FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fletcher v Nextra Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 52

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Appellant | |

AND: | NEXTRA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 070 924 677) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the costs of the respondent, to be taxed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 263 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | MARK TIMOTHY FLETCHER Appellant |

AND: | NEXTRA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 070 924 677) Respondent |

JUDGES: | MIDDLETON, MCKERRACHER AND DAVIES JJ |

DATE: | 10 APRIL 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 Mr Fletcher appeals from a decision in which it was held that his publication of an article on an internet blog was misleading and deceptive conduct in trade or commerce in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law contained in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL). He was required to remove it. Mr Fletcher is involved in the newsagency industry. The Article published on 27 April 2011 was critical of the contents of a flyer circulated by Nextra Australia Pty Ltd, a competitor of newsXpress Pty Ltd of which Mr Fletcher is a director and 50% shareholder.

2 Mr Fletcher appeals from the primary judgment (Nextra Australia Pty Limited v Fletcher [2014] FCA 399) on the basis that publishing the blog was not conduct in trade or commerce. He also complains that the representations as pleaded by Nextra were not established at trial, that those representations found to have contravened the ACL were not those pleaded by Nextra, and that the statements in the Article were as to matters of opinion honestly held.

3 For reasons expressed below, we have concluded that publication of the Article occurred in trade or commerce, and that at least one, (if not more), of the pleaded representations was correctly found to have been a representation of fact. It was false and thus misleading. It was unnecessary to consider whether there was a reasonable basis for making that representation. There was, however, such a finding by the primary judge.

4 Whether or not publishing the Article occurred in trade or commerce was a central issue. Section 18(1) ACL, which restates s 52(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA), provides:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

BACKGROUND FACTS

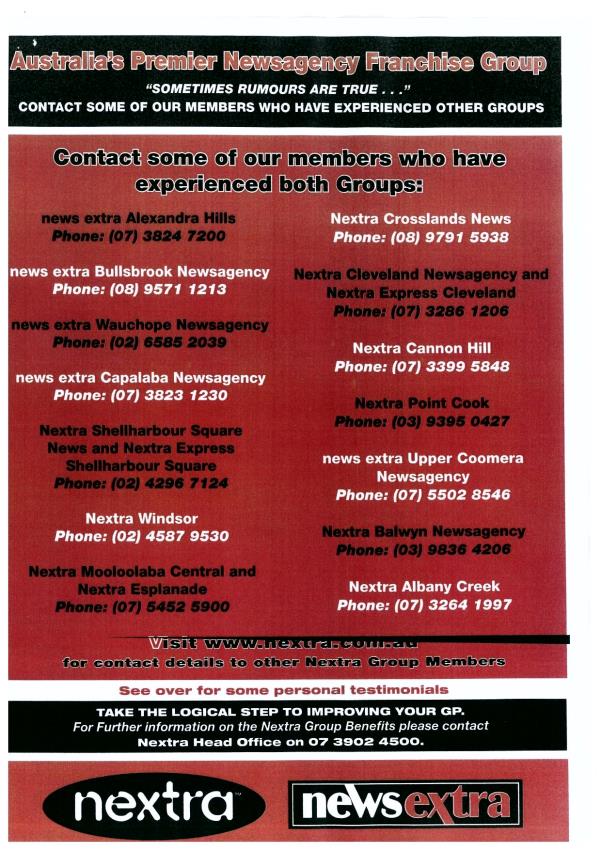

5 Nextra is the franchisor of a national newsagency franchise system known as the Nextra Group. NewsXpress is a competing franchisor in the national newsagency franchise market. In the first few months of 2011, Nextra circulated to newsagents a two page coloured flyer which is reproduced in full in these reasons. The purpose of the Flyer was to encourage non-member newsagents to join the Nextra Group.

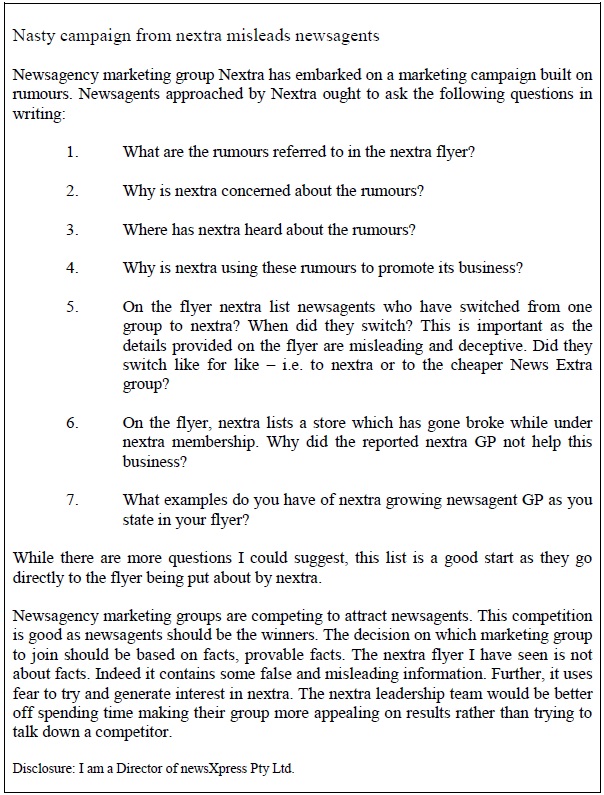

6 Mr Fletcher operates a “blog” on the internet known as the “Australian Newsagency Blog”. The Article published on the Blog on 27 April 2011 was entitled “Nasty campaign from nextra misleads newsagents”. It made reference to the Flyer previously distributed by Nextra. The Blog was intended to be read by newsagents and other persons associated with the newsagency industry throughout Australia. Mr Fletcher indicated that his authorship of the Blog was for the purpose of information and discussion by participants in the industry and interested members of the public. He did not consider his conduct (in writing and posting the Article) to be conduct in trade or commerce.

7 Nextra contended that the Article which criticised the Flyer was misleading or deceptive in a number of respects. Several representations in the Article were relied upon, but one of particular focus at trial and on appeal was a contention by Nextra that Mr Fletcher had alleged in the Article that the Flyer had failed to differentiate between franchisees who had chosen to leave their existing franchise arrangements to switch to Nextra, on the one hand, from those franchisees who had switched to the “cheaper” “news extra” (the Like for Like Representation). Both are part of the Nextra Group. This was clearly a statement of fact. Did the Flyer so differentiate or not?

8 The distinction between Nextra and News Extra was said by Mr Fletcher to be that the services offered to members of the News Extra franchise were substantially more limited than those offered to Nextra franchise members, and the franchise membership fees were correspondingly different to reflect that position. Mr Fletcher pleaded in his defence that newsXpress offered a “full service” to its franchisees. This service, he considered, was of a similar level to that offered by the Nextra franchise, but substantially greater than that offered by the News Extra franchise. Thus, he argued, it was invalid to compare the services offered by News Extra with those offered by newsXpress and/or Nextra as it was not ‘like for like’.

9 It was established at trial that Mr Fletcher did not have, at the time of publishing the Article, a colour copy of the Flyer. As a result, one side of the Flyer containing important material was only partly legible.

10 The Flyer is set out in full on the immediately following pages, followed by Mr Fletcher’s Article commenting on the Nextra Flyer.

THE PRIMARY JUDGMENT

11 In addition to the Like for Like Representation, Nextra pleaded four other representations at trial. The first was that the Article represented that some or all of the newsagents had not in fact switched to Nextra or News Extra. The second was that Mr Fletcher had represented that one of the franchisees listed in the Flyer was insolvent, and such insolvency was caused by the Nextra franchise system. It was also asserted that Mr Fletcher’s Article suggested that the testimonials contained in the Flyer were either false or out of date. Finally, it was asserted that Mr Fletcher’s Article conveyed that the Nextra franchise system did not in fact improve the gross profit of any of the franchisees listed in the Flyer. None of these statements was true, according to Nextra. Each was said to contravene s 18 ACL.

12 The appeal, more so than the trial, was complicated by the superfluous pleading by Nextra (at least insofar as representations of fact were concerned) that there was no reasonable basis to support the representations. That pleading was unnecessary because making a false representation of fact is sufficient to constitute a contravention of s 18 ACL. In Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (at 88) the Full Court said:

[i]f a corporation is alleged to have contravened s 52(1) by making a statement of past or present fact, the corporation’s state of mind is immaterial unless the statement involved the state of the corporation’s mind.

13 Nonetheless, as will be seen, it was quite clear on the information before the Full Court that the parties understood, and ran their cases on the basis, that the representations in the Article were partly or mostly representations of opinion and partly representations of fact.

14 The first question the primary judge considered was whether Mr Fletcher’s actions in posting the Article on his Blog constituted conduct in trade or commerce for the purposes of s 18 ACL. Her Honour referred to Concrete Constructions (NSW) Pty Ltd v Nelson (1990) 169 CLR 594 and cited the passage in the joint decision of Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ (at 602-604).

15 Her Honour noted (at [30]) that the question of whether Mr Fletcher’s conduct in respect of the Article was “in trade or commerce” was complicated by his multiple business interests. Her Honour focussed on the fact that Mr Fletcher was a director and part owner of newsXpress (which operates a separate newsXpress blog). He was also a newsagent in his own business, and owned 100% of Tower Systems International Australia Proprietary Limited which sold point of sale software for newsagents (and also operated a blog). The primary judge noted that Nextra submitted that Mr Fletcher, through the Blog, promoted his commercial interests, (in particular the newsXpress franchise and Tower software), and, in any event, that Mr Fletcher through the Article sought to attack Nextra so as to protect his commercial interests.

16 The primary judge also accepted (at [32]) that self-publication by a person of articles or “thought pieces” relevant to a particular industry would not necessarily constitute conduct in trade or commerce, even where it was clear, for example, that the particular blog permitted ventilation of personal opinions by the publisher on topics in which he or she was interested and was provided for the interest of readers.

17 Speaking of the Blog generally, her Honour formed the view that Mr Fletcher’s motives in posting material on the Blog, as a whole, were mixed. Mr Fletcher appreciated the status and authority that publication of a blog of that nature conferred on him in the newspaper community as an experienced and influential figure and voice in the industry. Her Honour was satisfied that Mr Fletcher, speaking of the Blog generally, had a genuine interest in promoting discussion in the newsagency community on topics of interest to the industry.

18 However, her Honour had no difficulty in being satisfied that Mr Fletcher had also used the Blog to promote his own commercial interests, including that of newsXpress. Her Honour said (at [35]):

However I am also satisfied that Mr Fletcher has not hesitated to use the Blog to promote his own commercial interests (including newsXpress). So, for example:

• He published on the Blog in 2009 an article entitled “How to Choose the Right Marketing Group for your Newsagency”, which promoted the benefits of membership of the newsXpress franchise. No equivalent article promoting the benefits of membership of any other newsagency franchise were brought to my attention.

• On 28 March 2006 he posted an article entitled “Copying is flattering but not great for business” which lauds his own initiatives and those of newsXpress, and is critical of Newspower, as follows:

I’ve been chronicling here the success we have been having in my newsagency with the magazine club card which I which developed and implemented a year and half ago. This was the newsagency channel’s first magazine based loyalty program. It’s been a huge success and I’m aware of close to 100 newsagencies running the promotion. The newXpress group, of which I am a Director, adopted the program in October 2005 and launched it a month later. I just found out that the Newspower marketing group is about to launch its own magazine loyalty program. While I wish newsagents well with the Newspower program, I would have liked to see them offer a point of difference in the loyalty stakes. The more the newsagency marketing groups copy each other the more diluted the offering becomes. If the Newspower offering is similar to what I have created I’ll start looking for new playing fields.

• On 23 March 2006 he posted an article entitled “Getting ‘cut through’ with newsagents” in which he promoted Tower by reference to a hyperlink to Tower and comments including the following:

Suppliers to Australian newsagents often complain at the difficult [sic] in achieving compliance, traction, engagement, cut through – call it what you will. As a newsagent (through my software company) and a newsagent I see both sides of such communication …

Having considered a full week of communication I suggest that suppliers could boost their “cut through” by making communication simpler, provide context for the action requested, don’t over explain and focus on the payoff for the newsagent as a result of compliance.

…

I’m speaking from personal experience here. We achieve rapid compliance across 1,100 newsagents with software updates by following the newsagent communications guidelines noted above …

• On 13 March 2007 he posted an article entitled “Confusing newsagency brands” in which he was “particularly suspicious” of Nextra’s choice of “Nextra express” as a brand name:

as it is very close in name to newsXpress of which I am a Director and shareholder. I would have preferred the Nextra experts demonstrate their skill by coming up with a more unique name.

For the record, newsXpress has nothing to do with Nextra express or indeed any of the other groups. Our stores are called newsXpress and nothing else.

• On 31 January 2008 he posted an article entitled “The team behind newsXpress” in which he praised the strategies, commercial terms, and resources provided by newsXpress to its members, in terms including the following:

I’ve owned my newsagency at Forest Hill in Victoria since February 1996 and over the twelve years have been independent, with Newspower and with Nextra – before joining newsXpress in mid-2005. What I looked for in a group was business building strategies as well as excellent commercial terms. While I am biased about newsXpress, since I’m now a shareholder, my relationship with this brand has been the best for my business.

While any of the marketing groups can negotiate brand based deals, it’s the team behind the brand which drives the point of difference. Below is a photo of the full-time team behind newsXpress. From the national merchandise team to the in-store Business development Managers, this team represents an exceptional resource for my business and the businesses of all newsXpress members.

As with any of the marketing groups, newsXpress is not for everyone. It’s for entrepreneurial newsagents who want to redefine their newsagency and fish for new customers and a build a more valuable shopping basket. Chasing above average growth is hard work and not for everyone. But, then, good rewards do take hard work.

I’m glad to have good relationships with many Nextra and Newspower newsagents. Those groups, too, are not for everyone. I am sure their members would be equally complimentary of them.

Key in assessing a newsagency marketing group is to look at its goals for members and the people who will help you achieve those goals. Finding the right group backed by the right people can make your newsagency a truly valuable investment. The team behind newsXpress is a good mixture of hands-on newsagency experience as well as experience from outside our channel which benefits the brand.

The days of the independent newsagent are coming to an end. Without a well-managed brand behind your business it is easy to get lost in the rush to lure new customers.

Disclosure: I am a shareholder in and Director of newsXpress Pty Ltd

• On 31 January 2010 he posted an article entitled “Newsagency casual vacancy” which read as follows:

We are looking for someone to join our newsXpress Forest Hill (VIC) store on a casual basis. If you know anyone please have them email me.

• In the Blog he made posts referring to:

o “our aggressive magazine promotion strategies” and “Our sales rate bounces between 70% and 90% with the average of 80%”, where “our sales” referred to newsXpress (Blog posting of 25 November 2005, transcript p 228 l 25);

o the newXpress program as “a killer magazine loyalty program in our store and which is driving well above average sales growth” (Blog posting of 16 December 2005).

19 The primary judge appeared to accept (at [36]) that Mr Fletcher’s Blog attracted a high amount of traffic and that he also received modest advertising revenue from publication of the Blog. Her Honour concluded (at [37]) that the Article was an example of where Mr Fletcher had used the Blog for commercial purposes to promote newsXpress and his business interests in Tower, a supplier to newsagents. At [38] her Honour concluded:

The posting of the Article by Mr Fletcher was not conduct divorced from his relevant actual or potential trading or commercial relationships, as envisaged in Concrete Constructions. While Mr Fletcher did not purport to post the Blog on behalf of NewsXpress, or the newsXpress franchise, it is clear from perusing the Article that he did so to defend newsXpress from what he saw as potential poaching of franchisees by Nextra. This conduct was more than merely being “in relation to” trade or commerce. I am satisfied that the posting of the Article on the Blog was conduct in trade or commerce within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL.

20 Her Honour then went on to consider the class of consumers likely to be misled or deceived by Mr Fletcher’s conduct if the representations were misleading or deceptive. There is no specific appeal point arising from her conclusions. On that topic her Honour said (at [40]), after citing Gibbs CJ in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191, (at [9]) that she was satisfied that the class of consumers who could be misled were members of the newsagency community, and that:

[c]ritically, the class of consumers is not confined to the limited group of newsagents who received the Flyer in the mail and who could informatively compare the contents of the Flyer with the questions and comments posed in the Article.

21 The primary judge continued on to note (at [41]) that the class was broader than “newsagents who are sufficiently inclined to read the Blog” as the Blog was publicly and freely available to anyone with an interest in accessing it, and was particularly directed at the newsagent community. Her Honour said there was no evidence before her to suggest that “newsagents” should be so narrowed.

22 Her Honour then considered whether the Article conveyed the imputations claimed by Nextra.

23 Her Honour accepted (at [45]) that Mr Fletcher admitted that the Article represented that the Flyer contained material which Nextra knew to be false and that the Flyer was intended to or had the effect of creating a sense of fear in the reader. This was clear, as the Article said:

The nextra flyer I have seen is not about facts. Indeed it contains some false and misleading information. Further, it uses fear to try and generate interest in nextra.

24 On the topic of newsagents switching to either Nextra or News Express in relation to the Like for Like Representation, her Honour also cited (at [49]) the contents of the Article when it stated:

On the flyer nextra list [sic] newsagents who have switched from one group to nextra? When did they switch? This is important as the details provided on the flyer are misleading and deceptive.

(emphasis added).

25 The primary judge reached the view (at [51] and [52]) that the Like for Like Representation was substantiated because Mr Fletcher’s Article did suggest that the Flyer had not differentiated between the Nextra franchise and the News Extra franchise. Her Honour noted (at [80]) that much was made at the hearing as to whether the newsagencies as identified in the Flyer had transferred from membership of equivalent franchises to either Nextra or News Extra, namely, the Like for Like Representation. In dealing with this, her Honour found (at [81]) that Mr Fletcher’s Article was misleading or deceptive because, although merely asking whether franchisees had exchanged “like for like” franchises was a reasonable question, the issue was that Mr Fletcher went further in the Article and suggested that the Flyer did not identify whether franchisees had switched to Nextra as opposed to News Extra. Her Honour said:

… The flyer clearly does do this. Persons reading the flyer can identify the Nextra brand under which the relevant newsagencies are operating and draw conclusions from that information. So, for example, it would be open to a newsagent reading the Flyer, identifying that Crosslands newsagency had switched from another newsagency franchise to the comparatively “no frills” News Extra brand (as distinct from Nextra), to form the view that Crosslands newsagency had improved its profits because of the lower fees associated with News Extra compared, for example, with more expensive franchise branding. To the extent that the Article imputes that Nextra, in the Flyer, has not disclosed whether newsagencies had switched to Nextra or News Extra, the Article is misleading or deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL.

26 The primary judge also considered the other claimed representations, such as, relevantly, whether or not the testimonials given in the Flyer were genuine, and whether or not the Nextra franchise system improved the gross profit of any of the franchisees listed in the Flyer. The primary judge concluded (at [102]) that the suggestion in the Article that the Nextra franchise system did not improve gross profit would lead persons to whom the Article was targeted into error, and Mr Fletcher had no reasonable grounds upon which to base this representation, particularly in light of the testimonials appearing in the Flyer. Her Honour was not satisfied that the insolvency of Nextra Windsor provided any basis for the representation contained in the Article.

27 Injunctive relief was granted effectively requiring Mr Fletcher to remove the Article and to not repeat such representations.

GROUNDS OF APPEAL

28 Against that background, the main and first issue on the appeal was whether the publication of the Article was conduct in trade or commerce.

29 It was supported by four other grounds of appeal in the amended notice of appeal in these terms:

2. The primary judge erred in finding that the Article carried the following representations:

a. In the Flyer (as defined in the Reasons at [7]), Nextra distributed material it knew to be false, and had intended creating a sense of fear in the reader: Reasons, [45];

b. In the Flyer, Nextra falsely listed franchisees that had not switched to Nextra from another group: Reasons, [50];

c. Nextra had disseminated false information because the Flyer failed to differentiate between franchisees who had switched to Nextra as opposed to those who had switched to NewsExtra: Reasons, [52];

d. The testimonials in the Flyer were false or out of date: Reasons, [62]; and

e. The Nextra franchise system did not improve the gross profit of any of the franchisees listed in the Flyer: Reasons, [65].

3. The primary judge furthermore erred in making such findings referred to in paragraph 2 herein in circumstances where:

a. [Nextra’s] Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC) did not plead the making of such representations set out in sub-paragraphs 2 (a), (b) or (c) above;

b. [Nextra] did not make submissions that such representations set out in sub-paragraphs 2 (a), (b), or (c) above were carried by the Article; and

c. [Nextra] pleaded in the FASOC the making of different and other representations by [Mr Fletcher].

4. The primary judge erred in failing to consider whether the statements contained in the Article were as to matters of opinion of [Mr Fletcher], which were honestly held.

5. The primary judge ought to have held that the statements contained in the Article were as to matters of opinion of [Mr Fletcher], which were honestly held, and as a consequence there was no contravention of s. 18 [ACL].

Ground 1 - whether conduct was in trade or commerce

30 The High Court in Concrete Constructions (at 602-604) examined the difficulty of answering the question of whether particular conduct is “in trade or commerce” in some circumstances, and adopted a restrictive approach to the expression “trade or commerce”, saying:

It is well established that the words “trade” and “commerce”, when used in the context of s. 51(i) of the Constitution, are not terms of art but are terms of common knowledge of the widest import. The same may be said of those words as used in s. 52(1) of the Act. Indeed, in the light of the provisions of s. 6(2) of the Act which give an extended operation to s. 52 and which clearly use the words “trade” and “commerce” in the sense which the words bear in s. 51(i) of the Constitution, it would be difficult to maintain that those words were used in s. 52 with some different meaning. The real problem involved in the construction of s. 52 of the Act does not, however, spring from the use of the words “trade or commerce”. It arises from the requirement that the conduct to which the section refers be “in” trade or commerce. Plainly enough, what is encompassed in the plenary grant of legislative power “with respect to ... Trade and commerce” in s. 51(i) of the Constitution is not of assistance on the question of the effect of the word “in” as part of the requirement that the conduct proscribed by s. 52(1) of the Act be “in trade or commerce”.

The phrase “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 has a restrictive operation. It qualifies the prohibition against engaging in conduct of the specified kind. As a matter of language, a prohibition against engaging in conduct “in trade or commerce” can be construed as encompassing conduct in the course of the myriad of activities which are not, of their nature, of a trading or commercial character but which are undertaken in the course of, or as incidental to, the carrying on of an overall trading or commercial business. If the words “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 are construed in that sense, the provisions of the section would extend, for example, to a case where the misleading or deceptive conduct was a failure by a driver to give the correct handsignal when driving a truck in the course of a corporation’s haulage business. It would also extend to a case, such as the present, where the alleged misleading or deceptive conduct consisted of the giving of inaccurate information by one employee to another in the course of carrying on the building activities of a commercial builder. Alternatively, the reference to conduct “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 can be construed as referring only to conduct which is itself an aspect or element of activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or commercial character. So construed, to borrow and adapt words used by Dixon J. in a different context in Bank of NSW v The Commonwealth, the words “in trade or commerce” refer to “the central conception” of trade or commerce and not to the “immense field of activities” in which corporations may engage in the course of, or for the purposes of, carrying on some overall trading or commercial business.

As a matter of mere language, the arguments favouring and militating against these alternative constructions of s. 52 are fairly evenly balanced…. Nonetheless, when the section is read in the context provided by other features of the Act, which is “An Act relating to certain Trade Practices”, the narrower (i.e. the second) of the alternative constructions of the requirement “in trade or commerce” is the preferable one… [T]he section was not intended to impose, by a side-wind, an overlay of Commonwealth law upon every field of legislative control into which a corporation might stray for the purposes of, or in connection with, carrying on its trading or commercial activities. What the section is concerned with is the conduct of a corporation towards persons, be they consumers or not, with whom it (or those whose interests it represents or is seeking to promote) has or may have dealings in the course of those activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or commercial character. Such conduct includes, of course, promotional activities in relation to, or for the purposes of, the supply of goods or services to actual or potential consumers, be they identified persons or merely an unidentifiable section of the public. In some areas, the dividing line between what is and what is not conduct “in trade or commerce” may be less clear and may require the identification of what imports a trading or commercial character to an activity which is not, without more, of that character. …

(emphasis added) (footnotes omitted)

31 It has been observed that the High Court made a deliberate choice in Concrete Constructions between a wide and narrow view of the expression “in trade or commerce” in s 52 and chose the narrow view: see Robin Pty Ltd v Canberra International Airport Pty Ltd (1999) 179 ALR 449 per Gyles J (at [44]). As such “in trade or commerce” would have a restrictive operation and confine the effect of the provision to conduct which “is itself an aspect or element of activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or a commercial character”: Concrete Constructions (at 603). In Concrete Constructions, focus was placed upon “the central conception” of trade or commerce and not the “immense field of activities” in which corporations may engage in the course of, or for the purposes of, carrying on some overall trading or commercial business. As Yates J noted in Toben v Jones (2012) 298 ALR 203 (at [40]) and the authorities there cited, conduct “in relation to” or “in connection with” trade or commerce is not sufficient to engage the provision.

32 Mr Fletcher contends that typically, editorialising in a trade publication would not be regarded as conduct in trade or commerce. Consistently with this, he says the content of the Article is not such as to amount to “promotional activities in relation to, or for the purposes of, the supply of goods or services to actual or potential consumers”, being the test flowing from Concrete Constructions. So, for example, Mr Fletcher contends that participation in industry related activities, such as the giving of public lectures, would generally not be regarded as falling within the scope of s 18 ACL, relying on Fasold v Roberts (1997) 70 FCR 489 per Sackville J (at 550).

33 Seafolly Pty Ltd v Madden (2012) 297 ALR 337 (at first instance) was relied upon at trial. The Full Court delivered its judgment on appeal in Madden v Seafolly Pty Ltd (2014) 313 ALR 1 after the primary judge in the first instance case reserved her Honour’s decision. At first instance, Tracey J had found that a swimwear designer’s publication on her personal Facebook page of false allegations that a trade competitor had copied her designs was conduct in trade or commerce for the purposes of s 18 ACL because she had alleged that Seafolly had engaged in conduct which was “to the detriment of her own business”: Madden v Seafolly per Rares and Robertson JJ (at [97]).

34 On appeal, Marshall J agreed (at [9]) with the conclusion of Tracey J and noted that the statements were made “in such context and in such circumstances as to render them statements having a commercial character”. Justices Rares and Robertson said (at [98]):

[w]e would add to the last point that the evidence showed that a substantial number of those who made comments on the personal Facebook page were in the fashion industry. Ms Madden posted comments on her personal site using both her own name and the name “White Sands Swimwear Australia” responding to the postings of her Facebook “friends” or, perhaps more accurately, correspondents. For example, she wrote on her personal page under the White Sands name: “Lucy and Holly!!! These are the rip offs Seafolly did! Jeeze, you girls. We have them in Black, in store now:)”. Taking these matters in combination it should not be concluded, in our opinion, that any of the Facebook statements were of a private character and in our opinion there was no error in the conclusion of the primary judge that the statements had a trading or commercial character. ...

35 Mr Fletcher argues that in contrast to Ms Madden, he had a legitimate interest in challenging the content of the Flyer which was wholly separate from his own business interests. According to Mr Fletcher, he had developed a reputation as an authoritative commentator on newsagency issues in Australia and was regarded as an “experienced and influential figure and voice in the industry”. The primary judge accepted (at [34]) that Mr Fletcher had a “genuine interest and aim in promoting discussion in the newspaper community on topics of interest to newsagents, and that the Blog [was] a key element in achieving that objective”. But that was only part of the primary judge’s analysis.

36 One question for consideration is whether the characterisation of the conduct in publishing the Article is, in the circumstances of this case, coloured by mixed purposes, as found by the primary judge, in relation to publication of the Blog as a whole. In that regard, Mr Fletcher argues that the primary judge erred by relying on six posts Mr Fletcher published on the Blog between March 2006 and January 2010 in which he discussed his own commercial interests. Mr Fletcher argues that the six posts referred to were not part of the impugned conduct and were irrelevant to the assessment of whether publishing the Article was in trade or commerce. There is a difficulty with this argument. On the one hand, Mr Fletcher relies upon broader, less commercial interests evident from his conduct in publishing the Blog as a whole, yet on the other hand, denies that regard may be had to the commercial elements identified by the primary judge. It is difficult to see that he can have this argument both ways.

37 Mr Fletcher also argues that the primary judge’s finding (at [38]) that “it is clear from perusing the Article that [Mr Fletcher posted it] to defend [newsXpress] from what he saw as potential poaching of franchisees by Nextra …” was a finding unsupported by the evidence. In this regard, Mr Fletcher relies upon his evidence about the Blog in a general sense, which he says is not operated as a commercial service, but as a “forum for discussion, information and debate concerning newsagency issues”. Mr Fletcher argues that even if his reasons for posting the Article included the protection of his own commercial interests (which he says is unsupported by the evidence) this is insufficient to support a finding that the conduct was “in trade or commerce”. He relies on Village Building Co Ltd v Canberra International Airport Pty Ltd (2004) 139 FCR 330 (at [59]) per French J (as his Honour then was), Sackville and Conti JJ where their Honours said that “[t]he fact that conduct has the purpose or effect (or both) of maintaining or protecting a business is not, of itself, enough to ensure that the conduct is in trade or commerce”.

38 Further, Mr Fletcher complains that her Honour’s analogy with Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Cooper (2005) 150 FCR 1 was inappropriate because Mr Fletcher’s Article was “part of an industry publication and to be distinguished from a publication directed solely to his commercial interests”. It is said that in the publication of the relevant representations, Mr Fletcher was not carrying on a business, and the primary judge’s conclusion (at [38]) that the posting of the Article “was not conduct divorced from his relevant actual or potential trading or commercial relationships” was a much wider test than that specified by the High Court in Concrete Constructions.

39 In considering Mr Fletcher’s arguments it is helpful to recall how different the facts in Concrete Construction were from the facts now under consideration. In Concrete Constructions, Mr Nelson had been injured from a fall after a co-employee misinformed him about the secure nature of a grate covering an air-conditioning shaft. (The advantage in suing under, what was then, s 52 TPA was that a damages award under the TPA would not be limited by the limitation of damages imposed by Workers’ Compensation legislation in New South Wales.) As the High Court noted (at 604), s 52 was not intended to impose by way of a “side-wind” (an expression used by Brennan J as his Honour then was, in Parkdale) an overlay of Commonwealth law upon every field of legislative control into which a corporation might stray for the purposes of, or in connection with, carrying on its trading or commercial activities. As the plurality (Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ) noted (at 604), in some areas, the dividing line between what is and what is not conduct "in trade or commerce" may be less clear and may require the identification of what imports a trading or commercial character to an activity which is not, without more, of that character. Toohey J (at [614]) particularly emphasised that the conduct was required to be “in trade and commerce” not “in connection with” or “in relation to” trade and commerce. The plurality also emphasised in Concrete Constructions that conduct towards persons, whether they be consumers or not, including promotional activities in relation to, or for the purposes of, the supply of goods or services to actual or potential consumers, will usually be conduct in trade or commerce.

40 The position of those delivering public lectures, utterances, publications or articles presents a range of options. At one end of the scale, a communication may be similar to that in Fasold. In that case there was no commercial relationship between the lecturer and the organisation which arranged the lectures; the lecturer received no remuneration for his lectures and was not motivated by any desire to promote any business activities. Rather, he wished simply to disseminate his own views on a biblical topic. (The case concerned the availability of evidence supporting the old-testament story in relation to Noah’s Ark.) At the other end of the scale, a communication may include more immediate and direct business interests, such as the communication by Ms Madden attempting to dissuade her customers from being attracted to her competitor, Seafolly.

41 In Fasold, Sackville J summarised (at 531) the test formulated by the High Court in Concrete Constructions. His Honour observed that a person engages in trade or commerce if he or she publicly makes presentations to advance his or her own commercial interests or of trading entities represented by the presentor. That may be so even if that person does not engage in trade or commerce himself or herself, but makes public statements with a view to persuading persons to invest in a particular trading corporation.

42 Sackville J expressed a concern about the care to be exercised before making orders restraining statements made in the course of public discussion on issues regarded by many people as being important to their religious or ideological beliefs, at least where the motivation for making such statements was not primarily commercial in character. His Honour said (at 550):

[m]oreover, in my view, considerable care must be exercised before making orders restraining statements made in the course of public discussion on issues regarded by many people as important to their religious or ideological beliefs, at least where the motivation for making such statements is not primarily commercial in character. Unless caution is exercised, there is a serious risk that the courts will be used as the means of suppressing debate and discussion on issues of general interest to the community. It is no answer to the concern I have identified that any orders made by the Court will restrain only representations that have been shown to be false. The very task of having to justify impugned representations may deter those with limited resources (both financial and emotional) from engaging in discussion of matters of wide community interest. If the views they put forward are ill-informed or plain wrong, a democratic society offers ample opportunity to rebut those views. As the publicity preceding this case (of which there was evidence) demonstrates, there are means available to counter what are said to be misrepresentations or errors made in public presentations on issues of general interest, without invoking the TP Act or the Fair Trading Acts.

43 On appeal in Fasold (Plimer v Roberts (1997) 80 FCR 303), the Full Court took the same view, emphasising the need for open, intellectual and religious debate, even if carried on through commercial avenues.

44 Of course, the subject matter and purpose of the lecture in Fasold could not be further removed from commercial content in the case at hand.

45 As noted by the Court in Village Building, public advocacy regarding legislative changes as to taxation or tariff laws, or even opposition to a land resumption would be unlikely to constitute conduct in trade or commerce. On the other hand, it has been accepted that even though a representation is not made as part of the trade or commerce of the actual representor, it will be in trade or commerce if it is made in the trade of the representee corporation: Houghton v Arms (2006) 225 CLR 553; Concrete Constructions per Toohey J.

46 To evaluate the character of the conduct in the current case, it is necessary to view the key elements collectively, rather than one by one. Some of the key facts on which the primary judge relied in reaching a conclusion that the publication of the Article by Mr Fletcher constituted conduct in trade or commerce include the following findings of fact:

(a) newsXpress was the franchisor of a newsagency franchise in competition with Nextra;

(b) Mr Fletcher was a director and part-owner of newsXpress;

(c) Mr Fletcher owned 100% of Tower, which sells point of sale software for newsagents;

(d) Mr Fletcher appreciated the status and authority that the publication of the Blog of this nature conferred on him in the newsagency community;

(e) Mr Fletcher had not previously hesitated to use the Blog to promote his own commercial interests;

(f) the Article is an example of Mr Fletcher using the Blog for commercial purposes, namely, to promote newsXpress and his business interests in Tower; and

(g) the posting of the Article was for the purpose of defending newsXpress from what he saw as potential poaching of franchisees by Nextra.

47 Mr Fletcher challenges the last factual finding, which he says is unsupported by the evidence. However, this contention is based simply on the fact that Mr Fletcher denied the primary judge’s finding in relation to the purpose of the Article. There is no challenge in the grounds of appeal to the factual finding. This finding of fact was a vital link in determining the question of whether or not the conduct was in trade or commerce. The purpose of the publication is a matter which is readily capable of inference from all of the surrounding facts, including the particular content of the publication itself, not least of which is the disclosure at the foot of the Article that Mr Fletcher is a director of newsXpress. This disclosure, taken in context, while commendably frank on the part of Mr Fletcher, makes clear that the attack on the Nextra Flyer should not be regarded as emanating from someone with an independent objective viewpoint, but rather, from a competitor in the same industry who was concerned about his own and other potential franchisees being misled by false statements made by Nextra. The context of the Article is not far removed from that of conventional comparative advertising which involves a direct representation in the form of an assertion as to some inadequacy of a competitor’s product. It is has never been doubted that such advertising is conduct in trade or commerce. As with the Article in question, there is nothing at all wrong with comparative advertising, as long as any facts conveyed are accurate.

48 The conclusion reached by the primary judge that the posting of the Article was for the purpose of defending newsXpress from what Mr Fletcher saw as the potential poaching of franchisees by Nextra necessarily involved rejecting Mr Fletcher’s contention that the Blog was only published for altruistic reasons.

49 The strength of the language used in Mr Fletcher’s Article in referring to false and misleading statements in the Nextra Flyer is not the sort of content that one would generally expect to hear in a “public lecture”, which was the analogy contended for by Mr Fletcher. Rather, the primary judge properly considered the facts in Universal Music Australia represented a closer analogue to Mr Fletcher’s use of the Blog, particularly the publication of this Article.

50 As to the complaint concerning reliance by the primary judge on previous commercial usage of the Blog, while the context of the Blog as a whole is not entirely irrelevant, analysis must centre on the particular conduct pleaded, namely, the publication of the Article itself. If that were not so, a party adversely affected by conduct breaching s 18 ACL would be unprotected simply because the particular form of conduct was preceded on other occasions by non-contravening conduct. Such an outcome could not reflect the statutory purpose of s 18 ACL. However, while it may be a distraction to examine the use of the Blog as a whole in a general sense rather than the Article’s content specifically, this issue arose largely because of the defence conducted by Mr Fletcher to the effect that the Blog was wholly for altruistic purposes as a forum for discussion, information and debate, and that it was not for the promotion of his commercial interests. As that point was raised, it was entirely open to Nextra to challenge this contention by reference to the other posts on the Blog. Whilst the real issue is the publication of the Article itself, once Mr Fletcher had raised this ground, not only was it proper for it to be challenged, but it was entirely appropriate for the primary judge to rely upon the other instances of commercial self-promotion contained in the Blog.

51 Mr Fletcher is not at all assisted by the Full Court decision in Madden v Seafolly. The primary judge did not have the benefit of the Full Court’s reasons in Madden v Seafolly at the time of argument. It is clear, however, that the conclusion in Madden v Seafolly on appeal supports the decision under appeal. In Madden v Seafolly, the statements in issue were made on Ms Madden’s personal Facebook page as well as in the Facebook page of her business “Whitesands” and in emails to various media outlets. The Full Court found (at [97]-[98]) that the statements published on her personal Facebook pages were in trade or commerce and upheld the findings of the primary judge at first instance (at [83]), which read as follows:

…Ms Madden was the principal of Whitesands, a trade competitor of Seafolly. Her statements related to the manner in which Seafolly conducted its business. She alleged that Seafolly had engaged in conduct which was improper to the detriment of her own business. She thereby sought to influence the attitude of customers and potential customers of Seafolly. …

52 As noted above (at [34]) the Full Court added “… [w]e would add to the last point that the evidence showed that a substantial number of those who made comments on the personal Facebook page were in the fashion industry.” Aside from the relevant context being the newsagency industry rather than the fashion industry, the relevant facts under consideration in this appeal are very similar. Specifically, Mr Fletcher was a director and part-owner of newsXpress, a competitor of Nextra. NewsXpress and Nextra were two major competitors in the Australian newsagency franchising business. The statements related to the manner in which Nextra conducted its business. Mr Fletcher alleged that Nextra had engaged in conduct which was improper and to the detriment of other newspaper franchises, including his own. He thereby sought to influence the existing and potential franchisees of Nextra. The readers of his Blog were members of the newsagency industry. Both in Seafolly and in the case of Mr Fletcher each of the parties had a commercial interest in attacking the competitor. This case has much in common with Seafolly.

53 While Mr Fletcher relies on Village Building, the present circumstances are distinctly removed from the facts in issue in that case. In Village Building, the operator of the Canberra Airport had published forecasts of aircraft noise levels, which were provided to the Minister as required by legislation. The forecasts were also published on the Canberra International Airport’s (CIA) website and used in a public debate concerning rezoning land under the flight path. Village, as a developer, contended the publication was in trade or commerce. On appeal, the Full Court said (at [53]):

The remaining representations relied on by Village were made by CIA to members of the public and to elected councillors and parliamentarians as part of a campaign to resist the application to rezone Tralee to facilitate residential development. There was no relevant trading or commercial relationship between CIA and the persons to whom the representations were made (although doubtless some would have occasion to use Canberra Airport from time to time). The representations could not be described as promotional activities designed to persuade consumers to use the services offered at Canberra Airport. Nor were they made as part of a process designed to secure approval to a commercial transaction or dealing, such as the sale of a component of CIA’s business (cf Dresna Pty Ltd v Misu Nominees Pty Ltd [2004] ATPR 42-013).

(emphasis added)

54 By comparison, in the present case there was a significant trading relationship involved, namely, between newsXpress and Nextra as trade competitors. Further, the Article was correctly found to be a promotional activity directed at newspaper franchisees.

55 It cannot be doubted that industry participants may from time to time act as commentators on industry affairs without those comments being in trade or commerce. Mr Fletcher draws on the example of the decision in SingTel Optus Pty Limited v Australian Football League [2012] FCA 138, where Edmonds J considered denigrating statements made by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Australian Football League about Optus engaging in illegal activities by operating its television recording service. His Honour held that those comments were not made in trade or commerce because, as his Honour observed (at [14]):

The statements complained of were part of a wide-ranging interview with [the CEO] covering a variety of topics, not all of them having to do with the AFL at all. To the extent that they concerned the AFL’s commercial interests, they consisted of statements of opinion by [the CEO] about the health and governance of the game and the member clubs of the AFL. To the extent that they concerned Optus, they were value judgments about the integrity and conduct of Optus in relation to the recording of content in respect of which the AFL owned the copyright.

56 Mr Fletcher argues that his comments are properly characterised the same way, but there are several differences between the facts at issue in the present appeal and those in Singtel Optus. First and foremost, the entirety of Mr Fletcher’s Article was an attack on Nextra. It was not part of a “wide-ranging interview” on other unrelated topics. Secondly, the entity which Mr Fletcher was attacking was his direct business competitor. Thirdly, findings were made, and were entirely reasonably made, by the primary judge that the purpose of the publication of the Article was to protect Mr Fletcher’s own business interests which were adversely affected by losing franchisees to Nextra as a result of what he said were false and misleading statements by Nextra in its Flyer. The facts of this case were quite different from Singtel Optus.

57 There can be little doubt that the remarks made by a commentator, as distinct from an industry participant, where they are unlikely to be intended to have an impact on trading or commercial activities, would not be conduct in trade or commerce. However, Mr Fletcher was not an independent commentator. He was an active participant in the newspaper franchise industry and intended his conduct to have an impact on trading or commercial activities.

58 The contentions advanced for Mr Fletcher on the first ground of appeal cannot succeed. The conclusion that the conduct was in trade or commerce was correct. Ground 1 must fail.

Grounds 2 and 3 – the representations and pleading of the representations

59 The focus of ground 2 is not on whether the representations were true or false, but whether the pleaded representations, as found, were made at all in the Article. Ground 3 conversely contends that, in any event, the representations as found were not pleaded.

60 It is strictly unnecessary to consider all of the representations which it is alleged were not made in the Article. It has already been established above that, contrary to ground 2(c), the Article did represent that Nextra had disseminated false information because, according to Article, the Flyer failed to distinguish between franchisees who had switched to Nextra as opposed to those who had switched to News Extra, that is, the Like for Like Representation.

61 There is no doubt that the Article made this representation and there is no doubt that it is incorrect.

62 The remaining representations under this ground of appeal may be dealt with briefly.

Ground 2(a) – distribution of material Nextra knew to be false

63 Mr Fletcher complains that his Article did not represent that Nextra distributed material it knew to be false, although he accepts, as he must, that the Article conveyed that the Flyer was intended to create a sense of fear in the reader. So much was accepted on his pleading. Mr Fletcher also admitted on his pleading that he represented in his Article that Nextra promoted the Nextra franchise in a manner which distributed false information.

64 The heart of Mr Fletcher’s complaint concerns whether Mr Fletcher represented that Nextra, in its Flyer, had distributed material it knew to be false. While there is a fine line between making the representation that Nextra distributed false information with an intention to create a sense of fear (which was admitted by Mr Fletcher), and a representation that Nextra knew that the distributed information was false, there is arguably a distinction, which may be important for Mr Fletcher’s reputation.

65 Although Nextra had not asserted at trial that Mr Fletcher’s Article contended that Nextra, in its Flyer, knowingly distributed false information, her Honour went further than was necessary and found that, in the Article, Mr Fletcher had represented that Nextra distributed material it knew to be false. However, the pleaded representation was comfortably subsumed within that finding. It cannot be said that the primary judge failed to address the pleaded representation.

Ground 2(b) – Nextra’s false listing of franchisees who had not in fact switched to Nextra from another group

66 The primary judge found that Mr Fletcher’s Article represented that Nextra in its Flyer had falsely listed franchisees who had not in fact switched to Nextra from another group. Mr Fletcher complains that the representation as found was not the representation pleaded. The complaint is that the inclusion of the word “falsely” was not part of the pleaded case. Mr Fletcher contends also that the finding by the primary judge as to the representation incorrectly omits the words “or to News Extra” after the word “Nextra”.

67 The primary judge considered that the imputation could be drawn from the repeated use in the Article of the words “false” and “misleading”. Further, and more specifically, in referring to newsagents switching to Nextra, the Article read:

5 On the flyer nextra list [sic] newsagents who have switched from one group to nextra? [sic] When did they switch? This is important as the details provided on the flyer are misleading and deceptive. Did they switch like for like – i.e. to nextra or the cheaper News Extra group?

(primary judge’s emphasis)

68 Mr Fletcher suggests that a fair reading of question 5 in the Article does not support the representation as found. Mr Fletcher argues that question 5 calls attention, in an enquiring form, to the timing of the newsagents’ switching to Nextra, and suggests that newsagents should check whether their colleagues switched to Nextra “or to the cheaper News Extra group”. A fair reading, it is argued, is that question 5, in referring to “misleading and deceptive”, should be properly understood as a warning that newsagents should check when the listed newsagents changed franchise group and the franchise group to which the switch was made. It should be noted that, in fact, as Mr Fletcher correctly points out, the word “false” is only once in the Article and the word “misleading” twice.

69 This argument is not persuasive. It is unrealistic to take words in isolation. It is unrealistic to view the questions asked in that Article as being merely points of advice on which readers may wish to conduct further queries. The content of the questions asked must be taken in context of the statement in the closing paragraph, which colours the entire Article, and which says:

… The decision on which marketing group to join should be based on facts, provable facts. The nextra flyer I have seen is not about facts. Indeed it contains some false and misleading information. Further, it uses fear to try and generate interest in nextra …

(emphasis added)

70 Further, the sentences to which a great deal of the case was directed, (extracted above (at 67])) are immediately followed by the statement: “[t]his is important as the details provided on the flyer are misleading and deceptive”.

71 The case theory that the Article did no more than raise questions, which underlies a number of Mr Fletcher’s submissions, must be firmly rejected.

72 The minor departures between the pleading and the finding are totally insignificant. Falsity was always at the heart of the pleaded case with regard to this representation. The conclusion reached by the primary judge was open as a matter of impression in construing the Article as a whole. The finding was well within the pleaded case.

Ground 2(d) – testimonials in the Flyer out of date

73 In determining whether the Article represented that the testimonials in the Flyer were out of date, the primary judge focussed on the fact that Mr Fletcher’s Article stated that “… the details provided on the flyer are misleading and deceptive” and that the Flyer “… contains some false and misleading information”. The primary judge said (at [60]-[62]) that the reference to “details” would be “read by a reasonable reader as including the testimonials on the Flyer” and therefore the Article carried the representation that the testimonials in the Flyer were either false or out of date.

74 Mr Fletcher again argues that it is not open to switch from the general to the specific, that is, that the assertion in broad terms that the details in the Flyer were misleading and deceptive could not have led to a conclusion that the Article also represented that the testimonials themselves were false or out of date.

75 As already noted, there is nothing in this point. It was entirely open to the primary judge to conclude that all of the questions raised by Mr Fletcher were rhetorical, that is, intended to suggest a specific answer. As such, the questions were capable of constituting representations.

76 The better point for Mr Fletcher is that the Article makes no reference to the testimonials in the Flyer. Mr Fletcher says that there was no evidence, or any finding, as to how many Flyers were distributed, the extent of the distribution, what the likely readership was or the state of relevant knowledge of readers. The Flyer was not appended to the Article. The Flyer was never published or distributed electronically. There was no evidence identifying the extent of the readership of the Article who would have had knowledge of the Flyer. Mr Fletcher says Nextra’s case at trial was that the meaning of the Article should be determined “by looking at it as though the [Flyer] were not being read in conjunction with it”.

77 It is correct that there was no express finding as to the extent of the distribution. However, Mr Fletcher’s submissions overlook the fact that, although the Article did not reproduce the Flyer, there was an express finding at trial, which is not the subject of appeal, that the Blog was directed to all newsagents (at [39]-[41]). Further, some (unknown numbers of) newsagents were also found to have received the Flyer. Therefore, the target group, as found, must have, or was at least ‘likely to’, have included some who received both. On the face of the Flyer, the “details” in the Flyer in fact were the testimonials and the list of franchisees who had switched. Such newsagents would reasonably understand “details” as including the testimonials found in the Flyer and the representation that they were false or out of date. The testimonials consumed a significant portion of the Flyer. The testimonials and their content are certainly capable of being described as being “details”.

78 The reasoning by the primary judge in relation to this representation cannot be flawed.

Ground 2(e) – Nextra franchise system did not improve the gross profit of any of the franchisees listed in the Flyer

79 In relation to this alleged representation in the Flyer, the primary judge again relied upon the combination of Mr Fletcher’s assertions that the Flyer was false and misleading with the rhetorical questions in the Article to reach her Honour’s finding.

80 Again, we reject the submission that Mr Fletcher’s Flyer merely suggested to newsagents that they should be put on enquiry.

81 It was open to the primary judge to find that the attacking tone of the Article generally reinforced the rhetorical nature of the questions asked and represented that switching to the Nextra and News Extra franchises did not improve gross profits.

82 The primary judge’s findings as to the pleaded representation conveyed by the Article were findings open on the evidence and were reasonably drawn from the text of the Article in the context of the evidence.

Grounds 4 and 5 – the primary judge’s failure to consider whether the statements in the Article were as to matters of opinion which were honestly held

83 Grounds 4 and 5 were the other major issues argued on the appeal.

84 As was correctly acknowledged on the hearing of the appeal, even if Nextra had been entitled to succeed on one only of the representations, the judgment against Mr Fletcher would stand. Although all of the representations challenged on appeal have been considered above, it is convenient in considering grounds 4 and 5 to focus on the Like for Like Representation. That representation was plainly a representation of fact. The factual assertion was, and is plainly, incorrect. The parties at trial made clear that while much or most of the Article was an expression of opinion, some of it was a statement of fact. This was one such part. There is no scope at all to assert now that there should have been a finding as to whether this representation of fact was or was not a representation of opinion and, if so, whether there was a reasonable basis for expression of the opinion. Nothing in the pleadings can affect the substantive law on that point and the parties did not suggest otherwise at trial.

85 In Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304, French CJ said (at [32]):

It is important in considering whether conduct is misleading or deceptive to identify clearly the conduct to be characterised. If the conduct is said to consist of a statement made orally or in writing, the first question to be asked is what kind of statement was made. Was it a statement of historic or present fact made on the basis that its truth was known to its maker? Was it a statement of opinion? That is to say was it a statement of “judgment or belief of something as probable, though not certain or established”? …

(footnotes omitted)

86 Certain representations in the Article were clearly representations of fact, such as the representation that Nextra failed to differentiate between franchisees who had switched to Nextra as opposed to those who had switched to News Extra in the Flyer. This representation of fact in the Article was false for the simple reason that the Flyer clearly did differentiate. That is sufficient to constitute a contravention of s 18 ACL.

87 Accordingly, as noted at the outset, it was unnecessary for Nextra to go further to plead that the facts were asserted without a reasonable basis for doing so. But having done so, it is self-evident that there was no reasonable basis for making the representation. A simple check of a legible colour copy of the Flyer would have revealed the falsity of the representation.

88 The primary judge did, however, go further in at least two instances in which she expressly found a lack of any reasonable basis. Taking the first will suffice. Her Honour said (at [74]):

74 … I consider that there is no basis for the general imputation in the Article that Nextra had, in the Flyer, distributed material it knew to be false. So, for example:

• Mr Fletcher does not dispute that each of the franchisees named as giving testimonials included in the Flyer had in fact switched to Nextra or to News Extra from other franchises.

• The testimonials clearly identify both the Nextra franchisees who had given testimonials and the Nextra franchisees who invited contact from prospective Nextra franchisees.

• The Flyer clearly identified whether the franchisees traded under the Nextra or News Extra logo.

• There is no evidence that senior personnel at Nextra, including Mr McFarlane, knew that one of the newsagencies listed (that is, Nextra Windsor) was insolvent at the time of distribution of the Flyer.

• There is no evidence that the testimonials included in the Flyer were false.

(emphasis added)

89 What should be emphasised from [74] is her Honour’s finding that there was no basis for the Like for Like Representation as “[t]he Flyer clearly identified whether the franchisees traded under the Nextra or News Extra logo”.

90 In any event, in the course of the trial, although Mr Fletcher said that the entire Blog was an expression of his opinion, he accepted (at T249) that it was not all his opinion and that some of it was statements of fact. Specifically, he said “… the [Blog] predominantly is my opinion, and sometimes that opinion stems from a representation of the facts”.

91 More fundamentally, although we were not provided with opening submissions of the parties at trial, counsel appearing for Mr Fletcher, quite correctly in the course of an objection to her Honour (at T256) said:

The intentions of the parties are irrelevant to this proceeding. The submissions of both parties are clear that intention is irrelevant to – and the question – well, at least the applicant’s submission, let me make that clear, say that intention as to misleading and deceptive conduct is irrelevant. It’s a question of looking to the evidence on the face of it, is this conduct the conduct misleading without reference to extraneous materials?

(emphasis added)

92 While the primary judge correctly considered (at T257) that the beliefs of Mr Fletcher were relevant to the case as pleaded, they were relevant at law only to those representations in which he had expressed an opinion.

93 In a summary contained in Mr Fletcher’s closing submissions, Mr Fletcher submitted (at [5(m)]) that:

In particular, the assessment of whether the conduct is likely to be misleading must take place in context, which includes a judgement about whether statements of fact are correct and statements of opinion have a reasonable basis. As the Flyer was the genesis of the Article, the two cannot be considered in isolation.

(emphasis added)

94 The way the parties conducted the trial is mirrored in the appeal submissions. Mr Fletcher himself in his appeal submissions (at 41(h)) correctly referred to content of the Article and the aspects of it which are statements of fact as distinct from statements of opinion. The submissions went on (at [42]) to contend that “[t]o the extent the Article concerned matters of opinion there is no basis for a finding that the opinions were not honestly held” (emphasis added). Mr Fletcher was not taken by surprise at all in the suggestion that the Article contained statements of fact, as it very clearly did.

95 The closing submissions of Nextra as applicant at trial and the responding submissions of Mr Fletcher do not suggest that the Like for Like Representation was anything other than a representation of fact (nor could they do so) and, indeed, as previously noted, Mr Fletcher’s own submissions make it clear that Mr Fletcher treated the Like for Like Representation as being one of fact. Mr Fletcher submitted in his final submissions that the Article was justified by matters which were factually correct and contained opinion which had a reasonable basis. Mr Fletcher correctly submitted that questions for the Court were:

(iii) Did the Article contain statements of fact or opinion?

(iv) If the Article contained statements of Fact, were they true?

96 It would be entirely artificial to suggest that some gloss was to be added to the statutory requirements which required establishing that there was no reasonable basis for a representation once a misrepresentation of fact had been established. There is not the slightest hint that the parties were labouring under such a misguided impression in the way they approached the evidence and the law and their written submissions.

97 Indeed, both sets of submissions make little or no reference at all to the question of whether there was a reasonable basis for expressing statements of opinion. Even if they did, that question could have no relevance at law to the establishment of the contravention of s 18 ACL to the extent that it related to a misrepresentation of fact.

98 It can be seen that although the “no reasonable basis” pleading covered both factual and opinion representations, the parties at trial did not conduct their case on the artificial footing that proof of the “Like for Like Representation” required proof of an absence of reasonable basis for making a representation of fact. Even then, the primary judge did consider (at [74]) whether there was “no basis” in the context of this representation.

99 Parties are bound by the way they conduct their case at trial: see Overton Investment Pty Ltd v Murphy [2001] NSWCA 183 per Mason P (at [86]-[87]) (Sheller JA and Beazley JA agreeing); University of Wollongong v Metwally (No 2) (1985) 59 ALJR 481 (at 483); Chilcotin Pty Ltd v Cenelage Pty Ltd [1999] NSWCA 11 (at [15]); Thompson v Palmer (1933) 49 CLR 507 per Starke J (at 528-529); Haig v Minister Administering National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (1994) 85 LGERA 143 per Kirby P (at 155); Coulton v Holcombe (1986) 162 CLR 1 per Gibbs CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Dawson JJ, Deane J contra) (at 7).

100 Both on the face of the matter and in the manner in which the parties conducted the trial, the question of whether or not the Flyer distinguished between the entities to whom the various franchisees switched was both a pleaded issue and a question of fact. It was a factual inaccuracy because it is clear that the Flyer did so distinguish. Being a statement of fact which was wrong, whether or not there was reasonable basis for expressing it is irrelevant.

CONCLUSION

101 The primary judge was correct to conclude that the publication of the Article was conduct in trade or commerce. Further, as found, the Article represented a specific fact which was clearly wrong on the face of the Flyer. Unfortunately, Mr Fletcher committed himself to the publication before receipt of a completely legible colour copy of the Flyer. As a consequence, the Like for Like Representation, at least, was factually wrong. On that basis alone, despite this dispute being far too costly and wasteful for the limited events it canvasses, Nextra was entitled to succeed below and the appeal must be dismissed.

102 The following orders are made:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the costs of the respondent, to be taxed if not agreed.

I certify that the preceding one hundred-two (102) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Middleton, McKerracher and Davies. |

Associate: