FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Manado on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2018] FCAFC 238

ORDERS

WAD 216 of 2018 | |

| |

BETWEEN: | RITA AUGUSTINE, ELIZABETH DIXON, CECILIA DJIAGWEEN, IGNATIUS PADDY AND ANTHONY WATSON ON BEHALF OF THE JABIRR JABIRR/NGUMBARL NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP Appellant |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Second Respondent SHIRE OF BROOME (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent |

WAD 217 of 2018 | |

BETWEEN: | JR (DECEASED), BRIAN JOHN COUNCILLOR, TERRENCE HUNTER, JASON DAVID ROE AND RONALD LESLIE ROE ON BEHALF OF THE GOOLARABOOLOO NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP Appellant |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent RITA AUGUSTINE, ELIZABETH DIXON, CECILIA DJIAGWEEN, IGNATIUS PADDY AND ANTHONY WATSON ON BEHALF OF THE JABIRR JABIRR/NGUMBARL NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP Second Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent |

JUDGES: | BARKER, PERRY AND CHARLESWORTH JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 december 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Schedule 7, item 12(f) of the determination of native title made in proceeding WAD359/2013 on 2 May 2018 be set aside.

3. The appellant to prepare a minute of proposed amended determination in accordance with the reasons of the Court.

In WAD216/2018:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Schedule 6, item 8(h) of the determination of native title made in proceeding WAD357/2013 on 2 May 2018 be set aside.

3. The appellant to prepare a minute of proposed amended determination in accordance with the reasons of the Court.

In WAD217/2018:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

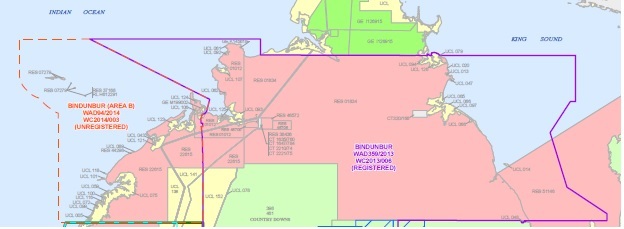

1 On 2 May 2018, at Beagle Bay near Broome, a judge of the Court made two determinations of native title, namely:

(1) a determination in favour of the Bindunbur native title claim group in WAD359/2013 (the Bindunbur determination); and

(2) a determination in favour of the Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl native title claim group in WAD357/2013 (the Jabirr Jabirr determination).

See Manado (on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group) v State of Western Australia [2018] FCA 854.

2 The determinations gave effect to the reasons for judgment of the judge in Manado (on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group) v State of Western Australia [2017] FCA 1367 delivered 23 November 2017 (primary judgment) and Manado (on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group) v State of Western Australia [2018] FCA 275 delivered on 8 March 2018 (supplementary judgment).

3 A consequence of the Jabirr Jabirr determination was that the claimant application of the Goolarabooloo native title claim group in WAD374/2013 was dismissed.

4 Amongst other issues decided by the primary judge, his Honour found that:

(1) rights or interests arising from a rayi connection held by a Goolarabooloo person; and

(2) rights and interest held by Goolarabooloo people who are acknowledged as ritual leaders in the Jabirr Jabirr determination area;

were not native title rights and interests for the purposes of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA).

5 Also, in each determination, under the category of “Other Interests”, the primary judge included the “interest” of public access to and enjoyment of waterways, beds and banks or foreshores of waterways, coastal waters and beaches.

6 This judgment concerns appeals from these particular findings and parts of the determinations, namely:

(1) the Goolarabooloo appeal from the findings of the primary judge that the persons holding a rayi connection within the Jabirr Jabirr determination area or who are ritual leaders in relation to the Jabirr Jabirr native title determination area do not possess native title rights or interests as defined by the NTA; and

(2) the Bindunbur and the Jabirr Jabirr respectively appeal from the determination of public access to and enjoyment of the places mentioned above as an other interest in the Bindunbur determination and the Jabirr Jabirr determination.

7 We will deal first with the Goolarabooloo appeal and then with the appeals of the Bindunbur and the Jabirr Jabirr.

8 For the reasons given below, the Goolarabooloo appeal should be dismissed but the appeals of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr should be allowed.

2. The Goolarabooloo appeal (WAD217/2018)

2.1 The primary judge’s findings with respect to the claimed rights and interests said to arise from a rayi connection

9 The definition of “native title” in s 223(1) of the NTA is pivotal in that it defines the scope of rights and interests recognised and protected by the NTA. Section 223(1) provides that:

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

10 The High Court has held that the native title rights and interests which are recognised and protected by the NTA as defined in s 223(1) are those which were held to have survived the acquisition of sovereignty in Mabo and Others v The State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1; [1992] HCA 23: see The State of Western Australia v The Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case) (1995) CLR 373 at 452-453 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ); [1995] HCA 47; Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria and Others (2002) 214 CLR 422 at [45] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ) at [134] (McHugh J); [2002] HCA 58. Section 225 of the NTA in turn requires that a determination of native title must determine whether native title exists and if so, who holds it and the nature of the native title rights and interests. Specifically, s 225 provides that:

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease—whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Note: The determination may deal with the matters in paragraphs (c) and (d) by referring to a particular kind or particular kinds of non-native title interests.

11 A determination is therefore declaratory of the native title rights and interests, and operates as a judgment in rem at least with respect to the native title rights which is therefore binding upon the whole world: Western Australia v Ward and Others (2000) 99 FCR 316 at [190]; [2000] FCA 191 (Beaumont and von Doussa JJ); Dale and Others v Western Australia and Others (2011) 191 FCR 521 at [92]; [2001] FCAFC 46. However, while it is unnecessary to determine in this case, the note to s 225 and extrinsic materials indicate that Parliament did not intend that the failure of a court to refer to an “other” (that is, non-native title) interest in a native title determination would have any effect upon that interest: Explanatory Memorandum, Native Title Amendment Bill 1997 (Cth) at [26.26].

12 The primary judge, at [440]-[442] and [497]-[500] of the primary judgment, found that rights arising from a rayi connection within the determination area are not native title rights and interests within the meaning of s 223 of the NTA.

13 At those paragraphs, the judge stated:

440 Beyond issues of descent and succession, an alternative basis for acquiring native title rights and interests was said by the Goolarabooloo applicants to be through having a rayi connection in the application areas. Broadly stated, rayi can be understood as a spiritual phenomenon that can lead to an attachment to a particular place or animal. More specifically, belief in rayi is described in the Professor Bagshaw’s primary report as ‘spiritual instantiation by means of localised (i.e. territorially-based) anthropomorphic or theriomorphic agents (spirits) called rayi’. An Aboriginal person may be recognised by Aboriginal society as ‘having’ a rayi, or spirit, from a particular place. This may be referred to as that person having a rayi connection to that place.

441 It was common ground that belief in rayi is a feature of the traditional laws and customs of the application areas. The evidence of Aboriginal witnesses from all parties was to the effect that belief in rayi continues in the application areas, and that various individuals, including witnesses in the present proceedings, are recognised as having a rayi connection to particular places in the application areas.

442 The dispute between the parties was whether a rayi connection, absent of any other connection, is sufficient to give rise to native title rights and interests, and if so, the scope of those rights and interests.

…

497 The positions regarding the nature and content of rights derived from rayi of the Goolarabooloo applicants on the one hand, and the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants on the other, were ultimately not very far apart. The Goolarabooloo applicants accepted that the rayi derived rights are subject to the views of those with descent-based rights. The evidence of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witnesses relied on by the Goolarabooloo applicants emphasised that a rayi connection holder could not ‘speak for’ the country, but rather, had to seek permission from the descent-based owners to access and use the area associated with the rayi event. The evidence was that in the ordinary course of things, that permission would not be denied. However, in the unlikely event of serious wrongdoing by a rayi connection holder, that permission could be rescinded. When pressed on the matter, the Goolarabooloo applicants’ expert witness, Professor Cane, conceded that the descent-based owners would have the final say if there were a dispute with a rayi connection holder.

498 The difference between the parties was confined to whether those facts gave rise to native title rights or interests. In that respect, the difficulty faced by the Goolarabooloo applicants is that even though permission is not ordinarily denied, the very fact that permission must be sought is indicative of the rayi connection holder entering into a relationship with the rights holders by descent. That relationship is characterised by mutual respect. The rights holders by descent ‘wouldn’t say no’ to the rayi connection holder, but in the event of wrongful behaviour, the rayi connection holder may be excluded. Professor Cane’s characterisation of how rayi rights might be articulated, namely, ‘if you kill that barramundi, you kill me,’ further indicates that the rayi connection holder has a personal relationship with the rights holders by descent, who become responsible for the spiritual well-being of the former. The rayi connection holder therefore cannot engage in activity in the rayi event area without entering into this relationship of mutual respect with the rights holders by descent, and in that sense, any rayi derived rights are contingent upon the ‘core’ rights of the rights holders by descent. Thus, rayi derived rights are rights in relation to persons, not land or waters.

499 That is not to say that a rayi connection has no utility or purpose under the traditional laws and customs of the society in the application areas. As Professor Cane acknowledged, a rayi connection in someone else’s country can become a political vehicle. But as Professor Sutton observed, it would not have been in the wisdom of the old people to have allowed for chaos. Rather, because a rayi connection is subject to social recognition, it may be regarded as a tool for the social inclusion of strangers on country. A socially recognised rayi connection allows a stranger to country to enter into a relationship of mutual respect with the rights holders by descent. In fact, that point was made by counsel for the Goolarabooloo applicants, who said during final submissions that ‘rayi can provide a basis for a significant level of social inclusion, which we describe in another way as respect in a local group’. The Goolarabooloo applicants further contended that there was strong evidence of social acceptance of Ms Teresa Roe and her sister, now deceased, by reason of their rayi. So much was not disputed by the other parties.

500 Regardless of the social utility or otherwise of the traditional belief in rayi, it is sufficient for present purposes to observe that it follows from the above reasoning that any rights derived from rayi are not native title rights and interests.

2.2 The primary judge’s findings with respect to the claimed rights and interests said to be held by ritual leaders

14 The primary judge also found, at [501]-[502], [576]-[579] and [586] of the primary judgment, that the functions and rights of persons who are ritual leaders holding mythical and ritual knowledge and experience under the Northern Tradition in relation to areas or places within the Jabirr Jabirr determination area are not native title rights or interests within the meaning of s 223 of the NTA.

15 In those paragraphs, the primary judge stated:

501 The Goolarabooloo applicants’ case is that a person who holds mythical or ritual knowledge and experience of an area and is responsible for places, areas and things of a mythological or ritual significance in the area, particularly those places, areas and things relating to the ritual practice and associated laws and customs, referred to as the Northern Tradition, holds rights and interests in that area. The Goolarabooloo Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions specifies the song cycle path along the coast of the Goolarabooloo application area from near Bindingankun to Willie Creek as an area for which men initiated in the Northern Tradition have a responsibility to look after, care for, protect and maintain. That responsibility is shared according to the man’s ritual or mythical knowledge and experience, his personal knowledge of the area, and as between law grounds on the one hand, and other places, areas and things of mythological or ritual significance in the area, on the other. Under traditional laws and customs acknowledged by the people of the region, the Law bosses, Mr Richard Hunter, Mr Phillip Roe and Mr Daniel Roe, primarily speak for, make decisions about matters affecting, and are primarily responsible for looking after, caring for, protecting and maintaining the song cycle path.

502 The draft determination proposed by the Goolarabooloo applicants adds a further qualification, namely, recognition by others of that knowledge and experience. In relation to the issue now under consideration the native title holders are defined in that draft determination to include living Aboriginals who:

[H]old mythical or ritual knowledge and experience of the Determination Area, and who are responsible for places, areas and things of mythological or ritual significance in the Determination Area and who are recognised by other native title holders under their relevant traditional laws and customs as having native title in the Determination Area.

…

576 The evidence of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr Aboriginal witnesses could not have been clearer. As one they said that under traditional laws and customs Law status does not give rights in land. Law men and women are highly regarded for the knowledge of the Law. That knowledge is mainly reflected in their role in the conduct of ceremony and, particularly in the male initiation ceremony. Their activities in relation to land mainly concern the responsibility to care for Law grounds where ceremony is conducted, and for other sites of sacred significance. Those sites are within the estates held by the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr people solely on the basis of descent, subject only to the limited exceptions in the case of child adoption and succession. If an issue arises on such sites the estate holders may seek advice from Law men. Law men act collectively in giving such advice. They are consulted by the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr people for their knowledge of the Northern Tradition. The authority of the Law men is respected. That authority is limited to the Law grounds and other sacred places. It does not extend to the whole of the application areas. In practice the advice of the Law men will be followed by the estate holders. But the estate holders have the final say. They cannot be told what to do by the Law men. The status of Law men and women is acquired by personal achievement. It is not handed down from other Law men and women.

577 It is significant that Mr P Sampi described the role of Law men in the same terms. He was the most senior Law man when he gave that evidence. He was clear that having responsibility for significant places ‘doesn’t make you an owner of that area’. It is also significant that he, as the most senior Law man in the Northern Tradition, made no claim in this proceeding for rights in the land in the application area. Similarly, no other Law man or woman, apart from the Goolarabooloo applicants, made any such claim. If ritual status or mythical knowledge allowed them to do so, one would have expected that they would have done so.

578 The evidence of the Goolarabooloo Aboriginal witnesses did not support the pleaded case. It may be that the evidence of Mr Phillip Roe extracted at [527] of these reasons for judgment can be read as a claim that knowledge of the Law gives rights in land. But, in view of his affidavit evidence extracted at [528] of these reasons for judgment it is probable that Mr Phillip Roe was not speaking of the acquisition of rights as an owner, but speaking of a responsibility to look after country. The other evidence of the Goolarabooloo Aboriginal witnesses was about what Law men were required to do rather than whether they held rights in the land. The role described was to take care of and protect the country. Insofar as the evidence relied on referred to the interaction with rights holders by descent, that evidence was that the Law bosses were called on for ‘advice of how we can protect it [the land] a lot better’. That evidence mirrored the evidence of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr Aboriginal witnesses.

579 The evidence of Mr Bagshaw, agreed to by Dr Weiner, Dr White and Professor Sutton, reflected the views of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr Aboriginal witnesses. Mr Bagshaw’s conclusion was that ritual status ‘does not in itself give rise to any proprietary right in country’. That is to say under traditional laws and customs the rights holders by descent have the final say about the use and care of the local estates. Ritual leaders who are not rights holders by descent require permission to access and use the land and do not have the final say in such matters. The ritual leaders are dependent on the permission of the rights holders by descent. The principles derived from the Akiba litigation discussed at [485] – [493] of these reasons for judgment apply equally to the position of the ritual leaders. Their advisory function and the rights accorded to them do not amount to native title rights and interests. They are not rights or interests in relation to the land.

…

586 That senior Bardi Law men have not claimed native title rights and interests over the application areas on the basis of their ritual knowledge may be explained by reference to certain assumptions those Bardi Law men may have about whether rights and interests that fall short of full ownership may constitute native title rights and interests. In any event, the nguril seating arrangements do not show that senior Law men have exclusive responsibility for particular geographic areas. At its highest, it may be said that the nguril seating arrangements represent the areas of greatest religious responsibility for each Law man. But, given the evidence to the effect that the senior Law men of the Northern Tradition work together in a collegiate system, regardless of territorial affiliation, it appears that at a certain level of generality, all Law men share responsibility for all sacred sites associated with the tradition. Thus, if it were the case that native title rights and interests in land were acquired through ritual and mythical knowledge, then it would follow that, contrary to the Goolarabooloo applicants’ pleaded case, all senior Law men initiated in the Northern Tradition would have native title rights.

2.3 The native title determination made below

16 As a consequence of the findings set out above, the primary judge relevantly made orders 1 and 2 in the Jabirr Jabirr application as follows:

1. Proceeding WAD374/2013 (the Goolarabooloo proceeding) be dismissed.

2. There be a determination of native title in the form attached as Attachment A to these orders.

17 Item 3 of Attachment A, identifies the common law native title holders as follows:

3. The rights and interests comprising the native title are held by Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people, being the people described in Schedule 3 (native title holders).

Schedule 3 identifies those holders in greater detail by reference to descendants of apical ancestors.

18 As a result of this formulation, the Jabirr Jabirr determination excluded from the native title holders identified in accordance with s 225 of the NTA, the Goolarabooloo native title claim group and Goolarabooloo persons who claimed a rayi connection within the Jabirr Jabirr determination area or interests arising by virtue of being ritual leaders with responsibilities in that area.

2.4 Grounds of the Goolarabooloo appeal

19 The Goolarabooloo appeal from orders 1 and 2 of the Jabirr Jabirr determination on the following grounds:

1. The learned primary judge erred in law, alternatively in law and fact, in:

(a) finding that rights arising from a rayi connection within the Determination Area are not native title rights or interests within the meaning of section 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Reasons [primary judgment] [440]-[442], [497]-[500]); and

(b) failing to find that persons who are accepted by the Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people as having a rayi connection within the Determination Area have native title rights or interests within the meaning of section 223 of the Native Title Act, and as such are:

(i) persons who, together with the Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people, hold the communal rights comprising the native title recognised in the Determination; alternatively

(ii) persons holding group rights which also comprise the native title in the Determination Area,

within the meaning of section 225(a) of the Native Title Act.

2. The learned primary judge erred in law, alternatively in law and fact, in:

(a) finding that the functions and rights of persons who are ritual leaders holding mythical and ritual knowledge and experience under the Northern Tradition in relation to areas or places within the Determination Area (Ritual Leaders) are not native title rights or interests within the meaning of section 223 of the Native Title Act (Reasons [primary judgment] [501]-[502], [576]-[579], [586]); and

(b) failing to find that Ritual Leaders have native title rights or interests within the meaning of section 223 of the Native Title Act, and as such are:

(i) persons who, together with the Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people, hold the communal rights comprising the native title recognised in the Determination; alternatively

(ii) persons holding group rights which also comprise the native title in the Determination Area,

within the meaning of section 225(a) of the Native Title Act.

20 The primary relief sought by the Goolarabooloo is that order 1 be set aside and the Jabirr Jabirr determination be varied as follows:

(a) In paragraph 3 by inserting after ‘Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people’ the words ‘and others’.

(b) In Schedule 3 by inserting:

‘Others

Aboriginal persons who:

(i) are accepted by the Jabirr Jabirr/Ngumbarl people as having a rayi connection within the Determination Area; or

(ii) are ritual leaders holding mythical and ritual knowledge and experience under the Northern Tradition in relation to areas or places within the Determination Area.’

21 The Goolarabooloo appeal is opposed by the State of Western Australia, the Jabirr Jabirr, and the Commonwealth, respectively the first, second and third respondents in WAD217/2018.

22 By a notice of contention filed in the Goolarabooloo appeal the Jabirr Jabirr additionally contend that the judge’s determination should be upheld on the following ground:

No rights or interests exist under the traditional laws and customs of the determination area that are carved out of or arise independently of those acquired by descent. Rather, those traditional laws and customs include rules about the manner in which those rights and interests are exercisable as against another person acknowledged by the persons possessing those rights and interests as having a rayi connection to a place in the determination area or as being a ritual leader in ceremony that concerns places in the determination area; namely that those rights and interests be exercised in a manner that affords respect for the rayi connection and the status of the ritual leader as the case may be.

2.6 Does a rayi holder possess native title rights or interests?

2.6.1 The submissions by the Goolarabooloo

23 The submissions made by the Goolarabooloo to the primary judge at trial, are in substance repeated on their behalf on this appeal.

24 The essence of the argument of the Goolarabooloo is encapsulated at [497] of the primary judgment, as set out at [13] above.

25 The Goolarabooloo, relying on evidence given by Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witnesses, contend that, for the purposes of s 223 of the NTA, a Goolarabooloo person with a rayi connection is possessed of a native title right to access and use an area of land or waters in Jabirr Jabirr country which is associated with a rayi event on the basis that:

(1) the right or interest is recognised by the law and custom of the Jabirr Jabirr;

(2) it is a right or interest by which the holder of that rayi connection relevantly maintains a connection with land or waters in the determination area; and, significantly,

(3) it is a right or interest “in relation to land or waters” for the purposes of s 223.

26 As such, the Goolarabooloo submit that the rights and interests held by a person with a rayi connection are distinguishable from the “reciprocal rights” which the High Court held were personal only and not in relation to land or waters for the purposes of the definition of native title in s 223: see Akiba v The Commonwealth of Australia (2013) 250 CLR 209; [2013] HCA 33 (Akiba HC).

27 In support of this submission, the Goolarabooloo rely in particular on the evidence of Ms Pat Torres, recorded at [463] of the primary judgment. When asked by counsel for the Goolarabooloo about the nature of rayi, Ms Torres concluded (in the passage recited in the primary judgment) that:

They [the person with rayi] can definitely speak up but traditional owners are the ones who make the final decision.

28 Emphasis is placed by the Goolarabooloo on the words “final decision”. They submitted that, properly understood, this indicates that the person with rayi has a right which may be exercised, albeit that those persons with other native title rights by “bloodline”/descent, may make the “final decision” if there is any question about access, enjoyment, or “speaking for country”.

29 Earlier in the passage recited by the primary judge, Ms Torres was also asked whether the rayi holder has a right to camp or take food from the rayi place. She indicated that they can camp but not live permanently there, and that they can take food. She added:

All of these rights are traditional owner bestowed rights, so if a TO says it's okay for them to camp there, they can take fish and food from there.

30 It should be understood that, in context, Ms Torres’ reference to “traditional owner” and “TO” is a reference to those holding native title in a place by bloodline/descent.

31 At the commencement of the passage recited by the primary judge, when Ms Torres initially explained about rayi, she said:

For me what I meant by that is that if something is happening to a country and a person has emotional connections through their rai, they have the right to be able to say, ‘Hey, everybody listen, this is a special place for me because I've got a rai from there’, so that's what I mean by that.

32 She agreed, in cross-examination, that the rayi is more than an “emotional connection” and constitutes a “spiritual connection” as well.

33 While the Goolarabooloo native title claim group is the appellant on the appeal, the issues raised about rayi are not raised in support of an argument that the Goolarabooloo, as a group, hold native title rights and/or interests of the same kind as the Jabirr Jabirr in the determination area. Rather, the appellant contends that some people who are Goolarabooloo hold individualised native title interests in relation to the determination area or a part or parts of that area because of the rayi connection they have with a part of the determination area, or because of their status as a ritual leader under the Northern Tradition.

34 Thus, if successful in their appeal, the Goolarabooloo submit that the Jabirr Jabirr determination should be amended to recognise that persons who have rayi connections or ritual status are also native title holders. If such amendments to the determination were appropriate, further consideration might be necessary to consider whether the determination should also be amended to specify precisely what place or places are the subject of such native title interests.

2.6.2 The nature of a rayi connection

35 Before proceeding further, however, it is appropriate to explain the nature of a rayi connection in more detail.

36 The nature of a rayi connection was principally explained in evidence by Mr Geoffrey Bagshaw, an anthropologist with considerable experience in relation to the determination area, who was called by the Jabirr Jabirr at trial. The primary judge relied on Mr Bagshaw’s evidence in a number of instances in his primary judgment, including in respect of his articulation of a rayi connection above.

37 For example, at [440] in the primary judgment set out above at [13], the primary judge, having earlier discounted the claims of the Goolarabooloo as a whole to hold native title in the determination area by virtue of the means of descent and/or succession, turned to the first alternative basis advanced by them for acquiring native title rights and interests, namely, through a rayi connection to the area. His Honour said that, broadly stated, rayi can be understood as a spiritual phenomenon that can lead to an attachment to a particular place or animal. It might be noted here that the judge did not say that rayi necessarily leads to an attachment to a particular place or animal, but only that it “can” do so. The judge added that, more specifically, belief in rayi is described in Mr Bagshaw’s primary report as “spiritual instantiation by means of localised (i.e. territorially-based) anthropomorphic or theriomorphic agents (spirits) called rayi”.

38 The primary judge added, at [440] of the primary judgment, that an Aboriginal person may be recognised by Aboriginal society as “having” a rayi, or spirit, from a particular place. He said that this “may be referred to” as that person having a “rayi connection” to that place. The concept of a “connection” needs to be considered carefully in this context to avoid possible confusion with the “connection” to which s 223(1)(b) refers.

39 The primary judge also found, at [441] of the primary judgment, that it was common ground that belief in rayi was a feature of the traditional laws and customs of the determination areas with which he was dealing.

2.6.3 The context in which the alternative case for the Goolarabooloo as to the rayi and ritual leader claims arose

40 It should be explained, however, that before the primary judge addressed the rayi connection question, he had, as noted above, dismissed the claims of the Goolarabooloo native title claim group as a whole to hold native title rights more generally in the determination area on the basis of descent and/or succession. It is helpful to understand exactly what the primary judge found in this regard in order to understand how the rayi connection proposition came to be separately considered and its significance.

41 In the result, the primary judge resolved what he described, at [251] of the primary judgment, as a “fundamental disagreement” between the Goolarabooloo and all of the other parties over the laws and customs concerning the acquisition of rights and interests in land, by upholding the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants’ claims.

42 As the primary judge explained at [252] of the primary judgment, the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants said that, under their traditional laws and customs and subject to rules about adoption and succession, rights and interests in land are acquired only by descent from a parent who possesses such rights in an unbroken bloodline back to and beyond the remembered past. That system allowed for the transmission of rights and interests to adopted children, but not to people adopted as adults. Further, the system provided for acquisition of rights in land by succession in extreme circumstances where a local landholding group became extinct because there were no remaining descendants. However, succession to rights and interests only occurred in favour of a group that was socially and geographically close to the extinct group. His Honour recounted both the evidence of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants and that of the expert anthropological witnesses in support of the conclusions he reached.

43 There is no challenge in this appeal to any of those findings.

44 So far as the expert evidence was concerned, the primary judge, at [282] of the primary judgment, said that the most comprehensive description of the way that land is and was held by the Jabirr Jabirr and Bindunbur applicants was provided by Dr James Weiner, who explained that land along the coastal areas was held by groups in local defined estate areas called “bur”. In the central area of the mid-Dampier Peninsula, the Pindan adjoining local estate holders held the right to country in common.

45 At [283] of the primary judgment, the judge noted Dr Weiner’s evidence concerning the bur, or the “family estate group”, and how its members are not strictly recruited through the male line, although recruitment to the estate of one’s father is still a normative rule today.

46 The primary judge also noted, at [284] of the primary judgment, what Dr Weiner stated in his supplementary report to the effect that his research indicated that “one cannot acquire rights to and authority over country by birth, acquisition of spiritual instantiation, long-term residence, or other non-patrifilial or non-cognatic means of attachment”.

47 The judge, at [285] of the primary judgment, also referred to Mr Bagshaw’s expert evidence on these latter questions, noting that Mr Bagshaw dealt with the question of descent more briefly because his remit was focused on the laws and customs relating to ritual practice and mythological knowledge. However, Mr Bagshaw also dealt with a population distributed among fairly small, localised and predominantly coastal territorial estates known as bur. Mr Bagshaw also referred to the distribution of rights by reference to the climatic circumstances of the territories. His Honour referred to Mr Bagshaw’s report in some detail, including passages that emphasised that while many, but certainly not all, people in the Beagle Bay region subscribed to an ideology of “patrilineal” descent as the principal determinant of traditional sociocultural identity and associated rights to country, in practice significant numbers of individuals cite diverse matrilateral (that is, traced through mother) and/or patrilateral (traced through father) descent connections as the basis for their own self-identification with a particular language group or “people” (for Jabirr Jabirr, Nyul Nyul, Nimanbur and others) and its traditional territory or parts thereof. His Honour noted that Mr Bagshaw also observed that it is not uncommon for persons to identify themselves or their close relatives as members of more than one such group.

48 The primary judge referred to, and emphasised in bold, a passage from Mr Bagshaw’s primary report (at [175]) to the following effect:

Additional factors such as marriage, co-residence and place of birth and/or spiritual conception were not in and of themselves generally regarded as sufficient conditions for personal identification of this kind, even though each one of these factors is often (but not invariably) indicative of close consanguineal relationships obtaining between particular individuals.

In short, therefore, it is widely held in this region that, for a person to validly identify with a particular language group and its traditional territorial domain (whether in part or whole), he/ she must be a recognised descendant of at least one individual who is (or was) so identified.

(Emphasis in primary judgment.)

49 The primary judge further noted, at [287] of the primary judgment, that in Mr Bagshaw’s supplementary report, he said of the proposed alternative methods of acquiring rights in land, that:

18. […] as much of the Bindunbur claimants’ evidence indicates, and my own research largely confirms, factors like extended residence, knowledge of Law and country, birth and rayi association are not recognised in the northern and central Dampier Peninsula as being sufficient in and of themselves to establish or create ownership rights – by which I mean unmediated, unconditional and heritable possessory rights – in country.

(Emphasis in primary judgment.)

2.6.4 Consideration by the primary judge of the rayi claim

50 Once the primary judge concluded that the Goolarabooloo did not have native title rights by descent or succession in the Jabirr Jabirr area, he turned to the question of whether, nonetheless, the rayi and the ritual leader claims, which as a matter of fact were not in dispute, constituted native title rights and interests for the purposes of s 223. We have already referred above to the evidence of Ms Torres, recounted by the primary judge at [463] of the primary judgment in this regard.

51 Ms Rita Augustine, on behalf of the Jabirr Jabirr, also gave evidence in chief about rayi. The primary judge recited her evidence at [456] and [457] of the primary judgment. Ms Augustine was asked in particular about Ms Teresa Roe’s rayi connection. Ms Roe was the only Goolarabooloo person identified by the evidence as having rayi.

52 As a general proposition Ms Augustine rejected the proposition that in the determination area, a person with rayi would be able to speak for the area or be a “traditional owner” of the area that their rayi came from, by virtue of having rayi alone. When asked whether Ms Roe, by reason of her rayi, could make decisions about the country from where it comes, Ms Augustine was, it must be said, diffident in her response. She answered (see [457] of the primary judgment):

Well, if she wanted to go out to that little area, whatever, maybe it's special to her.

53 She then agreed that the particular rayi place is special for Ms Roe. She indicated it would be “okay” for her to go up there camping or hunting or just to have a look and that she would not say “no to her”. She clarified that when she said “that little area”, she was just referring to that one place from where the rayi came.

54 The primary judge, at [458] of the primary judgment, also recounted the evidence of Ms Cissy Djiagween, in evidence in chief, who confirmed that the person who gets rayi from a place other than their mother’s or father’s place cannot claim the land as their own: “You can’t be boss over that country”.

55 Very clearly Ms Djiagween drew a distinction between “boss” over country and having a rayi. She explained:

Because you aren't looking for another mother; got to come through your blood.

56 At [459] of the primary judgment, Ms Djiagween’s further evidence in chief about Ms Roe’s rayi connection was noted as follows:

She can walk any time around there but she can’t talk for it.

…

But she’d have to ask the people, the Jabirr Jabirr people, you know, the people’s country.

57 When asked by counsel for the Bindunbur whether “suppose Teresa [Roe] went there and she did something wrong, can Jabirr Jabirr people for that area do anything about it?”, she answered:

Well, for sure they’d say, ‘Well, you can’t – you can’t make your own rules here. You’ve got to see the right people first.’

58 Ms Djiagween further indicated in re-examination that she could not think of anyone who had a rayi place somewhere outside their parents’ and grandparents’ country being accepted as a “traditional owner”.

59 The primary judge’s discussion at [498] and [499] of the primary judgment concerning what rayi is repays a close reading. His Honour well understood the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses, that the “rights holders by descent” would not “say no” to a rayi connection holder, although, in the event of wrongful behaviour, the rayi connection holder may be excluded from access and use of the rayi area. The primary judge concluded on the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses – and, in particular, on the evidence of the anthropologist Mr Bagshaw, that a rayi connection holder cannot engage in activity in the rayi event area without entering into a relationship of mutual respect with the rights holders by descent. In that sense, his Honour explained that “rayi derived rights” are contingent upon the “core” rights of the rights holders by descent. For that reason, his Honour explained, rayi derived rights are rights in relation to persons, not land or waters.

2.6.5 The primary judge’s finding rejecting the rayi connection as giving rise to native title should be upheld

60 We agree with the characterisation of the evidence given by the primary judge. As his Honour explained at [499] of the primary judgment, that is not to say that a rayi connection has no utility or purpose under the traditional laws and customs of the society in the determination area. It may become a “political vehicle”, as his Honour noted that Professor Scott Cane, who was called by the Goolarabooloo, had acknowledged. His Honour also made reference there to what Professor Peter Sutton, called by the State, observed, namely that a rayi connection is subject to social recognition. It may be regarded as a “tool for the social inclusion of strangers on country”. In that respect, a socially recognised rayi connection allows a stranger to country to enter into a relationship of mutual respect with the rights holders by descent. We agree, as his Honour plainly found, that such an interest – a socially recognised one – is not a right or interest in relation to land or waters for the purposes of s 223 of the NTA.

61 This is also consistent with the more detailed evidence that Mr Bagshaw gave in his discussion of rayi. First, we consider that rather than speak of a “rayi connection”, it is better to address the question of rayi in the manner that Mr Bagshaw did. He refers to it as a “rayi association”: see, for example, his supplementary report (anthropology) August 2016 at [19]. Mr Bagshaw acknowledged that factors such as residence, birth, and rayi association had the “potential” to give rise to some “limited, highly circumscribed, typically non-transmissible territorial rights and interests”, the granting and exercising of which are invariably mediated by and subject to the recognition of traditional owners – that is, the holders of rights through descent. Whilst Mr Bagshaw here, as an anthropologist, used the expression “territorial rights and interests”, it is plain that his more fully developed discussion of these rights treats them as being sourced in social relationships in the manner that the primary judge explained.

62 Mr Bagshaw, at [19], added:

Moreover, inasmuch as those rights and interests variously pertain only to matters of personal identification (in the case of rayi association), resource usage (in all cases), visitation (in all cases), or habitation (in the case of long-term residence), they have no intrinsic proprietary aspect and carry with them no powers of decision-making in relation to the places or areas involved.

63 Again, when taken in context, including the findings that people such as the Goolarabooloo claimants do not have any rights in the determination area as “traditional owners” by descent or succession, we understand the tenor of that evidence to mean that any rayi association interest is personal and provides no rights or interests “in relation to the land or waters” of the Jabirr Jabirr in this case. That is the plain meaning that Mr Bagshaw was attaching to the word “proprietary”.

64 In his supplementary report, Mr Bagshaw, at [112], also expressed the opinion that among the Jabirr Jabirr, rayi instantiation “in and of itself” does not traditionally confer any rights of control, representation (that is, speaking for country), or ownership in respect of the associated conception site or to any wider stretch of country incorporating that site. He noted that individuals, of course, enjoy such rights if their conception site is located within their existing bur or buru/local estate – such estates being owned and inherited on the basis of descent. Mr Bagshaw there went on to explain the significance of rayi association for a person who is not a rights holder by descent, as follows:

What it does confer, in my view, is the right to identify the relevant site (and its immediate environs) as one’s spiritual locus, the right to have one’s sentimental attachments thereto taken into consideration by the traditional owners in the course of making any decisions affecting the physical integrity of that site (but not to over-rule decisions made by the traditional owners [footnote omitted]) and the right – subject to the consent and acknowledgement of the relevant traditional owners – to access and enjoy the site and its natural resources (e.g. fruit, fish, game, etc.).

65 Mr Bagshaw then proceeded to further explain that consent and acknowledgement in this context necessarily presumed some awareness on the part of traditional owners of the individual in the circumstances concerned, as well as an acceptance of the cultural validity of that individual’s claim to site-based rayi instantiation at a location within the wider bur or buru.

66 The evidence given on behalf of the Goolarabooloo by Professor Cane, as observed by the primary judge at [484] and following, is also consistent with the understanding of a rayi association provided by Mr Bagshaw. After some discussion about the differences between the rights of a traditional owner by descent and that of a “rayi connection holder”, Professor Cane emphasised that a rayi connection must be socially recognised. He said:

I've written in my primary report that the rai, to the extent I understand it from the Desert perspective or as it expresses tjarrin, is - is - it has to be socially recognised because it's - it's just like an epiphany. It's an event you can't actually pin down and that's correct, and it does become a political vehicle because people can argue about it forever …

67 It is plain from the evidence taken as a whole, that it is not open to a person, such as Ms Roe, to assert of their own accord that they have a rayi association in Jabirr Jabirr territory. Rather, as Mr Bagshaw has explained, and indeed the evidence of Ms Torres referred to above confirms, whether or not a rayi association exists depends on whether a claimed rayi event is ultimately acknowledged and recognised by the “traditional owners”, being the Jabirr Jabirr people who are the rights holders by descent. As Ms Torres said, such a “right” is “bestowed” on a person by the traditional owners.

68 Properly understood therefore, as the primary judge explained, rayi might provide a person holding a rayi which is accepted by the traditional owners, with a relationship of mutual respect with the rights holders by descent. However, it does not constitute under the traditional law and custom of the Jabirr Jabirr people, a right or interest in relation to land or waters. Any freedom of access to, or use of, a rayi area is entirely at the discretion of the rights holders by descent. The fact that, by a complex social and religious relationship, the holder of a rayi interest (who has no descent based rights) may be free to access and use a place associated with the rayi, does not convert that socially recognised cultural relationship into one that can properly be characterised as a right or interest in relation to land or waters.

69 Each cultural setting will dictate how particular asserted and accepted rights and interests arising under the traditional laws and customs of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community are to be characterised. Here, the direct evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses, including Ms Torres, and the anthropological explication of a rayi association consistent with that direct evidence given by Mr Bagshaw, explains exactly why the primary judge concluded that the rayi association did not constitute a native title right or interest as defined by s 223 of the NTA.

70 The primary judge’s findings as to the nature of a rayi interest is also confirmed by the account as to the means by which Ms Roe came to have her rayi. The account provided at [444] of the primary judgment, was derived from the primary report of Professor Cane, the anthropologist called by the Goolarabooloo. It is appropriate to repeat it here in full:

The story of Ms Teresa Roe’s rayi connection was first told by her father, Mr P Roe. In his primary report, Professor Cane set out at Mr P Roe’s original account of the rayi event as follows:

114. … [Mr P Roe] described working with Mr and Mrs Douglas who had the small pig farm at Yellow River and fishing at Minarriny one morning. He describes an unusual encounter with a stingray,

[C]oming, coming he come straight for me I thought he gonna turn somewhere … but he come straight for me, straight, right up to my leg.

115. Paddy speared the stringray in the wing and then subsequently ate it, curried, with the Douglas’ [sic]. Paddy then felt the urge to leave, to head south. He and Mary camped on their walk south and heard the sound of crying babies on two occasions:

I listen again SAME thing again SAME thing again somebody coming crying just like you know ooh like a whistling but throat very you know like whistling like a baby crying.

116. They were disconcerted by the sound so they moved on. They collected bush honey, which flowed ubiquitously. The great amounts of honey also worried them, after which Paddy felt something ‘was given to us by somebody, – you know that – so we gone – we just pick up our honey and everything ooh’ and then left the area. They walk down the coast to a windmill and tank near Quondong Point and encountered two women: ‘two old women come out’. The women asked Paddy where he came from and he answered ‘I come from Minarriny… but proper I come from Roebuck Plain’. The women observe he was a long way from home. The women said they were ‘Djaberajaber people’. Next morning, near Quondong, Paddy’s wife felt sick and Paddy attributed the nausea to the honey they had collected earlier. One of the women thought differently:

That old women I said to you he’s a doctor too – Marban [traditional doctor and spiritualist]. Woman. [S]he told my old women, [s]he say ‘you got two rai’. From where he tell ‘em from Minarriny. You been pick up two girl, he tell ‘em two girl… ‘you got my two rai’… that’s the country woman that old fella old woman now, he from Minarriny that’s his country’.

117. When the first spirit child was born it was a girl, Theresa. So too the second child, Margaret. Theresa, was born with a mark on her arm in the same place Paddy had speared the stingray:

So when she was born my old women took notice you know. [S]He must think about that, you know the stingray I killed… and the girl got mark… got a hole in there. One side arm, right place too.

[Footnotes omitted.]

71 What is important to appreciate is that the Jabirr Jabirr women, as part of a well-understood cultural exchange, bestowed the rayi on Ms Roe, as Ms Torres explained the process of getting rayi. It is plain that the nature of that connection, association, or event is not one whereby any right or interest in relation to land or waters of the Jabirr Jabirr was created. Undoubtedly, there is a certain status that a person has as a rayi holder, but that status is conferred and plainly may be withdrawn by the Jabirr Jabirr people. The rayi holder is not admitted, even at some subtle level, to the group of people who hold native title rights and interests as defined in s 223 of the NTA.

72 In summary, it is plain from the s 223 definition of native title that native title or native title rights or interests may be individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, or rights and interests that inhere in a group or are held communally. However, by virtue of s 223(1), the relevant native title or rights and interests must be “in relation to land or waters”. Additionally, by para (a), the rights and interests, must be possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the relevant Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders. And finally, at least for present purposes, for those rights and interests to satisfy the definition, the relevant rights holders must, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters. However, for the reasons we have given above, the rayi association, while recognisable as an interest, if not as a right under Jabirr Jabirr traditional laws and customs, is an individual interest that might be bestowed on a person from outside the Jabirr Jabirr community by some people within the Jabirr Jabirr community, and is not in and of itself a right or interest in relation to land or waters.

73 Nothing in the authorities that have been cited to us by the Goolarabooloo indicates a different outcome. Each plainly depends on its particular facts and circumstances, including the particular laws and customs of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people concerned.

74 First, for example, in Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 141 FCR 457; [2005] FCA 50, Selway J had before him two sets of proceedings: one concerning the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (Land Rights Act); and the other concerning the NTA. The subject land and waters were related to those which had been the subject of Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd and The Commonwealth of Australia (Gove Land Rights Case) (1971) 17 FLR 141; [1972-73] ALR 65 and the Yolngu People. The essential issue though concerned Blue Mud Bay in North-East Arnhem Land.

75 While the proceedings under the Land Rights Act were dismissed, Selway J found that the applicants had a native title right of exclusive possession in land other than the inter-tidal zone; and as to the sea and the inter-tidal zone, the applicants had native title rights similar to those identified in The Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1; [2001] HCA 56.

76 In a lengthy judgment dealing, amongst other things, with the “elements of statutory native title”, Selway J considered a range of issues by reference to the anthropological evidence before him and the evidence of the Yolngu witnesses.

77 As may be appreciated from what has just been stated, an important question was whether native title rights were exclusive. At [206], Selway J found that the evidence of the Yolngu witnesses was clear and that permission to enter the land of the “clans” was required as a matter of traditional law. It was acknowledged by witnesses though that permission was usually assumed and, while withdrawal of it would be viewed as a significant break in friendly relations, it could nonetheless be withdrawn.

78 At [207], his Honour noted that there were some important exceptions which included a potentially large number of people who were not members of the relevant clans who could have various rights in the land arising generally from kinship and other ties to it. Persons, for example, had rights in their mother’s clan country and in their mother’s mother’s clan country, and spouses, although not the “owners” of the land owned by their spouse’s clan, could use it. His Honour said that these entitlements would seem to be rights to use some part of the land for specific purposes and in some instances it would seem more appropriate to characterise these “rights” as obligations. The discussion in Gumana at [208] and following about the rights of entry and the like that other persons apart from clan members held concerned the extent to which these rights and obligations undermined the claim to exclusive possession. However, his Honour held on the evidence that a right of exclusive possession existed.

79 In this regard, at [216], Selway J, having rejected a range of arguments put by the Northern Territory as to why exclusive possession should not be found, held that subject to areas of co-joint ownership, the various rights in relation to the claim area and the traditional mechanisms by which permission might be granted by the relevant clan in relation to its country, were appropriately described in the Commonwealth’s submissions which his Honour then set out. They included non-clan members.

80 There is nothing in Gumana, or in the subsequent appeal to the Full Court in Gumana and Others v Northern Territory and Others (2007) 158 FCR 349; [2007] FCAFC 23 and the High Court in Northern Territory of Australia and Another v Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust and Others (2008) 236 CLR 24; [2008] HCA 29 to suggest that these findings reflected anything other than the particular rights and interests possessed under the traditional law and custom of the Yolngu People. The discussion concerning “permission” in the exercise of rights occurred entirely in that context. It is, however, a context quite divorced from the evidence led before the primary judge in this case and identified before us on this appeal. The rights of spouses and those with spiritual conception on land referred to in the detailed determination in Gumana plainly were not in dispute and fell within the demonstrated traditional law and custom of the Yolngu People. The question before us was not raised or determined in Gumana. As such, Gumana does not suggest that a different result should obtain from that which we have ruled upon.

81 Secondly, Wilson v Northern Territory of Australia [2009] FCA 800 was a consent determination. In that case, the native title rights and interests of estate group members, possessed under the traditional laws and customs of the applicants, included the right to be accompanied by persons who were not native title holders, but were required by traditional law and custom for the performance of ceremonies or cultural activities, had rights in relation to areas according to traditional laws and customs acknowledged by the estate group members, and were required by the estate group members to assist in, observe or record the traditional activities on the areas. Nothing in the consent determination addressed the question pressed on this appeal.

82 Thirdly, Rrumburriya Borroloola Claim Group v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) [2016] FCA 908 is another consent determination of native title. By para 8 of the determination, persons other than the claim group – “other Aboriginal people” – were determined to have rights and interests in respect of the determination area, subject to the rights and interests of the members of the claim group. Those “other Aboriginal people” were not members of the claim group and included members of neighbouring estate groups, the spouses of members of the group, and persons who were spiritually conceived on the estate of the group. Such a determination raises a question as to what the intramural rules of any group are insofar as the recognition of such rights are concerned. The fact, however, that the determination was made by consent in that proceeding and was not the subject of any detailed consideration, render this consent determination of little assistance to the determination of the question before us.

83 Finally, it is necessary to consider the decision of Finn J in Akiba and Another v Queensland and Others (No 3) (2010) 204 FCR 1; [2010] FCA 643, and on appeal in Commonwealth v Akiba and Another (2012) 204 FCR 260; [2012] FCAFC 25 (Akiba FCAFC) and Akiba HC.

84 The question relevantly in Akiba (No 3) was whether rights, which could be exercised in the country of ancestral occupation-based rights holders and arose from a “reciprocal relationship” between a member of an ancestral occupation-based rights holding group (the host) and a person outside that group, were properly characterised as native title rights. At [508] of the decision at first instance, Finn J found that under the normative system of the Torres Strait Islanders, reciprocal rights and obligations could properly be described as rights and obligations that were recognised and expected to be honoured or discharged under Torres Strait Islander laws and customs. They were not mere privileges. Justice Finn also recognised that these rights could be passed down through the generations. However, while holding that these rights may provide a “passport” to the host’s country and, with permission, may allow the reciprocal rights holder to undertake the same activities there as the host, Finn J held that the reciprocal rights were “relationship-based” and, therefore, were properly characterised as personal rights as opposed to rights “in relation to” land or waters within s 223(1) of the NTA (Akiba (No 3) at [507]-[508]).

85 The Full Court dismissed the cross-appeal against this finding in Akiba FCAFC. In their joint judgment at [130], Keane CJ and Dowsett J (Mansfield J relevantly agreeing at [148]) upheld the primary judge’s characterisation of the reciprocal rights. Their Honours held that, insofar as the reciprocal rights relate to land and waters, they are not held by reason of the putative holders’ own connection with the land and waters but rather were “dependent on the permission of other native title holders for their enjoyment” and were mediated “through a personal relationship with a native title holder” (Akiba FCAFC at [130]). As such, the majority accepted the anthropological description of the rights as “status based” reciprocal rights, being rights in relation to the land and waters of another person, as opposed to occupation based rights to access and use land and water under traditional laws and customs such as those concerning descent from an original occupier of the land (at [131]). This characterisation of the reciprocal rights as rights of a personal character dependent on status and not rights in relation to the waters concerned for the purposes of s 223(1), was in turn upheld by the High Court: see Akiba HC at [45] (French CJ and Crennan J) and at [47] (Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ).

86 The decisions of the trial judge and the Full Court in Akiba, confirmed by the High Court, provide clear examples of how not every identified “right” or “interest” arising under the laws or customs of Indigenous peoples will necessarily be found to be “in relation to” land or waters. Close analysis is required of the asserted rights or interests in order properly to characterise them for the purposes of s 223(1). They also demonstrate that where the rights are held mediately by reason of a personal relationship only with a native title holder, who may grant of withhold permission, the rights cannot be said to be native title rights for the purposes of s 223 of the NTA.

87 For the reasons we have earlier explained, upon a close analysis it is apparent that the rights of the rayi holder here are analogous to the reciprocal rights considered in Akiba HC and personal in nature. As such, they are not rights and interests in relation to land. It follows that this ground of the Goolarabooloo appeal fails.

2.7 Does a ritual leader possess a native title right or interest?

2.7.1 The Northern Tradition and role of the ritual Law leaders

88 A further question arising on the appeal is whether a ritual leader, who does not have descent or succession rights in the Jabirr Jabirr determination area in the manner earlier described, may nonetheless be the holder of a native title right or interest as defined by s 223(1) of the NTA, in relation to a place or places for which the ritual leader has some responsibility.

89 In this regard the expression “ritual leader”, along with some related expressions, is used in various contexts in the reasons of the primary judge. Other expressions used include “Law Man”, “Law Boss”, “senior Law Man/Boss”, “madja” and “galud”. Depending on the relative seniority of a person one or other of those expressions may be more appropriate.

90 The Goolarabooloo case at trial and on appeal is that a “ritual leader” is any initiated male who has acquired the relevant knowledge and experience for a particular area within the determination area, whether or not they are a senior Law man/madja and whether or not they have native title rights through descent or succession.

91 At [505] of the primary judgment, the primary judge said that the Northern Tradition is the ritual practice “of the Goolarabooloo application area”. The Northern Tradition is not, however, confined to that area but relates to the ritual practice of the various Aboriginal peoples in the area along the coast to the north of Broome, in the Beagle Bay area, not just the Jabirr Jabirr.

92 As noted in the primary judgment at [529], Mr Richard Hunter, one of the Goolarabooloo witnesses, said that he was a Goolarabooloo man and a “Law Boss for the Northern Tradition”. In this regard, he said that he and others like him “are responsible for that Northern Law, around the Broome area and through Goolarabooloo country, so that if something threatens the law or the country then we have to stand in front. We take this responsibility very seriously. We hold that law with other bosses from the Northern Tradition”. It may be appreciated that to the extent Mr Hunter referred to Jabirr Jabirr country as “Goolarabooloo country” this was mere assertion and contrary to the judge’s ultimate findings.

93 The primary judge, at [505] of the primary judgment, provided more detail about the nature of the ritual practice of the Northern Tradition. None of what he said is in dispute in the appeal. He explained that rituals are performed in ceremonies involving narrative, song and dance. He said that, in current times, the most important ceremony is the male initiation ritual. Initiates are required to meet certain physical demands, to receive instruction in sacred Law, and to pass through a series of status grades linked to sequentially staged rites. The rituals enact the journeys of three or four supernatural beings in the Bugarrigarr (the Dreaming) time and the activities of other creatures such as the two snakes and emu. His Honour explained that performance of the rituals teaches the origin of the natural world and of the social world, the demarcation of territorial space, and the rules of social conduct such as the generational moiety system, marriage restrictions, food prohibitions, avoidance relationships, and gender restrictions in relation to knowledge and practices. His Honour further explained, at [506], that the role of senior Law men, madja, is to lead the ceremony while the role of junior Law men is to assist the madja. Senior Law women perform an organisational role in the management of the ceremony, including controlling the seating arrangements of male participants during the nguril rites, albeit that much of the ritual is restricted to men.

94 Importantly, at [507] of the primary judgment, his Honour explained that the role of the men and the women Law bosses thus involves knowledge of ritual practice and of all the stories, music, and dance, used in ceremony to explain the cosmology and social mores of the people. It might be interpolated at this point that the reference to “the people” is not a reference to a single group of persons who may hold native title in common, but to a wider group of people in the Northern area who share like laws and customs of the type referred to, and share the same Dreaming ceremony and stories. As such, it involves various groups (as we have explained) in the area to the north of Broome, in the Beagle Bay area, including in the Jabirr Jabirr determination area. It follows, for example, that young male initiates may be initiated at a ceremony in the Jabirr Jabirr determination area that involves young initiates who come from a number of other language groups or native title holding groups in the Northern area, including the Jabirr Jabirr, Nyul Nyul, Nimanbur and so on.

95 The primary judge, at [507] of the primary judgment, added that the acquisition of such knowledge is incremental and occurs over long periods which, in part, explains why Law bosses are older people. The primary judge added:

Territories are of concern to Law bosses both because the ceremonies are conducted on Law grounds which are significant places requiring protection, and also because the mythology enacted in the ceremony is related to places in the country. Significant places of mythological importance are under the protection of the Law bosses. However, territorial concerns are but a part, and perhaps a smaller part, of the matters of concern to Law bosses. Nonetheless, it is only that part of the concern of the Law bosses to which the debate about rights in land in this proceeding related. The extent of the part that the protection of territory plays in the wider ranging interests of Law bosses may throw some light on the question whether ritual knowledge of Law bosses is the basis of the acquisition of rights and interests in land.

2.7.2 The primary judge’s finding rejecting the claims to hold native title based on status as a ritual leader should be upheld

96 His Honour’s findings about the workings of the Northern Tradition and the role of ritual leaders within it are important to the resolution of the appeal question now under consideration and to explaining why his Honour found that ritual leaders do not, as a result of this status alone, have native title rights and interests in the Jabirr Jabirr determination area. In our opinion, the primary judge’s finding is strongly supported by the weight of the evidence from the Aboriginal witnesses and the nature of that evidence concerning the question of what rights or interests a ritual leader, who was not a traditional owner with descent based rights, possessed in Jabirr Jabirr country.

97 The evidence of the Goolarabooloo on this question, as his Honour found, at [527] of the primary judgment, was not seriously at odds with the Jabirr Jabirr and Bindunbur evidence on this point. At [527], his Honour stated that the claim that ritual knowledge gives rise to rights in country was based on Professor Cane’s view, rather than on the evidence of the Goolarabooloo witnesses in most cases. His Honour, however, noted that the evidence of Mr Phillip Roe was arguably one exception at least in respect of Law grounds. His Honour pointed out that in a passage not relied on in the Goolarabooloo submissions, but nonetheless on point, Mr Roe responded in cross-examination as follows:

MR KEELY: … The next one is traditional religious knowledge of the area. Do you say that gives you rights in country or not, just to know the religious side of the area? Does that give you rights or not?

PHILLIP ROE: Well, if you got your law and culture, and you know the country, you're familiar with the country, you've got your law and culture, and you keep your country strong, because you have rights in the country.

MR KEELY: Wouldn't there be – and I don't want to get into dangerous territory with the men down the back, but wouldn't there be – if that was right, wouldn't people like Sandy Paddy have rights in the country when he was still alive, Peter Angus, Freddie Bin Sali, perhaps [Mr R] Wiggan?

PHILLIP ROE: Well, they'd have rights because they speak for the law that run through there.

MR KEELY: So do you say that all of those men, in their day, and men like them, all have rights in the country?

PHILLIP ROE: Like I said, those guys kept the law run through where there's law grounds and things in that place. They have the right and they have their say.

MR KEELY: So their say is limited to law grounds; can we agree about that?

PHILLIP ROE: Yes.

…

MR KEELY: So that, again, knowledge of the ceremonies doesn't get you rights unless you're in the – you're – you're the right – one of the right people - - -

PHILLIP ROE: It get – it gets you rights and things in country.

MR KEELY: Is that limited to, I think, what you said before, which was the law grounds and so on?

PHILLIP ROE: Well, if there's grounds there and things, like, I go back, what I said earlier. I'm not going into that situation and things because you've got females - - -

MR KEELY: Yes.

PHILLIP ROE: - - - and you got other bosses here.

(Emphasis in primary judgment.)

98 The evidence given by Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr men, however, was strongly against the proposition that ritual leaders, who are not descent based rights holders, gain “native title” in Jabirr Jabirr country. In short, the effect of their evidence was that, just because a man is a senior “Law man” in the Northern Tradition does not mean that the cultural rights or status thereby acquired results in that person possessing rights or interests under the law of the Jabirr Jabirr in relation to land or waters.

99 The most compelling evidence relied on by the primary judge which deals with this issue was given by Mr P Sampi, a Bardi man, who was accepted as the most senior Northern Tradition Law man at the time of the hearing (but who had passed away when the primary judge delivered judgment). We note what Mr P Sampi said on this topic as set out in the primary judgment at [509]-[514]:

509 He said that if something had to be decided which related to land, the rights holders by descent would decide. He explained the supportive role of the Law men in re-examination as follows:

MR KEELY: What role can the law bosses, even the senior law bosses, the Madja Madjid, what role can they play?

P. SAMPI: Well, they would ask for some help and we’d sort of - - -

MR KEELY: They’d ask for some help?

P. SAMPI: Yes, we’d support them, then naturally we’d give him – give them support because that’s something to do with the song line, you know.

MR KEELY: You’d give them help?

P. SAMPI: Yes.

MR KEELY: And when you give them help in relation to the song line travelling through those areas, does that make any of you lawmen like traditional owners or gumalid for that country?

P. SAMPI: No, not us. We’d be only – we’d be just to support them.

MR KEELY: Of all the men whose names we’ve talked about as being at those meetings and being the senior – the Madja Madjid, including the people here today, have you ever heard any of them say, ‘That’s my country there’ at James Price Point?

P. SAMPI: No, I haven’t heard any.

(Emphasis in primary judgment.)

510 Again in re-examination, Mr P Sampi explained how the law men operate as follows:

MR KEELY: So, I’m just asking is it necessary for the group to think about that or can one person do it by himself?

P. SAMPI: No, it’s got to be a group that does that. It can’t be one – one person.

MR KEELY: It can or can’t?

P. SAMPI: Cannot.

MR KEELY: Can’t be?

P. SAMPI: Cannot be one person. It has to be a group.

511 The way in which responsibility is placed on madja and then how that responsibility is to be exercised was described by Mr P Sampi in his affidavit sworn 4 October 2015, as follows:

68. When a man is given that thing [sacred object signifying authority] in the ceremony, it means that he has a responsibility to look after the Law ground where the ceremony happened. For J Roe this meant that he had a responsibility to look after the Law ground at OTC, just like his grandfather Mr Roe had. It also means that the person has a general responsibility as a junior madja.

69. When a man is given that thing in the ceremony, he has authority, but he's only one of the people who have that authority. Other people have had that authority for longer than the new man. He must respect them. He can't act on his own; he has to work with the other elders who have that authority. When a man gets that thing in the ceremony, he can't start to tell other elders what to do; he must still be accountable to all the madja, especially the senior madja.

(Emphasis in primary judgment.)