Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Limited (No 8) [2019] FCA 593

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 37, subparagraphs (21), (22) and (23) have been deleted, with the content of those subparagraphs (with the exception of “(Ms Nguyen)”, which is deleted) inserted as subparagraphs (19), (20) and (21) to paragraph 38, respectively. | |

24 May 2019 | In subparagraph 38(8), “above” has been replaced with “below”. |

24 May 2019 | In paragraph 96, the first use of the word “Patent” has been replaced with “Trade Mark”. |

24 May 2019 | In paragraph 283, “Kraft also” has been replaced with “Bega”. |

24 May 2019 | In paragraph 288, “Cirparick” has been replaced with “Ciparick”. |

24 May 2019 | In paragraph 313, “adduced by Kraft” has been replaced with “adduced by Bega”. |

24 May 2019 | In paragraph 350, “No” has been replaced with “Yes.” |

24 May 2019 | In subparagraph 528(7), “No” has been replaced with “Yes”. |

ORDERS

First Applicant H.J. HEINZ COMPANY AUSTRALIA LIMITED Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | KRAFT FOODS GROUP BRANDS LLC (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The further hearing of the proceeding, including in relation to the form of orders and declarations to be made in light of these reasons, be fixed on a date to be agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J:

INTRODUCTION

The principal dispute

1 The principal controversy in this case is who owns the “Peanut Butter Trade Dress” currently used by rival entities in conjunction with their respective peanut butter products sold in Australia.

2 “Trade dress” is a term used in United States trade mark law to refer to the appearance of product packaging. See, for example, s 43(a) of the Trademark Act of 1946 (US) (the Lanham Act). Trade dress refers generally to the total image, design, and appearance of a product and may include features such as size, shape, colour, colour combinations, texture or graphics. See, by way of example only, International Jensen, Inc. v. Metrosound U.S.A., Inc., 4 F.3d 819, 822 (9th Cir. 1993). Trade dress is what Australian and English lawyers call “get-up” – which may consist simply of a brand name or a trade description, or the individual features of labelling or packaging under which particular goods or services are offered to the public. See Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc [1990] 1 All ER 873 at 880. It is “the badge of the plaintiff’s goodwill, that which associates the goods with the plaintiff in the mind of the public”. See Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc [1990] 1 All ER 873 at 890.

3 The parties agree that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in issue in this case is “a jar with a yellow lid and a yellow label with a blue or red peanut device, with the jar having a brown appearance when filled”. The parties also agree that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress operates as a trade mark and provides an identifier of relevant goods.

4 Kraft’s case is that it, and only it, is entitled to use the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in conjunction with the Kraft branded peanut butter that the second applicant has manufactured and sold in Australia, in relatively limited quantities, since about April 2018.

5 Examples of Kraft’s product sold before October 2012 are depicted as follows:

(The words “Never Oily, Never Dry” appear under the words “Peanut Butter”.)

6 Examples of Kraft’s product sold from around 2015 until late 2016 are depicted as follows:

(The words “Never Oily, Never Dry” appear under the words “Peanut Butter”.)

7 Examples of the peanut butter product currently manufactured and sold by the second applicant are depicted as follows:

(The words “Loved since 1935 appear under the words “Peanut Butter”.)

8 In June 2017 Kraft began to sell a peanut butter product without the Kraft brand, but using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in conjunction with the words “The Good Nut”, depicted as follows:

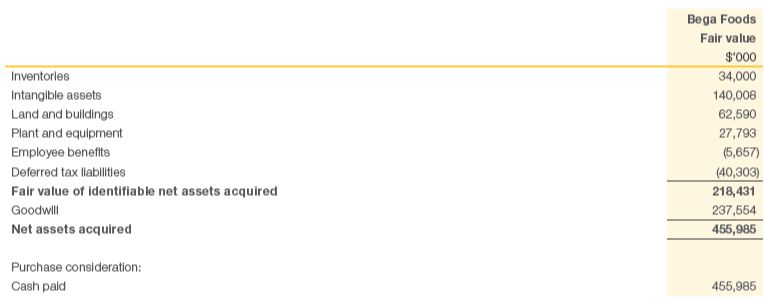

9 In July 2017 Bega Cheese Limited, the respondent, acquired the peanut butter business and the assets and goodwill of Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd. Before 2013 Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd was called Kraft Foods Limited. After the acquisition, Bega commenced selling Bega branded peanut butter product using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in conjunction with the words “The Good Nut”, depicted as follows:

10 Since late 2017, Bega has sold Bega branded peanut butter product using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, depicted as follows:

11 Bega says that it, and only it, is entitled to use the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in conjunction with peanut butter that it has manufactured at what was once the Kraft peanut butter factory in Port Melbourne, Victoria, one of the many assets which Bega acquired as part of its purchase of Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd.

12 In late 2017 Bega ran a series of advertisements on radio and TV that aired for about a month. Those advertisements prompted the applicants to bring the initial iteration of this proceeding, claiming that the advertisements contained false or misleading representations, including that Kraft peanut butter was now Bega peanut butter or was being replaced by Bega peanut butter and that the Kraft brand had changed to or was changing to Bega peanut butter. The advertisements were:

(1) A radio advertisement, broadcast on multiple radio stations nationally as part of regular traffic report segments, in which an announcer says: “Australia’s favourite peanut butter has changed its name. Kraft peanut butter is now Bega peanut butter. Never oily, never dry, with the same taste you’ve always loved, and now is Aussie owned by Bega.”

(2) A television advertisement broadcast on major television networks and digital channels, which shows a jar of Kraft peanut butter, as an announcer says “Australia’s favourite peanut butter has changed its name to Bega peanut butter.” The Kraft label on the jar is then peeled off, revealing the Bega peanut butter label. The announcer continues: “It’s never oily, never dry, with the same taste you’ve always loved, and now Australian owned and made. Bega peanut butter.”

(3) Two variations of television advertisement broadcast on the major television networks in metropolitan markets depicting a worker named “Charlie” taste-testing peanut butter in which an announcer says: “Charlie’s quality tested Australia’s favourite peanut butter here in Port Melbourne for 18 years. Now that it’s owned by Bega, let’s see what’s changed.” “Charlie” then tastes the peanut butter and says “it’s the same”. The announcer then says: “Same recipe, same great taste. Now Aussie owned by Bega”. The Kraft label on the jar is then peeled off to reveal the Bega peanut butter label.

13 On 13 February 2018 the applicants commenced arbitration proceedings before the International Centre for Dispute Resolution in New York. The arbitration was commenced some months after the applicants had commenced a proceeding in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, seeking to compel mediation and arbitration of the dispute between themselves and Bega about ownership of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress. The applicants had also commenced this proceeding, at that stage only in relation to the advertising claims, on 9 November 2017. On Bega’s application, I subsequently ordered that the applicants be restrained from taking any step in the arbitration. See Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Limited (2018) 358 ALR 1; (2018) 130 IPR 434; [2018] FCA 549 and Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 615. The applicants then amended its claim in this proceeding, including by incorporating those claims that it had sought to arbitrate in New York in relation to the Peanut Butter Trade Dress.

14 During the course of the hearing of this proceeding, the parties often, and understandably, referred to “Kraft”, without necessarily distinguishing between the various different companies in the Kraft group. The first applicant, Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC, is incorporated in Delaware, and has its principal place of business in Chicago. Since July 2015 it has been a subsidiary of the Kraft Heinz Company. As I will later explain, in 2012 the company then known as Kraft Foods Inc split itself in two, in a transaction referred to as “the restructure” or the “spin-off”. Those transaction documents referred to the first applicant as “GroceryCo IPCo.” The second applicant, H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited, is an Australian corporation, recently incorporated. It is also a subsidiary of the Kraft Heinz Company. It now manufactures various products, including peanut butter, in Australia.

15 Other Kraft entities which are not parties to this proceeding also play an important role in understanding the disputes that are required to be resolved. Kraft Foods Limited was an Australian subsidiary of Kraft Foods Inc before the restructure. It was renamed Mondelez Australia (Foods) Limited after the restructure. Another Kraft company, confusingly called Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC (confusingly because the first applicant is Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC) was a trade mark licensor. It was referred to as SnackIPCo in the restructure transaction documents, and was renamed Intercontinental Great Brands LLC after the restructure.

16 In these reasons, unless the context otherwise requires it, references to “Kraft” refer collectively to the first and second applicants. I have also chosen not to adopt a policy of the relentlessly consistent use of abbreviations for the various entities and the trade dress otherwise adopted in these reasons, lest the reader become lost in a sea of acronyms.

The competing contentions of the parties about the Peanut Butter Trade Dress summarised

Kraft’s contentions

17 Kraft says that Bega did not acquire the Peanut Butter Trade Dress (which I will also call the PBTD or the trade dress) when it purchased the peanut butter business from Mondelez Australia (Foods) Limited (which I will also call MAFL). Kraft says that the PBTD was never MAFL’s to sell. Kraft’s case is that when Kraft Foods Inc restructured Kraft’s worldwide business in October 2012, Kraft Foods Ltd (which I will also call KFL) had used the PBTD, and the registered trade mark “Kraft”, under license from Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC, which was the intellectual property holding and licensing company for the Kraft corporate group. Kraft says that as mere licensee of the trade dress, KFL did not own the goodwill generated by use of the PBTD or the Kraft mark. Kraft says that KFL could thus not “retain” that goodwill by reason of the restructure, or assign it to Bega, because the goodwill inured to the licensor’s business.

18 Kraft’s next contention is that the restructure, effected in part by a Master Trade Mark Agreement (which I will also call the MTA) operated to assign the PBTD, the Kraft “Primary Brand” (as defined) and the goodwill to the first applicant. Since then, it contends, MAFL only had a licence to use the PBTD (and the Kraft trade mark), which expired on 31 December 2017 – at which point, Kraft contends, Bega, having purchased that licence along with all the other assets, ceased as licensee to have the right to use the PBTD.

19 Kraft also contends that because the production, branding, distribution and sale of Kraft peanut butter in Australia by KFL before the restructure was subject to the ultimate control of the parent company Kraft Foods Inc, (and later, when KFL was renamed MAFL, subject to the ultimate control of Mondelez International Inc), that is another reason that the benefit of the goodwill in the PBTD inured only to the benefit of the first applicant.

20 Kraft emphasises the importance of the Kraft brand. It contends that the Kraft brand has maintained a continuous presence in Australia since the 1930s, and that it did not cease to exist when Bega’s licence to use that brand expired in December 2017. Kraft says that it is the rightful owner of the Kraft brand, and that it was entitled under the MTA to “repatriate” that brand, that is, to participate in the market directly, rather than through a licensee, with Kraft peanut butter packaged in the same way that it was packaged before Bega acquired MAFL’s business and assets, which included the peanut butter business and relevant assets.

21 Kraft contends that the goodwill of the manufacturing business which Bega acquired is a separate concept from the goodwill associated with what it says is Kraft’s intellectual property. Further, relying on the expert evidence of a professor of marketing from the University of Melbourne (Professor Jill Klein), it says that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress is a “diagnostic cue” for the Kraft mark only, and that its use enhances the attractive force (that is, goodwill) only of the Kraft mark, for its owner, the first applicant. It says that, by July 2017, when Bega acquired MAFL, Kraft peanut butter had become well known and recognised by reference to both the Kraft trade mark and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, and that the trade dress indicated trade origin, and provided a shorthand means for the consumer to identify their preferred brand, being Kraft.

22 Kraft further says that once the right to use the Peanut Butter Trade Dress ceased – that is, when the relevant licence expired in December 2017 – the attractive connection between brand and consumer could no longer be a source of goodwill to Bega’s manufacturing operation.

Bega’s contentions

23 Bega says in response that for Kraft’s case to succeed it must prove that before the sale of MAFL’s assets and business to Bega, KFL or MAFL had sold the assets in the Australian peanut butter business, including the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, to either Kraft Foods Inc or Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC, which never happened. Bega submits that under Australian common law, it was not possible for KFL or MAFL so to assign the trade dress because, being an unregistered trade mark, it was an inseparable part of the goodwill of KFL’s business, and could never be assigned without the whole of the relevant (peanut butter) business also being assigned. See Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605; JT International SA v The Commonwealth of Australia (2012) 250 CLR 1; and Commissioner of State Revenue v Placer Dome Inc [2018] HCA 59; (2018) 93 ALJR 65.

24 Bega contends that even if the transaction documents effecting the 2012 restructure had purported to assign the Peanut Butter Trade Dress to another entity in the Kraft group it would have been ineffective as a matter of Australian common law because:

(a) there is no property in an unregistered trade mark per se in Australia; and

(b) assignment of any rights in an unregistered trade mark can only be achieved by assigning the relevant business as a whole, together with the relevant assets.

25 Bega contends, accordingly, that at all times before the sale to Bega, KFL/MAFL owned all the rights in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress as an unregistered trade mark.

26 Bega contends that it also follows that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress never formed, and could never have formed, part of any trade mark that was licensed to KFL under certain licence agreements between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC and KFL, upon which Kraft founds its case.

27 As to Kraft’s contention that, both before and after the 2012 restructure, KFL used the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, and the Kraft mark, under licence from Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC, Bega says that the evidence adduced by Kraft to make good that proposition (namely, copies of various licence agreements subpoenaed from MAFL) is not only irrelevant (because the only way that an unregistered trade mark could have been assigned was by a sale of KFL’s business, which never happened), but, in any event, is insufficient, because it fails to prove that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was in fact ever even purportedly so licensed. Bega submits that Kraft’s case that KFL only ever used the Peanut Butter Trade Dress (and the Kraft mark) by permission, and not as of right, must fail on that ground alone.

28 Bega contends that the Master Trade Mark Agreement, the construction of which is a main limb of Kraft’s case that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was licensed by Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC to KFL, is also of no avail to Kraft because KFL was not a party to it. Bega says that nothing done under the MTA, or effected by it, could change the fact, central to Bega’s case, that KFL/MAFL owned all rights in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress before and after the MTA, and continued to do so up until the time that it sold the Australian peanut butter business to Bega in July 2017. In particular, Bega says that because it was not a party to the MTA, it also follows that KFL could never have assigned any of its property interests to the first applicant. (Kraft’s response to that point is that KFL was not a party to the agreement because it did not have any relevant intellectual property or goodwill.)

29 Bega’s case is that the assets transferred to Bega under the terms of the Sale and Purchase Agreement (which I will also call the SPA) in July 2017 between Bega and MAFL and other Mondelez companies included not only the factory in Port Melbourne, the fixed plant and machinery, the employees, the goodwill, and so on, but also the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, because it formed part of the “Transferred IP Rights” within the meaning of that term as defined, and also because it fell within the description of “[a]ll other property and assets used exclusively for the Joey Business”, within the meaning of Schedule 14 of the SPA. Bega says therefore that it owns all the rights in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress because, by virtue of the SPA, it owns and operates the peanut butter business in which those rights subsist; it can therefore use the trade dress on the peanut butter products it makes and sells as part of its business; and it can enforce those rights against third parties, including Kraft.

30 Bega emphasises that the second applicant, which I will also call H.J. Heinz, is a new entrant into the peanut butter market. It is not a re-incarnation of KFL or any other Kraft company. And it has never made peanut butter until recently. Indeed, uncontroversial evidence adduced at trial showed that it took the second applicant more than a year to develop a “sensory profile” for its product that would taste the same as Bega’s peanut butter. Bega agrees that the second applicant can sell peanut butter products, including with the same sensory profile as Bega’s product. But what it cannot do, on Bega’s case, is to use the Peanut Butter Trade Dress in conjunction with any such product. Bega says that the applicants are liable in damages to it in respect of the sales made by the second applicant.

31 As is apparent from what I have already said, the applicants, on the other hand, insist that they can now do precisely that, and that it is Bega who should be restrained from selling its peanut butter product using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, and that Bega must pay substantial damages to the applicants arising out of Bega’s sales. (The trial of this proceeding was conducted on issues of liability only. Any issues of quantum are to be determined later).

Where things currently stand

32 As things currently stand, only Bega’s peanut butter is available at major supermarkets in Australia, which account for about 80% of the total nationwide annual sales of peanut butter. The major supermarkets have declined to stock the new Kraft peanut butter manufactured by the second applicant, citing the likelihood of consumer confusion. Both products are, however, still available at smaller, independent supermarkets.

33 The stakes are high, because it is common ground that upon Bega entering the market using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, it obtained the whole, or almost the whole, of Kraft’s peanut butter market share, which is worth more than $60 million in annual sales.

The other disputes

34 The parties also counter-sue for misleading and deceptive conduct under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Schedule 2 (the Australian Consumer Law or ACL) and for passing off. Bega contends that the merits of those claims stand or fall on the resolution of the principal issue about ownership of the PBTD, although Kraft says otherwise.

35 Other issues include a claim by Bega against Kraft for breach of copyright, and by Kraft against Bega for what Kraft says was wrongful use by Bega of Kraft “shippers” (cardboard boxes in which peanut butter products are shipped to, and placed on the shelves of, supermarkets), and for breach of contract. The “shippers” case caused the hearing to be interrupted, because on the fourth day of the 12 day trial the applicants applied for, and were subsequently granted, leave to amend their pleadings to include it. See Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Limited (No 6) [2018] FCA 1277. That amendment required an adjournment of the trial because Bega had to file a defence and put on evidence about the new claims.

The affidavit evidence

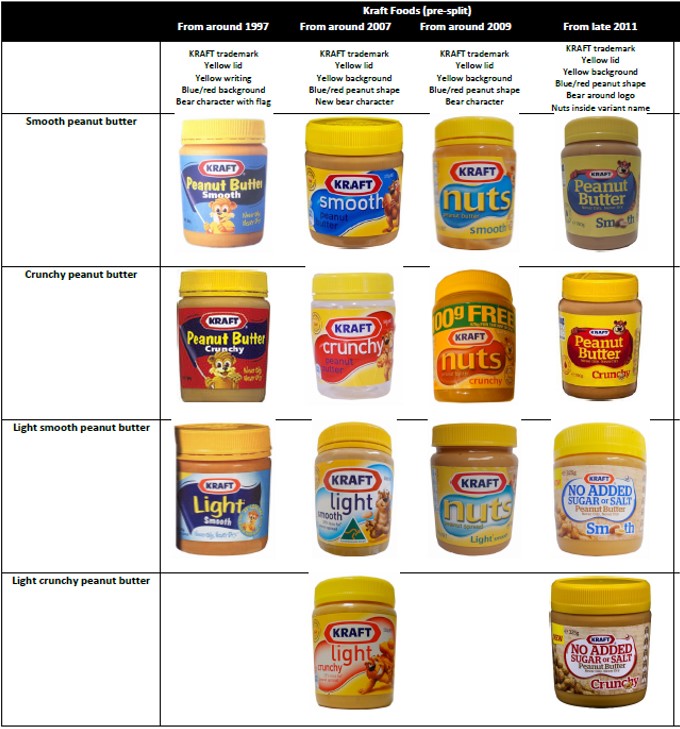

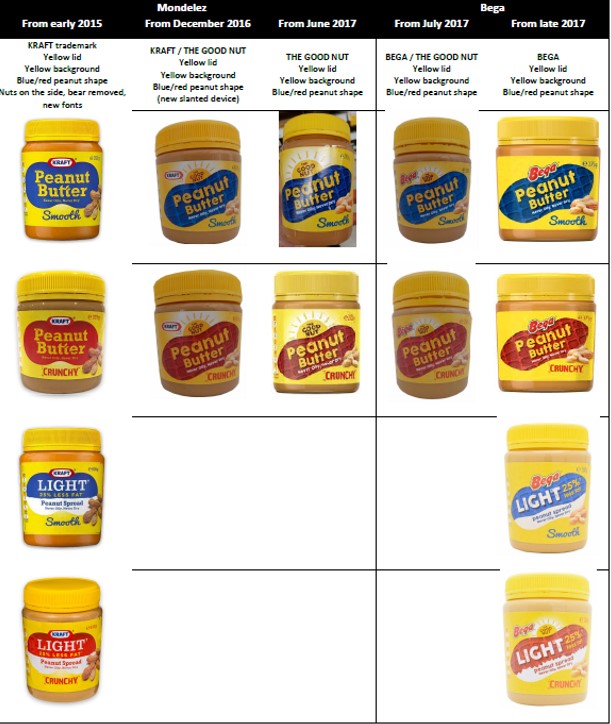

36 During the trial, objections were taken to parts of the affidavit material sought to be relied on by both parties. I ruled on most of those objections during the hearing. The filleted court book redacts inadmissible evidence. In the end, there was very little disagreement about the content of the factual or expert opinion evidence.

37 Kraft relied on the following affidavits:

(1) Affidavit of Bruno Carvalho Lino de Souza, known as Bruno Lino, managing director of the second applicant, sworn 13 June 2018, including in relation to the history of the Kraft Brand in Australia, the “repatriation” of the Kraft brand after December 2017, Bega’s purchase of MAFL, Kraft Heinz peanut butter, developing a sensory profile for Kraft Heinz peanut butter, Bega’s packaging and Bega’s advertising, together with certain confidential correspondence between Bega and Kraft Heinz;

(2) Affidavit of Mr de Souza, sworn 16 July 2018, in relation to sensory profiling tests for Kraft Heinz peanut butter;

(3) Affidavit of David John Rudman, junior counsel in the legal department of HJ Heinz Company Australia Limited, sworn 13 June 2018, in relation to Bega’s advertising;

(4) Affidavit of Mr Rudman, sworn 6 July 2018, exhibiting newspaper articles and advertisements from the mid-1930s about Kraft’s sales of peanut butter in Australia, Bega’s advertising, and the Kraft Heinz peanut butter produced after April 2018, including photographs and the following physical exhibits:

(a) 500g jar of Kraft smooth peanut butter (Ex DJR 16);

(b) 375g jar of Kraft crunchy peanut butter (Ex DJR 17);

(c) 500g jar of Bega smooth peanut butter (Ex DJR 18); and

(d) 375g jar of Bega crunchy peanut butter (Ex DJR 19).

(5) Affidavit of Gabriella Lacerda de Oliveira, graduate in the HR Department at HJ Heinz Company Australia Limited, sworn 12 June 2018, exhibiting a photograph of Bega peanut butter products offered for sale in Kraft shippers at a Woolworths store in Caroline Springs, Victoria;

(6) Affidavit of Georges El-Zoghbi, Strategic Advisor to The Kraft Heinz Company, based in Chicago, Illinois, sworn 12 June 2018, in relation to the global restructure of Kraft Foods Inc and the product quality control exercised by Kraft Foods Inc over KFL;

(7) Affidavit of Jessica Mei Manihera, the Trans-Tasman Marketing Manager of the New Zealand Health Association Limited, trading as Sanitarium Health and Wellbeing Company, affirmed 14 June 2018, in relation to the peanut butter market in Australia;

(8) Affidavit of Jill Gabrielle Klein, Professor of Marketing at Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne, affirmed 11 June 2018, exhibiting expert report in relation to consumer purchasing behaviour, including about product packaging and Bega’s advertising;

(9) Affidavit of Justin Taylor Nel, a Key Account Director of Mintel Group Ltd , a research organisation and market intelligence company, affirmed 12 June 2018, exhibiting records of images of Bega and Kraft peanut butter products (among others) sold in Australia in 2018 contained on the Global New Products Database;

(10) Affidavit of Michael Robert Graif, partner of Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP in New York, sworn 12 June 2018, exhibiting three expert reports about New York law;

(11) Affidavit of Mr Graif, sworn 5 July 2018, exhibiting a fourth expert report about New York law;

(12) Affidavit of Moria Hariza, project manager and “ANZ Kraft Repatriation Lead” at H.J. Heinz, sworn 13 June 2018, in relation to her monitoring of sales of Bega peanut butter products;

(13) Affidavit of Peter Leonard Hallett, solicitor for the applicants, affirmed 14 June 2018, exhibiting a screen shot of a photograph he took of Bega peanut butter being offered for sale in Kraft shippers in a supermarket in South Yarra, Victoria, and correspondence between him and solicitors for Bega in relation to Bega’s advertising;

(14) Affidavit of Mr Hallett, affirmed 20 July 2018, exhibiting a subpoena issued on behalf of the applicants to MAFL to produce certain licence agreements, an affidavit of Mr Syme on behalf of MAFL in relation to the subpoena, and copies of the licence agreements produced pursuant to the subpoena.

(15) Affidavit of Mr Hallett affirmed 23 July 2018, exhibiting solicitor correspondence in relation to the subpoena to MAFL;

(16) Affidavit of Russell Dean Callaghan, the “Food Safety Quality Lead-ANP and Japan” at H.J. Heinz, affirmed 13 June 2018, in relation to quality control issues and a photograph he took of Bega peanut butter being offered for sale in Kraft shippers in a supermarket at Woolworths in Northland, Victoria;

(17) Affidavit of Sabrina Jane Hudson, the Deputy General Counsel for the Kraft Heinz Company and Assistant Secretary for the first applicant, sworn 11 June 2018, exhibiting, among other things, relevant restructure agreements (see above at [9032]).

(18) Affidavit of Ms Hudson sworn 13 June 2018, including an exhibit and a form referred to in one of the spin-off transaction documents;

(19) Affidavit of Ms Hudson sworn 5 July 2018, including an exhibit of a USB stick with copies of the spin-off transaction documents, including all annexures; and

(20) Affidavit of Susan Hanaway Frohling, Counsel at Brinks Gilson & Lione in Chicago, Illinois, and prior to August 2015 the Chief Trademark Counsel at Kraft Foods Inc, affirmed 11 June 2018, in relation to the global restructure, quality control standards, and a Trade Mark Assignment Agreement between KFL and Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC dated 19 April 2012.

38 Bega relied on the following affidavits:

(1) Affidavit of Carmen Brittni Massey, clerk employed by Addisons, Bega’s solicitors, sworn 10 July 2018, exhibiting articles from 1962-1964 editions of a publication called “The Kraftsman”, published by KFL for its employees;

(2) Affidavit of David James Ferguson, solicitor for Bega, sworn 6 July 2018 exhibiting copies, redacted to exclude irrelevant but confidential information, executed by Bega and companies and the Mondelez group of companies, of the following:

(a) Agreement for the Sale and Purchase of the Australia and New Zealand Meals Business of Mondelez International between Mondelez Global LLC, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd, Mondelez Australia Pty Limited and Bega dated 19 January 2017;

(b) Amended Agreement between Mondelez Global LLC, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd, Mondelez Australia Pty Limited and Bega dated 4 July 2017, with, as Schedule, the Agreement for the Sale and Purchase of the Australia and New Zealand Meals Business of Mondelez International between Mondelez Global LLC, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd, Mondelez Australia Pty Limited and Bega dated 19 January 2017, as amended;

(c) Supplemental Agreement in Relation to the Sale and Purchase of the Australia and New Zealand Meals Business of Mondelez International between Intercontinental Great Brands LLC, Mondelez International AMAE Pte Limited, Mondelez International Holdings LLC, Mondelez UK Limited, Mondelez Ireland Limited and Bega dated 4 July 2017;

(d) IP Agreement between Mondelez Global LLC and Bega dated 4 July 2017;

(e) IP Assignment between Intercontinental Great Brands LLC and Bega dated 4 July 2017;

(f) IP Assignment between Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd and Bega dated 4 July 2017;

(g) IP Assignment between Mondelez Australia Pty Limited and Bega dated 4 July 2017;

(h) IP Assignment between Kraft Foods R&D Inc. and Bega dated 4 July 2017; and

(i) IP Assignment between Mondelez International AMAE Pte Limited and Bega dated 4 July 2017.

(3) Affidavit of David Keane, National Business Manager-Independents for Bega Foods, a division of Bega, sworn 12 June 2018, deposing to the sales and promotion of Bega peanut butter in Australia, and exhibiting five television advertisements contained on a USB stick;

(4) Affidavit of Mr Keane sworn 13 June 2018 giving further evidence in relation to the promotion of Bega peanut butter by a sixth television advertisement, contained on a USB stick;

(5) Affidavit of Hayden Samuel Martin, solicitor for Bega, sworn 12 June 2018, deposing to his purchases of Kraft and Bega peanut butter products, and the following physical exhibits:

(a) 780 gram jar of Kraft “Smooth” Peanut Butter (Ex HSM 4);

(b) 780 gram jar of Kraft “Crunchy” Peanut Butter (Ex HSM 5);

(c) 500 gram jar of Bega “Smooth” Peanut Butter (Ex HSM 6);

(d) 500 gram jar of Bega “Crunchy” Peanut Butter (Ex HSM 7); and

(e) 375 gram jar of Kraft “Smooth” Peanut Butter (Ex HSM 10).

(6) Affidavit of Mr Martin sworn 9 July 2018 deposing to an additional purchase of a Kraft peanut butter product and annexing, among other things, a Kraft press release dated 24 October 2017 entitled “Kraft Returns to Australian Stores”, copies of documents filed by Kraft with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and certified copies of corporate records of certain Kraft corporations in the United States;

(7) Affidavit of Mr Martin sworn 16 July 2018, annexing additional Kraft corporate records and filings;

(8) Affidavit of Justine Melissa Munsie, solicitor for Bega, sworn 6 July 2018, deposing to her efforts to contact the four individuals who were authors of the 2012 labels of Mondelez’s Kraft branded peanut butter and who signed “Author Consent and Assignment Deeds” referred to in the affidavit of Ms Nguyen referred to below;

(9) Affidavit of Ms Munsie sworn 13 July 2018 deposing to further attempts to locate those authors;

(10) Affidavit of Leanne Fullagar, a personal assistant employed by Addisons, solicitors for Bega, dated 12 June 2018, deposing to her purchases of Kraft and Bega peanut butter products at supermarket IGA Pennant Hills supermarket in New South Wales, together with copies of photographs of those purchases;

(11) Affidavit of Marino di Camillo, Managing Director and Creative Director of Disegno Group Pty Limited, sworn 10 July 2018, deposing to the fact that Disegno was briefed by Mondelez in February 2014 to refresh the packaging of Kraft branded peanut butter and that the work was undertaken by employees of Disegno, and exhibiting copies of designs produced and an assignment agreement;

(12) Affidavit of Mark Cowan, executive Chairman of Cowan Pty Limited, sworn 19 July 2018, deposing to his involvement with the updating or refreshing of the packaging designs used by Mondelez in 2006, 2007 and 2009, and exhibiting images of the updated designs;

(13) Affidavit of Michael Spiteri, Associate Finance Director of Bega Foods, sworn 12 June 2018 deposing to total retail sales of all peanut butter products in Australia in and in all years since the year ended 30 June 2015, arrived at from data supplied by the company Nielsen;

(14) Affidavit of Mr Spiteri sworn 13 June 2018 deposing to further peanut butter products sales data and Bega’s advertising and consumer promotion costs for the calendar years 2012-2017;

(15) Affidavit of Sandra Dal Maso, Associate Director – Research and Development of Bega Foods, sworn 12 June 2018, deposing to, among other things, the manufacture of peanut butter by Bega, the impact of the Kraft worldwide restructuring in 2012 and quality control audits conducted since 2009;

(16) Affidavit of Matthew Broad, the Supply Planning and External Manufacturing Lead for Bega, sworn 9 October 2018, deposing to facts concerning the “shippers” dispute;

(17) Affidavit of Mr Broad dated 15 October 2018 making minor corrections to his 9 October 2018 affidavit;

(18) Affidavit of Jacqueline Scarlett, Senior Legal Counsel for Bega, sworn 8 October, exhibiting copies of confidential contracts containing the terms and conditions for the supply of peanut butter products by Bega to supermarkets.

(19) Affidavit of Barton Beebe, the John M Desmarais Professor of Intellectual Property Law at the New York University School of Law, sworn 13 July 2018, exhibiting an expert report in relation to the laws of the State of New York on three questions:

(a) Whether it is recognised that the sale and promotion over time of a consumer good in product packaging of a particular appearance (“trade dress”) can result in that trade dress functioning as an indication of origin of that good;

(b) Whether the business owner who sells such goods acquires rights in that trade dress that can be enforced against third parties; and

(c) Whether the business owner who sells such goods can register rights in respect of that trade dress that can be enforced against third parties.

(20) Affidavit of Cam Nguyen, Global Innovation Manager of Treasury Wine Estates, sworn 13 June 2018, in relation to a brief he prepared for Mondelez International’s packaging design agency to create new packaging designs for Kraft branded peanut butter in July 2011; and

(21) Affidavit of Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, a former judge of the New York Court of Appeals, sworn 13 July 2018, exhibiting an expert report on general principles of construction under the laws of the State of New York that apply in construing a written contract.

The pleadings

Kraft’s Third Further Amended Statement of Claim

39 Kraft’s case is pleaded in its Third Further Amended Statement of Claim (the TFASOC). The principal claims (in respect of the PBTD) may be summarised as follows.

40 Kraft alleges that, as of October 2012:

(a) the Kraft Brand and the PBTD were distinctively associated with each other;

(b) the Kraft Brand and the PBTD were well known to the public throughout Australia as denoting and exclusively identifying products of one or more companies within the Kraft Foods Inc group of companies; and

(c) the PBTD signified a connection in the course of trade between peanut butter sold by reference to the Kraft Brand and one or more members of the Kraft Foods Inc group of companies.

41 It is alleged that pursuant to clause 3 of the MTA, the first applicant granted Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC certain licences, including a 10 year licence to use the Kraft brand and the PBTD in Australia in relation to peanut butter (the Mondelez Licence).

42 It is further alleged that, from the date of the restructure, peanut butter was extensively displayed, widely advertised, promoted and sold throughout Australia by MAFL in packaging displaying the Kraft Brand and the PBTD. That conduct, Kraft alleges, was authorised by, and subject to the control of, Kraft, pursuant to the MTA, and that as a result goodwill generated through use of the Kraft brand and the PBTD by MAFL inured to the benefit of the first applicant. It is also alleged that the goodwill inured to the benefit of the first applicant because of the operation of New York law.

43 It is then alleged that by reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 25 to 37, 37A and 37B of the TFASOC, the Mondelez Licence was assigned or novated to Bega, and Bega assumed the obligations to Kraft and restrictions under the MTA in respect of the Mondelez Licence. (Estoppel pleas were also included, but were not mentioned in opening or closing oral submissions).

44 It is then pleaded that:

In the premises of paragraph 14A above and paragraph 25 to 38 above, under New York Law the assignment of the Mondelez Licence (a right governed by New York Law) to Bega carried with it the consequent obligations to Kraft provided under the MTA and Bega assumed the obligations of the Mondelez Parties … in respect of that licence and is bound by those obligations.

45 The next part of the pleading concerns the MTA. The pleaded case in that regard is as follows:

58. By reason of the matters referred to in paragraphs 14A, 17, 18, 25 to 38A and 53 to 57, as between Bega and Kraft:

(a) Kraft is the sole and exclusive owner of the Kraft Brand and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress; and

(b) Bega has no right or interest in the Kraft Brand or the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, and any right on the part of Bega to use the Kraft Brand or the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was coterminous with the Mondelez Licence which expired on 31 December 2017.

59. Further and alternatively, the parties to the MTA agreed that GroceryCo IPCo would own all Trade Dress used for GroceryCo Products and adopted by SnackCo or any of its Affiliates prior to the Distribution Date with respect to any GroceryCo Marks licensed.

PARTICULARS

Clause 2.1(a)(iii) of the MTA

(GroceryCo Products Trade Dress Ownership Clause)

60. The MTA defined GroceryCo Products to mean products, manufactured, advertised, promoted, marketed, distributed or sold in connection with the GroceryCo Business.

61. Peanut Butter was, at the Distribution Date, a product which was manufactured, advertised, promoted, marketed, distributed and sold in connection with the GroceryCo Business.

PARTICULARS

Peanut butter was manufactured, advertised, promoted, marketed, distributed and sold in the United States and Canada by the GroceryCo Business as of the Distribution Date.

62. The Peanut Butter Trade Dress was used in respect of peanut butter which was adopted by SnackCo or its Affiliates prior to the Distribution Date with respect to the Kraft Brand.

63. By reason of the matters referred to in paragraphs 14A, 59 to 62, the parties to the MTA agreed that Kraft owned the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, in consequence whereof Bega has no right to, or (since the expiration of the Mondelez Licence) to the use of, the Peanut Butter Trade Dress.

46 Under the heading “License to SnackCo IPCo under the MTA”, the pleaded case is as follows:

64. Under the MTA Kraft granted SnackCo IPCo an exclusive, fully-paid, royalty-free licence to use:

(a) the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark; and

(b) any logos and Trade Dress owned by a GroceryCo Entity as at the Distribution Date and used in connection with the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark in any product packaging immediately prior to the Distribution Date,

in connection with the production, manufacturing, advertising, promotion, marketing, distribution and sale of peanut butter in Australia and New Zealand.

PARTICULARS

Clause 3.1(a)(v) and Clause 3.1(m) of the MTA

(the Licence Clause)

65. The MTA contained the following definitions for its purposes:

(a) “Kraft Grocery Co Trademark” means the Trademarks “KRAFT” and “KRAFT FOODS” owned by Kraft Foods Inc. or any of its direct or indirect Subsidiaries immediately prior to the Distribution, including the Kraft Hexagon Logo or any successor logo adopted by Grocery Co.

(b) “Kraft Hexagon Logo” means the Trademark owned by Kraft Foods Inc. or any of its direct or indirect Subsidiaries immediately prior to the Distribution that consists of ”Kraft’ bordered with a hexagon as shown below:

66. By reason of the matters referred to in paragraphs 14A, 53 to 65, the parties to the MTA agreed that each of:

(a) the Kraft Brand;

(b) the Kraft Hexago Logo as defined above; and

(c) the Peanut Butter Trade Dress (collectively, the Kraft Licensed Trade Marks);

was subject to the Licence Clause and each fell within the definition of “Licensed Trademark” in the MTA, and further that:

(a) SnackCo IPCo was a “Licensee” within the meaning of the MTA; and

(b) GroceryCo IPCo was a “Licensor” within the meaning of the MTA.

47 The pleading next alleges that Bega was bound by and breached each of the “Discontinuance”, “Transition” and “Inconsistent Action” clauses (among others) of the MTA. I will consider those pleas later in these reasons.

48 The “shippers” plea, the introduction of which caused the delay in the hearing mentioned earlier, and to which I will also return later in these reasons, is as follows:

74A. In connection with its sale of peanut butter without the Kraft Brand but with the Peanut Butter Trade Dress from July 2017, until about April 2018, Bega sold and distributed peanut butter in the Impugned Bega Packaging and Bega packaged jars of peanut butter in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress absent the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark, and distributed them to retailers in outer cardboard containers (“shippers”) for holding and display which bore the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark.

PARTICULARS

The periods within which such shippers were supplied to retailers in respect of Stock Keeping Units relating to peanut butter are set out in the table at paragraph 9 of the Affidavit of Matthew Broad herein sworn 19 July 2018. Such shippers were displayed to the public, and continued to be displayed to the public for approximately 21 days after the dates of final dispatch appearing in the table.

74B. The conduct of Bega referred to in paragraph 74A was not authorised under the MTA or otherwise authorised by the Applicants and infringed the rights of the first Applicant in Australian trade mark registrations numbered 156444 and 181518 under section 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 because the contents of the shippers were not finished goods bearing the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark.

PARTICULARS

MTA clause 3.5(a)

Bega’s defence and cross-claim

49 As would be apparent from the earlier summary of the disputes in these reasons, Bega denies all of the material allegations against it. See Defence to Third Further Amended Statement of Claim dated 14 September 2018 (Defence). It is helpful to set out some of the admissions and positive averments that it made in its original defence dated 4 December 2017, and contained in the Defence, in part because they prompted a reply pleading from Kraft that helped to crystallise the issues.

50 Bega admits that prior to October 2012, KFL manufactured peanut butter products in Australia and that, prior to October 2012, KFL promoted and sold peanut butter products by reference to the Kraft Brand and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress, and refers to [100] of the Defence, which is as follows:

Promotion of the peanut butter products before 2012

100. Prior to the Restructure, Kraft Foods Limited:

(a) manufactured the peanut butter products that it supplied in Australia from manufacturing facilities located in Port Melbourne, Melbourne (Port Melbourne Factory);

(b) employed the technical and production staff with the know-how to make the peanut butter product in the Port Melbourne Factory to its particular recipe and specifications;

(c) promoted and sold its peanut butter products under and by reference to:

(i) its Australian Trade Mark Registration Nos 156444 and 181518 for KRAFT in class 29 for ‘peanut butter’ (Registered Kraft Trade Marks); and

(ii) its Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 778978 for NEVER OILY NEVER DRY in class 29 for ‘peanut butter’; and

(iii) its packaging and get up, including the yellow lid, clear container, and predominantly yellow label;

(d) generated goodwill in relation to its peanut butter products that was associated with each of:

(i) its Registered Kraft Trade Marks;

(ii) its NEVER OILY NEVER DRY trade mark; and

(iii) its packaging and get up.

51 At [18] it pleads that:

18. As to paragraph 18 it says as follows:

(a). It admits that pursuant to the MTA, Kraft Foods granted Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC a 10 year licence to use the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark (as described in paragraph 64(c) below) in relation to peanut butter in Australia;

(b) It will refer to the MTA at trial for its full terms and effect;

(c) It otherwise denies paragraph 18; and

(d) It says further that:

(i) the goodwill in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was owned and used prior to the Restructure by an Affiliate of SnackCo IPCo (Kraft Foods Limited) in relation to a SnackCo Business (as defined in the Separation Agreement);

(ii) there was no allocation of that goodwill to Kraft Foods in the Separation Agreement or the MTA;

(iii) there was in any event no assignment of that goodwill by Kraft Foods Limited to Kraft Foods in the Separation Agreement, the MTA or otherwise; and

(iv) the licence under clause 3.1(a) of the MTA did not relate to the Peanut Butter Trade Dress.

52 An important part of Bega’s positive case appears under the heading “Promotion of the peanut butter products following the Restructure” at [101] ff, as follows:

101. Following the Restructure, Kraft Foods Limited was renamed Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd.

102. Following the Restructure, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd:

(a) continued to manufacture the peanut butter products that it supplied in Australia from the same manufacturing facilities at the Port Melbourne Factory, and using the same know-how, recipe and specifications; and

(b) continued to promote and sell its peanut butter products under and by reference to:

(i) the Registered Kraft Trade Marks;

(ii) its Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 778978 for NEVER OILY NEVER DRY; and

(iii) its packaging and get up, including the yellow lid, clear container, and predominantly yellow label.

103. As part of the Restructure, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd assigned its rights in its Australian Trade Mark Registration Nos 156444 and 181518 for KRAFT to Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC, which later assigned its rights in those trade marks to Kraft Foods.

104. Following the Restructure, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd was permitted by the assignees of the Kraft trade mark registrations to continue to promote and sell its peanut butter products under and by reference to the Registered Kraft Trade Marks on a royalty-free basis.

105. Pursuant to the Restructure agreements, the ‘Licensee’ was permitted to transition from any use of the Registered Kraft Trade Marks to a new trade mark for continued sales of its peanut butter products.

Particulars

Clause 3.5(b) of the MTA.

106. In about December 2016 Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd:

(a) commenced transitioning from using the Registered Kraft Trade Marks on its peanut butter products to using the THE GOOD NUT trade mark;

(b) continued to promote and sell its peanut butter products under and by reference to:

(i) its Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 778978 for NEVER OILY NEVER DRY; and

(ii) its packaging and get up, including the yellow lid, clear container, and predominantly yellow label.

107. On about 4 July 2017 Bega acquired Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd’s peanut butter business in Australia, including:

(a) the manufacturing facilities located at the Port Melbourne Factory; and

(b) all of Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd’s goodwill associated with its peanut butter products business.

Particulars

(i) Pursuant to the terms of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.

(ii) See in particular clauses 2.1, 6.2 and Schedule 5, Part A, clause 1.2.

108. Since 4 July 2017 Bega has continued to manufacture the same peanut butter products that were formerly manufactured by Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd (formerly Kraft Foods Limited), from the same manufacturing facilities located at the Port Melbourne Factory, and using the same know-how, recipe and specifications.

109. On about 4 July 2017 Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd assigned its rights in Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 778978 for NEVER OILY NEVER DRY to Bega.

110. Since about July 2017, Bega has:

(a) transitioned from using THE GOOD NUT trade mark to using its BEGA trade mark for its peanut butter products;

(b) continued to promote and sell its peanut butter products under and by reference to:

(i) its Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 778978 for NEVER OILY NEVER DRY; and

(ii) its packaging and get up, including the yellow lid, clear container, and predominantly yellow label.

111. Since about October 2012 Kraft Foods has not:

(a) exercised quality control in respect of the peanut butter products sold in Australia by:

(i) Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd; or

(ii) Bega; or

(b) had any other involvement in the manufacture and promotion of the peanut butter products sold in Australia by:

(i) Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd; or

(ii) Bega.

112. By reason of the matters alleged above, Kraft Foods does not own any of the goodwill in Australia generated in respect of the sale of peanut butter products in Australia since about October 2012, including in respect of:

(a) sales made by reference to the Registered Kraft Trade Marks;

(b) sales made by reference to the NEVER OILY NEVER DRY trade mark; and

(c) sales made by reference to the packaging and get up, including the yellow lid, clear container, and predominantly yellow label.

Kraft’s Reply

53 Kraft replied (see Reply to Defence to Second Further Amended Statement of Claim dated 4 July 2018) relevantly as follows:

Prior to the Restructure

2. As to paragraph 11 [of the Defence], the Applicants … say as follows:

(a) any such promotion and sale by reference to the Kraft Brand and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress prior to October 2012 was made pursuant to licence agreements with Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC or prior to 4 August 2008 Kraft Foods Holdings, Inc which merged into Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC on that date;

(b) Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC was at all material times prior to October 2012 the intellectual property holding company for the Kraft Foods Inc. group of companies; and

(c) …

PARTICULARS

The Applicants rely on the following license agreements produced by Mondelez Foods (Australia) Inc. (formerly Kraft Foods Limited) in response [to] the subpoena dated 1 June 2018.

(i) Agreement between Kraft Foods Holdings, Inc and Kraft Foods Limited dated 1 January 2000

(ii) Agreement between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC and Kraft Foods Limited dated 1 January 2009

(iii) Agreement between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC and Kraft Foods Limited dated 29 December 2010.

3. As to paragraph 18 of the Defence they deny the positive allegations made therein and say further that:

(a) the licence was not limited to use of the Kraft GroceryCo Trademark; and

(b) goodwill in the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was not owned by Kraft Foods Limited in the circumstances pleaded in paragraph 2 above and, after 2012, goodwill did not inure to it in circumstances where that use was pursuant to the MTA; and

(c) the allocation of goodwill is otherwise irrelevant in circumstances where Bega is bound by the contractual obligations imposed by the Mondelez Licence as pleaded in the [TFASOC].

54 In its Reply to [103], Kraft admits the allegations in that paragraph “and say[s] further that Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd only held bare legal title to Australian Trade Mark Registration Nos 156444 and 181518” (the word “Kraft” and the Kraft hexagon logo, respectively (see [65] and [67] below)). As to [105], Kraft “say[s] further that the Mondelez Licence required Bega to cease use of the Kraft Trade Mark and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress and not to challenge the ownership of goodwill in the same”. As to [107], Kraft admits that Bega acquired the Port Melbourne Factory, but otherwise denies the allegations, including the allegation that there was goodwill in respect of the place of manufacture of the peanut butter. As to [111], Kraft says that any use of goodwill generated in the Kraft trade mark and Peanut Butter Trade Dress by Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd since October 2012 did not vest in that entity but inured to others and, as a consequence, could not be transferred to Bega.

Bega’s cross-claim

55 Bega also relies on an Amended Notice of Cross-Claim dated 18 May 2018. Most of it concerns, in substance, Bega’s claim that it, not Kraft, is the party entitled to use the Peanut Butter Trade Dress. Bega also makes claims against Kraft for breach of copyright, an ACL claim about a Kraft press release and a Kraft Heinz promotional slogan, but it is not necessary to set out those claims in detail now. I will return to them later.

Issues to be decided agreed by the parties

56 Before counsel commenced their oral closing submissions, I caused an email to be sent to the parties’ legal representatives asking that counsel confer and agree upon a list of the specific issues necessary for decision, and the order in which those issues were to be dealt with in closing addresses. The response was a list of 18 “Agreed general order of issues”. The parties agreed that the principal issue about the ownership of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress was to be resolved by addressing six inter-related issues which arise from their respective pleaded cases:

(1) What is goodwill and what is the legal nature of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress as an unregistered trade mark?

(2) What did/does the Peanut Butter Trade Dress designate to consumers?

(3) How does goodwill inure to an entity?

(4) How is an unregistered trade mark in Australia assigned or transferred?

(5) To whom did relevant goodwill generated in respect of peanut butter branded Kraft and bearing the Peanut Butter Trade Dress inure immediately prior to the date of the restructure?

(6) To whom did relevant goodwill generated in respect of peanut butter branded Kraft and bearing the Peanut Butter Trade Dress inure after the date of the restructure?

57 The parties agreed that the other issues involve answering the following additional questions:

(7) Can the ACL and passing off issues in the case be determined without ascertaining whether rights in respect of trade dress accrued to the first applicant under the MTA?

(8) Does the Mondelez Licence (as defined in [18] of the TFASOC) preclude Bega from claiming “ownership” of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress?

(9) Has Bega breached any term(s) of the MTA that it is bound by in respect of its use of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress from 1 January 2018?

(10) What is the proper interpretation of the MTA? Did the MTA affect rights in respect of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress?

(11) Has Bega breached the ACL by using the Peanut Butter Trade Dress because of any association that it has with the Kraft brand?

(12) Did Bega breach the ACL by its television/radio advertisements in November 2017?

(13) Did Bega engage in passing off or misleading and deceptive conduct through use of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress?

(14) What rights were acquired by Bega in July 2017 in respect of peanut butter?

(15) Did Kraft breach the ACL by its release of a press release of October 2017, or use of the slogan “Loved since 1935”?

(16) Did Kraft engage in misleading and deceptive conduct or passing off though use of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress?

(17) Did Bega own, and did Kraft infringe, copyright in respect of the 2012 or 2015 labels?

(18) Was Bega’s use of the Kraft shippers unlawful?

58 After the hearing had finished, at my request, the parties filed a document entitled “Table Cross-Referencing the ‘Parties Agreed General Order of Issues’ to the Pleadings”. It is attached as Annexure A to these reasons. An email was sent to my chambers in respect of that document, which said that “[t]he contents of the document are agreed, save that [Kraft] contend[s] that paragraphs [74A], [74B] and [84A] of the Claim and the Defence are relevant to issues 9, 11 and 13 (which the document as filed reflects), while [Bega] contends that those paragraphs are not relevant to issues 9, 11 and 13 and are only relevant to issue 18 (the shippers case)”. It is not necessary to resolve that disagreement. The parties agreed that the 18 questions covered the field of disputation, whatever their precise relationship to the pleadings, and I will decide them accordingly.

59 Some of the issues are more conveniently dealt with together, and in a slightly different order, as will become apparent.

OUTLINE OF THE FACTS

60 It will shortly be necessary to set out in detail the relevant facts, concerning, among other matters, the relevant history of Kraft’s peanut butter business in Australia, Kraft’s 2012 corporate restructuring, the sale of the business by Kraft Foods Limited (by then renamed Mondelez (Australia) Foods Limited) to Bega in 2017, and the events that ensued after the sale.

61 It is helpful, before turning to that detail, to set out a brief overview of largely uncontroversial matters, in order to provide context to the discussion that will later appear about the meaning and legal effect of the critical parts of the transaction documents, and the relevance of the evidence adduced by the parties.

The history of Kraft peanut butter sales in Australia

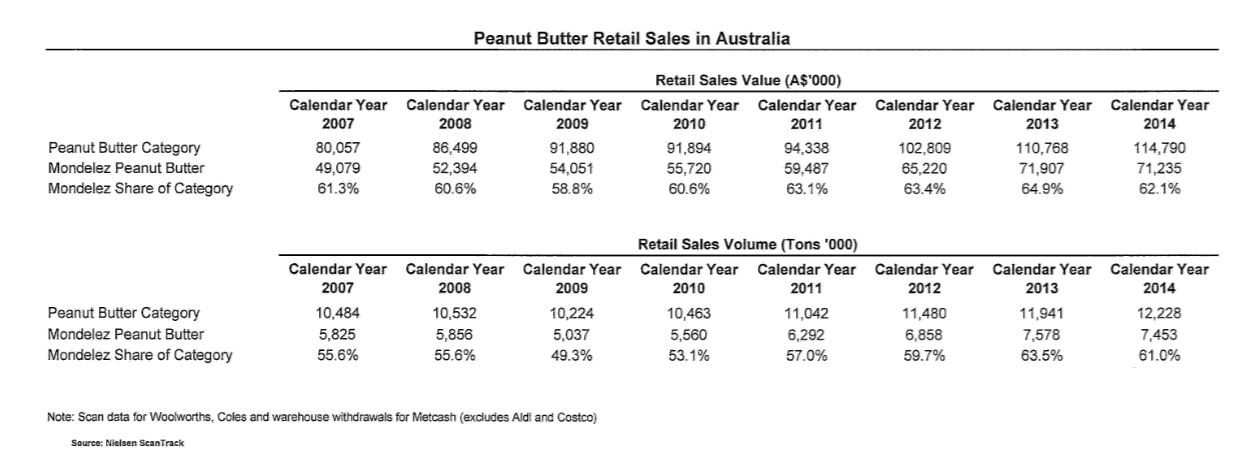

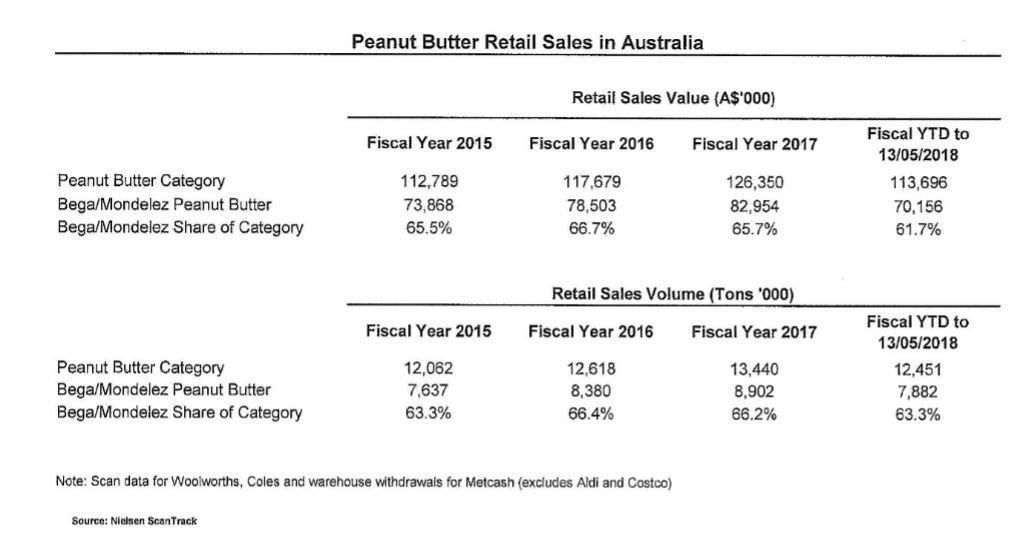

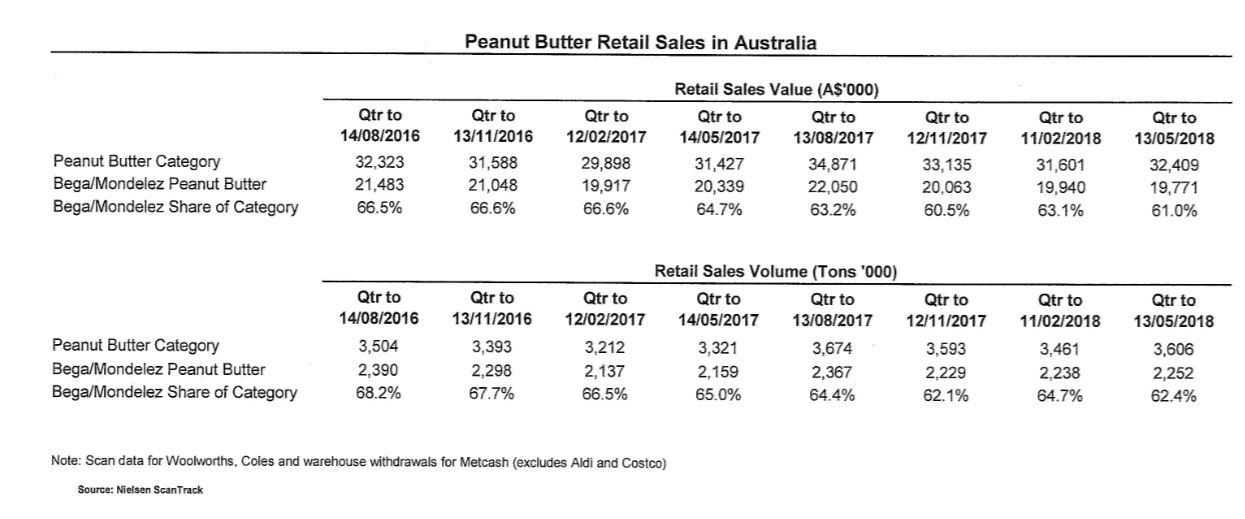

62 Kraft is one of the world’s best-known and valuable grocery brands, estimated in May 2018 to be worth US$8.8 billion world-wide. For many years before Bega acquired the assets and business of MAFL in 2017, Kraft had by far the largest market share of peanut butter products in Australia. By 2017, the Australian peanut butter market was worth $110 million in annual sales. Kraft’s market share was approximately 65% by value and volume.

63 Kraft Walker Cheese Company Proprietary Limited was first incorporated in Australia in 1926. That company was renamed Kraft Foods Limited in 1951.

64 “Kraft Peanut Butter” has been available for purchase in Australia since 1935.

65 The word “Kraft” was registered as a trade mark in Australia for use in a class of goods, including peanut butter products in the name of KFL in October 1959.

66 In 1962, KFL established a factory at Port Melbourne, in Victoria, to manufacture peanut butter (and other products).

67 In 1963 KFL registered the following “Kraft” hexagon logo as a trade mark in Australia for use in a class of goods, including peanut butter products:

68 Commencing in the 1980s, KFL promoted its peanut butter products by television advertisements featuring the “Never Oily, Never Dry” expression. The script of those versions are annexed to these reasons as Annexure B.

69 On 4 July 2001, KFL registered the words “Never Oily, Never Dry” as a trade mark in Australia for use on a class of goods of peanut butter products. Two of the expressly agreed facts between the parties are as follows:

3 Australian Trademark Registration No. 778978 is a trade mark registration for the words ‘NEVER OILY NEVER DRY’, registered in Class 29 for ‘peanut butter’ from 20 November 1998.

4 Australian Trademark Registration No. 778978 was or has been registered in the name of:

a) Kraft Foods Ltd until about 9 October 2013;

b) Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd from about 9 October 2013 until about 21 September 2017; and

c) Bega Cheese Limited from about 21 September 2017.

70 In the early 1990s, Kraft peanut butter first became available in Australia in a jar with yellow lid.

71 Since around 1997 the packaging of Kraft peanut butter has involved the use of a clear jar with a yellow lid with the Kraft hexagon logo presented centrally on its label. Since 2007, the yellow lid has comprised the same yellow with a label comprising a blue or red peanut device, the jar having a brown appearance when filled. The Peanut Butter Trade Dress, therefore, has been used since 2007.

72 On 1 January 2000, KFL entered into a licence agreement with Kraft Foods Holdings Inc, a Delaware corporation. By the terms of that licence agreement, KFL was granted a licence to use, advertise and display the “Subject Trade Marks”, in Australia and in any country to which it exported licensed products (“the Territory”). “Subject Trade Marks” were defined to mean:

(i) all trade marks beneficially owned in the Territory by Licensor from time to time;

(ii) trade marks that are registered in the name of Licensor or the subject of pending applications …;

(iii) trade marks adopted in the Territory by the Licensor after the date of this Agreement …

73 The licence agreement further provided for the payment of royalties by KFL (see clause III.A). Clause IV was entitled “Control”, and reads as follows:

To protect and enhance the value of the goodwill symbolized by the Subject Trade Marks, and to ensure that the public may continue to rely upon the Subject Trade Marks as identifying Products and Services of consistent high quality, Licensee agrees that it will use the Subject Trade Marks under the strict control of the Licensor as to the character and/or quality of all Products and Services associated with the Subject Trade Marks. More particularly, Licensee agrees that it will manufacture and package the Products distributed, sold, or offered for sale by it in association with the Subject Trade Marks in accordance with the Licensor’s specifications, recipes, formulas, procedures, quality control, marketing and other standards, policies, and guidelines. Licensor has the right to approve any packaging or advertising used or proposed to be used by Licensee.

74 The 1 January 2000 license agreement was later amended and restated by an agreement dated 1 January 2009, and again by a second such agreement dated 1 January 2011, but the applicable provisions of those agreement are not relevantly different.

75 By 2007 KFL was making, promoting and selling peanut butter products in Australia applying four trade marks:

(i) the registered trade mark of the word “Kraft”;

(ii) the registered trade mark of the Kraft hexagon logo;

(iii) the registered trade mark of the words “Never Oily, Never Dry”;

(iv) the (unregistered) Peanut Butter Trade Dress.

76 In April 2009 Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC filed (and subsequently registered) Australian Trade Mark No. 1294171 for the logo appearing on peanut butter in Australia (defined in the TFASOC as a KFG Mark), depicted as follows:

77 In August 2009, Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC filed Australian Trade Marks Nos. 1317816 and 1317815 (which were subsequently registered). The logo in Australian Trade Mark No. 1317816 is the bear shown on the top right-hand corner of this device, depicted as follows:

78 It is common ground that the rights in each of the registered trade marks Kraft and the Kraft hexagon logo were registered in KFL’s name until 2012. It is also common ground that in April 2012 those marks were assigned to Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC.

79 Kraft contends, and Bega denies, that Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC was at all material times prior to the assignment the beneficial owner of the Kraft trade mark and the Kraft hexagon logo, and that KFL/MAFL only ever held bare legal title to those marks.

80 It is common ground that KFL/MAFL was at all material times the legal and beneficial owner of the registered trade mark being the words “NEVER OILY, NEVER DRY” and that Bega acquired the mark when it acquired the business and assets of MAFL in 2017.

81 It is also common ground that the registered trade marks of the word “Kraft” and the Kraft hexagon logo were agreed to be assigned from Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC to Kraft Foods Group Brands and that the assignments were effected by a Deed of Assignment dated 21 November 2012, expressed to have been effective on 29 September 2012.

82 It follows that by the beginning of October 2012, KFL continued to produce, promote and sell Kraft peanut butter and applying three trade marks in its name, and one unregistered mark (the Peanut Butter Trade Dress).

83 After the global restructuring in 2012, MAFL continued its business of making, promoting and selling peanut butter product in Australia, which included the application of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress to them.

84 The parties agreed that Exhibit A1, which was tendered by the applicants, accurately depicts each of the different Kraft peanut butter products sold by KFL/MAFL in Australia between 1997 and July 2017. It also shows, as the parties agreed, the Bega peanut butter products sold in Australia since late 2017 to date. Exhibit A1 is attached to these reasons as Annexure C. The colours, in particular the colours of the yellow lids, are not uniform. That is the fault of the photography. The actual colour yellow, which is accurately enough depicted in the examples in [5] above, has remained unchanged at all relevant times. As mentioned earlier, physical exhibits of some of those products currently sold by Kraft Heinz and by Bega since 2017 were also part of the evidence.

85 By 2017, Kraft peanut butter comprised approximately 60% by value and 55% by volume of total Australian peanut butter retail sales.

Summary of the spin-off of Kraft Foods Inc

86 On 4 August 2011 the board of directors of Kraft Foods Inc, the parent entity and ultimate controller of companies operating the Kraft Foods business globally, announced that it intended by October 2012 to create two independent public companies: a global snacks business and a North American grocery business. It was called a “proposed spin-off transaction”. In its Form 10-Q filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Kraft described the proposed transaction in these terms, which the parties to this proceeding agreed is a useful summary of the purpose and effect of it:

On August 4, 2011, we announced that our Board of Directors intends to create two independent public companies: (i) a global snacks business (the “Global Snacks Business”) and (ii) a North American grocery business (the “North American Grocery Business”). We expect to create these companies through a spin-off of the North American Grocery Business to our shareholders (“Spin-Off’). Following the Spin-Off, we will hold the Global Snacks Business and change our name to Mondelez International, Inc. (“Mondelez”). Mondelez will primarily consist of our current Kraft Foods Europe and Developing Markets segments as well as our North American snack and confectionery businesses and related categories in our Canada & N.A. Foodservice segment. Our subsidiary, Kraft Foods Group, Inc. (“Kraft Foods Group”) will hold the North American Grocery Business, which will primarily consist of our current U.S. Beverages, U.S. Cheese, U.S. Convenient Meals and U.S. Grocery segments, grocery-related categories in our Canada & N.A. Foodservice segment as well as the Planters and Corn Nuts brands and businesses. We have received a private letter ruling from the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) confirming that, based on certain representations, assumptions and undertakings, the Spin-Off will be tax-free to our U.S. shareholders for U.S. federal income tax purposes.

87 In October 2011, Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC filed for and subsequently registered a trade mark for the following logos in respect of peanut butter:

88 On 19 April 2012, KFL entered into a trade mark assignment agreement with Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC (which changed its name to Intercontinental Great Brands LLC in May 2013). That agreement included an assignment of the Kraft word trade mark and the hexagon logo trade mark.

89 Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC was incorporated on 1 June 2012.

90 As part of the spin-off transaction, four agreements which are relevant for present purposes were entered into, viz:

(1) a Separation and Distribution Agreement between Kraft Foods Inc. (SnackCo) and Kraft Foods Group, Inc. (GroceryCo) entered into on 27 September 2012 (the Separation Agreement);

(2) a Master Ownership and License Agreement Regarding Trademarks and Related Intellectual Property between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC (SnackCo IPCo) and the first applicant (GroceryCo IPCo) dated 27 September 2012 (the MTA);

(3) a Master Ownership and License Agreement Regarding Patents, Trade Secrets and Related Intellectual Property between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC (SnackCo IPCo), the first applicant (GroceryCo IPCo), Kraft Foods UK Ltd, and Kraft Foods R&D Inc. dated 27 September 2012 (the Master Patent Agreement); and

(4) a Trademark Assignment between Kraft Foods Global Brands LLC (the company that became Intercontinental Great Brands LLC) and the first applicant dated 29 September 2012, including the assignment of the “Kraft” word and hexagon trademark registrations in Australia, which states “together with the goodwill of the business symbolized thereby and associated therewith”.

91 On 1 October 2012 Kraft Foods Inc changed its name to Mondelez International, Inc.

92 In July 2015 Kraft Food Group, Inc merged with H.J. Heinz Company in the United States to form the Kraft Heinz Company.

Bega acquired Kraft Foods Ltd in July 2017

93 On 19 January 2017, Mondelez Global LLC, Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd, Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd and Bega entered into a Sale and Purchase Agreement of what the agreement called “the Joey Business” of the Mondelez Group (essentially, the business and assets of MAFL). The agreement was subsequently amended. The amended agreement that governed the transaction is dated 4 July 2017 (the SPA). The closing of the transaction under the SPA also took place on 4 July 2017. In the SPA, Mondelez Global LLC was defined as “MDLZ”; Mondelez Australia (Foods) Ltd (MAFL) was defined as “MDLZ Australia Foods”; Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd was defined as “Mondelez Australia Pty”; and Bega Cheese Limited was defined as “the Buyer”. I will return to the relevant provisions of the SPA later.

94 On the day of the closing, Bega also entered into a “Supplemental Agreement in Relation to the Sale and Purchase of the Australia and New Zealand Meals Business of Mondelez International” with Intercontinental Great Brands LLC, Mondelez International AMEA Pte Limited, Mondelez International Holdings LLC, Mondelez UK Limited and Mondelez Ireland Limited. Clause 6.4 of that agreement provides as follows:

Each MDLZ Party and the Buyer hereby acknowledges that certain of the Business IP is subject to the KFG Master Trademark Agreement or the KFG Master Patent Agreement. Any transfer of Business IP subject to, and of any related rights under, the KFG Master Trademark Agreement and the KFG Master Patent Agreement, is made on the basis that any Buyer Group Company which is a transferee of any such Business IP and related rights expressly assumes in writing all the obligations of the relevant transferor under the KFG Master Trademark Agreement and KFG Master Patent Agreement with respect to such transferred Business IP and related rights, and acknowledges KFG as the intended beneficiary of those obligations.

95 KFG is defined in that agreement to mean “Kraft Foods Group, Inc and its Affiliates”.

96 The KFG Master Trade Mark Agreement and KFG Master Patent Agreement are defined to mean the MTA and Master Patent Agreement as defined in [90] above.

ISSUES 1 – 6

Introduction

97 The first four issues posed by the parties (set out at [56] above) in relation to the question of ownership of the Peanut Butter Trade Dress on their face go to questions of legal principle. The fifth and sixth questions, on the other hand, more distinctly raise issues that turn in part on facts, and require conclusory answers in addition to discursive reasons. All of the first six issues are interrelated, and all of them involve factual and legal questions which are not always easily separated. It follows that the issues overlap, and involve mixed questions of fact and law. It also follows that a degree of repetition is unavoidable.

Issue 1: What is goodwill and what is the legal nature of the PBTD as an unregistered trade mark?

Unregistered trade marks

98 The parties agreed that the Peanut Butter Trade Dress is an unregistered trade mark.

99 Using a mark as a trade mark is to use the mark as a “badge of origin”, in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods. That concept is embodied in the definition of “trade mark” in s 17 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), which provides: “A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person”. See E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 at 163 (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ).

Goodwill and the Peanut Butter Trade Dress

100 Rights associated with trade dress, or get-up as it is called in this country, are rights to protect goodwill (by a passing off action and also, nowadays, by an action brought under s 18 of the ACL). As French CJ explained in JT International SA v The Commonwealth of Australia (2012) 250 CLR 1 at 33, [40]:

It has rightly been said that “[t]here is no ‘property’ in the accepted sense of the word in a get-up” [citing Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc [1990] 1 WLR 491 at 505 per Lord Oliver of Aylmerton]. The rights associated with a particular get-up, which may also be viewed as a species of common law trade mark, are the rights to protect goodwill by passing off actions or the statutory cause of action for misleading or deceptive conduct where another has made unauthorised use of the get-up in a way which satisfies the relevant criteria for liability. The get-up rights asserted by [the plaintiffs] and the other non-statutory rights are, like their statutory equivalents, exclusive rights which are negative in character and support protective actions against the invasion of goodwill.

101 Further, as Kiefel J (as the Chief Justice then was) explained in that same case at 125, [348]:

Strictly speaking, the right subsisting in the owner of a trade mark is a negative and not a positive right. It is to be understood as a right to exclude others from using the mark [citing Henry Clay & Bock & Co Ltd v Eddy (1915) 19 CLR 641 at 655 per Isaacs J; Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 74-75] and cannot be viewed as separate from the trade in connection with which it is used. It is for the protection of that trade in goods that property is recognised in a trade mark [citing Henry Clay & Bock & Co Ltd v Eddy (1915) 19 CLR 641 at 655].

102 And as Gummow J explained in ConAgra Inc v McCain Foods (Aust) Pty Ltd (1992) 33 FCR 302 at 366, the nature of the right sought to be vindicated in a passing-off action is a right of property:

What is of significance for present purposes is the statement by Lord Parker in Spalding’s case [A G Spalding & Bros v A W Gamage Ltd (1915) 32 RPC 273] (at 284) that if the nature of the right, the invasion of which is the subject of passing-off actions, is a right of property, what is referred to is ‘property in the business or goodwill likely to be injured by the misrepresentation’. In Norman Kark Publications Ltd v Odhams Press Ltd [1962] 1 WLR 380 at 383; [1962] 1 All ER 636 at 639, Wilberforce J said:

The basis of the action, as shown in Spalding v Gamage is a proprietary right, not so much in the name itself, but in the goodwill established through use of the name in connection with the plaintiff’s goods. I draw, of course, from Lord Parker of Waddington’s well known opinion in that case. The plaintiff must show that the name has become distinctive of his goods, and that a reputation has attached to them under the name in question, and that use by the defendant of the name is likely to cause confusion resulting in damage to the goodwill of the plaintiff.

The notion of a trade mark, in the common law sense, is now wide enough to encompass slogans and visual images which radio and television or other means of advertising leads the market to associate with the goods or business of the plaintiff. The Privy Council so declared in Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Pub Squash Co Pty Ltd [1981] RPC 429 at 490.

103 In this case, as Mr A McGrath SC, who appeared with Mr C H Smith for Bega, put it, “both sides are seeking to exercise the rights in the unregistered trade mark of the [PBTD] by taking a protective action against the invasion of goodwill in the form of the actions under the Australian Consumer Law and for passing off. In other words, by these very actions, all of the parties are recognising that the [PBTD] operates as an unregistered trade mark”.

104 Most relevantly for present purposes, the High Court has dealt with the question “what is goodwill?” in three cases: Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605; JT International SA v The Commonwealth of Australia (2012) 250 CLR 1; and Commissioner of State Revenue v Placer Dome Inc [2018] HCA 59, (2018) 93 ALJR 65. Murry and Placer Dome were tax cases. JT International SA v The Commonwealth of Australia was primarily concerned with constitutional questions.

Goodwill is inseparable from the business

105 Those decisions stand for the proposition that goodwill is inseparable from the business to which it adds value and cannot be dealt with except in conjunction with the sale of that business.

106 That much has been understood since the beginning of the twentieth century. As the majority said in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605 at 613, [16], “[o]ne of the most cited definitions of goodwill for legal purposes in the Anglo-Australian legal world is found in the speech of Lord Lindley in Inland Revenue Commissioners v Muller & Co’s Margarine Limited [1901] AC 217 at 235, as follows: