FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2018] FCAFC 155

ORDERS

UNIQUE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE PTY LTD Appellant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION First Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Declaration 1 of the orders of Perram J made on 8 November 2017 be set aside.

3. The first and second respondents pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.

4. The cross-appeal be dismissed with costs.

5. The matter be remitted to the primary judge for determination of the costs of the trial and for hearing as to further remedy.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 This appeal concerns the unconscionability provisions in s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), and in particular what it was necessary for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to prove in order to make out a case of a contravention or contraventions of s 21(1) by the appellant, Unique, based on allegations of a “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour” as those terms are used in s 21(4) of the ACL. The primary judge’s reasons for judgment on the alleged contraventions of the ACL can be found in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Unique International College [2017] FCA 727.

2 We have concluded that there was an insufficient evidentiary basis before the primary judge to support the findings and declaration his Honour made that Unique engaged in a system of conduct or a pattern of behaviour in connection with the supply of online vocational education courses to consumers, and that the system or pattern of behaviour was unconscionable. Unique’s appeal must be allowed. The ACCC’s cross-appeal should be dismissed.

3 That conclusion as to the lack of evidentiary base for a system or pattern of behaviour case is to be contrasted with the findings that were clear, and uncontested on appeal, that the appellant had engaged in unconscionable conduct in its dealings with a number of individuals.

Some matters of background

4 Before outlining the facts of the case, it is appropriate to commence with a brief summary of the background to the courses offered by Unique. This background is relevant to some of the issues on the appeal, and to the question of what in Unique’s conduct could properly be identified as unconscionable on the evidence.

The Federal Government’s changes to the higher education system and the introduction of online courses

5 The Commonwealth introduced what is known as the “VET FEE-HELP Scheme” in 2007. The scheme has been amended from time to time. The acronym stands for the Vocational Education and Training Fee Higher Education Loan Program. Broadly, from 2009, the scheme provided for the Commonwealth to pay, in full, tuition fees for any approved course, on the basis that the amounts paid would be treated as a loan to the student, such loan to be repayable through the taxation system once a student earned above a specified income threshold. Relevantly to the period concerning the ACCC’s allegations against Unique, that income threshold was set at about $50,000 per year. Approved course providers needed to have arrangements with an institution that offered a “higher education award” (such as a degree). That is because the scheme was designed to be a pathway into further higher education.

6 In early 2012, the Commonwealth foreshadowed substantial reforms to the VET FEE-HELP scheme. Those reforms were implemented through legislation enacted in the second half of 2012. The explanatory memorandum to the Higher Education Support Amendment (Streamlining and Other Measures) Bill 2012 (Cth) stated:

The low take-up of VET FEE-HELP is an equity issue. People from identified demographic groups have a lower participation rate in education and training. These groups include Indigenous Australians, and people from a non-English speaking background, with disability, from regional and remote areas, from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and people not currently engaged in employment. Increased student take-up of VET FEE-HELP is key to lifting VET participation amongst these groups nationally.

7 One of the changes made by the 2012 legislation was to remove the need for a course to count towards a course at a higher education institution. This was consistent with the rationale for the changes expressed in the extrinsic material we have quoted above. Participation in vocational training was seen as an end in itself, and not only a pathway to higher education. Indeed, a media release from “Skills Australia” in May 2011 described the changes as a “sweeping overhaul of the country’s vocational education and training (VET) system in order to help raise productivity, and address skills challenges that threaten future economic growth and prosperity”.

8 The features of the policy that should be borne in mind in appreciating, and indeed not making unwarranted assumptions about, the evidence in this case were that (a) there was a decoupling of the courses from established tertiary institutions; (b) there was a focus of the policy on those from low socio-economic backgrounds, Indigenous Australians, people from remote and regional backgrounds, and the unemployed; (c) the courses could be delivered by the internet; (d) upon sign up the provider would be entitled to payment of the course fee from the Commonwealth; and (e) upon that payment it was the student who was liable to the Commonwealth for repayment of the tuition fee and a 20% loan fee, but with repayment only commencing with an income of above about $50,000 per annum.

9 Another aspect of the policy in practice under the scheme was that each student had an account with the Commonwealth which had a lifetime cap of $98,000. Thus, any taking up of the assistance diminished the likelihood of future assistance being available.

Unique’s vocational education business

10 Relevantly, Unique was registered as a Registered Training Organisation by the NSW Vocational Education and Training Accreditation Board in October 2007. Initially it offered face-to-face vocational courses from its premises in Granville, NSW. Between 2008 (the end of the first financial year during which Unique offered vocational education courses) and 2013 (the end of the financial year after the changes to VET FEE-HELP were introduced), Unique’s enrolment numbers were modest, ranging between 177 in 2008 and 789 in 2012, and reducing slightly to 631 in 2013.

11 During this period from 2008 to 2013, Unique arranged course credit transfer arrangements with a number of tertiary institutions, but was not able to obtain registration for VET FEE-HELP for its courses. All this changed, however, with the changes to the policy and Unique’s registration. By the end of 2013, Unique had secured registration of its four vocational education training courses under the VET FEE-HELP scheme, which was made easier since those courses did not need to be eligible to count towards higher education courses, so there was no need for arrangements with higher education institutions to accredit Unique’s courses, as there had been in the past. This was, we accept, how the new scheme was intended to operate.

12 From 1 January 2014, all courses offered by Unique were offered by way of online study. The courses relevant to this case (those eligible for VET FEE-HELP) were a Diploma of Salon Management; a Diploma of Management; an Advanced Diploma of Management; and a Diploma of Marketing.

13 It was not any part of the case made against Unique that any of these courses was inadequate or inappropriate.

14 It was not in dispute before the primary judge that Unique offered incentives for students to enrol in its courses. For example, one of its brochures in evidence described the incentives in the following terms:

Enroll now and get a free I-pad or Laptop or $1,000 ($1,000 to buy i-pad or laptop of your own choice) (From 1 Jan 2014 till 30 Dec 2014)

Enroll in any of our Diploma or advanced Diploma level courses and get first installment of special offer (Either an I-pad or a laptop or $500*) at commencement and get second installment of special offer (Either an I-pad or a laptop or $500*) at mid point. Ask us for more details.

15 Unique’s case, and its evidence at trial, was that it had been told by various sources including the Department of Education and Training (as it is now described), that the offering of these incentives was permissible, and not in contravention of any standards applicable to Unique as an approved provider, nor in contravention of the ACL.

16 The offer, and provision, of “free” iPads and laptop computers was to feature prominently in the ACCC’s case and in the primary judge’s findings. The evidence was, and the primary judge found, that after 1 April 2015 the incentive programs were formally closed by Unique due to the change in Federal Government policy on the offering of such incentives and computers were not given away, but lent to students. However, during at least one enrolment session after this date (at Bourke), the primary judge found laptops were still being discussed as if they were being given away. Given the absence of any evidence from Unique that it sought the return of any laptop from the very many students who did not complete (or even commence their courses), the primary judge found that the laptop incentive program in substance continued.

17 Unique had also engaged in “referral” practices since it started offering VET courses in 2008. These referral practices involved students being paid money if they referred another student to Unique’s courses, and that other student enrolled, and stayed enrolled, past the census date. This referral practice continued into the time when Unique was offering other incentives to prospective students. Unique also paid a commission to its staff when students were enrolled.

18 As we have noted, from 1 January 2014, the courses offered by Unique under VET FEE-HELP were all online courses; they were no longer tied to delivering learning at its Granville premises. Consequently, Unique could recruit and reach students in a very wide geographical area. Much of the evidence before the primary judge concerned recruiting and enrolment practices at a range of locations across New South Wales. The spread of Unique’s enrolment practices outside New South Wales, and the primary judge’s extension of declaratory relief to places outside New South Wales, forms part of Unique’s grounds of appeal.

19 Nevertheless, it is not in dispute that Unique’s enrolments jumped markedly after it came to operate under the changes that had been made in 2012 and after it became registered under the new VET FEE-HELP scheme. In 2014, 3,251 students were enrolled. In 2015, 4,677 students were enrolled, with corresponding increases in revenue as set out in the following table, compiled from the tables at [11] and [13] of the primary judge’s reasons:

Year | Enrolments | Revenue | Net Profits after tax |

2013 | 631 | $1,702,612 | $40,301 |

2014 | 3,251 | $15,942,949 | $8,214,031 |

2015 | 4,677 | $56,183,632 | $33,779,726 |

20 That revenue and consequent profits were, of course, obtained from the Commonwealth in accordance with the operation of the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

The ACCC’s case at trial and the primary judge’s findings in summary

The ACCC’s case as pleaded

21 The case of the ACCC concerned contraventions of the ACL in connection with the supply of vocational education courses to consumers in relation to individuals, and in relation to a system. The period of time during which the ACCC alleged there had been contraventions by Unique ran from 1 July 2014 to 30 September 2015.

22 There were three causes of action, all contended to arise out of the same factual substratum:

(a) contraventions of ss 18 and 29 of the ACL in relation to misleading or deceptive conduct;

(b) contraventions of ss 74, 76, 78 and 79 of the ACL in relation to unsolicited consumer agreements; and

(c) contraventions of s 21 of the ACL in relation to unconscionable conduct against the consumers, not against the Commonwealth.

23 The ACCC was successful to a large extent on each cause of action. Unique’s appeal involves only part of the third cause of action, contraventions of s 21 of the ACL.

24 The primary judge emphasised (at [17]) that the ACCC’s case did not involve allegations about the improper use of Commonwealth funds:

But the Applicants’ case is not a case about the misappropriation of Commonwealth funds, nor is it a case, despite the way it was sometimes depicted outside the courtroom, about rorting by Unique of a Commonwealth scheme. The Applicants’ case was, from beginning to end, a case alleging the unconscientious exploitation and misleading of students. Such a case is by no means the same as a case which directly alleges that the Commonwealth has been defrauded. It is quite possible for the rorting of a scheme to happen without exploitation of students. It is also equally possible for exploitation of students to occur in the absence of rorting. …

25 The primary judge noted the ACCC’s unconscionability case (the third cause of action) had two distinct elements: one focused on Unique’s enrolment processes (set out in Part 2 of the Amended Statement of Claim dated 9 May 2016 (ASOC)), and the other (set out in Part 3 of the ASOC) focused on Unique’s behaviour towards six named consumers. We shall describe these as the “system case” and the “individual consumer case”. The appeal is only in relation to the system case.

26 Whilst we do not cavil with the primary judge’s comments in [17] of his reasons (set out at [24] above), the assessment of unconscionability in relation to the consumers is to be made in the context of the scheme and Unique’s obvious responsibilities under it. Such consideration may be important in understanding the full factual context in which unconscionability is to be judged.

The individual consumer case as pleaded

27 The individual consumer case can be briefly summarised, as it is not directly in issue on the appeal. However, an understanding of how that case was put at trial by the ACCC is necessary in order to understand the relevance of the categories of evidence which were adduced and relied on, and how that evidence did or did not overlap with the evidence relied on for the system case. As the primary judge explained (at [26]-[28]), the individual consumer case encompassed three sets of allegations, namely that:

(a) Unique engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to five of the six individual consumers by not informing them its courses were not free and that they would be left with a debt to the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

(b) In conducting its enrolment processes, Unique behaved unconscionably towards the consumers because it failed to explain the nature of what they were signing up to in circumstances where there were “elements of disadvantage” in relation to each of the individual consumers, and Unique adopted an “aggressive” enrolment process.

(c) Unique had sought to have the six individual consumers enter into unsolicited consumer agreements without complying with the additional requirements of Division 2 of the ACL. As the primary judge noted, this conduct was also relied on as an indicator of unconscionability.

28 These cases were substantially made out, from which there was no appeal.

29 The six individual consumers referred to in the pleadings, in chronological order of the enrolment sessions held, were:

(a) Ms Natasha Paudel, who enrolled in the session held at Walgett on Friday, 10 October 2014 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer E);

(b) Ms Kylie Simpson, who enrolled in the session held at Tolland, Wagga Wagga on Monday, 30 March 2015 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer A);

(c) Mr Tre Simpson, who enrolled in the session held at Tolland on Monday, 30 March 2015 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer F);

(d) Ms Jaycee Edwards, who enrolled in the session held at Bourke on Wednesday, 10 June 2015 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer B);

(e) Ms Fiona Smith, who enrolled in the session held at Bourke on Wednesday, 10 June 2015 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer C); and

(f) Ms June Smith, who enrolled in the session held at Bourke on Wednesday, 10 June 2015 (referred to in the ASOC as Consumer D).

The system case as pleaded

30 The system case should be explained both by reference to the primary judge’s description, and to the pleadings. The system case was contained in paras 21 to 29 of the ASOC.

31 Paragraph 21 set out the ACCC’s allegations about Unique’s “process for marketing Unique courses, and enrolling consumers in Unique courses”. The ACCC alleged that process had eleven features or categories of conduct:

(a) targeting particular locations, including rural and remote towns, Indigenous communities and areas with significant populations of people with low socio-economic status. All the locations set out in the particulars were in New South Wales. They were not limited to Walgett, Wagga Wagga and Bourke and also “included” Bankstown (in Sydney), Boggabilla, Brewarrina, Emerton, Moree, Taree, Toomelah and Granville;

(b) directing its employees to market to and enrol consumers in these locations;

(c) having its employees visit these locations with “boxes of laptop computers to give to consumers” who signed up for a Unique course;

(d) marketing at these locations including by way of calling on consumers in their homes and “group marketing” in private homes for the purpose of enrolling consumers;

(e) employees representing to consumers, both at these locations and at Unique’s campus in Granville, that in order to receive a free laptop, they needed to sign up to a course, and provide identification and personal information;

(f) employees representing to consumers, both at these locations and at Unique’s campus in Granville, that the courses were free, or free unless their income was, or reached, an amount they were unlikely to earn on completion or at all;

(g) giving free laptops to consumers who signed up;

(h) making incentive payments to its employees based on the number of consumers an employee enrolled; and

(i) using (alleged over three sub-paragraphs) two kinds of forms (a VET FEE-HELP form and a student enrolment application/agreement), taking the personal identification and information provided by the students and having the consumers sign the two forms for the purpose of entering the consumers into an agreement with Unique and requesting VET FEE-HELP from the Commonwealth, which would constitute an agreement between the Commonwealth and each consumer.

32 Notwithstanding the terms of para 21, paras 22 and 23 of the ASOC also concerned the enrolment process. Paragraphs 21, 22 and 23 must be read together.

33 Paragraph 22 set out eight alleged failures of Unique, through its employees, during the enrolment process:

(a) to ascertain whether consumers had the capacity to pay the course fees;

(b) to explain, adequately or at all, the VET FEE-HELP scheme, the nature of a student’s obligations under that scheme and that they would have a debt to the Commonwealth after the census date for each unit of the course;

(c) to ascertain if consumers intended to undertake the course;

(d) to ascertain whether or not consumers understood they were enrolling in a course;

(e) to ascertain if consumers had read and understood the two forms they were presented with;

(f) to explain, adequately or at all, what obligations consumers were assuming by signing the forms;

(g) to ascertain whether consumers understood their obligations in signing the two forms; and

(h) to provide consumers with copies of the two forms they had signed.

34 Paragraph 23 pleaded the consequences of the features or aspects of the enrolment process pleaded in paras 21 and 22. The consequences pleaded in para 23 focused upon attributes consumers were alleged to have had which (it can be inferred, and this allegation is made express in para 29) made them vulnerable. The attributes in para 23 were that the consumers Unique enrolled:

(a) did not actually understand they had been enrolled in a Unique course;

(b) could not read or otherwise understand the nature of the courses (including that they were online courses), and the nature of their obligations in agreeing to accept VET FEE-HELP assistance; and

(c) could not access and use an email address, a computer or the internet, and had inadequate numeracy and literacy skills so that they were not capable of undertaking and completing the course they had been enrolled in.

35 For present purposes, what is important to note is that the ACCC’s allegations in paras 21-23 were highly fact specific, as to the way Unique conducted its enrolment processes; what its employees failed to do; and what were the vulnerabilities of the consumers said to have been targeted by Unique.

36 It is also important to observe that at this point in the pleading there was no express allegation that Unique through its employees systematically failed to ascertain whether the consumer was suited to the course and the course to the consumer, though some of the specific allegations could be seen to relate to such a more general allegation.

37 The system case pleading continued in paras 24 and 25 with allegations concerning the consumer’s ongoing exposure to VET FEE-HELP debt and the receipt by Unique of funding from the Commonwealth. At para 26 of the ASOC, the ACCC alleged that the reason, or motivation, for Unique’s conduct was to maximise the number of consumers enrolled and receiving VET FEE-HELP, so as to maximise its revenue stream from the Commonwealth.

38 The allegation in para 26 carried with it an implied assertion that maximisation of revenue was at the expense of ensuring as far as possible that suitable people were being signed up for suitable courses.

39 Paragraph 27 of the ASOC alleged that the conduct concerning the six individuals (detailed at paras 31 to 142) occurred in the course of implementing the system pleaded in paras 21 to 26.

40 The ACCC alleged (at para 28 of the ASOC) that the consumers incurred three kinds of loss and damage as a result of Unique’s conduct:

(a) incurring a debt or potential debt to the Commonwealth in respect of a course that was unsuitable for them and which they were unlikely to be capable of completing;

(b) anxiety and distress from an “unexpected debt”; and

(c) reducing the entitlement of a consumer to further VET FEE-HELP in the future (assistance is subject to lifetime caps for each individual).

41 At para 29 of the ASOC, the ACCC alleged the unconscionability of Unique’s conduct could be characterised in six ways:

29.1. Unique targeted vulnerable consumers in marketing and enrolling consumers in its courses;

29.2. Unique took advantage of its superior bargaining position relative to consumers, including vulnerable consumers, in order to enrol them in its courses;

29.3. Unique used unfair tactics, including offering inducements, in order to enrol consumers in its courses;

29.4. Unique gave consumers, including vulnerable consumers, misleading information, or failed to adequately disclose information regarding the nature of its courses;

29.5. Unique gave consumers, including vulnerable consumers, misleading information or failed to adequately disclose information in relation to their obligations if they received VET FEE-HELP assistance, including that they would incur a debt to the Commonwealth after the census date for each unit of the course, and the amount of the debt; and

29.6. consumers were enrolled in courses that were not suitable for them, and which they were unlikely to be capable of completing, having regard to their limited formal education, limited literacy and numeracy skills, and their lack of computer skills or access to email or internet connections at home.

42 It is important to note the terms of para 29.6, which drew out some aspects of the pleading which were hitherto less than fully explicit. The various inadequacies in what was alleged to have been done and not done can be seen to be worthy of criticism if persons are being targeted because of their vulnerable qualities, using unfair tactics and misleading or inadequate information to sign them up for courses which were unsuitable for them, which they would likely be incapable of completing and which would saddle them with a lifetime of debt, all in aid and furtherance of a purpose of maximising Unique’s monetary revenues from the Commonwealth. The pleading has a certain deconstructed and particularised character to it, in circumstances where the unconscionability and the system can be better understood when described more coherently or holistically. The risk of deconstruction and particularisation is that it can lose the holistic interrelationship between all the factors, both as they affect the individuals and the system or pattern of behaviour. For instance, the targeting of the poor, ill-educated and socially and economically disadvantaged, whether these people are Indigenous, migrant or a member of some other category, was (when looked at alone) part of the aim of government policy. But it is an important and serious aspect of a case of unconscionability if such persons are targeted because of the ease of persuading them to sign up to courses for which they are unsuited by enticing them with lures of gifts and by misleading them, not so that they may be given the opportunity of obtaining a useful education, but so that Unique can maximise its revenue from the Commonwealth.

43 We will return to this question of the nature of unconscionability later in the discussion of the evidence. That is, the whole, rather than the deconstructed and particularised, nature of the concept.

44 Nevertheless, the declaration sought in relation to the system case, though deconstructed in its terms, sought to encapsulate the whole idea, as follows:

1. A declaration that during the period from July 2014 to September 2015, Unique, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct in connection with the supply or possible supply, or marketing of the supply, of vocational education courses (courses) to consumers, that was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable within the meaning of s 21 of the ACL, by:

1.1 targeting particular locations, including rural and remote towns and indigenous communities and areas with significant populations of low socio-economic status (locations), to market its courses to consumers and to enrol consumers in its courses;

1.2 directing its sales representatives to market its courses to consumers at the locations, including by having the sales representatives call on consumers at their homes and also conduct group marketing sessions in private homes for the purpose of enrolling consumers in its courses;

1.3 its sales representatives representing to consumers that in order to receive a free laptop computer they needed to sign up to a Unique course and provide identification and personal information;

1.4 its sales representatives representing to consumers that its courses were free, or were free unless the consumer’s income was in an amount which they were unlikely to earn on completion of a course, or at all;

1.5 offering inducements to consumers to enrol in its courses, including making cash payments to consumers and providing consumers with free computers and laptops;

1.6 providing financial incentives to its sales representatives in order to maximise the number of consumers enrolled by them in its courses;

1.7 its sales representatives failing to explain or adequately explain to consumers:

1.7.1 the nature of the Commonwealth VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme; or

1.7.2 the existence and nature of their obligations if they received assistance under the VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme; or

1.7.3 that they would have a debt to the Commonwealth after the census date for each unit of any course in which they were enrolled, and the amount of the debt;

1.8 enrolling in its courses consumers;

1.8.1 who could not access or use an email address;

1.8.2 who could not use a computer;

1.8.3 who could not use and did not have access to the internet;

1.8.4 who did not have adequate literacy or numeracy skills;

1.8.5 for whom the courses were not suitable, and which they were unlikely to be capable of completing.

1.9 Engaging in this conduct to maximise the revenue derived by Unique from payments to it from the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme.

45 Relevantly for the appeal, the primary judge also noted at [29] of his reasons that:

An interesting aspect of the case alleged in relation to the individual consumers is that it relied, in part, on the Applicants’ more general system case pleaded in relation to Unique’s enrolment processes. This can be seen, for example, at paragraph 48 of the ASOC (in relation to Ms Kylie Simpson) which explicitly picks up the system case pleaded at paragraphs 21 and 22. A related curiosity is that the system case at paragraph 27 of the ASOC alleges that the individual consumers’ cases are to be seen as manifestations of the system case. It is possible this results in some circularity. However, it is best not to be distracted by these pleading issues in the abstract. …

46 As we have already noted, the ACCC’s pleading at para 27 of the ASOC did indeed rely upon what was alleged to have happened in each of the individual cases as the conduct which occurred in the implementation of Unique’s enrolment process:

The conduct of Unique pleaded at paragraphs 31 to 142 below [the individual consumer case pleadings] occurred in the course of the implementation of Unique’s marketing and enrolment process pleaded at paragraphs 21 to 26 above [the system case pleadings].

47 It is this overlap in the way the case was framed, conducted and argued that appears to be responsible for the difficulties in identifying the evidentiary base for the system case.

The evidence at trial and the primary judge’s findings

48 The primary judge examined in great detail the evidence of each of the lay witnesses called on behalf of the ACCC, and then those called on behalf of Unique.

49 Five out of the six named consumers were called. Mr Tre Simpson was not called, but his grandmother, Mrs Margaret Simpson, was a key witness for the ACCC. Aside from Mrs Margaret Simpson, and the five individual consumer witnesses, two other lay witnesses were called: one was a former employee of Unique (Ms Penny Martin) and the other was Ms Larissa Kidwell.

50 Ms Kidwell’s evidence has a particular bearing on the system case. She gave evidence about an enrolment session at Taree on 27 November 2014: that is, towards the start of the period nominated by the ACCC as the period during which the alleged contravening conduct occurred and about six weeks after the events at Walgett that concerned Ms Paudel (one of the consumer witnesses). There were no allegations as part of the individual consumer cases about what happened at Taree. As the primary judge noted, Ms Kidwell’s evidence about what happened there was only related to the system case.

51 Ms Martin’s evidence was also relied on by the ACCC in its system case, and related to her attempts to contact, by email, the cohort of 80 students assigned to her after they had been enrolled in Unique’s courses. In general terms, her evidence (as accepted by the primary judge at [218] and following) went to the high proportion of “bounce backs” she received on emails she sent out, with the remaining students not responding at all, together with the action she took with Unique’s management to try to remedy, unsuccessfully, her inability to contact the students assigned to her.

52 The primary judge made a variety of findings, some favourable and some not, about the reliability of the applicant’s lay witnesses, in terms of their evidence about the circumstances of the enrolment sessions, what they were told and not told, the filling out of the forms and the like. It is unnecessary to work through those findings in any detail.

53 Unique made the forensic choice to adduce considerable evidence to rebut the ACCC’s allegations. That evidence included, but went well beyond, what occurred at the three locations on which the individual consumer case depended. Most of Unique’s evidence was rejected by the primary judge on the basis of the view his Honour took of the witnesses’ credibility and reliability. There was little in the way of corroborative evidence that his Honour was prepared to accept which added to the (small) quantity of direct evidence adduced on behalf of Unique that his Honour was prepared to accept. Thus, although there was a body of evidence adduced by Unique, in the end not much of it contributed to his Honour’s findings. On appeal, Unique did not challenge his Honour’s findings about its witnesses.

54 Unique called 14 lay witnesses, some of whom played a relatively minor role and some of whom played a central role in his Honour’s fact-finding. In the latter category, for example, were Ms Mandy Kang, Unique’s “student engagement manager” and the person who was at all or most of the enrolment sessions, Mr Amarjit Singh, the CEO of Unique, and Mr Manmohan Singh, a director of Unique and the father of Mr Amarjit Singh. The primary judge’s adverse credit and credibility findings against almost all of Unique’s witnesses were serious and involved a conclusion that he could not rely on anything they said. His Honour summarised his view about Unique’s witnesses at [643]:

I have concluded that all of Unique’s witnesses were, in various ways, unreliable and have indicated my unwillingness to act upon their evidence unless corroborated.

55 We return to this part of the primary judge’s fact-finding, his conclusions about what corroborative evidence existed, and what he was able to find, in our consideration of ground 1 of the appeal. However, as a general proposition, what can be said about the nature and state of the lay evidence at trial is as follows. The ACCC’s evidence was focused on what occurred at the locations where the six individual consumers were enrolled. The ACCC primarily relied on the evidence about what happened at these locations (Walgett, Tolland (Wagga Wagga) and Bourke) for its system case as well as for its individual consumer case. Only 2 witnesses (Ms Martin and Ms Kidwell) gave evidence about matters going to the system case outside those locations. Ms Martin’s evidence was in a small compass. Ms Kidwell’s evidence related to one further site. It was not disputed at trial that during the relevant period Unique enrolled over 3,600 students across more than 428 locations. The ACCC ultimately relied to a considerable extent on the primary judge’s adverse findings about Unique’s witnesses.

56 The ACCC adduced expert evidence from Professor Tony Vinson. He was described appropriately by the primary judge as a distinguished social scientist. At the time he provided his report, Professor Vinson was Emeritus Professor in the School of Social Sciences at the University of New South Wales and Honorary Professor in the Faculty of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney. Professor Vinson passed away while judgment was reserved.

57 There was no challenge at trial to Professor Vinson’s expertise nor to the quality of his evidence. Rather, Unique challenged at trial, and on appeal, the way in which the primary judge used Professor Vinson’s evidence in his findings. We discuss Unique’s arguments in more detail in our consideration of ground 2 of the appeal below. Professor Vinson’s expert report considered enrolment data concerning Unique’s students, alongside data sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. In the executive summary to his report Professor Vinson:

(a) identified the locations for enrolments by Unique during the relevant period by reference to postcode, and indicated where there were postcodes with 15 or more enrolments. Included in this data were locations in Queensland and Victoria, not only NSW;

(b) categorised which of these postcode locations would be described as “rural” or “remote”, and as an Indigenous community, and why;

(c) indicated what percentage of people in each location were Indigenous;

(d) classified each of the locations by reference to the ABS Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage, and then indicated the relative socio-economic disadvantage of the location where students who enrolled in Unique’s courses resided; and

(e) in relation to two specific areas studied (Wagga Wagga and Western Sydney) Professor Vinson concluded there was “clustered enrolment in sub-areas which also demonstrate higher levels of disadvantage relative to the broader location”.

58 In other words, Professor Vinson conducted a data analysis of postcode information about Unique’s student enrolments and used that to describe the socio-economic profile of the locations in which the students resided.

59 At [608], the primary judge described what Professor Vinson did as assessing the “socio-economic profile of Unique’s students” (our emphasis). With respect, that might be something of an overstatement, because none of Unique’s students outside the six individual consumers was specifically identified, and there was no evidence about their individual circumstances. In a way, this description by the trial judge reveals some of the difficulties which support Unique’s arguments on ground 2 of the appeal.

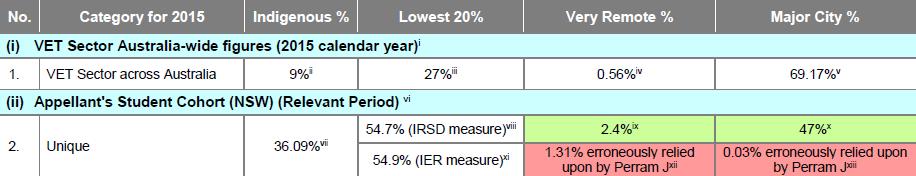

60 As the primary judge pointed out at [610] of his reasons, the ACCC used Professor Vinson’s evidence as the evidentiary foundation for submissions that students from remote locations, students from disadvantaged locations, and Indigenous students, were proportionally overrepresented in Unique’s student enrolments. In answer, Unique made two submissions in substance. First, the comparisons drawn from Professor Vinson’s evidence were the wrong comparisons, relying as they did on the general population rather than the overall VET population which Unique contended had proportionally higher numbers of Indigenous students, and students from disadvantaged and remote locations. Secondly, rather than providing any evidence of unconscionability (or a “system”), the proportions of students who were Indigenous, and/or from disadvantaged or remote locations, were a reflection of the student cohort the VET programs were designed and intended to reach.

61 The second of those submissions is a point well-made if proved “targeting” is said to be of itself indicative of unconscionable conduct. Without more, it may take the unconscionability case no further. However, that the government policy had the aim and purpose of running educational courses directed to marginalised or disadvantaged groups, does not make either irrelevant or virtuous the targeting of such groups if the conduct as a whole can be seen as the signing up of as many people as possible, to the maximum financial benefit of Unique, irrespective and uncaring of the suitability of the course for the consumer and the consumer for the course, using methods that involve misleading and inadequate information or other tactics that can be criticised.

The primary judge’s factual findings on the individual consumer case

62 From [33] to [640] the primary judge undertook a comprehensive and careful discussion of each witness’ evidence. From [641] to [709] the primary judge dealt with the individual consumer case. The primary judge structured his findings in this part of his reasons by reference to a heading entitled “Unique’s Usual Practice”, and then by reference to the four locations about which evidence had been given: Walgett, Tolland (a suburb of Wagga Wagga), Taree and Bourke.

63 It will be recalled that the evidence about Taree (from Ms Kidwell) was not adduced in support of the individual consumer case. It is unclear why his Honour considered it where he did in his reasons, since he expressly recognises at [690] that the evidence about Taree was only relied on to prove the system case. However, it may be explained by his Honour’s earlier reference, which we have quoted at [45] above, to the ACCC’s contention that evidence in the individual consumer case was relied on for the system case, so that his Honour considered it better to deal with all the location evidence in one place. The findings about “Unique’s Usual Practice” self-evidently related to the system case. Logically, of course, as concerning “usual practice” they also concerned the individual consumer case. After rejecting the evidence of all of Unique’s witnesses, all that the primary judge could take from the Unique witnesses was that there were short introductory sessions assisted with slides. This added little to the evidence concerning the individuals at Walgett, Tolland and Bourke.

64 In relation to each of the individual consumers at each of the locations, the primary judge made factual findings favourable to the ACCC’s case. In respect of Ms Paudel and Unique’s activities at Walgett (and reading his Honour’s reasons at [671] with the declaration subsequently made in the Court’s orders), it appears his Honour found Ms Paudel was not:

(a) told that she would have a contingent debt;

(b) given copies of the paperwork she signed;

(c) given a copy of the VET FEE-HELP booklet; or

(d) given written details of the courses.

65 However, the primary judge found that Unique’s conduct towards Ms Paudel was not unconscionable. This was so because the primary judge found that Ms Paudel was told that she would be left with a debt if she signed up and she understood this. She was also told and she understood that she could withdraw from the course before the relevant census date. She knew “what was going on”. See generally [759]. No case was made that she was deceived. On appeal, Unique relies on this finding to demonstrate how important the individual characteristics of each consumer can be in a case such as the present. We agree. We would add, however, that the fact that an individual was not deceived does not necessarily mean that conduct directed to that individual was not unconscionable. The conduct characterised as unconscionable may include unsuccessful, as well as successful, exploitation.

66 In respect of the enrolment session at Tolland, and the individual consumers Ms Kylie Simpson and Mr Tre Simpson, the primary judge made factual findings largely in accordance with the ACCC’s allegations, although the primary judge did not uphold all of the ACCC’s allegations in respect of Mr Tre Simpson. At one level for the purposes of this appeal, it is sufficient to extract his Honour’s overall conclusion about Unique’s conduct in relation to Ms Kylie Simpson and Mr Tre Simpson (at [689]):

I therefore conclude in both Tre and Kylie’s cases that the transaction was entirely exploitative. Unique received a large amount of money; Kylie and Tre received a lifetime contingent debt and an inexpensive device.

67 That said, it is illustrative of the seriousness of the behaviour and the clarity of the unconscionability in relation to the Simpsons to recite the findings at [686] to [688]:

I make these additional findings:

• no-one from Unique explained to Tre or Mrs Simpson the name of the courses involved;

• they were not asked if they had an internet connection at home;

• Unique’s employees did not explain to them the obligations arising from the forms;

• Unique’s employees did not make any attempt to discern whether Tre understood what he was signing and in Kylie’s case should have known that she did not;

• Unique’s employees did not give them copies of the forms they had completed;

• Unique’s employees did not tell them the cost of the course;

• Unique’s employees did not tell them they were incurring a substantial debt; and

• Unique’s employees did not tell them of their right to cancel before the census date.

I find that it was entirely obvious to the Unique employees present that Kylie was totally unable to understand what she was doing. I do not make this finding in relation to Tre. I do not find that Unique employees believed him sufficiently competent, only that the Applicants have not proved the contrary which was their onus.

On the other hand, I am satisfied that Unique’s employees were quite indifferent to Tre’s actual position. Actual and genuine inquiry on their part – as opposed to the form filling exercise embarked upon – would have revealed the problem soon enough.

68 In respect of the enrolment session at Bourke, and the individual consumers Ms Jaycee Edwards, Ms Fiona Smith and Ms June Smith, the primary judge again substantially accepted the factual allegations in the ACCC’s case, and his conclusion about what happened at Bourke was (at [709]):

I find that Unique’s behaviour towards each of Jaycee, June and Fiona was exploitative and I do not accept that Adell was merely there to provide passive assistance to Johanne. She was actively involved in the process. That process involved luring Jaycee, June and Fiona with laptops to derive significant revenues from the Commonwealth which then saddled them with a lifetime contingent debt. Nor was any given a copy of the agreement.

69 Once again, some of the early factual findings mark out with clarity the starkly exploitative behaviour towards the consumers and its clearly unconscionable character. It is sufficient to refer to [704] to [708]:

Although I have concluded that I should not rely upon Fiona’s account on its own, Fiona’s version in many ways resembles Jaycee’s version which I am willing to act upon. Both were speaking to Johanne. In her discussions with Fiona and Jaycee, Johanne:

• handed out a bundle of stapled forms which had X marked at various locations;

• told them to sign at those locations;

• took them through the forms quickly with no explanation;

• asked them to provide identifying information;

• told them that they did not have to complete the course if they did not want to;

• did not tell them about the contents of the course;

• did not tell them that they would be left with a debt;

• did not tell them that they could cancel their enrolment prior to the census date;

• did not give them a copy of the paperwork; and

• did not inquire as to the level of their education.

The forms were then signed and the laptops given to Fiona and Jaycee.

June did not speak with Johanne, but rather Adell.

June was shown a brochure but it was not explained to her. She was presented with the forms and told where to sign. They were not explained to her. She signed the forms because she believed she needed to do so to get a laptop. She was told the laptop was free. She understood that she was enrolling for some kind of course. No aspect of the VET FEE-HELP scheme was explained to her. She was not told she would be left with a debt. She was not told that she could withdraw from the course prior to the census date.

She was not told that she could ask them to leave the premises immediately. She was not given copies of the paperwork she had signed. June had no use for the laptop which must have been apparent to Adell. Nevertheless, she was signed up for the course. And this was so even though she had no internet connection.

70 The primary judge’s factual findings at [691] about Taree are properly to be seen as forming part of his findings on the system case, notwithstanding their location in the individual consumer case part of his reasons. Those findings were as follows:

As I have already indicated at [227], I accept Ms Kidwell’s account of the meeting at Taree. I therefore accept that Ms Kang’s ‘spiel’ went for five minutes and omitted any explanation of the VET FEE-HELP arrangement or the right to withdraw from the course before the census date. It was only when she quizzed Rubbal further that Ms Kidwell discovered the true nature of what was being offered. I conclude that the process at Taree was, in essence, the same as at Tolland. Unique’s employees’ only interest was to get the paperwork completed without any interest in either explaining the true nature of what was on offer or the debt to which it would give rise. Whilst Ms Kidman [we think this is a reference to Ms Kidwell] was not ultimately exploited because she worked out what was going on, her evidence does allow me to conclude that what took place at Taree was, in general, exploitative of the large number of indigenous people there.

71 If the only interest of Unique’s employees was to get the paperwork at Taree completed without any interest in explaining the offer or the debt, and it would appear without any interest in assessing the suitability of the courses for the consumers, one can conclude that at Taree, for financial motives and uncaring of the interests of the consumers, Unique, through its employees, did (and so had set out to) exploit a number of Indigenous people in Taree.

The primary judge’s factual findings on the system case

72 On the system case, the primary judge described (at [710]) the “most controversial assertion” in the ACCC’s case as the assertion that “Unique targeted particular locations including rural and remote towns and areas with significant populations of low socio-economic status for its enrolment process”. At [711], the primary judge identified Professor Vinson’s evidence as the principal evidence relied on by the ACCC for this assertion. Also at [711], the primary judge stated that he proposed to consider this case only as to NSW. This latter position is the subject of ground 1 of the ACCC’s cross-appeal.

73 Noting the “targeting” case was a circumstantial one, the primary judge identified (between [713] and [718]) the factors he considered tended for and against the ACCC’s assertion. We do not set them out here as we return to them when we explain our conclusions on the grounds of appeal. His Honour concluded (at [719]) that the ACCC had established the allegation that Unique targeted outlying areas, people of socio-economic disadvantage and Aboriginal people.

74 As to the other factual allegations made in the pleadings by the ACCC, the primary judge characterised them (at [720]) as largely involving “an attempt to extrapolate from what happened at the meetings in Walgett, Taree, Tolland and Bourke to a more general procedure”, giving the examples of the allegations that the system included having Unique’s staff represent to the proposed students that its courses were free, and that Unique had failed to explain adequately the contents of the sign-up forms.

75 Critically for some of the key issues on the appeal, the primary judge then said (at [720]-[721]):

… At a high level of generality that kind of reasoning – if unsupported by anything else – would not permit one to conclude that the enrolment system had those features. To do that successfully, it would be necessary to conclude that the events at Walgett, Taree, Tolland and Bourke were somehow representative and to reach that conclusion it would be necessary to know how the Applicants had selected the nominated consumers in those towns from amongst the thousands of persons enrolled with Unique across the relevant period.

I raised this with the Applicants before the trial commenced and Unique made the same point in its submissions. I do not think that any satisfactory answer by the Applicants was ever made to this point. Certainly, the Applicants made no attempt of which I was aware to explain how they had chosen the individual consumers and towns that they had. Without that information, I cannot rationally conclude that what took place in those towns was generally representative.

(emphasis added)

76 Despite the conclusion at [721], in the same paragraph the primary judge then went on to find that he can identify “certain more limited systemic features” from Unique’s own evidence:

(a) The gift of computers to proposed students on signing up (either directly as a gift before 31 March 2015 or on a purported loan basis after that date);

(b) The use of incentives for Unique’s own staff to encourage them to sign up students; and

(c) The holding of sign-up meetings at the targeted locations.

There was no real debate that these findings were open on the evidence.

The primary judge’s conclusions on the other alleged contraventions

77 As we noted at the outset of these reasons, the ACCC relied on three causes of action.

78 At [724]-[726], dealing with ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL (the latter of which relates to representations about the price of the goods or services), the primary judge made a number of findings about what Unique’s employees or agents were required to explain to consumers in light of the nature of the “cohort” involved and the offer of free laptops. These findings are not the subject of any appeal and need only be noted. They do feature in the ACCC’s cross-appeal. As we note below, the primary judge then went on to make findings about contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to the individual consumers.

79 From [730] to [756] the primary judge explained the reasons for his conclusion that the ACCC had established a contravention of both s 79(b)(i) (failure conspicuously to include a notice informing the consumer of their right to terminate an agreement) and s 79(c)(i) (failure to include a form of notice for so doing). The primary judge further concluded that Unique’s contention that its conduct fell within the “party plan” exception in s 69(4) of the ACL, read with reg 81(1)(c) of the Competition and Consumer Regulations 2010 (Cth), should not be accepted. In relation to the individual consumers, the primary judge found that there were some further contraventions of the unsolicited agreements provisions in ss 76 and 78 of the ACL and, in relation to some individuals, s 74.

80 Along the way to these conclusions, the primary judge found that the decision in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ACN 099 814 749 Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 403; 344 ALR 61 was plainly wrong. That disagreement concerned whether it was necessary, for the application of s 69 of the ACL, for the dealer to initiate negotiations. The primary judge concluded that it was not; Reeves J in that case had concluded that it was. Neither the primary judge’s findings about this decision, nor his findings about contraventions of ss 74, 76, 78 or 79 of the ACL, are the subject of any appeal and also need only be noted. We do not set out below the details of the further findings made by the primary judge about the unsolicited agreements provisions of the ACL.

The primary judge’s conclusions on s 21

81 At [757], the primary judge noted there had been little judicial consideration of the phrase in s 21(4) “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour”, and noted that there were at least two limbs. First, where an “internal process is deliberately adopted”, and second where a “process emerges without necessarily ever having been expressly articulated”. His Honour stated that both limbs had relevance to the matter before him.

82 On the individual consumer case, the primary judge:

(a) At [758]-[761], did not accept there were contraventions of s 21 in relation to Ms Paudel at Walgett. His Honour also appears to find (at [760]) no contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to Ms Paudel.

(b) At [762]-[765], accepted there were contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to Mr Tre Simpson at Tolland, and also contraventions of s 21.

(c) At [766]-[768], did not accept there were contraventions of ss 18 or 29 in relation to Ms Kylie Simpson at Tolland, but did find there was a contravention of s 21.

(d) At [769]-[770], accepted there were contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to Ms Jaycee Edwards at Bourke, and also a contravention of s 21.

(e) At [771], accepted there were contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to Ms Fiona Smith at Bourke, and also a contravention of s 21.

(f) At [772], accepted there were contraventions of ss 18 and 29 in relation to Ms June Smith at Bourke, and also a contravention of s 21.

83 From [773] to [778] the primary judge set out his conclusions on the system case. Comparatively, it is a brief section of his Honour’s reasons. A great deal of focus in argument on the appeal fell on these paragraphs.

84 It is necessary, however, to remind oneself that the primary judge concluded at [720] and [721] that he could not rationally extrapolate anything as to the system case from the findings as to the four locations. That was not the subject of complaint by the ACCC on appeal; nevertheless a thread of the argument that these events were somehow representative of a broader system or pattern remained. At [774], the primary judge drew together from the factual findings (and [719] and [721] in particular) the four features of the ACCC’s factual case that he had accepted could constitute a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour:

(a) the strategy of targeting disadvantaged people by reference to indigeneity, remoteness and social disadvantage (whether deliberate in its original conception or not);

(b) the use of gifts of laptops or iPads to students signing (or loan computers after 31 March 2015);

(c) the use of incentives to staff to encourage them to sign up students; and

(d) the holding of sign-up meetings.

85 At [775], the primary judge explained why he declined to deal with the s 21 case in relation to allegations about conduct in Queensland and Victoria, finding a case about those States “was not clearly run”. This is the subject of one of the ACCC’s grounds of cross-appeal.

86 At [776], the primary judge explained why each of those features constituted a system or pattern of behaviour. As to the features (b)-(d), his Honour expresses a brief conclusion. As to feature (a), his Honour expands his reasons a little more:

Matters (b) to (d) constituted a system within the meaning of s 21(4). They were each the result of considered decision making by senior management within Unique. This is not clear, however, in the case of (a). As I have indicated above, whilst I accept that targeting of the disadvantaged is what took place I remain unclear as to how it came about. But I am certain that it was happening. In that circumstance, it is appropriate to describe what took place as a pattern of behaviour within the meaning of s 21(4). However, I do not need to decide precisely what the mechanism was. For the purposes of considering the Applicants’ case it is sufficient that I am satisfied that there must have been such a mechanism. I am satisfied of that proposition in New South Wales.

87 At [777], the primary judge reiterates that he sees the four features, together, as a “system”:

The Applicants therefore succeed in establishing within the meaning of s 21(4), the existence of both a system and a pattern of behaviour with the four features above. I will call the system and pattern thus identified compendiously, ‘the system’.

88 Having made his finding about the existence of a system or pattern of behaviour, the primary judge turned to the characterisation issue, and concluded that the system was unconscionable (at [778]):

The next question is whether this system was unconscionable. I do not think that (b) to (d) by themselves would necessarily be unconscionable. With the correct student cohort and management practices this style of operation may well have been permissible. However, when the practices in (b) to (d) are deployed against a targeted group of disadvantaged persons very different issues arise. In terms of s 22(1), it seems to me relevant to note in an assessment of the system that the targeted cohort consisted of people who were unlikely to understand the documentation involved (s 22(1)(c)) and that the use of the gift of a free (or ‘lent’) computer was apt to confuse this particular cohort into thinking a very bad deal was a good one – in my opinion an unfair tactic within the meaning of s 22(1)(d). The effect of the system in (b) to (d) was to supercharge the exploitation of the disadvantaged group which was being targeted (and also Unique’s remarkable profits). The system was unconscionable within the meaning of s 21.

89 The reasons conclude with an explanation of arrangements for determination of appropriate relief.

Relief granted

90 Having invited submissions and after hearing the parties, the primary judge granted declaratory relief, over the objection of the ACCC: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Unique International College (No 7) [2017] FCA 1289. The first declaration related to Unique’s conduct constituting a system or pattern of behaviour. The next six sets of declarations related to contraventions of the ACL by Unique in relation to the six named individuals.

91 Since this is the only order impugned on the appeal, the form of the declaration made in relation to the system case should be set out:

During the period from 1 July 2014 to 30 September 2015 (relevant period), Unique engaged in a system of conduct and a pattern of behaviour in connection with the supply or possible supply, or marketing of the supply, of online vocational education courses (courses) to consumers in New South Wales that was unconscionable within the meaning of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), by:

1.1. targeting disadvantaged people by reference to indigeneity, remoteness and social disadvantage;

1.2. offering gifts of laptops and iPads (or loan computers after 31 March 2015) to consumers to sign up;

1.3. providing financial incentives to its sales representatives to encourage them to sign up consumers; and

1.4. holding sign-up meetings.

The grounds of appeal and the cross-appeal

Unique’s grounds of appeal

92 There are eight grounds of appeal, all concerned with the primary judge’s findings and conclusions on the system case. Ground 8 is something of a rolled-up ground, as we understand, designed to invite the Full Court to reach its own conclusion on the evidence on the system case if it finds error in the primary judge’s reasoning, rather than to remit any aspect of the system case. We are satisfied that is the appropriate approach to take. That is because we are persuaded the evidence is insufficient to prove the system case on the balance of probabilities, both as to the conduct said to constitute the system or pattern of behaviour, and as to the characterisation of that conduct as unconscionable.

93 There was, however, a range of other relief sought by the ACCC in relation to other contraventions the primary judge found had been established, and for which no relief has yet been granted. The matter will need to be remitted to the primary judge in order to deal with the balance of the relief.

94 Aside from ground 8, Unique’s submissions divided the grounds of appeal into three groups. First, there was a contention that the primary judge erred in his findings about the system case, because there was no evidence led as to the appellant’s conduct towards the vast majority of its students (Ground 1). This ground occupied the most time in oral argument on the appeal and it is the principal basis on which we allow the appeal. Secondly, grounds which challenged the primary judge’s first factual finding on the system case: namely that Unique had a strategy of targeting disadvantaged people by reference to “indigeneity” (the term used in evidence at first instance), remoteness and social disadvantage (Grounds 2 to 5). As we understand Unique’s arguments, these grounds went mostly (if not entirely) to the primary judge’s fact-finding, rather than his characterisation of the conduct as unconscionable, although we consider Unique recognised, correctly, that the unconscionability finding as made by the primary judge would inevitably fall away if these grounds succeeded. The reality of this is apparent from the terms of [778] of the reasons (as to which see [88] above). Thirdly, two grounds which challenged the characterisation of what was, as we understand the case, uncontentious evidence about the provision by Unique of iPads and laptops, as unconscionable conduct (Grounds 6 and 7).

What is not challenged on the appeal

95 We emphasise there are no grounds of appeal relating to:

(a) the primary judge’s declarations, or findings, in relation to the individual consumer cases under s 21;

(b) the primary judge’s findings on contraventions of ss 18 and 29 of the ACL; and

(c) the primary judge’s findings on contraventions of ss 74, 76, 78 and 79 of the ACL.

The ACCC’s cross-appeal

96 The ACCC raised two grounds on its cross-appeal, both going to the primary judge’s findings concerning contraventions of s 21 of the ACL. Both would have the effect of widening the relief the ACCC submits should be granted in relation to the contraventions, by widening the basis for the contraventions.

97 Ground 1 of the cross-appeal contends the primary judge should have found, on the ACCC’s system case, that Unique’s unconscionable conduct occurred in Victoria and Queensland, as well as New South Wales.

98 Ground 2 of the cross-appeal contends that the primary judge should have found there were five additional features to Unique’s unconscionable system or pattern of behaviour, making nine features in total. The ACCC contends those additional five features were that Unique’s representatives:

(a) made false, misleading or deceptive representations to consumers;

(b) failed to explain the VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme to consumers;

(c) failed to explain the nature and content of the forms they had consumers sign;

(d) failed to ensure that consumers were enrolled in courses that were suitable for them; and/or

(e) failed to comply with the requirements for making unsolicited consumer agreements in Division 2 of Part 3-2 of the ACL.

99 During oral argument, it became apparent that the ACCC also contended that if any or all of the four features the primary judge found constituted the system or pattern of behaviour could not be upheld on the appeal, then these five features (or a combination of two or more of them, or a combination of one or more of these five features with one or more of the four features found by the primary judge) could nevertheless still constitute a system or pattern of behaviour and so the Court’s declaration of a contravention of s 21 by Unique should stand.

100 We consider both grounds of the cross-appeal should be dismissed, and we explain our reasons for this at [232]-[249] below.

Resolution: Unique’s appeal

101 In summary, we uphold the appeal on ground 1, which means the first declaration concerning contraventions of s 21 by reason of the system case must be set aside. We uphold ground 8, on the basis that, having considered the evidence for ourselves, but primarily taking into account our reasoning on ground 1, there is no basis in the evidence for any findings of contravention against Unique on the ACCC’s s 21 system case as pleaded and as conducted.

102 Those conclusions are sufficient to dispose of the appeal. Nevertheless, we have considered the other six grounds of appeal, and would uphold most of them. It is necessary only to deal with those grounds briefly, given our conclusions on grounds 1 and 8.

The current state of authority concerning contraventions of s 21 by reason of a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour

103 In Kobelt v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2018] FCAFC 18 at [176]–[178] the Full Court explained the introduction of s 21(4) and its equivalent provision in s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), in terms we respectfully adopt:

Section 12CB of the ASIC Act was amended by the Competition and Consumer Legislation Amendment Act 2011 (No 184 of 2011) to add (among other amendments) s 12CB(4)(b) which is in the following terms:

(4) It is the intention of the Parliament that:

(a) …

(b) this section is capable of applying to a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour;

…

This amendment commenced in operation on 1 January 2012. The Explanatory Memorandum for the Bill, when dealing with an identical amendment to the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Australian Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), stated that the unconscionable conduct provisions of the Australian Consumer Law are not limited to individual transactions. After referring to the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Exchange Pty Ltd (2005) 148 FCR 132 (National Exchange) (a case we will consider shortly), the Explanatory Memorandum stated:

2.23 … However, it follows from the principle that a specific person need not be identified that a special disadvantage is not a necessary component of the prohibition.

2.24 To emphasise this point, paragraph 21(4)(b) of the ACL indicates Parliament’s intention that the provision may apply whether or not there is an identified person disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour. This ensures that the focus is on the conduct in question, as opposed to the characteristics of a particular person, or the effect of the impugned conduct on that person.

In his Second Reading Speech, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasurer said:

The final interpretative principle to be introduced by the bill is that the prohibition on unconscionable conduct applies to systemic conduct or patterns of behaviour and that there is no need to identify a person at a disadvantage in order to attract the prohibition.

Unconscionable conduct is not limited to individual transactions or events …

This interpretative principle ensures that conduct, rather than individual transactions or events, is the focus of the provisions.

104 The extension of s 21 by para (4)(b) to a “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour” which is unconscionable removes the necessity for revealed disadvantage to any particular individual. A “system” connotes an internal method of working, a “pattern” connotes the external observation of events. These words should not be glossed. How a system or a pattern is to be proved in any given case will depend on the circumstances. It can, however, be said that if one wishes to move from the particular event to some general proposition of a system it may be necessary for some conclusions to be drawn about the representative nature or character of the particular event. The notion of unconscionability is a fact-specific and context-driven application of relevant values by reference to the concept of conscience: see Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2015] FCAFC 50; 236 FCR 199 and Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Kojic [2016] FCAFC 186; 249 FCR 421. It is an assessment of human conduct. A system of conduct requires, to a degree, an abstraction of a generalisation as to method or structure of working or of approaching something. If s 21(4)(b) is to be engaged, it is the system that is to be unconscionable. Nevertheless, the concept of unconscionability (even of a system) is a characterisation related to human conduct by reference to conscience, informed by values taken from the statute. As Cardozo J said (speaking for the Court) in Lowden v Northwestern National Bank & Trust Co 298 US 160 at 166 (1936) (albeit in a very different context): “A decision balancing the equities must await the exposure of a concrete situation with all its qualifying incidents. What we disclaim at the moment is a willingness to put the law into a straitjacket by subjecting it to a pronouncement of needless generality.” This expression of legal technique in the firmly gentle style of that great judge only reflects what other great judges of the tradition of Equity have said, such as in the passage of the judgment of Dixon CJ, McTiernan J and Kitto J in Jenyns v Public Curator (Qld) [1953] HCA 2; 90 CLR 113 at 119 adopting what Lord Stowell had said in The Juliana (1822) 2 Dods 504 at 522; 165 ER 1560 at 1567: “A court of equity….looks to every connected circumstance that ought to influence its determination upon the real justice of the case.” These expressions of legal technique should be recalled when the temptation arises to seek to re-define in short terms the words chosen by Parliament that require the application of general values to factual and contextual circumstance by reference to the notion of conscience.

105 Although there has been comparatively little consideration of the function and operation of s 21(4) in a principled way, a number of previous “system” case decisions bear examination, in terms of how the regulator sought to prove a system case, and how the Court dealt with the evidence adduced.

106 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Excite Mobile Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 350; ATPR 42-437 was a proceeding brought under s 51AB of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), concerning the marketing, sale and supply of mobile telephone services through a telemarketing company based in India and other call centres in Asia. Potential customers were contacted by telemarketers and offered, through the use of scripts, an enticement to contract, namely the “gift” of a phone and holiday vouchers. Excite itself did not appear to contest the allegations, but the named individual respondents did appear and contested the case against them. Mansfield J did not consider what constitutes a system or pattern of behaviour in his reasons for judgment, but the level of evidence provided by the ACCC provides some occasion for comparison with the present appeal.

107 In terms of the nature of the evidence, on the uncontested case, Mansfield J described it in the following terms at [16]:

The ACCC provided 10 examples of telemarketing calls and / or mobile contracts that were selected as follows. The first and last customers of Excite Mobile were chosen. The remaining eight customers were selected by choosing the last customer of every second month in which there was a recording available.

108 His Honour also noted at [131]:

… There was no submission that the documentary or electronic evidence was inaccurate or selective. In particular, the sampling of various telemarketer calls as random, and therefore representative, in general terms, was also not challenged.

109 Another aspect of the unconscionable conduct in this case was Excite’s debt recovery process. In terms of the evidence relied upon, Mansfield J stated (at [48] and [49]) the ACCC submitted evidence of 136 recordings with 98 different customers involving one of Excite’s employees, and three recordings involving another employee, and the evidence about which consumers succumbed to the debt recovery pressure related to the agreements of approximately 90 customers.

110 There is no magic in these numbers: however, on any view, they demonstrate two matters. First, the selection of evidence of individual consumers through a random or representative process, with the process disclosed on the evidence. Second, the use of evidence about a reasonable number of individual consumers so that, even if intuitively, a Court could exclude hypotheses of coincidence or lack of representativeness, and could, because of the number of individual consumers about which evidence was led, safely perceive a “pattern”. What happened with 80 consumers, even on a hypothetical sample of thousands (the estimated total number of consumers in Excite is not set out in the evidence), may well be sufficient evidence for a Court to decide whether or not there is a pattern.

111 In contrast, can conduct in relation to six consumers establish a “pattern of behaviour” or a “system”? As we explain below, in a known class of more than 3,600 consumers, and on the limited evidence before the primary judge, we would find they could not, at least not without persuasive evidence about how the six could be said to be representative of the 3,600.

112 The allegations in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Keshow [2005] FCA 558; ASAL 55-142 have some factual parallels with the current proceeding. Keshow was also a Trade Practices Act case, concerning a person Mansfield J described as a “humbugger”, who travelled through Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory, purporting to sell and supply children’s educational materials and, at a later time, household goods as well. At [3], Mansfield J described the conduct in the following terms:

… He took advantage of the lack of education and commercial experience of those in the communities in doing so. In many instances, the educational materials were not needed or useful having regard to the age of the child or children of the consumer. The products he contracted to provide were most commonly not supplied, or not supplied in their entirety. Whether a contract to provide educational materials was met was haphazard. The payment arrangements in each instance involved an open-ended periodic payment authority, procured at the instance of the respondent, and authorising payment on the day which Centrelink or like benefits were regularly received by the particular complainant or other community resident. The respondent in a number of instances continued to receive periodic payments well after the value of the goods to be provided by him (whether or not they had been provided) had been received. In fact, there is no evidence to show that the respondent maintained adequate records of what products had been sold to which consumers, whether the products had been provided, as agreed, or what had been paid for them.

113 There were eight individual complainants from three Aboriginal communities, together with evidence from three people with some level of responsibility with one of the communities (Amoonguna). The evidence was that the respondent also visited other communities in the Northern Territory, including Hermannsburg, Meekatharra and communities at Katherine and Tennant Creek. However, it would appear the total number of consumers was not nearly as large as in the current appeal.