FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd v JBS Australia Pty Limited [2018] FCAFC 207

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN MEAT GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 168 396 316) Appellant | ||

AND: | JBS AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 011 062 338) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Orders 1, 2 and 3 of the orders of the Court made on 11 December 2017, and the order of the Court made on 22 December 2017, be set aside and in lieu thereof (subject to an order in relation to the costs of the proceeding at first instance) the application be dismissed.

3. Within 14 days, the parties file any submissions and proposed orders (of no more than three pages) on costs of the proceeding at first instance.

4. The appellant be released from its undertaking given on 21 December 2017.

5. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The respondent in the appeal, JBS Australia Pty Limited, sued on two registered trade marks: trade mark 515268 and trade mark 1719465. It originally advanced claims of passing off and contravention of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) but abandoned these claims in the course of the hearing before the primary judge.

2 Trade mark 515268 is a device comprising a stylised map of Australia within which the letters “AMH” in stylised form are contained. These elements are set on a ribbon device, which incorporates a chevron. The primary judge referred to this mark as the AMH device mark or, simply, the device mark. It is depicted in Schedule A to these reasons.

3 Trade mark 1719465 is a word mark comprising the letters “AMH” simpliciter. The primary judge referred to this mark as the AMH mark. We will refer to it as the AMH word mark.

4 The respondent claimed that each of five marks used by the appellant, Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd, infringed the AMH device mark and the AMH word mark. The appellant has lodged applications under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act) in respect of some of these marks. The respondent has opposed the applications, which proceedings have been stayed pending the outcome of these Court proceedings.

5 The five marks are:

(a) a device mark the subject of trade mark application 1616230. The primary judge referred to this mark as the AMG device mark. It is depicted in Schedule B1 to these reasons;

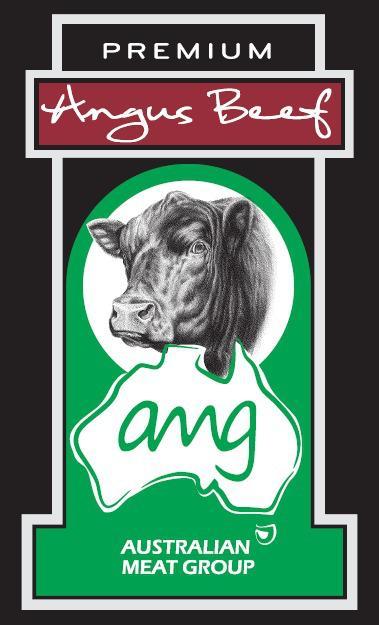

(b) a device mark the subject of trade mark application 1756459. The primary judge referred to this mark as the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark. It is depicted in Schedule B2 to these reasons;

(c) the device mark the subject of trade mark application 1756462. The primary judge referred to this mark as the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark. It is depicted in Schedule B3 to these reasons;

(d) a device mark which is said to be a version of the AMG device mark. It is depicted in Schedule B4 to these reasons. The respondent called this mark the AMG solid mark; and

(e) the letters “AMG” which the respondent called the AMG word mark.

6 We will refer to the respondent’s marks as the AMH marks and to the appellant’s marks as the AMG marks.

7 The case advanced in the Fourth Further Amended Fast Track statement was that the appellant’s use of each of the AMG marks was an infringement of each of the AMH marks because the use was “at least use of a deceptively similar trade mark”. The respondent alleged that infringement arose under s 120(1) and s 120(2) of the Act.

The primary judge’s findings

8 The primary judge dealt with the case on the footing that the substantive question raised on infringement was one concerning the alleged deceptive similarity of each of the AMG marks to each AMH mark. The case of substantial identity of the marks, although not abandoned, was not emphasised at the primary hearing. The primary judge analysed that question against three settings:

(a) use of the AMG marks in the Australian domestic market other than in respect of transactions between retailers and consumers involving potential sales of whole primal cuts (setting (a));

(b) use of the AMG marks in the Australian domestic market in respect of transactions between retailers and consumers involving potential sales of whole primal cuts (setting (b)); and

(c) use of the AMG marks in the export market in respect of sales occurring directly into the export market and to entities within Australia which supplied meat products into the export market (setting (c)).

9 The primary judge concluded that each of the AMG marks was deceptively similar to each of the AMH marks. In coming to this conclusion, it is clear that his Honour was significantly influenced by the reputation he found to exist in each of the AMH marks.

10 The primary judge’s analysis focused on comparisons between, on the one hand, the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark (considered separately) with, on the other hand, each of the AMH marks (also considered separately): see at [279(19)–(33)].

11 In setting (a), the primary judge found that the AMH device mark and the AMH word mark had a strong reputation at all functional levels of the market. The AMH word mark had been used for decades and had a longstanding reputation conditioned by use of the AMH device mark containing the acronym “AMH”. Both marks had been used in connection with a vast number of bags and cartons containing meat products. His Honour did not think that the AMG device mark was sufficiently distinguished from the AMH marks by the inclusion of the words “Australian Meat Group”. Further, in the case of both the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark, his Honour did not think that the last letter “G” in the acronym “AMG” was sufficient to distinguish the marks “when AMH has been used in the same market for so long”: see at [279(23)]. It is not clear whether, in this part of his Honour’s analysis, he was comparing the AMG marks with each of the AMH marks or simply the AMH word mark.

12 In setting (b), the primary judge found that there would be confusion when consumers were presented with primal cuts bearing the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark. This was because there was “at least a reputation subsisting in the AMH device mark and [the AMH] word mark” in respect of which consumers would have an imperfect recollection. His Honour was satisfied that consumers would be caused to wonder or left in doubt whether it might not be the case that the meat products of AMG were those of AMH: see at [279(25)]. In coming to this conclusion, it seems that his Honour accepted that a consumer, in this setting, might think that the AMG device mark was a version (perhaps a more modern version) or a variant of the AMH device mark: see at [279(26)].

13 In setting (c), the primary judge found there was also a likelihood of confusion in that export customers having a recollection of the AMH device mark and the AMH word mark might be caused to wonder or left in doubt about whether meat products marked with the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark are products of the respondent or associated with the respondent in some way. His Honour said that this was especially so when regard was had to the many different languages in the various export destinations in which importers of meat products operate: see at [279(27)].

14 After considering these settings, the primary judge expressed his satisfaction that, at each functional level of the domestic market and the export market, the appellant had infringed the AMH marks by its use of the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark: see at [279(33)].

15 Up to this point, we have summarised the primary judge’s analysis insofar as it involved a comparison of the AMG device mark and the AMG word mark with each of the AMH marks. At [279(34)], his Honour turned to the appellant’s use of the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark and expressed his satisfaction that each mark was deceptively similar to the AMH device mark and the AMH word mark. His Honour did not elaborate on why this was so.

16 His Honour made no explicit finding of deceptive similarity in relation to the AMG solid mark. In other parts of his reasons, his Honour described this mark as a version of the AMG device mark. It is certainly possible that his Honour’s findings of deceptive similarity in relation to the AMG device mark were intended to encompass the AMG solid mark.

17 Based on his conclusions concerning deceptive similarity, the primary judge found infringement under s 120(1) of the Act. It is fair to say that his Honour did not see s 120(2) as playing a role in the case before him. This is because his Honour found that the goods in respect of which the AMG marks were used were essentially the same goods in respect of which the AMH marks were registered: see at [236]. In short, on his Honour’s findings, there was no need to consider whether the appellant’s goods were “goods of the same description” as the registered goods.

The grounds of appeal

18 The notice of appeal contains eight grounds. Grounds 5 and 7 were not pressed at the hearing of the appeal. The remaining grounds are:

1. In determining whether the respective marks are deceptively similar, the primary judge erred in principle by failing to consider at all the extent to which elements of the parties’ respective trade marks are descriptive or common to the trade, including:

a. a map of Australia, which the evidence demonstrated is commonly used by numerous traders to describe meat produced in Australia; and

b. acronyms including the letters “AM”, which the evidence demonstrated are commonly used in the names of many organisations and traders involved in the sale or promotion of Australian meat as an abbreviated descriptive reference to “ Australian meat”.

2. Further, in determining whether the respective marks are deceptively similar, the primary judge erred in principle by failing to consider at all the principle that marks consisting of a small number of initials alone have little inherent capacity to distinguish.

3. The primary judge ought to have taken the above considerations into account, ought to afforded [sic] little weight to such elements which are descriptive or common to the trade, and ought to have afforded greater weight to other elements which distinguished the respective marks, so as not to grant the respondent an inappropriately broad monopoly, in the context of Australian meat, in acronyms beginning with “AM” and/or maps of Australia.

4. Further or alternatively, at [106], [279(19)(a), (b) and (c)], [279(21)], [279(23)] and [279(25)] the primary judge erroneously relied upon the scale of prior use and reputation vesting in the respondent’s registered marks (as recounted at [29] to [52], [69], [248]) to support findings of deceptive similarity in the context of trade mark infringement under s 120 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth): cf. C A Henschke and Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539 52 IPR 42 at [44]–[45], [53] per Ryan, Branson and Lehane JJ.

...

6. Further or alternatively, the primary judge erroneously gave no weight or insufficient weight to the lack of any evidence of actual confusion and the appellant’s evidence that there had been no confusion, despite the very substantial sales under the appellant’s marks over more than 18 months, and failed to deal with Mr Cabral’s evidence in cross-examination as to why any instances of confusion at the wholesale or export level are likely to have come to the attention of the seller: Tr. 201.17–46.

...

8. The primary judge’s finding of deceptive similarity was affected by one or more of the above errors and he ought to have found there was no deceptive similarity for the purposes of trade mark infringement.

19 Ground 4 is directed to the substantive question of principle addressed in the appeal. We will deal with this ground separately from the other grounds. Grounds 1 to 3 and 6 are directed to aspects of the task of trade mark comparison that the primary judge was required to undertake. These grounds really culminate in the overarching contention in Ground 8 that the primary judge erred by not finding that the AMG marks were not deceptively similar to the AMH marks.

20 For the reasons which follow, the appeal should be allowed.

Ground 4

21 Section 120 of the Act is in the following terms:

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(b) services that are closely related to registered goods; or

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

(3) A person infringes a registered trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is well known in Australia; and

(b) the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(i) goods (unrelated goods) that are not of the same description as that of the goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered (registered goods) or are not closely related to services in respect of which the trade mark is registered (registered services); or

(ii) services (unrelated services) that are not of the same description as that of the registered services or are not closely related to registered goods; and

(c) because the trade mark is well known, the sign would be likely to be taken as indicating a connection between the unrelated goods or services and the registered owner of the trade mark; and

(d) for that reason, the interests of the registered owner are likely to be adversely affected.

(4) In deciding, for the purposes of paragraph (3)(a), whether a trade mark is well known in Australia, one must take account of the extent to which the trade mark is known within the relevant sector of the public, whether as a result of the promotion of the trade mark or for any other reason.

(Notes omitted.)

22 For the reasons which follow, we have come to the view that the primary judge did err in how he utilised the reputation of the respondent.

23 How the primary judge came to approach the matter as he did can perhaps be explained by how the case was presented to him by the parties.

24 The proceedings were initially brought not only for trade mark infringements under s 120, but also for passing off, misleading or deceptive conduct and the making of false or misleading representations. As a preamble to the pleaded claims in the various Fast Track Statements, the respondent (as applicant) pleaded the strength and longevity of its business and brand. Paragraphs 13 and 14 of the Fourth Further Amended Fast Track Statement stated as follows:

13 The applicant’s business and AMH brand is long standing and has a significant reputation in the industry and amongst customers. The AMH brand has been in existence since at least 1989 and is widely known at the wholesale, retail and consumer level. The AMH brand is so ubiquitous and of such long standing that consumers and persons involved in the meat industry (“the relevant class”) generally are familiar with it and with its use in relation to meat and meat products.

14 The applicant or its predecessor in title has widely and extensively used and promoted its goods under and by reference to the AMH trade marks and the AMH word mark since at least 20 July 1989. As a consequence of that extensive and wide use:

(a) persons in Australia have come to exclusively and distinctively associate the AMH trade marks and the AMH word mark with the applicant;

(b) the AMH trade marks and the AMH word mark have become well and widely and favourably known to the relevant class throughout Australia as denoting the business of the applicant and the goods sold by it and has acquired a favourable reputation and goodwill; and

(c) persons who intend to acquire or propose to acquire goods under or in respect of the AMH trade marks or AMH word mark intend and/or expect to acquire such products or otherwise transact or conduct business with the applicant and in doing so rely upon its reputation.

25 The Fast Track Response was a long, discursive and argumentative document, not being one apt to distil issues in dispute. It did not in terms raise the last paragraph of s 120(2). Nor was s 120(3) relevant given that the goods in which the appellant and respondent traded were in the same classes and were of the same description. Nor in its discourse on legal principle and extracts from numerous cases, did it mention CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1561; 47 IPR 63 or the proposition from [44] of the Full Court’s judgment in CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539; 52 IPR 42 (Henschke).

26 The submissions, both written and oral, of the respondent (as applicant) emphasised the strong reputation of the AMH brands. There was much evidence (to which the primary judge made reference) about the volumes of sales of packaged meat on which the AMH marks were placed. This was undoubtedly relevant to the passing off, misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representation cases. But, after these were abandoned just prior to final addresses, this evidence was pressed on the question of deceptive similarity.

27 The appellant (as respondent below) also stressed the strong reputation of the AMH brand in its submissions. That submission was of a particular kind. It invoked a submission that if a trade mark’s reputation was strong and ubiquitous it would lessen the likelihood of imperfect recollection of the registered mark and so lessen the likelihood of deception. The approach was said to be supported by Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths [1999] FCA 1020; 93 FCR 365 and Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 174; 84 IPR 12. The appellant did not, however, submit to his Honour that, if its submissions about Woolworths and Mars were not accepted, then it was impermissible for his Honour to take the reputation of the AMH brand into account in assessing deceptive similarity.

28 It will be necessary to say something in due course about Woolworths and Mars. For present purposes, it is plain that the primary judge rejected the Woolworths and Mars submissions, but nevertheless went on to take AMH’s reputation into account. The reasons make that clear.

29 It is unnecessary to go exhaustively through the reasons in detail to reveal the effect on the judgment and reasoning process of the primary judge taking into account the reputation of AMH. That the primary judge’s view of the strong brand reputation in AMH was of significance to his conclusion of deceptive similarity is plain in [106], [279(13)], [279(15)], [279(19)(a)–(c)], [279(23)] and [279(25)].

30 The respondent denied any error of the primary judge. It pointed out that at trial AMG had not only conceded the reputation of AMH, but also relied on it by invoking Woolworths and Mars for the approach we have identified. That, of course, is no answer to taking into account brand reputation in assessing deceptive similarity if such is not the proper approach.

31 The respondent had three other answers to this criticism on appeal.

32 First, it submitted that the primary judge was legitimately dealing with the evidence of reputation in resolving the issue raised by s 120(2) of the Act. That submission, however, does not answer the question of the use of reputation in the inquiry for s 120(1) as to whether there is deceptive similarity. In any event, read as a whole, the reasons reflect an attention to the central issue in the case: whether there was deceptive similarity for the purposes of ss 10 and 120(1) of the Act.

33 Secondly, the respondent submitted that, properly understood, the principles in Henschke, Woolworths and Mars permit the use of reputational evidence of the applicant’s mark not only to negative the likelihood of deceptive similarity, but also to underpin or inform the likelihood of deception.

34 Thirdly, if the second submission was not accepted, it submitted Henschke was wrongly decided and should not be followed.

35 The second and third answers to the criticism require an analysis of the relevant cases.

36 In Woolworths, the question was the registrability of a trade mark “WOOLWORTHS metro” in circumstances where there were existing registered marks consisting of the word “metro”. A judge of the Court had upheld an appeal from the Registrar who had refused registration because of the deceptive similarity with the already registered “metro” marks. The appeal was allowed. The primary judge (Wilcox J) had made reference to the familiarity of the name “Woolworths” to Australians as part of the reason why that word was the part of the mark most likely to be noticed and remembered (and, so, being a factor in undermining a conclusion of likely confusion or similarity). On appeal, French J (with whom Tamberlin J agreed) said the following at [61]:

61 … His Honour’s reference to the familiarity of the name “Woolworths” in Australia was appropriate. Where an element of a trade mark has a degree of notoriety or familiarity of which judicial notice can be taken, as is the present case, it would be artificial to separate out the physical features of the mark from the viewer’s perception of them. For in the end the question of resemblance is about how the mark is perceived. In the instant case the visual impact of the name “Woolworths” cannot be assessed without a recognition of its notorious familiarity to consumers.

37 Justice Tamberlin added the following remarks in a concurring judgment at [105] and [106]:

105 … An important distinguishing feature of the mark is to be found in the impact on the perception of a viewer of the widely-known name “WOOLWORTHS” as part of it. The name is widely understood in the Australian community to refer to a well-known chain of retail stores, such that it would play an important part in the perception of a viewer. Wherever the mark in suit is displayed it will always bear the description “WOOLWORTHS”, whereas any goods sold simply under the “metro” banner will lack this central element.

106 In particular, I agree that when considering the perception and understanding of a person viewing the mark, making due allowance for imperfect recollection, the association conjured up by the “WOOLWORTHS” name makes it a prominent distinguishing feature of the mark. The word “metro”, on its own, conveys no such association and it was open to his Honour to conclude that the “WOOLWORTHS metro” mark is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

38 Justice Branson had a quite different view in dissent. Her Honour’s analysis of the history of s 44 led her to conclude that the test for deceptive similarity was not intended to be complicated by considerations of reputation in trade marks.

39 The issue of reputation and trade mark infringement arose again a little over a year later in Henschke. The Henschke companies were the owners of the trade mark ”Hill of Grace” registered in respect of wines, spirits and liqueurs. Rosemount Wines proposed to sell under a trade mark “Hill of Gold”, which had been registered since 1979 but only purchased by Rosemount in 1996. Henschke sought to restrain Rosemount on the grounds of trade mark infringement, passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct. Henschke also sought removal of Rosemount’s mark from the Register. Rosemount cross-claimed for removal of Henschke’s mark. The application and cross-claim were dismissed. In the appeal, Henschke complained about how the trial judge (Finn J) had dealt with expert evidence and raised on appeal the question that the reputation of Henschke’s mark should have been taken into account in determining deceptive similarity and infringement. On appeal, the Court (Ryan, Branson and Lehane JJ) looked at the extensive body of reputational evidence. At [36]–[58], the Court carefully and thoroughly discussed the place of reputation in trade mark infringement. From that analysis, the Court said at [44]–[45]:

44 Essentially what is required is a comparison between the mark of the registered owner and that of the alleged infringer. A wider inquiry of the kind that might be undertaken in a passing off action, or in a proceeding in which contravention of Pt V of the Trade Practices Act is alleged, is not appropriate. In New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Company Ltd (1989) 86 ALR 549, in a passage in his judgment not affected by the proceedings on appeal, Gummow J said at 589:

“In determining whether MOO is deceptively similar to MOOVE, the impression based on recollection (which may be imperfect) of the mark MOOVE that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, is compared with the impression such persons would get from MOO; the deceptiveness flows not only from the degree of similarity itself between the marks, but also from the effect of that similarity considered in relation to the circumstances of the goods, the prospective purchasers and the market covered by the monopoly attached to the registered trade mark: Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414–15; Polaroid Corp v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491 at 498. The latter case is also authority (at 497) for the proposition that the essential comparison in an infringement suit remains one between the marks involved, and that the court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit.”

As to the limited range of the inquiry in an infringement action, see also Saville Perfumery Ltd v June Perfect Ltd (1941) 58 RPC 147 at 175 (the reference by Sir Wilfrid Greene MR in the judgment of the Court of Appeal, at 161, to the significance of cases in which traders and perhaps the public might be expected to receive a strong impression of the actual mark, is plainly, in our view, intended as a reference not to the reputation of a particular trader or of a particular name but to the way, or circumstances, in which a particular class of goods is marketed). See also D R Shanahan, Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off, 2nd ed 1990 at 338, 339; T A Blanco White and R Jacob, Kerly’s Law of Trade Marks and Trade Names, 12th ed 1986 at 14–16.

45 Consistently with the nature of the test of deceptive similarity and the authorities to which we have referred, it is not easy to see what relevance the reputation an applicant may have in a particular mark (even the “icon status” of that mark) has in an action for infringement brought in reliance on s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act. (Clearly, and by contrast, it is relevant under s 120(3) and may be relevant under s 120(2)). Nor, with certain exceptions to which we shall come, were we directed to a course of authority in which, where there has been a question of infringement by use of a deceptively similar mark, the reputation of the plaintiff in the mark allegedly infringed has been taken into account. Indeed, the course of authority has been quite to the contrary. The search has concentrated on such matters as ascertaining the essential element of a mark, the impression taken away by one who looks at it, and how it sounds when pronounced. (Australian Woollen Mills, Shell, Saville Perfumery and Aristoc Ltd v Rysta Ltd [1945] AC 68 are all well known examples).

40 The Court then discussed certain qualifications. Relevant for present purposes was the discussion of Woolworths at [51]–[52] as one of those qualifications. At [52] the Court said:

52 Woolworths was not an infringement case and, of course, the notoriety taken into account was not any notoriety attaching to marks already registered (or marks applications for which had been lodged before the Woolworths application); the notoriety attached to an element of the mark for registration of which Woolworths had applied. Nevertheless, in our view, Woolworths suggests a proposition for which the cases on which the appellants rely may be taken as authority. It is that, in assessing the nature of a consumer’s imperfect recollection of a mark, the fact that the mark, or perhaps an important element of it, is notoriously so ubiquitous and of such long standing that consumers generally must be taken to be familiar with it and with its use in relation to particular goods or services is a relevant consideration. It is unnecessary to consider whether the cases are authority for precisely that proposition. All that is necessary for present purposes is to hold, as we would, that they are authority for no wider proposition in relation to the relevance, on a question of deceptive similarity in proceedings where it is alleged under s 120(1) that a registered mark has been infringed, of evidence as to the reputation attaching to the mark. A wider proposition would not, in our view, be consistent with the earlier, and binding, authority to which we have referred. It is unnecessary, in order to decide this case, to go further.

41 The limited proposition which the Court accepted Woolworths stood for was not that reputation is relevant generally to deceptive similarity. That is what was being rejected. It was a proposition that deceptive similarity from imperfect recollection might be countered by showing the well-known nature of the registered mark and the lessened likelihood of imperfect recollection. This is how we understand cases in this Court have reconciled Woolworths in the jurisprudence: see Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH [2001] FCA 1874; 190 ALR 185 at 217 [155] (Lindgren J); Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 196; 209 ALR 1 at 22 [90]; Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 606; 81 IPR 354 at 376 [96]; and on appeal [2009] FCAFC 174; 84 IPR 12. We do not consider that Idameneo (No 789) Ltd v Symbion Pharmacy Services Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 164; 94 IPR 442 should be taken as contrary to this approach.

42 The challenge to Henschke arose in unsatisfactory circumstances. No clear warning was given to the Court of the argument. Nevertheless, the submission was made. We are not persuaded on the submissions put that the decision is plainly wrong. Indeed, to entertain the argument fully would involve an analysis of the history of, and proper approach to, a number of provisions of the Act and also to the correctness of other cases, including Woolworths and Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; 96 FCR 107 (see the comments of the authors of the 6th Edition of Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off at 617 [85.690]). In the circumstances, we propose to apply Henschke as it has been understood to date.

43 We turn therefore to the question of deceptive similarity on this basis.

Grounds 1–3, 6 and 8

The parties submissions

44 We approach the task of assessing the question of deceptive similarity in accordance with Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424 at 437–438 [28]–[29]. See Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 358 ALR 683 at 686–689 [4]–[10], 696–697 [52]–[53] and 724 [169].

45 Before dealing with the submissions and the substance of the appeal, it is appropriate to note (indeed, to emphasise) that the approach of the learned primary judge was conditioned in large part (if not fully) by the way the matter was presented to him by the parties. Were there not involved considerations that affect the state of the Register, and so the wider public interest, there may well have been force in any submission, if made, that to the extent his Honour approached the matter conformably with the arguments made, the parties (in particular the appellant) should be kept to the framework argued. It is unnecessary to express any final view on that question. But such considerations may be relevant to the question of the proper order for the costs of the proceeding at first instance.

46 The appellant advanced five principal submissions.

47 First, the appellant submitted that the last letters in the acronyms AMH and AMG are, in look and sound, very different and that this difference is sufficient to avoid a real and tangible risk of deception.

48 Secondly, and relatedly, the appellant submitted that three letter acronyms are common in the Australian meat industry. Further, the common element “AM” in each acronym is an obvious contraction of “Australian meat”. Stylised maps of Australia are also common. The appellant submitted that these elements are used simply for their descriptive capacity. It submitted that it is established that commonly-used or descriptive aspects of trade marks under comparison should be discounted.

49 Thirdly, the appellant submitted that the device elements of the AMH device mark, on the one hand, and the device elements of the AMG device mark, the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark, the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark, and the AMG solid mark, on the other, contain additional features which serve to distinguish the two groups of marks.

50 Fourthly, the appellant submitted that the risk of deception is diminished where, as the primary judge found here, many domestic wholesale customers bring an inquiring mind to purchase transactions and, in relation to the export market, the appellant had engaged in a relationship-based campaign to attract buyers of its export meat products.

51 Fifthly, the appellant submitted that there was no evidence before the primary judge of actual confusion.

52 As to the acronyms AMH and AMG, the respondent submitted that the primary judge gave consideration to the evidence concerning “the presentation of trade marks” at the wholesale and retail levels, including the use of acronyms. The respondent submitted that the primary judge gave extensive consideration to the difference between the last letters “H” and “G” in the competing acronyms, but rejected this difference as not being “sufficiently differentiating”.

53 As to the appellant’s reliance on the usage of common elements, such as the letters “AM” on the map of Australia, the respondent submitted that, in fact, the appellant adduced no evidence of usage; it merely listed some marks in its Fast Track response. The respondent submitted, once again, that the primary judge gave extensive consideration to the evidence. The respondent also noted that no mark referred to by the appellant comprised both the letters “AM” and a map of Australia.

54 As to additional distinguishing features presented by the respective device marks, the respondent submitted that the appellant’s submissions overlooked the word marks.

55 As to the appellant’s reliance on a reduced risk of deception, the respondent submitted that this could only be relevant to a consideration of infringement under s 120(2) of the Act.

56 Finally, in relation to the absence of evidence of actual confusion, the respondent submitted that evidence of actual confusion is irrelevant to findings of deceptive similarity.

57 Apart from the relevance and significance of findings on reputation to the question of deceptive similarity, the parties’ submissions did not take issue with the primary judge’s summation of the guiding principles on trade mark comparison. Those principles are well-known and do not require elaboration in these reasons.

Analysis

58 We commence our analysis by making some observations about the primary judge’s reasoning which led to his Honour’s conclusions on deceptive similarity between the competing marks.

59 As we have recorded, the primary judge’s trade mark comparisons centred on his Honour’s assessment of the strength of the reputation in the AMH word mark seen in the context of a market in which the participants – most significantly, wholesale buyers of meat products – use acronyms (generally, three-letter acronyms) in emails and on price lists and the like, to refer to suppliers and sources of supply. We refer, for example, to his Honour’s summary of Mr Tancred’s and Mr Tatt’s evidence at [58]–[59] and [77] of the primary judge’s reasons. Indeed, the origination and adoption of the appellant’s name “Australian Meat Group” was influenced by the market’s practice of using acronyms to refer to meat suppliers. One of the originators of that name, Mr Cabral (the Managing Director of the appellant), gave evidence of his expectation when selecting the name “Australian Meat Group” that it would be contracted to the acronym AMG: see, for example, [122]–[125] and [257] of the primary judge’s reasons.

60 The respondent’s case at trial was that, having regard to its reputation in the AMH acronym, a customer might be confused and be likely to place an order with the appellant (AMG) when the customer was intending to place an order with the respondent (AMH), particularly if the customer saw (say, on a price list) the AMG acronym alone. The respondent conceded that its proposition might be “less compelling” if the buyer were to see the AMH and AMG acronyms “next to one another”: see at [80]–[81] of the primary judge’s reasons.

61 The strength of the reputation which the primary judge found to subsist in the AMH acronym was such that, even though his Honour accepted that:

(a) buyers (wholesalers, manufacturers, supermarkets and export buyers) of the appellant’s products are discerning and are likely to bring an inquiring mind to the relevant transactions: see at [254];

(b) the nature of the relationship and the value and volume of the goods purchased (the average sale to domestic customers by AMG was approximately $15,000 and the average invoice for export sales was approximately $85,000) would be likely to cause such a buyer to bring an inquiring mind to the transaction: see at [259];

(c) to this extent, many of the relevant market participants would be discerning and that this consideration characterised ordinary transactions at the domestic wholesale level: see at [279(28)]; and

(d) the AMH and AMG acronyms would each be pronounced as a “string of letter names” with the respective last letters “H” and “G” differentiating each initialism (the respondent accepted at trial that “H” and “G” are “phonetically and visually dissimilar”): see at [215] and [272],

the difference between the last letters of each acronym was, nonetheless, “not a sufficiently distinguishing feature”. At [279(24)], his Honour continued:

I accept that in oral communication in the hurly burly of oral trading transactions between retailer and wholesalers the emphasis is likely to be upon the “AM” component of the letter acronyms and that the last syllable is not sufficiently differentiating …

62 The primary judge’s analysis of whether the competing marks were deceptively similar proceeds from this point – that is, the centrality of the AMH acronym and its strong reputation in the market for the supply of meat products. For example, when considering the AMH device mark, his Honour appears to have treated the AMH acronym as, by far, the predominating feature, even though his Honour’s description of the AMH device mark included reference to its other features.

63 We think this treatment of the AMH device mark is evident from his Honour’s analysis of acronyms and initialisms, his Honour’s reference to the “strong reputation for the AMH brand in all functional aspects of the supply chain amongst those cohorts participating as wholesalers, distributors, manufacturers, supermarkets, butchers and retailers” (see at [279(15)]), and his Honour’s finding that the longstanding reputation of the AMH word mark has been “conditioned by use of the AMH device mark containing the acronym” (see at [279(21)]). Having noted all the features of the AMH device mark, his Honour appears to have placed little significance on them apart from the presence of the stylised map of Australia on which the acronym is placed.

64 Correspondingly, when the primary judge came to consider the AMG marks, his focus was on the AMG acronym, and the AMG acronym placed on a stylised map of Australia. This had the following consequences.

65 First, although his Honour acknowledged that the AMG device mark contains reference to the words “Australian Meat Group”, he appears to have relegated the significance of this feature for the purposes of trade mark comparison even though it is the appellant’s name and even though it is a relatively prominent and conspicuous feature of the mark. On presentation, the AMG device mark is undoubtedly a direct reference to the appellant – the Australian Meat Group – not an allusive reference to the respondent. So far as the AMG solid mark is concerned (which, as we have said, his Honour appears to have treated as a version of the AMG device mark), the name “Australian Meat Group” is even more prominent. It is set as a cut-out on a large and solid coloured horizontal band on which the stylised map of Australia sits.

66 Secondly, his Honour treated the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark as characterised by the AMG device mark. In fact, his Honour appears to have treated them as, effectively, no more than iterations of the AMG device mark with essentially descriptive and laudatory expressions of no particular trade mark significance: see at [279(4)]. This is perhaps the reason why his Honour did not elaborate on why, in his assessment, these particular marks were deceptively similar to each of the AMH marks.

67 In our respectful view, the primary judge erred in the way he undertook his trade mark comparisons.

68 First, his Honour’s comparisons proceeded from an incorrect starting point – namely, that a strong reputation existed in the AMH acronym (at least at all functional levels other than between domestic retailers and customers in respect of whole primal cuts, where his Honour nevertheless found a sufficient reputation to exist). This led his Honour to conclude that, for the purposes of trade mark comparison, a strong reputation existed in the AMH word mark and, correspondingly, in the AMH device mark, and that this reputation should be taken into account in considering whether the competing marks were deceptively similar. This analysis was appropriate for a passing off case but, with respect, it was the wrong test to apply to a case based on trade mark infringement under s 120(1) of the Act. His Honour’s findings on reputation in the AMH acronym carried through and undoubtedly influenced his Honour’s comparisons of each AMG mark with each AMH mark.

69 Secondly and relatedly, his Honour’s focus on the reputation in the AMH acronym shifted attention from other features of the AMH device mark and other features of the AMG marks – we leave to one side for the moment the AMG word mark itself – which are significant and meaningful, and which ought to have been accorded due weight when conducting the comparisons for the purpose of s 120(1) of the Act. The consequence was to give the AMH acronym a predominating significance or influence it should not have been given.

70 By these observations, we do not wish to be taken as suggesting that the AMH acronym is not an important element of the AMH marks. Indeed, it is the sole feature of the AMH word mark. The point is that, when the influence of the substantial reputation in the AMH acronym is removed, the task of trade mark comparison, for the purpose of considering deceptive similarity in the context of trade mark infringement, is fundamentally different to the task that the primary judge actually undertook.

71 We now turn to compare each AMG mark with the AMH device mark. As we have said, the AMH acronym is an important element. But it is not so important that other visual features of the AMH device mark can be ignored. In short, the mark is not simply the presence of the letters “AMH”. Rather, it is a combination of features which must be considered as a whole. To start with, the letters “AMH” are rendered in a somewhat geometric form, as is the map of Australia on which the letters are placed. The impression is one of angularity in both the rendering of the letters and the rendering of the map. This angularity is also displayed by the ribbon device, assisted in part by the use of the chevron and the sharp vertical lines that provide the borders that are contiguous with the left and right extremities of the map. These lines also provide an inside border for the ribbon and are important in giving the mark its vertical orientation. The impression of the mark is one of a ribbon or, perhaps, a seal of approval in vertical orientation bearing the letters “AMH” in a particular stylised, upper case form.

72 The AMG marks are quite different. We deal firstly with the AMG device mark itself. It is noticeably different from the AMH device mark. The appellant’s name is an integral part of the mark. As we have said, it is reasonably prominent and conspicuous when considered against the mark’s other elements and provides a direct reference to the appellant, not an allusive reference to the respondent. In common with the AMH device mark, the AMG device mark adopts an acronym set on a stylised map of Australia. But that is where the commonality ends. The rending of the AMG acronym is in lower case and presented in cursive script. The last letter of the acronym is unambiguously the letter “g”. Even the most casual observer would see the letters, so presented, as a direct reference to the name appearing under the map. The map itself is presented consistently with the stylised, flowing rendition of the acronym. Further, the AMG device mark possesses a horizontality created by the width of the rendering of the stylised map of Australia and the positioning of the name which can be taken as describing two horizontal lines, one line comprising the word “Australian” and the second comprising the words “Meat Group”.

73 We have described some of the more prominent visual features of the two marks only for the purpose of noting their common elements and their differences. In doing so, we are conscious that the comparison relevant to the present appeal is not that undertaken to determine substantial identity (a side by side comparison) but deceptive similarity (impression based on recollection). Allowing for the possibility of imperfect recollection, we are not persuaded that the AMG device mark is deceptively similar to the AMH device mark. The impression created by each mark is substantially different and likely to be enduring. We take into account the fact that, on his Honour’s findings, the transactions in which the marks are used take place in a market where the buyers are likely to bring to bear an inquiring mind in respect of purchases of some considerable value. The adoption of a map of Australia is common to the two marks, but of no particular significance in the overall scheme of things. The evidence shows that other entities involved in the Australian meat industry have adopted logos which include a stylised map of Australia. The stylised rendering of the map is, in any event, significantly and obviously different in each mark. As we will later explain, the adoption of acronyms is also common, but here the two acronyms are also different and represented in stylistically different forms. Further, the AMG device mark, considered as a whole, has none of the geometricity or angularity of the AMH device market, considered as a whole. It does not have the AMH device mark’s vertical orientation. It does not convey the impression of a ribbon or a seal of approval.

74 We reach our conclusion not simply on the different visual impressions created by the two marks. If an observer were to describe each mark verbally by reference to its acronym, the marks would be described differently. The primary judge accepted that each acronym would be treated as an initialism. The significance of this difference in verbal description was somewhat subordinated by his Honour because of his reliance on the strong reputation in the AMH acronym as a source of confusion. When the influence of that consideration is removed, the marks are plainly distinguishable as a matter of verbal description. Further, in the case of the AMG device mark, some participants in the market would simply describe it by reference to the name “Australian Meat Group” rather than the acronym AMG.

75 Before leaving the primary judge’s comparison of the AMG device mark with the AMH device mark, we note his Honour’s finding that the AMG device mark might be seen as a more modern version or variant of the AMH device mark: see at [279(26)]. This finding was made in the context of considering transactions between retailers and consumers in respect of whole primal cuts. The evidence discloses that the mark in fact used in respect of these transactions is the AMG solid mark, not the AMG device mark: see at [18]–[19]. Further, in making this finding, the primary judge concentrated on “a bag marked with a stylised map of Australia enclosing a white field with ‘AMG’ in the middle of the map”. However, this ignores the prominent display of the name “Australian Meat Group” as it appears in the heavy horizontal band on which the stylised map sits. We do not think that this distinguishing feature would be ignored by purchasers at the retail level. As a matter of trade mark comparison, we are satisfied that consumers would see the AMH device mark and the AMG solid mark as distinctly different marks. The only reason to suppose the possibility of confusion is the assumption that a reputation exists in the AMH device mark by virtue of the letters “AMH” which, when carried over by consumers to the AMG solid mark, is sufficient to overbear their cognition of other features of the AMG solid mark including, importantly, the name “Australian Meat Group”. Once again, this consideration is relevant to a case based on passing off, but not to a case based on alleged infringement under s 120(1) of the Act.

76 As to the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark, we have already noted that his Honour treated these marks as characterised by the AMG device mark. There is no doubt that the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark incorporate the AMG device mark. But each is much more than simply an iteration of the AMG device mark. In short, we do not agree that each mark is “characterised” by the AMG device mark. When each mark is considered as a whole, it contains numerous other elements which set it apart from the AMG device mark, and from each other, notwithstanding points of similarity.

77 The point of present significance is that, just as the AMG device mark is not deceptively similar to the AMH device mark, so too the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark are not deceptively similar to that mark. What these marks do have in common with the AMH device mark is a vertical orientation. They also contain a stylised acronym on a stylised map of Australia. But their overall visual features are so different to the AMH device mark that we do not think that either mark could be said to be the source of trade mark confusion when compared with the AMH device mark. Further, their verbal description would include “Angus Beef” or “Premium Angus Beef” (in the case of the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark) and “Southern Ranges” or “Southern Ranges Platinum” (in the case of the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark), quite apart from the name “Australian Meat Group” or the AMG acronym verbalised as an initialism. Once again, the primary judge’s contrary conclusion was grounded on the substantial reputation he found to exist in the AMH acronym.

78 We are also of the view that the AMG word mark is not deceptively similar to the AMH device mark. What the two marks have in common is two out of three letters of an acronym. However, this is not sufficient to treat the AMG word mark as deceptively similar to the AMH device mark. First, the AMH device mark is a composite mark. As we have previously emphasised, it is not simply the letters “AMH”. Its other elements, in combination, cannot be ignored. To consider the mark otherwise would be to extend its scope well beyond the monopoly that has been granted to the respondent by registration. Secondly, as a matter of impression, the acronyms are different and distinguishable, not only visually but also by verbal description as initialisms. In stating this, we take into account the level of discernment which his Honour found to be present in the transactions in which these marks are used. Thirdly, the primary judge’s contrary conclusion was, once again, grounded on the substantial reputation he found to exist in the AMH acronym. To import this consideration into the analysis to undertake an erroneous comparison for the purposes of s 120(1) of the Act.

79 We now turn to compare the AMG marks with the AMH word mark. One feature possessed by the AMG device mark and each of the other composite marks (the AMG solid mark, the AMG Premium Angus Beef mark and the AMG Southern Ranges Platinum mark) is the name “Australian Meat Group”. Once again, this name is a direct reference to the appellant, not an allusive reference to the respondent. Further, the AMG acronym present in each mark would be understood in the context of, and seen as a reference to, the “Australian Meat Group” name. These are important and conspicuous features of the composite marks. They serve to distinguish these marks from the AMH word mark. Their significance is such that we do not accept that they would be ignored or overlooked by buyers in the relevant market. We are not persuaded therefore that these marks are deceptively similar to the AMH word mark.

80 This then leaves the AMG word mark compared to the AMH word mark. This is the high point of the respondent’s case on trade mark infringement.

81 In comparing these marks, it is important to bear in mind the scope of the monopoly afforded by registration of an acronym. The world of commerce is conditioned to the use of acronyms. The evidence before the primary judge shows persuasively that the supply of meat products in Australia is certainly part of that world. Some acronyms become words which enter the vernacular in their own right. The word “radar” (“radio detection and ranging”) is often cited as an example of that phenomenon. Some acronyms are more narrowly characterised as initialisms, as is the case here with the letters “AMH” and “AMG”. Quite often one acronym or one initialism will bear a number of meanings, with the relevant meaning conveyed only by the context in which the initialism is used. For example, the initialism BBC will have a different meaning in Australia depending on whether the context is, say, the supply of broadcasting services or the supply of hardware: see, for example, the observations of the Hearing Officer in ATP Tour, Inc v Australian Tennis Professional Coaches Association Ltd [2001] ATMO 99. Another example is the acronym APRA which, in Australia, can mean (at least) the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, the Australasian Performing Right Association, or the Australian Professional Rodeo Association, and perhaps many more entities or things. Once again, the context of use is important. The pool of acronyms and initialisms is more limited than the reservoir of words from which they are sourced. This is particularly so where one of the letters of the acronym or initialism is derived from a commonly-used geographic indicator, such as Australia.

82 At the stage of trade mark registration, a number of issues can arise with respect to marks that are acronyms. One issue that can arise is whether the mark is capable of distinguishing the goods or services for which registration is sought: see s 41 of the Act; see also Registrar of Trade Marks v W & G Du Cros Ltd [1913] AC 624. The concern in this regard is that the creation of a statutory monopoly in combinations of mere letters of the alphabet will interfere with the common right of traders to make honest use of the same letters as part of the stock of ordinary language. The Registrar’s practice is that trade marks consisting of three or more letters are prima facie capable of distinguishing because there is likely to be less need for the use by traders of these combinations. However, these combinations will lack inherent adaptation to distinguish if they are well known acronyms or abbreviations used on or in relation to the goods and/or services for which registration is sought: Trade Marks Office Manual of Practice and Procedure, Part 22, para 8.3.

83 Another issue that can arise is whether the mark applied for is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, an acronym that is a prior registered mark or a mark whose registration has been sought with an earlier priority date than the mark in question: see s 44 of the Act. When this question arises, the Registrar proceeds on the basis that the Australian public is quite used to acronyms in the market place and is used to relying on small differences to distinguish between them. For this reason, closer similarities than normal are expected and tolerated for acronyms, in the absence of demonstrated bad faith: ATP; Professional Golfers’ Association of Australia Ltd v Ladies Professional Golf Association (2004) 61 IPR 206 at [17]; CMA CGM v CMA Corporation Ltd [2011] ATMO 95; 95 IPR 593 at [25]–[30]. Although an allegation of bad faith was raised in the present proceeding against the appellant with respect to its adoption of the AMG marks, the allegation was abandoned during the course of the hearing before the primary judge: see at [99].

84 No question of validity arises in the present appeal with respect to registration of the AMH word mark. However, s 44 of the Act raises the very same trade mark comparison that is required under s 120(1).

85 There appears to be no dispute that the letters “AM” in the acronym AMH would be understood in the Australian meat industry as an obvious contraction of “Australian meat”. This proposition was put to, and accepted by, the respondent’s Chief Executive Officer, Mr Eastwood. This is a relevant consideration when considering the question of deceptive similarity in the present case because it affects the significance and weight to be given to the element “AM” that is found in each of the competing marks. The evidence shows that, in the Australian meat industry, acronyms incorporating the letters “AM” are common.

86 For example, Mr Eastwood accepted that AMPC is the acronym for the Australian Meat Processor Corporation. The AMPC is a rural research and development corporation that supports the red meat processing industry in Australia. Its board includes representatives of the respondent and many other companies that process meat in Australia and compete with the respondent. It has 105 members. Mr Eastwood also accepted that AMIC is the acronym for the Australian Meat Industry Council. AMIC represents retailers, processors, exporters and smallgoods manufacturers in the post-farm-gate meat industry. The respondent was a member of AMIC until about three or four years before the commencement of the hearing before the primary judge. Mr Eastwood further accepted that the acronym AMIEU would be understood by him as referring to the Australian Meat Industry Employees Union (we note that this organisation is, in fact, titled the Australasian Meat Industry Employers Union).

87 It may be accepted that these acronyms have more than the three letters comprising the competing marks. Nonetheless, they demonstrate the proposition that the letters “AM”, in the context of the Australian meat industry, are likely to be understood as denoting the words “Australian meat”. Further, they demonstrate that Mr Eastwood’s concession with respect to the meaning that would be given to those letters in the AMH acronym was well-made.

88 In our respectful view, the primary judge placed too much significance on the “AM” component of the AMH word mark and the AMG word mark when concluding that they were deceptively similar marks, particularly in discounting the significance to be attached to the distinguishing last letters “H” and “G” respectively. Further, each mark must be compared as a whole. When this is done, there is an undeniable difference between the AMH word mark and the AMG word mark both visually and when described verbally as initialisms. When these considerations are coupled with an appreciation that the trade in question is characterised by the discernment and the inquiring minds of the traders concerned, and that the purchases in question are of some significance in terms of volume and value, we are not persuaded that, in use, the AMG word mark is deceptively similar to the AMH word mark. The primary judge erred in reaching the opposite conclusion. This error was the product of his Honour’s reliance on the strong reputation he found in the AMH acronym.

89 It follows from these findings that Ground 8 of the appeal is established. It is not necessary for us to descend to the subsidiary grounds on which Ground 8 is based. However, it will be apparent from our reasons that we accept the correctness of a number of the propositions contained in those grounds.

ORDERS

90 For these reasons, the appeal should be allowed; Orders 1, 2 and 3 of the orders made by the primary judge on 11 December 2017 should be set aside; the order of the Court made on 22 December 2017 should be set aside; the proceeding should be dismissed; the undertaking given by the appellant to support the stay granted by the primary judge on 21 December 2017 should be discharged (the stay falling with the setting aside of the orders made 11 December 2017); and the respondent should pay the costs of the appeal.

91 In light of the considerations at [45] above that may attend the question of costs of the trial, we would hear the parties on the costs of the trial.

I certify that the preceding ninety-one (91) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop and Justices Besanko and Yates. |

Schedule A

Schedule B1

Schedule B2

Schedule B3

Schedule B4