FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97

Table of Corrections | |

“Copyright Act 1958 (Cth)” be amended to read “Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)” in the Catchwords and Legislation fields and paragraph [5] |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 11 February 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for case management hearing not before 10:15am on 8 March 2019.

2. The parties confer and endeavour to agree as to the appropriate form of orders to be made reflecting the conclusions expressed in these reasons (including as to costs) and providing a timetable for the necessary steps required to determine the outstanding issues in the proceedings. Draft orders (marked up to show any areas of disagreement) are to be provided to the Associate of Justice Burley no later than two (2) working days before the case management hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BURLEY J:

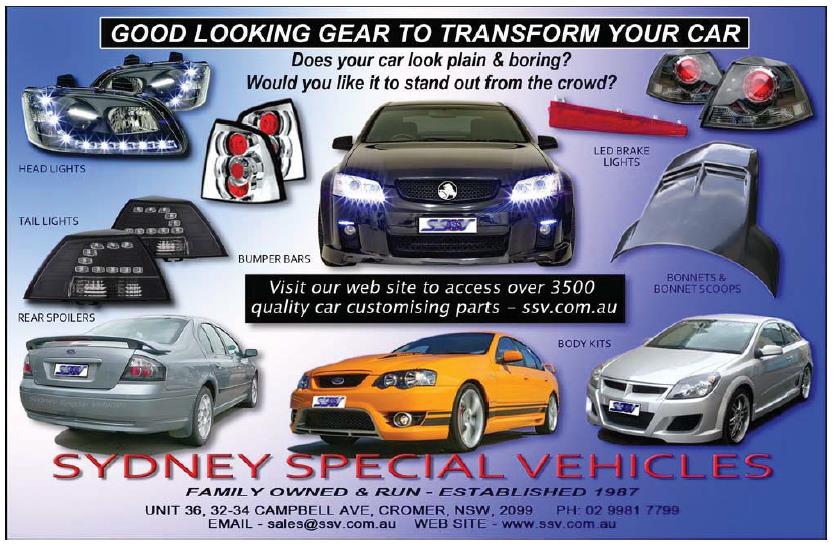

1 Some car enthusiasts, particularly young men, like to upgrade, enhance or “up-spec” the appearance of their standard vehicles to make them look different and, in their view, better. Some buy lower specification Holden Commodores and upgrade them with parts designed for use on the top level Holden Special Vehicle (HSV) and certain sports models of the VE Commodores so that they appear more like these more expensive versions. Owners of genuine HSV or VE Commodores apparently object to such mutton dressed as lamb, and Holden implements controls over the sale of its HSV parts in part to try and discourage such practices.

2 In 2013, Holden learnt that someone was importing replica body parts for HSV and VE parts and selling them without any controls. It sent aggressive letters of demand to numerous spare parts suppliers that it perceived had offered these parts for sale. Subsequently, it identified the source of the replicas and commenced these proceedings against various entities that trade under the name “SSS Auto Parts”, alleging that the replicas infringe some of its designs registered under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth).

3 The respondents respond by accepting that the impugned parts fall within s 71 of the Designs Act, but contend that the terms of s 72, which provides that certain repairs do not infringe registered designs, provide a complete answer to the claim. As a result, the dispute on the claim concerns the application of this section and, in particular, whether the applicant has discharged the burden placed on it to prove that the respondents knew or ought reasonably to have known that the use of the impugned parts was not for the purpose of repair of a complex product (repair defence).

4 The dispute also involves a cross-claim. Aggrieved by the tone and aggression of the letters of demand sent to its customers, the cross-claimants advance a cross-claim for unjustified threats. The key to the success or failure of that claim also, in large part, turns on the operation of s 72 of the Designs Act and in particular whether before sending any such letters the applicant ought to have been in a position to establish that the recipients of the letters did not offer to sell the impugned parts for the purpose of repair.

5 Both parties were represented by able and experienced legal advisors who did their best to limit the issues. However, the operation of the repair defence has not been tested by the Court to date, and its terms open up rich opportunities for dispute. The applicants have advanced a very broad infringement case which alleges infringing conduct by three separate companies, by reason of the separate acts of importing, offering for sale, keeping and selling the impugned parts. In relation to selling, the applicants provided particulars of over 1,300 transactions. They commenced the hearing contending that the Court should make findings for each of these transactions. Through the good sense and co-operation of the parties, that eye watering prospect was reduced to a more manageable 26 representative sample transactions, but even so the task was extensive. Regrettably, it has led to a judgment on the claim that is longer than it might have been had only a handful of transactions been selected. In similar fashion, the cross-claim was advanced on the basis of allegations of unjustified threats under the Designs Act, unjustified threats under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) and ss 18 and 29(1)(m) of the Australian Consumer Law as contained in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL) for 10 separate demands. Again, addressing the extensively detailed case advanced for each of these demands has warranted fairly lengthy reasons.

1.2 The parties and relief sought

6 GM Holden Ltd sells and, until recently, made Holden Commodore vehicles in Australia. At the top of the range, are cars sold under the HSV brand. These are vehicles modified from a production Commodore platform (called a “donor vehicle”) by Premoso Pty Ltd, under licence from GM, by upgrading the engine and interior workings of the vehicle and, most relevantly for present purposes, altering the exterior using, amongst others, differently shaped bumper bars, lights, bonnets and grilles. Many of these parts are the subject of designs registered under the Designs Act and Designs Act 1906 (Cth) by GM Global Technical Operations LLC (GMGTO). Initially, relief was sought by GM, Premoso and GMGTO (collectively GMH), but by amendment made during the trial it is now only GMGTO that does so. It seeks, broadly, a declaration that the respondents have infringed its designs in breach of s 71 of the Designs Act, injunctions restraining the importation, offer for sale, sale or keeping of the impugned products or any product embodying the designs, pecuniary remedies and delivery up of the impugned products. In these reasons, where I refer to submissions, pleadings or contentions advanced by GMH, I do so because at the time the matters advanced were put by GMH collectively. In doing so, I do not intend to suggest that a party other than GMGTO is an applicant in the proceeding.

7 The claim is brought against S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd (SSS Melbourne), S.S.S. Auto Parts (Sydney) Pty Ltd (SSS Sydney) and S.S.S. Auto Parts (QLD) Pty Ltd (SSS Queensland) (collectively SSS or the SSS parties). SSS is an importer and wholesale distributor of aftermarket parts, original manufacturer parts and parallel imported automotive parts.

8 GMH initially also sued a further SSS company, SSS Auto Parts Adelaide (SSS Adelaide), and Mr Lim-S Ung, the sole shareholder, director and secretary of the SSS parties, but by amendment made during the hearing, GMH abandoned its claims against each.

9 The cross-claimants are the SSS parties and SSS Adelaide (SSS cross-claimants). The cross-respondents are GM, GMGTO and Premoso. The SSS cross-claimants seek, broadly; (a) declarations that threats made by GMGTO to SSS and to identified spare parts suppliers are unjustified within the meaning of s 77 of the Designs Act and injunctions restraining further conduct; (b) declaration that threats made to a particular spare parts supplier are unjustified within the meaning of s 202 of the Copyright Act and injunctions restraining further conduct; (c) declarations that the conduct by GMH towards each of the spare parts suppliers contravenes ss 18 and 29(1)(m) of the ACL and injunctions restraining further such conduct; (d) corrective advertising; (e) further orders in the form of a declaration that all undertakings or assurances provided by the parts suppliers in response to the GMH demands are “null and void” and that all information that GMH obtained from the parts suppliers be returned or destroyed; and (f) pecuniary relief or, alternatively, compensation pursuant to s 237 of the ACL.

10 By order dated 22 August 2017, issues of liability were to be heard separately and before issues concerning quantum of any relief.

1.3.1 Sections 71 and 72 of the Designs Act

11 Subsection 71(1) of the Designs Act provides:

(1) A person infringes a registered design if, during the term of registration of the design, and without the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design, the person:

(a) makes or offers to make a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; or

(b) imports such a product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(c) sells, hires or otherwise disposes of, or offers to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, such a product; or

(d) uses such a product in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) keeps such a product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d).

12 Subsection 71(2) provides that “despite subsection (1)” a person does not infringe a registered design if the person imports a product embodying a design that is identical to or substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design with the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design.

13 Subsection 71(3) provides for the factors to be taken into account in determining whether an allegedly infringing design is relevantly similar in overall impression to a registered design.

14 Subsection 71(4) provides that infringement proceedings must be started within 6 years from the day on which the alleged infringement occurred.

15 Section 72 of the Designs Act relevantly provides as follows:

72 Certain repairs do not infringe registered design

(1) Despite subsection 71(1), a person does not infringe a registered design if:

(a) the person uses, or authorises another person to use, a product:

(i) in relation to which the design is registered; and

(ii) which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the product is a component part of a complex product; and

(c) the use or authorisation is for the purpose of the repair of the complex product so as to restore its overall appearance in whole or part.

(2) If:

(a) a person uses or authorises another person to use a product:

(i) in relation to which a design is registered; and

(ii) which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the person asserts in infringement proceedings that, because of the operation of subsection (1), the use or authorisation did not infringe the registered design;

the registered owner of the design bears the burden of proving that the person knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the use or authorisation was not for the purpose mentioned in paragraph (1)(c).

(3) For the purposes of subsection (1):

(a) a repair is taken to be so as to restore the overall appearance of a complex product in whole if the overall appearance of the complex product immediately after the repair is not materially different from its original overall appearance; and

(b) a repair is taken to be so as to restore the overall appearance of a complex product in part if any material difference between:

(i) the original overall appearance of the complex product; and

(ii) the overall appearance of the complex product immediately after the repair;

is solely attributable to the fact that only part of the complex product has been repaired.

16 Sub-section 72(4) provides that in applying sub-section 72(3) a Court must apply the standard of the informed user.

17 Sub-section 72(5) provides definitions of two presently relevant terms as follows (omitting the presently irrelevant definition of “standard of the informed user”):

repair, in relation to a complex product, includes the following:

(a) restoring a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product to a good or sound condition;

(b) replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product with a component part in good or sound condition;

(c) necessarily replacing incidental items when restoring or replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product;

(d) carrying out maintenance on the complex product.

use, in relation to a product, means:

(a) to make or offer to make the product; or

(b) to import the product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(c) to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, or offer to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, the product; or

(d) to use the product in any other way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) to keep the product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d).

18 There is no dispute that several of the qualifying requirements for the operation of the s 72 defence have been met. SSS accepts for the purposes of sub-section 72(1)(a) that it has used products (the impugned parts or the SSS parts identified in Table 2 at paragraph [27] below) in relation to which there is a registered design and that each impugned part embodies a design that is identical, or substantially similar in overall impression, to a GMGTO registered design. The parties also accept that each of the impugned parts is a component part of a complex product within the meaning of sub-section 72(1)(b). However, SSS contends that the use of each of the impugned parts is for the purpose of the repair of the complex product so as to restore its overall appearance in whole or part, in accordance with sub-section 72(1)(c) and has asserted in these proceedings that because of the operation of sub-section 72(1), it did not infringe the registered designs.

19 The consequence is that the bulk of the argument between the parties, and the consideration of the facts of the case, turn on whether or not GMGTO has discharged the onus placed on it by sub-section 72(2)(b) of the Designs Act, namely:

the burden of proving that the person [in this case, SSS] knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the use or authorisation was not for the purpose mentioned in paragraph (1)(c).

20 The purpose mentioned in sub-section 72(1)(c) is that of repair of the complex product (in the present case a motor vehicle) so as to restore its overall appearance in whole or in part, which I refer to as the repair purpose.

21 In its Reply to the Defence to infringement and, more specifically, in its Amended Further and Better Particulars of the Reply dated 26 October 2017 (reply particulars), GMH sets out how it advances its case. It contends that one or other of the SSS parties has infringed by:

(1) importing;

(2) keeping for sale;

(3) offering for sale; and

(4) selling or otherwise disposing of,

the impugned parts. As I have mentioned, within their allegation of infringement by selling, GMH has pleaded transactions reflected in over 1,300 invoices issued by SSS to 17 of its customers. At trial, GMH initially contended that the Court should determine whether it had established that SSS did not hold the requisite repair purpose in respect of each transaction. That has been reduced to 26 representative sample transactions between one or other of the SSS parties and 9 of their customers.

22 The final form of the cross-claim was filed (with leave) after the conclusion of the trial, on 24 April 2018. It is brought in relation to 11 specific threats, 10 to spare parts suppliers who have obtained products from SSS, and 1 to SSS itself. The cross-claim relies on correspondence between GMH and the parts suppliers as reflected in Exhibit B. Little time was spent in closing submissions addressing the particular courses of conduct, although it has been necessary in these reasons to go through each.

23 I have concluded that, in relation to the GMGTO claim, GMGTO has failed to establish that the importation, keeping for sale or offer for sale of the impugned SSS parts was not for a repair purpose within the meaning of s 72 of the Designs Act. It has also failed in respect of all representative transactions nominated for the purpose of considering infringement by selling the impugned parts with the exception of; transactions 1, 6, 7 and 8 (in relation to W & G Smash Repairs only) involving SSS Sydney; transactions 15 and 17 (in relation to sales (1), (2), (3) and (5) only) involving SSS Melbourne; and transactions 25 and 26 involving SSS Queensland.

24 As a broad observation, I note that the case as presented by GMGTO in relation to its claim tended to be based on what I consider to be unrealistic expectations as to what individuals (whose knowledge could be attributed to an SSS party) knew or ought reasonably to have known about a transaction. As a result of legitimate concerns that GMH would commence lengthy, detailed and expensive proceedings against it, SSS introduced a series of policies designed to ensure and demonstrate that sales made were for a repair purpose. This ultimately led to SSS implementing controls on the sale of the impugned parts that appear to be similar to the controls implemented by GMH itself. It is difficult to imagine that the legislators had this in mind when s 72 was enacted. Nevertheless, in order to consider the application of the s 72 defence, it has been necessary to consider each transaction, and the purpose of SSS in the context of each alleged act of infringement. Ultimately, GMGTO has succeeded in respect of a relatively small number of representative transactions, the value of which (seen in the context of this litigation) is likely to be small compared to the costs involved.

25 In relation to the cross-claim, I have found that the SSS cross-claimants have succeeded in only very limited respects. Although the GMH correspondence was undoubtedly aggressive and, in some respects, inaccurate, I have concluded that in the main it did not involve unlawful conduct in the manner contended. I have concluded that there were unjustified threats to bring design infringement proceedings in relation to the Panel House, CarParts and Torq parts suppliers by reason of the fact that Designs 7 and 12 were never certified. Further, an unjustified threat to bring copyright infringement proceedings was made in relation to the relevant letters of demand to Holmart. I will hear submissions from the parties as to the appropriate relief to grant, if any.

2. THE REGISTERED DESIGNS AND THE SSS PRODUCTS

26 GMGTO is the registered owner of the designs set out in Table 1 below (Registered Designs). It is necessary for consideration of the cross-claim to identify the filing date, expiry date and date of certification of each design. Design numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 are asserted by GMGTO in its infringement claim.

Table 1: The relevant GMGTO registered designs

No. | Australian Design Reg. No. | Article/product name | Priority Date | Certification Date | Period of registration cannot exceed | Expiry / cessation date (if any) |

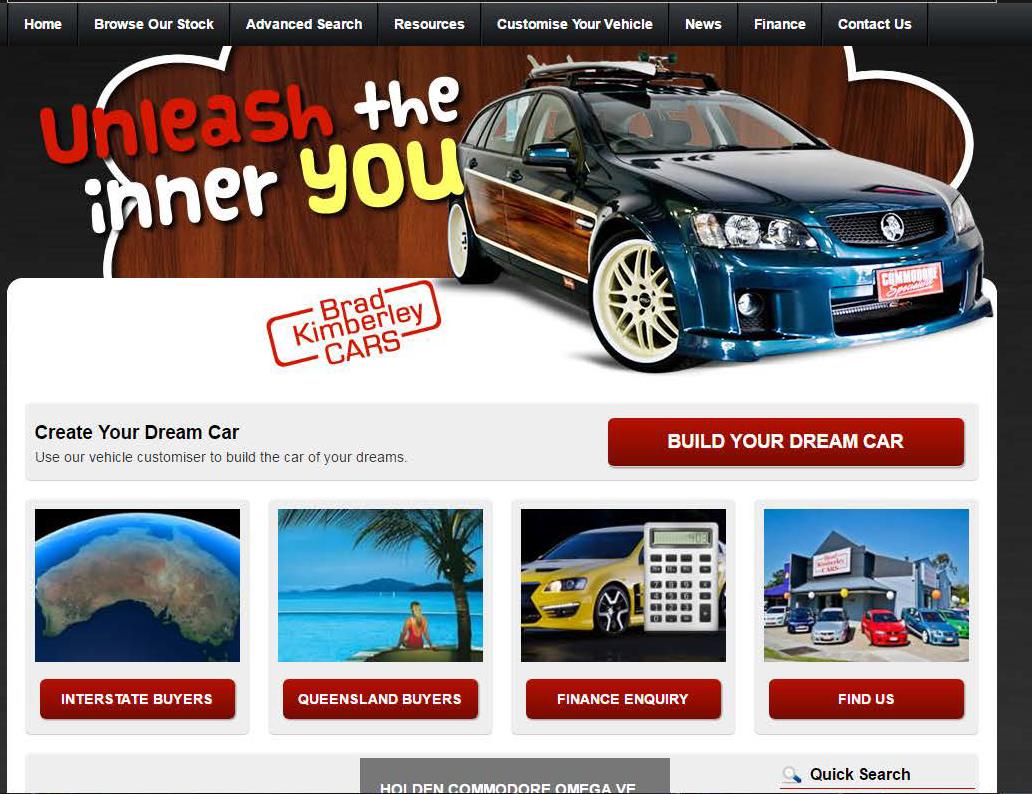

1 | 323875 | Vehicle fascia | 3 September 2008 | 6 August 2014 | 3 September 2018 | - |

2 | 311413 | Vehicle fascia | 16 March 2006 | 9 September 2014 | 16 March 2016 | 16 March 2016 |

3 | 311300 | Vehicle fascia | 16 March 2006 | 3 October 2014 | 16 March 2016 | 16 March 2016 |

4 | 333688 | Vehicle front fascia | 14 May 2010 | 3 October 2014 | 14 May 2020 | - |

5 | 157527 (registered under Designs Act 1906) | Vehicle bonnet | 31 May 2004 | Not applicable under 1906 Act | 31 May 2020 | |

6 | 142910 (registered under Designs Act 1906) | Vehicle front grille fascia | 15 December 1999 | Not applicable under 1906 Act | 16 December 2015 | 16 December 2015 |

7 | 333685 | Vehicle radiator grille | 14 May 2010 | Never certified | [14 May 2020] Ceased registration before end of term | 14 April 2015 |

8 | 324781 | Left-side and right-side vehicle lamp assemblies | 16 December 2008 | 28 August 2014 | 16 December 2018 | - |

9 | 325150 | Vehicle grille | 30 January 2009 | 25 August 2014 | 30 January 2019 | - |

10 | 325151 | Left-side and right-side vehicle lamp surrounds | 30 January 2009 | 25 August 2014 | 30 January 2019 | - |

11 | 325153 | Left-side and right-side vehicle grilles | 30 January 2009 | 26 August 2014 | 30 January 2019 | - |

12 | 316380 | Vehicle hood | 18 June 2007 | Never certified | [18 June 2017] Ceased registration before end of term | 16 April 2015 |

13 | 325159 | Vehicle hood header | 30 January 2009 | 14 October 2014 | 30 January 2019 | - |

27 The impugned parts that have been imported and sold by SSS are described below. The bolded abbreviations in the second column are used later in these reasons to identify particular SSS parts.

Table 2: the impugned parts

No | SSS Part No. | SSS Part Description | Corresponding Holden / HSV Part | Registered Design No. | First sale date |

1 | IV11545NBB | B. COVER RR VE 06-10 SEDAN, SV6 | VE SS/SV6/SS-V Series 1 & 2 sedan rear bumper | 311300 | 30/11/2012 |

2 | IV11540NBB | B. COVER FR VE 06-10 ALL S | VE SS/SV6/SS-V Series 1 front bumper | 311413 | 4/5/2011 |

3 | ISV1540NAA | B.COVER FR BL VE 10-ON F4 EXCE | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo/GTS front bumper | 323875 | 29/7/2013 |

4 | ISV1500NJL | FRT DRL LH VE 10-ON | E2/E3 HSV daytime running lamp (left hand) | 324781 | 17/4/2014 |

5 | ISV1500NJR | FRT DRL RH VE 10-ON | E2/E3 HSV daytime running lamp (right hand) | 324781 | 17/4/2014 |

6 | ISV1560NAA | B. GRILLE FR BL VE 10-ON F4 EXC | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo/GTS lower grille | 325150 | 29/7/2013 |

7 | ISV3500NAL | GRILLE LH BL VE 10-ON F4 EXCEP | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo/GTS upper grille (left hand) | 325151 | 29/7/2013 |

8 | ISV3500NAR | GRILLE RH BL VE 10-ON F4 EXCEP | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo/GTS upper grille (right hand) | 325151 | 29/7/2013 |

9 | ISV1500NEL | F. LAMP COV LH BL VE 10-ON F4 E | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo fog lamp cover (left hand) | 325153 | 29/7/2013 |

10 | ISV1500NER | F. LAMP COV RH BL VE 10-ON F4 E | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo fog lamp cover (right hand) | 325153 | 29/7/2013 |

11 | ISV0560NBH | BN. MLD BL VE 10-ON | E2/E3 HSV Clubsport/Maloo bonnet moulding (satin black) | 325159 | 8/8/2014 |

12 | ISV0560NCC | BN. MLD CH VE 10-ON | E2/E3 HSV GTS bonnet moulding (chrome) | 325159 | 8/8/2014 |

13 | IV21540NBB | B. COVER FR VE 10-13, SV6/SS | VE SS/SV6/SS-V Series 2 front bumper | 333688 | 30/11/2012 |

28 It will be seen from Table 2 that the SSS part numbers in rows 1, 2 and 13 above concern VE model Commodores (impugned VE parts), and those in rows 3 – 12 relate to HSV parts (impugned HSV parts).

29 I generally found that the witnesses who were cross-examined did their best to assist the Court and to tell the truth. GMH submits that there is a common theme of divergence in crucial respects between the written evidence of the SSS witnesses and their oral evidence. I reject that as a blanket criticism. Where GMH otherwise makes specific criticism of a witness, I address it, if relevant, in the context of the particular issue to which it relates. As a general point, I observe that a number of the witnesses for SSS did not speak English as their first language and one (Mr Chuah) required the assistance of an interpreter. On occasion, email and other written communications use truncated, abbreviated or stilted English. In the main part, it is relatively easily understood. Often concerns relating to the registered design rights are referred to as “design patents”, “patents”, “patent rights” or the like. Nevertheless, it is usually clear that the reference is to rights under the Designs Act.

30 Michael Dennis Finn has, since 1997, been the National Parts and Accessories Manager of Premoso. Premoso is a niche designer, manufacturer and distributor of high performance road vehicles catering to performance car enthusiasts under the brand “Holden Special Vehicles” or “HSV”. Mr Finn gives evidence about the background and history of HSV vehicles, the replacement of HSV parts and the manufacturer of HSV vehicles. He also gives evidence of the practice of “upspeccing” which he describes as an aftermarket industry catering to vehicle owners wanting to customise or upgrade the appearance and performance of their vehicles. Mr Finn gives evidence that he believes that there is a significant demand amongst car enthusiasts to fit HSV unique parts, or an authorised replica version of those parts, to lower specification vehicles in order to customise their appearance. Mr Finn gave three affidavits and was cross-examined.

31 Emmanuel Vlontakis has, since January 2015, been the Engineering Group Manager in the Warranty and Quality Team of GM and in that role has been responsible for the management of tracking and the resolution of warranty issues. In earlier roles with the company he has managed various engineering teams responsible for the design and development of automative body and seating systems for certain vehicles including the VE Commodore. He has been employed at GM Holden since 1987. Mr Vlontakis gives evidence in reply about the Pontiac G8, VE Chevrolet grilles and VE LED headlamps. Mr Vlontakis gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

32 Peter William Hughes has, since 2006, been the Design Manager - Exteriors for General Motors Australia Design, which is a business division of GM. He gives evidence about the design process at GM and provides details of the visual and design differences amongst different Holden models with particular emphasis on the VE Holden Commodore range. He also gives evidence of the cross-compatibility of parts, observing that a major objective of his design team since about 2006 has been to increase the interchangeability of parts that can go on to a basic car frame. Mr Hughes gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

33 Robert Bruce McDonald is a mechanical engineer who obtained a Diploma of Mechanical Engineering in 1977 from Granville TAFE, and a Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical) from the University of Technology Sydney in 1990. He has had an extensive career in the automotive industry which has included, from 1986 until April 2017, working for NRMA Insurance and its successor following demutualisation, Insurance Australia Group. He was responsible for a variety of public programs that concerned vehicle damageability and repairability, anti-theft resistance and insurance assessor technical advice and training. Mr McDonald gives opinion evidence concerning the way in which genuine and aftermarket parts are distributed, sold and fitted in the automotive panel repair industry and the process by which the owner of the vehicle ordinarily would go about repairing the body of their car, whether by claiming through an insurance policy or otherwise. Mr McDonald gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

34 Gregory Michael Pieris is a solicitor employed by K&L Gates, the solicitors representing GMH. He gives evidence about the chain of custody of certain product parts and, in an affidavit served in reply, gives evidence in answer to affidavits given by 5 SSS witnesses. Mr Pieris gave two affidavits and was cross-examined.

35 Bradley Daryll Searle has, since around 2010, been the manager of Brad Kimberley Cars, a car customisation and second-hand car sales business conducted by NathanPark Pty Ltd, which was supplied parts by a related company, Brad Kimberley Wheels and Tyres Pty Ltd (BKWT). Mr Searle gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

36 Fiona Elizabeth Harden was General Counsel of GM, from 2007 until 2017, after which she was the Lead Counsel. She exhibits the registered designs in suit. Ms Harden gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

37 Mark Wakeman has, since October 2014, held the position of Leader Specialist Engineer in the Product Investigations Group of GM. He has been employed by that company since 1998. He gives evidence that the role of the Product Investigations Group includes the investigation of safety and performance issues arising from Holden vehicles. Mr Wakeman particularly addresses the role of vehicle identification numbers, or VINs, to identify vehicles affected by a particular fault or defect. Mr Wakeman gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

38 Simon Ranjitan Casinader is a solicitor employed by K& L Gates. His evidence concerns various eBay listings and websites and the results of various searches of identified companies. Mr Casinader gave one affidavit and was not cross-examined.

39 Timothy Michael Guy was a solicitor employed by K&L Gates. He gives evidence of a similar nature to that of Mr Casinader. Mr Guy gave one affidavit and was not cross-examined.

40 Lim-S Ung is the sole director of SSS Melbourne, SSS Sydney, SSS Queensland and SSS Adelaide. Mr Ung (who is also referred to in the evidence as Mr Lim) arrived in Australia in the early 1980s. Before coming to Australia he had worked in Japan dismantling cars for spare parts that would then be shipped back to Thailand. In the mid-1980s he started importing second-hand spare auto parts, initially for the supply to wrecking yards which bought the parts and on sold them. In about 1987 he hired a warehouse and started selling spare parts directly. Mr Ung gives evidence about the history and structure of the SSS businesses and the nature of their activities. He refers to his companies’ past dealings with GMH, his knowledge of the right of repair under section 72 of the Designs Act and his responses to various matters raised by GMH. Mr Ung gave one affidavit and was cross-examined. His first language is Mandarin. My impression was that Mr Ung spoke reasonably fluent English, but did not have the nuanced appreciation of language of a native English speaker. I have made allowances for this in considering his evidence.

41 Kun Chuah has, since about 2009, been the National Product Development Manager at SSS. Mr Chuah immigrated to Australia in January 2000 with the assistance of his uncle, Mr Ung. Since then he has worked in various positions in SSS Melbourne before his promotion to his current role. In his affidavit he identifies that he has day-to-day responsibility for the development and purchasing of new products for each of the SSS parties, as well as SSS Adelaide. Mr Chuah gives evidence about the general process that he engages in when purchasing parts for SSS, its inventory, the acquisition of the parts that are the subject of the present proceedings and the measures that SSS took to respond to demands made by GMH. Mr Chuah provided one affidavit and was cross-examined. He was by no means fluent in English, and gave the bulk of his oral evidence with the assistance of an interpreter.

42 Laurie Alan Wills has, since 1995, worked in the automotive industry. He joined SSS Melbourne in about 2004 and since about 2006 has held the position of Sales Manager for that company. In that role, 5 Sales Executives report to him. He reports to the SSS Melbourne Branch Manager, Chai Lim. He gives evidence about his role at SSS Melbourne, a general overview of its sales processes and details of the operations of SSS relevant to the claim by GMH. Mr Wills gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

43 Richard Morton King has been employed by SSS Queensland since 2007 and has been a Sales Manager since 2012. Mr King reports to Mr Alan Lee, who is the Branch Manager for SSS Queensland. Mr King gives evidence that he has day-to-day responsibility for supporting a team of sales executives for SSS Queensland. He gives a general overview of SSS Queensland’s sales and gives evidence broadly in response to the case advanced by GMH. In this regard he directly responds to the evidence of Mr Searle regarding the business of BKWT. Mr King gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

44 Kee Yeong Neoh has, since late 2008, been an employee of SSS Melbourne, initially as a systems engineer responsible for the upgrade and migration of its computer-based accounting system and subsequently in the role of Information Technology Manager. He is Mr Ung’s nephew and his sister is Ms Teng Neoh, whom I discuss in paragraph [45] below. Mr Neoh identifies that each of the SSS parties and SSS Adelaide use a centralised computer software system in the management of their inventory, customers, accounts and sales information. He also gives evidence in relation to certain invoice reprints that were produced for the litigation, the implementation of compliance measures in response to demands made by GMH and the location of customers referred to in the GMH particulars. Mr Neoh gave one affidavit and was not cross-examined.

45 Teng Neoh is an employee of SSS Sydney and has, since 2007, occupied the role of National Operation Manager. In that role she has day-to-day responsibility for managing the operations of each of the SSS parties and SSS Adelaide. Ms Neoh is the niece of Mr Ung and the sister of Mr Kee Neoh. She was awarded a Bachelor of Applied Science from RMIT University, Melbourne in 1996; a Master of Management from Macquarie University, Sydney in 2004; and a Master of Business Administration from Macquarie University in 2005. She gives evidence about her management role at SSS Sydney, the senior management structure of SSS, the way in which SSS sources parts and various other aspects of the SSS business. Ms Neoh gave two affidavits and was cross-examined.

46 Martin Junia Nikic has, since January 1996, been employed by SSS Sydney and, since 2005, has held the position of Sales Manager. He reports to Ms Neoh in her capacity as the Branch Manager for SSS Sydney. He gives evidence relevant to the operations of SSS Sydney and responds to aspects of the evidence relied upon by GMH. Mr Nikic gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

47 Soon Hooi Lee (Alan Lee) has, since around 2000, been employed by SSS Queensland in the role of Branch Manager. Prior to that, from 1991 he was employed by SSS Melbourne in various positions. Mr Lee received a Diploma in Electrical Engineering from the Institute of Technology Jaya in Kuala Lumpur in 1988. He immigrated to Australia in 1990 and is related to Mr Ung by marriage. Mr Lee gives evidence about his role at SSS Queensland, about the implementation of the “repair only” policy by SSS Queensland, in response to Mr Searle concerning BKWT and in response to the case advanced by GMH more generally. Mr Lee gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

48 Christopher Khalil is a paralegal in the employ of Benjamin Lawyers, the solicitors for SSS. He put into evidence various search results and website materials. Mr Khalil gave one affidavit and was not cross-examined.

THE GMGTO CLAIM – DESIGN INFRINGEMENT

4. LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF THE GMGTO CLAIM

4.1 The claim as set out in the reply particulars and the “Knowledge Factors”

49 The s 72 defence requires GMH to establish that a relevant SSS party knew or ought reasonably to have known that the “use” of the impugned part in question was not for the repair purpose. In the interlocutory stages of the proceeding, SSS contended that GMH had failed to meet its obligations to provide particulars pursuant to r 16.43 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR). That was resolved by the reply particulars provided by GMH in August 2017 (they were later amended and took their final form on 26 October 2017). Subsequently, SSS filed its evidence in answer to the claim. The case was accordingly conducted on the basis of the case as articulated in the reply particulars and SSS made forensic decisions on the basis of their content, including as to which witnesses to call.

50 It is a central part of the case advanced by GMH that the knowledge of various named individuals is to be attributed to the knowledge of the relevant SSS entity accused of infringing the GMH designs. I consider the legal requirements for the imputing of knowledge to a corporation in the next section of these reasons.

51 A party who pleads a condition of mind must state in the pleading the particulars of the facts on which the party relies; r 16.43(1) of the FCR. In this regard, “condition of mind” includes “knowledge”; r 16.43(3)(a) of the FCR. When pleading that a party ought to have known something, particulars of the facts and circumstances from which the party ought to have acquired the knowledge must be given; r 16.43(2) of the FCR.

52 In Lee v Westpac Banking Corporation [2015] FCA 467, Dowsett J said:

[25] It follows that a party pleading the imputed knowledge of a company must identify in its pleadings:

• any agent, officer, employee or other person whose relevant knowledge the pleader seeks to attribute to the company, identifying such knowledge and otherwise complying with the requirements of r 16.43 of the Rules;

• the basis for imputing such knowledge to the company by reference to each person’s “closeness” and “relevance” to the company in question, again complying with r 16.43; and

• if the party seeks to aggregate the knowledge of two or more employees, the basis for so doing.

[26] The questions of closeness and relevance will frequently involve an examination of the relevant person’s duties and functions within and/or on behalf of the company, including reporting and supervisory responsibilities and inter-relationships with other agents, officers or employees and, possibly, with external persons or entities. Such an enquiry may be further complicated by informal variations of formal arrangements.

53 These observations are apposite in the present case. As the SSS parties are corporations, the knowledge necessary to establish the repair purpose must be attributed to the relevant corporation via a human actor. The reply particulars identify the specific individuals whose knowledge GMH relies upon. On occasion, the case as advanced in closing submissions strayed from the particulars. In particular, on a number of occasions GMH sought to rely on the actual or imputed knowledge of individuals who had not been identified in the reply particulars. It also submitted that the knowledge of certain individuals should be aggregated with the knowledge of another. In the case of both, SSS complains that GMH has deviated from its pleaded case. These matters are addressed in more detail later in these reasons. However, for present purposes I note that the complaint is well founded.

54 In relation to the alleged infringement by importation and keeping, in its Reply Particulars GMH contends that Mr Ung, Mr Chuah and Mr Lee had actual knowledge that such use was not for the repair purpose. In the alternative, GMH contends that Mr Ung, Ms Neoh and various sales managers for SSS Queensland, SSS Sydney and SSS Melbourne ought reasonably to have known that the said importation and keeping was not for the repair purpose. In closing submissions GMH’s case was confined to the actual knowledge of Mr Ung and Mr Chuah, with a fleeting reference to Mr Lee and to the constructive knowledge of Mr Ung alone.

55 The reply particulars set out 9 matters by reason of which GMH contends that the named individuals ought reasonably to have known that the importation and keeping was not for the repair purpose, which I refer to below as the Knowledge Factors, namely that:

(1) There was consumer demand for the impugned parts to be used for the purposes of customisation and enhancement amongst owners of Holden vehicles;

(2) There was limited consumer demand for the impugned parts to be used for the purpose of repairing the vehicle models to which the parts were originally fitted;

(3) Having regard to (1) and (2) above, the number of the impugned parts imported and supplied by SSS was higher than SSS could have reasonably expected would be used for a repair purpose;

(4) The nature or name of the businesses to which SSS offered for sale or sold the impugned parts (as set out in the reply annexure) was indicative that the customer had not used and would not in the future use all or some of the impugned parts for the repair purpose;

(5) The high number of impugned parts acquired by a particular customer in a single order listed in the reply annexure made it likely that some or all of the impugned parts were not being used by that person for the repair purpose;

(6) The high frequency of the acquisition by the SSS customer of the impugned parts was such that it was likely that some or all of the impugned parts were not being used by that person for the repair purpose;

(7) The combination, number and relationship of the parts to the overall appearance of the vehicle were such that it was likely that some or all of the impugned parts were not being used by that person for the repair purpose. This includes where:

(a) one or more contemporaneous transactions to a single customer included one or more "kits" comprising a set of individual fascia components that fit into the front fascia;

(b) a single transaction included one or more pairs of corresponding left and right hand parts in a single transaction; and

(c) one or more contemporaneous transactions included a bonnet moulding together with a front fascia or bonnet or both;

(8) The conduct of the customer when required to supply a Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) or otherwise to authenticate that a sale was for repair was such that it was likely that some or all of the SSS parts were not being used for a repair purpose (for example, where the customer supplied an incorrect VIN, incorrect registration number or abused the SSS staff when asked to supply such details);

(9) Having imported, offered to sell and sold the impugned parts since May 2011, SSS later implemented various measures to restrict the use of those parts for purposes other than repair, such as using disclaimers on invoices or product labelling and requiring the provision of VINs.

56 In relation to alleged infringement by offering for sale, GMH has provided no detail in its reply particulars. In a single page of closing submissions it appears that the case is based on the actual knowledge of either Mr Nikic, the NSW sales manager, or Ms Neoh.

57 The bulk of the case advanced by GMH is based on alleged infringement by selling. It relies on the knowledge of Mr Wills for SSS Melbourne, Mr Kevin Woolfe and Mr Nikic for SSS Sydney and Mr King for SSS Queensland. In addition, the reply particulars identify Ms Neoh and Mr Ung as having the relevant actual knowledge. By paragraph 1(e) of its reply particulars, GMH contends that actual knowledge is to be inferred by having regard to the Knowledge Factors. Alternatively, GMH contends that the same individuals ought reasonably to have known that the use of the impugned parts was not for the repair purpose by reason of the Knowledge Factors.

58 The case as advanced in closing submissions by the parties focuses on the 4 alleged overarching infringing uses by SSS, being importation, keeping, offering for sale and selling the impugned parts. The first and last of these are the most extensive. Before turning to each of these, it is convenient to consider the scope, purpose and requirements of ss 71 and 72 of the Designs Act, and the legal requirements for the attribution of corporate knowledge to one or more individuals. I address these matters in the balance of this section. I then turn to make findings in relation to some relevant Background Facts (section 5) concerning GMH vehicles and the SSS businesses, before setting out a chronology of relevant events. These matters inform later consideration of factual issues raised, including the Knowledge Factors. I then turn to consider separately the alleged infringing uses.

59 The Designs Act was introduced into Parliament on 11 December 2002. In the second reading speech delivered on that day, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources, the Hon. Warren Entsch MP, indicated that the new Act would repeal the Designs Act 1906 and implement a new registration system for industrial designs. He said that this represented a fundamental change to the registration and protection of industrial designs and was the culmination of many years of review and consultation.

60 After discussing various aspects of the new Act, the speech relevantly said of the new section 72 (emphasis added):

Another important aspect of this bill is the exclusion of spare parts from protection under the new designs system. The government recognises that whether or not spare parts should be eligible for design protection is a complex issue, and after careful consideration believes that this exclusion is warranted. In reaching this decision, the government was concerned to ensure effective competition in the spare parts market leading to lower prices for consumers, for example, motorists in the case of spare parts for motor vehicles. An exclusion should give consumers greater choice and lower prices when they are looking to purchase spare parts to repair or restore complex products to their original appearance.

The bill implements the spare parts exclusion by a `right of repair' exemption. This will still allow the design registration of component parts of a complex product but use of design registered parts for repair purposes, for example, as spare parts, will provide a complete defence against infringement. The use of design registered parts for non-repair purposes will be an infringement of the registered design but the onus will be on the design owner to prove that parts were being used for non-repair purposes. This approach recognises that component parts of a complex product can either be used as original equipment or as spare parts, and seeks to strike a balance between providing an incentive for creative activity in design and enabling competition in the spare parts market. It will provide protection for original equipment use by allowing new and distinctive designs of component parts of complex products to be registrable. However, where design registered component parts are used as spare parts for repair or replacement purposes there would not be an infringement.

61 It may be noted from these paragraphs that the purpose of the s 72 defence balances competing interests. On the one hand, there is a desire to provide incentive for creative activity in design by retaining the protection of a design registration for spare parts for complex products and on the other, there is a desire to strike a balance to enable competition in the spare parts market by placing the onus on the design owner to prove that the parts were being used for non-repair purposes. It is plain that the interests of the motor vehicle industry were particularly taken into account in considering s 72.

62 The Explanatory Memorandum (EM) to sub-sections 72(1) and (2) provides as follows (emphasis added):

Subclause 72(1)

107. This subclause provides a complete defence against infringement where a component part embodying a registered design is used for repair purposes without the authorisation of the design owner. It includes the use of a component part embodying a design that is substantially similar in overall impression to a registered design. To satisfy this subclause, the complex product needs to be repaired (as defined in subclause 72(5)), and to have its overall appearance restored in whole or in part (as defined in subclause 72(3)). However, this subclause does not provide a defence against infringement where the use of a component part embodying a design results in the enhancement of the appearance of the complex product. This approach preserves the incentive to innovate by allowing all designs of component parts of complex products to be registered if they meet the innovation threshold, without introducing any risk of subsequent anti-competitive behaviour. This enables original component parts to be protected, while the same or substantially similar component parts may be used for repairs without the risk of infringement.

Subclause 72(2)

108. This subclause provides that the onus is placed on the owner of the registered design to prove that parts were being made, supplied or used for non-repair purposes. To place the onus on the suppliers or manufacturers of spare parts would act as a disincentive for new participants to enter the spare parts market. It would force suppliers and manufacturers of spare parts to track their entire inventory to see whether they all are being used for genuine repair purposes.

109. Nevertheless, if suppliers or manufacturers are knowingly participating in using parts for non-repair purposes, or should have reasonably known that they are doing so, then they should not be able to hide behind the right of repair defence.

63 Earlier in the EM, it is noted that the Designs Act was prepared after extensive consultation with designers and manufacturers, as well as legal practitioners in the field. The EM describes a key issue as being the competition concern relating to spare parts, which had been the subject of much policy debate over recent years. The concern identified is that when spare parts are protected under design legislation, producers who may not have market power in a primary market for the complete goods may be able to charge a monopoly price for spare parts in the after-market in which spare parts are sold. Apart from consumers being charged higher prices for parts, competition may be restricted for the repair and servicing of original equipment.

64 The EM sets out an assessment of the costs and benefits of several options for addressing the balance between competing interests. It accepted “Option 2”, the ultimate right of repair provision, over “Option 1” which was an exclusion of ‘must fit’ or ‘must match’ parts. In [61] the EM conducts an assessment of the benefits of each by reference to the interests of the Government, industry and consumers. It says in respect of the benefits for industry in adopting Option 2, the right of repair provision:

Component suppliers would be protected in their dealings with larger manufacturers of original equipment, such as motor vehicle manufacturers (without design protection there would be nothing to stop the larger manufacturers from free-riding on the design innovations of the independent suppliers). Items that show innovation in design and do not, in practice, give rise to competition concerns (such as the specialised parts associated with the Holden HSV and Ford Tickford range of vehicles) would also be protected, where they are used in the practice of ‘fitting-up’ a standard model (but not when they are used for genuine repair). This overcomes one of the major shortcomings of Option 1.

65 The reference to “fitting-up” a standard model is a reference to what has been referred to in the present case as “up-speccing” which includes the practise of acquiring spare parts for a base model vehicle and then up-grading its appearance to make it look different, quite often to make it appear like a more expensive model.

66 SSS tendered a 30 April 2003 letter from a senior executive of GMH to the Secretary of the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, providing GMH’s comments on the Designs Bill 2002 (Cth) and Designs (Consequential Amendments) Bill 2002 (Cth). However, in my view, particular comments of industry participants do not represent a suitable means for interpreting the current legislation, and I set it to one side; see s 15AB of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth); Australian Communications and Media Authority v Clarity1 Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 410 at [47].

4.3 Consideration of s 72(2)(b)

67 Sub-section 72(2)(b) quite deliberately places the onus on the registered owner to establish that the alleged infringer did not have the repair purpose. This is significant, and reflects one means by which Parliament intended to achieve the balance between the interests to which the secondary materials refer. Clearly enough, it was the legislative intent that s 72 should provide a significant degree of protection to the alleged infringer. See, by analogy, Nintendo Company Limited v Centronics Systems Pty Ltd [1994] HCA 27; (1994) 181 CLR 134, at [19].

68 GMH’s reply particulars rely upon actual or constructive knowledge. The existence of actual knowledge is a question of fact, the proof of which, in the absence of an admission by a party, is always a matter of inference; RCA Corporation v Custom Cleared Sales Pty Ltd (1978) 19 ALR 123 (NSWCA, Hope, Reynolds, Hutley JJA) at 125. The materials from which the inference may be drawn will vary, according to the particular facts and circumstances of the case. In inferring knowledge, the Court is entitled to assume that the person concerned has the ordinary understanding expected of persons in his or her line of business, unless by evidence it is convinced otherwise.

69 In RCA Corporation, the NSW Court of Appeal said at 126:

In other words, the true position is that the court is not concerned with the knowledge of a reasonable man but is concerned with reasonable inferences to be drawn from a concrete situation as disclosed in the evidence as it affects the particular person whose knowledge is in issue. In inferring knowledge, a court is entitled to approach the matter in two stages; where opportunities for knowledge on the part of the particular person are proved and there is nothing to indicate that there are obstacles to the particular person acquiring the relevant knowledge, there is some evidence from which the court can conclude that such a person has the knowledge. However, this conclusion may be easily overturned by a denial on his part of the knowledge which the court accepts, or by a demonstration that he is properly excused from giving evidence of his actual knowledge.

70 GMH relies on a passage from the decision of Burchett J in Richardson and Wrench (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Ligon No 174 Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 488; (1994) 123 ALR 681, where his Honour summarised the principles pertaining to whether shutting one’s eyes to the obvious, or being wilfully blind, may amount to actual knowledge. His Honour said at 693-694:

It is because a reference to a person's shutting his eyes to the obvious, or being wilfully blind, is ambiguous, in so far as it suggests a possible view that something less than actual knowledge will do, that Gibbs CJ (at CLR 487) made it clear a jury should not normally be directed in terms that involve the expression “wilful blindness”...

…

The case is Pereira v Director of Public Prosecutions (1988) 82 ALR 217; 63 ALJR 1. (See also Kural v R (1987) 162 CLR 502 at 507; 70 ALR 658.) Their Honours said in Pereira (at ALR 219–20; ALJR 3):

Even where … actual knowledge is either a specified element of the offence charged or a necessary element of the guilty mind required for the offence, it may be established as a matter of inference from the circumstances surrounding the commission of the alleged offence. However, three matters should be noted. First, in such cases the question remains one of actual knowledge: Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473 at 504–7; 58 ALR 641; He Kaw Teh v R (1985) 157 CLR 523 at 570; 60 ALR 449. It is never the case that something less than knowledge may be treated as satisfying a requirement of actual knowledge … All that having been said, the fact remains that a combination of suspicious circumstances and failure to make inquiry may sustain an inference of knowledge of the actual or likely existence of the relevant matter.

The effect of Kural and Pereira has been stated extra-curially by Dawson J in an article, “Recent Common Law Developments in Criminal Law”, in (1991) 15 Crim LJ 5 at 15:

It was made clear in those two cases that, whilst knowledge as an ingredient of an offence may be established by inference, it must be established as a fact. If the term “wilful blindness” is used merely as a shorthand expression to indicate circumstances which warrant the drawing of the necessary inference, then it is acceptable. But it is unacceptable if it is used as a basis for imputing knowledge where actual knowledge is not proved.

71 By contrast with actual knowledge, constructive knowledge is notice which an agent either received or should have received had he or she made proper enquiries, which is imputed to the principal whether the notice is communicated by the agent to his principal or not: Heydon JD, Leeming MJ, Turner PG, Meagher, Gummow and Lehane’s Equity Doctrines and Remedies (5th ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, 2014) at [8-265]; Wyllie v Pollen (1863) 3 De G J & Sm 596; 46 ER 767; Sargent v ASL Developments Ltd [1974] HCA 40; (1974) 131 CLR 634 at 649; In the matter of NL Mercantile Group Pty Ltd [2018] NSWSC 1337 (Gleeson J) at [80].

72 In NL Mercantile the Court noted at [78] that actual knowledge is to be distinguished from “notice” (or constructive knowledge) and has a positive connotation of awareness; citing In Re Montagu’s Settlement Trusts [1987] 2 WLR 1192 at 1199. In inferring knowledge, for the purposes of determining actual knowledge, it is necessary to consider first, the opportunities for knowledge and lack of obstacles to the particular person acquiring the relevant knowledge and second, the credibility of any denial by the person of such knowledge: RCA Corporation at 126. For constructive notice, a person is deemed to have constructive notice of all matters of which the person would have received notice if the person had made the investigations usually made in similar transactions and of which the person would have received notice had the person investigated a relevant fact which had come to that person’s notice and into which a reasonable person ought to have enquired: Equity Doctrines and Remedies at [8-270]; NL Mercantile at [82].

73 The requirement of proof of constructive knowledge was considered by the Full Court in Raben Footwear Pty Ltd v Polygram Records Inc & Anor [1997] FCA 370; (1997) 75 FCR 88, in the context of the knowledge requirements under ss 102 and 103 of the Copyright Act. Under s 102 of the Copyright Act, there will be an infringement of copyright if an article is imported into Australia without the licence of the copyright owner, for one of the specified purposes, “if the importer knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article would, if the article had been made in Australia, have constituted an infringement of the copyright”. Section 103 of the Copyright Act has a similar knowledge requirement.

74 Burchett J (Lehane J agreeing at 104), after quoting ss 102 and 103 of the Copyright Act, said at 91 (emphasis added):

It will be observed that each of these sections involves an element of actual or constructive knowledge. The alternative, “or ought reasonably to have known,” was inserted into the sections by the Copyright Amendment Act 1991 (Cth), which commenced on 23 December 1991. The amendment reflects an expression that had been inserted, in 1986, into s 132, a section creating various copyright offences. In that section, Pontello v Giannotis (1989) 16 IPR 174, a decision of Sheppard J, treats the same words, in accordance with their literal effect, as setting up an objective test.

The language in which, since 1991, the objective test stated in ss 102 and 103 has been expressed quite closely parallels language which is also relatively new in ss 22 and 23 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (UK). In s 23, the expression is "which he knows or has reason to believe is, an infringing copy of the work". Nourse LJ said of these words, in LA Gear Inc v Hi-Tec Sports plc [1992] 19 FSR 121 at 139: "Since the test is an objective one ... " His Lordship regarded it as clear that it would be sufficient to show "the defendant had knowledge of facts from which a reasonable man would have believed [the item in question to be an infringing copy]". Staughton LJ and Sir Michael Kerr agreed. But, in my opinion, the expression used in the Australian Act does nevertheless allow regard to be had to the knowledge, capacity and circumstances of the particular defendant. An objective assessment is to be made as to whether he, not some other person, "ought reasonably to have known". I note that a similar qualification seems to have been intended to be conveyed by the drafting even of the United Kingdom provision: Laddie, Prescott and Vitoria on The Modern Law of Copyright and Designs (2nd ed, 1995), vol 1, section 10.3.

75 His Honour considered it important to draw attention to these aspects of the construction of the objective aspect of the test which permitted the reliance on less than actual knowledge, because of the change introduced in 1991. His Honour went on to say (at 91):

The change is perhaps not as great as might at first glance be thought, since the authorities I have cited gave a rather special meaning to knowledge in this context; but the express adoption by the legislature of the objective language in question requires a new weight to be attached to the circumstances of each case.

76 The emphasised passages in the two quotations above draw attention to the relevance of the knowledge of a person in the position of the individual concerned and the particular facts of the case. In my view, that is the appropriate approach to take in relation to the application of s 72(1). This in turn draws attention in the present case to the allegations of knowledge as pleaded. As the question of constructive knowledge is objectively addressed, in my view, the appropriate question is what the relevant person, or a person in the same position, ought reasonably to have known having regard to that person’s knowledge, capacity and circumstances.

4.4 The scope of the repair purpose under s 72

77 There was significant debate between the parties as to the operation of s 72 of the Designs Act and the meaning of “purpose” in the context of s 72. GMH submitted in closing submissions that there need only be an overriding, significant, substantial, predominant purpose of repair. It contended that the term “purpose” in s 72 is used together with “use” and should be understood as “purpose” in the sense of “intent”. In this regard GMH submits that if the registered owner proves that the alleged infringer knew or ought reasonably to have known that the product might (rather than would) be used for a non-repair purpose, then the s 72 defence will fail. This, GMH submits, will also be the case if the alleged infringer considers that the product might be used either for repair or for another purpose such as enhancing the appearance of the vehicle. As GMH puts it, the defence will only arise where the alleged infringer “considers that the product will only be used for repair… albeit it would also be intended to make a profit”. GMH gives an example where a customer of the alleged infringer promotes a part as being suitable for both repair and alteration of the vehicle, or the alleged infringer implicitly or actually accepts that the purchaser can do whatever it chooses with the part. It submits that in those circumstances the “purpose” of repair will not be met. The alleged infringer cannot avoid infringement by having a mixed purpose where one purpose derogates from the purpose of repair.

78 In my view GMH’s submissions put the obligation too high. Section 72 contemplates that a part may have a dual purpose – either for a permitted repair purpose or a non-permitted purpose. That is why the knowledge component is required. The secondary materials also contemplate a dual use. On the basis of the GMH argument, any act of manufacture (one form of infringing “use”) would be likely to fail to benefit from s 72 because at the time of manufacture the part could be used for either purpose unless parts are only made to order. That cannot have been the intention of parliament. For instance, it would prevent manufacturers, importers and suppliers from maintaining an inventory of parts which can be sold, which would be impractical and also contrary to the apparent intention of the legislation.

79 This and similar arguments tend to distract from the enquiry required by the section. The starting point is that a product that falls within sub-sections 72(1)(a) and (b) will be capable of being used for more than one purpose; a permitted repair purpose within sub-section 72(1)(c), and a prohibited purpose, such as that alleged in the present context, the enhancement of a vehicle. It is the knowledge of the person who has imported, offered for sale or sold the product that separates the two. If in infringement proceedings an alleged infringer asserts that it had the repair purpose within sub-section 72(1)(c), then it is to be assumed that it had that purpose, unless the registered owner proves otherwise.

80 In the present case, witnesses for SSS asserted on oath that SSS has a policy of selling parts for repair only and that its conduct in importing, keeping, offering for sale and selling the parts was guided by that purpose. GMH seeks to dislodge that evidence by pointing to factors which, it submits, indicate that the evidence of the witnesses is not to be accepted.

81 The parties agreed that the following formula assists in considering the question (emphasis added):

At the point just prior to the relevant use, the Customer’s non-repair use was actually known or a reasonable person in [SSS’] position would consider that the circumstances were such as to create in that person’s mind a belief that he or she knew that the Customer’s intended use was not for repair, such that if [SSS] proceeds with the proposed use, its use became that of the Customer.

82 GMH submits that the concession by some of the SSS witnesses in cross-examination that some parts that they sell might not be used for repair is decisive. However, s 72 focuses on the intention of SSS. It does not require that SSS maintain control over the part after its importation, sale or keeping to make sure that it is ultimately applied to a vehicle for repair or to track the progress of goods it sells through the supply chain. The task that the Court is asked to determine is whether, on the basis of all of the evidence, including the positive evidence that SSS did have the repair purpose, GMH has established that SSS knew or ought reasonably to have known that the importation, sale or keeping was not for that purpose. The concession that a part may ultimately not be used for that purpose was, in most cases, an acknowledgement of the simple fact that SSS did not retain control over its parts and that, being a part that might be used for two purposes, there is a prospect that it will not be used for a repair purpose.

83 In this regard, the immediate question is the purpose of the importer or seller, not of the person who acquires the part from them. The language of s 72 of the Designs Act may be seen as a contrast to sub-sections 117(1) and (2)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), which provides (emphasis added):

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

…

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product—any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; …

84 Pursuant to s 117(2)(b) of the Patents Act, the question is; can it be shown or inferred that the supplier had reason to believe that the product, which it proposes to supply, would be used by recipients in accordance with the patented invention (in that case) contrary to the indications in the approved product information document?; Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 50; (2013) 253 CLR 284 at [304] per Crennan and Kiefel JJ (as the Chief Justice then was). It has been recognised that it is insufficient for the purposes of sub-section 117(2)(b) of the Patents Act for the patentee to show that the supplier had reason to believe that there is a risk that the recipient will put it to an infringing use. Rather, the supplier must have reason to believe that the recipient would put it to an infringing use. As Jagot J said in Apotex Pty Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (No 4) [2013] FCA 162; (2013) 100 IPR 285 at:

[512] I do not accept that s 117(1) and (2)(b) requires AZ to prove that any particular person will split a 20 mg tablet into two 10 mg doses. In the present case the evidence is sufficient to infer that whatever the instructions the generic parties give to medical practitioners and pharmacists there remains a risk that some people will obtain the 20 mg dose of the generic tablets for the purpose of dividing them into two 10 mg doses. Risk, however, is one thing. Proof on the balance of probabilities that any person “would” infringe the 051 or low dose patent is another. Given the steps proposed by the generic parties to instruct medical practitioners and pharmacists not to endorse or encourage tablet splitting, it is a long stretch on the currently available evidence to conclude that any person would split the tablets into 10 mg doses and thereby infringe the patent. I accept that AZ has proved a real risk that it might occur, given the economic incentives. But in terms of proof that is insufficient.

85 Whilst on appeal the Full Court disagreed with her Honour’s factual finding on this issue, her summation of the legal test was not in dispute; see AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99; (2014) 226 FCR 324 at [432]-[444], in particular at [434], [438] and [439]. Similar reasoning may be applied to sub-section 72(2) of the Designs Act in that (in this instance) GMH must establish on the balance of probabilities that SSS must have known or ought reasonably to have known that the use was not for the repair purpose. Proof that SSS knew it “might not” will be insufficient.

86 A manufacturer is highly unlikely to know, at the point that the part comes off the production line, what will ultimately become of it. In the normal flow of commerce, the manufacturer will no doubt sell to a wholesaler, which in turn will sell to a retailer, which in turn will sell to a user. There is no direct link between the infringing act and its ultimate use (the remoteness problem). When the act of making is complete, the manufacturer is unlikely to have any real idea of its ultimate fate. But that is unimportant. The defence is not concerned with the actual use of the part, but the purpose of the manufacture (or other use). What did the manufacturer intend by manufacturing the part? The same observations may be made in relation to other acts of use, although the remoteness problem is more acute at the point of manufacture of a part, and less acute at the retail sale point when the seller is more likely to be dealing directly with the ultimate user.

87 A question raised in the debate between the parties is whether an alleged infringer has a duty to enquire as to what a purchaser may use a product for. This, it seems to me, also distracts from the statutory question. The question is really; on the existing facts, what do the circumstances indicate the alleged infringer knew or ought reasonably to have known based on the facts as proved? In the present case, GMH provides particulars of the Knowledge Factors which form the basis for its contention that SSS knew (for the purpose of its case of actual knowledge) or ought reasonably to have known (for constructive knowledge) that its use was not for the repair purpose. It is by reference to these, in the context of the circumstances of the individuals named, that the question of repair purpose is to be considered.

88 The SSS parties being corporations, the requisite knowledge is that of a human actor within each relevant SSS company alleged in the reply particulars to infringe. In this regard the following propositions may be regarded to be relevant.

89 First, when beliefs or opinions or states of mind are attributed to a company it is necessary to specify some person or persons so closely and relevantly connected with the company that the state of mind of that person or those persons can be treated as being identified with the company so that their state of mind can be treated as being the state of mind of the company; Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd [1995] HCA 68; (1995) 183 CLR 563 at 582-3 per Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and McHugh JJ (approving a passage of reasoning of Bright J said in Brambles Holdings Ltd v Carey (1976) 15 SASR 270 at 279). In Krakowski, the knowledge of certain individuals was found to be the knowledge of the company because they were the persons who were responsible for the initial negotiations and who had set the scene in which the representation had been made and proffered the contract of sale.

90 Secondly, the attribution of knowledge to a company in the manner identified above is not a universal rule. In Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Kojic [2016] FCAFC 186; (2016) 249 FCR 421 (Kojic) (Allsop CJ, Besanko, Edelman JJ), Edelman J said:

[96] Although the “directing mind and will” rule of attribution involves an anthropomorphism which can be misleading, in many cases it presents no difficulty. However, as a rule of attribution it was never intended to be a universal rule. In Lennard’s Carrying itself, the House of Lords was concerned with the construction of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894 and the rule of attribution in that context. In any event, whether or not that rule was intended to be a universal rule, it could never have survived as such. Legislation might expressly provide for a very different rule of attribution. And even if it did not, in a statutory context, rules of attribution must be shaped by the text and context of the statute. The task of statutory construction begins and ends with a consideration of the text itself: Alcan Alumina v Commissioner of Territory Revenue (2009) HCA 41; (2009) 239 CLR 27, 46 [47] (Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ); and Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd [2012] HCA 55; (2012) 250 CLR 503, 519 [39] (French CJ, Hayne, Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ).

91 Beach J has recently in ASIC v Westpac Banking Corp (No 2) [2018] FCA 751; (2018) 357 ALR 240 considered whether or not the knowledge of certain individuals can be attributed to a bank, which was alleged to have acted in breach of provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). He said:

[1660] I have said elsewhere that the conventional approach has been to identify the individual who was the "directing mind and will" of the corporation in relation to the relevant act or conduct and to attribute that person's state of mind to the corporation. But after the injection of flexibility into that concept by Lord Hoffmann in Meridian Global Funds Management Asia Ltd v Securities Commission [1995] 2 AC 500 at 506 to 511, metaphors and metaphysics have had diminished utility. First, there are no longer the rigid categories for identifying the "directing mind and will" that may be perceived to have existed after Viscount Haldane LC's use of the phrase in Lennard's Carrying Co Ltd v Asiatic Petroleum Co Ltd [1915] AC 705 at 713 and indeed after Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1972] AC 153 until Meridian. Second, and relatedly, the appropriate test is more one of the interpretation of the relevant rule of responsibility, liability or proscription to be applied to the corporate entity. One has to consider the context and purpose of that rule. If the relevant rule was intended to apply to a corporation, how was it intended to apply? Assuming that a particular state of mind of the corporation was required to be established by the rule, the question becomes: whose state of mind was for the purpose of the relevant rule of responsibility to count as the knowledge or state of mind of the corporation? see Bilta (UK) Ltd (in liquidation) v Nazir (No 2) [2015] 2 WLR 1168 at [41] per Lord Mance)…

[1661] In the present context, the relevant rule of proscription that I have to consider is that enshrined, inter-alia, in ss 1041A and 1041B. Now, of course, they do not directly refer to questions of purpose let alone dominant purpose. Moreover no mens rea concepts need to be imported from elsewhere (see generally Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Whitebox Trading Pty Ltd (2017) 251 FCR 448). Nevertheless, given the observations in Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v JM (2013) 250 CLR 135, concepts of dominant purpose loom large at least concerning s 1041A and in the way ASIC has framed its case.

[1662] It is sufficient to say for present purposes that in terms of s 1041A and given its focus on a transaction(s), the relevant state of mind is that of the individual person who instigated and carried out the particular trade. Given the freedom of choice and discretion given to Westpac's traders, it seems to me that relevantly for present purposes it is the state of mind of each of Mr Roden and Ms Johnston in relation to their respective trading that should be so attributed to Westpac in relation to the trading in the Bank Bill Market on the contravention dates.

92 The above passages indicate that attribution of knowledge to a corporation will be shaped by the relevant statute. At [1662] of Beach J’s reasons in ASIC v Westpac, his Honour focused on the degree of “freedom of choice and discretion” given to Westpac’s traders as a factor counting towards the finding that the knowledge of those traders was attributable to Westpac. This was because the relevant provision of the Corporations Act (s 1041A) focused on particular transactions that had or were likely to have market manipulation effects. His Honour considered that there were good policy reasons for finding that where the statute focuses on a particular action or transaction, a corporation should not be permitted to claim ignorance merely by giving employees a high degree of discretion to carry out that transaction.

93 I have identified in section 4.1 above the way that GMH has advanced its case in the reply particulars. In some instances SSS disputes whether the knowledge of the person or persons nominated in the reply particulars are capable of having knowledge attributable to the company. However, more often the dispute concerns whether the identified individuals could be said to possess the actual or constructive knowledge alleged. This is no doubt because most of the individuals named are in positions of senior management within the relevant SSS company.