FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Moffet v Dental Corporation Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 344

ORDERS

|

Applicant | ||

|

AND: |

DENTAL CORPORATION PTY LTD (ACN 124 730 874) Respondent | |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in Short Minutes of Orders to give effect to these reasons within fourteen days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FLICK J:

1 The Applicant in the present proceeding, Dr David Moffet, is a registered dental practitioner.

2 By an Originating Application filed in this Court in December 2017, Dr Moffet primarily seeks relief under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). He also makes claims in respect to long service leave and superannuation entitlements.

3 Between 1987 and 2007, Dr Moffet had operated a dental practice located in Parramatta in New South Wales. Since 2000, that practice was operated under the registered business name of “Active Dental”. During that period he was employed by Immediate Dental Care Pty Ltd as trustee for The Moffet Family Trust (“Immediate Dental”).

4 The Respondent to the proceeding is Dental Corporation Pty Ltd (“Dental Corporation”).

5 In 2005, Dr Moffet was approached by representatives of the yet to be incorporated Dental Corporation regarding the “aggregation” of dental practices. In November 2007, Dr Moffet and Immediate Dental sold (inter alia) the practice to Dental Corporation. On 15 November 2007, two agreements were executed, namely:

the Dental Practice Acquisition Agreement (“Acquisition Agreement”); and

a Services Agreement.

The Services Agreement was for a term of five years. After that Agreement came to an end in 2012, Dr Moffet continued to perform services for Dental Corporation although the basis upon which he did so was the subject of negotiation. A letter of resignation dated 21 November 2014 was sent by Dr Moffet to Dental Corporation.

6 The principal issue in the proceeding focussed upon whether Dr Moffet was engaged to perform work for Dental Corporation as an employee or as an independent contractor.

7 In the event that that issue was resolved in favour of Dr Moffet and it be concluded that Dr Moffet was an employee, he thereafter claimed (inter alia) that Dental Corporation:

contravened section 357 of the Fair Work Act by representing to him that the contract pursuant to which he performed work was a contract for services rather than a contract of employment;

contravened sections 90(2) and 323 of the Fair Work Act by failing to make payments with respect to accrued but untaken annual leave;

contravened section 4(2)(a) of the Long Service Leave Act 1955 (NSW) by failing to make payments with respect to long service leave; and

failed to make superannuation contributions so as to avoid liability for the payment of a superannuation guarantee charge with respect to a superannuation guarantee shortfall arising under the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (the “Superannuation Guarantee Act”).

8 It is sufficient for present purposes to note that ss 90 and 357 of the Fair Work Act apply in respect to an “employee”; s 4 of the Long Service Leave Act applies in respect to a “worker”, a term defined is s 3 as referring to a “person employed”; and the Superannuation Guarantee Act refers to an “employee”, albeit a term further defined in s 12 as including a person working “under a contract that is wholly or principally for the labour of the person”.

9 It is respectfully concluded that Dr Moffet was not engaged as an employee.

EMPLOYEE OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR – A SUMMARY OF PRINCIPLES

10 There was substantial agreement between Counsel for Dr Moffet and Dental Corporation as to the principles to be applied when determining whether an individual is an employee. To a great extent, the parties agreed on an analysis which focussed on a dichotomy between whether a person was an employee or an independent contractor. That dichotomy to some extent is useful – but the principal question is not to force a person into one category or another but rather to determine whether the person is an “employee” or not.

11 The distinction between an employee and an independent contractor nevertheless remains a useful distinction. It was endorsed by Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ in Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 44 at [40], (2001) 207 CLR 21 at 39 (“Hollis”). In doing so their Honours there observed (at 38 to 39):

[39] In Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd v Producers and Citizens Co-operative Assurance Co of Australia Ltd [(1931) 46 CLR 41], Dixon J explained the dichotomy between the relationships of employer and employee, and principal and independent contractor, in a passage which has frequently been referred to in this Court. His Honour explained that, in the case of an independent contractor:

“[t]he work, although done at [the principal’s] request and for his benefit, is considered as the independent function of the person who undertakes it, and not as something which the person obtaining the benefit does by his representative standing in his place and, therefore, identified with him for the purpose of liability arising in the course of its performance. The independent contractor carries out his work, not as a representative but as a principal.”

[40] This statement merits close attention. It indicates that employees and independent contractors perform work for the benefit of their employers and principals respectively. Thus, by itself, the circumstance that the business enterprise of a party said to be an employer is benefited by the activities of the person in question cannot be a sufficient indication that this person is an employee. However, Dixon J fixed upon the absence of representation and of identification with the alleged employer as indicative of a relationship of principal and independent contractor. These notions later were expressed positively by Windeyer J in Marshall v Whittaker’s Building Supply Co. His Honour said that the distinction between an employee and an independent contractor is “rooted fundamentally in the difference between a person who serves his employer in his, the employer’s, business, and a person who carries on a trade or business of his own”. In [Northern Sandblasting Pty Ltd v Harris (1997) 188 CLR 313 at 366], McHugh J said:

“The rationale for excluding liability for independent contractors is that the work which the contractor has agreed to do is not done as the representative of the employer.”

(footnotes omitted)

12 Although this may be the distinction between an employee and an independent contractor, there is no one defining factor which places a person into one category or the other.

13 Prior emphasis upon the degree of control that may be exercised over a person engaged to do work by the person who engages them has been replaced by now considering “the totality of the relationship between the parties”: Stevens v Brodribb Sawmilling Co Pty Ltd (1986) 160 CLR 16 at 29 (“Brodribb”). Mason J there started his analysis with the following observation (at 24):

A prominent factor in determining the nature of the relationship between a person who engages another to perform work and the person so engaged is the degree of control which the former can exercise over the latter. It has been held, however, that the importance of control lies not so much in its actual exercise, although clearly that is relevant, as in the right of the employer to exercise it: Zuijs v. Wirth Bros. Pty. Ltd. [(1955) 93 CLR 561 at 571]; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v. Barrett [(1973) 129 CLR 395 at 402]; Humberstone v Northern Timber Mills [(1949) 79 CLR 389 at 404]. … But the existence of control, whilst significant, is not the sole criterion by which to gauge whether a relationship is one of employment. The approach of this court has been to regard it merely as one of a number of indicia which must be considered in the determination of that question … Other relevant matters include, but are not limited to, the mode of remuneration, the provision and maintenance of equipment, the obligation to work, the hours of work and provision for holidays, the deduction of income tax and the delegation of work by the putative employee.

His Honour continue his analysis as follows (at 28 to 29):

It is said that a test which places emphasis on control is more suited to the social conditions of earlier times in which a person engaging another to perform work could and did exercise closer and more direct supervision than is possible today. And it is said that in modern post-industrial society, technological developments have meant that a person so engaged often exercises a degree of skill and expertise inconsistent with the retention of effective control by the person who engages him. All this may be readily acknowledged, but the common law has been sufficiently flexible to adapt to changing social conditions by shifting the emphasis in the control test from the actual exercise of control to the right to exercise it, “so far as there is scope for it”, even if it be “only in incidental or collateral matters”: Zuijs v. Wirth Bros. Pty. Ltd. [(1955) 93 CLR 561 at 571]. Furthermore, control is not now regarded as the only relevant factor. Rather it is the totality of the relationship between the parties which must be considered.

Justices Wilson and Dawson there similarly observed (at 36):

In many, if not most, cases it is still appropriate to apply the control test in the first instance because it remains the surest guide to whether a person is contracting independently or serving as an employee. That is not now a sufficient or even an appropriate test in its traditional form in all cases because in modern conditions a person may exercise personal skills so as to prevent control over the manner of doing this work and yet nevertheless be a servant: Montreal v. Montreal Locomotive Works [[1947] 1 DLR 161 at 169]. This has led to the observation that it is the right to control rather than its actual exercise which is the important thing (Zuijs v. Wirth Bros. Pty. Ltd. [(1955) 93 CLR 561 at 571] but in some circumstances it may even be a mistake to treat as decisive a reservation of control over the manner in which work is performed for another. That was made clear in Queensland Stations Pty. Ltd. v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [(1945) 70 CLR 539 at 552], a case involving a droving contract in which Dixon J. observed that the reservation of a right to direct or superintend the performance of the task cannot transform into a contract of service what in essence is an independent contract.

Their Honours continued (at 36 to 37):

The other indicia of the nature of the relationship have been variously stated and have been added to from time to time. Those suggesting a contract of service rather than a contract for services include the right to have a particular person do the work, the right to suspend or dismiss the person engaged, the right to the exclusive services of the person engaged and the right to dictate the place of work, hours of work and the like. Those which indicate a contract for services include work involving a profession, trade or distinct calling on the part of the person engaged, the provision by him of his own place of work or of his own equipment, the creation by him of goodwill or saleable assets in the course of his work, the payment by him from his remuneration of business expenses of any significant proportion and the payment to him of remuneration without deduction for income tax. None of these leads to any necessary inference, however, and the actual terms and terminology of the contract will always be of considerable importance.

14 The relationship between the parties, and an aspect of the extent to which one person can exercise control over another, nevertheless remains the extent to which one party can give directions with respect to, or exercise control over, the manner in which services are performed. An ability to give such directions or exercise such control, it has been concluded, is indicative of a relationship of employment. In the decision relied upon by Mason J in Brodribb, namely Zuijs v Wirth Brothers Pty Ltd (1955) 93 CLR 561 (“Zuijs”), Dixon CJ, Williams, Webb and Taylor JJ referred to earlier decisions in which the conclusion had been reached that services had been performed under a contract of service and continued (at 570):

Be those cases right or wrong upon the facts, a false criterion is involved in the view that if, because the work to be done involves the exercise of a particular art or special skill or individual judgment or action, the other party could not in fact control or interfere in its performance, that shows that it is not a contract of service but an independent contract.

It was in recognition that some services required considerable degrees of skill or expertise or professional judgment that their Honours continued on to observe (at 571) that:

[t]he duties to be performed may depend so much on special skill or knowledge or they may be so clearly identified or the necessity of the employee acting on his own responsibility may be so evident, that little room for direction or command in detail may exist. But that is not the point. What matters is lawful authority to command so far as there is scope for it. And there must always be some room for it, if only in incidental or collateral matters.

15 Another aspect of the relationship between the parties, being an aspect of the “totality” of their relationship, is the terms of any contract between them. In Brodribb (1986) 160 CLR at 37, Wilson and Dawson JJ regarded “the actual terms and terminology of the contract” to be of “considerable importance”. But the terms of any contract is but one of the aspects to be taken into account and it follows that the terms of a contract are not conclusive. In Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 37, (2015) 228 FCR 346 at 377 to 378 (“Quest South Perth Holdings”), North and Bromberg JJ summarised the position as follows:

[137] The many and varied ways in which the labour of an individual may be provided to an end-user have facilitated the provision of labour through arrangements which do not create an employment relationship between the provider and the end-user. The use of such arrangements may be real or artificial. Where artificial, the external form, appearance or presentation of the relations between the parties may cloak or conceal either an underlying employment relationship or the identity of the true employer. This is what is commonly referred to as a disguised employment.

[138] The use of disguised employment has been the subject of a great deal of commentary. …

…

[142] The prevalence of disguised employments may serve to explain why appellate courts in Australia and the United Kingdom have been particularly alert, when determining whether a relationship is one of employment, to ensure that form and presentation do not distract the Court from identifying the substance of what has been truly agreed. It has been repeatedly emphasised that courts should focus on the real substance, practical reality or true nature of the relationship in question.

[143] In looking to the reality of the situation and in determining what it is that has truly been agreed, it is necessary to ensure that the conclusion reached coheres with applicable principles of contract law.

[144] Sometimes, a disparity between what is presented on the face of the contract and the reality of what has truly been agreed, is explained by the existence of a sham or a pretence.

(citations omitted)

The agreement of the parties as to “the kind of contract by which services are to be provided” and a declaration in the contract to that effect “is not determinative of [the parties] relationship”: ACE Insurance Ltd v Trifunovski [2013] FCAFC 3 at [11], (2013) 209 FCR 146 at 149 per Lander J (“ACE Insurance”). The parties to a contract “‘… cannot alter the truth of that relationship by putting a different label on it’ … even if the label is added in good faith and with the desire that it should be effective”: Ansett Australia Holdings Ltd v International Air Transport Association [2006] VSCA 242 at [88], (2006) 60 ACSR 468 at 491 per Nettle JA (as his Honour then was) (Bongiorno AJA agreeing).

16 But where there is uncertainty as to the proper characterisation of the relationship, recourse may be had to the terms agreed between the parties as an aid to resolving that uncertainty: Massey v Crown Life Insurance Co [1978] 1 WLR 676 at 679. Lord Denning MR there observed:

The law, as I see it, is this: if the true relationship of the parties is that of master and servant under a contract of service, the parties cannot alter the truth of that relationship by putting a different label upon it. …

On the other hand, if the parties’ relationship is ambiguous and is capable of being one or the other [ie a relationship of master and servant or employer and independent contractor], then the parties can remove that ambiguity, by the very agreement itself which they make with one another. The agreement itself then becomes the best material from which to gather the true legal relationship between them.

In reliance upon these observations, Bromberg J in Australian Education Union v Victoria (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development) [2015] FCA 1196, (2015) 239 FCR 461 at 490 observed:

[90] The parties’ characterisation of their agreement may not be given effect according to its terms where the characterisation contradicts the nature of the relationship the parties have actually created: Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd (2015) 228 FCR 346 at [148] (North and Bromberg JJ). But here, the characterisation made by the parties of the Recipient Agreement is consonant with its terms. If there was ambiguity it would follow that the parties’ characterisation of their own agreement would be relevant. If the nature of an agreement is ambiguous, the parties’ characterisation can remove that ambiguity: Australian Mutual Provident Society v Allan (1978) 52 ALJR 407 at 409; 18 ALR 385 at 389 (Lord Fraser of Tullybelton, for the Privy Council), citing Lord Denning MR in Massey v Crown Life Insurance Company [1978] 1 WLR 676 at 679. As Lord Denning MR said in the passage cited:

The agreement itself then becomes the best material from which to gather the true legal relationship …

See also: ACT Visiting Medical Officers Association v Australian Industrial Relations Commission [2006] FCAFC 109 at [32], (2006) 153 IR 228 at 236 to 237 per Wilcox, Conti and Stone JJ; Australian Mutual Provident Society v Chaplin (1978) 18 ALR 38 at 389 per Lord Fraser (for the Privy Council) (“Chaplin”).

17 In addition to considering these two aspects of the relationship between the parties – namely the degree of control or the extent to which directions can be given as to the manner in which services are to be provided and the terms of the contractual arrangement between them – other aspects of the “totality of the relationship” have been referred to in Brodribb by Mason J ((1986) 160 CLR at 24) and Wilson and Dawson JJ ((1986)160 CLR at 36 to 37).

18 One of the matters referred to by Mason J and by Wilson and Dawson JJ in Brodribb was the manner in which tax liability was dealt with. This matter, like other considerations, is but one of the matters to be taken into account and nowadays must take into account the reality of the manner in which the taxation system is administered: Tattsbet Ltd v Morrow [2015] FCAFC 62, (2015) 233 FCR 46 at 63 to 64 (“Tattsbet”). Jessup J (with whom Allsop CJ and White J agreed) there observed:

[70] … in contemporary Australia, it is impossible to ignore, and difficult to depreciate, the taxation implications of the mode of operation which parties to a relationship have voluntarily adopted. In the past, the deduction of what are now called PAYG instalments was always treated, uncontroversially, as indicative of an intention that the relationship in question was one of employment. To any suggestion that the absence of such instalments tended to point to the relationship being one of principal and independent contractor, it was often rejoined that such an argument was circular, in the sense that a consequence of the relationship being one of employment was, under legislation, that such instalments had to be deducted. In contemporary times, however, there are legislative markers on both sides, as it were. It is no longer just the absence of PAYG deductions that may make it more difficult to characterise the relationship as one of employment, it is the presence of GST collections by the putative contractor, and his or her compliance with the regulatory requirements which apply to the provision of services by persons who are not employees, that point quite strongly against the relationship being characterised in this way.

(emphasis in original)

19 In addition to the considerations provided in Brodribb, the Australian Industrial Relations Commission in Abdalla v Viewdaze Pty Ltd (2003) 122 IR 215 reviewed the authorities and provided the following summary of principles (at 228 to 231):

Summary of the law on distinguishing employees from independent contractors

[34] Following Hollis v Vabu, the state of the law governing the determination of whether an individual is an employee or an independent contractor may be summarised as follows:

(1) Whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor turns on whether the relationship to which the contract between the worker and the putative employer gives rise is a relationship where the contract between the parties is to be characterised as a contract of service or a contract for the provision of services. The ultimate question will always be whether the worker is the servant of another in that other’s business, or whether the worker carries on a trade or business on his or her own behalf: that is, whether, viewed as a practical matter, the putative worker could be said to be conducting a business of his or her own. This question is answered by considering the totality of the relationship.

(2) The nature of the work performed and the manner in which it is performed must always be considered. This will always be relevant to the identification of relevant “indicia” and the relative weight to be assigned to various “indicia” and may often be relevant to the construction of ambiguous terms in the contract.

(3) The terms and terminology of the contract are always important and must be considered. However, in so doing, it should be borne in mind that parties cannot alter the true nature of their relationship by putting a different label on it. In particular, an express term that the worker is an independent contractor cannot take effect according to its terms if it contradicts the effect of the terms of the contract as a whole: that is, the parties cannot deem the relationship between themselves to be something it is not. Similarly, subsequent conduct of the parties may demonstrate that relationship has a character contrary to the terms of the contract. If, after considering all other matters, the relationship is ambiguous and is capable of being one or the other, then the parties can remove that ambiguity by the very agreement itself which they make with one another.

(4) Consideration should then be given to the various “indicia” identified in Brodribb and the other authorities bearing in mind that no list of indicia is to be regarded as comprehensive and the weight to be given to particular indicia will vary according to the circumstances. Where a consideration of the “indicia” points one way or overwhelmingly one way so as to yield a clear result, the determination should be in accordance with that result. For ease of reference we have collected the following list of “indicia”:

• Whether the putative employer exercises, or has the right to exercise, control over the manner in which work is performed, place of work, hours of work and the like

…

• Whether the worker performs work for others (or has a genuine and practical entitlement to do so)

…

• Whether the worker has a separate place of work and/or advertises his or her services to the world at large

• Whether the worker provides and maintains significant tools or equipment

…

• Whether the work can be delegated or subcontracted

…

• Whether the putative employer has the right to suspend or dismiss the person engaged

• Whether the putative employer presents the worker to the world at large as an emanation of the business

…

• Whether income tax is deducted from remuneration paid to the worker

• Whether the worker is remunerated by periodic wage or salary or by reference to completion of tasks

…

• Whether the worker is provided with paid holidays or sick leave

• Whether the work involves a profession, trade or distinct calling on the part of the person engaged

…

• Whether the worker creates goodwill or saleable assets in the course of his or her work

• Whether the worker spends a significant portion of his remuneration on business expenses

This list is not exhaustive. Features of the relationship in a particular case which do not appear in this list may nevertheless be relevant to a determination of the ultimate question.

(5) If the indicia point both ways and do not yield a clear result the determination should be guided primarily by whether it can be said that, viewed as a practical matter, the individual in question was or was not running his or her own business or enterprise with independence in the conduct of his or her operations as distinct from operating as a representative of another business with little or no independence in the conduct of his or her operations.

(6) If the result is still uncertain then the determination should be guided by “matters which are expressive of the fundamental concerns underlying the doctrine of vicarious liability” including the “notions” referred to in [41] and [42] of Hollis v Vabu.

(footnotes omitted)

20 The question of whether a person is properly characterised as an “employee” is thus not to be resolved by a mechanical reference or application of a “check list” of considerations: cf. Hall (Inspector of Taxes) v Lorimer [1992] 1 WLR 939 at 944 (“Lorimer”). Mummery J there said:

It is clear from [the] cases that there is no single satisfactory test governing the question whether a person is an employee or is self-employed. …

In order to decide whether a person carries on business on his own account it is necessary to consider many different aspects of that person’s work activity. This is not a mechanical exercise of running through items on a check list to see whether they are present in, or absent from, a given situation. The object of the exercise is to paint a picture from the accumulation of detail. The overall effect can only be appreciated by standing back from the detailed picture which has been painted, by viewing it from a distance and by making an informed, considered, qualitative appreciation of the whole. It is a matter of evaluation of the overall effect of the detail, which is not necessarily the same as the sum total of the individual details. Not all details are of equal weight or importance in any given situation. The details may also vary in importance from one situation to another.

Justice Katzmann has referred with approval to the latter part of these observations in the context of considering contraventions of the Fair Work Act: Fair Work Ombudsman v Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1034 at [42], (2016) 152 ALD 209 at 219.

THE ACQUISITION AGREEMENT & THE SERVICES AGREEMENT

21 Albeit but one of the aspects of the totality of the relationship between Dental Corporation and Dr Moffet, the terms of their contractual relationship remains a matter of some importance.

22 The Acquisition Agreement is a document of some considerable length, it being a document of some 174 pages. The Services Agreement is a comparatively more modest document, it being only some 24 pages in length.

23 After the Services Agreement came to an end in 2012:

Dr Moffet continued to perform services pursuant to terms that had been agreed; and

steps that were pursued in around August 2014 to negotiate a further agreement failed and Dr Moffet resigned in November 2014.

It is primarily the terms of the Services Agreement which assumes relevance; but consideration should also be directed to the terms upon which Dr Moffet continued to provide services up to November 2014 and the letter of resignation.

The Acquisition Agreement

24 Although it was primarily the terms of the Services Agreement which was the focus of submissions, some provisions of the Acquisition Agreement also assumed relevance.

25 The Acquisition Agreement provided in cl 3.1 for the sale of “the Assets”, a term defined by cl 1.1 as follows:

Assets means:

(a) Goodwill;

(b) Plant and Equipment;

(c) Stock;

(d) Existing Property Leases;

(e) Vendor IP;

(f) Systems;

(g) Statutory Licences;

(h) Existing Services Agreements;

(i) Records; and

(j) all other property, rights and assets of the Vendor used in the Practice,

but does not include the Excluded Assets.

26 Clause 4.3 provided (inter alia) for the payment of $2,127,998 to Dr Moffet.

27 Clause 12.1 provided for an offer of employment to be made to the existing employees of Dr Moffet to take effect on the date of completion.

28 Clause 20.2 provided for a restraint on the activities that could be pursued by Dr Moffet after entering into the Acquisition Agreement. For the purposes of that clause, Dr Moffet was defined as “Vendor” and as a “Prohibited Person”. That clauses provided as follows:

The Vendor undertakes to the Purchaser that the Prohibited Persons will not:

(a) engage in any business, activity or services which:

(i) are the same or similar to the whole or any part or parts of the Practice or Dentistry Services provided under the Services Agreement; and

(ii) which are in competition with the Practice or any material part of it;

(b) solicit, canvass, approach or accept any approach from any person who was at any time prior to the Completion Date a customer of the Practice with a view to obtaining the custom of that person in a business that is the same or similar to the Practice and is in competition with the Practice;

(c) interfere with the relationship between the Practice and its customers, employees or suppliers; or

(d) induce or assist in the inducement of any employee of the Purchaser to leave that employment.

The Services Agreement

29 The Services Agreement was an agreement between Dental Corporation, Dr Moffett (identified as the “Practice Principal”) and Immediate Dental (identified as the “Service Company”).

30 Some of its provisions assumed greater prominence in submissions than others, although the Agreement (of course) should be read as a whole.

31 Clause 3.2 of the Services Agreement set forth the “[s]ervice standard” to be provided by Dr Moffet and cl 3.3 set forth his “Practice obligations” as follows:

The Practice Principal, or the Service Company where relevant, must ensure that the Practice Principal:

(a) performs all of the obligations under, and acts in accordance with, this agreement;

(b) uses best efforts to do all things necessary to give full effect to this agreement;

(c) refrains from doing anything that may hinder performance of this agreement;

(d) acts with all due care and skill and to the best of the Practice Principal’s knowledge and expertise, and to the standard expected of a dentist experienced in the provision of services similar to the Dentistry Services;

(e) acts in compliance with all applicable laws; and

(f) acts in a manner consistent with the best interests of the Practice.

Clause 3.5 imposed upon Dr Moffet an obligation to undertake “continuing professional education” and cl 3.6 imposed an obligation to “[m]aintain patient records”.

32 Clause 6 of the Services Agreement set forth the obligation of Dental Corporation to provide “Administrative Services” as follows:

6.1 Provision of Administrative Services

In consultation with the Practice Principal, Dental Corporation will provide the Administrative Services to the Practice Principal during the Term to the extent reasonably required to enable the Practice Principal to fulfil his or her obligations under clause 3.2.

6.2 Service standard

Dental Corporation must ensure that the Administrative Services are provided:

(a) to the extent which is reasonably required by the Practice Principal to enable him or her to operate and manage the Practice in a manner which is at least consistent with the standard of the administrative services and support that the Practice enjoyed immediately prior to Completion and any upgrades agreed as necessary to support cash flow growth in the Practice;

(b) in accordance with the terms and scope of this agreement; and

(c) in accordance with all applicable laws.

6.3 Capital investment

(a) At the request of the Practice Principal, Dental Corporation will acquire equipment or other assets reasonably required for the conduct of the Practice.

(b) Other than in respect of personal or lap top computers, the costs of any asset acquisitions made by Dental Corporation under clause 6.3(a) (Capital Investment Costs) will be charged to the Practice at a notional leasing cost as if the relevant asset had been acquired under a lease, using Dental Corporation’s prevailing bank debt interest rate and amortised over the useful life of the asset up to a maximum of five years.

“Administrative Services” is defined in cl 1.1 as follows:

Administrative Services means the head office and all other administrative services provided by Dental Corporation including information technology services, equipment support, recruitment support, accounting and group marketing in accordance with clause 6.

Clause 7 provided for the employment by Dental Corporation of “Employees” as follows:

7. Employees

(a) In consultation with the Practice Principal, Dental Corporation will employ Employees in the Practice where reasonably required to enable the Practice Principal to perform his or her obligations under this agreement.

(b) Dental Corporation will be responsible for paying the Employee Remuneration to the Employees.

The term “Employee” was defined by cl 1.1 as follows:

Employee means a person employed by Dental Corporation to provide assistance to the Practice Principal at the Practice.

33 Clause 8 provided for payments to be made by Dental Corporation to Dr Moffet. Clause 8.4 provided for the payment by Dr Moffet of “[t]axes and superannuation” as follows:

8.4 Taxes and superannuation

The Practice Principal shall be solely responsible for all taxes, superannuation or other withholdings or contributions which may be payable out of, or as a result of the receipt by the Practice Principal of the Annual Dental Draw, Performance Bonus or other monies paid or payable in respect of the Dentistry Services payable by Dental Corporation. To the extent required, Dental Corporation may deduct from the Annual Dental Draw any amounts required to meet any obligation to make superannuation contributions.

34 Clause 9 provided for the payment of “Performance Bonus[es]” and for the reduction in the amounts paid by Dental Corporation to Dr Moffet in the event of an “Annual Cash Flow Shortfall”. That clause provided as follows:

9.1 Performance Bonus

The Practice Principal will be paid a bonus payment for any increases in the Annual Cash Flow generated by the Practice each Anniversary Year calculated under item 4 of Schedule 2 (Performance Bonus).

9.2 Payment of Performance Bonus

Dental Corporation will pay the Performance Bonus to the Practice Principal 30 days after the end of each Anniversary Year.

9.3 Annual Cash Flow Shortfall

The parties acknowledge that the Practice is expected to generate an Annual Cash Flow each Anniversary Year which is equal to or greater than the Minimum Annual Cash Flow. If the Annual Cash Flow is determined to be less than the Minimum Annual Cash Flow in any Anniversary Year, the Practice Principal agrees that each payment by Dental Corporation of the Monthly Dental Draw in the subsequent Anniversary Year will be reduced by 50% each month until Dental Corporation has recovered the Cash Flow Shortfall.

35 Clause 14 of the Services Agreement set forth the nature of the “relationship” between Dr Moffet and Dental Corporation as follows:

14.1 Relationship

This agreement does not create a relationship of employment, trust, agency or partnership between the parties.

14.2 Practice Principal’s independence

Dental Corporation must at all times respect the independence of the Practice Principal and will not interfere with or seek to influence the Practice Principal’s professional judgement in relation to the provision of the Dentistry Services.

The further terms of services – 2012 to 2014

36 The five year period of the Services Agreement came to an end in November 2012.

37 Towards the end of 2012, there was an exchange of emails between Dr Moffet and representatives of Dental Corporation.

38 The position of Dr Moffet was that by that time he did not want to work “harder”. His position was outlined as follows in an email sent to Mr David Bonham, Director – Finance and Services on 13 December 2012 (without alteration):

Last year, year 5, I worked 150 days. Year 4 I worked 165.

Dollars per day were down from $11K to $9K.…

There seems to be less out there…the GFC…I don’t know…the phone isn’t ringing…what are others doing.

I worked solid 4 days per week from June 25 thru to October 31….18 weeks solid…

This was my disagreement with one of Ray’s proposals…I can’t accept a number higher than year 5 in a contracting economy…and I don’t want to work harder in year 6…I’ve done my time…

See attachment…was working on this up to 2 weeks prior to November 1…when laptop crashed…not quite complete…

Mr Bonham responded the following day as follows (without alteration):

OK, thanks DM. this is really good data.

My very quick analysis is attached using your base spread sheet. See lines 22-23.

Looks like your revenue peaked per day at $10,285, and a low of $8,173.

So, next steps, how many days (roughly) do you expect/pan to work in the 12 months to 31 Oct13?

My views would be 120 days, being 40 weeks x 3 days, and also seems consistent with your last 4-5 years.

So, 120 days at $8k (last year’s run rate) = $960k. I can see your logic from earlier emails.

I am good to go with a minimum of $900k, which gives a buffer of $60k.

39 There the email exchange seems to have relevantly ended. Dr Moffet continued to provide dental services after the expiration of the Services Agreement until he resigned in November 2014.

40 Towards the end of 2014, however, steps were pursued with a view to entering into a further agreement.

41 The terms the subject of discussion were outlined on behalf of Dental Corporation in an email from Mr Bonham to Dr Moffet on 27 August 2014 relevantly as follows (without alteration):

As discussed, it looks like it would be more aligned for us all to move to a profit share model for Active Dental.

Consequently, I have modelled 4 different scenarios, each increasing in revenue, to reflect what I think would be base case as starting position, and growing each time to what may well be achievable with extra providers.

Per attached, key points to review:

1. Revenue per each dental provider and whether you think these are reasonable and something to work towards

2. Cost structures and alignment

3. Profit share.

a. This means DM doesn’t get paid dental draw, but instead a share of the monthly profit.

b. Have put three hurdles in:

i. First $240k = 50%

ii. $240k+ = 60%

c. You will note that in each scenario, revenue increases for the practice in steps from $1.5m pa to $2.5m pa, and your profit share also steps from $303k per annum up to $588k.

Other terms to review and agree:

A. 3 year agreement commencing 1 Oct 2014 (to be agreed)

B. Either side can give 6 months’ notice to terminate

C. DM to be given a capital allowance amount to rectify works undertaken in the last 6 months to bring site back to his requirements = maximum $50k

a. This does not include replacing any chairs that do not support DM because they are not ambidextrous / suitable for a left handed practitioner. DC will carry this cost over and above the allowance

D. DC to provide a marketing contribution = $20k. No costs to the practice.

But the negotiations did not proceed further and no further agreement was executed.

The letter of resignation – November 2014

42 Dr Moffet resigned from Dental Corporation on 21 November 2014. His letter of resignation stated as follows (omitting formal parts and without alteration):

I will be absent from Active Dental over Christmas on a family holiday.

I am due back at Parramatta on Wednesday January 21 2015.

This letter serves as a notice in advance that I will not be returning from this vacation.

Please consider this letter my Letter of Resignation.

The events of the past eleven months have taken their toll on my health.

The behaviours and actions of your employees, in particular, Gordon Towell, Joanna Kelton, Alison Coates, Mark Psillarkis and Chris Papas have been despicable and deplorable.

Dental Corporation has documentation of my complaints and objections to their behaviours.

In particular, the bullying behaviours and emails from Alison Coates and Mark Psillarkis, and the abusive phone comments from Mark Psillarkis in June are embedded in my mind.

The deceiptful actions of Joanna Kelton are also abhorrent to me.

My complaints and concerns have been brushed aside, as if nothing ever happened.. I am still receiving treatment for the medical issues arising from their behaviours.

Despite my best efforts to rectify and reverse the unwanted and totally unnecessary and uncalled for physical changes to Active Dental, I have come up against untruths propagated by Chris Papas that have delayed their progress.

As such, five months on from the departure of Psillarkis and Coates from Parramatta, there is still no place to wash dishes and glassware with hot water, there is still no staff room area, there are still huge holes in our fire-rated ceiling…the list goes on…

Despite their disgusting behaviours, Coates, Papas and Kelton still hold positions of tenure in your organisation.

The strain and pressure of these above actions and behaviours have carried through to my home environment, where they have no doubt had an unsettling impact on my son’s HSC preparations.

As such, enough is enough.

It saddens me to leave Active Dental under such circumstances.

I was hopeful to have made some recovery by now. However, recovery is too slow.

And I cannot commit to the terms of a contract the likes of which you have suggested.

And as if the above events have never happened.

As such, I will not be entering into any further agreement with Dental Corporation.

THE STATUS OF MOFFET AS AN INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR

43 Although it was common ground between the parties that it was the “totality” of the relationship between Dr Moffet and Dental Corporation that had to be assessed, there was a divergence of views as to what the “totality” of that relationship exposed. Needless to say, Counsel for each of the opposing parties relied upon different aspects of that relationship or sought to place different emphasis upon aspects of that relationship. Both parties filed written Outlines of Submissions.

44 In advancing his submission that Dr Moffet was an employee rather than an independent contractor, Counsel for Dr Moffet in his written Outline of Submissions focussed attention upon:

the Services Agreement requiring Dr Moffet “to provide personal service … and to perform work personally”;

a contention that Dr Moffet “was not undertaking or conducting his own business, but rather working for the business” of Dental Corporation;

the fact that although Dr Moffet “had some discretion in relation to hours of work, [Dr Moffet] was engaged on a permanent ongoing basis during the term of the Services Agreement”;

the contention that Dr Moffet “was not merely providing dentistry services to the practice now owned by [Dental Corporation], but was an integral part of … managing and operating the … practice”;

a submission that Dr Moffet “did not have control over the operation of the practice in a manner that would be indicative of him operating his own business”;

the fact that Dental Corporation “was required to by the Service Agreement, and did in fact, procure, provide and maintain all equipment necessary for the operation of the practice and the performance of work by” Dr Moffet;

the submission that Dr Moffet “was held out to third parties as a representative of and emanation of the practice owned and operated by” Dental Corporation;

the submission that although Dr Moffet “obviously retained a degree of professional judgment and discretion in relation to his dental work, [he] was subject to supervision and control by representatives of [Dental Corporation] in relation to the work he performed and in relation to the performance of the practice”; and

the fact that Dental Corporation “at all times superintended the finances of [Dr Moffet] and the payments made to the application [sic] for the performance of work”.

45 Although accepting that it was the “totality of the relationship” that had to be considered, Counsel for Dental Corporation focussed specific attention in their written Outline of Submissions on two aspects of that relationship, namely:

the asserted “absence of a right of [Dental Corporation] to exercise any real degree of control over the manner in which [Dr Moffet] performed the services that he had agreed to provide”; and

“the degree to which [Dr Moffet] participated in the GST system”.

46 Although it is readily accepted that different minds may draw a different conclusion from the facts presented (cf. ACT Visiting Medical Officers Association v Australian Industrial Relations Commission [2006] FCAFC 109 at [28], (2006) 153 IR 228 at 235 to 236 per Wilcox, Conti and Stone JJ), it is respectfully considered that the “totality” of the relationship (cf. Brodribb (1986) 160 CLR at 29 per Mason J) or the “reality of the situation” (cf. Quest South Perth Holding [2015] FCAFC 37 at [143], (2015) 228 FCR at 378 per North and Bromberg JJ) was that after the acquisition of his dental practice in 2007, Dr Moffet was retained by Dental Corporation as an independent contractor.

47 In reaching that conclusion, a number of different aspects of the evidence should be more fully developed. It will be noted that some of the submissions and contentions advanced on behalf of Dr Moffet were not borne out by the facts.

The contractual relationship – its evolution & what was absent

48 The steps preceding the execution of the Acquisition Agreement and the Services Agreement in November 2007 were but part of a larger strategy being pursued by Dental Corporation to acquire and grow the top 30-40% of dental practices in Australia that were turning over approximately $2 million per year.

49 The rationale for the business, as explained by one of the co-founders of Dental Corporation (Mr Mark Evans), was to assist the dentistry practices with the administrative side of running their practices so that the dentists could focus on dentistry and operate more effectively. The way in which this was to be implemented was explained by Mr Evans in his affidavit as follows:

I wanted to ensure that the dentists were independent and free to run their practice in the way they determined best because I believed that would produce better operational and financial outcomes. I did not want the dentists from whom we were buying the dentistry practices from to be employees because I had had experience with other business models that had acquired businesses and then employed the former owner to run the business for them and it had not worked. My view was and is that when someone is used to running their own business, they often find the transition to an employee difficult. We wanted the dentists to maintain their independence to ensure the success of the business.

Dr Moffet’s dental practice was one of the “early acquisitions” of Dental Corporation.

50 Prior to the execution of the two Agreements, there were a number of meetings between Dr Moffet (on the one hand) and a Dr Khouri (another founder of Dental Corporation) and Mr Evans (on the other hand). There was some uncertainty as to whether Dr Khouri and Mr Evans wanted Dr Moffet to “work back for us for five years” or whether there was a proposal that he sign an agreement to provide services for five years. But nothing much turns on that. The result was that the two Agreements were signed on 15 November 2007.

51 Prior to the execution of the two Agreements, Dr Moffet had access to legal advice and accepted that he “must have” had legal advice about the terms of those Agreements. Indeed, as Dr Moffet accepted, the Services Agreement was witnessed by his solicitor. One of the terms of the Services Agreement, of course, was cl 14.1 which expressly stated that the agreement did “not create a relationship of employment”.

52 Although reference has been made to the terms of the two Agreements, it is to be noted that no term of the Services Agreement was directed to:

the hours of work to be performed by Dr Moffet; which days or the number of days he was required to work; or the holidays he could take; and

the nature of the work to be undertaken by Dr Moffet, other than the general requirement that he provide “Dentistry Services”.

The days worked, hours worked and vacations taken by Dr Moffet

53 Dr Moffet determined for himself the hours he worked and when he worked.

54 During the course of the Services Agreement from 2007 to 2012, Dr Moffet worked at the practice four days per week and was described as the “Practice Principal”.

55 After the expiration of the Services Agreement, Dr Moffet performed services in accordance with the revised agreement negotiated via the series of emails exchanged in December 2012.

56 From December 2012 to December 2014, Dr Moffet reduced from working four days per week to three days per week. In 2011, Dr Moffet took 15 weeks’ vacation.

57 The freedom exercised by Dr Moffet as to when he worked and when he took holidays is evident from the following exchange during his cross-examination:

And at no stage were you given any direction by Dental Corporation that you had to keep the practice open on particular days between hours or something like that?––No.

No. It’s also the case that you decided the days upon which you would work. Correct?––I continued working the same days that I had before I sold to Dental Corporation.

HIS HONOUR: That’s not an answer to the question. Can you answer the question please.

MR DARAMS: You determined the days upon which you would work during the engagement with Dental Corporation?––Yes.

The cross-examination continued a little later as follows:

The 15 weeks vacation you took in 2011, you decided when you wanted to take that vacation, correct?––I decided when I was absent from the practice. Yes.

Yes. And I want to suggest to you that you didn’t seek the consent or authorisation of Dental Corporation before deciding to go on or taking that absences from the practice?––No. That wasn’t a requirement of my engagement with them.

The day-to-day operations of the dental practice

58 It should also be noted, and without being exhaustive, that it was not put in issue that both pursuant to the terms of the Services Agreement and as a matter of fact, Dr Moffet:

provided dentistry services to his patients and maintained dental records;

performed those dentistry services personally;

undertook continuing professional education, by (for example) attending seminars;

managed the practice; and

personally maintained professional indemnity insurance.

In the discharge of his responsibilities, the Services Agreement at cl 14.2 – perhaps not surprisingly – provided that Dental Corporation would not “interfere with or seek to influence” the “professional judgment” of Dr Moffet: cf. Brodribb (1986) 160 CLR at 28 to 29 per Mason J.

59 The submission advanced on behalf of Dr Moffet that he was “subject to supervision and control” by representatives of Dental Corporation is, with respect, somewhat elusive. The submission is correct if confined to such matters as:

that Dr Moffet was apparently “required” to attend meetings with a senior representative of Dental Corporation every 4 to 6 weeks “to discuss the performance of the practice”; and

the provision to Dr Moffet of monthly reports setting out the “Practice’s budget, expenses and performance” with a view to ensuring “profit and collections targets were being met”.

But there was no “supervision and control” or the giving of directions by Dental Corporation to Dr Moffet with respect to the patients he was to treat, or directions as to the nature of the services he was to perform or the amounts to be charged to clients for the services provided. Dr Moffet accepted as much during the following exchange in cross-examination:

Dental Corporation at no stage during your engagement with them did they say you could only do this type of work, or you could only do that type of work in relation to patients, did they?––That would be beyond their scope as – of ownership.

Is that a roundabout way of saying, no, they didn’t do that?––They didn’t tell me what to do and what not to do on patients. They weren’t dentists.

I know that they didn’t tell you how to do a filling or how to – is it fix a crown or put in a crown or something along those lines. I know they didn’t do that, but whether or not you could do that work or not do that work they didn’t give you any direction one way or the other in respect of that, did they?––Dental Corporation didn’t look at the diagnoses that I made on patients.

You determined what work would be carried out in relation to a particular patient, correct?––As they needed. Yes.

The patient needed?––As the patient needed.

You determined, didn’t you, whether or not you wanted to do that work for a particular patient?––As a healthcare practitioner it’s my responsibility to treat patients.

… Now, in relation to the amount that you charged or decided to charge a patient, you were the person who could dictate that amount, correct, for the services you provided?––Yes.

At no stage during your engagement did Dental Corporation say, “Here’s a list of fees that you have to charge when you do this work,” correct?––No. They never did.

Irrespective of the absence of any contractual entitlement to give directions to Dr Moffet, as a practical matter Dental Corporation did not purport to give any directions to Dr Moffet – even in respect to “incidental or collateral matters”: Zuijs (1955) 93 CLR at 571 per Dixon CJ, Williams, Webb and Taylor JJ; Brodribb (1986) 160 CLR at 29 per Mason J. The submission advanced on behalf of Dr Moffet, that he was “subject to supervision and control … in relation to the work he performed”, is rejected.

60 Similarly, it was not put in issue that Dental Corporation, pursuant to the terms of the Services Agreement and as a matter of fact:

provided administrative services to Dr Moffet; and

provided such equipment as was required to enable Dr Moffet to provide dental services.

During the course of the Services Agreement, Dental Corporation provided to Dr Moffet an office and a car space. Dr Moffet was also involved in meetings organised by Dental Corporation to deal with matters such as marketing and sales.

61 There was some evidence of the circumstances in which employees of Dental Corporation could be dismissed. The evidence was that Dental Corporation employed persons at the dental practice and ultimately made decisions on occasions to dismiss employees, albeit generally if not always on the recommendation of Dr Moffet. Although Dr Moffet maintained in his affidavit that his “general duties and responsibilities included … managing, recruiting and dismissing employees of the Practice”, the facts as they emerged were that Dr Moffet suggested on occasion that certain persons should be employed or dismissed by Dental Corporation and would appear to have sent (or drafted) letters (on occasion) dismissing employees, but those letters being on the letterhead of Dental Corporation. It is concluded that Dr Moffet retained no unilateral right to employ or dismiss employees.

62 Clause 13 of the Services Agreement provided that both Dental Corporation and Dr Moffet retained a contractual right to terminate the Agreement in certain circumstances.

Financial arrangements

63 During the course of the Services Agreement, Dr Moffet:

received remuneration calculated by reference to the monthly revenue he had generated and collected (based upon the fees he charged for the patients he had treated at the practice) and potentially an annual bonus (based upon annual cash flow generated by the practice); and

was reimbursed by Dental Corporation for expenses he had incurred in connection with providing dentistry services at the practice.

Goods and Services Tax was paid in relation to those fees. No income tax or other tax was deducted by Dental Corporation from the payments made to Dr Moffet.

64 Dr Moffet provided details to Dental Corporation of the monthly “[t]otal collection” of fees he had generated by rendering services to patients. Deducted from that total were expenses he had incurred in rendering those services. Dental Corporation then prepared a draft invoice for Dr Moffet bearing his name and Australian Business Number. The invoice provided by Dental Corporation for April 2008 (by way of example) provided in relevant part as follows:

TAX INVOICE No: 1003 | ||||||

Date | Description of Work | Amount | ||||

30/04/2008 | Total collection for April 08 | $ | 169,152.70 | |||

Less: Lab Fees for March 08 | $ | 8,852.89 | ||||

Net collection (collection less lab fees) | $ | 160,299.81 | ||||

Dr Moffet commission | 43% | |||||

Dental service commission | $ | 68,928.92 | ||||

Deferred component adjustment for April 08 | $ | 8,333.33 | ||||

Sub Total | $ | 60,595.59 | ||||

GST | $ | 6,059.56 | ||||

Total | $ | 66,655.15 | ||||

The reference in that invoice to “Lab Fees” was a reference to fees charged by external businesses which were incurred in the rendering of the dental services provided, for example for the provision of retainers, dentures and the like. The reference to the “Dental service commission” was a reference to the amount retained by Dr Moffet, which was calculated on the basis set forth in Schedule 2 to the Services Agreement.

65 During the years he was retained by Dental Corporation, it also emerged that Dr Moffet:

retained the Australian Business Number he had obtained prior to the acquisition by Dental Corporation of his practice, which was the same Australian Business Number that appeared on the invoices issued to Dr Moffet by Dental Corporation;

filed tax returns which, although representing that his “main business or professional activity” was “Dental Surgeon”, also represented that he was engaged in a number of other “business activities”; and

claimed deductions incurred in generating his income as a “Dental Surgeon”, being expenses for which he was not reimbursed by Dental Corporation.

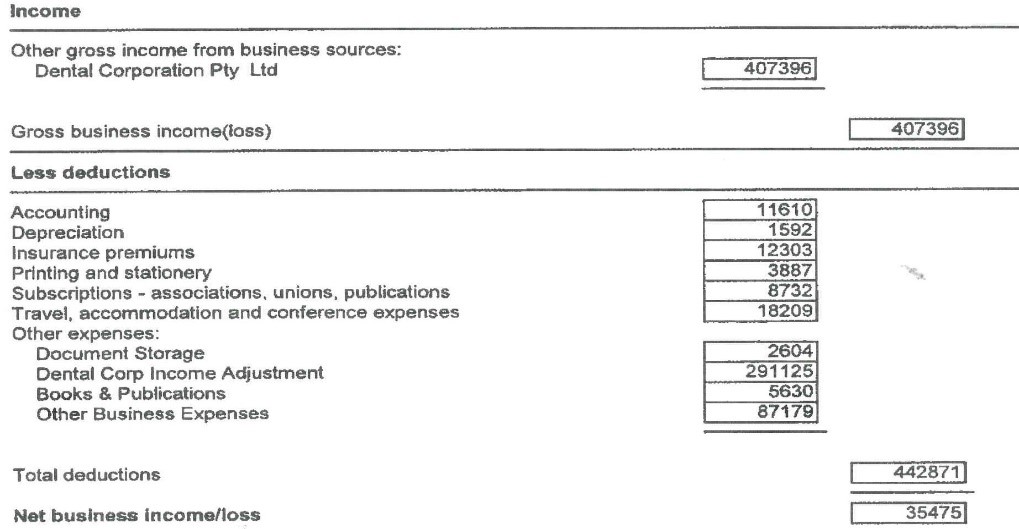

66 Considerable attention was directed by Counsel for Dental Corporation to tax returns filed by Dr Moffet. One return received particular attention and Counsel focussed on the deductions claimed by Dr Moffet. Part of that return, being for the financial year ending 30 June 2013, provided as follows:

Of present relevance is the deduction claimed for “Dental Corp Income Adjustment” of $291,125. Uncertainty as to what this amount actually represented was resolved in re-examination as follows:

on your understanding at least, [the Dental Corp Income Adjustment] that was a loss adjustment; are you able to say what you meant by “loss adjustment”?––That financial year, I was unable to produce a profit for Dental Corporation up to their target and so the shortfall was – I had to pay them back and that was part of that shortfall.

That deduction thus represented the payment by Dr Moffet of an “Annual Cash Flow Shortfall” as contemplated by cl 9.3 of the Services Agreement.

67 In addition to such documents there are also some documents generated by Dr Moffet and which in no way relate to the activities of the Dental Corporation.

68 In total, it is difficult to accept without considerable reservation, the submission advanced on behalf of Dr Moffet that he “was not undertaking or conducting his own business”. During the initial five year term of the Services Agreement and thereafter there is some evidence that Dr Moffet continued to promote his own dental practice. He thus accepted in cross-examination, when his attention was drawn to the tax return for the financial year ending June 2013, that he was “starting a consulting business”. Such an inference is also supported by the fact that during the five year term of the Services Agreement, his tax returns claimed deductions for expenses incurred in generating income as a “Dental Surgeon”, but expenses separate and discrete from those for which he was reimbursed by Dental Corporation.

69 Albeit after the expiration of the initial five year term of the Services Agreement, but whilst he was still performing services for Dental Corporation, there is no question that Dr Moffet was seeking to promote his consulting business by causing material to be published on the internet. Prior to his resignation in November 2014, it emerged that Dr Moffet:

published or caused to be published on the internet a number of articles about himself and which were written based on information he had provided.

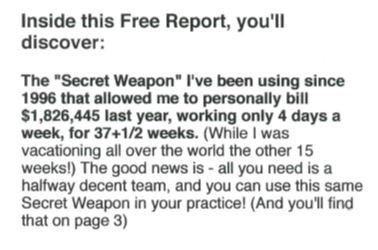

One such article was published in 2013. It stated in part as follows:

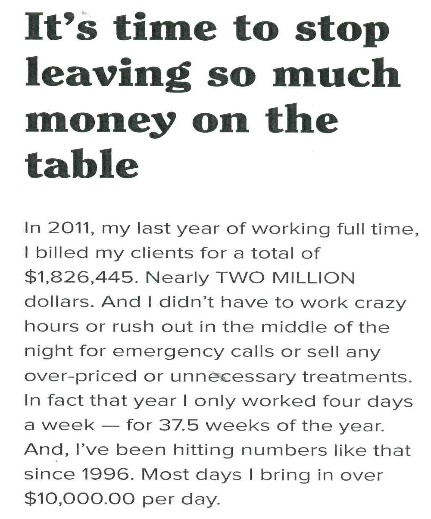

The facts there stated were repeated in a subsequent web page published more recently in 2017. That later publication stated in part as follows:

70 It may be accepted that inferences to be drawn from tax returns are but one of the matters to be taken into account and that care should be taken in too readily drawing such inferences: cf. Putland v Royans Wagga Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 910 at [26] per Bromwich J; ACE Insurance [2013] FCAFC 3 at [37], (2013) 209 FCR at 153 per Buchanan J (Lander and Robertson JJ agreeing).

71 It is, however, respectfully concluded that such documents provide some support for a conclusion that the relationship was more that of Dr Moffet being an independent contractor than employee.

The totality of the relationship – an independent contractor

72 Although some particular aspects of the relationship have received specific attention, the conclusion that Dr Moffet was retained as an independent contractor is one founded upon the “totality of the relationship” (cf. Brodribb (1986) 160 CLR at 29 per Mason J) and a consideration of what the “reality of the situation” (Quest South Perth Holdings [2015] FCAFC 37 at [143], (2015) 228 FCR at 378 per North and Bromberg JJ) was between himself and Dental Corporation.

73 Without attempting to be exhaustive and without placing to one side particular aspects of the relationship which, taken by themselves, could indicate a contrary conclusion, the conclusion that Dr Moffet was retained as an independent contractor is reached by reference to (in particular):

the terms of cl 14.1 of the Services Agreement;

the absence of any degree of control exercised or exercisable by Dental Corporation over Dr Moffet with respect to the patients he saw or the procedures he performed – no attempt being made by Dental Corporation to give directions to Dr Moffet about (for example) the performance of more expensive dental procedures or the number of the procedures he was required to perform;

the absence of any degree of control exercised or exercisable by Dental Corporation over the hours or days worked by Dr Moffet – the Services Agreement containing no term requiring Dr Moffet to attend at the dental practice on any particular day or to be in attendance for any period of time. The fact is that Dr Moffet chose for himself, free of consultation with Dental Corporation, the hours and days he attended at the dental practice, the extent to which he took holidays and the duration of those holidays; and

the absence of any intent on the part of Dental Corporation to establish an employment relationship – such a structure being seen by Mr Evans from the outset as a business model which “had not worked” in the past.

Reference may also be made to the fact that:

the monthly invoices prepared by Dental Corporation for Dr Moffet to enable payments to be made to him deducted from the fees generated from his performing procedures upon patients an amount representing the costs incurred in generating those fees (such as the monies paid to third parties for the construction of retainers, dentures and the like); and

the contractual prospect in the Services Agreement that Dr Moffet could be paid a “Performance Bonus” based on any increase in annual cash flow of the practice (cl 9.1) but, more importantly, the prospect that Dr Moffet could be exposed to a requirement to repay any “Shortfall” in the event that the annual cash flow of the practice fell below a set target (cl 9.3) – as happened in the 2012/2013 financial year, resulting in the payment of $291,125 by Dr Moffet to Dental Corporation.

Neither of these aspects of the relationship have the hallmarks of an employment relationship. An employee is normally paid a salary or hourly, daily or other periodic wage, free of deductions for expenses incurred in the performance of their work. The prospect of cash flow being less than otherwise anticipated is a risk normally borne by an employer.

74 The reality of the situation was that Dental Corporation acquired the dental practice from Dr Moffet in 2007 and thereafter let Dr Moffet continue to conduct his own business. Dr Moffet got the capital sum on the sale of the practice and, after the sale, Dental Corporation received part of the monies he thereafter generated as a contractor.

75 The reality of the relationship was that Dr Moffet continued after the acquisition of the dental practice by Dental Corporation in 2007 to run his personal practice much the same as before. He continued using his own Australian Business Number when submitting tax returns and continued trying to grow his business.

76 Clause 14.1 of the Services Agreement accurately described the relationship as not constituting an employment relationship. It did not seek to put a label upon the relationship different to that which it was in reality: cf. Massey [1978] 1 WLR at 679 per Lord Denning MR. In reaching this conclusion, however, it has not proved necessary to resolve any uncertainty or ambiguity by recourse to cl 14.1: cf. Massey [1978] 1 WLR at 679 per Lord Denning MR. Recourse to cl 14.1, it may nevertheless be noted, only reinforces the conclusion reached. During his oral evidence, Dr Moffet presented as an astute business person and he accepted that he had access to legal advice prior to executing the Services Agreement. Clause 14.1, it is considered, was a contractual term which should be given the full effect the parties presumably intended. There was no evidence that Dr Moffet did not read and understand the terms of the Services Agreement and no evidence that he did not give consideration to cl 14.1 itself.

77 Clause 14.1 of the Services Agreement, it must readily be accepted, is but one matter to be taken into account and is not “determinative”: cf. ACE Insurance [2013] FCAFC 3 at [11], (2013) 209 FCR at 149 per Lander J. No agreement can operate by reference solely to its own terms to be determinative of the nature of the relationship such as to preclude the entitlements and protections conferred by the Fair Work Act upon an “employee”: cf. Hollis [2001] HCA 44 at [58], (2001) 207 CLR at 45 per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ; Quest South Perth Holdings [2015] FCAFC 37 at [148] to [149], (2015) 228 FCR at 379 to 380 per North and Bromberg JJ. Nor can the manner in which Dr Moffet prepared and submitted his tax returns provide a complete or independently determinative description of his status: cf. ACE Insurance [2013] FCAFC 3 at [37], (2013) 209 FCR at 153 per Buchanan J (Lander and Robertson JJ agreeing). Again, these are but further matters to be taken into account.

78 In referring expressly to particular features of the relationship, care has been taken not to simply run through a “check list” of potentially relevant considerations: cf. Lorimer [1992] 1 WLR at 944 per Mummery J.

LONG SERVICES LEAVE & TERMINATION

79 The claim that Dental Corporation failed to pay Dr Moffet an amount payable for long service leave pursuant to the Long Service Leave Act is also rejected.

80 Section 4 of the Long Service Leave Act provides in part as follows:

Long service leave

(1) Except as otherwise provided in this Act, every worker shall be entitled to long service leave on ordinary pay in respect of the service of the worker with an employer. Service with the employer before the commencement of this Act as well as service with the employer after such commencement shall be taken into account for the purposes of this section.

(2)

(a) Subject to paragraph (a2) and subsection (13) the amount of long service leave to which a worker shall be so entitled shall:

…

(iii) in the case of a worker who has completed with an employer at least five years service, and whose services are terminated by the employer for any reason other than the worker’s serious and wilful misconduct, or by the worker on account of illness, incapacity or domestic or other pressing necessity, or by reason of the death of the worker, be a proportionate amount on the basis of 2 months for 10 years service.

Section 3 provides the following definition of the term “worker”:

Worker means person employed, whether on salary or wages or piecework rates, or as a member of a buttygang, and the fact that a person is working under a contract for labour only, or substantially for labour only, or as lessee of any tools or other implements of production, or as an outworker, or is working as a salesman, canvasser, collector, commercial traveller, insurance agent, or in any other capacity in which the person is paid wholly or partly by commission shall not in itself prevent such person being held to be a worker but does not include a person who is a worker within the meaning of the Long Service Leave (Metalliferous Mining Industry) Act 1963.

Section 7(2) provides that the Act applies such that “[n]o contract or agreement … shall operate to annul or vary or exclude any of the provisions of this Act”. An “employer” thus may not “contract out” of the Long Service Leave Act: Steiner v Strang [2016] NSWSC 395 at [150] per Slattery J. Section 12 provides for any “worker” to make an application to the Local Court of New South Wales or the Supreme Court of New South Wales “for an order directing the employer to pay to the worker the full amount of any payment which has become due” under the Long Service Leave Act. Notwithstanding that provision, no submission was advanced in the present case as to the jurisdiction or the appropriateness of this Court making a declaration of contravention of the State Act and making any order to give effect to any entitlement that Dr Moffet may have under that Act.

81 No different conclusion, in any event, should be reached in respect to this claim than that reached in respect to the claims made under the Fair Work Act. For the reasons already given, it is concluded that Dr Moffet was not a “worker” for the purposes of the Long Service Leave Act as he was not “employed”. Dental Corporation was not his “employer”.

82 Even if it were to be concluded that Dr Moffet was a “worker”, s 4(2)(a)(iii) of the Long Service Leave Act relevantly confines the entitlement to long service leave to a “worker” whose “services [were] terminated by the employer” or where a “worker” terminated his services “on account of illness, incapacity or domestic or other pressing necessity”.

83 Had it been necessary to do so, it would have been concluded that Dental Corporation did not terminate the services of Dr Moffet. Dr Moffet’s “Letter of Resignation” dated 21 November 2014 takes effect according to its terms. As expressed, it was a letter communicating Dr Moffet’s “Resignation”.

84 Also rejected is a submission advanced on Dr Moffet’s behalf that he “terminated” his services “on account of illness, incapacity or domestic or other pressing necessity”. The reasons given in his letter of resignation for terminating his services with Dental Corporation included (inter alia) the “despicable and deplorable” and “abhorrent” actions of some employees of Dental Corporation. Dr Moffet also claimed that he was subjected to “bullying behaviours”. However, the claims made in the 21 November 2014 letter, it is respectfully considered, are no more than unsubstantiated assertions. Without more, they cannot be considered “another pressing necessity” for the purposes of the Long Service Leave Act.

85 In his affidavit, Dr Moffet also claimed that he decided to resign because of “the negative impact to [his] physical and mental health”. However, a claim that he “terminated” his services “on account of illness” is also rejected. Had Dr Moffet wished to, for example, make good his claim that he was “still receiving treatment for the medical issues”, it would have been a simple enough task for medical evidence to that effect, from medical practitioners, to have been filed.

86 Notwithstanding the absence of any substantive cross-examination on the part of Counsel for Dental Corporation upon Dr Moffet’s evidence in his affidavit about (for example) bullying, there was no imperative upon Counsel for Dental Corporation to do so. The evidence of Dr Moffet could be left as it was and an election made by Counsel for Dental Corporation to thereafter make a submission that the evidence as it was – unchallenged – was not sufficient to make out the claim.

87 The conclusion that Dr Moffet was retained by Dental Corporation as an independent contractor and not as an employee is a conclusion largely founded upon inferences drawn from the documents in evidence rather than his oral evidence. But the rejection of the assertions made in the letter of resignation depends to some extent upon an assessment of the reliability of his oral evidence and the extent to which reliance can be placed upon what he has stated in that letter. Separate from the conclusion that there was an absence of evidence to support the assertions made in the letter is an assessment that the reliability of what Dr Moffet said and wrote was open to question. The way in which he gave answers in cross-examination gave rise to questions as to whether what he was saying could be accepted at face value. For example, when questioned whether he had taken 15 weeks holiday in 2011, Dr Moffet initially rejected the proposition. That answer, however, stood in stark contrast to the webpages published in 2013 and 2017 which suggested that he had in fact taken 15 weeks’ vacation in 2011. Given the content of those webpages, which were published on Dr Moffet’s blog, his answers in cross-examination sounded hollow indeed. Any explanation that may have been afforded by the representation having been made some five years ago was undermined by the fact that much the same statements were made in the webpage published more recently in 2017 promoting the message that “It’s time to stop leaving so much money on the table”. A further exchange in cross-examination also occasioned a like reservation as to the reliability of his evidence. This exchange focussed upon Mr Moffet’s claim to have earned “nearly TWO MILLION dollars” in 2011, his cash flow target and how many days per week he would have to work to meet that target. Dr Moffet was unwilling to accept a proposition that if he earned “nearly TWO MILLION dollars” in 2011 working four days per week, and had a cash flow target of $900,000 in 2013, all other things being equal he would have to work around half as much in 2013 to meet the target. However, Dr Moffet could provide no explanation for why he could not accept that proposition, other than that “[w]e’re talking about a two year time difference”. Such exchanges also did not sit comfortably with the more general assessment that Dr Moffet presented as a witness very conscious of the factual issues to be resolved in the present proceeding and as a witness otherwise careful and cautious in the evidence he gave and also careful in ensuring that this evidence supported his case.

SUPERANNUATION

88 Dr Moffet also claimed that Dental Corporation was required to make superannuation contributions on his behalf to avoid liability to pay a superannuation guarantee charge in accordance with the Superannuation Guarantee Act. It was accepted that no such superannuation contributions were made.

89 Section 12 of that Act provides in part as follows:

Interpretation: employee, employer

(1) Subject to this section, in this Act, employee and employer have their ordinary meaning. However, for the purposes of this Act, subsections (2) to (11):

(a) expand the meaning of those terms; and

(b) make particular provision to avoid doubt as to the status of certain persons.

…