FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Appellant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted pursuant to s 158(2) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) to appeal against the orders of the Honourable Justice Middleton made on 16 September 2013.

2. The appeal be allowed.

3. Orders 1 to 5 of the orders made by the Honourable Justice Middleton on 16 September 2013 be set aside and, in lieu thereof, order that:

(a) the appeal to the Federal Court from the decision of the delegate of the Commissioner of Patents made on 12 July 2011 be dismissed; and

(b) The applicant, RPL Central Pty Ltd, pay the respondent’s costs of that appeal, such costs to be taxed in default of agreement.

4. The respondent, RPL Central Pty Ltd, pay the appellant’s costs of and incidental to the appeal to the Full Court of the Federal Court, such costs to be taxed in default of agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1023 of 2013 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS Appellant |

AND: | RPL CENTRAL PTY LTD Respondent |

JUDGES: | KENNY, BENNETT AND NICHOLAS JJ |

DATE: | 11 December 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

the court

1 This is an application for leave to appeal and, if granted, an appeal from the decision of the primary Judge in RPL Central Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2013] FCA 871. The issue in the appeal is whether the claimed invention of innovation patent application No. 2009100601 (entitled “Method and System for Automated Collection of Evidence of Skills and Knowledge”) (the Patent Application) is a manner of manufacture under s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act).

2 The background is set out at [5] to [10] of the primary Judge’s reasons. Briefly stated, the respondent (RPL Central) filed the Patent Application on 22 June 2009. A delegate of the Commissioner of Patents (the Delegate) refused the Patent Application on the basis that the claims were not to a manner of manufacture within s 18(1A)(a) of the Act. RPL Central appealed the Delegate’s decision and the primary Judge granted the appeal on the basis that the claimed invention was to a manner of manufacture.

LEAVE TO appeal

3 Leave to appeal to the Full Court is required by s 158(2) of the Act which provides:

Except with the leave of the Federal Court, an appeal does not lie to the Full Court of the Federal Court against a judgment or order of a single judge of the Federal Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from decisions or directions of the Commissioner.

4 The Commissioner seeks leave on the basis that the present case raises an issue of importance, although, she concedes that the principle of finality does not arise, as any person seeking to revoke a patent granted on the Patent Application may raise the ground of no manner of manufacture in a revocation suit. The Commissioner submits that the applicability of the Full Court’s decision in Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents (2014) 227 FCR 378 to cases such as the present warrants the grant of leave. The Commissioner also points out that the primary Judge reached a different conclusion to that of the Delegate, which is a ‘significant factor in deciding whether to grant leave to appeal’ (Imperial Chemical Industries PLC v EI Dupont De Nemours & Co [2002] FCAFC 264; [2002] AIPC 91-818 at [11]).

5 RPL Central does not accept that there is any question of importance that warrants the grant of leave under s 158(2) of the Act. RPL Central submits that the primary Judge applied, as did the Full Court in Research Affiliates, the guiding principles enunciated by the High Court in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252 (NRDC) as applied in Grant v Commissioner of Patents (2006) 154 FCR 62 (Grant). Accordingly, RPL Central argues that the decision of the primary Judge is consistent with Research Affiliates even though a different conclusion was reached concerning the Patent Application. The Commissioner argues that the Full Court’s guidance in Research Affiliates as to the application of NRDC and Grant to inventions such as that claimed in the Patent Application was not available to the primary Judge. That is, she says, the primary Judge’s decision is in conflict with Research Affiliates; further, the primary Judge erred in his Honour’s application of NRDC and Grant and other authorities to the issue of computer implementation of business methods. Accordingly, the Commissioner submits, it is in the public interest to resolve this conflict rather than to develop two strands of authority.

6 The Court reserved the question of leave and heard the arguments for leave together with the appeal.

The Patent Application

7 The field of the invention is said to relate to assessing the competency or qualification of individuals with respect to recognised standards. It is said to be particularly applicable to improving the manner in which recognition of prior learning (RPL) is conducted within the Australian Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector.

8 As part of the background of the invention, the Patent Application describes the requirement within the education and training sector to evaluate the existing skills, knowledge and/or experience of an individual in order to assess suitability for enrolment within a particular training course, or to determine whether the individual has satisfied the requirements to obtain a particular qualification and/or exemption for a particular course of study. The invention is described by reference to RPL within the VET sector but is not necessarily limited to achieving improvement within the RPL system.

9 In order to complete the RPL assessment, the person’s competency is assessed to determine whether he or she is able to meet the requirements, skills, knowledge and/or expectations of a person who has completed the equivalent training course, or who has gained relevant practical experience in the workforce.

10 The Patent Application asserts that there are a number of barriers to access to the RPL processes by individuals within the existing VET system, as follows:

No single point of access to RPL in Australia.

There are currently in excess of 3,500 qualifications and 34,000 units in the Australian VET sector. Consequently, any individual training organisation is only able to offer and assess a very small subset of these.

It is difficult for an individual to identify a particular qualification to which he or she may be entitled under an RPL program with an institutional organisation that is able to perform the required RPL assessment.

The primary business function of Registered Training Organisations (RTOs) and Colleges of Technical and Further Education (TAFEs) is the provision of education and training and not the evaluation of the existing competencies of prospective students. Accordingly, there has been little focus upon “assessment only” pathways compared to the development and provision for effective training programs.

The onus is upon a prospective student to seek out a relevant provider and to negotiate his or her way to recognition via RPL processes.

11 The Patent Application states:

It is accordingly an objective of the present invention to provide an improvement to the existing situation through technological means. In particular, the invention recognises the need for an automated tool that can facilitate the centralised collection of assessment information from individuals, and provide improved access to RPL processes independently of a particular organisation (eg RTO or TAFE) that is chosen to issue a corresponding qualification or Statement of Attainment.

In the description of the summary of the invention in the specification it is stated that:

Embodiments of the invention are advantageously able to automate the process of converting assessable criteria, possibly relating to many thousands or tens of thousands of training courses and units, into a more convenient “question and answer” format, that is able to guide an individual through the information gathering process. The responses of an individual to the automatically-generated questions may be collated and, for example, stored in a database, from where they may be provided (with or without further processing) to a relevant training organisation for the purposes of assessing the individual’s competency relative to the recognised qualification standard.

From the perspective of an individual user, embodiments of the invention are able to provide a single entry point from which they are able to identify and/or select specific relevant qualifications and units, provide information and evidence relevant to existing competencies, and initiate a recognition process, in a manner that is independent of the institution that is ultimately selected to perform the assessment and/or to issue a qualification.

12 In a particularly preferred embodiment, the steps of presenting the automatically-generated questions to the individual and receiving the corresponding set of responses are performed via an automated computer interface such as a web-based interface or a stand-alone computer interface.

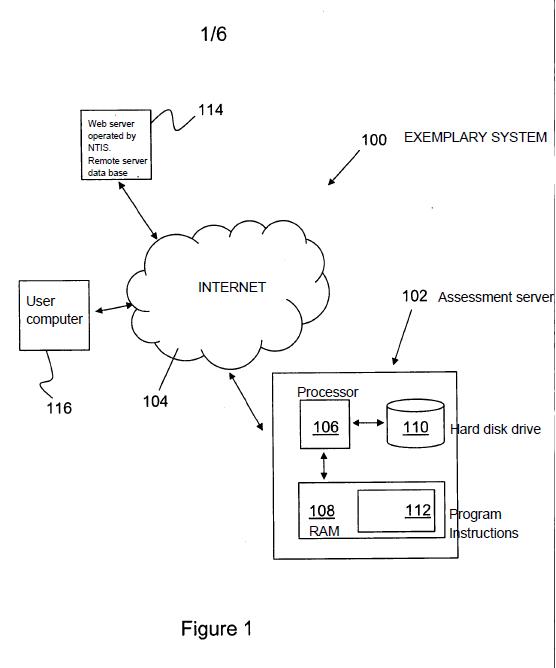

13 A detailed description of the preferred embodiments is provided by reference to a number of figures, for example, Figure 1 (annotated in accordance with the description of the Figures).

14 The system includes a server computer described as an “assessment server”, which is configured to gather information relevant to an assessment of an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard. An example is for use in an RPL process within the Australian VET sector that is connected to the Internet in a conventional manner, in order to enable remote access by users, as well as to provide the server with access to related online resources.

15 The server includes at least one processor, which is associated with random access memory (RAM), used for containing program instructions and transient data related to the operation of the services provided by the assessment server. The memory contains a body of program instructions implementing a method of gathering information relevant to the assessment of a user’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard. The body of program instructions includes instructions for providing a web-based interface to the assessment servers, enabling remote access utilising conventional web browser software.

16 A further storage device, such as a hard disk drive, is used for long-term storage of program components, as well as for storage of data relating to recognised qualification standards, as well as information gathered for users.

17 In the exemplary system there is:

A remote server computer accessible via the Internet containing information relating to recognised qualification standards. This is preferably a web server operated by or on behalf of the Australian National Training Information Services (NTIS), which provides information pertaining to recognised qualification standards registered with the NTIS. They are in the form of Units of Competency associated with a number of assessable criteria.

An assessment server (as described above) able to retrieve information regarding the elements of competency and performance criteria via the Internet from the NTIS server.

User access to the assessment server via the Internet.

18 Nationally accredited Units of Competency registered with the NTIS comprise a number of elements, each of which is associated with a number of performance criteria. The elements of competency and performance criteria are generally outcome-orientated and are said in the specification not to be particularly “user friendly” from the perspective of the individual attempting to navigate his or her own way towards formal recognition of existing competencies. Accordingly, the elements of competency and associated performance criteria are converted into a more user-friendly form: namely, a series of questions designed to gather information relevant to the assessment of competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, that is, the Unit of Competency.

19 Such a step-by-step, form-based implementation, when provided by a computer interface, is commonly known as a “wizard”. It is said to be desirable to automate the process of wizard generation to the greatest extent possible in view of the number of qualifications and units currently registered in the Australian VET sector. The specification states that ‘the manual generation of corresponding wizards is therefore impractical’.

20 A function of the assessment server is to convert the elements of competency and performance criteria into a suitable “question and answer form” such that outcome-orientated elements of competency and performance criteria are converted into corresponding questions for inclusion in the wizard. The examples given in the specification concern converting the element of competency, such as to ‘demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector’, into the question: ‘generally speaking and based upon your prior experience and education, how do you feel you can demonstrate an understanding of the structure and profile of the aged care sector?’. The performance criterion that ‘all work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers’ is converted into the question ‘how can you show evidence that all work reflects an understanding of the key issues facing older people and their carers?’. User responses may include a text-based response and/or supporting documentation (which may consist of electronic text documents, images, audio-visual and/or other multimedia documents), which may be uploaded to the assessment server.

21 Figures and descriptions illustrate the method of generating questions from assessable criteria, namely, elements of competency and performance criteria, according to the preferred embodiment. There are also flow charts, in Figures 2b and 3, illustrating methods of gathering information from an individual using either the questions that have been stored, or alternatively questions generated on demand.

22 In order to understand the claimed invention, it is helpful to set out embodiments of the invention, as set out in the Figures in the specification.

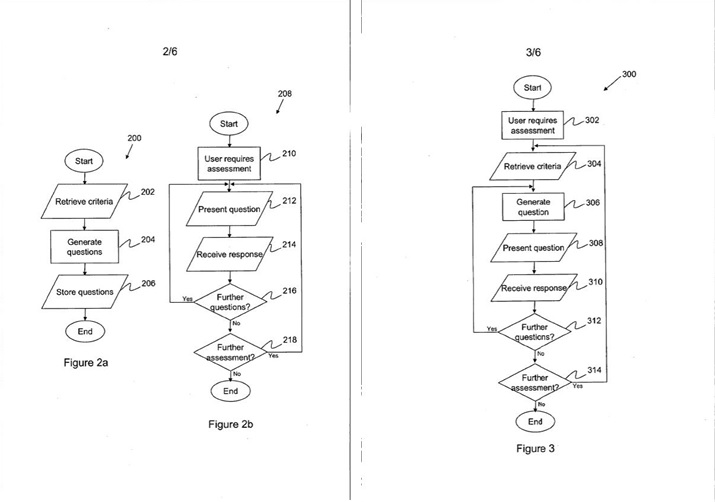

23 The specification explains the different methods encompassed within the claims by reference to the Figures. In Figure 2a, each of the assessable criteria retrieved from the NTIS server is processed to generate a corresponding set of user-friendly questions that may be incorporated into a wizard format. These questions are stored. Thus a complete set of assessable criteria associated with a particular qualification standard is retrieved and processed to generate the corresponding questions in advance of the demand of the user.

24 Figure 2b illustrates the subsequent gathering of information from an individual using the stored questions. The user is presented with a first question and responds. In accordance with the decision step, while there are further questions associated with that Unit of Competency or qualification standard, the steps of presentation of a question and user response are repeated. The user may request further assessment in respect of a different Unit of Competency or may terminate the process.

25 Figure 3 illustrates an alternative method where questions are generated and presented to the user on demand rather than being generated and stored in advance for later presentation.

26 The description of Figure 3 identifies the following steps:

1. The user accesses the assessment server via the Internet from a computer.

2. The user identifies a relevant Unit of Competency.

3. The server generates and presents questions based upon the assessable criteria associated with the Unit of Competency.

4. A question is generated based upon the first retrieved criterion.

5. The question is presented to the user and a response is received.

6. If it is determined that there are further criteria, the steps are repeated until no criteria remain.

7. If the user wishes to provide relevant information, the method provides that further assessable criteria are retrieved, otherwise the process terminates.

8. User responses may be stored by the assessment server within the storage device.

27 It is relevant that the methods of Figures 2a, 2b and 3 represent alternative embodiments of the claimed invention: the questions are stored in advance and presented simultaneously, or presented on demand one at a time. Thus, the presentation of the questions at one time or seriatim is not where the ingenuity of the method lies. The specification does not suggest that it does. Combinations of these two processes are said to be within the scope of the invention.

28 As to the criteria, the NTIS server accessible at the NTIS website provides a search facility for identifying and accessing Units of Competency. The assessment server can then identify and download the assessable criteria associated with any particular Unit of Competency.

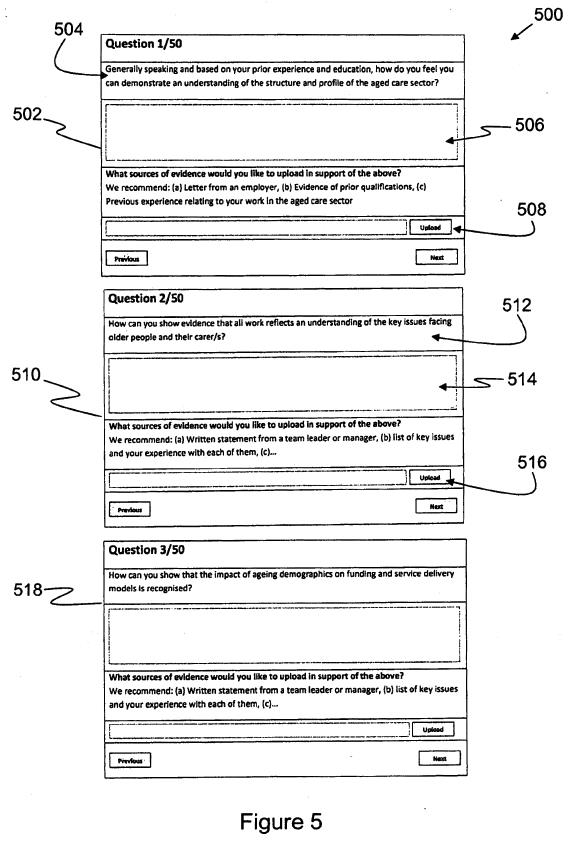

29 Figure 5 illustrates question and response forms of a wizard that may be automatically generated from the assessable criteria:

A first automatically-generated question based upon the element of competency is asked.

A text box is provided into which the user may enter a text-based response.

The wizard form recommends that the user provide evidence supporting the response.

An upload facility is provided.

A second form presents a question based upon the first of the performance criteria.

A text field is provided.

The wizard form recommends providing evidence.

An upload facility is again provided to enable the user to specify documents stored on the local computer to be transferred to the assessment server.

A third wizard form has a similar form.

30 The process of automatically generating a question based upon assessable criteria may include:

applying a question template into which the text of the relevant assessable criteria may be merged. In a simple example, this may be generated from the first element of competency by prepending the text which converts the outcome-orientated statement into a corresponding query such as ‘generally speaking and based on your prior experience and education, how do you feel you can…’;

forming simple questions from the performance criteria by prepending the text ‘how can you show evidence that…’;

forming questions based upon the identification of particular key words or concepts appearing within the individual assessable criteria;

employing additional contextual information in the formulation of questions by, for example, basing the questions upon information available in other documentation such as evidence guides associated with qualifications and Units of Competency.

31 The processing may be entirely computer-implemented or may involve a degree of human expert input. The specification explains this human expert input: for example, questions that have been automatically generated utilising a fully computer-implemented process may subsequently be reviewed and/or amended by a human operator. The specification states that, preferably, the number of questions requiring human intervention is minimised through the use of more sophisticated textual analysis, such as grammar checking techniques.

32 The specification acknowledges that when questions are generated and stored in advance, it is a straightforward matter to replace the stored questions that have been automatically generated with amended questions based upon operator input for later use. It is also possible to account for such “special cases”, even if questions are generated on demand; information relating to any assessable criteria requiring special treatment in order to generate a suitable question may be stored within a storage device. This information may be identified and used to generate a suitable question in each special case. The appropriate template for the generation of any question may be identified on the basis of the specific text of the relevant assessable criterion.

33 It is also stated that the present invention is primarily concerned with the gathering of information relevant to the assessment of an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard and that it is an objective to facilitate improvement in the overall RPL process.

34 Potential, more elaborate, uses are also described, such as the assessment server identifying one or more training organisations that are competent to provide RPL in relation to the units in respect of which the individual user has provided assessment information, and advising the user of those organisations. The assessment server may also be configured to recommend or advise the individual user of one or more relevant training organisations able to provide RPL and training services. It should be noted that these potential developments are not within the scope of the claims.

35 The specification states that, in summary:

[E]mbodiments of the present invention facilitate improvements in existing RPL processes, by enabling the automated generation of a wizard, or similar user interface to perform the administrative work necessary to gather evidence from a prospective candidate which is relevant to any qualification or unit offered across a wide range of training organisations. In various embodiments, the invention facilitates the assessment of the competencies of individuals, the issuing of qualifications, and the proactive recommendation of suitable pathways, including relevant courses of further training, based upon the identified competencies of individual users.

The claims

36 The parties agreed that a consideration of the claims can be limited to the method of claim 1 and the system for gathering evidence in claim 5. Claim 1 is to:

A method of gathering evidence relevant to an assessment of an individual's competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, including the steps of:

a computer retrieving via the Internet from a remotely-located server a plurality of assessable criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard, said criteria including one or more elements of competency, each of which is associated with one or more performance criteria;

the computer processing the plurality of assessable criteria to generate automatically a corresponding plurality of questions relating to the competency of an individual to satisfy each of the elements of competency and performance criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard;

an assessment server presenting the automatically-generated questions via the Internet to a computer of an individual requiring assessment; and

receiving from the individual via said individual's computer a series of responses to the automatically-generated questions, the responses including evidence of the individual's skills, knowledge and/or experience in relation to each of the elements of competency and performance criteria,

wherein at least one said response includes the individual specifying one or more files stored on the individual's computer, which are transferred to the assessment server.

37 In summary, claim 1 involves:

using a computer to retrieve the criteria using the Internet. This involves the user using conventional web-browser software;

the computer processes the criteria to generate corresponding questions relating to the competency of the individual to satisfy the elements of competency and performance criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard;

those questions are presented;

the individual answers the questions and, if he or she chooses to do so, uploads documentation from his or her computer.

38 Claim 5 is to:

A system for gathering evidence relevant to an assessment of an individual's competency relative to a recognised qualification standard, the system including:

at least one server computer having a microprocessor, an associated memory or storage device, and a network interface providing access to the Internet;

the memory or storage device including a data store which contains a plurality of questions relating to the competency of the individual to satisfy each of a plurality of assessable criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard said criteria including one or more elements of competency, each of which is associated with one or more performance criteria, wherein the assessable criteria are retrieved via the Internet from a remotely-located server, and the questions have been automatically-generated by computerised processing of said elements of competency and performance criteria; and

the memory or storage device further including instructions executable by the microprocessor such that the server computer is operable to:

present the questions via the Internet to a computer of an individual user;

receive from the individual user via said [individual’s] computer a series of responses to the questions, the responses including evidence of the individual's skills, knowledge and experience in relation to each of the elements of competency and performance criteria, wherein at least one said response includes the individual specifying one or more files stored on the individual's computer for transfer to the server computer; and

store the responses of the individual user within the associated memory or storage device.

39 In summary, claim 5 is to a system, which involves:

at least one (server) computer with a microprocessor, a memory or storage device and an interface providing access to the Internet;

the memory or storage device including a data store which contains questions relating to the competency of the individual to satisfy the criteria associated with the recognised qualification standard. Each question is associated with performance criteria, which are retrieved via the Internet, and the questions are automatically-generated by computerised processing of competency and performance criteria;

the memory or storage device being operable to present the questions via the Internet to the computer of an individual, to receive from the individual a series of responses to the questions, which includes, if he or she chooses to do so, uploading documentation from his or her computer, and to store the individual’s responses.

The decision of the primary Judge

40 The primary Judge concluded that the invention belongs to the useful arts and not to the fine arts and that it does have utility in practical affairs. His Honour’s conclusion that the subject of the Patent Application produces a useful result is not presently challenged. As his Honour said (at [129]), the claimed invention overcomes difficulties involved in seeking out relevant education providers and enabling RPL. His Honour also concluded (at [130]) that the invention satisfies the “vendible” requirement of the vendible product test as articulated by the High Court in NRDC.

41 At [132], the primary Judge reiterated what he saw as the advantages claimed by the invention. In particular, his Honour noted the fact that the embodiments of the invention automate the process of converting assessable criteria (possibly relating to thousands or tens of thousands of training courses and units) into a more convenient question and answer format that can guide an individual through the information gathering process and store the individual’s responses in a database for the purpose of provision to a relevant training organisation. The primary Judge concluded that (at [133]):

[T]he invention is a ‘product’, in that it does give rise to an artificially created state of affairs … (as articulated by the Courts in NRDC and Grant respectively).

42 In seeking to explain his characterisation of the claimed invention, the primary Judge said (at [139]):

It is important to note that the involvement of the computer in the invention is described in these claims in such a manner that it is inextricably linked with the invention itself.

43 His Honour seemed to accept RPL Central’s submission or characterisation that:

[O]verall, the invention comprises a method and a system including, in practice, programmed computers operating together and employing data communications within a networked environment.

44 The primary Judge relied upon the fact that it is the assessment server, which has been specifically programmed, that retrieves stored information in the host server and that it is a function of the computer to retrieve salient information for further processing. The computer programmed in accordance with the Patent Application further operates to process the retrieved information and to generate data comprising an alternative means of presentation, automatically (at [141]). This alternative means comprises a series of questions which can be presented to the user in an online form. The assessment server presents the form to the user by the user’s computer. At [142], his Honour referred to RPL Central’s submission that each step involves computer-improvised implementation and the transfer and transformation of data.

45 In an analysis that was particularly relevant to the submissions made to the primary Judge, before the decision of the Full Court in Research Affiliates, his Honour considered the methods as including the physical manipulation of data and expressed himself satisfied that each of the steps of the method of claim 1 and of the system defined by claim 5 requires or involves a computer-generated process involving a number of physical effects. Further, his Honour concluded, each step gives rise to a change in state or information in a part of the machine and therefore produces a physical effect, in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation (Grant at [32]). These matters, and his Honour’s reference to more than one artificial state of affairs being created, are accepted by the Commissioner, who submits that that remains insufficient to amount to a patentable invention for the reasons set out in Research Affiliates (at [95]).

46 At [144], the primary Judge said that, in contrast to the patent in Grant, there is clearly a physical effect and an artificial state of affairs. His Honour then turned to the question (at [145]) as to whether the physical effect required by the manner of manufacture analysis must be “significant” and “central” to the purpose or operation of the claimed process or otherwise arises from the combination of steps in a substantial way. His Honour considered (at [146]) the submission by the Commissioner that recognised that ‘the use of a computer facilitates the operation of the claimed method (and makes it faster or more convenient), the computer (or the physical effect involved in its use) is not central to the operation or purpose of the claimed process’. The Commissioner had submitted that the information could be gathered by other means and that the computer is merely a common mechanism to carry out the method in a more convenient way.

47 The primary Judge rejected a submission that NRDC and Grant expressly import a requirement of substantiality or centrality of physical effect. Similarly, his Honour did not agree that the significance of the relationship between the method and the machine determined whether the claimed invention was directed to a proper subject of letters patent (at [147]). That is, his Honour did not accept that ‘any of those decisions articulated a separate or new requirement of substantiality of physical effect’.

48 That is not to say that the primary Judge approached the issue as a matter of form rather than substance, but rather that if, as a matter of substance, the requisite physical effect was present, that was sufficient and there was no separate requirement that it had to affect each and every integer of the claimed invention.

49 The primary Judge considered the submission that, if such a limiting principle does not apply, any method operated on a computer would necessarily fulfil the artificial state of affairs requirement articulated in NRDC and Grant. The Commissioner expressed the concern that if nothing more was involved than the operation of the method on a computer, many previously unpatentable business commercial and financial schemes and plans would become patentable subject matter. The primary Judge rejected that concern, noting that each case must be assessed on its merits (at [149]).

50 At [156], the primary Judge elaborated his thinking on the substantiality requirement with respect to this claimed invention. His Honour noted that the claimed invention expressly incorporated a computer into the method and system claimed and that ‘[t]he computer is a substantial, central or integral part of each claim’ sufficient to fulfil any requirement of substantiality, if it does exist, in Australian law.

51 The primary Judge rejected the Commissioner’s submission that the appropriate way of determining patentability was to ascertain whether the claimed invention could be performed without the use of a computer and, if one were to strip away the computer aspects of claim 1, one would be left with only a method for performing an aspect of the business. The primary Judge said that even if this were true, he did not accept that that was the appropriate way to approach the question of manner of manufacture and that one should not subtract from the invention any aspect of computer implementation and then look to see what remained. His Honour said that this was not consistent with Australian authority and that it failed to give effect to the plain words of the claims of the Patent Application, which clearly prescribed computer implementation or involvement as an essential feature of the invention. His Honour recognised (at [157]) that the Court looks to the “substance” of the claims by reference to what is actually claimed, as necessarily informed by the specification and held (at [158]) that ‘the magnitude of the task performed by the invention (as previously described) and the express terms of the claims themselves mean that the computer is an essential part of the invention claimed, as it enables the method to be performed.’

52 That is, his Honour held that the essentiality of the computer was not a matter of form (included as a nominated essential integer of the claims simply by way of a drafting mechanism) but rather was an essential and integral part of the invention. For similar reasons, his Honour said that he did not consider it relevant that the invention does not involve steps which are ‘foreign to the normal use of computers’. His Honour pointed out that such a requirement is not imposed by any of the authorities which were advanced.

53 The primary Judge directed his attention to the first instance decision in Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2013] FCA 71; 300 ALR 724 (Research Affiliates 300 ALR 724) and, in effect, distinguished that case. The distinguishing features were that, as noted by Emmett J at [66]-[67], ‘the only physical result generated by the method of the claimed invention is a computer file containing the [share] index’ and that the index generated was said to be nothing more than a set of data and accordingly ‘no more a manner of manufacture than a bank balance’. Justice Emmett added that the storage of a share index in a computer’s RAM or a memory device, or the fact that it could be transmitted, was not sufficient to satisfy the requirement of an artificially created state of affairs. The primary Judge noted the distinction drawn by Emmett J between a “mere use” of a computer (which carried with it the writing of information to the computer’s memory) and a specific effect being generated by the computer. The primary Judge distinguished Research Affiliates 300 ALR 724 essentially on that basis, adding that, in the present case, the specification and claims provided significant information about how the invention is to be implemented by means of a computer. His Honour repeated (at [172]) that the computer is integral to the invention as claimed.

The decision of the Delegate

54 The decision of the primary Judge was on appeal from a decision of the Delegate, who found that none of the claims were to a manner of manufacture.

55 The Delegate observed, after a consideration of Grant, that for the invention to be a manner of manufacture:

[I]t must give rise to an artificially created state of affairs in the sense of a concrete, tangible, physical or observable effect. Particularly, what is required is a physical effect in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation.

56 The Delegate acknowledged that a physically observable end result need not be in the sense of a tangible product but may be in the application and operation of a method in a physical device. However, he also observed that the mere presence of a physical effect is not sufficient to confer patentability.

57 Before the Delegate, RPL Central argued that the requirement of manner of manufacture as formulated in CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 (CCOM), being ‘a mode or manner of achieving an end result which is an artificially created state of affairs of utility in the field of economic endeavour’, was satisfied in that (at [47] of the Delegate’s decision):

• the field of economic endeavour is the use of online systems to facilitate the collection of information relevant to performing RPL assessment;

• the end result is the presentation of automatically generated questions in the form of a ‘wizard’, for completion by an RPL candidate via an online interface; and

• the mode or manner of achieving this end result is the retrieval of assessable criteria from a remote server and processing these criteria to generate and store the information required to generate the RPL ‘wizard’ upon request by the candidate, whereby information is collected, transferred and stored for later evaluation.

58 RPL Central also submitted that the claims define a concrete application of information processing involving the retrieval of information from one source, the processing of that information into an alternative form in which it is suitable for presentation to an RPL candidate, the provision of online interface for the presentation of the information to a user, and the collection, transfer and storage of relevant information provided by the user.

59 The opponent before the Delegate argued that the claimed invention was simply a transfer and presentation of known and available information from the remotely located server to an individual’s computer and then the transfer of the information from the individual’s computer back to the assessment server. It submitted that the use of a computer, the Internet and a memory or storage device in the operation of the invention can simply be considered a convenient and conventional manner within which to retrieve, transfer and store information or data. It also submitted that, as in Research Affiliates, LLC [2010] APO 31; 90 IPR 607, the claimed invention involved nothing more than an operation of the business method.

60 The Delegate concluded that the claimed invention defines a method for gathering information where the data retrieval, processing and storage of information appear to have no physical effect other than would arise in the computer with standard software and conventional use. He stated that there is no substantial effect or transformation in generating the questions by concatenating text matters and that, while the Internet and the computer facilitate the operation of the claimed method by retrieving, generating and conveying information, they are not central to the purpose of the claimed invention. He considered that the claimed invention ‘simply monopolises a scheme where the internet and the computer are used for mere convenience for operating the scheme’. He held that the invention defined in claim 1 fell short of having the ‘requisite physical effect in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation’. Accordingly, the Delegate concluded that the claims lacked a manner of manufacture.

Grounds of appeal

61 In summary, the Commissioner identified the following grounds of appeal based on asserted error on the part of the primary Judge:

In finding that the invention claimed in the Patent Application is a patentable invention under s 18(1A)(a) of the Act where it is not “a manner of manufacture” within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (UK).

In applying Grant to find that the invention gave rise to “an artificially created state of affairs” because ‘each of the computer-effected steps of the invention constitutes or gives rise to a change in state or information in a part of a machine, and therefore produces a physical effect in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation’ (at [143]) rather than finding a requirement that the “physical effect” is central to the purpose or operation of the claimed process.

In finding that:

(a) the invention claimed in the Patent Application changed the way in which the machine worked and was an improvement to computer technologies, as the Patent Application involved nothing more than the operation of a computer in a normal way; and

(b) the computer was central to the working of the method and the method could not be worked without it.

In refusing to consider the United States authorities other than for ‘intellectual stimulus and ideas for consideration’ (at [155]) rather than for their persuasive reasoning, in particular, the reasoning in Bilski v Kappos 130 SCt 3218 (2010) and the “disavowal” of State Street Bank & Trust Co v Signature Financial Group 149 F3d 1368 (Fed Cir 1998).

Submissions

The Commissioner

62 The Commissioner relies on the following propositions arising from Research Affiliates:

Mere implementation of an abstract idea or scheme in a well-known machine, a computer or computers, is not sufficient to constitute patentable subject matter.

Merely because there is an artificial effect (here described by the primary Judge as the physical effect, being storage in RAM or in a hard disk, and communication by wire or wifi) is not sufficient.

63 The Commissioner accepts, whether or not the invention involves a manner of manufacture, it is, as explained in Research Affiliates at [107], necessary to understand the claimed invention. It is not a question of the ‘mechanistic application of the criterion of artificiality or physical effect’. The Commissioner points to the distinction applied in Research Affiliates, drawn by the Supreme Court of the United States (per Thomas J) in Alice Corporation Pty Ltd v CLS Bank International 134 SCt 2347 (2014) (Alice Corporation), between the ‘mere implementation of an abstract idea in a computer and the implementation of an abstract idea in a computer to create an improvement in the computer’ (Research Affiliates at [104]). She also points to the Full Court’s adoption of Lourie J’s observation in Bancorp Services LLC v Sun Life Assurance Co of Canada (US) 687 F3d 1266 (Fed Cir 2012) (Bancorp) at 1278 that ‘to salvage an otherwise patent-ineligible process, a computer must be integral to the claimed invention’.

64 In substance, the Commissioner’s submission is that this invention is no more patentable than was the claimed invention in Research Affiliates. That is, the claimed method happens to use a computer to effect the implementation of a scheme.

65 The Commissioner notes the following findings of the primary Judge:

the invention involved a new use of a computer rather than mere implementation;

the invention concerned a method that was ‘tied to the machine’ and was not merely the use of a tool to perform a method that could be performed without the use of a computer;

the involvement of the computer is inextricably linked with the invention itself such that the computer was “integral” to the invention.

66 The Commissioner accepts that those characteristics ‘point toward the invention being patentable subject matter’ but submits that the primary Judge erred in characterising the invention this way.

67 The Commissioner identifies the following as errors of fact on the part of the primary Judge:

The computer is integral to the claimed method and the claimed system was ‘tied’ to the machine.

There was an artificial effect because there was a physical effect, being a conclusion contrary to Grant.

68 The Commissioner submits that, in making those findings of fact and concluding that there was therefore a patentable invention, the primary Judge reversed the findings in NRDC, Grant and Research Affiliates. Further, the mere presence of a physical phenomenon, the fact that the computer is central to the carrying out of the claimed method, that there is a computer-generated process and that there is an artificial state of affairs are not, she submits, sufficient for there to be a manner of manufacture.

69 The Commissioner asserts that there was an error in the primary Judge’s description of the invention involving the retrieval step, being the step that involves collecting information via the Internet and comprises the assessable criteria associated with recognised qualification standards. The Commissioner points to the primary Judge’s description of this step as ‘[a]nother computer, specifically programmed to operate in accordance with the teaching of the Patent [Application], retrieves the stored information by conducting data communications’ and ‘[i]t is therefore a function of the computer, as taught by the Patent [Application], to retrieve salient information for further processing’ (at [140], emphasis added). The Commissioner submits that there is no support in the specification for “specific programming” of the computer using a retrieval step.

70 The Commissioner points out that there were disclosures of:

the assessable criteria available to download from the NTIS server;

the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) for the person operating the assessor computer to type into a standard computer web browser to be taken to the NTIS web page located on the NTIS server;

the NTIS web page providing a search facility where a person could type in search terms to identify Units of Competency where assessable criteria were available to download.

71 The Commissioner says that this process is performed by the assessment server, that is, the computer used in the retrieval step. However, there is no description of specific programming of the assessment server to perform that task. There is no description of specific programming in relation to the retrieval step and no indication that this is part of the invention, or the ingenuity of the inventors. Accordingly, the process is nothing more than routine searches of the Internet by a person using a standard Internet browser. This is in contrast to a computer operating automatically according to specific programming. This distinction is followed in the specification, where the Patent Application drafter uses the term “automatically” (e.g. page 15, claim 1, line 9) when referring to a computer operating according to specific programming in the generation step.

72 As to the “automatic process”, the Commissioner submits that it can be dismissed for the purposes of the invention. The conversion of a statement into a question is simply an example of the type of algorithm or macro used to manipulate or refine data that was referred to in Research Affiliates at [110]. Accordingly, the Commissioner submits, this automatic process is a simple keying of text and the insertion of a question mark, which can be formed by standard word processing or spreadsheet programs working as normal.

73 Although the specification states that ‘more sophisticated templates and text processing may be employed, within the scope of the invention’, there is no suggestion or disclosure in the specification that the inventors have written any such programs, or that they form part of the ingenuity of the scheme.

74 The Commissioner says that the presentation step is “merely” making available standard online forms, populated with the questions generated by means of the Internet as is the response. The Commissioner submits that the method of the Patent Application is a method for the collection of evidence of a person’s skill and knowledge: in truth, a scheme or idea which is not patentable.

75 The Commissioner relies upon a number of signposts said to be identified in Research Affiliates:

whether the claim steps define normal use of computers.

whether the method creates an improvement in the computer.

whether any unusual technical effect is utilised.

whether any part of the innovative or inventive step lies in the computer implementation.

whether the invention is a new use for the computer.

76 The Commissioner submits that the ingenuity of the inventors is in the idea of collecting assessable criteria from many Units of Competency and providing forms to applicants, enabling them to supply evidence of skill and competency. That is, she submits, the invention is a new scheme of carrying out the business of assisting prospective students in using the RPL process, using a computer as a tool with standard software. The specification does not provide further specificity in relation to the computer program. Thus, the computer is a feature of the claim but is not integral to, nor inextricably linked to, the invention.

77 The Commissioner contends that this is a scheme, a method or system for the automated collection of evidence of skills and knowledge, which has nothing to do with the improvement of a computer, although she concedes that there does not have to be a physical improvement in the computer to be patentable. She concedes that the method is done more efficiently by means of a computer but points out that ‘that’s what a computer does’. In the present case, she says, the artificial effects are routine steps of storing something in RAM or a hard disk and communication. It is, she submits, no more than a scheme to facilitate RPL by the automatic collection of evidence of skills and knowledge, using routine computing power and speed. The wizard, the Commissioner says, is just a form-based input of data which has been automated because of the sheer magnitude of the task, which the specification says is impractical to generate manually. She contends that this is also a conventional benefit of a computer.

78 She submits that, to the computer scientist, there is no technical contribution. The contribution is to educational or administrative need. Accepting for the purposes of patentability that the claims are to a new combination of technical elements, the question arises whether the new combination represents a technical contribution. The Commissioner says that there is nothing technical in relation to a computer. Rather the claim is simply a program which, for example, takes criteria and prepends questions. There is, for example, no judgment made by means of the computer. The processing may be entirely computer-implemented or may involve a degree of human expert input, where it may be subsequently reviewed and/or amended by a human operator.

79 The Commissioner describes the substance of the invention in the specification as the use of a computer for the ability to communicate with the NTIS, draw down criteria to the user and receive the user’s response. That is, she says, it is a method of gathering evidence relevant to an assessment of an individual’s competency relative to a recognised qualification standard.

80 The Commissioner characterises the claims as being to a method limited by the results on the devices: a server computer having a microprocessor and associated memory or storage device and a network interface providing access to the Internet, including a data store. It then includes the hard disk of the assessment server, a plurality of questions relating to the competency of the individual to satisfy each of a plurality of assessable criteria, together with the pre-writing of the questions, and stores them such that they are retrieved on demand.

81 The Commissioner emphasises that, while the substance of the invention can be determined by a reading of the whole of the specification, patentability must be assessed by reference to the claimed invention and not by possibilities described in the specification but not claimed. She warns against a situation where a patentee can, by careful drafting, “draft itself” into a manner of manufacture where none is present.

82 When faced with the question whether her submissions mean that no method that utilises a computer is a manner of manufacture, the Commissioner submitted that the test is not whether the method can be carried out with or without a computer and is not whether the computer is or is not integral to the claimed method, but whether in substance the claim is to a mere scheme that is or is not changed by the addition of a computer. She rejected as irrelevant the asserted fact that the magnitude of the task is such that any other means would be commercially impractical, submitting that this did not make a technical contribution. It remained, she contends, a scheme to advise or assist students.

83 The Commissioner does not accept that her submissions amount to an assertion that no programming use of a computer could be patentable, even if the methodology was inventive and the result had utility and commercial benefit. She contends that the programming of a standard computer is simply the ordinary task of a computer and thereby not patentable. Put another way, the Commissioner submits that it is no part of the claimed method that there has been an improvement in computer technology, as to either how the computer operates internally or in the technological output being utilised in some valuable way.

84 The Commissioner points out that the primary Judge’s decision pre-dated Research Affiliates, where the Full Court expanded on the previous decisions of Grant, CCOM and Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 113 FCR 110 (Catuity), being the authorities relied upon before the primary Judge. Accordingly, she submits, his Honour’s reliance on the presence of physical effects, as emphasised in the earlier authorities, is not now justified.

85 The Commissioner distinguished CCOM and International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1991) 33 FCR 218 (IBM 2), as the difference between the implementation of an abstract idea in the computer and the implementation of an abstract idea in the computer to create the improvement in the computer; that is, there needed to be sufficient ‘inventive concept’ to transform an unpatentable abstract idea (or scheme) into a patent eligible application (cf. the US Supreme Court reasoning in Alice Corporation). Further, the Commissioner points out, the speed and power of modern computers make them a fast and efficient tool for businesses and few business processes are performed without the use of a computer. In this way, computers can be said to be essential and integral to, and inextricably linked with, the majority of new business methods. She submits that this alone cannot be sufficient to make otherwise unpatentable business methods proper subject matter.

RPL Central’s submissions

86 RPL Central accepts that, if the claimed invention were to a mere scheme or an abstract idea, it is not patentable and will not be saved simply by an assertion that it should be performed on a computer. However, it submits that an invention is not excluded from patentability because it is a scheme or a business method. In this case, RPL Central contends that this is a scheme or business method that is applied to solve a real problem, namely individuals ‘negotiating their way through a maze’ to obtain access to RPL. This is achieved by an improvement in the effect of the use of the computer and server by applying it to solve a problem in the educational field – a new use, by a new combination that ‘harnesse[s] the power of computers to use them in a way that solves a real problem and no one else has done this before’. That is, says RPL Central, as a matter of construction, the invention is not a mere scheme or abstract idea. The server identifies and downloads the assessable criteria for the user; the user does not himself or herself have to ‘negotiate through the NTIS maze’.

87 RPL Central accepts that it is not sufficient for a patentee merely to recite in the claims a method tied to the computer if, in substance, the invention lies elsewhere in the unpatentable arts. It relies upon the distinction drawn in Research Affiliates (at [113]) between a “mere” use for the computer and method involving a specific effect being generated by the computer, on the one hand; and, on the other, an improvement in the operation of the computer. RPL Central adopts the approach taken by the primary Judge, as explained in Research Affiliates (at [101]), that there is an alignment of the invention with a new use of the computer, in contrast to mere implementation by computer.

88 RPL Central points out that the invention cannot be undertaken without the use of a computer. As such, the computer is integral to the invention, which lies squarely in the operation of the computer. RPL Central notes that the primary Judge, after a detailed analysis of the invention as described in the specification, concluded (at [158]) that the magnitude of the task performed by the invention, as well as the express terms of the claims, meant that the computer was an essential part of the invention claimed, as it enabled the method to be performed. RPL Central says that the absence of steps which are foreign to the normal use of computers does not render the invention unpatentable. Indeed, it points out that, in CCOM (at 291) the Full Court rejected a test of asking whether what was claimed involved anything new and unconventional in computer use. RPL Central observes that, in IBM 2, the Court drew a distinction between something new about the mathematics of the invention and something new in the application of the selected mathematical method to computers.

89 RPL Central rejects the necessity that there be something “foreign” to the normal use of a computer, such that one or more of the steps must require something more than the application of conventional programming techniques to a standard computer system. Rather, it says, it is necessary to concentrate on whether the invention is tied to a computer and whether the computer is an integral or central part of the invention. In any event, RPL Central says, if the method must be foreign to the normal use of a computer, there is no suggestion of a previous implementation of such a method or system before the priority date by the use of standard computer programs or otherwise. Notably, the Delegate declined to find that the claim lacked novelty and there was no contention that the claims lacked an innovative step.

90 RPL Central submits that, as demonstrated in International Business Machines Corporation’s Application [1980] FSR 564, IBM 2 and CCOM, a computer-implemented invention can be patentable. It contends that the test of the existence of a scheme is at too high a level of generality. Rather, it is necessary to examine the invention as described and claimed.

91 RPL Central characterises the invention as:

a method of operating a computer to conduct the information and evidence gathering part of the recognition of prior qualifications,

so that it can be centrally delivered to geographically dispersed users,

to cover the vast number of qualifications and units currently offered in the vocation and training sector.

92 RPL Central points out that all of the embodiments of the invention are “tied squarely” to the operation of the computer and that the method could not be practised without the use of the computer. It describes the advance as being one in computer technology. RPL Central says that the problem overcome by the invention in enabling this method involves an improvement through a technological means, as the primary Judge found at [10]. His Honour concluded that the invention recognised the need for an automated tool to achieve an outcome from the abundance of information and evidence on offer.

93 RPL Central also draws attention to the fact that the specification refers to a body of programming instructions implementing the method of gathering information relevant to the assessment stage and submits that it is not necessary for the Patent Application to include the computer program itself in the specification. There is no present assertion of failure to disclose the best method, or of insufficiency with respect to the ability of a person skilled in the art to program the computer to achieve the specified functions.

94 Again, RPL Central points out that the question is not whether the invention is foreign to the normal use of computers but whether the invention is tied to the computer. RPL Central submits that the ingenuity reached in the combination of steps set out in the claim which combination is, and can only be, implemented on a computer. It is not relevant, says RPL Central, to consider the level of computer programming required and it is beside the point that macros or programmed algorithms may be used. Indeed, it submits, any computer program will invariably consist of algorithms which need to be programmed in order to operate the computer.

95 RPL Central characterises the invention as consisting of a sequence of steps and the configuration of a suitably programmed computer system, putting into effect a new application of hardware and software in the field of education and training. In addition, the output of the claimed method gives rise to a change in state or information in part of the machine and therefore produces a physical effect which occurs in the generation of questions and when users input their response. RPL Central submits that such inventions satisfy the requirement in NRDC and have been held to be patentable in IBM 2, CCOM and Catuity. The method and system that have been devised to provide improvement in existing processes produce an improvement in the operation or effect of the use of a computer (Research Affiliates at [113]); this is not an invention that can exist in the absence of a computer (cf. Research Affiliates). As such, there has been, RPL Central submits, an improvement in what might broadly be called “computer technology” (Research Affiliates at [119]).

Consideration

96 A claimed invention must be examined to ascertain whether it is in substance a scheme or plan or whether it can broadly be described as an improvement in computer technology. The basis for the analysis starts with the fact that a business method, or mere scheme, is not, per se, patentable. The fact that it is a scheme or business method does not exclude it from properly being the subject of letters patent, but it must be more than that. There must be more than an abstract idea; it must involve the creation of an artificial state of affairs where the computer is integral to the invention, rather than a mere tool in which the invention is performed. Where the claimed invention is to a computerised business method, the invention must lie in that computerisation. It is not a patentable invention simply to “put” a business method “into” a computer to implement the business method using the computer for its well- known and understood functions.

97 Is the mere implementation of an abstract idea in a well-known machine sufficient to render patentable subject matter? Is the artificial effect that arises, because information is stored in RAM and there is communication over the Internet or wifi, sufficient? Does any physical effect give rise to a manner of manufacture? Are the mere presence of an artificial effect and economic utility, without more, sufficient to determine manner of manufacture?

98 It is not a question of stating precise guidelines but of deciding, in each case, whether the claimed invention, as a matter of substance not form, is properly the subject of a patent.

99 To reiterate some of the matters discussed in Research Affiliates:

It is necessary to ascertain whether the contribution to the claimed invention is technical in nature. In Aerotel Ltd v Telco Holdings Ltd; Macrossan’s Application [2007] 1 All ER 225, the subject matter was an interactive system whereby questions were asked, the answers incorporated in a draft and, depending on some particular answers, further questions were asked. It was held that, apart from the fact of running a computer program, there was nothing technical about the contribution and the method was for the business of advising upon and creating appropriate company documents.

One consideration is whether the invention solves a “technical” problem within the computer or outside the computer, or whether it results in an improvement in the functioning of the computer, irrespective of the data being processed.

Does the claimed method merely require generic computer implementation?

Is the computer merely the intermediary, configured to carry out the method using a computer readable medium containing program code for performing the method, but adding nothing to the substance of the idea? In Alice Corporation, the method was for exchanging financial obligations in which the computer was used to create records, track multiple transactions and issue simultaneous instructions. The majority in the Supreme Court of the United States concluded that the use of the computer added nothing to the substance of the abstract idea of reducing settlement risk in exchanging financial obligations.

100 Relevantly, the Full Court in Research Affiliates said (at [94]) that the distinction to be drawn was between the employment of an abstract idea or law of nature and the idea or law itself and that there is a distinction between a technological innovation which is patentable and a business innovation which is not. Their Honours repeated an observation from Grant (at [29]) ‘[a] product of a method is something in which a new and useful effect may be observed. For claimed computer programs, the courts looked to the application of the program to produce a practical and useful result, so that more than “intellectual information” was involved.’ A technological innovation is patentable; a business innovation is not, although a business method may be the subject of letters patent. However, ‘[a] method that is in the nature of directions for use does not constitute an invention or a manner of manufacture in the absence of some previously unrecognised property of an aspect of the method’ (Research Affiliates at [95]).

101 The Full Court in Research Affiliates, at [104], drew a distinction ‘between, on the one hand, a method involving components of a computer or machine and an application of an inventive method where part of the invention is the application and operation of the method in a physical device and, on the other, an abstract, intangible situation which is a mere scheme, an abstract idea and mere intellectual information’. Their Honours cited the words of Lourie J of the United States Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit in Bancorp, where his Honour said that ‘[a]t its most basic … a “computer” is “an automatic electronic device for performing mathematical or logical operations”… solving a problem by doing arithmetic as a person would do it by head and hand’. Their Honours emphasised a further comment by Lourie J, that to be patentable, ‘a computer must be integral to the claimed invention, facilitating the process in a way that a person making calculations or computations could not’.

102 In Research Affiliates, looking at the claimed method as a matter of substance, the Full Court concluded that, in that case, the computer was merely the means by which the analyst accessed data to generate an index, that being the work of the analyst rather than a technical generation by the computer. There was no suggestion of the utilisation of an unusual technical effect. The inventors made changes to the computer program to cause the program to gather and process data and perform data manipulations and calculations, including macros to manipulate and refine data. Such use of algorithms was not “foreign” to the normal use of computers.

103 There, the invention described in the specification was directed to the index itself and was a method of implementing a scheme which happens to use a computer to effect that implementation (Research Affiliates at [115]). There was no technical contribution to the invention or artificial effect of the invention by reason of the intervention of the inventors; the ingenuity was in the scheme not in the physical phenomenon in which the effect may be observed and which has the requisite economic utility or artificial effect.

104 It is stated in the specification, and was accepted by the primary Judge, that the method could not be carried out without the use of a computer. This alone cannot render the claimed invention patentable if it involves simply the speed of processing and the creation of information for which computers are routinely used. In those circumstances, the claimed invention is still to the business method itself. A computer-implemented business method can be patentable where the invention lies in the way in which the method is carried out in the computer. This necessitates some ingenuity in the way in which the computer is utilised (Research Affiliates).

105 Care must be taken to consider the circumstances of the claimed invention, beyond the form of words used. In both IBM 2 and CCOM, the invention as claimed was patentable. However, the method in IBM 2 could have been characterised simply to involve “drawing a curve on a computer’; in CCOM, the claimed invention could have been characterised as “to convert a word into Chinese characters”.

106 The Commissioner urges rejection of the concept that the test is whether a person could implement the scheme without a computer or not. The fact that a scheme could not be practically carried out by the user does not, she says, take it out of the category of a “mere” scheme. It is a question of what the computer “brings to the scheme”. RPL Central characterises the invention as an improvement in the effect of the use of a computer by applying it, not merely to gather information but to solve a problem in the educational field. RPL Central says that this represents more than a “mere” scheme and is, indeed, a new use of a computer involving the new use of a computer to ‘negotiate …the RPL maze’.

107 Simply putting a business method or scheme into a computer is not patentable unless there is an invention in the way in which the computer carries out the scheme or method. Is the fact that the scheme cannot practically be implemented without a computer, that is, that the computer is integral to the working of the scheme, sufficient to make it patentable? The answer is not straightforward because this is not a case where the computer simply processes the information entered by the user, for example by using an algorithm, or retrieves information from the Internet in response to a user’s question.

108 The fact that the searching is of 34,000 Units of Competency registered in the Australian VET sector as pieces of information stored in the world wide web does not render the method patentable. Such searching, for example by using Google, is an ordinary use of a computer. The interrogation of retrieved information by the user does not necessarily constitute an invention. On the other hand, the fact that a computer has been programmed to carry out a process does not invalidate an invention because, if that were the case, no computer method, indeed no computer development would be patentable.

109 Turning to the characterisation of the invention of the Patent Application, the key aspect relied upon by RPL Central is the conversion of personalised information into questions, including asking for relevant attachments. The Commissioner says that this is simply an easily programmed conversion of information to a question by prepending relevant words. The computer is, in effect, operating as an intermediary in the user’s quest for an evaluation of his or her competency for a particular course and entitlement to obtain a qualification without participating in that course. However, the computer does not evaluate the user’s input to provide the answer. It is not functioning in the nature of an adviser or an artificial intelligence. Rather, the programming allows for a series of prepared words to be prepended to the user information, to turn the statement into a question. The limited role of the computer in the exchange between the user and the institution is clarified in the specification where it is stated that ‘questions may be presented in a form suitable for “offline” completion, such as a printable electronic document (eg a PDF file), or in hard copy … . Responses may be provided by email, mail or in-person submission’.

110 RPL Central does not claim any invention or ingenuity in any program or operation of a computer, or implementation by a computer to operate the method. Accordingly, the ingenuity of the inventors must be in the steps of the method itself. The method does utilise the speed and processing power and ability of a computer but there is no suggestion that this is other than a standard operation of generic computers with generic software to implement a business method. This is the method of taking the information as to available criteria for Units of Competency and reframing those criteria into questions and presenting them to, and receiving the answers from, the user together with any documents that the user wishes to append. The reframing of the criteria into questions may be outside the generic use of a computer but the idea of presenting questions, by reframing the criteria, is that: an idea. It is not suggested that the implementation of this idea formed part of the invention. Indeed, no instruction as to such programming is provided in the specification other than the idea of turning the performance criteria provided by the NTIS into a question by prepending or otherwise inserting a form of words.

111 The problem may be one of confronting the “maze” of available information concerning the RPL of different Units of Competency in different institutions, but the solution to that problem, to be patentable, must involve more than the utilisation of the well-known search and processing functions of a computer, for example an invention in the way in which the computer is utilised.

112 Recognising that the claims are to a method and system comprising a combination of integers, it is necessary to understand where the inventiveness or ingenuity is said to lie. Turning to the integers of the invention as set out at [36] and [38] and summarised at [37] and [39] above, it is apparent that, other than the integers providing that the computer processes the criteria to generate corresponding questions and presents those questions to the user, the method does not include any steps that are outside the normal use of a computer. It is not suggested that the creation of the plurality of assessable criteria themselves form the basis of the claimed invention. They are present on the NTIS website from which they are retrieved. It is not suggested that the presentation of the questions or the processing of the user’s responses involve ingenuity themselves or that this constitutes the requisite manner of manufacture.

113 We conclude that the claimed invention is to a scheme or a business method that is not properly the subject of letters patent.

114 The consideration of computer implemented methods is one that necessarily requires a consideration of the invention as claimed and as described in the specification. Research Affiliates provided a consideration of the principles to be applied. That decision was not available to the primary Judge or to the Delegate, who reached different conclusions.

115 In D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc [2015] HCA 35; 325 ALR 100, the High Court recently elaborated the principles to be applied to “manner of manufacture”, within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and as discussed in NRDC. We have reached our conclusion that the claims are not to patentable subject matter by applying the established principles as they relate to a computer-implemented business method. In contrast to D’Arcy, this is not a case where the subject matter of a claim lies ‘on the boundaries of existing judicial development’ of the concept of manner of manufacture: cf D’Arcy at [7] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ. Nor is this a case which imports an affirmative application of the Act to a new class of case.

116 As their Honours observed in D’Arcy (at [18]), the question whether a claim is as to patentable subject matter in accordance with the principles developed for the application of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies is answered according to ‘a common law methodology under the rubric of ‘manner of manufacture’, as exemplified by NRDC. In this context, their Honours emphasised (at [20]) that, while satisfaction of an ‘artificially created state of affairs of economic significance’ as stated in NRDC may ‘suffice for a large number of cases in which there are no countervailing considerations’, this terminology is not to be treated as a formula exhaustive of the concept of manner of manufacture, or a formula which alone captures the breadth of the ideas to which effect must be given. Similarly, Gageler and Nettle JJ noted (at [125]) that the holding in NRDC does not mean that an ‘artificial state of affairs’ and ‘economic utility’ are the only relevant considerations in this context. However, the majority and Gageler and Nettle JJ acknowledged the usefulness of such characterisation in appropriate circumstances.