FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Limited v Redbubble Limited [2019] FCA 355

File number(s): | QUD 902 of 2015 |

Judge(s): | GREENWOOD J |

Date of judgment: | 15 March 2019 |

Catchwords: | COPYRIGHT – consideration of whether copyright continues to subsist in an artistic work described as the “Membership Card image” authored by a United States citizen in the United States of America in 1954 COPYRIGHT – consideration of whether the 1954 work authored by a man by the name of “Sundown” is an anonymous work or a pseudonymous work – consideration of whether the relevant corporation in the United States of America is the owner of the copyright subsisting in the work in suit – consideration of the evidence and statutory provisions going to the question of whether that corporation is the owner of the copyright work in suit having regard to the application of the domestic copyright law of Australia COPYRIGHT – consideration of whether the applicant is an exclusive licensee of the contended grantor of the exclusive licence having regard to the integers of the term “exclusive licensee” in s 10(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) COPYRIGHT – consideration of whether a work described as the “Fuki current Death Head design” is a derivative work and whether copyright subsists in it independently of the “Membership Card image” COPYRIGHT – consideration of whether the first respondent has exercised any one of the relevant exclusive rights of the copyright owner on the assumption that ownership of the copyright as contended is made out TRADE MARKS – consideration of whether the applicant is an authorised user of the trade marks in suit having regard to the integers of s 8 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) TRADE MARKS – consideration of whether the first respondent has infringed the registered trade marks in suit having regard to the elements of s 120(1) and s 120(2) of the Trade Marks Act – consideration of the question of damages and exemplary damages TRADE MARKS – consideration of a cross-claim by the first respondent for an order directing the Registrar of Trade Marks to remove the registered trade marks of Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation of the United States from the Register INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – consideration of whether the applicant has standing to bring the proceedings |

Legislation: | Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), ss 10(1), 14(1)(a), 22(6), 22(6A), 24, 29(1)(a), 29(3), 31(1)(b)(i), 31(1)(b)(iii), 32, 33, 34, 36, 101(1A), 119, 210, 213(2), 213(4), 213(8), 239 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), ss 7(3), 7(4), 7(5), 8(1), 8(2), 8(3), 17(3), 26(1), 26(2), 92(3), 92(4)(b), 100(1)(c), 120(1), 120(2) Australian Consumer Law, ss 18, 29 |

Cases cited: | Australian Performing Right Association Ltd v Canterbury-Bankstown League Club Ltd (1964) 81 WN Pt (1) (NSW) 300 Enzed Holdings Ltd v Wynthea Pty Ltd (1984) 4 FCR 450 Ernest Turner Electrical Instruments Ltd v Performing Right Society Ltd [1943] Ch 167 Google Inc. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 Heidelberg Graphics Equipment Ltd v Andrew Knox & Associates Pty Ltd (1994) ATPR 41-326 International Harvester Company of Australia Pty Ltd v Carrigan’s Hazeldene Pastoral Company (1958) 100 CLR 644 Jennings v Stephens [1936] Ch 469 Lodestar Anstalt v Campari America LLC (2016) 244 FCR 557 Performing Right Society Ltd v Harlequin Record Shops Ltd [1979] 1 WLR 851 Pioneer Kabushiki Kaishai v Registrar of Trade Marks (1977) 137 CLR 670 Ramset Fasteners (Aust) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd (1999) 164 ALR 239 Rank Film Production Ltd v Dodds [1983] 2 NSWLR 553 Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Limited (2012) 248 CLR 42 Telstra Corporation Limited v Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (1997) 191 CLR 140 The Koursk [1924] P 140 The Shell Company of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Limited (1963) 109 CLR 407 Thompson v Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 574 University of New South Wales v Moorhouse (1975) 133 CLR 1 WEA International Inc. v Hanimex Corporation Ltd (1987) 17 FCR 274 Winstone v Wurlitzer Automatic Phonograph Co of Australia Pty Ltd [1946] VLR 338 |

25 September 2017, 26 September 2017, 27 September 2017, 28 September 2017 and 29 September 2017 | |

Date of last submissions: | 15 February 2018 |

Registry: | Queensland |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Copyright and Industrial Designs |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | 552 |

Solicitor for the Applicant/Cross Respondent: | Solus IP Pty Ltd |

Counsel for the First Respondent/Cross Claimant: | Mr R Cobden SC with Ms E Bathurst |

Solicitor for the First Respondent/Cross Claimant: | Allens Linklaters |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 MARCH 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant submit to the Court within 10 days proposed orders giving effect to the reasons for judgment published today.

2. Costs are reserved for later determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GREENWOOD J:

Background and introduction to the issues

1 In these proceedings, the applicant Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Limited (“HAMC Aust” or the “applicant”) takes issue with the conduct of the respondent, Redbubble Ltd (“Redbubble”) arising out of, put simply, the contended structure, method of operation, functionality and outcomes generated when persons (otherwise called “artists”), and consumers (otherwise called “buyers”) engage with Redbubble’s website ([Web] redbubble.com) (the “Redbubble website”).

2 The Redbubble website enables an artist (or for that matter, a non-artist who might simply be a person seeking to appropriate another person’s works or trade marks for commercial gain, subject to Redbubble’s contended protocols governing the operation of the website so as to manage the conduct of such persons), to upload an image, drawing, photograph, design, name, mark or sign or any other expression of creative (or non-creative) work to the website. The artist nominates the class of goods to which the work can be applied (selected from Redbubble’s pre-determined list of available products, for example, T-shirts, caps, mugs) and the website enables consumers to search, by tags or keywords, and transact so as to order and pay for, through the website, a selected article bearing the work.

3 The Redbubble website causes a third party fulfiller to be appointed (from a panel preselected by Redbubble) to fill the order by applying the image (or relevant subject matter) to, for example, a mug or a T-shirt.

4 The functionality of the Redbubble website also enables the despatch and delivery of the article with the work applied as ordered, to the buyer’s nominated address.

5 Redbubble says that it acts as the “agent of the artist” in enabling the transaction through its website. Redbubble says that in doing so, and in operating the Redbubble website generally, it is simply providing an open, online, electronic marketplace where artists and consumers can engage and transact with one another.

6 It will be necessary in these reasons to examine the evidence going to the structure, functionality and operation of the Redbubble website in some detail. That is especially so because Redbubble says that the entire functionality of its website is effected by software located on servers in the United States of America. Redbubble says that the uploaded images are stored on servers in the United States and all commands giving effect to a step taken by an artist to, for example, upload an image or relevant subject matter to the site, or a consumer to transact, takes place in the United States and not in Australia.

7 HAMC Aust contends that by reason of the manner and method of operation of the Redbubble website, Redbubble has infringed the copyright said to be subsisting in two artistic works; infringed certain registered trade marks; and engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law (the “ACL”). Apart from contentions of direct infringement, HAMC Aust says, in the alternative, that Redbubble has authorised infringements of the copyright in the relevant works by others (artists) and has engaged in a “common design” with artists in bringing about the infringement of copyright so as to render Redbubble and the artists joint tortfeasors.

8 As to the precise conduct said to constitute the copyright infringements, the applicant contends (as articulated more precisely in closing oral addresses) that the critical complaint (the “case”) is that Redbubble has engaged in a direct infringement of the copyright in the two works (s 36(1), Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the “Copyright Act” or the “1968 Act”) by, in Australia, “communicating the work to the public” within the meaning of s 31(1)(b)(iii) of the Copyright Act. That is said to follow because Redbubble is said to have made the relevant work in suit “available online” for the purposes of the definition of the term “communicate” in s 10(1) of the Copyright Act. Alternatively, Redbubble is said to have authorised the conduct of the artist in making the work available online by uploading an image or relevant subject matter and has thus authorised an infringement by the artist.

9 Redbubble contends that the applicant has failed to identify precisely, in terms of the technology, the point on the continuum when an infringing step occurs so as to test the authorisation principles against the infringement said to have been authorised.

10 HAMC Aust says that Redbubble and the artists are joint tortfeasors in the trade mark infringements. The applicant also says that Redbubble has authorised trade mark infringements by the artist.

11 It will, of course, be necessary to examine the precise statutory integers of the relevant conduct and the application of those integers to the facts.

12 HAMC Aust is neither the owner of the copyright said to subsist in the two copyright works in suit, nor the registered owner in Australia of the relevant trade marks in suit.

13 HAMC Aust says that it derives its standing to sue as the exclusive licensee in Australia of the copyright owned by the second respondent, Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (US) (“HAMC US”). HAMC US is the registered owner in Australia of the trade marks in suit in these proceedings. HAMC Aust says that it is the authorised user in Australia of the relevant marks.

14 The rights of HAMC Aust in the copyright and the relevant trade marks are said to derive from an agreement dated 14 May 2010 between HAMC US and HAMC Aust in which the grant of rights is described as “an exclusive non-transferable licence” to use the marks and copyright subsisting in works substantially identified in the relevant trade marks. Redbubble contends that a proper analysis of the agreement, taken in conjunction with evidence of the way in which HAMC Aust engages with HAMC US concerning use of the copyright works (particularly having regard to the definition of the term “exclusive licensee” in s 10(1) of the Copyright Act), and the trade marks (having regard to the definition of “authorised user” and “authorised use” in s 8 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (“Trade Marks Act”), suggests that HAMC Aust is neither an exclusive licensee of the copyright nor an authorised user of the trade marks.

15 Redbubble says that the proceedings should be dismissed on that ground alone.

The copyright works

16 As to the copyright, the works relied upon by the applicant are these.

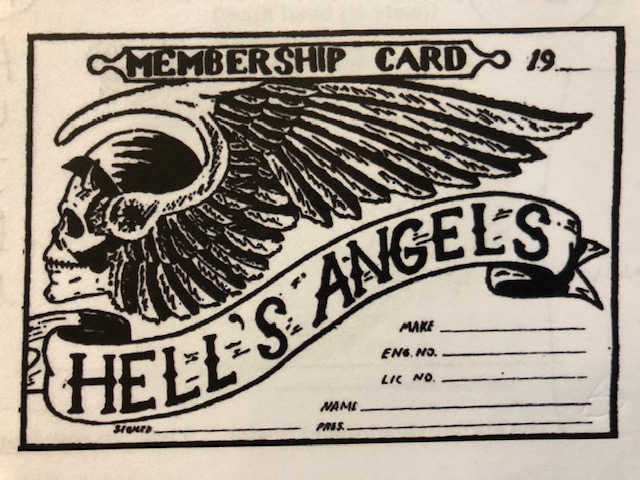

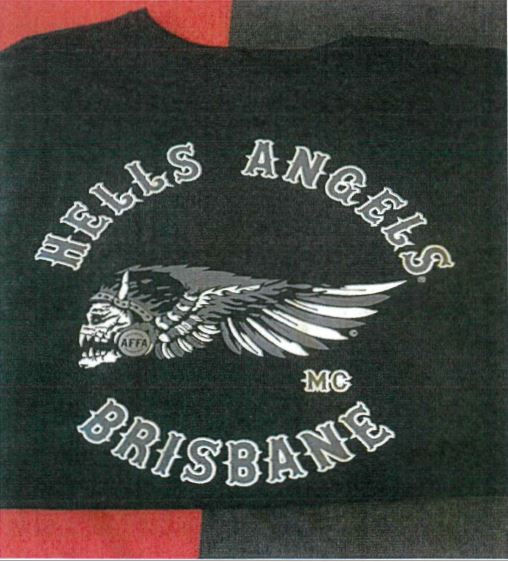

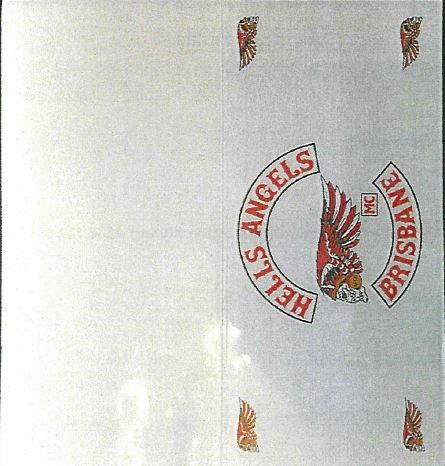

17 First, an artistic work (in respect of which there is no challenge to the originality of the work) depicting a skull in profile wearing a motorcycle helmet adorned with exposed feathers in the form of a wing or headdress described as the “Membership Card image” or “Membership card”. The image is depicted below.

18 The applicant says that the Membership Card image is a work commissioned by the “San Francisco Chapter” of the Hells Angels Club (as explained later in these reasons) on 2 September 1954. The author is a man called “Sundown”. He is said to have been a resident of San Francisco at the time of authorship of the image. He is said to be Robert D. Kestner (also spelt “Kistner”). The applicant says that the work was “completed” in 1954. The applicant says that HAMC US is the owner of the copyright subsisting in the Membership Card image although the applicant accepts that there is no assignment (or no evidence of an assignment) in writing vesting the legal title to the copyright in HAMC US.

19 It will be necessary to examine the chain of title to the work starting with “Sundown” as the author of the work in 1954.

20 As to the question of whether copyright continues to subsist in the Membership Card image, issues arise in relation to s 34 of the Copyright Act. Section 34, as it stood prior to the commencement of the United States Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act 2004 (Cth) (the “Free Trade Implementation Act”) (which had the effect of, among other things, extending the term of a relevant work from 50 years to 70 years), provided:

(1) Subject to subsection (2), if the first publication of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is anonymous or pseudonymous, any copyright subsisting in the work by virtue of this Part continues to subsist until the end of the period of 50 years after the end of the calendar year in which the work was first published.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply in relation to a work if, at any time before the end of the period referred to in that subsection, the identity of the author of the work is generally known or can be ascertained by reasonable inquiry.

[emphasis added]

21 As to s 34, the following questions arise.

22 The question of whether copyright subsists in an original artistic work published or unpublished and the term or duration of that subsistence falls to be determined by Part III of the Copyright Act having regard to, relevantly, ss 32, 33 and 34. However, s 210 of the Copyright Act, contained within Part XI, which addresses transitional matters, provides that notwithstanding anything in Part III, copyright does not subsist by virtue of that part in a work (relevantly here, an artistic work made in 1954) first published before the commencement date of the Copyright Act (which commenced on 1 May 1969) unless copyright subsisted in the work under the Copyright Act 1911 immediately before the commencement of the 1968 Act.

23 If copyright did so subsist, it continues to be governed by Part III.

24 The Free Trade Implementation Act commenced operation on 1 January 2005. Thus, 31 December 2004 is a material date. Section 33 (which has effect “subject to s 34”; s 33(1)), prior to 1 January 2005, provided that copyright in an artistic work continued to subsist until the expiration of 50 years after the end of the calendar year in which the author of the work died. Section 34, however, provided prior to 1 January 2005, that if first publication of an artistic work occurred anonymously or pseudonymously, any copyright subsisting in the work by reason of Part III would continue to subsist until 50 years after the end of the calendar year in which the work was first published (on the apparent assumption that it would not be possible in respect of such a work to determine the date of death of the author and thus determine the term under the “end of the life of the author plus 50 years” rule (the “primary rule”)).

25 If Sundown’s work was first published anonymously or pseudonymously prior to 31 December 1954, the subsistence of copyright in the work ended on 31 December 2004. However, even though a work might be published anonymously or pseudonymously, a circumstance might arise at some point in the period between the end of the calendar year of first publication and 50 years, in which the identity of the author becomes generally known, in which event the primary rule would operate.

26 Another circumstance might be that even though the author is not generally known, his or her identity “can be ascertained by reasonable inquiry”. In that circumstance, the primary rule would also apply.

27 In either of those circumstances, s 34(2) has the effect of displacing the operation or application of s 34(1) with the result that the duration of the subsistence of any copyright falls to be determined in accordance with s 33. From 1 January 2005, the term became, under the primary rule, the end of the calendar year in which the author of the artistic work died plus 70 years.

28 Assuming that s 34(1) “applied” (at a time prior to 1 January 2005) to the Sundown work, copyright ceased to subsist in the work at 31 December 2004 and did not therefore enjoy the benefit of the statutory changes on 1 January 2005. Questions of fact become: When was the Sundown work first published? Was it published anonymously or pseudonymously? In the relevant period contemplated by s 34(1), was the identity of the author generally known or could it have been ascertained by reasonable inquiry?

29 Redbubble says that the work was published in 1954 because reproductions of the work were supplied “to the public” between 9 September 1954 and 31 December 1954, for the purposes of s 29(1)(a) of the Copyright Act.

30 If first publication occurred in 1954 a question arises as to whether at any time in the period ending 31 December 2004 the identity of Sundown was generally known or could have been ascertained by reasonable inquiry. If so, s 34(1) as it stood had no application and the term of the copyright would not have expired on 31 December 2004. Redbubble says that Sundown’s identity was not generally known in the period contemplated by s 34(1) and his identity could not have been ascertained by reasonable inquiry. The applicant contends otherwise and says that s 34(1) has no application.

31 Other aspects of the factual matrix going to this issue are in contest.

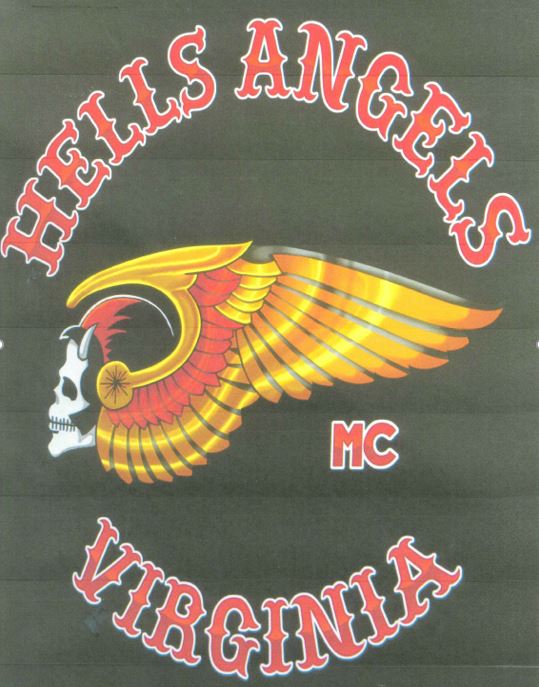

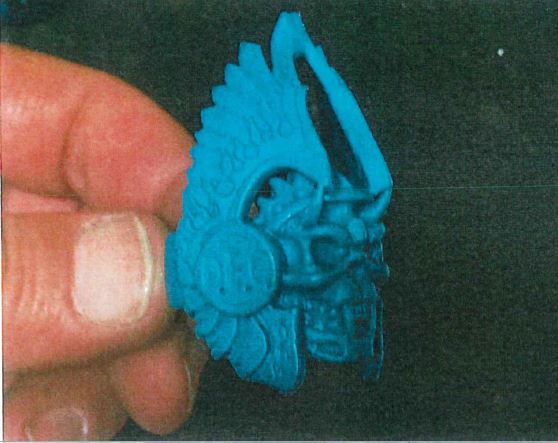

32 The second copyright work is an artistic work described as the “current Death Head design”, the author of which is Mr John Makato Fukushima, known as “Fuki”.

33 In the pleading, the applicant describes the work as “enhancements to the winged skull image” appearing on the Membership Card: para 11A. It is said to have been made or “created” in 1983 and first published in the United States in 1983. The author at the time of authorship was a United States citizen resident in the United States.

34 The applicant says that by agreement between HAMC US and Fuki, the copyright in the current Death Head design was to be owned by HAMC US. Mr Fukushima assigned the ownership of the copyright in the current Death Head design to HAMC US in writing on 16 September 2015. However, he inadvertently attached the wrong image to the assignment document. A fresh assignment was signed by him on 29 March 2017 correcting the attachment. Mr Fukushima’s current Death Head design is depicted below.

35 Redbubble says that the applicant has not established any originality in the current Death Head design and it is true to say that in the closing address on behalf of the applicant, counsel effectively abandoned any reliance upon contentions of copyright subsistence in this work as a separate work.

36 However, the matter has not been abandoned by the applicant.

37 As to the trade marks in suit, the applicant relies upon the following trade marks registered in Australia in the name of HAMC US having regard to the classes in Schedule 1 to the Trade Mark Regulations in each case:

(a) Trade Mark 526530 registered in Class 16 for the following words/image:

(b) Trade Mark 723219 for the words “HELLS ANGELS” registered in Classes 14, 16, 25 and 26.

(c) Trade Mark 723463 registered in Classes 14, 16, 25 and 26 for the following image:

(d) Trade Mark 1257992 for the words “HELLS ANGELS” registered in Classes 14, 16, 25 and 26.

(e) Trade Mark 1257993 for the following image registered in Classes 14, 16, 25 and 26:

38 Trade Mark Registrations 526530, 723463 and 1257993 contain a depiction of either the Membership Card image or the Fuki current Death Head design. Trade Marks 723219 and 1257992 consist simply of the words “Hells Angels”.

39 As to Trade Mark 526530, it was registered with effect from 8 January 1990 in respect of printed matter; book binding material; photographs; printers type in Class 16 of Schedule 1 to the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (the “Regulations”).

40 As to Trade Mark 723219, it was registered with effect from 2 December 1998 in respect of the following goods:

(i) in Class 14 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Jewellery, precious stones, watches and clocks, rings, metal badges and belt buckles in this class”;

(ii) in Class 16 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Printed matter including magazines, pamphlets and brochures, labels in this class, flags in this class, instructional and teaching material (except apparatus), playing cards, stationery including pens and posters”;

(iii) in Class 25 of Schedule 1 of the Regulations: “Clothing including leather belts and jackets, footwear and headgear; headbands and armbands not being made of leather and being goods in this class”;

(iv) in Class 26 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Badges and belt buckles not being made of precious metal; embroidered and cloth material badges for attachment to clothing and headgear”.

41 As to Trade Mark 723463, it was registered with effect from 5 December 1996 in respect of the following goods:

(i) in Class 14 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Jewellery, precious stones, watches and clocks, rings, metal badges and belt buckles in this class”;

(ii) in Class 16 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Printed matter including magazines, pamphlets and brochures, labels in this class, flags in this class, instructional and teaching material (except apparatus), playing cards, stationery including pens and posters”;

(iii) in Class 25 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Clothing including leather belts and jackets, footwear and headgear”;

(iv) in Class 26 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Badges and belt buckles not being of precious metal, embroidered and cloth material badges for attachment to clothing and headgear, headbands and armbands not being of leather”.

42 As to Trade Mark 1257992, it was registered with effect from 11 July 2008 in respect of the following goods:

(i) in Class 14 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Jewellery, goods in precious metal, clocks and watches, earrings, keyrings, badges, chains, pins”;

(ii) in Class 16 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Printed matter, newspapers, periodical publications, books, photographs, stationery and adhesive materials (stationery); paper, cardboard, paper articles and cardboard articles, bookbinding material, artists’ materials, paint brushes, ordinary playing cards; printers’ type and clichés (stereotype); all included in this class”;

(iii) in Class 25 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Articles of clothing, footwear and headgear, including coats, jackets, trousers, overalls, shirts, pullovers, sweaters, hats, vests, waistcoats, cardigans and belts (for wear)”;

(iv) in Class 26 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Badges, belt clasps, lace and embroidery, buttons, headwear ornaments, patches for repairing textile articles, pins and needles”.

43 As to Trade Mark 1257993, it was registered with effect from 11 July 2008 in respect of the following goods:

(i) in Class 14 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Jewellery, goods in precious metal, clocks and watches, earrings, keyrings, badges, chains, pins”;

(ii) in Class 16 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Printed matter, newspapers, periodical publications, books, photographs, stationery and adhesive materials (stationery); paper, cardboard, paper articles and cardboard articles, bookbinding material, artists’ materials, paint brushes, ordinary playing cards; printers’ type and clichés (stereotype); all included in this class”;

(iii) in Class 25 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Articles of clothing, footwear and headgear, including coats, jackets, trousers, overalls, shirts, pullovers, sweaters, hats, vests, waistcoats, cardigans and belts (for wear)”;

(iv) in Class 26 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations: “Badges, belt clasps, lace and embroidery, buttons, headwear ornaments, patches for repairing textile articles, pins and needles”.

The contended infringements

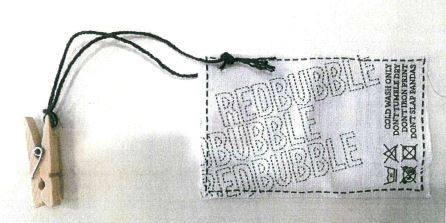

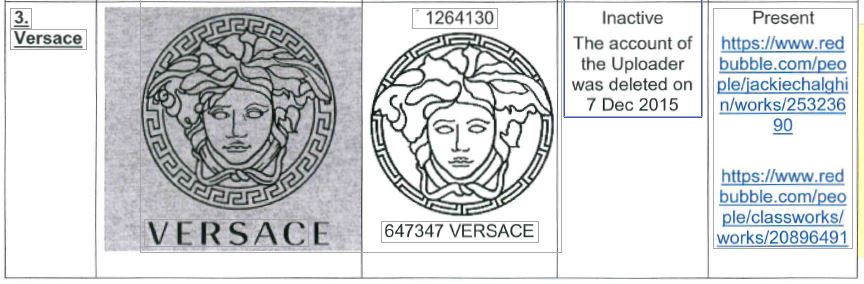

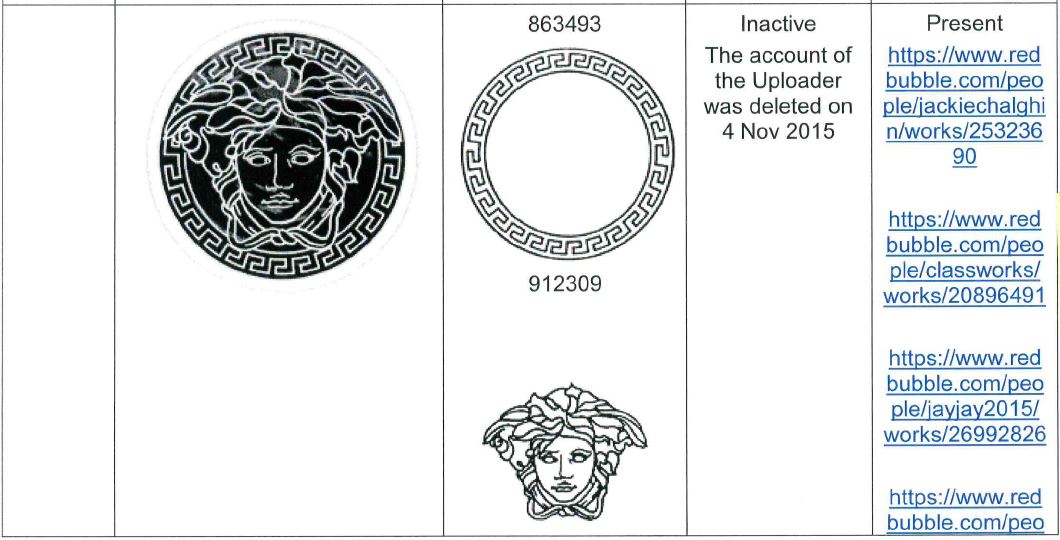

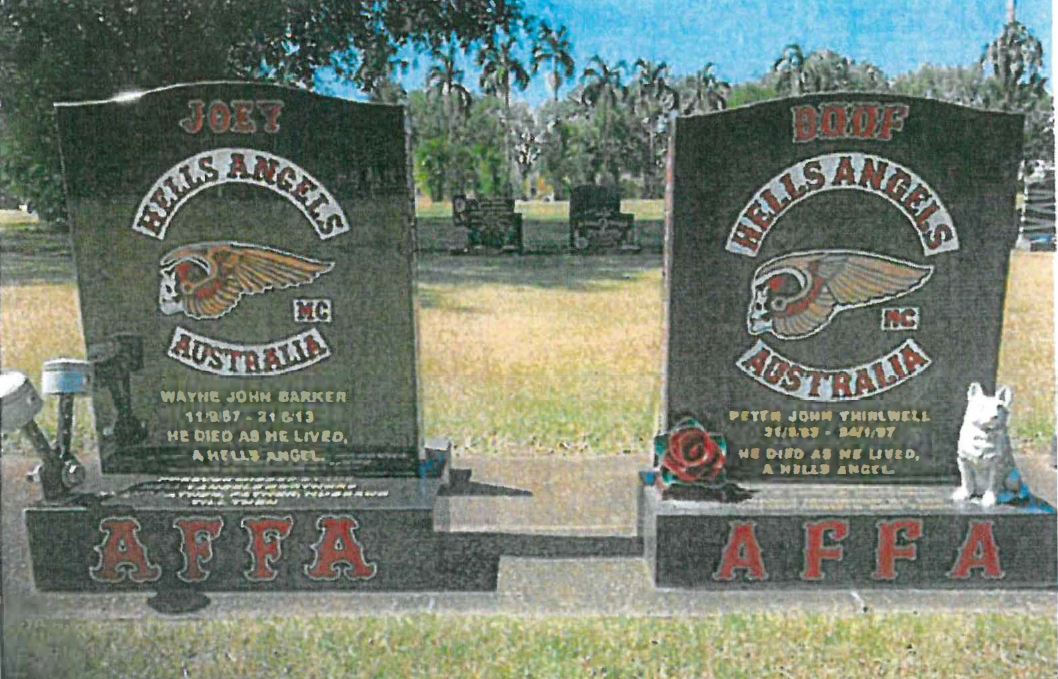

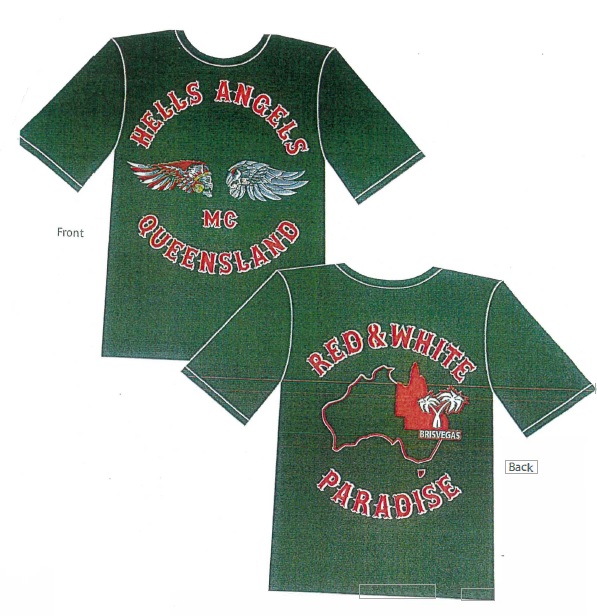

44 As to the contended infringements of the trade marks by Redbubble, the applicant relies upon four examples of artists uploading images to the Redbubble website and offering for sale products to which the uploaded image might be applied. In three of the four examples, transactions occurred in which the trade mark was applied “to goods”. The four examples relied upon by the applicant are set out below:

Example 1 – a Unisex T-shirt Hells Angels MC Virginia

Example 2 – a poster described as “Angel with Angel”

Example 3 – a T-shirt described as 1st Hells Angel T November 2015

Example 4 – a T-shirt identified as Hells Angels – Death before Dishonour Design

45 Clearer examples of the images in Examples 3 and 4 are set out below:

46 Example 1 is described as “E1” in Attachment E to the applicant’s third further amended statement of claim (“FASOC”). Example 2 is “E4” in the FASOC. Example 3 is “E5” in the FASOC and Example 4 is an image described and depicted at para 29A(a) of the FASOC.

47 As to the statutory integers of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act, the applicant says that Redbubble has, by reason of its operation of the Redbubble website having regard to the functionality of the site, engaged in the conduct of using, as a trade mark, a sign (each of the previous four examples) that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the relevant trade mark(s) in relation to goods or goods of the same description in respect of which the relevant trade mark is registered. Examples 1 and 2 are said to infringe all five trade marks in suit. Example 3 is said to infringe Trade Marks 723463 and 1257993. Example 4 is said to infringe Trade Marks 723219, 723463, 1257992 and 1257993.

48 Otherwise, Redbubble and the artist are said to be joint tortfeasors because they are engaged in a common design to use a sign which is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the identified registered trade marks, as a trade mark, in trade, in relation to goods or goods of the same description for which the relevant mark is registered.

49 As to “use of a trade mark”, by Redbubble, the applicant places emphasis upon s 7(4) and s 7(5) of the Trade Marks Act which is in these terms:

(4) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods).

(5) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to services means use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services.

50 As to use of a sign, as a trade mark, as expressly required by s 120, s 17 of the Trade Marks Act provides that a trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish the goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person. In other words, the “infringer” must be using the relevant sign as a badge of origin of goods or services.

51 As to sales of products transacted through the Redbubble website (and data concerning the number of views concerning the four examples mentioned earlier), the details are these:

Example | Sales | Views |

Example 1 | 2 | 304 |

Example 2 | 4 | 1,724 |

Example 3 | 1 | 767 |

Example 4 | 0 | 11 |

52 As to each of these examples, the following matters should be noted, based on the evidence of Mr James Toy, Redbubble’s assistant general counsel based in San Francisco.

Some aspects of the uploading of images and transactions concerning the four examples

53 The image at Example 1 was uploaded by a person named De Ann Troen whose username on the Redbubble website was “photroen”. When signing up to the Redbubble website, Ms Troen gave, as her address, an address in Virginia in the United States of America. Ms Troen uploaded the artwork to the Redbubble website on 21 September 2014 and gave it a title “7825”.

54 The Redbubble “Content Team” on 30 December 2014 took steps to “Moderate” the artwork as a result of a letter from the applicant’s solicitor, Mr Bolam, to Redbubble dated 24 December 2014 (received on 29 December 2014). By “moderated”, Mr Toy means that as a result of Mr Bolam’s letter, steps were taken to “remove or disable access to the webpage on the Redbubble website where the artwork was listed and through which products bearing the artwork could be purchased”: para 21, Mr Toy’s affidavit, 27 July 2017.

55 The artwork was never reinstated to the website.

56 While the artwork remained on the site in the period 21 September 2014 to 30 December 2014, two users purchased a product bearing the artwork through the website.

57 Mr Gavin Hansen ordered a T-shirt bearing the artwork on 18 November 2014. Mr Hansen provided a shipping address to Redbubble in Currumbin, Queensland, 4223. The T-shirt with the artwork applied was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “SSI Digital Print Services” in Denver in the United States. The shipping company, UPS, delivered the T-shirt to Mr Hansen’s nominated address.

58 A user named Steve Sawyer ordered a T-shirt bearing the artwork on 18 November 2014. Mr Sawyer provided a shipping address in Lincolnshire, England. The T-shirt with the artwork applied was manufactured by a fulfiller called “T-Shirt & Sons” in the United Kingdom. A supply company called “Whistl” delivered the T-shirt to Mr Sawyer’s nominated address.

59 The image at Example 2 was uploaded by a person named Mel Hok whose username on the Redbubble website was “LavaMel”. When signing up to the Redbubble website, Ms Hok provided as her address, an address in West Yorkshire, England. Ms Hok uploaded the artwork to the site on 17 November 2009 and gave it a title “Angel with Angel”. The Redbubble Content Team moderated the artwork on 30 December 2014 as a result of the letter from Mr Bolam dated 24 December 2014. The artwork was never reinstated. Mr Toy says that during the period that the artwork remained on the website between 17 November 2009 and 30 December 2014, four users purchased a product bearing the artwork through the Redbubble website.

60 On 30 November 2009, a user named Karin Lawrence ordered a matted print bearing the artwork. Ms Lawrence provided to Redbubble, as her shipping address, an address in Sutton-in-Ashfield, England. The matted print was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “Horsham Colour” in Australia. The shipping company, Australia Post, delivered the matted print from Horsham Colour directly to Ms Lawrence. Ms Lawrence also ordered a framed print bearing the artwork on 30 November 2009. The framed print was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “Prodigi” in the United Kingdom. The shipping company, Whistl, delivered the framed print from Prodigi directly to Ms Lawrence.

61 On 22 September 2011, a user named Shannon Faherty ordered a photographic print bearing the artwork. Ms Faherty provided to Redbubble, as a shipping address, an address in California, USA. The photographic print was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “Bayphoto” in California, USA. The shipping company, USPS, delivered the photographic print from Bayphoto directly to Ms Faherty.

62 On 5 December 2014, Gavin Hansen ordered a poster bearing the artwork. Mr Hansen provided as his shipping address, an address in Currumbin, Queensland, 4223. The T-shirt was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “HC Pro” in Horsham, Australia. The shipping company, Australia Post, delivered the poster from HC Pro directly to Mr Hansen.

63 As to Example 3, the person who uploaded the artwork to the website is a user named Becks Boyd, whose username on the website was “Becks Boyd”. When signing up to the Redbubble website, Ms Boyd provided, as her address, an address in Addlestone, United Kingdom. Ms Boyd uploaded the artwork to the Redbubble website on 4 August 2015 and gave it a title “Hells Angel”. The Redbubble Content Team moderated the artwork on 25 November 2015. The artwork was never reinstated. During the period that the artwork remained on the Redbubble website between 4 August and 25 November 2015, one user purchased a product bearing the artwork through the website. The user was Gavin Hansen who ordered a T-shirt bearing the artwork on 9 November 2015. Mr Hansen provided his shipping address as an address at Currumbin, Queensland, 4223. The T-shirt was manufactured by a third party fulfiller called “SSI Digital Print Services” in Denver in the United States. The shipping companies, UPS and Australasian Mail Service, delivered the T-shirt from SSI Digital Print Services directly to Mr Hansen.

64 As to the fourth example, the artwork was uploaded to the website by a user named Pandora Kelly whose username on the site was “OriginalApparel”. When signing up to the website, Ms Kelly provided, as her address, an address in Winterton, United Kingdom. Ms Kelly uploaded the artwork to the website on 31 March 2015 and gave it a title “Hells Angels – Death Before Dishonour”. The Redbubble Content Team moderated the artwork on 3 April 2015. The artwork was never reinstated. While the artwork remained on the website between 31 March and 3 April 2015, no person purchased a product bearing the artwork through the Redbubble website.

65 Mr Gavin Hansen is a trainee trade mark officer of the applicant. His role includes “monitoring, predominantly online, and identifying uses of signs which might be considered deceptively similar to those HAMC AUS is entitled to use under the authority of the trade mark owner Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation, the second respondent in the proceeding”: para 2, affidavit Gavin Hansen, 4 April 2017.

Other background matters

66 The applicant contends that a proper examination of the functionality of the Redbubble website and the sequence of steps involved in effecting a transaction between an artist and a buyer renders Redbubble the seller. In other words, the applicant says that Redbubble is not simply providing an “internet service” to artists and buyers and nor is it merely establishing an electronic market. Rather, Redbubble, through the functionality of the website, takes the order, issues the invoice, effects payment, derives revenue as a result of the transaction, arranges for the order to be fulfilled and arranges for postage and delivery of the relevant article to the buyer. Moreover, the applicant says that throughout various parts of the process, Redbubble undertakes these “services” in and by reference to the Redbubble trade marks. The applicant says that goods bear a swing tag or other reference to Redbubble and these factors are indicia of Redbubble being the relevant “seller” of the goods bearing the impugned marks.

67 Redbubble contends that it is not “using” the marks as suggested and nor are the integers of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act made out.

68 It also says that because the functions effected through the Redbubble website are effected by routines on the servers in the United States, there is no relevant conduct occurring “in Australia”. Redbubble also says that although s 120 of the Trade Marks Act does not contain the words “in Australia” (unlike s 36(1) of the Copyright Act), the entire “territorial” structure established by the Trade Marks Act for national registration and use of trade marks suggests that the Parliament did not intend the proscription of infringing conduct to apply to something done outside Australia (extra-territorially) even though conduct outside Australia might concern a trade mark registered in Australia.

69 Redbubble says that the infringing conduct must occur “in Australia”.

70 Apart from all of these issues (including the proposition that no relevant conduct occurs in Australia due to the location of the servers and the place of execution of commands), Redbubble says, so far as direct infringement or authorisation is concerned, that the website is an online electronic open marketplace where artists and consumers engage. Redbubble says that it does not determine the content of that which is uploaded; it has agreements in place with artists to address the importance of intellectual property rights; and it takes steps to “moderate” the site and remove material about which complaints are made concerning intellectual property issues where there seems to be a basis for concern.

71 Apart from all of these issues, Redbubble also has a cross-claim for revocation of the registered trade marks on the ground of non-use. I will address the content and detail of that matter as a separate question.

Ownership of the copyright in the Membership Card image

72 For the purpose of addressing this issue, I accept that the image appearing on the Membership Card was drawn or made by a man called Sundown in or about September 1954 in San Francisco.

73 In relation to the question of ownership of the copyright in the Membership Card image, it should be noted that the applicant does not rely upon, as proof of ownership, the registration of the image entitled “Hells Angels Membership Card (1954)” in or with the United States Copyright Office bearing Registration Visual Work Number VAu001214935 or the amended registration.

74 The relevant matters are these.

75 Mr Ralph “Sonny” Barger is a United States citizen born in Modesto, California in 1938. At the time of his declaration in these proceedings on 29 March 2017 he was residing in Livermore, California. He has been a member of the “Hells Angels Motorcycle Club” (the “Club”) continuously since 1957.

76 The Club is comprised of “a group of motorcycle enthusiasts”.

77 Mr Barger founded the Hells Angels Oakland “Charter” of the Club in 1957 (the “Oakland Charter”). As an officer of the Oakland Charter, Mr Barger was a member of the governing Board made up of “officers” of the Hells Angels Charters in California. He was a member of the Board of Directors of “Hells Angels, Frisco Inc”. He was a member of the Board of that company and also “its successor corporations”, as he puts it, “for many years”. He was a member of the Cave Creek Arizona Charter for many years. He is currently a member of the Oakland Charter.

78 Mr Barger says that he is the person most knowledgeable about the creation and evolution of the logos, brands and trade marks used by the various Hells Angels charters and the role of the relevant corporation charged with the responsibility of managing the intellectual property developed or created by the Charters or members of the Club.

79 Mr Barger says that the first Hells Angels Motorcycle “club” was founded in March 1948 in the Fontana/Bernardino, California area. One of the founders was William Charles Graves, a Second World War Veteran. Mr Barger says that it is a myth that the founders of that club were part of the 303rd Hells Angels Bomber B17 Group from WWII. He says that a First World War fighter squadron apparently used the name “Hells Angels”. The “Berdoo club” began using, as the name of the club, “Hells Angels” in its various dealings from 1948.

80 Initially, the various Hells Angels “clubs” in California were “only loosely affiliated”. In the 1950s, the Californian clubs comprising Berdoo, Frisco “So. Cal [Southern California]” and Oakland, joined into one “brotherhood called the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club”; the “Club” as earlier mentioned and defined.

81 After the Club formed, individual clubs became Charters of the Club. Officers of what were now the various “Charters’ began meeting as a Board of Directors of the Club. Mr Barger participated in these meetings. Decisions of the Board of the Club bound the Charters. All Charters had to approve the admission of a new Charter. Guidelines were established about how insignia could be used. “Death Head” designs began to emerge and “were always used to signify membership in a [Charter] and the [Club]”.

82 The first Charter outside California was established in Omaha, Nebraska. The second was established in Lowell, Massachusetts.

83 In 1948, the Berdoo members used a small design for its membership insignia consisting of a skull in profile, a helmet and two wings. It came to be called the “Original Death Head”: see the image at para 12 of Mr Barger’s declaration. It was used only “between and among members as an indicia of membership in the [Berdoo] club”.

84 In 1948, Berdoo club members began using an insignia that consisted of an “upper rocker” (a semi-circle of the words “Hells Angels”), the Original Death Head in the centre, and a “bottom rocker” (a semi-circle of the word Berdoo). This configuration was known as the “original patch”. It was sewn onto the back of jackets. It too was only used between and among members as an indication of membership in the Charter.

85 In 1953 or 1954, Mr Graves organised the formation of a San Francisco Charter called “Hells Angels Frisco” (the “Frisco Charter”). In 1955, the Frisco Charter restructured with 13 members including Mr Frank Sadilek as President. Mr Barger says that at about this time, a modified version of the Original Death Head was created, also relatively small in size: see the image at para 21 of Mr Barger’s declaration. It came to be known as the Modified Original Death Head. It was created by a member of the Frisco Charter for use as an indicia of membership of the Frisco Charter.

86 Mr Gordon Grow is a United States citizen who resides in Oakland, California. He says he has been a member of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club continuously since 1967. He was initially a member of the Frisco Charter. In 1985, he transferred to the Oakland Charter and has been a member of that Charter since then. He says that he was an officer of the Californian non-profit corporation that the Club formed to own and manage intellectual property of the Club and Charters. He says the company is called “Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation” which he calls the “Corporation”. I will return to Mr Barger’s evidence on that topic later in these reasons.

87 Mr Grow says that he is the most knowledgeable person about, and familiar with, the historical archives and records of the San Francisco and Oakland Charters, and of the Corporation. Mr Grow sets out in his declaration the sources of his information.

88 Mr Grow says that in the 1950s the “So. Cal.” Charter used a single wing, side-facing, Death Head. The Berdoo and Frisco Charters used a double wing Death Head as their membership insignia, often displayed as a patch on the back of vests or jackets with an upper and lower rocker as explained by Mr Barger.

89 Mr Grow says that before 1954 there was no Membership Card.

90 Mr Grow says that he personally located in the Club archives, minutes from the Frisco Charter meetings of members held in September 1954. Mr Grow had been told about a September 1954 meeting by Mr Warren Gettler, a Frisco Charter member who was at the meetings. Mr Gettler has since died. Mr Grow refers to the minutes of the meeting of 9 September 1954. The minutes reflect a roll call of members present, and the guests present. The 2 September 1954 minute notes that a group of Berdoo members would arrive “Saturday and a party would be held in their honour at Thornton’s Beach”. The 9 September1954 minute notes the party having been held. It also notes that:

It was decided that Sundown was to receive $2.50 for artwork on our club cards – and that he would be allowed three clean, unvoided cards for display purposes in his business.

91 It seems likely that the artwork had been done by the time of the meeting on 9 September 1954. The members seemed to be in a position to assess the artwork and decide that Sundown ought to receive payment (although nominal) for it. Membership Cards may have been prepared.

92 Mr Phil Torre gave evidence. He was cross-examined as was Mr Barger.

93 Mr Torre is a United States citizen who resides in Santa Rosa, California. He was born in 1934. He says that he was a member of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club continuously from 1953 or 1954 until he left the Club to look after his mother (although he remained a member of the Frisco Charter). He says that the Frisco Charter was formed in 1953 or 1954. He says that during his time as a Club member, he has learned a great deal about the history and activities of the Club especially from his own personal experiences. He says that before 1954 there was no Membership Card for the Club. He says that members of the Frisco Charter “frequently hung out and had meetings at Rialto pool hall on the north east corner of 7th and Market Street, San Francisco, California during the years 1953 and 1954 and later”. He says that he personally also “hung out there”.

94 Mr Torre says: “We got to know a tattoo artist who also hung out in that pool hall who went by the name Sundown”. Mr Torre says that “we knew he could draw” which, no doubt, is a reference to those members who had a practice of hanging out at the pool hall. Mr Torre says that he and other members had ideas about how they wanted the Membership Card to look. Mr Torre says that the Frisco Charter decided to hire Sundown to help them put their ideas about a Membership Card into a graphic form that “could be printed for each Charter member”. Mr Torre says that Sundown provided technical illustration services that would “allow the membership card to be reproduced for and on behalf of the Club”. Mr Torre says that Sundown did the work at the direction, supervision and expense of the Hells Angels Frisco which seems to be another reference to the Frisco Charter.

95 Mr Torre saw the “rough sketches that Sundown created”.

96 Mr Torre says that he and some members made comments. Sundown made changes to the rough sketches. The Frisco Charter approved the final design in the form at [17] of these reasons. Mr Torre says that the Frisco Charter was to own all relevant rights in the card. He says that Sundown was a tattoo artist whose place of business was near the Rialto pool hall earlier mentioned. He says that Sundown’s shop was in the same building as the pool hall “where many of us hung out”. He says that he recalls that Sundown’s real name was “Bob”. Mr Torre says this at paras 16-18 of his declaration:

16. Listings in Polk’s San Francisco City Directory, published in 1953, identified the pool hall as “Rialto Billiards” with the address of 1138a Market Street, San Francisco, CA. A page of the City Directory is attached hereto as Exhibit [PT 2]. Rialto Billiards is where we met Sundown.

17. Sundown’s tattoo shop was located in the same building as Rialto Billiards. Contained within Polk’s San Francisco City Directory 1953 attached to this declaration as [PT 2], is identified “Kestner, Robt D. Tattooing” listing an address of 1138 Market Street, San Francisco, California. Robert D. Kestner is also listed as Robert D. Kistner, also as having an address of 1138 Market Street, San Francisco, California Polk’s San Francisco City Directory 1953 [p 2, Ex PT2].

18. Based upon personal knowledge, experience, and review of Exhibit PT2, Polk’s San Francisco City Directory 1953, I can confidently testify that Sundown was the pseudonym for the person named “Bob”, listed as Robert D. Kestner, who operated the tattoo shop in the same building as Rialto Billiards, and that the Sundown whom the Hells Angels Frisco hired to do the illustration for the Membership Card was named Robert Kestner or Robert Kistner.

97 Mr Torre gave evidence that when he joined the Frisco Charter in 1953 or 1954 there were about eight or 10 members. Generally there were weekly meetings. There was no Membership Card when he joined. Mr Torre ultimately did receive a Membership Card. When he gave evidence, he had with him a card he had received in 1961. Mr Torre was asked to agree with the proposition put by Redbubble’s counsel that everyone who was a member of the Frisco Charter got a Membership Card in 1954. Rather than expressly embrace that proposition, Mr Torre said that no-one received a card until they became a member and in his case, “Frank” as President, signed his card. He was asked whether he could remember when he got his first card and he answered “55”. He seemed to say that he first joined the Club in 1954, and in 1955 he got his card.

98 Mr Torre made the point that he was trying hard to do the best he could to recall the events. However, it should be remembered that Mr Torre was born in 1934 and at the time of his giving evidence, he was 83 years of age. Nevertheless, his recollection of some things seemed to be quite clear.

99 Mr Torre said that he was present at the Thornton’s Beach party when the Berdoo members visited in September 1954. Mr Torre was asked if he could recall whether the members might have received their Membership Cards at that party. He seemed to reject that proposition (although not directly) by again saying and making the point that “you did not get a card until you became a member”. Perhaps Mr Torre was thinking that some persons who were not (or may not have been) members may have been present at the Thornton’s Beach party or perhaps that “party” was not a forum for issuing the Membership Cards.

100 Mr Torre was asked whether, for those persons who were already members when the card was designed, they all got their cards at once. Mr Torre seemed to then say that he got his card “in the latter part of 54”.

101 I will return to some aspects of Mr Torre’s evidence on this topic later in these reasons.

102 Returning to Mr Barger’s evidence, Mr Barger refers to the Membership Card image (depicted at para 29 of his declaration in the same terms as the image at [17] of these reasons). He says that the card also recorded the member’s details and the member’s Charter affiliation.

103 Mr Barger says that the Club began to develop internationally in 1961 with a Charter in Auckland, New Zealand. In 1969, a London Charter was admitted. Other Charters in the United States were admitted. Today there are more than 250 Charters in Europe. At the end of the 1970s, Australian Charters were admitted. Against the background of growth in Charter admissions, the Club started to get ready to incorporate. On 6 August 1966, Club members voted to create a non-profit corporation. On that day, Mr Barger was elected Chairman of the Board of the still unincorporated association (that is, the Club).

104 The primary purpose of the new corporation was, he says, to be to own, licence and protect the Club’s intellectual property.

105 Several years elapsed but on 2 September 1970, the Frisco Charter incorporated a non-profit corporation called “Hells Angels of San Francisco Inc.” (“HA San Francisco Inc”).

106 From then, Club members began to call HA San Francisco Inc, the “Corporation”. He says that members of Charters agreed that the Corporation would manage and enforce all of the Club’s intellectual property. He says that the Corporation began to “enforce” rights in relation to Hells Angels insignia, internationally.

107 In 1971 or 1972, a lawyer in Los Angeles incorporated “the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club Inc.” (the “1972 Corporation”) as a “for profit” corporation. That entity applied for a side-view Death Head image together with the words “Hells Angels” as a trade mark. Mr Barger gave evidence that both steps were a mistake which the Club “straightened out”. The 1972 Corporation was dissolved and the trade mark registration was assigned to HA San Francisco Inc in 1975.

108 On 4 May 1973, HA San Francisco Inc changed its name to “Hells Angels Frisco Inc.” (“HA Frisco Inc”) and on 3 October 1981 the Club resolved to change the name again to “Hells Angels of the United States Inc.” (“HAUS Inc”) with Mr Barger elected as Chairman. The name changed again to “Hells Angels Motorcycle Club Inc.” and again to “Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation” which is the current name of the Corporation. Mr Barger asserts that although there have been a succession of name changes, the Corporation, by its current name, is the entity “which owns all [Hells Angels] intellectual property”.

109 Mr Barger says that the mechanism by which that result is so, arises in the following way.

110 Around October 1981, “Club members” and “Club Charters” which had participated in creating Hells Angels intellectual property “agreed” that the non-profit entity then called HAUS Inc “would own all copyrights and trade marks and other intellectual property and all intellectual property of the Charters”, including the Membership Card image. Mr Barger says that “by an oral agreement, which was fully and legally binding on all the Charters and members at that time”, all of the intellectual property subject matter just described was “assigned into [HAUS Inc]”. Mr Barger says that the Club decided to have a non-profit corporation own all of the intellectual property (as earlier described) so that “no private individual or company would own the Club’s intellectual property”. The company would be used and managed for the benefit of “Club Charters and members” and not for gain.

111 As to the ownership of the copyright subsisting (or said to subsist) in the Membership Card image, the position for the purposes of Australian law is clear. Notwithstanding United States copyright law in relation to “works for hire”, Mr Cobden SC for Redbubble and Mr Eliades for the applicant, agree (and conducted this issue at trial on the footing) that for the purposes of Australian copyright law there must be an assignment in writing vesting the ownership of the copyright (originating in the author, Sundown) in the entity HAMC US: s 239 of the Copyright Act; no such assignment is asserted or in evidence.

112 It may be that on proper analysis, the members of the San Francisco Charter on or about September 1954 became the beneficial owners of the copyright subsisting in the Membership Card image. It may also be that by force of certain oral agreements, the continuing members of the San Francisco Charter decided to confer whatever interest they enjoyed in Sundown’s work, upon HAMC US. Perhaps they hold the legal title on trust for HAMC US. However, HAMC US is not the owner of the legal title to the copyright in the work for the purposes of Australian domestic copyright law. Accordingly, the applicant’s title can rise no higher than that of HAMC US (putting to one side entirely the question of whether the applicant is properly characterised as an exclusive licensee of HAMC US in respect of any copyright that that corporation does own).

113 I am not satisfied that the second respondent is the owner of the copyright in the Membership Card image for the purposes of Australian copyright law.

The Fuki current Death Head design

114 It seems reasonably clear from the applicant’s written submissions and certainly from the oral submissions that very little emphasis or weight (or analysis) has been placed upon the Fuki work as a source of rights said to have been infringed. However, the applicant has not abandoned reliance upon the Fuki work and thus it is necessary to address the topic.

115 Mr Barger says that in 1983 “as part of standardising the brand”, the Fuki Death Head design was created in digital form. The objective of this “standardisation process” was to “help eliminate natural variations in patches that resulted from them [their] being hand-made”. Mr Fukushima gave a declaration of 2 February 2016 in which he says that he “created the design described as the ‘Fuki Death Head’ or ‘Death Head (Side View)’ as a derivative work, intended to up-date a pre-existing copyrighted work owned by HAMC”. He says that his work is “based upon and derived from the ‘Death Head’ design” in the “Hells Angels Membership Card [image]”.

116 Mr Fukushima identifies that work by displaying the Membership Card image at para 7.

117 Mr Fukushima then explains that from the moment of creation of his derivative work, he intended HAMC to have the sole and exclusive rights that might subsist in the work. He says that in 2015 in order to perfect HAMC’s “beneficial ownership in the Work to legal ownership of the Work” by vesting the legal title in HAMC, he executed a written assignment in favour of that corporation. However, the 2015 assignment attached an incorrect illustration of the Fuki Death Head. Mr Fukushima confused a very similar drawing by Mr Barger called the “Barger Larger Death Head”, with his drawing. The only real point of distinction between the two is that Mr Fukushima’s drawing has nine “feather points” on the bottom section and not eight. A fresh assignment was executed by Mr Fukushima on 29 March 2017 to correct the error.

118 There are four things to note about Mr Fukushima’s evidence and that of Mr Barger.

119 First, Mr Fukushima gives no evidence about the skill, effort or work deployed by him in bringing his image into existence.

120 Second, he describes it as a “derivative work”, “based upon and derived from” the Membership Card image.

121 Third, he says his work was simply to “update” the earlier Membership Card image.

122 Fourth, Mr Barger says that the process involved was a standardisation exercise to avoid natural variations in hand-made patches.

123 I am not satisfied that any copyright has been demonstrated to subsist in Mr Fukushima’s work. Mr Fukushima’s work is simply a derivative standardised version of the earlier Membership Card image. There is no independent copyright subsisting in Mr Fukushima’s work and all rights in that work derive from whatever rights subsist in the work from which it derives, namely, the Membership Card image.

124 Recognising the difficulties in demonstrating ownership of the copyright said to subsist in the Membership Card image (and, derivatively, the Fuki current Death Head design), the applicant sought to rely upon s 213 of the Copyright Act. That section provides that s 35(5) does not apply in relation to works made in pursuance of an agreement made before the commencement of the Copyright Act (1 May 1969): s 213(2). Where a work is excluded from the operation of s 35(5) by s 213(2), s 35(2) has effect (rendering the author of the artistic work the owner), subject to ss 213(4) to 213(8): s 213(3).

125 Section 213(5) is in familiar terms and provides:

213 Ownership of copyright

…

(5) Where, in the case of a work being a photograph, portrait or engraving:

(a) a person made, for valuable consideration, an agreement with another person for the taking of the photograph, the painting or drawing of the portrait or the making of the engraving by the other person; and

(b) the work was made in pursuance of the agreement;

the first-mentioned person is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work by virtue of Part III.

[emphasis added]

126 The question of whether the drawing made by Sundown in September 1954 bears the characteristics comprehended by the statutory language of an agreement for the painting or “drawing of the portrait” by Sundown is seriously open to doubt.

127 The subject matter of the drawing is a profile or side-view of a human skull (described as a Death Head) wearing a helmet adorned with feathers or headdress. The applicant says that the Membership Card image is “a portrait” and the agreement made between the Frisco Chapter and Sundown in 1954 was an agreement made for the “drawing of the portrait” and that the Frisco Chapter members are the owners of the copyright in the image.

128 The claim that the subject matter of the Sundown work is a portrait was not pleaded.

129 However, it was first raised in closing submissions.

130 The respondent says that it would have called expert evidence about the topic of whether the subject matter of the drawing is properly characterised as a portrait. Questions might arise about whether the drawing can be regarded as something in the nature of a grotesque caricature of “a person”.

131 I doubt very much that it can be so regarded.

132 The drawing is a side-view of a human skull (any and every human skull) in a state best described as a Death Head. A “portrait” is understood as a “representation of a person or animal, especially of the face, made by drawing, painting or photography”: Oxford English Reference Dictionary, Revised 2nd Ed.

133 A particular representation of a person or animal might be an exaggeration of the features of that person or animal but nevertheless it would arguably remain a representation of a particular person (or animal). In this case, there is no particular person or animal represented by the image. It is an image of a skull as an anatomical feature of a human, wearing a helmet and adorned by particular feather points sometimes called a headdress. No doubt, expert evidence might have been called about this topic. I accept that the respondent may have elected to call evidence on this issue and was deprived of an opportunity to do so, as it contends, by the lateness of the point.

134 I am not willing to allow the applicant to run the point at this late stage. I have very little doubt, in any event, that the point has no merit but that question would have been determined upon proper evidence which would almost certainly have involved some expert evidence about the nature of a “portrait” for the purposes of the Copyright Act and whether Sundown’s work engages that concept.

135 If the work is to be regarded as a portrait, it would mean that the members of the Frisco Charter in 1954 would have become the owners of the copyright and presumably the copyright would have been held by the members of that Charter “for the time being”, over time. If that were so, the difficulty remains of demonstrating whether the ownership of the copyright in the portrait subsisting in the Frisco Charter members ever became vested in HAMC US.

First publication of the Membership Card issue

136 Notwithstanding that HAMC US treats the Membership Card image as “unpublished” for the purposes of United States copyright law, the parties again agree that the question of whether the work is a published work falls to be determined according to Australian domestic copyright law: Enzed Holdings Ltd v Wynthea Pty Ltd (1984) 4 FCR 450 at 458, Sheppard, Morling and Wilcox JJ.

137 However, s 210 of the Copyright Act applies to the Sundown work as if, for the purposes of determining whether copyright subsisted under the Copyright Act 1911 (Imp), the work was first published in Australia: Reg 10, Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (Cth). Redbubble says that the Membership Card endorsed with the Sundown work was first published in 1954. Section 29(1)(a) provides that an artistic work or an edition of such a work, “shall be deemed to have been published if, but only if, reproductions of the work or edition have been supplied (whether by sale or otherwise) to the public”.

138 Sundown’s “exhibition” of the work, as an example of his work or skill, is expressly excluded by s 29(3) of the Act.

139 Redbubble relies upon “supply” of reproductions other than by sale, “to the public” (s 29(1)(a)) in the period 9 September 1954 to 31 December 1954 by distribution of the card to all members of the Club that commissioned the work, that is Hells Angels Frisco. I accept that the Membership Card was established as a badge of membership of the Hells Angels Frisco Club; that it was endorsed with the Sundown work; that it was, over time, issued (distributed) to members as a badge or indicia of membership of persons accepted as “admitted” to membership by the relevant Chapter as like-minded persons sharing an enthusiasm for motorcycles.

140 I am not satisfied on the evidence that the Membership Card was first issued to members in the period 9 September 1954 to 31 December 1954. It may have been issued in that period, but it may not. It could easily, on the evidence, have been sometime in 1955. Some cards may have been given to the small number of members of the Frisco Club in that period which seem to be around about eight to 10 or so members when Mr Torre joined in 1954 or 1955, but it is not clear. I am satisfied that the Membership Card was probably (more likely than not) issued to members of the Frisco Club at some time in 1955. The Membership Card was relatively widely used by members as a badge of membership by 1957 as it was issued to each member of four or five Charters then in existence amounting to a distribution to at least 48 members but possibly as many as 75 (being the best evidence of the range of possible members of the four or five Charters).

141 Is the distribution of a Membership Card to each member of a club of like-minded motorcycle enthusiasts a supply of reproductions of the work to the public?

142 At least so far as distribution by 1957 to either 48 or possibly as many as 75 members (at the outer boundary of the four or five Charters is concerned), I do not accept that issuing a Membership Card with the Sundown image endorsed upon it is a supply of reproductions of the work to the public.

143 Redbubble places great emphasis upon the observations of Dawson and Gaudron JJ in Telstra Corporation Limited v Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (1997) 191 CLR 140 at 156-157 (“Telstra v APRA”); Toohey J agreeing at 158; McHugh J agreeing at 174 and Kirby J agreeing at 202-203. Those observations go to the question of the scope of the concept of transmissions or distributions “to the public” and the notion of things occurring “in public”. The discussion by Dawson and Gaudron JJ of the concept of “to the public” and “in public” concerned a particular statutory setting and circumstances very different to those presented by the question of the character to be attributed to issuing a Membership Card to a relatively small number of members of a club, in this case, made up of motorcycle enthusiasts.

144 Telstra v APRA was concerned with the conduct of Telstra in the operation of its telecommunications network in Australia. APRA owned the copyright in the music and lyrics for various songs. Telstra engaged in the provision, in various ways, of music to telephone users placed on hold (a music-on-hold activity). APRA contended that Telstra’s music-on-hold activity engaged an exercise of APRA’s exclusive rights in the works, that is, to perform the work in public; to broadcast the work; and, to cause the work to be transmitted to subscribers to a diffusion service: s 31(1)(a)(iii), (iv) and (v) of the Copyright Act. The three ways Telstra provided music-on-hold were these.

145 First, where a person made a telephone call to a Telstra service centre and was placed on hold, music would be heard by the caller.

146 Second, where a person called a governmental or business organisation to which Telstra provided a transmission service, music-on-hold would be heard by a waiting caller.

147 Third, where a person made a call to a subscriber to Telstra’s “CustomNet” service and the subscriber’s line was busy, the call would be diverted to a music-on-hold facility at Telstra’s nearest telephone exchange.

148 Each of those three situations might arise either where the caller uses a landline (or “conventional telephone”) or where the caller uses a mobile telephone. It is not necessary to examine in these reasons the detail of the reasoning Dawson and Gaudron JJ (and those Justices agreeing with their Honours) on all of the issues raised by that litigation. The matters of relevant principle for present purposes arose in the context of whether, by providing music-on-hold to callers using a mobile telephone, Telstra engaged in a “broadcast” of the works in suit, and that question engaged whether Telstra had made a transmission by wireless telegraphy “to the public”. There was no doubt that Telstra had made a transmission by wireless telegraphy and thus the “only issue” (Dawson and Gaudron JJ at 153) was whether the transmission was “to the public”.

149 In that statutory context, Dawson and Gaudron JJ examined some of the notions developed in the jurisprudence about the words “to the public” and the notion of a “relationship” between a copyright owner and “the public”. The concept of the “copyright owner’s public” (a possessive notion) evolved in cases concerned with a distinction between a performance of a work “in public” on the one hand and a private or domestic performance on the other hand. The notion of transmitting (or supplying in the case of s 29(1)(a)) something (a work) “to the public” suggests a “broader concept” than something done “in public”. Dawson and Gaudron JJ observed at 155 that in the case of music-on-hold which might be heard when the caller is in a private or domestic setting, the transmission might nevertheless be “to the public”. Dawson and Gaudron JJ also observed at 155 that when thinking about a transmission to a “limited class of persons”, the cases addressing whether a performance is “in public” recognise that “the relationship of the audience to the owner of the copyright is significant” [emphasis added]: Dawson and Gaudron JJ at 155.

150 Their Honours observe that this recognition led to the notion of the “copyright owner’s public”. Whether an act occurred “in public” was to be considered in relation to the owner of the copyright. If the audience in question might properly be regarded as “the owner’s public” or part of “his [or her] public”, with the result that the doing of the impugned act before that audience transgresses upon the audience reserved to the owner, an infringement arises: Jennings v Stephens [1936] Ch 469 at 485, Greene LJ.

151 The question then became, according to a line of authority, is the audience, one which the owner of the copyright could fairly consider a part of his [or her] public? (Dawson and Gaudron JJ at 156) and the cases cited by their Honours: Ernest Turner Electrical Instruments Ltd v Performing Right Society Ltd [1943] Ch 167 at 171, 172-173, 175-176; Performing Right Society Ltd v Harlequin Record Shops Ltd [1979] 1 WLR 851 at 857; Australian Performing Right Association Ltd v Canterbury-Bankstown League Club Ltd (1964) 81 WN Pt (1) (NSW) 300 at 305-306; Rank Film Production Ltd v Dodds [1983] 2 NSWLR 553 at 559.

152 In Performing Right Society Ltd v Harlequin Record Shops Ltd (supra) at 857, Browne-Wilkinson J made this observation in the context of assessing the notion of whether the owner of the copyright could fairly consider the relevant audience a “part of his [or her] audience”:

[T]he authorities show that it is also important to see whether the performance is given to an audience for performances to which the composer would expect to receive a fee: this is what I understood Lord Greene M.R. to have meant by the “owner’s public” in Jennings v Stephens [1936] Ch 469 at 485 and Performing Right Society Ltd v Gillette Industries Ltd [1943] Ch 167, 173.

[emphasis added]

153 In the Australian case of Rank v Dodds (supra), the transmission of films to television sets in motel rooms (and the playing of those films by a guest in his or her room) was held (at 559) to “easily envisage” the notion that the motel guest, in his or her room in those circumstances, was “part of the copyright owner’s public”. The “critical matter” was that the movie was presented to the guest in his or her capacity as a guest: Rath J at 559. As to that example, Dawson and Gaudron JJ in Telstra v APRA at 156-157 observe that “the number of guests playing films in their rooms may not have been large but the motel was open to the public”.

154 Applying all of these principles, Dawson and Gaudron JJ observed in Telstra v APRA that those members of the public who chose to call a relevant number on their mobile phone may have been relatively small, but the music-on-hold facility was available “to members of the public generally”. Their Honours also said this at 157:

Lying behind the concept of the copyright owner’s public is recognition of the fact that where a work is performed in a commercial setting, the occasion is unlikely to be private or domestic and the audience is more appropriately to be seen as a section of the public.

155 In the case of the Membership Card image, Sundown was content to be paid what seems to be a nominal fee of $2.50 for “our artwork on the club cards” and he was content to see the image used on a card signifying a person’s membership of the Club. There can be little doubt that Sundown did not “expect to receive a fee” from the “audience” to whom the card was given. The members of the Club were not in any sense, it seems to me, “a part of Sundown’s audience” in the sense that that term is understood in the authorities. Moreover, it seems clear enough that the work was made for the purpose of adorning the Club Membership card with an acceptable properly drawn image for the limited purpose of members holding a card affirming their membership of the Club. The work is not one made, performed or given in a commercial setting. Also, Sundown’s “commercial interest” in the work was exhausted by the payment of $2.50.

156 The setting is very much in the nature of a private or domestic setting.

157 It follows that I do not accept that the Membership Card image was published by supplying cards bearing the image to members in 1955 or by 1957. When it was “published”, for the purposes of Australian copyright law, is not at all clear on the evidence. There are now a sufficient number of members of the various Chapters that the Membership Card is very likely to have been published for the purposes of Australian copyright law. Section 29(1)(a) of the Copyright Act, of course, is concerned with the circumstances (if, but only if) when, relevantly, an artistic work is “deemed” to have been published.

158 As to the question of whether the identity of Sundown was at any time between September 1954 and 31 December 2004 “generally known”, it seems clear enough that he was generally known by and to Mr Torre and at least some small number of other Frisco Charter members as “Sundown”. The evidence does not reveal whether his identity was generally known in the sense of whether he was generally known to all the members of the Frisco Charter and also to those persons coming and going from his tattoo shop (his customers) so that, although he used the “name” or “pseudonym” of “Sundown”, his identity was generally known to be, Robert (Bob) D. Kestner (sometimes spelt Kistner).

159 However, I am satisfied that his identity could have been ascertained by reasonable inquiry in September 1954 or at least within a reasonable period from September 1954 (a year or two or perhaps over a longer period). That follows because Mr Torre and other members knew him. They saw the draft image he drew. They commented upon it. They “hung out” in his daily environs. They spoke to him. Mr Torre could so easily have said to him, at any point in these engagements, “Hey, Sundown, what’s your real name? We need to know”. Is there any doubt that he would have received an answer from “Sundown” to that question? I think not.

160 Although I have concluded that the applicant has not established that HAMC US is the owner of the copyright subsisting in the Membership Card image and that the Fuki current Death Head design is truly a derivative work, I will nevertheless examine the question of whether the applicant is properly characterised as an exclusive licensee of the second respondent for the purposes of the Copyright Act and whether (assuming copyright subsisted in HAMC US) an infringement of copyright arises out of the conduct of the respondent as pleaded and contended.

Mr Kovalev’s role

161 Mr Kovalev is the “Chief Technology Officer” for the Redbubble group of companies, that is, Redbubble Limited, the first respondent; Redbubble Inc. (“Redbubble USA”); Redbubble UK Limited (“Redbubble UK”) described as a non-operating entity incorporated in England and Wales; and Redbubble Europe GmbH which he describes as a non-operating entity incorporated in Germany.

162 These companies are the Redbubble group of companies referred to by Mr Kovalev in his evidence.

163 The Head Office for Redbubble Limited is located in Melbourne. Mr Kovalev gives, as his address, a business premises address in Collins Street, Melbourne. Mr Kovalev has been in continuous employment with Redbubble since 12 December 2015 as the Chief Technology Officer. He is a member of Redbubble’s executive leadership team and he is responsible for overseeing all technology matters including: the management and maintenance of Redbubble’s technology assets including the Redbubble website and the technology infrastructure supporting it; software engineering and development activities; and the management of Redbubble’s technology staff. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Engineering and a Master of Science in Computer Science from Georgia Institute of Technology. Mr Kovalev sets out in his affidavit of 28 July 2017 other aspects of his background skills which are not necessary to recite in these reasons.

Martin Hosking and the business model deployed by Redbubble

164 As to the background matters concerning the “business model” deployed by Redbubble and the role of the various Redbubble entities, the evidence of Mr Martin Hosking should be noted before returning to Mr Kovalev’s evidence concerning the functionality of the Redbubble website.

165 Mr Hosking is the Managing Director (“MD”) and Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) of Redbubble Limited. He has been the MD and CEO since June 2010. He is on the Board of Redbubble USA and Redbubble UK. Mr Hosking was one of the founders of the Redbubble business in 2006 (as a proprietary limited company) together with his co-founders, Peter Styles and Paul Vanzella. The business model adopted by the founders is described by Mr Hosking as based on the “idea of an online marketplace” where “artists and designers would be the primary customers”. The founders decided to “combine” their “new concept” with the technology they had already developed for a “‘print-on-demand’ personalization service for customers who wanted to purchase a product with an image or word they had created”. The “online marketplace” combined with the “personalization service” technology would enable artists to “upload and sell their designs”: Hosking, affidavit, 28 July 2017, paras 7, 12, 16-18.