FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Coretell Pty Ltd v Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 54

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed in part.

2. The Declaration and the Directions 7 and 8 made by the primary judge on 23 March 2016 be set aside and in lieu thereof there be the following Declaration and Directions:

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondents and each of them have from 16 December 2010 until 5 September 2013 infringed each of claims 1 to 5 of Australian Innovation Patent No 2010101356 (‘356 Patent) and from 15 September 2011 until 5 September 2013 infringed each of claims 1 to 5 of Australian Innovation Patent No 2011101041 (‘041 Patent) (together, the Patents).

THE COURT DIRECTS THAT:

2. There be an inquiry as to profits or damages and additional damages (if any) in respect of the respondents’ infringement of the Patents.

3. The respondents provide discovery (in the event that they have not already done so), to be verified by an affidavit of the third respondent by 21 April 2017, in accordance with r 20.15 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), of the documents in the following categories:

(i) all invoices issued by Procept Pty Ltd to any of the respondents recording the supply of ORIshot orientation tools and/or any circuit boards for ORIshot orientation tools between 16 December 2010 and 5 September 2013; and

(ii) all invoices issued by Coretell Pty Ltd to its customers or agents recording the supply of ORIshot orientation tools between 16 December 2010 and 5 September 2013.

3. The appellants pay ninety per cent of the respondents’ costs of the appeal.

4. Order 3 hereof be suspended for a period of 28 days.

5. Any party wishing to apply for a costs order different to order 3 hereof may file and serve a written submission (limited to 3 pages in length) within 7 days.

6. Any party wishing to reply to such written submission is to file and serve a written submission in reply (limited to 2 pages in length) within 14 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

1 I agree with the reasons of Justice Burley and the orders which he proposes.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Jagot. |

Associate:

Dated: 3 April 2017

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NICHOLAS J:

2 I agree with the reasons of Justice Burley and the orders which he proposes.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Nicholas. |

Associate:

Dated: 3 April 2017

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[3] | |

[9] | |

[11] | |

[17] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[29] | |

[29] | |

[34] | |

[54] | |

[58] | |

[66] | |

[68] | |

[98] | |

[100] | |

[108] | |

[108] | |

[110] | |

[117] | |

[118] | |

[119] | |

[119] | |

[122] | |

4 INVALIDITY – EXTERNAL FAIR BASIS AND PRIORITY DATE – GROUNDS 15 AND 16 | [127] |

[127] | |

[132] | |

[137] | |

[155] | |

[156] | |

[161] | |

[163] | |

5 PRIOR USE – GROUNDS 19 AND 20 AND PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE NOTICE OF CONTENTION | [172] |

[172] | |

[176] | |

[179] | |

[184] | |

[184] | |

5.4.2 Grace period – Ground 20 and paragraph 1 of the Notice of Contention | [201] |

6 PRIOR SECRET USE – GROUND 21 AND PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE NOTICE OF CONTENTION | [203] |

[203] | |

[205] | |

[208] | |

[213] | |

[228] | |

6.4.2 Consideration – paragraph 2 of the Notice of Contention | [244] |

[247] | |

[256] |

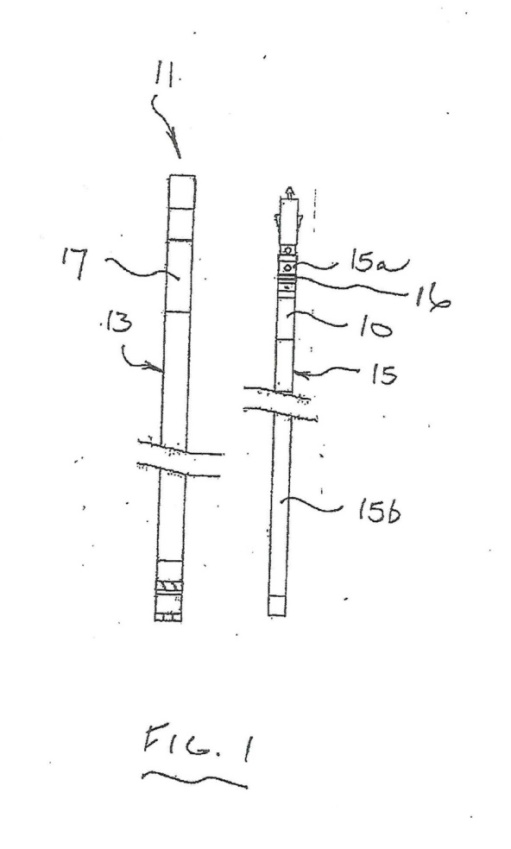

3 Core sample orientation is commonly used in connection with geological surveying operations and other drilling operations. It is a technique whereby core samples of material extracted from the ground are oriented upon their removal from the bedrock. In December 2010 and August 2011, the Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd (AMC) filed two innovation patents, each entitled “Core Sample Orientation”, relating to this field. The first, the System Patent, was filed on 2 December 2010 and is innovation patent no. 2010101356. The second, the Method Patent, was filed on 16 August 2011 and is innovation patent no. 2011101041. They are referred to below collectively as the Patents.

4 After the Patents had been certified, AMC and its exclusive licensee, Reflex Instruments Asia Pacific Pty Ltd (collectively, respondents) sued the current appellants for infringement. One of the appellants, Coretell Pty Ltd (Coretell) filed a cross-claim alleging invalidity.

5 The present proceeding is not the first litigation between these parties. In 2007 AMC sued Coretell for infringement of innovation Patent no. 2006100113 which was also entitled “Core Sample Orientation” (Device Patent). It had a priority date of 3 September 2004 and was certified on 20 July 2006. The infringement suit was unsuccessful at first instance; Australian Mud Co Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1169; (2010) 88 IPR 270 and on appeal; Australian Mud Co Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 121; (2011) 93 IPR 188. Undeterred, AMC filed the innovation patents in suit and sued again.

6 This time they were more successful. In a detailed judgment (Australian Mud Co Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 1372), the primary judge found that the respondents had infringed the claims of each of the Patents and dismissed the cross-claim for invalidity. In a separate judgment (Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd (No 5) [2016] FCA 444), the primary judge ordered that the present appellants pay indemnity costs in respect of parts of the cross-claim.

7 The appellants do not contest the primary judge’s findings of infringement, but in substance challenge his Honour’s conclusions in respect of five of the 12 rejected grounds of invalidity. The appeal initially raised 26 grounds and was listed for hearing over five days. With admirable restraint, shortly before the hearing the appellants trimmed the grounds of appeal to 11, and the appeal was heard over two days.

8 The Act and Regulations have been amended a number of times. The parties agreed that the applicable versions of the Act and Regulations referred to in this judgment are those in force immediately prior to the passing of the “Raising the Bar” legislation. In these reasons, I have relied on the compilation of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) prepared on 30 January 2012 (Act), and Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth) prepared on 1 October 2012 (Regulations).

9 The appellants are Coretell, Mincrest Holdings Pty Ltd (Mincrest), Mr Nicky Kleyn and Kleyn Investments Pty Ltd (Kleyn Investments). Mr Kleyn is the sole shareholder, director and company secretary of Coretell and also Kleyn Investments. He is one of two shareholders in, and directors of, Mincrest (the other being his wife). Although Coretell was the cross-claimant in the proceedings below, each of the appellants appeals against the primary judge’s orders and findings concerning invalidity.

10 The respondents are wholly owned subsidiaries of Imdex Limited (Imdex). A business division of Imdex is known as Ace Drilling.

11 A number of matters significant to the grounds of appeal arise from dates relevant to each of the Patents.

12 The System Patent was filed on 2 December 2010. The Method Patent was filed on 16 August 2011. Both were filed as divisional applications made in relation to standard patent application no. 2010200162 (162 Application) pursuant to s 79B(1) of the Act. The filing date of the 162 Application is 15 January 2010. The 162 Application is in turn a divisional application filed in relation to standard patent application no. 2005256104 (104 Application) filed on 5 September 2005.

13 It is not in dispute that by application of s 43 of the Act and reg 3.12 of the Regulations, the earliest potential priority date of the Patents is 3 September 2004 (priority date). This is the filing date of provisional patent application no. 2004905021 (Provisional Application).

14 It is also not in dispute that by operation of s 65 of the Act and reg 6.3 of the Regulations, the “date” of the Patents is 5 September 2005, being the date of the filing of the complete application of the 104 Application. By operation of s 68 of the Act, this is the date from which the term of the Patents (which, being innovation patents, is 8 years) is calculated.

15 The System Patent was granted pursuant to s 62 of the Act on 16 December 2010 and certified pursuant to s 101E of the Act on 5 September 2011.

16 The Method Patent was granted pursuant to s 62 on 15 September 2011 and certified pursuant to s 101E on 1 November 2011.

1.3 Summary of grounds and conclusions

17 The appellants rely on a Substituted Further Amended Notice of Appeal filed on 14 November 2016 (Notice of Appeal). That document reduces the grounds of appeal relied upon, but retains the original numbering from the previous draft. In order to aid cross-referencing, I have below retained the numbering in that document.

18 Grounds 1, 2 and 3 concern the identification of the correct date in respect of which the respondents may obtain relief for infringement of the Patents. The contest shows a significant divergence of views. As I explain below, the primary judge implicitly followed the reasoning of Middleton J in Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 1019 (Britax) which concluded that by operation of ss 13, 65 and 68 of the Act and reg 6.3 of the Regulations, the correct date was the date of the Patents, in this case being 5 September 2005. As a consequence, the primary judge found that the appellants may be liable for acts of infringement committed after that date. The appellants contend that the reasoning in Britax is incorrect and that the correct date should be the date of the grant of the Patents being between five and six years later, on 16 December 2010 (System Patent) and 15 September 2011 (Method Patent). In section 2 below, I accept the appellants’ submission, with the result that grounds 1 and 2 and parts of ground 3 of the appeal are allowed.

19 In ground 6 the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in his findings concerning the accessorial liability of Kleyn Investments. In section 3 I find that the appeal in relation to Kleyn Investments is partially allowed.

20 Grounds 15 and 16 challenge the primary judge’s findings as to the identification of the correct priority date for the Patents, which, if allowed, would have the consequence that the claims of the Patents are invalid for lack of novelty. These grounds call for consideration of whether or not the patentee is entitled to claim priority based on the disclosure of the Provisional Application. In section 4 below I find that the primary judge correctly applied the test for external fair basis and correctly determined that the Patents were entitled to the priority date.

21 Ground 19 of the appeal concerns an alleged novelty-defeating prior use of the invention in that Chardec Consultants Limited (Chardec) (the employer of the inventor of the Patents, Mr Parfitt) used and authorised the public use of the invention by disclosing it to third parties before the priority date. Ground 20 contends that if the learned primary judge found that the “grace period” provisions applied to such use, then he fell into error. In section 5, I reject ground 19 of the appeal and uphold his Honour’s findings. The respondents have filed a Notice of Contention to the effect that his Honour ought also to have also found that any public prior use of the invention benefitted from the grace period provisions under s 24 of the Act. I do not consider, in the circumstances, that it is necessary to address the Notice of Contention.

22 In ground 21 the appellants contend that the primary judge ought to have found that the claims of the Patents are invalid as a result of the prior secret use of the invention, pursuant to s 18(1A)(d) of the Act. In section 6 below I consider this ground and find that by reason of the operation of s 9(a) of the Act, there has been no invalidating prior secret use.

23 In section 7 I consider and reject the appeal against the primary judge’s costs’ orders.

24 In section 8 I address the disposition of the appeal and orders to be made.

2. ALLEGED INFRINGEMENT PRIOR TO GRANT – GROUNDS 1, 2 AND 3

25 Grounds 1, 2 and 3 concern the identification of the earliest date from which relief for infringement of an innovation patent granted upon a divisional application filed pursuant to s 79B of the Act may be awarded. The appellant contends that the primary judge erred by determining that the relevant date from which a cause of action accrues, and in respect of which an act of infringement arises, is the date of grant of the patent. In the present case, the Patents were granted as innovation patents on 16 December 2010 for the System Patent, and 15 September 2011 for the Method patent.

26 The respondents contend that the primary judge did not make a determination of the date upon which the cause of action accrued. This is because the issues of quantum and liability were separated, and the primary judge has not yet considered quantum. However, if the question arises on appeal, the respondents argue that the correct date upon which the cause of action for infringement accrues is from the commencement of the term of the Patents. In the present case, by applying the formula prescribed under the Act, the appellants submit that the eight year term of these patents commenced on 5 September 2005, and it is from then that the respondents are entitled to remedies in respect of acts of infringement.

27 Although I accept that the primary judge did not need to determine the question, and for that reason (understandably) did not give reasons on the subject, it appears to me that he did implicitly find that the relevant date for assessing infringement was 5 September 2005. This arises at least from his conclusion at [420] where, in rejecting the defence of innocent infringement his Honour said (emphasis added):

… This defence has no prospect of success. The respondents were informed promptly of the existence of the Patents at the time that those Patents were granted and, in respect of the period prior to grant, they were aware of the existence of the earlier patent applications on which the applicants’ claim for the relief depends.

28 A similar finding is apparent from his Honour’s general acceptance that the applicants had made out their case for infringement (at [263]), in circumstances where that case was put by the respondents as arising from conduct commencing on 5 September 2005. On appeal the argument was raised and fully argued. In my view it is appropriate to consider and determine the question.

29 In the present case the Patents began their lives as divisional patent applications filed in respect of their parent, the 162 Application, which was an application for a standard patent. The 162 Application was in turn a divisional application filed in relation to the 104 Application, which is the grandparent.

30 Section 79B of the Act provides for divisional applications (emphasis added; italics in original):

79B Divisional applications prior to grant of patent

(1) If a complete patent application for a patent is made (but has not lapsed or been refused or withdrawn), the applicant may, in accordance with the regulations, make a further complete application for a patent for an invention:

(a) disclosed in the specification filed in respect of the first-mentioned application; and

(b) where the first-mentioned application is for a standard patent and at least 3 months have elapsed since the publication of a notice of acceptance of the relevant patent request and specification in the Official Journal—falling within the scope of the claims of the accepted specification.

(1A) The reference to a complete patent application first-mentioned in subsection (1) does not include a reference to a divisional application for an innovation patent provided for in section 79C.

…

31 The “further complete application” within s 79B(1) is commonly referred to as a “divisional application”. It is an application which claims an invention that has been disclosed in an earlier filed patent or patent application (in s 79B(1) the “first-mentioned application”) which is commonly referred to as a “parent”. The parent of a divisional application may itself be a divisional application (s 79B(1)(b)) and is sometimes referred to as the “grandparent”.

32 A divisional application may either be for an innovation patent or a standard patent. With presently immaterial differences, the scheme of the Act concerning the commencement of the term of a patent and its priority date is the same for both.

33 There are several benefits to a patentee in filing divisional applications. One is that where the claims of the divisional are fairly based on matters disclosed in the parent (or, where relevant, the grandparent) the priority date of a divisional mirrors that of its ancestor; reg 3.12(1)(c) and (2C); Bodkin C, Patent Law in Australia (2nd ed, Thomson Reuters, 2014) (Bodkin) at [11120]. Another concerns the procedure for filing patents. As the author of Bodkin explains, the most obvious reason for filing a divisional application is to accommodate the requirement that the claims of a patent relate to a single invention only pursuant to s 40(4) of the Act. If a standard or innovation patent application filed is found upon examination to claim more than one invention, the applicant or patentee must delete or remove claims. The provisions in relation to divisional applications then permit the applicant or patentee to apply for a patent in respect of the invention disclosed, but no longer claimed; Bodkin at [11120]. Another benefit arises where patent applicants have not gained acceptance of their patent application within the available time from the date of the first examination report (normally within 12 or 21 months of the first examination report, depending on when examination was requested; reg 13.4). By filing a divisional application near the due date for acceptance of the parent, a further time extension is effectively granted; Bodkin [11130].

2.2.2 The “term” and “grant” of patents

34 Under the Act, a “patent” is defined (in the Dictionary, Schedule 1 of the Act) to mean a standard patent or an innovation patent. An innovation patent means letters patent for an invention granted under s 62, and a standard patent means letters patent for an invention granted under s 61. Accordingly, under the Act a patent is identified by reference to its date of grant.

35 Section 13(1) of the Act provides that “[s]ubject to this Act”, a patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to exploit the invention. The “term” of a patent commences from the “date of the patent” (ss 67, 68). The “date of the patent” is the date of the filing of the relevant complete specification, or as determined under the regulations; s 65. The Dictionary defines “exploit”, in relation to an invention to include: (a) where the invention is a product – make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product or offer to do these things, or use, import or keep the product for the purpose of doing and of those things; or (b) where the invention is a method or process – use the method or process or do any act mentioned in (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

36 The date of the patent and the date of grant of the patent may differ. The present dispute concerns that difference. The exclusive right to exploit the patent commences with the term (i.e. date of patent). The pertinent question, then, is whether this means that the right to relief commences on that day also?

37 In relation to standard patents, s 61 relevantly provides that the Commissioner of Patents (Commissioner) must grant a standard patent by sealing it in the approved form if there is no opposition to the grant or if the opposition to grant fails. The route to grant is summarised below.

38 Under s 29(1), a person may apply for a patent by filing a patent request and such other documents as prescribed. An application may be a provisional application or a complete application. If the patent request is in relation to a provisional application, it must be in the approved form and accompanied by a provisional specification. If the patent request is in relation to a complete application, it must be in the approved form and accompanied by a complete specification.

39 Section 40 provides the substantive requirements for a complete specification (s 40(2)) and a provisional specification (s 40(1)). A complete specification must, inter alia, disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention and end with claims defining the invention. A provisional application must describe the invention (s 40(1)).

40 Section 49(1) provides, in relation to standard patents, that the Commissioner must accept a patent request and complete specification relating to an application for a patent if satisfied that the invention satisfies the substantive validity criteria set out in s 18(1)(b) and that there is no lawful ground of objection to the request and specification. Under s 49(5)(b), where the Commissioner accepts a patent request and a complete specification, the Commissioner must publish a notice of the acceptance in the Official Journal. Accordingly, acceptance of a standard patent application causes the application to become open to public inspection (unless it was already open).

41 Section 54(1) provides that, where a complete specification filed in respect of an application for a standard patent has not become open to public inspection, the Commissioner must, if asked to do so by the applicant, publish a notice that the complete specification is open to public inspection. Under s 54(3), where a complete specification has been filed in respect of an application for a standard patent, the prescribed period has ended and the specification is not open to public inspection, the Commissioner must publish a notice that the specification is open to public inspection.

42 Subsection 55(1) then provides that, where a notice is published under s 54, the specification concerned and other prescribed documents are open to public inspection. Subsection 55(2) provides that, where a notice is published under s 49(5)(b) in relation to an application for a standard patent (or under s 62(2) in relation to the grant of an innovation patent), the documents specified in s 55(2) that have not already become open to public inspection become open to public inspection. Under s 56, except as otherwise provided by the Act, documents of the kind mentioned in s 55 must not be published or be open to public inspection.

43 Section 57(1) adopts some significance in the context of the arguments on appeal. It applies to standard patents but not innovation patents. It provides that, after a complete specification relating to an application for a standard patent has become open to public inspection, and until a patent is granted on the application, the applicant has the same rights as he or she would have had if a patent for the invention had been granted on the day when the specification became open to public inspection.

44 However, s 57(3) provides that s 57(1) does not give the applicant a right to start proceedings in respect of the doing of an act unless:

(1) a patent is granted on the application; and

(2) the act would, if done after the grant of the patent, have constituted an infringement of a claim of the specification.

45 Section 57(4) provides that it is a defence to proceedings under s 57(1) in respect of an act done after the complete specification became open to public inspection, and before the patent request was accepted, if the defendant proves that a patent could not validly have been granted to the applicant in respect of the claims (as framed when the act was done) that are alleged to have been infringed by the doing of the act.

46 It follows from the language of s 57 that to make out an entitlement to relief for an act for infringement of a standard patent that took place before the date of the grant of a patent, that act must be shown to have infringed not only a claim of the patent as eventually granted, but also a published claim of the complete specification as it stood at the time when the relevant act occurred; see (in the context of s 129(b) of the Act) Bradken Resources Pty Ltd v Lynx Engineering Consultants Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1257; (2008) 78 IPR 586 at [31] (Emmett J).

47 Section 59 of the Act provides that the Minister or any other person may oppose the grant of a standard patent on specified grounds. Pre-grant opposition is often a lengthy process. As noted above, s 61 provides for the grant of the standard parent if there is no opposition or if any opposition is dismissed.

48 In relation to innovation patents, s 62 provides that the Commissioner must grant an innovation patent if he or she accepts a patent request and complete specification and no prohibition order is in force. As for a standard patent, the complete specification must, inter alia, disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention and end with no more than five claims defining the invention (s 40(2)(c)).

49 If so granted, s 62(2) provides that the Commissioner must make the patent request and complete specification open to public inspection. Section 62(3) provides that if a divisional application is made for an innovation patent pursuant to s 79B and a notice is published in the Official Journal that the complete specification filed in respect of the divisional application is open to public inspection, the Commissioner must also publish in the Official Journal a notice that the complete specification filed in respect of the original application on which the divisional application is based is open to public inspection.

50 Unlike a standard patent, an innovation patent is not subject to pre-grant opposition. An innovation patent will be accepted (and thence granted under s 62) after the Commissioner is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the application passes a formalities check; s 52.

51 Section 101A of the Act provides that after the grant of an innovation patent, the Commissioner may, if he or she decides to, and must, if asked by the patentee or another person to do so, examine the complete specification relating to an innovation patent. Section 101B provides a list of matters concerning the form and validity of an innovation patent that the Commissioner must consider in conducting such an examination. Section 101E provides that if the Commissioner is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the innovation patent complies with the matters listed, and that the patent has not ceased under s 143A, then the Commissioner must issue a certificate of examination to the patentee, and publish in the Official Journal a notice of the examination having occurred. Otherwise, if the Commissioner is not satisfied of the relevant matters listed, the Commissioner may revoke the innovation patent; s101F. The issue of a certificate of examination pursuant to s 101E is often referred to as “certification”.

52 Sections 67 and 68 address the term of standard and innovation patents respectively. Section 67 provides that the term of a standard patent is twenty years from the date of the patent. Section 68 provides that the term of an innovation patent is eight years from the date of the patent.

53 Section 65 provides that the “date” of a patent is either (a) the date of filing of the relevant complete specification; or (b) where the Regulations provide for the determination of a different date, the date determined under the Regulations. Regulation 6.3 provides the formula for calculating the date under the Regulations. Sub-regulation 6.3(7)(c) relevantly provides that the date of a patent granted on a divisional application made under s 79B(1) is the earliest of the date of the first-mentioned application referred to in s 79B(1) or, if the first-mentioned application was itself a divisional application, the date that would be the date if a patent had been granted on the divisional application.

54 Part 1 of Chapter 11 of the Act is entitled “Infringement and infringement proceedings”.

55 Section 120 relevantly provides:

120 Infringement proceedings

…

(1A) Infringement proceedings in respect of an innovation patent cannot be started unless the patent has been certified.

…

(4) Infringement proceedings must be started within:

(a) 3 years from the day on which the relevant patent is granted; or

(b) 6 years from the day on which the infringing act was done;

whichever period ends later.

56 The Act does not define an “infringement of a patent”. However, s 119(1) gives some assistance. It provides that a person may, without infringing a patent, do an act that exploits a product, method or process and would infringe the patent if, immediately before the priority date of the relevant claim, the person was either exploiting the product, method or process in the patent area, or had taken definite steps to do so. In this context, it is apparent that Parliament intends that a claimed invention will be infringed if it is “exploited” within s 13 unless the exception within s 119 applies; see Dufty A and Lahore J, Lahore Patents, Trade Marks & Related Rights (LexisNexis, subscription service) (Lahore) at [18,000]. An infringing act arises when the essential integers of claims are taken; see, for example, Meyers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd [1977] HCA 19; (1977) 137 CLR 228 (Meyers Taylor v Vicarr). Accordingly, leaving aside considerations arising under s 117 of the Act, an act of infringement requires an exploitation of the patent within the scope of at least one of the claims of the patent.

57 Section 122 relevantly provides:

122 Relief for infringement of patent

(1) The relief which a court may grant for infringement of a patent includes an injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the court thinks fit) and, at the option of the plaintiff, either damages or an account of profits.

…

2.3 The arguments and reasoning in Britax

58 In Britax, the issue was the identification of the earliest date of infringement of both a standard patent and several innovation patents. For the standard patent, the terms of s 57 applied, and so relief for infringement was available from the date on which the patent became open for public inspection.

59 For the innovation patents different circumstances applied. Each had been filed as a divisional application on standard patent applications under s 79B(1) of the Act and, by operation of reg 6.3(c) the “date of the patent” for each was 9 June 2005, being the date on which the parent patent was filed.

60 In Britax the respondents argued that the relevant date for infringement of the (divisional innovation) patents in suit is not the date of the parent patent application but the date of certification of each innovation patent. They relied on s 120(1A) which provides that infringement proceedings cannot be started unless the patent has been certified. The respondents also argued that s 57 of the Act provides that in the case of a standard patent, the patentee has the benefit of a provisional retrospective ability to sue in respect of acts of infringement prior to grant. No analogous provision applies for innovation patents. Accordingly, s 13 of the Act must be construed as being “subject to” and operating consistently with the express provisions of ss 57 and 120(1A) and it is these sections – not s 13 – that give the time from which liability for infringement arises for both standard and innovation patents.

61 Justice Middleton rejected these arguments. He reasoned that s 13(1) provides that an innovation patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights to exploit the invention during the term of such a patent and the term of an innovation patent is eight years from the “date of the patent” determined pursuant to s 65. Accordingly, the commencement of the date of the patent is the date from which infringement is to be calculated, being (in that case) 9 June 2005.

62 In rejecting the respondents’ arguments, Middleton J first considered that the requirement that innovation patents must be certified prior to commencement of infringement proceedings was not intended by the legislature to mark the date from which rights in respect of innovation patents accrue. Rather, the requirement that innovation patents be certified serves to ensure that certain policy aims of the innovation patent system are met. At [17] his Honour noted (by reference to the Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Patents Amendment (Innovation Patents) Bill 2000 (Cth) at [101], [102] and the Outline to that Revised Explanatory Memorandum), that these aims include the need to facilitate the quick and convenient grant of patents that are not subject to extensive pre-grant review, while ensuring that proceedings are only commenced (after certification) in relation to meritorious innovation patents that meet the criteria set out in Ch 9A of the Act.

63 Secondly, his Honour considered that the absence of an analogous provision to s 57 for innovation patents did not mean that patentees of innovation patents can only obtain relief for acts upon grant of the patent. He said (emphasis in original):

13 The absence of an analogous provision in the Act to s 57 for innovation patents simply reflects the reality of the operation of the innovation patent system. As noted in my reasons for judgment on construction at [25] to [26], the innovation patent system was introduced in 2001, when it replaced the previous petty patent system. It was intended that innovation patents would provide a relatively “inexpensive, quick and easy” way to protect inventions of a lower inventive standard than standard patents, or those with a short commercial life: see Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 29 June 2000, at 18,583 (per Warren Entsch). A major feature of this new system was the grant of such patents without first undergoing time-consuming and costly substantive examination.

14 Accordingly, in practice there may be little or no difference between the time of filing an application for an innovation patent, publication of a complete specification and the grant of such a patent. Indeed, under s 62(2) of the Act, publication of an innovation patent request and complete specification typically follows the grant of such a patent. These two events – publication of a complete specification and grant of an innovation patent – may therefore occur at or around the same time. Recourse to the Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Patents Amendment (Innovation Patents) Bill 2000 (Cth) (the Bill) indicates that for this reason, the legislature deliberately decided not to have an analogous provision to s 57 in the Act for innovation patents, as there is no practical need. Previously, a comparable provision to s 57(1) had existed in relation to petty patents (set out in now-repealed s 57(2)). The Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill relevantly provides:

Item 28 – Subsection 57(2)

45. This item repeals subsection 57(2) of the Patents Act consequential to the repeal of the petty patent system. The subsection deals with the publication of petty patents prior to grant. This provision will not apply to innovation patents because innovation patents will only be published after grant.

64 Thirdly, his Honour rejected the contention that the effect of his construction would give anomalous results in that divisional applications for both standard and innovation patents would have more extensive rights than their respective parent applications. The respondents’ submission in this context was that any patent filed as a divisional application upon a parent or grandparent patent application could have as its “date of the patent” a date that pre-dated the date upon which it became open for public inspection. Accordingly, in the case of these patents, the right to relief for infringement commenced earlier than permitted for non-divisional patents. In the case of standard divisional patents, this irrationally extended the rights for those patentees beyond those permitted under the conditional extension granted pursuant to s 57. In the case of divisional innovation patents, it produces a similar anomaly.

65 His Honour said at [21]:

21. … The Act and the Regulations together expressly provide for divisional patents (whether innovation or otherwise) to share the ‘date’ of their parent patent or parent patent application. I do not consider that this necessarily affords the divisional Innovation Patents in this proceeding “greater rights” than those of their parent patent application. Indeed, to some extent it may be said that the opposite is true for these divisional Innovation Patents: the fixed eight-year term of these patents started to run from an earlier date (namely, the date of the parent patent application) than might otherwise be the case for non-divisional innovation patents, and under the Act, there is no provision for obtaining an extension of the term of innovation patents. …

2.4 The arguments in present appeal

66 In the present appeal the appellants adopted overlapping arguments to those rejected in Britax although, unlike in Britax, the appellants contended that the correct date from which relief for an act of infringement may arise for an innovation patent is the date of grant, not the date of certification. They submitted that the primary judge erred in finding the appellants had infringed the claims of both Patents by conduct going back to 5 September 2005 (i.e. the date of patents) even though the Patents did not then exist and were not open for public inspection until December 2010 and September 2011. This, they submitted, produces a surprising and incorrect outcome.

67 In answer, the respondents adopted the reasoning in Britax.

68 I consider that the date from which the respondents are entitled to relief for infringement of the Patents is the date of their grant, for the following reasons.

69 First, the language of Part 1 of Chapter 11 of the Act supports this conclusion. Section 120(1) provides that the patentee or an exclusive licensee may start “infringement proceedings” in a prescribed court, or in another court having jurisdiction. As noted, an act of infringement will arise where an act is done in respect of the exclusive rights conferred pursuant to s 13. The term “infringement proceedings” is defined in the Dictionary to mean proceedings for infringement of “a patent”, which means a patent as granted pursuant to either ss 61 or 62. The term “patentee” is defined to mean the person for the time being entered in the Register as the grantee or proprietor of a patent.

70 Subsection 120(1A) of the Act provides that infringement proceedings in respect of an innovation patent cannot be started unless the patent has been certified. There is no equivalent provision in relation to a standard patent.

71 Accordingly, whilst a patentee of a standard patent may commence proceedings upon the grant of the patent, the patentee of an innovation patent must not only have received the grant of the patent but also certification under s 101E of the Act.

72 Section 122(1) provides that the relief which a court may grant for infringement of a patent includes an injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the Court thinks fit) and, at the option of the plaintiff, either damages or an account of profits. The words “for infringement of a patent” (emphasis added) signify that relief is available in respect of an act of infringement of a patent that conforms with the definition of that term. Namely, a standard or innovation patent that has had the benefit of a grant within ss 61 or 62.

73 Accordingly, the language of s 122(1) of the Act indicates that it is the grant of the standard patent that entitles the patentee to commence proceedings (s 120(1)), the grant and certification of the innovation patent that entitles the patentee of an innovation patent to commence proceedings for infringement (s 120(1A)) and the focus is upon “grant”. The relief which may be obtained is for the infringement of the granted patent (s 122(1)).

74 Secondly, the statutory expression in s 122(1) “relief… for infringement of a patent” must be properly understood. Infringement arises when all of the features of the invention as claimed are taken; Meyers Taylor v Vicarr. Infringement is in relation to the claims, which define the monopoly, not the patent at large. This lends support for the appellants’ contention that ss 13, 65, 68 and reg 6.3(7)(c) cannot be interpreted literally to give the patentee an enforceable monopoly in respect of an “invention”. The rights to relief can arise only when claims have been brought into existence.

75 In this context, s 40(2) of the Act requires that a complete specification end with claims defining the invention. A divisional application filed pursuant to s 79B(1) of the Act must also contain claims. That application may adopt as the “date of the patent” the date of the filing of complete specification of its parent or grandparent (reg 6.3(7)(c)). However, the claims of that divisional patent may be different to the claims of the parent. The construction of ss 13, 65 and 68 of the Act adopted in Britax leads to the result that an act of infringement may arise before any claims defining the infringement have been brought into existence.

76 Thirdly, I accept the appellants’ submission that the purpose of the combined operation of ss 13, 65, 68 and reg 6.3(7)(c) is to set limits to the window of time in which a patentee might obtain an enforceable right “subject” to the Act. This gives force to the opening words of s 13(1) by reference to the language of Chapter 11 and s 57. Several examples arise as to restrictions on the rights conferred pursuant to s 13. One is seen in the compulsory licence provision (s 133), which operates to derogate from or limit the exclusive rights conferred. Another is s 120(4), which provides a statutory limitation period, limiting the ability of a patentee (or exclusive licensee) to obtain relief in respect of infringing acts that occur during the term of the patent. Another arises in relation to s 57, to which I refer further below.

77 In my view, the language of s 122 provides a further example of a relevant restriction, which by implication is to limit the entitlement to relief for infringement of those rights to the date of grant. Section 122 is explicitly directed to the relief that a court may grant “for infringement of a patent”. Section 13 is in general terms, and is not specifically directed to relief. In my view the more specific provision subordinates the general, in circumstances where the general explicitly is expressed to be “subject to” the balance of the Act.

78 Fourthly, the construction adopted in Britax leads to the result that a person may be liable for the infringement of claims of some patents granted on divisional applications from a time before those claims were drafted or published. The construction that I prefer leads to the conclusion that the right of a patentee for relief for an act of infringement will be preceded by the grant of the patent and the publication of the specification and claims, regardless of whether the patent is based on a divisional application. The facts of the present case demonstrate such a position. In my view this approach is consistent with policy.

79 Disclosure of the invention to the public by the patentee is the consideration that the patentee gives for the grant by the crown of the monopoly. Lahore records at [5000]:

A patent is a temporary monopoly granted by the Crown to the patentee in return for the disclosure of the invention to the public in the patent specification. The term is derived from “Litterae Patentes” (letters patent), open letters so called because they were not sealed up but were exposed to view with the Great Seal attached to the bottom.

80 In No-Fume Ltd v Frank Pitchford & Co Ltd (1935) 52 RPC 231 at 243 in a passage cited with approval by the High Court in Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 8; (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [25], Romer LJ said:

[I]n other words, [it is essential] that the patentee should disclose his invention sufficiently to enable those who are skilled in the relevant art to utilise the invention after the patentee’s monopoly has come to an end. Such disclosure is, indeed, the consideration that the patentee gives for the grant to him of a monopoly during the period that the patent would run. …

81 The dual purpose of the claims was succinctly summarised by Gummow J in Rehm Pty Ltd v Websters Security Systems (International) Pty Ltd (1988) 81 ALR 79; (1988) 11 IPR 289 (Rehm) at 94-95 (where his Honour was addressing the Patents Act 1952 (Cth)) (emphasis added):

… As s 40 itself indicates, the task of the body of the specification is fully to describe the invention including the best method of performing it known to the applicant. The description primarily is addressed to “all and sundry who may wish to construct the device after the patent has expired”: Ludlow Jute Co Ltd v Low (1953) 70 RPC 69 at [76]. The function of the claims is to define the invention and mark out the ambit of the patentees’ monopoly, and primarily is addressed to potential rivals: see generally Fox H G, Canadian Law and Practice Relating to Letters Patents for Inventions, 4th ed, pp 165-6, 193-6.

82 In Clorox Australia Pty Ltd v International Consolidated Business Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 261; (2006) 68 IPR 254, Stone J said that:

18. … The patentee must define the invention with sufficient precision to permit the monopoly to be determined and allow the general public to identify from the words of the claims the conduct prohibited: British United Shoe Machinery Co Ltd v A Fussell & Sons Ltd (1908) 25 RPC 631 at 650-651. The public are entitled to be able to design around the monopoly claimed in a patent and therefore they must be able to determine reliably the scope of the claims: Beloit Technologies Inc v Valmat Paper Machinery Inc [1895] 24 RPC 705 at 720.

See also; Danisco A/S v Novozymes A/S (No 2) [2011] FCA 282; (2011) 91 IPR 209 at [37] (not relevantly reversed on appeal); Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No 4) [2013] FCA 162; (2013) 100 IPR 285 at [231] per Jagot J; Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCAFC 102; (2012) 204 FCR 494 at [43] per Keane CJ for similar statements.

83 The purpose of the claims is accordingly to define the invention, and mark out the ambit of the monopoly for the public, including trade rivals. This may notify rivals of the territory which is forbidden so that they can avoid or design around the scope of the monopoly. The significance of the complete specification becoming open to public inspection forms a necessary part of that purpose; until it becomes so open, trade rivals are unable to see the claims or to understand the scope of the monopoly asserted.

84 Fifthly, the continuation of this policy rationale on the part of the legislature is apparent from the language of s 57 of the Act.

85 The language of s 57(1) reflects an assumed state of affairs (emphasis added).

57 Effect of publication of complete specification

(1) After a complete specification relating to an application for a standard patent has become open to public inspection and until a patent is granted on the application, the applicant has the same rights as he or she would have had if a patent for the invention had been granted on the day when the specification became open for public inspection.

86 The balance of s 57 provides protection to potential infringers:

57 Effect of publication of complete specification

…

(3) Subsection (1) does not give the applicant a right to start proceedings in respect of the doing of an act unless:

(a) a patent is granted on the application; and

(b) the act would, if done after the grant of the patent, have constituted an infringement of a claim of the specification.

(4) It is a defence to proceedings under subsection (1) in respect of an act done:

(a) after the complete specification became open to public inspection; and

(b) before the patent request was accepted:

if the defendant proves that a patent could not validly have been granted to the applicant in respect of the claims (as framed when the act was done) that are alleged to have been infringed by the doing of the act.

87 Accordingly, the position under s 57 serves to give provisional retrospective entitlement to relief in respect of acts prior to grant, but only upon grant and only where the conditions of ss (3) and (4) are satisfied. A potential infringer has the opportunity to scrutinise the claims of the patent application once it becomes open for inspection. It may seek to work around the claims or conclude that the claims of the patent, if granted, would be invalid and accordingly proceed with its planned conduct. In each case, the policy considerations relevant to the drafting of claims are preserved by the operation of s 57.

88 Section 57 also tends to confirm that the construction advanced by the appellants is preferable. The assumption within the language of s 57(1) is that but for the exception provided therein, no relief for infringement is available prior to grant. Where retrospective relief is permitted prior to the date of grant, the protections identified in ss (3) and (4) are available.

89 Sixthly, on the construction adopted in Britax, a patentee of a divisional standard patent would be able to secure relief in respect of a period prior to publication if based on a parent or grandparent. Section 57 does not, by its terms, prevent a patentee of a standard patent granted on a divisional application from obtaining relief prior to the date upon which the application first became open to public inspection. This would provide such a patentee with greater rights for a patent based on a divisional application. If such additional rights were contemplated, I would expect that the Act would have more explicitly provided for that circumstance. No policy rationale is apparent for such an approach. I consider this anomaly to be an indication that the result of the construction adopted in Britax is not intended.

90 Seventhly, s 57 does not apply to innovation patents at all (whether granted on divisional applications or otherwise). In Britax, the Court relied on the fact that the amendments that introduced into the Act the innovation patent did not include a reference to innovation patents within s 57. Section 57(2) had provided an equivalent provision for petty patents, so that a patentee was able to sue in respect of acts of infringement upon the specification becoming open to public inspection. Section 57(2) was removed with the introduction of the innovation patent system. The Court found that by deciding not to include innovation patents within s 57, Parliament had deliberately decided that the date in respect of which an act of infringement could be the subject of suit was the date of the patent.

91 In this regard Middleton J drew upon the Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Patents Amendment (Innovation Patents) Bill 2000 (Cth). The Revised Explanatory Memorandum said, in respect of that change (emphasis added):

Item 28 – Subsection 57(2)

46. This item repeals subsection 57(2) of the Patents Act consequential to the repeal of the petty patent system. The subsection deals with the publication of petty patents prior to grant. This provision will not apply to innovation patents because innovation patents will only be published after grant.

92 In my view, contrary to his Honour’s finding, the final sentence of that paragraph supports the view that I have taken. As noted above, an innovation patent is accepted swiftly after a “formalities check” and then the complete specification is granted and made open to public inspection in the one step. No pre-grant opposition is available. There is no need for the exception provided by s 57. Substantive consideration of the specification only takes place upon certification. By contrast, a standard patent is not accepted by the Commissioner of Patents until after it has undergone a substantive examination, and then may be subject to potentially lengthy grant opposition. Under the Act before it was amended, a petty patent was also subject to a substantive examination before acceptance (former s 50). The Revised Explanatory Memorandum records (at 1, 5) that in deciding to abolish the petty patent the legislature had elected to remove the step of substantive examination before grant so as to speed up the progression of a second tier patent to grant.

93 Section 57 provides a means by which the patentee upon a granted patent may seek relief dating from the date when the complete specification became open for public inspection, once the patent is granted. Given the substantive changes made to the system by abolishing petty patents and introducing innovation patents in their stead, the ameliorative effects of s 57 were not required for innovation patents. In my view the premise of the conclusion in Britax is that, in the absence of s 57, the right to relief for infringement accrues from the date of the commencement of the term of the patent. For the reasons set out above, that view is not, with respect, supported by the language of Part 1 of Chapter 11 of the Act.

94 Further, in Britax the Court rejected a submission that its construction would give to divisional applications more extensive rights than their respective parent applications (at [21]).

95 However, the interpretation adopted in Britax reflects a dramatic shift in the policy underlying the grant of substantive rights pursuant to the Act. It leads to the unattractive result that the owner of a divisional innovation patent may file a divisional application upon a much older standard patent and then sue for acts of infringement that took place well before the invention was defined in any claims. I would expect such a policy shift to have been clearly forecast in the language of the Act and in the secondary materials. No such shift is signalled in either.

96 Finally, the appellants raise the operation of s 129A as another example of an anomalous result. They submit that the Britax construction yields the result that the patentee may sue for infringing acts committed prior to certification but may not threaten infringement proceedings in respect of those acts prior to certification. I consider that this provides a further example of a consequence of the construction adopted in Britax which produces an anomalous result that is avoided by the construction that I have preferred.

97 Accordingly, I respectfully disagree with the conclusion reached in Britax and find that the relevant date for determining infringement of an innovation patent under the Act is the date of grant for the patent in suit.

2.6 Date of infringement – Ground 1

98 In ground 1 of the appeal, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that the appellants had infringed the claims of the Patents in the period from 5 September 2005 to the date of grant, in circumstances where neither of those patents were on the patent register during this period.

99 The System Patent was filed on 2 December 2010 and was granted on 16 December 2010. The Method Patent was filed on 16 August 2011 and granted on 15 September 2011. On the construction that I have adopted, the first date upon which the patentee was entitled to relief was the date of grant. Accordingly, to the extent that the primary judge concluded that the relevant date was earlier, I allow ground 1 of the appeal.

2.7 Innocent infringement – Ground 2

100 In ground 2 of the appeal, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that the defence to innocent infringement could not be made out during the period prior to the grant of the patents in suit.

101 Subsection 123(1) provides:

(1) A court may refuse to award damages, or to make an order for an account of profits, in respect of an infringement of a patent if the defendant satisfies the court that, at the date of the infringement, the defendant was not aware, and had no reason to believe, that a patent for the invention existed.

102 In this connection, the requisite knowledge is of “a patent for the invention”, “patent”, being a granted patent, and “the invention” being the invention as claimed in that patent (as I have noted, an invention can only be infringed if all of the features of the invention as claimed have been taken by the infringing act).

103 The primary judge found at [420] (emphasis added):

In relation to innocent infringement, the onus is on the respondents to show that, at the date of infringement, they were not aware and did not have reason to believe that a patent for the invention existed. This defence has no prospect of success. The respondents were informed promptly of the existence of the Patents at the time that those Patents were granted and, in respect of the period prior to grant, they were aware of the existence of the earlier patent applications on which the applicants’ claim for the relief depends.

104 I have found that a defendant cannot infringe an innovation patent in respect of acts done before it is granted. That is sufficient to dispose of ground 2 in favour of the appellants.

105 However, regardless of this conclusion, I would have found in favour of the appellants on this ground. A defendant cannot be aware of a patent, let alone the invention as claimed in the claims of a patent, before it is brought into existence.

106 The complete specifications of the Patents were filed on 2 December 2010 (System Patent) and 16 August 2011 (Method Patent). It was not until the Patents were granted on 16 December 2010 and 15 September 2011 that the complete specification of each became open for public inspection. Prior to those dates the appellants had no means of knowing that “a patent for the invention existed”.

107 In the present case it was not in dispute that the first date upon which the appellants were aware of the Patents was when they were notified by AMC that they had been filed in October 2011. It was from that date that the defence of innocent infringement ceased to be available.

2.8 Claim for additional damages – Ground 3

108 In ground 3 the appellants contend that the error made in determining the date from which infringement occurred permeates the reasoning of the primary judge in his assessment of additional damages pursuant to s 122(1A) of the Act. This is said to be apparent from [428] of his Honour’s reasons, which summarised earlier conclusions reached by the primary judge concerning the conduct of the appellants well before the date of grant.

109 The respondents submit in answer that the primary judge correctly took into account a continuum of the appellant’s conduct running from prior to the date of grant and throughout the trial. They draw particular attention to the primary judge’s findings at [386] to the effect that Mr Kleyn had falsely claimed to have transferred proprietary rights to the ORIshot Tool to Coretell (a company of no assets) from Mincrest (a company with assets) in November 2006. His Honour found at [386] that this was a recent invention tailored for the purposes of this litigation. The respondents also submit that s 122(1A)(e) enabled the Court to take into account all relevant matters, which include those findings.

110 Subsection 122(1A) provides:

122 Relief for infringement of patent

…

(1A) A court may include an additional amount in an assessment of damages for an infringement of a patent, if the court considers it appropriate to do so having regard to:

(a) the flagrancy of the infringement; and

(b) the need to deter similar infringements of patents; and

(c) the conduct of the party that infringed the patent that occurred:

(i) after the act constituting the infringement; or

(ii) after that party was informed that it had allegedly infringed the patent; and

(d) any benefit shown to have accrued to that party because of the infringement; and

(e) all other relevant matters.

111 This ground of appeal must be understood in the context of the litigation as a whole. At an early stage in the proceedings, interlocutory orders were made separating the issues of liability for infringement from the issue of quantum of any damages, in the event that infringement was found. As his Honour observed at [429], his findings on the subject of additional damages went to entitlement to such relief. The more nuanced question of quantum, which is assessed by reference to the factors identified in s 122(1A), is yet to be resolved.

112 Before the primary judge, the respondents contended that the appellants engaged in multiple acts of infringement over a number of years going back to September 2005. For the reasons previously explained, there could be no infringement before 16 December 2010, when the System Patent was granted.

113 The primary judge found at [428]-[429]:

[428] I consider that the infringement was flagrant. I accept that the conduct after becoming aware of the allegation of infringement, which has been outlined above, was an artificial contrivance perpetuated through the course of the trial at considerable length. The benefit of the infringement in the sales of the ORIshot Tool have been significant. The credibility and conduct of Mr Kleyn and, therefore, the respondents generally, on the topics in issue would certainly not assist the respondents in resisting an award of additional damages.

[429] Beyond reiterating those observations, which do no more than restate conclusions and findings that I have already made, the applicants would be entitled to an award for additional damages, but, again, the resolution of this would be deferred to any hearing of quantum.

114 It is clear from those paragraphs that the primary judge considered that the infringements alleged against the appellants were flagrant and that there were other matters that would justify an award of additional damages pursuant to s 122(1A). It seems likely that the flagrancy finding made was affected by his Honour’s mistaken view that the appellants commenced to infringe some years prior to the grant of the System Patent in September 2005.

115 The question whether the appellants’ infringements were flagrant should therefore be reconsidered by the primary judge when his Honour assesses damages. Nothing I have said is intended to suggest that a finding of flagrancy may not be open in this case.

116 As to Mr Kleyn’s evidence concerning the alleged transfer of proprietary rights in the ORIshot Tool from Mincrest to Coretell, I do not accept that this was not an irrelevant matter. His Honour was entitled to have regard to Mr Kleyn’s conduct in giving such evidence under s 122(1A)(e) and perhaps also s 122(1A)(c). The weight to be given to those matters in assessing the quantum of any additional damages that may be awarded is yet to be determined.

3. ACCESSORIAL LIABILTY – GROUND 6

117 In ground 6 of their appeal, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that Mincrest (second appellant and second respondent below) and Kleyn Investments (fourth appellant and fourth respondent below) were liable for direct and indirect infringement. This ground is also said to turn upon the findings as to the relevant date from which infringement can occur.

118 The point on appeal insofar as it concerns Kleyn Investments is concerned may be addressed briefly. Having regard to a detailed analysis of its conduct, his Honour found that Kleyn Investments had been involved in a common design with the other corporate respondents sufficient to lead to the conclusion that they had each directly and indirectly infringed each of the System Patent and the Method Patent. The acts of infringement were found to have continued after 16 December 2010 and until the expiry of the Patents on 5 September 2013. These findings are sufficient to warrant his Honour’s conclusion that Kleyn Investments is liable for patent infringement, even allowing for my finding that the first date upon which the Patents could be infringed was on 16 December 2010 and 15 September 2011 respectively for the System and Method Patents. The question of the quantum of Kleyn Investment’s liability for activities after those dates remains to be determined following the hearing on pecuniary relief.

119 The position in relation to Mincrest is less straightforward.

120 The appellants submit that by a statement of agreed facts dated several weeks before the commencement of the hearing before the primary judge, it was agreed that Mincrest ceased trading in approximately February 2010 (agreed fact). That agreement was recorded in the judgment at [57]. The appellants submit that had the primary judge addressed the liability of Mincrest having regard to infringing activities that took place only after the grant of the patents in suit (in December 2010 and September 2011), then his Honour was bound to find that Mincrest was not liable, because by then Mincrest had ceased to trade.

121 The respondents submit that the primary judge considered the whole of the evidence in relation to Mincrest and concluded that the purported transfer of the assets of Mincrest to Coretell was a sham and a recent invention for the purposes of the litigation. His Honour found not only that Mincrest had continued to be involved in dealings with the ORIshot Tool after November 2006 (when Mr Kleyn’s evidence was that he began ostensibly trading through Coretell), but that there was no effective assignment of the interests of Mincrest, and that Mincrest continued even at the date of judgment to own the intellectual property in the ORIshot Tool and any associated assets. Accordingly, the respondents submit that in the circumstances, his Honour was correct to set to one side the agreed fact and decide the matter on the weight of the evidence.

122 The primary judge made a series of findings of fact that led to the conclusion at [392] that there was no effective assignment from Mincrest. It was these findings that resulted in his conclusion that Mincrest was liable as an accessory. His Honour’s conclusion at [392] follows detailed consideration of a number of factual matters raised below by the respondents and involved credit findings against Mr Kleyn (for example [383], [386] – [387], [396], [398]). His Honour was left (emphasis added):

371. … with the strong impression that the Notional Assignments [being assignments of assets which were alleged to infringe the patents in suit] were totally defective and that they were indeed simply concepts thought up after the event in order to minimise exposure if patent liability was established.

He concluded that it was clear on the evidence that Mincrest continued up until trial to be involved in dealing with ORIshot. His Honour found that in the absence of any effective assignment, all of the intellectual property rights and other assets continue to be held by Mincrest and that Mincrest entered into a distributorship agreement with DHS in November 2011. He concluded that each of the corporate respondents has authorised, procured, induced and used or engaged in a common design with customers to use the ORIshot Tool thereby indirectly infringing each of the System and Method Patents.

123 Section 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) provides:

191 Agreements as to facts

(1) In this section:

agreed fact means a fact that the parties to a proceeding have agreed is not, for the purposes of the proceeding, to be disputed.

(2) In a proceeding:

(a) evidence is not required to prove the existence of an agreed fact; and

(b) evidence may not be adduced to contradict or qualify an agreed fact;

unless the court gives leave.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply unless the agreed fact:

(a) is stated in an agreement in writing signed by the parties or by Australian legal practitioners, legal counsel or prosecutors representing the parties and adduced in evidence in the proceeding; or

(b) with the leave of the court, is stated by a party before the court with the agreement of all other parties.

124 The document recording the agreed fact purported to be a statement of agreed facts of the kind referred to in s 191. The Court was informed that the statement of agreed facts was filed but not adduced in evidence. Nor was the statement of agreed facts signed by the parties’ legal representatives. It follows that neither of the requirements imposed by s 191(3)(a) was satisfied in this case and s 191 was never engaged.

125 The parties’ failure to ensure that the requirements of s 191 were complied with is significant. Had the document been signed and adduced into evidence as required by s 191(3)(a), it would not have been open to either party to adduce any evidence to contradict or qualify the agreed fact without the leave of the Court. But in circumstances where s 191(3) was not engaged, the leave requirement in s 191(2) did not apply. It was therefore open to the primary judge to decide the case against Mincrest on the evidence as a whole rather than on the basis of an agreed fact that was inconsistent with other evidence.

126 Accordingly, I reject the appeal insofar as it concerns the position of Mincrest.

4. INVALIDITY – EXTERNAL FAIR BASIS AND PRIORITY DATE – GROUNDS 15 AND 16

127 Grounds 15 and 16 of the appeal concern what is often called “external fair basis” and novelty. The appellants contend that the priority date should be found to be deferred to after 3 September 2004. If that is so, then it is common ground that the Patents are invalid in view of the publication of the ACT Tool (the tool which has been developed and commercialised by AMC for the orienting of core samples, described in the evidence as the ACT Tool or Ace Core Tool). As noted above, the Patents are divisional applications. It is not in issue that, as his Honour found at [440] – [443], any allocation of a priority date based on the Provisional Application arises by operation of ss 43 and 79B of the Act and reg 3.12 of the Regulations. The broad question is whether the claims of the patents in suit are fairly based on the matters disclosed in the Provisional Application.

128 The appellants contend first, that the primary judge made a finding that the claims of the System Patent and the Method Patent are not limited to an orientation device in which the components are present in one physical unit but encompass multi-component tools. Having done so, they submit that his Honour erred in finding that those claims were fairly based on the disclosure of the Provisional Application because, properly construed, that Application disclosed an invention limited to single unitary device (unitary device argument).

129 Secondly, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in holding that the “fifth aspect of the invention” referred to in the Provisional Application provided an adequate disclosure of the invention claimed in the System Patent, because that aspect defines the invention by reference to function only, and not by reference to any device at all (functional disclosure argument).

130 Thirdly, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that there was sufficient disclosure in the Provisional Application of a device or method involving holding a core sample “in fixed relation to the inner tube”, when the Provisional Application included no reference to such a feature or function (held in fixed relation argument).

131 The respondents answer these allegations by relying, in particular, upon the disclosure of the fifth embodiment of the invention in the context of the disclosure of the provisional specification as a whole.

132 Subsection 43(2) of the Act provides that the priority date of a claim is either the date of filing of the specification or, where the Regulations provide for the determination of a different date as the priority date, the date determined under the Regulations. As noted, the Patents were filed as divisional applications pursuant to the terms of s 79B of the Act.

133 Regulation 3.12 relevantly provides:

3.12 Priority dates generally

(1) Subject to regulations 3.13 and 3.14 and subregulation (2), the priority date of a claim of a specification is the earliest of the following dates:

(a) the date of filing of the specification;

(b) if the claim is fairly based on matter disclosed in 1 or more priority documents, the date of filing the priority document in which the matter was first disclosed;

(c) if the specification is a complete specification filed in respect of a divisional application under section 79B of the Act and the claim is fairly based on matter disclosed in the specification referred to in paragraph 79B (1) (a) of the Act — the date mentioned in subregulation (2C);

…

…

(2C) The date for a specification to which paragraph 3.12 (1) (c) applies is the date that would have been the priority date of the claim if it had been included in the specification referred to in paragraph 79B (1) (a) of the Act.

…

134 There is a nuanced difference between the test for fair basis arising under s 40(3) of the Act and the test for determining priority dates pursuant to reg 3.12(1) above. The latter requires that the claim be “fairly based on matter disclosed in the specification” and the former requires that the claim described be “fairly based on the matter described in the specification” (emphasis added). A Full Court of this Court succinctly stated the practical effect of the difference in Multigate Medical Devices Pty Ltd v B Braun Melsungen AG [2016] FCAFC 21; (2016) 117 IPR 1 at [189] (citations omitted; italics in original):

… There are two linguistic differences in the phrase used for external fair basis. First, the definite article is omitted. Second, the reference is to what is disclosed rather than what is described. So, the absence of the definite article makes it plain that external fair basis can arise if some part of the overall disclosure made in the prior specification discloses the relevant matter. … Further, the use of “disclosed” rather than “described” connotes greater flexibility in the test for external fair basis in terms of ascertaining from the prior specification the requisite disclosure.

135 Whilst one must bear in mind this nuance, otherwise, the test for external fair basis is essentially the same as that set out definitively in Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 58; (2004) 217 CLR 274 (Doric No 1), where the High Court held that the requirement that a claim or claims be fairly based on matter described in the specification within s 40(3) of the Act requires a “real and reasonably clear disclosure” of what is claimed. At [69] the High Court referred with approval to the following passage in the judgment of Gummow J in Rehm at 95:

The circumstance that something is a requirement for the best method of performing an invention does not make it necessarily a requirement for all claims; likewise, the circumstance that material is part of the description of the invention does not mean that it must be included as an integer of each claim. Rather, the question is whether there is a real and reasonably clear disclosure in the body of the specification of what is then claimed, so that the alleged invention as claimed is broadly, that is to say in a general sense, described in the body of the specification.

136 The relevant inquiry is to ascertain what that patentee discloses to be the invention, which involves consideration of the whole document. The fact that some words in the specification match the claims in what is referred to as a “consistory clause” will not be determinative. As the High Court said in Doric No 1 at [99]:

… the correct position is that a claim based on what has been cast in the form of a consistory clause is not fairly based if other parts of the matter in the specification show that the invention is narrower than that consistory clause. The inquiry is into what the body of the specification read as a whole discloses as the invention [Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 612-613]. An assertion by the inventor in a consistory clause of that of which the invention consists does not compel the conclusion by the court that the claims are fairly based nor is the assertion determinative of the identity of the invention. The consistory clause is to be considered by the court with the rest of the specification.

4.3 The Provisional Application

137 The Provisional Application is entitled “Core Sample Orientation”. The field of the invention is said to relate generally to identification of core sample orientation and, more particularly, to an orientation device for providing an indication of the orientation of a core sample relative to a body of material from which the core has been extracted. It also relates to a method for achieving this.

138 The “Background Art” section explains that core samples are obtained through a core drilling operation during which a core is generated using a core drill which consists of outer and inner tube assemblies. A cutting head is attached to the outer tube assembly. During a drilling operation, the core progressively extends along the inner tube. When a sample is required, the core is fractured from the base material and retrieved from the drill hole. Once out of the hole, the sample may be removed and subjected to analysis.

139 The “Background Art” section goes on to explain that typically the core drilling is performed at an angle to the vertical, making it desirable to have an indication of the orientation of the core sample relative to the base material from which it was extracted.