FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Ultra Tune Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 12

Table of Corrections | |

| 23 September 2019 | In paragraph 90, “Spigelmann CJ” has been replaced with “Spigelman CJ”. |

24 January 2019 | In paragraph 261, “a solicitor for” has been replaced with “an employee of”. |

In paragraph 277, “5 October 2015” has been replaced with “4 October 2015”.” | |

24 January 2019 | In paragraph 288, “5 October 2015” has been replaced with “4 October 2015”.” |

24 January 2019 | In paragraph 301, “15 September 2015” has been replaced with “22 September 2015” twice. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | ULTRA TUNE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 065 214 708 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent pay to the applicant a pecuniary penalty of $2,604,000 within 60 days of this judgment.

2. The respondent pay to the applicant $33,000 plus interest within 14 days for the redress of Mr Nakash Ahmed.

3. The applicant pay the sum referred to in order 2 to Mr Nakash Ahmed within 14 days of receipt of the sum from the respondent.

4. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs on an indemnity basis.

5. The parties furnish agreed or competing draft orders and declarations to reflect these reasons within 28 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMWICH J:

1 The respondent, Ultra Tune Australia Pty Ltd, is a franchisor for motor vehicle engine repair and maintenance services provided by a national network of approximately 200 franchises operating in New South Wales (divided into metropolitan and country), Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia.

2 This case is about Ultra Tune’s failure to comply with minimum franchisor obligations, including a number of more serious breaches, and the fabrication of business records in a failed attempt to conceal its wrongdoing. Ultra Tune’s stance at trial and in closing submissions has required detailed and comprehensive reasons to be given to explain why most of its evidence and submissions cannot be accepted.

3 The applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), is Australia’s national franchise regulator. The ACCC is therefore concerned to ensure that all manner of franchisors and franchisees comply with their legal obligations. That is especially so in relation to compliance by franchisors with laws designed to protect the interests of franchisees. The ACCC is concerned to ensure that any case it brings in relation to non-compliance with those laws contributes to future compliance by both the respondent to such a proceeding, and by others engaged in franchise activities.

4 Ultra Tune’s compliance with its minimum legal obligations as a franchisor are central to the proper conduct of its business. In this proceeding, the ACCC alleges that Ultra Tune has contravened mandatory industry codes that regulate the conduct of a franchisor towards its franchisees and prospective franchisees. The applicable codes are:

(1) for conduct by Ultra Tune in the period from 1 July 2011 to 31 December 2014, the “old” Franchising Code of Conduct in the Schedule to the Trade Practices (Industry Codes – Franchising) Regulations 1998 (Cth) (Pre-2015 Code); and

(2) for conduct by Ultra Tune in the period from 1 January 2015 onwards, the “new” Franchising Code of Conduct found in Schedule 1 to the Competition and Consumer (Industry Codes – Franchising) Regulation 2014 (Cth) (Franchising Code).

5 Each code had force for its respective period by virtue of Part IVB of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). Broadly speaking, the codes prescribe minimum standards in franchise agreements and require franchisors to disclose certain information to franchisees and prospective franchisees. Both franchisors and franchisees also have a statutory duty to act in good faith, with civil penalty sanctions for failing to do so.

6 The codes may be seen to facilitate the better working of market forces within the various industries that use franchises as a business model. They encourage the practical advancement of the economist’s ideal of better – if not perfect – information by which to make rational decisions.

7 The ACCC seeks pecuniary penalties in respect of breaches of the Franchising Code and breaches of s 29(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). The ACL is contained in Schedule 2 to the CCA. Civil penalties are not provided for under the Pre-2015 Code.

8 The ACCC also seeks declarations, injunctions, publication orders and compliance orders, as well as certain specific relief by way of a refund for the prospective franchisee who brought the complaint to the ACCC, which led to the investigation and this proceeding.

9 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that the ACCC has established its case against Ultra Tune in relation to all alleged breaches. Declarations and orders as to penalties are to be made accordingly, with those penalties fixed in the substantial sums that have been arrived at, as set out at the end of these reasons, totalling $2,604,000. The other types of relief sought by the ACCC should also be granted.

10 The ACCC also seeks an order for costs of and incidental to the proceedings. As concluded in the penultimate section of these reasons, Ultra Tune should pay the ACCC’s costs of this proceeding on an indemnity basis.

Overview of the alleged contraventions

11 There are two main categories of contravention alleged by the ACCC in this proceeding:

(1) breach of disclosure obligations; and

(2) illegal treatment of a prospective franchisee.

First category of alleged contravention – breach of disclosure obligations

12 The first category of contravention concerns alleged failures by Ultra Tune to comply with various types of disclosure obligations under the codes. The alleged contraventions to which civil penalty consequences attach under the Franchising Code were:

(1) a failure to maintain disclosure documents in relation to Ultra Tune’s four State-based regions, summarised in the table at [15] below (there being a single combined disclosure statement for metropolitan and regional NSW), by failure to update them within four months after the end of the 2015-16 financial year (that is, by 31 October 2015): cl 8(6) of the Franchising Code;

(2) a failure to prepare financial statements for the marketing funds for the five Ultra Tune marketing regions (there being separate funds for metropolitan and regional NSW) within four months of the end of the 2014-15 financial year (that is, by 31 October 2015): cl 15(1)(a) of the Franchising Code;

(3) a failure to ensure that financial statements for the marketing funds for the five Ultra Tune marketing regions included “sufficient detail” for the 2014-15 and 2015-16 financial years: cl 15(1)(b) of the Franchising Code;

(4) a failure to provide to franchisees the financial statements for marketing funds and an auditor’s report for the five Ultra Tune marketing regions relating to the 2014-15 financial year within 30 days of them being prepared: cl 15(1)(d) of the Franchising Code; and

(5) a failure to provide a disclosure statement when requested by a franchisee on 16 December 2015: cl 16(1) of the Franchising Code.

13 With one exception, Ultra Tune admits to the above contraventions. The exception is that Ultra Tune denies the allegation referred to at [12(3)] above that it failed to disclose “sufficient detail” in statements prepared for its marketing funds, contrary to cl 15(1)(b) of the Franchising Code, asserting that the obligation was met. That issue aside, the main areas of controversy between the parties in relation to the alleged disclosure contraventions is to the quantum of the penalties to be imposed, largely based on how many contraventions took place as a matter of statutory construction.

14 The maximum pecuniary penalty that may be imposed for each contravention of the above provisions is $54,000. The maximum pecuniary penalty available multiplied by the number of contraventions has an important bearing on the amount that Ultra Tune is ordered to pay as a proportion of the overall maximum penalty available to be imposed, it not being in dispute that the imposition of at least some pecuniary penalty for the admitted breach of disclosure obligations is inevitable.

15 The number of franchisees affected by the conduct referred to above, for each financial year, was as follows:

Ultra Tune region | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | |||||

NSW Metro | 26 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | |||||

NSW Country | 19 | 19 | 21 | 23 | 24 | |||||

Queensland | 43 | 43 | 50 | 51 | 58 | |||||

Victoria | 33 | 48 | 51 | 58 | 60 | |||||

Western Australia | 14 | 14 | 18 | 21 | 25 | |||||

TOTAL | 135 | 153 | 170 | 185 | 200 | |||||

16 There was a separate Ultra Tune disclosure statement for each of the four States. There was a separate marketing statement for each of the five regions listed in the table above, with separate marketing statements for NSW Metro and NSW Country.

Second category of alleged contravention – illegal treatment of a prospective franchisee

17 The second category of contravention alleged by the ACCC in this proceeding concerns Ultra Tune’s specific dealings with a prospective franchisee, Mr Nakash Ahmed, who is alleged to have been misled in negotiations about the purchase of a franchise in Parramatta in 2015 (Parramatta Franchise). In this regard, it is the ACCC’s case that Ultra Tune breached:

(1) the obligation in cl 6 of the Franchising Code to act in good faith, which carries a maximum pecuniary penalty consequence of $54,000;

(2) the obligation in cl 9 of the Franchising Code to give certain disclosure documents to a franchisee or prospective franchisee (in this case, prospective), which carries a maximum pecuniary penalty of $54,000;

(3) the proscription on misleading or deceptive conduct in s 18 of the ACL (formerly s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)), which carries no pecuniary penalty; and

(4) the same conduct as for s 18, advanced as several different contraventions by way of false or misleading representations contrary to s 29(1)(b), (i) or (m) of the ACL (formerly s 53(aa), (e) and (g) of the Trade Practices Act), each of which at the time of the relevant alleged contraventions carried a maximum pecuniary penalty of $1.1 million for a corporate respondent, being:

(a) alleged false or misleading representations that the franchise Mr Ahmed was proposing to buy had been open for only about six months: s 29(1)(b);

(b) alleged false or misleading representations that the purchase price of the franchise was only $163,000: s 29(1)(i);

(c) alleged false or misleading representations concerning the existence of a condition, namely that a deposit paid by Mr Ahmed was unconditionally refundable, which might also be characterised as going to price: s 29(1)(m), or alternatively s 29(1)(i).

18 Ultra Tune denied the allegations concerning Mr Ahmed at trial and did not indicate otherwise until the exchange of written closing submissions well after the trial. By that time there was effective capitulation as to aspects of the ACCC’s case concerning Mr Ahmed, while other related contraventions continued to be denied.

19 At the heart of the factual dispute concerning Mr Ahmed was a refusal by Ultra Tune to refund $30,000 of a payment of $33,000 that had been made by Mr Ahmed in the course of negotiations. Ultra Tune also contested Mr Ahmed’s reasons for not proceeding with the purchase of the franchise. Mr Ahmed said that he had made that decision as a result of becoming aware that Ultra Tune had provided him with misleading or inaccurate information. The ACCC asserted that this payment was understood to be a refundable deposit and should be returned. The ACCC later asserted that the full $33,000 should be refunded with interest, the additional $3,000 being for a training course that Mr Ahmed attended. At trial, Ultra Tune maintained that the payment was for the purchase of equipment for the franchise site, and that Mr Ahmed could still collect that equipment if he wished to do so.

20 Ultra Tune now accepts the ACCC’s position in relation to the deposit paid by Mr Ahmed and accepts that it should be ordered to reimburse him for the full $33,000 that he paid, but does not accept that he was misled so as to justify him seeking the refund in the first place. To make good that limited concession, the ACCC seeks redress for Mr Ahmed under s 51ADB of the CCA in the form of an order that Ultra Tune refund the full $33,000 deposit, $3,000 of which was for a training course. In the alternative, the ACCC seeks a compensation order for Mr Ahmed pursuant to s 239(1) of the ACL.

21 The ACCC presses, and Ultra Tune still denies, that Mr Ahmed was misled in the several ways alleged, as summarised at [17(4)] above.

Preliminary observations about the conduct alleged and the relief to be granted

22 As will be seen, the first category of alleged contravention raises troubling questions about how such a substantial franchisor as Ultra Tune was able to get away with making a very poor effort in complying with the minimum disclosure obligations. Those obligations are at the very heart of long-standing franchise code requirements designed to make such arrangements in Australia function fairly and properly. This serves to emphasise the importance of an active and effective regulator, as the ACCC has been in this case, there having been a prompt and ultimately wide-ranging investigation, albeit triggered by Mr Ahmed’s complaint.

23 The second category of alleged contravention raises troubling questions about Ultra Tune’s candour to the ACCC and to this Court. Indeed, the issue of evidence fabrication, or at least document fabrication, which took place to justify retaining the deposit paid by Mr Ahmed, raises further questions that require determination. An important part of Ultra Tune’s original case in defence of the second category of alleged contraventions, since abandoned, was advanced in reliance upon a letter and enclosures that were purportedly sent to Mr Ahmed in early October 2015. As these reasons make clear, that correspondence was a fiction, apparently designed to mislead the ACCC, and initially maintained in this proceeding as being true with the evident purpose of misleading this Court.

24 In making the concession as to its liability to refund Mr Ahmed, Ultra Tune submits that there is no longer any need for findings to be made about issues surrounding the payment of that deposit. However, those documents cannot be ignored merely because they cannot be defended in light of the material inconsistencies that plague them and in light of the issue of fabrication. As the ACCC’s case exposes beyond any reasonable doubt, the impugned documents were created to justify and to conceal Ultra Tune’s reprehensible conduct towards Mr Ahmed. That circumstance is an important consideration in setting the appropriate penalty for civil penalty contraventions that are established, because it informs the attitude of Ultra Tune towards such contraventions, and thus is relevant to the need for specific deterrence and also general deterrence.

25 As will be seen, the concession made by Ultra Tune was in a very limited compass, evidently recognising the inevitable and also seeking to avoid serious adverse findings being made. The concession was as limited in its effect as it was in its scope and had almost no material impact in terms of contrition or remorse, or in reduction of the need for specific or general deterrence in relation to the treatment meted out to a prospective franchisee. However, even late capitulation of this kind must still be acknowledged, and credit be given, to a late recognition, to some degree, of wrong-doing.

The enforcement of industry codes under the CCA

26 Part IVB of the CCA provides for the creation and enforcement of “industry codes”. The purpose of an industry code is to regulate the conduct of participants in an industry toward other participants or consumers in the industry. “Franchising” is included as an industry for the purposes of Part IVB: s 51ACA(3). An applicable industry code may be a voluntary industry code: s 51ACA(1)(b)). It may also be a mandatory industry code, which must be declared to be mandatory by regulation: ss 51ACA(1), 51AE. Both the Pre-2015 Code and the Franchising Code are examples of mandatory industry codes. By reason of what is now s 51ACB (and was formerly s 51AD), a corporation must not, in trade or commerce, contravene an applicable industry code.

27 Under Part IVB of the CCA, the ACCC has been entrusted with various regulatory powers in relation to applicable industry codes. These include the power to issue a public warning notice (s 51ADA), certain investigative powers (Division 5), and the ability to seek orders for redress of a contravention (s 51ADB). From 1 January 2015, the ACCC has also had the power to issue an infringement notice (Division 2A), and the ability to seek the imposition of civil penalties for breach of a civil penalty provision of an applicable industry code (s 76(1)).

The Franchising Code of Conduct – the Pre-2015 Code and current Franchising Code

28 The franchising code of conduct was originally established by regulation in 1998 under the Trade Practices Act. The Trade Practices Act was renamed as the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) on 1 January 2011, with the ACL being added as Schedule 2 at the same time, replacing the former Part V consumer protection provisions. In 2014, an updated version of the code was introduced, to apply from 1 January 2015. The new code was intended to modernise the provisions of the old code and to give effect to proposed reforms that had emerged from an independent review of franchising policy.

29 Broadly speaking, there is a great deal of similarity in the structure of the Franchising Code, and its predecessor, the Pre-2015 Code. The codes share a stated purpose, which is “to regulate the conduct of participants in franchising towards other participants in franchising”: cl 2. The codes also share three general areas of focus, which are to require franchisors to disclose certain information to franchisees, including prospective franchisees, to prescribe minimum standards in franchise agreements, and to provide dispute resolution processes.

30 Each code is divided into four parts. Part 1 contains the introduction to the code, including definitions. Part 2 addresses disclosure requirements before entry into a franchising agreement. Part 3 addresses franchise agreements. Part 4 addresses dispute resolution. The codes also annex prescribed forms for the disclosure documents that are to be given to franchisees and prospective franchisees.

31 The Franchising Code introduced several changes that are of particular bearing to this proceeding. The first is to make the obligations placed on franchisors more prescriptive. The second is the designation of certain clauses as civil penalty provisions. The third is the inclusion of an explicit obligation on the parties to a franchise agreement (or proposed franchise agreement) to act in good faith, which is also a civil penalty provision. This good faith obligation had no equivalent in the old code, save that cl 23A of that code operated to explicitly preserve any obligation to act in good faith that might have arisen under the common law.

32 Provisions reproduced below refer to a civil penalty of 300 penalty units. A penalty unit in 2015, which is when all the contraventions the subject of this proceeding are alleged to have occurred, was $180: see s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). Thus the maximum dollar penalty equivalent to 300 penalty units was $54,000 in 2015. The value of a penalty unit is indexed in accordance with inflation every two years, and will therefore increase over time. The value of a penalty unit was increased to $210 on 1 July 2018 (increasing the maximum penalty from that date to $63,000), and will increase again on 1 July 2020. It is therefore useful to express a penalty that is imposed by reference to penalty units as well as dollar amounts for the purposes of any future comparison and to ensure that, all other things being equal, generally speaking the dollar value of penalties imposed rise with the increase in the value of penalty units, reflecting properly the will of parliament.

33 The relevant provisions of the codes have been set out under the following headings below:

(1) definitions: the meaning of “franchise agreement”;

(2) the obligation to act in good faith;

(3) the obligation to maintain a disclosure document;

(4) the prescribed form and content of a disclosure document;

(5) the obligation to give documents to a franchisee or a prospective franchisee; and

(6) the obligation to provide a copy of financial statements, including marketing fund statements.

(1) Definitions: the meaning of “franchise agreement”

34 An integral term in the operation of both codes is the core contractual concept of a “franchise agreement”, which is defined in cl 4 of the Pre-2015 Code and in cl 5 of the Franchising Code. The differences between the definitions are not significant for present purposes. The Franchising Code provides in cl 5:

(1) A franchise agreement is an agreement:

(a) that takes the form, in whole or part, of any of the following:

(i) a written agreement;

(ii) an oral agreement;

(iii) an implied agreement; and

(b) in which a person (the franchisor) grants to another person (the franchisee) the right to carry on the business of offering, supplying or distributing goods or services in Australia under a system or marketing plan substantially determined, controlled or suggested by the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor; and

(c) under which the operation of the business will be substantially or materially associated with a trade mark, advertising or a commercial symbol:

(i) owned, used or licensed by the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor; or

(ii) specified by the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor; and

(d) under which, before starting or continuing the business, the franchisee must pay or agree to pay to the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor an amount including, for example:

(i) an initial capital investment fee; or

(ii) a payment for goods or services; or

(iii) a fee based on a percentage of gross or net income whether or not called a royalty or franchise service fee; or

(iv) a training fee or training school fee;

but excluding:

(v) payment for goods and services supplied on a genuine wholesale basis; or

(vi) repayment by the franchisee of a loan from the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor; or

(vii) payment for goods taken on consignment and supplied on a genuine wholesale basis; or

(viii) payment of market value for purchase or lease of real property, fixtures, equipment or supplies needed to start business or to continue business under the franchise agreement.

(2) For subclause (1), each of the following is taken to be a franchise agreement:

(a) the transfer or renewal of a franchise agreement;

(b) the extension of the term or the scope of a franchise agreement;

(c) a motor vehicle dealership agreement.

[Sub-section (3) excludes from this definition particular agreements not relevant to this proceeding, such as for an employer and employee relationship.]

(2) The obligation to act in good faith

35 As already mentioned, the Franchising Code introduced an express obligation to act in good faith, which is set out in cl 6 as follows (emphasis in original):

6 Obligation to act in good faith

Obligation to act in good faith

(1) Each party to a franchise agreement must act towards another party with good faith, within the meaning of the unwritten law from time to time, in respect of any matter arising under or in relation to:

(a) the agreement; and

(b) this code.

This is the obligation to act in good faith.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) The obligation to act in good faith also applies to a person who proposes to become a party to a franchise agreement in respect of:

(a) any dealing or dispute relating to the proposed agreement; and

(b) the negotiation of the proposed agreement; and

(c) this code.

Matters to which a court may have regard

(3) Without limiting the matters to which a court may have regard for the purpose of determining whether a party to a franchise agreement has contravened subclause (1), the court may have regard to:

(a) whether the party acted honestly and not arbitrarily; and

(b) whether the party cooperated to achieve the purposes of the agreement.

Franchise agreement cannot limit or exclude the obligation

(4) A franchise agreement must not contain a clause that limits or excludes the obligation to act in good faith, and if it does, the clause is of no effect.

(5) A franchise agreement may not limit or exclude the obligation to act in good faith by applying, adopting or incorporating, with or without modification, the words of another document, as in force at a particular time or as in force from time to time, in the agreement.

Other actions may be taken consistently with the obligation

(6) To avoid doubt, the obligation to act in good faith does not prevent a party to a franchise agreement, or a person who proposes to become such a party, from acting in his, her or its legitimate commercial interests.

(7) If a franchise agreement does not:

(a) give the franchisee an option to renew the agreement; or

(b) allow the franchisee to extend the agreement;

this does not mean that the franchisor has not acted in good faith in negotiating or giving effect to the agreement.

36 This obligation had no equivalent in the Pre-2015 Code, which provided under cl 23A only that:

Nothing in this code limits any obligation imposed by the common law, applicable in a State or Territory, on the parties to a franchise agreement to act in good faith.

(3) The obligation to maintain a disclosure document

37 The codes impose an obligation on a franchisor to maintain a disclosure document. The stated purpose of a disclosure document is the same under both codes: see cl 6A of the Pre-2015 Code and cl 8(2) of the Franchising Code. That purpose is to give a prospective franchisee (or a current franchisee who is considering renewal, variation or extension of an agreement) information that is material to the running of the business and information to help a franchisee or prospective franchisee make a reasonably informed decision about the franchise.

38 Under the Pre-2015 Code, the obligation to create a disclosure document was set out in cl 6 and cl 6B. The substance of the obligation was contained in cl 6(1), which provided:

A franchisor must, before entering into a franchise agreement, and within 4 months after the end of each financial year after entering into a franchise agreement, create a document (a disclosure document) for the franchise in accordance with this Division.

39 The form and content of a disclosure document was prescribed by cl 6(2). If the expected annual turnover of the franchised business was over $50,000, the document was to be prepared in accordance with annexure 1. If the expected annual turnover was $50,000 or less, either annexure 1 or annexure 2 was to be used, the latter being a short form of the disclosure document.

40 Under the Franchising Code, the obligation to maintain a disclosure document is now set out in cl 8. Civil penalties may be imposed in respect of any contravention of cll 8(1), 8(6) or 8(8), which impose obligations to create such a document and update it where required. Clause 8 provides:

8 Franchisor must maintain a disclosure document

Disclosure document to inform franchisee or prospective franchisee

(1) A franchisor must create a document (a disclosure document) relating to a franchise that complies with subclauses (3), (4) and (5).

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) The purpose of a disclosure document is to:

(a) give a prospective franchisee, or a franchisee proposing to:

(i) enter into a franchise agreement; or

(ii) renew a franchise agreement; or

(iii) extend the term or scope of a franchise agreement;

information from the franchisor to help the franchisee to make a reasonably informed decision about the franchise; and

(b) give a franchisee current information from the franchisor that is material to the running of the franchised business.

Content and form of disclosure document

(3) Information in a disclosure document must:

(a) comply with the following:

(i) be set out in the form and order of Annexure 1;

(ii) use the headings and numbering of Annexure 1;

(iii) if applicable—include additional information under the heading “Updates”; or

(b) comply with the following:

(i) if particular items are applicable—use the headings and numbering of Annexure 1 for those items;

(ii) if particular items are not applicable—include an attachment that sets out the headings and numbering of Annexure 1 for those items.

(4) A disclosure document must be signed by the franchisor, or a director, officer or authorised agent of the franchisor.

(5) A disclosure document must also have a table of contents based on the items in Annexure 1, indicating the page number on which each item begins. If the disclosure document attaches other documents, the table of contents must list these other documents too.

Maintaining a disclosure document

(6) After entering into a franchise agreement, the franchisor must update the disclosure document within 4 months after the end of each financial year.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(7) However, the franchisor need not update the disclosure document after the end of a financial year if:

(a) the franchisor did not enter into a franchise agreement, or only entered into 1 franchise agreement, during the year; and

(b) the franchisor does not intend, or if the franchisor is a company, its directors do not intend, to enter into another franchise agreement in the following financial year.

(8) Despite subclause (7), if a request is made under subclause 16(1), the franchisor must update the disclosure document so that it reflects the position of the franchise as at the end of the financial year before the financial year in which the request is made.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

41 Unless requested by a franchisee, cl 8(7) permits a franchisor not to update a disclosure document where the franchisor entered into only one franchise agreement, or none, and does not intend to enter into another franchise agreement in the following financial year.

42 The franchise design implemented by Ultra Tune operated on a State-based franchise model with four separate disclosure documents. As outlined above at [15], Ultra Tune increased its number of franchisees in the relevant years overall, but not in all years in respect of all States. No increase in franchise numbers for a given State, or only an increase of one franchise for a given State, in a given year would trigger the first limb of the cl 8(7) exception to the cl 8(6) obligation to update a disclosure document for the following year: see [40] above. However, there was no evidence of any absence of intention on the part of Ultra Tune to enter into another franchise agreement for any of the years in question either across all of the States, or in respect of any individual State, so as to trigger the second limb of the cl 8(7) exception. The cl 8(7) is therefore not relevant to the current proceeding.

(4) The prescribed form and content of a disclosure document

43 Both of the codes include forms at Annexure 1 for the primary disclosure document to be given to franchisees or prospective franchisees. There are some differences between the two versions of the disclosure document that are not presently material.

44 The information to be set out in the disclosure document is in large part dictated by the items specified in Annexure 1 in some considerable detail. In the case of the Franchising Code, this includes:

a covering page, which sets out a pro forma description of the document and its legal effect (item 1);

franchisor details (item 2);

details of the business experience of the franchisor and its officers (item 3);

details of past and present litigation involving the franchisor, as well as details of judgments and convictions against the franchisor or its directors (item 4);

details of any agreement under which the franchisor must pay or give other valuable consideration to agents in connection with the introduction or recruitment of a franchisee (item 5);

details of existing franchises (item 6);

details regarding a master franchisor, where applicable (item 7);

details of intellectual property that is material to the franchise system (item 8);

details of the franchise site or territory (item 9), as well as a history of previous franchised businesses that have been operated on the site in the previous 10 years (item 13);

details regarding the supply of goods or services to a franchisee (item 10), by a franchisee (item 11) and online (item 12);

details and explanations of payments that are required before the entry into a franchise agreement (item 14);

details of any marketing or other cooperative fund controlled by the franchisor (item 15);

details regarding financing arrangements offered by the franchisor (item 16);

details regarding unilateral variations of the franchise agreement by the franchisor (item 17);

details regarding the end of a franchise agreement (item 18);

details regarding any amendment of the agreement where the franchise is transferred (item 19);

earnings information for the franchised business (item 20);

financial details for the franchisor (item 21), which must be updated to reflect any changes from the date of the disclosure document and the date that the document is given as required per the Franchising Code (item 22); and

a final page, which notes that the prospective franchisee may retain the document, and a form for the prospective franchisee to acknowledge receipt of the disclosure document (item 23).

45 Several items require more detailed reproduction for the purpose of these reasons. Relevantly, item 13 relates to details of previous franchises that may have operated at a particular site. It states:

…

13.2 Details of whether the territory or site to be franchised has, in the previous 10 years, been subject to a franchised business operated by a previous franchise granted by the franchisor and, if so, details of the franchised business, including the circumstances in which the previous franchisee ceased to operate.

13.3 The details mentioned in item 13.2 must be provided:

(a) in a separate document; and

(b) with the disclosure document.

Thus this franchise-specific information is required to be provided in a separate document with the disclosure document, but is not itself part of the disclosure document.

46 Item 14 relates to payments involved in a franchise agreement. It relevantly provides:

Prepayments

14.1 If the franchisor requires a payment before the franchise agreement is entered into—why the money is required, how the money is to be applied and who will hold the money.

14.2 The conditions under which a payment will be refunded.

…

47 Item 20 relates to disclosure of earnings information. It relevantly states (emphasis in original):

20.1 Earnings information may be given in a separate document attached to the disclosure document.

20.2 [An inclusive definition of earnings information]

20.3 If earnings information is not given—the following statement:

The franchisor does not give earnings information about a [insert type of franchise] franchise.

Earnings may vary between franchises.

The franchisor cannot estimate earnings for a particular franchise.

20.4 [Details to be provided for any projection or forecast of earnings information]

Thus, this franchise-specific information can be provided in a separate document attached to the disclosure document, in which case it is not itself part of the disclosure document.

48 The disclosure document requirements outlined above enable a franchisor, depending on the design of its franchising arrangements, to deploy a document that is generic for all franchisees, or for a particular group of franchisees, rather than by having a document that is separate and distinct for each individual franchisee. Based on the disclosure document given to Mr Ahmed, it is apparent that Ultra Tune chose to design a generic disclosure document for each of its four State-based franchise regions, combining for that purpose the metropolitan and regional franchises in NSW. As will be seen, that has a material impact on the number of contraventions that take place when it comes to obligations to create and to maintain a disclosure document, but does not affect the number of contraventions when it comes to the obligation to provide a disclosure document to each franchisee, which is considered next.

(5) The obligation to give a disclosure document (and other documents) to a franchisee or a prospective franchisee

49 The codes impose obligations on a franchisor to give the disclosure document to a prospective franchisee.

50 Under the Pre-2015 Code, cl 6B relevantly provided:

6B Requirement to give disclosure document

(1) A franchisor must give a current disclosure document to:

(a) a prospective franchisee; or

(b) a franchisee, if the franchisor or the franchisee proposes to renew, extend, or extend the scope of the franchise agreement.

…

51 A franchisor was also required to give a franchisee a current disclosure document within 14 days after a written request by the franchisee. Clause 19 provided:

19 Current disclosure document

(1) A franchisor must give to a franchisee a current disclosure document within 14 days after a written request by the franchisee.

(2) However, a request under subclause (1) can be made only once in 12 months.

52 Under the Franchising Code, the obligation to give documents to a prospective franchisee is now set out in cl 9, which provides:

9 Franchisor to give documents to a franchisee or prospective franchisee

(1) A franchisor must give:

(a) a copy of this code; and

(b) a copy of the disclosure document:

(i) as updated under subclause 8(6); or

(ii) if subclause 8(7) applies—updated to reflect the position of the franchise as at the end of the financial year before the financial year in which the copy of the disclosure document is given; and

(c) a copy of the franchise agreement, in the form in which it is to be executed;

to a prospective franchisee at least 14 days before the prospective franchisee:

(d) enters into a franchise agreement or an agreement to enter into a franchise agreement; or

(e) makes a non-refundable payment (whether of money or of other valuable consideration) to the franchisor or an associate of the franchisor in connection with the proposed franchise agreement.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) If a franchisor or franchisee proposes to:

(a) renew a franchise agreement; or

(b) extend the term or scope of a franchise agreement;

the franchisor must give to a franchisee (within the meaning of paragraph (a) of the definition of that expression) the documents mentioned in subclause (1) at least 14 days before renewal or extension of the franchise agreement.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(3) A franchisor is taken to have complied with the requirements of this clause even if, during the relevant 14-day or longer period, changes are made to a franchise agreement:

(a) to give effect to a franchisee’s request; or

(b) to fill in required particulars; or

(c) to reflect changes of address or other circumstances; or

(d) for clarification of a minor nature; or

(e) to correct errors or references.

53 Clause 10 of the Franchising Code requires that a franchisor not enter into a franchise agreement unless they have received written statements from the franchisee or prospective franchisee that they have received, read and had a reasonable opportunity to understand the disclosure document and the code, and have been given advice from an independent legal adviser, independent business adviser or an independent accountant. The protective purpose of this requirement is obvious, yet it was not observed by Ultra Tune in relation to Mr Ahmed prior to accepting what Ultra Tune would for a time contend to be a non-refundable payment.

54 Under the Franchising Code, a franchisor is also required to give to a franchisee a disclosure document upon receiving a written request. Clause 16 provides:

(1) Upon receiving a written request from a franchisee, a franchisor must give to the franchisee a disclosure document:

(a) if subclause 8(8) applies—within 2 months of the date of the request; and

(b) in any other case—within 14 days of the date of the request.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) However, a request under subclause (1) can be made only once every 12 months.

As noted above at [42], cl 8(7) does not apply, such that cl 8(8) is not enlivened, and therefore cl 16(1)(b), rather than cl 16(1)(a), is applicable to Ultra Tune.

(6) The obligation to provide a copy of financial statements, including marketing fund statements

55 The codes contain obligations on the part of franchisors to provide copies of certain financial statements to franchisees if they have been required to pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund. Ultra Tune required all of its franchisees to pay money to a marketing fund, with separate funds for each State-based franchise region, except NSW which has a separate fund for metropolitan NSW and regional NSW, making a total of five marketing funds. The following provisions required financial statements to be prepared within four months of the end of each financial year and for the statements to be audited, unless (not applicable on the evidence in this case) 75% of franchisees contributing to the fund voted not to require auditing within three months after the end of the financial year. The financial statements were then to be provided, along with the auditor’s report (if applicable), to each franchisee within 30 days of preparation. There is no evidence of any such agreement by the Ultra Tune franchisees.

56 Under the Pre-2015 Code, the obligations were set out in cl 17, which provided:

17 Marketing and other cooperative funds

(1) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the franchisor must:

(a) within 4 months after the end of the last financial year, prepare an annual financial statement detailing all of the fund’s receipts and expenses for the last financial year; and

(b) have the statement audited by a registered company auditor within 4 months after the end of the financial year to which it relates; and

(c) give to the franchisee:

(i) a copy of the statement, within 30 days of preparing the statement; and

(ii) a copy of the auditor’s report, if such a report is required, within 30 days of preparing the report.

(2) A franchisor does not have to comply with paragraph (1)(b) for a financial year if:

(a) 75% of the franchisor’s franchisees in Australia, who contribute to the fund, have voted to agree that the franchisor does not have to comply with the paragraph; and

(b) that agreement is made within 3 months after the end of the financial year.

(3) The agreement referred to in paragraph (2)(a) will remain in force for 3 years, and franchisees must vote, at the end of that time, in accordance with paragraph (2) (a), for the agreement to remain in force.

(4) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the reasonable costs of administering and auditing the fund must be paid from the fund.

57 Under the Franchising Code, these obligations are now contained in cl 15. It relevantly provides:

15 Copy of financial statements

(1) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the franchisor must:

(a) within 4 months after the end of the last financial year, prepare an annual financial statement detailing all of the fund’s receipts and expenses for the last financial year; and

(b) ensure that the statement includes sufficient detail of the fund’s receipts and expenses so as to give meaningful information about:

(i) sources of income; and

(ii) items of expenditure, particularly with respect to advertising and marketing expenditure; and

(c) have the statement audited by a registered company auditor within 4 months after the end of the financial year to which it relates; and

(d) give to the franchisee:

(i) a copy of the statement, within 30 days of preparing the statement; and

(ii) a copy of the auditor’s report, if such a report is required, within 30 days of preparing the report.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) A franchisor does not have to comply with paragraph (1)(c) in respect of a financial year if:

(a) 75% of the franchisor’s franchisees in Australia, who contribute to the fund, have voted to agree that the franchisor does not have to comply with the paragraph in respect of the financial year; and

(b) that agreement is made within 3 months after the end of the financial year.

(3) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the reasonable costs of administering and auditing the fund must be paid from the fund.

The Australian Consumer Law (ACL)

58 The ACCC also advances part of its case under the ACL. The relevant provisions need to be briefly identified.

59 Section 18 of the ACL, formerly s 52 of the Trade Practices Act, provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. No pecuniary penalty attaches to a breach of s 18 of the ACL.

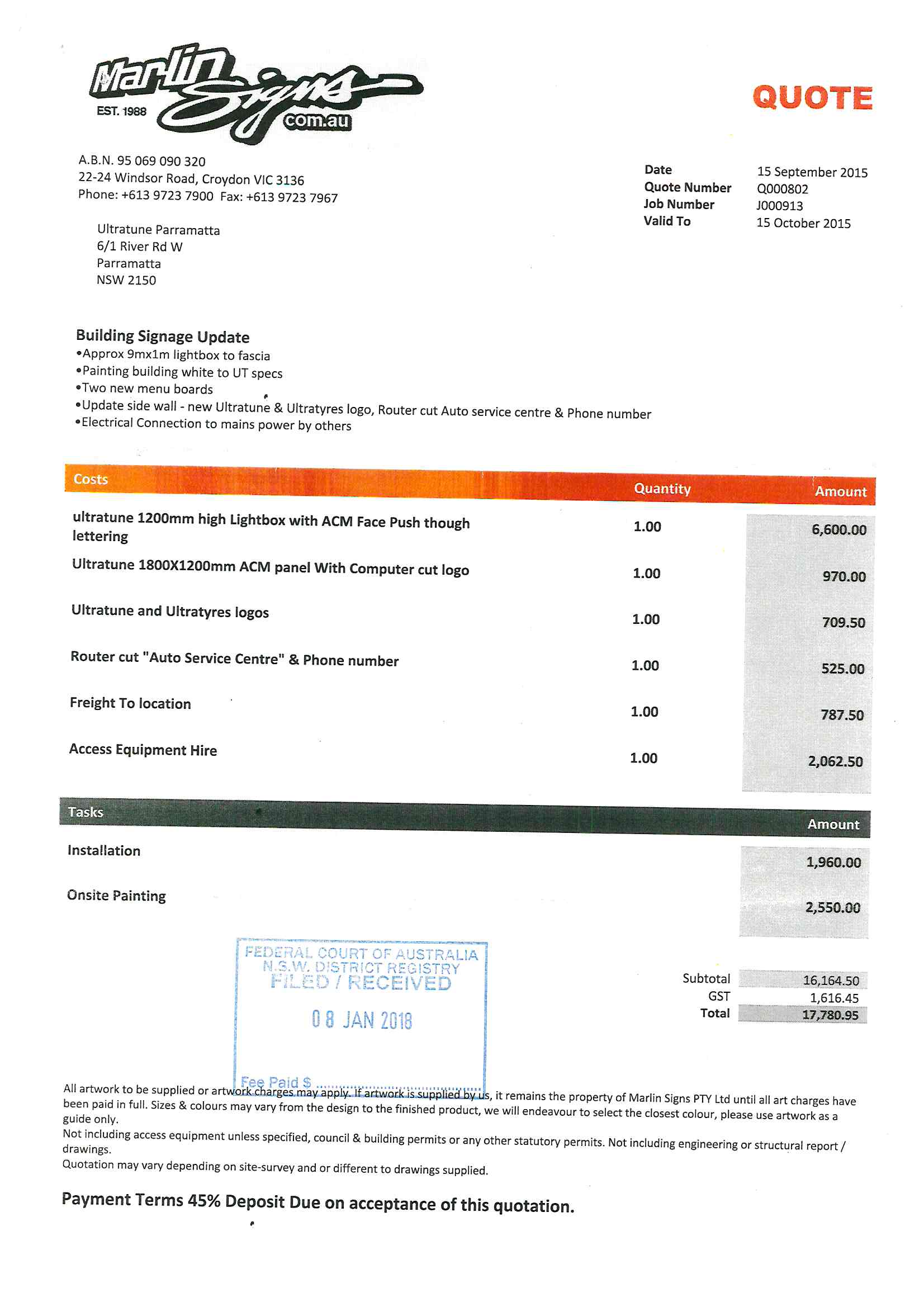

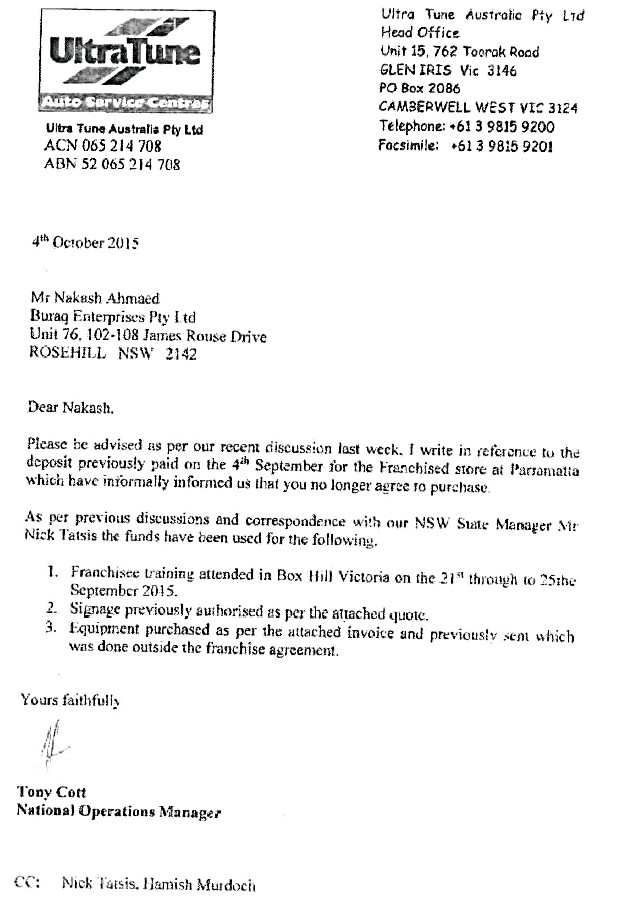

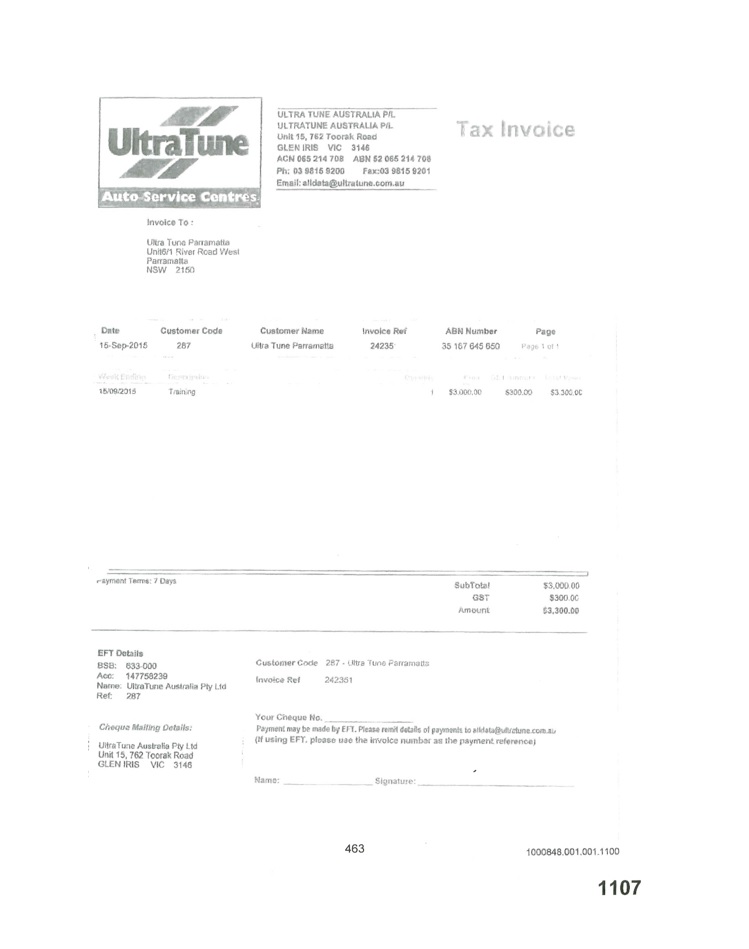

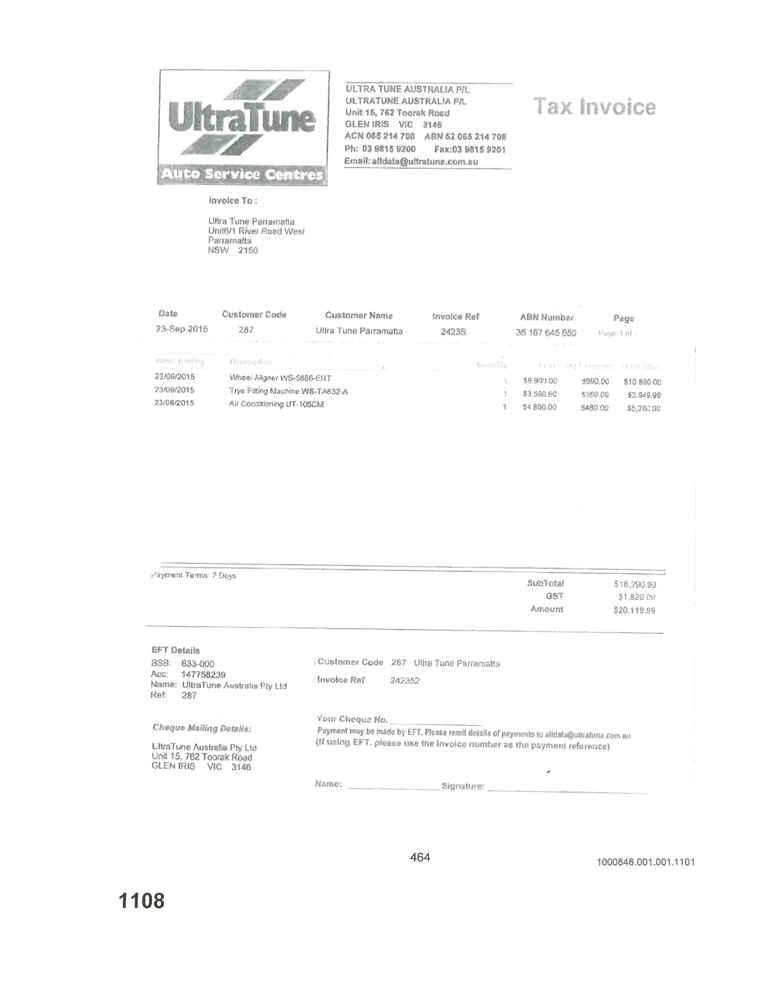

60 Section 29 of the ACL proscribes the making of false or misleading representations about goods or services. It relevantly provides:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services; or

…

(m) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3-2); …

…

61 At the time of the alleged contraventions, item 2 in the table in s 224(3) of the ACL provided that each act or omission proscribed by a provision in Part 3-1 of the ACL, which includes s 29, carried a maximum penalty of $1.1 million for a company and $220,000 for an individual. Had this been expressed as penalty units at the time, it would have been just over 6,100 penalty units for a company and just over 1,200 penalty units for an individual, a considerably greater maximum than for contraventions of the provisions of the Franchising Code reproduced above of 300 penalty units.

62 By virtue of s 239(1), the Court may make orders for redress of a contravention of s 29 of the ACL, making such orders against the contravener as it considers appropriate.

THE ADMITTED DISCLOSURE CONTRAVENTIONS

63 By way of an amended concise statement in response, Ultra Tune largely admits to the alleged disclosure contraventions of the Pre-2015 Code and the Franchising Code. The admitted contraventions are set out below. Those admissions have been extended by Ultra Tune’s closing submissions, both in writing and orally, which abandon the defence to a portion of the allegations concerning Mr Ahmed.

64 It should be noted that, in relation to the admitted breaches of cll 8(6), 15(1)(a) and 15(1)(d) of the Franchising Code, Ultra Tune resists the ACCC’s submission that each act or omission constitutes a separate contravention in relation to each franchisee. According to Ultra Tune, the obligations contained in those clauses each refer to what may be described as “one transaction” for the franchisor generally. For example, Ultra Tune submits that the obligation to update its disclosure documents under cl 8(6) arises only once per financial year, and not in relation to each franchisee. The parties therefore agree that contraventions have taken place, but disagree as to the number of contraventions that have occurred.

65 At this point, it is convenient to note again the table at [15] above which shows how Ultra Tune divides its operations into five geographical regions: Victoria, NSW Metro, NSW Country, Queensland and Western Australia (Ultra Tune regions). It is the ACCC’s fall-back position that, at the very least, Ultra Tune must be taken to have engaged in a separate contravention of cll 8(6), 15(1)(a) and 15(1)(d) for each of those five Ultra Tune regions. In its closing address and supplementary submissions, Ultra Tune maintained its position that there was only one transaction for the breaches that it admitted to.

66 The issue of the number of contraventions will be returned to when considering the relief that should be granted.

67 Ultra Tune admits to having breached the Pre-2015 Code in the following three respects.

68 While none of breaches under the Pre-2015 Code described below give rise to any liability for a pecuniary penalty, they are none-the-less relevant to the later contraventions of the Franchising Code, which did attract such a liability. That is because they enable the Court to view the later contraventions admitted or found to have taken place as not being, for example, out of character: see, by analogy, Veen (No 2) v The Queen (1988) 164 CLR 465 at 477-8. These earlier contraventions therefore additionally operate as a prism through which to view the later contraventions. However, care must be taken to ensure that the penalty is proportionate to the instant contravention and that no element of the pecuniary penalty imposed for later contraventions is reflective of any sanction for these earlier contraventions: see Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (The Non-Indemnification Personal Payment Case) [2018] FCAFC 97 at [22].

Preparing annual financial statements

69 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 17(1)(a) of the Pre-2015 Code, it failed to prepare annual financial statements within four months of the end of the 2011-12 and 2012-13 financial years:

(1) for the 2011-12 financial year (the statement having been completed on 30 November 2012, instead of by 31 October 2012); and

(3) for the 2012-13 financial year (the statement having been completed on 28 November 2013, instead of by 31 October 2013).

Providing annual financial statements

70 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 17(1)(c) of the Pre-2015 Code, it did not provide annual financial statements and auditor’s reports to any franchisee as required to be done within 30 days of preparation:

(1) for the 2011-12 financial year;

(2) for the 2012-13 financial year; and

(3) for the 2013-14 financial year,

no such documents having been provided at all.

Creating a disclosure document

71 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 6(1) of the Pre-2015 Code, it failed to create a disclosure document within four months after the end of the 2014-15 financial year, that document having been completed on 5 December 2014 instead of by 31 October 2014.

Breaches of the Franchising Code

72 For the 2014-15 and 2015-16 financial years, Ultra Tune was required by cl 15 of the Franchising Code to prepare, have audited, and distribute certain annual financial statements if a franchisee was required to pay money into a marketing fund. Ultra Tune was also required by cl 8(6) to update its disclosure document and to provide that disclosure document when requested by a franchisee per cl 16(1)(b). Ultra Tune admits to having breached the Franchising Code in the following four respects, and thus to being liable to pay pecuniary penalties for those contraventions.

73 On any view, the admitted disclosure contraventions of the Franchising Code described below were substantial, and in the case of the more lengthy delays described were of a relatively high level of objective seriousness when due regard is had to the reason why these requirements exist in the first place and the extent of the non-compliance. The later the provision of such information, the less use it is and the closer it comes to not providing it at all. Such requirements are now able to be deterred by the sanction of substantial pecuniary penalties, taking into account the number of franchisees affected in relation to information that was not provided to them as required.

Preparing annual financial statements for marketing funds

74 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 15(1)(a) of the Franchising Code, it failed to prepare marketing fund statements within four months after the end of the last financial year for the 2014-15 financial year (that document having been completed on 24 December 2015 instead of by 31 October 2015).

Providing annual financial statements for marketing funds to franchisees

75 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 15(1)(d) of the Franchising Code, it did not provide to franchisees the annual financial reports and auditor’s reports for the marketing funds for the 2014-15 financial year within 30 days of their preparation. Those reports had been completed on 24 December 2015, so were required to be provided to each franchisee who was required to contribute to the marketing funds (which was all franchisees) by 24 January 2016. Ultra Tune says that these documents were instead provided as follows:

(1) the annual financial statement and auditor’s report for the Queensland region was provided to two Queensland franchisees on 28 January 2016;

(2) the annual financial statement and auditor’s report were provided to a single NSW franchisee on 29 January 2016, following a specific request by that franchisee; and

(3) the annual financial statement and auditor’s report for each region was provided to the other 182 franchisees for the 2014-15 financial year on 11 August 2016, over seven months after they were created rather than within the necessary 30 days, and therefore over six months late.

Updating the disclosure document

76 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 8(6) of the Franchising Code, it did not update its disclosure documents for the 2015-16 financial year within four months after the end of the 2014-15 financial year, being 31 October 2015. Those documents were not completed until 26 February 2016, so were almost four months late, taking almost twice as long as required.

Providing the disclosure document

77 Ultra Tune admits that, contrary to cl 16(1)(b), it did not provide a disclosure document to a franchisee in Morayfield within 14 days of a request made on 16 December 2015, that document having not been provided until 23 March 2016, over three months after the request was made.

THE DISPUTED DISCLOSURE CONTRAVENTIONS

Preparation of marketing fund statements

78 In accordance with cl 15(1) of the Franchising Code, the statements for the 2014-15 and 2015-16 financial years were required to detail all of the relevant marketing fund’s receipts and expenses for the previous financial year. Given that Ultra Tune maintained a separate marketing fund for each of the five Ultra Tune regions listed in the table at [15] above, it was required to prepare annual statements for each of those funds. It is not in dispute that for both financial years:

(1) Ultra Tune did so in the form of a profit and loss statement for each region’s fund;

(2) had the statements audited; and

(3) provided the statements and auditor’s reports to the franchisees.

79 What is controversial, however, is the adequacy of those statements in terms of meeting the standard required by the Franchising Code. In respect of both financial years, the ACCC alleges that the financial statements that were prepared by Ultra Tune did not have “sufficient detail” as specifically required by cl 15(1)(b) of the Franchising Code. Ultra Tune disputes this.

80 Clause 15 of the Franchising Code below provides (emphasis added):

15 Copy of financial statements

(1) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the franchisor must:

(a) within 4 months after the end of the last financial year, prepare an annual financial statement detailing all of the fund’s receipts and expenses for the last financial year; and

(b) ensure that the statement includes sufficient detail of the fund’s receipts and expenses so as to give meaningful information about:

(i) sources of income; and

(ii) items of expenditure, particularly with respect to advertising and marketing expenditure; and

(c) have the statement audited by a registered company auditor within 4 months after the end of the financial year to which it relates; and

(d) give to the franchisee:

(i) a copy of the statement, within 30 days of preparing the statement; and

(ii) a copy of the auditor’s report, if such a report is required, within 30 days of preparing the report.

Civil penalty: 300 penalty units [$54,000].

(2) A franchisor does not have to comply with paragraph (1)(c) in respect of a financial year if:

(a) 75% of the franchisor’s franchisees in Australia, who contribute to the fund, have voted to agree that the franchisor does not have to comply with the paragraph in respect of the financial year; and

(b) that agreement is made within 3 months after the end of the financial year.

(3) If a franchise agreement provides that a franchisee must pay money to a marketing or other cooperative fund, the reasonable costs of administering and auditing the fund must be paid from the fund.

81 The question of construction that arises is as to the proper meaning of the expression “sufficient detail” in cl 15(1)(b). This has not been the subject of any previous authority that I have been able to detect or that the parties have raised.

82 It is important to also note that cl 15(1) is evidently related to cl 31, which imposes direct requirements on how marketing fees are to be used. This provides an important contextual basis for understanding a key practical use of the information that is required to be disclosed, informing what information needs to be included to be useful and to achieve the regulatory purpose. Of particular relevance is cl 31(3), which provides:

Despite any terms of a franchise agreement, marketing fees or advertising fees may only be used to:

(a) meet expenses that:

(i) have been disclosed to franchisees under paragraph 15.1(f) of the disclosure document; or

(ii) are legitimate marketing or advertising expenses; or

(iii) have been agreed to by a majority of franchisees; or

(b) pay the reasonable costs of administering and auditing a marketing fund.

83 Ultra Tune prepared its financial statements for both the 2014-15 and 2015-16 financial years for the purposes of cl 15(1) in the form of profit and loss statements for each Ultra Tune region. Those statements were uniform in structure. Each took the form of an ordinary balance sheet, with a limited number of line items listed as either “income” or “expenses” together with dollar figures and percentages reflecting each item’s proportion of the overall expenditure. For the most part, the total income of each fund for the 2014-15 financial year was in the order of $6.7 million, with a similar expenditure. The 2015-16 financial year also had similar levels of income and expenditure.

84 Included as expenses in the financial statements were a large number of minor items that generally did not account for more than 20% of the total expenditure of the funds in question. These included items described as “Gift Vouchers”, “Printing & Stationary” (sic), “Seminars and Meetings”, “Administration Fees”, “Fleet Administration” and “Customer Support”. In the case of each financial statement, the majority of the relevant fund’s expenditure was constituted by a single item, which was described simply as “Promotion & Advertising – Television”. For example, in the case of the NSW Metro marketing fund for the financial year 2014-15, this item comprises 76.65% of the total expenditure of the fund.

85 Ultra Tune defends the adequacy of its financial statements, which it says are sufficiently detailed for the purposes of cl 15(1)(b). It says that the reference to “meaningful information” in cl 15(1)(b) does no more than emphasise that what is required is an accounting, not a bookkeeping, exercise. It is said to be sufficient that the figures in each financial statement are classified and recorded such that a franchisee can see what the major sources of income and expenses were. According to Ultra Tune, that is exactly what its statements do. I do not accept these submissions.

86 It may be seen from its terms, and its relationship with cl 31(3), that cl 15(1) seeks to promote transparency and accountability in the way that marketing fees are used by a franchisor. It does so by requiring a franchisor to disclose “sufficient detail” of a fund’s receipts and expenses so as to give “meaningful information” to the franchisees about sources of income and items of expenditure, particularly with respect to advertising and marketing expenditure. The ACCC submits that the notion of “meaningful information” conveys at a textual level that the financial statement must have some explanatory force and permit meaningful insights to be gained by the franchisee. I agree.

87 The minimal requirement that Ultra Tune submits is enough would have the effect of denying any real, practical content to the express requirement to give “sufficient detail of the fund’s receipts and expenses so as to give meaningful information” about “sources of income” and “items of expenditure, particularly with respect to advertising and marketing expenditure”. What is required to be provided is sufficiently detailed meaningful information, which is necessarily information that is useful and practical, not merely minimal accounting information.

88 That said, it should be acknowledged that cl 15(1)(b) is not particularly clear or prescriptive as to what is required to give “meaningful information” about a marketing fund’s income and expenditure. However, the general intention of the provision is plain enough, namely that the franchisee should be in a position to know what the income and expenses of the fund are for the purpose of making some meaningful assessment of whether that use is appropriate. The references to “sufficient detail” and “meaningful information” must be understood with that purpose in mind.

89 To be more prescriptive might have reduced the capacity for franchisors to tailor the information provided to a wide range of different circumstances, given the diverse range of economic activities in which franchise arrangements exist. To accommodate those different circumstances, cl 15(1)(b) has a protean quality. What is sufficient detail to give “meaningful information” on a fund’s income and expenditure will vary from case to case. Similarly, what may be a sufficient level of detail for certain items or categories of expenditure may be insufficient for others, bearing in mind also that cl 15(1)(b)(ii) necessarily requires a focus “particularly with respect to advertising and marketing expenditure”. As a general proposition, the more significant an expense is, the more important it will be to a franchisee, and therefore the greater the level of detail that will be required to facilitate an informed assessment by the franchisees concerned. There may be cases in which more detail is needed for a lesser expenditure in order to understand why it is appropriate. In each case, however, the adequacy of the statement must be considered and assessed as a whole.

90 The parties made reference to extrinsic material that was said to aid in construction of cl 15(1)(b). Such material, however, must also be approached with caution to the extent that Parliament may have made “aspirational” statements of its intentions that are not reflected in the terms of the Franchising Code. As emphasised by Spigelman CJ in R v JS [2007] NSWCCA 272; 230 FLR 276 at [142], the task of the courts is to determine what Parliament meant by the words it used; it is not to determine what Parliament intended to say.

91 Here, the extrinsic materials do not go further than confirming that the purpose of the provision is to provide accountability and transparency in the use – and potential misuse, or even inappropriate or ineffectual use – of marketing funds. For instance:

(1) it is recommended in the Review of the Franchising Code of Conduct (30 April 2013), by the author, Mr Wein, that the franchising code of conduct be amended based on the principles that:

(a) a franchisor should separately account for marketing and advertising costs; and

(b) the marketing and advertising fund should only be used for expenses which are clearly disclosed to franchisees; and

(2) it is stated in The Future of Franchising, a publication by the Australian Government in April 2014, that the government would “introduce greater transparency for the way in which marketing funds are used and accounted for [including] requiring additional disclosure on the types of expenses marketing funds are being used for”.

92 Turning to the present case, it should be noted that, putting to one side questions of the level of detail required by cl 15(1)(b), there is nothing inherently deficient about the structure of the profit and loss statements prepared by Ultra Tune. Although the structure will always be generally relevant to the question of whether information is presented in a meaningful way, the issue here is with content and the provision of information that makes sense to an ordinary reader. Franchisees are not to be taken, just because they are running a business, as having accounting expertise or the like. It is they, not their accountants, who must be placed in a position to understand how marketing funds are being deployed and to form a view as to whether the expenditure is appropriate. It is the ordinary franchisee who must be armed with information that has the necessary qualitative character.

93 Ultra Tune notes in written submissions that the term “annual financial statement” at cl 15(1)(a) is not defined in the Franchising Code or the CCA, but is well known to accountants, auditors and businesses generally, comprising a profit and loss statement and balance sheet. Ultra Tune further submits that if additional information was required as contended by the ACCC, no profit and loss statement or balance sheet would comply with the requirement, and it would “turn into something that no longer was an annual financial statement as … understood by accountants, auditors and businesses.” This argument cannot be accepted, as it places undue emphasis on the form of what the statement would take, according to what is submitted to be an industry-accepted standard, above the express substantive requirements of cl 15(1)(b) as to what is required by way of sufficiency of detail.

94 For a number of the minor items, such as “Accounting Fees” and “Bank Charges”, there may not be any great issue with how the items have been described. In this case, this is mainly because there is some degree of granularity in the description of the items, and it is doubtful that further detail would bring any great explanatory force to the statement. Moreover, they may well be relatively fixed expenses with little room for reduction or change and therefore real doubt as to whether or not they were, for example, per cl 31(3)(a)(ii) “legitimate marketing or advertising expenses”.

95 I do not have enough evidence or other information to accept the suggestion by the ACCC that Ultra Tune’s marketing statements were deficient to the extent that they did not explain how the minor items relate to marketing. Indeed, cl 15(1) appears to contemplate that not all of the expenditure of the fund may be on marketing per se, given that it requires a particular focus on items that do. Moreover, it may be inferred that there would or could be accounting fees and bank charges associated with running a marketing fund.

96 The line item for customer support is more cryptic, and might well also be inadequate. However, it is not necessary to decide that in this case because it is sufficient in present circumstances to focus on the central issue of how the lion’s share of expenditure was described. In other cases, and indeed in future for Ultra Tune, such a sparse description might warrant closer attention.

97 The substantial deficiency of Ultra Tune’s marketing fund statements lies in how the preponderance of the funds’ expenditure has been itemised. As described above, the most significant expense is identified simply as “Promotion & Advertising – Television”. Ultra Tune submitted that the line item descriptions made it plain that the “vast bulk of the money spent … was on television advertising”. The problem with describing that expense in such bare and general terms is that, notwithstanding that there might be some granularity in the description of a large number of minor expenses, the statements provide no meaningful information about how most of the fund has in fact been used. It certainly does not provide sufficient detail so as to give meaningful information about advertising and marketing expenditure as expressly required by cl 15(1)(b)(ii).

98 Put another way, where it is indicated that approximately 80% of a fund has been applied to something as non-specific as “Promotion & Advertising – Television”, the statement does little more than suggest, in a circular fashion, that Ultra Tune spent the majority of the marketing fund on marketing. This is plainly inadequate for the purposes of cl 15(1)(b)(ii), and certainly would not assist in ascertaining whether the money was expended on “legitimate marketing or advertising expenses”. In these circumstances, a franchisee would have very limited information to inform its understanding of the item. To whom have the fees been paid? What services were obtained, and when? Almost any other questions cannot even be posed, let alone answered, yet it is plain enough that the intent of cl 15(1)(b) is that franchisees be placed in a position whereby they can assess and question how the money they, along with all other contributing franchisees, have provided, has been spent. The information provided is not just lacking the quality of providing “meaningful information”; it has the active quality of providing largely meaningless information except as to raw quantum, begging the question as to what the money was spent on, and how and when. None of the franchisees could have made any useful assessment as to the appropriateness of this item of expenditure based on the financial statement provided by Ultra Tune.

99 In submissions, Ultra Tune notes that franchisees receive “InTune”, an in-house newsletter, which includes references to the franchise’s advertising and marketing. Ultra Tune also notes, in opening written submissions, that franchisees would be aware of how the marketing fund was spent by virtue of the television advertising being national and on the internet. Although the terms “sufficient detail” and “meaningful information” are subjective, and franchisees may otherwise be aware of specific advertising campaigns, it is clear from the text of cl 15(1)(b) that sufficient detail must be included in the financial statement itself, without recourse being had to other materials, perhaps aided by what might appear in an auditor’s report.

100 Ultra Tune also submits that the nature of the adverse findings sought by the ACCC meant that the quality of evidence required to arrive at reasonable satisfaction that the civil standard of proof has been established was that dictated by the reasoning of Dixon J in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 360-2, now reflected in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). However, that submission does not seem to engage with the live issue here as to the objective requirements attaching to the document that Ultra Tune was required to create, maintain and furnish to franchisees, with the documents that were in fact so produced being in evidence. To the extent that serious allegations require a reasonable quality of evidence, rather than “inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences”, Ultra Tune has not identified any evidentiary shortcoming.

101 I reject Ultra Tune’s submissions referred to above, and more generally. They simply do not grapple with the requirement imposed by cl 15(1)(b) when read with cl 31(3). It follows that I do not accept that Ultra Tune’s financial statements for the 2014-15 and 2015-16 financial years came even close to meeting the requirements of cl 15(1)(b). I therefore find that those contraventions have been easily established.

102 Ultra Tune’s suggestion that if an adverse finding was made, “the fact that this is the first case on this provision and that its approach has been one that in terms of the provisions, is one that was open to it, are matters relevant to the amount of any pecuniary penalty” must be rejected for several reasons. First and foremost, I do not accept that Ultra Tune’s approach was reasonably open to it. Further, Ultra Tune failed to change its practices and approach with the introduction of the Franchising Code on 1 January 2015, despite being a large national company with a large scale franchise business. Sophisticated legal advice was not required to understand that its stance was untenable.

103 In all the circumstances, this was a serious shortcoming and, especially for a large franchisor spending such a large sum of money in a marketing fund, a serious contravention. It was a deficiency for which Ultra Tune provided no real explanation beyond a denial of the manifest inadequacy of what was provided. That stubborn approach calls for a significant deterrent penalty, to encourage future and ongoing compliance by Ultra Tune, as well as franchisors more generally who might otherwise be tempted to skimp on the information provided to their franchisees. To do otherwise would be to countenance ignoring the clear policy objectives of the Franchising Code by making this a hollow requirement, able to be treated in as cavalier a way as Ultra Tune has done.

104 A franchisor may be well advised to err on the side of candour, rather than secrecy, or take the risk of expensive adverse consequences and significant reputational harm. Candour is wise in any event, because it inevitably helps to build trust with franchisees, which in turn is likely to facilitate advancing their mutual interests. The use to which a marketing fund is put can and should easily be the subject of meaningful disclosure to franchisees so that they can properly assess how the money they have been required to contribute has been spent.

ULTRA TUNE’s DEALINGS WITH MR AHMED

105 This aspect of the dispute concerns Ultra Tune’s dealings with a prospective franchisee, Mr Ahmed, who the ACCC asserts was misled in the course of negotiations about a franchise in Parramatta and then refused the refund of the deposit that he sought when, on his evidence, he discovered the truth. As indicated above, the allegations concerning Mr Ahmed were strongly contested by Ultra Tune at the trial. Ultra Tune made key, but not complete, concessions in closing written submissions and orally much later, during an additional, final day of hearing. Ultra Tune’s final stance was still to downplay the seriousness of the conduct engaged in by its very senior officers.

106 In early 2015, Mr Ahmed became interested in purchasing an Ultra Tune franchise. Between May 2015 and August 2015, he and his brother, Mr Shahbaz Khalid, had various meetings with Ultra Tune’s State Manager for New South Wales, Mr Nick Tatsis.

107 Ultimately, Mr Ahmed selected a site in Parramatta. In the course of the parties’ dealings with one another, Mr Tatsis made various key representations to Mr Ahmed about the Parramatta site. This included representations about the rent that was payable, the age of the franchise, the price that was payable, the inclusion of the necessary equipment in the sale and whether the deposit that was paid was unconditional. As already noted, the ACCC’s case is that several of those representations were misleading or deceptive, contrary to s 18 of the ACL, and also met the reasonably parallel concept of being false or misleading contrary to a number of paragraphs of s 29(1) of the ACL. It should be noted that although a s 29(1) contravention carries with it the possibility of a civil penalty being imposed, “false” in s 29(1) means objectively incorrect, rather than requiring any state of mind to be established: Sydney Medical Service Co-operative Limited v Lakemba Medical Services Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 763, per Flick J at [17]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1595 per Perry J at [64], and the authority cited in those two paragraphs. Of course, proof that the falsity is intentional may be, and usually will be, a circumstance of aggravation on penalty.