FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v viagogo AG [2019] FCA 544

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 April 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and propose short minutes setting out draft orders for declaratory relief in order to give effect to these reasons, and setting out a timetable for the provision of submissions going to any disagreements between them as to the form of those orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[11] | |

[11] | |

[14] | |

[30] | |

[30] | |

[35] | |

[39] | |

[39] | |

[43] | |

[75] | |

[76] | |

[108] | |

[108] | |

[109] | |

[115] | |

[121] | |

[121] | |

[122] | |

[127] | |

[144] | |

[144] | |

[145] | |

[147] | |

[156] | |

[156] | |

[158] | |

[163] | |

[176] | |

[176] | |

[178] | |

[180] | |

[180] | |

[192] | |

[193] |

BURLEY J:

1 The respondent, viagogo AG is a company incorporated in Switzerland. It operates an Australian website at http://www.viagogo.com.au (viagogo website) from which tickets for live events may be bought and sold. Viagogo refers to this as an online “marketplace” where people who hold tickets for live events may resell them via the viagogo website at a price of their own choosing. If a buyer is found, viagogo adds certain charges, including a booking fee of about 28% of the price of the ticket. The present case in large part depends on whether or not viagogo has made it sufficiently clear that it is not itself an authorised vendor of tickets but the facilitator of re-sale of tickets and that such charges will be levied. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) in its capacity as the regulator under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA), contends that it has not. It claims that viagogo has engaged in misleading conduct in the manner in which it advertises in its sponsored links on Google and the manner in which it presents particular pages of its website. It contends that the conduct of viagogo is in breach of ss 18, 29(1)(h), 29(1)(i), 34 and/or 48(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (being Schedule 2 to the CCA). It claims relief in the form of declarations, injunctions, pecuniary penalties and publication orders.

2 Viagogo denies that the representations as alleged have been made and denies that any of the representations that it did make were false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

3 The case advanced by the ACCC relies on four alleged misrepresentations. The first arises from the use of the words “Buy Now, viagogo Official Site” (the Official Site Representation) contained in sponsored advertisements on Google (viagogo ad) for particular events during the period from 1 May 2017 until 26 June 2017 (relevant period). The ACCC alleges that taken in the context of the promotion of a particular event these words misleadingly created the impression to consumers that viagogo was the official seller of tickets for the event promoted rather than an online platform for the resale of tickets, and thereby engaged in conduct in breach of ss 18, 34 and 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

4 The remaining misrepresentations are alleged to have been made in the viagogo website, which both promotes tickets for sale and provides the means by which purchases can be made. The second is that during the relevant period, a number of statements were made on pages of the website to the effect that tickets were likely to sell out soon, or were in limited supply (defined in section 5.5.1 below as the Quantity Representations), in circumstances where viagogo did not disclose that the references to the remaining number or percentage of tickets available were references only to tickets available from viagogo via its website, and not the number or percentage available for the event generally. The ACCC contends that such conduct was in contravention of ss 18 and s34 of the ACL.

5 The third alleged misrepresentation is that on 18 May 2017, on its “Tickets and Seating Selection Page”, the viagogo website represented in respect of three particular events that a consumer could purchase a ticket for a specified amount, when in fact he or she could not, because additional fees were also payable (Total Price Representation). The Total Price Representation is also alleged to have been made with respect to events more generally during the relevant period. The ACCC alleges that such conduct was in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1) of the ACL.

6 The fourth alleged misrepresentation is that on 18 May 2017, viagogo represented on the “Delivery Page” of its website, a price for each of the tickets offered that excluded further fees payable and failed to specify in a prominent way, and as a single figure, the price of each of the tickets that included additional fees payable (Part Price Representation). The ACCC alleges that such conduct was in contravention of s 18 and s 48(1) of the ACL.

7 There is no dispute that each of the representations, if made, was made in trade or commerce and in connection with the supply or possible supply of services. Viagogo also does not dispute that the phrases identified by the ACCC were used in Google advertisements or the viagogo website. However, as I have noted, it denies making the alleged representations and denies that any representations were false or misleading within the provisions of the ACL upon which the ACCC relies.

8 The ACCC read the evidence of 8 witnesses. Three are officers of the ACCC who provided evidence in the form of video captures and screen shots of the viagogo ad and the viagogo website. The remaining five witnesses are: Terrence Maurice Aherne, Hazel Phyllis Bolding, Victoria Helen Burke, Bruce Alan McDowell and Susan Lynne Symons. They are all consumers who conducted Google searches for events and then followed a link to the viagogo website in order to acquire tickets. I refer to them below as the ACCC lay witnesses. The ACCC relies on their evidence as representing the conduct and reactions or ordinary consumers. Viagogo read the evidence of one witness, Melissa Jane Werry, a solicitor at Minter Ellison. She put into evidence screen shots of the viagogo ad. None of the witnesses were cross-examined. Most of the objections to the evidence were resolved at the hearing, although a number of paragraphs were admitted subject to consideration of their relevance in the context of the arguments put. Rulings in relation to those paragraphs are set out below.

9 The parties cooperated in the presentation of the evidence and in the agreement of relevant but uncontroversial facts, for which they are to be congratulated. By their efforts the proceedings could be heard efficiently and with no unnecessary hearing time. By orders made on 28 March 2018, the question of liability in the proceedings, including as to the entitlement to and terms of any declaratory relief, is to be heard separately from and before the entitlement to other relief.

10 For the reasons set out below, I find that the ACCC has established that viagogo made each of the misrepresentations alleged and that viagogo has acted in contravention of all of the provisions alleged with the exception that it has not established contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL in relation to the Part Price Representation. I direct that the parties confer and propose short minutes setting out draft orders for declaratory relief in order to give effect to these reasons, and a timetable for the provision of submissions going to any disagreements between them as to the form of those orders.

2.1 The relevant provisions of the ACL

11 Section 18(1) and 29(1) of the ACL relevantly provide:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation; or

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services; or

Note 1: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

12 Section 34 provides:

34 Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of services

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any services.

13 Section 48 relevantly provides:

48 Single price to be specified in certain circumstances

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with:

(a) the supply, or possible supply, to another person of goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption; or

(b) the promotion by any means of the supply to another person, or of the use by another person, of goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption;

make a representation with respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of the goods or services unless the person also specifies, in a prominent way and as a single figure, the single price for the goods or services.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

(2) A person is not required to include, in the single price for goods, a charge that is payable in relation to sending the goods from the supplier to the other person.

(3) However, if:

(a) the person does not include in the single price a charge that is payable in relation to sending the goods from the supplier to the other person; and

(b) the person knows, at the time of the representation, the minimum amount of a charge in relation to sending the goods from the supplier to the other person that must be paid by the other person;

the person must not make the representation referred to in subsection (1) unless the person also specifies that minimum amount.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

....

(5) For the purposes of subsection (1), the person is taken not to have specified a single price for the goods or services in a prominent way unless the single price is at least as prominent as the most prominent of the parts of the consideration for the supply.

....

(7) The single price is the minimum quantifiable consideration for the supply of the goods or services at the time of the representation, including each of the following amounts (if any) that is quantifiable at that time:

(a) a charge of any description payable to the person making the representation by another person unless:

(i) the charge is payable at the option of the other person; and

(ii) at or before the time of the representation, the other person has either deselected the charge or not expressly requested that the charge be applied;

(b) the amount which reflects any tax, duty, fee, levy or charge imposed on the person making the representation in relation to the supply;

(c) any amount paid or payable by the person making the representation in relation to the supply with respect to any tax, duty, fee, levy or charge if:

(i) the amount is paid or payable under an agreement or arrangement made under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory; and

(ii) the tax, duty, fee, levy or charge would have otherwise been payable by another person in relation to the supply.

14 The following propositions are relevant to the consideration of the issues in the present case. First, for the enquiry under s 18, it is necessary to identify the impugned conduct and then to consider whether that conduct, considered as a whole and in context, is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. The same applies to the enquiry as to representations and conduct under ss 29(1)(a) and 33, respectively; ACCC v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 (Allsop CJ) at [38]. I add section 34 to that observation.

15 Secondly, conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive if it has the tendency to lead into error, if there is a sufficient causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the person exposed to the conduct. The causing of confusion or questioning is insufficient; it is necessary to establish that the ordinary or reasonable consumer is likely to be led into error (ACCC v Coles at [39]). As the Full Court (French, Heerey and Lindgren JJ) said in SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1821; 169 ALR 1 at 14 [51]:

… The characterisation of conduct as “misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive” involves a judgment of a notional cause and effect relationship between the conduct and the putative consumer’s state of mind. Implicit in that judgment is a selection process which can reject some causal connections, which, although theoretically open, are too tenuous or impose responsibility otherwise than in accordance with the policy of the legislation.

16 A representation is likely to mislead or deceive if it may be expected to or has a capacity or tendency to mislead or deceive. In such a case, “likelihood” means a real and not remote chance or possibility of having that effect; Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1984] FCA 167; 2 FCR 82 at 87 per Bowen CJ, Lockhart and Fitzgerald JJ.

17 Thirdly, it is necessary to view the conduct as a whole and in its proper context. This may include consideration of the type of market, the manner in which such goods are sold, and the habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market. The context will also include relevant disclaimers or explanations: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; 218 CLR 592 at 608 [49] (where the disclaimer, in small print, but in a short document, was “there to be read”); ACCC v Coles at [41]. In the present case viagogo placed some reliance on disclaimers and qualifications.

18 Fourthly, in assessing advertising material, the “dominant message” of the material will be of crucial importance; ACCC v Coles at [42]. The dominant message of an advertisement may be the only one which a consumer takes in, and it is therefore important, as a first step, to identify that message: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1254 (Murphy J) (TPG Internet, first instance) at [43].

19 Fifthly, in many cases it will be necessary to consider the class of persons to whom the representation was directed; S & I Publishing Pty Ltd v Australian Surf Life Saver Pty Ltd [1998] FCA 1463; 168 ALR 396 at 362. Where the persons in question are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual is why the misconception complained of has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief is granted. Where the effect contemplated is on a class of consumers (as in the present case), the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class is to be considered; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [103] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

20 The focus of the inquiry is on whether a not insignificant number within the class have been misled or deceived or are likely to have been misled or deceived by the respondent’s conduct. If, applying the Campomar test, reasonable members of the class would be likely to be misled, then such a finding carries with it the conclusion that a significant proportion of the class would be likely to be misled; National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 61 IPR 420 at [70] and [71] per Jacobson and Bennett JJ. The question may be put slightly differently as whether a “not insignificant number” of “reasonable” or “ordinary” members of that class of the public would, or are likely to, be misled or deceived: Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 98; 280 ALR 639 (Greenwood, Tracey and Buchanan JJ) at [204]–[210] per Greenwood J. In either case, the analysis in the present case remains the same, as does the conclusion.

21 In the present case the context for the relevant consumer is that he or she is engaged in an interaction with the internet and, in the main, with the viagogo website. That is the medium in which the context is to be considered; ACCC v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1177 (Perram J) at [5]. I address the specific characteristics of the relevant consumer in further detail below.

22 Sixthly, whilst the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive”, “mislead or deceive”, “false or misleading” and “mislead” are synonymous, the authorities reveal that a distinction is to be made between “likely to mislead or deceive” (in s 18) and “liable to mislead” (in s 33). The latter has been said to apply to a narrower range of conduct. Under s 33, what is required is that there be an actual probability that the public would be misled (ACCC v Coles at [44]). These observations concerning s 33 ACL apply equally to s 34.

23 Further, in the case of s 34 the words “the public” do not mean the world at large or the whole community. There will be sufficient approach to the public if the approach is general and random, and secondly if the number of people who are approached is sufficiently large; ACCC v We Buy Houses Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 915 (Gleeson J) at [73]. In the present case it is not in dispute that the viagogo ad and website are addressed to “the public” in this sense.

24 Seventhly, evidence from individual consumers that they have been misled by the impugned conduct is of limited utility. It has no statistical significance and the Court cannot draw inferences from it that any section or fraction of the population will have similar reactions; but if the inference is open, independently of such testimonial evidence, that the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then it may be that the evidence of consumers that they have been misled can strengthen that inference; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 234; (2015) 112 IPR 200 (Verrocchi, first instance, Middleton J) at [94], citing State Government Insurance Corporation v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales (1991) 28 FCR 511 at 529 (French J, as he was then). Conversely, the absence of evidence of confusion may also be significant, for instance in cases where the impugned conduct has been going on for a considerable period of time, the applicant was aware of the need for obtaining evidence to support its case and no such evidence was forthcoming; Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (No 4) [2006] FCA 446; 229 ALR 136 (Heerey J) at [81].

25 Eighthly, in ACCC v Coles Allsop CJ said at [46]:

Half-truths may be misleading by the insufficiency of information that permits a reasonably open but erroneous conclusion to be drawn: Fraser v NRMA Holdings Ltd (1994) 124 ALR 548 at 563; Tobacco Institute of Australia Limited v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 FCR 1 at 50. In Tobacco Institute, Hill J referred to the valuable observations of Sheldon J and Sheppard J (when the latter was a member of the Industrial Court) in CRW Pty Ltd v Sneddon (1972) AR (NSW) 17 at 28, as well as making pertinent and valuable observations of his own. Hill J said the following at 50:

However, as was observed by Sheldon and Sheppard JJ in CRW Pty Ltd v Sneddon (1972) AR (NSW) 17 at 28 (the context was the Consumer Protection Act 1969 (NSW):

“An advertisement published in a newspaper is not selective as to its readers. The bread is cast on very wide waters. The advertiser must be assumed to know that the readers will include the shrewd and the ingenuous, the educated and the uneducated and the experienced and inexperienced in commercial transactions. He is not entitled to assume that the reader will be able to supply for himself or (often) herself omitted facts or to resolve ambiguities. An advertisement may be misleading even though it fails to deceive more wary readers.”

Where, as in the present case, the advertisement is capable of more than one meaning, the question of whether the conduct of placing the advertisement in a newspaper is misleading or deceptive conduct must be tested against each meaning which is reasonably open. This is perhaps but another way of saying that the advertisement will be misleading or likely to mislead or deceive if any reasonable interpretation of it would lead a member of the class, who can be expected to read it, into error: Keehn v Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd (1977) 14 ALR 77 at 81 per Northrop J and cf the approach taken by Mason J in Parkdale.

26 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1263 Foster J noted at [39], in the context of a case brought under s 18 and 29(1)(i) and (m) of the ACL, that in the case where a headline representation is sought to be qualified by other material, the qualifying material must be sufficiently prominent to prevent the headline representation from being misleading. The degree of prominence required will vary with the potential for the primary statement to be misleading (citing Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1 at 17–18 [37]–[41] per Stone J, Moore and Mansfield JJ agreeing). In that regard, it is the overall impression created by the representation that must be assessed.

27 Conversely, Gibbs CJ pointed out, of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (which is in substantively the same terms as s 18 of the ACL) in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Proprietary Limited v Puxu Proprietary Limited [1982] HCA; 149 CLR 191 at 199 [9]:

Although it is true, as has often been said, that ordinarily a class of consumers may include the inexperienced as well as the experienced, and the gullible as well as the astute, the section must in my opinion by (sic) regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class. The heavy burdens which the section creates cannot have been intended to be imposed for the benefit of persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. What is reasonable will or (sic) course depend on all the circumstances. The persons likely to be affected in the present case, the potential purchasers of a suite of furniture costing about $1,500, would, if acting reasonably, look for a label, brand or mark if they were concerned to buy a suite of particular manufacture.

28 Ninthly, the High Court observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [50] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ) that actionable misleading or deceptive conduct is not limited to conduct which induces or is likely to induce entry into a transaction. Conduct which misleads a consumer so that, under some mistaken impression of a trader’s connection or affiliation, he or she opens negotiations or invites approaches may be misleading or deceptive even if the true position emerges before the transaction is concluded. See also SAP Australia at [51]; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 104; 247 FCR 570 (Verrocchi, Full Court) at [68].

29 To these matters must be added the observation that the ACCC bears the onus to prove the case that it has advanced to the requisite civil standard having regard to the gravity of the matters alleged; s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and the principles set out in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361 and 362; see ACCC v We Buy Houses at [44].

3. THE CONTEXT OF THE ALLEGED REPRESENTATIONS

30 It is convenient to explain how the viagogo ad and viagogo website are likely to appear to the ordinary consumer before turning to consider the alleged contraventions of the ACL. In the case of the viagogo ad, this is relatively simple as it consists of a single entry amongst a list of entries on a search results page. In the case of the viagogo website providing a description is more complicated, because the consumer interacts with the website in a dynamic way. As the ACCC case is based on the content of the viagogo website in the past, during the relevant period, the ACCC chose to prove the primary facts by tendering in evidence video captures taken by officers of the ACCC. I am satisfied that these provide a fair representation of the viagogo website on the dates that the videos were created.

31 Mitchell Shepherd is an investigator in the Enforcement Division of the ACCC. In about April or May 2017, he created an account with viagogo as part of the ACCC investigation. On 18 May 2017 Mr Shepherd recorded video captures of the booking processes on the viagogo Australia website for:

(1) A ticket to the theatre show The Book of Mormon at the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, to be held on 20 May 2017 for $135 per ticket;

(2) Two tickets to the Cat Stevens concert at Rod Laver Arena in Melbourne to be held on 27 November 2017 for $225 per ticket; and

(3) Three tickets to The Ashes Cricket Test Match at the “Gabba” cricket ground in Brisbane to be held on 26 November 2017 for $110.05 per ticket.

These are referred to below as the 18 May 2017 tickets.

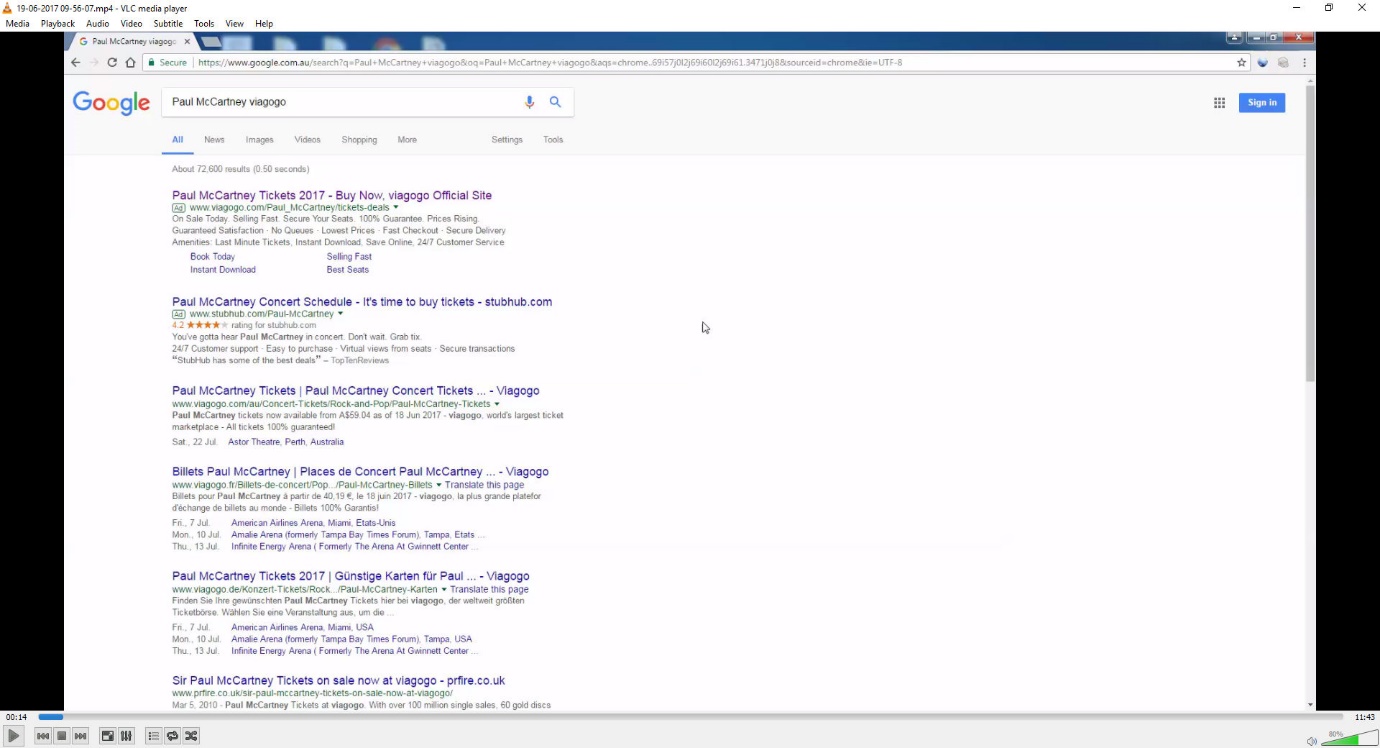

32 Vinh Trung Tang is a Senior Investigator for the ACCC. On 19 June 2017, Mr Tang recorded a video capture of the booking process for two tickets to the Paul McCartney concert at the Astor Theatre in Perth, to be held on 22 July 2017. For the video capture, Mr Tang typed “Paul McCartney viagogo” into the Google search engine. The first result which came up was “Paul McCartney Tickets 2017 – Buy Now, viagogo Official Site”. He navigated through the viagogo website to carry out the booking process for the tickets. He then used “Snagit”, a program that allows a user to capture still images of web pages displayed on a computer screen, to take 18 still image captures of the same booking process.

33 The ACCC contends that the Official Site representation was made in the viagogo ad. It adduced evidence of that advertisement in the affidavits of Susan Lynne Symonds (one of the ACCC lay witnesses) and Mr Tran.

34 In section 3.2 below, I set out images of the viagogo ad. In section 3.3 I describe, by reference to screenshots previously taken by Mr Shepherd, what I consider to be a typical interaction by a consumer interested in ascertaining information about and/or purchasing tickets via the viagogo website. Having regard to the whole of the evidence, I consider that the Book of Mormon example chosen by Mr Shepherd is a suitable one for the purposes of analysis. The parties have pointed out that there are some differences between the web pages for Book of Mormon on 18 May 2017 and for other events in evidence that fall within the relevant period. On the whole I do not consider them to be material to the analysis of the arguments. Where potentially relevant differences arise, I have addressed them in my reasons.

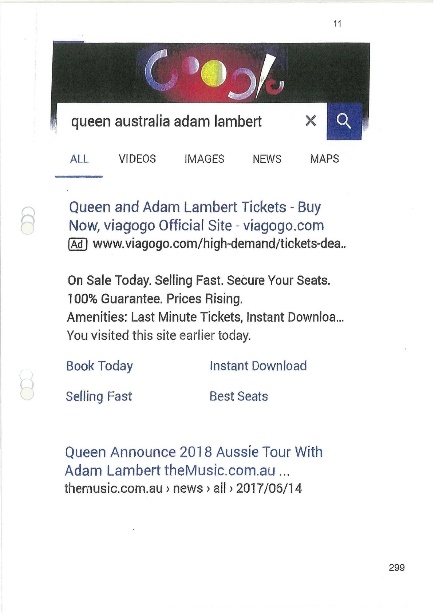

35 There is no dispute that during the relevant period, advertisements for Viagogo which included the words "Buy Now, viagogo Official Site" were displayed in the search results on the Google search engine. The evidence of the ACCC lay witnesses is that each entered into a Google search the name of the event or performance that he or she wished to attend. The result produced was in the form of a list. The first result was a sponsored link to the viagogo website. By clicking on the link in that advertisement, Ms Symons was taken to the viagogo Homepage, to which I refer below. The screenshot taken by Ms Symons on 21 June 2017 on her mobile phone, to which reference is made below in [105], is as follows (Symonds screenshot):

36 Viagogo contends that this evidence does not place the viagogo ad in sufficient context to enable a proper evaluation of the Official Site Representation because it does not include the full list of search results. Viagogo relies on the evidence of Ms Werry, who in or around September 2017 conducted searches using the Google search engine with the phrases “Book of Mormon Sydney” and “Cat Stevens tickets”. The results page for the “Book of Mormon Sydney” search shows the viagogo site as the first result. The listing reads “The Book of Mormon in Pyrmont – Buy Now, viagogo Official Site”. Underneath these words is a box with the word “Ad” and the URL for the viagogo webpage. Other websites are also listed on the page, to which viagogo draws particular attention. The results page for the “Cat Stevens tickets” search shows the viagogo site as the first result. The listing reads “Cat Stevens Tickets 2017 – Buy Now, viagogo Official Site – viagogo.com”. Underneath these words is a box with the words “Ad” and the URL for the viagogo webpage for those tickets. A relevance objection was taken to the evidence of Ms Werry, because her searches were conducted outside the relevant period. I consider that the evidence that the search results are likely to appear in a format such as that shown in the results page tendered through the evidence of Ms Werry could rationally affect the assessment of the Official Site Representation, although given its date, it is of diminished weight, and I have treated it accordingly.

37 The evidence of Mr Tang is that he also conducted a search on Google, although he used the search terms “Paul McCartney viagogo” (the ACCC witnesses were not familiar with viagogo and did not use that word in their searches). The result of this search, conducted on 19 June 2017, was as follows:

38 By following the link on the first result, rather than being taken to the Homepage, Mr Tang was taken directly to the Event Specific Page, to which I refer below.

39 During the relevant period, the nine web pages on the viagogo Australian website that a consumer could navigate through were:

(a) Homepage;

(b) Category Specific Page;

(c) Event Specific Page;

(d) Tickets and Seating Selection Page;

(e) Quantity Selection Page;

(f) Buyer Details Page;

(g) Delivery Page;

(h) Payment Page; and

(i) Review Page.

40 Each of these pages contains a significant amount of content. To view the entirety of each page, the consumer was obliged to scroll down, the amount of scrolling depending on the size of the screen of the device used. Samples of parts of each page are described further below. It may be seen from the vertical scroll bar on the right hand side of each page what portion of the total screen real estate available is used by the page depicted.

41 Before proceeding to consider the website in detail, it is appropriate to note two facts agreed by the parties. First, during the relevant period, on the Homepage, tickets for different events were advertised with a price "From A$X" (with X being a dollar amount in Australian dollars, where the currency was set to Australian dollars). The ticket prices advertised on the Homepage were prices set by third party sellers, not Viagogo. Viagogo charged consumers who purchased a ticket on the Viagogo Australian website two additional fees:

(a) A "VAT and Booking Fee"; and

(b) A "Secure Ticket Handling Fee",

(the viagogo fees).

42 Second, during the Relevant Period the viagogo fees were calculated as follows:

(a) the Booking Fee component of the "VAT and Booking Fee" was calculated by Viagogo as a percentage of the ticket price set by the third party seller;

(b) the VAT Fee component of the "VAT and Booking Fee" was applied depending on the location of the buyer's billing address and, where applicable, calculated by reference to the amount of the Booking Fee; and

(c) the "Secure Ticket Handling Fee" was calculated by reference to the delivery option for the tickets and the buyer's location.

3.3.2 Purchasing tickets using the viagogo website

43 The video captures taken by Mr Shepherd demonstrate the process that he used to acquire tickets, commencing at the viagogo Homepage. Except where otherwise noted, the images below relate to the booking process for tickets to The Book of Mormon. (I note that the images have been slightly cropped from the original screenshots, in order to allow the writing on the webpages to be legible.) Prior to commencing this process, Mr Shepherd had created an account with viagogo by creating a username and a password. This meant that the process undertaken by Mr Shepherd involved a slightly different payment process to that used by the ACCC lay witnesses.

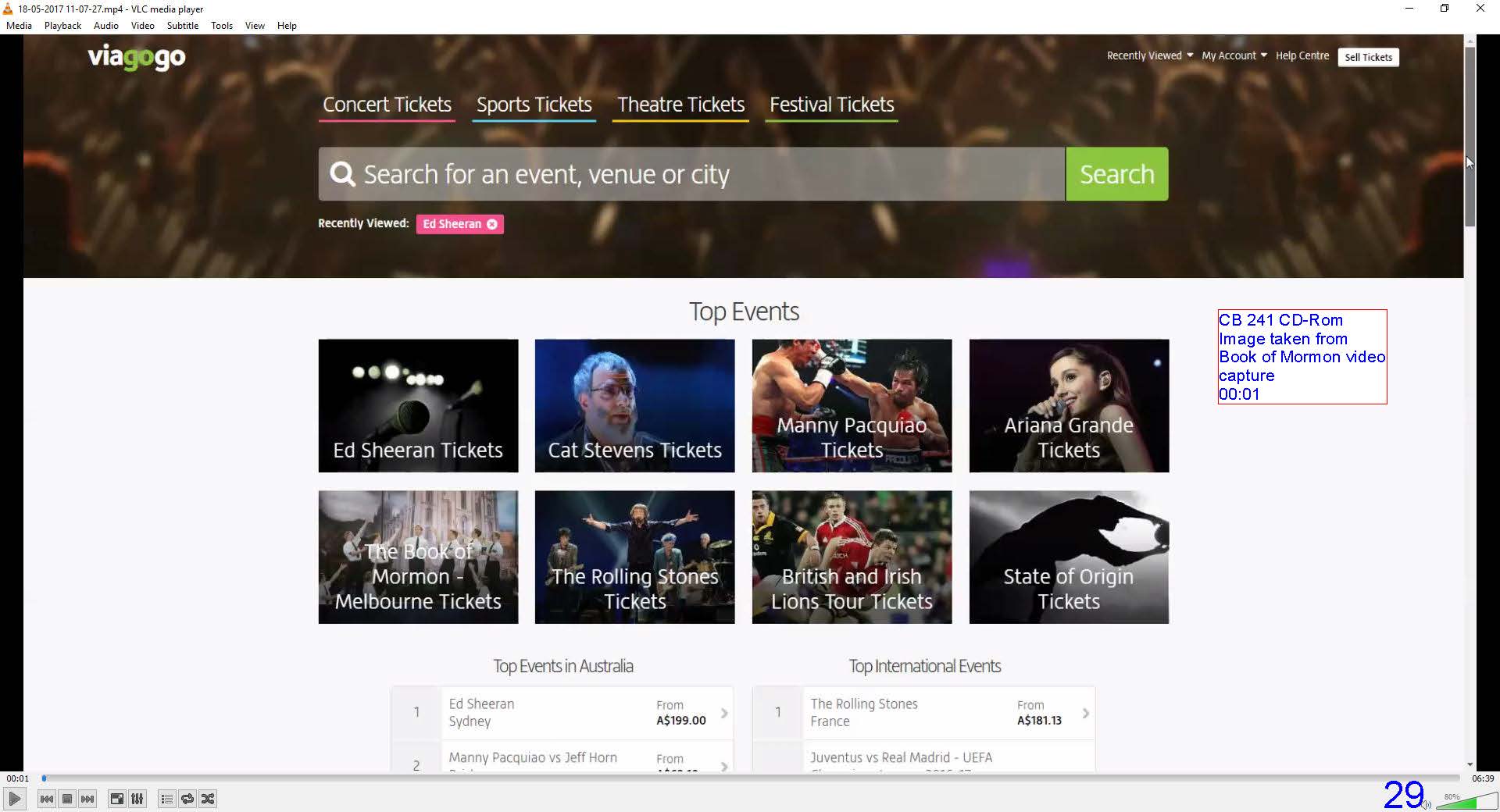

44 The initial screen for the homepage for the viagogo website in the relevant period commenced as follows:

45 It will be seen that on the top right hand corner of the homepage is a “sell tickets” button. This is moved out of view as the user scrolls down.

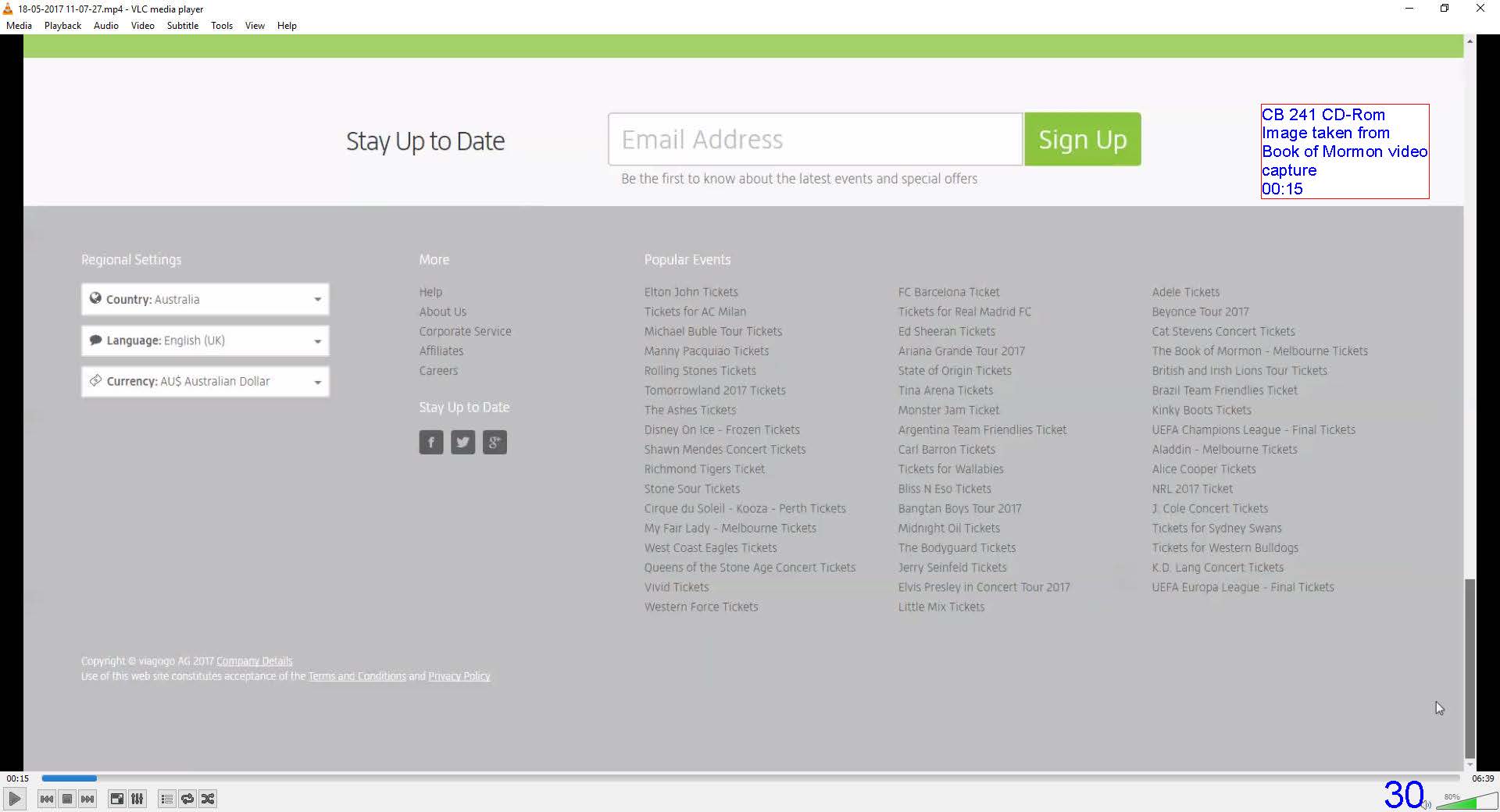

46 If one scrolls beyond the list of “Top Events” and the lists of “Top Events in Australia” and “Top International Events” (pictured above), one sees lists of “Upcoming Events Around Highgate Hill” and “Top Destinations for Events” which appear in a similar format to “Top Events” with named destinations or events appearing in rectangular photographs. On a typical laptop, one would scroll through several screens to reach the lowest portion, which is as follows:

47 I refer to this portion as the final segment. The white writing on the lower left portion of this screen shot includes a link to “Terms and Conditions”. None of the ACCC lay witnesses gives evidence that they clicked on the link. The final segment is common to each webpage until the Quantity Selection Page, although the Regional Settings for language and currency then remain, as does the material set out in the white letters on the lower left hand of the screenshot.

48 The Category Specific Page (not shown) arises if the consumer clicks on one of the “concert tickets”, “Sports Tickets”, “Theatre Tickets” or “Festival Tickets” options at the top of the home page. From there one may navigate to an Event Specific page.

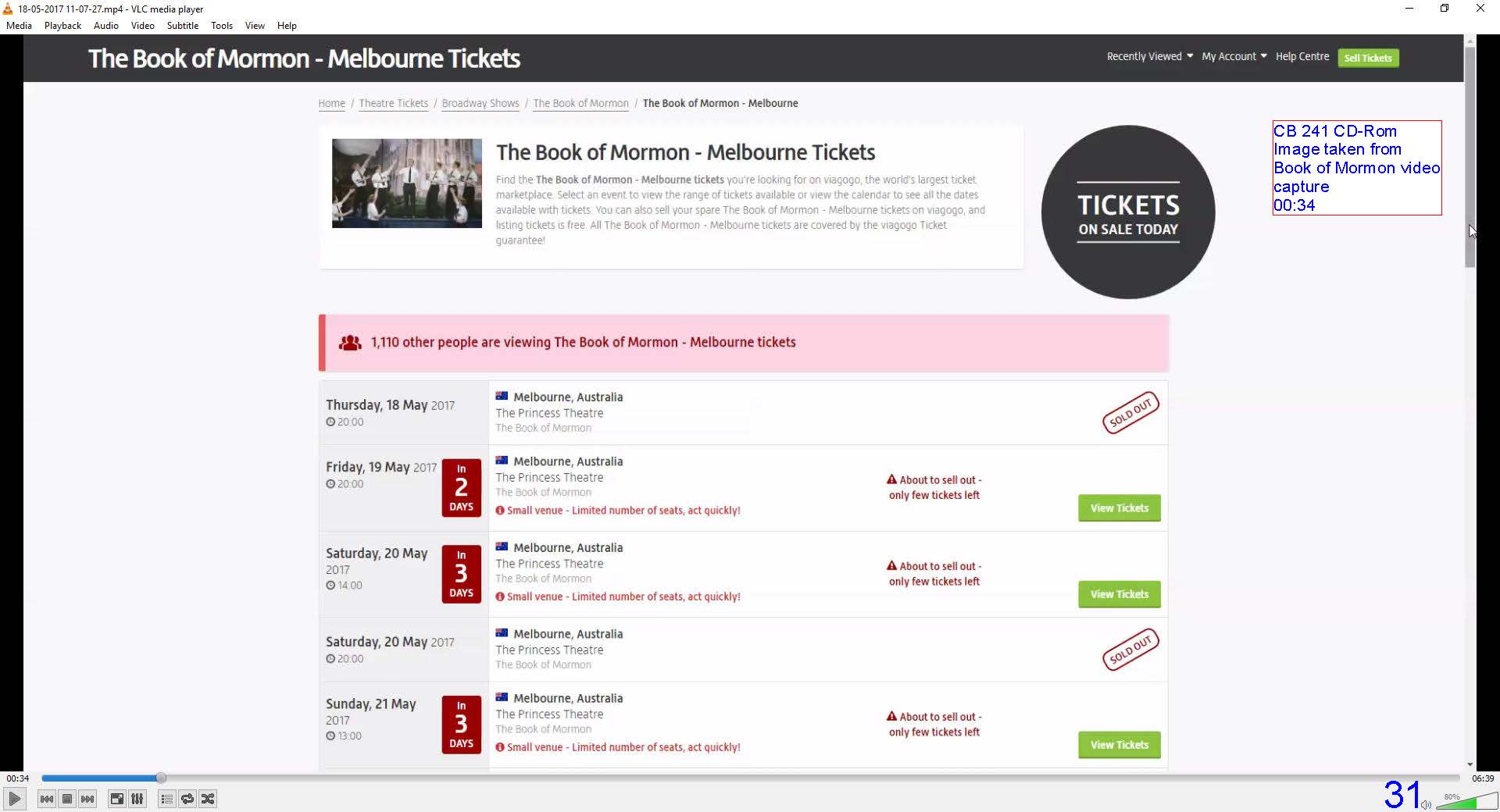

49 Alternatively, by clicking on a particular event on the homepage, which for the Book of Mormon appears listed in the “Top Events” boxes, the viewer arrives at the Event Specific Page. The consumer could also arrive at this page from the Category Specific Page. Mr Shepherd took a screenshot of the initial view of this page:

50 It will be seen that under the heading “The Book of Mormon – Melbourne Tickets” the following small, grey words appear (Event Description) (italics added):

Find the The Book of Mormon – Melbourne tickets you’re looking for on viagogo, the world’s largest ticket marketplace. Select an event to view the range of tickets available or view the calendar to see all the dates available with tickets. You can also sell your spare The Book of Mormon – Melbourne tickets on viagogo and listing tickets is free. All The Book of Mormon – Melbourne tickets are covered by the viagogo Ticket guarantee!

51 The italicised words do not appear on all versions of the website taken during the relevant period that are in evidence. They do not appear in Mr Shepherd’s video capture of the Cat Stevens event, but they do appear in his capture of the purchase of the Ashes tickets, and on Mr Tang’s video capture of the Paul McCartney tickets. The “sell tickets” button, now coloured green, is still present in the top right hand corner. It remains there until the user clicks through to the Quantity Selection Page.

52 The pink horizontal line with the words “1,110 other people are viewing The Book of Mormon – Melbourne tickets” is visually arresting. Several of the listed events are stamped “sold out” in red. For the 20 May 2017 performance, the words “Small venue – Limited number of seats, act quickly” and “! About to sell out – only a few tickets left” are displayed in red.

53 Beneath the pink horizontal line is a list of events by date. The user must scroll down to reach the bottom of the page where the final segment appears.

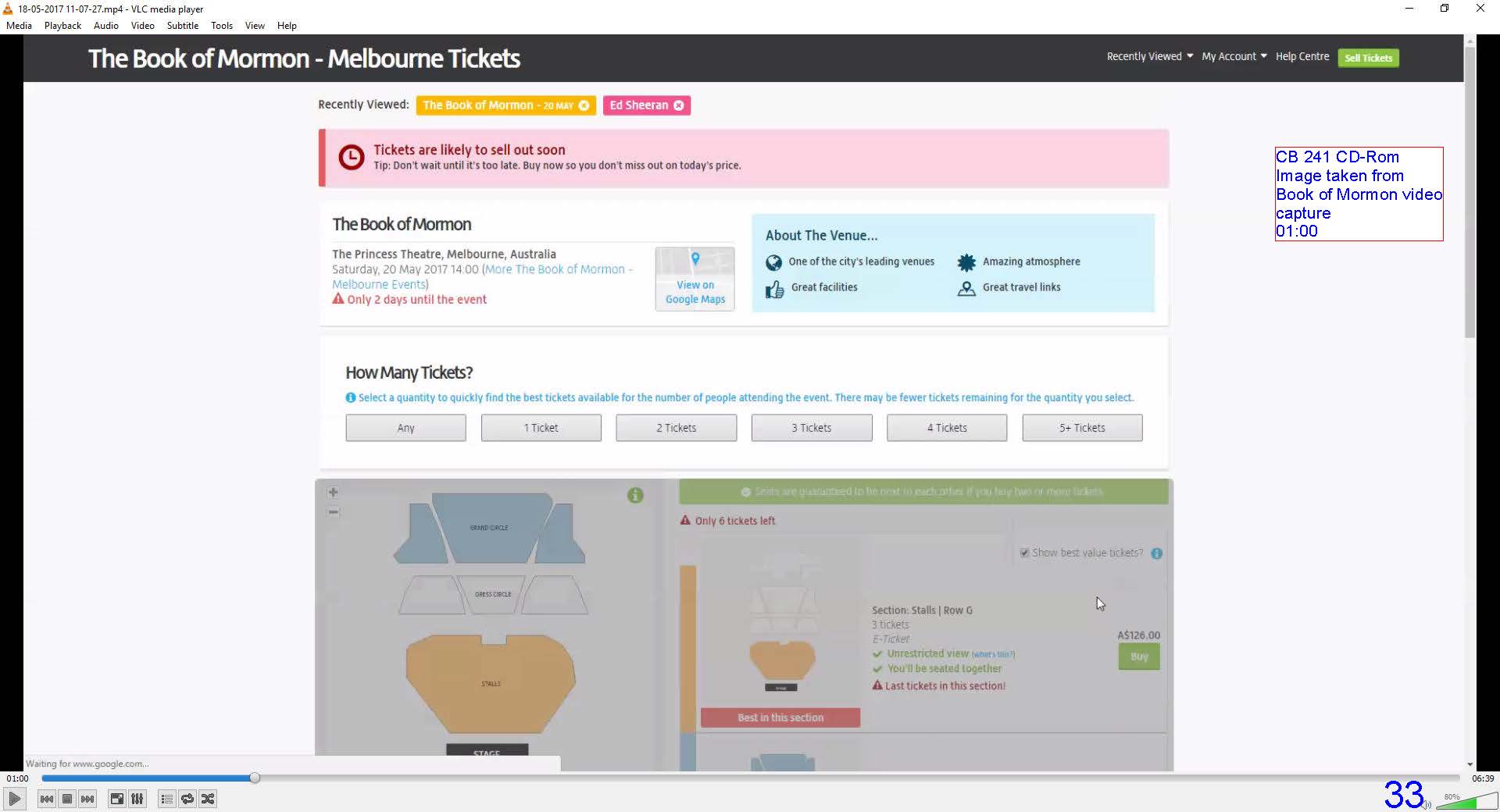

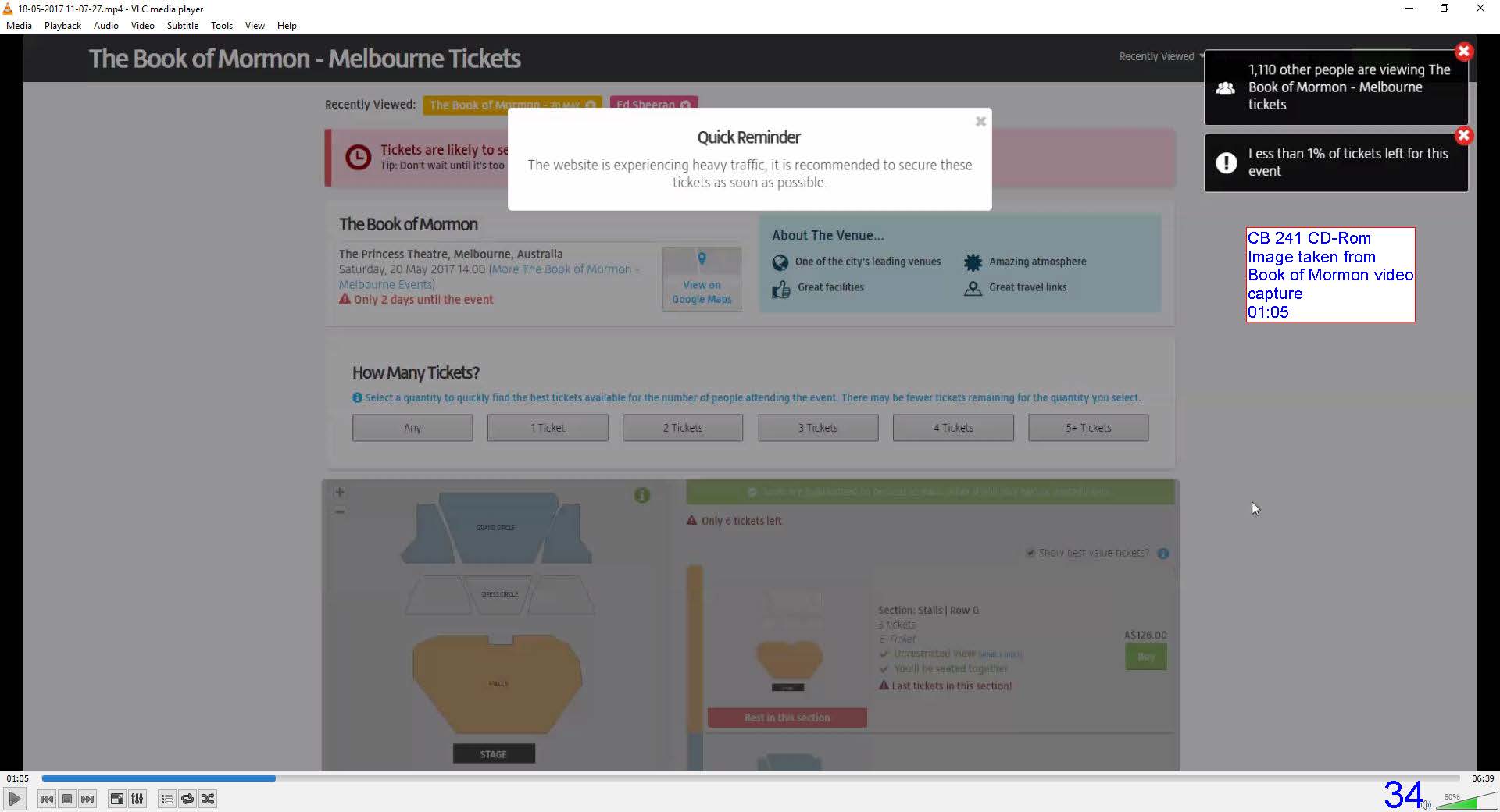

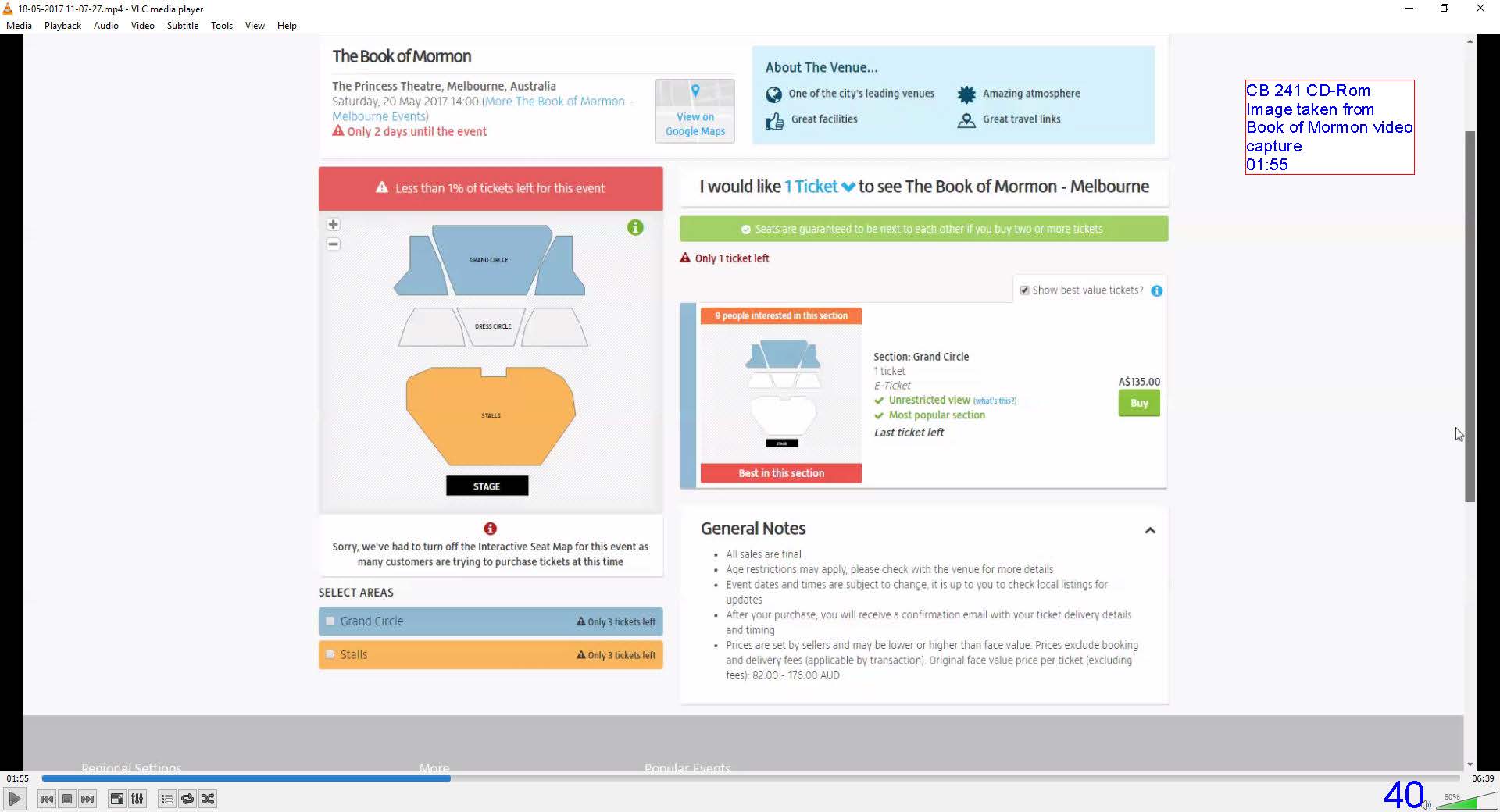

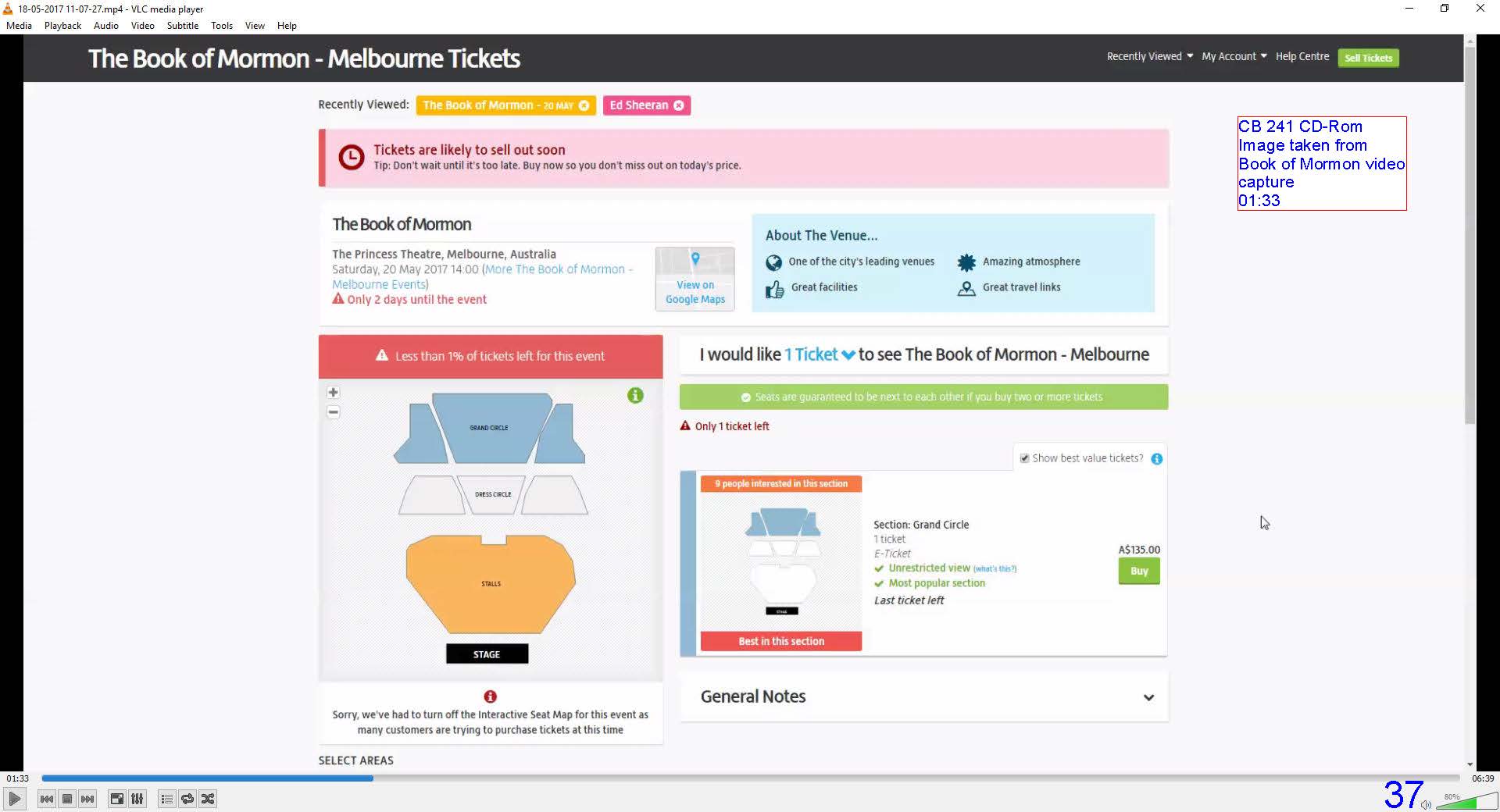

54 Mr Shepherd selected the “view tickets” option for the performance of the Book of Mormon on 20 May 2017. This took him to the Tickets and Seating Selection Page. On this page the consumer must identify the quantity of the tickets he or she wishes to purchase and select seats from the available options. The portion that first appears on the screen is as follows:

55 It will be seen that in the pink banner near the top are the emphasised words “Tickets are likely to sell out soon” and “Tip: don’t wait until it’s too late. Buy now so you don’t miss out on today’s price”. Beneath this an opportunity to select the number of tickets to purchase is provided together with a seating chart. Within the chart, which has a grey wash over it, are the words in red “Only 6 tickets left”.

56 After 3 or 4 seconds, three pop-up screens intrude into the page and the balance of the screen is covered in a grey wash which has the effect of dimming the view of the contents of the screen, with the exception of the pop ups. A large pop-up in the centre states: “Quick reminder. The website is experiencing heavy traffic, it is recommended to secure these tickets as soon as possible” (pictured below). The two smaller pop-up boxes on the right say that “1,100 other people are viewing Book of Mormon – Melbourne tickets” and that there are “Less than 1% of tickets left for this event”. After about 15 seconds the pop ups disappear automatically unless the user first clicks on the crosses in the top right corner.

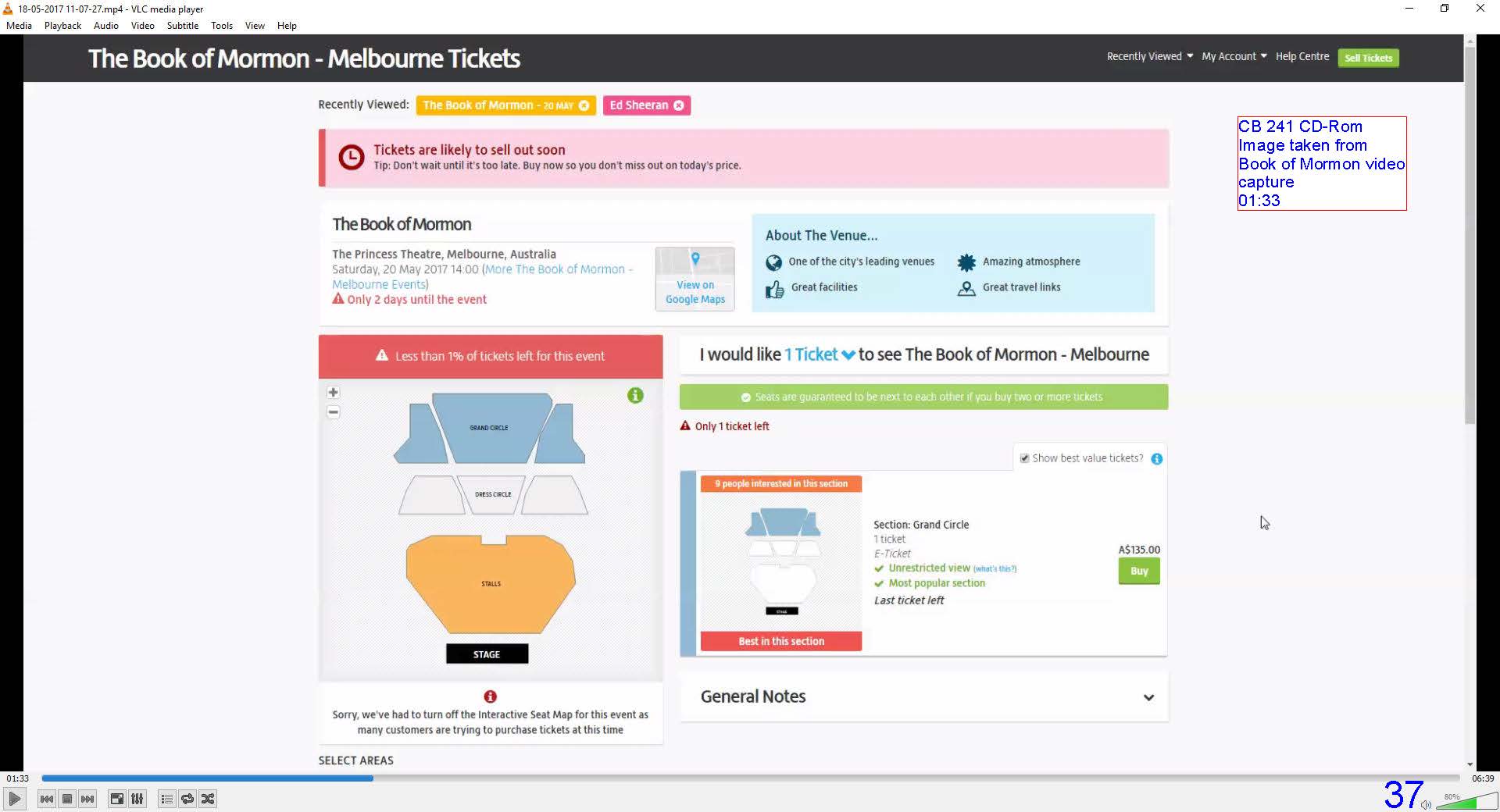

57 The user may scroll down to see what tickets are available. A horizontal row of virtual buttons contains options for a number of tickets that may be purchased. When the user selects the “1 ticket” button, the horizontal row disappears and the following screen is shown:

58 It will be seen that the page displays a price of $A135 for a single ticket, states that there is 1 ticket available in the grand circle, and includes a “General Notes” section with an arrow. It is necessary to click on the arrow to see the General Notes. If one does so, then the General Notes appear as depicted below.

59 They provide:

• All sales are final

• Age restrictions may apply, please check with venue for more details,

• Event dates and times are subject to change, it is up to you to check for updates

• After your purchase, you will receive a confirmation email with your ticket delivery details and timing

• Prices are set by sellers and may be lower or higher than face value. Prices exclude booking and delivery fees (applicable by transaction). Original face value price per ticket (excluding fees): 82 – 176 AUD

60 Viagogo notes that for tickets to the Paul McCartney concert, the General Notes appear without the need to press a drop down menu. This is said to be material, although for reasons given below I do not agree.

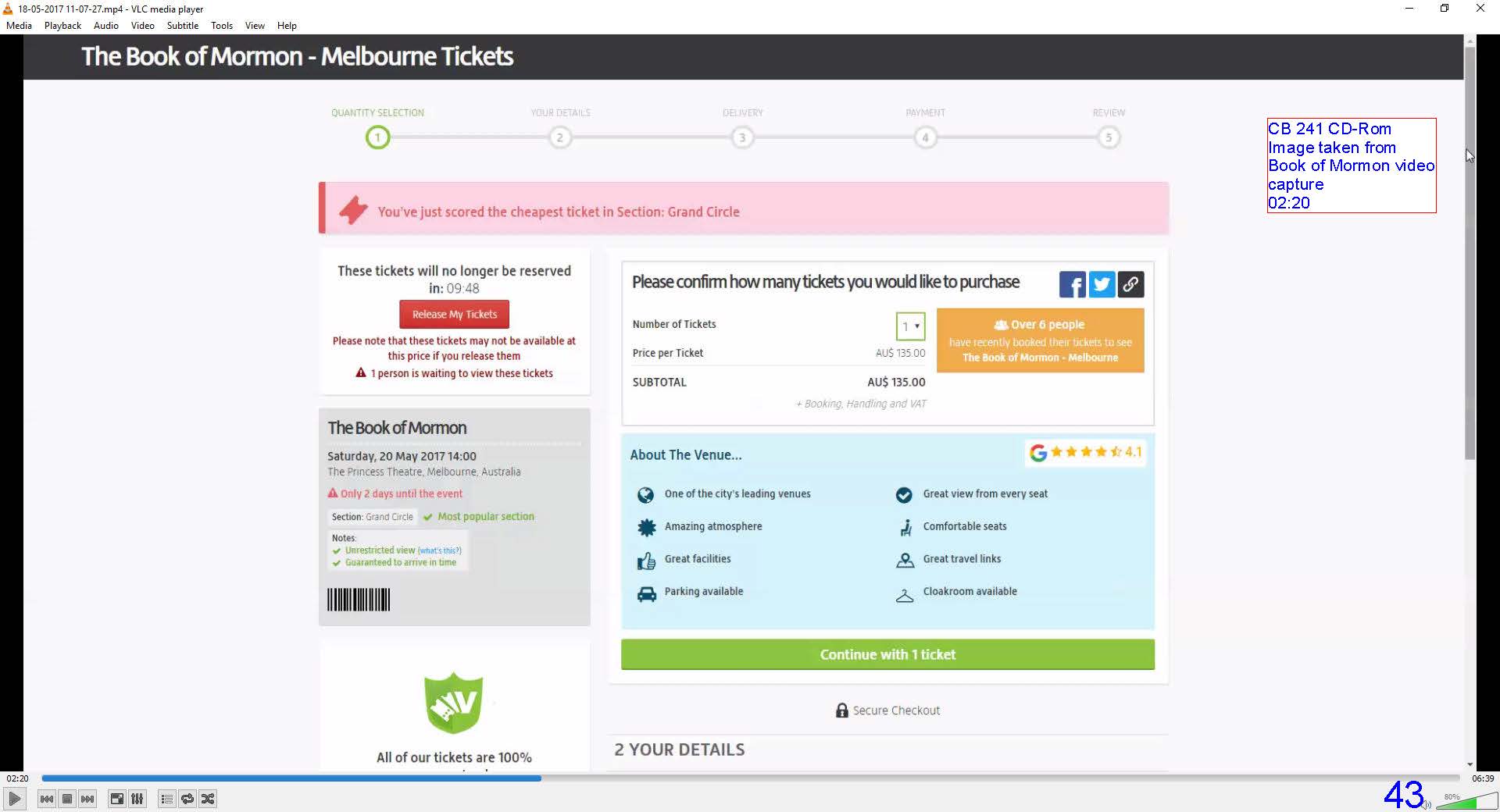

61 If the user clicks the “BUY” button, the first part of the Quantity Selection Page then appears. On this page the user is required to confirm the number of tickets he or she intends to purchase. The initial view is as follows:

62 This page also presents a significant amount of information. Across the top is a progress line indicating (in a faint font) a purchaser’s progress through five stages of acquisition: quantity selection, your details, delivery, payment, and review. On the left, below a pink horizontal band, is a countdown clock stating “These tickets will no longer be reserved in: [minutes and seconds are displayed ticking down from 10 minutes]”. Directly below this is a red box with the words “Release My Tickets”, and below that are the words “Please note that these tickets may not be available at this price if you release them” and “! 1 person is waiting to view these tickets”. On the right of the screen is a box asking the user to confirm how many tickets he or she would like to purchase and listing the “Price per ticket” as AU$ 135.00. In bold is “SUBTOTAL AU$135.00”. In grey beneath it is + Booking, Handling and VAT, in fine and faintly rendered letters.

63 After a few seconds the screen goes grey and a pop-up appears informing the user that the tickets “are yours for: 9:55” indicating that countdown clock is continuing. The user clicks “OK” to remove this pop-up screen. When the countdown clock reaches 09:50, it pulses. After that, it pulses once every 10 seconds, adding to the sense of urgency. After another few seconds a further pop-up appears, with the clock continuing and reminding the user that 1 person is waiting to view these tickets. It will be seen that on the lower left hand portion of the Quantity Selection Page, beneath the grey box containing a barcode, is a guarantee which is represented by a shield device (shown) beneath which in bolded writing (partially shown) is: “All of our tickets are 100% guaranteed” following which in somewhat smaller font appears (emphasis in original):

What does that mean? It means that you can buy with confidence. We guarantee that you’ll get valid tickets in time for the event.

Over 10 million fans have gone to their favourite events!

64 This text is followed by the final segment.

65 When Mr Shepherd clicked the “continue with 1 ticket” bar on the lower right hand side the process skipped stage 2 (“your details”) because he had a username and details. Mr Tang had not earlier created an account with viagogo and so was prompted to complete his name, email address and phone number on the Buyer Details Page before he could continue.

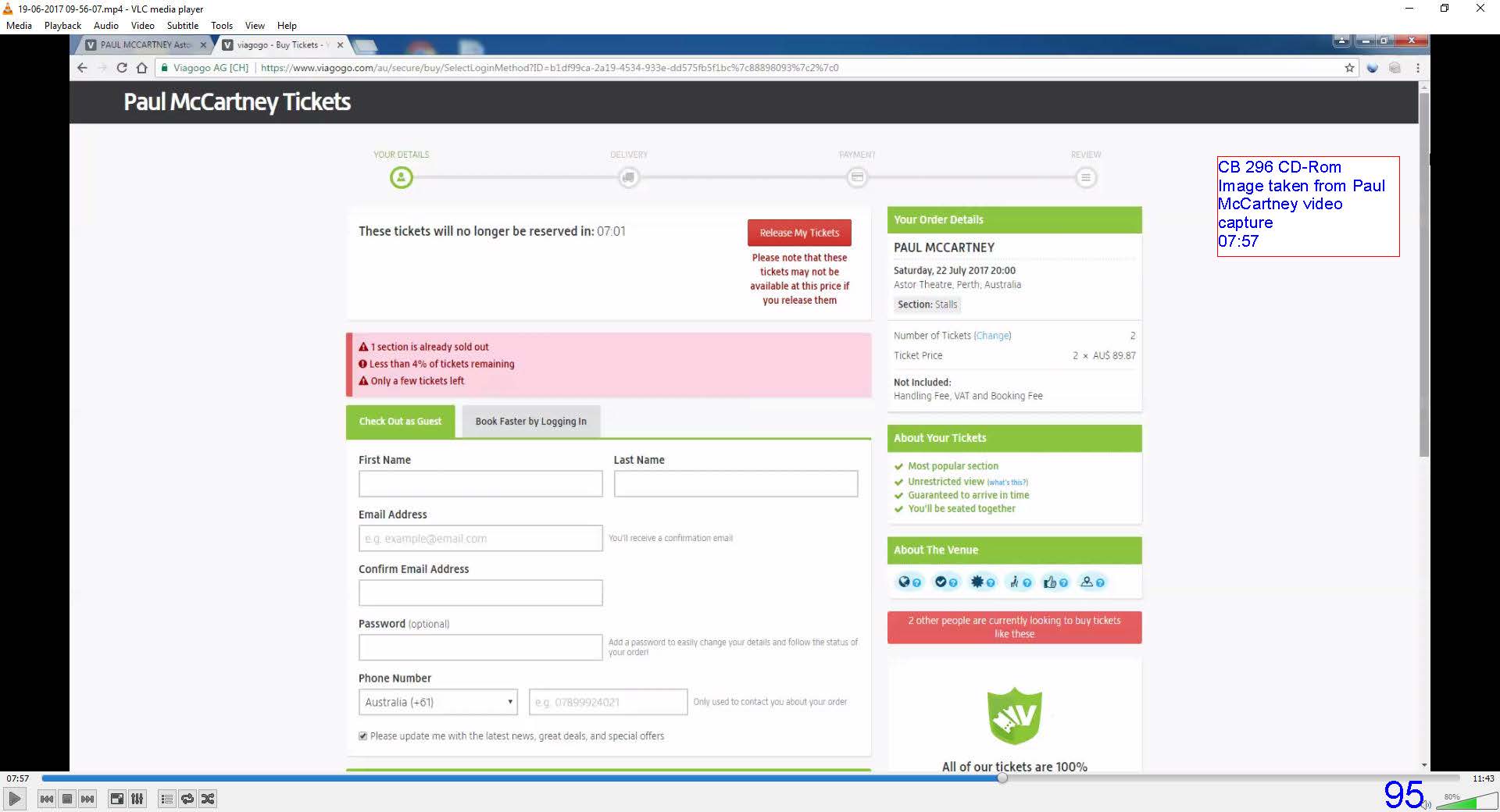

66 A screenshot taken by Mr Tang of the Buyer Details Page for a Paul McCartney concert is set out below. Here, the consumer is asked to provide his or her contact details, including an Australian telephone number. This page will not appear if the consumer had already logged into his or her viagogo account:

67 In this example, words such as “These tickets will no longer be reserved in: 07:01 [minutes]” and, in the pink banner, “! 1 section is already sold out / ! Less than 4% of tickets remaining / ! Only a few tickets left” continue to add a sense of urgency for the consumer. On the lower right portion, the guarantee appears. I now return to the Book of Mormon example.

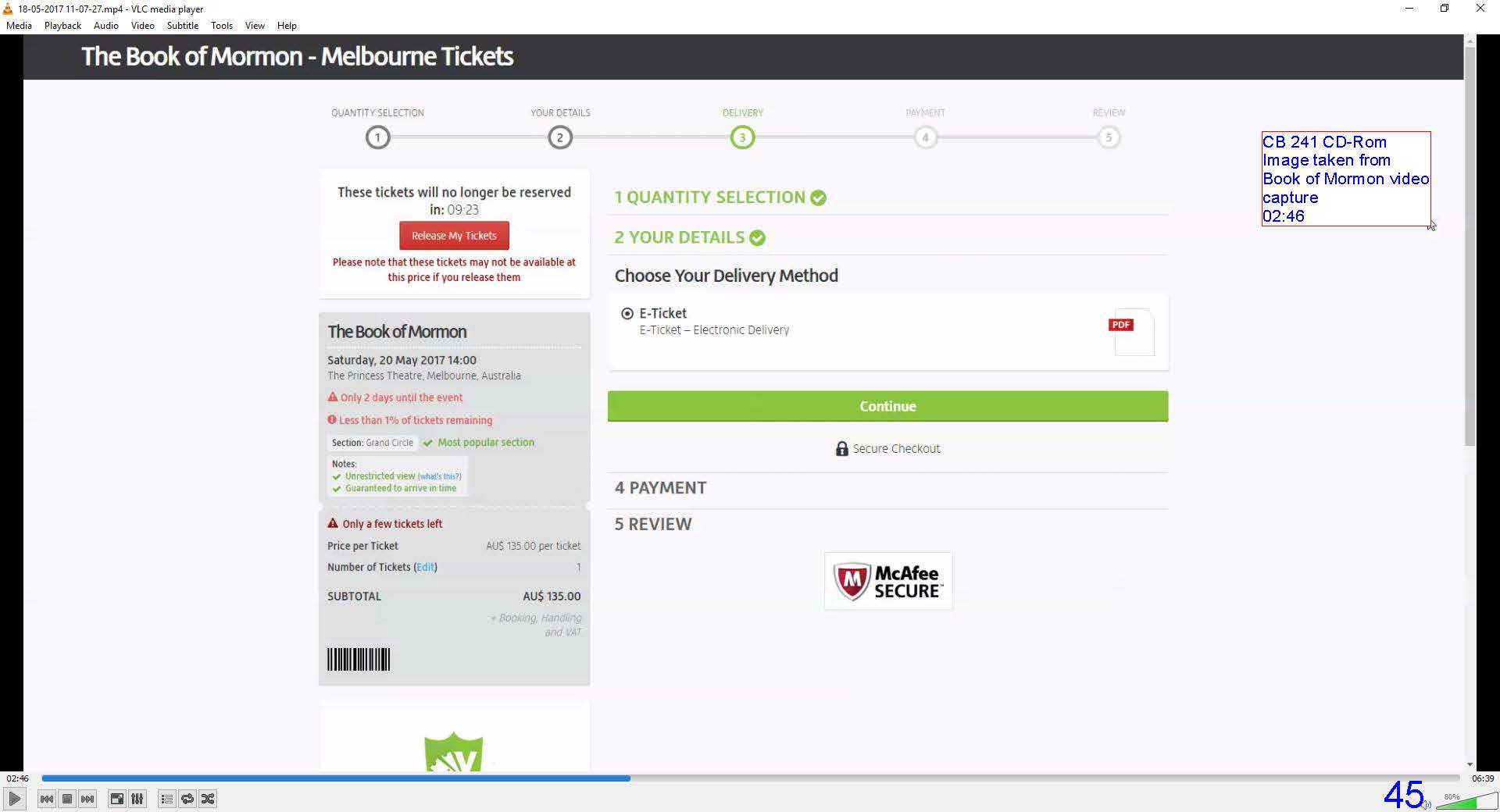

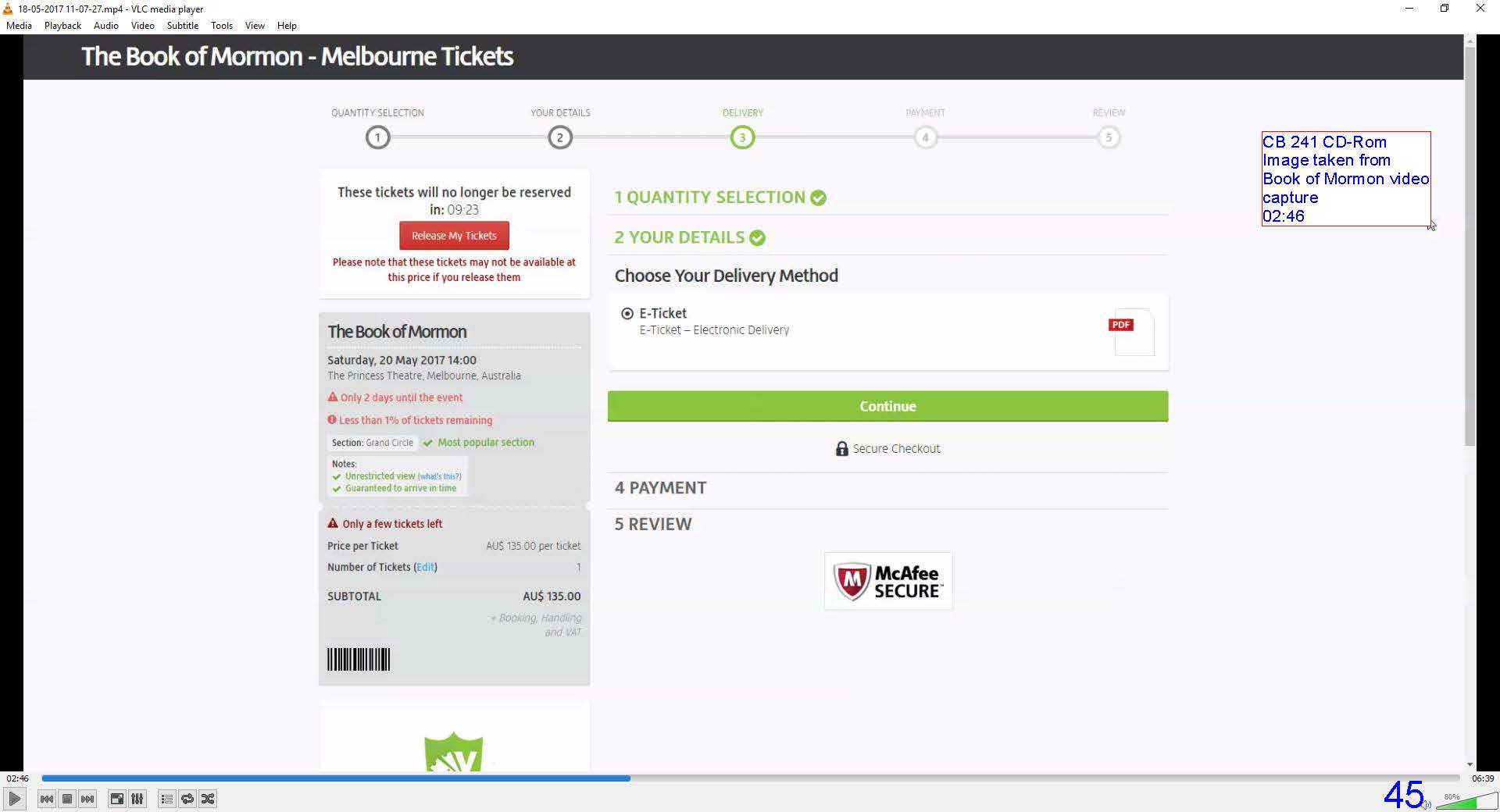

68 On the Delivery Page the user is required to choose the delivery method of the ticket or tickets (if different delivery methods were available). The top portion of the Delivery Page captured by Mr Shepherd is depicted below. It will be seen that the price per ticket and “SUBTOTAL” of $AU135 is displayed in bold above a faint reference in grey to booking, handling and VAT. The only delivery option identified here is “E-Ticket”. By scrolling down, the user sees the guarantee and then the final segment. The count-down clock continues to pulse, by way of emphasis that the user must keep moving forward before the transaction times out.

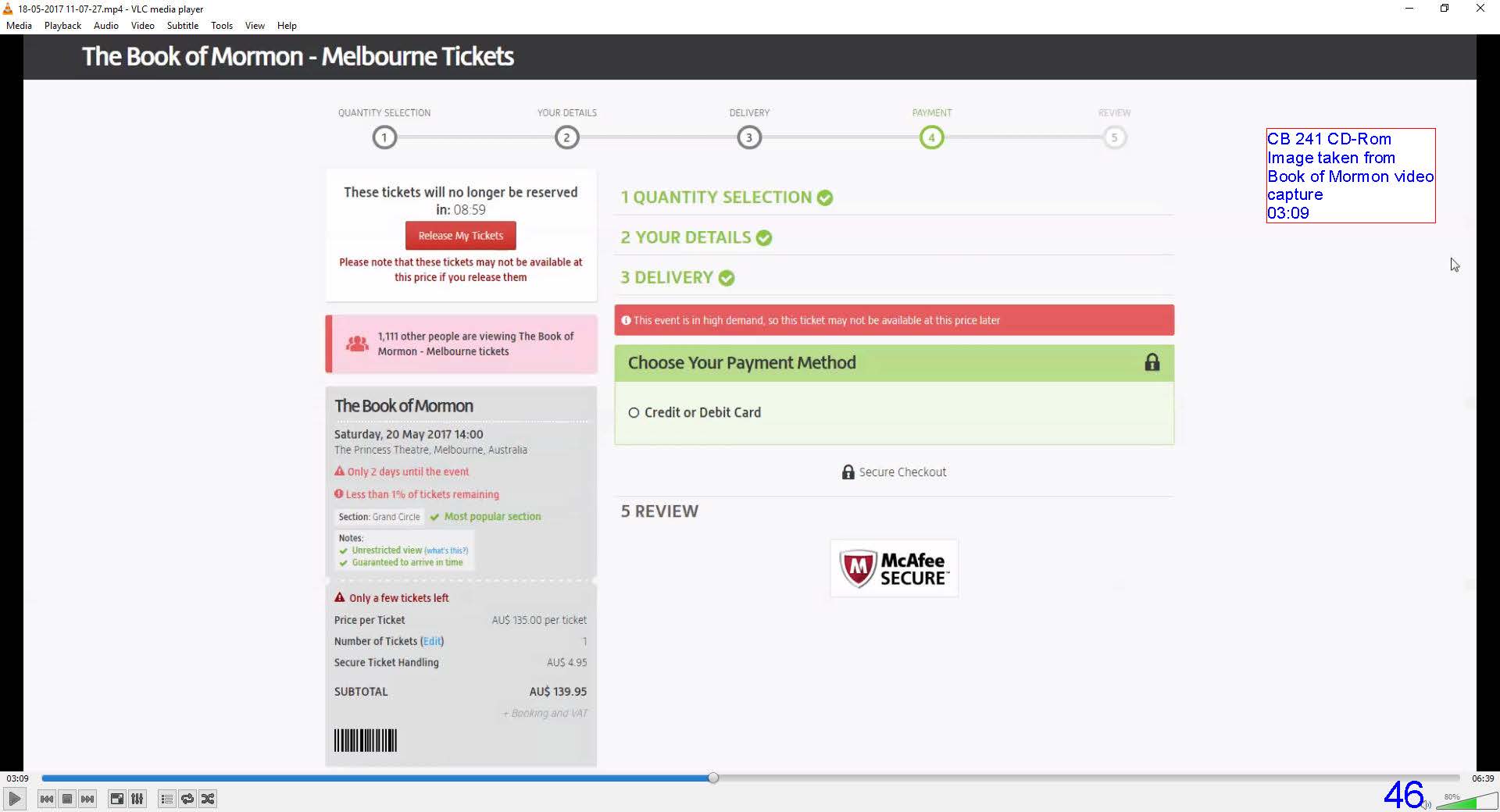

69 After clicking the green horizontal “continue” bar on the Delivery Page, the user is taken to the Payment Page. On this page the user provides credit or debit card details and confirms his or her billing address. Mr Shepherd’s screen shot is below:

70 After a few seconds, various “hurry up” additions appear on the screen. One such message puts the screen in grey and says “Quick reminder: The website is experiencing heavy traffic, it is recommended to secure these tickets as soon as possible”. The pop up leaves after a few seconds, but the countdown clock continues on the left hand side. The countdown clock hovers independently of the screen, so it remains in the same position and is obvious even when one scrolls up and down within the screen. Additional messages appear in pink boxes beneath the countdown clock, for instance, “Hurry up! 62 other people are viewing this event” and “There is 1 person viewing these tickets”. The countdown clock continues to pulse once every 10 seconds.

71 On the right hand side the user is asked to choose a method of payment, and is reminded by words appearing in a horizontal red band above the prompt that the event is in high demand, so this ticket may not be available at this price later. After choosing the credit card option, the user is provided with prompts to fill in the details. During the process of filling in the details another “hurry up” prompt (saying “Don’t miss out!”) appears, and the user clicks the cross on it to make it disappear. During this process, the ticket price is displayed in the grey column on the left-hand side of the page. The “Price per Ticket” is still listed as AU$135.00. A “Secure Ticket Handling” fee of $4.95 has then appeared, and, without any other choice as to ticket handling offered, the “SUBTOTAL” line now reads “AU$139.95”. The words “+ Booking and VAT” appear below this figure, again in small grey lettering.

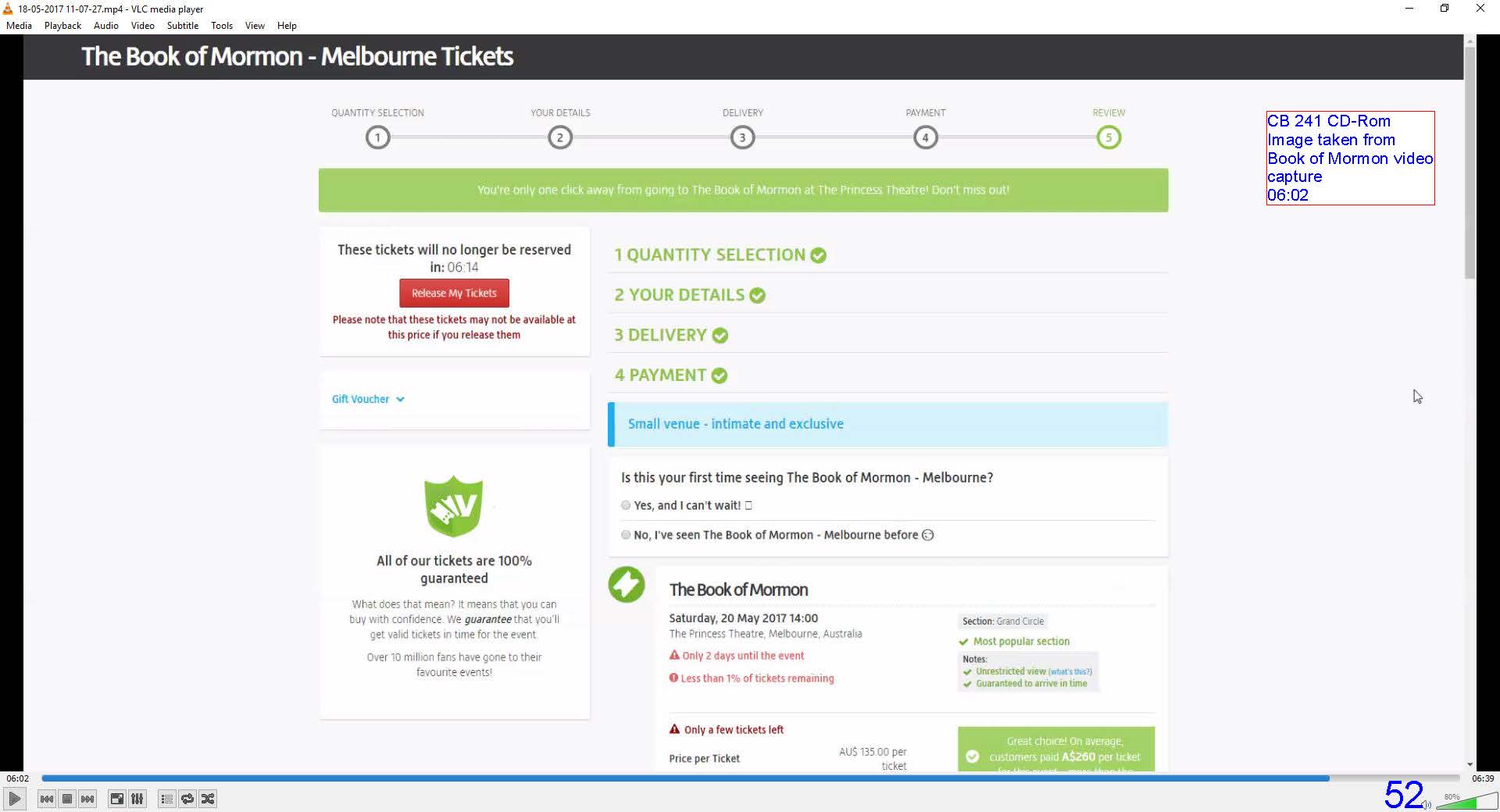

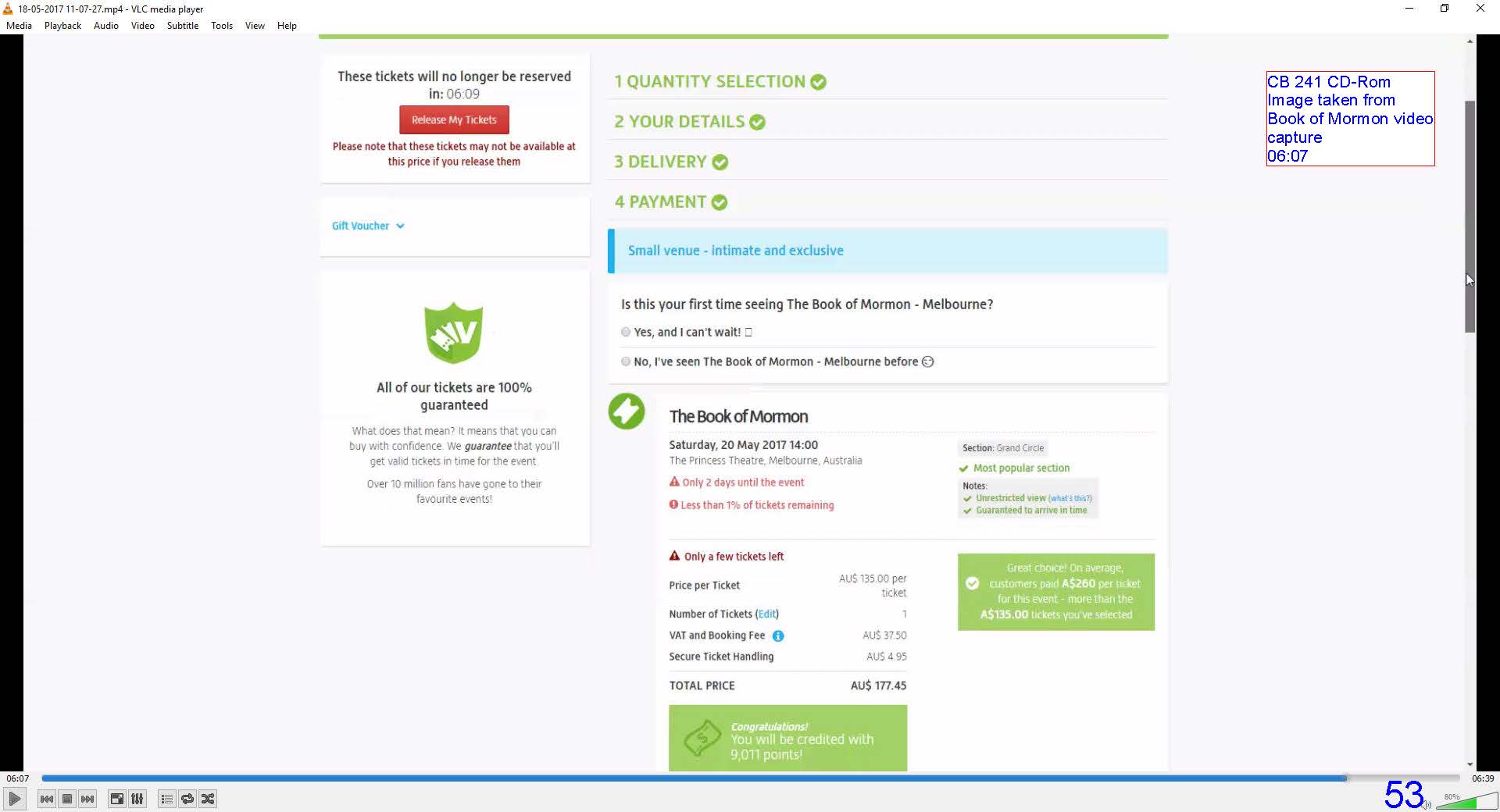

72 Following the completion of payment details and clicking “continue”, the site takes a few seconds before the Review Page appears. This is the final page in the booking process before purchase. The portion that is initially visible is as follows:

73 When one scrolls down, the details of the transaction are shown:

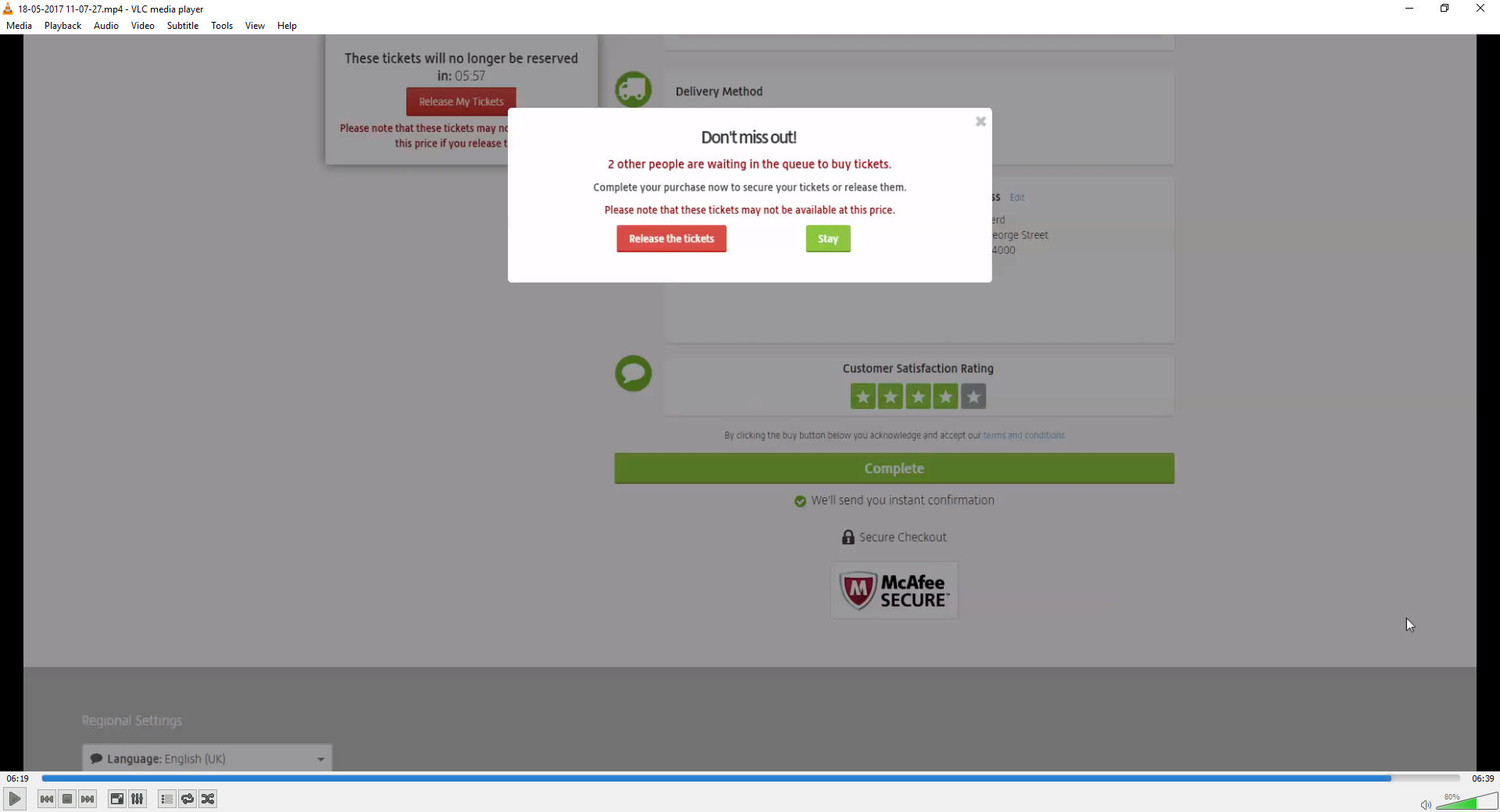

74 This is the first time the total payment required is displayed. A “VAT and Booking Fee” of $37.50 has been added and the price is now AU$177.45. The user scrolls down the screen to see a green bar-shaped button with the word “complete”. After a final “hurry up” (“Don’t miss out! 2 other people are waiting in the queue to buy tickets. Complete your purchase now to secure your tickets or release them. Please note that these tickets may not be available at this price”) the user is able to click “complete” to finalise the transaction. The “complete” bar is shown in the screenshot below (note that the screen is mostly covered by a grey wash, as another pop-up has appeared. This pop-up must be dismissed before the user could click on the “complete” bar).

3.4 General observations about the viagogo website

75 In section 3.3.2 above I have described the operation of the website. Each of the webpages is rich in information and provides access to additional information by clicking on links available. None of the pages can be seen in its entirety on a single screen of device likely to be used by the ordinary consumer. The consumer is directed to select links that meet his or her desire in terms of ticket acquisition. As one moves through the process, the website encourages, with increasing urgency, the consumer to advance through the acquisition so that the opportunity to acquire the desired tickets is not lost. This process has the effect, if not the design, of distracting the consumer from content that is available (or that might be available by following other links) beyond that which is immediately needed to progress through the site, and corralling him or her towards speedy completion of the purchase. The use of an interactive website is to be contrasted with other media by which goods or services are promoted and sold. In the present case the website serves the function of both promoting the sale of tickets and also enabling a consumer to enter the transaction. The consumer is drawn not only into a marketing web, but also into a transactional web. The site encourages the consumer to commit to a transaction; he or she selects the event of interest, then in the Tickets and Seating Selection Page is invited to choose the desired number of tickets and, once selected, commit (or at least signify an interest in doing so) to “Buy” them for a nominated price. At each stage the consumer is assured that tickets are running short, that time is running out to buy, and that the tickets that they have selected will soon be released to other, competing purchasers. The increasing urges to completion and the “hurry up” messages create such an impression that the consumer is at risk of missing out on tickets, that he or she is likely increasingly to confine attention to only that information necessary to enter details and complete the transaction.

4. THE EVIDENCE OF THE ACCC LAY WITNESSES

76 Set out below is a summary of aspects of the evidence of the ACCC lay witnesses. I have discussed above the legal principles applicable to the consideration of such evidence. Where appropriate, I indicate below my rulings on the remaining objections to admissibility of certain paragraphs.

77 Terrence Maurice Aherne is a retired former compositor for the Hobart Mercury Newspaper. On 7 May 2017 he conducted an internet search for tickets to attend the Ashes 2017-2018 cricket test series at the Adelaide Oval. Using the Google search engine, he typed the words “cricket test match tickets” or “day-night test tickets” into the search box. The first result at the top of the page that loaded contained the word “viagogo” and the word “official”.

78 Mr Aherne gives evidence that he cannot recall the exact wording, but that the result he saw contained words to the effect of “official ticket seller”. He had not heard of viagogo before. He wanted to secure the tickets quickly as he thought that the cricket test would be popular and might sell out. It was the first time Mr Aherne had bought tickets to any event online. He clicked on the result for viagogo.

79 Mr Aherne was then taken to the viagogo website, which had a list of events on it. He clicked on the listing for the cricket match and clicked on a listing displaying tickets for 4 December 2017. He then navigated his way through the website to acquire tickets. He states that he went through a number of pages during this process. He had to enter his contact details on one page, and entered his credit card details on another. He gives evidence that he did not see any prices listed for the tickets until he was close to the end of the booking process, at which point he saw the price of $553.90 for two tickets. He thought that this was a very high price and assumed it was the price for viewing all five days of the cricket test match. He assumed that the price would be readjusted once the website processed his order for only one day of the match. Mr Aherne does not recall seeing a “General Notes” section on the website. Nor does he recall seeing a statement to the effect that prices were set by sellers, or that prices exclude booking and delivery fees.

80 Once Mr Aherne had selected the tickets he wished to purchase, he noticed a “count-down timer”. At one point he remembers the timer displaying a time of three or four minutes. Mr Aherne also saw statements on the screen to the effect of “tickets are selling fast”. He thought these statements referred to all tickets available for the event, and states “I was worried that I would miss out on tickets”. He also states that he “tried to rush through the booking process as quickly as possible to secure tickets”.

81 After completing the booking process, Mr Aherne realised that he had paid $553.90. As noted, he had seen this price towards the end of the booking process, but he had assumed that it was the price for all five days of the cricket test match as it seemed too high. He states that if he had known that this was the total price when he started the booking process, he would not have proceeded with the purchase. He did not see anything on the viagogo Australian website stating that the tickets available were tickets which had been listed for re-sale. He thought that viagogo was the official, and only, ticket-seller.

82 Mr Aherne gives evidence in his affidavit of various steps that he took following the acquisition of the tickets, which by agreement between the parties was admitted subject to my consideration of its relevance in the context of the closing submissions (paragraphs 17, 18, 20, 45, and 47 of the affidavit). The objected to paragraphs (or parts thereof) concern what Mr Aherne did after he had completed the purchase of the tickets. In my view this evidence could rationally affect the assessment of the probability that Mr Aherne was misled by the content of the viagogo website (s 55 of the Evidence Act) and I admit it. However, as it concerns events that took place after he completed the purchase, I regard the weight to be attributed to it as slight, and diminishing significantly as it becomes more remote in time from the transaction.

83 Hazel Phyllis Bolding is a psychiatric nurse who gives evidence that on the evening of Monday 26 June 2017 she used her iPhone to conduct a Google search, using the search term “Book of Mormon tickets Melbourne”. She wished to attend the Book of Mormon theatre show on 29 June 2017. She recalls that the first result returned in the list of results contained the words “viagogo” and “official”, and thought that viagogo was the official seller for the Book of Mormon tickets. Ms Bolding could see the first 5 or so search results on the screen of her phone and could not see any results for Ticketmaster, which she understood to be a regular official seller of tickets to events generally. She assumed that viagogo was a company like Ticketmaster, being an official seller of tickets.

84 Ms Bolding then clicked on the first search result and was directed to the viagogo website, which had a heading “The Book of Mormon”. She states that she saw the word “resale” at the top of the page on the left hand side. She was “perplexed” as to why the website offered this facility, as she believed it to be the official site for tickets for the show. She then navigated her way through the website and acquired tickets. Ms Bolding states that the price listed was $153 per ticket. She did not see any warnings or disclosures on the website that additional fees would be charged, although she did expect to pay a small fee (between $2 and $8) for using her card to pay for the tickets. She does not recall seeing a section called “General Notes” on any of the pages.

85 Ms Bolding recalls that as she navigated through the booking process, several warnings appeared on the screen, stating that there were a certain number of tickets left for the event. She thought that these related to the number of tickets left for the Book of Mormon show on that evening. She states “I found the warnings distracting and they made me feel quite anxious … I felt as though I was running out of time to purchase the tickets”. She gives evidence that the warnings had to be closed by clicking on a cross in the top right-hand corner of the warning box.

86 Ms Bolding gives evidence that after she entered her credit card details, the website displayed a booking fee for the first time. She states that this fee was approximately $44 per ticket. Ms Bolding thought this was a considerable amount, and states that had she known from the outset that it would be applied, she would not have proceeded with the ticket purchase. By the time the booking fee was disclosed, she estimates that she had spent 15 to 20 minutes on the booking process. She recalls there being a countdown timer on the screen, and she was not sure whether she would have enough time to complete the purchase. She was worried that she would lose the tickets. Accordingly, she completed the purchase. The total price for the two tickets was $410.98.

87 Objection was taken to the whole or parts of paragraphs 13, 19, 23 and 24 of the affidavit of Ms Bolding and it was admitted subject to my consideration of their relevance in the context of the closing submissions. I admit the objected to portions of these paragraphs for the substantially the same reasons as I have admitted equivalent paragraphs in Mr Aherne’s affidavit, and subject to the same observations as to weight.

88 Victoria Helen Burke is a design coordinator who graduated from the University of Technology, Sydney with a Bachelor of Construction (Project Management) in 2013. She gives evidence that at about 8.50am on Friday 16 June 2017 she typed the words “London Grammar Sydney Opera House” into the Google search engine on her computer. She states that she wanted to buy tickets to the London Grammar (an indie pop band) concert at the Sydney Opera House. She knew that the tickets went on sale at 9:00am because she had received an email from the Sydney Opera House prior to purchasing tickets notifying her of the concert. She recalls that the first three results contained the word “viagogo” in them and the words “Official Site”, above a URL with the word “viagogo” in it. She had never heard of “viagogo” before, but understood from the words “official site” that viagogo was the official ticket-seller for the London Grammar concert.

89 Ms Burke then clicked on the link for the viagogo website and saw a heading at the top of the page that referred to the London Grammar tickets, with dates and locations for various London Grammar concerts. She clicked on the “view tickets” button for the date 25 September 2017. A page loaded, with words to the effect of “You have joined the queue, please wait”. After this, a page loaded showing the Sydney Opera House logo and a seating plan. Ms Burke states that she had previously studied the seating plan on the Sydney Opera House website and that the seating chart on the viagogo website appeared to be identical. Ms Burke had not seen a link on the Sydney Opera House website to buy tickets. This reinforced her belief that viagogo was the official ticket-seller for the concert.

90 Mr Burke saw that the price per ticket on the viagogo website was $258.29. She gives evidence that she did not see a heading saying “General Notes” or any terms and conditions on the website during the booking process. Ms Burke states that “all of the information on the Website made it appear to me as though Viagogo was the official seller of tickets” and “I recall thinking that the Website looked legitimate”. She gives evidence that seeing statements like “100% guaranteed” and “money back” made her feel comfortable using viagogo to book the tickets. Ms Burke saw several messages on the screen containing words to the effect of “about to sell out – only 30 tickets left” and other similar warnings. Electronic tickets were the only method by which tickets could be delivered for the event.

91 Ms Burke notes the presence of a countdown timer and states “I rushed through the booking process as quickly as I could because I thought that the Concert tickets were about to sell out”. Ms Burke states that just before she purchased the tickets, she noticed that the total charge was $665.03 for two tickets. She took a screenshot of the website at this point in the booking process, at 9:07am. She gives evidence that she did not notice additional fees being added to the cost of the tickets throughout the booking process. After purchasing the tickets Ms Burke received two emails from Viagogo.

92 In paragraphs 21 – 23 of her evidence Ms Burke records that she was surprised to see that there were no tickets attached to the second email and that it stated that her tickets would be available three days before the event. She also noticed that there was no row or seat number included in the email. This caused her to be suspicious that the tickets were not from what she described as a “legitimate ticket-seller” and were therefore not valid tickets. She then actively looked for viagogo’s Terms and Conditions, and found them. Ms Burke then went through the booking process again, as though she was going to purchase two new tickets. The purpose of this was to capture the booking process, although no screenshots of this repeated process were provided in evidence. During this repeated booking process, Ms Burke saw that there were references to additional fees and charges towards the end of the process, in small grey text. She gives evidence that she did not see those words while she was in the process of purchasing the tickets earlier that morning.

93 A relevance objection was taken to paragraphs 21 – 23. In my view those paragraphs reflect the contemporaneous reaction of Ms Burke to her purchase of the tickets. I consider them to be relevant and admissible. Furthermore, despite the objection, in its submissions viagogo relies upon the evidence of Ms Burke as to the content of the terms and conditions.

94 On 28 August 2017, Ms Burke entered the search term “London Grammar Sydney Opera House” into the Google search engine and took a screenshot of the of the result which appeared on the screen. She gives evidence that it was very similar to the results which came up on the search she had carried out on 16 June 2017. A relevance objection was taken to this evidence, and also to the evidence in paragraph 42 of her affidavit, on the basis that the screenshots identified were taken outside the relevant period, but consistent with my finding in relation to the screenshots taken by Ms Werry, and the evidence of Ms Burke linking the content of the screenshot with what she saw, I admit the evidence. The screenshot displays two results, each with “Ad” marked before the URL. The first result is for viagogo. It reads “London Grammar Tickets 2017 - Buy Now, viagogo Official Site”. The second result is for the Sydney Opera House.

95 Relevance objections were taken to the whole or portions of paragraphs 27, 32, 33 and 38 – 41. For the reasons given in relation to an equivalent objection taken to the evidence of Mr Aherne, I admit those paragraphs and make the same observation as to the weight to be given to them.

96 Bruce Alan McDowell is a retired economist and administration officer. On 4 June 2017 he typed “Australian Open tennis tickets” into the Google search engine. The first result was a listing for viagogo which he also recalls included the words “official site”. He realises now that this was an advertisement, but at the time did not think that it was. He looked at other search results that were listed below the viagogo one, but considered that they appeared to be suspicious. He gives as an instance that he saw a listing for “Ticketmaster Resale”, which he understood to be a site that resold tickets. He clicked on the link for viagogo and looked at the site. He had never heard of viagogo, so he logged onto the Tennis Australia website to see if tickets were available there, but they were not. He gives evidence that he thought that Tennis Australia must be selling tickets to the event through an agent, and because the viagogo listing had the words “official site” in it, he thought that it was the official website authorised by Tennis Australia to sell the tickets to the Australian Open. He thought that the website looked “professional and legitimate”, and similar to other websites he had purchased official tickets from in the past.

97 Mr McDowell then navigated through the viagogo website to acquire tickets. He saw words to the effect of “1% left” displayed next to each block of seats on the seating map, which he took to be a reference to the percentage of tickets available for the event. Mr McDowell does not recall seeing a “General Notes” section, nor any statement to the effect that “prices are set by sellers and may be lower or higher than face value”. He does not recall seeing or looking for terms and conditions on the website, although he states that it is his usual practice to do so. He saw a countdown timer on the website, as well as various messages such as “only a few tickets left”. He states that he was worried he would miss out on tickets, and tried to move through the booking process as quickly as possible.

98 Mr McDowell did not know that the tickets had been re-sold, and did not see any information on the viagogo website indicating that the tickets were re-sold. He gives evidence that he would not have purchased the tickets if he had known this fact.

99 During the booking process, Mr McDowell saw references to extra fees being payable, but states that the amount of these fees was not disclosed until after he had entered his contact details and credit card details. The final amount of $581.50 for two tickets “came as quite a shock” to him.

100 After buying the tickets, he received two emails from viagogo one of which informed him that the tickets would not be provided to him until 3 days before the event. He became concerned because at that time he would already be on a cruise (which he had booked to coincide with the tennis). Mr McDowell became concerned that the tickets were not legitimate, and that viagogo did not actually have his tickets. He wrote an email to viagogo on 9 June 2017.

101 Relevance objections were taken to the whole or portions of paragraphs 18, 21, 23 and 24 of Mr McDowell’s affidavit. For the reasons given in relation to an equivalent objection taken to the evidence of Mr Aherne, I admit those paragraphs and make the same observation as to the weight to be given to them.

102 Susan Lynne Symons is a registered midwife and nurse. On 21 June 2017 she conducted a search using the Google search engine on her tablet computer for tickets to a Queen and Adam Lambert concert to be held at Qudos Bank Arena in Sydney on 21 February 2018. She recalls that she entered the search terms “Queen Australia Adam Lambert”, and that the first result which appeared contained the words “viagogo official site” and that the URL of the site included the word “viagogo”. Ms Symons thought that the words meant that viagogo’s website was the official site at which tickets to the event were sold. She had never heard of viagogo before but thought that it was a similar company to Ticketmaster, which she had used to buy tickets in the past. She thought that viagogo sold tickets which “it issued itself, not tickets sold by previous purchasers of tickets from other sources”. She gives evidence that if she had known the tickets were re-sold, she would not have purchased them from viagogo.

103 Ms Symons clicked on the link to the viagogo website and then navigated her way through it to acquire tickets. At one point in the process, a message appeared on the screen informing her that she had joined the queue to buy tickets. Ms Symons recalls that this made her think that tickets were in high demand. A screen then loaded with a seating chart, where the word “Sold” popped up next to certain seats while she was looking at the chart.

104 Ms Symons does not recall seeing a “General Notes” section, nor does she recall seeing words to the effect of “prices are set by sellers and may be higher or lower than face value. Prices exclude booking and delivery fees”. The initial price displayed for the tickets was $166.50 per ticket. Ms Symons recalls that as she proceeded through the booking process, messages appeared on the screen containing phrases such as “only a few tickets left” or “tickets for this event are selling fast”. She thought this referred to the total amount of tickets remaining for the concert. A countdown timer also appeared on the screen. Ms Symons gives evidence that “I thought that if I did not purchase the tickets quickly, I would miss out”.

105 Ms Symons gives evidence that she did not notice the total cost of the tickets change until after she had entered her contact details and credit card details and the sale was processing. It was then that she saw the final price of $1,068.70 for five tickets (which amounts to a price of $213.74 per ticket). That evening, Ms Symons used her mobile phone to search for “queen australia adam lambert”, and used the phone to take a screenshot of the results. A copy of that screenshot is reproduced in paragraph [35] above. Ms Symons gives evidence that the first result had the same appearance as the one she saw on her tablet earlier that day, when she was looking for tickets.

106 After purchasing the tickets Ms Symons received two emails from viagogo. She downloaded the viagogo app that was promoted in those emails, expecting that she would be able to download her recently acquired tickets. She thought that she had been charged too much for her tickets and looked through the viagogo website “FAQs” to find some general information about viagogo. On 17 July 2017 Ms Symons received an email from viagogo notifying her that the tickets were available to her for download. When she printed them out she noticed that they had been issued by Ticketek and had a price of $106.95 printed on each of them.

107 A relevance objection was taken to the whole or portions of paragraphs 20, 23, 24, 25 and 27 of the affidavit. For the reasons given in relation to an equivalent objection taken to the evidence of Mr Aherne, I admit those paragraphs and make the same observation as to the weight to be given to them.

108 There is no dispute between the parties that despite viagogo being a foreign corporation within s 4 of the CCA, this court has jurisdiction to determine the present dispute. The court’s jurisdiction arises from s 138(1) CCA and s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), see Valve v ACCC [2017] FCAFC 224; 351 ALR 584 (Dowsett, McKerracher and Moshinsky JJ) at [134].

109 I have noted above the considerations that must be taken into account when there is a class of consumers to whom a representation is addressed. The viagogo ad and the viagogo website are directed to members of the public at large who have an interest in acquiring tickets online for live events. The representations contained within them must be judged by their effect on ordinary or reasonable members of that class of prospective purchasers. Consideration of these matters is to be as at the date of the alleged representations, which is during the relevant period.

110 The parties were in broad agreement as to characteristics of the ordinary class of consumers likely to read and respond to the alleged representations. Such persons would reasonably be expected to possess knowledge and familiarity with the internet and conducting searches online and navigating web pages. They would have an understanding of purchasing items on the internet, although not necessarily any specialised knowledge of the online acquisition of tickets for live events. In my view, such persons would know that they can purchase tickets online, but not necessarily have great (or indeed any) familiarity with the process.

111 It is not in dispute that they are not likely to have been aware of viagogo or that it operates a ticket marketplace for the re-sale of tickets for events.

112 The ACCC submits that in purchasing tickets through an electronic interface, consumers would not ordinarily engage in prolonged deliberation and one would not expect consumers to attend closely to every word on a webpage, to click on links which were not necessary for the process, or to scroll down the webpage beyond what was necessary to proceed with the purchase. Viagogo disputes this proposition and submits that the cost of the tickets acquired is significant and where, as is likely, a consumer has not previously encountered viagogo, he or she would be careful to investigate and ensure that they are acquiring tickets for their preferred event and “to ensure they understand who the company is that they are buying tickets from”. In my view the price of the tickets being acquired is not insignificant and in that sense an ordinary consumer would be expected to approach the acquisition with some care; Parkdale at [9] (per Gibbs CJ). However, the degree to which a consumer might closely attend to every word on a webpage and click on links or scroll down the webpage depends on the specific context of the search and matters such as the prominence and apparent relevance of the link and the general impression conveyed by the webpage. The urgency attached to purchasing tickets to a popular event may also militate against the consumer taking the time to carefully consider and investigate the website. These are matters that are best considered in the context of an examination of the particular media in which the alleged misrepresentations occurred, rather than being the subject of generalisation. However, I agree that in the context of the viagogo website the ordinary consumer is not likely to read every word on a webpage or click on every link.

113 I refer below to a person with the characteristics that I have found above to be applicable as the ordinary consumer.

114 The ACCC lay witnesses acquired their tickets using different devices which I find are typical of the type of devices likely to be used. Ms Bolding searched on a mobile phone, Ms Simons on a tablet computer and Mr Aherne, Ms Burke and Mr McDowell used personal computers – it is not clear whether they were laptops or desk top devices. Naturally enough, the difference in device will affect the size of the screens available to look at the website. From my own observations of the evidence, including the video captures of Mr Shepherd and Mr Tran, I find that the user is likely to need to scroll down to read the contents of each page in a similar manner to that described in section 3.3.2 above.

5.3 The relevance of the evidence of the ACCC lay witnesses

115 Each of the ACCC lay witnesses gives evidence about how they accessed the viagogo website, what they did to purchase tickets, and what they thought about it. Their evidence is not determinative, but may be of assistance in identifying and assessing the characteristics of the ordinary consumer and, as the authorities above indicate, potentially his or her response to the alleged representations.

116 Viagogo submits that the evidence of these witnesses should be disregarded because they made “extreme and fanciful assumptions”, which representatives of the reasonable member of the representative class would not make. It submits that four of the five consumers had pressing factors at the forefront of their minds in purchasing tickets and that one ought to have known that viagogo was not an authorised seller. Viagogo submits that all were persons who failed to take reasonable care of their own interests, for whom the prohibitions in s 18 ACL were not enacted, citing TPG Internet at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

117 I reject these criticisms. The “pressing factors” identified by viagogo were: that Ms Symonds was responsible for buying tickets for herself and 4 friends; Ms Bolding was purchasing for herself and her niece who was keen to see the Book of Mormon; Mr McDowell had already booked a 5 night cruise from Sydney to Melbourne to coincide with the tennis and so was eager to make the purchase; and Mr Aherne had already purchased airfares to Adelaide. These are mundane circumstances of the type in which persons would typically find themselves buying tickets to an event. They are likely to represent the sort of motivation that leads a person to buy tickets either for themselves or for others. None of these witnesses gave evidence that they were impaired in their ability to read or comprehend the results of their Google searches by reason of that motivation. They were not cross examined, no doubt for the very sound reason that such “factors” as viagogo identifies are hardly likely to lead a consumer to abandon his or her own interests or to be so distracted from the task of acquiring the tickets that they fail to give proper attention to the matters before them.

118 In the case of Ms Burke, viagogo submits that she reasonably should have known that viagogo was not the permitted seller. In this regard, the evidence of Ms Burke is that she was first informed of the availability of the London Grammar tickets by email from the Sydney Opera House. She clicked on a “find out more” link in the email which took her to a web page where she saw the price per ticket as being about $120. For the purpose of her affidavit she revisited the website and printed off the relevant pages of the website. On the last of these pages the website has a heading “Frequently Asked Questions” which states that the only authorised agency for the event is the Sydney Opera House, and that only tickets purchased by authorised agencies should be considered valid and reliable. It says that “[t]ickets purchased from Ticketmaster Resale, viagogo… or any other unauthorised re-seller may be cancelled without notice and/or the holder may be refused admission to the event”. Viagogo submits that Ms Burke and indeed all of the ACCC witnesses ought to have informed themselves of these facts in order to look out for their interests.

119 I accept that Ms Burke had the opportunity, by looking into the detail of the Sydney Opera House website and following through to the Frequently Asked Questions, to see that the Sydney Opera House was the only authorised ticket seller for the event, and that viagogo was not. But no evidence suggests that she did so, and she was not cross-examined on the subject. Accordingly, it appears that she approached her acquisition of the London Grammar tickets with the same naivety that viagogo accepts should apply to the ordinary consumer, and which the evidence indicates applied to all of the ACCC lay witnesses, namely she was not aware of the activities of viagogo or that it was a re-seller of tickets.

120 Accordingly, subject to the application of the appropriate limits to which the evidence of individual witnesses may be of assistance in a case such as the present, the evidence of the ACCC lay witnesses has the potential to strengthen the inference that the conduct is misleading and deceptive; see Section 2.2 above and Verrocchi, first instance at [93]-[94].

5.4 The Official Site Representation

121 The ACCC seeks a declaration that during the relevant period, viagogo, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of services:

(a) by using the word “Official” in its advertisements on Google, and

(b) by failing to disclose, or adequately disclose that it was not a primary ticket seller,

represented to consumers that:

(c) they could purchase official original (i.e. not resold) tickets through the viagogo website; and/or

(d) viagogo had approval from, or was affiliated with the relevant team, musician, entertainer or event promoter, organiser or venue (host) as an “official” agent of the host to sell original (i.e. not resold) tickets to the host’s events directly to the public;

when, in fact:

(e) the tickets available from the viagogo website were being resold via an online secondary ticketing platform, and/or

(f) viagogo did not have any such affiliation or approval;

and thereby: