FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Limited v ThredboNet Marketing Pty Limited

[2014] FCAFC 87

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellants pay the respondents’ costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1311 of 2013 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | KOSCIUSZKO THREDBO PTY LIMITED (ACN 000 139 015) First Appellant THREDBO RESORT CENTRE PTY LIMITED (ACN 003 896 026) Second Appellant |

| AND: | THREDBONET MARKETING PTY LIMITED (ACN 097 622 869) First Respondent GLENN SMITH Second Respondent |

| JUDGES: | SIOPIS, RARES & KATZMANN JJ |

| DATE: | 21 JULY 2014 |

| PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

1 Thredbo is a town within the Kosciuszko National Park in the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales and a popular centre for snow sports and other recreational activities. In the proceeding below the appellants sought to restrain the respondents from using the word “Thredbo” in various domain names, company and business names, and on their website. The appellants also sought to recover damages for loss they claimed to have suffered, though did not successfully prove. They alleged that “Thredbo” had acquired a secondary meaning associated with the appellants’ business and that the respondents were engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct by using the name to promote their business. They claimed, amongst other things, that in doing so the respondents had contravened the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL) in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). They also claimed that the respondents had sought to pass off their business as that of the appellants. Save in one respect, their claims failed.

2 The appellants are related companies. Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Limited (“KT”) is a company which holds a lease over land in the national park. The lease covers the area in which Thredbo Village is located and the Thredbo Resort operates. The resort was established in the 1950s by Messrs Tony Sponar, Charles Anton and Geoffrey Hughes, who first approached the Kosciuszko State Park Trust for a lease for a ski resort. The men formed a syndicate, which in 1957 was incorporated into a company known as Kosciuszko Thredbo Limited. KT took an assignment of the lease in 1987 and since then has owned and operated the resort and maintained the village. It also owns and operates a ski school, the Thredbo Alpine Hotel and an accommodation complex as well as various other enterprises carrying on business in the village, including the Thredbo Leisure Centre and the Thredbo Childcare Centre. It also provides certain public amenities such as the water supply, sewerage systems, public roads and infrastructure. The second appellant, Thredbo Resort Centre Pty Limited (“TRC”) is a wholly owned subsidiary of KT. It provides a central booking service for accommodation available at Thredbo and is known as “Thredbo Resort Centre” or “Thredbo Central Reservations”. The centre also provides information relating to the resort and village, the facilities available there and activities which can be enjoyed whilst staying there.

3 Glenn Smith, the second respondent, and his company, ThredboNet Marketing Pty Limited, the first respondent, run an online business in competition with KT and TRC, managing and leasing rental accommodation in Thredbo. The business has been conducted through a number of websites, the domain names of which incorporate the Thredbo name.

4 The appellants’ case at trial was that KT had acquired considerable goodwill and reputation in Thredbo village. This claim was based on the fact that the appellants trade under the name “Thredbo Alpine Village”; manage and service the amenities at the village; operate the Thredbo ski lift, ski school and various other activities; manage the Thredbo Alpine Hotel and other accommodation in the village and provide, through TRC, a central accommodation booking service and tourist information centre. The appellants submitted that the lease arrangements put KT in a unique position of control over the resort, likening it to Disneyland. They contended that Thredbo is “more than a place”; it is a “complete branded entity”. Since 1997 KT has also owned and operated the website for the resort, www.thredbo.com.au. The appellants submitted that “thredbo.com.au”, itself, has become “a brand in its own right”.

5 The appellants complained that Mr Smith, through ThredboNet, had developed a number of websites and a Facebook page to promote not only the accommodation services offered by ThredboNet Marketing, but also other activities, including those offered by KT. They also complained that the respondents’ websites and Facebook page had a similar appearance and content to KT’s website and Facebook page. They contended that this conduct amounted to misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to ss 18(1), 29(1)(g) and (h) of the ACL and also passing off. They argued that while Thredbo “has become known” as a geographic location, through the operation of their business and their marketing, “Thredbo” had acquired a secondary meaning or independent reputation for their skiing resort services, including hotel and accommodation services. Indeed, they submitted that the name “Thredbo” had become synonymous with their resort business and services and that by their use of the name the respondents had “invade[d]” the appellants’ goodwill and misrepresented that their websites and the goods and services offered through them were affiliated with the appellants.

6 Mr Smith also holds two subleases from KT over two properties in the village. Clause 4.3 in each of the subleases purports to prevent him from using the word “Thredbo” in connection with any business he may carry out unless he has KT’s written consent to do so. KT claimed that Mr Smith had breached the terms of that clause by registering without its consent company names, business names and, more particularly, “an extensive suite of domain names” incorporating the word “Thredbo”. The primary judge held that the clause was invalid as a restraint of trade and could not be read down.

The findings of the primary judge

7 The primary judge found (at [95]) that the appellants had not proved that the word “Thredbo” has acquired a secondary meaning. He defined that as meaning, controversially:

that the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in its business names, internet names and logos has become so distinctive such that [the appellants have] a right to use it to the exclusion of all others.

8 His Honour held that all the parties were entitled to use the word and that, with one exception related to the use of the catchphrase ‘My Thredbo’, which for present purposes is irrelevant (the respondents having abandoned their cross-appeal), the respondents’ operation of websites with domain names such as www.thredboreservations.com.au or www.thredbo.com was not misleading or deceptive (and, by inference, not likely to mislead or deceive).

9 His Honour rejected the appellants’ contention that the content and appearance of the respondents’ websites was misleading or deceptive because the general “get-up” of the websites was substantially identical with or deceptively similar to KT’s website and common law trade mark. He pointed to various differences in the general layout and colours of the parties’ websites and noted that the only similarities between them related to the use of “unremarkable and different” snow scenes. He also noted the fact that after the proceeding was launched and before the hearing the respondents had included on their “primary” website (www.thredbo.com) a disclaimer in the following terms:

About thredbo.com

This website is operated by Thredbonet Marketing Pty Ltd. Our company manages more than 50 properties in Thredbo and has provided booking and accommodation services in Thredbo since 2001. Please note this is NOT the official website of the owner and operator of the Thredbo Alpine Village or the Thredbo Ski Resort, Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Ltd, and is not approved, endorsed or sponsored by them.

10 His Honour held that because of the differences between the parties’ websites, consumers were not likely to be misled into believing that the respondents’ web pages belonged to the appellants. He characterised the evidence called by the appellants to support their claim as “evidence of confusion”, falling short of what is required to establish a contravention of the relevant sections of the ACL.

11 For similar reasons his Honour also rejected the claim that the respondents’ Facebook page entitled “Thredbo Reservations” was misleading or deceptive. He found that the fact that almost 50,000 people had “liked” KT’s Facebook page, in contrast to only 200 who “liked” that of ThredboNet suggested that consumers would not form the view that ThredboNet’s Facebook page was associated with KT’s Facebook page (despite some similarities between the pages).

12 His Honour considered that there were no practical differences between the claim under the ACL for misleading or deceptive conduct and the claim of passing off. For this reason he said there was no utility in deciding the passing off claim.

13 The remaining findings concerned the subleases.

14 Mr Smith contended that the clauses (prohibiting Mr Smith from using the word “Thredbo” in connection with his business) were invalid as restraints of trade and that if the Court were to read down the clauses so as to apply only within the land specified in the subleases, then he did not conduct the ThredboNet business in Thredbo, but from an address in Cammeray. KT argued that the restraint of trade doctrine was irrelevant because it did not apply to restrictive covenants given by a lessor or purchaser of land. His Honour rejected this argument. First, he said that the submission was stated too broadly. He explained that, although the doctrine does not apply to covenants which protect the amenity of land, it does apply to covenants imposed in a trade or commercial context or for a trade or commercial purpose, referring in particular to the remarks made by Jacobs J in Quadramain Pty Limited v Sevastapol Investments Pty Limited (1976) 133 CLR 390 at 415. He found that the covenant was not imposed to protect the amenity of the land subleased to Mr Smith or any other land. Secondly, “on its face” the restriction imposed by the clause was not limited to the land in question. He observed that the clause purported to prevent Mr Smith from carrying on his business anywhere in the world while he continued to sublease premises in Thredbo.

15 Consequently, his Honour found that the clause operated as a restraint of trade. He said that there was no evidence that the clause was of a type that a trading society considered a necessary part of doing business. He also found that the absence of limitations as to time or place suggested a deviation from accepted standards and a greater than usual restriction of an individual’s right to trade.

16 His Honour accepted that Mr Smith was prima facie in breach of the clause. But his Honour went on to hold that the clause was an unreasonable restraint of trade. He considered that it could not be read down (in accordance with s 4 of the Restraints of Trade Act 1976 (NSW)) so as to make it reasonable. In view of his earlier findings, his Honour concluded that the restriction on the use of the word “Thredbo” imposed by KT offended Mr Smith’s freedom to “earn his living as best he can”, depriving ThredboNet of its common law right, with other traders, to use the name “Thredbo”.

The appeal

17 The appellants pitched their case at a very high level both at first instance and on appeal. The notice of appeal, which contains in effect some 26 grounds, suffers from the vice identified by Branson J in Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 55 IPR 354; [2002] FCAFC 157 (“Sydneywide”) at [4]:

A ground of appeal is a basis upon which the appellant will contend that the judgment, or a part of the judgment, should be set aside or varied by the court in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction. Not every grievance entertained by a party, or its legal advisors, in respect of the factual findings or legal reasoning of the primary judge will constitute a ground of appeal. Findings as to subordinate or basic facts will rarely, if ever, found a ground of appeal. Even were the Full Court to be persuaded that different factual findings of this kind should have been made, this would not of itself lead to the judgment, or part of the judgment, being set aside or varied. This result would be achieved, if at all, only if the Full Court were persuaded that an ultimate fact in issue had been wrongly determined. The same applies with respect to steps in the primary judge’s process of legal reasoning. Although alleged errors with respect to findings as to subordinate or basic facts, and as to steps in a process of legal reasoning leading to an ultimate conclusion of law, may be relied upon to support a ground of appeal, they do not themselves constitute a ground of appeal.

18 Rule 36.01(2)(c) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (formerly O 52 r 13(2)(b)) requires that a notice of appeal state “briefly but specifically, the grounds relied on in support of the appeal”. In Sydneywide her Honour went on to say (at [5]) that:

A useful practical guide is that a notice of appeal which cannot be used to provide a sensible framework for the appellant’s submissions to the Full Court is almost certainly a notice of appeal which fails to comply with the requirements of O 52 r 13(2)(b).

19 The notice of appeal in this case answers this description. The appellants’ submissions were discursive and paid scant regard to the grounds of appeal. It was difficult at times to relate them to the grounds. They misled the respondents into thinking that some grounds had been abandoned when they had not. Ultimately, the submissions were revamped and the grounds were reduced to eight. They allege that the primary judge erred in the following respects by:

(1) holding that in order to establish a secondary meaning in the word “Thredbo” the appellants had to establish they had an exclusive right to use the word;

(2) failing to consider KT’s unique leasehold arrangements, which gave it control of the entire head lease area;

(3) giving insufficient consideration to the evidence that “Thredbo” and the domain name www.thredbo.com.au, owned by KT, are distinctive of the appellants so as to establish a secondary meaning in both those terms;

(4) holding that evidence of consumer deception was “mere confusion” and was not capable of leading to a finding of misleading or deceptive conduct and/or passing off;

(5) holding that the parties’ Facebook pages were insufficiently similar to justify a finding that the respondents had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or amounted to passing off;

(6) holding that the doctrine of restraint of trade applied to cl 4.3 of the subleases;

(7) holding that cl 4.3 was unreasonable; and

(8) holding that cl 4.3 could not be read down pursuant to the Restraints of Trade Act.

20 Notwithstanding the reference to passing off in grounds (4) and (5) above, the appellants did not press their challenge to the primary judge’s failure to separately consider the cause of action in passing off.

21 Three broad issues therefore arise on the appeal:

(1) whether the primary judge was wrong to conclude that the appellants had not established a secondary meaning in the word “Thredbo”;

(2) whether the appellants had proved that the respondents’ conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(3) whether cl 4.3 of each sublease is invalid.

Issue (1) – secondary meaning – the appellants’ arguments

22 The appellants submitted that the primary judge fell into error at the outset by characterising the first question he had to decide in the following terms:

Does the word ‘Thredbo’ have a secondary meaning such as to identify ‘Thredbo’ only with [the appellants’] business?

23 The appellants pointed to several passages in the reasons for judgment which touch on the notion of exclusivity and his Honour’s references to cases decided under the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) and Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) as indicative of error. In short, the appellants contended that his Honour was applying the wrong test. They argued that this was not a case where they had claimed to be entitled to register the word “Thredbo” as a trademark, where the test would be one of exclusivity. The appellants argued that at no point did his Honour consider “the true question”, which they described in their written submissions as follows:

whether, on the whole of the evidence before him, the word [“Thredbo”] in any of the forms used by the appellants (including its use in the domain name www.thredbo.com.au) had become sufficiently distinctive to a not insignificant number of consumers to render the conduct of the respondent (sic) misleading and deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.

(Footnotes omitted.)

24 In support of their proposition that this was the correct question, the appellants cited Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 222 at 263–264 [206]–[210] and Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (2007) 159 FCR 397 at 418 [96]. They went so far as to assert that his Honour “entirely failed to engage with the case presented to him by the appellants”. The appellants contended that the question that the primary judge should have addressed was whether the respondents’ use of the word “Thredbo” was calculated to lead potential or actual consumers of their common services to the belief that the respondents’ business was that of the appellants, in accordance with the test formulated by Lord Simonds in Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd (1946) 63 RPC 39 at 42 and applied by Gummow J in Telmak Teleproducts (Australia) Pty Ltd v Coles Myer Ltd (1988) 84 ALR 437 at 442–443 as a test both for a contravention of statutory predecessors and analogues of s 18 of the ACL and passing off.

25 The appellants argued that, although it was a geographic word, “Thredbo” was so distinctive of their business as to give the word a secondary meaning that consumers associated with the appellants’ village and resort operation in all its aspects. They contended that use of the word “Thredbo” by the respondents was misleading or deceptive or amounted to passing off because consumers would associate the appellants’ businesses with those operated by the respondents by reason of the latters’ use in domain names and websites of the names complained of, such as “Thredbo Reservations” on their Facebook page, “ThredboNet” and “thredbo”.

26 The appellants argued that “Thredbo” was not “in the strongest sense of the term, a genuine geographic name” because it had been coined in the 1950s as the name of the village and resort. The appellants’ predecessors in title had created Thredbo as a village and resort in a previously undeveloped landscape. They contended that this unusual origin led to an exceptional level of association in the consuming public’s mind between the place and the appellants so that, in effect, “Thredbo” was synonymous with the Thredbo Resort and would not exist but for the resort. The appellants argued this had come about because they were the services provider for the village, direct operators of some businesses there (such as the chairlifts and other ski lifts, ski school, Thredbo Alpine Hotel) and the sublessor of all other premises, including those from which all other businesses operated and all accommodation could be offered. They contended that their extensive advertising and promotional activities of the resort for both winter and summer recreation since 1987 had created and reinforced the public perception of their businesses as being synonymous with the name “Thredbo”.

Issue (1) – secondary meaning – consideration

27 In our opinion, his Honour erred in holding that the appellants had to prove that they had the exclusive right to use the word “Thredbo” in order to prove that it had acquired a secondary meaning before they could establish that the respondents’ conduct of which they complained could be found to contravene, among other provisions, s 18 of the ACL or amount to passing off. His Honour applied the wrong test for his consideration of those questions and his reasons for rejecting the appellants’ claims based on s 18 and passing off were premised on his finding that they had failed to prove that the word “Thredbo” had a secondary meaning so that they had, and could enforce, an exclusive right to use it. It is difficult to understand why his Honour thought it necessary to decide whether the appellants had made out a case of exclusivity. As his Honour recognised (at [70]), the appellants did not contend for it. Indeed, they submitted below that an applicant’s secondary meaning or reputation need not be exclusive, either for passing off or for misleading and deceptive conduct. They did not quibble with the evidence that Thredbo is a geographic place and has been for over a century. They did not seek to restrain the use of the name Thredbo as descriptive of the locality. Their point was (and is) that a geographical name when used as a trade mark or brand name may be found to have been adapted to distinguish the appellants’ goods or services while at the same time being part of the common heritage.

28 It is possible that his Honour was confounded because of the claim based on the subleases. As the respondents submitted below, the assertion that the appellants do not seek to control the use of the name “Thredbo” when used in a descriptive sense contradicts the control it sought to exercise through the restrictive covenants in the subleases which impose a blanket prohibition on the use of the word.

29 The appellants did not have to establish that they had a right to use the word “Thredbo” to the exclusion of all others in order to establish the contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(g) and (h) they complained of. In Cadbury Schweppes 159 FCR at 418 [96] Black CJ, Emmett and Middleton JJ held that the principles relating to passing off did not necessarily require an applicant, such as a confectionery maker, to establish an exclusive reputation in relation to the use of a particular colour or other distinguishing characteristic, in that case, purple. Likewise, their Honours held that it was possible to contravene the analogues of ss 18, 29(1)(g) and (h) even though the applicant had not established that it had an exclusive reputation in relation to the characteristic in issue. They held that the question was whether the applicant could establish facts that demonstrated that a particular use by the respondent of the characteristic in issue (in that case, the colour purple) misled or deceived, was likely to mislead or deceive, consumers into believing that “there is some relevant connection between [the respondent] and [the applicant] or their respective products”. The Full Court then held (157 FCR at 418–419 [99]):

Whether or not there is a requirement for some exclusive reputation as an element in the common law tort of passing off, there is no such requirement in relation to Pt V of the Trade Practices Act. The question is not whether an applicant has shown a sufficient reputation in a particular get-up or name. The question is whether the use of the particular get-up or name by an alleged wrongdoer in relation to his product is likely to mislead or deceive persons familiar with the claimant’s product to believe that the two products are associated, having regard to the state of the knowledge of consumers in Australia of the claimant’s product.

30 Accordingly, the primary judge’s treatment of the issue of secondary meaning was erroneous. But that is by no means the end of the matter. As Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ noted in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 87 [105], the initial question that must be determined in a claim under a provision like s 18 is whether the misconceptions or deceptions alleged to arise or to be likely to arise are properly to be attributed to the ordinary or reasonable members of the classes of consumers or prospective purchasers of the relevant goods or services. Thus, the question here is whether ordinary or reasonable members of those classes would, or would be likely to, understand that any of the respondents’ impugned uses of the word “Thredbo” conveyed to them that they were dealing with the appellants or one of them.

31 In the end, the word “Thredbo” is a geographical name of a location in New South Wales. The appellants’ resort and businesses are located there and they hold (and their predecessors in title held) the head lease over the land on which the village and resort complex are located. But others also operate businesses, as sublessees, in the physical location known as Thredbo. The real issue was not whether the appellants had established a monopoly over the right to use the word “Thredbo” but whether they had established that the respondents’ conduct in using that word was likely to lead ordinary or reasonable consumers seeking accommodation or services in Thredbo into believing that the respondents’ business or the accommodation or other services that the respondents were offering was or were that or those of the appellants: Campomar 202 CLR at 87 [105]; Office Cleaning 63 RPC at 42. The more significant issue, then, is whether the primary judge erred in his conclusions on the question whether the respondents’ conduct was misleading or deceptive (or likely to be so).

Issue (2) – misleading conduct

32 On this question his Honour’s reasoning was orthodox. It involved an application of the principles in Hornsby Building Information Centre Proprietary Limited v Sydney Building Information Centre Limited (1978) 140 CLR 216. With one exception, the issue of exclusivity did not intrude into the reasoning process. The exception is in [143], which Mr Smark SC, who appeared for the respondents, candidly described as the low point of his case. There, however, his Honour did not state that the fact that the appellants had failed to prove exclusivity meant that they could not succeed. What he said was that the failure to prove exclusivity meant that, save in relation to the Genkan link, the respondents’ use of word “Thredbo” was “unexceptional”. Importantly, he went on to say at [144]:

Stephen J’s reasoning in Hornsby Building Information Centre, set out at 228-229, also applies to the circumstances in this proceeding. KT has chosen to primarily market its ski resort as ‘Thredbo’, which is a ‘word of locality’. Occasionally, it uses the word in conjunction with descriptive words, such as ‘Thredbo Resort’ or ‘Thredbo Reservations Centre’. When another company, which also conducts business in Thredbo, decides to use a similar arrangement of the ‘word of locality’ plus descriptive or generic words, e.g. ‘Thredbo Accommodation Reservations’, then KT cannot be heard to complain that such conduct is misleading or deceptive.

33 His Honour also drew upon Emmett J’s decision in connect.com.au Pty Ltd v Goconnect Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 178 ALR 348; [2000] FCA 1148.

34 The primary judge observed correctly at [139] that mere confusion in the mind of a consumer does not equate to misleading or deceptive conduct. Lord Simonds observed in Office Cleaning 63 RPC at 43 (in a passage cited with approval by Stephen J in Hornsby at 229) that as long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their trade names, some members of the public may well be confused no matter what differentiating words are used. Stephen J said that (140 CLR at 229):

[t]he risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.

Issue (2) – misleading conduct – appellants’ submissions

35 The appellants submitted that the primary judge had rejected their claims in respect of contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(g) and (h) and for passing off because of his error that they had to have the exclusive right to use “Thredbo” before they could succeed on them. The appellants also argued that there was evidence that consumers had been misled or deceived. In particular, they pointed to the evidence of Michael Brooks, whom his Honour preferred over Mr Smith on this issue. Mr Brooks had booked accommodation for his family for a week using the respondents’ website in the belief that he was dealing with the appellants. Mr Brooks was only disabused when he complained to KT after arriving for his family ski holiday to find the accommodation he had paid for was already occupied because it had been double booked. His Honour found Mr Brooks to have been prudent and careful in making his booking to the extent that a typical consumer would have been in arriving at his belief that he was dealing with the appellants. The appellants also referred to other instances where they had received complaints and other communications from persons who, in fact, had dealt, or intended to communicate, with the respondents. The appellants submitted that, the primary judge came to the conclusion that the respondents had not contravened ss 18, 29(1)(g) and (h) only because he had erroneously held that the appellants had failed to establish that they had an exclusive right to use, or a monopoly over, the word “Thredbo”.

36 The appellants argued that two disclaimers that the respondents had placed on the home page of the www.thredbo.com website were inadequate. The first disclaimer appeared by about late April 2012 in the following form:

About Thredbo.com

This website is operated by ThredboNet Marketing Pty Ltd. Our company manages more than 50 properties in Thredbo and has provided booking and accommodation services in Thredbo since 2001.

37 On 28 November 2012, the respondents gave an undertaking to the Court that they would substitute for the first disclaimer a second disclaimer as follows:

This website is operated by Thredbonet Marketing Pty Ltd. Our company manages more than 50 properties in Thredbo and has provided booking and accommodation services in Thredbo since 2001.

Please note this is NOT the official website of the owner and operator of the Thredbo Alpine Village or the Thredbo Ski Resort, Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Ltd, and is not approved, endorsed or sponsored by them.

38 At the same time the respondents also undertook to add to the www.thredboreservations.com.au website the following disclaimer below a heading “About Thredboreservations.com.au:

Please note this is NOT the official website of the owner and operator of the Thredbo Alpine Village or the Thredbo Ski Resort, Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Ltd, and is not approved, endorsed or sponsored by them.

39 The appellants argued that each disclaimer was not apt to remove the allegedly misleading effects of the respondents’ two websites because each was “buried in the middle of a mass of other text on the homepages of the websites”. The appellants contended that the surrounding text and get up of each homepage appeared deceptively similar to the appellants’ website www.thredbo.com.au.

Issue (2) – misleading conduct – consideration

40 In essence, the appellants’ case was that they were identified as “Thredbo” in the public mind and that substantively any use of that word in relation to activities or businesses that were, or could be, conducted at that place would be associated with them.

41 We reject that argument. The appellants are not entitled to a monopoly in the use of the word “Thredbo” in association with accommodation in Thredbo. Ordinarily, a trader is entitled to use a geographical name honestly and accurately unless that name has become distinctive of another’s goods or services and the trader is using the name to pass off its goods or services as those of the other. The respondents did not do that here.

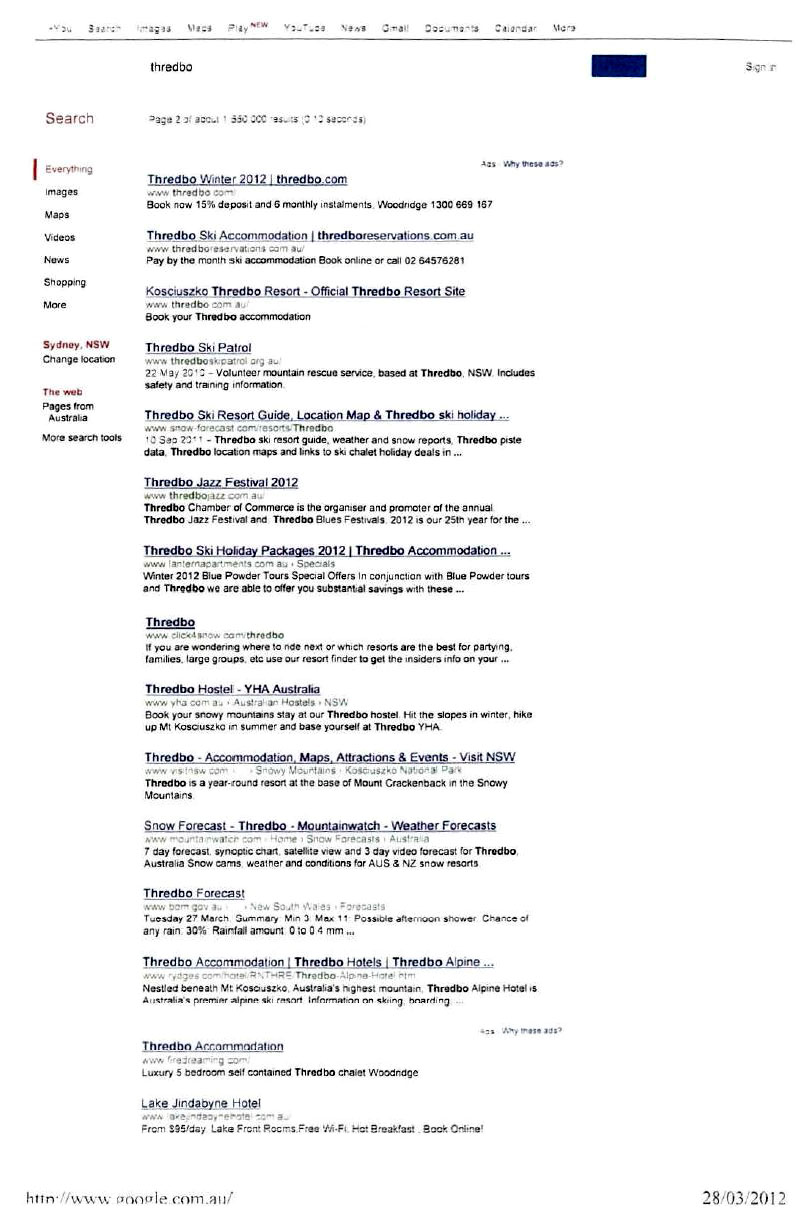

42 The respondents’ websites did not have the appearance of those of the resort operator. They appeared as websites that offered a limited range of accommodation and provided information about some activities that were available at Thredbo, but not offered by the respondents, that could be enjoyed by visitors to Thredbo. A screen shot at 28 March 2012 of page 2 of a Google search for “Thredbo” showed the following:

43 As is apparent, not only do the appellants’ and respondents’ website links appear in the screen shot with different descriptions and domain names, but so do a lot of others that use the word “Thredbo” in one way or another. There was no evidence of the results for the first page of the search of “Thredbo”. Ordinarily, most people searching for a term or information will look at the first page of search results and then select the most apparently appropriate link or links from that page before they would move to a second or subsequent page of search results. Indeed, they would be unlikely to see any need to go to a second or subsequent page of search results unless they had not found some satisfactory site or sites on the first page.

44 A similar set of search results, showing a variety of links to other entities than just the parties, appeared in the screen shot for the first page of the Google search for “Thredbo reservations” as at 28 March 2012. That usage is consistent with honest and legitimate trading and almost inevitable where, as here, a geographical name is used by a trader as part of its name. The search results negate the appellants’ contention that the word “Thredbo” denotes such an established secondary meaning in relation to their businesses and services, including as accommodation providers, as to render the respondents’ conduct in using that word misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

45 It was not as if the appellants were the only persons who offered accommodation at Thredbo to the public before the commencement of the conduct complained of. The conduct complained of is not in the category of case justifying an injunction against a trader passing off his goods or services as those of a rival, such as is illustrated in Thomas Montgomery v Thompson [1891] AC 217. There, Lord Macnaghten, with his customary pungency, discussed the terms of an injunction granted against a fraudulent trader who had set up a brewery business at the town of Stone. The plaintiff had for a century carried on its business there and had for many years been famous for producing ales known as “Stone Ales”, a name the defendant applied to the products he produced “in the hope of reaping where he had not sown” (at 223). His Lordship said of the defendant (at 225):

It would have been impossible for him to have called his ales “Stone Ales,” and to have distinguished his ales from those of the plaintiff. Any attempt to distinguish the two, even if honestly meant, would have been perfectly idle. Thirsty folk want beer, not explanations. If the public get the thing they want, or something near it, and get it under the old name – the name with which they are familiar – they are likely to be supremely indifferent to the character and conduct of the brewer, and the equitable rights of rival traders.

(Emphasis added.)

46 The same imperatives do not apply to consumers doing internet searches for accommodation or holidays and being presented with an array of providers or businesses associated with a well-known geographical location of a resort. The respondents sufficiently distinguished their websites from the business of the appellants by their use of disclaimers and their offers of supply that were limited to some accommodation.

47 The www.thredbo.com domain name might, if viewed in isolation, suggest a connection with the appellants’ business that the respondents do not have. But on the Google search result screen shot for “Thredbo reservations” the material associated with that domain name appears to offer only accommodation principally at Woodridge, a discrete area in Thredbo Village, which a consumer who clicked on the link would immediately appreciate when taken to the webpage. That appreciation would be reinforced by either disclaimer (depending on which was shown). Such a consumer would appreciate that he or she could not purchase ski lift tickets or ski lessons from the operator of that website.

48 We are not satisfied that a consumer who went to any of the respondents’ websites would reasonably have associated the operator of the website with the appellants. The respondents’ domain name www.thredbo.com was very similar to that of KT, namely www.thredbo.com.au. A consumer might easily be led to the former website thinking it was that of the appellants when doing an internet search. But in today’s society the ordinary or reasonable consumer seeking accommodation, or other goods or services, on the internet will frequently click on a result in a web search thinking it is a link to a particular site, only to find when his or her browser is directed to the selected site that it is not the site of the supplier or business that the consumer wanted. The ordinary, reasonable consumer who came upon the home page of www.thredbo.com would have seen, depending on when he or she accessed it, the first or second disclaimer in the middle of the page. Each disclaimer appeared under a recognisable, distinctive heading “About Thredbo.com”. It did not have the appearance, as asserted by the appellants, of being “buried in the text”.

49 A consumer who was concerned about the entity with which he or she was dealing could be expected to read the short text under that heading. As Gibbs CJ pointed out of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (which is in substantively the same terms as s 18 of the ACL) in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Proprietary Limited v Puxu Proprietary Limited (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199:

Although it is true, as has often been said, that ordinarily a class of consumers may include the inexperienced as well as the experienced, and the gullible as well as the astute, the section must in my opinion by (sic) regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class. The heavy burdens which the section creates cannot have been intended to be imposed for the benefit of persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. What is reasonable will or (sic) course depend on all the circumstances. The persons likely to be affected in the present case, the potential purchasers of a suite of furniture costing about $1,500, would, if acting reasonably, look for a label, brand or mark if they were concerned to buy a suite of particular manufacture.

The conduct of a defendant must be viewed as a whole. It would be wrong to select some words or act, which, alone, would be likely to mislead if those words or acts, when viewed in their context, were not capable of misleading. It is obvious that where the conduct complained of consists of words it would not be right to select some words only and to ignore others which provided the context which gave meaning to the particular words. The same is true of acts.

(Emphasis added.)

50 The first disclaimer made clear that the website was not associated with the appellants. The second disclaimer emphasised that the website was “NOT the official website of the owner and operator of the Thredbo Alpine Village or the Thredbo Ski Resort, [KT], and is not approved, endorsed or sponsored by them”. An ordinary reasonable consumer who was concerned about the identity of the operator of that website would have appreciated that the first and second disclaimers meant what they said. The same reasoning applies to the www.thredboreservations.com.au home page after late November 2012.

51 Although the respondents’ Facebook page did not have a disclaimer, it used a large heading, “Thredbo accommodation reservations”, and had the appearance of a site offering limited accommodation within the larger available pool in Thredbo village. It displayed a reference to www.thredbo.com accommodation reservations. The screen shot of that page taken on 13 November 2012 showed 106 “likes” – a trivial number compared with that of the resort operator KT which had nearly 40,000 “likes” on its Facebook page in a screen shot of 24 July 2012. The difference in the “likes” for each Facebook page is the more telling, as that of KT was recorded at the peak of the ski season during the period of the conduct complained of, while the desultory 106 likes for the respondents’ Facebook page were the end product of that conduct recorded nearly four months later, during the trial.

52 While there was some limited evidence of confusion, including of Mr Brooks whom his Honour regarded as prudent and careful, the material to which we were taken during the appeal did not suggest that this confusion was widespread or such as would have caused an ordinary reasonable consumer, as a member of a class, to be misled or deceived into associating the respondents’ business with that of the appellants, or that such a result was likely.

53 In our opinion, the get-up and appearance of the respondents’ websites were not such as would lead the ordinary reasonable consumer into a belief that they were associated with the appellants’ businesses. The respondents were in the business, as were the appellants, of providing accommodation at Thredbo. The arranging, acquisition or purchase of such accommodation ordinarily required a potential consumer to agree to pay a not insignificant sum of money. Moreover, the ordinary reasonable consumer looking for holiday accommodation at a resort such as Thredbo would be careful about making a selection of the provider, the accommodation and the price.

54 Thus, we are not satisfied that the appellants established that the respondents’ conduct amounted to a contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(g) or (h) or to the tort of passing off.

Issue (3) – clause 4.3 of the subleases – the restraint of trade issues

55 Mr Smith was the sublessee of two properties in Thredbo Village. KT was his immediate lessor. Each sublease was a sublease registered under the Real Property Act 1900 (NSW) granted by KT to Mr Smith on 29 June 2007 for a period of 50 years less two days. Each sublease contained covenants by Mr Smith that the premises would be used only for holiday accommodation or used in the conduct of activities involved in the business of licensing members of the public to occupy those premises on payment of reasonable licence fees. The critical clause for the purposes of the restraint of trade argument is cl 4.3, which provided:

“4.3 NO USE OF ‘THREDBO’

The Sublessee must not use or permit the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in connection with any business carried on by the Sublessee, without the prior written consent of [KT].”

(Emphasis added.)

56 In addition, cl 16.6 provided that KT had an absolute discretion whether or not to grant its consent or to impose conditions on the grant. Relevantly, cl 20 provided:

“20. USE OF PREMISES

(a) The Sublessee and the Sublessee’s Invitees must only use the Premises for holiday accommodation. The only exception to the above is that the Sublessee or the Sublessee’s Invitees may use the Premises for conducting activities involved in the business of licensing members of the public to occupy the Premises on payment of reasonable licence fees. The Sublessee and the Sublessee’s Invitees must not conduct any other business activities in or on the Premises or the Lot.”

(Emphasis added.)

57 In addition, cl 20 went on to provide that the sublessee had to make the demised premises available for holiday letting to members of the public when not occupied by the sublessee (who was limited to occupancy for no more than 26 weeks per annum) (cl 20(d)).

58 The Restraints of Trade Act 1976 (NSW) provides a limited discretion in s 4 for the Court to relieve against what would otherwise be a restraint of trade that was invalid as against public policy in the following terms:

“4 Extent to which restraint of trade valid

(1) A restraint of trade is valid to the extent to which it is not against public policy, whether it is in severable terms or not.

(2) Subsection (1) does not affect the invalidity of a restraint of trade by reason of any matter other than public policy.

(3) Where, on application by a person subject to the restraint, it appears to the Supreme Court that a restraint of trade is, as regards its application to the applicant, against public policy to any extent by reason of, or partly by reason of, a manifest failure by a person who created or joined in creating the restraint to attempt to make the restraint a reasonable restraint, the Court, having regard to the circumstances in which the restraint was created, may, on such terms as the Court thinks fit, order that the restraint be, as regards its application to the applicant, altogether invalid or valid to such extent only (not exceeding the extent to which the restraint is not against public policy) as the Court thinks fit and any such order shall, notwithstanding sub-section (1), have effect on and from such date (not being a date earlier than the date on which the order was made) as is specified in the order.”

(Emphasis added.)

59 This Court can exercise the power that s 4(3) conferred on the Supreme Court of New South Wales as a surrogate federal law picked up by s 79 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth): Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Edensor Nominees Pty Limited (2001) 204 CLR 559 at 591–595 [68]–[80] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ, 600–601 [102] and 606–607 [121] per McHugh J, 638 [217] per Hayne and Callinan JJ.

60 The primary judge found that the respondents were carrying on business in Thredbo and that finding is not in dispute. Indeed, their business involved the letting or licensing of holiday accommodation at the demised premises to members of the public. As noted above, there are three relevant issues arising from cl 4.3, first, whether it is a restraint of trade, secondly, whether it is unreasonable, and thirdly, whether s 4(3) of the Restraints of Trade Act can, and, if so, should save so much of it as the Court thinks fit. We will consider these issues in turn.

KT’s submissions on the lease issues

61 KT argued that the primary judge had been wrong to require evidence that cl 4.3 was the type of clause that a trading society considers necessary as a part of doing business. It contended that restraints such as cl 4.3 were accepted norms and so notorious that they should be the subject of judicial notice. KT submitted that clauses prohibiting individual retailers from using the centre’s name were a commonplace in shopping centre leases. KT contended that the word “Thredbo” was not in the same class as the name of a suburb but was more akin to a name like the brand name of a shopping centre developer. KT argued that the respondents bore the onus of proving facts that the clause was not of a type that was accepted as part of a trading society as part of their establishing that the clause was a restraint. It submitted that the primary judge erred by placing the burden on KT to establish that cl 4.3 was of that nature. KT also contended that the primary judge erred by not identifying any authority to suggest that it was unreasonable for a restraint of trade to protect a person’s distinctive connection or goodwill in an expression exclusively connected to that person, here being the name “Thredbo” in relation to the appellants’ resort. KT argued that it did not matter that the distinctive connection or goodwill was not referrable to the land in the lease in which the restraint was contained. KT asserted that no “relevant” restraint of trade existed in cl 4.3 merely prohibiting the adoption of a name for the purpose of conducting a business from subleased premises that were to be used for holiday accommodation. KT submitted that his Honour erred in failing to construe cl 4.3 as limited to restricting the use of the word “Thredbo” in the name of a business that the sublessee carried on in its capacity as sublessee from the demised premises. It contended that, because the primary judge found that Mr Smith was carrying on a business at Thredbo, that activity was a contravention of cl 4.3.

62 Finally, KT argued that the reasonableness of the protection conferred on its goodwill in the name of “Thredbo” by cl 4.3 should have been weighed by his Honour in applying the Restraints of Trade Act. During the course of the hearing, senior counsel for the appellants handed up the following as their proposed construction of cl 4.3 as it should apply to the respondent pursuant to s 4(3) of that Act:

“The Sublessee must not use or permit the use of the word “Thredbo” as the name of or in order to identify [any business carried on by the Sublessee] from or in connection with the sublet premises without the prior written consent of the company such consent not to be unreasonably withheld”.

(underlined words added by the appellants; bracketed words moved from after “connection with”)

The parties’ submissions on the interaction between cll 4.3 and 20

63 After the Full Court reserved judgment, it invited the parties to address the interaction between cll 4.3 and 20 because that matter had not been previously developed, after having been only briefly mentioned in oral argument. In particular, the Court invited the parties to address how the sublessee could carry on the business of licensing members of the public to occupy the demised premises for at least 26 weeks each year if cl 4.3 prohibited the sublessee from using the word “Thredbo” in connection with that business.

64 The appellants submitted that, if the sublease were read as a whole, the prohibition in cl 4.3 was limited to the use of the word “Thredbo” “in a trade mark or business name sense, not in a geographic sense”. They pointed to many examples of KT’s sublessees whose business names did not include “Thredbo” who advertised their offers of accommodation at Thredbo, including in their given addresses. The appellants said that cl 4.3 could not be read as prohibiting a sublessee informing prospective tenants of a property’s location in the geographic locality of Thredbo. The appellants asserted that there was no practical necessity for a sublessee to use “Thredbo” in or as part of its business name, and that, if it desired to do so, it could seek KT’s consent. They also referred to their fast track reply that pleaded that they did not seek to restrain the use of the word “Thredbo” as a geographic descriptor.

65 The respondents argued that it would be possible for a sublessee to engage KT, as sublessor, to act as the managing agent of the accommodation offered at the demised premises under cl 20(f) and, in those circumstances, KT could not complain that its conduct, as agent of the sublessee, was a breach of cl 4.3. The respondents suggested that the accommodation could be advertised in the window of real estate agency premises at Thredbo with their street address, but without the place name, “Thredbo”. However, they contended that ordinary or practical advertising, in the media or on the internet, would breach cl 4.3 if the full address, including “Thredbo” were given. They argued that, because cl 20(d) did not require the sublessee to advertise the availability of accommodation in the demised premises, there was no inconsistency between cll 4.3 and 20 and that cl 20 did not affect the construction of cl 4.3. They also argued that there was no reason in cl 20, or the sublease as a whole, to read down the broad terms of cl 4.3.

Restraint of trade

66 The meaning of the terms of a commercial contract is ascertained by what a reasonable business person in the position of the parties would have understood those terms to mean. This requires the Court to consider the language used by the parties, the surrounding circumstances known to them and the purpose or object secured by the contract: Electricity Generation Corporation (t/as Verve Energy) v Woodside Energy Ltd (2014) 306 ALR 25 at 33–34 [35] per French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ. Their Honours continued, saying (at 33–34 [35]):

“Appreciation of the commercial purpose or objects is facilitated by an understanding ‘of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context [and] the market in which the parties are operating’. As Arden LJ observed in Re Golden Key Ltd (in rec), unless a contrary intention is indicated, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract a businesslike interpretation on the assumption ‘that the parties … intended to produce a commercial result’. A commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it ‘making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience’.” (footnotes omitted)

67 It is significant that cl 4.3 does not apply to restrict the use of the demised premises. Rather, on its face the clause restricts the sublessee in the manner it carries on any business from any place in the world by prohibiting the sublessee from using the word “Thredbo” in connection with that business. Thus, cl 4.3 is not a restrictive covenant of the kind in Tulk v Moxhay [1848] 2 Ph 774; 41 ER 1143 restricting the sublessee (Mr Smith) in the way in which he may use the land. It is not a covenant about the use of land, far less the demised premises, at all. Rather, it is a restriction on the way in which the sublessee can carry on any business at all merely because the sublessee is in the relationship of tenant and landlord.

68 Whether a restraint is one within the legal doctrine of restraint of trade is determined by having regard to its practical working rather than merely its legal form: Peters (WA) Limited v Petersville Limited (2001) 205 CLR 126 at 134 [14] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ. Some restraints are understood to have no practical operation that bring them within the doctrine. The test for ascertaining whether the restraint falls within that class, and so is outside the operation of the doctrine, was settled in this Court by Heerey J, with whom Miles J and O’Connor J agreed in Australian Capital Territory v Munday (2000) 99 FCR 72 at 93 [105] as being whether it is accepted as part of a trading society in the sense explained by Lord Wilberforce in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd [1968] AC 269 at 335B-D: see Peters 205 CLR at 138 [23]. The Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria assumed that the trading society test should be applied in Specialist Diagnostic Services Pty Ltd v Healthscope Ltd (2012) 305 ALR 569 at 581 [57] per Buchanan, Mandie and Osborn JJA. Lord Wilberforce examined a number of accepted instances where the doctrine did not apply and said ([1968] AC at 335B-D):

“One may express the exemption of these transactions from the doctrine of restraint of trade in terms of saying that they merely take land out of commerce and do not fetter the liberty to trade of individuals; but I think one can only truly explain them by saying that they have become part of the accepted machinery of a type of transaction which is generally found acceptable and necessary, so that instead of being regarded as restrictive they are accepted as part of the structure of a trading society. If in any individual case one finds a deviation from accepted standards, some greater restriction of an individual's right to “trade,” or some artificial use of an accepted legal technique, it is right that this should be examined in the light of public policy.”

(Emphasis added.)

69 KT did not challenge or seek leave to challenge the correctness of Munday 99 FCR 72. KT merely asserted that there was now a class of contract in which a restraint of the kind imposed by cl 4.3 was an accepted restriction on the way a contracting party could carry on a business. KT’s submission that cl 4.3 should be construed as restricting the use of the word “Thredbo” in a business name of a business the sublessee carried on in the demised premises flies in the face of the ordinary and natural meaning of cl 4.3. That clause does not, in terms, limit its prohibition of the use of “Thredbo” to use merely as a part of a business name. Rather, it prohibits use of that name “in connection with any business carried on by the Sublessee”. The words “in connection with” create a very wide ambit in which the prohibition will operate.

70 However, the parties cannot have intended that the clause would be read as prohibiting the sublessee giving “Thredbo” as part of its address. That is because, in cl 20, the sublease contemplated that Mr Smith, as part of a business conducted from the demised premises, could, indeed had to, offer the demised premises to the public as holiday accommodation. A necessary part of such an offer would be the provision of the address of the accommodation in Thredbo. The parties, reasonably, would have understood that the sublessor authorised that use when the sublease was made. That is, by reading the sublease as a whole, including cl 20, there was no need for Mr Smith to seek KT’s consent to using or giving out the address of the demised premises as part of the business of offering them as holiday accommodation.

71 This construction does not reflect either side’s reading of cl 4.3. Yet it flows necessarily from the terms of cl 20 when read as part of the sublease as a whole. Once the parties expressly provided for Mr Smith not only to be able, but to be required, to conduct a business of offering the demised premises as holiday accommodation, it is difficult to understand why cl 4.3 applied to that business at all, as opposed to all other businesses the conduct of which on those premises was prohibited by cl 20(a). After all, the nature of the business that cl 20(a) authorised Mr Smith to carry on was the offer to the public of accommodation in the demised premises at Thredbo.

72 We reject the respondents’ argument that, because cl 20(d) did not require the sublessee to advertise the availability of the accommodation, there was no inconsistency between that provision and cl 4.3 and that cl 4.3 should not be read down by reason of the operation of cl 20. The sublease was a commercial agreement. It required the sublessee to conduct a substantive accommodation business using the demised premises for at least 26 weeks in each year of its 50 year term. It would create a commercially nonsensical result to read the sublease as prohibiting the use of the word “Thredbo” in any advertising of the demised premises as accommodation by the sublessee. And, it would work commercial inconvenience so to read cll 4.3 and 20: Verve Energy 306 ALR at 33–34 [35].

73 Moreover, for the purposes of consideration of cl 4.3 as a restraint of trade, the Court looks to the practical working of the clause: Peters (WA) 205 CLR at 134 [14]. If the practical working of cll 4.3 and 20 were as the respondents argued, the sublessee could only advertise the availability of the accommodation it was leasing in ways that did not use the word “Thredbo”. While the respondents suggested possible scenarios in which that could occur (such as in a real estate agent’s window in Thredbo), the limiting of the sublessee’s promotion of its demised premises to those scenarios demonstrated the commercial inconvenience of that construction.

74 The parties could not reasonably have contemplated that the sublessee, Mr Smith, could conduct such a business without using the word “Thredbo” in connection with it. The location at which the holiday accommodation was to be offered obviously had to be named as “Thredbo”. Moreover, a reasonable person in the position of the parties would have expected that the sublessee was free to advertise the availability of the demised premises in the ordinary way holiday resort accommodation is advertised, including on the internet. That being so, there is no reason to read a limitation into cl 4.3 such as that suggested by KT, that confined its restraint to using the word “Thredbo” in the business name or in order to identify any business carried on by Mr Smith that conformed to the use authorised in cl 20. A reasonable business person in the position of the parties, in light of the sublease’s commercial purpose, the context, and the market in which they were operating, would have understood cl 4.3 to restrain the sublessee’s use of the word “Thredbo” in respect of activities other than those that reflected the, or a, central purpose of the sublease.

75 Accordingly, cl 4.3 did not affect Mr Smith or ThredboNet in the ways KT complained of as a breach. Although the respondents did not challenge the primary judge’s view that Mr Smith was prima facie in breach of cl 4.3 if it were valid, his Honour did not have his attention directed to the effect of cl 20 on the proper construction of cl 4.3 in the context of the subleases as a whole. And, as we have observed above, in this appeal, neither side propounded the construction of cl 4.3 which we consider correct. Because of that construction we are of opinion that Mr Smith did not breach cl 4.3. The clause did not apply to the present dispute. In the circumstances, cl 4.3 must have been intended to prohibit the sublessee from using the word “Thredbo” in a way that created a connection between any other business than providing accommodation that the sublessee might establish or conduct and the business or goodwill of the appellants’ resort known as “Thredbo”.

76 The effect of this construction is partly complementary to KT’s common law right to seek relief in respect of acts or conduct that a sublessee might engage in amounting to passing off, or misleading or deceptive conduct representing the sublessee’s business as that of KT to the extent that it could assert such rights in respect of the word “Thredbo” and the activity or conduct complained of. However, if the sublessee carried on another business, then cl 4.3 prohibits him using “Thredbo” in connection with it, regardless of any relationship that business might have to the demised premises.

77 There was no evidence before the primary judge of how lessees operating businesses in locales such as shopping centres or holiday resorts are permitted to use the developer’s or operator’s name for the centre or resort as part of the lessee’s trading name. A franchisee of, say, a hamburger business in such a location, may wish to distinguish itself by adopting the franchisor’s name with the suffix “at X Centre”. There was no material before his Honour or us to suggest that it is an accepted or necessary part of tenancy leases in shopping centres or resorts that there is a restraint on using the centre’s or resort’s name without the lessor’s permission in or to the effect of cl 4.3.

78 We reject KT’s argument that the primary judge erred by not, in effect, taking judicial notice of some unspecific practice to include restraints like cl 4.3 in commercial leasing arrangements. This is because, first, KT had great difficulty in explaining a rational operation of the limitation in the use of the word “Thredbo” created by cl 4.3. The parties could not have intended that the ordinary and natural (i.e. literal) construction of cl 4.3 would apply even in leases without a clause like cl 20 in the respondent’s lease. That is evident because every business subjected to the restraint was in fact connected to, and likely to operate in, Thredbo. The clause must be read to accommodate that reality, including the ability of the business to use its own address in dealing with the public and suppliers and in advertising its location. It would be extraordinary to find, without cogent evidence of commercial usage, that it was a generally necessary and accepted incident of commercial leases in shopping centres and resort complexes that a lessee trader could not use the name of the centre or resort in any connection with its business without the lessor’s consent which the lessor was at liberty to withhold in its absolute discretion. We are not prepared to infer that such a commercially absurd restriction is reflective of a reasonable and business-like construction of cl 4.3: Verve Energy 306 ALR at 33–34 [35]; Zhu v Treasurer of the State of New South Wales (2004) 218 CLR 530 at 559 [82] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby, Callinan and Heydon JJ. Far less do we accept that construction in respect of the argument as to the doctrine of restraint of trade, that a clause having that effect is an accepted part of the Australian trading society.

79 Secondly, as Buchanan, Mandie and Osborn JJA observed in Specialist Diagnostic 305 ALR at 584-585 [75]-[76], it would be anomalous if the geographic extent of an obligation in a clause that extended a restraint beyond the land retained by the lessor could not be examined by the Courts in order to ascertain whether it was reasonable either as between the parties or in the public interest. Thirdly, their Honours adverted to the difficulties in inferring that a restraint, in certain contexts, was an accepted part of this trading society without evidence (see 305 ALR at 585 [77]–[78]).

80 There will be some contexts where a court can draw such an inference without evidence, as Heerey J explained in Munday 99 FCR at 93 [107]–[108] where he said:

“A common, and important, way of deriving economic benefit from land is the grant of exclusive licences for the conduct of business thereon. Such licences are only of value because of the expectation that other persons will enter upon the land and be customers, but not competitors. So persons gaining admission to the Melbourne Cricket Ground who happen to be caterers would not expect to be able to set up a pie stall in competition with those who have been granted exclusive catering rights by the MCG. Nor would a television station expect to be able to send camera operators into the ground to transmit broadcasts in competition with the channel which has exclusive contractual rights.

It is true that Revolve's contractual rights only extended to material left or abandoned at the Tip. His Honour reasoned that Revolve's rights were therefore not infringed when the appellant persuaded entrants to hand over items to him rather than deposit them – as exemplified by the incident involving the plastic bottles. However, I think looking at the matter from a business viewpoint the ordinary and reasonable expectation of Revolve must have been that people taking rubbish to the Tip (and paying a fee for the opportunity to do so) would leave the material there. This would be, objectively speaking, the commercial genesis and purpose of the contract between Revolve and the appellant.”

(Emphasis added.)

81 Here, the commercial genesis and object of the sublease was to allow the sublessee to conduct the business of offering the demised premises to the public as holiday accommodation at Thredbo as part of a business that included those premises. That context does not suggest, one way or another, how the parties must reasonably have intended that each could use the word “Thredbo” in connection with their respective, and not necessarily wholly complementary, commercial interests in exploiting their business opportunities. Hence, the plenary reach of cl 4.3, and the need to construe it to arrive at a commercially practicable operation for it, demonstrate that a restraint in its literal terms cannot be considered as a commonplace in Australia. The very need to construe the objectively-intended operation of cl 4.3 in the context of the sublease as a whole suffices to explain why the wording of the restraint in cl 4.3 cannot be inferred or treated as being an accepted part of a trading society.

82 It may well be that some other shopping centres and resort complexes have some form of restraint clauses in leases, but those clauses would have to be construed as part of those leases as a whole, in accordance with the ordinary principles of contractual construction. The way in which any such restraint may operate and its validity in its own factual context are not matters that can be assumed without evidence.

83 KT bore the onus of proving that cl 4.3 was an accepted part of the machinery of a trading society. It did not discharge that onus. Accordingly, the doctrine of restraint of trade operates on cl 4.3 and its validity falls to be determined under that doctrine.

84 The practical working of cl 4.3 imposed a restraint of trade on the sublessee. However, given the construction of cl 4.3 at which we have arrived, it does not prevent Mr Smith carrying on a business as he and ThredboNet have or in the ways complained of by KT.

85 Because of the conclusion we have reached on the construction of cl 4.3 when read with the sublease as a whole in the manner a reasonable business person would read it, as explained in Verve Energy 306 ALR at 33–34 [35] and the authorities to which French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ referred, the questions of whether cl 4.3 is an unreasonable restraint or can and should be read down under the Restraints of Trade Act do not arise. However, we are not persuaded that cl 4.3 imposes a reasonable restraint of trade. It lacks any connection to the demised premises or any other reasonable basis connected to the sublessor’s legitimate interests, such as the protection of its goodwill and trading reputation. The plenary restraint in cl 4.3, outside the activities contemplated by cl 20, preventing a sublessee conducting any business giving even its address as Thredbo is unreasonable. In our opinion, cl 4.3 is void at common law, as his Honour correctly held.

Conclusion

86 For these reasons, the appeal must be dismissed with costs.

| I certify that the preceding eighty-six (86) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Siopis, Rares & Katzmann |

Associate: