FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Appellant | ||

AND: | RECKITT BENCKISER (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD ACN 003 274 655 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Order 1 of the orders made on 29 April 2016 be set aside.

3. In lieu thereof, for the contraventions of s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia within 30 days a pecuniary penalty of $6,000,000.

4. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the appeal and of the hearing below, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 This is an appeal by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) from orders made by a judge of this Court imposing a civil penalty of $1.7 million on Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (Reckitt Benckiser) for conduct in trade or commerce liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics or suitability for purpose of pain killers known as the Nurofen specific pain range.

2 The maximum penalty for each contravention of s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL, set out in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA)) is $1.1 million (s 224(3)).

3 Over a period of nearly five years from 1 January 2011 to 10 December 2015, Reckitt Benckiser repeatedly engaged in the contravening conduct, selling 5.9 million packets of the so-called Nurofen specific pain range products (the conduct had in fact started in 2007, but the contravention period started on 1 January 2011 due to the limitation period in s 228(2) of the ACL). Accordingly, Reckitt Benckiser must have engaged in the proscribed conduct at least 5.9 million times. As such, the theoretical maximum penalty for the contraventions, as the primary judge said, was “many, many millions of dollars”. As we discuss below, in a practical sense, the overall maximum penalty was so great that there was no maximum penalty.

4 For the reasons that follow, the appeal must be upheld, the penalty imposed by the primary judge set aside, and in lieu thereof Reckitt Benckiser must pay a pecuniary penalty of $6 million for the contraventions.

Overview

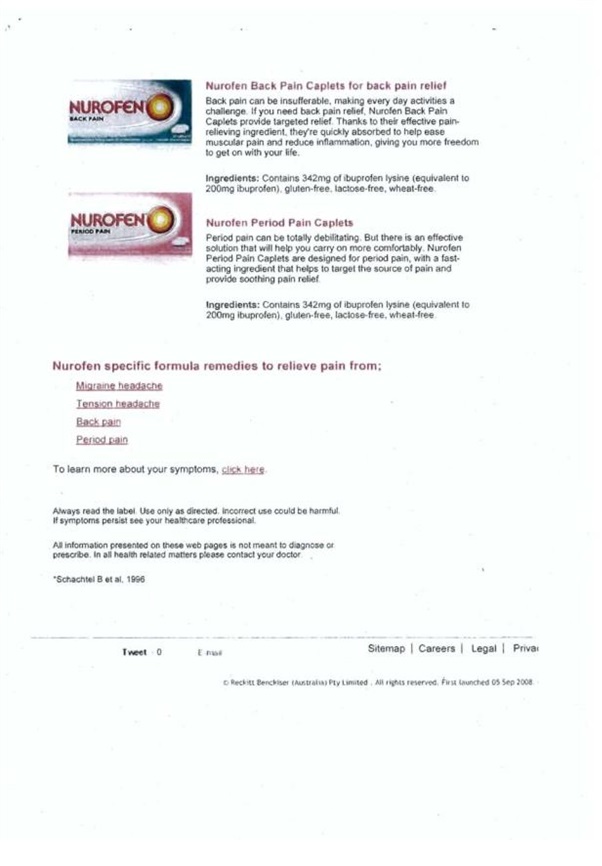

5 The proceeding concerned conduct by Reckitt Benckiser consisting of representations made on product packaging and two webpages about a purported range of four ostensibly different Nurofen pain medications said to be “targeted” to treat four different types of pain, namely “migraine pain”, “tension headache”, “period pain” or “back pain”. In fact, there was no difference between any of the four products. The products all provided in the human body a dose of active ingredient equivalent to 200mg of ibuprofen. The only difference was the packaging and marketing. Moreover, the products were sold at about double the price of standard Nurofen which also provided a dose of 200mg of ibuprofen. The price premium of the products above standard Nurofen was part and parcel of Reckitt Benckiser’s overall marketing of the products.

6 Contrary to the representations, ibuprofen does not “target” any particular kind of pain. It treats all types of pain in precisely the same way. Any representation to the effect that a medication in which the sole active ingredient is (or is the chemical equivalent of) ibuprofen “targets” pain is inherently misleading, at least when combined with any reference to any specific type of pain. This is because the overall effect is to convey the false impression that the medication is capable of treating the specific type of pain differently from any other type of pain.

7 With 5.9 million sales of the four products over five years (yielding revenue to Reckitt Benckiser of about $45 million), millions of consumers were liable to be misled by the representations on the packaging that each product was targeted to treat a particular type of pain when, in fact, they were all identical products. An unknown number of consumers were also liable to be misled over at least 18 months by the representations on the webpages purporting to help consumers to “choose” which of the four products was “right” for treating different types of pain. In fact, there was no choice involved because there was no difference between the four products beyond their packaging and marketing.

8 Reckitt Benckiser made very late admissions, only at trial, to civil contraventions for misleading or deceptive conduct under s 18 of the ACL, as well as civil penalty contraventions under s 33 of the ACL for conduct liable to mislead the public as to the nature, character or suitability for purpose of the four identical products. This appeal relates only to the civil penalty contraventions under s 33 of the ACL, and ultimately only in relation to the quantum of the penalty imposed by the primary judge.

9 Our reasons for determining that the appeal must be allowed and a penalty of $6 million imposed on Reckitt Benckiser for the contraventions follow.

The packaging and website representations

10 In the statement of agreed facts and the reasons for judgment of the primary judge (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 1408 in respect of liability and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2016] FCA 424 in respect of penalty), the four products are referred to as the Nurofen “specific pain relief range” or the Nurofen “specific pain relief products”. While so identified for convenience, the references disclose the misleading character of the packaging and the webpages. The products masquerade as pain relief for specific pain (“migraine pain”, “tension headache”, “period pain” or “back pain”), but they are not specific in any way. They are all the same product delivering the same dose of ibuprofen in the same way.

11 It was an agreed fact that the active ingredient of all of the products, ibuprofen, acts on pain in the body by inhibiting the production of pain causing chemicals known as prostaglandins which occur in the central nervous system and at peripheral sites around the body. When there are locally elevated levels of prostaglandins, the nerve endings in that area trigger pain signals to the central nervous system. Ibuprofen acts generally to inhibit prostaglandin production irrespective of the location of the pain (for example, back pain) or the type of the pain (for example, migraine pain, tension headache, or period pain).

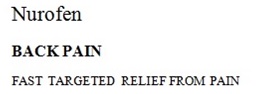

12 The packaging of each of the products is shown below.

13 It will be seen that each package identifies itself as “Nurofen”, underneath which is the identification of the purported specific pain type (“migraine pain”, “tension headache”, “period pain” or “back pain”). Underneath this again is the statement “fast targeted relief from pain”. Each package also contains a statement that the product “is fast and effective in the temporary relief of pain [“and/or inflammation” in the back pain product] associated with”, followed by the purportedly relevant specific pain type. The Nurofen migraine pain product also contains an instruction “Dosage: Take with water at first onset of migraine”. The Nurofen tension headache product contains an instruction “Dosage: Take with water at first sign of tension headache”.

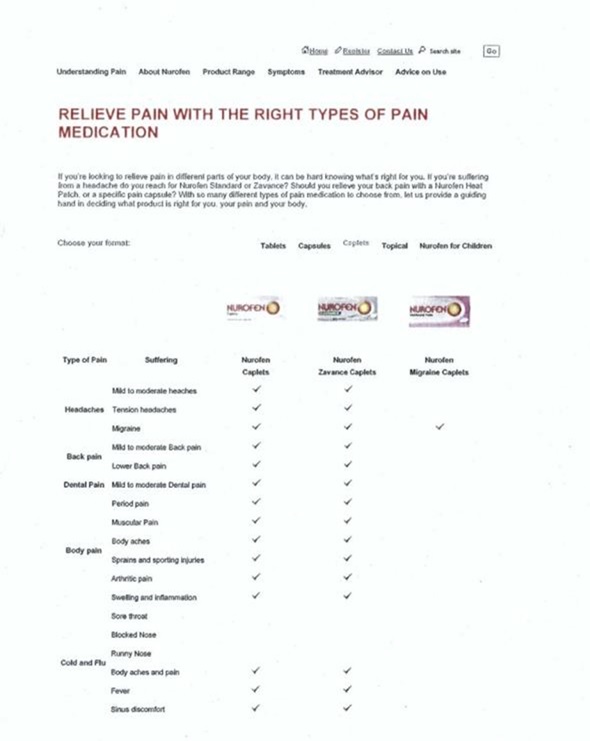

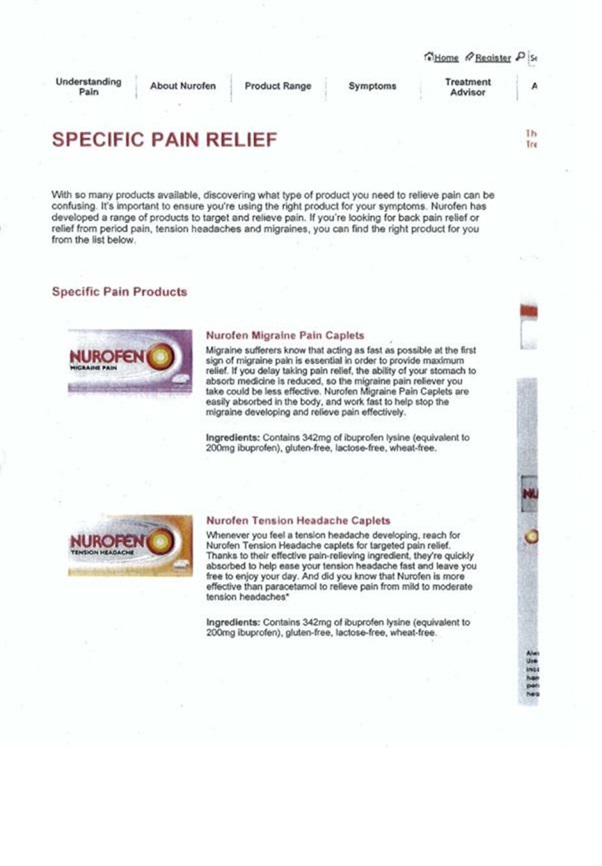

14 The webpages are annexed to these reasons as Annexure A. They included statements “Relieve pain with the right types of pain medication”, “Specific pain relief”, and “targeted relief”. As one example, the Nurofen migraine product is shown as part of a table compared to Nurofen caplets (referred to as standard Nurofen, a product the active ingredient of which is 200 mg of ibuprofen) and Nurofen Zavance, a product with a different chemical, sodium ibuprofen dehydrate, about which there is no evidence except it is said on the packaging of that product to be equivalent to 200mg ibuprofen and to be “Absorbed up to twice as fast as standard Nurofen”. The standard Nurofen product is shown with ticks against various pain “types” whereas the Nurofen migraine product is shown with a single tick against “Migraine”. In another comparison table, the Nurofen Tension Headache product is shown with a tick against only “Tension headaches”, the Nurofen Back pain product is shown with ticks against only “”Mild to moderate Back pain” and “Lower Back pain”, and the Nurofen Period Pain product is shown with a tick against only “Period pain”. No ticks appear against any other “pain type” in the table, such as “body aches and pain”, an omission that enhanced the misleading impression by suggesting a material difference when there was none.

15 In his liability judgment, the primary judge found that by its packaging of the products Reckitt Benckiser from 1 January 2011 had represented that:

…each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range:

• was specifically formulated to treat the particular type of pain specified on the packaging relevant to that product; and

• solely or specifically treated the particular type of pain specified on the packaging relevant to that product,

when in fact:

• each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range contains the same active ingredient, namely ibuprofen lysine 342mg;

• the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) approved indications for each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range are the same;

• each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range is of the same formulation; and

• no product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range is any more or less effective than the others in treating any of the symptoms shown on the packaging of the products in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range.

16 The primary judge also found in the liability judgment that, by its webpages, Reckitt Benckiser between at least December 2012 and around May 2014 had represented that:

each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range:

• was specifically formulated to treat the particular type of pain specified on the packaging relevant to that product; and

• solely or specifically treated the particular type of pain specified on the packaging relevant to that product,

when in fact:

• each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range contains the same active ingredient, namely ibuprofen lysine 342mg;

• the ARTG approved indications for each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range are the same;

• each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range is of the same formulation; and

• no product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range is any more or less effective than the others in treating any of the symptoms shown on the packaging of the products in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range.

Key events

17 The products were registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) between 2003 and 2007. From the last registration of the Nurofen Back Pain product in 2007 Reckitt Benckiser marketed and sold the purported “Nurofen specific pain range”.

18 In 2010, consumer advocacy group Choice “awarded” Reckitt Benckiser a “Shonky Award” for “pain in the hip pocket” for the purported range. Details of the Shonky Award included the following information disclosed at [74]-[75] of the penalty judgment:

Nurofen

Shonky for pain in the hip pocket? Nurofen

Got a headache?

Backache? Neck ache?

A trip to your pharmacy or supermarket reveals there are specific painkillers for all sorts of pains: back pain, tension headache pain, migraine pain, period pain, osteoarthritis pain, neck pain, little toe pain… Panadol has a few pain-specific products, but Nurofen has more, with a range of caplets for migraine, back, tension headache and period pain. Yet a closer look at the ingredients shows they’re identical from product to product.

So does the back pain version somehow magically go straight to your back – and only your back – as soon as you’ve swallowed it? Could you, say, choose to treat only your back pain while keeping your headache? If you want to treat both, do you need to take a dose of each? The answers are no, no and definitely no. When you take these pain killers, the active ingredient spreads through your whole body, attacking whatever pain it comes across, wherever it is. Filling up your medicine cabinet with different painkillers for every type of pain is unnecessary, not to mention wasteful, should they expire before you’ve used them all. But the shonkiest aspect of this type of marketing is that the fast-acting painkillers labelled for specific pain types are more expensive – costing almost twice as much in some stores we surveyed – than their “all-pain” fast-acting equivalent, Zavance caplets, which contain a comparable fast-acting form of ibuprofen. Our advice? Stick with Zavance – and see your doctor if pain persists. See the video.

19 In his penalty judgment at [76], the primary judge rejected Reckitt Benckiser’s submission that it was not aware of the Shonky Award it received for the purported Nurofen specific pain range. That conclusion was not challenged on appeal. Nor were the further adverse findings referred to below.

20 Reckitt Benckiser continued to market and sell the products without any material change after the Shonky Award.

21 In 2012, two complaints about the purported Nurofen specific pain range were made to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). These complaints were referred to the TGA’s Complaints Resolution Panel.

22 Reckitt Benckiser published the webpages from at least December 2012 to May 2014, and continued to market and sell the products without any material change.

23 On 18 April 2013, the purported Nurofen specific pain range featured on the television show “The Checkout”. The show was critical of Reckitt Benckiser for selling products that claim to work on specific pain at a higher price than other products. At [83] of the penalty judgment, the primary judge rejected Reckitt Benckiser’s submission that it was not aware of the show, saying that:

It is a very simple inference to conclude, as I do, that Reckitt Benckiser was aware of the program about which it had been contacted and to which it responded through a public relations company.

24 Reckitt Benckiser continued to market and sell the products without any material change thereafter.

25 On 12 June 2013, the TGA’s Complaints Resolution Panel made findings that:

in the absence of clear and prominent statements to the contrary, the use of the descriptive names Nurofen Back Pain, Nurofen Migraine Pain, Nurofen Period Pain, and Nurofen Tension Headache Pain in the advertisement would convey to an ordinary and reasonable consumer that:

a. The products so named were different in their ingredients or effects, and did not differ solely because of the consumer to which advertisements about them were directed;

b. The advertised products would have an effect in the named area or site of pain, and would not have an effect on other pain or act elsewhere in the body other than in the named area.

26 Shortly after this time, one of Reckitt Benckiser’s senior management, the Australian Regulatory and Medical Affairs Director, consciously decided to continue to sell the products under the same packaging and website representations pending a review of this decision by a delegate of the Secretary of the Department of Health.

27 Between July 2013 and October 2014, the ACCC requested documents and information from Reckitt Benckiser in respect of the ACCC’s investigation of the products. Reckitt Benckiser complied with these requests.

28 On 11 April 2014, the Secretary of the Department of Health ordered Reckitt Benckiser to withdraw any representations that implied that any two or more Nurofen products that contain equivalent ibuprofen quantities and include the same product specific indications on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods; (i) are effective only in treating a particular condition or conditions or pain in a particular part or parts of the body; or (ii) are not effective in treating other conditions or pain in other parts of the body. As the primary judge noted at [79] of the penalty judgment the delegate explained her reasoning in part as follows:

In order to ensure that consumers are not misled, I consider that it is necessary to order [Reckitt Benckiser] to withdraw any representations, including implied representations, that imply that any two or more Nurofen products that contain equivalent quantities of ibuprofen and include the same product indications, are effective only in treating particular conditions or pain in particular parts of the body and/or are not effective in treating other conditions or pain in other parts of the body.

29 Reckitt Benckiser removed the webpages within a month of these orders but continued to market and sell the products without any material change.

30 On 17 December 2014, in the context of the ACCC’s investigation, Reckitt Benckiser wrote to the ACCC. This letter records that:

Reckitt Benckiser’s point of view is that the labelling of each product, considered alone, is accurate.

31 On 4 March 2015, the ACCC filed its fast track application commencing this proceeding.

32 The hearing on liability was scheduled for 9 and 10 December 2015. Reckitt Benckiser, by its response filed on 22 April 2015, denied the substantive allegations against it and that the ACCC was entitled to any relief.

33 Throughout the proceedings and until 10 December 2015, Reckitt Benckiser continued to market and sell the products without any material change.

34 On the first day of the liability hearing, 9 December 2015, Reckitt Benckiser indicated for the first time that it would make admissions and consent to the making of orders against it to the effect it had contravened the ACL (ss 18 and 33) and was liable to a civil penalty under s 33 for conduct liable to mislead the public as to the nature, character or suitability for purpose of the four identical products. The admissions were set out in an amended response to the fast track application dated 10 December 2016, which was filed on the second day of the hearing on liability. At the same time, to enable current stock of the products to continue to be sold, Reckitt Benckiser and the ACCC agreed on an interim amendment to the packaging of the products (affixed by means of a sticker).

In the court below

35 As noted, on 10 December 2015 Reckitt Benckiser admitted that both the packaging and website representations constituted:

(1) misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to s 18 of the ACL; and

(2) conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to nature, characteristics and/or suitability for purpose contrary to s 33 of the ACL.

36 Reckitt Benckiser did not admit that the packaging and webpage representations were in fact false or misleading with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of the four identical products contrary to s 29(1)(g) of the ACL, another civil penalty provision. Upon the ss 18 and 33 contraventions being admitted, the ACCC did not press the s 29(1)(g) allegations. Accordingly, the civil penalty case was brought upon the basis that the representations were liable to mislead in contravention of s 33 of the ACL, rather than that they were in fact false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL.

37 Acceptance of a guilty plea to a lesser offence is well known to the criminal law, as are the consequences for sentencing in any such case. A sentencing court cannot impose a sentence for a greater offence than that charged and either admitted or proven: R v De Simoni (1981) 147 CLR 383 at 389. Whether or not the principle in De Simoni applies to civil penalty proceedings (an issue not addressed by the parties and which we do not decide), we proceed on the basis that the primary judge’s task was to decide the appropriate penalty in respect of the contravening conduct – being the conduct liable to mislead the public as to nature, characteristics and/or suitability for purpose contrary to s 33 of the ACL.

38 On 11 December 2015, the primary judge made orders including declarations of contravention, injunctions restraining like conduct for a period of three years, orders requiring corrective adverting and website notices, and in respect of Reckitt Benckiser’s compliance programs.

39 On 12 April 2016, a contested penalty hearing took place, with further submissions provided after the hearing.

40 It is common ground that the primary judge correctly identified the requirements of s 224 of the ACL (penalty judgment at [21]) by which the court may order payment of a pecuniary penalty for contravention of, relevantly, s 33 of the ACL. Section 224(2) of the ACL provides that:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

41 On 29 April 2016, the primary judge ordered Reckitt Benckiser to pay the Commonwealth within 30 days a pecuniary penalty of $1.7 million for the contraventions of s 33 of the ACL, and provided reasons.

42 For the purposes of the penalty hearing, the parties signed a statement of agreed facts and admissions pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), with numerous attachments. A number of other documents were also tendered.

43 The ACCC submitted, and it is the fact, that the unchallenged findings of the primary judge included the following matters (the references to PJ being to the penalty judgment):

(a) the contraventions continued for a period of almost 5 years (PJ [47]);

(b) the contraventions were made as part of a general marketing approach to profit (PJ [47]);

(c) the contravening conduct was widespread (the Nurofen Specific Pain Relief products were available at 5,500 pharmacies and 3,000 other retail outlets) (PJ [48]);

(d) in the period of contravention, the respondent sold approximately 5.9 million units of Nurofen Specific Pain Relief products (PJ [66]);

(e) the respondent was a large corporation with a large share of the market for oral analgesics in Australia (PJ [50]);

(f) the respondent earned revenues of $45 million … from the sale of the Nurofen Specific Pain Relief products in the contravening period (PJ [66]);

(g) the marketing strategy was developed and implemented by senior management including personnel in regulation, sales and marketing and legal (PJ [71]);

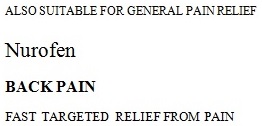

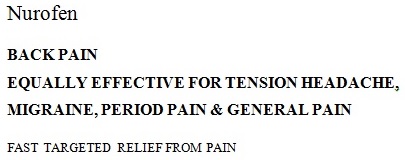

(h) the respondent’s compliance programs failed at basic levels (PJ [70]) and its compliance program made no reference to the ACL (PJ [73]);

(i) there were obvious warnings of the likelihood of the products misleading consumers arising from criticisms by consumer groups, TGA complainants and the media, and from decisions of the TGA itself, and the respondent was aware of those warnings (PJ [74] – [83]);

(j) the respondent continued to sell the Nurofen Specific Pain Relief products in their contravening packaging despite those obvious warnings and despite the ACCC commencing these proceedings; and

(k) the respondent had previously contravened s 18 of the ACL in respect of a false representation on the packaging of a different product (PJ [89] – [90]).

Nature and scope of appeals to a Full Court and the need for error to be demonstrated

44 Given the range of issues raised in this appeal, it is convenient to restate the governing principles. This is especially so because this is an appeal concerning the imposition of a civil penalty, which has certain features in common with criminal sentencing, but as noted in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 326 ALR 476 (the CFMEU civil penalty case) at [51]-[61], there are some important and fundamental differences, especially in relation to the purpose behind imposing a civil penalty. The dominant common feature is that determining both a sentence and a civil penalty usually involves, and in this case did involve, a difficult and complex process of multi-factorial decision-making, where the result is arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis”, addressing many conflicting and contradictory considerations (Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [74]-[76]). Those paragraphs were quoted with approval in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [37]. This integrated and holistic approach, requiring the weighing up of all relevant factors into a final result, often makes the process of appellate review difficult, particularly for an appellant seeking to identify and establish error in the reasoning process and outcome, or sometimes the outcome alone.

45 Appeals to this Court are by way of a rehearing (Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [20]). An appeal by way of rehearing requires this Court to decide the case for itself as to both facts and law and give effect to its own judgment (Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 552). However, this does not remove the need to find error on appeal before intervening (Branir at 435 [21]). In practice, the application of these principles may involve accepting the findings of the trial judge, especially factual findings, including as to the reliability and credit of witnesses and the weight that should be given to competing evidence, unless shown to be wrong (Cabal v United Mexican States [2001] FCA 427; (2001) 108 FCR 311 at [223]-[224], quoted with approval in Branir at [23]). However it should be observed that as there was no oral evidence in this case and all the representations were before this Court in documentary form, this Court is under no disadvantage compared to the primary judge in relation to consideration of the facts and evidence. The requirement for error to be established nevertheless remains.

46 In Costa v Public Trustee of New South Wales [2008] NSWCA 223; (2008) 1 ASTLR 56 at [101], Basten JA said:

Decisions with respect to discretionary powers may fall into various categories. One category involves a determination of where, within a range, the result properly lies. In such a case, as with the exercise of the sentencing discretion, the principles in House v R may properly be applied. Examples in the civil jurisdiction include the assessment of damages in personal injury cases and the valuation of property.

47 The High Court’s statement in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 504-505 is that:

The manner in which an appeal against an exercise of discretion should be determined is governed by established principles. It is not enough that the appellate court consider that, if they had been in the position of the primary judge, they would have taken a different course. It must appear that some error has been made in exercising the discretion. If the judge acts upon a wrong principle, if he allows extraneous or irrelevant matters to guide or affect him, if he mistakes the facts, if he does not take into account some material consideration, then his determination should be reviewed and the appellate court may exercise its own discretion in substitution for his if it has the materials for doing so. It may not appear how the primary judge has reached the result embodied in his order, but, if upon the facts it is unreasonable or plainly unjust, the appellate court may infer that in some way there has been a failure properly to exercise the discretion which the law reposes in the court of first instance. In such a case although the nature of the error may not be discoverable, the exercise of the discretion is reviewed on the ground that a substantial wrong has in fact occurred.

48 In Park Trent Properties Group Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2016] NSWCA 298, Leeming JA, with whom McColl and Gleeson JJA agreed, said:

[51] Two things of present importance emerge from the reasons of Gummow ACJ, Kirby, Hayne and Heydon JJ in Macedonian Orthodox Community Church St Petka Inc v His Eminence Petar (2008) 237 CLR 66; [2008] HCA 42. The first is the proposition accepted at [120] that:

when a court is invited to make a discretionary decision, to which many factors may be relevant, it is incumbent on parties who contend on appeal that attention was not given to particular matters to demonstrate that the primary judge’s attention was drawn to those matters, at least unless they are fundamental and obvious.

[52] The second is the explanation of the nature of the “orthodox approach to appellate intervention in relation to discretionary decisions” described at [137]–[138]. There it was pointed out that the expression “balancing exercise” is one to be employed with care, and that where (as in the present case) no statute mandates that particular weight be given to any one factor:

[T]he question of what weight the relevant factors should be given or what balance should be struck among them is for the person on whom the discretion is conferred, provided no error of law is made, no error of fact is made, all material considerations are taken into account and no irrelevant considerations are taken into account, subject to the possibility of appellate intervention if there is a plain injustice suggesting the existence of one of the four errors just described even though its nature may not be discoverable, or if there is present what has come to be known as ‘Wednesbury unreasonableness’.

[53] The same passage confirms that it is wrong to apply the words from House v R in isolation, as if they were not qualified by an absence of reasons explaining how the decision was reached. Park Trent’s selective statement of the principle upon which it relied has a tendency to dilute the test. The entire relevant passage from House v King, which was restated in the passage from Macedonian Orthodox Community Church St [P]etka Inc v His Eminence Petar, was as follows:

It may not appear how the primary judge has reached the result embodied in his order, but, if upon the facts it is unreasonable or plainly unjust, the appellate court may infer that in some way there has been a failure properly to exercise the discretion which the law reposes in the court of first instance. In such a case, although the nature of the error may not be discoverable, the exercise of the discretion is reviewed on the ground that a substantial wrong has in fact occurred.

Of course, that is not the present case, where the reasons of the primary judge are elaborate.

49 This is not to say that elaborate reasons are immune from appellate review. In the absence of specific error, the outcome reached either will or will not be one which was reasonably open. If not reasonably open, elaborate reasons will not protect the result from appellate intervention.

50 Accordingly, error is not involved merely because an appeal court would have reached a different conclusion.

51 Error may be specific, in the sense of apparent on the face of the reasons given, such as by application of a wrong principle in reaching the result (which may be evident by the primary judge addressing the wrong question), reaching the result by taking into account something that should not have been considered or by failing to take into account something that should have been considered, or by making a determinative error on the facts in the sense that the factual finding was not properly available to be taken into account in a way that affected the outcome.

52 Alternatively, error may be inferred from a result that cannot have been arrived at without some kind of operative error. The influence of the reasons given for the result arrived at on this process will vary. Reasons are not to be ignored, but nor do they necessarily confine in a rigid or inflexible way the scope of the appellate inquiry. It may be legitimate to have regard to what was said and not said in order to identify how the asserted erroneous result was reached. But for error to be inferred from the result, the result must be one which was not open on the evidence or facts found or agreed.

53 In all cases of specific error, the error must have either caused or materially contributed to the result. An error which has not in some material way affected the outcome will ordinarily result in the appeal court declining to intervene, at least as to the result.

54 In this case, the ACCC advances eight grounds of appeal. The first seven grounds may be seen as within the first category of asserted specific error. Thus for each or any of those grounds to succeed in relation to the appeal, the ACCC must not only establish the asserted error, but also that the error was material to the penalty imposed. Any errors in reasoning or approach falling short of this are insufficient for such grounds to succeed.

55 The ACCC’s eighth ground, asserted manifest inadequacy, is ordinarily asserted as an error of the second kind described in House v The King: inferred error. As Gleeson CJ and Hayne J observed in Dinsdale v The Queen [2000] HCA 54; (2000) 202 CLR 321 at [6]:

Manifest inadequacy of sentence, like manifest excess, is a conclusion. A sentence is, or is not, unreasonable or plainly unjust; inadequacy or excess is, or is not, plainly apparent. It is a conclusion which does not depend upon attribution of identified specific error in the reasoning of the sentencing judge and which frequently does not admit of amplification except by stating the respect in which the sentence is inadequate or excessive. It may be inadequate or excessive because the wrong type of sentence has been imposed (for example, custodial rather than non-custodial) or because the sentence imposed is manifestly too long or too short. But to identify the type of error amounts to no more than a statement of the conclusion that has been reached. It is not a statement of reasons for arriving at the conclusion. A court of criminal appeal is not obliged to employ any particular verbal formula so long as the substance of its conclusions and its reasons is made plain. The degree of elaboration that is appropriate or possible will vary from case to case.

56 A finding of manifest inadequacy (or excess) can be supported by reference to specific errors. In that event, even if the asserted specific error is not established as a separate basis upon which the appeal must be allowed, it may nonetheless help to explain the overall result said to be erroneous. While Dinsdale makes it clear that the appeal court does not have to attribute identified specific error in the reasoning of the sentencing judge, it is not precluded from doing so. This is especially so if a combination of such reasoning is asserted to produce or contribute to a manifestly inadequate (or excessive) result. It follows that the conclusion reached by this Court about grounds 1 to 7 may properly inform and support the conclusion properly to be reached about ground 8, whether or not our conclusions about any one of grounds 1 to 7 are themselves sufficient to require the primary judge’s order as to penalty to be set aside.

The purpose of a civil penalty

57 The appeal grounds, in particular ground 8 which asserts manifest inadequacy of the penalty, are informed by the purpose of civil penalty provisions. It is sufficient to refer to the CFMEU civil penalty case. French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ explained that:

[55] …whereas criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation, the purpose of a civil penalty, as French J explained in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [(1991) ATPR 41–076 at 52,152], is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance:

Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Trade Practices Act]. … The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

58 The primary judge recognised this purpose in the penalty judgment as follows:

39 It is well established that considerations of specific and general deterrence are vital in the assessment of pecuniary penalties. In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249, 265 [62]-[63], the Full Court of the Federal Court said that:

There may be room for debate as to the proper place of deterrence in the punishment of some kinds of offences, such as crimes of passion; but in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business… those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.

40 These comments were reiterated with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640, 659 [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

Appeal grounds 1 and 2: loss to consumers and causation

59 Grounds 1 and 2 challenge the approach of the primary judge on the issue of loss to consumers in different ways. They may be summarised as follows.

60 Ground 1 asserts that his Honour erred in concluding that any attempt to quantify profits caused by Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct and losses suffered by consumers as a result of that conduct would be impossible, so speculative as to be useless, of no assistance and neither necessary nor appropriate (penalty judgment [5], [53] and [66]), and thereby failed to take into account or give adequate weight to the statutory mandatory consideration of losses suffered by consumers in s 224(2)(a) of the ACL.

61 Ground 2 asserts that in considering the losses suffered by consumers, the primary judge should have found not only that that the products were the same, but also that the products were relevantly the same as standard Nurofen, the only difference between them (apart from the specific pain range costing about twice as much as standard Nurofen) being the conduct liable to mislead the public; that is, that the products were specifically formulated to treat, and in fact solely or specifically treated, the particular type of pain specified on the packaging relevant to each product when they were not and did not. Accordingly, this ground asserts that his Honour should have concluded that the contravening conduct was a material (and the primary) contributing cause of consumers choosing to purchase the more expensive products instead of the standard product, with the consequence that a reasonable estimate of the loss suffered was an amount of about half of the retail sales revenue during the contravening period (the sum calculated by the ACCC being some $26.25 million).

62 In the penalty judgment at [51]-[66], the primary judge was critical of the approach taken by Reckitt Benckiser (that it had not profited at all from the contravening conduct) and, to a lesser extent, the ACCC’s response of attempting to demonstrate the existence, and calculate the extent, of profit. In relation to the ACCC, his Honour noted that a substantial part of the evidence and submissions on sales, profit and potential losses to consumers and competitors focused upon an “elaborate exercise, based on volumes of evidence” directed to estimating the profit made as a result of the contravening conduct. This produced a result of some millions of dollars, but less than $10 million (penalty judgment at [51]). His Honour described the ACCC as carrying out “a labour of Hercules”, impossible to carry out in the absence of expert evidence and even then at best an “extremely rough approximation” and at worst an “informed guess”. His Honour accepted a submission by Reckitt Benckiser that any attempt to quantify profits caused by its contravening conduct would be either an impossible task or so speculative as to be useless, one reason being that it involved proof of a counterfactual, it being insufficient merely to show that the contraventions contributed to the profit made. His Honour rejected Reckitt Benckiser’s submission that it should be found it had not made any profit from the contravening conduct.

63 We agree with the primary judge that the ACCC’s approach, over-complicated though it might have been, rebutted Reckitt Benckiser’s proposition that it had derived no financial benefit from the contravening conduct (penalty judgment at [53]). Notably, Reckitt Benckiser continued to propound this proposition in this appeal on the basis that if by reason of error by the primary judge this Court had to determine penalty, it should do so on the basis that Reckitt Benckiser had derived no financial benefit from the contravening conduct. As discussed below, we reject this proposition.

64 An important part of the ACCC’s challenge to the reasoning of the primary judge concerned his Honour’s finding (at [60] of the penalty judgment), built on the counterfactual approach which his Honour considered was required, that “there may be consumers who were prepared to pay a substantial price premium for the products compared, for example, to standard Nurofen, for reasons such as ease of selection for the relevant condition, product placement, advertising and the like”. In this regard, and by way of example, the packaging of the products was brightly coloured and Reckitt Benckiser’s marketing provided for the products to be grouped together in prominent and easily accessible locations. We infer that these are the kinds of considerations the primary judge had in mind at [60] of the penalty judgment.

65 The primary judge, at [66] of the penalty judgment, considered it was sufficient to refer to the recommended retail prices in evidence before his Honour and the volume of sales over the five year period. This enabled total revenue from the sale of the products for the period 2011 to 2015 (the relevant contravening period, although the products were all sold from 2007 onwards) to be determined as $45 million. His Honour did not take the additional step of subtracting from that figure what the revenue would have been if the same sales had taken place of standard Nurofen. Nor was his Honour invited to do so by the ACCC. That additional step was only taken by the ACCC in further developing ground 2 of this appeal in its reply submissions. Calculations based on this approach produced a figure of aggregate additional sums paid by consumers over the five years of $26.25 million. Reckitt Benckiser did not dispute the accuracy of the calculations. This calculation also accords with the undisputed fact of the impugned products being sold for just over double the price of the standard product.

66 Reckitt Benckiser maintained that the approach advocated by the ACCC on appeal was not open, and there was no error by the primary judge. Reckitt Benckiser made the following three points in support of its position.

67 First, in respect of alleged error by the primary judge, his Honour did not fail to consider consumer loss. Rather, his Honour set out reasons, commencing at [51], why the evidence did not permit him to make any findings about the extent to which consumers had been induced by Reckitt Benckiser’s conduct to purchase any of the four products. So much is apparent, Reckitt Benckiser submitted, from the heading before [51] of the penalty judgment which is “Sales and profit from contravening conduct, and potential losses to consumers and competitors” (our emphasis), as well as the primary judge’s statement at [66] that:

For these reasons it is neither necessary, nor appropriate, in this case to attempt to engage in an exercise of attempting to quantify any amounts of (i) profit to Reckitt Benckiser from the contravening conduct, (ii) loss to consumers, or (iii) loss to competitors (our emphasis).

68 Second, the underlying premise of the calculation is incorrect. It cannot be assumed that the products are the same as standard Nurofen. This was not part of the contravening conduct found. The products contain 342mg of ibuprofen lysine which is equivalent to 200 mg of ibuprofen. Standard Nurofen contains 200mg of ibuprofen. Nurofen Zavance contains 256mg of sodium ibuprofen dehydrate which is equivalent to 200mg of ibuprofen but is absorbed twice as fast as standard Nurofen. Accordingly, it cannot be assumed that the products are the same as standard Nurofen or other products (for example, of competitors) containing 200mg of ibuprofen which cost less than the purported specific pain range products. This point was related to another submission by Reckitt Benckiser which the primary judge appears to have accepted at [61] of the penalty judgment that:

… it was not alleged and has not been found that any representation was made that, based on the packaging and higher pricing, the Nurofen Specific Pain Range products are more effective than other Nurofen pain relief products.

69 Third, the primary judge was correct at [60] that the counterfactual approach depended on excluding consumer choices based on factors other than the contravening conduct such as “ease of selection for the relevant condition, product placement, advertising, and so on”. His Honour was also correct at [60] and [61] to accept Reckitt Benckiser’s submission that minor changes to the packaging removed the misleading representations with the consequent conclusion that the contraventions may well have yielded little profit to Reckitt Benckiser.

70 We should reiterate that the ACCC’s case before the primary judge focused on Reckitt Benckiser’s alleged profit as a result of the contravening conduct and his Honour was not invited to quantify consumer loss in the manner which the ACCC has now identified. The ACCC nevertheless maintained before his Honour that consumers had suffered loss as a result of the contravening conduct and his Honour concluded that the extent of such loss could and should not be assessed (at [66]). For the reasons given below, we consider that the primary judge’s approach to consumer loss was in error and, despite the ACCC’s focus on profits before his Honour, the error was material to the outcome.

71 It may be accepted that the contravening conduct involved the purported specific pain range, not standard Nurofen or any competitor product containing the equivalent active ingredient (ibuprofen) and dose (200mg). It may also be accepted that the contravening conduct did not involve a misrepresentation that any of the purported specific pain range products was more effective in treating pain than another product. However, these matters do not lead to the outcomes for which Reckitt Benckiser contended.

72 The task under s 224(2)(a) is to have regard to the nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the loss or damage suffered as a result. If the assessment of the loss involves facts other than those comprising the contravening conduct, those facts must be considered. In the present case, the agreed facts and other evidence disclosed that ibuprofen lysine is the chemical equivalent of ibuprofen, the purported specific pain range products contained 342mg of ibuprofen lysine which is the equivalent of 200mg ibuprofen, the active ingredient of standard Nurofen is 200mg ibuprofen, and the purported specific pain range products cost about twice as much as standard Nurofen.

73 In particular, the agreed facts included these paragraphs:

7. The active ingredient of all Nurofen products is ibuprofen or chemical equivalents of ibuprofen (for example, ibuprofen lysine and sodium ibuprofen dehydrate).

8. Ibuprofen is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that acts to inhibit pain causing chemicals (prostaglandins) responsible for tissue pain and inflammation. Inhibition of prostaglandin occurs at both peripheral sites in the body and in the central nervous system. Pain originates when locally-elevated concentrations of these prostaglandins sensitise the nerve endings found in tissue and trigger pain signals to the central nervous system. By blocking the production of prostaglandins, ibuprofen inhibits the sensitisation of nerve endings and prevents the transmission of signals.

74 As noted, the evidence included the packaging of the products in the purported specific pain range which contains the statement “equiv. ibuprofen 200mg”. The evidence also included the standard Nurofen packaging which identifies the only active ingredient of that product as ibuprofen 200mg. Reckitt Benckiser submitted that chemical equivalence did not mean that the active ingredients were the same. Literally, this must be true. But what is relevant for present purposes is that, at least insofar as the purported specific pain range products and standard Nurofen are concerned, the agreed facts and packaging demand the inference that they are relevantly the same, in that all of the products provide in the body a dose equivalent to 200mg of ibuprofen .

75 Contrary to Reckitt Benckiser’s submissions, the different chemical formulation of Zavance does not suggest any relevant difference between the purported specific pain range products and standard Nurofen. There is no evidence about how Zavance is absorbed more quickly than standard Nurofen but it is apparent the chemical formulation of the equivalent active ingredient is different from both standard Nurofen and the purported specific pain range products. Moreover, unlike Zavance, there is no suggestion on the packaging of the purported specific pain range products that they are anything other than equivalent to 200mg of ibuprofen or have any qualities (such as a faster rate of absorption) different from standard Nurofen. In any event, in the face of the agreed fact of chemical equivalence between the purported specific pain range and 200mg of ibuprofen, it was a matter for Reckitt Benckiser to call evidence to establish any proposition to the contrary. It did not.

76 The fundamental difficulty we have with the primary judge’s conclusion about the impossibility of assessing the extent of consumer loss is that it involved an implicit acceptance of the conceptual framework established by Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct. In short, how can it be concluded that consumers might have been willing to pay a price premium for the purported specific pain range products “for reasons such as ease of selection for the relevant condition, product placement, advertising, and so on” without implicitly accepting that the products were different from each other (when they were not, the foundation of the contravening conduct) and relevantly different from standard Nurofen (when they were not, the foundation of any assessment of consumer loss)? There was, in truth, no “selection” involved. There was no “relevant condition” involved. The concepts of “selection” and “relevant condition” are constructs created by the contravening conduct. There was no difference between the products and thus, absent the contravening conduct, no rational reason for the different marketing to which his Honour referred. The marketing differences in the present case were part and parcel of the misleading character of the conduct.

77 Reckitt Benckiser submitted that the absence of any representation that the purported specific pain range products were more effective than any other ibuprofen product meant that there was no rational reason for a consumer to purchase the purported specific pain range products rather than any other product. We disagree. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [55] French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ said:

It has long been recognised that, where a representation is made in terms apt to create a particular mental impression in the representee, and is intended to do so, it may properly be inferred that it has had that effect. Such an inference may be drawn more readily where the business of the representor is to make such representations and where the representor’s business benefits from creating such an impression.

78 The contravening conduct was apt to create in a consumer the impression that the purported specific pain range product had been formulated to and did in fact treat the specific pain type nominated. It must be inferred that Reckitt Benckiser engaged in the contravening conduct for its commercial benefit, encouraging consumers suffering from the nominated pain types to purchase one or more of the purported specific pain range products rather than a cheaper equivalent product. As such, why should it not be inferred that a consumer acted in accordance with the impression the contravening conduct was apt to create in a consumer’s mind? Contrary to Reckitt Benckiser’s submission, if suffering from back pain, it is rational for consumers to purchase a product that purports to treat back pain, without even turning their mind to concepts such as equivalent effectiveness.

79 For these reasons we do not accept another submission of Reckitt Benckiser that the primary judge’s orders with respect to liability mean that the products are liable to mislead the public only if considered as part of the purported specific pain range, and not if considered in isolation from one another. We do not consider that the ACCC’s case or his Honour’s findings and orders were confined in this way. It is apparent from the ACCC’s fast track statement that the contentions relate to each product within the so-called Nurofen Specific Pain Range. It was alleged that each product in that range contravened, relevantly, s 33 because of the “Packaging Statements” which were defined as statements made on each product. The primary judge’s orders also referred to each product in the so-called “Nurofen Specific Pain Range”. The words “in combination” or any like formulation do not appear. This said, it is true and apparently not disputed that the combined effect of the four types of packaging enhanced, and to that extent aggravated, their liability to mislead.

80 Test Reckitt Benckiser’s submission this way. Assume the only product on the market was the Nurofen migraine pain product. The packaging of that product included the following:

MIGRAINE PAIN

NUROFEN

MIGRAINE PAIN

FAST TARGETED RELIEF FROM PAIN

81 The primary judge’s orders included that Reckitt Benckiser, in carrying out the conduct of marketing and selling the so-called Nurofen Specific Pain Range, had represented that each product in that range was specifically formulated and solely or specifically treated the particular type of pain relevant to that product when it was not. Can it be maintained, as Reckitt Benckiser would have it, that if (contrary to the fact) only one product had been sold, the packaging of that product would not have represented that it was specifically formulated and solely or specifically treated the particular type of pain relevant to that product when it was not? The only possible answer to this question is “no”. Nor does anything in the liability judgment suggest this to be so. To the contrary, at [36] his Honour said this, which confirms the conclusion we have reached:

…the Packaging Representations which were admitted, and which I found had been made, concerned each product in the Nurofen Specific Pain Range. Nurofen’s representations were relied upon by the ACCC, and found by me to be contraventions, not merely for their character as representations on each of the four products but for their character as representations over the range of four products.

82 Accordingly, the fact that Reckitt Benckiser marketed four products which were all liable to mislead the public in the same way, and the ACCC’s fast track statement and primary judge’s orders reflect this fact, do not mean what Reckitt Benckiser apparently (and, it must be said, disturbingly) still maintains that there was nothing wrong with the packaging of each product considered in isolation.

83 Contrary to Reckitt Benckiser’s submission, these conclusions do not involve any expansion of the contravening conduct. The penalty is to be determined for the contravening conduct but the facts relevant to penalty (if agreed or proved) are not confined to the contravening conduct. Nor does this involve an assumption that, but for the contravening conduct, the products would not have existed at all. It does involve, however, acceptance of the proposition that one consequence of the contravening conduct was the illusion that the products involved a range specifically targeted to certain pain types when, in fact, they did not. This proposition, in our view, is a necessary consequence of the contravening conduct. And a necessary consequence of this proposition for the assessment of consumer loss is that consumers would have been induced to buy the products purporting to be specifically formulated to treat the type of pain from which they were suffering in preference to a product, such as standard Nurofen, which did not purport to be so specifically formulated.

84 For these reasons it is impossible to see how any features such as ease of product selection for the relevant condition, product placement, advertising and the like may be extracted for separate consideration from the misleading nature of the packaging representations, let alone be given any real weight. Each was part and parcel, or the result, of the contravening conduct. But for the contraventions, there was no range to inform the branding, advertising or placement of the products. The very notion of product selection is at the heart of the misleading character of the conduct and itself an illusion because all of the products, including standard Nurofen, were relevantly the same. The four products liable to mislead were identical.

85 Apart from the considerations which Reckitt Benckiser put forward and the primary judge accepted being tainted by the contravening conduct, any part they might have had to play in any purchase decision by a consumer, at best, was speculative. There was no material difference between the products and standard Nurofen. The obvious and expected consequence of the contravening conduct was to entice consumers to pay more for the products. Without compelling evidence to the contrary, there was no rational reason to speculate in favour of Reckitt Benckiser that consumers might have been willing to pay twice as much for the same product but for the contravening conduct. The same conclusion applies to the possibility that some consumers may not have cared about price. This is mere speculation by Reckitt Benckiser. The obvious, compelling inference, absent evidence to the contrary, was that the contravening conduct and its consequences for the branding and marketing of the products were the material reason that consumers – or at least the vast majority of consumers – purchased those products rather than standard Nurofen. Reckitt Benckiser’s contrary approach, largely accepted by the primary judge, assumes the existence of the range and of difference between the products, when this is the essence of the misleading character of Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct.

86 We also do not consider that concepts such as elasticity of demand or cross-elasticity, which concerned the primary judge at [57]-[58] of the penalty judgment, were necessary components of the analysis in the circumstances of this case. The ACCC’s approach, as his Honour noted at [57], assumed in favour of Reckitt Benckiser that every person who purchased one of the purported specific pain range would otherwise have purchased another form of Nurofen. His Honour was concerned, however, that there were 50 different types of Nurofen so it was mere speculation to conclude that any person would have purchased any particular type. We disagree. The evidence was that these 50 types of Nurofen included different dosages, dosage forms, and different combinations of active ingredients. Within those types, it is the purported specific pain range and standard Nurofen (as well as Zavance, which is differentiated by apparent speed of absorption) which involved a dosage equivalent to 200mg of ibuprofen (for standard Nurofen whether it be in tablet, caplet or capsule form).

87 Again, absent compelling evidence to the contrary, the obvious and compelling inference, and also the inference most advantageous to Reckitt Benckiser, was that if not enticed to purchase the purported specific pain range product by reason of the contravening conduct, in the ordinary course a person would have purchased one of the standard Nurofen products. In the particular (and unusual) circumstances of this case, where the contravening conduct created the illusion of a range and thus a choice which did not exist, expert evidence about cross-elasticity in the market was unnecessary.

88 Nor do we accept that the lack of any representation that the products were more effective than any other Nurofen product was material to the assessment of consumer loss. The essence of Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct as pleaded is not found in concepts of efficacy, but of different products for the purposes of different pain types when the products were the same and were, in terms of action within the body, indifferent to pain type or location. For these reasons Reckitt Benckiser’s submission, that no person could have purchased one of the specific pain range products believing the product to be more effective than standard Nurofen, is immaterial.

89 Insofar as Reckitt Benckiser relied upon the submission that minor changes to the packaging would mean that the packaging was no longer liable to mislead the public in contravention of s 33 of the ACL, which the primary judge accepted at [60]-[61], two additional problems arise.

90 First, at [60] his Honour referred to a “concrete example” which, he said, “illustrates the significance of this point to the impossibility of calculating profit from contraventions”. The example was Reckitt Benckiser’s new packaging (achieved by affixing a sticker on the products) which it had agreed as an interim arrangement with the ACCC after the liability judgment on 11 December 2015 and which enabled the existing stock to continue to be sold. However, the packaging which his Honour described was not the new packaging to which the ACCC agreed as an interim measure. It was the packaging which Reckitt Benckiser had put to the ACCC during the course of the investigation as a possible solution, but which the ACCC had rejected. It must be inferred that the ACCC rejected the proposal on the basis that it considered that the packaging continued to be misleading and deceptive or likely to mislead and deceive, or at least liable to mislead.

91 Contrary to Reckitt Benckiser’s submission, and for reasons set out more fully in respect of ground 3 below, this mistake was material. The terms of [60] and [61] of the penalty judgment confirm that the primary judge considered the new packaging to be important is plain. But there are material differences between the packaging proposal the ACCC rejected and the new packaging which it accepted as an interim measure. The latter did not bear a sticker at the top saying “suitable for general pain relief”. It bore a sticker beneath the nominated pain type, in equally prominent type, saying “equally effective for [all of the other nominated pain types] and general pain”. The differences between the agreed interim packaging and the contravening packaging are not minor.

92 Second, there was no evidence about the effect of the agreed interim packaging on consumer behaviour. It is not apparent why it would be inferred in favour of Reckitt Benckiser that the changed packaging had no effect on consumer behaviour when the change went to the heart of the branding of the purported specific pain range – that the products within the purported range were all the same and they were equally effective for all kinds of pain.

93 Accordingly, and contrary to the submissions made on behalf of Reckitt Benckiser, the mandatory consideration of consumer loss did not require precise causation or mathematical precision. It never required evidence from consumers on a “but for” basis or expert evidence. The primary judge was constrained by what was before him, but was required to do the best that he could with what was available, applying the orthodox “common sense” approach to causation of consumer loss which “requires no more than that the act or event in question should have materially contributed to the loss or injury suffered” (Henville v Walker [2001] HCA 52; (2001) 206 CLR 459 at [61] per Gaudron J citing Wardley Australia Ltd v Western Australia (1992) 175 CLR 514 at 525).

94 Considered other than through the distorting prism created by Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct, the only reasonable inference available on the evidence was that a substantial number of the sales of the purported specific pain range products was caused by the contravening conduct but for which, at best for Reckitt Benckiser, consumers would have purchased a standard Nurofen product at half the price.

95 If not for the matters discussed above, in particular the implicit adoption of the concept of the products being formulated for and treating different pain types when they did not, it is unlikely that the primary judge would have concluded that the extent of the loss to consumers was beyond meaningful assessment.

96 Our final observation is that there is perhaps an easier way of looking at the problem of loss. With the benefit or advantage of conduct liable to mislead the public, namely by way of marketing representations that were deliberately made (putting to one side the issue of state of mind), 5.9 million packets of the purported Nurofen specific pain range were sold. As we have said, those representations were the only apparent reason for any rational consumer to buy the products at twice the price of standard Nurofen. The ordinary and predictable consequence of the conduct is not a circumstance of aggravation which the ACCC had to prove. Rather, if Reckitt Benckiser wished to have the Court accept that any of those 5.9 million sales were not substantially, if not overwhelmingly, influenced by the contravening conduct in a material way, the argument is one in mitigation which Reckitt Benckiser had to prove. There was no such evidence.

97 The primary judge started down the relevant path when he observed at [55] of the penalty judgment that Reckitt Benckiser engaged in its marketing and packaging of the purported specific pain range products, “with the intention of increasing profits”. Thereafter, his Honour’s acceptance of Reckitt Benckiser’s submissions also involved both an implicit acceptance of the concepts which gave rise to the contraventions and speculation about consumers’ behaviour. As a result, the primary judge was diverted from the drawing of obvious inferences which the evidence made compelling in the circumstances.

98 For these reasons, we consider that the primary judge erred on the question of loss to consumers. In our view, there was ample evidence to infer a direct causal relationship for sales of the more expensive four identical products. In the circumstances, that inference had to be drawn. No other reasonable inference could be drawn in the absence of evidence to rebut it. There was no reason not to draw that inference. In particular, there was no credible alternative explanation for the sales, or at least the vast bulk of them, taking place. Accordingly, a finding ought to have been made that a substantial proportion of the difference between the sales price of 5.9 million packages of the impugned products and of the equivalent number of sales of standard Nurofen had been lost to consumers as a result of Reckitt Benckiser’s contraventions of s 33 of the ACL between 2011 and 2015. Whether that be $26.25 million (as the ACCC has now calculated) or another amount (based on some refinement of the calculations), the loss was in the order of 50% of the total revenue from the sale of the impugned products, being $45 million.

Appeal ground 3: error in relation to replacement packaging

99 Ground 3 concerns the primary judge’s mistake in respect of the new packaging. As noted, his Honour mistakenly identified a packaging proposal rejected by the ACCC as the new packaging which involved “minor changes” and in respect of which the ACCC was said to have made no allegation that the new packaging was misleading (at [60] and [61] respectively; see also [4] and [5]). As also noted, Reckitt Benckiser accepted that the primary judge had identified the wrong packaging but argued that there was no material difference between the rejected proposed packaging and the interim packaging, nor any material consequence as a result of the mistake.

100 We do not accept Reckitt Benckiser’s submission for the following reasons.

101 Both before the primary judge and on appeal, Reckitt Benckiser contended that there was a very small difference in the packaging representations the subject of these proceedings, the alternative packaging initially proposed by Reckitt Benckiser but rejected by the ACCC, and the alternative packaging ultimately accepted by the ACCC as an interim measure by way of the addition of stickers so that existing stock would not be wasted. The essential differences were as follows, taking the so-called Nurofen “back pain” product as an example:

(1) The packaging representations giving rise to these proceedings:

(2) The mock-up packaging representations proposed by Reckitt Benckiser but rejected by the ACCC:

(3) The temporary packaging created by ACCC-approved stickers placed on existing stock:

102 Confined to the terms of s 33 of the ACL, the manner in which the contravening packaging was liable to mislead the public is manifest. The product is not specifically formulated for – and does not treat – any specific pain, be it back pain or otherwise. Accordingly, it is not “targeted” pain relief in the sense of being targeted to the type of pain nominated on the packaging.

103 The ACCC’s rejection of the proposed packaging secondly represented above is understandable. The added words (not prominent on the packaging as proposed) continue to represent that the product is formulated for and treats back pain, but also happens to be suitable for general pain relief. The proposal fell well short of ameliorating the misleading and deceptive character of the packaging.

104 The interim solution accepted by the ACCC, at the least, is better than the first two. The sticker is in type which has equivalent prominence to the words “back pain”. The sticker includes the important words “Equally effective for” followed by each of the nominated pain types on the purported specific pain range and the words “and general pain”. We do not accept that this was only a minor change from either the impugned packaging or the proposed replacement packaging rejected by the ACCC.

105 Before the primary judge, the ACCC did not suggest that the interim packaging to which it had agreed contravened the ACL. It follows that it cannot be said that the primary judge erred at [61] when he proceeded on the assumed (rather than proven) basis that the new interim packaging did not involve any contravention. The error, as we have said, was in mistakenly identifying the proposed but rejected packaging as the new interim packaging. The ACCC maintained its position in the appeal of refraining from any suggestion that the (actual) new interim packaging was liable to mislead the public. Given that the issue was not argued, it is not appropriate to venture into this area.

106 The primary judge’s mistake as to the relevant packaging was material to his conclusion that consumers might have been willing to pay a substantial price premium for the purported specific pain range products for reasons other than the contravening conduct. In turn, this conclusion was material to his Honour’s conclusion that it was neither necessary nor appropriate nor possible to attempt to engage in any exercise of, relevantly, assessing loss to consumers.

107 The fact that, in other cases, judges have reached the same conclusion on the evidence before them is immaterial. It may be accepted that in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540, Allsop CJ said at [54] that the “nature of the conduct involved in this case means that precise or even global assessment of any loss to consumers or competitors is difficult, if not impossible”. This was the ACCC’s position before Allsop CJ (see at [26]). And as Allsop CJ also said in Coles, referring to Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 382; (2011) 279 ALR 609 at [77]–[79]:

[56] MSY Technology was a case where retailers were selling various computer-related goods and making representations which fell into three categories (at [57]):

… The first category consists of statements in which the respondents purported to disclaim or exclude their responsibility for providing warranties to consumers. The second consists of statements which purported to restrict the responsibility of the respondents for providing warranties to consumers in various ways. The third consists of statements suggesting that consumers were required to pay a fee for warranties beyond those provided by the manufacturer.

[57] The “commonsense” nature of his Honour’s suggestion is, with respect, far more apposite to a case such as the one before his Honour than it is in the present. It would be simple enough to adduce evidence of consumers who paid for additional warranties or who incurred expenses in the belief that they were not entitled to a warranty. The circumstances of that case were such that the misleading or deceptive conduct could clearly have a quantifiable and ascertainable pecuniary consequence for consumers. Here, the ACCC did not contend that the quality of the par-baked products was of any lower standard than goods baked from scratch. The primary source of any loss or damage to consumers was of a non-pecuniary nature. The fact that they had lost the opportunity to make a different purchasing choice that they may have made had they been provided with accurate information about the goods they were purchasing. In light of the period of time over which the conduct took place, I am not prepared to sentence on the basis that no one was in fact misled by Coles’ conduct.

[58] There is an alternative source of loss or damage, and that is loss or damage to competitors. Pecuniary damage might be proved here, but a number of other factors (such as those referred to in the affidavit of Mr Watson) may well be to blame for the loss. Demonstrating a causal link beyond a merely temporal connection is nearly impossible in these circumstances. This is not a situation like MSY Technology. That case involved a conclusion based on the specific factual circumstances of the case. Care must be taken to not elevate conclusions based on factual considerations to the status of rules of law.

108 There is no suggestion in Coles that the contravening product was the same as another product but sold at a price premium. Had that been the case then it cannot be assumed that the ACCC’s position would have been that loss could not be quantified, nor that Allsop CJ would have reached that conclusion.

109 We also do not accept that, in the circumstances of this case, an assessment of the loss to consumers as a result of Reckitt Benckiser’s contravening conduct involved undue speculation. The number of units of the purported specific pain range products sold in the relevant period was known. The chemical equivalence of the purported specific pain range products and standard Nurofen (and other products providing 200mg of ibuprofen) was known. The price premium for the purported specific pain range products was known. The real speculation involved was that of Reckitt Benckiser contending that:

(1) Consumers might have purchased the more expensive products for reasons such as “ease of selection for the relevant condition, product placement and advertising” when there was no “relevant condition” and the only reason for any difference in product placement and advertising was the contravening conduct.

(2) Consumers might not have purchased standard Nurofen but one of the other 50 Nurofen products when the relevant context was the purchase of a product providing 200mg of ibuprofen and no other active ingredient.

In any event, as discussed, the speculation involved in (2) above favoured Reckitt Benckiser because, but for the contravening conduct, a consumer might have purchased a competitor’s equivalent product (which the evidence indicated was available at prices less than those of standard Nurofen) and not Nurofen at all.

110 These conclusions support our view that the primary judge’s approach to consumer loss involved material error, requiring this Court to determine for itself the appropriate penalty to be imposed for the contravening conduct.

Appeal ground 4: types of harm

111 Ground 4 is that the primary judge erred by giving undue weight to the consideration that the harm caused to consumers by the contravening conduct was not physical and was only monetary (penalty judgment [97]). As argued, however, the ground was that this conclusion was simply incorrect.

112 It is apparent that this matter was significant to the primary judge. At [94] his Honour said that:

In this case, if it were not for three particular matters, the penalty would be far greater than that which I now impose.

113 The third of these matters was his Honour’s conclusion that as the products were effective to treat the pain that they represented they treated, the only potential effect on consumers was monetary.