FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Daebo Shipping Co Ltd v The Ship Go Star [2012] FCAFC 156

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

in admiralty | |

| Appellant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer on or before 14 November 2012 and file short minutes of orders including orders as to costs to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment published today.

2. In the event that the parties are unable to agree any order pursuant to order 1, each party file and serve its written submissions as to the order or orders in dispute on or before 14 November 2012.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

in admiralty | |

WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | WAD 373 of 2011 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | DAEBO SHIPPING CO LTD Appellant

|

AND: | THE SHIP GO STAR Respondent

|

JUDGES: | KEANE CJ, RARES & BESANKO JJ |

DATE: | 7 NOVEMBER 2012 |

PLACE: | PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

1 In June 2007, Go Star Maritime Co SA, as owners of the respondent ship, Go Star, entered into a time charter of her for 36-40 months with Breakbulk Marine Services Ltd (BMS) for a period of 36-40 months plus or minus one month at charterers option (the head charter). The head charter was effected on the 1981 Absatime New York Produce Exchange Form (the 1981 NYPE form) and contained extensive rider clauses. On 14 July 2007, BMS sub-chartered the ship to Bluefield Shipping Co Ltd (Bluefield) for a period of 23 to 25 months at Bluefield’s Option (the Bluefield sub-charter). The Bluefield sub-charter was on substantially back to back terms, for present purposes, with the head charter.

2 Next, on 27 July 2007, Bluefield entered into a further sub-charter of Go Star with the appellant, Daebo Shipping Co Ltd (Dabeo), a company incorporated in South Korea (the Daebo sub-charter). The Daebo sub-charter was for the same period, and on substantially back to back terms, as the Bluefield sub-charter.

3 In January 2008, Daebo entered into a sub-charterparty with Daeyang Shipping Co Ltd (Daeyang). In December 2008, Daebo entered into another time sub-charter with another South Korean company, Nanyuan Shipping Co Ltd (Nanyuan). Nanyuan is sometimes referred to as NASCO. The Nanyuan sub-charter provided that delivery of the ship to Nanyuan was to occur in Chinese territorial waters near Shanghai.

4 On 3 January 2009, Daeyang redelivered the ship to Daebo at Shanghai to enable it to be delivered to Nanyuan. A certificate of delivery was executed by the master of the ship and a surveyor which recorded that delivery by Daebo to Nanyuan occurred on 3 January 2009. A day later, Daebo issued an invoice for US$303,436.60 to Nanyuan for the first hire payment and for the value of the bunkers.

5 Between 3 January and 8 January 2009, the ship sailed from Shanghai to Fangcheng. The master had been instructed by Nanyuan to load a cargo at Fangcheng for delivery to Angola. Go Star proceeded in this way in accordance with instructions provided by Nanyuan by email on 1 January 2009.

6 By this time the head charterer, BMS, had fallen into arrears of payment of hire to the owners under the head charter. Clause 5 of the head charter provided for the withdrawal of the ship by the respondent should BMS fall into arrears of hire payments. Before Nanyuan had paid Daebo’s invoice for the hire and the bunkers, the owners’ agent, Evalend Shipping Co SA (Evalend), advised Nanyuan that the owners intended to exercise their rights to withdraw the ship under the head charter.

7 On 8 January 2009, Nanyuan purported to cancel or withdraw from its sub-charterparty with Daebo. Nanyuan, having received the above and other communications from the owners’ agent, did not pay the invoice furnished by Daebo, and arranged an alternative carrier for its cargo. Nanyuan commenced loading its cargo onto another vessel.

8 On 13 January 2009, Nanyuan emailed Daebo “reconfirming” its position and explaining that its decision was the result of a notice from Evalend to the effect that the owners proposed to exercise their rights under a lien to demand payment of sub-hire from Nanyuan. On this basis Nanyuan claimed that the ship had never been lawfully delivered by Daebo because it had not been “lawfully ready in all respects without any restriction”.

9 On 15 January 2009 the owners withdrew the ship from BMS’ service and on 16 January 2009 they chartered her directly to Medstar Lines Inc (Medstar). Medstar ordered Go Star to sail to Albany, Western Australia.

10 On 29 January 2009 the ship arrived at Albany and Daebo demanded the redelivery of the bunkers. The owners refused the demand and credited the value of the bunkers as an offset against BMS’ unpaid hire.

the issues at first instance

11 Daebo commenced proceedings in rem against Go Star in the Federal Court claiming damages in conversion and detinue in respect of the ship’s bunkers. The owners were named in the writ as the relevant person and duly entered an appearance. The proceedings then continued as an action in personam against the owners and in rem against the ship. Daebo also claimed damages in respect of the loss of hire under the sub-charterparty and the loss of payment for the bunkers on the ground that the owners had unlawfully interfered with its contractual relations with Nanyuan.

12 The owners contended that Daebo’s claim in conversion and detinue must fail because it had no title in the bunkers at the time of the alleged conversion, that title having passed from it on delivery of the ship to Nanyuan on 3 January 2009. As to Daebo’s claim for damages on the ground of unlawful interference with contractual relations, the owners contended that the alleged interference occurred in China and Chinese law does not recognise that tort.

13 The learned primary judge resolved these issues in favour of the owners. The primary judge held that Daebo had no right to the bunkers, having disposed of title to the bunkers on the 3 January 2009 when the ship was delivered to Nanyuan, pursuant to the Nanyuan sub-charter. Further, his Honour held that Chinese law applied to the putative interference with contractual relations by the owners, and under Chinese law the owners’ conduct was not wrongful.

14 Before we discuss the arguments agitated by the parties on the appeal to this Court, we will summarise the facts in greater detail. The primary facts as found by the primary judge are not in dispute; but there is a dispute as to whether the primary judge erred in regarding the owners’ communications with Nanyuan as having their effect on Nanyuan in China rather than in Singapore. After setting out the primary facts we will summarise the reasons of the primary judge before turning to consider the arguments of the parties.

THE FACTS

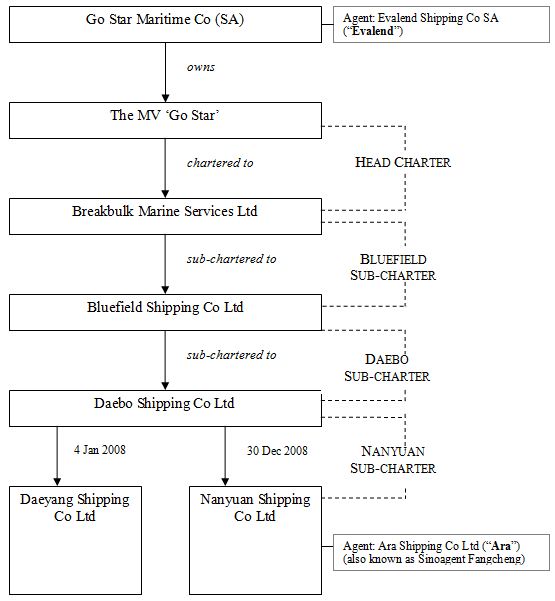

15 The following diagrammatic representation of the chain of charter parties may assist an understanding of the issues addressed by the primary judge:

16 Each of these time charters was in the 1981 NYPE form with substantially similar back to back rider clauses but with differing charter rates and charter periods. The relevant portions of the clean recap read as follows:

- Delivery : dlosp CJK , ATDNSHINC

- Laycan: 2/6 JAN , 2009 LT

…

- HIRE PAYABLE EVERY 15 DAYS IN ADVANCE. SUBSEQUENT HIRES ALSO IN ADVANCE EVERY 15 DAYS. FIRST HIRE + BOD value to be PAID TO OWNERS nomi bank W/IN 3 BANKING DAYS OF VESSELS DELIVER TO CHRTS

…

- BUNKER CL: BUNKERS ON DELIVERY ABT 600-850 MTS IFO AND ABOUT _60-85 MTS MGO

- BUNKERS ON REDEL TO BE APPROX SAME QTY AS ON DELIVERY. PRICES BOTH ENDS USE _203__/MT

FOR IFO AND USD _450 __MT FOR MGO

- BOR to be abt the same quantities as on delivery. chrts have the right to deduct value of BOR from last sufficient charter hire

…

- ARBITRATION IN LONDON/ENGLISH LAW TO APPLY

- OTHERWISE AS PER ows’ btb CP WITH LOGICAL/MINOR ALTS AS PER MTF

17 The Daebo sub-charter with Nanyuan contained the following clauses in the NYPE form:

Duration: The Owners agree to let and the Charterers agree to hire the vessel from the time of delivery for … (lines 27-28)

Delivery: Vessel shall by placed at the disposal of the Charterers on dropping last outward sea pilot, one safe port, world wide, any time day or night, Sundays and Holidays included. (Owners will revert with exact ranges 30 days before delivery.) (Emphasis in original) (lines 34-37)

…

2. The Charterers, while the vessel is on-hire, shall provide and pay for all the fuel except as otherwise agreed…

…

31. Charterers to take over and pay together with first hire payment bunkers upon vessel’s delivery. Reverting with quantities/prices. On redelivery bunkers same quantities and same price both end.

18 Clause 18 of the 1981 NYPE forms in each charter is in the following terms:

The Owners shall have a lien upon all cargoes and all sub-freight for any amounts due under this Charter, including general average contributions, and the Charterers shall have a lien on the ship for all monies paid in advance and not earned, and any overpaid hire or excess deposit to be returned at once. Charterers will not suffer, nor permit to be continued, any lien or encumbrance incurred by them or their agents, which might have priority over the title and interest of the Owners in the vessel.

19 Some of the terms of the sub-charter between Daebo and Nanyuan in addition to those contained in the 1981 NYPE form contained in a clean recap set out at [16] were summarised by the primary judge as follows:

The terms of the Nanyuan sub-charterparty are set out in a clean recap by email from Nanyuan’s agent, Ara Shipping Co Ltd. The cargo under the Nanyuan sub-charterparty was to be carried from Fangcheng in China to Angola, with re-delivery in Angola. The clean recap email provided for the following relevant terms:

(a) Delivery: “dlosp CJK, ATDNSHINC” (delivery: [dropping] last outward sea pilot Chang Jiang Kou [a port near Shanghai] any time day or night Sundays and holidays included).

(b) Hire payable every 15 days in advance. Subsequent hires also in advance every 15 days. First hire [+] bunkers on delivery value to be paid to [Daebo’s] nominated bank within 3 banking days of the vessel’s delivery to Nanyuan.

(c) Bunkers on delivery were about 600-850 metric tonnes IFO and about 60-85 metric tonnes MDO.

(d) Bunkers on redelivery to be approximately the same quantity [as] on delivery. Prices used on both ends USD 230/MT for IFO and USD 450/MT for MDO.

(e) Bunkers on redelivery to be about the same quantities as on delivery. Charterers have the right to deduct value of Bunkers on redelivery from last sufficient charter hire.

20 On 1 January 2009, Ms Jane Chen of Nanyuan sent an email to the master of “Go Star” which welcomed the master and crew of the ship into the time charter fleet of Nanyuan’s principal and advised that the voyage would be controlled and operated by Nanyuan. The email advised that Ms Chen was “the person in charge”. The email informed the master of the essential terms of the Nanyuan sub-charter, and issued the master of the ship with a number of detailed instructions. These included an instruction that the master should, during the “entire charter” proceed at full speed with utmost dispatch unless otherwise advised. The master was also instructed to report on, among other things, the remaining bunkers on board, and when the ship switched from heavy oil to diesel oil during manoeuvring. The email was sent from a Chinese email address.

21 Ms Chen’s email was copied to Captain Hu of Nanyuan who was evidently located in Singapore, and who had a Singaporean internet service provider domain address. There was no direct evidence of Captain Hu’s role within Nanyuan or of the relationship between Captain Hu and Ms Chen. However, Ms Chen’s email instructed the master that for commercial reasons all messages at the load port sent to the cargo shipper and local agent should state that Seaweb International Pte Ltd was the carrier or disponent owner and should not mention the email address of Nasco. Captain Hu’s email address began with the word “seaweb”. Moreover, Ms Chen’s email had instructed the master to copy all emails to Captain Hu’s email address.

22 On 2 January 2009, Mr Kim of Daebo sent an email to Ara Shipping, the agent of Nanyuan, advising that the ship would be delivered at Shanghai on or around 2 or 3 January 2009, and asking that the message be taken as final delivery notice.

23 Evalend was fleet manager and agent of the owners. Evalend carried on business in Greece. Mr Nicholas Pantelias acted on its behalf. Mr Pantelias sent an email dated 2 January 2009 addressed to Ms Jane Chen’s email address in China in the following terms:

This is Evalend Shipping Co SA, managers of the Head Owners of MV GO STAR which we understand has been sub time chartered to your goodselves. We also understand that you are to take delivery of the vessel upon dropping the last outward pilot Shanghai, CJK pilot station and this delivery is now imminent.

Regret to advise you that Head Charterers are very seriously in arias [sic] of hire payments and Owners are considering all their options including but not limited to the withdrawal of the vessel from Head Charterers service. In the meantime we advise you that Head Owners Messrs GO Star Maritime Company SA hereby exercise their rights under the head charter in respect of lien and kindly request you not to proceed with any payment under your sub-charter and you are being put on notice that should you elect to ignore this notice you may be called upon to pay such sums twice over.

As you can appreciate Head Owners are also vested with a lien on cargo and such right will be exercised in due course as they are not at all minded to perform a voyage under any bill of lading without being certain of hires being paid punctually and in advance.

Please be guided accordingly and kindly acknowledge receipt of this notice.

24 That email was also sent to Captain Hu of Nanyuan in Singapore. Captain Hu then sent an email, dated 3 January 2009, to Evalend in which he said that he had received Evalend’s message to Ms Chen and asked for the telephone number of the person in charge at Evalend. Mr Pantelias’ assistant responded by email to Captain Hu’s email stating that Mr Pantelias was the person in charge and would telephone Captain Hu. The email also included Mr Pantelias’ mobile telephone number. Shortly after receiving that email, Captain Hu telephoned Mr Pantelias’ mobile number but was unable to speak to Mr Pantelias. Mr Pantelias then telephoned Captain Hu by using the number recorded on his mobile telephone. During the telephone conversation, Captain Hu said that he intended to investigate whether Nanyuan could find an alternative carrier for his cargo. We pause here in the narrative of the facts to note that the circumstance that these discussions occurred between Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu might be thought to indicate that it was Captain Hu, rather than Ms Chen, who was the person in charge within Nanyuan in relation to the contractual relationships between Nanyuan and Daebo.

25 After the telephone call, Mr Pantelias sent the following email to Captain Hu at his Singapore email address:

We refer to our phone conversation a short while ago and we simply wish to ensure that our message is read once again very carefully and to respectfully urge you to take legal opinion before you take any decisions and you act upon them. In our message we advised you that we are considering with the physical owners their options including but not limited vessel’s withdrawal from Head charterer’s service. The vessel however has not been withdrawn and if you proceed and throw up your charter with your Owners you may be held in repudiatory breach of your charter and expose your selves to damages. We have simply asked you to withhold payments under your charter. In other words our last must be seen as a notice of lien and no more.

We reiterate that we have nothing to share with your good selves and we regret that we have to deal in this situation which of not of our making.

Once again we wish to ensure that our suggestions are put forward with utmost respect and we wish to ensure that we do not run into any conflict of interest between ourselves and be on the same side of the fence.

26 On 3 January 2009, a certificate evidencing the redelivery of the ship by Daeyang to Daebo under the Daeyang sub-charter was signed by the master and a surveyor.

27 On the same day, the master and the surveyor also executed a certificate of delivery evidencing the delivery of the ship by Daebo, as disponent owner under the Nanyuan sub-charter to Nanyuan. The position of delivery recorded on the certificate is dlosp [dropping last outward sea pilot] Shanghai. The time for delivery is recorded on the certificate as 20:30 hours local time on 3 January 2009. On 6 January 2009, Daebo issued an invoice to Nanyuan dated 4 January 2009 for the sum of USD303,436.60 for the payment of the first 15 days hire and bunkers on delivery.

28 On 7 January 2009, Mr Pantelias sent another email addressed to both Ms Chen and Captain Hu to Nanyuan’s email address in China. Apparently the email was not sent to Captain Hu’s Singapore address. That email read relevantly:

Ahead of vessel’s arrival at her intended loading port and whilst it is repeated that the vessel has not been withdrawn from head charterers’ service we reiterate that the head charterers are now very seriously in arrears of their hire payments as no hire has been paid since 21st December and the daily hire rate is US$27,000.

In the circumstances you are kindly requested not to proceed with any payments of any sums under your charter as you may be called upon to pay twice over such sums.

Please acknowledge receipt of this message.

29 By 8 January 2009, Go Star had reached Fangcheng and was awaiting instructions as to the loading of her cargo. On that day the master sent an email to various parties which stated:

The charterers “NASCO” just replied to my phone call and advised me “to check with my owners as they cancelled the vessel”.

Kindly advise whether I should drop the anchor waiting for instructions.

30 A short while later, on 8 January 2009, the master sent an email to all of Mr Kim of Daebo, Daeyang, Bluefield (Felicia), BMS and Evalend, which stated relevantly:

FYI: Sub-charterer’s agents at Fangcheng advised master this morning, verbally, that “another vessel already loading our cargo”.

31 Also on 8 January 2009, Ara Shipping (as agent for Nanyuan) sent an email to the master, stating that its client was withdrawing from the Nanyuan sub-charter. The email stated as follows:

Dear Capt

Pls kindly be advc tt our client had instruct us cancel the agency appoint for yr vsl, bcz shipper had choice another vsl loading cargo. Any question pls feel free let me know.

32 On 8 January 2009, Ara Shipping, as agent for Nanyuan, sent an email to Daebo, which stated relevantly:

[W]ithout prejudice

As chtrs have send our declaration to Owners/Deabo[sic] as per REF: 110552-HU 03-01-2009/13:15:39 as result of a notice from head owners as per “exercise their rights under the head charter in respect of lien and kindly request you not to proceed with any payment…”, not yet received any reply to verify the lawful delivery of the subject vessel per CP dd 1-1-2009 before laycan expires, and Charterers would like to exercise its rights to withdraw the Charter as validity of performance of this CP is in vain, and ship has not been ready in all respects to load cargo for intended voyage as indemnity of lien risk and cooperation by head charterers/owners could not be available with full guarantee. Charterers reserve all rights to hold Owners responsible for all losses and damages to this failure of COP due to NON-performance of the Owners.

33 On 9 January 2009, Mr Pantelias sent an email addressed to Captain Hu at Nanyuan’s email address in China. The email stated:

Dear Cpt Hu,

Re: Go Star

We refer to your call a short while ago and our formal messages herebelow.

At your request we reconfirm that head charterers have not paid any hires and they are seriously in arrears of hire payments. Consequently our notices can not be withdrawn at present.

As promised should the situation changes[sic] we will not fail to notify you and ensure our notification is attended without any delay. In the meantime we wish you a nice weekend.

Best Regards

Legal and Claims Department

Evalend Shipping Co. S.A.

(as Agents to Head and physical owners)

34 The “formal messages” to which Mr Pantelias referred were his email messages of 2 January 2009 and 7 January 2009 to Ms Chen.

35 On 13 January 2009, the master of the ship sent an email to Daebo (and the other disponent owners) which stated relevantly:

Further to my msgs please be advised that after phone contact with disp. owners messrs “Daebo” was advised that sub-charterers messrs NASCO wish to cancel next employment.

36 Ara Shipping sent another email to Daebo on 13 January 2009. It was relevantly in the following terms:

This is to reconfirm Charterers’ position to Owners/Deabo[sic] Shipping to remain the same as our notice on 8th Jan 2008 to terminate the CP, not to take delivery of the subject vessel, because several notices received from head owners as to deter CP performance as per “exercise their rights under the head charter in respect of lien and kindly request you not to proceed with any payment…”, and reply we requested from Owners failed to prepare and verify lawful delivery of the vessel per CP dated 30th Dec 2008. thereafter Charterers not able to take delivery of the vessel before laycan expired because that subject vessel is NOT lawfully ready in all respects without any restriction, and vessel is also rejected by Shipper and its insurer due to such event (Please find attached notice from Cargo insurer). Charterer hereby certainly confirm again that lawful delivery has NEVER been in place, and the notice to termination of the Charter Party on 8th Jan 2008 remains the same. Charterers reserve all rights to hold Owners responsible for all losses and damages to this failure of CP due to NON – performance of the Owners.

37 On 15 January 2009, the owners issued a notice under cl 5 of the head charter between the owner and BMS, withdrawing the ship for the non-payment of hire. At the time of withdrawal, Go Star had not been loaded with cargo and was in Chinese territorial waters.

38 On 16 January 2009, the owners issued an invoice to BMS whereby it acknowledged redelivery of the bunkers and gave credit for the bunkers against the amount of the unpaid hire.

39 In the meantime, the owners had entered into another charterparty in respect of the ship with Medstar for the carriage of a cargo of wheat from Albany in Western Australia to Yemen.

40 On 17 January 2009, Go Star sailed from Fangcheng to Singapore, en route to Albany. On 21 January 2009, the ship left Singapore bound for Albany, with an estimated date of arrival of 29 January 2009.

41 On 22 January 2009, Daebo sent an email to the owners demanding that the owners deliver up the bunkers to it when the ship was in Albany. The email stated relevantly:

We note that the master appears to be taking orders from the agents of a company named “Medstar Lines Inc”, which is not a party to whom we have chartered the vessel. If the original charterparty chain (ie Evalend – BMS – Bluefield – Daebo) is still intact then the owners have no business taking orders from Medstar. We suspect, however, that the vessel has been withdrawn from BMS and is now chartered out by Evalend to Medstar. If that is the case, could Bluefield please inform us on what basis, if any, they are still involved in the chartering of the vessel?

We look forward to prompt replies from relevant parties to clarify the situation. In the meantime, we reserve all our rights, including but not limited to the right to claim back overpaid hire and for bunkers ROB, which presumably are being burned up by the vessel in violation of our ownership rights. We would also point out that if our charterparty with Bluefield is still intact (a point on which we cannot express a view until we have received some answers from others) then the vessel is currently sailing to Albany without any orders to do so from us, and therefore disponent owners are in breach. If such a breach is persisted in it will amount to a repudiation of the charter, if there has not already been a repudiation.

Awaiting owners’ prompt response.

42 On 29 January 2009, Mr Kim of Daebo sent the following email to Evalend, marked for the attention of “Mr Nicolas”:

We refer to our message dated 22 January 2009. In that message we expressed our concern that the Go Star was sailing to Albany, Western Australia without any orders to do so from Daebo Shipping Co Ltd (“Daebo Shipping”).

On board the vessel is 775 metric tonnes of fuel oil and 72 metric tonnes of diesel oil which is the property of Daebo Shipping. The fuel and diesel oil was supplied to the vessel in accordance with Daebo Shipping’s obligations under its charterparty with Bluefield Shipping Co Ltd dated 27 July 2007. The quantities of fuel and diesel oil have been calculated by reference to the amount of fuel oil and diesel oil which was onboard the Go Star when it arrived at Fancheng on 8 January 2009. We demand that the above referred amounts of fuel oil and diesel oil are delivered to Daebo Shipping when the vessel is at Albany. Please confirm by return that Head Owners will do so. We calculate that the value of the fuel oil is USD407,650 and the value of the diesel oil is USD58,176.

THE REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

43 Daebo contended that there was no true delivery of the ship to Nanyuan in that Daebo had made the ship available to Nanyuan but the latter had not taken delivery. His Honour rejected that contention. He said:

68 I do not accept Daebo’s contention. The words “charterers to take over and pay…bunkers upon vessel’s delivery” in cl 31 of the back-to-back charterparty are the important words in the proper construction of the Nanyuan sub-charterparty. In my view, those words are to be construed as manifesting the parties’ intention that on delivery of the ship, property in the bunkers passes to the charterer, with the charterer incurring an obligation to pay for the bunkers. In the context of this case by reasons of the express provisions in the recap email, the obligation to pay for the bunkers was to be performed within three banking days of delivery of the ship.

69 Nor, in my view, do the words of cl 31, or any other provision of the Nanyuan sub-charterparty, delay the passing of property in the bunkers to the charterer until the charterer pays for the bunkers.

44 The primary judge regarded the agreement in cl 31 of the sub-charterparty that the charterer is “to take over” the bunkers “upon delivery” as an agreement that, upon delivery of the ship, the charterer is to acquire the property in the bunkers: The Saint Anna [1980] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 180 (Saint Anna).

45 His Honour noted, there was no temporal interval contemplated by cl 31 between the “taking over” of the bunkers and delivery of the ship; the words of cl 31 provide for the taking over of the bunkers “upon delivery”. His Honour reasoned that he would have expected to see a provision expressly stating that a charterer would retain property in the bunkers until payment had been made for the bunkers if that had been the intention of the parties.

46 The primary judge also rejected Daebo’s claim for damages for wrongful interference with its contract with Nanyuan. That claim had been advanced on the basis that the owners had unlawfully interfered in the contractual relations between Daebo and Nanyuan by persuading Nanyuan to breach its obligations under the Nanyuan sub-charter. Daebo contended that the owners were aware of the terms of the Nanyuan sub-charter and, in that knowledge, persuaded Nanyuan not to pay the monies due under that sub-charter and to repudiate its obligations under the Nanyuan sub-charter. The primary judge accepted these contentions. In this regard, his Honour made the following findings:

91 …[T]he defendant was, through Mr Pantelias, at all material times, aware of the existence and terms of the Nanyuan sub-charterparty. This is to be inferred from the fact that the Master of the ship advised Mr Pantelias to that effect and from the terms of the emails which Mr Pantelias sent to Ms Chen and Captain Hu. Also Mr Pantelias admitted this in cross-examination.

92 Secondly, in communicating with Ms Chen and Captain Hu, it was Mr Pantelias’ intention at all material times, to prevent Nanyuan from loading the cargo in Fangcheng. Mr Pantelias said this at [60] of his witness statement. Although Mr Pantelias says that he was concerned that innocent third parties might become involved in a dispute that was not of their making, I find that this was not Mr Pantelias’ only motive. I find that a more significant motive was that it would be to the defendant’s commercial advantage to withdraw the vessel under the head charterparty whilst it was in port and unloaded, so that it could immediately be chartered under a new charterparty to a third person.

47 Daebo advanced its claim on the premise that Australian law applied in relation to this cause of action. The respondent contended that the respondent’s allegedly tortious conduct occurred in the People’s Republic of China (China).

48 Mr Chen Yusheng, an expert in Chinese law, gave evidence, which his Honour accepted, that the law of China does not recognise the tort of unlawful interference in contractual relations. Accordingly, the impugned conduct was not actionable in Australia because the impugned conduct was not actionable under the law of the place of the putative tort. See Regie Nationale des Usines Renault v Zhang (2002) 210 CLR 491.

49 In this regard, the primary judge held that the events alleged to constitute the tort of unlawful interference took place in China. His Honour made this finding on the basis that Ms Chen, the person in charge on behalf of Nanyuan, was located in China, and the email communications by Mr Pantelias were acted upon by Ms Chen in China in respect of a ship then located in Chinese territorial waters.

50 His Honour explained his approach to the location of the place of the putative tort as follows:

93 It is now necessary to determine the place of the tort alleged by Daebo.

94 In the case of Voth v Manildra Flour Mills Proprietary Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 538 at 568, Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson, and Gaudron JJ observed as follows:

In The "Albaforth" it was said by Ackner L.J. and by Robert Goff L.J. that it had been held in Diamond that the substance of the tort of negligent misstatement is committed where the statement is received and acted upon. That is accurate so far as it reflects the facts considered in that case. But there is not and cannot be any such general rule, for a statement may be received in one place and acted upon in another. And The "Albaforth" provides no basis for a conclusion that it is the place where the statement is acted upon which determines the place at which the statement was made. That place may have no connection at all with the place where the statement was initiated or the place where it was completed. And the place where it is acted upon may be entirely fortuitous.

If a statement is directed from one place to another place where it is known or even anticipated that it will be received by the plaintiff, there is no difficulty in saying that the statement was, in substance, made at the place to which it was directed, whether or not it is there acted upon. And the same would seem to be true if the statement is directed to a place from where it ought reasonably to be expected that it will be brought to the attention of the plaintiff, even if it is brought to attention in some third place. But in every case the place to be assigned to a statement initiated in one place and received in another is a matter to be determined by reference to the events and by asking, as laid down in Distillers, where, in substance, the act took place.

95 These observations were made in relation to the tort of negligent misstatement. However, it is apparent from the High Court's observations that in seeking to determine where, in substance, a tort was committed, each case must be considered in the context of its own facts. This is apparent, for example, by the acknowledgement of the High Court that in locating the locus delicti in relation to the tort of negligent misstatement, the place where the statement is relied upon, may or may not be significant, depending upon the circumstances.

51 His Honour, having outlined his approach, went on to make the following important findings of fact at Reasons [96] – [103]:

96 In my view, the events relied upon as comprising the tort of unlawful interference by the defendant with contractual relations between Daebo and Nanyuan, alleged by Daebo took place, in substance, in the People’s Republic of China. I have come to that view for the following reasons.

97 First, at the heart of Daebo’s complaint is that the defendant by Mr Pantelias’ communications with Ms Chen and Captain Hu, persuaded Nanyuan to breach its obligations under the Nanyuan sub-charterparty. Accordingly, in this case, the place where the communications were made is an important consideration in locating the place of the tort alleged.

98 In this regard, the following considerations are relevant. The person in charge on behalf of Nanyuan was Ms Chen. The telephone number which Ms Chen provided in her email of 1 January 2009 to the Master welcoming the “Go Star” to the Nanyuan fleet was a telephone number for Nanking in China. In that email Ms Chen directed that communication with her office should take place by email or fax. To that end, a Chinese email address and Chinese fax number were given. I infer, therefore, that Ms Chen was located in China. Mr Pantelias addressed his email communications to Ms Chen at the email address in China, provided by Ms Chen. I find that the email communications by Mr Pantelias were directed to Ms Chen in China. On the basis of the observations of the High Court in Voth, I find that the defendant’s impugned statements seeking to persuade were made, in substance, in China.

99 A further consideration in determining, in substance, the location of the tort alleged, is the fact that the communications were made by Mr Pantelias with the intention that they be relied upon and acted upon by Ms Chen in China in respect of a ship which was in territorial waters in China. That is, Mr Pantelias wanted to bring about a consequence in China. That consequence was to procure that the “Go Star” was not loaded in Fangcheng. I infer from the fact that “Go Star” was not loaded in February that Mr Pantelias’ statements had the intended consequence of persuading Ms Chen to withhold the loading instructions in respect of the “Go Star”. I find that it was Ms Chen who acted on Mr Pantelias’ statements because she was the person in charge.

100 In my view, this is not a case where reliance on the impugned communications occurred at a place which was fortuitous. I find, therefore, that the fact that the communications were acted on in China, in respect of a ship located in Chinese territorial waters, is a further factor which also militates in favour of finding that, in substance, the tort alleged was committed in China.

101 Another factor which militates in favour of finding that the tort alleged was committed in China is that it was Mr Pantelias’ objective to prevent the performance of an act, namely the loading of the “Go Star”, which was otherwise to be performed in the territorial waters of China. The non performance of this act, is also at the heart of the interference with contractual relations complained of by Daebo.

102 The emails to Captain Hu and the telephone conversations between Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu should be regarded as communications made in Singapore because I infer that Captain Hu was in Singapore. However, I place little weight on those communications in seeking to locate the place where the tort alleged, in substance, occurred, because it was Ms Chen and not Captain Hu who was the person in charge in relation to the Nanyuan charterparty.

103 It follows that I find that the events comprising the tort alleged, in substance, took place in the People’s Republic of China. Mr Chen Yusheng has deposed that the tort known as unlawful interference with contractual relations in Australian law is not recognised under the law of the People’s Republic of China. It follows that the defendant’s conduct relied upon by Daebo in support of its claim for unlawful interference in contractual relations, is not actionable in China. It, also, follows that, on the application of the double actionability rule, the defendant’s impugned conduct is not actionable in Australia.

52 It may be noted here that a substantial argument advanced on behalf of Daebo is that the primary judge had no sufficient evidentiary basis for his conclusion that Ms Chen, and not Captain Hu, was the “person in charge” or decision-maker on behalf of Nanyuan in respect of its contractual relations with Daebo. If the decision-maker was Captain Hu, or indeed some other unidentified person or persons, then the owners’ reliance on Chinese law as the place of the tort would not avail the owners because Australian law would apply in default of the law of some other place; the owners’ pleaded case being tied exclusively to the law of China as the lex loci delicti. The respondent had not sought to plead or prove a case that the law of Singapore differed from the law of Australia in relation to interference with contractual relations.

53 We turn now to the submissions made by Daebo in support of its appeal and the counter-arguments of the owners.

APPELLANT’S SUBMISSIONS

54 Daebo argues that the primary judge ought to have found that, when the ship was placed at Nanyuan’s disposal on 3 January 2009, Nanyuan did not “take over” the ship and the bunkers. It contends that this conclusion follows from the facts that Evalend, for the ship owner, emailed Nanyuan on 2 January 2009 requesting that Nanyuan refrain from making payment under the Nanyuan sub-charter; that Captain Hu of Nanyuan investigated on 3 January 2009 whether Nanyuan could find an alternative carrier for his cargo; that Ara for Nanyuan sought clarification from Daebo on 3 January 2009 as to the possible withdrawal of the ship by the ship owner; and that the master requested, from 3 January 2009, sailing instructions from Nanyuan and none were received.

55 Daebo submits that from 3 January 2009 until 15 January 2009, on which date the ship was withdrawn by the owners, Daebo remained the owner of the bunkers. In particular, Daebo contends that the words in cl 31 of the Nanyuan sub-charter, “charterers to take over and pay … bunkers upon vessels[sic] delivery” were not the provisions governing the passing of title to the bunkers. Rather, the relevant provision was to be found in the clean recap. This was said to require that Nanyuan pay Daebo for bunkers and hire by payment into its nominated bank account within three banking days of the ship’s delivery. Daebo argues that “delivery” did not ever occur in accordance with the clean recap.

56 On the alternative assumption that the wording in the clean recap does not displace or override the relevant wording in clause 31 of the Daebo sub-charter, Daebo submits that, on the proper construction of the phrase “take over and pay … upon delivery” in clause 31 of the Daebo sub-charter, for a transfer of title to occur, there had to be a discharge of the composite obligation to “take over and pay” or, at a minimum, to “take over” the ship. Daebo submits that the words “take over” are not the language of an instantaneous transfer, but connote some form of positive conduct on the part of Nanyuan.

57 Daebo submits that the relevant interference with the contractual relations between Daebo and Nanyuan was effected by communications from Mr Pantelias to Captain Hu in Singapore rather than to Ms Chen in China. Ms Chen’s role, Daebo contends, was merely mechanical: she did not act on Mr Pantelia’s emails other than to forward them to Captain Hu. The material conversations occurred between Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu.

58 Daebo argues that, at the highest for the owners, Ms Chen represented herself as the “person in charge” only in relation to the operation of the ship, not the contractual relations under which those operations occurred. The communications concerning the withdrawal of the ship and finding a substitute vessel for the cargo occurred between Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu. As those communications were found to have occurred in Singapore, Captain Hu, the relevant actor who was influenced by Mr Pantelia’s conduct, was in Singapore even though the consequences of that conduct occurred in China.

59 On this basis, Daebo contends that the alleged tort occurred in Singapore. In the alternative, Daebo submits that the respondent did not discharge its burden of proof in establishing the place of the putative tort.

OWNERS’ SUBMISSIONS

60 The owners contend that the primary judge correctly concluded that the ship was delivered by Daebo to Nanyuan on 3 January 2009 under cl 31 of the charterparty. This conclusion is said to follow from the facts that the master and surveyor executed a certificate of delivery on 3 January 2009; that delivery to Nanyuan on 3 January 2009 is consistent with the ship having been re-delivered to Daebo on the same day by Daeyang; and that the ship proceeded in accordance with Nanyuan’s instruction communicated on 1 January 2009. Importantly, Daebo’s own invoice claimed payment of hire and for the bunkers on the footing that delivery had occurred.

61 The owners observe that Daebo’s submission that title to the bunkers passes only on payment is inconsistent with the express wording of clause 31 which means that Nanyuan is to take over the bunkers “upon delivery” which, in turn, means making the ship available to the sub-charterer at the relevant port. The ship was made available to Nanyuan on 3 January 2009. The phrase “take over” in clause 31 of the NYPE charterparty is said to reflect the commercial reality that a ship will generally be delivered with bunkers already on board. The charterer is obliged to accept or “take over” those bunkers in return for payment. It cannot take over the ship to the exclusion of the bunkers. Taking over the bunkers is an inevitable consequence of delivery of the ship for the bunkers are regarded as part of the ship: Scandinavian Bunkering AS v The Bunkers on Board the Ship FV Taruman (2006) 151 FCR 126.

62 As to Daebo’s claim for damages for interference with its contractual relations, the owners contend that the email from Mr Pantelias to Captain Hu in Singapore of 2 January 2009 set out at [25] did not request that Nanyuan withhold payments on the basis of the respondent’s purported lien. This email to Captain Hu was simply a warning about the possible consequences if payments were made to Daebo. The relevant communications were, it is argued, those of 2 January 2009 and 7 January 2009 from Evalend and Mr Pantelias, respectively, to Ms Chen.

63 The owners contend that the primary judge was correct to find that the requests contained in those communications were addressed to Ms Chen in China, were intended to be acted upon by her in China and were intended to have effect in respect of a ship in the territorial waters of China. Accordingly, the primary judge correctly applied Voth v Manildra Flour Mills Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 538 in holding that the events allegedly comprising the tort of unlawful interference with contractual relations occurred in China.

64 The owners also seek to sustain the judgment in its favour by advancing a number of contentions which were not upheld by the primary judge.

65 The owners argue that, if Daebo retained title to the bunkers after 3 January 2009, then title to the bunkers passed back to the owners upon withdrawal of the ship under the head charter on 15 January 2009. The proper approach under Australian law to the location of tortious conduct is to ascertain the place at which the defendant’s tortious act occurred. The focus is on the defendant’s act rather than its consequences. Relying on the decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Union Shipping New Zealand Ltd v Morgan (2002) 54 NSWLR 690 the owners submit that the law of the littoral state applies in respect of torts committed aboard a ship moored in territorial waters and in unloading goods to shore in a continuous operation. The owners contend that the law of the littoral state, in this case China, should be applied to determine whether their assumption of ownership and full possession of the bunkers on 15 January 2009 constituted an unlawful conversion.

66 The evidence of Mr Chen Yusheng established that, under Chinese law, the law applicable to conversion of goods in the territorial waters of China is the law of China. Under Chinese law, Daebo must establish title to the bunkers in order to maintain a claim for their conversion. Under the law of China, on withdrawal of the ship on 15 January 2009 title to the bunkers reverted to the ship owner. If title reverted to the owners, in accordance with the law of China, a claim in detinue or conversion cannot succeed under the law of Australia. This is so even if the goods are moved to an Australian jurisdiction and demand is made for their delivery up; Camell v Sewell (1858) 3 H&N 617; Winkworth v Christie Manson and Woods Ltd [1980] 1 Ch 497.

67 The owners submit that cl 31 of the charterparty ought to be construed so as to require the disponent owner to pay for bunkers on redelivery which occurs whenever a ship is withdrawn by any disponent owner higher up in a chain of charterparties. Withdrawal of the ship meant that the bunkers on the ship on 15 January 2009 were redelivered by Daebo to Bluefield; Bluefield to BMS; and BMS to the owners. If that is so, the owners were entitled to the bunkers on withdrawal of the ship. This construction means that Daebo would have to account to Nanyuan and would benefit in an accounting with Bluefield.

68 The owners also contend that by its agent’s communications with Nanyuan they did no more than lawfully assert a lien in respect of the sub-hire payments due from Nanyuan to Daebo by reason of clause 18 of the head charter and its equivalents in the sub-charterparties. On this basis their interference with Daebo’s contract with Nanyuan is said to be justified.

69 The owners argue that “sub-freight” in clause 18 includes sub-hire because they are a species of the same genus. The owners support this argument with reference to Care Corp Shipping Co v Latin American Shipping Corp (The Cebu (No 1)) [1983] QB 1005 (“Cebu (No 1)”) where Lloyd J held that “sub-freights” include hire charges payable under a time charter party. The Cebu (No 1) was applied on this point in the New South Wales Supreme Court decision of Mutual Export Corporation v Asia Australian Express Ltd, “The Lakatoi Express” (1990) 19 NSWLR 285.

70 Subsequently, in Care Shipping Corp v Itex Itagrani Export SA, “The Cebu” (No 2) [1993] QB 1 (“Cebu (No 2)”), Steyn J held , because of a change in modern usage, that “sub-freights” did not extend to hire charges payable under a time charter party. The owners submit that the approach of Lloyd J in The Cebu (No 1) is to be preferred.

CONSIDERATION

Daebo’s claim to the bunkers

71 Under a time charter in the NYPE and similar forms, ordinarily, property in the bunkers on board at the time of delivery of the vessel will pass, at that time, to the charterer: The Span Terza (No 2) [1984] 1 WLR 27 at 31G-32A; [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 119 at 122 per Lord Diplock with whom the rest of the House of Lords agreed; The Saetta [1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 268 at 273 per Clarke J. Here, the terms of the Daebo sub-charter were expressly adopted in the clean recap, with logical and minor alterations to give effect to specific provisions in that recap. Thus, delivery of Go Star to Nanyuan was to occur at Chang Jaing Kou on dropping the last outward sea pilot (cl (a) of his Honour’s summary of the clean recap’s terms: see [18] above); lines 34-37 of the 1981 NYPE form.

72 Delivery under a time charter occurs when the owner (or disponent owner) places the ship at the charterer’s disposal, as Roskill J explained in The Madeleine [1967] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 224 at 238, when he said:

It is, of course, axiomatic that in a time charter of this description delivery does not import any transfer of possession. An owner delivers a ship to a time charterer under this form of charter-party by placing her at the charterers’ disposal and by placing the services of her master, offices and crew at the charterers’ disposal, so that the charterers may thenceforth give orders (within the terms of the charter-party) as to the employment of the vessel to the master, officers and crew, which orders the owners contract that their servants shall obey.

73 Delivery in this sense, under the time charter, not only places the vessel at the disposal of the charterer, but it also marks the time of commencement of the charterer’s obligation to pay hire: The Niizuru [1996] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 66 at 68 per Mance J; Terence Coghlin, Andrew W Baker, Julian Kenny, John D Kimball: Time Charters (6th ed) (Informa; London 2008) at [7.29], [7.33]: see cl 4 (lines 96-101) of the 1981 NYPE form.

74 Here, the clean recap provided that “FIRST HIRE + BOD [Bunkers on delivery] value to be PAID” to the owners (i.e. Daebo’s) nominated bank within three banking days of the vessel’s delivery to Nanyuan. This qualified cl 31 of the 1981 NYPE form, that provided “Charterers to take over and pay together with first hire payment bunkers on vessel’s delivery”. And, as is usual in time charters, cl 2 of the 1981 NYPE form required the charterer to provide and pay for all the fuel. The recap had the effect of allowing Nanyuan, as charterer, three banking days after delivery of the vessel, before it had to pay both the first 15 days hire in advance and the value of the bunkers at the time of delivery.

75 The construction for which Daebo contends is somewhat elusive as a matter of the language of cl 31 of the Nanyuan sub-charter and cl (b) of the primary judge’s summary of the clean recap. Daebo’s preferred construction does not accommodate the commercial reality asserted by Daebo’s own invoice of 4 January 2009 under which delivery had taken place under the charterparty to Nanyuan, and confirmed by the fact that the ship was sailing under Nanyuan’s instructions.

76 It is not necessary that the charterer perform some act so as to “take over” the bunkers under cl 31. Rather, the expression “take over”, in relation to the bunkers as used in the time charter, signifies a change of ownership consequent upon and concurrent with delivery of the ship to the charterer under the charterparty. Daebo’s construction of the charterparty would lead to uncertainty as to the ownership of the bunkers at any particular time. That construction does not lead to a commercial or common sense result.

77 Under the Nanyuan sub-charter, Nanyuan, first, had to provide and pay for all the fuel from the time of delivery, and secondly, within three banking days of delivery of Go Star at Chang Jiang Kou, had to pay the first 15 days hire together with the value of the bunkers at that time. These provisions reflected a commercial purpose that the charterer should be responsible for providing and paying for the ship’s bunkers from the moment of her delivery until the moment of her redelivery. Those two times delimited the period in which the charterer could give orders for the employment of the ship for the charterer’s purposes under the charterparty. Hence, the obligation for the charterer to take over and pay for the bunkers at the time of delivery (and its corresponding right, subject to the limitations in the redelivery clause, to be paid for the value of the bunkers on redelivery).

78 Consistently with what Roskill J explained in the Madeleine [1967] 2 Lloyd’s Rep at 238, and with the definition of “delivery” in the Nanyuan sub-charter, delivery for the purpose of conferring the right to instruct the owner and master of a vessel as to its movements and operations occurs when the vessel is placed at the charterer’s disposal. At the point where the ship is made available to the charterer, the ship is delivered in the sense that from that moment it will be up to the charterer to exercise the rights to employ the ship conferred on it during the term of the charter. The charterer cannot assert that it has not taken over the ship and its bunkers once a ship is made available or placed at its disposal, by delivery, in accordance with the terms of the time charter to sail under the charterer’s instructions.

79 Counsel for Daebo argued that there was no evidence of instructions being given by Nanyuan to the master of the ship after 3 November 2009. However, there can be no doubt that once the contractually agreed moment for delivery occurred and the master acknowledged that Go Star had been delivered to Nanyuan, the ship was sailing under the instructions of Nanyuan, given via Ms Chen, on 1 January 2009. It is true that these instructions were given prior to delivery, but there is no suggestion that Nanyuan sought to countermand them before they were acted upon by the master of the ship.

80 As a matter of commercial common sense, the agreement in lines 27-28 and 34-36 and cll 2 and 31 of the 1981 NYPE form should be read so that the hire of the ship commences at the time of delivery, and the charterers take over and must pay for the bunkers contemporaneously. Thus, once the vessel is placed at the disposal of the charterers, and so “delivered” to them, they “take over”, and become obliged to pay for, the bunkers and further fuel for the charter, from that moment. There is no difference of commercial substance between “take over” in the present case and “accept” in The “Saint Anna” [1980] 1 Lloyd’s Rep at 182-183; The “Span Terza” (No 2) [1984] 1 WLR at 31G-32A; [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep at 122.

81 The three banking days’ postponement of the charterer’s obligation to pay the first hire and value of the bunkers on delivery provided in the clean recap, did not negate or qualify the operation of the recap’s provisions, including those incorporating the provisions of the 1981 NYPE form, concerning the vesting of title to the bunkers in the charterers on delivery. However, the consequence of the postponement of the charterer’s obligation to make that first payment, reflected a commercial allocation of risk for any non-payment that fell on the owners.

82 Accordingly, Nanyuan obtained title to the bunkers on board Go Star when delivery occurred on 3 January 2009. This conclusion makes it unnecessary to resolve the issue raised by the owners as to the passing of title under the law of China. Indeed, in any event, the clean recap provided that English law applied to its provisions, so that the contractual position as to ownership of the bunkers under the Nanyuan sub-charter depended on the English law principles applied above.

Interference with contractual relations

83 The crucial question here is one of fact. The evidence as to the role played by Ms Chen within Nanyuan, and as to the relationship between Ms Chen and Captain Hu, is distinctly exiguous. Importantly, there was no evidentiary basis for a conclusion that Ms Chen, and not Captain Hu, was the decision-maker within Nanyuan who was influenced by the warnings issued on behalf of the owners by Mr Pantelias in deciding to terminate the sub-charter with Daebo. In our respectful opinion, the primary judge’s finding on this issue is not sustainable.

84 Critically, his Honour found that the communications between Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu had little weight because Ms Chen was the person on Nanyuan’s side in charge in relation to the Nanyuan sub-charter However, that conclusion is not consistent with Ms Chen’s initial email to the master of 1 January 2009. That made clear that she was acting for Nanyuan and that it had a principal into whose time charter fleet she was welcoming the master. More importantly, the intervention of Captain Hu, came immediately after the owners’ initial email on 2 January 2009, sent by Mr Pantelias to Ms Chen. Nanyuan’s response to the email was that Ms Chen appears to have passed the matter to Captain Hu to represent Nanyuan’s (or its principal’s) interests in communications with the owners.

85 Given the seriousness of Mr Pantelias’ email of 2 January 2009, it is highly likely that Captain Hu was Ms Chen’s superior or a person to whom she reported. He was the person by whom Nanyuan or its principal wished to be represented in relation to a serious issue under its charterparty. Captain Hu’s email to Mr Pantelias of 3 January 2009 asked for the name of the person in charge on the owners’ side. Mr Pantelias had to explain to Captain Hu, in Singapore, not Ms Chen, the owners’ position and repeat to him its request that Nanyuan not pay hire to Daebo. Mr Pantelias followed this up with an email to Captain Hu reiterating the points he had made in his discussion. On 7 January 2009, Mr Pantelias emailed Captain Hu and Ms Chen at Nanyuan’s China address. Similarly, on 9 January 2009 Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu had another phone discussion and Mr Pantelias once again emailed Captain Hu at Nanyuan’s China address confirming that the head charterers had not paid hire and were seriously in arrears.

86 In those circumstances the evidence did not support the inference drawn by his Honour that Ms Chen, rather than Captain Hu, was in charge or played a relevant role in the contractual (as opposed to operational) relationship between Daebo and Nanyuan. Ms Chen had made it clear that she was acting for a principal. She asked for the master to copy emails to Captain Hu’s address (albeit she gave the Singapore email address without using his name) and Captain Hu dealt directly with Mr Pantelias by telephone. Ms Chen’s email of 1 January 2009 stated that she was the person in charge in the context of the preliminary statement welcoming the master “into our principal’s time charter fleet. This voyage will be controlled and operated by …” Nanyuan. That made clear that her role was operational as opposed to contractual.

87 The evidence of the conduct of Mr Pantelias and Captain Hu was entirely consistent with Captain Hu being the person in charge on Nanyuan’s side in respect of its contractual relations. Indeed, the fact that Mr Pantelias’ discussions about contractual matters were conducted solely with Captain Hu supports the conclusion that the latter position is more likely to be correct.

88 The tort of inducing a breach of contract consists of the following elements:

(1) there must be a contract between the plaintiff (or applicant) and a third party;

(2) the defendant (or respondent) must know that such a contract exists;

(3) the defendant must know that if the third party does, or fails to do, a particular act, that conduct of the third party would be a breach of the contract;

(4) the defendant must intend to induce or procure the third party to breach the contract by doing or failing to do that particular act;

(5) the breach must cause loss or damage to the plaintiff.

89 The gravamen of the tort is the defendant’s intention to induce or procure the breach in the knowledge that such a breach will interfere with the plaintiff’s contractual rights: Allstate Life Insurance Co v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (1995) 58 FCR 26 at 43A-C per Lindgren J with whom Lockhart and Tamberlin JJ agreed; Fightvision Pty Ltd v Onisforou (1999) 47 NSWLR 473 at 509-512 [159]-[171] per Sheller, Stein and Giles JJA; LED Technologies Pty Ltd v Roadvision Pty Ltd (2012) 199 FCR 204 at 212-216 [40]-[54] per Besanko J with whom Mansfield and Flick JJ agreed. As Lindgren J explained, the defendant must have “a fairly good idea” that the contract benefits another person in the relevant respect. He said that knowledge of the contract may be sufficient for the purpose of grounding the necessary intention to interfere with contractual rights, even though the defendant does not know the precise term that will be breached. Reckless indifference or wilful blindness can amount to knowledge for this purpose: Allstate 58 FCR at 43C-44F; Fightvision 47 NSWLR at 512 [171]; LED 199 FCR at 216 [54].

90 Here, Mr Pantelias on behalf of the owners, knew of the Nanyuan sub-charter and of its requirements that Nanyuan pay charter hire and other moneys to Daebo. He also knew that if Nanyuan did not pay money to Daebo as and when due Nanyuan would breach the charterparty and Daebo would suffer financial loss. Mr Pantelias on four occasions urged Nanyuan by email and twice by conversations with Captain Hu, not to pay charter hire and any other money due to Daebo under the Nanyuan sub-charter.

91 The owners’ conduct in urging Nanyuan not to pay hire in performance of its sub-charterparty with Daebo was not justifiable as the lawful assertion of a claim to a lien. The claim asserted by the owners through Mr Pantelias exceeded any lien that might legitimately have been asserted by them. This is because the owners had no claim to a lien over money due to Daebo by Nanyuan for the bunkers. The bunkers were initially owned by the charterers and then sequentially transferred to the next charterer under each charterparty in the string of charterparties. Thus, money payable for the bunkers was not in the nature of freight or hire but a debt due on a sale of property.

92 Moreover, the owners did not assert any lien directly by requiring Nanyuan to pay hire to them. Rather, the owners informed Nanyuan that they, at some unspecified time in the future, might require payment of money due by Nanyuan to Daebo and, for that reason, the owners urged Nanyuan not to pay “any sums under your charter as you may be called upon to pay twice over such sums”.

93 That urging sought to persuade Nanyuan not to pay what was then due to Daebo under the Nanyuan sub-charter. It was coupled with an assertion that the owners could make Nanyuan pay them a second time any sums Nanyuan might pay Daebo under the Nanyuan sub-charter. Both of those bases on which the owners sought Nanyuan to act had no legal justification. Both bases were calculated to, and did, induce Nanyuan to breach its obligations to pay hire and for the value of the bunkers on delivery of Go Star due under the Nanyuan sub-charter.

94 Although the parties referred to the owners as having asserted a lien over money payable by Nanyuan, the evidence falls short of supporting that characterisation. All the owners did was to repeat requests that Nanyuan not pay money due to under the Nanyuan sub-charter because the owners might at some time in the future decide to assert that that money be paid to them. That statement was not a notice of exercise of any lien that the owners had. At no time did the owners make a demand on Nanyuan to Daebo. Moreover, it was conceptually flawed. The lien created by cl 18 is effective only as security for a shipowner over any sum, being “subfreight”, to which it might attach that is currently due but unpaid by the person against whom the lien is asserted.

95 The jurisprudential nature of an owner’s lien of the kind contained in cl 18 of the 1981 NYPE form is a matter of some controversy not merely between academics but also judges. However, two features appear to be reasonably clear. First, a lien over sub-freights gives a shipowner the right to step in and claim payment of any unpaid and presently due sub-freights to himself where his time charterer has defaulted: The “Spiros C” [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 319 at 323 [11] per Rix LJ with whom Brooke and Henry LJJ agreed. Secondly, the lien covers freights and sub-freights that, in the event, come to be payable and which are in fact payable under any charterparty or bill of lading, but does not catch any such freights or sub-freights that have been paid before the shipowner gives the payer notice of his lien over that sum: Federal Commerce & Navigation Co Ltd v Molena Alpha Inc (the “Nanfri”) [1979] AC 757 at 777F-G per Lord Wilberforce with whom Viscount Dilhorne and Lord Scarman agreed, 782A-B, E-F per Lord Fraser of Tullybelton and 784F-785B per Lord Russell of Killowen; The “Spiros C” [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep at 323 [11].

96 Here, the owners may in one sense have given Nanyuan notice of their lien because they asserted its existence. But the owners did not claim to be presently entitled to, and certainly did not request or require, payment of any sub-freight (however wide that term may be) then due by Nanyuan to Daebo under their charter. Rather, the owners urged Nanyuan not to make any payment to anyone of any moneys it owed Daebo. That did not amount to the owners giving notice to Nanyuan of a claim that they had a lien over any sum due by Daebo to Nanyuan. However, it had the effect of interfering with Nanyuan’s performance of its obligation to pay its then presently due debt to Daebo for the first hire and the value of bunkers on delivery.

97 As we have mentioned, the nature of a shipowner’s lien under a time charter containing a clause like cl 18 of 1981 NYPE form is unsettled. It is not necessary to resolve that issue given that the owners here did not assert what lien or right they had over moneys due by Nanyuan.

98 In Federal Commerce [1979] AC at 784F-G Lord Russell had suggested that the shipowner’s lien on sub-freights operated as an equitable charge upon what was due from the shipper (under a bill of lading) to the charterer and, in order to be effective, required an ability to intercept the sub-freight (by notice of claim) before it was paid to the charterer by the shipper (or consignee or holder of the bill of lading). In England the lien had been held to be a registrable charge either on book debts or at least of a floating nature: Agnew v Commissioner for Inland Revenue [2001] 2 AC 710 at 727 [39] (but that position has since been reversed by statute). There Lord Millett, giving the advice of a strong Judicial Committee (Lords Bingham of Cornhill, Nicholls of Birkenhead, Hoffmann and Hobhouse of Woodborough), observed that the lien was not the creation of common law or equity but had originated in maritime law based on the shipowner’s lien on cargo. He said that it is a contractual non-possessory right of a kind which is sui generis. The Privy Council said that Lord Russell’s observation that the lien was an equitable charge was a passing remark not necessary for the decision “and if the lien is a charge it is a charge of a kind unknown to equity” ([2001] 2 AC at 728 [41]). Their Lordships continued:

An equitable charge confers a proprietary interest by way of security. It is of the essence of a proprietary right that it is capable of binding third parties into whose hands the property may come. But the lien on subfreights does not bind third parties. It is merely a personal right to intercept freight before it is paid analogous to a right of stoppage in transitu. It is defeasible on payment irrespective of the identity of the recipient. In this respect it is similar to a floating charge while it floats, but it differs in that it is incapable of crystallisation. The ship owner is unable to enforce the lien against the recipient of the subfreights but, as Oditah observes, this is not because payment is the event which defeats it (as Nourse J stated in In re Welsh Irish Ferries Ltd [1986] Ch 471; it is because the right to enforce the lien against third parties depends on an underlying property right, and this the lien does not give. Apart from the obiter dictum of Lord Russell in the Federal Commerce case, the cases in which the lien has been characterised as an equitable charge are all decisions at first instance and none of them contains any analysis of the requirements of a proprietary interest. Quite apart from the conceptual difficulties in characterising the lien as a charge, the adverse commercial consequences of doing so are sufficiently serious to cast grave doubt on its correctness.

99 One commentator, Simon Baughen, sought to explain Lord Millett’s analysis as a mere restatement of what he had put unsuccessfully as counsel to Nourse J in the course of argument in Re Welsh Irish Ferries Ltd [1986] Ch 471 (which held that the lien was a registrable charge): The Evolving Law and Practice of Voyage Charterparties: Edited by Prof D Rhidian Thomas (informa, London 2009) at [11.21]-[11.22]. However, that critique is specious. First, Lord Millett sat with Lords Bingham and Hobhouse, both of whom had extensive Admiralty experience and would have been unlikely to have joined in the opinion delivered by Lord Millett if they disagreed. Secondly, their Lordships were correct in describing the origins of the lien as stemming from maritime law and not from the common law or equity.

100 The early cases dealt with the consequences in various factual situations of a shipowner demanding payment of freight due by a shipper under a bill of lading that had been signed by the master under a time charterer’s instructions in differing circumstances as explained by Greer J in Molthes Rederi Aktieselskabet v Ellerman’s Wilson Line Ltd [1927] 1 KB 710. Ordinarily, when a time charterer instructs the master to issue bills of lading, the bills will be contracts between the shipowner and the shipper (of the cargo) for the carriage of goods on the ship. The charterer, as between himself and the shipowner, will be entitled to receive payment from the shipper as an incident of his right to employ the ship under the charter. But, as Greer J pointed out, strictly speaking, the shipowner’s lien on sub-freight is not a lien at all, since under an owner’s bill of lading the money is due to the shipowner by the shipper ([1927] 1 KB at 716-717). Rather, he held that the lien clause in the charterparty was needed to give the owner a lien where the sub-freight was due to the charterer and not to the owner, such as when goods were carried on a sub-charter without any bill of lading: [1927] 1 KB at 717 and see too The “Spiros C” [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep at 323 [11]; Legal Issues Relating to Time Charterparties: Edited by Prof D Rhidian Thomas (informa, London 2008) at [16.20]-[16.39], a chapter contributed by Prof Richard W Williams.

101 The dispute between the two decisions of Lloyd J and Steyn J in the Cebu cases [1983] QB 1005 and [1993] QB 1 concerned the characterisation of the expression of “subfreights” in the lien clauses and whether by the late twentieth century it had ceased to comprehend “subhire” payable under a charterparty. Lloyd J held that for over a century the expression “subfreights” as used in cl 18 of the NYPE form had included sub-hire and “any remuneration earned by the charterers from their employment of the vessel, whether by way of voyage freight or time chartered hire”. He found that this included all sub-freights due under a chain of time charter parties ([1983] QB at 1011C-D, 1012F-G, 1013A-C).

102 Steyn J held that a change in usage of the word “subfreights” had occurred “in modern times” and before publication of the 1946 amendment of the NYPE form. He relied on a statement by Lord Denning MR in the Court of Appeal in Federal Commerce & Navigation Co Ltd v Molena Alpha Inc (The “Nanfri”) [1978] QB 927 at 973 that suggested a change in modern times so that payments due under a time charter “are usually now described as ‘hire’ and those under a voyage charter as ‘freight’”. (Emphasis added.) Steyn J concluded that the ordinary meaning of “freight” at all material times included only bill of lading freight payable under a voyage charterparty, including when used in the NYPE form of time charter ([1993] QB at 12C-D, 13A, 14-14A). Accordingly, he confined the meaning of “freight” and “all subfreights” as used in cl 18 of the 1946 NYPE form (which is relevantly the same as the 1981 version) to bill of lading freight and freight under voyage charterparties and did not include sub-time charter hire ([1993] QB at 14G-15C). Scrutton on Charterparties (22nd ed) (Sweet & Maxwell; Thomson Reuters, London 2011) at [16-014] suggests that Steyn J’s seems the better view as does Time Charters (6th ed) op. cit at [30.20] while DC Jackson: Enforcement of Maritime Claims (3rd ed) (LLP, London 2000) at [22.28]-[22.29] expresses no preference.

103 What is, however, curious about Steyn J’s reasoning is its omission to consider the meaning in the United States, where, after all, the NYPE forms were written, of the expression “subfreights”. Obviously, there are substantive differences between English and United States maritime law, not least over the ambit of what a lien is. Nonetheless, one recent leading United States text, Thomas J Schoenbaum: Admiralty and Maritime Law (3rd ed) (West Group, St Paul, Minnesota, 2001) Vol 2 at §11-17, p 236 dealt with the issue of the shipowner’s lien against sub-freights in charterparties in a footnote stating:

Subfreights are the hire under a subcharter as well as bill of lading freight payable by shippers and consignees.

104 In addition, because cl 18 expressly recognises that, as between owner and charterer, the owner can exercise a lien over the cargo (as would ordinarily be the case with any bill of lading signed by the master), the reference to “sub-freight” must apply to money due to, or able to be demanded by, the charterer from a sub-charterer. Last, Lord Denning MR’s qualification of “usually” to the descriptions of “hire” and “freight” does not suggest that a complete change in usage had occurred in recent times even in English law. However, these matters were not explored in argument and it is not necessary to decide them.

105 It is not necessary for this Court to resolve the conflict between Cebu No 1 and Cebu No 2. That is because, even on the broader view of the expression “sub-freight”, it does not comprehend the debt owed by Nanyuan to Daebo in respect of the sale of the bunkers.

106 Accordingly, the owners’ assertion that they had a lien that they might exercise in the future (but had not asserted) over the money payable by Nanyuan to Daebo under the charterparty as a reason why Nanyuan should not pay its debts to Daebo as and when they were due was not justified by cl 18 of the head charter. Their interference with the relationship between Nanyuan and Daebo was tortious if Australian law was applicable to the owners’ conduct in dealings with Captain Hu in Singapore, as we think it was: see [52] above. The owners, through Mr Pantelias’ conduct, intended to procure or induce Nanyuan to withhold payment of money to Daebo in breach of Nanyuan sub-charter. The owners succeeded in inducing such a breach.

107 It follows that we consider that the appeal must be allowed in relation to Daebo’s claim for damages for interference with its contract with Nanyuan.

108 It falls to this Court to assess the damages payable to Daebo. We would assess those damages on the footing that Daebo is entitled to recover for the value of the bunkers at the rates prescribed in the sub-charterparty. That is a different rate from that sought by Daebo.

109 Daebo seeks damages at the rate of USD285 per tonne of fuel oil and USD500 per tonne of diesel oil, being market rates. Under the provisions of the sub-charterparty, Daebo was entitled to be paid USD230 per tonne of fuel oil and USD450 per tonne of diesel oil. Daebo hypothesises that the contract with Nanyuan remained on foot until consensually terminated and it is on this basis that its damages are to be assessed. On this hypothesis, the latter figures represent the value per metric ton of what Daebo would have received for the bunkers had the Nanyuan sub-charter been performed in accordance with its terms.

110 In summary, Daebo is entitled to damages calculated as follows:

Value of bunkers on delivery

882.62 MT fuel oil @ USD230 203,002.60

79.52 MT diesel oil @ USD450 35,784.00

Loss of 12 days hire @ USD4,250 51,000.00

USD289,786.60

In addition, Daebo is entitled to interest on its damages at a rate appropriate to US dollars.

Daebo’s change of corporate status

111 The writ was filed by the presently named appellant, as plaintiff below, on 3 February 2009. Until 25 July 2012, after judgment had been reserved in the appeal, Daebo’s solicitors were unaware that on 5 January 2010 a corporate restructuring occurred in South Korea. As a consequence Daebo, merged or was “absorbed” into Daebo International Shipping Co Ltd (Daebo International). The evidence of an expert in South Korean law, Tae II Kwon, was in effect that, under the principle of universal succession, when one company is merged or absorbed into another, the rights and liabilities of the absorbed company cease to exist and are automatically transferred to the absorbing company. That process of merger or absorption resembles what occurs when rights and liabilities of one company are transferred to another under a scheme of arrangement pursuant to an order made by force of s 411 of the Corporations Act 2011 (Cth).

112 Initially, the owners refused to consent to Daebo International’s request to regularise the position by amending the name of the plaintiff in the proceedings below and the appellant in the appeal. That required Daebo International to obtain expert evidence and file an interlocutory application in the Full Court on 21 September 2012. On 25 October 2012, the owners’ solicitors informed the Court that after taking advice on the position under South Korean Law they did not oppose the application. However, the owners sought costs of the interlocutory application.

113 The appeal was instituted and conducted in Daebo’s name although at all times it had ceased to exist and been succeeded by Daebo International. There is no doubt that throughout both the appeal, and the proceedings below since 5 January 2010, the rights and liabilities that Daebo had were assumed by Daebo International and that the latter intended to engage in the litigation on that basis, albeit without seeking a formal amendment of Daebo’s name to its own.