AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

Application by Sea Swift Pty Limited [2016] ACompT 9

IN THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

APPLICATION FOR MERGER AUTHORISATOIN OF THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF CERTAIN ASSETS OF TOLL MARINE LOGISTICS AUSTRALIA’S MARINE FREIGHT OPERATIONS | |||

BY: | Applicant | ||

FARRELL J (DEPUTY PRESIDENT) MR R C DAVEY (MEMBER) PROFESSOR D K ROUND (MEMBER) | |

DATE OF DETERMINATION: | 1 July 2016 |

THE TRIBUNAL DETERMINES THAT:

1. Subject to the conditions in the Annexure to this determination, Sea Swift Pty Limited (ACN 010 889 040) (“Sea Swift”) is granted authorisation pursuant to ss 95AT and 95AZJ of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) to acquire:

(a) shares in:

(i) Perkins Maritime Pty Ltd (ACN 009 616 960); and

(ii) Perkins Lady Jan Pty Ltd (ACN 064 110 247); and

(b) assets from:

(i) Perkins Shipping Pty Ltd (ACN 009 597 835);

(ii) Perkins Properties Pty Ltd (ACN 009 592 885); and

(iii) Gulf Freight Services Pty Ltd (ACN 010 755 683)

as set out in a Deed of Amendment dated 17 March 2016 and the appended Amended and Restated Asset and Share Sale Agreement between the following parties:

Vendors:

Perkins Industries Pty Ltd (ACN 009 593 257)

Perkins Shipping Pty Ltd (ACN 009 597 835)

Perkins Properties Pty Ltd (ACN 009 592 885)

Gulf Freight Services Pty Ltd (ACN 010 755 683)

Vendor Guarantor:

Toll Holdings Limited (ACN 006 592 089)

Purchaser:

Sea Swift Pty Limited (ACN 010 889 040)

Purchaser Guarantor:

Sea Swift (Holdings) Pty Limited (ACN 159 387 390)

2. This determination includes the Annexure and all Schedules thereto.

ANNEXURE TO THE DETERMINATION DATED 1 JULY 2016

CONDITIONS OF THE TRIBUNAL’S AUTHORISATION

TRANSFERRED CONTRACTS CONDITION

1 Transferred Contracts Condition

(a) The authorisation is subject to the condition that Sea Swift will not give effect to, or rely on, any provision in the Transferred Contracts which requires the Customer to:

(i) exclusively use the marine freight services of Sea Swift; or

(ii) allow Sea Swift a Right of First Refusal; or

(iii) ship a minimum volume of freight with Sea Swift,

(together the Transferred Contracts Condition).

(b) For the purposes of the Transferred Contracts Condition:

(i) Transferred Contracts means the contracts listed in Schedule 2; and

(ii) Sea Swift must ensure that its obligations under the Transferred Contracts Condition are published on Sea Swift’s website and communicated to Customers within 30 days of the Completion Date.

REMOTE COMMUNITY SERVICE CONDITION

2 Remote Community Service Condition

(a) The authorisation is subject to the condition that Sea Swift will:

(i) maintain a minimum level of scheduled services to the locations and at the frequencies set out in the Remote Community Service Schedule contained in Schedule 3; and

(ii) maintain an up-to-date shipping schedule of services on its website, (together the Remote Community Service Condition).

(b) Sea Swift’s obligations under the Remote Community Service Condition are suspended to the extent that it is prevented from carrying out those obligations by an event or circumstance, or combination of events or circumstances, that are beyond the reasonable control of Sea Swift, including but not limited to:

(i) fire, lightning, explosion, flood, earthquake, storm or any other act of God or force of nature;

(ii) damage to vessel(s) or port facilities;

(iii) civil commotion, sabotage, war, revolution, radioactive contamination, or toxic or dangerous chemical contamination;

(iv) strikes, lock-outs, industrial disputes, labour disputes, industrial difficulties, labour difficulties, work bans, blockades or picketing;

(v) the impact of public holidays or necessary vessel maintenance or refit; or

(vi) any event or circumstance that prevents or jeopardises the safe operation of any scheduled service.

REMOTE COMMUNITY PRICE CONDITION

3 Remote Community Price Condition

(a) The authorisation is subject to the condition that Sea Swift will:

(i) charge no greater than the Maximum Charge for the destinations and services listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule, except as allowed by Condition 4 or in accordance with the Independent Price Review Process set out in Schedule 5;

(ii) publish on its website the Maximum Base Price for the Services, as well as the applicable rate of GST, Consignment Note Fee, Dangerous Goods Surcharge and Minimum Freight Charge, for each Financial Year,

(the Remote Community Price Condition).

(b) For the purposes of the Remote Community Price Condition:

(i) Subject to clause 3(b)(ii) below, Maximum Charge means:

(A) for Vehicle Freight Services, the Maximum Base Price multiplied by the number of units carried; and

(B) for all other Services, the Maximum Base Price multiplied by total tonnes or total cubic metres carried (whichever is greater);

(the Maximum Base Freight Charge),

plus additional charges that may include:

(C) the Fuel Surcharge Fee;

(D) applicable GST;

(E) the Consignment Note Fee;

(F) the Port, Council and Royalty Charges;

(G) the Dangerous Goods Surcharge (if applicable); and

(H) Other Charges (if applicable).

(ii) If, for a particular service, the sum of:

(A) the Maximum Base Freight Charge;

(B) the Fuel Surcharge Fee;

(C) the Consignment Note Fee;

(D) the Port, Council and Royalty Charges; and

(E) the Dangerous Goods Surcharge (if applicable);

is less than the Minimum Freight Charge, then the Maximum Charge is the total of:

(F) the Minimum Freight Charge;

(G) applicable GST; and

(H) Other Charges (if applicable).

(iii) Maximum Base Price is to be determined in accordance with the following formula:

Maximum Base Price = Base Price x (1 + CI)

where:

CI = CPI + LRI

Base Price is determined as follows:

For the Financial Year commencing 1 July 2015 the rates set out for the services listed in Schedule 4.

For each subsequent Financial Year, the Base Price is the accumulated Maximum Base Price as calculated for the previous Financial Year.

CPI is determined in accordance with the following formula:

CPI = [(CPIn – CPIb) / CPIb] x WFCPI

where:

CPIn = the quarterly Consumer Price Index: All groups, Australia for the quarter that was most recently published as at the date on which Sea Swift proposes to complete an Annual Price Review.

CPIb = the quarterly Consumer Price Index: All groups, Australia for the quarter ending June of the previous Financial Year.

WFCPI = the cost component weighting of general costs to provide the Service (31%).

And CPI is subject to a minimum of zero. CPI cannot be a negative number.

LRI is determined in accordance with the following formula:

LRI = LRIn x WFWPI

where:

LRIn = the annual labour rate percentage increases as set out in the Sea Swift Collective Agreement.

WFWPI = the cost component weighting of labour costs to provide the Service (52%).

And LRI is subject to a minimum of zero. LRI cannot be a negative number.

(iv) Consignment Note Fee is a per-consignment fee to cover the cost of documenting a consignment from receipt through to delivery. The Consignment Note Fee is as follows:

(A) for destinations listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule in the Northern Territory: $15.00 plus GST.

(B) for destinations listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule in Far North Queensland: $15.00 plus GST.

(v) Port, Council & Royalty Charges means any charges or statutory fees levied by the applicable port, government or council bodies on the cargo that is imported and exported to/from a wharf, barge ramp or any other landing site in respect of the Service being provided to the customer.

(vi) Fuel Surcharge Fee is calculated as a percentage of the Maximum Base Freight Charge for a Service. The percentage surcharge and fee are calculated (on a monthly basis) as follows:

Fuel Surcharge percentage = [(Fn – Fb) / Fb] x WFF

Fuel Surcharge Fee = Fuel Surcharge percentage x Maximum Base Freight Charge

where:

Fb = the average fuel price as at 2 February 2016 obtained from AIP Terminal Gate Pricing – Diesel – National Average (exclusive of GST and any applicable rebates).

Fn = the average fuel price on the first Business Day of the month prior to the Monthly Fuel Surcharge Review obtained from AIP Terminal Gate Pricing – Diesel - National Average (exclusive of GST and any applicable rebates).

WFF = the cost component weighting of the fuel costs to provide the Service (17%).

And the Fuel Surcharge Fee is subject to a minimum of zero. The Fuel Surcharge Fee cannot be less than zero.

(vii) Other Charges means any charges for voluntary additional services that a customer requests to be provided in conjunction with the service. These charges are notified to and accepted by the customer prior to the service being provided.

(viii) Dangerous Goods Surcharge is applied as a percentage of the Maximum Base Freight Charge for all goods that are classified as dangerous goods under the Australian Dangerous Goods Code or the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code. During the term of this Condition, the Dangerous Goods Surcharge percentage will be no higher than 25%.

(ix) Minimum Freight Charge means a specified minimum charge to consolidate and transport a single consignment of freight. The Minimum Freight Charge is as follows:

(A) for destinations listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule in the Northern Territory: $50.00.

(B) for destinations listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule in Far North Queensland: $50.00.

4 Price Reviews

(a) Sea Swift may increase the Maximum Base Price for the Services from or on 1 July each Financial Year in accordance with the formulas set out in Clause 3(b)(iii) above (Annual Price Review).

(b) Sea Swift may increase the Fuel Surcharge Fee on a monthly basis in accordance with the formula set out in Clause 3(b)(vi) above (Monthly Fuel Surcharge Review).

(c) Sea Swift may increase the applicable GST at any time but only in accordance with changes legislated by the Australian Federal Government.

(d) Sea Swift may only:

(i) increase its Base Price above the Maximum Base Price determined using the formula in Clause 3(b)(iii); or

(ii) increase the Additional Fees above the amounts set out in or determined according to Clause 3(b)(iv)-3(b)(viii);

in accordance with the Independent Price Review Process set out in Schedule 5 (Additional Proposed Price Increase).

5 Period for Which Sea Swift Must Comply With the Conditions

(a) Subject to paragraphs (b), (c) and (d) below, Sea Swift must comply with the Conditions until the earliest of:

(i) five years from the Completion Date;

(ii) a determination is made by the Tribunal that it is no longer necessary for Sea Swift to comply with the Conditions (including in circumstances where the ACCC has accepted an undertaking under section 87B of the Act in substantially the same terms as the Conditions); and

(iii) if the parties do not complete the Proposed Acquisition, when Sea Swift notifies the Tribunal of the non-completion of the Proposed Acquisition (and provides a copy of the notice to the ACCC).

(b) Sea Swift will be relieved of its obligation to comply with the Transferred Contracts Condition in respect of each of the Transferred Contracts on the date that the Current Term of that Transferred Contract expires.

(c) Subject to sub-clause 5(d) below, Sea Swift will be suspended of its obligation to comply with the Remote Community Service Condition if another operator commences operating a weekly (or more frequent than weekly) Scheduled Service, and operates that Scheduled Service for a period of 12 consecutive weeks or more:

(i) along one of the following routes, in which case the suspension applies to that route and any destination transhipped through that route:

(A) Cairns – Weipa;

(B) Cairns – Thursday Island/Horn Island;

(C) Darwin – Gove; or

(D) Darwin – Groote Eylandt,

or

(ii) to any specific destination set out in the Remote Community Service Schedule contained in Schedule 3, in which case the suspension applies in respect of that destination.

(d) If Sea Swift is suspended of its obligations to comply with the Remote Community Service Condition under sub-clause 5(c) above, because another operator commences operating a weekly (or more frequent than weekly) Scheduled Service along one of the routes listed in sub-clause 5(c)(i) or a specific destination under sub-clause 5(c)(ii), and that operator subsequently ceases to provide that Scheduled Service, Sea Swift must re-commence that Scheduled Service in accordance with the Remote Community Service Condition as soon as practicably possible, but no later than 28 days after that operator ceases to provide the Scheduled Service.

(e) Sea Swift may subcontract any or all of its obligations under the Remote Community Service Condition to another qualified supplier, but will remain responsible for satisfying the Remote Community Service Condition, subject to clause 5(c) above, at prices that comply with the Remote Community Price Condition.

SELF-COMPLIANCE REPORTING

6 Annual Reporting

Within 30 days of the end of each Financial Year comprising the Term of these Conditions, Sea Swift is to provide the ACCC with a report containing the following information:

(a) in relation to each of the Services to destinations listed in the Remote Community Service Schedule:

(i) the Base Prices that it charged for the previous Financial Year;

(ii) the Base Prices that it is charging in the current Financial Year, including details of all inputs and calculations underlying any increase to the Base Prices from the previous Financial Year that have been made in accordance with Clause 3(b)(iii);

(iii) the Fuel Surcharge Fee for each calendar month of the past Financial Year, including all underlying calculations;

(iv) the result of any Independent Price Review process during the previous Financial Year, including all documents prepared for the purpose of, or resulting from, the Independent Price Review; and

(v) details of any instances of non-compliance by Sea Swift with the Remote Community Price Condition during the relevant Financial Year, or confirmation that there has been no instance of non-compliance.

(b) the current schedule of Services and the frequency of those Services to each of the destinations set out in the Remote Community Service Schedule.

(c) details of any instances of non-compliance by Sea Swift with the Remote Community Service Condition (including failure to provide services in accordance with Schedule 3) during the relevant Financial Year.

Sea Swift must provide the ACCC with any information or documents that the ACCC reasonably requests to verify the accuracy of the report.

7 Event Reporting

Within 30 days of the occurrence of an event listed below which occurs during the Term of these Conditions, Sea Swift is to provide the ACCC with a report containing the following information:

(a) for any suspension of Sea Swift’s obligation to comply with the Remote Community Service Condition under clause 2(b):

(i) the nature and duration of these circumstances; and

(ii) the resulting changes that Sea Swift has made to its Scheduled Service schedule and the expected duration of those changes.

(b) for any suspension of Sea Swift’s obligation to comply with the Remote Community Service Condition under clause 5(c):

(i) details of the Scheduled Service route(s) and destination(s) that Sea Swift has ceased or intends to cease servicing; and

(ii) details of the other operator who has commenced operating a Scheduled Service in relation to the relevant routes(s) or destinations(s) including the frequency and continuous duration of the Scheduled Service provided by that operator.

(c) for any obligations under the Remote Community Service Condition that are subcontracted by Sea Swift to another qualified supplier under clause 5(e):

(i) the details of the Scheduled Service route(s) and destination(s) that Sea Swift has subcontracted; and

(ii) a copy of the subcontract agreement between Sea Swift and the qualified supplier.

8 Review Event

(a) If a Review Event occurs, Sea Swift may apply to the Tribunal to vary or suspend (for a period of time) one or more of the Conditions to the extent the variation or suspension is necessary to deal with the effect of the Review Event on Sea Swift.

(b) Review Event means an event or circumstance that has the result that Sea Swift:

(i) is unlikely to be able to comply with its obligations under the Conditions; or

(ii) believes that it is necessary to seek some variation due to changed circumstances (including any relevant market change, such as the loss of major contracts to competing coastal and community marine freight suppliers, or overall market contraction, or changes within the relevant regulatory environment, any of which that has a material impact on service viability).

GOVE LEASE UNDERTAKING

9 Gove Lease Undertaking

The authorisation is subject to the condition that Sea Swift:

(a) by the Completion Date has executed and given to the ACCC in respect of the Gove Lease an undertaking pursuant to section 87B of the Act in the same form as Annexure E to Sea Swift’s Application for Authorisation filed on 4 April 2016;

(b) complies with the Gove Lease Undertaking in all material respects unless and until released from it by the ACCC; and

(c) does not transfer the Gove Lease without the approval of the ACCC.

TOLL COMMITMENTS

10 Toll Commitments

The authorisation is subject to the condition that Toll:

(a) releases back to their owners two vessels it currently uses in the Northern Territory, being the Toll Territorian and the Bimah Tujuh as soon as reasonably practicable after the Completion Date;

(b) sells the Warrender as soon as reasonably practicable after the Completion Date; and

(c) does not sell the Warrender to Sea Swift, any Officer of Sea Swift, any Related Entity of Sea Swift or any Officer of such Related Entities, or any person acting under the direction or for the benefit of any of those persons or Related Entities.

11 Time limit on Proposed Acquisition

The authorisation is subject to the condition that the Proposed Acquisition is completed by 30 September 2016.

12 Defined Terms and Interpretation

A term or expression starting with a capital letter in the conditions:

(a) which is defined in the Dictionary in Schedule 1 of the Annexure (Dictionary), has the meaning given to it in the Dictionary; or

(b) which is defined in the Corporations Act, but is not defined in the Dictionary, has the meaning given to it in the Corporations Act.

SCHEDULE 1

Dictionary

Act means the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)

ACCC means the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

Additional Fees means the Fuel Surcharge Fee, the Consignment Note Fee, the Port, Council and Royalty Charges, the Dangerous Goods Surcharge and Other Charges.

Additional Proposed Price Increase has the meaning given in clause 4.

Annexure means the Annexure to the Tribunal’s determination dated 1 July 2016 including all Schedules to the Annexure.

Annual Price Review has the meaning given in clause 4.

Base Price has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(iii).

Completion Date means the date on which the Proposed Acquisition is completed.

Conditions means each of the conditions set out in this Annexure.

Consignment Note Fee has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(iv).

Customer means a counterparty to the Transferred Contracts identified in Schedule 2.

Current Term of a Transferred Contract includes any option to renew or extend the term of the Transferred Contract.

Dangerous Goods means dangerous or hazardous materials classified under the Australian Dangerous Goods Code or the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code.

Dangerous Goods Surcharge has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(viii).

Dry Freight Services means scheduled services for the transport of cargo by sea (including the transport of Dangerous Goods) which does not require a temperature controlled environment and does not include Vehicle Freight Services.

Financial Year refers to the period from 1 July to 30 June in each year.

Fuel Surcharge has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(vi).

Gove Lease means the lease between Perkins Properties Pty Ltd and the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Council in relation to the Gove Wharf at Melville Bay Rd, Foreshore Drive, Nhulunbuy, to be acquired by Sea Swift as part of the Proposed Acquisition.

Gove Lease Undertaking has the meaning given in clause 9(a).

GST means the Goods and Services Tax.

Independent Price Expert means the person appointed under Schedule 5.

Independent Price Review Process means the process set out in Schedule 5.

Maximum Base Price has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(iii).

Maximum Charge has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(i).

Minimum Freight Charge has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(ix).

Monthly Fuel Surcharge Review has the meaning given in clause 4(b).

Other Charges has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(vii).

Port, Council & Royalty Charges has the meaning given in clause 3(b)(v).

Price Increase Notice has the meaning given in clause 3(a) of Schedule 5.

Proposed Acquisition means the proposed acquisition by Sea Swift of:

(a) shares in:

(i) Perkins Maritime Pty Ltd (ACN 009 616 960); and

(ii) Perkins Lady Jan Pty Ltd (ACN 064 110 247); and

(b) assets from:

(i) Perkins Shipping Pty Ltd (ACN 009 597 835);

(ii) Perkins Properties Pty Ltd (ACN 009 592 885); and

(ii) Gulf Freight Services Pty Ltd (ACN 010 755 683)

as set out in a Deed of Amendment dated 17 March 2016 and the appended Amended and Restated Asset and Share Sale Agreement.

Refrigerated Freight Services means scheduled services for the transport of cargo by sea (including the transport of Dangerous Goods) which requires a temperature controlled environment and does not include Vehicle Freight Services.

Remote Communities Independent Price Expert means the person appointed in accordance with clause 1(a) of Schedule 5.

Remote Community Price Condition has the meaning given in clause 3.

Remote Community Service Condition has the meaning given in clause 2.

Remote Community Service Schedule means the schedule identified in Schedule 3.

Review Event has the meaning given in clause 8.

Right of First Refusal means a clause in any of the Transferred Contracts that may have the purpose or effect of requiring a Customer to allow Sea Swift to match any price proposed by a competitor.

Scheduled Service means a service by which an operator offers to the public to carry freight between two or more destinations at predetermined dates or days of the week.

Sea Swift means the entity Sea Swift Pty Ltd ACN 010 889 040.

Sea Swift Collective Agreement means the collective agreement between Sea Swift and employees of Sea Swift lodged with the Fair Work Commission in 2009 in relation to employees’ terms and conditions of employment, and includes any replacement of that agreement in the future.

Services means the scheduled general cargo services set out in Schedule 4, being:

(a) Dry Freight Services;

(b) Refrigerated Freight Services; and

(c) Vehicle Freight Services,

but excluding charter services.

Term means the period between the Completion Date and that date that is five years after the Completion Date.

TML means the entity trading as Toll Marine Logistics Australia.

Toll means Toll Holdings Limited (ACN 006 592 089)

Transferred Contracts means the contracts listed in Schedule 2.

Transferred Contracts Condition has the meaning given in clause 1.

Tribunal means the Australian Competition Tribunal.

Vehicle Freight Services means scheduled services for the transport of motor vehicles by sea, specifically meaning a domestic vehicle under 6m in length.

SCHEDULE 2

Transferred Contracts

Item | Customer |

1. | IBIS |

2. | Boral |

3. | Gemco (BHP) (Groote Eylandt) |

4. | Pacific Aluminium (Rio Tinto) (Gove) |

5. | ALPA |

6. | PUMA |

7. | Allied Pickfords Pty Ltd |

8. | Alyangula Recreation Club |

9. | Aminjarrinja Enterprises Aboriginal Corporation |

10. | Kun Huy Kag t/a Angurugu Chinese Takeaway |

11. | Anindilyakwa Land Council |

12. | B Kumar & P Kumar & P Kumar & R Kumar t/a Country Fried Chicken |

13. | The Trustee for Dugong Beach Resort t/a Dugong Beach Resort Pty Ltd |

14. | Groote Eylandt & Bickerton Island Enterprises Aboriginal Corp |

15. | Gove Unit Trust t/a Gove Motors |

16. | Gove Tackle & Outdoors |

17. | Groote Eylandt Aboriginal Trust |

18. | Ericann Pty Ltd t/a Groote Retravision & Homeware |

19. | Hasting Deering (Aust) Ltd |

20. | Scoffee Pty Ltd t/a The Coffee Shop |

21. | Three C's Café |

22. | Walkabout Lodge & Tavern |

23. | Bradley Carey t/a BC Autos |

24. | Fulton Hogan Industries Pty Ltd |

25. | Miwatj Health Aboriginal Corporation |

26. | Best Bar Pty Ltd |

27. | Outback Stores Pty Ltd |

28. | Maningrida Progress Association |

SCHEDULE 3

Remote Community Service Schedule

Location | Frequency (per week)* | |||

Dry Services | Refrigerated Services | Dangerous Goods Services | Vehicle Services | |

North Queensland (ex Cairns) | ||||

Boigu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Dauan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Mabuiag | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Saibai | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

St Pauls | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Hammond | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Coconut | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Murray | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Darnley | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Stephen Island | (1/mth tide dependant) | (1/mth tide dependant) | (1/mth tide dependant) | (1/mth tide dependant) |

Warraber | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Yam | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Yorke | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Badu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Kubin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Horn Island | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Thursday Island | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Seisia/Bamaga | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Aurukun | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) |

Lockhart River | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) |

Weipa | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Northern Territory (ex Darwin) | ||||

Milingimbi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Ramingining | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Elcho Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Numbulwar | (1/fortnight tide dependent) | (1/fortnight tide dependent) | (1/fortnight tide dependent) | (1/fortnight tide dependent) |

Umbakumba | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Bickerton Island | Fortnightly | Fortnightly | Fortnightly | Fortnightly |

Lake Evella | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Groote Eylandt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Nguiu | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Pirlangimpi | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Port Keats | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) | 1 (wet season only) |

Milikapiti | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Gove | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Paru | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Croker Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Goulburn Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Maningrida | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

* Unless otherwise specified.

SCHEDULE 4

BASE PRICES

North Queensland

Schedule of rates (excludes GST) ¹

Freight (ex-Cairns) ² | Bamaga / Seisia (NPA), Thursday Island, Horn Island, Weipa | OTSI, Lockhart, Aurukun |

Dry (m³ or tonnes) ³ | 275.54 | 413.31 |

Refrigerated (m³ or tonnes) ⁴ | 482.20 | 723.29 |

Passenger vehicles (each) ⁵ | 984.07 | 1,476.10 |

¹ Excludes Additional Fees, including the Fuel Surcharge Fee and Port & Council Charges (see further information below on Additional Fees).

² Dry and refrigerated freight will be charged either per cubic metre or per tonne, whichever measure is the greatest for a given consignment. Note that where freight is outside standard slot dimensions (20ft container size 6m x 2.4m x 1.8m) or weighing more than 20 tonnes, this schedule of rates will not apply and the Remote Community Price Condition does not apply to that service. Sea Swift will provide an individual quote to customers for such freight.

³ Sea Swift and TML adopt different terminology in categorising their respective rates. Sea Swift’s standard terminology for all dry freight is “Dry”. TML’s standard terminology for dry freight is “General Cargo”. Sea Swift’s terminology has been adopted in this Schedule.

⁴ Sea Swift’s standard terminology for temperature controlled freight is “Refrigerated”. TML’s standard terminology for temperature controlled freight is “Freezer / Chiller”. Sea Swift’s terminology has been adopted in this Schedule.

⁵ Sea Swift’s standard terminology for vehicle freight is “Passenger Vehicles”. TML’s standard terminology for vehicle freight is “Vehicles up to 5.3 mtrs”. Sea Swift’s terminology has been adopted in this Schedule. Note that the schedule of rates will not apply to vehicles over 6 metres in length and the Remote Community Price Condition does not apply to that service. Sea Swift will provide an individual quote to customers for such freight.

Northern Territory

Schedule of rates (excludes GST) ¹

Freight (ex-Darwin) ² | Dry (m³ or tonnes) ³ | Refrigerated (kg) ⁴ | Passenger vehicles (each) ⁵ |

Port Keats ⁹ | 189.55 | 1.30 | 974.84 |

Milingimbi / Ramingining | 279.74 | 1.40 | 2,008.64 |

Maningrida | 217.79 | 1.40 | 1,555.96 |

Lake Evella | 329.92 | 1.40 | 2,356.88 |

Gove | 250.00 | 1.61 | 1,000.00 |

Groote Eylandt | 369.99 | 1.62 | 1,000.00 |

Garden Pt (Pirlangimpi) | 156.07 | 1.37 | 1,114.14 |

Goulburn | 218.96 | 1.40 | 1,564.66 |

Elcho | 302.07 | 1.40 | 2,158.82 |

Snake Bay (Milikapiti) ⁸ | 132.14 | 0.83 | 649.90 |

Croker | 208.15 | 1.40 | 1,486.36 |

Nguiu ⁶ / Paru ⁷ | 119.15 | 0.75 | 541.58 |

Black Point | 208.15 | 1.44 | - |

Bickerton / Numbulwar / Umbakumba | 401.84 | 1.44 | 2,809.52 |

¹ Excludes Additional Fees, including the Fuel Surcharge Fee and Port & Council Charges (see further information below).

² Dry freight will be charged either per cubic metre or per tonne, whichever measure is the greatest for a given consignment. Refrigerated freight will be charged per kg. Note that where freight is outside standard slot dimensions (20ft container size 6m x 2.4m x 1.8m) or weighing more than 20 tonnes, this schedule of rates will not apply and the Remote Community Price Condition does not apply to that service. Sea Swift will provide an individual quote to customers for such freight.

³ Sea Swift’s standard terminology of “Dry” freight has been adopted.

⁴ Sea Swift’s standard terminology of “Refrigerated” freight has been adopted.

⁵ Sea Swift’s terminology for vehicle freight has been adopted in this Schedule. Note that the schedule of rates will not apply to vehicles over 6 metres in length and the Remote Community Price Condition does not apply to that service. Sea Swift will provide an individual quote to customers for such vehicles.

⁶ Note that TML does not currently service Nguiu. Sea Swift’s rates as at 1 August 2015 for deliveries to Nguiu have been adopted.

⁷ Note that TML does not currently service Paru. Sea Swift’s rates as at 1 August 2015 for deliveries to Paru have been adopted.

⁸ Note that TML does not currently service Snake Bay. Sea Swift’s rates as at 1 August 2015 for deliveries to Snake Bay have been adopted.

⁹ Note that TML does not currently service Port Keats. Sea Swift’s rates as at 1 August 2015 for deliveries to Port Keats have been adopted.

Additional Fees Information

Fuel Surcharge Fee | A fuel surcharge fee applies on all deliveries. The fuel surcharge fee is subject to monthly review based on movements in the national average fuel price as monitored by the Australian Institute of Petroleum. |

Consignment Note Fee | A one-off consignment fee applies on all deliveries ($15.00). |

Port & Council Fees | Various ports and councils charge port cargo fees on the volume of cargo that is shipped through the relevant facility. Port & Council fees will be added to those consignments which attract port cargo fees (where applicable). |

Dangerous Goods Surcharge | For goods classified as dangerous goods under the Australian Dangerous Goods Code or the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code, a 25% surcharge on the Maximum Base Freight Charge will apply. |

Minimum Freight Charge | Where the total calculated rate for a consignment (including all Additional Fees other than any applicable Other Charges) is below $50.00, a minimum charge of $50.00 for those services will apply, in accordance with clause 3.2(b)(ii). |

Other Charges | Where customers request additional services from Sea Swift, including pallet wrapping or transport by road to the departure depot, Sea Swift may apply a charge for those additional services. |

SCHEDULE 5

Independent Price Review Condition Process

1 Appointment of Remote Communities Independent Price Expert

(a) Within 28 days of the Completion Date, Sea Swift must appoint a Remote Communities Independent Price Expert for, subject to paragraph 1(c) of this Schedule 5, the duration of this Condition.

(b) Remote Communities Independent Price Expert must have the qualifications and experience necessary to carry out its functions independently of Sea Swift and must not be:

(i) an employee or officer of Sea Swift or its Related Bodies Corporate or of Toll or its Related Bodies Corporate, whether current or in the past 3 years;

(ii) a professional adviser of Sea Swift or its Related Bodies Corporate or of Toll or its Related Bodies Corporate, whether current or in the past 3 years;

(iii) a person who holds a material interest in Sea Swift or its Related Bodies Corporate or of Toll or its Related Bodies Corporate;

(iv) a person who has a contractual relationship with Sea Swift or its Related Bodies Corporate or of Toll or its Related Bodies Corporate (other than the terms of appointment of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert);

(v) a customer, material supplier or material customer of Sea Swift or its Related Bodies Corporate or of Toll or its Related Bodies Corporate; or

(vi) an employee or contractor of a firm or company referred to in paragraphs 1(b)(iii) to 1(b)(v) of this Schedule 5.

(c) Sea Swift must, as soon as practicable, appoint a replacement Remote Communities Independent Price Expert who meets the requirements set out in paragraph 1(b) of this Schedule 5 in the following circumstances:

(i) if the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert resigns or otherwise stops or is unable to act as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert; or

(ii) if Sea Swift has terminated the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's terms of appointment in accordance with those terms of appointment.

(d) Where the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert is unable to act for a period of time, Sea Swift may appoint a replacement Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to act as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert for that period of time only.

(e) Within 2 Business Days of the appointment of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert under paragraph 1(a) of this Schedule 5 or replacement of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert under paragraphs 1(c) or 1(d) of this Schedule 5, Sea Swift must:

(i) forward to the ACCC a copy of the executed terms of appointment; and

(ii) publish the name and contact details of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert on Sea Swift's website.

2 Conditions relating to the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's functions

Sea Swift must:

(a) procure that the terms of appointment of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert include obligations on the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to:

(i) continue to satisfy the independence criteria in paragraph 1(b) of this Schedule 5 for the period of his or her appointment;

(ii) provide any information or documents requested by the ACCC about Sea Swift's compliance with this Independent Price Review Condition Process directly to the ACCC; and

(iii) report or otherwise inform the ACCC directly of any issues that arise in the performance of his or her functions as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert or in relation to any matter that may arise in connection with this Independent Price Review Condition Process;

(b) comply with and enforce the terms of appointment for the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert;

(c) maintain and fund the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to carry out his or her functions;

(d) indemnify the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert for any expenses, loss, claim or damage arising directly or indirectly from the performance by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert of his or her functions as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert except where such expenses, loss, claim or damage arises out of the gross negligence, fraud, misconduct or breach of duty by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert;

(e) not interfere with, or otherwise hinder, the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's ability to carry out his or her functions as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert;

(f) provide and pay for any external expertise, assistance or advice required by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to perform his or her functions as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert;

(g) provide to the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert any information or documents requested by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert that he or she considers necessary for carrying out his or her functions as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert or for reporting to or otherwise advising the ACCC; and

(h) ensure that the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert will provide information or documents requested by the ACCC directly to the ACCC.

3 Raising an Additional Proposed Price Increase

(a) Sea Swift may seek an Additional Proposed Price Increase by providing written notice to the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert (Price Increase Notice).

(b) A Price Increase Notice must detail:

(i) the specific Service and location (within the Northern Territory or Far North Queensland) to which the Additional Proposed Price Increase relates;

(ii) the specific amount of the Additional Proposed Price Increase; and

(iii) Sea Swift’s reasons for the Additional Proposed Price Increase. By submitting a Price Increase Notice, Sea Swift agrees to comply with this Independent Price Review Condition Process.

(c) Sea Swift may at any time withdraw a Price Increase Notice by written notice to the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert, in which case the powers and authority of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to make a determination of that Price Increase Notice under paragraph 4 of this Schedule 5 shall forthwith cease.

4 Remote Communities Independent Price Expert Determination

(a) Where the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert has received a Price Increase Notice in relation to an Additional Proposed Price Increase, the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert must:

(i) determine whether Sea Swift’s proposed price increase is reasonable and appropriate having regard to the principles listed in paragraph 5 below; and

(ii) decide whether to accept, reject or vary Sea Swift’s proposed price increase.

(b) The Remote Communities Independent Price Expert will make his or her determination within:

(i) 30 days of the receipt of the Price Increase Notice from the Sea Swift; or

(ii) such further period as necessary for the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert to consider information requested under paragraph 4(c) of this Schedule 5, as the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert reasonably requires.

(c) Sea Swift must provide the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert with any information he or she requires to make a determination under this paragraph 4 of this Schedule 5 within a timeframe reasonably determined by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert.

(d) In the event that more than one Price Increase Notice is received in relation to a proposed new Additional Proposed Price Increase for a particular Service, the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert will only make a single determination about that Additional Proposed Price Increase.

(e) The Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's determination is final and binding on Sea Swift.

(f) When making a determination under this paragraph 4 of this Schedule 5, the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert is acting as an expert and not as an arbitrator.

5 Relevant considerations

In determining whether an Additional Proposed Price Increase is reasonable and appropriate, the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert will have regard to the following principles:

(a) that the Additional Proposed Price Increase should be set taking into account:

(i) all efficient input costs;

(ii) an appropriate allocation of Sea Swift’s relevant overhead costs;

(iii) expected volumes over the period Sea Swift has used to calculate the proposed price increase;

(iv) whether the “weighting factors” (WFCPI, WFWPI and WFF) referred to in the calculation of Maximum Base Price continue to accurately reflect the cost component weighting of general costs, labour and fuel;

(v) a rate of return that utilises a weighted average cost of capital which would be required by a benchmark efficient entity providing services with a similar degree of risk as that which applies to Sea Swift; and

(vi) the long term interests of customers of the Service.

6 Notice and Publication of Determination

(a) The Remote Communities Independent Price Expert must notify Sea Swift of the determination within seven days of making a determination.

(b) Within 30 days of receiving the determination:

(i) Sea Swift must notify its affected customers of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's determination by writing to or emailing customers, or publishing the information about the determination on its website;

(ii) if a retrospective adjustment is necessary to comply with the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert’s determination, Sea Swift must refund the relevant adjustment amount to the relevant customer(s).

(c) Whatever the outcome, the cost of the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert's determination will be borne by Sea Swift.

7 Date price increase takes effect

If the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert makes a determination under paragraph 4, then the new price increase as determined by the Remote Communities Independent Price Expert takes effect on the date that Sea Swift is notified under paragraph 6(a) of Schedule 5.

8 Sea Swift must notify the ACCC

Sea Swift must notify the ACCC at the time it initiates an Independent Price Review Process and must notify the ACCC of the results of each review, in each case within 5 business days of the relevant event occurring

THE TRIBUNAL:

1 Unless otherwise indicated, all references to legislation are references to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

2 On 4 April 2016, Sea Swift Pty Limited (“Sea Swift”) filed a Form S with the Australian Competition Tribunal (“the Tribunal”)(“Application”). Sea Swift thereby applied under s 95AU for the grant of an authorisation under s 95AT(1) in relation to its proposed acquisition of shares in two companies and most of the assets associated with the general marine freight business of Toll Marine Logistics (“TML”) in Far North Queensland (“FNQ”) and the Northern Territory (“NT”) from subsidiaries of Toll Holdings Limited (“Toll”) (“Proposed Acquisition”). Annexure A to the Application set out conditions (“Proposed Conditions”) on the basis of which the Tribunal might grant authorisation. Sea Swift also indicated that, if required by the Tribunal, it was prepared to give an undertaking to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (“ACCC”) pursuant to s 87B relating to arrangements for accessing the wharf facility at Gove that was to be acquired from TML as part of the Proposed Acquisition (“Gove Lease Undertaking”); the proposed form of the undertaking was set out in Annexure E to the Application. The Application also set out commitments that Toll was willing to make if the Tribunal were to grant authorisation (“Toll Commitments”).

3 Toll was given leave to intervene in the proceedings on an unrestricted basis. While Toll was an intervener in these proceedings, both Sea Swift and Toll sought approval of the Proposed Acquisition.

4 The Maritime Union of Australia (“MUA”) was given leave to intervene on the basis that its intervention would be limited to making submissions, adducing evidence and cross-examining other witnesses on the topic of any detriment to the public by reason of any risk to the employment or prospective employment of its members by Sea Swift or Toll in the NT or FNQ in relation to the Proposed Acquisition.

Determination

5 On 1 July 2016, the Tribunal announced that it had determined to authorise the Proposed Acquisition subject to the conditions set out in the determination (“Determination”). Shortly before making the determination, the Tribunal circulated to the ACCC, Sea Swift and Toll a draft of the Determination containing conditions which it intended to impose and invited submissions in relation to them. Changes to the Proposed Conditions required by the Tribunal, including conditions relating to the provision of the Gove Lease Undertaking and the Toll Commitments are mentioned below.

6 It is a condition of the Determination that the Proposed Acquisition be completed by 30 September 2016.

7 These are the Tribunal’s reasons for making the Determination.

Confidentiality Regime

8 On 15 April 2016 Justice Middleton (now the President of the Tribunal) issued a set of directions for the use and management of confidential information provided to the Tribunal in respect of the proceedings (“Confidentiality Regime”). “Confidential Information” was defined as “all information filed with the Tribunal in these proceedings in respect of which a claim of confidentiality has been made and not refused by the Tribunal, including the Sea Swift Pricing Information”. External legal advisers, consultants and independent experts retained by Sea Swift, Toll, and the ACCC (and their support staff) received unrestricted access to Confidential Information provided that the names of those persons had been notified to Sea Swift, the ACCC, any intervener and the Tribunal. The ACCC and its staff as well as the Tribunal and staff of the Tribunal and Federal Court of Australia assisting the Tribunal were also given access to Confidential Information as necessary. Mr Scruby, counsel for the MUA and Mr Nathan Keats, the MUA’s legal representative, were given access to some Confidential Information on the same basis.

9 Information which remains subject to the Confidentiality Regime has been redacted. Prior to publication, the Tribunal circulated a final draft of the reasons to the ACCC and external legal advisors to Sea Swift, Toll and the MUA to facilitate maintenance of confidentiality claims.

Introduction

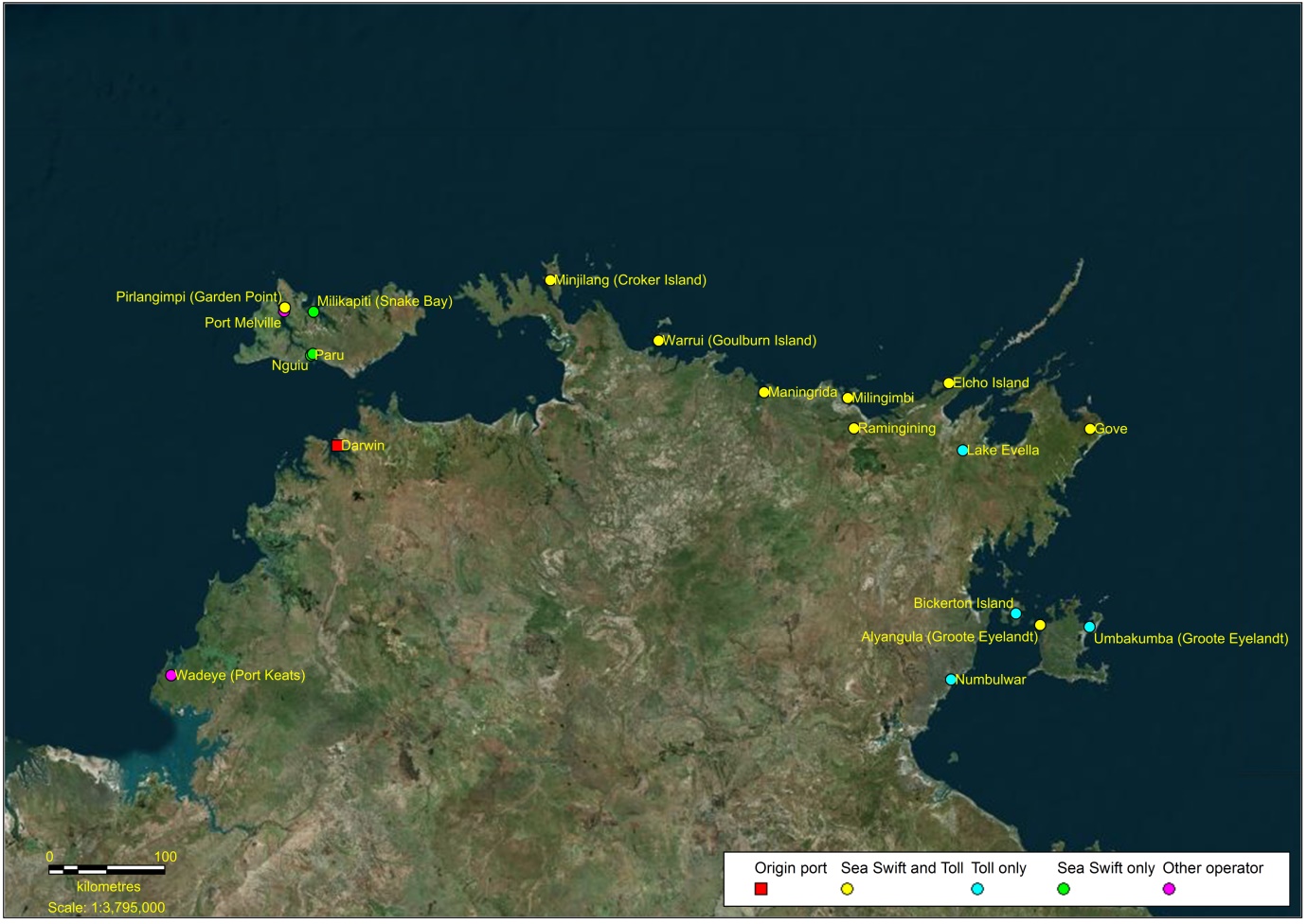

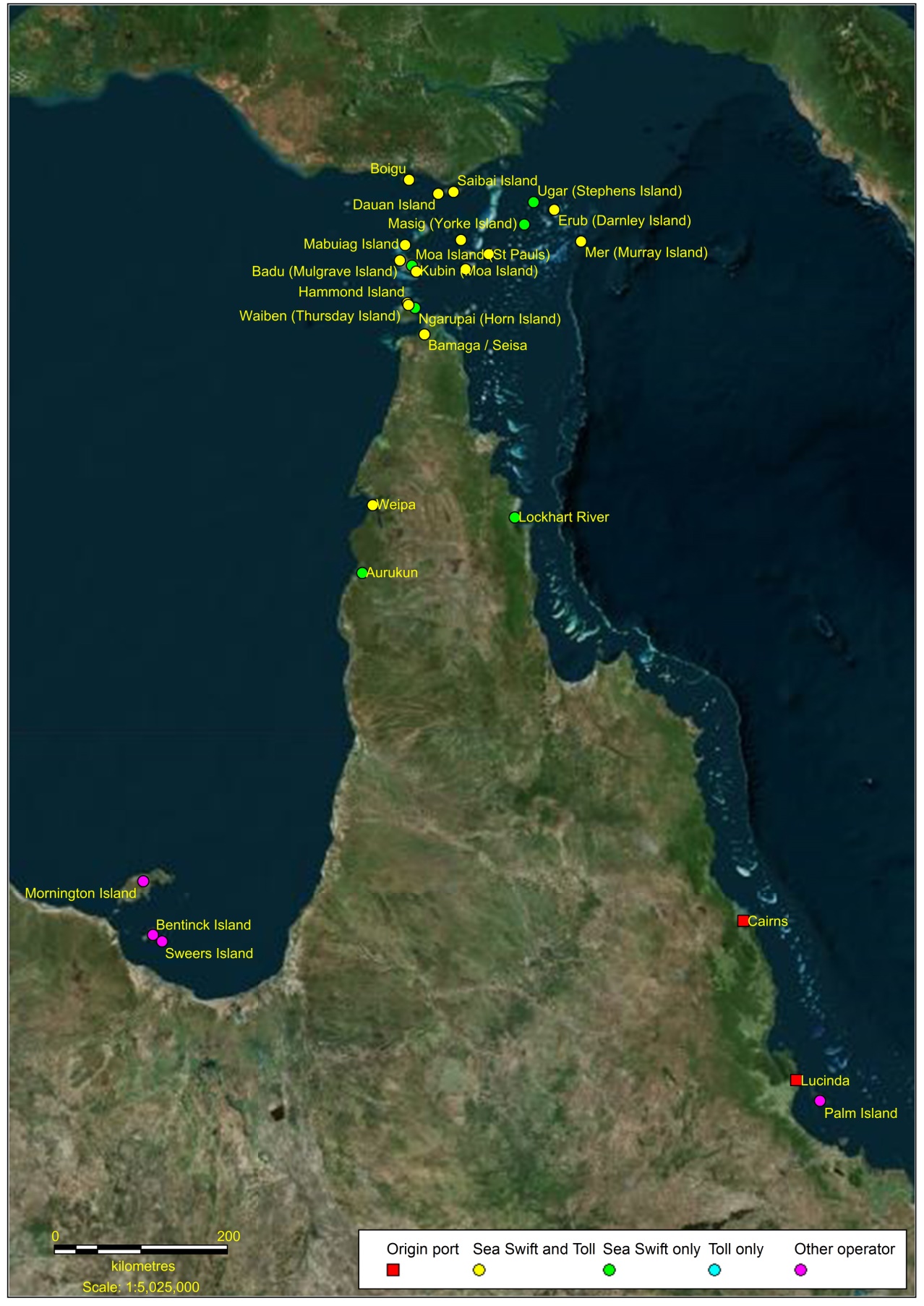

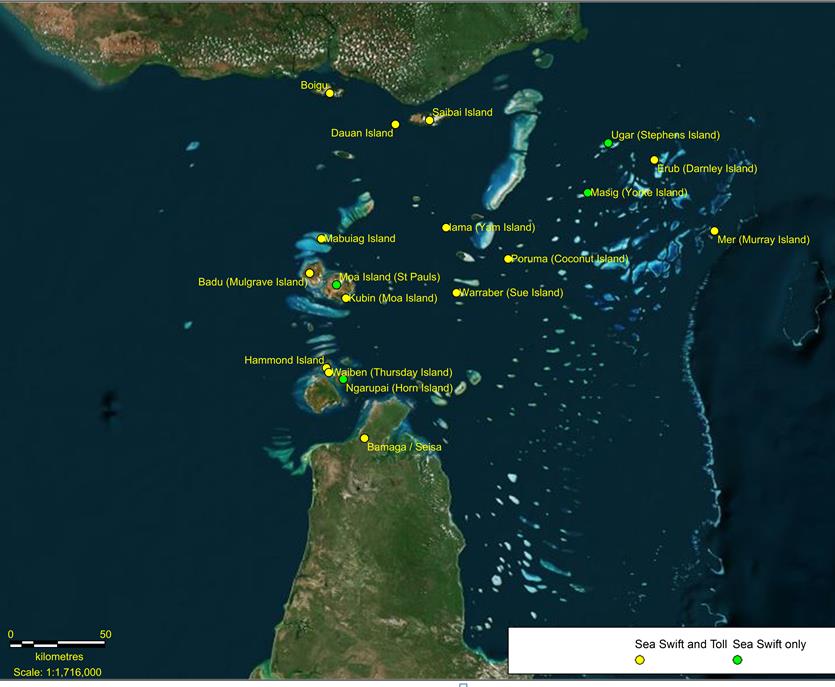

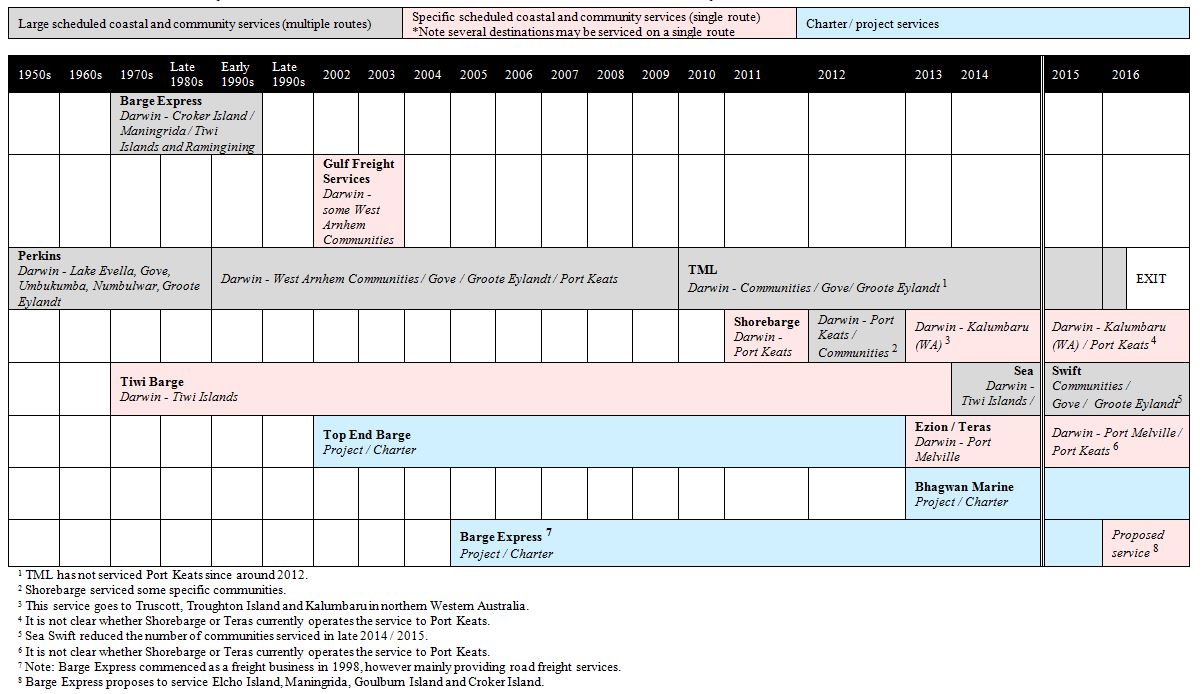

10 Both Sea Swift and TML operate “full service” marine freight businesses providing scheduled services for delivery of freight by sea to islands and remote coastal communities in FNQ (including the Outer Torres Strait Islands (“OTSI”)) and the NT. Those services will be referred to as “scheduled services”, distinct from ad hoc charter (sometimes called “project”) freight services described more fully below. Sea Swift and TML are each other’s nearest competitors in FNQ and the NT.

11 Sea Swift has provided a scheduled service to remote communities in FNQ for over 30 years; its main depot has been in Cairns since 1987. In 2009, TML was established following Toll’s acquisition of Perkins Industries Pty Ltd and its subsidiaries (“Perkins Group”). For ease of reference in these reasons, the Tribunal will refer to Perkins Group without distinction between individual companies since nothing turns on the distinction. Perkins Group had been providing shipping services predominantly in the NT, including to remote NT communities, for at least 40 years. Perkins Group’s operations in FNQ were less extensive and, since some time before 2003, they were largely limited to servicing contracts with Alcan (later Rio Tinto) and Woolworths on the Cairns-Weipa route.

Sea Swift

12 Sea Swift is a subsidiary of Sea Swift (Holdings) Pty Ltd (“Sea Swift Holdings”) which became majority owned by private equity firms CHAMP Ventures Funds (“Champ Ventures”) in November 2012. HarbourVest Partners 2007 Direct Fund LP and various individuals (including members of Sea Swift’s management) invested at the same time.

13 Sea Swift describes itself as a marine logistics company providing shipping and associated services in FNQ and the NT. The main products and services that Sea Swift supplies are:

(1) General cargo services: Sea Swift operates both charter and scheduled services for cargo including food, fuel and other goods to customers such as businesses, government agencies, mining projects and individuals on remote islands and in coastal communities;

(2) Fishery support: Sea Swift provides mothershipping services to fishing fleets, including the delivery of fuel, fresh water, packaging, consumables and exchange crew to fishing vessels and the transportation of catch back to port;

(3) Charter and project logistics: Sea Swift provides these services to resources and infrastructure customers who require large, sporadic or one-off deliveries, including the movement of construction and infrastructure materials and machinery for major projects;

(4) Passenger cruise: Sea Swift provides limited services transporting passengers and their vehicles to various locations across FNQ and the Torres Strait Islands; and

(5) Fuel retail: Sea Swift retails a small volume of fuel to regional communities at depots located in FNQ and the Torres Strait Islands.

14 Sea Swift operates the Humbug Wharf in Weipa on behalf of RTA Weipa Pty Ltd and has utilised the Gove Boat Club facility at Gove since early 2014. It operates depots at Darwin (Hudson Bay), Cairns, Weipa, Seisia/Bamaga (without a lease), Horn Island, Gove and Thursday Island.

TML

15 From 2009 until August 2014, in addition to charter and scheduled services provided to island and coastal communities in FNQ and the NT, TML ran Perkins Group’s international liner service on the Darwin-Dili-Singapore route. That international part of the service was sold as part of a planned restructure and turnaround of the performance of the TML business as a whole. TML no longer provides any international liner services into or out of Australia. It continues to provide marine logistics services to the oil and gas sector in Queensland and Western Australia. Toll became a subsidiary of Japan Post Co Ltd in May 2015.

16 To conduct its scheduled service business in the NT and FNQ, TML currently employs the following assets.

17 Vessels – TML uses two vessels in FNQ and three vessels in the NT. The two vessels in FNQ are both owned by TML: the Fourcry and the Warrender. The vessels used in the NT to provide scheduled services have changed from time to time, but currently include: the Coral Bay owned by TML, the Bimah Tujuh chartered from Barge Express and the Territorian also on charter. TML also owns the Biquele Bay which is currently used for ad hoc charter work (not scheduled services).

18 Landing facilities – TML uses various landing facilities in the NT and FNQ, all of which are common user facilities apart from its private landing facilities in Darwin and the facilities that it operates at Gove.

Toll currently has a lease over wharf facilities in Melville Bay, located on the Gove Peninsula, about 13 kilometres from the community of Nhulunbuy in the NT; it is owned by the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust (“Gove Lease”). The wharf is land based, on the lee side of Gove Harbour. The facilities include a public wharf, a “heavy lift” (“lift-on/lift-off”) wharf and a “roll-on/roll-off” landing ramp. The landing ramp is suitable for discharge of freight from barges. An aerial photograph of this facility identifying each of the wharves appears at Annexure 8 to these reasons. Access to the heavy lift wharf (but not the landing ramp) is the subject of an undertaking to the ACCC under s 87B. The undertaking was first given by Perkins Group in December 2003 after it acquired Gulf Freight Services Pty Ltd (“Gulf Freight Services”); it was modified in 2005 to allow a priority user arrangement with Alcan during the expansion of its alumina refinery at Gove; and it was continued when Toll acquired Perkins Group in 2009. TML provides stevedoring services on the heavy lift wharf and the roll-on/roll-off landing ramp.

TML’s private landing facility in Darwin at Frances Bay is on land which is partly owned and partly leased by Toll. If the Proposed Acquisition is authorised, Toll will be required to allow Sea Swift to use this facility for an interim period. The evidence of Toll’s officers is that whether or not the Proposed Acquisition was authorised, the Frances Bay facility will be closed and (subject to necessary approvals) the land will be re-zoned and sold for residential development.

TML uses other common user facilities in the NT including the Groote Eylandt Mining Company Pty Ltd (“GEMCO”) facility at Groote Eylandt and various landing ramps in the remote communities.

In FNQ, the landing facilities used by TML at Cairns, Seisia/Bamaga, Thursday Island and Horn Island are all common user facilities managed by Ports North. In Weipa, TML uses a common user facility managed by North Queensland Bulk Port Corporation.

TML has no infrastructure or equipment in the remote communities where customers typically collect their freight from the landing point (usually a beach) when the barge arrives.

19 Staff – TML employs staff across the NT and FNQ, including management and administrative staff in Darwin, terminal managers and support staff in Darwin and Cairns, material handling officers and other staff to operate depots and handle freight, and crew to operate the vessels used to provide the services (other than the Bimah Tujuh which is manned by the vessel owner, Barge Express). Based on evidence given by Mr Scott Woodward (the General Manager of Toll Energy which incorporates TML), TML employed 128 staff of whom 17 live in remote communities and are employed as depot/terminal staff. Vessel crews are subject to an enterprise bargaining agreement between Toll, the Australian Maritime Officers Union and the MUA. None of TML’s staff will be transferred to Sea Swift under the Proposed Acquisition.

20 Large contracts – There are only a limited number of contracts which provide “base load” volume for scheduled services in the NT and FNQ. The routes (and therefore remote communities served) and the frequency of the scheduled services that TML provides is typically determined by the requirements of its base load customers. Due to the nature of much of the freight (for example, fresh produce and other perishable items and fuel) and customer requirements, TML services most destinations on a weekly basis. The exceptions are that TML services some destinations in the NT on a fortnightly basis and services remote communities in OTSI on a schedule “TBA” basis, due to low levels of demand in those locations.

21 At the time of the hearing, TML’s five largest contracts which provide base load for the provision of scheduled services (“Largest Contracts”) were:

(1) GEMCO (60% owned by South 32), which has manganese mining operations on Groote Eylandt in the NT;

(2) Rio Tinto, which has mining operations in Gove in the NT and Weipa in FNQ. TML has a contract with Rio Tinto in relation to Gove (Sea Swift has the contract for Weipa). In mid-February 2016, lest authorisation not be granted to the Proposed Acquisition, Rio Tinto put the Gove and Weipa contracts out to tender; XXXX XX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXXXXXXXXX XXXXXX XXXX XXX XXX XXXX;

(3) Arnhem Land Progress Aboriginal Corporation (“ALPA”), which operates retail stores in over 25 remote locations in the NT and FNQ. TML only provides scheduled services to ALPA in the NT;

(4) Puma Energy Australia (“PUMA”), which supplies fuel to remote communities in the NT, including under contract from the Northern Territory Power & Water Corporation (“NT Power & Water”); and

(5) Islanders Board of Industry and Service (“IBIS”), which operates stores and fuel depots in 15 remote communities in FNQ. This is the only large customer contract that TML has in FNQ.

22 The customers party to the Largest Contracts will be referred to as the “Largest Customers”.

23 TML charters the Bimah Tujuh and a crew from Barge Express to provide services under the ALPA and PUMA contracts to communities at Garden Point, Maningrida, Ramingining, Milingimbi, Goulburn Island and Croker Island. It has subcontracted the performance of its services in the FNQ under the IBIS contract to Sea Swift.

24 XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXXXXXXXXX XXXXXX some have exclusivity provisions or rights of first refusal.

25 A full list of the customer contracts which TML will transfer to Sea Swift under the Proposed Acquisition is set out in Schedule 2 of the Annexure to the Determination; there are 28 in all (“Transferred Contracts”).

Competition between Sea Swift and TML

26 From 2013, there was a period of intense competition in the NT and FNQ with both Sea Swift and TML adopting a strategy of aggressive pricing in an attempt to gain market share in the territory in which the other was dominant. This resulted in reduced prices and improved service levels on some routes.

27 In January 2013, Sea Swift acquired a NT-based marine freight service provider, Tiwi Barge, and with the support of Caltex it commenced offering a full service scheduled service in competition with TML in the NT. It pursued a strategy of expanding its business in the NT by competing for TML’s contracts. In 2013, Caltex awarded a contract to Sea Swift previously held by TML in relation to the carriage of fuel in support of the contract Caltex had with NT Power & Water. TML also lost the Woolworths contract at Gove, the Rio Tinto Weipa contract and the Woolworths Weipa contract to Sea Swift, resulting in TML incurring heavy losses.

28 TML retaliated by expanding into the Torres Strait in FNQ in early 2014. TML won the IBIS contract from Sea Swift but it was not otherwise successful in winning large contracts in FNQ.

29 In October 2014, TML recovered the contract to carry fuel in the NT when PUMA won the NT Power & Water contract from Caltex.

30 As a result of aggressive competition, both TML and Sea Swift made heavy losses in the financial years 2014 and 2015. They both subsequently undertook cost-cutting measures, including abandoning or subcontracting some routes.

31 In March 2014, Toll’s senior management considered the various options for the TML business, including restructuring and cost cutting, divestment or merger and exiting the market. Mr David Jackson (CEO of Toll’s Resource and Government Logistics division, the division in which TML sits) says that he doubted that cost cutting would be effective because of TML’s underlying cost base, including enterprise bargaining agreements that resulted in a high cost of labour compared to other operators. Mr Jackson says that in taking a decision to exit the market, Toll would seek to minimise costs and disruption to TML’s customers. This was important because Toll wished to maintain its reputation with customers who were customers of the broader Toll group; it was therefore important to maintain continuity of supply and for the contracts to be performed on their current (or no less advantageous) terms. He was also aware of the social dimensions of the business conducted in the NT and FNQ.

32 On this basis, Toll made contact with CHAMP Ventures to see if there was interest in a merger between TML and Sea Swift. In August 2014, the Toll Board considered the options of winding up the business or selling to Sea Swift. Mr Jackson was authorised to pursue negotiations. In light of all of the factors and the scale of the losses incurred by TML, Mr Kruger (Toll’s Managing Director) and Mr Jackson were of the view that Sea Swift was the only realistic purchaser as only Sea Swift would be able to generate sufficient costs synergies to offset TML’s substantial operating losses. In Mr Jackson’s view, it would be a waste of time and money to seek another purchaser and Mr Kruger agreed that there was no other likely purchaser. Mr Scott Woodward also holds that view.

Timetable concerning the Proposed Acquisition

33 The Proposed Acquisition and the associated regulatory process developed as follows:

(1) On 8 September 2014, Sea Swift and Toll entered into a terms sheet in relation to a proposed transaction.

(2) On 24 November 2014, Sea Swift, Sea Swift Holdings, Toll and the relevant subsidiaries entered into an Asset and Share Sale Agreement (“Original Agreement”) relating to the shares and assets to be sold to Sea Swift. The Original Agreement contained a condition that Sea Swift obtain either formal or informal merger clearance from the ACCC or merger authorisation from the Tribunal before a sunset date of 31 May 2015.

(3) On 5 December 2014, Sea Swift and Toll sought informal merger clearance from the ACCC.

(4) By letter dated 26 February 2015, Toll advised its customers that if the transaction with Sea Swift was not approved, Toll would commence winding up TML’s operations in the NT and FNQ.

(5) The Original Agreement was varied on 26 June 2015 following renegotiation of the sunset date and to address concerns raised by the ACCC during the informal clearance process. A side deed was also executed.

(6) On 9 July 2015, the ACCC advised that it would not grant an informal clearance.

(7) On 21 September 2015, the Original Agreement (as amended) was varied and Sea Swift filed an application pursuant to s 95AU with the Tribunal seeking authorisation under s 95AT. Sea Swift withdrew that application on 16 November 2015 after it became apparent that there were issues surrounding the accuracy of its financial statements.

(8) By letter to its customers dated 21 October 2015, Toll reiterated its intention to exit the markets in the NT and FNQ and advised customers that it anticipated that if the Tribunal did not authorise Sea Swift’s acquisition of TML’s marine freight business in the NT and FNQ, it would cease providing scheduled services within approximately 60 days and wind up its operations.

(9) The Original Agreement was further varied on 17 March 2016 when a Deed of Amendment was executed. The Amended and Restated Asset and Share Sale Agreement (“ARASSA”) giving rise to the Proposed Acquisition was set out in Schedule 1 to the Deed of Amendment.

(10) A further application under s 95AU seeking authorisation under s 95AT was filed by Sea Swift on 4 April 2016.

(11) The Tribunal issued a memorandum as to the validity of the application under s 95AW on 8 April 2016.

(12) On 22 April 2016, the ACCC filed the “ACCC Issues List” in relation to the Proposed Acquisition and on 16 May 2016 it provided its Report to the Tribunal pursuant to s 95AZEA (“ACCC Report”).

34 Details of the Proposed Acquisition are summarised at [79]-[84].

Legal Principles

35 There was no contention between the parties as to the principles applicable to the Tribunal’s decision whether to grant authorisation.

36 Section 50 prohibits a corporation from acquiring shares or assets if the acquisition would have the effect, or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition in any market.

37 The Tribunal may grant authorisation to a person to acquire shares in the capital of a body corporate or acquire the assets of another person and it may do so subject to such conditions as are specified in the authorisation, including a condition that a person must make and comply with an undertaking to the ACCC under s 87B: ss 95AT(1) and 95AZJ. Section 50 does not prevent an acquisition in accordance with an authorisation, so long as the conditions of any authorisation are complied with before, during and after the acquisition: ss 95AT(2) and (3).

Test to be applied – s 95AZH

38 The Tribunal must not grant an authorisation “unless it is satisfied in all of the circumstances” that the proposed acquisition would result, or be likely to result, in “such a benefit to the public that the acquisition should be allowed to occur”: s 95AZH(1).

39 Section 95AZH(2) specifies certain matters to which the Tribunal must have regard in determining what amounts to a public benefit. None of the matters set out in s 95AZH(2) is relevant to Sea Swift’s application.

“Net public benefits” test

40 This is the second time the Tribunal has had to consider s 95AZH. However, as noted by the Tribunal in Application for Authorisation of Acquisition of Macquarie Generation by AGL Energy Limited [2014] ACompT 1 (“Mac Gen”) at [156], it has, on a number of occasions, considered the expressions “benefit to the public” and “detriment to the public” appearing in s 90 which continue to apply to the evaluation of non-merger authorisations. Section 90(9) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), which is in substantially the same terms as s 95AZH, was considered at some length in Re Qantas Airways Limited [2004] ACompT 9 (“Re Qantas”).

41 Unlike s 90, s 95AZH does not refer to detriment to the public as a factor in the Tribunal’s decision whether to authorise a proposed acquisition. Nonetheless, the Tribunal in Mac Gen found that in applying the test under s 95AZH(1), it must examine the likely anti-competitive effects of a proposed acquisition on the one hand and the likely public benefits flowing from it on the other and weigh them against each other: Mac Gen at [160]. This Tribunal adopts that position.

42 A public benefit arises from a proposed acquisition if the benefit would not exist without the acquisition or if the acquisition removes or mitigates a public detriment which would otherwise exist. If a claimed public benefit exists, in part, in a future without the proposal, the weight accorded to the benefit may be reduced appropriately. Public benefit is a wide concept and may include anything of value to the community generally so long as there is a causal link between the proposed acquisition and the benefit: see Application by Medicines Australia Inc (2007) ATPR 42-164; [2007] ACompT 4 (“Medicines Australia”) at [107], [118]-[119]. Benefits not widely shared may nevertheless be benefits to the public: Hospital Benefit Fund of Western Australia Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1997) 76 FCR 369 at 375-377. However, the extent to which the benefits extend to ultimate consumers is a matter to be put in the scales: Mac Gen at [168].

43 A public detriment includes the reduction of competition arising from an acquisition as well as other matters contrary to the goals pursued by society, including the goal of economic efficiency; public detriment may not be confined to competitive detriment: see Medicines Australia at [108] and [115]; see also Re Australian Association of Pathology Practices Incorporated (2004) 206 ALR 271; ATPR 41-985; [2004] AComptT 4 at [93]-[94]; and Re VFF Chicken Meat Growers’ Boycott Authorisation (2006) ATPR 42-120; [2006] AComptT 2 at [66]-[67].

Future “with and without”

44 In assessing relevant public detriments and public benefits associated with a proposed acquisition, the Tribunal looks to hypothetical futures, one where the acquisition takes place and is in effect and one where it does not take place, the so called “with and without” test. The test is not to compare the present situation with the future situation: it is not a “before and after” test: Medicines Australia at [117]-[119].

Degree of satisfaction required

45 The Tribunal must be satisfied that a claimed benefit or detriment is such that it will, in a tangible and commercially practical way, be a consequence of a proposed acquisition if the acquisition is allowed to occur and that the applicant is commercially likely to act in a way which brings about the benefit or detriment. The benefit or detriment must be sufficiently capable of exposition (but not necessarily quantitatively so) rather than “ephemeral or illusory”: see Re Qantas at [156].

46 For a benefit or detriment to be taken into account, it must “be of substance and have durability”. Any estimate as to their quantification should be robust and commercially realistic. The assumptions underlying the estimates should be spelled out in such a way that they can be tested and verified. Care must be taken to distinguish between one-off benefits and those of a more lasting nature. The options for achieving claimed benefits should be explored and appropriate weighting given to future benefits not achievable in any other less anti-competitive way. The Tribunal must be satisfied that “there is a real chance, and not a mere possibility” of the benefit or detriment eventuating. While it is not necessary to show that the benefits or detriments are certain to occur, or that it is more probable than not that they will occur, claims that are purely speculative in nature should not be given any weight: see Mac Gen at [163]-[164] and the cases there cited.

47 The Tribunal’s decision must be based in the real world and not rest on speculation or theory alone: see Australian Gas Light Company v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 3) (2003) 137 FCR 317; [2003] FCA 1525 (“AGL v ACCC (No 3)”) per French J (as he then was) at [348]. While French J was considering the test in s 50, the parties accept that this proposition is equally applicable to the assessment which the Tribunal is required to make under s 95AZH(1).

48 In summary, the Tribunal is called upon to make a robust and commercially realistic judgment of the claimed public benefits and public detriments, exposed by its reasoning process: see Mac Gen at [172]; cf Re Qantas at [206]-[210].

Does s 95AZH(3) bar the grant of an authorisation?

49 An authorisation cannot be granted for an acquisition that has occurred: s 95AZH(3).

50 For completeness, the Tribunal mentions that shortly before the “readiness” case management conference held on 3 June 2016, it was drawn to the Tribunal’s attention that Sea Swift’s Application had been made on 4 April 2016, more than 14 days after the ARASSA was adopted by Sea Swift and Toll when they entered into the Deed of Amendment on 17 March 2016. This was relevant because of the combined effect of s 50(4) and s 4(4). While the Tribunal was satisfied that it had jurisdiction to hear the application which had been validly made, it sought submissions as to whether it was in a position to grant an authorisation if it was satisfied that the Proposed Acquisition resulted (or would be likely to result) in “such a benefit to the public that the acquisition should be allowed to occur”: see s 95AZH(1).

51 Section 50(4) provides:

Where:

(a) a person has entered into a contract to acquire shares in the capital of a body corporate or assets of a person;

(b) the contract is subject to a condition that the provisions of the contract relating to the acquisition will not come into force unless and until the person has been granted a clearance or an authorization to acquire the shares or assets; and

(c) the person applied for the grant of such a clearance or an authorization before the expiration of 14 days after the contract was entered into;

the acquisition of the shares or assets shall not be regarded for the purposes of this Act as having taken place in pursuance of the contract before:

(d) the application for the clearance or authorization is disposed of; or

(e) the contract ceases to be subject to the condition;

whichever first happens.

[Emphasis added]

52 Section 4(4):

In this Act:

(a) a reference to the acquisition of shares in the capital of a body corporate shall be construed as a reference to an acquisition, whether alone or jointly with another person, of any legal or equitable interest in such shares; and

(b) a reference to the acquisition of assets of a person shall be construed as a reference to an acquisition, whether alone or jointly with another person, of any legal or equitable interest in such assets but does not include a reference to an acquisition by way of charge only or an acquisition in the ordinary course of business.

[Emphasis added]

53 At the case management conference on 3 June 2016, Mr Burnside QC referred the Tribunal to AGL v ACCC (No 3) at [338]-[339] in which these provisions were considered by French J:

… Acquisitions of shares are defined by what amounts to a deeming provision in s 4(4)(a) of the Act. A reference to such an acquisition ‘shall be construed as a reference to an acquisition, whether alone or jointly with another person, of any legal or equitable interest in such shares’. On that definition, one transaction may give rise to successive acquisitions for the purposes of s 50. A corporation which enters into a contract to purchase the shares of a body corporate may acquire an equitable interest prior to settlement and thereby acquire the shares pursuant to s 4(4). This will not necessarily attract the prohibition in s 50. Where the acquisition of the legal interest has not been completed and no right subsists in the acquirer as a shareholder in the target body corporate then forging any link to a substantial lessening of competition would be problematic.

In the case of a contract subject to a condition precedent, as in the present case, no interest is conveyed until satisfaction of the condition. Broken Hill Pty Co Ltd v Trade Practices Tribunal (1980) 47 FLR 384; (1980) 31 ALR 401 concerned an acquisition of shares conditional upon authorisation by the Trade Practices Commission. It conveyed no direct beneficial interest in the shares. A direct beneficial interest was acquired only when the contract became specifically enforceable by an order to convey or transfer. Prior to the condition being satisfied, the purchaser could seek an order to require the vendor to do what it must under the contract to secure fulfilment of the condition…

54 Clause 2 of the ARASSA states that the contract is conditional on the Tribunal authorising the Proposed Acquisition. Sea Swift and Toll submitted that Sea Swift’s only entitlement under the ARASSA was to specific performance of any steps required to fulfil the condition; no “acquisition” occurred as a result of entry into that agreement. It was further submitted that if it were to be found that Sea Swift had acquired a legal or equitable interest in the relevant shares or assets upon entry into the Deed of Amendment, Sea Swift did not seek authorisation of that interest; it sought authorisation of the acquisition of assets and shares that would occur if and when the agreement is completed. Accordingly, Sea Swift did not seek to rely on s 50(4).

55 The ACCC did not seek to contradict those submissions. As submitted by Mr Burnside QC at the case management conference, if s 50(4) operated as a time bar it would also have profound implications for the ACCC’s informal clearance process.

56 Having regard to s 42 and relying on the reasoning and authority of AGL v ACCC (No 3) at [338]-[339], the presidential member found that s 95AZH(3) does not prevent the grant of an authorisation in this matter.

Witnesses and other evidence

Matters the Tribunal must take into account

57 Section 95AZG(2) sets out the matters that the Tribunal is required to take into account in making its determination which include:

(1) any submissions in relation to the application made to it within the period specified by the Tribunal. In addition to written and oral submissions received from Sea Swift, Toll, the ACCC and the MUA, the Tribunal received submissions from Mr Peter Ah Loy of See Hop Trading Pty Ltd trading in the Thursday Islands; Mr Mark Hedley of Weipa; the Torres Strait Island Regional Authority; the Honourable Warren Entsch MP, Federal Member for Leichhardt based in Cairns; the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (“Department of PM & C”); and the Department of the Chief Minister of the NT. One submission was received from an entity which was not prepared to allow the parties access to the submission. As the entity did not respond to a request from the Tribunal to provide the submission to the parties’ lawyers or experts under the Confidentiality Regime so that they would have an opportunity to respond to it, the Tribunal has treated that submission as withdrawn and has not considered it;

(2) any information received pursuant to a notice issued by the Tribunal under s 95AZC; a notice was issued to Sea Swift and a response received;

(3) any information received pursuant to a notice issued by the Tribunal under s 95AZD; notices were issued to, and responses received from: Toll; TML; PUMA; ALPA; Barge Express; Mr Ken Conlon, the Managing Director of Barge Express; and Mr Stephen Muller, the Chief Executive Officer of MIPEC Pty Ltd (“MIPEC”);

(4) any information obtained from consultations under s 95AZD(2);

(5) any report by the ACCC given to the Tribunal under s 95AZEA. The Tribunal received the ACCC’s Report on 16 May 2016; and