AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

Application by DBNGP (WA) Transmission Pty Ltd [2018] ACompT 1

IN THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

RE: | APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 245 OF THE NATIONAL GAS ACCESS (WESTERN AUSTRALIA) LAW FOR A REVIEW OF THE DECISION MADE BY THE ECONOMIC REGULATION AUTHORITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TO GIVE EFFECT TO ITS PROPOSED REVISIONS TO AN ACCESS ARRANGEMENT FOR THE DAMPIER TO BUNBURY NATURAL GAS PIPELINE, PURSUANT TO RULE 64 OF THE NATIONAL GAS RULES | ||

APPLICANTS: | DBNGP (WA) TRANSMISSION PTY LTD (ACN 081 609 190) ON ITS OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF DBNGP (WA) NOMINEES PTY LTD (ACN 081 609 289) AS TRUSTEE OF THE DBNGP WA PIPELINE TRUST, AND DBNGP (WA) NOMINEES PTY LTD (ACN 081 609 289) AS TRUSTEE OF THE DBNGP WA PIPELINE TRUST | ||

TRIBUNAL: | MR ROBIN DAVEY (MEMBER) MR RODNEY SHOGREN (MEMBER) |

DATE OF DETERMINATION: |

THE TRIBUNAL DETERMINES THAT:

1. The Application for Review the subject of leave granted to the applicants by the Tribunal on 13 February 2017 be dismissed.

2. The designated reviewable regulatory decision, being the final decision of the Economic Regulation Authority of Western Australian published on 30 June 2016 on Proposed Revisions to the Access Arrangement for the Dampier to Bunbury natural gas pipeline for the regulatory period 2016-2020, is affirmed.

[1] | |

[16] | |

[29] | |

[42] | |

[42] | |

[42] | |

[47] | |

[79] | |

[95] | |

[124] | |

[141] | |

[142] | |

[196] | |

[229] | |

[257] | |

[297] | |

[297] | |

[306] | |

[321] | |

[329] | |

[350] | |

[352] | |

[353] | |

[357] | |

[358] | |

[362] |

REASONS FOR DETERMINATION

THE TRIBUNAL:

1 On 30 June 2016, the Economic Regulation Authority of Western Australia (ERA) published its final decision and its reasons for that decision (the final decision) on Proposed Revisions to the Access Arrangement for the Dampier to Bunbury Natural Gas Pipeline (the pipeline) for the regulatory period 2016–2020 (the current regulatory period). 2016–2020 was the fourth regulatory period in respect of the pipeline which has been the subject of regulation by the ERA.

2 The final decision was made pursuant to the National Gas Law (NGL), as implemented in Western Australia by the National Gas Access (WA) Act 2009 (WA) (the WA Act), and the National Gas Rules (NGR), as enacted by the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 (SA) and as implemented in Western Australia by the WA Act. The NGR have the force of law in Western Australia (see s 26 of the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law (NGL(WA)). In Western Australia, the underlying NGL as modified from time to time applies as the NGL(WA). The text of the NGL(WA) is set out in Schedule 1 to the WA Act. Section 9(1) of the WA Act provides that “National Gas Law” or “this law”, when used in the NGL(WA) and in the National Gas Access (WA) (Part 3) Regulations (Regs), means the NGL(WA).

3 The final decision addressed an amended revised access arrangement proposal (the owners’ amended proposal) which had been submitted to the ERA by the owners of the pipeline on 22 February 2016.

4 The owners of the pipeline are DBNGP (WA) Transmission Pty Ltd, acting on its own behalf and on behalf of DBNGP (WA) Nominees Pty Ltd as trustee of the DBNGP WA Pipeline Trust, and DBNGP (WA) Nominees Pty Ltd as trustee of the DBNGP WA Pipeline Trust. We shall refer to these corporations as “the owners”.

5 On 21 July 2016, the owners filed an application for the grant of leave under s 245 of the NGL(WA) to apply to review the final decision (Review Application). That decision was a “reviewable regulatory decision” and a “full access arrangement decision” made by the ERA in relation to the pipeline. The final decision was made pursuant to r 64 of the NGR.

6 In their Review Application, the owners sought leave to review four matters.

7 On 13 October 2016, the owners informed the Tribunal that they did not wish to press their application in respect of two of those four matters viz ground (iii) (the Subsequent Costs (non-turbine reactive maintenance) ground) and ground (iv) (the Definition of the P 1 Reference Service ground).

8 After the abandonment of the grounds of review referred to at [7] above, there remained for determination by the Tribunal grounds (i) and (ii). Those grounds concern:

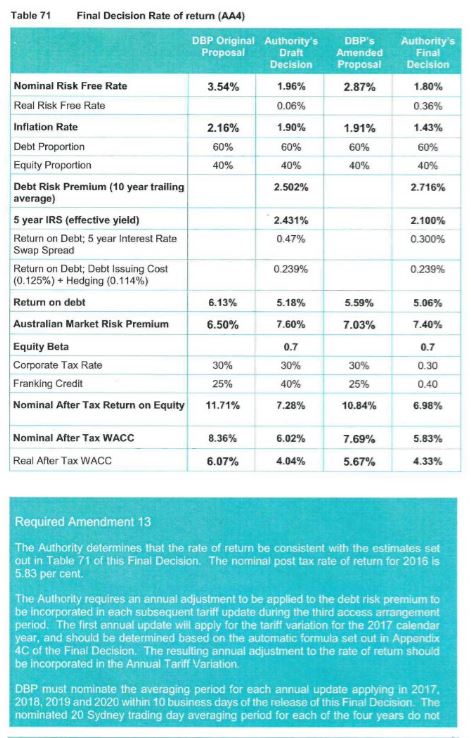

(a) The ERA’s determination of a nominal after tax return on equity of 6.98%, resulting in a nominal after tax weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of 5.83% (the ROE decision); and

(b) The ERA’s determination of a value for imputation credits (gamma) of 0.4 (the gamma decision).

9 In their Review Application, the owners explained their contentions in respect of the ROE decision in Annexure 1 to that Application and in respect of the gamma decision in Annexure 2 to that Application.

10 Immediately before the commencement of the hearing of the Review Application, which commenced at 10.15 am on 13 February 2017, the Tribunal directed that the owners have leave to apply to the Tribunal for a review of the ROE decision and the gamma decision. At the time when it made that direction, the Tribunal informed the parties that it would provide reasons for its decision to grant that leave as part of its Reasons for Determination which would be published in due course in support of its decision in respect of grounds (i) and (ii) raised by the owners in their Review Application.

11 The pipeline is Western Australia’s key gas transmission pipeline, extending over some 1,539 km underground. It originates at a point immediately adjacent to the North West Shelf Joint Ventures Domestic Gas Plant on the Burrup Peninsula in the Pilbara region of Western Australia and passes through the Perth metropolitan area, Kwinana, Pinjarra and Wagerup, ultimately terminating at Main Line Valve 157 which is located at Clifton Road, north of Bunbury, in the south-west region of Western Australia.

12 The pipeline is an “old scheme covered pipeline”, a “scheme pipeline” and a “covered pipeline” under the WA Act, the NGL(WA) and the NGR. It is also a “designated pipeline” within the definition of “designated pipeline” in s 2 of the NGL(WA) (see s 4 of the National Gas Access (WA) (Part 3) Regulations 2009 and cl 2(1) of Sch 1 to those Regulations).

13 Each of the owners is a “service provider” within the meaning of s 8 of the NGL(WA). This is because the owners own, control and operate a scheme pipeline.

14 The pipeline is an ERA pipeline within the meaning of that expression as defined in s 9(1) of the WA Act. For this reason, the ERA is designated as the relevant regulator (see the definition of “regulator” in s 9(1)).

15 Section 27 of the NGL(WA) prescribes the functions and powers of the ERA. The ERA is responsible for the economic regulation of pipeline services provided by service providers (such as the owners) by means of or in connection with a scheme pipeline. In particular, under Pt 9 of the NGR, the ERA is responsible for determining the total revenue for each regulatory year of an access arrangement period which the owners may earn for the provision by the owners of pipeline services through the pipeline.

16 On 31 December 2014, the owners submitted to the ERA proposed revisions to the access arrangement for the pipeline (the owners’ original proposal). That proposal was submitted to the ERA pursuant to r 52 of the NGR.

17 Under the NGR, the role of the ERA was to approve, or not approve, the proposed revised access arrangement contained in the owners’ original proposal in accordance with the NGL(WA) and the NGR.

18 On 20 April 2015, the ERA published an issues paper in response to the owners’ original proposal and, at the same time, invited submissions from interested parties. Some submissions were received.

19 On 22 December 2015, the ERA published its Draft Decision in relation to the owners’ original proposal (draft decision). The draft decision was not to approve the owners’ original proposal. In its draft decision, the ERA said that the owners had to make 74 amendments to their proposal before it would approve the access arrangement contained therein. At the same time, the ERA invited the owners to submit revisions to their original proposal and to do so by 22 February 2016.

20 On 22 February 2016, the owners submitted their amended proposal. At the same time, they also provided supporting information to the ERA.

21 The ERA then invited public submissions in respect of its draft decision and in respect of the owners’ amended proposal. The closing date for such submissions was 22 March 2016. Three interested parties made submissions to the ERA as did the owners.

22 The ERA subsequently invited a further round of public submissions in relation to a matter which had not been considered in the draft decision. Further submissions were received from the owners and from one other interested party.

23 At pars 9–14 of its final decision, the ERA made the following remarks concerning the process which it had undertaken in dealing with the owners’ application to have revisions made to the access arrangement in respect of the pipeline:

9. Section 28(1) and (2) of the NGL(WA) were substantially amended in 2013 to require the Authority to specify how the constituent components of this Final Decision related to each other and how the Authority has taken those interrelationships into account. Subsequent to these amendments, the NGL now anticipates that there may be more than one possible decision that will or is likely to contribute to the achievement of the NGO. In such cases, the Authority must make the decision that will or is likely to contribute to the achievement of the NGO to the greatest degree, and provide reasons.

10. The NGL(WA) does not prescribe how the Authority is to apply the requirements and, as a result, the Authority has used its regulatory judgement. The Authority has applied these requirements by determining total revenue and reference tariffs in accordance with the detailed requirements of the NGR.

11. The Authority’s Final Decision is complex and many of the components of the decision are interrelated. The adoption of a value for a component has implications for other elements or values elsewhere in the decision. For example:

• the value of imputation credits (gamma) has an impact on the estimated cost of corporate income tax;

• the value of imputation credits (gamma) has an impact on the estimate of the return on equity, through the estimates of the market risk premium;

• the definition of the benchmark efficient entity has strong links to all aspects of the rate of return, including:

– the composition of the benchmark efficient sample;

– the relevant estimation methods, financial models and market data and other evidence used for estimating the return on equity and the return on debt;

– the gearing;

– beta;

– the credit rating; and

– the debt risk premium;

• the return on debt is considered in conjunction with the return on equity, to ensure consistency;

• the definition of the benchmark efficient entity also has implications for whether to revalue the RAB at each access arrangement revision;

• the service provider’s governance arrangements and risk management will affect most aspects of the proposal, including capital and operating expenditure forecasts; and

• the approved demand forecasts will affect the calculation of reference tariffs.

12. In making its decision in accordance with the detailed requirements of the NGR and being mindful of any interrelationships between components, the Authority considers that it has made a Final Decision that will or is likely to contribute to the achievement of the NGO to the greatest degree. The Authority’s assessment is set out in the following sections of this Final Decision.

13. After considering DBP’s amended proposal and its supporting submissions, the submissions from other interested parties, and advice from the Authority’s technical and economic advisors, the Authority’s Final Decision is not to approve the amended proposal. The Authority’s reasons for refusing to approve the amended proposal are set out in this Final Decision.

14. Under rule 64 of the NGR, when the Authority refuses to approve an access arrangement proposal, the Authority is required to itself propose revisions to the access arrangement and make a decision giving effect to its proposal within two months of its Final Decision.

24 The above remarks accurately capture the fundamental features of the regulatory task which the ERA was obliged to perform.

25 In the present case, as permitted by r 64(3) of the NGR, the ERA decided not to consult on its ultimate access arrangement proposal. Instead, the ERA, as part of the final decision, made a decision giving effect to its access arrangement proposed under r 64(4) of the NGR. That decision is a “reviewable regulatory decision” (see the definition in s 2 of the NGL(WA) and s 244 of the NGL(WA)). It is also a “designated reviewable regulatory decision” (see the definition in s 2 of the NGL(WA)).

26 Pursuant to r 64(6) of the NGR, the revisions to the access arrangement made by the ERA took effect from 1 July 2016.

27 The ERA included within the final decision its proposed revisions to the owners’ amended proposal and its own revisions to the access arrangement.

28 Some minor corrections were made to the final decision on 20 July 2016. The form of the final decision under consideration in the present matter incorporates the revisions made on 20 July 2016.

29 On 19 August 2016, Middleton J, as President of the Tribunal, made a number of Directions in this matter. Direction 2 required the ERA to communicate to all third parties who had made submissions in relation to the determinations the subject of the present Review Application advising them of certain matters by 23 August 2016, with an invitation to recipients (or any of their respective members) to:

(e) indicate to the Tribunal that they wish to receive and/or comment on the proposal regarding Tribunal consultations referred to in paragraphs 12 and 13 below of these directions; and

(f) express an interest in being notified of and/or participating in the Tribunal consultations in this review in the event that they do not intervene in the Tribunal review,

by Monday 5 September 2016.

30 Directions 12 and 13 made by Middleton J on 19 August 2016 concerned the community consultation process and directed the parties to take a number of steps to assist the Tribunal in relation to community consultation.

31 On 23 August 2018, the ERA sent a letter to those parties to whom Direction 2 made on 19 August 2017 had been directed. That letter included notice that intervening parties were required to notify their intention to intervene and file applications for leave to intervene by 15 September 2016. That letter also included an invitation for interested parties to indicate, by 5 September 2016, whether they wished to receive notice of and/or comment on proposals regarding the Tribunal’s public consultations and whether they were interested in being notified of and/or participating in the Tribunal’s public consultation process in the event that they did not intervene in the Tribunal review.

32 The ERA’s letter was sent to the following recipients:

(a) Catherine Rousch, Manager Regulatory Compliance, Alinta Energy;

(b) Prue Weaver, Marketing Manager Petroleum, BHP Billiton;

(c) Dominic Rodwell, Manager Gas – Business Development, CITIC Pacific Mining;

(d) Stephanie McDougall, Price Review Manager, United Energy & Multinet Gas;

(e) Julie Lane, Executive Assistant to General Manager Business Development, Wesfarmers Chemicals, Energy & Fertilisers; and

(f) Cameron Leckey, Principal Associate (CLE Town Planning & Design), Perron Developments.

33 By letter dated 31 August 2016, Wesfarmers Chemicals, Energy & Fertilisers advised the Tribunal that it:

• [wished] to receive and/or comment on proposals regarding the Tribunal’s public consultations; and

• [expressed] an interest in being notified of and/or participating in the Tribunal’s public consultations in the review in the event they do not intervene in the Tribunal review.

34 By letter dated 7 September 2016, CITIC Pacific Mining advised the Tribunal that it would like to:

• receive and/or comment on the proposal regarding Tribunal consultations referred to the directions; and

• Be notified of and/or participating in the Tribunal consultations in this review in the even that CPMM do not intervene in the Tribunal review.

35 By letter dated 12 September 2016, BHP Billiton Petroleum (Australia) Pty Ltd made the following request:

Notwithstanding the indication date of Monday, 5 September 2016, BHPB requests to receive/and or comment of proposal regarding the Tribunal’s public consultations referred to above and expresses and interest in being notified or and/or participating in the Tribunal’s public consultations in this review in the event that BHPB do not intervene in the Tribunal review.

36 No other responses to the ERA’s letter were received.

37 The Tribunal then issued a formal invitation to consult in the following terms:

Re: ACT 9 of 2016: DBNGP WA Pipeline Trust and DBNGP (WA) Transmission Pty Ltd

Invitation to Consult

The Australian Competition Tribunal is inviting:

• users and prospective users of the Dampier Bunbury Natural Gas Pipeline services; and

• any user or consumer associations or user or consumer interest groups,

to consult with the Tribunal before it determines the application by the owner and operator of the pipeline to review a determination by the Economic Regulation Authority of Western Australia (the ERA) on the revenue they may earn from the operation of the pipeline from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2020. You are being sent this invitation because you fall within the class of invitees referred to above.

Date, time and place

The public consultation forum will be held on Wednesday 7 December 2016, from 10.15 am to 5.00 pm in the Amenities Room, Level 2, at the Peter Durack Commonwealth Law Courts Building, 1 Victoria Avenue, Perth, Western Australia.

RSVP

To participate in the consultations you must provide the following information to the Tribunal Registry by email at registry@competitiontribunal.gov.au by 3.00 pm AWST on Thursday 1 December 2016.

• your contact details (including name, telephone number and email address);

• the details of any association or group that you represent;

• the topics you wish to address in your submission;

• if you are or represent an association or a group, the name and role of one nominated speaker and the names and roles of other members who will be attending; and

• whether you will be participating:

o as current and prospective users of the relevant services;

o as a representative of a user or consumer association;

o as a representative of a user or consumer interest group; or

o in some other capacity and, if so, what capacity.

Written submissions prior to registration deadline

In lieu of attendance, the Tribunal will accept written submissions that are provided to the Tribunal Registry by email at registry@competitiontribunal.gov.au in accordance with section 1.4 of the enclosed protocol and by no later than 3.00 pm AWST on Thursday 1 December 2016.

Further information

Enclosed you will find a copy of the Explanatory Guide for participants in the Tribunal’s Public Consultation Forum and the Protocol for the Public Consultation. These documents will provide important information for participants in the public consultation.

The ERA’s determination may be found on its website, www.erawa.com.au, together with the material it took into account in making its determination.

The application for review and submissions in support of it may be found on the Tribunal’s website, www.competitiontribunal.gov.au together with the context of, and arrangements for, the consultations and matters that a participant may want to consider in preparing a presentation to the Tribunal.

Yours sincerely

Tim Luxton

Registrar

Australian Competition Tribunal

38 This invitation was emailed to the six individuals referred to at [32] above on 7 November 2016. On 10 November 2016, a formal invitation was issued to the following interest groups, via email:

(a) Luke Hoare, Principal Policy Advisor, Chamber of Commerce and Industry (WA);

(b) Reg Howard-Smith, Chief Executive, Chamber of Minerals and Energy of WA (Inc); and

(c) Chris Twomey, Director Social Policy, WA Council of Social Services.

39 In addition, a Notice in similar terms was posted on the Tribunal website. That Notice was publicly accessible. On 10 November 2016, Notices were published in both The West Australian and The Australian newspapers.

40 The Tribunal did not receive any registrations in response to its formal invitation to consult or in response to its public Notices by the registration deadline. Accordingly, the community consultation was cancelled by the Tribunal, as it was unnecessary in light of the above matters.

41 On or around 7 November 2016, a Notice was published on the Tribunal website in the following terms:

Community Consultation

In the matter of an application under section 245 of the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law for a review of the decision made by the Economic Regulation Authority of Western Australia to give effect to its proposed revisions to an access arrangement for the Dampier to Bunbury Natural Gas Pipeline, pursuant to rule 64 of the National Gas Rules.

DBNGP WA Pipeline Trust and DBNGP (WA) Transmission Pty Ltd (ACT 9 of 2016)

As no registrations for the Public Consultation Forum in ACT 9 of 2016 were received by the Tribunal by 3.00 pm AWST on Thursday 1 December 2016, the Public Consultation Forum has now been cancelled by the Tribunal.

The Relevant Legislative Background

42 Section 3(2) of the WA Act provides that words and expressions used in the NGL(WA) (whether or not defined in s 9(1) of the WA Act) and in the WA Act have the same respective meanings in the WA Act as they have in the NGL(WA).

43 Section 3(3) of the WA Act provides that the provisions of s 3 of that Act do not apply to the extent that the context or subject matter otherwise indicates or requires.

44 Section 6B(1) of the WA Act provides that the Interpretation Act 1984 (WA) does not apply to the NGL(WA), to regulations under Pt 3 of the WA Act or to Rules under the NGL(WA) (ie the NGR).

45 Section 7 of the WA Act provides:

7. National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law

(1) The Western Australian National Gas Access Law text —

(a) applies as a law of Western Australia; and

(b) as so applying may be referred to as the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law.

(2) In subsection (1) —

Western Australian National Gas Access Law text means the text that results from modifying the National Gas Law, as set out in the South Australian Act Schedule for the time being in force, to give effect to section 7A(3) and (4) and Schedule 1.

46 Section 9(3) provides that the Acts Interpretation Act 1915 (SA) and certain other South Australian Acts do not apply to the NGL as set out in the Schedule to the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 (SA) in its application with modifications, as a law of WA.

47 The following definitions contained in s 2 of the NGL(WA) are relevant:

access arrangement means an arrangement setting out terms and conditions about access to pipeline services provided or to be provided by means of a pipeline;

access determination means a determination of the dispute resolution body under Chapter 6 Part 3 and includes a determination varied under Part 4 of that Chapter;

applicable access arrangement means a limited access arrangement or full access arrangement that has taken effect after being approved or made by the AER under the Rules and includes an applicable access arrangement as varied—

(a) under the Rules; or

(b) by an access determination as provided by this Law or the Rules;

applicable access arrangement decision means—

(a) a full access arrangement decision; or

(b) a limited access arrangement decision;

covered pipeline means a pipeline—

(a) to which a coverage determination applies; or

(b) deemed to be a covered pipeline by operation of section 126 or 127;

covered pipeline service provider means a service provider that provides or intends to provide pipeline services by means of a covered pipeline;

designated pipeline means a pipeline classified by the Regulations, or designated in the application Act of a participating jurisdiction, as a designated pipeline;

Note—

A light regulation determination cannot be made in respect of pipeline services provided by means of a designated pipeline: see sections 109 and 111.

designated reviewable regulatory decision means an applicable access arrangement decision (other than a full access arrangement decision that does not approve a full access arrangement);

draft Rule determination means a determination of the AEMC under section 308;

ERA means the Economic Regulation Authority established by section 4 of the Economic Regulation Authority Act 2003 of Western Australia;

final Rule determination means a determination of the AEMC under section 311;

full access arrangement means an access arrangement that—

(a) provides for price or revenue regulation as required by the Rules; and

(b) deals with all other matters for which the Rules require provision to be made in an access arrangement;

full access arrangement decision means a decision of the AER under the Rules that—

(a) approves or does not approve a full access arrangement or revisions to an applicable access arrangement submitted to the AER under section 132 or the Rules; or

(b) makes a full access arrangement—

(i) in place of a full access arrangement the AER does not approve in that decision; or

(ii) because a service provider does not submit a full access arrangement in accordance with section 132 or the Rules;

(c) makes revisions to an access arrangement—

(i) in place of revisions submitted to the AER under section 132 that the AER does not approve in that decision; or

(ii) because a service provider does not submit revisions to the AER under section 132;

national gas legislation means—

(a) the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 of South Australia and Regulations in force under that Act; and

(b) the National Gas (South Australia) Law; and

(c) the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Act 2008 of Western Australia; and

(d) the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law within the meaning given in the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Act 2008 of Western Australia; and

(e) Regulations made under the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Act 2008 of Western Australia for the purposes of the National Gas Access (Western Australia) Law; and

(f) an Act of a participating jurisdiction (other than South Australia or Western Australia) that applies, as a law of that jurisdiction, any part of—

(i) the Regulations referred to in paragraph (a); or

(ii) the National Gas Law set out in the Schedule to the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 of South Australia; and

(g) the National Gas Law set out in the Schedule to the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 of South Australia as applied as a law of a participating jurisdiction (other than South Australia or Western Australia); and

(h) the Regulations referred to in paragraph (a) as applied as a law of a participating jurisdiction (other than South Australia or Western Australia);

national gas objective means the objective set out in section 23;

National Gas Rules or Rules means—

(a) the initial National Gas Rules; and

(b) Rules made by the AEMC under this Law, including Rules that amend or revoke—

(i) the initial National Gas Rules; or

(ii) Rules made by it;

old access law means Schedule 1 to the Gas Pipelines Access (Western Australia) Act 1998 as in force from time to time before the commencement of section 30 of the National Gas Access (WA) Act 2009;

old scheme classification or determination means a classification or determination under section 10 or 11 of the old access law in force at any time before the repeal of the old access law;

old scheme distribution pipeline means a pipeline that was, at any time before the repeal of the old access law—

(a) a distribution pipeline as defined in that law; and

(b) a covered pipeline as defined in the Gas Code;

old scheme transmission pipeline means a pipeline that was, at any time before the repeal of the old access law—

(a) a transmission pipeline as defined in that law; and

(b) a covered pipeline as defined in the Gas Code;

pipeline means—

(a) a pipe or system of pipes for the haulage of natural gas, and any tanks, reservoirs, machinery or equipment directly attached to that pipe or system of pipes; or

(b) a proposed pipe or system of pipes for the haulage of natural gas, and any proposed tanks, reservoirs, machinery or equipment proposed to be directly attached to the proposed pipe or system of pipes; or

(c) a part of a pipe or system of pipes or proposed pipe or system of pipes referred to in paragraph (a) or (b),

but does not include—

(d) unless paragraph (e) applies, anything upstream of a prescribed exit flange on a pipeline conveying natural gas from a prescribed gas processing plant; or

(e) if a connection point upstream of an exit flange on such a pipeline is prescribed, anything upstream of that point; or

(f) a gathering system operated as part of an upstream producing operation; or

(g) any tanks, reservoirs, machinery or equipment used to remove or add components to or change natural gas (other than odourisation facilities) such as a gas processing plant; or

(h) anything downstream of a point on a pipeline from which a person takes natural gas for consumption purposes;

pipeline service means—

(a) a service provided by means of a pipeline, including—

(i) a haulage service (such as firm haulage, interruptible haulage, spot haulage and backhaul); and

(ii) a service providing for, or facilitating, the interconnection of pipelines; and

(b) a service ancillary to the provision of a service referred to in paragraph (a),

but does not include the production, sale or purchase of natural gas or processable gas;

price or revenue regulation means regulation of—

(a) the prices, charges or tariffs for pipeline services to be, or that are to be, provided; or

(b) the revenue to be, or that is to be, derived from the provision of pipeline services;

regulator has the meaning given to that term in section 9(1) of the National Gas Access (WA) Act 2009;

relevant Regulator has the same meaning as in section 2 of the old access law;

revenue and pricing principles means the principles set out in section 24;

reviewable regulatory decision has the meaning given by section 244;

scheme pipeline means—

(a) a covered pipeline; or

(b) an international pipeline to which a price regulation exemption applies;

service provider has the meaning given by section 8;

transmission pipeline means a pipeline that is classified in accordance with this Law or the Rules as a transmission pipeline and includes any extension to, or expansion of the capacity of, such a pipeline when it is a covered pipeline that, by operation of an applicable access arrangement or under this Law, is to be treated as part of the pipeline;

Note—

See also sections 18 and 19.

Tribunal means the Australian Competition Tribunal referred to in the Trade Practices Act 1974 of the Commonwealth and includes a member of the Tribunal or a Division of the Tribunal performing functions of the Tribunal;

48 Section 2A of the NGL(WA) provides:

2A. Meaning of AER modified

(1) In this Law, other than in the definition of AER in section 2, a reference to the AER is to be read as a reference to the regulator (whether the ERA or the AER) except to the extent that subsection (2) gives a different meaning.

(2) To the extent to which a reference to the AER is capable of being read as a reference to the Australian Energy Regulator established by section 44AE of the Trade Practices Act 1974 of the Commonwealth acting as the disputes resolution body, the term is to be read as having or including that meaning.

[Section 2A inserted by WA Act Sch. 1 cl. 4.]

49 In effect, for present purposes, pursuant to s 9(1) of the WA Act, the ERA is designated as the relevant regulator and references to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) in the NGL(WA) and in the NGR should be read as references to the ERA.

50 Sections 8, 9 and 10 of the NGL(WA) provide:

8. Meaning of service provider

(1) A service provider is a person who—

(a) owns, controls or operates; or

(b) intends to own, control or operate,

a pipeline or scheme pipeline, or any part of a pipeline or scheme pipeline.

Note—

A service provider must not provide pipeline services by means of a scheme pipeline unless the service provider is a legal entity of a specified kind: See section 131, and section 169 where the scheme pipeline is an international pipeline to which a price regulation exemption applies.

(2) A gas market operator that controls or operates (without at the same time owning)—

(a) a pipeline or scheme pipeline; or

(b) a part of a pipeline or scheme pipeline,

is not to be taken to be a service provider for the purposes of this Law.

9. Passive owners of scheme pipelines deemed to provide or intend to provide pipeline services

(1) This section applies to a person who owns a scheme pipeline but does not provide or intend to provide pipeline services by means of that pipeline.

(2) The person is, for the purposes of this Law, deemed to provide or intend to provide pipeline services by means of that pipeline even if the person does not, in fact, do so.

10. Things done by 1 service provider to be treated as being done by all of service provider group

(1) This section applies if—

(a) more than 1 service provider (a service provider group) carries out a controlling pipeline activity in respect of a pipeline (or a part of a pipeline); and

(b) under this Law or the Rules a service provider is required or allowed to do a thing.

(2) A service provider of the service provider group (the complying service provider) may do that thing on behalf of the other service providers of the service provider group if the complying service provider has the written permission of all of the service providers of that group to do that thing on behalf of the service provider group.

(3) Unless this Law or the Rules otherwise provide, on the doing of a thing referred to in subsection (2) by a complying service provider, the service providers of the service provider group on whose behalf the complying service provider does that thing, must, for the purposes of this Law and the Rules, each be taken to have done the thing done by the complying service provider.

(4) This section does not apply to a thing required or allowed to be done under section 131 or Chapter 4 Part 2.

(5) In this section—

controlling pipeline activity means own, control or operate.

51 Here, the owners are “service providers” within s 8 of the NGL(WA).

52 Section 20 of the NGL(WA) provides:

20. Interpretation generally

Schedule 2 to this Law applies to this Law, the Regulations and the Rules and any other statutory instrument made under this Law.

The “Regulations” referred to in s 20 are the regulations made under Pt 3 of the National Gas Access (WA) Act 2009 that apply as a law of Western Australia. As already noted, we shall refer to those Regulations as “the Regs”.

53 Schedule 2 to the NGL(WA) contains detailed rules governing the interpretation of the NGL(WA), the NGR and the Regs.

54 Chapter 1, Pt 3 and Pt 4 of the NGL(WA) provide:

Part 3 — National gas objective and principles

Division 1 — National gas objective

23. National gas objective

The objective of this Law is to promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, natural gas services for the long term interests of consumers of natural gas with respect to price, quality, safety, reliability and security of supply of natural gas.

Division 2 — Revenue and pricing principles

24. Revenue and pricing principles

(1) The revenue and pricing principles are the principles set out in subsections (2) to (7).

(2) A service provider should be provided with a reasonable opportunity to recover at least the efficient costs the service provider incurs in—

(a) providing reference services; and

(b) complying with a regulatory obligation or requirement or making a regulatory payment.

(3) A service provider should be provided with effective incentives in order to promote economic efficiency with respect to reference services the service provider provides. The economic efficiency that should be promoted includes—

(a) efficient investment in, or in connection with, a pipeline with which the service provider provides reference services; and

(b) the efficient provision of pipeline services; and

(c) the efficient use of the pipeline.

(4) Regard should be had to the capital base with respect to a pipeline adopted—

(a) in any previous—

(i) full access arrangement decision; or

(ii) decision of a relevant Regulator under section 2 of the Gas Code;

(b) in the Rules.

(5) A reference tariff should allow for a return commensurate with the regulatory and commercial risks involved in providing the reference service to which that tariff relates.

(6) Regard should be had to the economic costs and risks of the potential for under and over investment by a service provider in a pipeline with which the service provider provides pipeline services.

(7) Regard should be had to the economic costs and risks of the potential for under and over utilisation of a pipeline with which a service provider provides pipeline services.

Division 3 — MCE policy principles

25. MCE statements of policy principles

(1) Subject to this section, the MCE may issue a statement of policy principles in relation to any matters that are relevant to the exercise and performance by the AEMC of its functions and powers in—

(a) making a Rule; or

(b) conducting a review under section 83.

(2) Before issuing a statement of policy principles, the MCE must be satisfied that the statement is consistent with the national gas objective.

(3) As soon as practicable after issuing a statement of policy principles, the MCE must give a copy of the statement to the AEMC.

(4) The AEMC must publish the statement in the South Australian Government Gazette and on its website as soon as practicable after it is given a copy of the statement.

Part 4 — Operation and effect of National Gas Rules

26. National Gas Rules to have force of law

The National Gas Rules have the force of law in this jurisdiction.

55 The National Gas Objective (NGO) is the ultimate goal or objective of the national gas regulatory scheme. The revenue and pricing principles (RPP) are set out in s 24. Those principles bind the ERA in its regulatory decision-making.

56 Sections 27 and 28 describe the functions and powers of the ERA and the manner in which it must exercise those functions and powers. In the NGL(WA), those sections refer to the AER but, as we already mentioned at [49] above, by reason of the operation of s 2A of the NGL and s 9(1) of the WA Act, those provisions are applied to the ERA for the purposes of the NGL(WA).

57 Section 28(1)(a) requires the ERA, in performing or exercising an ERA economic regulatory function or power under the NGL(WA), to perform or exercise that function or power in a manner that will, or is likely to, contribute to the achievement of the NGO and, amongst other things, if there are two or more possible designated reviewable regulatory decisions that will, or are likely to, contribute to the NGO, the ERA must make the decision that it is satisfied will, or is likely to, contribute to the NGO to the greatest degree and must specify its reasons for that conclusion.

58 Under s 28(2), the ERA must take into account the RPP when making an access determination relating to a rate or charge for a pipeline service and may take into account those principles when performing or exercising any other ERA economic regulatory function or power, if the ERA considers it appropriate to do so.

59 Section 68C of the NGL(WA) requires the ERA to keep a written record of “decision related matter”. That section is in the following terms:

68C. Record of designated reviewable regulatory decisions

(1) The AER must, in making a designated reviewable regulatory decision, keep a written record of decision related matter.

(2) In this section —

decision related matter, in relation to a designated reviewable regulatory decision, means —

(a) the decision and the written record of it and any written reasons for it (including (if relevant) the reasons of the [ERA] for a decision of the [ERA] not to approve the access arrangement or proposed revisions to the applicable access arrangement (as the case may be)); and

(b) any document, proposal or information required or allowed under the Rules to be submitted as part of the process for the making of the decision; and

(c) any written submissions made to the [ERA] after the proposed access arrangement or proposed revisions to the applicable access arrangement (as the case may be) to which the decision relates were submitted to the [ERA] and before the decision was made; and

(d) any reports and materials (including (but not limited to) consultant reports, data sets, models or other documents) considered by the [ERA] in making the decision; and

(e) any draft of the decision that has been released for public consultation (including (if relevant) a draft of the reasons of the [ERA] for a decision of the [ERA] not to approve the access arrangement or proposed revisions to the applicable access arrangement (as the case may be)); and

(f) any submissions on the draft of the decision or the decision itself (including (if relevant) submissions on the draft of the reasons of the [ERA] for a decision of the [ERA] not to approve the access arrangement or proposed revisions to the applicable access arrangement (as the case may be)) considered by the[ERA]; and

(g) the transcript of any hearing (if any) conducted by the [ERA] for the purpose of making the decision.

[Section 68C inserted see SA Act No. 79 of 2013 s. 21 and WA Gazette 14 Mar 2014 p. 632.]

60 Chapter 2, Pt 2 of the NGL(WA) (s 69 to s 86) sets out the functions and powers of the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC), including its rule-making power.

61 Section 91 of the NGL(WA) provides:

Part 5—Functions and powers of Tribunal

91. Functions and powers of Tribunal under this Law

(1) The Tribunal has the functions and powers conferred on it under Chapter 8 Part 5 and any Regulations made for the purposes of that Division.

(2) The Tribunal has power to do all things necessary or convenient to be done for or in connection with the performance of its functions.

62 References in s 91 to “the Tribunal” are references to the Australian Competition Tribunal.

63 Chapter 8, Pt 5 of the NGL(WA) (s 244 to s 270), sets out the principles which govern merits review and other non-judicial review of regulator decisions.

64 An application for review of a reviewable regulatory decision must be made in accordance with the requirements of s 245 of the NGL(WA).

65 Section 246 provides:

246. Grounds for review

(1) An application under section 245(1) may be made only on 1 or more of the following grounds:

(a) the original decision maker made an error of fact in the decision maker’s findings of facts, and that error of fact was material to the making of the decision;

(b) the original decision maker made more than 1 error of fact in the decision maker’s findings of facts, and those errors of fact, in combination, were material to the making of the decision;

(c) the exercise of the original decision maker’s discretion was incorrect, having regard to all the circumstances;

(d) the original decision maker’s decision was unreasonable, having regard to all the circumstances.

(1a) An application under section 245(1) that relates to a designated reviewable regulatory decision must also specify the manner in which a determination made by the Tribunal varying the designated reviewable regulatory decision, or setting aside the designated reviewable regulatory decision and a fresh decision being made by the AER following remission of the matter to the AER by the Tribunal, on the basis of 1 or more grounds raised in the application, either separately or collectively, would, or would be likely to, result in a materially preferable designated NGO decision.

(2) It is for the applicant to establish a ground listed in subsection (1) and the matter referred to in subsection (1a).

[Section 246 amended see SA Act No. 79 of 2013 s. 23 and WA Gazette 14 Mar 2014 p. 632.]

66 Sections 248 to 251 set out the principles which the Tribunal must apply in considering whether or not to grant leave as required under s 245.

67 Section 252 provides that an application under s 245(1) does not stay the operation of an applicable access arrangement decision approving or making an applicable access arrangement (see subs (a)(i)).

68 Section 258A of the NGL(WA) specifies the matters that may and may not be raised in a review in respect of one or more designated reviewable regulatory decisions. That section provides as follows:

258A. Matters that may and may not be raised in a review (designated reviewable regulatory decisions)

(1) This section applies to a designated reviewable regulatory decision.

(2) The AER, in a review of a decision to which this section applies, may —

(a) respond to any matter raised by the applicant or an intervener; and

(b) raise any other matter that relates to —

(i) a ground for review; or

(ii) a matter raised in support of a ground for review; or

(iii) a matter relevant to the issues to be considered under section 259(4a) and (4b).

(3) In a review of a decision to which this section applies, the following provisions apply in relation to a person or body, other than the AER (and so apply at all stages of the proceedings before the Tribunal):

(a) a covered pipeline service provider that provides the pipeline services to which the decision being reviewed applies may not raise in relation to the issue of whether a ground for review exists or has been made out any matter that was not raised and maintained by the provider in submissions to the AER before the decision was made;

(b) a covered pipeline service provider whose commercial interests are materially affected by the decision being reviewed may not raise in relation to the issue of whether a ground for review exists or has been made out any matter that was not raised and maintained by the provider in submissions to the AER before the decision was made;

(c) an affected or interested person or body (other than a provider under paragraph (a) or (b)) may not raise in relation to the issue of whether a ground for review exists or has been made out any matter that was not raised by the person or body in a submission to the AER before the decision was made;

(d) subject to paragraphs (a), (b) and (c) —

(i) the applicant, or an intervener who has raised a new ground for review under section 256, may raise any matter relevant to the issues to be considered under section 259(4a) and (4b); and

(ii) any person or body, other than the applicant or an intervener who has raised a new ground for review under section 256, may not raise any matter relevant to the issues to be considered under section 259(4a) and (4b) unless it is in response to a matter raised by —

(A) the AER under subsection (2)(b)(iii); or

(B) the applicant under subparagraph (i); or

(C) an intervener under subparagraph (i).

(4) For the purposes of subsection (3)(d) —

(a) a reference to an applicant includes a reference to a person or body who has applied to the Tribunal for leave to apply for a review under this Division; and

(b) a reference to an intervener includes a reference to a person or body who has applied to the Tribunal for leave to intervene in a review under this Division.

[Section 258A inserted see SA Act No. 79 of 2013 s. 29 and WA Gazette 14 Mar 2014 p. 632.]

69 The powers of the Tribunal in respect of merits review by it of designated reviewable regulatory decisions are set out in s 259. That section is in the following terms:

259. Tribunal must make determination

(1) If, following an application, the Tribunal grants leave in accordance with section 245, the Tribunal must make a determination in respect of the application.

Note—

See section 260 for the time limit within which the Tribunal must make its determination.

(2) Subject to subsections (4) and (4a), a determination under this section may —

(a) affirm the reviewable regulatory decision; or

(b) vary the reviewable regulatory decision; or

(c) set aside the reviewable regulatory decision and remit the matter back to the original decision maker to make the decision again in accordance with any direction or recommendation of the Tribunal.

(3) For the purposes of making a determination of the kind in subsection (2)(a) or (b), the Tribunal may perform all the functions and exercise all the powers of the original decision maker under this Law or the Rules.

(4) In deciding whether to remit a matter back to the original decision maker to make the decision again, other than in a case where the decision is a designated reviewable regulatory decision, the Tribunal must have regard to the nature and relative complexities of—

(a) the reviewable regulatory decision; and

(b) the matter the subject of the review.

(4a) In a case where the decision is a designated reviewable regulatory decision, the Tribunal may only make a determination —

(a) to vary the designated reviewable regulatory decision under subsection (2)(b); or

(b) to set aside the designated reviewable regulatory decision and remit the matter back to the AER under subsection (2)(c),

if —

(c) the Tribunal is satisfied that to do so will, or is likely to, result in a decision that is materially preferable to the designated reviewable regulatory decision in making a contribution to the achievement of the national gas objective (a materially preferable designated NGO decision) (and if the Tribunal is not so satisfied the Tribunal must affirm the decision); and

(d) in the case of a determination to vary the designated reviewable regulatory decision—the Tribunal is satisfied that to do so will not require the Tribunal to undertake an assessment of such complexity that the preferable course of action would be to set aside the decision and remit the matter to the AER to make the decision again.

(4b) In connection with the operation of subsection (4a) (and without limiting any other matter that may be relevant under this Law) —

(a) the Tribunal must consider how the constituent components of the designated reviewable regulatory decision interrelate with each other and with the matters raised as a ground for review; and

(b) without limiting paragraph (a), the Tribunal must take into account the revenue and pricing principles (in the same manner in which the AER is to take into account these principles under section 28); and

(c) the Tribunal must, in assessing the extent of contribution to the achievement of the national gas objective, consider the designated reviewable regulatory decision as a whole; and (d) the following matters must not, in themselves, determine the question about whether a materially preferable designated NGO decision exists:

(i) the establishment of a ground for review under section 246(1);

(ii) consequences for, or impacts on, the average annual regulated revenue of a covered pipeline service provider;

(iii) that the amount that is specified in or derived from the designated reviewable regulatory decision exceeds the amount specified in section 249(2).

(4c) If the Tribunal makes a determination under subsection (2)(b) or (c), the Tribunal must specify in its determination —

(a) the manner in which it has taken into account the interrelationship between the constituent components of the designated reviewable regulatory decision and how they relate to the matters raised as a ground for review as contemplated by subsection (4b)(a); and

(b) in the case of a determination to vary the designated reviewable regulatory decision—the reasons why it is proceeding to make the variation in view of the requirements of subsection (4a)(d).

(5) A determination by the Tribunal affirming, varying or setting aside the reviewable regulatory decision is, for the purposes of this Law (other than this Part), to be taken to be a decision of the original decision maker.

[Section 259 amended see SA Act No. 79 of 2013 s. 30 and WA Gazette 14 Mar 2014 p. 632.]

70 Section 261 of the NGL(WA) specifies the matters that are to be considered by the Tribunal in making its determination. That section is in the following terms:

261. Matters to be considered by Tribunal in making determination

(1) Subject to this section, the Tribunal, in acting under this Division in relation to a reviewable regulatory decision —

(a) must not consider any matter other than review related matter (and any matter arising as a result of consultation under paragraph (b)); and

(b) must, before making a determination that relates to a designated reviewable regulatory decision, take reasonable steps to consult with (in such manner as the Tribunal thinks appropriate) —

(i) users and prospective users of the pipeline services; and

(ii) any user or consumer associations or user or consumer interest groups,

that the Tribunal considers have an interest in the determination, other than a user or consumer association or a user or consumer interest group that is a party to the review.

(1) Subject to this section, the Tribunal, in reviewing a reviewable regulatory decision, must not consider any matter other than review related matter.

[(2) deleted]

(3) If in a review, other than a review that relates to a designated reviewable regulatory decision, the Tribunal is of the view that a ground of review has been made out, the Tribunal may allow new information or material to be submitted if the new information or material—

(a) would assist it on any aspect of the determination to be made; and

(b) was not unreasonably withheld from—

(i) in all cases, the original decision maker when the decision maker was making the reviewable regulatory decision; and

(ii) in the case of a reviewable regulatory decision that is a Ministerial coverage decision, the NCC when it was it making the NCC recommendation related to Ministerial coverage decision.

(3a) If in a review that relates to a designated reviewable regulatory decision the Tribunal is of the view that a ground for review has been made out, the Tribunal may, on application by a party to the review, allow new information or material to be submitted if the party can establish to the satisfaction of the Tribunal that the information or material —

(a) was publicly available or known to be publicly available to the AER when it was making the designated reviewable regulatory decision; or

(b) would assist the Tribunal on any aspect of the determination to be made and was not unreasonably withheld from the AER when it was making the designated reviewable regulatory decision,

and was (in the opinion of the Tribunal) information or material that the AER would reasonably have been expected to have considered when it was making the designated reviewable regulatory decision.

(3b) In addition, if in a review of a designated reviewable regulatory decision the Tribunal is of the view —

(a) that a ground for review has been made out; and

(b) that it would assist the Tribunal to obtain information or material under this subsection in order to determine whether a materially preferable designated NGO decision exists,

the Tribunal may, on its own initiative, take steps to obtain that information or material (including by seeking evidence from such persons as it thinks fit).

(3c) The action taken by a person acting in response to steps taken by the Tribunal under subsection (3b) must be limited to considering decision related matter under section 68C.

(3d) In addition, in the case of a review of a designated reviewable regulatory decision that is a decision to make a full access arrangement decision in place of an access arrangement that the AER did not approve, the Tribunal may consider the reasons of the AER for its decision not to approve the access arrangement or proposed revisions to the applicable access arrangement (as the case may be).

(4) Subject to this Law, for the purpose of subsection (3)(b) and (3a)(b), information or material not provided to the original decision maker, the NCC or the AER (as the case requires) following a request for that information or material by the original decision maker, the NCC or the AER under this Law or the Rules is to be taken to have been unreasonably withheld.

(5) Subsection (4) does not limit what may constitute an unreasonable withholding of information or material.

[(6) deleted]

(7) In this section—

review related matter means —

(a) the application for review; and

(b) a notice raising new grounds for review filed by an intervener; and

(c) the submissions made to the Tribunal by the parties to the review; and

(d) —

(i) in the case of a designated reviewable regulatory decision — decision related matter under section 68C; or

(ii) in any other case —

(A) the reviewable regulatory decision and the written record of it and any written reasons for it; and

(B) any written submissions made to the original decision maker before the reviewable regulatory decision was made or the NCC before the making of an NCC recommendation; and

(C) any reports and materials relied on by the original decision maker in making the reviewable regulatory decision or the NCC in making an NCC recommendation; and

(D) any draft of the reviewable regulatory decision or NCC recommendation; and

(E) any submissions on —

• the draft of the reviewable regulatory decision or the reviewable regulatory decision itself considered by the original decision maker; or

• the draft of an NCC recommendation or the NCC recommendation itself considered by the NCC; and

(F) the transcript of any hearing (if any) conducted by the original decision maker for the purpose of making the reviewable regulatory decision; and

(e) any other matter properly before the Tribunal in connection with the relevant proceedings.

[Section 261 amended see SA Act No. 79 of 2013 s. 31 and WA Gazette 14 Mar 2014 p. 632.]

71 In the present case, the final decision is a designated reviewable regulatory decision so that s 261(7)(d)(i) applies (not s 261(7)(d)(ii)).

72 Chapter 9, Pt 1, Div 2 stipulates the tests for rule making by the AEMC. The AEMC may only make a Rule if it is satisfied that the Rule will or is likely to contribute to the achievement of the NGO.

73 Clause 1 of Sch 2 to the NGL(WA) provides:

1. Displacement of Schedule by contrary intention

(1) The application of this Schedule to this Law, the Regulations or other statutory instrument (other than the National Gas Rules) may be displaced, wholly or partly, by a contrary intention appearing in this Law or the Regulations or that statutory instrument.

(2) The application of this Schedule to the National Gas Rules (other than clauses 7, 12, 15, 17, 19 and 20, 23 to 26 and 31 to 44, 49, 52 and 53 of this Schedule) may be displaced, wholly or partly, by a contrary intention appearing in the National Gas Rules.

74 Clause 4 of Sch 2 is in the following terms:

4. Material that is, and is not, part of Law

(1) The heading to a Chapter, Part, Division or Subdivision into which this Law is divided is part of this Law.

(2) A Schedule to this Law is part of this Law.

(3) A heading to a section or subsection of this Law does not form part of this Law.

(4) A note at the foot of a provision of this Law does not form part of this Law.

(5) An example (being an example at the foot of a provision of this Law under the heading “Example” or “Examples”) does not form part of this Law.

75 Clauses 7, 8 and 9 of Sch 2 to the WA Act are in the following terms:

7. Interpretation best achieving Law’s purpose

(1) In the interpretation of a provision of this Law, the interpretation that will best achieve the purpose or object of this Law is to be preferred to any other interpretation.

(2) Subclause (1) applies whether or not the purpose is expressly stated in this Law.

8. Use of extrinsic material in interpretation

(1) In this clause—

Law extrinsic material means relevant material not forming part of this Law, including, for example—

(a) material that is set out in the document containing the text of this Law as printed by authority of the Government Printer of South Australia; and

(b) a relevant report of a committee of the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia that was made to the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia before the provision was enacted; and

(c) an explanatory note or memorandum relating to the Bill that contained the provision, or any relevant document, that was laid before, or given to the members of, the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia by the member bringing in the Bill before the provision was enacted; and

(d) the speech made to the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia by the member in moving a motion that the Bill be read a second time; and

(e) material in the Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia or in any official record of debates in the Legislative Council or House of Assembly of South Australia; and

(f) a document that is declared by the Regulations to be a relevant document for the purposes of this clause;

ordinary meaning means the ordinary meaning conveyed by a provision having regard to its context in this Law and to the purpose of this Law;

Rule extrinsic material means—

(a) a draft Rule determination; or

(b) a final Rule determination; or

(c) any document (however described)—

(i) relied on by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination; or

(ii) adopted by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination.

(2) Subject to subclause (3), in the interpretation of a provision of this Law, consideration may be given to Law extrinsic material capable of assisting in the interpretation—

(a) if the provision is ambiguous or obscure, to provide an interpretation of it; or

(b) if the ordinary meaning of the provision leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or is unreasonable, to provide an interpretation that avoids such a result; or

(c) in any other case, to confirm the interpretation conveyed by the ordinary meaning of the provision.

(3) Subject to subclause (4), in the interpretation of a provision of the Rules, consideration may be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material capable of assisting in the interpretation—

(a) if the provision is ambiguous or obscure, to provide an interpretation of it; or

(b) if the ordinary meaning of the provision leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or is unreasonable, to provide an interpretation that avoids such a result; or

(c) in any other case, to confirm the interpretation conveyed by the ordinary meaning of the provision.

(4) In determining whether consideration should be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, and in determining the weight to be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, regard is to be had to—

(a) the desirability of a provision being interpreted as having its ordinary meaning; and

(b) the undesirability of prolonging proceedings without compensating advantage; and

(c) other relevant matters.

9. Compliance with forms

(1) If a form is prescribed or approved by or for the purpose of this Law, strict compliance with the form is not necessary and substantial compliance is sufficient.

(2) If a form prescribed or approved by or for the purpose of this Law requires—

(a) the form to be completed in a specified way; or

(b) specified information or documents to be included in, attached to or given with the form; or

(c) the form, or information or documents included in, attached to or given with the form, to be verified in a specified way,

the form is not properly completed unless the requirement is complied with.

76 Clauses 11, 12 and 13 of Sch 2 provide:

11. Provisions relating to defined terms and gender and number

(1) If this Law defines a word or expression, other parts of speech and grammatical forms of the word or expression have corresponding meanings.

(2) Definitions in or applicable to this Law apply except so far as the context or subject matter otherwise indicates or requires.

(3) In this Law, words indicating a gender include each other gender.

(4) In this Law—

(a) words in the singular include the plural; and

(b) words in the plural include the singular.

12. Meaning of may and must etc

(1) In this Law, the word “may”, or a similar word or expression, used in relation to a power indicates that the power may be exercised or not exercised, at discretion.

(2) In this Law, the word “must”, or a similar word or expression, used in relation to a power indicates that the power is required to be exercised.

(3) This clause has effect despite any rule of construction to the contrary.

13. Words and expressions used in statutory instruments

(1) Words and expressions used in a statutory instrument have the same meanings as they have, from time to time, in this Law, or relevant provisions of this Law, under or for the purposes of which the instrument is made or in force.

(2) This clause has effect in relation to an instrument except so far as the contrary intention appears in the instrument.

77 References to “the Law” or “this Law” in cll 7, 8, 9, 11, 12 and 13 are references to the NGL(WA).

78 In summary, Sch 2 to the NGL(WA) requires that, unless displaced by a contrary intention appearing in the NGL(WA) or in the NGR (as may be appropriate), the following principles are to be applied to the interpretation of the NGL(WA), the NGR and the Regs:

(a) The interpretation that will best achieve the purpose or object of the NGL(WA) is to be preferred to any other interpretation. That purpose or object need not be expressly stated in the NGL(WA) (cl 7 of Sch 2 to the NGL(WA)).

(b) The NGO is the core or fundamental objective of the NGL(WA) and, as such, is to be regarded as within the expression “the purpose or object of the [NGL(WA)]”.

(c) In the circumstances described in cl 8 of Sch 2 to the NGL(WA), resort may be had to the types of extrinsic material specified in cl 8 as an aid to the interpretation of a provision of the NGL(WA) or the NGR (as the case may be). Such resort can be had if:

(i) The relevant provision is ambiguous or obscure; or

(ii) The ordinary meaning of the provision leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or unreasonable (a result which should be avoided); or

(iii) To confirm the interpretation that is conveyed by the ordinary meaning of the provision

and the extrinsic material is capable of assisting in the interpretation. Subclause (4) of cl 8 must also be taken into account. That subclause is difficult to interpret. In our view, that subclause mandates that those charged with interpreting the NGL(WA) and the NGR must, when considering whether to have regard to extrinsic material, have regard to each of the three matters specified in subcl (4). A “relevant matter” within the meaning of cl 8(4)(c) is a matter which is to be determined by the decision maker to be relevant in an objective sense. If the decision maker does have regard to the three matters specified in subcl (4)(c), that person (or entity) must also have regard to those same three matters when determining the weight to be given to that extrinsic material.

(d) Clause 7 and cl 8 of Sch 2 do not authorise a wholesale redrafting of the relevant provisions. The quest is always to find the correct interpretation of those provisions, not to embark upon an exposition of the decision maker’s view of what the provision should mean.

(e) In the NGL(WA), the meaning of “may” and “must” is as specified in cl 12 of Sch 2 to the NGL(WA) notwithstanding any rule of construction to the contrary.

(f) Except insofar as the contrary intention appears in a particular statutory instrument, words and expressions used in a statutory instrument made under the NGL(WA) have the same meaning as they have in the relevant provisions of the NGL(WA).

(g) The interpretation statutes of South Australia and Western Australia do not apply to the NGL(WA) or to the NGR. Nor does the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). The essential governing principles for the interpretation of the NGL(WA) and the NGR are found in cll 7, 8, 11, 12 and 13 of Sch 2 to the NGL(WA). In our view, it does not assist the task of interpreting the NGL(WA) and the NGR for the Tribunal to resort to common law principles of statutory construction except (perhaps) as an aid to understanding how to interpret and apply the rules of interpretation laid down in Sch 2 to the NGL(WA).

79 Rule 3 in Pt 1 (Preliminary) contains various definitions.

80 For present purposes, the following definitions are pertinent:

allowed rate of return see rule 87(1).

allowed rate of return objective see rule 87(3).

full access arrangement proposal means an access arrangement proposal consisting of, or relating to, a full access arrangement.

interest rate means:

(a) the most recent 1 month Bank Bill Swap Reference Rate mid rate determined by the Australian Financial Markets Association, as identified by AEMO on its website; or

(b) if the above rate ceases to exist, or that rate becomes, in AEMO's reasonable opinion, inappropriate, the interest rate determined and published by AEMO on its website.

rate of return guidelines means the guidelines made under rule 87.

81 Rule 8 describes in detail the standard consultative procedure which a decision maker must undertake if required to consult under the NGL(WA).

82 Part 8 (rr 40 to 68) of the NGR deals with access arrangements.

83 Rule 40 sets out the obligations which the ERA has in circumstances where it has no discretion under a particular provision of the NGL(WA), in circumstances where it has a limited discretion under that law and in circumstances where it has a full discretion under that law.

84 Rule 41 provides:

41 Access arrangement proposal to be approved in its entirety or not at all

(1) The AER’s approval of an access arrangement proposal implies approval of every element of the proposal.

(2) It follows that, if the AER withholds its approval to any element of an access arrangement proposal, the proposal cannot be approved.

85 Rule 42 to r 44 address the requirements as to the provision of access arrangement information.

86 Rule 46 governs the procedure for a full access arrangement proposal (s 132 of the NGL(WA)).

87 Rule 48 specifies the requirements for full access arrangements.

88 Rule 62 is in the following terms:

62 Access arrangement final decision

(1) After considering the submissions made in response to the access arrangement draft decision within the time allowed in the notice, and any other matters the AER considers relevant, the AER must make an access arrangement final decision.

(2) An access arrangement final decision is a decision to approve, or to refuse to approve, an access arrangement proposal.

(3) If the access arrangement proposal has been revised since its original submission, the access arrangement final decision relates to the proposal as revised.

(4) An access arrangement final decision must include a statement of the reasons for the decision.

(5) When the AER makes an access arrangement final decision, it must:

(a) give a copy of the decision to the service provider; and

(b) publish the decision on the AERis website and make it available for inspection, during business hours, at the AER's public offices.

(6) If an access arrangement final decision approves an access arrangement proposal, the access arrangement, or the revision or variation, to which the decision relates, takes effect on a date fixed in the final decision or, if no date is so fixed, 10 business days after the date of the final decision.

Note:

In the case of an access arrangement revision proposal, this date may, but will not necessarily, be the revision commencement date fixed in the access arrangement.

(7) An access arrangement final decision must be made within 6 months of the date of receipt of the access arrangement proposal.

(8) The time limit fixed by subrule (7) cannot be extended by more than a further 2 months.

89 Part 9 (rr 69 to 99) of the NGR governs the regulation of price and revenue.

90 Rules 72 to 75 provide as follows:

72 Specific requirements for access arrangement information relevant to price and revenue regulation

(1) The access arrangement information for a full access arrangement proposal (other than an access arrangement variation proposal) must include the following:

(a) if the access arrangement period commences at the end of an earlier access arrangement period:

(i) capital expenditure (by asset class) over the earlier access arrangement period; and

(ii) operating expenditure (by category) over the earlier access arrangement period; and

(iii) usage of the pipeline over the earlier access arrangement period showing:

(A) for a distribution pipeline, minimum, maximum and average demand and, for a transmission pipeline, minimum, maximum and average demand for each receipt or delivery point; and

(B) for a distribution pipeline, customer numbers in total and by tariff class and, for a transmission pipeline, user numbers for each receipt or delivery point;

(b) how the capital base is arrived at and, if the access arrangement period commences at the end of an earlier access arrangement period, a demonstration of how the capital base increased or diminished over the previous access arrangement period;

(c) the projected capital base over the access arrangement period, including:

(i) a forecast of conforming capital expenditure for the period and the basis for the forecast; and

(ii) a forecast of depreciation for the period including a demonstration of how the forecast is derived on the basis of the proposed depreciation method;

(d) to the extent it is practicable to forecast pipeline capacity and utilisation of pipeline capacity over the access arrangement period, a forecast of pipeline capacity and utilisation of pipeline capacity over that period and the basis on which the forecast has been derived;

(e) a forecast of operating expenditure over the access arrangement period and the basis on which the forecast has been derived;

(f) the key performance indicators to be used by the service provider to support expenditure to be incurred over the access arrangement period;

(g) the proposed return on equity, return on debt and allowed rate of return, for each regulatory year of the access arrangement period, in accordance with rule 87, including any departure from the methodologies set out in the rate of return guidelines and the reasons for that departure;

(ga) the proposed formula (if any) that is to be applied in accordance with rule 87(12);

(h) the estimated cost of corporate income tax calculated in accordance with rule 87A, including the proposed value of imputation credits referred to in that rule;

(i) if an incentive mechanism operated for the previous access arrangement period—the proposed carry-over of increments for efficiency gains or decrements for efficiency losses in the previous access arrangement period and a demonstration of how allowance is to be made for any such increments or decrements;

(j) the proposed approach to the setting of tariffs including:

(i) the suggested basis of reference tariffs, including the method used to allocate costs and a demonstration of the relationship between costs and tariffs; and

(ii) a description of any pricing principles employed but not otherwise disclosed under this rule;

(k) the service provider’s rationale for any proposed reference tariff variation mechanism;

(l) the service provider's rationale for any proposed incentive mechanism;

(m) the total revenue to be derived from pipeline services for each regulatory year of the access arrangement period.

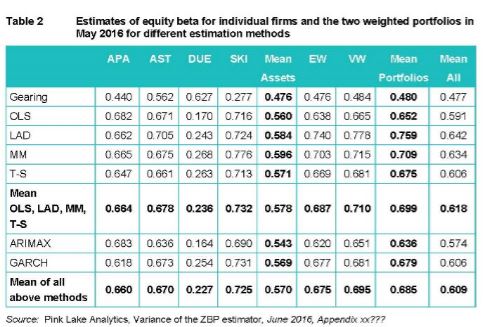

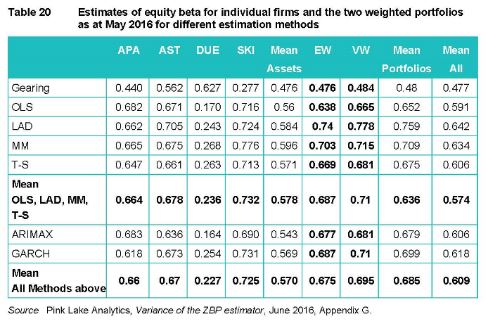

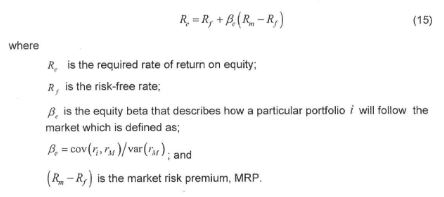

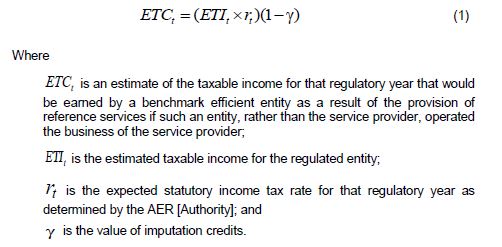

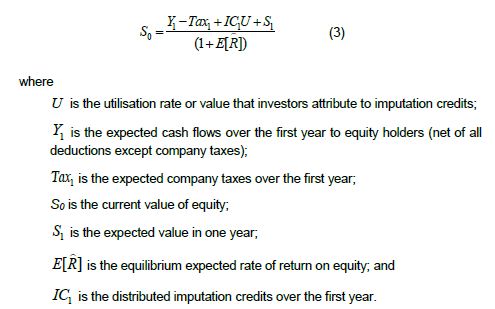

(2) The access arrangement information for an access arrangement variation proposal related to a full access arrangement must include so much of the above information as is relevant to the proposal.