commence proceedings against Unilever, apparently because it was an immunity recipient. Prior to trial, all of these parties except Cussons settled with the Commission but the trial continued against Cussons. The Commission’s basic case was that the largely simultaneous and almost uniform transition from standard to ultra-concentrated powders resulted from a collusive arrangement or understanding between Colgate, Cussons and Unilever that they would hold off bringing the ultra-concentrate products to market until a date in March 2009 and at the same time cease supplying the standard concentrates thereafter.

4 Were it to be established, such an arrangement or understanding between Colgate, Cussons and Unilever would be between competitors containing exclusionary provisions restricting the supply of goods into a market. In the interests of brevity, it is useful to refer to this alleged arrangement or understanding as the Withhold Supply Arrangement, it being understood that the reference to an arrangement includes a reference to an understanding. There are complex prohibitions preventing, in many instances, the reaching by competitors of arrangements or understandings of this kind and there are related prohibitions against giving them effect. In the interests of completeness, we explain these provisions in the next section but they are of little moment for the purposes of the present appeal for there is no debate that if the Commission failed, as a matter of fact, to prove the existence of the Withhold Supply Arrangement, then its case had to fail. At trial, the Commission failed precisely on that basis. The trial judge concluded that the Commission had not succeeded in proving that Cussons had arrived at the Withhold Supply Arrangement with Colgate and Unilever. Whilst his Honour accepted that Colgate, Cussons and Unilever were conscious they were all going to transition to ultra-concentrates at the same time, his Honour did not think this was because they were acting pursuant to a collusive arrangement or understanding. Rather, the trial judge was impressed by evidence which suggested that it was Woolworths and Coles which had largely driven the timing of the transition to ultra-concentrates. This was so they could devote less shelf space to laundry powders, a product range which they did not regard as particularly profitable (that is, they did not wish to have both ordinary strength powder and ultra-concentrates taking up shelf space). The trial judge also accepted evidence which suggested that Cussons was, to a large extent, ignorant of what the other Suppliers and retailers were doing in the lead up to the transition in March 2009.

5 It is from these adverse conclusions that the Commission now appeals. By its amended notice of appeal, the Commission pursues ten grounds of appeal which it grouped together under five sections labelled A-E. Section A, which comprised Grounds 1-3, involved the basic contention that the trial judge, whilst correctly identifying the legal nature of an arrangement or understanding for the purposes of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (‘TPA’), had in substance erroneously applied a higher standard by requiring the Commission to prove the existence of a contract or agreement. Under Section B (Grounds 4-5), the argument was that trial judge had erred in preferring the hypothesis of conscious parallelism over the existence of the Withhold Supply Arrangement. Under Section C (Grounds 6-7) the Commission took issue with the trial judge’s conclusion that the switch to ultra-concentrates had been driven by the attitudes of Woolworths and Coles. Under Section D (Grounds 8-9), the Commission argued that, in the event that it established on appeal that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been reached, it had also been implemented. Under Section E (Ground 10) the Commission contended that the trial judge had made 11 errors of fact, which were identified in an annexure to the amended notice of appeal. In the event that the Commission succeeded in establishing error on the part of the trial judge, it then identified how its case operated at trial and invited the Full Court to reach the conclusions that the trial judge had refused to reach.

6 For the reasons which follow, the Commission’s appeal should be dismissed with costs.

7 These reasons proceed as follows:

8 It is useful to begin with the two statutory regimes applicable to the case. There are two schemes involved because the contraventions alleged against Cussons included not only the allegation that it reached the impugned arrangement or understanding with its competitors but also that it implemented it over an extended period of time. The Withhold Supply Arrangement was alleged to have been reached by 31 January 2009 with implementation occurring on and after that date. On 24 July 2009, during the period in which implementation was alleged, the TPA was amended in ways which impact on the allegation that Cussons gave effect to the Withhold Supply Arrangement. It is necessary, therefore, not only to examine the scheme of regulation as it existed up until 24 July 2009 but also the scheme of regulation as it existed after that day. As an added distraction, subsequent to those amendments the name of the TPA was changed to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) although this is not material to any issue. We will refer to it as the TPA.

The TPA prior to 24 July 2009: Making and implementation of the Withhold Supply Arrangement

9 Section 45(2) of the TPA prohibited the making of an understanding containing what it referred to as an ‘exclusionary provision’. Its precise terms were these:

45 Contracts, arrangements or understandings that restrict dealings or affect competition

…

(2) A corporation shall not:

(a) make a contract or arrangement, or arrive at an understanding, if:

(i) the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding contains an exclusionary provision; or

(ii) a provision of the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding has the purpose, or would have or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition; or

(b) give effect to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, whether the contract or arrangement was made, or the understanding was arrived at, before or after the commencement of this section, if that provision:

(i) is an exclusionary provision; or

(ii) has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition.

10 A number of aspects of this deserve emphasis. First, it will be seen that the prohibition was not just on the reaching of understandings but also on the making of contracts or arrangements. It is worth noting the distinction at this early juncture because a part of the Commission’s argument before the Full Court is that whilst the trial judge had correctly identified the principles governing how an arrangement or understanding might be established as a matter of law, his Honour had in substance approached the matter by requiring the Commission to demonstrate that Cussons and the other Suppliers had entered into a contract. Although this is explained in more detail later in these reasons, the basic point was that the trial judge had, in effect, set the forensic bar too high.

11 Secondly, it will be seen that the provision has two limbs and that each of those limbs has two further sub-limbs. Each is relevant to the appeal. Section 45(2) draws a distinction between making a contract or arrangement or arriving at an understanding under subs (2)(a), and giving effect to a contract, arrangement or understanding under subs (2)(b). The contract, arrangement or understanding, whether initially arrived at or subsequently given effect to, must have one of two further qualities. It must either contain an ‘exclusionary provision’ or it must have the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. The effect of the drafting of s 45(2) is that once an understanding contains an exclusionary provision a breach of s 45(2) is established without the need for any further inquiry into whether the understanding had the effect of substantially lessening competition. In effect, the presence of an exclusionary provision creates a per se contravention of s 45(2). However, even if the arrangement or understanding does not contain an exclusionary provision it remains open under ss 45(2)(a)(ii) or (b)(ii) to demonstrate that it, in fact, had the effect (or likely effect) of substantially lessening competition. From an evidentiary perspective, this second limb is more burdensome than the per se path under ss 45(2)(a)(i) or (b)(i) for it requires the moving party, here the Commission, to demonstrate a substantial lessening of competition in the relevant market.

12 All of this is material because the Commission pursued all four avenues at trial. It alleged that there was an arrangement or understanding which contained an exclusionary provision; and that, even if it did not, the arrangement or understanding was likely to substantially lessen competition. Further, it was said that Cussons implemented the arrangement or understanding in the same two circumstances. Thus cases were pursued under each of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and (ii) and ss 45(2)(b)(i) and (ii).

13 Section 45(2) left unanswered the question of what an ‘exclusionary provision’ was. It was defined in s 4D in these terms:

4D Exclusionary provisions

(1) A provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, shall be taken to be an exclusionary provision for the purposes of this Act if:

(a) the contract or arrangement was made, or the understanding was arrived at, or the proposed contract or arrangement is to be made, or the proposed understanding is to be arrived at, between persons any 2 or more of whom are competitive with each other; and

(b) the provision has the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting:

(i) the supply of goods or services to, or the acquisition of goods or services from, particular persons or classes of persons; or

(ii) the supply of goods or services to, or the acquisition of goods or services from, particular persons or classes of persons in particular circumstances or on particular conditions;

by all or any of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding or of the proposed parties to the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding or, if a party or proposed party is a body corporate, by a body corporate that is related to the body corporate.

(2) A person shall be deemed to be competitive with another person for the purposes of subsection (1) if, and only if, the first-mentioned person or a body corporate that is related to that person is, or is likely to be, or, but for the provision of any contract, arrangement or understanding or of any proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, would be, or would be likely to be, in competition with the other person, or with a body corporate that is related to the other person, in relation to the supply or acquisition of all or any of the goods or services to which the relevant provision of the contract, arrangement or understanding or of the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding relates.

14 It will be seen that ss 4D(1)(a) and (2) require that Cussons and the other Suppliers should have been in competition with each other. There is no debate on the appeal that the Suppliers were in competition in that sense. Of more importance is the stipulation in s 4D(1)(b) which turns relevantly on the arrangement or understanding containing a provision which has the purpose of restricting or limiting the supply of goods or services. The Commission put its case on the basis that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had the purpose of restricting the supply of ultra-concentrates before the change-over date and the supply of standard concentrates thereafter.

The TPA after 24 July 2009: Subsequent implementation of the Withhold Supply Arrangement

15 The second regime became applicable on 24 July 2009. On the Commission’s case, the Withhold Supply Arrangement had by then been reached so that only those parts of this second regime dealing with implementation are material. The new prohibition was contained in s 44ZZRK:

44ZZRK Giving effect to a cartel provision

(1) A corporation contravenes this section if:

(a) a contract, arrangement or understanding contains a cartel provision; and

(b) the corporation gives effect to the cartel provision.

Note: For enforcement, see Part VI.

(2) Paragraph (1)(a) applies to contracts or arrangements made, or understandings arrived at, before, at or after the commencement of this section.

16 This does not tell one very much unless one knows what a ‘cartel provision’ is. That expression was defined in s 44ZZRD(1) in these terms:

44ZZRD Cartel provisions

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is a cartel provision if:

(a) either of the following conditions is satisfied in relation to the provision:

(i) the purpose/effect condition set out in subsection (2);

(ii) the purpose condition set out in subsection (3); and

(b) the competition condition set out in subsection (4) is satisfied in relation to the provision.

17 In this case, only the ‘purpose condition’ referred to in s 44ZZRD(1)(a)(ii) is relevant, it not being in contest that the competition condition in s 44ZZRD(1)(d) was satisfied. The purpose condition was set out in s 44ZZRD(3):

Purpose condition

(3) The purpose condition is satisfied if the provision has the purpose of directly or indirectly:

(a) preventing, restricting or limiting:

(i) the production, or likely production, of goods by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(ii) the capacity, or likely capacity, of any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding to supply services; or

(iii) the supply, or likely supply, of goods or services to persons or classes of persons by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(b) allocating between any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding:

(i) the persons or classes of persons who have acquired, or who are likely to acquire, goods or services from any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(ii) the persons or classes of persons who have supplied, or who are likely to supply, goods or services to any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(iii) the geographical areas in which goods or services are supplied, or likely to be supplied, by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(iv) the geographical areas in which goods or services are acquired, or likely to be acquired, by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(c) ensuring that in the event of a request for bids in relation to the supply or acquisition of goods or services:

(i) one or more parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding bid, but one or more other parties do not; or

(ii) 2 or more parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding bid, but at least 2 of them do so on the basis that one of those bids is more likely to be successful than the others; or

(iii) 2 or more parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding bid, but not all of those parties proceed with their bids until the suspension or finalisation of the request for bids process; or

(iv) 2 or more parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding bid and proceed with their bids, but at least 2 of them proceed with their bids on the basis that one of those bids is more likely to be successful than the others; or

(v) 2 or more parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding bid, but a material component of at least one of those bids is worked out in accordance with the contract, arrangement or understanding.

Note 1: For example, subparagraph (3)(a)(iii) will not apply in relation to a roster for the supply of after-hours medical services if the roster does not prevent, restrict or limit the supply of services.

Note 2: The purpose condition can be satisfied when a provision is considered with related provisions—see subsection (9).

Note 3: Party has an extended meaning—see section 44ZZRC.

18 The effect of this is that if the Withhold Supply Arrangement contained a provision whose purpose was to restrict or limit the production of goods then it would contain a cartel provision and would thus be, in turn, a contravention of s 44ZZRK to give effect to it. In this case, these provisions operated no differently to the manner in which ss 45(2) and 4D had operated prior to 24 July 2009. No difference in operation was suggested on appeal.

19 It is then necessary to trace in outline the evidentiary landscape which the trial judge traversed in his consideration of whether the Commission had succeeded in proving the existence of the Withhold Supply Arrangement.

20 The arrangement or understanding alleged by the Commission, the Withhold Supply Arrangement, was put by the Commission at [57] of its amended statement of claim. In essence, the allegation was that the arrangement or understanding contained provisions to the effect that Colgate, Unilever and Cussons would prevent, restrict or limit the supply of ultra-concentrates to Woolworths, Coles and Metcash until a particular date (originally slated to be in January 2009, but subsequently pushed back to March 2009) and standard concentrates from that date. As the trial judge noted at [24], there was really no dispute about the primary facts upon which the Commission relied. The debate lay rather in what could be inferred from those facts. These primary materials consisted of the fact of several meetings, presentations and a number of emails. As the trial judge also noted at [27] these materials did not exhaust the universe of evidence upon which the Commission relied but they were nevertheless the matters which the Commission explicitly invoked as supporting the alleged arrangement or understanding.

21 The trial judge explained the events leading up to the change in terms which are not now in dispute. The following account draws heavily on his Honour’s primary findings at [100]-[380]. During 2008, the majority of powdered and liquid detergent products were formulated in a way which the parties were content to refer to as standard concentrates. However, global trends had revealed by 2008 that ultra-concentrates were on the march. Indeed, in 2007 the supply in Europe and the United States had shifted to ultra-concentrates. What is an ultra-concentrated laundry detergent? It is a product containing less inert or inactive ingredients which in consequence allows a smaller amount of detergent to produce the same washing result. There were benefits to ultra-concentrates for the manufacturers including lower production, transportation and storage costs. There were also benefits to retailers because ultra-concentrates occupied less shelf space allowing them to increase the revenue derived from their shelves. It was also suggested, perhaps tangentially, that they were better for the environment.

22 By at least January 2008 all three Suppliers were aware of the international trend towards the introduction of ultra-concentrates which is unsurprising since each was a subsidiary of large multinational. The only real issue was when the transition would take place. By late 2007 or early 2008 each of the manufacturers was actively considering how the transition would be managed. Colgate had in late 2007 begun an internal project called ‘Ultra’ whose purpose was to bring about the transition by January 2009. Cussons had its own internal ‘Project Mastermind’ which began in January 2008 and which set a target implementation date of January or February 2009. For its part, Unilever had ‘Project Fraser’ which had commenced in November 2007 and had a target for implementation of January or February 2009.

23 Each of the manufacturers perceived that the switch to ultra-concentrates would give them an opportunity to increase their margins because they could reduce their production, packaging and transportation costs. This was seen as particularly important in the face of poor growth and declining margins on laundry powders. But there was also a risk that the transition would give rise to the spectre of consumer confusion. It was thought that a consumer faced with two products, both at about the same price, but one of which was in a larger package and which appeared to contain more detergent, would be more likely to purchase the product in the larger package. This created a risk if some of the Suppliers moved to introduce ultra-concentrates but some chose not to, that the latter might increase their market share to the detriment of the former. The Suppliers’ planning involved consideration of this risk including whether it could be surmounted by means of an industry initiative or agreement via an industry association or whether it might be resolved by the major retailers taking the lead. By that, what appears to have been intended was that one of the major retailers, such as Coles or Woolworths, would dictate to the Suppliers when the transition was to occur. In that regard, it is to be noted that all three Suppliers were well aware that in 2008 the transition to ultra-concentrates in the United States had been led by Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (‘Walmart’).

24 Woolworths and Coles conducted two reviews per year for the laundry products which they sold. These were called ‘range reviews’. There was a major range review held in around February each year and a minor one which was typically held in July. For the major review in February the entire range of laundry detergents supplied by the manufacturers was reviewed. As part of this process the Suppliers gave presentations to the retailers about consumer and industry insights, the performance of the category, the development of their products, the products they wanted to supply to the retailers and why the retailer should ‘range’ those products (i.e. put them on their shelves). The Suppliers understood that if they were going to make a major change to their product range, such as switching to ultra-concentrates, they would have to meet the retailers’ timetable. That fact explains why the Suppliers met with Woolworths on a number of occasions about the transition, particularly in the latter half of 2008. The proximity between the major range review in February 2009 and the actual transition in March 2009 may be usefully noted at this juncture. One debate at trial concerned the extent to which the retailers could dictate to the Suppliers when the transition was to occur. The Commission submitted that the retailers lacked the ability do that; Cussons submitted to the contrary that it was captive to the whims of Woolworths.

25 Attempts early in January 2008 to persuade Woolworths to take the same role in the transition process as Walmart in the United States appear not to have resulted in anything concrete. On 10 March 2008, there was a meeting between Colgate and Accord Australasia Ltd (‘Accord’). Accord was the national industry association for the Australasian hygiene, cosmetic and specialty products industry. It was Colgate that first approached Accord to see if it could take the lead in the transition. At the meeting on 10 March 2008 Colgate presented a ‘sustainability initiative’ proposal. The proposal would cover all Suppliers and retailers of laundry detergent. There was to be a full category transition to ultra-concentrates with an agreed transition date being in either January or July 2009 to align with the range reviews of Woolworths and Coles. Colgate followed up after the meeting with a document which summarised the proposal. Thereafter Accord distributed this proposal to Unilever and Cussons (as well as Colgate) and suggested that a meeting be held on 30 April 2008.

26 Cussons’ initial response to the proposal was negative. An internal memorandum suggested that there could be competition law problems with it and Cussons obtained oral legal advice to that effect on 30 April 2008. That legal advice was that Cussons should not agree, or give the impression of agreeing, to any aspect of the Accord proposal. This advice was eventually reduced to writing in August 2008. Unilever’s internal response to the Accord proposal was also negative and included being concerned about its legality from a competition law perspective.

27 Nevertheless, the meeting proceeded on 30 April 2008. The trial judge did not think that any clear agreement came out of this meeting although his Honour did allow that Colgate seemed to have a more positive perception that some kind of agreement in principle had been reached about various matters including a date for transition. Significantly, however, his Honour came to the view that despite Colgate’s positivity no such agreement had in fact been reached. He then noted that in any event it had been decided that any arrangement would need to be submitted to Accord’s lawyers and the Commission itself for approval.

28 There then followed between May and August 2008 a series of meetings between Woolworths and the Suppliers. There were also a series of in-house workshops on the transition process. The trial judge analysed each of these closely at [169]-[301]. It is not necessary, however, to dwell upon any of this in detail. In August 2008, Accord circulated to the Suppliers a revised proposal. It had a number of features including ‘an agreed timeframe for meeting the concentration guidelines’. At an earlier time Accord had obtained legal advice about the proposal. It had been advised that the proposal did not contain an exclusionary provision and was not likely to substantially lessen competition. Cussons now obtained its own written legal advice (which was a more formal statement of the earlier oral advice it had received). It differed from the advice proffered to Accord in that it suggested that there was a real risk that the proposal did contain an exclusionary provision. Cussons was advised that whilst it could attend any proposed meeting it should not agree to anything and that no matters of sensitivity, such as price, were to be discussed.

29 A meeting at the offices of Accord’s lawyers was held on 25 August 2008. There was evidence which the trial judge accepted that Cussons had said at this meeting that it wanted a transition arrangement under which Suppliers could transition in a staggered way and that this position was driven by the legal advice it was getting. Colgate’s perception was that Cussons was playing a role as a ‘rogue player’ for its own commercial purposes and was using its legal advice as some kind of excuse. An internal report prepared by Unilever records that before any agreement was reached, approval would be sought from the Commission.

30 The trial judge was impressed by this material. His Honour rejected the Commission’s submission that by the time of this meeting ‘the essential elements of the transition had already been put in place’. He thought the evidence to which reference has just been made showed that this could not have been the case. Further, his Honour rejected the Commission’s contention that the Suppliers—including Cussons—had been using Accord as a ‘hub’ through which they could communicate to form understandings. Again, this was rejected because the communications which were established were inconsistent with that contention.

31 Following this there were further meetings and communications which the trial judge also did not think assisted the Commission’s case. There was evidence that in August 2008 both Colgate and Unilever were increasingly clear that the transition date would be in early March 2009. But the evidence linking Cussons to this was thought by the trial judge to be thin. It was true that Cussons was aware by September 2008 that one of the other Suppliers had asked for the transition date to be moved back to March 2009 but the trial judge thought that Cussons remained unclear about what Woolworths’ start date would actually be.

32 There was other evidence which led the trial judge to doubt that Cussons had any real involvement in what was taking place. For example, on 9 September 2008 Unilever had conducted what it referred to as ‘stress tests’ designed to deal with the possibility that Cussons would fail to switch to ultra-concentrates at the same time that it did. The trial judge accepted evidence from Unilever that in September 2008 it did not know what Cussons’ intentions were.

33 At around this time, on 18 September 2018, Cussons distributed to its employees working on Project Mastermind a direction about how they should handle encounters with competitors in relation to the launch of ultra-concentrates. In short, such communications were forbidden, whether formally or informally. The trial judge rejected the Commission’s submission about this direction that it was too late in the piece and had frequently been breached.

34 In October 2008, there were further meetings and communications. The trial judge found that by this stage Cussons’ internal documents showed it was targeting a February 2009 transition date but that it remained itself uncertain about what Woolworths’ intentions actually were. His Honour also thought that Cussons had a limited understanding of what Colgate and Unilever were proposing. Of some significance was an internal Cussons’ ‘session’ which took place on 21 October 2008 described as a ‘war-gaming session’. The purpose of this session was to consider different scenarios to which Cussons might have to respond after the ultra-concentrates were launched. Internal documents at this time suggested that Cussons did not know what price the other Suppliers were going to charge for their ultra-concentrates, how big the powder scoop would be, what performance or environmental claims might be made, or what the concentration level would be (‘ultra’ encompassing, as it turns out, a range of higher strength powders). The trial judge was impressed by this evidence and observed that the material did not suggest any awareness on Cussons’ part as to when the products might be launched. His Honour thought it inconsistent with the Commission’s case because if there had been the collusive arrangement or understanding which it alleged, then this kind of war-gaming activity would have been unnecessary. His Honour rejected the Commission’s submission—repeated on appeal—that the war-gaming evidence was consistent with the Withhold Supply Arrangement because it could be characterised as evidence of the steps to be taken in the event that the other parties to the collusive understanding cheated on it. His Honour rejected this contention on the basis that there was no evidence for it and it had not been put to any of the witnesses called by Cussons.

35 By November 2008, the trial judge thought that the emails passing between the various parties showed that the Suppliers’ transition plans had been finalised and that the ultra-concentrates were to be launched as part of the retailers’ major range review which had been moved from February to March 2009. Coles, for example, emailed the Suppliers on 4 November 2008 telling them that only the ultra-concentrates were going to form part of the range review and that implementation would occur on 2 March 2009. On 19 November 2008 an internal Woolworths email suggested that the launch date would be early March 2009. This evidence was said by Cussons to locate the decision with the retailers. The Commission’s response to this problem at trial was a ‘hub and spoke’ model under which Accord (and after it bowed out, the retailers) were to be seen as a kind of forum through which the Suppliers signalled their intentions to one another and by means of which they were able to reach the Withhold Supply Arrangement.

36 On 27 November 2018, the Cussons board gave formal approval for the transition to ultra-concentrates. When it made that decision it had before it a situation analysis which included within it the statement that the ‘[r]etailers are driving [the] timing based on category review timings and any supplier who does not meet these timings will be disadvantaged with ranging, shelf-positioning, etc’ together with other statements to the effect that Accord was no longer leading the transition timing and that ‘all players will now communicate the changes independently’.

37 In December 2008, there were internal Unilever emails which suggested an ongoing concern on its part that Cussons might be a ‘rogue player’. At the same time, Woolworths was delving into the detail of the transition providing, inter alia, information from the Suppliers about package sizes and what its shelves would look like after the transition.

38 The real-world process of transition began in February 2009 when the Suppliers commenced to supply ultra-concentrates (now known to be double strength) to Woolworths, Coles and Metcash. There was evidence that some of Cussons’ products began to be sold to the public in February 2009, as there was in the case of Unilever too. Further, Metcash continued to purchase standard concentrates for some time after February 2009. The evidence outlined by the trial judge about the transition did not, therefore, completely cohere with the Commission’s case of a sudden transition in early March 2009. The process appears to have been somewhat less tidy. There were other difficulties too which the trial judge noted such as considerable uncertainty about what the package and scoop sizes would be.

39 The trial judge came to the view that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had not been arrived at. His Honour thought that the evidence strongly suggested that it was the retailers who had driven the timing. This view was confirmed, his Honour also thought, in a video produced by Unilever and Woolworths in late 2009 in which a Woolworths official, Mr Fuchs, and a Unilever official, discussed the transition. The following was said:

Mr McNeil said: “But it was their role in getting all of the players in the industry to move simultaneously. That really made the biggest difference of all.”

Mr Fuchs said: “This was really important. I think firstly because we didn’t want any confusion with the customers, we wanted everything to change over at the same time. Also from a cost point of view that we did one layout and we didn’t have to continuously change.”

40 The trial judge noted that the Commission had not called Mr Fuchs and that the video supported the idea that it was the retailers who drove the timing.

41 The evidence considered by the trial judge went into much more detail than the above short summary does but it will suffice for present purposes to explain the broad features of the evidence. It will be reasonably plain from the above that the trial judge thought the Commission’s case was to an extent inconsistent with the available evidence.

42 It is then useful to turn to the Commission’s grounds of appeal.

SECTION A: STANDARD OF PROOF APPLIED BY THE TRIAL JUDGE

43 The first ground of appeal was that the trial judge had correctly stated the legal principles governing what an arrangement or understanding was but had then preceded to misapply them. There were submitted to be two elements to his Honour’s error. The first was that he had required the identification of when, and by whom, the understanding had been reached, and the second was that his Honour erroneously approached the matter on the basis that the Commission had to show the existence of a contract. In its written submissions on the appeal, the Commission pursued these together with the basic contention being that the trial judge had required it to prove the existence of a contract rather than the less formal consensual dealing constituted by an arrangement or understanding.

44 This ground was put on two bases. First, it was said that by asking himself the wrong question (i.e. whether there was a contract) and thereby declining to draw the inference that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been reached, his Honour had erred and that the Court should therefore interfere under Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; 142 CLR 531 at 551 per Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ. Here the point was that once error was established this Court was in as good a position as the trial judge to draw inferences from the evidence. Secondly, the Court was invited to draw the conclusion that it sufficiently disagreed with the trial judge’s refusal to draw the inference that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been reached by Cussons that it could conclude not just that the Court disagreed with the trial judge but that the extent of the disagreement was such that an error must have been made on the trial judge’s part: Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424 (‘Branir’) at 435-436 [24] per Allsop J; Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 358 ALR 683 (‘Moroccanoil’) at 685 [2], 686-687 [4], 688 [8], 689 [10] per Allsop CJ, 696 [49]-[51] per Perram J and 724 [169] per Markovic J.

45 There was no dispute that the trial judge had correctly stated the relevant principles (at [46]-[51]). His Honour concluded that a contract within the meaning of ss 4D and 46(2) occurred where an offer was made by one party and accepted by another, was supported by consideration and there was an intention to create a legally binding relationship: at [46]. He went on to observe that ‘[p]erhaps unsurprisingly, anti-competitive arrangements are rarely, if ever, enshrined in formal contracts. The Commission did not allege that Cussons entered into a contract with Colgate or Unilever’. It is, of course, possible that the trial judge then proceeded to look for a contract which his Honour had explicitly noted was not being advanced by the Commission but his Honour’s observation is a strong indicator that he knew what the significance of a contract was and that he knew that this was not the Commission’s case.

46 Next the trial judge noted that an ‘arrangement’ generally connoted a consensual dealing between parties which was less formal than a contract but nevertheless was something which was ‘made’ (because the word ‘make’ was used in s 46(2)). This tended to suggest that ‘an arrangement would generally require some degree of negotiation or communication between the parties concerning the terms of provisions of the arrangement’: at [48]. The Commission again accepted that this statement was correct. His Honour next noted that an ‘understanding’ was something which could be ‘arrived at’ rather than being made and was something therefore which was even less formal than an arrangement and, in particular, could be tacit: at [49]-[50]. Both an arrangement and an understanding (and we would add a contract) all share the common feature that there must be a meeting of the minds. The Commission accepted the correctness of all of this.

47 So there is no doubt that the trial judge understood the differences between the three concepts. The Commission’s case before this Court is that thereafter the trial judge proceeded to search for a contract rather than an arrangement or understanding. This contention was said to be demonstrated by five matters. These were that his Honour had:

(1) demanded an elevated level of precision in identifying when, and by whom, the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been made which was not required by the applicable principles;

(2) emphasised the absence of direct communications between the Suppliers regarding the Withhold Supply Arrangement when it was not a requirement of the law that there be such a direct communication;

(3) observed on a number of occasions that the evidence had not established that Cussons was under any commitment or obligation to the other Suppliers in respect of the transition to ultra-concentrates when that was not a requirement that needed to be proved to establish an arrangement;

(4) erred in thinking that the fact that he had concluded that Cussons did not know or intend that its statements at Accord meetings (or to Woolworths) were to signal or induce the other Suppliers meant that there was no arrangement. The Commission said that knowledge or intention of that kind was sufficient to establish an arrangement but the fact that it was established that no such knowledge or intention was possessed did not necessarily imply that there was no arrangement. This argument did not appear to be contained in Section A of the amended notice of appeal. It was included in the Commission’s written submissions; and

(5) erred in his application of the legal standard by failing to consider whether the vertical communications or arrangements between each Supplier and Woolworths only made sense if they were engaging in a common undertaking. This argument did not appear to be contained in Section A either but was put in its written submissions.

48 It is then useful to consider these five matters separately.

Did the trial judge impose an elevated level of precision in identifying when, and by whom, the Withhold Supply Understanding had been made?

49 The Commission submitted that it was significant to the trial judge’s reasoning that its pleaded case did not specify when the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been made or through which employees Cussons had arrived at the arrangement. This significance was to be found at [439]-[440] of the trial judge’s reasons:

As was noted at the very outset, the Commission’s pleaded case did not specify exactly when the Withhold Supply Arrangement was entered into, or arrived at. It was simply alleged that the arrangement or understanding had been made or arrived at between 18 April 2008 and 31 January 2009. The first date in that range, 18 April 2008, was the date that Ms Capanna circulated Colgate’s Accord proposal to, amongst others, Cussons, Colgate and Unilever. The significance of the end-date, 31 January 2009, was and is unclear from the pleading. The last of the meetings or communications that was specifically pleaded in the ASOC was an email from Mr Fuchs of Woolworths dated 5 January 2009. The chronology of key communications and events annexed to the Commission’s closing submissions similarly did not disclose any specific event on 31 January 2009.

Nor did the Commission’s pleaded case identify the officers of Cussons who were alleged to have caused Cussons to make the alleged arrangement, or arrive at the alleged understanding with Colgate and Unilever. Indeed, the pleading also did not identify the officer or officers of Colgate and Unilever who caused their respective companies to enter into or arrive at the alleged arrangement or understanding, save perhaps for Mr Ansell of Colgate. That is particularly surprising in the case of Unilever, given that Unilever appears to have been an immunity applicant and that the Commission was able to call witnesses from Unilever.

50 Whilst these paragraphs are critical of the way in which the Commission pleaded its case, we do not read them as containing a statement that it was required to plead at what time and by whom the arrangement had been made. In fact, it is apparent that the point the trial judge was endeavouring to make about the pleading at [439]-[440] (and correspondingly about the evidence at [442]) was simply that the Commission’s case was somewhat imprecise and lacking in clarity. Cussons submitted that the difficulties flowing from the diffuse position were multiple and manifest. For example, the particularised claim was that the arrangement had been made at some point between 18 April 2008 and 31 January 2009. But the significance of these dates turned out to be unexplained. The pleading did identify an event as having happened on 17 April 2008. As the trial judge explained at [439], that was the day that Accord circulated Colgate’s proposal. The significance of 31 January 2009 remained unexplained as the trial judge noted. It was to this obscurity that the trial judge returned at [441]-[442] when he addressed the way the arrangement had been particularised:

It would not be unfair to say that, on just about any view, the Commission’s pleaded case in relation to the Withhold Supply Arrangement was imprecise and lacking in particularity and clarity. The Withhold Supply Arrangement was alleged to have been made or arrived at “by reason of” the “matters” alleged in paragraphs 13 – 49 of the ASOC. Those “matters” comprised various communications that occurred between 18 April 2008 and 5 January 2009, together with the fact that on 2 March 2009, each of Cussons, Colgate and Unilever allegedly introduced ultra concentrates across all of their brands, and ceased to supply standard concentrates to Woolworths, Coles and Metcash. The only other particulars of the Withhold Supply Arrangement included in the pleading were that it was partly written and partly oral and wholly or partly implied. The written and oral parts of the arrangement were said to be comprised of the various communications. The facts, matters and circumstances from which the arrangement was to be implied were again said to be the various communications and the simultaneous transition to ultra concentrates in early March 2009.

It would be equally fair to say that the precision and clarity of the Commission’s case did not significantly improve once all of the evidence was tendered. There were, however, some shifts or developments in how the Commission put its case. Some were fairly subtle. Others were fairly fundamental.

51 His Honour had previously flagged his concerns about this at [22]:

Second, the Commission did not, no doubt again because it could not, plead that certain specific officers or employees were responsible for causing Cussons to enter into the alleged arrangements, or arrive at the alleged understandings. A corporation can only relevantly act, or have a state of mind, through its officers or employees. Yet the Commission was unable to say, at least in its pleaded case, who the relevant officers or employees of Cussons were. Indeed, it did not specify who the relevant officers or employees of Colgate or Unilever were either, save for Mr Ansell in Colgate’s case. That was particularly unusual in the case of Unilever, since Unilever was an immunity applicant and its officers and employees gave evidence in the Commission’s case.

52 We do not read these passages as involving the impermissible imposition of a requirement that the Commission identify when the arrangement had been made or by which of its officers. The trial judge was only observing that a case of collusion pitched in such vague terms had its difficulties. The Commission also relied upon a number of other paragraphs of his Honour’s reasons as showing that he had required it to prove when the arrangement had been reached or by whom: [443]-[447], [548]; and [427], [431], [460], [603], [608] and [621]. These paragraphs do not differ in substance from the paragraphs we have just set out. The Commission’s reading of them is not correct.

Did the trial judge erroneously emphasise the absence of direct communications?

53 The Commission submitted that the trial judge had ‘erroneously emphasised’ the absence of direct communication between the Suppliers regarding the Withhold Supply Arrangement. In its submission it was not necessary as a matter of law for direct communications to be established. There is no substance to this contention. Of course, it is true that it was not necessary as a matter of law for the Commission to prove the existence of direct communication in order to demonstrate the existence of an understanding (although it may be necessary in order to prove an arrangement—an issue which does not require resolution). But it does not follow that the absence of direct communications is irrelevant either. Just because an understanding can be tacit does not entail that evidence about the lack of contact between the alleged participants is irrelevant. It goes to the strength of the case being advanced. The trial judge had correctly explained the difference between a contract and an arrangement or understanding and explicitly said he was assessing whether an arrangement or understanding had been reached. In our opinion, that significant context makes clear that his Honour’s criticism at [442] that the Commission’s case lacked ‘precision and clarity’ provides no support for the Commission’s submission.

54 The Commission also submitted that the trial judge had placed significance on the fact that there was little or no evidence that Cussons was a party to the alleged arrangement or understanding or that it had communicated a commitment or assurance to the other Suppliers. The Commission particularly drew the Court’s attention to [483]-[485] as an example of this:

Direct communications between Cussons and the other Suppliers

483 The evidence revealed that there were very few direct communications between Cussons and the other Suppliers. In fact there were only seven. They were: Mr Fatouros’ attendance at the 30 April 2008 Accord meeting; Mr Fatouros’ 23 July 2008 reply email to Ms Capanna of Accord, which was copied to Ms Moss of Unilever and officers of Colgate, amongst others; Mr Basha’s telephone call to Ms Gill on 19 August 2008; Mr Campbell’s telephone call to Mr Courtier on 21 August 2008; Mr Davey’s attendance at the Accord meetings on 25 August and 10 October 2008; and Mr Fatouros’ telephone call to Mr Pederson of Colgate in October 2008.

484 The evidence concerning each of those direct communications has already been discussed in some detail. It suffices to say that, when considered in context and as part of the whole of the evidence, those direct communications do not significantly advance the Commission’s case. Indeed, in most respects, they are contrary to it.

Communications between Cussons and Woolworths

485 The limited direct communications, both in terms of number and significance, between Cussons and the other Suppliers perhaps explains why the Commission’s case, as ultimately articulated, placed considerable emphasis on the role played by Woolworths. Before considering the Commission’s arguments concerning “hub and spoke” and vertical and horizontal arrangements, it is necessary to say something briefly about the communications between Cussons and Woolworths.

55 Whilst the Commission accepted that the trial judge had not said that there needed to be direct evidence, it contended that these passages nevertheless demonstrated that his Honour had been looking for a degree of certainty ‘that one would expect in a contract’. We reject this submission. The trial judge’s reasons do not say this. There is a difference between commenting on obvious weaknesses in the Commission’s case as advanced and demanding a contractual level of certainty. The Commission’s submission entails misreading the trial judge’s reasons.

Did the trial judge inappropriately refer to the absence of commitment?

56 The Commission submitted that the trial judge’s treatment of the issue of ‘war-gaming’ showed that he had applied an inappropriately high standard of proof for an arrangement or understanding. The reference to ‘war-gaming’ first requires explanation. As mentioned earlier in these reasons, on 21 October 2008 Cussons conducted what it called a war-gaming session with those of its employees involved in the transition to ultra-concentrates. The trial judge accepted that the purpose of the session was to brainstorm a range of different scenarios relating to how Cussons would compete and how its competitors might respond when ultra-concentrates were launched. What the trial judge drew from this was that the war-gaming exercise was inconsistent with the idea that Cussons had reached an arrangement or understanding with the other Suppliers on these issues. It was legitimate for his Honour to reason that if such an arrangement or understanding existed, this process of strategizing was, on the evidence, unnecessary. At [349] his Honour said:

The evidence concerning this war gaming exercise is quite inconsistent with Cussons being a party to any arrangement or understanding with Colgate and Unilever concerning the transition to ultra concentrates. Had there been any arrangement or understanding of the type alleged by the Commission, those war gaming sessions would have been completely unnecessary. It would in those circumstances have been unnecessary for Cussons to speculate or try to work out what its competitors were likely to do or not do and how it should react to various different scenarios. Unless those war gaming sessions were some sort of elaborate ruse, they are wholly inconsistent with the inferences that the Commission says should be drawn.

57 The Commission submitted that this overlooked the possibility that the Suppliers had reached the alleged arrangement and that the war-gaming activity was directed to how Cussons would react if one of the other Suppliers cheated on the arrangement. We reject this submission. The trial judge explicitly considered this issue at [350] and rejected it as a matter of fact:

The Commission submitted that the war gaming sessions were not inconsistent with the existence of an arrangement or understanding because they concerned what Cussons would do if its competitors cheated on the arrangement or understanding that had been reached or arrived at. There are at least two fundamental problems with that submission. First, it is inconsistent with the evidence concerning those sessions, both documentary and testimonial. There is no hint in the evidence that those sessions concerned the possibility of Cussons’ competitors cheating on an arrangement or understanding. Second, this supposed cheating scenario was never put to any of Cussons’ witnesses in cross-examination.

58 The Commission does not seek to appeal from this finding. That being so, the trial judge was entitled to conclude that the war-gaming evidence was inconsistent with the existence of the alleged arrangement or understanding. It is not to the point in the present context that the fact in a given case that a party is free to cheat on a cartel does not negative the existence of a collusive understanding. The trial judge rejected that proposition on the facts at [350].

59 Both in writing and at the appeal hearing, the Commission pursued a variant of this argument. It submitted that in his treatment of the war-gaming issue his Honour had searched for the kind of irrevocable commitment which was not consistent with the nature of an arrangement. There is no such inconsistency. Once consideration of the possibility of cheating by the other Suppliers was removed on the facts as found, this evidence was inconsistent with the Commission’s case. In observing as much, the trial judge did not impose an obligation on the Commission to show the existence of an irrevocable commitment. The Commission took the Court to no part of the trial judge’s reasons where his Honour had said that such an obligation existed. In fact, the trial judge’s reasons establish that his Honour did not require the Commission to prove the existence of the irrevocable commitment about which it now complains. At [425] his Honour observed that the evidence did not establish that ‘Cussons considered it had any commitment, obligation or moral or legal duty to the other Suppliers in respect of the transition’. This is not the language of irrevocable commitment.

Did the trial judge err in thinking that the negativing of knowledge or intention on Cussons’ part negatived the existence of the arrangement or understanding?

60 The Commission submitted that on a number of occasions the trial judge had observed that the evidence did not establish that Cussons ‘knew’ or ‘intended’ that its statements at Accord meetings (or also to Woolworths) were for the purpose of signalling to the other Suppliers. The Commission did not identify in its written submission what the trial judge did with this conclusion. Instead, it submitted that the reasoning ‘appeared’ to reflect certain statements made by Lord Diplock in Re British Slag Ltd’s Agreements [1963] 2 All ER 807 (‘Re British Slag’) at 819. That passage concerned the circumstances in which a horizontal arrangement might be inferred from vertical arrangements. Lord Diplock said this:

… it is sufficient to constitute an “arrangement” between A and B, if (i) A makes a representation as to his future conduct with the expectation and intention that such conduct on his part will operate as an inducement to B to act in a particular way; (ii) such representation is communicated to B, who has knowledge that A so expected and intended, and (iii) such representation or A’s conduct in fulfilment of it operates as an inducement, whether among other inducements or not, to B to act in that particular way.

61 The Commission identified the error by the trial judge as being in treating this statement as imposing as a necessary condition for the finding of an arrangement proof of knowledge or intention, whereas Lord Diplock’s statement was a statement of a sufficient condition and was otherwise merely ‘illustrative’ rather than exhaustive. The logic of this was that the trial judge had concluded that there was no arrangement or understanding because it was not shown that Cussons knew or intended that its statement at Accord meetings (and to Woolworths) were for the purposes of signalling. However, so the Commission submitted, that finding did not require such a conclusion—it was merely the negativing of a sufficient condition, not a necessary condition. In other words, an arrangement or understanding was not ruled out merely because it was found that there had been no intention to signal to the other Suppliers.

62 This argument should be rejected. It was the Commission’s case at trial that the Suppliers had attempted to use first Accord and then Woolworths as a hub for their communications. The trial judge recorded the submission as follows:

492 The more important issue, in terms of the Commission’s case against Cussons, is the state of mind and intentions of the Cussons officers when they met with Woolworths to discuss Cussons’ plans for transitioning to ultra concentrates. Did they know or intend that the information they provided to Woolworths about their plans would be conveyed to Colgate and Unilever? When Mr Fuchs conveyed to them his understanding of what Colgate and Unilever were doing in relation to the transition, did the Cussons officers know or believe that this was somehow being done with the tacit, or perhaps even express, consent or approval of Colgate and Unilever? Did they know or believe that Woolworths was somehow being used as a “hub” through which the Suppliers could exchange information for the purposes, ultimately, of reaching an arrangement or understanding concerning the transition?

493 The Commission’s case, as ultimately articulated in its submissions, appeared to proceed on the basis that the answer to those questions was “yes”. While not expressly pleaded, that appeared to be the basis of its submissions concerning the “hub and spoke” type arrangement. The Commission submitted that, at least after the abandonment of the Accord process, Cussons and the other Suppliers knowingly and intentionally exchanged information through their meetings and communications with Woolworths.

494 The evidence, however, does not sustain any such findings. There is certainly no direct evidence that the relevant Cussons officers knew or intended that the information that they provided to Mr Fuchs would be conveyed to the other Suppliers by Mr Fuchs, or that they believed or understood that the information that Mr Fuchs conveyed to them about Colgate and Unilever’s plans was provided with the consent or approval of Colgate and Unilever. Nor does the evidence as a whole reasonably permit or support the drawing of any such inferences.

63 The trial judge was therefore required to deal with the Commission’s submission that the conduct had been intentional. This is what his Honour did at [494]. When [494] is read straight after [492] it becomes apparent that this Honour was responding to a case advanced by the Commission. The same point may be made about [514]-[525] where his Honour rejected the Commission’s argument based on Re British Slag. It was therefore the Commission which had argued that the arrangement might be inferred from the fact that Cussons knew and intended to communicate through Accord and then Woolworths. No error is shown by the trial judge rejecting this argument on the facts by finding that there was no intentional aspect to Cussons’ behaviour. The Commission may be correct that intention is a sufficient but not a necessary condition for establishing an arrangement—we need not proffer a view—but what the trial judge did was to reject the Commission’s case that it had established the sufficient condition. He did not in so doing erroneously require proof of knowledge or intention.

64 At the hearing the Commission pursued a variant of this argument. It submitted that the more probable inference from the evidence was that the officers and employees of Cussons knew and expected that the information they provided to Woolworths was being fed back to their competitors. However, we discern no error in the trial judge’s approach which would permit this Court to come to its own view on the matter.

Did the trial judge err in his treatment of vertical arrangements?

65 The Commission submitted that the trial judge had erroneously distinguished the Full Court’s decision in the News Ltd v Australian Rugby Football League Ltd [1996] FCA 870; 64 FCR 410 (‘Super League case’) because he had not considered whether the vertical arrangements between each Supplier and Woolworths only made sense if they were engaging in them as ‘a common undertaking’ with the other Suppliers. The relevant part of the trial judge’s reasons is at [530]:

In this matter, even accepting, for present purposes, that each of Cussons, Unilever and Colgate entered into vertical arrangements of some sort with Woolworths, the question is whether the evidence concerning the dealings between Cussons, Unilever, Colgate and Woolworths in relation to those vertical arrangements supports the inference that Cussons also entered into a horizontal arrangement with either or both of Unilever and Colgate in similar terms to the vertical arrangements, or a horizontal arrangement that it would enter into the same vertical arrangements as the other Suppliers had entered into with Woolworths. For the reasons that have effectively already been given, when the whole of the evidence is considered, the answer to that question is “no”: the evidence does not support the drawing of such an inference.

66 In the Super League case the Full Court concluded that a horizontal arrangement could be inferred on the facts, specifically the fact that all of the clubs had met in November 1994. What the trial judge in this case did at [530] was to refuse to draw the inference that a horizontal arrangement existed and distinguished the present case on its facts. The Commission’s suggestion that the trial judge erred by failing to consider whether the vertical arrangements only made sense as a common understanding is, in truth, not an error of principle but an invitation to depart from his finding of fact at [530], without demonstrating error. His Honour also considered whether the vertical arrangements made sense without a common understanding between the suppliers, and found that it did: [126], [398]-[408], [532]-[538].

67 We therefore reject Ground 1.

68 Section A of the Amended Notice of Appeal also included Grounds 2 and 3. In the event that error was shown under Ground 1, Ground 2 sought to establish what the trial judge should have done in approaching the issue of whether an arrangement or understanding was demonstrated and Ground 3 set out the particular findings the Commission sought on that assumption. Since no error is established under Ground 1, Grounds 2 and 3 do not arise.

SECTION B: CONSCIOUS PARALLELISM VERSUS AN ARRANGEMENT OR UNDERSTANDING

69 As mentioned at the outset of these reasons, the Suppliers all transitioned to ultra-concentrates at approximately the same time which may be described as parallel conduct. Parallel conduct is often enough consistent with there being an arrangement or understanding, but by itself is not usually thought to be sufficient to prove such conduct in ordinary markets: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited [2014] FCA 1157; 319 ALR 388 at 490-491 [474] per Perram J. The Commission submitted that the parallelism which had occurred assisted its case that there was an arrangement or understanding. His Honour rejected this at [592] in these terms:

In short, any parallel conduct was explicable on grounds that had nothing to do with any arrangement or understanding.

70 The Commission submitted that that paragraph shows that his Honour had asked himself the wrong question. It submitted that his Honour should have asked himself whether the more probable inference arising from the parallel conduct was the existence of the Withhold Supply Arrangement. Instead his Honour asked himself whether the parallel conduct ‘was explicable on grounds that had nothing to do with any arrangement or understanding’. This argument was the subject matter of Ground 4.

71 The Commission’s submission hinges on the word ‘explicable’ which, literally, means capable of being explained. However, it is clear in the context of [592] that his Honour was not suggesting that the parallel conduct was capable of being explained on other innocent bases; rather, he was saying that it was explained on those bases. One can see that from the trial judge’s introductory statement at [589] that:

The problem for the Commission is that its submissions concerning the circumstantial significance of the parallel conduct that it asserts occurred in this case are not supported by its own economic evidence, and are significantly undermined by the unchallenged evidence adduced by Cussons.

72 The trial judge then proceeded to explain in detail what those problems were. The first was that the Commission’s expert economic evidence did not support its case. Professor Williams, who gave evidence on behalf of the Commission, said only that the parallel conduct would not have occurred if the parties had behaved unilaterally. The second was that there was other expert economic evidence given by Professor Hay for Cussons that the parallel conduct would have occurred without any arrangement or understanding being present and was explicable on other economic grounds. The other economic grounds were the absence of any economic incentive for an individual Supplier to delay the introduction of ultra-concentrates and thereby forego economic benefits such as reduced costs and higher margins; the retailers’ strong incentives to require a prompt and simultaneous transition by all Suppliers; and the retailers’ structured range review process. The trial judge observed that the Commission had not tested any of this evidence under cross-examination and then noted at [592] that the evidence ‘significantly undermined the Commission’s submission that the asserted parallel conduct supported the inference of the existence of an arrangement or understanding between Cussons, Unilever and Colgate’.

73 Once those conclusions are brought to account it can be seen that [592] does not involve the trial judge asking himself the wrong question. It involves instead his Honour considering the probative significance of the parallel conduct and subsequent rejection of the Commission’s case on the facts. His Honour found the parallel behaviour was explained by the other matters to which he had referred and not by the existence of an arrangement or understanding.

74 The Commission also developed this argument in a more nuanced form. It submitted that his Honour should have asked whether it was the more probable inference that the parallel conduct was explained by the existence of the Withhold Supply Arrangement on the Commission’s circumstantial case. Where the trial judge had gone wrong at [592], according to the Commission, was in asking whether there was a reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence (i.e. with the non-existence of the alleged arrangement). However, this submission fails for the same reason. Paragraph 592 does not say that the arrangement was rejected because there was a reasonable hypothesis consistent with its non-existence. Read alongside the paragraphs which precede it, the paragraph only says that the arrangement was rejected because the parallel conduct was explained by the evidence to which we have referred above. There was no hypothesis involved. There was, therefore, no error in the way in which the trial judge treated the topic of parallelism.

75 By Ground 5 the Commission invited the Court to conclude that the Withhold Supply Arrangement had been reached. However, this ground would only arise in the event that Ground 4 were made out which has not occurred. There is no occasion for this Court to embark upon its own fact finding when no error has been established.

SECTION C: THE ROLE OF WOOLWORTHS AND COLES

76 By Ground 6 the Commission contended that the trial judge had erred in law by finding that: (a) Woolworths and Coles had driven the timing and scope of the transition; and, (b) that once Colgate, Cussons and Unilever began supplying ultra-concentrates, Woolworths and Coles would cease to stock standard concentrates on their shelves. In its written submissions, proposition (b) was not pursued and may be put aside. Proposition (a) involves a challenge to the trial judge’s finding of fact. The Commission pursued its argument along five lines:

77 The first related to [125]:

Mr Basha understood that if a manufacturer, such as Unilever, wanted to make a large category change, such as changing its whole range of products to ultra concentrates, it would have to meet the retailers’ timetable. He also understood that if the manufacturer did not meet the retailers’ timetable for a major review, then it would “miss the boat until the following year”. He did not come across anybody in Unilever at the time that had a different understanding or expectation in relation to major reviews.

78 The Commission submitted that at this paragraph the trial judge ‘had observed that if a supplier wanted to make a large category change, it had to meet the retailer’s timetable because if it did not it would “miss the boat until next year”’. It submitted that this evidence contradicted the finding that Woolworths and Coles had driven the timing and scope of the transition. This was because the finding ‘reinforced why it was critical for the Suppliers to arrive at an arrangement or understanding’. Why? Because if they did not and one of the them ‘missed the boat’, it would mean that Suppliers who had transitioned would be left selling ultra-concentrates for months while another Supplier’s standard concentrates remained on the shelves.

79 This is a question of what inference should be drawn from a fact. The inference identified by the Commission is probably open but it has failed to establish in any way that the inference drawn by the trial judge was drawn in error which is an essential first step: Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs v Hamsher [1992] FCA 233; 35 FCR 359 at 369 per Beaumont and Lee JJ.

80 The second contention related to [379]-[380] where it was said:

In late 2009, Unilever and Woolworths produced a video concerning the introduction of ultra concentrated laundry detergents. Mr McNeil, Mr James Frost (Brand Director in relation to laundry detergents, based in Europe) and Mr Neil Robertson (Operations Manager in New Zealand) of Unilever appeared in the video, as did Mr Fuchs of Woolworths. The Commission relied on the fact that Mr McNeil and Mr Fuchs made the following statements in the video:

Mr McNeil said: “But it was their role in getting all of the players in the industry to move simultaneously. That really made the biggest difference of all.”

Mr Fuchs said: “This was really important. I think firstly because we didn’t want any confusion with the customers, we wanted everything to change over at the same time. Also from a cost point of view that we did one layout and we didn’t have to continuously change.”

The Commission did not call Mr Fuchs. Cussons did not object to the admission of Mr Fuchs’ statement as evidence of the truth of the assertions made in it. The statement tends to confirm that it was Woolworths that drove the timing of the transition, in part for its own commercial purposes, but also because it did not want its customers to be confused.

81 The Commission submitted that the words in the quote in [379] (‘it was their role in getting all of the players in the industry to move simultaneously’) did not justify the conclusion in [380] that this evidence tended to confirm that it was Woolworths which drove the timing of the transition. This was put on two bases: first, as a self-evident proposition; and secondly, to be particularly so when regard was had to the fact that the Suppliers had individually proposed and persuaded Woolworths to play that role in the first place.

82 We reject both submissions. The Commission pointed to no error in the process of drawing the inference which would enliven our jurisdiction nor do we think this is a case where we had such a clear difference of opinion on the matter from that of the trial judge that would could infer that an error must have been made.

83 The Commission’s third argument related to [532]-[536] at which the trial judge concluded that the timing of the transition was driven by Woolworths’ expressed preferences determined by its own commercial interests. This was submitted by the Commission to ‘neglect’ the fact that the Suppliers effectively arranged for the transition to be delayed from January 2009 to March 2009 to accommodate Unilever’s production capability. However, the trial judge found at [262] that there was no evidence that Cussons was involved in any of these communications. That finding is not challenged.

84 The fourth contention related to [630]:

It may readily be accepted that Woolworths and Coles were not in a position to dictate to Cussons or the other Suppliers what products they were or were not to manufacture. That proposition was put to and accepted by some of the Cussons witnesses in cross-examination. That is, however, not to the point. Cussons and the other Suppliers were no doubt free to continue to manufacture standard concentrates and supply those products to anyone who wished to purchase them. There was, however, little point continuing to manufacture standard concentrates if the major supermarket retailers did not want to buy them. Woolworths and Coles plainly had the power to decide that they did not wish to continue to purchase any particular product manufactured by the Suppliers, including standard concentrates. What they purchased and put on their shelves for sale to consumers was entirely a matter for them.

85 It was said that this paragraph and the reasoning from [624]-[632] suffered from a degree of artificiality. The point was that the trial judge had, on the one hand, said that Woolworths and Coles were not in a position to dictate what products the Suppliers manufactured but, on the other, had also said that the retailers had the power to decide that they did not wish to continue to purchase any particular products. It was submitted that these statements were inconsistent. In our opinion, this submission is based on a flawed reading of [630] which does no more than describe the commercial reality as between the manufacturer/supplier and the retailer.

86 Resort to the text of [630] shows that the trial judge was saying that the evidence of the Cussons’ witnesses that Woolworths and Coles could not dictate what they manufactured was ‘not to the point’ because there was little point in continuing to manufacture the products if the retailers were not going to stock them. That statement demonstrates that his Honour was aware of the potential inconsistency between the two stances and resolved it by saying that the retailer had the final say as to what is stocked and sold. We reject the submission.