FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Global Gaming Supplies Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 22

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The orders and declarations made by the primary judge on 30 September 2013 be set aside and, in lieu thereof, make the orders and declarations set out in paragraphs 3-10 (inclusive) below.

3. Each of the respondents be restrained, whether by its or his servants, agents or otherwise, from infringing the 428 Mark or the 430 Mark by:

(a) in the course of any trade using the mark, or any other mark that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the mark, as a trade mark, in relation to any gaming machine containing unauthorised Aristocrat game software without the licence or consent of the first appellant; or

(b) procuring, authorising, or acting in concert with, any other person to engage in any such use of the mark without the licence or consent of the first appellant.

4. Each of the fourth and sixth respondents be restrained whether by its or his servants, agents or otherwise from infringing any of the Game Name Marks by:

(a) in the course of any trade applying the mark, or any other mark that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the mark, to any EPROM containing unauthorised Aristocrat game software without the licence or consent of the first appellant;

(b) procuring, authorising, or acting in concert with, any other person to engage in any such use of the mark without the licence or consent of the first appellant.

5. The fourth and sixth respondents be restrained whether by their servants, agents or otherwise from infringing the first appellant’s copyright by:

(a) reproducing, in a material form, without the licence or consent of the first appellant, the following works:

(i) any Aristocrat game software; or

(ii) the Design Specification 565875 (Revision B);

(b) procuring, authorising, or acting in concert with, any other person to engage in conduct referred to in sub-para (a) hereof.

1. Within 14 days each of the fourth and sixth respondents deliver up to the first appellant for destruction, the following:

(a) all EPROMs in its or his possession, custody or control, that contains a copy of any Aristocrat game software made without the licence or consent of the first appellant; and

(b) all compliance plates in its or his possession, custody or control that reproduce design specification 565875 (Revision B) made without the licence or consent of the first appellant.

2. Within 14 days each of the first, second, third and fifth respondents deliver up to the first appellant for destruction all EPROMs in its or his possession, custody or control that contains a copy of any Aristocrat game software made without the licence or consent of the first appellant to which any one or more of the Game Name Marks has been affixed.

THE COURT DECLARES:

1. Each of the first, second, third, fifth and sixth respondents has infringed the 428 mark and the 430 mark by, without the licence or consent of the first appellant, acting in concert to export for sale gaming machines which incorporated:

(a) unauthorised compliance plates that bore the word “Aristocrat”; and

(b) EPROMs containing unauthorised Aristocrat game software.

2. The sixth respondent has infringed each of the Game Name Marks by, without the licence or consent of the first appellant, applying them, in the course of trade, to EPROMs containing copies of unauthorised Aristocrat game software.

3. The sixth respondent has infringed the first appellant’s copyright by reproducing, in a material form, without the licence or consent of the first appellant, the following copyright works:

(a) Aristocrat game software known by the name “Queen of the Nile”, “Chicken”, “Cash Chameleon”, “Golden Pyramids”, “Flame of Olympus”, “Adonis”, “Jumping Joeys”, “King Galah”, “Reel Power”, “Superbucks II” and “Thor”; and

(b) the Design Specification 565875 (Revision B).

In these orders and declarations:

“428 mark” means Australian registered trade mark number 787428;

“430 mark” means Australian registered trade mark number 787430;

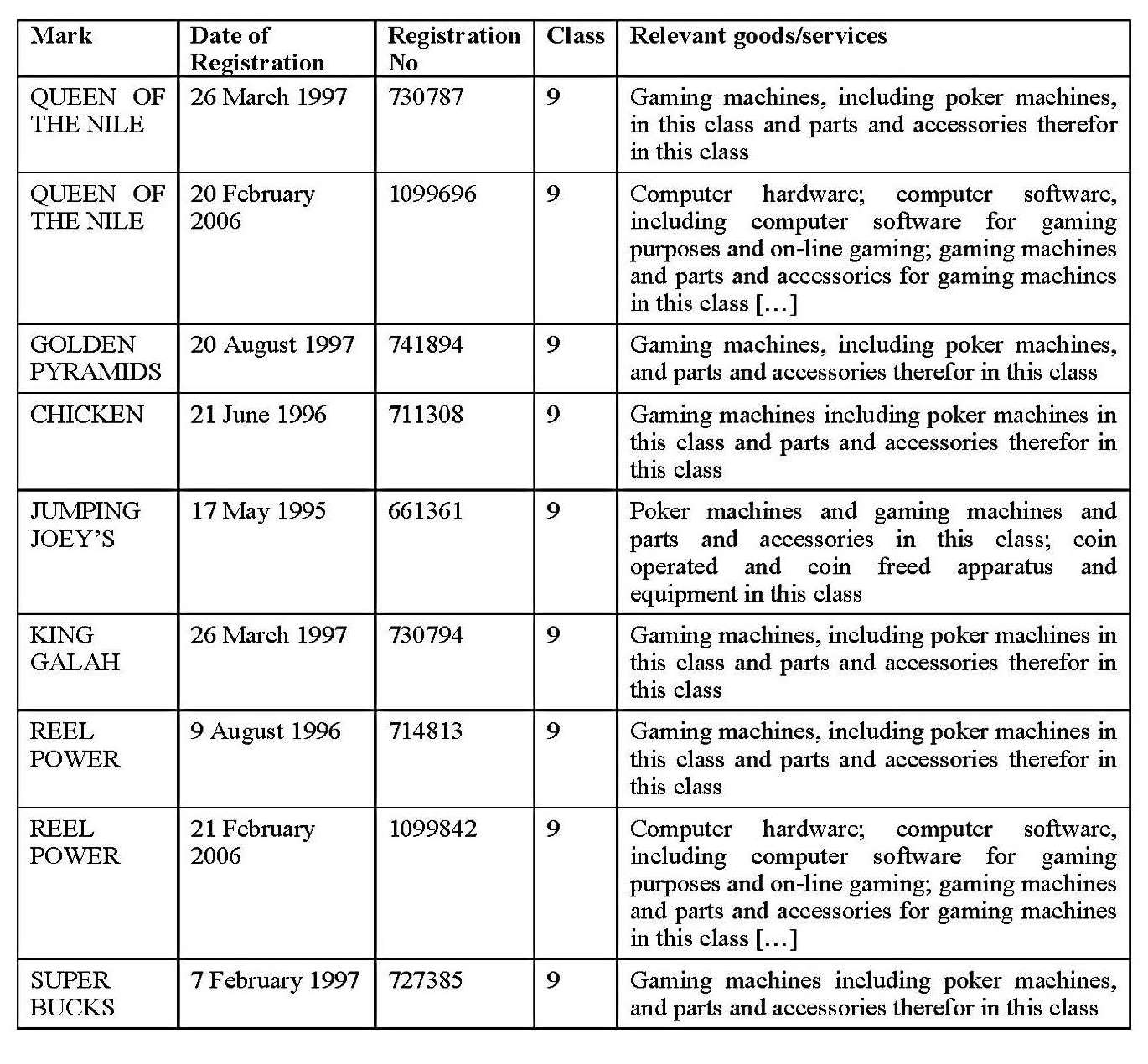

“Game Name marks” means Australian registered trade mark numbers 730787, 1099696, 741894, 711308, 661361, 730794, 714813, 1099842 and 727385;

“compliance plates” means any compliance plate identifying the first appellant as the manufacturer of the gaming machine to which it is affixed;

“unauthorised compliance plates” means any compliance plate that was made without the licence or consent of the first appellant;

“Aristocrat game software” means any of the computer programs known by the name “Queen of the Nile”, “Chicken”, “Cash Chameleon”, “Golden Pyramids”, “Flame of Olympus”, “Adonis”, “Jumping Joeys”, “King Galah”, “Reel Power”, “Superbucks II” and “Thor”;

“unauthorised Aristocrat game software” means any electronic copy of the whole or any substantial part of any Aristocrat game software that was made without the licence or consent of the first appellant and in breach of the first appellant’s copyright.

“EPROMs” means Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory chips or any other device that may be used to store electronic copies of computer programs.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties file and serve written submissions (limited to three pages in length) in relation to:

(a) the costs of the remittal hearing;

(b) the costs orders the subject of the appeal and cross-appeal; and

(c) the costs of the appeal and the cross-appeal.

by 4pm 11 March 2016;

2. The parties file any written submissions in reply (limited to two pages in length) by 4pm 18 March 2016.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 This is an appeal and a cross-appeal against orders made by the primary judge on 30 September 2013 and 25 November 2013 in relation to two questions remitted to his Honour by order of a Full Court (Bennett, Middleton and Yates JJ) on 25 May 2012.

2 The first question remitted to the primary judge was what declaratory or injunctive relief, if any, should be granted in relation to copyright infringement arising under s 36 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the Copyright Act”). His Honour made some declarations in relation to copyright infringement by the sixth respondent (Mr Allam) but declined to grant any injunctive relief. The appellants (which we shall refer to collectively as the “Aristocrat parties”) appeal against his Honour’s refusal to grant declaratory relief in a form justified by his Honour’s and the Full Court’s findings or any injunctive relief in respect of copyright infringement.

3 The second question remitted to his Honour related to a case of trade mark infringement brought by the Aristocrat parties against the respondents. The Aristocrat parties’ appeal against his Honour’s dismissal of that case. They also appeal against the primary judge’s order requiring them to pay the respondents’ costs of the remittal proceedings and the costs order made in favour of the fourth respondent (“Tonita”).

4 The respondents have filed various notices of contention and Mr Allam has filed a notice of cross-appeal in relation to the costs order made against him.

5 In these reasons it will be necessary for us to refer to the following judgments of the primary judge and the Full Court:

the first judgment of the primary judge: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Global Gaming Supplies Pty Ltd (2009) 84 IPR 222, [2009] FCA 1495 (Aristocrat 1);

the second judgment of the primary judge relating to (inter alia) final relief which is the subject of this appeal: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Global Gaming Supplies Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 277 (Aristocrat 2);

the first judgment of the Full Court on appeal from Aristocrat 1 and Aristocrat 2: Allam v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd (2012) 95 IPR 242, [2012] FCAFC 34 (Allam 1);

the second judgment of the Full Court on appeal from Aristocrat 1 and Aristocrat 2: Allam v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCAFC 75 (Allam 2);

the third judgment of the primary judge upon remittal which is the subject of this appeal: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Global Gaming Supplies Pty Ltd (2013) 102 IPR 400, [2013] FCA 986 (Aristocrat 3); and

the fourth judgment of the primary judge relating to costs which is the subject of the appeal and the cross-appeal: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Global Gaming Supplies Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 1253 (Aristocrat 4).

Factual Background

6 The Aristocrat parties are all members of the Aristocrat group of companies which are subsidiaries of Aristocrat Leisure Limited. The Aristocrat group of companies is engaged in the business of supplying gaming technologies and services to the international gaming industry. The first appellant, Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd (“ATA”) is engaged in the design, manufacture and supply of electronic gaming machines and computer software and is also the owner of the various registered trade marks and the copyright in the computer software and artwork used in Aristocrat gaming machines. When we refer in these reasons to Aristocrat gaming machines, we refer to gaming machines manufactured by ATA. We should point out that ATA was previously known as Aristocrat Leisure Industries Pty Limited.

7 ATA and the second appellant (“AI”) are parties to a written contract executed on 19 July 2006 which purports to confer on AI, with effect from 1 January 2005, an exclusive licence to intellectual property in respect of Aristocrat products worldwide, other than Australia, but including products made for export outside Australia. The third appellant (“ATI”) is a wholly owned subsidiary of AI based in Nevada, United States which is engaged in the supply of Aristocrat gaming machines in North and South America.

8 There are six respondents to the Aristocrat parties’ appeals. The first respondent (“Global”) and the third respondent (“Impact”) were found to have been participants in a joint venture (“the Joint Venture”) from 1 October 2004 supplying refurbished Aristocrat gaming machines to overseas markets including the South American market. The second respondent (Mr Andrews) is the sole director and shareholder of Global and the fifth respondent (Mr Cragen) is the sole director and shareholder of Impact. Impact was incorporated on 24 May 2004. We shall refer to Global, Mr Andrews, Impact and Mr Cragen collectively as the “Global/Impact respondents”.

9 The fourth respondent, Tonita, was incorporated on 14 July 2006. Mr Allam, the sixth respondent, is a director and shareholder of Tonita. We shall refer to Tonita and Mr Allam collectively as the “Tonita respondents”.

10 Mr Allam is a gaming machine technician who provided services to the Joint Venture. Mr Allam’s residence is situated at Georges Hall (“the Georges Hall premises”). His association with the Joint Venture dates back to about January 2004. Mr Allam continued to provide services to the Joint Venture through Tonita after that company’s incorporation. Tonita, and before that, Mr Allam, carried on business at Impact’s office and warehouse situated in Botany (“the Botany premises”).

11 Global’s main office is situated in the Australian Capital Territory (“the Florey premises”) and it also used an office at Mascot (“the Mascot premises”). However, the activities of the Joint Venture, including obtaining and storing supplies of second hand gaming machines, refurbishing such machines and packaging them for delivery, took place at the Botany premises. Mr Allam, or his company Tonita, employed an assistant (“Mr Channa”) who also worked at the Botany premises. Tonita also carried on business at a warehouse it leased in Bankstown (“the Bankstown premises”) which it used to store materials acquired from Behong Import & Export (Australia) Pty Ltd (“Behong”), a scrap merchant located in Sydney, which was one of ATA’s authorised scrap merchants.

12 Aristocrat gaming machines include a number of components. Relevantly, they include artwork panels fixed to the exterior of the machine and Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory chips (“EPROMs”) used to store the game software. Aristocrat gaming machines also include compliance plates. These are metal plates (“Aristocrat compliance plates”) manufactured in accordance with a written design specification which sets out precise layout and design information. Aristocrat compliance plates are made from aluminium with a matt-anodised finish. The “Aristocrat” trade mark appears on the compliance plate together with a notice indicating that it has been affixed in compliance with relevant legislation.

13 A blank Aristocrat compliance plate includes provision for the inclusion of additional information relevant to the gaming machine to which it is or will be affixed including, in particular, the manufacture date, the machine type and a unique serial number which enables the machine to be identified and tracked. This information is engraved into the metal plate in the spaces provided for this purpose. When we refer in these reasons to “blank” compliance plates, we refer to compliance plates which do not include this additional information.

14 Aristocrat commenced their proceedings against Global and Mr Andrews in 2006. They obtained Anton Piller orders which were executed at the Florey premises and the Mascot premises. In 2007 Aristocrat commenced separate proceedings against Impact, Mr Cragen, Tonita and Mr Allam and obtained Anton Piller orders which were executed at (inter alia) the Botany premises, the Georges Hall premises, and the Bankstown premises. The two proceedings were consolidated on 22 June 2007.

15 After a lengthy trial, the primary judge found that each of the Global/Impact respondents and Mr Allam had infringed copyright and each was ordered to pay damages under s 115(2) and s 115(4) of the Copyright Act. His Honour ordered that all respondents except for Tonita pay compensatory damages to the Aristocrat parties under s 115(2) of the Copyright Act. The amounts ordered in Australian dollars were $13,963 in the case of the Global respondents and $34,907 in the case of the Global/Impact respondents and Mr Allam. His Honour also ordered that those respondents pay additional damages to the Aristocrat parties under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act in the amount of $450,000.

16 The primary judge made a number of costs orders. Relevantly, his Honour ordered the Global/Impact respondents and Mr Allam to pay 50% of the Aristocrat parties’ costs incurred on and from the date that the proceedings were consolidated. His Honour also ordered the Aristocrat parties to pay Tonita’s costs of the proceedings in so far as such costs were separate from, or additional to, the costs incurred by Mr Allam.

17 His Honour did not grant the Aristocrat parties any relief with respect to trade mark infringement. It appears that his Honour understood the Aristocrat parties had elected not to press their claims for trade mark infringement in the event that his Honour were to grant relief in respect of copyright infringement.

Primary Judge’s Decision

18 The findings of copyright infringement made by the primary judge against the Global/Impact respondents and the Tonita respondents were based upon what his Honour described as “five essential propositions” including that Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen were each aware that Mr Allam was reproducing (“burning”) Aristocrat gaming software onto blank EPROMs and manufacturing counterfeit compliance plates to be affixed to machines for export to foreign markets, and that they had sent, or authorised the sending of, digital artwork to South America for the purpose of being copied there. We shall refer to those findings by the primary judge as “the knowledge findings”.

19 The five essential propositions referred to by the primary judge, which reflected five key findings, were as follows:

(1) The Tonita respondents (ie. Mr Allam and Tonita) burned Aristocrat game software onto blank EPROMs using Dataman software;

(2) The Tonita respondents manufactured fake Aristocrat compliance plates, some of which were found at the Botany, Bankstown and Georges Hall premises;

(3) Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen were aware that Mr Allam was burning Aristocrat game software onto blank EPROMs;

(4) Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen were aware that Mr Allam was manufacturing compliance plates for export to foreign markets;

(5) Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen sent, or were aware that the Joint Venture had sent digital and original artwork to South America for copying.

20 It is necessary at this point to explain in some detail what evidence was seized from the various premises at which the Anton Piller orders were executed and how they were received into evidence at the trial.

21 The material, seized at the Florey, Mascot and Botany premises was initially admitted against the Global/Impact respondents only. The material seized at the Bankstown and Georges Hall premises was initially admitted against the Tonita respondents only. After the close of the Aristocrat parties’ case, and during the course of closing submissions, the primary judge admitted the seized material provisionally (ie. subject to relevance) against the other respondents against whom it had not already been admitted. Thus, the seized material was ultimately admitted into evidence (at least provisionally) against all respondents.

22 The material seized at the Botany, Bankstown, Georges Hall and Mascot premises included EPROMs and EPROM labels. The EPROM labels that were seized included printed information such as the game name, program number and copyright information. All of the seized EPROM labels included the word “Aristocrat” and the name of a particular Aristocrat game.

23 The material seized from the Bankstown premises included EPROM labels which bore the names “Golden Pyramids”, “Queen of the Nile”, “Chicken”, “Jumping Joey’s”, “King Galah”, “Reel Power”, and “Super Bucks”. The material seized at the Botany premises included a PDF file on a computer which included copies of EPROM labels for “Queen of the Nile” and other Aristocrat games. Each of these labels also included the word “Aristocrat”.

24 Computer equipment was also seized at the Georges Hall premises including, in particular, a loose hard disk drive (“the Loose HDD”) and two desktop computers. The primary judge rejected Mr Allam’s evidence that the Loose HDD was planted at the Georges Hall premises by Mr Channa. One of the two desktop computers (“Desktop 2”) was found by the primary judge to have been used by the Tonita respondents together with Dataman software stored on the Loose HDD to burn Aristocrat game software onto blank EPROMs.

25 The primary judge also found that the EPROMs seized at the Bankstown premises were counterfeit by which we take his Honour to mean that they constituted infringing copies of Aristocrat software. It also appears that the primary judge accepted Mr Channa’s evidence that he saw Mr Allam burning EPROMs at the Botany premises. In so finding, the primary judge rejected Mr Allam’s evidence that he had not used any Dataman software or any other EPROM programmer since leaving his previous employment in 2002.

26 The material seized at the Mascot premises included a motherboard containing EPROMs containing Aristocrat gaming software. The primary judge was satisfied that the labels on these EPROMs were not genuine Aristocrat labels. His Honour referred to evidence given by Mr Andrews to the effect that the motherboard had come from South Australia and was in storage at Global’s Mascot premises awaiting delivery to Botany for refurbishment. Although his Honour accepted that the EPROM labels were not genuine, he was not prepared to find, on that basis alone, that the EPROMs to which they were affixed contained infringing copies of Aristocrat game software.

27 Another important piece of evidence, though not one obtained pursuant to the Anton Piller orders, was a CD-ROM (Exhibit CCC-14) that Mr Channa claimed belonged to Mr Allam that was apparently provided by Mr Channa to the Aristocrat parties. The primary judge found that the CD-ROM included Aristocrat game software including, in particular, software relating to “Dolphin Treasure”, “Queen of the Nile”, “Indian Dreaming”, “Boot Scootin”, “Chicken”, “Orchid Mist”, “Wild Thing” and “Wild Ways”. The primary judge found that the CD-ROM had been viewed on the Loose HDD. He expressly rejected evidence given by Mr Allam that the CD-ROM was fabricated by Mr Channa with a view to falsely incriminating Mr Allam.

28 The material seized at the Botany, Bankstown and Georges Hall premises included blank Aristocrat compliance plates. The primary judge accepted evidence given by Mr Parsons, a witness for Aristocrat, that many of the compliance plates seized at those locations were not genuine and were counterfeits. There were 12 compliance plates seized from the Georges Hall premises, 67 compliance plates seized from the Bankstown premises and another 22 compliance plates seized from the Botany premises. Many of these compliance plates were blank.

29 The primary judge accepted that at least some of the counterfeit compliance plates seized at the Botany premises had been planted there by Mr Channa. However, there was no suggestion that the counterfeit compliance plates found at the Botany premises, even if planted there by Mr Channa, were produced by anyone other than Mr Allam.

30 Mr Allam was found to possess a hand engraver that was used by him for the purpose of engraving compliance plates. He gave evidence that he had only used the hand engraver to engrave compliance plates sourced from what the primary judge identified as the “Uruguay Transaction”, in which the Global/Impact respondents acquired an interest in various Aristocrat gaming machines previously supplied by ATI to a Uruguayan company called Nuevestar SA. Approximately 100 of these gaming machines were delivered to the Botany premises and later re-exported. The primary judge rejected Mr Allam’s evidence that his use of the hand engraver was limited to compliance plates associated with these machines.

31 As the primary judge observed, the significance of Mr Allam’s evidence that he had a hand engraver was that it pointed to the existence of a piece of equipment that was capable of producing the counterfeit compliance plates found at the Botany, Bankstown and Georges Hall premises. According to the primary judge’s findings, all of the counterfeit seized compliance plates, including those found at the Botany premises, were manufactured by Mr Allam.

32 The primary judge admitted into evidence a bundle of documents (most of which were found in Exhibit A1) which included email communications to which one or more of the respondents were privy. Much of this material had been originally tendered and received into evidence against particular respondents only and, according to his Honour’s reasons, not as evidence of the facts stated therein.

33 The Full Court was critical of the primary judge’s decision to receive these documents into evidence against all respondents (even if only on a provisional basis) so late in the trial. It will be necessary for us to refer to the Full Court’s consideration of this issue in greater detail later in these reasons.

34 In support of their claim for damages for copyright infringement, the Aristocrat parties sought to establish that Global was a party to 33 transactions, and that Global and Impact were from 24 May 2004 party to another 21 transactions, whereby a total of 618 “counterfeit” gaming machines were exported from Australia to South America. When we refer to counterfeit gaming machines, we are referring to refurbished gaming machines which included infringing copies of artwork or gaming software or counterfeit compliance plates.

35 Due to difficulties with much of the evidence relied upon by the Aristocrat parties, the primary judge found that only a small number of the 54 transactions relied on by Aristocrat parties were shown to have involved counterfeit gaming machines. This is principally because a data matching exercise upon which the Aristocrat parties relied to prove that many of the relevant transactions involved counterfeit gaming machines was found by his Honour to be flawed and unreliable.

36 It is not necessary for us to explain in any detail why his Honour came to that view. Importantly, however, the Aristocrat parties were able to persuade his Honour that some of the 54 transactions were likely to have involved counterfeit gaming machines. The primary judge found that 11 of the 54 transactions concerned gaming machines that contained “infringing components” of Aristocrat gaming machines and counterfeit Aristocrat compliance plates. Four of these transactions (34, 36, 48 and 54) fell within what was referred to by his Honour as the “Machines in Clubs” (“MC”) category and seven (13, 20, 28, 29, 41, 46 and 51) fell within what he referred to as the “Duplicate Number” (“DN”) category.

37 The evidence included invoices issued by Global for the sale of gaming machines including invoice 1045 dated 5 October 2004 which was for a total of 84 Aristocrat gaming machines supplied to Mr Luis Miguel Novedu Cruzudo of Lima, Peru. These invoices included the serial number of each of the machines referred to in the invoice. The primary judge accepted the evidence of Ms Oldfield, a witness called by the Aristocrat parties, that showed that five of the Aristocrat gaming machines with the same serial numbers appearing in invoice 1045 were operating in hotels and clubs in New South Wales she visited on 23 October 2007. His Honour inferred that these five machines contained counterfeit compliance plates. The primary judge drew the same conclusion from other evidence given by Ms Oldfield in relation to gaming machines the subject of transactions 36, 48 and 54.

38 The seven transactions within the DN category were transactions involving Aristocrat gaming machines which are shown in Global invoices addressed to different customers in different countries (including Peru, Cyprus and Mexico) to have the same serial numbers. Mr Andrews provided a number of different explanations for the existence of the duplicate serial numbers, including that some of the invoices were interim invoices that were superseded by a later transaction. The primary judge did not accept this evidence. His Honour’s rejection of Mr Andrew’s evidence on this topic was plainly influenced by his Honour’s unfavourable assessment of Mr Andrew’s credit.

39 With respect to both the MC category and DN category, the primary judge said that it is not possible to identify which particular components of the machines were in fact counterfeit. Nevertheless, his Honour found that it was more likely than not that the gaming machines with counterfeit compliance plates in the MC category and DN category included counterfeit Aristocrat gaming software. His Honour observed that there would have been little point in having false serial numbers for gaming machines containing genuine Aristocrat software.

40 The primary judge found that Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen were both aware that Mr Allam was infringing copyright. His Honour held that the primary acts of infringement in which Mr Allam engaged were authorised by each of the Global/Impact respondents, that they were performed in furtherance of a common design, and that each of the Global/Impact respondents was guilty of copyright infringement. As previously explained, his Honour did not deal with the Aristocrat parties’ trade mark case.

41 The primary judge held that the total number of what he referred to as “infringing machines” sold in the South American market was 56. Of those 56, there were 16 machines that were sold by the Global respondents prior to 1 October 2004 with the balance sold by the Joint Venture after that date. His Honour assessed compensatory damages on the basis that the Aristocrat parties would have been able to sell 50% of this number (ie. 28 machines) for a profit of US$1,600 per machine. In the result, his Honour assessed compensatory damages in Australian dollars at $13,163 as against the Global respondents and $34,907 against the Global/Impact respondents and Mr Allam. The first of the relevant transactions took place in February 2006 which was, as his Honour pointed out, before Tonita was incorporated.

42 His Honour also assessed additional damages against these respondents at $450,000. In assessing additional damages his Honour found that the infringing conduct of the Global respondents, the Impact respondents and Mr Allam was flagrant and engaged in for commercial gain. His Honour also took into account their “attitude to the litigation” which, on his Honour’s findings, was reflected in their false denials.

The Full court’s Decision

43 The Global/Impact respondents and Mr Allam appealed against the primary judge’s orders. The Aristocrat parties cross-appealed. The results of the various appeals and cross-appeals may be briefly summarised as follows.

44 First, for reasons which we will soon explain, the Global/Impact respondents’ appeal against the primary judge’s findings that they were guilty of copyright infringement and liable to pay damages pursuant to either s 115(2) or s 115(4) of the Copyright Act was successful and the orders made by the primary judge requiring those parties to pay such damages were set aside.

45 Secondly, the Full Court found that, even if the Global/Impact respondents were guilty of copyright infringement, the primary judge erred in his assessment of damages.

46 Thirdly, the Full Court found that the infringements of copyright in the Aristocrat compliance plates which were found to be proven by the primary judge, were not as extensive as his Honour found. This was because the primary judge assumed that each of the counterfeit compliance plates was a substantial reproduction of a relevant copyright work whereas this was true of some, but not all.

47 Fourthly, the Full Court allowed the cross-appeal in so far as concerned the primary judge’s failure to make any findings, or grant any relief, with respect to the Aristocrat parties’ trade mark case.

48 Fifthly, the Full Court also allowed the cross-appeal in so far as it concerned the primary judge’s failure to grant any declaratory or injunctive relief in respect of the Tonita respondents’ infringement of copyright. The Full Court was of the view that there was a need for this issue to be reconsidered by the primary judge in the light of the Full Court’s decision to set aside the damages award made against Mr Allam.

49 The Full Court observed (Allam 1 at [90]) that the primary judge’s findings concerning the burning of game software onto blank EPROMs and the manufacture of counterfeit compliance plates were based substantially on the physical evidence obtained from execution of the Anton Piller orders in 2006 and 2007. However, their Honours also observed (at [92]) that the primary judge’s findings of authorisation and joint tortfeasance (which were necessarily founded upon his Honour’s knowledge findings) were based substantially on facts that his Honour found to have been revealed by chains of email correspondence to which Mr Andrews and Mr Cragen were parties. These included emails relating to the provision of compliance plates for use in refurbished Aristocrat gaming machines that were to be supplied by the Joint Venture to a Mr Mendelson for sale in the Russian market.

50 The Full Court referred to the 11 transactions which the primary judge found to involve infringing conduct at [95] and [96]. Their Honour’s said:

[95] The “MC” (machines in clubs) category described transactions where the serial numbers on invoices for the goods supplied overseas coincided with the serial numbers of gaming machines said to be still located in various premises in New South Wales. The primary judge inferred that the gaming machines with duplicate serial numbers that had been supplied overseas contained “infringing components” of Aristocrat gaming machines (in particular, false compliance plates). The primary judge concluded that it was not possible to identify which particular components of the machines were in fact “counterfeit”. However, on the basis that fake serial numbers had been used, the primary judge found that it was more likely than not that the infringing components included “counterfeit” Aristocrat game software. His Honour reasoned that there would have been little point in having fake serial numbers for gaming machines containing genuine Aristocrat software. The primary judge found that 16 gaming machines, in four transactions, involved infringing components. The transactions were: 34, 36, 48 and 54 (transaction 54 was not included in a table of relevant transactions provided by the Aristocrat parties).

[96] The “DN” (duplicate numbers) category described transactions where the Global parties and Impact parties had issued invoices for machines, the serial numbers of which were a duplicate of serial numbers on machines which had already been shipped by them in earlier transactions. The primary judge rejected the explanation given by the Global parties and Impact parties for the duplicate numbers. As with the MC category, it was not possible to conclude on the evidence which components were “counterfeit”. The primary judge found that 56 gaming machines, in 7 transactions, involved infringing components. The transactions were: 13, 20, 28, 29, 41, 46 and 51.

(emphasis added)

51 It is important to note that the logic underpinning the primary judge’s conclusion that the machines with false compliance plates included infringing components (in particular, “counterfeit” Aristocrat game software) was that the use of false serial numbers on the relevant gaming machines gave rise to what the Full Court described at [131] as the “reasonable inference” that they included counterfeit Aristocrat game software.

52 After referring to some of the other categories of transactions that the primary judge rejected because of the problems relating to the data matching exercise, their Honours said at [98]:

[98] It is important to note that the findings the primary judge made with respect to the four “MC” category transactions and the seven “DN” category transactions were findings with respect to indirect infringement of copyright under s 38 of the Copyright Act (infringement by dealing). These findings were based on inference in light of the “five essential propositions” to which reference has been made. There was no direct evidence of infringement. No infringing article was produced. Indeed, the Aristocrat parties did not inspect any of the gaming machines involved in any of the transactions that were found to involve infringements of the copyright that was claimed. The Aristocrat parties did not identify which components of the gaming machines in the impugned transactions were alleged to infringe the copyright that was claimed. As noted earlier, the primary judge found that, on the evidence, it was not possible to conclude precisely which components in the machines were infringing or counterfeit.

53 The Full Court concluded that the primary judge’s knowledge findings were based upon his consideration of the contents of the email chains. The effect of the Full Court’s decision was that it was not open to the primary judge to rely upon the email chains as he did and therefore it was not open to his Honour to find that the Global/Impact respondents were guilty of copyright infringement. It was on the basis of that determination that the Full Court set aside the orders made by the primary judge against the Global/Impact respondents. The Full Court said at [234]-[238]:

[234] The Aristocrat parties charted their own course. It may have been anticipated a variation to the usual s 136 ruling could be made after the cross-examination of opposing witnesses, but not at the time of final submissions when the course of evidence had been well completed.

[235] The primary judge failed to appreciate the real nature of the application made by the Aristocrat parties on 30 April 2011 to vary the usual s 136 ruling. As we have indicated, it was to re-open the case of the Aristocrat parties. However, to allow the emails to be introduced as evidence against respondents who had not been required to respond in any way to the email evidence, even if tendered for what their contents revealed against other respondents, was to put the respondents in an unsatisfactory position.

[236] This was a strongly contested proceeding, and each party was in a position to know and adhere to the rules of evidence and procedure to be applied. If the emails had been tendered against a particular respondent prior to 30 April 2009, then in a case of this complexity, a different course may well have been adopted by the respondent in question. It is important again to appreciate that by the usual s 136 ruling the evidence covered by that order was not admitted against certain respondents, even provisionally. The variation that occurred on 30 April 2009 during the course of the final addresses was to admit the evidence against all respondents, albeit provisionally subject to relevance.

[237] Therefore, the position of the respondents was that on 30 April 2009 they were confronted with different evidence upon which to make submissions as to liability and relevance.

[238] We do not think it was incumbent on any respondent to consider whether to re-open its or his case. The Aristocrat parties’ case was completed, cross-examination undertaken and responsive evidence led by the respondents as necessary during the course of the trial. Of course, the Aristocrat parties were entitled to lead evidence as to the alleged infringing transactions and the joint venture activities, but that evidence needed to be put before the Court, subject to specific agreement by the respondents, before the case was completed. The proper course to have followed was for the evidence to be admitted provisionally at the outset against all the respondents, and then for it to have been considered in submissions. In this proceeding, it was too late to admit the evidence during closing submissions, as it was, even on a provisional basis.

54 The Full Court went on to explain why the use made by the primary judge of the chain of emails was otherwise impermissible. The Full Court said at [240]-[245]:

[240] At this point, it must be reiterated that the applicants’ case at trial was primarily based on circumstantial evidence which the applicants sought to relate to a number of transactions in which some or all of the respondents were said to have exported counterfeit gaming machines to Latin America. A second critical point to note is that the significant emails tendered did not relate to the alleged infringing transactions. So in themselves, these emails could have had no relevance to proving that the alleged transactions occurred. However, they could have use in discrediting witnesses or proving the existence of a joint venture. This appears to be the way in which they were used by the parties.

[241] The primary judge accepted that the emails were not tendered as proof of the facts stated in them. It seems that the emails were tendered without express qualification at the time of their tender. Nevertheless, we consider that the primary judge did treat the contents of the chain of emails as supporting more than just the existence of the joint venture, or as going beyond being only relevant to credit. The primary judge necessarily had to connect the particularised infringing transactions with the joint venture. The only way that he could have made this connection was to draw the inference from the contents of the emails that the respondents had the tendency to act in a particular way, that is, engage in the alleged infringing transactions.

[242] The admissibility of tendency evidence is tightly regulated by Pt 3.6 of the Evidence Act. Tendency evidence is evidence of “character, reputation or conduct of a person, or a tendency that a person has or had… to act in a particular way, or to have a particular state of mind”: s 97(1) of the Evidence Act. There are specific dangers in treating evidence of tendency as being probative of the occurrence of a fact in issue. In this respect, Pt 3.6 contains a number of safeguards to limit the potential misuse of tendency evidence.

[243] Under s 97(1)(a), if a party seeks to adduce tendency evidence, that party must give reasonable notice to the other party that they intend to do so. Under s 97(1)(b), the Court will only admit that evidence if it has “significant probative value”. However, the threshold requirement of notice was not given at trial; the Aristocrat parties did not seek to use the emails as evidence that the respondents at trial had a tendency to engage in the infringing conduct. On appeal, it was confirmed that the parties did not seek to rely on Pt 3.6 of the Evidence Act.

[244] Whilst the emails were admitted into evidence for other purposes (namely credit, and evidence of the joint venture) Pt 3.6 guards against the evidence being admitted to show a tendency even if the evidence has a dual purpose (for example, it is also relevant and admissible to proving the existence of a joint venture): see s 95. This is to be contrasted with other provisions of the Evidence Act relating to hearsay evidence, whereby if hearsay evidence has a non-hearsay purpose (for example, is also relevant to credit) it can be admitted for its hearsay purpose: s 60. The primary judge was right in saying that he should not rely on the contents of the emails for the truth of their contents, but fell into error in doing just that in relying upon evidence that did not relate to the particularised infringing transactions. Used in this way, the evidence in the emails could show nothing more than a tendency on the part of the respondents at trial to engage in infringing transactions.

[245] The error the primary judge made was to treat the chain of emails as being able to prove the particularised infringing transactions, and to use the contents of the emails to demonstrate the connection with the particularised infringing transactions with the joint activity. Without the chain of emails, the primary judge could not have found such connection to the infringements as alleged.

55 It is important to read this last paragraph in its proper context. The principal case against the Global/Impact respondents was that they had supplied, or authorised the supply of, infringing gaming machines to customers in South America and had thereby infringed copyright. The Global/Impact respondents could only be liable on this basis if they knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the gaming machines in Australia constituted or, in the case of imported machines, would have constituted, if they had been made in Australia, an infringement of copyright: see s 38 of the Copyright Act. The Full Court found that the primary judge relied upon the chain of emails as evidence that the Global/Impact respondents knew that the gaming machines sold to their customers in South America had been made in Australia in breach of copyright.

56 The Full Court referred to the primary judge’s five essential propositions (reproduced at [19] above) including, in particular, propositions 3, 4 and 5 or what we have referred to as his Honour’s knowledge findings. The Full Court said at [246]:

Therefore, the findings of the primary judge in relation to the third, fourth and fifth “essential propositions” cannot be supported, and the Aristocrat parties fail to prove the alleged infringing transactions, even accepting proof of a joint venture. Looking at the primary judge’s findings in relation to these propositions they extensively relied upon the chain of emails – see [751] to [752], [754] to [756], and [757] to [762]. No attempt was made by the Aristocrat parties before the primary judge or before us to prove the “essential propositions” without reference to the emails relied upon by the primary judge. It seems to be accepted that without reliance upon the emails, the third, fourth and fifth “essential propositions” cannot be supported, and the case brought by Aristocrat must fail.

57 The position in relation to Mr Allam is slightly different. The Full Court accepted that Mr Allam had infringed ATA’s copyright in Aristocrat game software and Aristocrat compliance plates but found that the quantum of damages awarded against Mr Allam could not be justified. The Full Court rejected the Aristocrat parties’ submission that the Full Court should itself re-assess damages against Mr Allam on a different basis or that it should remit the matter to the primary judge so that he might do so.

58 There appears to be a minor discrepancy as to the total number of impugned gaming machines in the 11 relevant transactions in the MC and DN categories (those being 34, 36, 48 and 54 in the MC category and 13, 20, 28, 29, 41, 46 and 51 in the DN category). The number of impugned gaming machines range somewhere between 46 and 56; even accounting for the “double counting” of 4 gaming machines as identified by the Full Court in Allam 1 at [291], there are at least 48 impugned gaming machines across both the MC and DN categories. The references to 48 impugned gaming machines in these reasons should be understood against that background.

The Primary Judge’s Remittal Decision

59 In his reasons for judgment, the primary judge refers in some detail to his reasons in Aristocrat 1 and the Full Court’s reasons in Allam 1.

60 His Honour made some specific observations in relation to the counterfeit compliance plates found at the Botany premises, the CD-ROM (Ex CCC-14) and the Loose HDD. As to the compliance plates found at the Botany premises, his Honour said at [21]-[23]:

[21] The other evidentiary material which was the subject of my usual s 136 ruling consisted of seized gaming machine components including EPROMs, EPROM labels, game software, artwork and compliance plates. These items were seized from the Florey, Mascot and Botany premises of the Global/Impact respondents and the Bankstown and Georges Hall premises of the Tonita respondents: [Aristocrat 1] at [376], [377].

[22] The seized materials included 22 compliance plates that were not genuine Aristocrat compliance plates. These items were seized at the Botany premises of Impact and were therefore admitted evidence against it.

[23] Mr Channa gave evidence that he had planted counterfeit compliance plates, manufactured by the Tonita respondents, at Impact’s Botany premises. I accepted evidence given by him that the compliance plates were planted in a ceiling at Botany where they were seized by the Aristocrat Companies in an Anton Piller raid: [Aristocrat 1] at [370], [371].

61 His Honour then referred to the CD-ROM, which Mr Channa claimed to have obtained from Mr Allam and the Loose HDD that had been seized from the Georges Hall premises, both of which were initially admitted against the Tonita respondents. His Honour said at [24]-[25]:

[24] Mr Channa’s evidence also included a CD-ROM which became Exhibit CCC-14 in the proceedings. His evidence was that he obtained the CD-ROM from one of the Tonita respondents, Mr Allam. Ex CCC-14 contained binary game files comprising Aristocrat game software and was admitted, initially, against the Tonita respondents: [Aristocrat 1] at [530], [531].

[25] Another significant item of evidence was a loose hard disk drive known as the “Loose HDD” which was seized from the Tonita respondents’ Georges Hall premises. The Loose HDD contained software that was said to have been used by the Tonita respondents to burn Aristocrat game software onto EPROMS: [Aristocrat 1] at [496], [503].

62 His Honour also referred to his adverse credit findings against Mr Andrews, Mr Cragen and Mr Allam.

63 The primary judge observed that the Full Court accepted that his acceptance of proposition 1 was open and not affected by error. His Honour also observed that his acceptance of proposition 2, was also accepted by the Full Court as open, but that the evidence demonstrated only two instances of copyright infringement involving the sale of a gaming machine with a compliance plate the making of which constituted infringement of copyright in a relevant work.

64 So far as propositions 3, 4 and 5 were concerned, the primary judge noted that the Full Court’s reasons focused on the email communications the subject of the “usual s 136 ruling” at the time they were first tendered. His Honour noted that the Full Court held that he should not have admitted this material into evidence against all respondents during the course of closing submissions, and that it was admissible only against the parties in respect of whom it was originally tendered and admitted.

65 His Honour noted that it was in light of the Full Court’s conclusion in [246] of its reasons that the appeals against his Honour’s judgment requiring each of the respondents to pay damages were allowed. His Honour said in Aristocrat 3 (at [50]-[54]):

[50] The Full Court stated in plain terms that I was in error in relying upon the emails to reach the conclusion that the infringing transactions occurred. But the emails did not provide the basis for my findings that the transactions took place. Rather, as the Full Court concluded at [246] the error which I made in admitting the emails against all respondents had the effect that the third, fourth and fifth propositions could not be supported.

[51] Thus, when their Honours went on to say at [246] that “the Aristocrat parties fail to prove the alleged infringing transactions”, this must be read in light of the words which precede that statement.

[52] The third, fourth and fifth propositions were findings of knowledge on the part of the Global/Impact respondents of the fact that Mr Allam burned Aristocrat game software and manufactured fake compliance plates and that they were, or ought to have been, aware of other infringing activities.

[53] The findings of knowledge were essential to the findings of infringement against the Global/Impact respondents by reason of their authorisation of the relevant primary acts, under s 36 of the Copyright Act and infringement by dealing under s 38 of the Copyright Act.

[54] The rejection of the Full Court of my third, fourth and fifth propositions therefore had the effect that the findings made against the Global/Impact respondents of copyright infringement in relation to the 11 identified transactions were set aside.

66 His Honour noted that the Full Court said that he did not err in finding that the gaming machines in the MC category and DN category included fake compliance plates and counterfeit game software. In particular, his Honour noted that the Full Court did not overturn his findings that the impugned gaming machines contained Aristocrat game software reproduced by Mr Allam and that Mr Allam also manufactured fake compliance plates. His Honour said that it followed that the findings he made that the gaming machines which were included in the 11 transactions contained fake compliance plates and counterfeit gaming software were not affected by the Full Court’s decision and that he must therefore proceed upon the basis that the Global/Impact respondents sold the gaming machines that were the subject of those 11 transactions to their customers who were principally located in South America. His Honour said at [58]-[60]:

[58] It follows in my view that the findings which I made that the machines which were the subject of the 11 transactions contained “fake compliance plates” and “counterfeit gaming software” are not affected by the Full Court’s decision in Allam No 1. Nor is the finding disturbed that the transactions were documented in the invoices for the 11 transactions to which I referred.

[59] Those transactions were, as I have emphasised, sales made by the Global/Impact respondents of gaming machines which contained fake compliance plates and counterfeit game software, although it is not possible to otherwise identify which components of the gaming machines were not genuine Aristocrat components.

[60] What is critical is, as the Full Court observed, the transactions were documented on the Global/Impact respondents records, that is to say the invoices which were the subject of the 11 identified transactions.

67 The primary judge noted that although his findings that the Global/Impact respondents were aware that Mr Allam burned the Aristocrat game software and manufactured counterfeit Aristocrat compliance plates did not survive the Full Court’s decision, questions of knowledge were not relevant to the trade mark case.

68 His Honour rejected a submission by Mr Einfeld QC on behalf of the Global/Impact respondents that there was no admissible evidence against them of any dealing capable of amounting to trade mark infringement. In rejecting this submission his Honour concluded that on his analysis of the Full Court’s reasons, there were 11 transactions involving the sale of gaming machines containing fake compliance plates and counterfeit game software.

69 The primary judge then referred to what he characterised as a concession made by Mr Cobden SC (then appearing for the Aristocrat parties) at the trial. His Honour said at [75]-[76]:

[75] Mr Cobden [stated] that the case was put very narrowly so that the “radical alteration” of the machines by the insertion of counterfeit EPROMs and the application of false compliance plates was sufficient to amount to an infringement of Aristocrat’s trade marks.

[76] The following relevant statements were made:

mr cobden: What we say is that if the placing of infringing parts in the machine, and then the replacing it back into trade badged with Aristocrat but containing infringing EPROMs that would be enough. If your Honour is against us on that then we don’t win the trade mark case. … The compliance plate of course itself has the Aristocrat mark on it in the fancy form as it’s called, I think, in the trade mark records. That’s with the O and things like that.

…

mr cobden: And the application of a false compliance plate would we say amount to an infringement of the trade mark if, but only if, the machine had been altered in the way I‘ve put it.

70 The primary judge then referred to various legal principles relevant to the trade mark case including, in particular, those concerned with trade mark use. His Honour also referred to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) which provides that a person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is “substantially identical with” or “deceptively similar” to the registered mark. As his Honour pointed out, s 120(1) requires that the use as a trade mark be in relation to goods or services in respect of which the mark is registered.

71 As to the test of substantial identicality, the primary judge said at [88]-[89] that it involves a side by side comparison whereas the test of “deceptive similarity” involves a comparison between the impression based upon recollection of the registered mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, and the impressions such persons would have of the impugned marks. In support of these well-known propositions the primary judge referred to the judgment of Windeyer J in Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414-415.

72 The primary judge then referred to various authorities relied upon by the Global/Impact respondents concerned with the concept of trade mark use. These authorities included Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19] (Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ) and E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [43].

73 His Honour noted a submission that was made to him by the Global/Impact respondents which, as summarised by his Honour at [93], was to the following effect:

… a person who affixes a mark to goods so as to indicate a connection between the goods and the owner of the registered mark does not infringe the trade mark … use “as a trade mark” requires use which serves to indicate a connection between the registered mark and the infringer; that is to say in the present case to identify the Global/Impact respondents as the origin of the goods.

74 His Honour rejected this submission. His Honour said at [97] that the authorities supported the proposition that a sale of goods bearing a mark applied without the consent of the owner infringes the mark because the mark is used to indicate, contrary to the fact, a connection between the goods and the registered owner. His Honour referred to Paul’s Retail Pty Ltd v Lonsdale Australia Limited (2012) 294 ALR 72 (Keane, Jagot and Yates JJ) at [68] and Brother Industries Ltd v Dynamic Supplies Pty Ltd (2007) 163 FCR 530 (Tamberlin J) in support of that proposition. His Honour also noted at [98] that “[k]nowledge by the seller of the goods that the sale of the goods bearing that mark would amount to infringement is not an element of that test”.

75 This brings us to the crux of the primary judge’s reasons for rejecting the Aristocrat parties’ trade mark case. His Honour said that there was a short answer to the trade mark case which he explained at [101]-[107]:

[101] It is true that the effect of the Full Court decision is, as I have said that the Global/Impact respondents sold machines with counterfeit compliance plates and counterfeit games.

[102] However, the difficulty which arises is that this was a circumstantial case. The Aristocrat Companies have the onus of proving infringement. But the failure to produce a single machine containing a counterfeit compliance plate or a counterfeit game makes it impossible to conduct the tests stated by Windeyer J in Shell. I cannot conduct a side by side comparison. Nor can I carry out a comparison of the impression based on recollections of the person of ordinary intelligence.

[103] Thus, whilst the machines which were the subject of the transactions contained signs which must be accepted to be counterfeit, the difficulty is that Aristocrat has failed to prove which of the machines contained counterfeit Aristocrat plates and which contained counterfeit Aristocrat games. Moreover, it would be necessary to demonstrate which game or games were installed on each machine. This has not been established.

[104] In my opinion, it is not possible to perform either of the comparisons required under the necessary test by a process of inference. This is because I would need to be satisfied of the particular acts of infringement taking into account the matters referred to in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). This is analogous to the requirements of the test in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 which requires exactness of proof and actual persuasion.

[105] The evidence which was admissible against the Global/Impact respondents consisting of the materials seized at their premises does not assist the Aristocrat Companies. This is because they do not enable the comparison test to be carried out.

[106] The counterfeit compliance plates planted by Mr Channa at the Botany premises are not admissible against the Global/Impact respondents. Even if they were, they do not assist because they cannot be linked to the transactions.

[107] These difficulties seem to me to be acknowledged in Mr Cobden’s concession at [76] above. What was required was evidence of an infringing machine, radically altered in the manner suggested, so that I could determine whether the machines as a whole, or some components thereof, fell within the monopoly conferred by the registered trade marks. No such evidence was admitted.

76 His Honour disposed of the trade mark case against Mr Allam by the same process of reasoning.

77 His Honour said at [109] that the evidence did not permit him to determine which of the machines contained the Aristocrat game software or the particular games that were installed in each machine.

78 It is useful at this point to examine his Honour’s reasoning in greater detail.

79 First, the primary judge recognised that the effect of the Full Court’s decision was that the Global/Impact respondents sold machines with counterfeit compliance plates and counterfeit games. This accords with the primary judge’s previous findings which were not disturbed by the Full Court.

80 Secondly, the primary judge observed that the Aristocrat parties’ case was “circumstantial”. But in his Honour’s view, the failure to produce any gaming machine containing either a counterfeit compliance plate or a counterfeit game made it impossible to determine the question of infringement using a “side by side” or an “impression based” comparison.

81 Thirdly, his Honour was of the view that the evidence seized at the Global/Impact respondents’ premises did not enable him to carry out the necessary comparisons. His Honour said that the counterfeit compliance plates seized from the Botany premises planted by Mr Channa were not admissible against the Global/Impact respondents and, even if they were, they could not be linked to the relevant transactions.

82 Fourthly, the primary judge was of the view that the allegations made were of such seriousness, that in the absence of “a single machine containing a counterfeit compliance or a counterfeit game”, it was impossible for the Aristocrat parties to satisfy him by a process of inference that any of the respondents had infringed the Aristocrat parties’ trade marks on the evidence before him. We think this is apparent from his Honour’s references to s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 and his reference to “exactness of proof and actual persuasion”.

83 Fifthly, the evidence did not enable the primary judge to determine whether any particular gaming machine had been “radically altered” so that his Honour could “determine whether the machines as a whole, or some components thereof, fell within the monopoly conferred by the registered trade marks”.

The Appeal

84 The Aristocrat parties challenged the correctness of the primary judge’s reasoning in dismissing the trade mark case and submitted that his Honour erred by failing to give effect to his own findings. They also submitted that the primary judge misunderstood and misapplied the decision in Shell.

85 The primary judge appears to have considered himself bound to dismiss the trade mark case in light of the test of infringement propounded by Windeyer J in Shell. In our respectful view, the primary judge erred in approaching the trade mark case in this way. Before explaining why his Honour erred, it is desirable that we refer in a little more detail to the High Court’s decision in Shell.

86 The plaintiff in Shell was the owner of a number of registered trade marks for the caricature of a man in the shape of an oil drop with a large head and arms. One of the registered marks included the word “Esso”, which was the trade name of the plaintiff’s lubricating products. The defendant was alleged to have infringed the registered marks by the use in advertising of its own caricature of a man in the shape of an oil-drop in two television commercials in which the defendant’s caricature engaged in various antics. The question was whether the use of these moving depictions, in which the shape and appearance of the defendant’s caricature was constantly changing, infringed the registered marks.

87 In a passage of the judgment referred to by the primary judge in this case, Windeyer J said at 414-416:

In considering whether marks are substantially identical they should, I think, be compared side by side, their similarities and differences noted and the importance of these assessed having regard to the essential features of the registered mark and the total impression of resemblance or dissimilarity that emerges from the comparison. “The identification of an essential feature depends”, it has been said, “partly on the Court’s own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it” : de Cordova v. Vick Chemical Co. [(1951) 68 RPC 103 at p 106]. Whether there is substantial identity is a question of fact: see Fraser Henleins Pty Ltd v. Cody [(1945) 70 CLR 100]), per Latham C.J. [(1945) 70 CLR at pp 114, 115.], and Ex parte O’Sullivan; Re Craig [(1944) 44 SR (NSW) 291], per Jordan C.J. [(1944) 44 SR (NSW), at p 298], where the meaning of the expression was considered. Judging by the eye alone, as I think is proper for the determination of substantial identity, my opinion is that in each film there are one or more moments when the personified figure of the oil-drop appears in a form that is substantially identical with the registered mark. If the films were arrested at these moments and the image displayed in still form, I consider that use of a substantially identical mark would be established. But that is not what happens. The figure does not stand still. It does not hold its pose or expression for long enough, nor is it sufficiently isolated from its surroundings for long enough to establish infringement by the use of a substantially identical mark. That is my conclusion. But these fleeting glimpses of substantial identity are, I think, significant when one comes to consider deceptive similarity. To that I now turn.

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant’s television exhibitions. To quote Lord Radcliffe again: “The likelihood of confusion or deception in such cases is not disproved by placing the two marks side by side and demonstrating how small is the chance of error in any customer who places his order for goods with both the marks clearly before him … It is more useful to observe that in most persons the eye is not an accurate recorder of visual detail, and that marks are remembered rather by general impressions or by some significant detail than by any photographic recollection of the whole”: de Cordova v. Vick Chemical Co [(1951) 68 RPC at p 106.]. And in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v. F. S. Walton & Co. Ltd. [(1937) 58 CLR 641] Dixon and McTiernan JJ. said: “In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same” [(1937) 58 CLR at p 658]).

Windeyer J proceeded to make a finding of deceptive similarity and granted an injunction restraining the defendant from further infringing the registered marks.

88 The defendant’s appeal against Windeyer J’s judgment was allowed. The leading judgment was delivered by Kitto J (with whom Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Taylor and Owen JJ agreed) who concluded that, on the assumption that there was “for a moment or two now and then” a substantial identicality between the defendant’s caricature and the registered marks, the use of the defendant’s caricature did not amount to infringing use because it was not use as a trade mark.

89 Kitto J held that, as a matter of statutory construction, s 58(1) and s 62(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth), when referring to use of a trade mark, were to be understood as referring to use of a trade mark “as a trade mark”. His Honour said at 422:

The question, then, is whether such a user of the oil drop figure as takes place by the exhibition of the films on television involves infringement of the trade marks. It is a question not to be answered in favour of the appellant merely by pointing to the brevity of the occasions when substantial identity is achieved. The assumption I have made means, of course, that if the oil drop figure as appearing in some of the individual frames of the films were transferred as separate pictures to another context the use of the pictures in that context could be an infringement. But the context is all-important, because not every use of a mark which is identical with or deceptively similar to a registered trade mark infringes the right of property which the proprietor of the mark possesses in virtue of the registration.

90 In the context of this implied statutory requirement that the use of a trade mark amount to “use as a trade mark” Kitto J postulated the following question for the purpose of determining whether the defendant used either of the registered marks as a trade mark at 424-425:

Was the appellant’s use, that is to say its television presentation, of those particular pictures of the oil drop figure which were substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the respondent's trade marks a use of them “as a trade mark”?

With the aid of the definition of “trade mark” in s. 6 of the Act, the adverbial expression may be expanded so that the question becomes whether, in the setting in which the particular pictures referred to were presented, they would have appeared to the television viewer as possessing the character of devices, or brands, which the appellant was using or proposing to use in relation to petrol for the purpose of indicating, or so as to indicate, a connexion in the course of trade between the petrol and the appellant. Did they appear to be thrown on to the screen as being marks for distinguishing Shell petrol from other petrol in the course of trade?

[emphasis added]

91 We have emphasised the penultimate sentence of his passage because it assumed considerable significance in the respondents’ submissions concerning the notices of contention and the concept of trade mark use. We will say more about this aspect of Kitto J’s judgment later in these reasons when considering the respondents’ submissions on the point. At this stage we merely observe that s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) expressly requires that use of a mark be use “as a trade mark” for it to amount to infringing use.

92 Although the appeal against Windeyer J’s judgment in Shell was upheld, nothing was said by the Full Court that cast doubt on Windeyer J’s exposition of the test of “substantial identity” or “deceptive similarity”. But the context in which his Honour’s exposition occurred is important. His Honour was able to view the television commercials in question and compare the caricatures depicted in them with the registered trade marks. His Honour was not concerned with the question of how the test of substantial identicality or deceptive similarity might be applied in circumstances where for one reason or another a copy of the television commercials was not in evidence and therefore not available to be viewed by the Court. In particular, his Honour was not confronted with a situation in which he could not undertake a direct visual comparison of the infringing mark and the registered mark.

93 In the present case the primary judge found that 11 transactions entered into between the Global/Impact respondents and their South American customers related to 56 gaming machines that included fake compliance plates and counterfeit gaming software. None of these findings was disturbed by the Full Court. That is not to say that the Full Court accepted that each of the fake compliance plates infringed copyright. The Full Court concluded that the evidence justified a finding that only some of the compliance plates seized infringed copyright. As the Full Court said at [165]:

… Although the evidence justified the primary judge’s conclusion (at [719]) that the Allam parties were manufacturing fake Aristocrat compliance plates, it did not follow necessarily that those fake compliance plates were also infringing reproductions of original artistic works in which Australian copyright subsisted.

94 But for the purpose of determining the trade mark case the first question is whether it should be inferred that the fake compliance plates included the word “Aristocrat”. The primary judge’s findings, which refer to the relevant plates expressly as “fake Aristocrat compliance plates”, plainly indicate that his Honour was satisfied that they did. The inference is in our view irresistible that the fake compliance plates that his Honour found had been fitted to the gaming machines that formed part of the 11 transactions bore the word “Aristocrat”. Once it is concluded, as it must be, that each of the fake Aristocrat compliance plates bore the word “Aristocrat” the test of “substantial identicality” was plainly satisfied. In our respectful opinion, the primary judge erred in concluding that it was “impossible to conduct the tests stated by Windeyer J in Shell”.

The Contentions

95 We turn now to the various arguments raised by the respondents in their notices of contention.

The “usual s 136 rulings”

96 Paragraph 4 of the Global/Impact respondents’ amended notice of contention asserted:

Despite acknowledging (at [21]-[25], [42]) that the seized gaming machine components found at the premises of Tonita Enterprise Pty Limited and Mr Allam were not admissible against the first, second, third and fifth respondents (“the Global Respondents”) by reason of the ‘usual s. 136 rulings’, the primary judge erred by nevertheless concluding (at [58]) that the machines the subject of the 11 transactions contained “fake compliance plates” and “counterfeit gaming software”.

97 We have already referred (at [60]-[61]) above to his Honour’s reasons at [21]-[25] of Aristocrat 3. His Honour said at [42]:

Their Honours concluded that I was in error in varying my usual s 136 ruling in the course of closing addresses. The effect of what they said at [234]-[238] was that I ought not to have admitted the evidence which was the subject of that ruling against all of the respondents. Thus it was admissible only against the parties in respect of whom it was originally tendered and admitted.

98 We have already set out (at [53] above) paragraphs [234]-[238] of the Full Court judgment. It is apparent from a consideration of those paragraphs that they relate to what is expressly referred to in [235] as “the email evidence”. It was the use made of that evidence which the Full Court concluded at [235] put the respondents against whom they were not tendered in an “unsatisfactory position”. With great respect to the primary judge, we think [42] of his Honour’s reasons overstates the effect of the Full Court’s reasoning in [234]-[238].

99 In Aristocrat 1 the primary judge concluded (inter alia) that the impugned gaming machines sold by the joint venture had fake compliance plates affixed and counterfeit game software installed. This conclusion was based principally upon inferences drawn from the following evidence:

the existence of duplicate serial numbers on gaming machines in the MC category and the DN category;

the existence of fake compliance plates found at the Bankstown, Georges Hall and Botany premises;

Mr Allam’s possession of engraving equipment;

counterfeit EPROMs found at the Bankstown and Botany premises and blank EPROMs found at the Georges Hall premises;

the existence of the CD-ROM (Ex CCC-14) which contained copies of Aristocrat game software;

the Loose HDD (which included the Dataman software) and Desktop 2 found at the Georges Hall premises used by Mr Allam to burn Aristocrat game software onto blank EPROMs.

100 The primary judge’s findings with respect to duplicate serial numbers depended upon an analysis of the Global/Impact respondents’ business records, Ms Oldfield’s evidence and a rejection of Mr Andrew’s explanations as to how it was that gaming machines exported by the Global/Impact respondents to South America may have serial numbers that were identical to those appearing in business records relating to different transactions including other gaming machines previously supplied by them and gaming machines found in the licensed premises visited by Ms Oldfield.

101 The presence of fake compliance plates found at the Bankstown premises and the Georges Hall premises was evidence that was relevant to the issue of whether Mr Allam affixed fake compliance plates to the impugned machines. The fake compliance plates found at these locations were physical objects, sometimes referred to as “real evidence”, that could rationally affect, directly or indirectly, the determination of whether Mr Allam was a source of fake compliance plates allegedly affixed to the impugned gaming machines. In particular, the existence of the fake compliance plates, and Mr Allam’s possession of the hand engraver, was evidence from which it might rationally be inferred, that Mr Allam had the technical skills and resources necessary to produce fake compliance plates allegedly affixed to the impugned gaming machines.

102 Other physical objects obtained at the premises with which Mr Allam was connected, including the Loose HDD, Desktop 2, the EPROMs and EPROM labels were also admissible on the basis that it could rationally affect, directly or indirectly, the determination of whether Mr Allam was a source of counterfeit gaming software allegedly installed on the impugned gaming machines.

103 This same evidence was also relevant to the case against the Global/Impact respondents because it was open to infer that it was Mr Allam who determined what compliance plates and EPROMs were used in the gaming machines supplied by the Global/Impact respondents.

104 As to the fake compliance plates found at the Botany premises, it is important to note that the primary judge, while mindful that Mr Channa planted fake compliance plates at the Botany premises, found that a strong inference arose that the counterfeit compliance plates seized at the Georges Hall, Bankstown and the Botany premises were counterfeit and that they had been made with the authority of the Tonita respondents (see Aristocrat 1 at [737]-[743]).