FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mussalli v Commissioner of Taxation [2020] FCA 544

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (CTH) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 April 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the respondent as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2065 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | RONALD MUSSALLI Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (CTH) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 April 2020 |

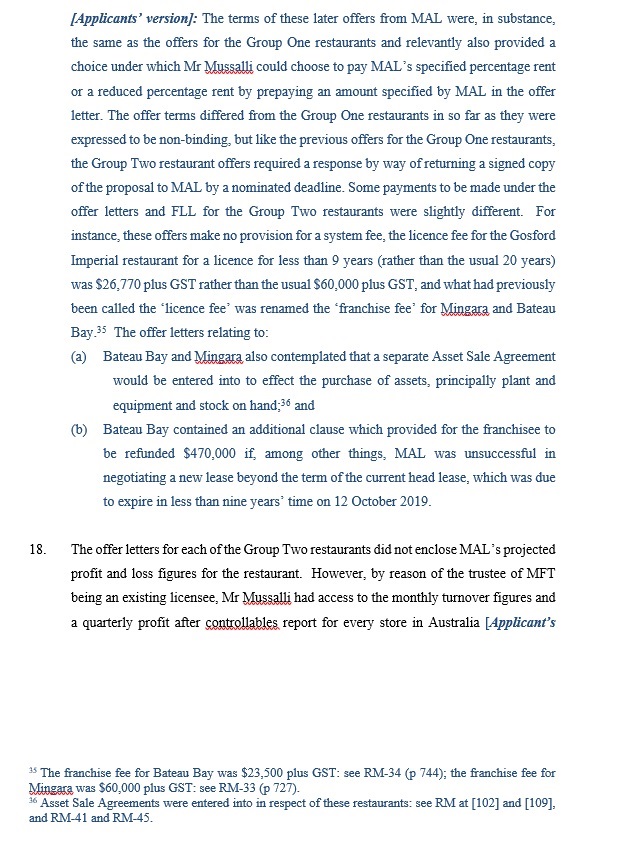

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the respondent as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2066 of 2018 | ||

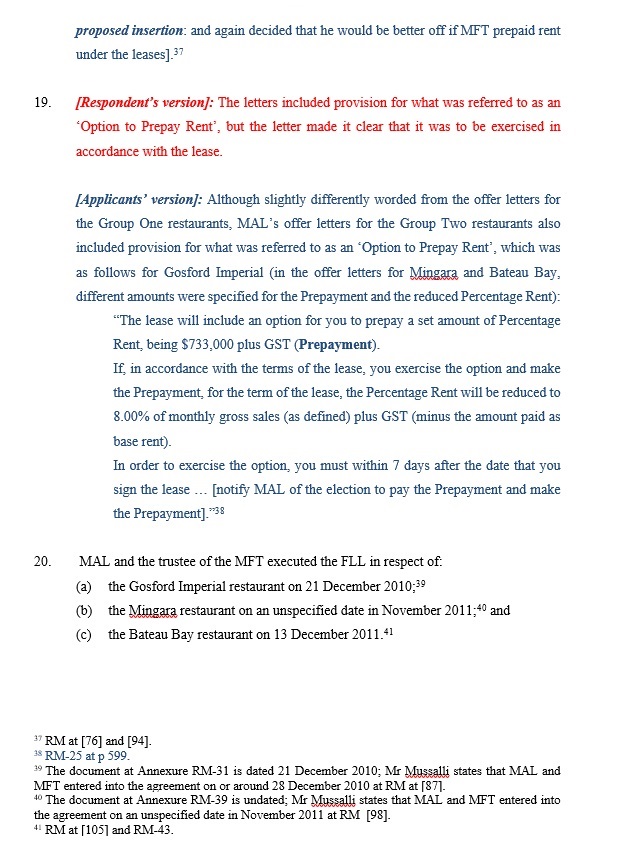

BETWEEN: | SARONCORP PTY LTD Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (CTH) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 April 2020 |

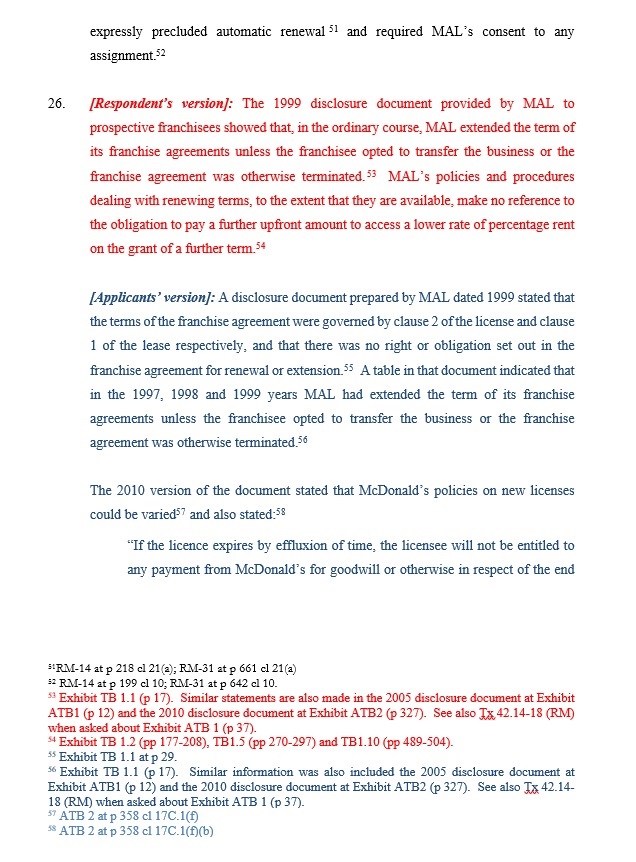

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the respondent as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2067 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | SANDRA MUSSALLI Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (CTH) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 April 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the respondent as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2068 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | DANIEL MUSSALLI Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (CTH) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 April 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the costs of the respondent as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

The proceedings

1 These reasons for judgment relate to five appeals against appealable objection decisions under s 14ZZ of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (the TAA).

2 Deductions were claimed on behalf of the applicants for payments identified as “prepaid rent” in accordance with s 82KZMD of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (the ITAA 1936). Following an audit, the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) denied all of the deductions that had been claimed. The Commissioner then issued amended notices of assessment relating to the income years ending 30 June 2012 to 30 June 2015.

3 The applicants lodged objections against each of their respective amendments. The Commissioner disallowed the objections in full. The applicants then appealed the Commissioner’s objection decisions.

4 The issue is whether the payments identified as “prepaid rent” were outgoings of capital or of a capital nature which were not deductible under s 8-1(2) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (the ITAA 1997).

5 By s 14ZZO of the TAA the applicants have the burden of proving that the amended assessments are excessive or otherwise incorrect and what the assessment should have been.

6 I have decided that the payments were outgoings of capital or of a capital nature, with the consequence that the applicants have not discharged the burden of proving that the amended assessments are excessive. My reasons follow.

Facts

7 The primary facts were not in dispute.

8 The parties filed two statements of facts.

9 The first, Annexure 1 to these reasons, agrees the foundational facts in respect of the Mussalli Family Trust (MFT) and the Mussalli Investment Trust (MIT). It also agrees the basic facts in respect of the deductions claimed for the income years 2012 to 2015, the Commissioner’s disallowance of the deductions, the Commissioner’s issue of the notices of amended assessment of income tax, the applicants’ objections, the Commissioner’s disallowance of the objections, and the filing of the appeals in respect of the disallowed objections.

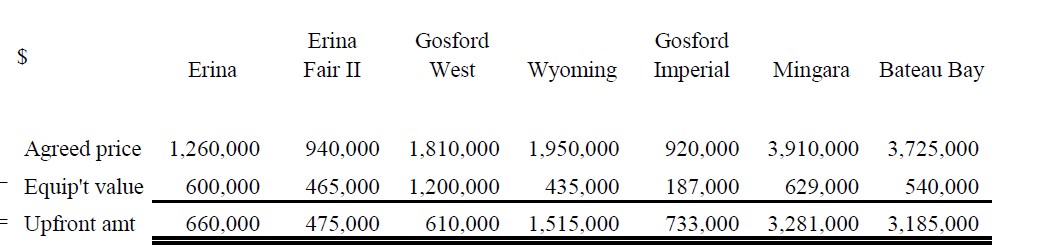

10 The second, Annexure 2 to these reasons, shows the agreed facts in black, the applicants’ asserted facts disputed by the respondent in blue, and the respondent’s asserted facts disputed by the applicants in red.

11 Many of the asserted facts which are in dispute are not determinative of the substantive issue which is whether upfront payments made, referred to as “prepaid rent”, were on capital or revenue account. Further, many of the disputed facts concern issues about the form which the assertion takes or the level of detail it contains. As a result, and subject to one exception, I consider that the applicants’ and respondent’s competing versions of the asserted facts are both correct.

12 The one exception to which I referred above is the applicants’ version of paragraph 12 of Annexure 2 which does more than assert facts. The applicants’ paragraph 12 says that Mr Ronald Mussalli (Mr Mussalli) first accepted each offer and subsequently confirmed the prepayments which reduced the percentage rent payable in each case. This involves a legal characterisation of the “Form of Acceptance” with which I do not agree. It is true that the “Form of Acceptance” contains two spaces for signature with the offer of the lease and licence being located before the confirmation of the prepayment of rent. In my view, however, the better characterisation of what Mr Mussalli did involves recognition of the fact that he accepted the offer of the lease and licence from McDonald’s Australia Limited (MAL) at the same time as he exercised the option to make a prepayment reducing the percentage rent payable.

13 In summary, MAL offered Mr Mussalli a lease and licence to operate a McDonald’s Family Restaurant on four sites, Erina, Erina Fair II, Gosford West and Wyoming (Group One restaurants). The offers included the terms of a Full Lease and Licence (FLL) which varied depending on whether MAL owned the premises (in which case the term was 20 years) or leased the premises (in which case the term was one day less than the head lease). By accepting MAL’s offer MFT agreed to a later entry into the FLL for each restaurant including a seven day cooling off period.

14 The letters of offer foreshadowed a number of required payments including, under the FLL, a base rent amount payable monthly plus GST and a percentage rent amount calculated by reference to monthly gross sales plus GST. Each of the letters of offer also included a provision to the effect set out below in respect of the Erina restaurant (with differences for each site in the percentage specified and the prepayment amount):

This agreement includes an option for you to reduce your Percentage Rent, as referred to above, to 8.25% of monthly gross sales (as defined) plus GST minus the amount paid as base rent plus GST, subject to a prepayment of rent of $660,000 plus GST on the day of handover.

15 If the option was exercised, a further payment plus GST was to be made on the day of “handover”, being the day on which the new franchisee began to operate the restaurant.

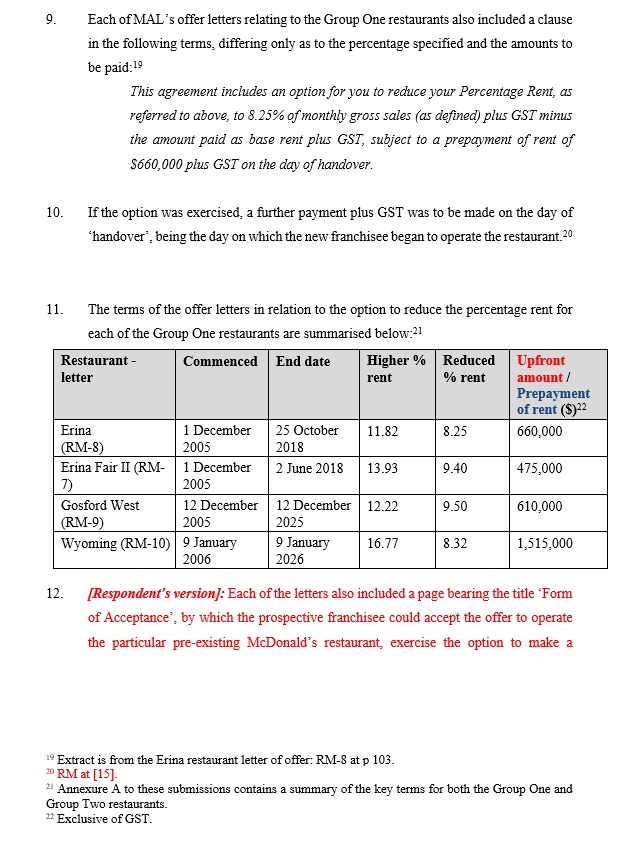

16 The terms of the offer letters in relation to the option to reduce the percentage rent for each of the Group One restaurants are summarised below:

Restaurant - letter | Commenced | End date | Higher % rent | Reduced % rent | Upfront amount / Prepayment of rent ($ excluding GST) |

Erina (RM-8) | 1 December 2005 | 25 October 2018 | 11.82 | 8.25 | 660,000 |

Erina Fair II (RM-7) | 1 December 2005 | 2 June 2018 | 13.93 | 9.40 | 475,000 |

Gosford West (RM-9) | 12 December 2005 | 12 December 2025 | 12.22 | 9.50 | 610,000 |

Wyoming (RM-10) | 9 January 2006 | 9 January 2026 | 16.77 | 8.32 | 1,515,000 |

17 It will be apparent from the last column and the references to “Upfront Amount” in red and “Prepayment of rent” in blue that the parties disagreed about the description of the payment. A discussion of the relevant principles is set out below. It is apparent that the labels the parties chose to attach to a transaction are not determinative. In all of the transaction documents the payments in issue are referred to as a prepayment of rent. That does not mean that the payments are necessarily to be characterised as rent and are thereby outgoings of revenue.

18 Mr Mussalli accepted each of the offers to operate the Group One restaurants including to pay the “prepayment of rent” so as to reduce the percentage rent payable. He did this because, in his view, he could increase the turnover beyond MAL’s projections and would be better off because the MFT would derive a higher amount of net income.

19 Each FLL was subsequently executed by MAL and the MFT in respect of the Group One restaurants. Amongst other things, the prepayment of rent was paid on handover. The leases for the sites of the Group One restaurants only referred to the reduced amount of percentage rent payable. They did not refer to the option to reduce the percentage rent.

20 Subsequently, MAL made further offers to Mr Mussalli to operate existing McDonald’s Family Restaurants at Gosford Imperial, Mingara and Bateau Bay (the Group Two restaurants).

21 MAL and the trustee of the MFT executed the FLL in respect of:

(1) the Gosford Imperial restaurant on 21 December 2010;

(2) the Mingara restaurant on an unspecified date in November 2011; and

(3) the Bateau Bay restaurant on 13 December 2011.

22 The terms of the FLLs for the Group Two restaurants were relevantly similar to the FLLs for the Group One restaurants apart from including a new clause 2.02(c) of the lease which stated as follows:

If the Lessee exercises the Prepayment Option in the manner specified in clause 2.02(b), the percentage rent payable by the Lessee for the Term will be reduced to the amount calculated in accordance with item eight of schedule A (as adjusted in accordance with clauses 2.01(b) and (c), and any other clause of this Lease).

23 The key terms of the leases forming part of the FLL for each of the Group Two restaurants are summarised below in so far as they relate to the option to reduce the percentage rent:

Restaurant - FLL | Commenced | End date | Higher % rent | Reduced % rent | Upfront amount / Prepaid rent ($) |

Gosford Imperial (RM-31) | 13 December 2010 | 13 November 2019 | 19.52 | 8.00 | 733,000 |

Mingara (RM-39) | 14 November 2011 | 14 November 2031 | 25.37 | 15.00 | 3,281,000 |

Bateau Bay (RM-43) | 12 December 2011 | 11 October 2019 | 25.44 | 15.00 | 3,185,000 |

24 There is no dispute that the option to reduce the percentage rent was exercised in respect of each of the Group One and Group Two restaurants and that the amounts described as prepaid rent in the offer letters, the FLL and contemporaneous tax invoices for each restaurant from MAL, were in fact paid by MFT.

25 MAL’s offer letters in relation to the Group One restaurants and the Group Two restaurants made no representation as to the possibility of renewal, and each FLL expressly precluded automatic renewal and required MAL’s consent to any assignment. As was apparent from Mr Mussalli’s evidence, however, he was well aware of MAL’s procedures and policies and was confident that he could satisfy all requirements to enable MAL to renew the FLLs.

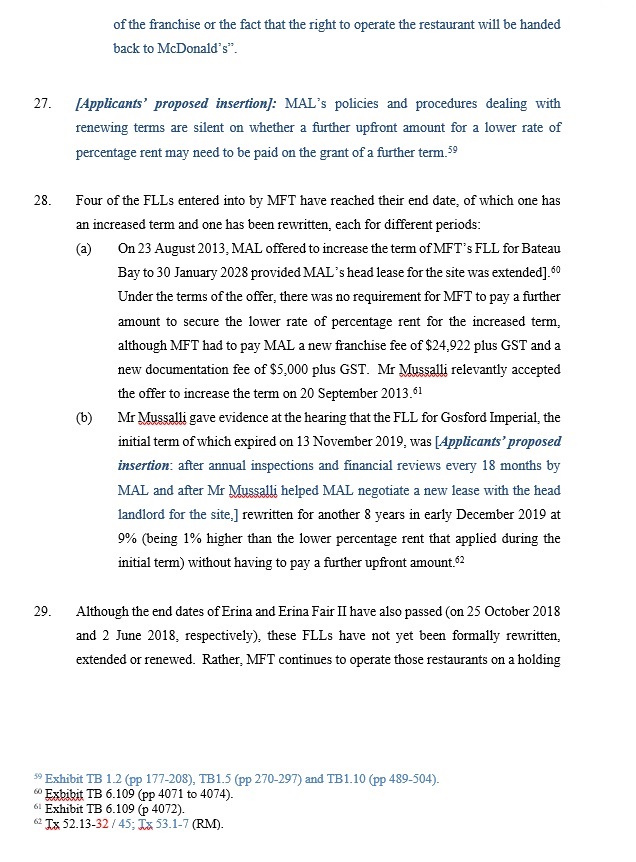

26 Four of the FLLs entered into by MFT have reached their end date, of which one has an increased term and one has been rewritten, each for different periods:

(1) On 23 August 2013, MAL offered to increase the term of MFT’s FLL for Bateau Bay to 30 January 2028 provided MAL’s head lease for the site was extended. Under the terms of the offer, there was no requirement for MFT to pay a further amount to secure the lower rate of percentage rent for the increased term, although MFT had to pay MAL a new franchise fee of $24,922 plus GST and a new documentation fee of $5,000 plus GST. Mr Mussalli relevantly accepted the offer to increase the term on 20 September 2013.

(2) Mr Mussalli gave evidence at the hearing that the FLL for Gosford Imperial, the initial term of which expired on 13 November 2019, was rewritten for another eight years in early December 2019 at 9% (being 1% higher than the lower percentage rent that applied during the initial term) without having to pay a further upfront amount.

27 Although the end dates of Erina and Erina Fair II have also passed (on 25 October 2018 and 2 June 2018, respectively), these FLLs have not yet been formally rewritten, extended or renewed. Rather, MFT continues to operate those restaurants on a holding over basis on the same terms as under its expired FLLs.

28 Apart from one store, Bateau Bay, the FLLs did not provide for any refund of the payment. The FLL for Bateau Bay, in cl 17 of the lease, provided for a refund of $470,000 of the total payment of $3,185,000 on expiry of the head lease on 12 October 2019 if MAL could not obtain a further term of the head lease.

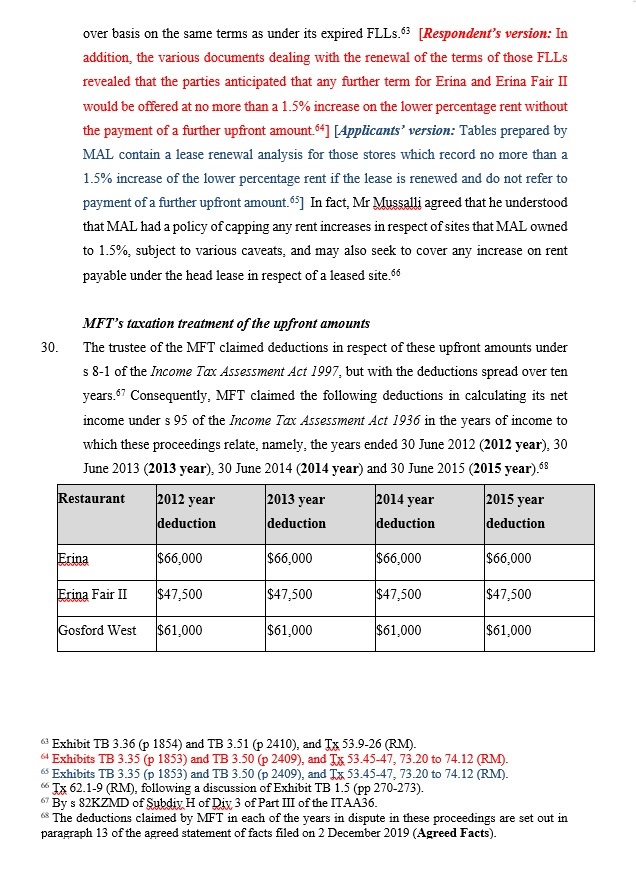

29 The trustee of the MFT claimed deductions in respect of these upfront amounts under s 8-1 of the ITAA 1997, but with the deductions spread over 10 years. Consequently, MFT claimed the following deductions in calculating its net income under s 95 of the ITAA 1936 in the years of income to which these proceedings relate, namely, the years ended 30 June 2012 (2012 year), 30 June 2013 (2013 year), 30 June 2014 (2014 year) and 30 June 2015 (2015 year).

Restaurant | 2012 year deduction | 2013 year deduction | 2014 year deduction | 2015 year deduction |

Erina | $66,000 | $66,000 | $66,000 | $66,000 |

Erina Fair II | $47,500 | $47,500 | $47,500 | $47,500 |

Gosford West | $61,000 | $61,000 | $61,000 | $61,000 |

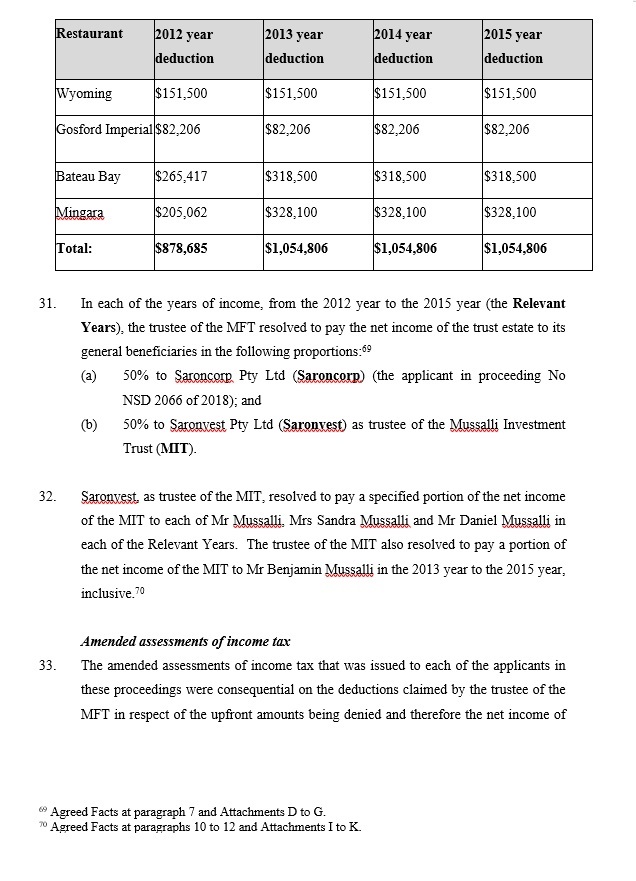

Wyoming | $151,500 | $151,500 | $151,500 | $151,500 |

Gosford Imperial | $82,206 | $82,206 | $82,206 | $82,206 |

Bateau Bay | $265,417 | $318,500 | $318,500 | $318,500 |

Mingara | $205,062 | $328,100 | $328,100 | $328,100 |

Total: | $878,685 | $1,054,806 | $1,054,806 | $1,054,806 |

30 In each of the years of income, from the 2012 year to the 2015 year (the Relevant Years), the trustee of the MFT resolved to pay the net income of the trust estate to its general beneficiaries in the following proportions:

(1) 50% to Saroncorp Pty Ltd (Saroncorp) (the applicant in proceeding No NSD 2066 of 2018); and

(2) 50% to Saronvest Pty Ltd (Saronvest) as trustee of the MIT.

31 Saronvest, as trustee of the MIT, resolved to pay a specified portion of the net income of the MIT to each of Mr Mussalli, Mrs Sandra Mussalli and Mr Daniel Mussalli in each of the Relevant Years. The trustee of the MIT also resolved to pay a portion of the net income of the MIT to Mr Benjamin Mussalli in the 2013 year to the 2015 year, inclusive.

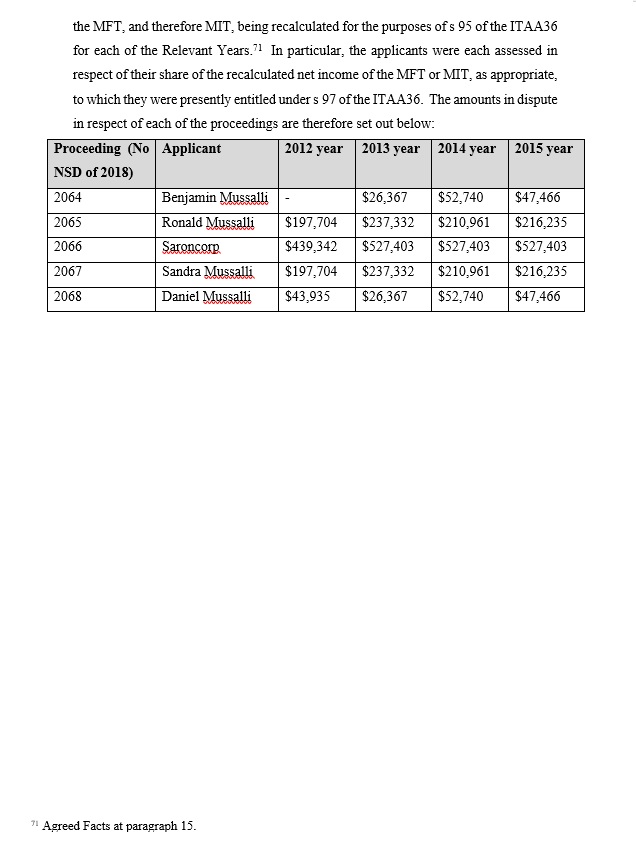

32 The amended assessments of income tax that were issued to each of the applicants in these proceedings were consequential on the deductions claimed by the trustee of the MFT in respect of the upfront amounts being denied and therefore the net income of the MFT, and therefore MIT, being recalculated for the purposes of s 95 of the ITAA 1936 for each of the Relevant Years. In particular, the applicants were each assessed in respect of their share of the recalculated net income of the MFT or MIT, as appropriate, to which they were at that time entitled under s 97 of the ITAA 1936. The amounts in dispute in respect of each of the proceedings are set out below:

Proceeding (No NSD of 2018) | Applicant | 2012 year | 2013 year | 2014 year | 2015 year |

2064 | Benjamin Mussalli | - | $26,367 | $52,740 | $47,466 |

2065 | Ronald Mussalli | $197,704 | $237,332 | $210,961 | $216,235 |

2066 | Saroncorp | $439,342 | $527,403 | $527,403 | $527,403 |

2067 | Sandra Mussalli | $197,704 | $237,332 | $210,961 | $216,235 |

2068 | Daniel Mussalli | $43,935 | $26,367 | $52,740 | $47,466 |

Principles

Identifying the advantage sought by the taxpayer

33 In Sun Newspapers Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [1938] HCA 73; (1938) 61 CLR 337 at 363 Dixon J said that in determining whether a payment was on capital or revenue account three matters are to be considered:

(a)the character of the advantage sought, and in this its lasting qualities may play a part, (b) the manner in which it is to be used, relied upon or enjoyed, and in this and under the former head recurrence may play its part, and (c) the means adopted to obtain it; that is, by providing a periodical reward or outlay to cover its use or enjoyment for periods commensurate with the payment or by making a final provision or payment so as to secure future use or enjoyment.

34 In Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v South Australian Battery Makers Pty Ltd [1978] HCA 32; (1978) 140 CLR 645 (South Australian Battery Makers) Gibbs ACJ said this at 655:

The real problem in the case is not to determine the character of the advantage sought, once it has been identified, but to decide what was the advantage sought by the taxpayer by making the payments. If the only advantage sought was the right to possession under the lease, and what was called ‘rent’ really answered that description, clearly the outgoings were entirely of a revenue nature. If on the other hand one advantage sought by the outgoings was the acquisition of a capital asset (the land and buildings), the fact that the payments were called ‘rent’, and were made periodically, would not necessarily prevent them from being in part outgoings of a capital nature.

35 At 656 Gibbs ACJ said:

I have said that in deciding whether outgoings made by a taxpayer are of a revenue or of a capital nature, it is necessary to consider ‘the character of the advantage sought’. In my opinion, in principle, that must mean the character of the advantage sought by the taxpayer for himself by making the outgoings.

36 In Commissioner of Taxation v Creer [1986] FCA 166 (Creer); (1986) 11 FCR 52 the Full Court dealt with a claim for deductions for rent. Justice Fisher concluded that the outgoings were of a capital nature and thereby not deductible as had been claimed. His Honour observed that “to label the payment ‘rent’ [did] not conclude the matter and, if anything, obscure[d] an understanding of the true nature of the outgoing”. The nature of the outgoing was primarily to be ascertained according to the true construction of the lease. Justice Fisher made the following observations:

(1) rent, as a recurring outgoing, is normally an allowable deduction (being on revenue account);

(2) in the case at hand, the question was whether the outgoing described as rent was more correctly to be classified as an outgoing of a capital nature;

(3) the amount called total rent, on a true construction of the lease aided by the evidence about the manner in which the total rent was calculated, supported the conclusion that the payment was of a capital nature; and

(4) the amount was not a periodic outlay covering the use of the premises for periods commensurate with the payments. Rather, it was a capital sum to secure the future use and enjoyment of the premises.

37 Justices Wilcox and Jackson agreed with Fisher J. Justice Wilcox also noted that the taxpayer was the author of the form of the transaction and, accordingly, it was his purpose that was relevant. On the evidence, the objective and subjective purposes of the taxpayer coincided. The relevant purpose for the pre-paid rent was to secure a taxation advantage, to transform what would otherwise have been expenditure on capital account into expenditure on revenue account.

38 In Commissioner of Taxation v Star City Pty Limited [2009] FCAFC 19; (2009) 175 FCR 39 (Star City) these propositions were identified:

(1) the relevant questions ((1) What is the money really paid for? and (2) Is what it is really paid for, in truth and in substance, a capital asset?) “are to be answered not solely by reference to the documentation which records the obligation to make the payment but also by reference to the business and practical effects and consequences achieved”: [17]-[18] citing Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Limited v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [[1953] HCA 68;] (1953) 89 CLR 428 at 454;

(2) “[t]he enquiry as to whether an outgoing is on capital or revenue account looks to the business and practical effects and advantages sought in the whole context…”: [20] citing Tyco Australia Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2007] FCA 1055; (2007) 67 ATR 63 at [47];

(3) “the courts will always consider the substance of a transaction in characterising the character of the advantage which is sought to be obtained in determining whether an outgoing is on revenue account or whether, as here, on capital account and thus excluded from deductibility”: [29] citing Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Broken Hill Pty Co Ltd [2000] FCA 1431; (2000) 179 ALR 593 at [50]; and

(4) “labels are not determinative and surrounding circumstances may be resorted to determine the true characterisation of a payment in an appropriate case”: [63].

39 In AusNet Transmission Group Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2015] HCA 25; (2015) 255 CLR 439 these propositions were stated (excluding citations except where indicated):

(1) “Dixon J said that the distinction between capital and revenue account expenditure corresponded with the distinction between the business entity, structure or organisation set up or established for the earning of profit and the process by which such an organisation operates to obtain regular returns by means of regular outlay”: [21];

(2) “…an intangible asset might, according to its nature and function in the conduct of the business, be properly characterised as forming part of the structure of the business and the cost of its acquisition as a capital cost”: [21];

(3) “…the distinction also depends upon ‘what the expenditure is calculated to effect from a practical and business point of view, rather than upon the juristic classification of the legal rights, if any, secured, employed or exhausted in the process’”: [22] citing Hallstroms Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1946] HCA 34; (1946) 72 CLR 634 at 648;

(4) the issue is what the advantage sought by the taxpayer was in making the payment: [23];

(5) the mere fact that payments are called rent and are made periodically would not necessarily prevent them from being in part outgoings of a capital nature: [23] citing Commissioner of Taxation v South Australian Battery Makers Pty Ltd [[1978] HCA 32;] (1978) 140 CLR 645 at 655; and

(6) it is necessary to “have regard to the ‘whole picture’ of the commercial context within which the particular expenditure is made, including most importantly the commercial purpose of the taxpayer in having become subjected to any liability that is discharged by the making of that expenditure. It is, where necessary, to ‘make both a wide survey and an exact scrutiny of the taxpayer’s activities’”: [74]

40 In Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Sharpcan Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 36; (2019) 93 ALJR 1147 (Sharpcan) at [18] the High Court said:

Authority is clear that the test of whether an outgoing is incurred on revenue account or capital account primarily depends on what the outgoing is calculated to effect from a practical and business point of view. Identification of the advantage sought to be obtained ordinarily involves consideration of the manner in which it is to be used and whether the means of acquisition is a once-and-for-all outgoing for the acquisition of something of enduring advantage or a periodical outlay to cover the use and enjoyment of something for periods commensurate with those payments. Once identified, the advantage is to be characterised by reference to the distinction between the acquisition of the means of production and the use of them; between establishing or extending a business organisation and carrying on the business; between the implements employed in work and the regular performance of the work in which they are employed; and between an enterprise itself and the sustained effort of those engaged in it. Thus, an indicator that an outgoing is incurred on capital account is that what it secures is necessary for the structure of the business.

(excluding citations)

41 At [33] their Honours reiterated:

As has been observed, the determination of whether an outgoing is incurred on capital account or revenue account depends on the nature and purpose of the outgoing: specifically, whether the outgoing is calculated to effect the acquisition of an enduring advantage to the business. And the identification of what (if anything) is to be acquired by an outgoing ultimately requires a counterfactual, not an historical, analysis: specifically, a comparison of the expected structure of the business after the outgoing with the expected structure but for the outgoing, not with the structure before the outgoing. Other things being equal, it makes no difference whether the outlay has the effect of expanding the business or simply maintaining it at its present level. If a once-and-for-all payment is made for the acquisition of an asset of enduring advantage which, once acquired, forms part of the profit-earning structure of the business, the payment is incurred on capital account.

(original emphasis)

An objective determination of the advantage is required

42 The nature of the advantage sought by the taxpayer is to be determined objectively: Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Ashwick (Qld) No 127 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 49; (2011) 192 FCR 325 at [107] and [108] citing St George Bank v Commissioner of Taxation [2008] FCA 453; (2008) 69 ATR 634.

43 The Commissioner submitted that to the extent the applicants sought to confine consideration to Mr Mussalli’s subjective state of awareness, the applicants’ approach was contrary to principle. I agree. The Commissioner made the following submissions in support of this position, excluding citations:

(a) There is authority for the proposition that the purposes of the entity that incurs an outgoing is relevant to establishing whether there is a sufficient nexus between a loss or outgoing and the derivation of assessable income, or the carrying on of a business for that purpose, for the purposes of s 8-1(1) of the ITAA97. The applicants have relied on this authority in support of their submission that documents that were not in the possession of the trustee of the MFT, or were not considered at the time it incurred the upfront amounts, are irrelevant.

(b) Furthermore, the authorities dealing with establishing the existence of a sufficient nexus for the purposes of the positive limbs of s 8-1(1) of the ITAA97 emphasise that the task of determining the taxpayer’s purpose in incurring expenditure is generally performed by reference to objective circumstances. Questions of subjective purpose or motive may be of limited relevance in circumstances where, for instance, voluntary expenditure produces no assessable income or a disproportionately small amount of assessable income when compared to the expenditure, or the expenditure does not achieve its intended result.

(c) However, there is no support for the proposition that those authorities apply equally to the characterisation of expenditure for the purposes of s 8-1(2). In particular, there is no support in the authorities dealing with s 8-1(2)(a) that the surrounding circumstances to which regard may be had are limited to matters of which the taxpayer was subjectively aware, or only those documents that the taxpayer knew about at the time it incurred the outgoing. Indeed, the approach taken by Dowsett J to the evidence in Star City illustrates that courts may properly consider matters not embodied in documents in the payer’s possession or control at the time the outgoing was incurred, provided they are relevant as part of the surrounding circumstances.

(d) Finally, it would be illogical to treat only those matters and documents of which a taxpayer was subjectively aware as being relevant, as it would mean that the income tax treatment could differ depending on whether a taxpayer was well-informed or wilfully ignorant…

44 I accept these submissions. The fact that Mr Mussalli gave evidence that he did not read certain documents, such as disclosures by MAL, does not mean that those documents are irrelevant. The documents still form part of the relevant surrounding circumstances. In any event, and as explained below, Mr Mussalli was confident that he understood MAL’s policies and procedures and thus did not feel he had to read the documents to know what he had to do to meet MAL’s requirements including for renewal of the FLLs.

Mr Mussalli

45 Mr Mussalli was the controlling mind of the trustee of the MFT who had worked for MAL in the operational side of its business, including the management of MAL owned stores, ultimately as a senior executive from 1983 until 2005, although he was not involved in MAL’s financial operations.

46 I have already observed above that the fact that Mr Mussalli did not read certain documents does not make them irrelevant. There was a factual dispute about whether Mr Mussalli ever received certain disclosure documents said to have been provided to him by MAL in the relevant transaction documents. Mr Mussalli’s cross-examination proceeded on the assumption that he had received these documents but had not read them. In re-examination Mr Mussalli said he had in fact never received the documents in question. The Commissioner submitted that it was very unlikely that an experienced franchisor such as MAL would routinely omit to attach to transaction documents the disclosure documents which it was required to provide. I agree. Taking this into account, I consider that the better view of the evidence as a whole is that Mr Mussalli did receive the disclosure documents from MAL but chose not to read them, most probably because he considered that given his role with MAL he was already familiar with what he needed to know about the operations of MAL and the restaurants. Mr Mussalli said as much in this excerpt from his cross-examination:

But you – while you had been supplied with these documents, you had not in fact read or studied them?---Correct.

Again - - -?---I didn’t get legal advice either.

I understand. And, again, was that because you thought you were sufficiently familiar with their contents?---Correct.

47 Mr Mussalli’s subsequent evidence that the documents were not in fact provided by MAL is difficult to reconcile with his evidence, which seems more objectively likely, that given his experience with MAL he did not feel it necessary to read the disclosure documents.

48 As also noted, Mr Mussalli’s decision not to inform himself about the content of MAL’s disclosure documents as part of the transactions into which he caused MFT to enter cannot affect the proper characterisation of the payments. As the Commissioner submitted, and in any event, Mr Mussalli was familiar with MAL’s policies and procedures and its documents regarding the “purchase and sale” of McDonald’s Family Restaurants. Mr Mussalli gave this evidence:

…so you were the regional manager for New South Wales and ACT dealing with all McDonald’s stores in that region?---Yes.

From an operations perspective.

Yes. And you oversaw franchisee stores as well as McOpCo stores?---Yes.

And you would have been familiar with McDonald’s existing policies concerning the operation of McDonald’s restaurants?---That’s correct.

The circumstances in which McDonald’s would grant a franchise to a new franchisee?---Yes.

And you were involved in the process of granting franchises to new franchisees?---The operations process, yes.

49 According to Mr Mussalli, based on his experience, he did not need to read MAL’s policy documents in order to understand MAL’s policies and the way in which MAL operated.

50 Mr Mussalli gave evidence about his dealings with Westpac as financier. The funding proposal is recorded in Westpac’s documents as “[t]o fund purchase of McDonald’s company stores at Gosford West, Wyoming with 20 year franchise agreements and Erina, Erina Fair with approx. 13 year franchise agreements”. Mr Mussalli gave evidence confirming that Westpac’s documents reflected what he had communicated to them. The evidence was given in this exchange:

And the purpose is stated to fund purchase of McDonald’s company stores at Gosford West, Wyoming with 20 year franchise agreements and Erina, Erina Fair with approximately 13 year franchise agreements?---Yes.

Was that the purpose you communicated to the bank?---Yes. That was what was in the offer letters.

51 Mr Mussalli said that he caused MFT to make the payments because in each case he believed MFT would be financially better off. He gave this evidence by way of example:

I took up the offer to prepay rent for each of these four stores. By way of explanation for my reasons, the letters of offer enclosed profit and loss projection summaries prepared by MAL. There are two pages to each of the summaries, with each page containing three scenarios identifying the different levels of net income that I could earn depending on the level of sales the store made – for example, the Erina store scenarios contemplated turnovers of either $3.76 million, approximately $3.86 million or $3.96 million. The main difference between the two pages is the prepayment of rent.

By way of illustration, the first page of the Erina projections assumes that no prepayment of rent is made so that the percentage turnover rent is fixed at 11.82%. The net income projected under the different scenarios ranges from $87,508 to $125,284. The second page assumes that a prepayment of rent of $660,000 is made to reduce the percentage turnover rent to 8.25%. The net income projected under the different scenarios on this page range from $170,784 to $215,710.

The projections also included assumptions about funding. These assumptions were based on borrowing a majority of the funds required to pay for opening costs, equipment, and (on the second page) the prepayment of rent. The assumptions were more favourable than my own situation, as I knew the funds I had available to pay part of the identified costs were going to have to be drawn down from my existing home equity loan as well as using additional borrowings for the remainder, rather than borrowing only (around) 75% of the necessary funds as contemplated in the projections. However, despite the additional cost of funds that t expected I would have to incur because I was effectively borrowing 100% of any outlay, I still considered that the net income derived from the stores would be higher if I prepaid rent rather than not.

The difference in the net income arising from the prepayment of rent indicated clearly to me that if I could prepay the rent I would be better off.

Moreover, I formed the view that based on my operational experience, I would be able to increase the annual sales turnover of the store to more than $3.96 million in the case of the Erina store. It was clear to me that the higher the turnover, the greater savings in turnover rent, so that I or my entity would potentially be better off by even more than indicated in MAL’s projections by prepaying rent.

52 Mr Mussalli also gave evidence that:

(1) he was familiar with MAL’s expectations, policies and procedures;

(2) he was confident he understood MAL’s policies and what was required of him as a licensee;

(3) he was confident that he could meet MAL’s requirements including to obtain renewed FLLs of sites held on shorter term FLLs (due to the term of the head lease MAL held); and

(4) he was happy to pay the same upfront amount for the Bateau Bay restaurant as for Mingara as he had an expectation that the Bateau Bay restaurant would obtain a 10 year renewal and that he would therefore be allowed to pay the same lower percentage rent for both stores throughout his period of operations. His evidence was as follows:

While in the case of Bateau Bay, you were paying 3.2 million for only 7.8 years worth of rent reduction?---Correct. However, they were – McDonalds was confident that they would get a renewal and they did.

Yes. And did you know how long the renewal would be for?---At that time?

Yes?---They were after 10 years.

Yes?---And they got 10 years from the landlord.

I think they got about 8.3. Do you recall?--- .....

Yes. And so you were happy to pay the same upfront amount, even though the periods were very different because you had an expectation that the Bateau Bay store would be extended for an extra 10 years?---Yes.

Or more if McDonalds was successful?---Yes. If - - -

And that you would therefore be allowed to pay the same lower rent, the 15 per cent, all through – both stores all through the period of your occupancy of the store?---Correct.

53 Mr Mussalli also agreed that paying the upfront amount for Mingara would mean that he obtained the benefit of the reduced percentage rent for that store for 20 years plus any extended renewed period after the expiry of the 20 years. Further, he confirmed that his understanding of MAL’s policy was that MAL would renew FLLs (subject to the franchisee meeting its requirements) on the basis of the reduced percentage rent if the payment had been made with the percentage rent increase capped for MAL owned sites at 1.5%. In this regard, Mr Mussalli’s understanding accorded with MAL’s policy documents to that effect. This evidence was given:

…If it was a site that McDonald’s owned, there was a one and a half per cent cap on the increase but if it was owned by someone else and there was potentially an increase on the head lease, McDonald’s might look for you to pay some share of that. So I – and then there’s more – but I just wanted to confirm that what is stated here about the increase of 1.5 per cent, 5 subject to the various caveats, is in accordance with your understanding of what the rollover or the new term lease would be?---Yes.

Yes?---Yes.

54 Mr Mussalli gave evidence that there are two types of stores – company operated known as McOpCo stores and franchise operated. An exiting franchisee had the option of assigning their rights to a new franchisee or having their rights acquired by MAL. He gave this evidence:

…so when a new franchisee became a franchisee of an existing McOpCo store, they would enter a lease and licence arrangement with McDonald’s?---Correct.

…

And typically, what was the period of the lease and licence?---If McDonald’s owned the land it would be 20 years.

Yes?---If McDonald’s leased the property, would be for the remainder of that lease. For the remainder of the head lease.

Yes. And in the circumstance where a lease and licence – Full Lease and Licence was coming towards an end, the franchisee, assuming the head lease wasn’t going to run out, really had two options: they could either seek a renewal of the lease and licence for another period or they could seek to assign it to another franchisee?---With McDonald’s approval, yes.

…

…but the existing licensee could ask for a renewal - - -

Yes?--- - - - and McDonald’s would determine whether they would renew it or not.

Yes?---Sometimes they did. Sometimes they didn’t.

Yes. So, generally, someone who is facing the end of their 20 year 10 licence period had two choices: either apply to McDonald’s for renewal and have it accepted, and therefore have their licence rolled over for another 20 year period, or if they had either lost interest in running a restaurant or they did not think McDonald’s were likely to renew, they could seek to assign the restaurant to a new franchisee of McDonald’s selection?---They could only assign the remainder of the lease.

Yes. But on assignment, the new assignee would be granted a full licence – a full 20 year licence?---Well, that’s up to McDonald’s to decide.

Yes. But the practice of McDonald’s was, provided they either owned the land or had a lease, that the assignment would be a new assignment for the period for - - -?---If they agreed to it. Yes.

55 Mr Mussalli also gave evidence that when he was State Manager for NSW for MAL, although MAL’s documents said there were no franchises that were not renewed when they expired, there were in fact a few franchisees who had chosen to exit. Those franchisees assigned their rights to another franchisee or to MAL. He said that sometimes MAL renewed FLLs and sometimes it did not. Franchisees who did the wrong thing could also have their FLL terminated. Overall, however, to his knowledge a substantial number of stores had operated for more than 20 years by the same franchisee which was a result of MAL renewing the FLLs for those stores to the existing franchisee. As I have noted above, he was also confident he could meet all MAL’s policy requirements in order to obtain renewals of FLLs. This evidence has to be weighed with his evidence in re-examination that he did not have any assurance from MAL that the FLLs would be renewed on expiry.

56 The Commissioner submitted, and having regard to the evidence referred to above I accept, that the evidence disclosed that Mr Mussalli was confident at the time of entering into each FLL that he would be able to secure renewals in accordance with MAL’s policy. This evidence was given:

So you were in a situation where some of your licences had quite a short period to run. As low as, I think, about 7.8 years?---Yes.

And, therefore, the viability for you of a continuing thing would depend on you getting a renewal; a new term?---And my performance.

Yes. Well, assuming, based on your undoubted expertise, that you were able to perform to McDonald’s standards, you had an important interest in having these short-term licences rolled over and renewed?---Yes.

And that’s a matter that was dealt with by the new term policy?---Mmm.

Yes?---Yes.

And I just want to suggest to you that the – in your particular circumstance where you – four of your seven licences are on short terms – less than 10 years. As low as seven and a-half or 7.8 to be precise. The new term policy is, actually, very important to you?---So, again, it’s a policy that I was confident that I was aware of what my requirements were as a licensee - - -

Yes?--- - - - to get a new licence or to be rewritten.

Yes?---And I didn’t need – I didn’t think I needed to go and read it in thorough detail

- - -

Right?--- - - - to be successful in getting rewritten.

Right. And - - -?---And as restaurants have been rewritten.

57 The stores that had been rewritten (granted a new FLL) were Bateau Bay and Gosford Imperial. Otherwise the MFT continues to hold over the restaurants at Erina and Erina Fair II.

58 Mr Musalli confirmed that under MAL’s policies an exiting franchisee could expect to recover 5 or 5.5 times the adjusted profit of the store on either transferring the store back to MAL or to a new franchisee.

The accounting evidence

The payments

59 I accept the Commissioner’s submission that the way in which the payments were calculated is relevant to the characterisation of the payment: Creer at 59-60 and Star City at [192] and [259]. It follows that to the extent the evidence of Mr Halligan and Mr Lonergan, forensic accountants, dealt with the way in which the payment had been calculated their evidence is relevant and admissible. The fact that their evidence involved expert inference about how MAL had calculated the payments does not undermine the admissibility or cogency of their evidence.

60 I do not accept the applicants’ submission that as Mr Halligan has never carried on a business of operating a McDonald’s Family Restaurant or worked for MAL or MFT he has no expertise in relation to what advantage MFT sought in making the prepayments. The submission misses the point. As accountants both Mr Halligan and Mr Lonergan could give expert opinion evidence as to how, in their view, the payments had been calculated. That fact is part of the broader context within which Mr Mussalli caused MFT to make the payments and is relevant to their legal character as capital or revenue outgoings. It may be accepted, as the applicants submitted, that MAL unilaterally determined the amount of the payments. That does not prevent the accounting evidence, at least to the extent it dealt with how the payments had been calculated, from being relevant. Nor does the fact that MAL was apparently indifferent as to whether MFT made the payments and obtained the lower percentage rental or did not make the payments and paid the higher percentage rental.

61 The essential dispute between the experts was expressed in their joint report in these terms:

The experts disagree on MAL’s figure for of the upfront amount:

(a) Halligan’s opinion is that in its selling models MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’;

(b) Lonergan’s opinion is that whilst prima facie the upfront amount is the difference between the “agreed price of the restaurant” and the ‘value of the equipment’, the upfront amount represents the capitalised value / net present value of the rental differential terms offered to Saronbell.

62 Mr Halligan explained that:

… for each selling model, MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’ as shown in the following table. For example, in the case of Erina the cell O28 of the P&L worksheet of the selling model shows ‘Prepaid Rent’ of $660,000 (i.e. the upfront amount). The Excel formula underlying that cell (which is only visible in the electronic version of the model) calculates this figure of $600,000 by taking the figure of $1,260,000 for the ‘Agreed Price’ that appears in cell B40 of the Valuation worksheet and deducting from it the figure of $600,000 for ‘Equipment’ that appears in cell O27 of the P&L worksheet.

63 According to Mr Halligan:

…the upfront amount is a not a prepayment of rent due under the lease agreement but rather a payment to ensure that the lease will contain a particular term that Saronbell desires – that is, a term that provides for percentage rent at the lower rate stated in the letter of offer or proposal for the entire term of the lease.

64 Mr Lonergan explained that:

… the correct description is ‘shows’ not ‘calculates’. Just because the amount appears as the last item (or second last) in a table, does not mean that is how the item was calculated.

MAL’s precise calculations are not known. However, given their use of capitalised earnings to calculate the total value of the restaurant, the upfront amount is the present value of the rental differential offered to Saronbell.

65 According to Mr Lonergan:

… in accordance with the transaction documents, the upfront amount is a prepayment of the rental differential arising from the two alternate rent terms offered to the lessee by MAL in the transaction documents. The dollar amount is the present value of that rental differential.

66 Mr Halligan disagreed with Mr Lonergan, observing that:

First, the calculation of the upfront amount is not a present value calculation of the rent differential or a present value calculation of anything at all. As noted on page 8, Halligan notes that in the selling model for each restaurant MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’. Hence, it is clear that the calculation of the upfront amount is simply the deduction of one number (the value of equipment) from another (the agreed price of the restaurant) and not a present value calculation.

Second, notwithstanding that the calculation of the upfront amount is not a present value calculation, there is nothing about its inputs that means it ‘reflects’ or ‘relates solely to’ a present value calculation of the rent differentials. As noted, the inputs are the agreed price of the restaurant and the value of equipment, which are determined as follows:

(a) The agreed price of the restaurant is calculated by taking the annual profit and multiplying it by a capitalisation multiple. The annual profit is calculated after deducting rent that includes percentage rent at the lower rate. The higher rate of percentage rent is not an input to the calculation of the annual profit or indeed to the calculation of any other figure in the selling model. As a result of the capitalisation, the agreed price is the present value of the future stream of profits.

(b) The value of equipment is a fixed sum determined outside of the selling model.

…

Third, the higher rate of percentage rent cannot be determined without first determining the upfront amount. The higher rate of percentage uses the upfront amount as an input. …the higher rate of percentage rent is a rate derived by adding to the lower rate of percentage rent an additional percentage of gross sales revenue (estimated for the first year of Saronbell’s operation of the restaurant) which, when applied to the estimated gross sales revenue in the first year, results in an amount equal to the amount of prepaid rent divided by the valuation multiple.

67 I preferred the evidence of Mr Halligan to that of Mr Lonergan.

68 As the Commissioner submitted, Mr Halligan’s evidence was that the upfront amount was calculated by MAL by subtracting the value of equipment from the “agreed price of the restaurant”. The agreed price was determined through MAL’s valuation of the restaurant using a capitalisation multiple of between 4.76 and 5.50 times the anticipated profit of that restaurant in a single year, irrespective of the term of the particular FLL. Further, in calculating the anticipated profit Mr Halligan’s evidence was that MAL’s models always utilised the lower percentage rent. Mr Lonergan initially agreed with the proposition that it is the lower rent that MAL uses exclusively in their calculations to calculate the upfront amount but then said that it was not possible to know where MAL had started from in its calculation of the payments. However, as the Commissioner submitted, the problem with this aspect of Mr Lonergan’s evidence is that the electronic models used by MAL to calculate the agreed price, upfront amount and the higher percentage rent began with certain figures that were “hardcoded”, including the lower rate of percentage rent, the multiple used to determine the agreed price and the value of the equipment. This strongly supports Mr Halligan’s evidence about the way in which MAL had calculated the payments.

69 I also accept the Commissioner’s submissions about the difficulty with Mr Lonergan’s evidence that the upfront amount reflected a present value calculation of the difference between the lower and higher percentage rents. The analysis never yields the precise amount of the payment. In one case, Gosford Imperial, the difference between the present value as calculated by Mr Lonergan and the payment is 11.8% ($646,196 compared to $733,000). In another, Bateau Bay, the difference is 12.1%. In two other cases the difference is 8% or close to 8% (Wyoming and Gosford West). The degree of difference between Mr Lonergan’s calculations of net present value of the difference between the higher and lower percentage rents and the payments depend on the duration of the cash flows so that the “shorter cash flows, the more inclined the capitalised earnings method is to misstate the real value”. As the Commissioner submitted the “equivalence” that Mr Lonergan proposed between the payments and the present value of the difference between the higher and lower percentage rents is not actual equivalence and the approximations of equivalence only hold good for FLLs granted for a term of more than 10 years.

70 The Commissioner also submitted, and I accept, that Mr Lonergan’s approach involved circular reasoning in that the evidence was that the payments were calculated by MAL as an output using the lower percentage rent as an input which was then used by MAL as an input into the calculation of the higher percentage rent. As the Commissioner put it, Mr Lonergan’s calculations of the present value of the rent differential simply reverse MAL’s methodology for calculating the upfront amount. I accept also Mr Halligan’s evidence that MAL’s electronic model did not calculate the payments using a discounted cash flow analysis to produce a present value of the rent differential. Mr Halligan also noted that extracts of MAL’s models had been provided to Mr Mussalli for some of the restaurants and as Mr Halligan explained:

…there are extracts from it attached to this very letter that we’re looking at and from those extracts you can work backwards and should be able to work backwards to determine the agreed price or the value of the restaurant that MAL put on it and which you should also then be able to work backwards to determine that the sum of the upfront amount and the equipment equals the agreed value of the restaurant.

71 For these reasons I accept the Commissioner’s submission that the way in which MAL calculated the payment was as the residual left over after deducting the value of the equipment from the agreed price determined by reference to a valuation based on a multiple of between 4.76 and 5.50 times earnings, irrespective of the term of the FLL.

Accounting treatment of payments

72 The Commissioner referred to the observations of Hill J in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Citibank Limited [1993] FCA 607; (1993) 44 FCR 434 at 443 that while in some areas a legal or jurisprudential rather than commercial view is taken “this does not mean that accounting evidence has been seen to be irrelevant”. At 444-445 Hill J referred to the usefulness of accounting evidence in cases concerning the characterisation of receipts as on capital account. In Tyco Australia Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2007] FCA 1055; (2007) 67 ATR 63 at [82] Allsop J (as he was) noted that accounting evidence cannot be determinative but did not suggest it was irrelevant.

73 Against this background it may be noted that the trustee of the MFT records the payments as an asset in its balance sheet. As the Commissioner noted:

The experts agreed that this accorded with the accounting treatment for ‘prepaid lease payments’ under Australian Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (Australian GAAP), irrespective of whether the upfront amount was characterised as prepaid rent or as something else for accounting purposes. To that end, the experts agreed that the appropriate accounting standard under Australian GAAP is set out in AASB 117 Leases, although strictly the trustee of the MFT was not required to comply with AASB 117 Leases (or its predecessor) because it prepared special purpose financial statements.

(original emphasis).

74 The accountants disagreed about how the trustee should have characterised the payments for accounting purposes. Mr Halligan explained:

…there is a difference between acquiring an asset called a lease right and acquiring an asset that’s prepaid rent, and it has to do with, from a accounting point of view, the issue of how refunds or shortfalls might be dealt with. Acquiring a lease right is a once and for all acquisition of an asset. Prepaying rent is something that’s contingent on what happens in the future, and what has to happen in the future is there has to be a charge made for rent to which the prepayment can be applied. Now, over time, bearing in mind that the percentage rent is a contingent rent, it depends on the amount of the gross sales in the previous month and can’t be determined until those gross sales are known.

And, of course, the gross sales might be more or less than that that was expected at the time that the upfront amount was determined. It could be that the total rent – total percentage rent, I should say, exceeds the upfront amount, in which case, in the normal course, Saronbell would be called upon to pay further percentage rent, or alternatively, by the end of the lease, the total percentage rent might be less than the upfront amount, and which you would normally expect that McDonald’s would have an obligation to refund the difference. Now, that will affect the accounting for this asset as a prepayment, but not the accounting for the asset as a lease right because there won’t be any refunds or shortfalls, and the lease right is simply an asset that’s acquired.

75 Mr Halligan posited that the payments could be characterised as a “lease right” or “lease agreement” or might be “goodwill” or going concern value. Mr Halligan gave this evidence

But if it’s goodwill, can you please explain how a change in the means by which the rent is determined is going to affect the propensity of customers to 5 come in and spend money in the McDonald’s store.

MR HALLIGAN: Well, it doesn’t. And I haven’t proposed that.

76 Mr Halligan had in mind the accounting concept of goodwill, not the legal concept. He explained:

…there’s a difference between legal goodwill and accounting goodwill. Legal goodwill is focused very much on the attractive force of custom. Accounting goodwill is not characterised, at least in the accounting standards, by its sources, but by its measurement. And in accounting purposes, goodwill is the difference between the value of the whole, the value of the business, and the value of all the other assets, including the identifiable and tangible assets. And so it is the value of what’s called the unidentifiable and tangible assets.

77 Mr Lonergan said:

If you have a choice between prepaying and not prepaying, all your cash flows in every respect other than the prepayment and the rental saving you make are identical. It therefore cannot be properly said or fairly said that by virtue of making a prepayment you acquire some form of intangible asset or goodwill – put aside what it might be called – because it does not happen because there is no value extra created by entering into the prepayment of lease.

78 The Commissioner made the following submission:

…it is unnecessary to resolve the question of whether a transfer of goodwill has occurred in this case because the Commissioner does not submit that the upfront amount was paid for legal goodwill. The Commissioner is not required to identify a particular asset to which the upfront amount related for income tax purposes in order to establish that the upfront amount was of capital or was capital in nature. Indeed, an outgoing may be of a capital nature notwithstanding that no asset has been acquired as a result of that outgoing being incurred. Therefore, all that is necessary is for the Commissioner to establish that the advantages sought by the expenditure were of capital or were capital in nature.

79 In support of this submission the Commissioner referred to s 14ZZO of the TAA 1953 which places the burden of proving that the assessment is excessive on the applicants and the statement in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Email Limited (1999) 42 ATR 698 at [32] as follows:

Where moneys have been employed in the acquisition of the asset, the nature of what is acquired will ordinarily cast light on whether the outgoing is of a capital or revenue nature.

But an outgoing may be of a capital nature, notwithstanding that no asset has been acquired as a consequence of the outgoing…

80 On this basis the Commissioner submitted that the Commissioner relied on Mr Halligan’s evidence in this regard only for the purpose of establishing that it was appropriate for the trustee of the MFT to have accounted for the payments as an asset. I accept the Commissioner’s submission. As explained below, to the extent that use may be made of this evidence it supports the Commissioner’s contentions rather than those of the applicants.

The applicants’ submissions

81 The applicants submitted that the payments were revenue outgoings and not capital outgoings or outgoings of a capital nature because, from a practical and business point of view, the advantage which the MFT sought in making them was the use and enjoyment of each store over the term of the lease to carry on the business of operating McDonald’s Family Restaurants. Mr Mussalli was the controlling mind of the MFT so it is the advantage he sought to obtain which is relevant.

82 The applicants noted that MFT paid rent under each lease to occupy a store in which it carried on its business under the licence granted by MAL. Whether MFT made the payments or not the rent payable for each store had two components, the base rent and the percentage rent. According to the applicants, the liability for the payments was incurred after the FLL had been agreed. As discussed above, I do not accept this legal characterisation of the transactions. The liability to make the payments for the Group One restaurants was incurred on entry in the FLL. The liability to make the payments for the Group Two restaurants was incurred on exercising the option in the FLL.

83 In any event, the applicants submitted that what the trustee of the MFT sought to achieve in making the payments was a reduction in the percentage used in calculating the percentage rent and thus the amount of percentage rent payable each month from the commencement of each lease. According to the applicants, just as the base rent and percentage rent were payable for the occupancy of each store, so too were the upfront payments.

84 The applicants noted that having made the choice to accept the FLLs on the terms MAL offered MFT’s only choice in relation to the payment of rent was to make or not make the upfront payments. MFT had no say in the calculation of the amount of any of the payments or the reduction of the percentage in turnover rent. These matters were unilaterally decided by MAL and presented to MFT on a “take it or leave it” basis”. As the applicants put it:

MFT chose to make each prepayment rather than pay a higher percentage rent for each store because, based on his experience, Mr Mussalli concluded that it would be financially better off paying the lower percentage rent. He decided that MFT would pay less rent if it made the prepayment because MFT would significantly increase the turnover projected by MAL in respect of the leases of the Erina, Erina Fair, Gosford West and Wyoming stores (the 2006 leases) and the current turnover of the Gosford Imperial, Mingara and Bateau Bay stores (the latter leases). The higher the turnover the greater the savings to be made.

(original emphasis).

85 According to the applicants there is no material difference between the offers for the 2006 (the Group One) leases and the offers for the latter (or Group Two leases) in terms of the characterisation of the upfront payments. In the words of the applicants:

In each case the making of the prepayments did not affect the structure of MFT’s business. The structure of the business included each lease, licence and plant & equipment, the prepayments were not made to obtain any of them; MFT was offered and acquired them from MAL regardless of any prepayment. MFT remained entitled to exclusive possession of each store for the term of the lease for which it was required to pay rent. The only difference was the quantum of the rent it would pay. Adopting the analysis of the High Court in Sharpcan at [33], the relevant counterfactual or expected structure of the business but for the outgoing is in fact identical to the structure of the business after the outgoing. The only change is to the amount of recurrent rent payable in the future.

86 The applicants also noted:

(1) each of the payments were described and treated by MFT and MAL as prepaid rent in the letters of offer from MAL to MFT (including the form of acceptance and, in the case of the offers for the 2006 leases), the appended profit and loss projections, the full licences and leases, and the tax invoices;

(2) the payments are distinguishable from the payments described as rent in Star City which were really paid for the exclusive casino licence and not for the quiet enjoyment of the premises. The payments are also distinguishable from the payments in Creer which were for a reduction in the purchase price of the leased units;

(3) MFT obtained an immediate and recurrent benefit from the payments because they reduced the amount of the percentage rent payable each month from the commencement of the lease;

(4) MAL was indifferent as to whether MFT made the payments: the (higher) specified percentage rent was payable unless MFT chose to make the payments;

(5) MFT accounted for the payments as prepayments of rent;

(6) the period over which the payment reduced the percentage rent does not characterise it as capital. As s 82KZM of the ITAA 1936 recognises, payments covering more than 10 years can be deductible; and

(7) the payments were recurrently made by MFT on seven occasions in carrying on its business of operating McDonald’s Family Restaurants at each of the stores it leased (by analogy to Healius Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCA 2011 at [55]).

87 The applicants submitted that the payments were components of the rent and that in making them MFT did not seek to obtain and did not obtain any asset, right or advantage other than to occupy and use each store in carrying on the business. The applicants noted that as a general rule rent is deductible even if it is paid in a lump sum: Texas Co (Australasia) Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1940] HCA 9; (1940) 63 CLR 382 at 468; Commissioner of Taxation v Firth [2002] FCAFC 95; (2002) 129 FCR 450 at [69]; National Australia Bank Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [1997] FCA 514; (1997) 80 FCR 352 (NAB) at 365.

88 The applicants submitted that as in NAB at 367 “it would be odd” if percentage rent was deductible but the payments upfront in a lump sum were not deductible. According to the applicants, MFT did not obtain by the payments:

(1) the lease, or an option for a lease at a lower rent than would otherwise be charged, of each store. According to each offer made to it, MFT was entitled to each lease before choosing to prepay and without having to make the prepayment. In the case of the 2006 leases this was when it accepted MAL’s offer and in the case of the latter leases, this was when MFT accepted MAL’s proposal. In particular MAL’s offers for each of the 2006 leases are expressed as offers which MFT first accepted and then chose to make the prepayment. MAL’s proposals for the latter leases were accepted by MFT which then chose to make the prepayments within seven days of executing the lease. In each case if MFT hadn’t made the prepayments it would have been liable to pay a higher percentage rent to MAL;

(2) exclusivity or territorial rights or the offer of any other store. The full licence and lease are to be read together and expressly preclude exclusivity and territorial rights and the offer of any other store;

(3) goodwill, which is the attractive force of a business which brings in custom and is a unified and indivisible item of property. MFT and MAL agreed any goodwill attaching to the store belonged to MAL or the McDonald’s Corporation in the United States (which also owns all of the valuable trademarks and other intellectual property associated with the appearance and operations of McDonald’s Family Restaurants). Like the intellectual property, the goodwill was merely licensed by MAL to MFT and was expressly agreed not to pass to MFT. Further, and in any event, the payments to be made by the lessee do not affect the custom of the business;

(4) the right to operate an existing profitable business. MFT obtained the right to operate a McDonald’s Family Restaurant business in accordance with the McDonald’s System and using the licensed intellectual property by payment of the licence fee, system fee and service fee under the Licence Agreement for each store and paid a separate additional amount for the plant and equipment at the store;

(5) the automatic renewal of the lease. The lease and licence for each store expressly precluded any automatic renewal and, as Mr Mussalli said, MAL sometimes did not renew and sometimes terminated an operator’s licence rather than renewing it or buying it back. MAL gave no assurance of renewal; or

(6) any other asset.

Commissioner’s submissions

Overview

89 The Commissioner submitted that the advantage sought by the trustee of the MFT in making the payments was either to:

(1) secure the right to operate an existing, profitable McDonald’s Family Restaurant business using the McDonald’s System for a term of between 7.83 to 20 years – and possibly longer in light of MAL’s renewals policy – on better terms as to rent; or

(2) obtain an enduring right to occupy the premises on better terms. The right to occupy the premises on better terms under the lease follows from the payment being:

(a) equivalent to a lease premium paid as consideration for the grant of a lease on more favourable terms in respect of the Group One restaurants; or

(b) paid on exercise of an option to modify the lease so that it operated on more favourable terms in respect of the Group Two restaurants.

90 Either way, according to the Commissioner, the payments were on capital account or of a capital nature.

91 The Commissioner submitted that identifying the advantage sought to be obtained in one of the two ways noted above is “consistent with the fact that the upfront amount in respect of each restaurant was paid once and for all at the time the trustee of the MFT acquired the right to operate that particular restaurant”. According to the Commissioner these advantages are evident from the transaction documents considered in isolation and considered in the surrounding circumstances.

Transaction documents

92 The Commissioner observed that when the transaction documents are viewed as a whole it is apparent that the relationship between MAL and MFT was not a conventional landlord-tenant relationship. The Commissioner said:

Rather, clause 1.03 of the lease permitted MFT to use and occupy each of the premises only for a ‘McDonald’s System’ restaurant, with clause 2.01 of the licence granting MFT the right, licence and privilege to adopt and use the ‘McDonald’s System’ in the restaurant subject to the conditions and covenants in the licence – one of which was a condition not to breach any covenant, term or condition contained in the lease.

In so far as the relevant transaction documents comprise both the letters of offer and the FLLs, then it is apparent that all the payments made by the trustee of the MFT at handover were made to acquire the right to operate a pre-existing, profitable McDonald’s restaurant for a term of between 7.83 to 20 years. Mr Mussalli relevantly agreed with the proposition that it was a ‘seamless’ process by which he acquired the already-operating restaurant, where the trustee of the MFT effectively stepped ‘into the shoes of McOpCo’ to continue running the business.

93 The Commissioner submitted that when the FLLs are viewed as a single integrated arrangement it is apparent that the payments are on capital account because they were “calculated to effect the acquisition of the profit-earning structure of the particular restaurant business that MFT intended to carry on”. It is not to the point, said the Commissioner, that MFT could have acquired a similar business structure without making the payments. Viewed objectively, on each occasion MFT made the payment, it did so to be able to operate the business on more favourable terms as to rent, so as to increase the profitability of the business structure. This profitability was to be obtained not through increasing revenue (although, I note, MFT did intend also to increase the revenue of the restaurants it acquired) but by making the business structure that MFT acquired more efficient by securing a reduction in ongoing costs. In the Commissioner’s words, MFT “acquired a more advantageous business structure by paying the upfront amount[s]”.

94 The Commissioner also said, alternatively, that the payments were made in order to secure an enduring right to occupy the premises on better terms. According to the Commissioner:

(1) for the Group One restaurants the payments were made pursuant to the letter of offer and before entry into each FLL and are therefore akin to a lease premium made for the granting of the lease, which is a capital asset, on more favourable terms; and

(2) for the Group Two restaurants the payments were made on exercise of an option to modify the lease so it operated on more favourable terms.

95 The Commissioner referred to the statement in Tucker v Granada Motorway Services Ltd [1979] 2 ALL ER 801 at 811-812 that:

A more relevant test in the present case is to see for what the payment is made. It was made for commuting part of the liability for the additional rent payable under the lease. That fact goes a long way to stamp it with the character of a capital payment, because the lease is, in my opinion, a capital asset of the appellants, as indeed was conceded… The effect of the lump sum payments was to modify the conditions of the lease by reducing the rent payable in future and so to make the lease less burdensome or (what comes to the same thing) more advantageous to the appellants…

96 Accordingly, the Commissioner submitted that based on the transaction documents it is apparent that the payments were lump sums, paid at the start of each transaction, to procure the immediate emergence of a benefit that would endure for a period of between 7.83 and 20 years (depending on the remaining term of the FLL for each store), whether that be through the grant of the lease on better terms or through a variation of the obligation to pay rent by reducing the percentage rent for the remainder of the term. In both cases the effect was to remove or extinguish any obligation to pay the higher percentage rent.

97 The Commissioner said that:

(1) the fact the parties described the payment as prepaid rent does not determine the proper characterisation of the payments: South Australian Battery Makers at 655, Broken Hill at [36] and [76], and Star City at [61]-[63] and [264];

(2) the question is whether a payment described as rent really answers that description: Creer at 59;

(3) ordinarily, rent is on revenue account because it is a recurrent expenditure that accrues periodically in the process of operating a business to secure the ongoing use of the premises;

(4) rent can be pre-paid; and

(5) however, the description “rent” is inapt for a payment made to remove or extinguish an obligation to pay rent. Such a payment cannot be described as a pre-payment of rent because it is not made in respect of a rental obligation that accrued periodically.

98 The Commissioner noted that with one exception (Bateau Bay) the trustee of the MFT was not entitled to a refund of any part of the payments attributable to the unexpired term in the event of early termination of any of the FLLs. According to the Commissioner this militates against the payments being paid in respect of MFT’s right to occupy the premises and suggests that the advantage sought was instead capital in nature.

Surrounding circumstances

99 According to the Commissioner a wider survey of the circumstances surrounding each transaction also supports the characterisation of the payments as being on capital account or capital in nature.

100 First, the Commissioner submitted that the relevant surrounding circumstances are not confined to matters subjectively known by the party making the payment. As the Commissioner put it:

elevating subjective knowledge as a matter to which regard must be had in identifying the advantage sought by a taxpayer and its character could potentially result in the tax characteristics of a payment changing depending on how diligent a taxpayer or their controlling mind was in understanding the transaction that they were electing to enter into.

101 To this end, the Commissioner noted that Mr Mussalli (the sole director of the trustee of the MFT) agreed that a wide range of documents were available to him as both an employee and a franchisee but he did not read them, in effect because he believed he already understood MAL’s policies and procedures given his long experience as an employee of MAL.

102 The Commissioner submitted that Mr Mussalli did in fact demonstrate his familiarity with MAL’s policies and procedures whether or not he had read the documents. According to the Commissioner, Mr Mussalli also demonstrated that he was subjectively aware that the trustee of the MFT would obtain an enduring benefit by making the payments (that is, the lower percentage rent that would be payable for the duration of the FLL and any renewal thereof). The Commissioner noted that Mr Mussalli agreed that Westpac described the purpose of the trustee of the MFT’s facilities accurately in its internal documents when it referred to the “purchase” of the restaurants or providing “funding” for “store acquisition”. The Commissioner pointed to this evidence of Mr Mussalli:

And the purpose is stated to fund purchase of McDonald’s company stores at Gosford West, Wyoming with 20 year franchise agreements and Erina, Erina Fair with approximately 13 year franchise agreements?---Yes.

Was that the purpose you communicated to the bank?---Yes. That was what was in the offer letters.

103 The Commissioner said Mr Mussalli’s description of the funding being to “purchase” the restaurants constituted an admission by Mr Mussalli of the advantage he sought to obtain as the controlling mind of the MFT when making the payments.

104 Second, the Commissioner submitted that the evidence supports the inference that the advantage to be obtained (the lesser percentage rent payable) would endure beyond the initial term of the FLLs and Mr Mussalli knew this to be the case.