FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCAFC 178

PROPERTY – usufructuary right – nature of – application to native title rights and interests

WORDS AND PHRASES - usufructuary

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth)

Crown Lands Act 1992 (NT) s 108, s 95, s 3

Crown Lands Ordinance 1931-1972 (Cth)

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) s 47B, s 223, s 225

Amodu Tijani v Secretary, Southern Nigeria [1921] 2 AC 399 cited

Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1 cited

Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 cited

Hayes v Northern Territory (1999) 97 FCR 32 cited

Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 cited

Mason v Tritton (1993) 6 BPR 13,639 cited

Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572 cited

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 cited

Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442 cited

Risk v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCA 404 cited

The Administration of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea v Daera Guba (1973) 130 CLR 353 cited

Transurban City Link v Allan (1999) 95 FCR 553 cited

Wik Peoples v State of Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 cited

ALAN GRIFFITHS AND WILLIAM GULWIN (ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES) v NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA

NTD 16 OF 2006

FRENCH, BRANSON & SUNDBERG JJ

22 NOVEMBER 2007

MELBOURNE (HEARD IN DARWIN)

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY | NTD 16 OF 2006 |

| ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGE OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | ALAN GRIFFITHS AND WILLIAM GULWIN ( ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES) Appellant

|

| AND: | NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Respondent

|

| FRENCH, BRANSON & SUNDBERG JJ | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 22 NOVEMBER 2007 |

| WHERE MADE: | MELBOURNE (HEARD IN DARWIN) |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

A. The appeal beallowed.

B. The native title determination made by Weinberg J on 28 April 2006 bevaried by omitting [5] to [9] and the heading of those paragraphs and substituting the following:

“5. The native title holders are:

(a) the persons referred to in paragraph 4 who are members of the relevant estate group; and

(b) other Aboriginal persons who, in accordance with traditional laws and customs, have rights in respect of the land and waters of the relevant estate group, being:

(i) members of estate groups from neighbouring estates;

(ii) spouses of estate group members; and

(iii) members of other estate groups with ritual authority.

The native title rights and interests (s 225(b) and 225(e))

6. The native title rights and interests in relation to that part of the determination area described in paragraph (a) of Schedule A are rights in accordance with traditional laws and customs to the possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that part of the determination area to the exclusion of all others.

7. The native title rights and interests in relation to that part of the determination area described in paragraph (b) of Schedule A are the following non-exclusive rights in accordance with traditional laws and customs:

(a) the right to travel over, move about and to have access to the determination area;

(b) the right to hunt, fish and forage on the determination area;

(c) the right to gather and to use the natural resources of the determination area such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin;

(d) the right to have access to and use the natural water of the determination area;

(e) the right to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters and other structures;

(f) the right to:

(i) engage in cultural activities;

(ii) conduct ceremonies;

(iii) hold meetings;

(iv) teach the physical and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance on or in the land and waters; and

(v) participate in cultural practices relating to birth and death, including burial rights.

(g) the right to have access to, maintain and protect sites of significance on the determination area;

(h) the right to share or exchange subsistence and other traditional resources obtained on or from the land or waters (but not for any commercial purposes).

8. The paragraphs designated (d) and (e) in Schedule A of the Determination be redesignated (a) and (b) respectively.

9. The native title rights and interests in relation to that part of the determination area described in paragraph (b) of Schedule A, do not confer rights to the possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that part of the determination area to the exclusion of all others.

C. Paragraphs 10 to 14 of the determination are renumbered as paragraphs 9 to 13.

D. The cross-appeal bedismissed.

E. The parties bear their own costs of the appeal and cross-appeal.

F. Liberty to the parties to apply within 21 days for any further orders that may be necessary by reason of the preceding orders or otherwise to give effect to the judgment of the Court.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

INDEX

Introduction [1] – [8]

Native title claim group [9]

The land and waters the subject of the claim [10]

The native title rights and interests claimed [11]

Reasons for judgment of the trial judge [12] – [55]

Grounds of appeal [56]

Proposed variations to the determination [57]

The cross-appeal by the Northern Territory [58]

The Northern Territory’s first notice of contention [59]

The Northern Territory’s further notice of contention [60]

Statutory framework – native title rights and interests [61] – [62]

Whether the finding of non-exclusivity

involved an error of principle [63] – [71]

Evidence at trial relevant to exclusivity of native

title rights and interests [72] – [79]

1. Alan Griffiths [80] – [84]

2. Jerry Jones [85] – [87]

3. Josie Jones [88]

4. Mr Lewis [89]

5. Doris Paddy [90]

6. Roy Harrington [91]

7. William Gulwin [92]

8. Georgie Jones [93]

9. Deborah Jones [94]

10. Violet Paliti [95]

11. Mrs Smiler [96]

12. Christopher Griffiths [97]

13. Lorraine Jones [98]

14. Sammy Darby [99]

The primary judge’s treatment of evidence relevant to exclusivity [100] – [106]

The Northern Territory’s arguments on exclusivity [107]

The Northern Territory’s argument on exclusivity under its

Further Notice of Contention [108] – [112]

The appellants’ response to the further notice of contention [113] – [123]

Whether the further notice of contention should be entertained [124]

Whether the primary judge erred in not finding exclusivity [125] – [128]

The cross-appeal – the shift from patrilineal to

cognatic descent principles [129] – [146]

The cross-appeal and notice of contention – s 47B of the NT Act [147] – [149]

Statutory framework – s 47B of the NT Act [150]

The proclamation of Timber Creek [151] – [152]

The primary judge’s reasoning [153]

The decision of the Full Court in Alyawarr [154] – [170]

The cross-appeal – the previous exclusive possession act

– Crown Lease Term 624 [171] – [172]

Conclusion [173]

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY | NTD 16 OF 2006 |

| ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGE OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | ALAN GRIFFITHS AND WILLIAM GULWIN ( ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES) Appellant

|

| AND: | NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Respondent

|

| JUDGES: | FRENCH, BRANSON & SUNDBERG JJ |

| DATE: | 22 NOVEMBER 2007 |

| PLACE: | MELBOURNE (HEARD IN DARWIN) |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT

Introduction

1 On 10 December 1999 the first of three native title determination applications over land in the township of Timber Creek was filed in the Federal Court. Timber Creek is located on Victoria Highway, about half way between Katherine and Kununurra in the Northern Territory. It lies along the south bank of the Victoria River. The creek from which it takes its name, is a tributary of the river, and flows within the town. The first application was filed by Mr Alan Griffiths on behalf of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples. It sought a determination of native title rights and interests over a parcel of land in the township known as Lot 47. It was a protective response to a notice issued by the Northern Territory Government of the proposed compulsory acquisition of that land. A second application was filed by Alan Griffiths and William Gulwin on 11 May 2000, responding to notices for the compulsory acquisition of Lots 97-100, 109 and 114 Timber Creek which were dated 2 February 2000. The third application by the same applicants was filed on 18 July 2000. The area covered by that application included a number of other lots in the township, the waterway of Timber Creek including its beds and banks and land covered by a Special Purpose Lease 00494 owned by the Conservation Land Corporation. The land and waters claimed extended to the Victoria River and its beds and banks within the town boundaries. The Victoria River aspect of the claim was later dropped.

2 All three applications proceeded to trial and although they were not consolidated they were heard together pursuant to an order of District Registrar Edwards made on 9 September 2003. Evidence in each application was treated as evidence in the others. The respondents at trial were the Northern Territory and the Amateur Fishermen’s Association of the Northern Territory (AFANT). Although the Commonwealth was initially a respondent it withdrew once it became clear that the applicants did not propose to pursue their claim to the Victoria River or its beds and banks.

3 The application was heard by Weinberg J in March and April 2005. Additional submissions were filed between September and December 2005 and judgment delivered on 17 July 2006. His Honour found that the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples had established that they had native title rights and interests in the claim area but that those native title rights and interests did not include exclusive rights to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land. The parties were given an opportunity to consider the reasons and to formulate a draft determination to give effect to them. His Honour made a determination on 28 August 2006 which gave effect to his findings. It is set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

4 On 18 September 2006 Messrs Griffiths and Gulwin filed a notice of appeal asserting that his Honour erred in not finding that the rights and interests possessed under the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders conferred possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the determination area on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

5 The Northern Territory filed a notice of cross-appeal on 11 October 2006. It contended that his Honour should have found that the laws and customs under which the rights and interests in the claim area were asserted are not traditional laws and customs. This was based on the proposition that the native title rights and interests as claimed by the appellants devolved through a process of cognatic descent (ie through both father and mother) representing a fundamental shift from the patrilineal descent rule which had existed at the time of sovereignty.

6 The Northern Territory also contended that his Honour erred in law in finding that s 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NT Act) applied to land within the proclaimed boundaries of the town of Timber Creek and that prior extinguishing acts affecting that land could thereby be disregarded. A notice of contention filed in the appeal sought to support his Honour’s finding of non-exclusive native title rights and interests on the basis that, because s 47B did not apply in the claim area, the prior grant of pastoral leases over the land and waters of the claim had resulted in the extinguishment of exclusive native title rights and interests. In the course of the appeal hearing a further notice of contention was filed in effect asserting that certain estate groups which were part of the relevant traditional society were not included in the native title claim group which therefore was not in a position to assert that its native title rights and interests were exclusive.

7 For the reasons that follow we are of the view that the appeal should be allowed and the native title determination application amended to reflect a finding that the appellants have possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the part of the determination area described in [(a)] of Schedule A to the exclusion of all others. We are also of the opinion that the cross-appeal should be dismissed.

8 Having regard to the provisions of s 85A of the NT Act, the parties should bear their own costs of the appeal and cross-appeal.

Native title claim group

9 The native title claim group as ultimately identified in a further amended application filed on 18 March 2005 and treated by his Honour as a template for all three applications, comprised the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples descended from six apical Ngaliwurru persons identified as:

. Punitjkula (whose children include Takawak and Jarapil, and whose grandchildren include Violet Paliti);

. Mangarmawuk, or Mungaramawuk or Mangaramawuk, (whose brother was Lamparangana, and who was Alan Griffiths’ and Pat Jatjat’s maternal grandfather);

. Tiyawatulwan (whose children include Little Wally Wanampiwiri, and whose grandchildren include Darby Tiyawatulwan);

. Tiyawakatak (whose children include Mutpurula, whose grandchildren include Jo Lewis Niyapat and whose great grandchildren include Josie Jones Tatpung, and whose great grandchildren include Stephen Jones Yawunula and his sister Lorraine Jones Purrungurungali);

. Pulawatitj (whose children include Walamawuk and Tinker Kananji/Lalamak and whose grandchildren include Larry Johns Mungkawali); and

. Puijayinkari whose grandchildren include Dinah Maylinti and whose great grandchildren include Darby Tiyawatulwan).

The land and waters the subject of the claim

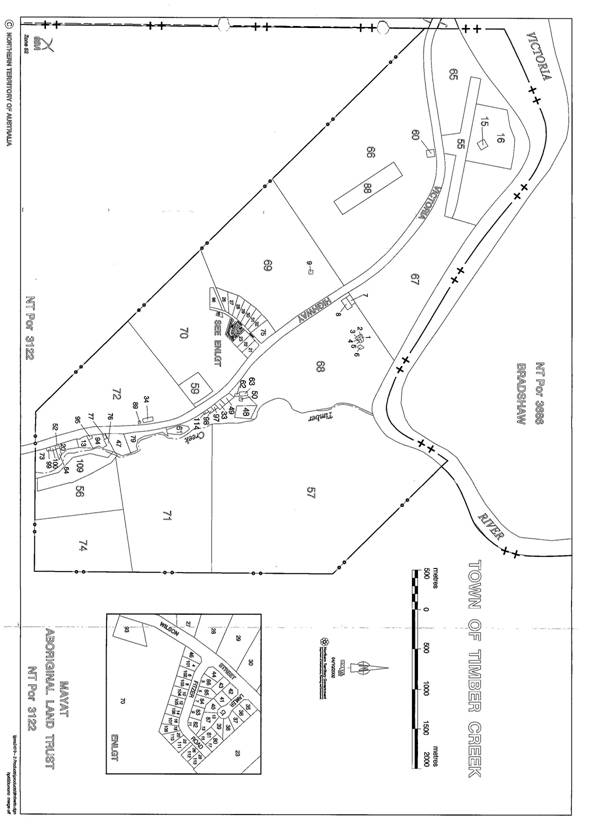

10 The claim area is land and waters located in the town of Timber Creek, within the Timber Creek town boundary in the Northern Territory as set out in the Northern Territory Government Gazette No 24 of 20 June 1975. The claim area included:

. vacant Crown land and waters, Lot numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 22, 33, 35, 37, 49, 56, 57, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 80, 87, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112 and 113;

. the creek named Timber Creek (including its bed and banks) as delineated on a map attached to the Further Amended Application; and

. Special Purpose Lease 00494, granted to the Conservation Land Corporation for the purpose of carrying out its functions in accordance with the Conservation Commission Act 1980 (NT) (subsequently renamed the Parks and Wildlife Commission Act 1980 (NT)) consisting of Lot 16 of the Town of Timber Creek.

Any area in relation to which a previous exclusive possession act under s 23B of the NT Act had been done was excluded from the claim.

The native title rights and interests claimed

11 The appellants asserted in their further amended application that the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples are entitled, under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by them, to exercise native title rights and interests in relation to the claim area including:

(a) to possess, occupy, use and enjoy the area claimed to the exclusion of all others;

(b) to speak for and to make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the application area;

(c) to reside upon and otherwise to have access to and within the application area;

(d) to control the access of others to the application area;

(e) to use and enjoy the resources of the application area;

(f) to control the use and enjoyment of others of the resources of the application area;

(g) to share, exchange and/or trade resources derived on and from the application area;

(h) to maintain and protect places of importance under traditional laws, customs and practices in the application area;

(i) to maintain, protect, prevent the misuse of and transmit to others their cultural knowledge, customs and practices associated with the application area;

(j) to determine and regulate membership of, and recruitment to, a landholding group.

It was asserted in the application that the claim area is part of a larger area of land and waters owned and occupied by the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples since before the acquisition of sovereignty.

Reasons for judgment of the trial judge

12 His Honour’s reasons for judgment, with schedules, occupied 210 pages. It included a detailed review of the evidence of indigenous witnesses and anthropological evidence as well as the voluminous documentary materials before the Court. The summary that follows focuses on those aspects of his Honour’s reasons which are relevant to the grounds of appeal, the cross-appeal and the notices of contention.

13 His Honour outlined the history of the claim area, evidence of which was set out in over 100 History Documents tendered in a large folder. He did not refer to them in detail as the historical record was not of itself a significant point of dispute between the parties. Broadly speaking the history was uncontentious.

14 European knowledge of the Victoria River district was gained gradually over a period of time from the earliest explorations until settlement. First European contact with the general area dated back to the mapping activities of Portuguese seafarers in the early 1500s. Successful exploration of the lower Victoria River was first undertaken in 1839 and observations made of a “native village” about one mile south west of the Victoria River. Evidence of a “large local population” was recorded. In 1855 Augustus Gregory led an expedition to the area. A major result of Gregory’s exploration was to make known the extent of prime grazing land in the region. Other explorations were carried out in the 1860s. In 1879 Alexander Forrest travelled overland from the Kimberley region. At about that time the first pastoral leases in the area were granted. Stocking of those holdings did not commence until several years later. The first permanent European settlement occurred with the establishment of cattle stations in the 1880s.

15 Following the arrival of permanent European settlers, Timber Creek became a significant port. It continued as such until the 1930s when the construction of roads made the port unnecessary. A local store was opened at a place known as Gregory’s Depot, upstream from the Victoria River Depot in 1890.

16 The growth of the pastoral industry led to exclusion of indigenous inhabitants from their traditional lands and conflict between them and pastoral owners. Ultimately the conflict decreased, peaceful contact became more regular and by 1905 most stations had established camps for Aboriginal workers at homesteads and outstations. By the 1930s the great majority of indigenous persons living in the Victoria River district lived in station camps and worked alongside Europeans. Some refused to live in the camps and continued to reside in the “rough back country” of the stations. Others moved between two modes of living.

17 During World War II many European station employees and drovers enlisted in the armed forces. Indigenous people played a greater role in the cattle station economy and some were put in charge of stock camps for the first time. After the war however, station life reverted more or less to what it had been in earlier times. Dissatisfaction with the terms and conditions of employment of Aboriginal people came to a head at Wave Hill in 1966. Aboriginal people walked off the job. They demanded full wages and improved conditions. Aborigines from other stations joined in the strike in subsequent years. Eventually Aboriginal people gained independence from the stations and began to receive full wages. On the other hand, pastoral property owners re-organised their economies. They spent more on fencing and other infrastructure and relied on technological advances, rather than large numbers of low paid stockmen. Far fewer Aborigines came to be employed than had previously been the case.

18 In 1976 the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (Land RightsAct) was enacted. It led to traditional owners obtaining grants of land in the northern Victoria River region. Fitzroy Station, Innesvale Station, the Stokes Range north of Jasper Gorge, Jasper Gorge itself, Mistake Creek, part of Wave Hill and the Hooker Creek Aboriginal Reserve all came under Aboriginal control.

19 His Honour referred to writings by an archaeologist, Darrell Lewis, experienced in the area, which indicated that Aboriginal people had been associated with Timber Creek from the time of the first European settlers and during the entire period of European settlement. Mr Lewis saw no reason to believe that the Aborigines encountered by the early explorers and settlers were not the ancestors of the Aboriginal people living in the area today. He referred to a long standing connection between the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples and Timber Creek recorded in 1934 by Professor WEH Stanner. He said that the association of those people with Timber Creek had been maintained in spite of early violent contact with Europeans. According to his records, despite over 100 years of European settlement traditional languages are still spoken, ceremonies performed and traditional foods and medicines harvested.

20 The appellants based their case in large measure upon findings made by various Aboriginal Land Commissioners who exercised powers of inquiry, report and recommendation under the Land Rights Act between 1985 and 1992. The findings concerned land immediately surrounding Timber Creek but not the town itself. The Land Rights Act does not extend to land within proclaimed towns. The findings were relied upon not merely because of the proximity of the areas concerned to the claim area, but also because they related basically to the same indigenous groups as the appellants.

21 The appellants acknowledged before his Honour that any findings made by Aboriginal Land Commissioners had to be qualified having regard to the fact that they were made under a statutory regime significantly different from that of the NT Act. Under the Land Rights Act claimants must demonstrate “traditional Aboriginal ownership” as defined in s 3(1). The term “traditional Aboriginal owners” in relation to land, for the purposes of that Act, means “a local descent group” of Aboriginals. Such a group must have common spiritual affiliations to a site on the land that places it under a primary spiritual responsibility for that site and for the land. The definition of “Aboriginal tradition” in s 3(1) is:

the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals or of a community or group of Aboriginals, and includes those traditions, observances, customs and beliefs as applied in relation to particular persons, sites, areas of land, things or relationships.

Importantly, as his Honour noted, claimants under the Land Rights Act are not required to establish continuity or historical links with the land.

22 His Honour cited four determinations under the Land Rights Actwhich were of particular significance to the appellants. These were contained in:

. The Timber Creek Land Claim Report No 21 (19 April 1985) – delivered by Commissioner Maurice).

. The Kidman Springs/Jasper Gorge Land Claim Report No 30 (31 March 1989) – delivered by Olney J.

. The Stokes Range Land Claim Report No 36 (28 June 1990) – delivered by Olney J.

. The Ngaliwurru/Nungali (Fitzroy Pastoral Lease) Land Claim No 137 and Victoria River (Bed and Banks) Land Claim No 140 Report No 47 (22 December 1993) – delivered by Gray J.

His Honour said (at [75]):

Those findings were all generally favourable to the indigenous groups that instituted the land claims. Section 86 of the NT Act renders them admissible in these proceedings as “the transcript of evidence in any other proceedings before … any other person or body…”

He cited Risk v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCA 404 per Mansfield J (at [431]-[432]).

23 Section 86 of the NT Act empowers the Court to receive into evidence the transcript of evidence in any other proceedings before, inter alia, any person or body and draw any conclusions of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper (s 86(a)(v)). The Court is also empowered by s 86(c) to adopt any recommendation, finding, decision or judgment of a body of a kind mentioned in subpara (v). There is a distinction between the receipt into evidence of the transcript of proceedings before a person such as a Land Commissioner and the adoption of findings made by that person. The first process involves the receipt of evidence upon which the Court may base its own findings. In the second process for which s 86(c) provides, the Court may accept a finding of another person or body resulting from a consideration of evidence by that person or body. That does not require that the Court examine for itself the evidence upon which the adopted finding was made. On the other hand it would allow the Court to give some consideration to the evidence underpinning the findings to satisfy itself that the finding was reasonably based on the evidence.

24 His Honour did not make clear the way in which s 86 of the NT Act was applied to his consideration of the Commissioners’ reports. He, in effect, outlined the content of the reports and the conclusions reached in them and appears to have treated those conclusions as evidence of the facts found without expressly adopting them as findings of his own. To the extent that he relied upon them we treat his reliance as an adoption of the findings.

25 The Timber Creek Land Claim Report dealt with a claim originally confined to the Timber Creek Commonage Reserve but ultimately amended to include the southern bank of the Victoria River between the eastern and western boundaries of the Reserve and adjoining the Reserve which did not form part of the town of Timber Creek. The claimants comprised six subgroups each associated with a separate tract of land. According to Commissioner Maurice, who made the report, it appeared from the genealogies and the evidence associating past generations with one tract or another, that the predominant, if not exclusive, principle for recruitment to the sub-groups was patrilineal descent. The exception was sub-group A whose patriline had died out in recent times. An anthropologist, Dr Ian Keen, had described the claimants in evidence before the Commissioner as a “cognatic kin group”. The Commissioner accepted that description but considered it unnecessary to rely upon it in order to find that the claimants now formed a local descent group within the meaning of the Land Rights Act. The learned trial judge quoted a passage from the Commissioner’s report thus (at [79]):

It is enough for me to say that up until the generations constituted by the children and grandchildren of the senior generations of claimants, there was operating a principle of patrilineal descent to which all persons born up to then appeal to legitimise their membership of the total group. The two senior members of sub-group A can, and to my mind do, rely in part upon succession to the country of their deceased mother’s father. All those in the succeeding generations can point to descent through the patriline or the matriline or both, and that, I am satisfied, is the principle of descent which has been operating for two or three generations among this group.

26 The present appellant, Alan Griffiths, was a member of sub-group A and he gave evidence in the course of the Timber Creek Land Claim hearings. The patriline relevant to sub-group A had died out with the death of Lamparangana in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Genealogies showed some four generations below Lamparangana. He was said to have had only one child, a son, who had been killed while young. He was also said to have had a brother, Mangaramawuk, who had a daughter, Clara, who in turn had two children, Alan Griffiths and Mrs Smiler (now deceased). Both Mr Griffiths and Mrs Smiler were claimants in the Timber Creek Land Claim as were their children and grandchildren.

27 His Honour referred to the Commissioner’s findings about other sub-groups. The father country for some of them was Kuwang, better known as Stokes Range, which lay well to the east and south of the claim area. Three patrilineal members of that sub-group had spoken during the hearing before the Commissioner. At [94] his Honour said:

The Commissioner noted that, over and over again, the senior claimants described the responsibility of the whole group for the claim area. He said that he could not find any smaller collection of the claimants who might rightly be identified as having responsibilities of a higher order than the rest of them.

He then quoted a passage from the Commissioner’s report at [101]-[103] (at [94]):

To understand how I arrived at this conclusion, I think it is helpful to state my impression of how the senior claimants perceive and conceptualise the events of the recent past. Firstly, they do identify particular tracts of land with six identifiable patriclans. Secondly, because of the influences and constraints placed upon them over the past 100 years or so by European settlement, Lamparangana’s country must have developed outstanding economic and religious significance for them. Thirdly, at least in that period, secondary rights in and responsibility for country traditionally derived from mother or her male relatives, for co-residence, from marriage and possibly from other sources must have had great significance. Dr Keen’s categorisation of the six sub-groups as together constituting a cognatic kin group serves to emphasise the underlying familial ties that justified the oft made assertion that all the family – meaning all the six sub-groups – were looking after the country now. Fourthly, people asserted a right to Lamparangana’s country in common with other claimants, not by asserting their membership of a group, but by calling upon blood or affinal connections with him. Fifthly, Lamparangana was the last of the line. From what I can gather of the nature of the man, he too must have been very concerned about who would look after the country when he was gone. Sixthly, Little Wally and Takawuk were short on patrilineal descendants to ensure the survival and continuity of the group. Seventh, eminent men like the fathers of Jo and Duncan, the two Micks, and Paddy Bullita had been dispossessed in the sense that their father country had been taken over by the pastoralists and was now no longer as accessible to them.

What I think has happened is that during, if not before, Lamparangana’s time, there was begun a gradual blurring of the distinction between the responsibilities of those who were patrilineally associated with the claim area and those who were not. For their culture to survive it was necessary to accord equal status to the larger cognative kin group. I strongly suspect that the catalyst for this was the need to recognise a successor to Lamparangana’s country.

Whatever the precise dynamics, we now have a group made up of the patrilineal and matrilineal descendants of six old-world patriclans who together constitute the local descent group and as such have undifferentiated, and hence primary, spiritual responsibility for the claim area.

28 His Honour next referred to the Kidman Springs/Jasper Gorge Land Claim Report. This related to a parcel of land comprising an area of approximately 370 square kilometres near Victoria River Downs bounded by the Auvergne stock route and the former pastoral lease known as Delamere. Alan Griffiths was one of the claimants. His Honour noted (at [100]):

After setting out several fundamental aspects of the “Dreaming”, as the claimants used that term, Justice Olney distinguished between the patrilineally inherited relationship, or kuning, and the wider “Dreaming” frequently used by the claimants which encompassed matrilineal identities as well.

29 The Stokes Range Land Claim Report covered an area known by the claimants in that matter as Kuwang. Their language identity was described in the report as Ngaliwurru, although the land under claim did not constitute the full extent of their country. According to Olney J’s report the Ngaliwurru people had maintained extensive ties with neighbouring language groups. Their country was adjacent to that of the Nungali to the north and to the Jaminjung to the north-west. His Honour referred to the report in outline and noted Olney J’s conclusion that the claimants in that case had a responsibility to care for and protect sites in the claim area. Only those with a proper relationship to country could speak for it. All members of the local descent groups had the right to forage over their respective countries. He cited Olney J’s observation that only the claimants had the right to water the heads of strangers to ensure their proper introduction to the country and to its ancestors. In that claim, as his Honour observed, Olney J concluded there was overwhelming evidence to support a finding that the three groups of claimants were the traditional Aboriginal owners of the claim area and could be regarded as a single coherent group with common affiliations and common aspirations.

30 His Honour next turned to the report of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Gray J, in Ngaliwurru/Nungali (Fitzroy Pastoral Lease) Land Claim No 137 and Victoria River (Bed and Banks) Land Claim No 140, Report No 47. The report on these claims was dated 22 December 1993. His Honour cited extensively from it. He referred to passages in which Gray J dealt with the notion of descent criteria and in particular his discussion whether members of a local descent group included those who claimed through their father’s mothers and their mother’s mothers. Gray J said (at [3.2.2]):

It is plain that the recognition of the rights of people to the country of all four grandparents as a matter of course would result in the disappearance within a relatively short time of any notion of separate groups with responsibility for different areas of land. The way in which the claim was put indicates that the claimants have not been so generous in affording recognition of traditional rights.

31 Gray J found that, although there were seven identifiable areas of land each associated with a descent group, the reality was that responsibilities were viewed as shared on a much less strict basis. There was considerable overlapping of areas of land associated with different groups. Gray J also observed that there were no living patrilineal descendants of those whose country was claimed by members of the group known as Makalamayi. Lamparangana had been a respected and active custodian of the country to which that group laid claim. He had no living descendants. His brother, Mangaramawuk was survived by two grandchildren, Alan Griffiths and Mrs Smiler (now deceased). Gray J concluded that they were both entitled to membership of the Makalamayi group. The Makalamayi country was found by Gray J to be heavily based on the town of Timber Creek. Members of the group ranked equally in their obligations and rights whether they had acquired membership through their fathers or through their mothers.

32 Weinberg J reviewed the relevant provisions of the NT Act, case law and principles governing the determination of native title rights and interests. He then essayed a review of the appellants’ evidence. While the testimony of most of the indigenous witnesses was summarised on a thematic basis, Mr Griffiths’ evidence was set out in some detail. His Honour described it as “by far the most important in support of the claimants’ case” (at [154]). His review of that evidence did not include any reference to evidence about the exclusion of strangers save for one passing reference to Mr Griffiths’ explanation of the importance of the head wetting ceremony.

33 His Honour referred to evidence that Mr Griffiths gave about a meeting that took place some time after the death of Lamparangana. The meeting concerned who would take responsibility for Makalamayi. Mr Griffiths said that under traditional law, when someone in Lamparangana’s position died, there had to be discussions about who would succeed him in looking after the country. He recalled a meeting at Kununurra, and possibly another at Timber Creek, on the subject. Those who attended included people from Bradshaw, Yanturi, Gulugulu, Wantawul, Kuwang and Maiyalaniwung. Those who attended agreed that he and his sister, Mrs Smiler, would take over the care of Makalamayi.

34 His Honour looked to evidence of the various witnesses as to their links to Makalamayi. Josie Jones, the sister of a Mr Lewis (now deceased) and the wife of Jerry Jones, said that she took Makalamayi as her country through her connections with Myatt, which was Ngaliwurru land. Her kakung country, from her father’s father, was Yanturi. She said that if somebody wished to build in Makalamayi they would have to “seek permission”. They would have to ask Alan Griffiths, Jo Lewis, Jerry Jones and herself. If Alan Griffiths were not around he would be contacted and generally come to Timber Creek to discuss the matter. His Honour quoted from her evidence:

Makalamayi country is still Griffo’s even if he is not living in Timber Creek. It’s ok to live away from your country, it’s still your country, I can’t change that.

He referred to evidence of head wetting ceremonies given by Mr Georgie Jones, Jerry Jones’ half brother. He conducted head wetting ceremonies at Wunjaiyi and spoke to the various Dreamings in the language for their particular country. His Honour also reviewed the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses in relation to their traditional laws and customs and in relation to language.

35 His Honour turned to a detailed consideration of anthropological evidence beginning with that given by two anthropologists called on behalf of the appellants, Dr Kingsley Palmer and Ms Wendy Asche. The background to their report, its review of anthropological evidence, the claimant community and ancestral and genealogical ties to particular country were referred to. The countries and members of country groups described in the report were also reviewed.

36 Dr Palmer and Ms Asche said that affiliation to country in Timber Creek could be established by applying any one of four descent based principles. A person could take country through his or her paternal grandfather, paternal grandmother, maternal grandfather or maternal grandmother. The first two principles of descent were characterised as patrilineal and the second two principles as matrilineal. An adoptive relationship was regarded as equivalent to one that is consanguineal provided that the adoption was socially sanctioned. A system of this kind where land can pass through either the male or female line is usually described by anthropologists as a cognatic descent system or a cognatic system for short. The majority of the indigenous persons that they interviewed spoke of their father’s father’s country which they termed “kakung” and their mother’s father’s country which they termed “jawajing”. Alan Griffiths had told them that his jawajing country came first but there was a choice and no one way was right. Claims to jawajing were described by the anthropologists as indirectly patrilineal, filiation being via the female line for potentially only one generation. His Honour observed that this was somewhat confusing given that the relationship is in fact matrilineal. Not all of the appellants’ witnesses agreed with Alan Griffiths. Mr Lewis and Josie Jones told the anthropologists that they regarded jawajing country as in some respects subsidiary to kakung country.

37 His Honour referred to the findings of Commissioner Maurice in the Timber Creek Land Claim and said that they raised the issue of whether there had been a significant change in the way in which country groups were now recruited (at [349]):

Put at its most simple, were country groups pre-contact recruited patrilineally? Is there evidence that this was so? Does the change to a cognatic system indicate a fundamental alteration to the manner of recruitment to the country group? Does ‘patrilineal bias’ indicate a preference for claiming patrifiliation founded upon historical principles?

Their anthropologist’s evidence was that neither the anthropological evidence nor scholarly literature provided a concluded or agreed view on those questions. Until 20 years or so ago there was an assumption among anthropologists that country groups were patrilineally recruited. Evidence produced as a result of extensive research into land claims had shown that this may not have been the case. It was now clear that rights to country could be gained in a number of ways of which patrilineal descent was but one. The evidence presented in the various land claims around Timber Creek was consistent with cognatic descent having become a common principle by which people expressed affiliation to country. Nevertheless patrifilial descent had been, and still was, an important means whereby people in Timber Creek affiliated to country. His Honour quoted what he regarded as a critical observation by Dr Palmer and Ms Asche (at [353]):

There may have been a shift over time, and the number of patrifiliates has decreased while the number of matrifiliates has increased. However, and in our view, the normative system underpinning the acquisition of rights to land has not changed, only its emphasis.

They disagreed with the observation in the Timber Creek Land Claim Report that the original patriclans had collapsed into a single group making up the claimant community.

38 His Honour also outlined the anthropologists’ evidence about the rights and duties of members of country groups. He drew from it that members of the country groups that they identified had various gradations of rights of ownership. These included access rights, exclusion rights, rights relating to intellectual property and “use and benefit rights”. Duties were propounded including a duty to protect country, to care for country and to care for visitors. They referred to Mr Griffiths’ evidence in which he spoke of Ngaliwurru and Nungali people “sharing” Makalamayi. His Honour said (at [362]):

Mr Griffiths said that the members of each of the five country groups in question could enter the other countries freely, without asking permission of anyone. The only constraint applied to women who would have to ask first in order to make sure that they did not contravene any secret ritual business. Members of other groups, including, for example, the Ngaringman, would need to ask first, unless they were travelling for Winan, in which case, they could enter Ngaliwurru and Nungali country freely.

And at [365]:

In the authors’ view, all members of the claimant group were entitled to use the resources of the claim area. However, that entitlement was tempered by “a spiritual reality” which explained why some people were reluctant to venture too far into country without the guidance of others. For strangers, such guidance was essential. In effect, asking permission was irrelevant because to go somewhere unknown, without that guidance, would be to court disaster.

39 The next element of the appellants’ anthropologists’ evidence that his Honour considered was the continuity of connection with country. He quoted extensively from the report. One paragraph quoted was in the following terms (at [377]):

The ways in which the applicants consider themselves to be owners of areas of country (which includes, but is not limited to) the application area, furnishes them with rights to that country. The exercise of these rights is observable in practice and includes access rights, the right to control the access of others, rights to the resources of the country, rights to the intellectual property associated with the country and the assumption of roles in ritual. Exercise of these rights is hedged round with rules and requirements, which are considered to be imbedded within the applicants’ culture.

40 His Honour set out what he described as “key points” arising from the summary of the evidence given by Dr Palmer and Ms Asche (at [378]):

. descent is the primary principle for reckoning membership of country groups, and this has been so since before European contact;

. descent at Timber Creek is cognatic, though there is some preference for claiming country via patrifiliation;

. it is likely that there has been a move away from patrifiliation to cognatic descent over the past two or three generations;

. the claimants share a belief in the spirituality of the Dreaming, and have traditional beliefs, practices, concepts and ways of doing things that render them a distinctive culture, and a homogenous community;

. given the complexity, and rich nature of the social relationships that exist, it is unlikely that these have emerged in recent times;

. Dreaming and spirituality are considered to be contemporary manifestations of past events during which culture was ordained. Knowledge of these things has been handed down from generation to generation; and

. though the early literature available for the Timber Creek area does not demonstrate conclusively that the system of laws and cultural rules that applies today would have been found in the community at the time of first contact, still less in 1825, it is the authors’ view that the claimants’ “culture and the rules that mould it are, in all probability, based upon a traditional system that predates sovereignty.

41 His Honour then reviewed the anthropological evidence called for the Northern Territory. This was given by Professor Basil Sansom, whom his Honour described as “a distinguished anthropologist”. Professor Sansom’s lengthy report responded to and critically evaluated the report prepared by Dr Palmer and Ms Asche. He relied heavily upon the findings of Professor WEH Stanner, based upon his contact with the people of the Victoria River region in 1934 and 1935. Professor Stanner had concluded that the people were all of the patrilineal totemic clan. Professor Sansom regarded that finding as unassailable. He viewed the shift to cognation at Timber Creek as a reactive adjustment to population loss, displacement, relocation and the mixing together of Aboriginal populations on an unprecedented scale. The people had been required to develop survival strategies in the face of an overwhelming settler presence and the takeover of their lands. Professor Sansom cited a work by Professor Peter Sutton “Native Title in Australia: An Ethnographic Perspective” (2003). He took from that work the thesis that the emergence of cognatic descent groups constituted an aspect of “post-classical social organisation” and was a revised normative system of “post-classical kinship”. Patrilineal people moving to cognatic kinship experience a collapse of clan structure. Distinctly defined estate groups disappear. There is a revision of the sacred and totemic geography of the “tribe” or language-owning group. Ownership is claimed not on an estate basis but as ownership of a “language country” or “tribal territory”. Cognation diversifies and generalises interests in country, while traditional patriliny concentrates rights and interests in estates.

42 His Honour observed that having made these points Professor Sansom did not identify any factors that might indicate that such revolutionary changes had occurred at Timber Creek. His examples of the process were Darwin and Katherine, both large towns and “vastly different” to Timber Creek. Professor Sansom’s conclusions, if accepted, would cast doubt upon the existence of the native title claim group as pleaded and therefore upon whether there were communal native title rights and interests of the type alleged. They would cast doubt upon whether any rights and interests shown to exist were possessed under “the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed” by the claimants. They would at least substantially weaken the contention that the claimants “by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters” (at [438]). His Honour also reviewed Dr Palmer’s rebuttal of Professor Sansom’s evidence.

43 His Honour set out his findings of fact. He was satisfied on the basis of the evidence of the indigenous witnesses, supported by the historical material “and also by the findings of the various Land Commissioners” that the native title claim group constituted a society bound together by adherence to traditional laws and customs. He was also satisfied that they were linked to the claim area through ancestral ties going back to Lamparangana and well before his time. They continued to acknowledge traditional laws and to observe traditional customs in much the same way as their ancestors did over many generations. His Honour identified the real factual dispute in the case as turning upon the interpretation to be placed on primary facts adduced from the indigenous witnesses. He accepted the evidence of Dr Palmer and Ms Asche in preference to that of Professor Sansom. Dr Palmer and Ms Asche had a very real advantage because of their extensive involvement with the members of the claimant group over many years and the empirical foundations for their report. Professor Sansom although having had considerable experience in other parts of Australia, had little direct involvement with those in the region around Timber Creek. His analysis was largely theoretical and extrapolated from his work in other communities. He had accorded undue deference to the early work of Professor Stanner.

44 His Honour found Mr Griffiths was regarded by the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples as a leading figure in Timber Creek in matters of ritual and ceremony. The evidence established that in that area local proprietorial interests determine what a man might legitimately do in the performance of such ritual and ceremonial matters. There was a normative system in place in relation to those matters and substantially the same normative system has existed for generations. The restrictive evidence, in particular, pointed to a link between symbols of the higher order ritual, and proprietary interests in land.

45 Importantly his Honour rejected the proposition that there had been a fundamental change in the normative system governing rights to country in the claim area. There had been a gradual shift from a patrilineal to a cognatic system and the shift was continuing. The crucial point was that rights to “country” in Timber Creek were and always had been based upon principles of descent. The shift to cognation was one of emphasis and degree. It was not a revolutionary change giving rise to a new normative system.

46 His Honour considered the identification of the claimant group. There was no real dispute in the case as to the ancestral connection between what might be termed the original native title holders and the current claimants. Biological descent was plainly established. The issue that divided the parties was whether there had been a fundamental change in the normative system underlying the acquisition of native title from a patrilineal descent system to a cognatic descent system and, if so, whether that prevented the claimants from maintaining a traditional connection with the land in accordance with traditional laws and customs. He had resolved that issue in favour of the claimants.

47 His Honour then considered the requirement of connection which he said did not loom large in that case. The appellants’ group occupied the area in and around Timber Creek not randomly but because their forebears occupied the region generations ago.

48 In the event, his Honour was satisfied that the appellants had established that they possessed native title rights and interests in the claim area as defined in s 223(1) of the NT Act. He was able to also infer continuity of the community and its connection back to the time of sovereignty (at [577]):

It is reasonable to infer that the indigenous people who inhabited the Timber Creek region in about the middle of the nineteenth century, and who acknowledged and observed essentially the same laws and customs as do the present claimants did not simply invent them. There is nothing in the evidence to suggest that the ritual and ceremonial practices observed by the inhabitants of this area since about that time, in a largely unbroken pattern, were suddenly created, or radically transformed from what had gone immediately before. The ethnography, and the few contemporary records that are available, support the conclusion that this pattern has evolved over hundreds of years.

49 His Honour found the senior claimants had established that they were the direct descendants of a group of indigenous inhabitants of the area around Timber Creek and that they observed essentially the same rituals and ceremonies as were practised by their ancestors more than a century ago.

50 His Honour next turned to consider the nature of the native title rights and interests held by the claimants. The critical issue was whether or not their rights and interests were to be regarded as “exclusive”. Both the Northern Territory and the AFANT submitted that if native title were found to exist, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the claim area were not “exclusive” but rather usufructuary in nature. His Honour undertook a general discussion of the principles underlying the definition of native title rights and interests. He said (at [614]):

The question to be determined in these proceedings is whether the native title rights and interests of the claimants that have been established rise significantly above the level of usufructuary rights. In my view, that question should be answered both “yes” and “no”. The evidence in this case establishes both usufructuary and proprietary rights. However, it falls short of establishing native title rights and interests in relation to the claim area “to the exclusion of all others”. It also falls short of establishing an unfettered right on the part of the claimants to control others’ access to that area, or to control others’ use and enjoyment of the resources of that area.

51 His Honour acknowledged that some indigenous witnesses who gave evidence had spoken of a yakpalimululu as someone who could “deny others access to certain foraging areas”. Josie Jones had given evidence that if someone wanted to build in Makalamayi they would have to ask permission. If a white person wanted to go on to the land, that person would be expected to ask permission first. The purpose would be to enable important sites to be identified to the visitor presumably so they might be protected. Mr Harrington had given evidence about those who had to be consulted in relation to any activities at Timber Creek. His Honour observed that a number of other witnesses also gave evidence about the process of consultation that had been followed in relation to a proposed mine that did not proceed because of its proximity to a site of significance. Jerry Jones had told Dr Palmer and Ms Asche that he regarded himself as entitled to fish, camp, take ochre and induct strangers. Indigenous persons not members of the Ngaliwurru-Nungali community were expected to “ask permission” before doing any of those things. However, he regarded seeking permission as irrelevant because in practice no indigenous person would wander about on the land without the guidance of a member of the community. His Honour referred (at [619]) to what he called “scattered references” in the anthropological material which “hint at” the need to obtain permission before entering the land. He did not consider that they justified a finding that the appellants had exclusive rights. His Honour regarded theevidence supporting the right to exclude others from using the waters of Timber Creek as, if anything, even weaker than that in relation to land.

52 The next issue relevant to the cross-appeal concerned the extinguishing effects of historical pastoral leases and whether s 47B of the NT Act could be invoked to overcome that extinguishment. His Honour found that the tenure history of the claim area and the fact that it was all previously covered by pastoral leases made it plain, that subject to the possible operation of s 47B of the NT Act, native title had been extinguished. If s 47B had the effect to which the appellants were contending, it was unnecessary to resolve the question whether such extinguishment would otherwise be total, or only partial. The reason would be that, pursuant to s 47B extinguishment would simply be disregarded.

53 His Honour then considered the application of s 47B and cases dealing with it and, in particular, the recent decision of the Full Court in Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442. Applying that decision, which is discussed later in these reasons, his Honour concluded that s 47B applied to Timber Creek notwithstanding its proclamation as a town and the setting aside of Crown lands within its boundaries in May 1975. That proclamation was made under s 111 of the Crown Lands Ordinance 1931-1972 (NT) (the Ordinance).

54 His Honour considered the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests for the purposes of his determination under s 225. He returned to the question of exclusivity. He said (at [714]- [715]):

As I have already indicated, the evidence in the present case goes no further, in my view, than to establish that the claimants have been asked, on occasion, by other indigenous people wishing to come upon their land for “permission” to do so. The evidence is somewhat obscure, but suggests that these requests are made as a matter of prudence, because visitors would be at risk if they were simply to go upon the land without seeking permission, and without obtaining guidance and assistance.

The ongoing normative system regarding relationship to country that the evidence before me discloses does not fit the template of a right to possess “to the exclusion of all others”. Nor does it suggest a general right to “control access” to the land in any relevantly proprietorial sense. In reality, the claimants seem to me to assert a right, under their traditional laws and customs, to be consulted about matters that might harm the land, and a right to veto any activity which might be detrimental. This falls well short of the broader claim that is pleaded, to possess the land to the exclusion of all others.

His Honour then considered the waters of Timber Creek and summarised his findings.

55 On 28 August 2006 his Honour made the determination which is attached to these reasons.

Grounds of Appeal

56 The notice of appeal raised the question whether his Honour erred in holding that the appellants’ native title rights and interests were non-exclusive. The grounds were formulated as follows:

(1) In holding that the rights and interests possessed under the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders do not confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the determination area on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others, the primary Judge erred in considering that:

(a) as rights on the part of the native title holders under their traditional law and custom to be asked permission and to speak for country served purposes relating to the safeguarding of country and the protection of strangers to country, the content and operation of the rights was thereby limited to those purposes and did not extend to the exclusion of all persons other than the native title holders (reasons, [615], [619], [714]-[715], [717]);

(b) rights on the part of the native title holders under their traditional law and custom to be consulted about matters that might harm country, and to veto any activity that might be detrimental to country, does not fit the template of a right to possess land to the exclusion of all others, nor does it suggest a general right to control access to land in any relevantly proprietorial sense (reasons, [715]);

(c) it was necessary to establish that rights on the part of the native title to control or restrict access to country had been exercised against strangers to country (reasons, [616], [619]-[620], [714]).

2. The primary Judge erred in not finding that the rights and interests possessed under the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the determination area on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Proposed variations to the determination

57 Counsel for the appellants handed up, during the hearing of the appeal, a document entitled “Proposed Variation of Native Title Determination”. Variations to the determination set out in the document differed from those sought in the notice of appeal. The document was received as an amendment to that notice.

The cross-appeal by the Northern Territory

58 The Northern Territory raised three issues on its cross-appeal:

1. Whether, having found there had been a shift from principles of patrilineal descent to principles of cognatic descent, his Honour erred in holding that the native title claim group continued to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs giving rise to rights and interests in relation to land.

2. Whether his Honour erred in holding that s 47B of the NT Act applied to the area within the proclaimed boundaries of the town of Timber Creek so that any extinguishment of native title rights and interests by the creation of prior interests in that area could be disregarded; and

3. Whether one area, Lot 47, previously the subject of Crown Lease Term 624 granted under the Crown Lands Act 1931 (NT) was a previous exclusive possession act under s 23B of the NT Act and thus expressly excluded from the area covered by the native title determination application.

The Northern Territory’s first notice of contention

59 The Northern Territory filed a notice of contention in support of his Honour’s finding that the native title rights and interests were non-exclusive. Rather than relating to the content of the indigenous and anthropological evidence, this contention relied upon the extinguishing effects of prior grants of pastoral leases on any exclusive elements of the native title rights and interests. This extinguishment, it was said, could not be disregarded by reason of s 47B of the NT Act. His Honour was said to have erred in finding that that section did apply to the area within the proclaimed boundaries of the town of Timber Creek so as to enable disregard of the previous grant of pastoral leases.

The Northern Territory’s further notice of contention

60 In responding to the appellants’ arguments about exclusivity counsel for the Northern Territory sought to support the judgment of the learned primary judge on the basis that the native title claim group was not exhaustive of persons entitled, under traditional law and custom, to exercise rights in respect of the determination area. The Court pointed out that this argument should have been the subject of a notice of contention. Subsequently, during the hearing of the appeal, the Northern Territory submitted a “Notice of Further Contention”. It proposed that subject to the matters raised in the cross-appeal the judgment should be affirmed “on grounds other than those relied on by the court below”. The grounds were:

1. His Honour erred in not finding that the native title claim group identified in the amended Native Title Determination Application did not constitute all Ngaliwurru/Nungali peoples entitled under traditional law and custom to exercise rights in respect of the determination area.

2. On this additional basis the judgment and determination appealed from should be affirmed insofar as it finds and determines that:

2.1 the native title rights and interests which are held in the determination area are non-exclusive rights to use and enjoy land and waters; and

2.2 the native title rights and interests which are held in the determination area do not confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land and waters of the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Statutory framework – native title rights and interests

61 Section 223 of the NT Act provides, inter alia:

Common law rights and interests

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Hunting, gathering and fishing covered

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), rights and interests in that subsection includes hunting, gathering, or fishing, rights and interests.

The remaining subsections are not material for present purposes.

62 Section 225 provides:

Determination of native title

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease – whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Whether the finding of non-exclusivity involved an error of principle

63 The learned primary judge held that the evidence in the case fell short of establishing native title rights and interests, in relation to the claim area, to the exclusion of all others. The appellants first contended in their written submissions that his Honour had erred “in principle”. The error in principle asserted was the use of criteria for characterisation of native title rights and interests that were relevant to property rights at common law. The appellants relied upon the statement in Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1 (at [11]):

Because native title has its origin in traditional laws and customs, and is neither an institution of the common law nor a form of common law tenure, it is necessary to curb the tendency (perhaps inevitable and natural) to conduct an inquiry about the existence of native title rights and interests in the language of the common law property lawyer.

The appellants submitted that the inquiry which his Honour undertook was whether the rights and interests held by the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs were “akin to rights that are usufructuary in nature” (at [588]) or “rise significantly above the level of usufructuary rights” (at [614]). That inquiry, it was said, was undertaken to determine whether the “incidents of the native title rights and interests that have been demonstrated are ‘exclusive’” (at [602]). The approach so formulated was said to be erroneous.

64 Section 223 of the NT Act indicates that native title rights and interests are “communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders” which meet the criteria in paras 1(a), 1(b) and 1(c) of that section. To ascertain the existence of such rights and interests requires no application of the taxonomies of the common law of property. Nor is it required in the definition of native title rights and interests for the purposes of a determination of native title in the form required by s 225.

65 His Honour identified “the question to be determined in these proceedings” as “whether the native title rights and interests of the claimants that have been established rise significantly above the level of usufructuary rights” (at [614]). That question appears to have had a direct bearing on whether those rights and interests could be regarded as exclusive. The significance of the usufructuary/proprietary distinction in this context is not clear. The concept of usufructuary rights is derived from Roman law. A usufruct is “a right to use and enjoy the fruits of another’s property for a period without damaging or diminishing it, although the property might naturally deteriorate over time”: Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed), Thomson West at 1580.

66 In warning against approaching native title conceptually in terms appropriate to English law, Viscount Haldane said in Amodu Tijani v Secretary, Southern Nigeria [1921] 2 AC 399 (at 403):

A very usual form of native title is that of a usufructuary right, which is a mere qualification of or burden on the radical or final title of the Sovereign where that exists. In such cases the title of the Sovereign is a pure legal estate, to which beneficial rights may or may not be attached. But this estate is qualified by a right of beneficial user which may not assume definite forms analogous to estates, or may, where it has assumed these, have derived them from the intrusion of the mere analogy of English jurisprudence.

In The Administration of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea v Daera Guba (1973) 130 CLR 353 at 397 Barwick CJ referred to the native title of Papua New Guinean people after declaration of the Protectorate or annexation by the British Crown as “usufructuary”. He identified what he called “the traditional result of occupation or settlement” namely:

...though the indigenous people were secure in their usufructuary title to land, the land came from the inception of the colony into the dominion of Her Majesty. That is to say, the ultimate title subject to the usufructuary title was vested in the Crown. Alienation of that usufructuary title to the Crown completed the absolute fee simple in the Crown.

(McTiernan, Menzies and Stephen JJ agreed with Barwick CJ’s reasons).

67 The characterisation of native title as usufructuary in the sense used in Amodu Tijani [1921] 2 AC 399 and in Daera Guba 130 CLR 353 does not preclude the inclusion in it of exclusive rights of possession, occupation and use arising under traditional law and custom. If it be the case that native title rights are usufructuary because they involve, at common law, the right to use the sovereign’s land then the usufruct may incorporate rights to exclude others from the land. The sovereign of course in the exercise of its executive or legislative authority may extinguish such rights but that possibility does not preclude their characterisation as exclusive. The passage quoted from the judgment of Viscount Haldane was quoted with approval in the joint judgment in Yarmirr 208 CLR 1 at [11].

68 In Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 61, Brennan J said that native title rights and interests established by evidence might be “proprietary or personal and usufructuary in nature”. In Wik Peoples v State of Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 at 169, Gummow J adverted to the variable content of native title rights:

It may comprise what are classified as personal or communal usufructuary rights involving access to the area of land in question to hunt for or gather food, or to perform traditional ceremonies. This may leave room for others to use the land either concurrently or from time to time. At the opposite extreme, the degree of attachment to the land may be such as to approximate that which would flow from a legal or equitable estate therein.

69 Young J in the Supreme Court of New South Wales considered the concept of “usufruct” and “usufructuary right” in Mason v Tritton (1993) 6 BPR 13,639. An Aboriginal man had been convicted of having in his possession a quantity of abalone beyond permitted limits. The defence turned on the man’s claim to have a native title right, recognised by the common law, to fish in the relevant waters. Young J dismissed an appeal against the conviction. An appeal against his decision was in turn dismissed by the Court of Appeal in Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572. Young J referred to the Roman law understanding of a usufruct as a right to the use and fruits of another’s property and the duty to preserve its substance (13,641). He observed that, in the context of traditional native title, it had been used to describe hunting and fishing rights on land or waters over which the whole of the country did not have dominion and (at 13,642):

includes the situation where a community of people have the dominion over a piece of land but individuals, because they are members of the community, also may avail themselves of the right.

After citing and quoting from Crocombe’s Land Tenure in the Cook Islands (1964) he concluded:

Thus it would appear that most commonly the words “usufructuary right” denote the right of a member of a community or tribe which is not the group primarily connected to the land to use the land for certain purposes. Such purposes usually mean hunting or fishing or gathering fruits, nuts and other produce.

His Honour observed that although Brennan J in Mabo (No 2) referred to native title as “proprietary, usufructuary or otherwise”, the Mabo decision was concerned only with land rights (at 13,642).

70 In the Court of Appeal, Priestley JA (Gleeson CJ agreeing) decided the case on the basis that there was no evidence of any recognisable system of rules governing the taking of abalone. Kirby P came to a similar conclusion. He understood Brennan J in Mabo (No 2) to have referred to a usufructuary right as a right to enjoy a thing in which the holder of a right had no proprietary interest (at 581):

... where Brennan J in Mabo speaks of the ability of the common law of Australia to recognise and protect usufructuary rights, his Honour is there clearly enough referring to the fact that native title to the use, possession and occupation of land is normally held by a community. An individual’s right to derivative use and benefit of that land is capable of protection in a manner analogous to the protection traditionally afforded to a usufructuary right.

His Honour regarded that which Brennan J described as “usufructuary right[s]” as “dependent upon the wider native title to land being established” (581).

71 The judgments referred to above are sufficient to indicate that the use of the common law taxonomy of usufructuary and proprietary rights in ascertaining the content of native title rights and interests involves a risk of confusion and distraction from the requirement to have regard to what the evidence says about the nature of the native title rights and interests in question. In our opinion the question whether the native title rights of a given native title claim group include the right to exclude others from the land the subject of their application does not depend upon any formal classification of such rights as usufructuary or proprietary. It depends rather on consideration of what the evidence discloses about their content under traditional law and custom. It is not a necessary condition of the existence of a right of exclusive use and occupation that the evidence discloses rights and interests that “rise significantly above the level of usufructuary rights”. With respect, the question posed by his Honour was unnecessary and had the potential to lead into error. It appears that, when his Honour went on to consider the evidence relevant to the existence and content of the native title rights and interests held by the appellants and those on whose behalf they brought the application, classificatory considerations may have affected his characterisation of those rights and interests. His observation(at [715]) that the “ongoing normative system regarding relationship to country” did not suggest “... a general right to “control access” to the land in any relevantly proprietorial sense” conveys that appearance. This leads on to the second limb of the appellants’ argument which is that his Honour erred in fact having regard to the evidence which he accepted. It requires consideration of the evidence at trial relevant to control of access to the determination area.

Evidence at trial relevant to exclusivity of native title rights and interests

72 The Court was referred by counsel for the appellants to the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses said to go to exclusivity and to relevant parts of the anthropological expert testimony. The expert testimony offered an overview of the traditional laws and customs of the appellants’ community which reflected what appeared in the evidence of individual witnesses.

73 Dr Palmer and Ms Asche said in their report that the appellants identified with named areas of country called yakpali. They identified five country groups, Makalamayi, Wunjaiyi, Yanturi, Wantawul and Maiyalaniwung. The term yakpalimululu referred to an owner of country and was often used synonymously with the English word “boss”. Of yakpalimululu they said: