FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus Mobile Pty Limited [2019] FCA 106

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION First Applicant RAMI GREISS Second Applicant | ||

AND: | OPTUS MOBILE PTY LIMITED (ABN 65 054 365 696) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Respondent (Optus), between 1 April 2014 and 24 August 2018, by applying charges for Direct Carrier Billing (DCB) content to the accounts of customers who had unintentionally purchased DCB content without their knowledge or consent (Non-consenting Customers):

(a) in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, represented to Non-consenting Customers that they had agreed to acquire that DCB content when they had not; and

(b) thereby made a false and misleading representation that Non-consenting Customers had agreed to acquire services in contravention of s 12DB(1)(b) of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Optus pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $10,000,000, within 14 days of the Court’s order, in respect of the contraventions declared in paragraph 1.

3. Optus pay the Applicants’ costs of and incidental to this proceeding, to be taxed if not agreed.

4. Liberty is granted to the Applicants, until 7 August 2020, to restore the proceeding in the event of any issue arising in the implementation of the customer refund program described in paragraph 75 of the parties’ Agreed Statement of Facts and Admissions. If leave to restore the proceeding is not exercised within that period, the proceeding will be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MURPHY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding the first and second applicants, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and Mr Rami Greiss, Executive General Manager, Enforcement Division of the ACCC, allege that the respondent, Optus Mobile Pty Ltd (Optus), made a false or misleading representation in trade or commerce in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, in contravention of s 12DB(1)(b) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). Optus has admitted the alleged contravention on the basis of an Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (ASAFA), and the parties have filed amended Joint Submissions seeking a declaration as to the contravention and orders for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty of $10 million and for Optus to pay the ACCC’s costs.

2 Optus is a company incorporated in Australia, wholly owned by Singtel Optus Ltd and part of the Optus group of companies (Optus Group). At all relevant times it carried on the business of promoting and supplying retail telephony and data services for mobile phones and tablets provided by the mobile network operated by Optus (mobile services). From May 2012 to 1 August 2018, the mobile services offered by Optus have enabled customers using mobile devices to use four pathways to access online software and services (digital content).

3 The first three pathways may be described as follows:

(a) for business customers – via the “Optus Smart Shop”, a web-based portal that enables business customers to purchase third party digital content after they have created an account with a password and email address. Those customers can apply to Optus to have their purchases billed to their Optus mobile account which requires them to be signed in and to provide their business address and ABN for each purchase, otherwise they must pay for each purchase by credit card;

(b) for domestic and business customers – via the web to third party “application” or “app” stores, such as Apple’s App Store or Google’s “Google Play” (app stores) that enable customers to purchase third party digital content after they have created an account directly with the app store with a password and email address. Those purchases are billed by the app store directly to the customers’ credit cards. Customers can however opt in to having purchases via Google Play billed to their Optus mobile account which requires customers to select that option and click a “buy” or “subscribe” button; and

(c) for domestic and business customers – via the Premium SMS service that enables customers to purchase third party digital content. Access to the Premium SMS service content requires a “double opt in” by the customer sending an SMS to a nominated number; then the customer receives a “subscription request” text to which the customer must respond affirmatively before subscription takes effect.

4 The proceeding concerns the fourth pathway, the Direct Carrier Billing service (DCB service) available for domestic and business customers. The DCB service enables Optus’ business and domestic customers to purchase digital content on a subscription or one-off purchase basis from a third party, and have the charges for that content billed to their Optus account. Third party digital content purchased via the DCB service (DCB content) includes “premium” content services (such as news websites), downloadable applications (such as games or ringtones) and other content (such as “voting” in television programs) not obtained via the Optus Smart Shop or an app store. The DCB service included a “Pay per view” (PPV) model under which customers were charged for each individual internet page viewed.

5 DCB content is created by Content Providers who do not have a direct relationship with Optus or the customer. Rather, their digital content offerings are compiled and marketed by third-party providers (Aggregators) who have contractual arrangements with Optus to make the content available for purchase. DCB content charges are billed as either one-off charges or (more commonly) where the customer is a subscriber, as a subscription charge.

6 At the heart of the case is the distinction between the ways in which an Optus customer is required to verify his or her intention to make a purchase of digital content through the first three pathways, as compared to the DCB service. Broadly, to purchase through the Optus Smart Shop or an app store the customer must have an account with a password and email address, and the Premium SMS service requires a “double opt in”. Those requirements stand in distinction to the requirements under the DCB service where, until June 2016, customers could purchase DCB content simply by clicking a button on an advertisement or a page that appears on a mobile device. From June 2016, Optus instituted a two-step process for customers to purchase DCB content and required third-party websites to display a “Pay with Optus” logo, but many Aggregators did not comply with that process or display the required logo. Relatedly, when a customer went to a PPV type page they were presented with a payment button, and invited to turn to the next page through, for example, a “Next” button. Every time the customer went to the next page on a PPV site they would incur a further charge for the DCB content being purchased.

7 Optus’ admitted conduct falls into four main categories.

8 First, inadequate safeguards – the DCB service had inadequate safeguards against unintentional purchase of digital content, as shown by the fact that a significant number of customers unintentionally purchased and were billed for DCB content without their knowledge or consent. The parties are unable to identify the number of affected customers with precision but Optus admits that there are at least 100,000 and possibly in excess of 240,000 such customers.

9 Second, inadequate notice – Optus did not adequately inform its customers that the DCB service was a default setting on Optus mobile services. Customers were automatically opted in to the DCB service and were not required to take any proactive step in order to be eligible to purchase DCB content. Consequently, if they purchased DCB content on their mobile device, even unintentionally, they would be billed directly by Optus via the DCB service.

10 Third, inadequate claims handling – Optus did not adequately deal with complaints by customers querying the DCB service charges. Optus’ policy was to refer customers who sought to query such charges to the Content Provider or Aggregator and many customers encountered significant difficulties in cancelling a subscription and/or obtaining a refund in respect of the unauthorised charges.

11 Fourth, inadequate response to the problem – as a result of the significant number of complaints received from Optus’ customers in relation to the DCB service, and the escalation to Optus of complaints made to the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) Optus was aware from at least 1 April 2014 that a significant number of customers had, through the DCB service, unintentionally purchased and been billed for DCB content without their knowledge or consent. Despite this awareness Optus did not implement the identity verification safeguards it employed in relation to the other three pathways it offered to access digital content.

12 Optus admits that as a result of complaints received from Optus’ customers, it was aware from at least 1 April 2014 to 15 October 2018 (the relevant period) that the operation of the DCB service had led to a significant number of its customers unintentionally purchasing and being billed for DCB content they had not agreed to acquire (Non-consenting Customers). Optus admits that in these circumstances, by applying charges to those customers’ accounts, it made false and misleading representations in connection with the supply or possible supply of a “financial product” or a “financial service” within the meaning of the ASIC Act to each of the Non-consenting Customers that they had agreed to acquire that DCB content when they had not, in contravention of section 12DB(1)(b) of the ASIC Act.

13 For the reasons I now explain I am satisfied that it is appropriate to make the declaration and orders the parties seek, with one important change. I thank the parties for the high quality of the ASAFA and Joint Submissions, from which I have directly drawn in these reasons.

JURISDICTION

14 The ACCC is the statutory authority responsible for enforcing the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) including the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Schedule 2 of the CCA. However according to the parties’ Joint Submissions, the way the payment arrangements were structured between the Content Providers, Aggregators, Optus and customers involved the supply of a “financial service”. Section 131A of the CCA provides that (apart from exceptions which are not presently relevant) the prohibition on misleading and deceptive conduct in the ACL does not apply to the supply or possible supply of financial services.

15 In broad terms the payment arrangements worked as follows. Once a customer purchased DCB content from a Content Provider, Optus would transmit the customer’s mobile number or equivalent identifying details to the relevant Aggregator. The Aggregator would put the charge on the customer’s Optus account through Optus’ billing platform. For post-paid customers, Optus would then (later) bill the customer for the charge in accordance with its usual billing cycle, and for pre-paid customers Optus would deduct the charge from the customer’s pre-paid credit balance. In respect of post-paid customers, while Optus was waiting for the customer to pay the bill Optus would have already paid the Aggregator on behalf of the customer, and Optus was owed a debt by the customer.

16 It is unnecessary to detail the somewhat convoluted path through the relevant legislative provisions which brought the parties to the conclusion they have reached. Moshinsky J set out the path in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corp Ltd (2018) ATPR 42-593; [2018] FCA 571 (ACCC v Telstra) at [29]-[38] in the context of similar payment arrangements involving Telstra and its mobile customers. His Honour declared that Telstra’s version of the DCB service (called the PDB service), which enabled Telstra mobile service customers to purchase digital content from third party Content Providers or Aggregators and have the charges for that content billed to their Telstra account, was a financial service within the meaning of the ASIC Act.

17 The proceeding was accordingly brought under s 12DB(1)(b) of the ASIC Act, rather than under the ACL. Under s 102 of the ASIC Act, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission has relevantly delegated all of the functions and powers conferred on it under Division 2 of Part 2 of the ASIC Act (other than sections 12GLC and Subdivisions GB and GC of Division 2 of Part 2) to the second applicant, Mr Greiss, Executive General Manager, Enforcement Division of the ACCC, to the extent that those powers and functions may be necessary for or reasonably incidental to the commencement and conduct of any proceedings in relation to matters involving financial products and services provided as part of, or in connection with, the supply or possible supply of telecommunications services. The ACCC brings the proceeding in reliance on those delegated powers.

18 I am satisfied that the Court has jurisdiction to make the declaration and orders sought on the basis submitted by the parties.

THE FACTS

19 The ASAFA is Annexure 1 to these reasons. I will not endeavour to summarise it, but I deal with the salient parts in determining whether it is appropriate to make the declaration and orders sought.

RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

20 The Joint Submissions helpfully set out the relevant principles and I adopt them accordingly.

The relevance of the parties’ agreement

21 The parties jointly seek orders by agreement. The principles relevant to making declarations and orders by consent in civil penalty proceedings were summarised by Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 (Coles Suppliers Case) at [70]–[79]. They include that:

(a) there is a well-recognised public interest in the settlement of cases under the CCA;

(b) the orders proposed must not be contrary to the public interest and at least consistent with it;

(c) the Court must be satisfied that it has the power to make the orders proposed and that they are appropriate;

(d) once satisfied that proposed orders are within power and that they are appropriate, the Court should exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising the proposed terms, particularly where both parties are represented and able to evaluate the desirability of the settlement; and

(e) in deciding whether agreed orders conform with legal principle, the Court is entitled to treat the consent of the respondent as an admission of all facts necessary or appropriate to the granting of the relief sought against it.

22 The public interest in parties resolving civil penalty matters with regulators such as the ACCC was reaffirmed by the High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; [2015] HCA 46 (Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate) where French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ said at [46]:

…[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

23 Their Honours also explained (at [57]) that there is “very considerable scope” for parties in civil proceedings to agree on facts and upon consequences, as well as for them to agree on appropriate remedy and “for the court to be persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy” (emphasis in original). At [58] their Honours said that in connection with civil penalty proceedings:

Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle, and, for the reasons identified in Allied Mills, highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

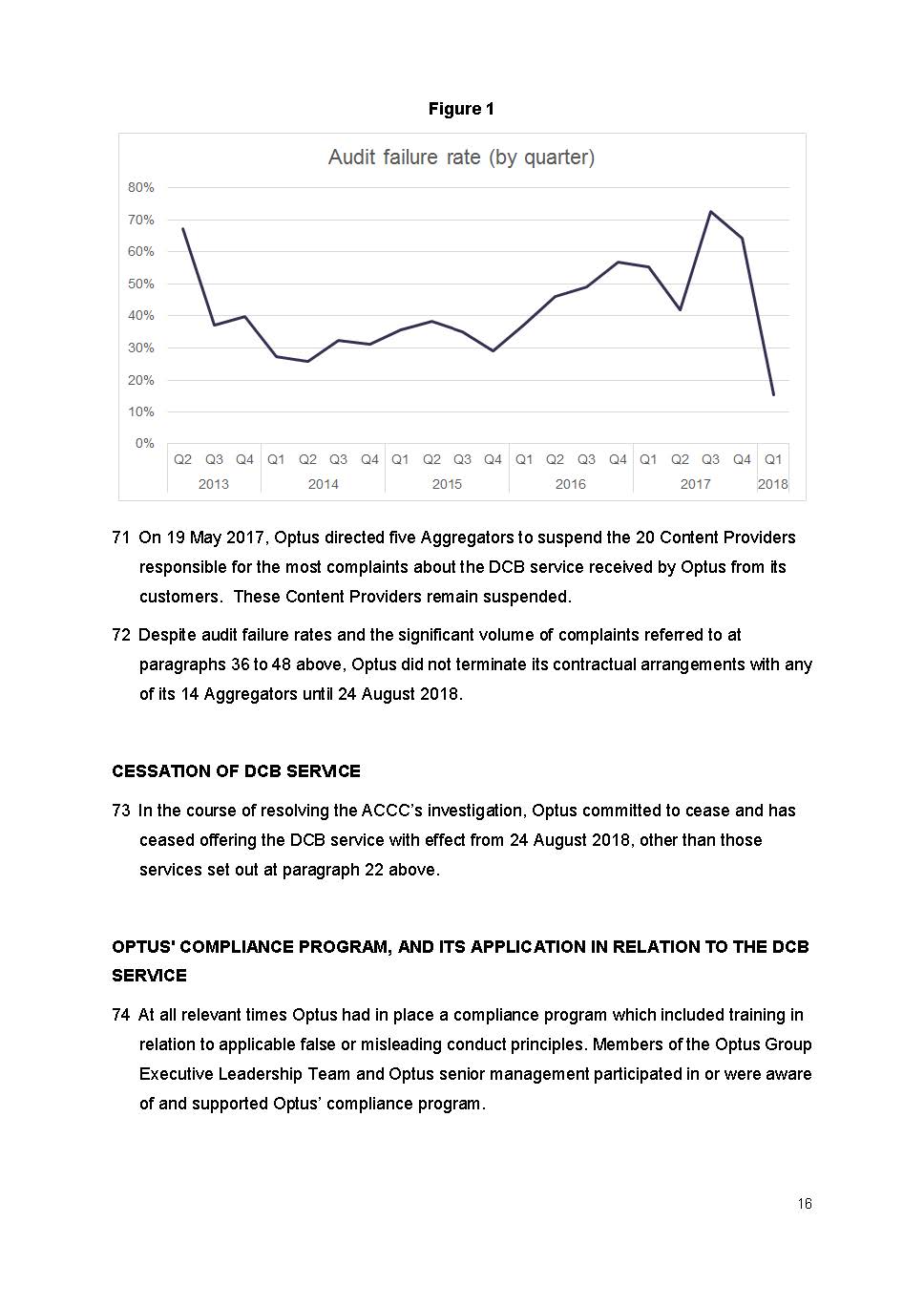

24 In the Coles Suppliers Case Gordon J also noted that where a declaration is sought with the consent of the parties, the Court’s discretion is not displaced, but the Court will not refuse to give effect to terms of settlement by refusing to make orders where they are within the Court’s jurisdiction and are otherwise unobjectionable. Her Honour said that before making declarations, three requirements should be satisfied:

(a) the questions must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor.

I am satisfied that those requirements are met in the present case.

Pecuniary penalties

25 The Joint Submissions also helpfully set out the principles relevant to the imposition of a pecuniary penalty, and I adopt them.

Section 12GBA of the ASIC Act

26 The discretion to be applied in setting a pecuniary penalty must be guided, first, by the applicable statutory provision. Section 12GBA(1) of the ASIC Act provides that the Court may order a person who has contravened (relevantly) s 12DB to pay such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

27 Section 12GBA(2) requires the Court, in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, to have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under Subdivision G to have engaged in any similar conduct.

These considerations are substantially the same as those referred to in s 76(1) of the CCA (formerly the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)) and the authorities dealing with that provision are of assistance in applying s 12GBA of the ASIC Act: see ACCC v Telstra at [21].

The maximum penalty

28 The process to be used in setting a civil penalty for contravention of statutory provisions is similar to that used in criminal sentencing: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540; [2015] FCA 330 (Coles Bread Case) at [6] (Allsop CJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd (2005) ATPR 42-070; [2005] FCA 683 at [68] (Gyles J). The maximum penalty must be given due attention because the legislature has seen fit to legislate for them, they invite comparison between the “worst possible case” and the case before the court at the time, and they provide a form of yardstick: Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357; [2005] HCA 25 (Markarian) at [31].

29 In Markarian Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ held at [27], [31] and [39] that:

(a) assessment of the appropriate penalty is a discretionary judgment based on all relevant factors but careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required;

(b) it will rarely be appropriate for a Court to start with the maximum penalty and proceed by making a proportional deduction from that maximum, and the Court should not adopt a mathematical approach of increments or decrements from a predetermined range, or assign specific numerical or proportionate value to the various relevant factors; and

(c) accessible reasoning is necessary in the interests of all, and, while there may be occasions where some indulgence in an arithmetical process will better serve this end, it does not apply where there are numerous and complex considerations that must be weighed.

30 Their Honours described the appropriate sentencing process as one of “instinctive synthesis”. McHugh J described this process (at [51]) as one in which:

… the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case. Only at the end of the process does the judge determine the sentence.

31 The High Court in R v Kilic (2016) 259 CLR 256; [2016] HCA 48 gave further consideration to the expression “worst possible case” and observed that use of this legal shorthand is liable to mislead lay persons as to its meaning. The Court said that in cases where it is relevant to do so, it is preferable to state in full whether the offence is or is not so grave as to warrant the maximum prescribed penalty: at [20].

32 It is uncontroversial that the process under s 12GBA of the ASIC Act is the same as under civil penalty regimes in other legislation such as the ACL and in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). The methodology is not cast in stone and it is not an exact science: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 269 ALR 1; [2010] FCAFC 39 (CFMEU v Cahill) at [47] (Middleton and Gordon JJ); NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (NW Frozen Foods) at 290-291.

33 Section 12GBA(3) provides that the maximum penalty for a body corporate for each act or omission that relates to s 12DB is 10,000 penalty units. Over the relevant period, the value of a penalty unit has increased such that it has been:

(a) between 28 December 2012 and 30 July 2015, $170;

(b) between 31 July 2015 and 30 June 2017, $180; and

(c) since 1 July 2017 and presently, $210: Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), s 4AA.

In the circumstances of the present case the maximum penalty for each act or omission to which s 12DB applied during the relevant period therefore ranged from $1.7 million to $2.1 million.

34 Notwithstanding the parties’ agreement it is for the Court to determine whether the contraventions occurred and the quantum of any pecuniary penalty that should be ordered.

Deterrence

35 The principal object of a pecuniary penalty is deterrence, directed both to discouraging repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and discouraging others who might be tempted to engage in similar contraventions (general deterrence). In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd (1991) ATPR 41-076 (TPC v CSR), cited with approval in Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate at [55], French J said at 52,152:

The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

36 In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249; [2012] FCAFC 20 (Singtel Optus) at [68] (cited with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640; [2013] HCA 54 at [64] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ)) the Full Court said:

The Court must fashion a penalty which makes it clear to [the contravener], and to the market, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of the Act cannot be regarded as [an] acceptable cost of doing business.

Even so, in seeking to deter, a pecuniary penalty should not be set so high as to be oppressive: NW Frozen Foods at 293; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum (No 2) (2005) 215 ALR 281; [2005] FCA 254 at [9] (Merkel J).

Other relevant penalty factors

37 In addition to the three factors to which the Court must have regard in fixing an appropriate penalty, a number of other factors or considerations have been identified as relevant in the case law, although these are also not intended to be exhaustive. These factors, some of which overlap with the mandatory considerations in s 12GBA of the ASIC Act, can be traced back to the decision of French J in TPC v CSR at 52,152-52,153 and NW Frozen Foods at 292-4. In summary, they are as follows:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(b) the size of the contravening company;

(c) the deliberateness of the contravention and period over which it extended;

(d) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at a lower level;

(e) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the relevant legislation, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(f) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for enforcement of the relevant legislation;

(g) the financial position of the contravener;

(h) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert; and

(i) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past.

See also J McPhee & Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365 at [150] (Black CJ, Goldberg and Lee JJ). The significance of each factor to the appropriate penalty depends on the facts of the case.

The course of conduct principle

38 As the parties submitted, the “course of conduct principle” is also relevant to the assessment of a pecuniary penalty. This principle recognises that where there is sufficient interrelationship in the legal and factual elements of the acts or omissions that constitute a contravention, the Court may in its discretion penalise the acts or omissions as a single course of conduct. The principle was explained in CFMEU v Cahill at [39] and [41] as follows:

The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality.

…

In other words, where two offences arise as a result of the same or related conduct that is not a disentitling factor to the application of the single course of conduct principle but a reason why a Court may have regard to that principle, as one of the applicable sentencing principles, to guide it in the exercise of the sentencing discretion. It is a tool of analysis which a Court is not compelled to utilise.

(Citations omitted, emphasis in original.)

39 Where the large number of contraventions means there can be no meaningful overall maximum penalty, the maximum penalty should not be applied mechanically and should instead be treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one. In such cases the appropriate penalty range may be best assessed by reference to other factors: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25; [2016] FCAFC 181 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [156]-[157] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ). Similarly, in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68; [2017] FCAFC 113 at [143]-[146] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ), the Full Court observed that in cases involving agreement between the parties as to very large numbers of contraventions, it is not helpful to seek to make a finding as to the precise number of contraventions or to calculate the maximum aggregate penalty. The Full Court also noted that, in cases of agreement between the parties as to a single proposed penalty for multiple contraventions, the Court may approve that course where it considers it appropriate to do so.

The parity principle

40 Assessments of penalty in analogous cases may also provide guidance to the Court in assessing an appropriate penalty, by assisting equal treatment in similar circumstances and thereby meeting the principle of equal justice. Penalties set in other cases can only be a guide, however, because the circumstances in different cases are rarely precisely the same as the case then before the Court: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SMS Global Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 855 at [80] and the cases there cited.

The totality principle

41 The totality principle is also relevant. It requires the Court to consider the entirety of the underlying contravening conduct to determine whether the total or aggregate penalty is just and appropriate: Mill v The Queen (1988) 166 CLR 59 at 63.

DETERMINATION

42 I now turn to apply the relevant principles to the facts and circumstances of the present case.

The course of conduct principle

43 As the parties accepted, in the present case there is a difficulty in identifying the number of relevant “acts or omissions” and hence the maximum applicable penalty. Arguably, a contravention of s 12DB occurred each time Optus made the relevant false or misleading representation to an affected customer. Optus admits that there were at least 100,000 occasions on which the relevant representation was made, and on that basis the notional maximum penalty could exceed hundreds of millions of dollars. Alternatively, it might be argued that there was just one course of conduct being Optus’ implementation and operation of its DCB, or that there were several types of conduct based on the different ways in which Optus offered and charged for its DCB service, including whether Non-consenting Customers were pre-paid or post-paid customers; the different processes in place before and after 6 June 2016; the different process in place after 31 January 2018; the different way PPV charges were incurred; and the different levels of knowledge of senior management at various times during the relevant period.

44 I am satisfied that in the circumstances of the present case it is appropriate not to make a finding about the precise number of contraventions or whether there is a single course or multiple courses of conduct. Instead, I shall treat the maximum penalty as one factor, albeit an important one, in assessing an appropriate penalty. It is appropriate to decide the appropriate penalty assisted by understanding the extent to which there was a course or courses of conduct leading to potentially a huge number of contraventions, and to undertake the ‘instinctive synthesis’ by reference to a recognition of the multiplicity of breaches, a broad view of the course or courses of conduct, and an assessment of the overall extent and seriousness of offending, together with all other relevant considerations, but in particular the need for specific and general deterrence: see Coles Bread Case at [17]-[18], [84]-[85] (Allsop CJ ).

The relevant penalty factors

The nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the circumstances in which it took place

45 As set out in the ASAFA, consistent with Optus’ arrangements with Aggregators, the process for Optus customers to subscribe to or purchase DCB content and the manner in which the DCB service was intended by Optus to operate was as follows:

(a) an Optus customer, while using other applications or websites on their device, encounters an advertisement for DCB content;

(b) if the customer clicks on the advertisement, the customer is taken to a different web-based address associated with a Content Provider (third party website);

(c) on the third party website the customer is presented with a “buy now” or “subscribe” (or similar) button (purchase trigger), in respect of which:

(i) prior to 6 June 2016 purchasing DCB content required a customer to make a single click on a purchase trigger (although in some limited cases a double click process did exist in respect of certain DCB content);

(ii) since 6 June 2016, purchasing DCB content required two steps: a customer first clicks a “subscribe” or similar button, and on a second screen, the customer then clicks a “confirm”, “continue”, “accept” or similar button to confirm their purchase (double-click process);

(iii) since June 2016, third party websites displayed a “Pay with Optus” logo to the customer; and

(iv) since 31 January 2018, new DCB subscriptions are no longer available and customers can only purchase DCB content on a one off basis (although existing subscriptions were not affected by this change);

(d) if the customer is connected to the Optus network and the third party website is operated by or associated with an Aggregator participating in the DCB service then, when the customer clicks a purchase trigger (before 6 June 2016) or completes a double-click process (after 6 June 2016), Optus transmits the customer’s mobile device number or unique identifier via encrypted format to the Aggregator; and

(e) the Aggregator then puts the charge on the customer’s Optus account through Optus’ billing platform.

46 Content could also be billed for on a PPV basis. The PPV model, consistent with Optus’ arrangements with Aggregators, was intended by Optus to operate in the following way:

(a) an Optus customer encounters a third party website with the same features and in the same way as described above;

(b) the customer encounters subsequent PPV pages, on which the customer is presented with a payment button that includes the term “Next” or “Next Page” and the charge to be incurred (PPV payment trigger); and

(c) the customer incurs additional charges with each single click of a PPV payment trigger.

47 Because the process did not require customer identity verification or other confirmation of purchase of the type required under the other pathways for access to digital content, the operation of the DCB service led to a great number of Optus customers unintentionally purchasing and being billed for DCB content without their knowledge or consent. Optus admits that there are at least 100,000 and possibly in excess of 240,000 such customers.

48 Optus admits it was aware that customers were at risk of unintentional purchases and that customers were being charged for services they had not intended to acquire. Paraphrasing the admissions in the ASAFA, Optus admits that:

(a) the DCB service had inadequate safeguards against unintentional purchase of digital content;

(b) it did not adequately inform its customers that the DCB service was a default setting on Optus mobile services such that customers were automatically opted in to the DCB service and would be billed directly by Optus even if they unintentionally purchased DCB content without their knowledge or consent;

(c) it did not adequately deal with complaints by customers querying the DCB service charges incurred; and

(d) its response to the problem was inadequate.

49 Optus was made aware of the problem with its DCB service over a long period of time through complaints by a large number of Non-consenting Customers. Between about 1 May 2012 and 31 March 2018 Optus had received:

(a) approximately 616,000 calls (on average 280 per day) from customers in relation to its DCB service; and

(b) approximately 2,569 complaints escalated to Optus from the TIO relating to DCB and Premium SMS services, the majority of which related to DCB services.

50 By 31 March 2014, because of the volume of complaints received and refunds provided, Optus was aware that a significant number of its customers had unintentionally purchased and been billed for DCB content without their knowledge or consent. From at least that time Optus was aware that a significant number of its customers:

(a) had little or no awareness of subscribing to third party content;

(b) were not aware of third party content charges appearing on their accounts;

(c) denied purchasing the third party content which was incurring charges;

(d) were unaware that third party content purchases could be effected without the need to add further personal information;

(e) did not know how to opt-out of the DCB service; and

(f) had difficulty obtaining refunds from third parties due to poor complaints handling practices.

51 In addition Optus was aware that many of its customers may not be aware of charges for content billed through the DCB service appearing on their accounts. This was because:

(a) pre-paid customers do not automatically receive a monthly bill;

(b) post-paid customers paying by direct debit have charges automatically deducted from their nominated accounts;

(c) customers’ accounts can print to numerous pages; and

(d) even those customers who did review their accounts will have often found it difficult to determine the identity of the third party on their bill.

52 Further, in June 2015 the TIO informed Optus that the number of complaints it had received indicated that there may be a systemic issue relating to Optus’ handling of consumer complaints about disputed third party charges, and identified a number of issues experienced by Optus customers. In July 2016 the TIO provided Optus with an outline of a number of best practice features that it should consider implementing in order to address the issues that were being experienced by its customers. Optus, however, only implemented some of them.

53 These shortcomings were compounded by other aspects of Optus’ approach to the DCB service, including its policy of directing all customer complaints about the DCB service in the first instance to the Aggregators or Content Providers, despite being aware that customers had difficulty contacting third party providers via the contact number Optus supplied, or that third party providers refused to assist with or refund disputed DCB content charges.

54 Optus was also aware through an audit program it instituted that there was significant and sustained non-compliance by Aggregators with Optus’ standards; an average of 40% of audits identified infringements of standards in the period between April 2013 and March 2018. A substantial number of the infringements concerned the failure of Aggregators and Content Providers to offer the double-click process at all or to do so effectively.

55 Notwithstanding this, Optus did not terminate any of its contractual arrangements with Aggregators until May 2017 when it directed five Aggregators to suspend 20 different Content Providers. Optus did not terminate contractual arrangements with any of its 14 Aggregators until 24 August 2018.

56 Optus’ misconduct is serious in nature. It knew over a long period of time that its DCB service had seriously inadequate safeguards, and that as a result a great number of its customers had unintentionally purchased DCB content and been billed without their knowledge or consent. Over a long period of time Optus failed to appropriately address complaints and the inadequacy of the safeguards in its DCB service. This shows an unacceptable attitude by Optus to its obligations to consumers, and indicates that a substantial pecuniary penalty is appropriate.

The amount of loss or harm caused

57 In the period from approximately May 2012 to 31 March 2018 Optus customers paid approximately $195 million (including GST) in DCB charges, and from this Optus generated approximately $65.8 million in net revenue. From May 2012 to 31 March 2018 Optus applied DCB charges to an average of about 1 million customer mobile accounts each financial year.

58 While Optus cannot identify with precision the proportion of the approximately $195 million in DCB charges that were incurred by Non-consenting Customers, it accepts that the number of customers impacted by its conduct is at least 100,000 and possibly in excess of 240,000. It is plain that the level of harm caused to customers was significant, which again indicates that a substantial pecuniary penalty is appropriate.

59 Even so, the level of harm suffered by customers has been reduced through the provision of customer refunds. Optus estimates that, to date, Optus, Aggregators with contractual arrangements with Optus, and Content Providers have provided approximately $21 million in refunds to more than 240,000 customers. Of those refunds Optus itself has paid out approximately $8 million to customers who complained about DCB services (although this figure may also include payments made to customers in relation to non-DCB services).

60 The level of harm suffered by Optus customers will be further mitigated by a customer refund program to which Optus has committed. As set out in the ASAFA, Optus has committed to a customer refund program under which it shall identify, communicate with, and offer refunds to affected customers as follows:

(a) by no later than 12 weeks from the date of the making of the final orders in these proceedings (Orders), Optus will identify customers in the following groups:

(i) customers Optus identifies as having complained directly to Optus in relation to DCB content charges applied by Optus prior to 24 August 2018;

(ii) customers Optus identifies as having incurred charges for DCB content between 6 June 2016 and 24 August 2018 in relation to DCB content charges where Optus has identified that the Aggregator or Content Provider did not have a ‘double-click’ mechanism (as referred to in paragraph 27c.ii of the ASAFA); and

(iii) customers Optus identifies as having made a complaint to the TIO prior to the date of commencement of these proceedings in relation to DCB content charges; and

(b) communicate with and offer to refund customers referred to at (a)(i), (ii) and (iii) the DCB content charges applied to those customers’ accounts (which communication and offer will only be made to customers who Optus has contact details for, identifies as having not already received refunds for such charges from Optus or some other party, and will only need to be made once if a customer falls under more than one of the groups referred to in paragraph (a)(i), (ii) and (iii) above); and

(c) for a period of 12 months from the date of the making of the Orders, Optus will deal directly with future complaints (including in relation to past periods) in relation to DCB content charges and seek to resolve those complaints in good faith, including providing refunds for DCB content charges where it is apparent that the customer had unintentionally purchased and been billed for DCB content without their knowledge or consent and so did not agree to acquire the content; and

(d) inform the ACCC in writing, within 4 months of the making of the Orders, and quarterly thereafter for one year, of:

(i) the steps taken to identify the customers in accordance with paragraph (a) above;

(ii) for each of the categories of customers specified in paragraph (a) above—the number of customers identified;

(iii) in relation to paragraph (b) above—the number of customers contacted, the number of customers refunded, the number of customers (if any) refused refunds and the amount of money that has been refunded; and

(iv) for each of the customers who complain to Optus under paragraph (c) above—the number of such customers, the number of customers refunded, the number of customers (if any) refused refunds and the amount of money that has been refunded.

61 It seems likely that a great many Non-consenting Customers will be identified and compensated through the customer refund program, but it is also likely to depend upon how conscientiously Optus undertakes the program. In oral submissions Mr Armstrong QC, senior counsel for the applicants, said that the ACCC expects that Optus will conscientiously implement the customer refund program and expects that any concerns that the ACCC may later have in relation to its implementation will be properly addressed by Optus. Mr Armstrong QC accepted, however, that if Optus failed to properly implement the program, the orders they jointly proposed meant that the ACCC would be unable to bring the proceeding back before the Court to deal with any such failure or to independently prosecute any such failure.

62 In my view that position is unsatisfactory. If the consumer refund program is to be treated as mitigating the penalty, as the parties seek, I consider the ACCC should have liberty to restore the proceeding if Optus fails to meet its commitments in relation to the program. In the finish, the parties agreed that this was appropriate. With this safeguard in place, although the amount of loss and harm suffered by customers remains substantial, the consumer refund program should significantly mitigate that harm and this reduces the quantum of the appropriate penalty.

The size of the contravening entity and its financial position

63 Optus is part of the Optus Group which is a substantial enterprise. It is Australia’s second largest supplier of mobile phone services, having an approximately 28% share of the retail market for mobile services, and over 10 million mobile subscribers. During the financial year 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 the Group generated $3.953 billion in mobile service revenue, and achieved earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of about $2.774 billion.

Whether the conduct was systematic or deliberate

64 As the parties jointly submitted, Optus designed the DCB service and made the decisions to implement it in the ways set out in the ASAFA. Amongst other things, it did not require customer identity or purchase verification in relation to a DCB content purchase before the charges for purchasing such content could be billed to a customer’s Optus account. It received a huge number of complaints about the DCB service directly through its own call centre and indirectly through the TIO.

65 Optus’ conduct towards its customers was in this sense deliberate. It was aware from complaints that its customers might be billed for a service they had not intended or agreed to acquire and did not take sufficient steps to prevent this from happening. While Optus took some steps to address the risks of customers being billed for DCB content that they had not agreed to acquire, as I have said these were ineffective in preventing a significant number of customers from being charged for DCB content that they had not agreed to acquire.

66 Optus’ conduct and its risks, the remediation steps it took and the inadequacy of those steps was known within Optus, including at senior levels of management. In my view it is appropriate to describe Optus’ conduct as systematic and deliberate. This too indicates a need for a substantial penalty.

Involvement of senior management

67 As I have said, Optus’ conduct and its attendant risks, as well as the remediation steps taken and the inadequacy of those steps, were known within Optus including at senior levels of management. Relevant senior managers should have but did not adopt further or more effective means to prevent customers being charged for DCB content they had unintentionally acquired. I am satisfied that Optus’ unsatisfactory approach to its obligations to customers was sanctioned at senior levels of management.

Corporate culture

68 During the relevant period Optus took a number of steps to address concerns with the DCB service, including the following:

(a) from June 2016, references to third-party content were included in a guide provided to new Optus post-paid customers but not to new pre-paid customers;

(b) on 6 June 2016, Optus notified Aggregators that they were required to comply with a “double-click” process, but subsequent audits demonstrated that a significant number of Aggregators did not do so;

(c) before 6 June 2016, Optus recommended that Aggregators display a “Pay with Optus” logo on the third party website from which customers purchase DCB content, and notified them that they must do so after this date. However, the subsequent audits demonstrated that a significant number of Aggregators failed to adhere to this requirement;

(d) between 31 January 2018 and 24 August 2018, new DCB content subscriptions were no longer available and customers could only purchase DCB content on a one-off basis. During this period, in order to acquire DCB content as a one-off purchase, customers were required to follow the double-click process (as referred to in paragraph 27c.ii of the ASAFA);

(e) from at least July 2017, Optus required Aggregators to provide a summary of the proposed sales, marketing, information or advertising material created or published by Aggregators which promotes the purchase of DCB content, in order that Optus could review the Aggregators’ compliance with its requirements. Optus did not, however, assess whether each subscription process complied with all of Optus’ requirements;

(f) from about April 2013, Optus engaged Aegis Mobile Australia Pty Ltd (Aegis), an external third party, to audit and enforce compliance by Aggregators with Optus’ requirements. However, Aegis did not monitor or audit whether each Optus customer had actually clicked on a purchase trigger before Optus provided a customer’s mobile device number or unique identifier to Aggregators or Content Providers. Rather, it conducted monthly testing and quarterly reporting, and from time to time issued infringement notices to certain Aggregators or Content Providers which it had audited;

(g) between April 2013 and March 2018 Aegis conducted 9,460 audits and identified 3,818 infringements of the audit standards (about 40% of all DCB audits). The percentage of audits which failed an element of the relevant audit standards ranged between about 25 and 70% in any given quarter and reached a high of 73% in late 2017; and

(h) it was not until 19 May 2017 that Optus directed five Aggregators to suspend 20 Content Providers, and it did not terminate the contractual arrangements with its 14 Aggregators until 24 August 2018.

69 In my view the steps Optus took were inadequate. Optus did not do enough to ensure that customers were not misled, and continued to the offer the DCB service notwithstanding that the serious problems with the service remained unresolved. Its approach points to serious deficiencies in Optus’ corporate culture which heightens the need for a substantial penalty, in aid of specific deterrence.

Cooperation

70 An important factor in mitigation is the fact Optus has afforded the ACCC a very high level of cooperation in these proceedings. It provided information and documents to the ACCC voluntarily during the ACCC’s investigation, admitted liability and agreed to the jointly proposed release before the commencement of the proceeding, thereby avoiding the need for the ACCC to litigate what may otherwise have been a lengthy and expensive case, and this entitles Optus to a discount on the penalty to be imposed.

Termination of the DCB service

71 Optus ceased offering the DCB service from 24 August 2018 (other than a limited number of services for one-off content for TV shows, magazines and mobile gaming, which require express customer agreement to each purchase being charged to the customer’s Optus account). Optus’ (belated) recognition of the problems associated with the DCB service, and its decision to largely terminate the service and offer refunds operates in mitigation of the appropriate penalty.

Similar conduct in the past

72 As set out in the Joint Submissions, while entities in the Optus Group have not previously been found to have contravened the ASIC Act or the ACL by engaging in conduct of this kind, they have contravened the ACL on several previous occasions:

(a) in May 2018, Optus Internet Pty Ltd (Optus Internet) was found to have breached sections 18 and 29(1)(m) and (l) of the ACL by making representations to particular customers about its rights to cancel the customer’s service, and about the need to acquire services using the National Broadband Network from Optus: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus Internet Pty Limited [2018] FCA 777;

(b) in February 2014, Singtel Optus Pty Ltd was found to have breached sections 18, 29(1)(b) and (g) of the ACL in connection with the advertising of the coverage of its mobile network: Telstra Corporation Limited v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2014] VSC 35;

(c) in June 2012, Singtel Optus Pty Ltd was ordered to pay a penalty of $3.61 million in respect of contraventions of section 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) concerning the advertising of broadband data service plans to consumers: Singtel Optus; and

(d) in October 2010, Singtel Optus Pty Ltd was found to have engaged in a misleading and deceptive fashion in connection with an advertising campaign promoting several of its internet broadband plans: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1177.

73 Further, several ACCC concerns with conduct by entities in the Optus Group have been resolved through undertakings pursuant to s 87B of the CCA. For example:

(a) on 11 December 2017 Optus Internet provided an undertaking in relation to its representations about speeds available to consumers on its broadband plans supplied over the NBN, which were likely to contravene ss 18 and 29(1)(b) and (g) of the ACL;

(b) on 1 June 2017 Optus provided an undertaking in relation to alleged misrepresentations about the amount and period of validity of data, calls and texts provided with certain prepaid products and services; which conduct it admitted was likely to have contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(g) of the ACL;

(c) on 16 December 2015 Optus Internet provided an undertaking for allegedly making misrepresentations about the data transfer speeds offered on its broadband cable service and particular plans; and

(d) on 6 January 2011 Optus provided an undertaking following an investigation into alleged misrepresentations about consumers’ rights and remedies for faulty mobile phones. As part of the undertakings, Optus undertook not to make any misleading representations to consumers regarding their statutory rights.

74 This history, and the conduct which is the subject of the present case, shows that the Optus Group has an insufficiently rigorous approach to compliance with its obligations under consumer protection legislation. This too points towards a substantial penalty.

The appropriate penalty

75 The parties jointly submitted that a pecuniary penalty of $10 million appropriate.

76 Most of the penalty factors to which I have referred point towards imposition of a substantial penalty together with the fundamental requirement for specific and general deterrence. The need for specific deterrence is heightened in the present case because of the frequency with which entities in the Optus Group have contravened the ACL and agreed to provide s 87B undertakings in response to ACCC allegations of misconduct over the last eight years. Against this must be balanced the mitigating factors which I have identified above, including Optus’ commitment to a refund program, cooperation with the ACCC and to a lesser extent its termination of the DCB service.

77 I consider a penalty of $10 million, coupled with an obligation to provide further refunds to affected customers under the customer refund program, is sufficient to achieve specific deterrence. Optus made $65.8 million in net revenue from DCB charges over the almost 8 years from May 2012 to 31 March 2018, which is an average of about $8.22 million per annum. While accepting that the net revenue is unlikely to be the same each year, a penalty of $10 million roughly cancels out the net revenue Optus earned in the last year of its operation of the DCB service.

78 A penalty of $10 million is well short of the $65.8 million in net revenue which Optus made from DCB charges, but it must be kept in mind that not all the net revenue Optus made from DCB charges in the relevant period was made from Non-responding Customers. A great many Optus customers are likely to have purchased DCB content in the full knowledge that they were incurring DCB charges.

79 It is important to my decision that, in addition to the $8 million refunds it has already given, Optus has committed to implementing the customer refund program in accordance with paragraph 75 of the ASAFA and as described in the Joint Submissions. I have fixed the penalty in the amount I have on the basis that the customer refund program will be properly implemented by Optus. In the absence of that program I would have been inclined to impose a higher penalty or to make other consumer redress orders.

80 The orders I have made provide the ACCC with liberty to return to the Court should it have concerns about Optus’ implementation of the customer refund program, and to have those concerns addressed by the Court. This does not mean that the Court would revisit the penalty imposed. Rather, subject to hearing from the parties, it could involve the Court taking remedial steps to ensure that the program is implemented in accordance with the ASAFA and with the parties’ intent as communicated to the Court.

81 It is also significant that Optus has effectively been forced to terminate the DCB service from 1 August 2018. As a result it has suffered the loss of a valuable revenue stream, which should deter senior management from again engaging in similar conduct.

82 A penalty of $10 million is also likely to deter others from risking contraventions of the ASIC Act. On any view, a penalty of $10 million is substantial. In my view, notwithstanding the size of the main players in the mobile telephony market, it is unlikely that a penalty of $10 million will be seen as acceptable cost of doing business, particularly when it is coupled with an obligation to make refunds to all affected customers. For smaller corporations involved in the relevant market such a penalty should prove a considerable disincentive against contravening conduct.

83 Having regard to the parity principle, I note that the Court in ACCC v Telstra imposed the same pecuniary penalty for essentially similar conduct, from which Telstra generated net revenue in roughly the same order as Optus. This is not as important as the other considerations but it confirms my view that a $10 million penalty is appropriate. Finally, on consideration of the totality of the contraventions that are the subject of admissions, a pecuniary penalty of $10 million also appears appropriate and does not exceed what is proper for the entirety of the underlying contravening conduct.

84 In all the circumstances I am satisfied it is appropriate to make the attached declaration and orders, including orders for Optus to pay the ACCC’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding.

I certify that the preceding eighty-four (84) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Murphy. |

Associate:

Annexure 1