FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

The Dempsey Group Pty Ltd v Spotlight Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 2016

ORDERS

THE DEMPSEY GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 004 722 936) Applicant | ||

AND: | SPOTLIGHT PTY LTD (ACN 005 180 861) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

The parties are to provide orders giving effect to these reasons by 8 February 2019.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DAVIES J:

Introduction

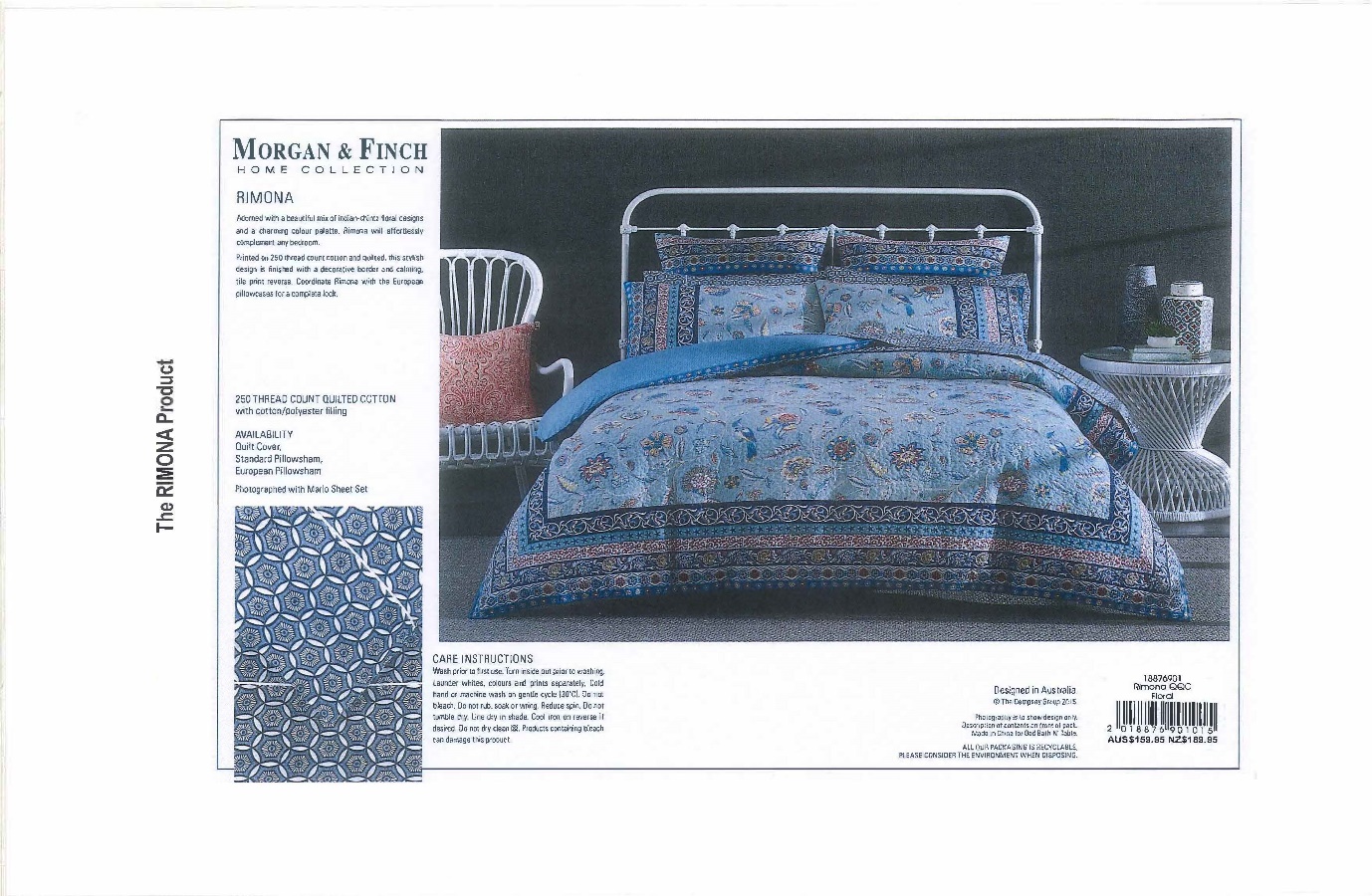

1 The applicant (“Dempsey Group”) and the respondent (“Spotlight”) each sell bed linen product ranges which they design in-house. Dempsey Group sells its product lines under the MORGAN & FINCH brand through its Bed Bath N’ Table stores and Spotlight sells its product lines through its Spotlight stores.

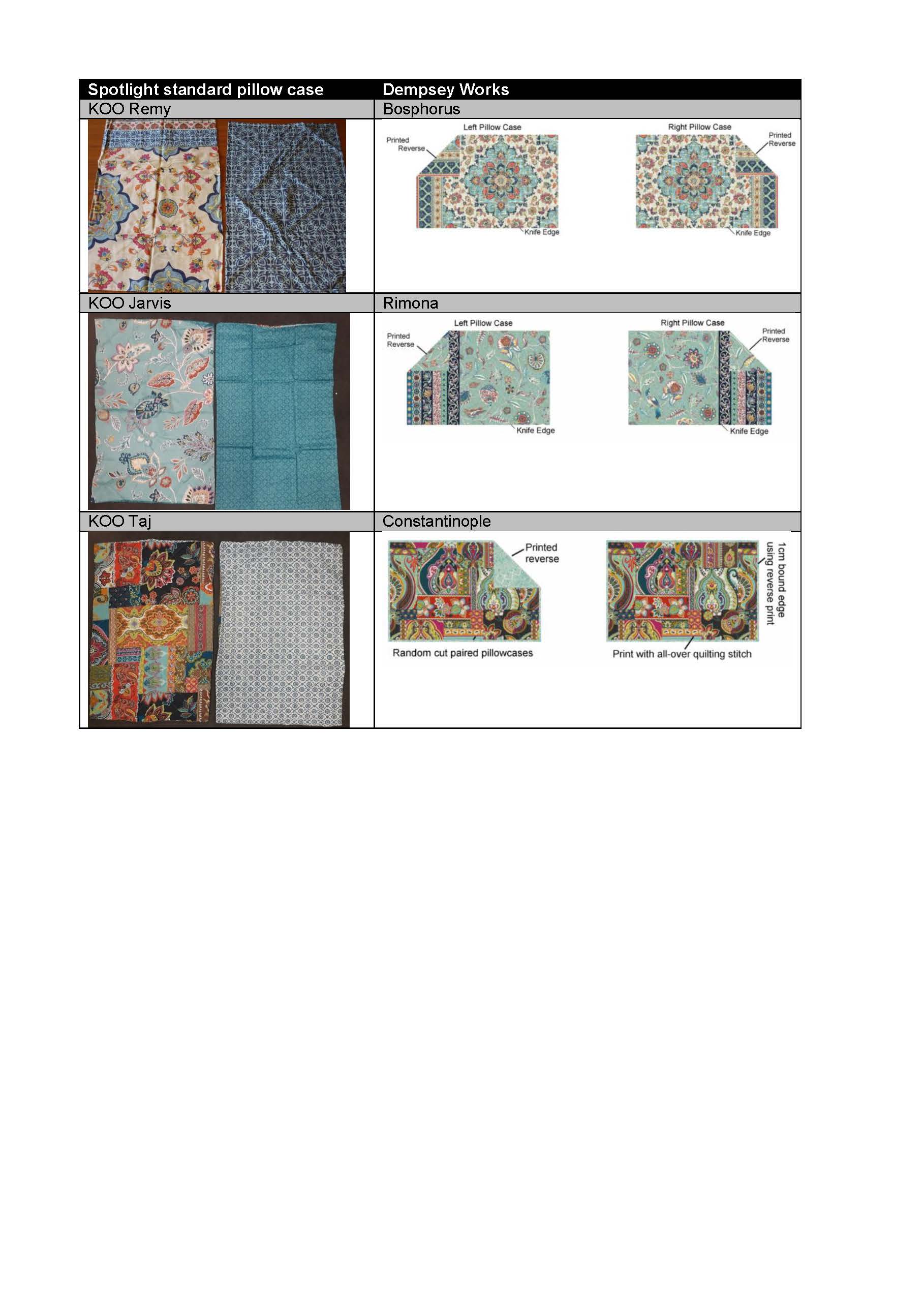

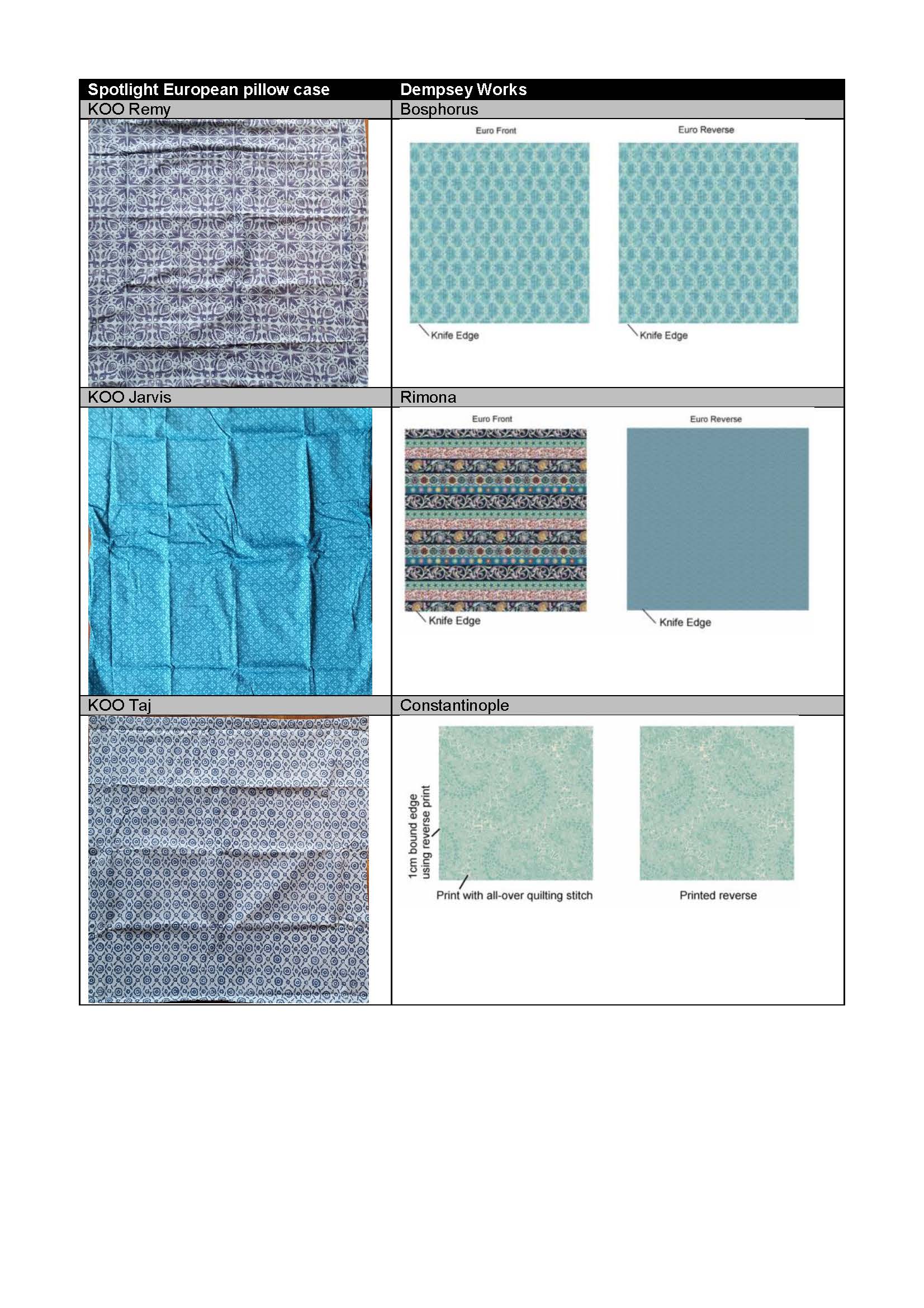

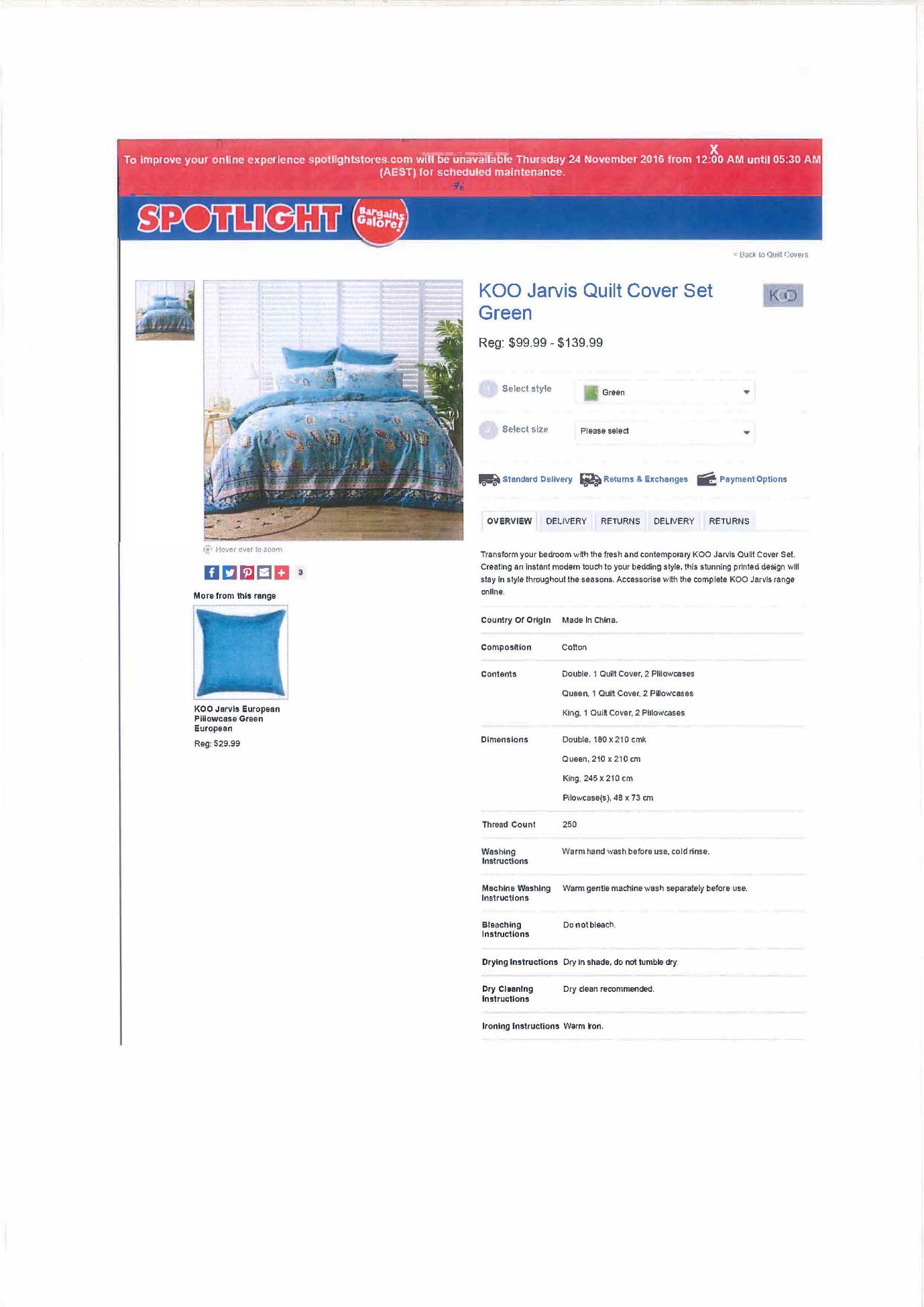

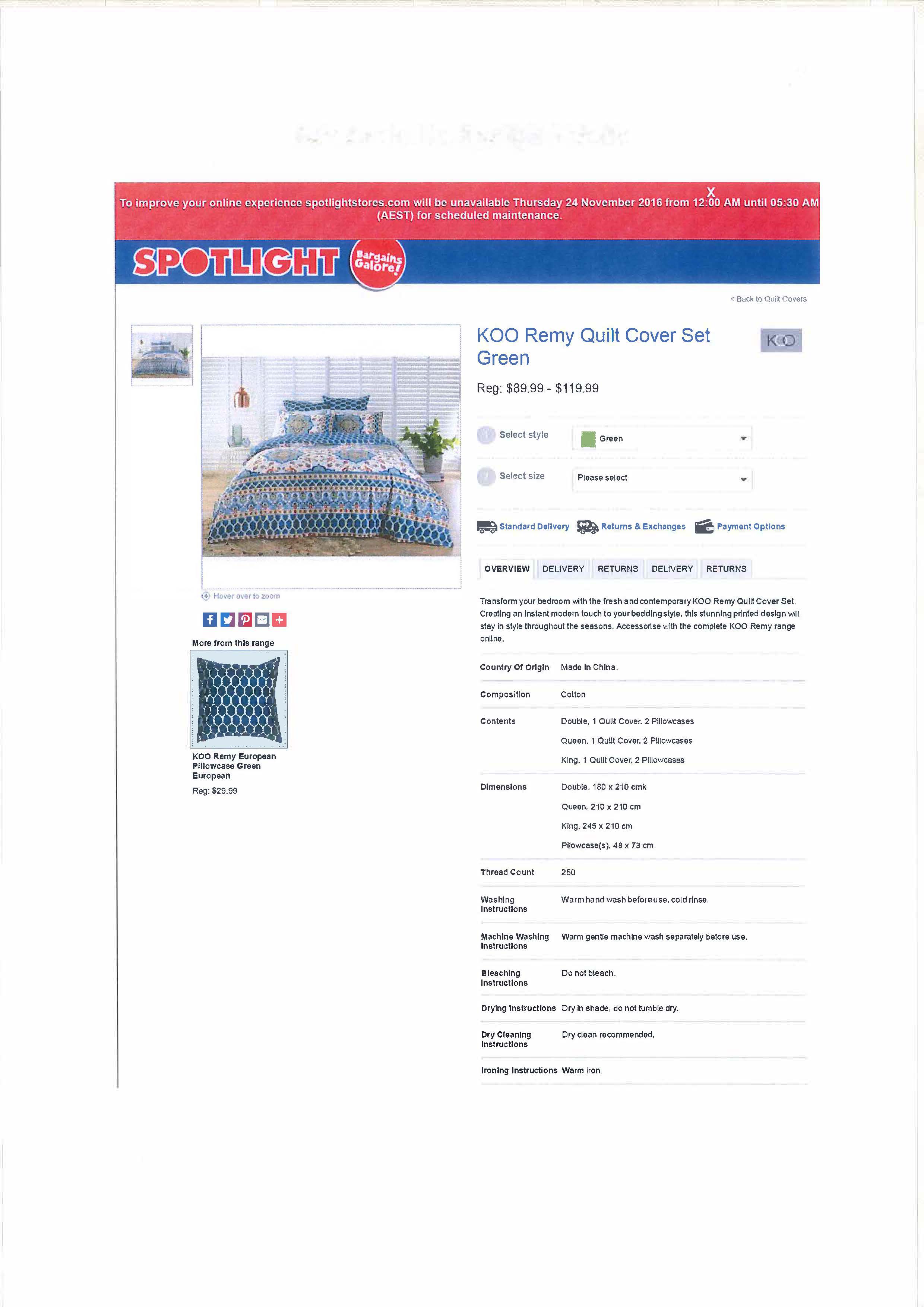

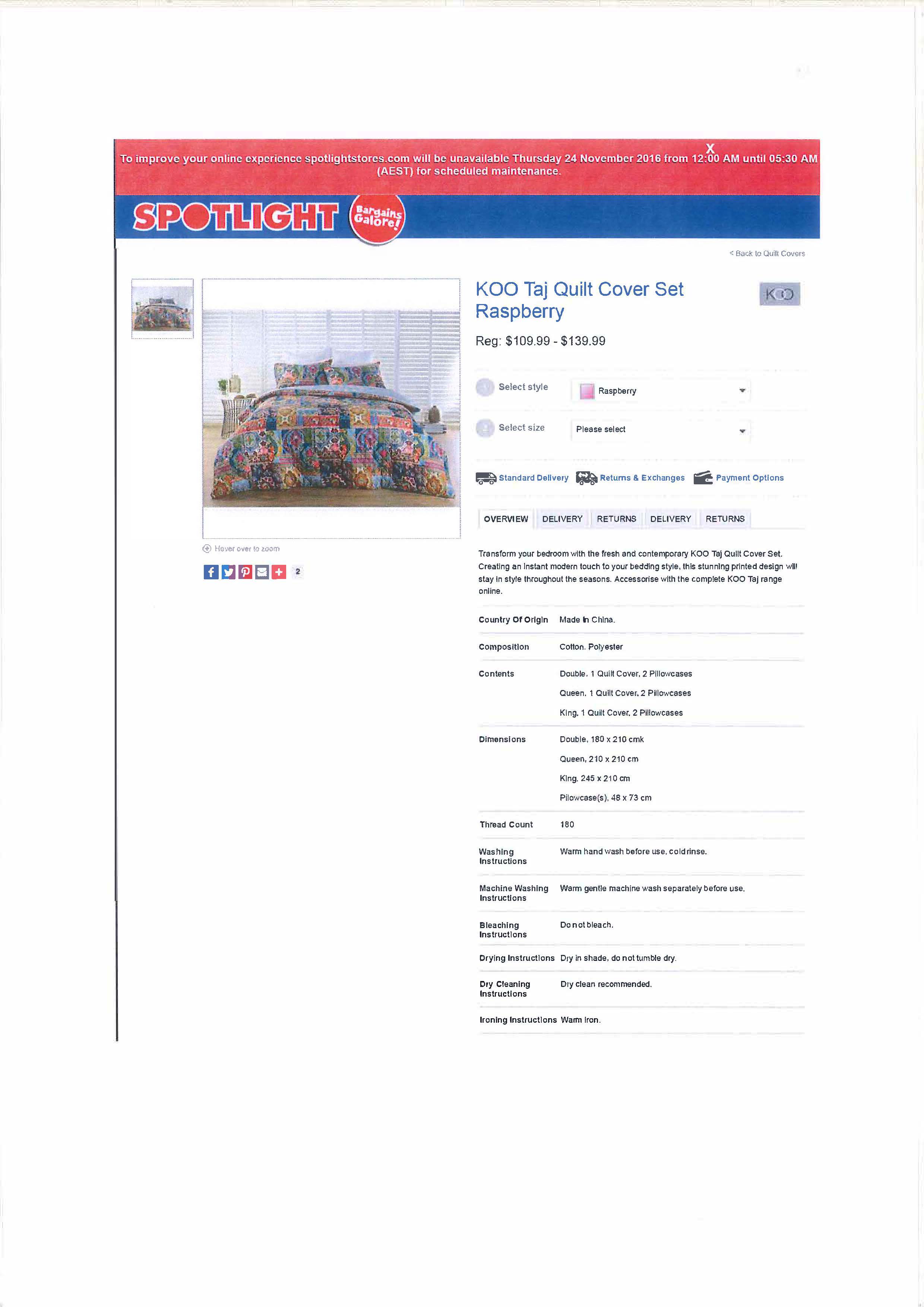

2 Dempsey Group has sued Spotlight for alleged infringement of Dempsey Group’s copyright in three artistic works, comprising the surface designs on Dempsey Group’s “Rimona”, “Bosphorus” and “Constantinople” quilt cover and pillow sets (“the Dempsey products”). Photographs of these products are at Annexure A. The alleged infringements concern Spotlight’s “KOO Jarvis”, “KOO Remy” and “KOO Taj” quilt cover and pillow sets (“the Spotlight products”). Photographs of these products are at Annexure B. Dempsey Group alleges that:

(a) the KOO Jarvis products reproduce a substantial part of the Rimona artistic work;

(b) the KOO Remy products reproduce a substantial part of the Bosphorus artistic work; and

(c) the KOO Taj products reproduce a substantial part of the Constantinople artistic work.

3 Both parties’ products were manufactured in China by a commission-manufacturer, Yantai Pacific Home Fashions (“Yantai”). Dempsey Group has alleged that Spotlight knowingly instructed Yantai to copy its proprietary designs and seeks damages under s 115(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the Act”) as well as additional damages under s 115(4) of the Act for the alleged infringements.

4 Spotlight has admitted that Dempsey Group owns the copyright in the Rimona artistic work and the Bosphorus artistic work, but has disputed Dempsey Group’s ownership of the copyright in the Constantinople artistic work. Spotlight has also admitted:

(a) importing the Spotlight products for the purpose of selling them in Australia;

(b) offering for sale and selling the Spotlight products in Australia through its retail outlets and website; and

(c) printing or authorising another person to print a catalogue which promotes the Spotlight products.

Spotlight has otherwise denied the infringement claims.

5 The parties identified the following issues for determination:

(1) whether Dempsey Group has established that it is the owner of the Constantinople artistic work;

(2) whether the Spotlight products reproduced a substantial part of any of Dempsey Group’s artistic works in suit;

(3) whether Dempsey Group has established that Spotlight had actual or constructive knowledge that the importation and sale of the Spotlight products into Australia would have constituted an infringement of Dempsey Group’s copyright if the products had been made in Australia by Spotlight; and

(4) if copyright in all or any of the Dempsey products is established and it is found that the Spotlight products reproduced a substantial part of all or any of the Dempsey products, the damages to be awarded and whether Dempsey Group is entitled to additional damages.

the statutory context

6 The following sections of the Act are relevant.

7 Section 31(1) provides:

Nature of copyright in original works

(1) For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

…

(b) in the case of an artistic work, to do all or any of the following acts:

(i) to reproduce the work in a material form;

(ii) to publish the work;

(iii) to communicate the work to the public.

8 Section 36(1) provides:

Infringement by doing acts comprised in the copyright

(1) Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

9 Section 14(1) provides:

Acts done in relation to substantial part of work or other subject-matter deemed to be done in relation to the whole

(1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

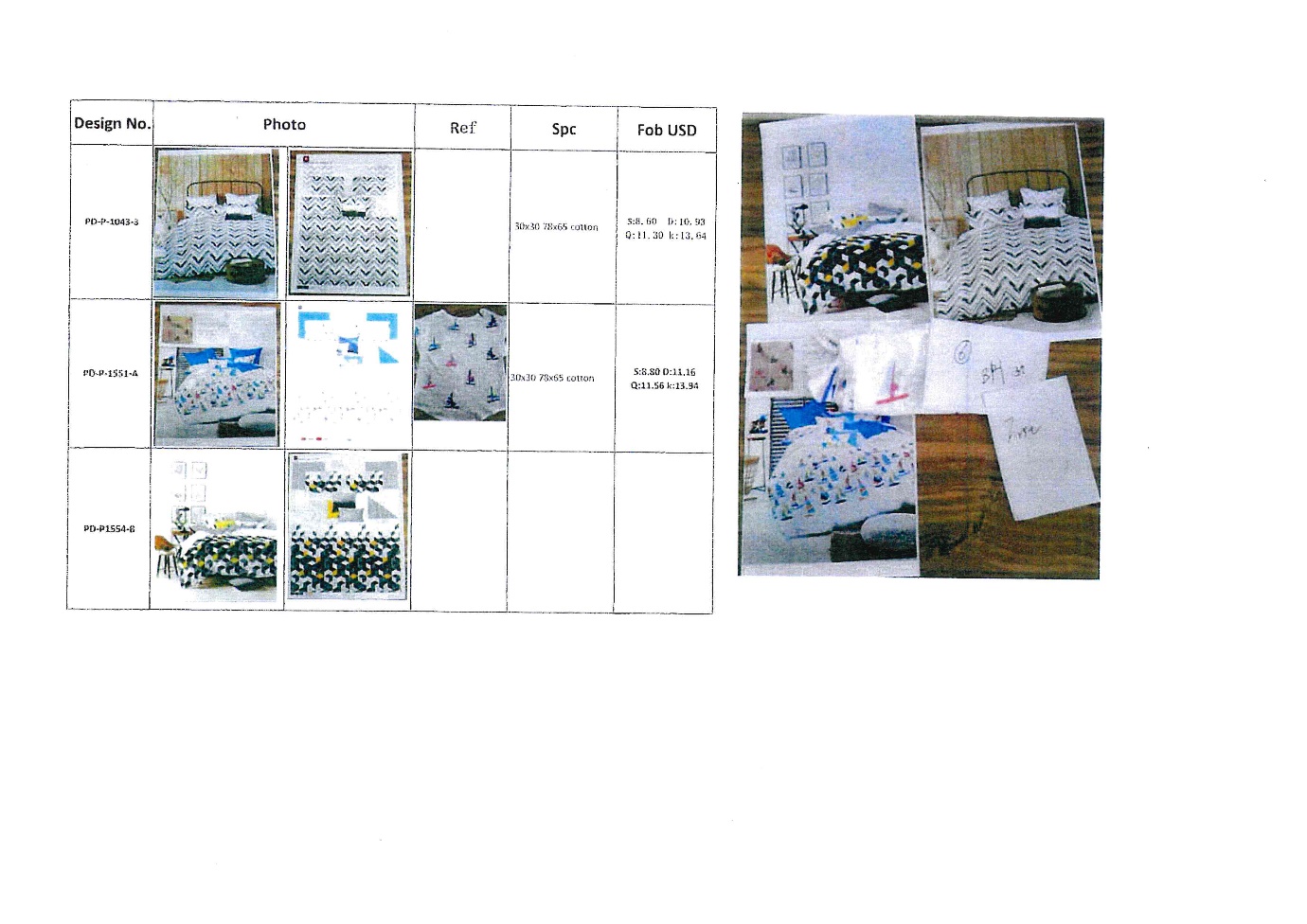

(a) a reference to the doing of an act in relation to a work or other subject-matter shall be read as including a reference to the doing of that act in relation to a substantial part of the work or other subject-matter; and

(b) a reference to a reproduction, adaptation or copy of a work shall be read as including a reference to a reproduction, adaptation or copy of a substantial part of the work, as the case may be.

10 Section 37 provides:

Infringement by importation for sale or hire

(1) Subject to Division 3, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, imports an article into Australia for the purpose of:

(a) selling, letting for hire, or by way of trade offering or exposing for sale or hire, the article;

(b) distributing the article:

(i) for the purpose of trade; or

(ii) for any other purpose to an extent that will affect prejudicially the owner of the copyright; or

(c) by way of trade exhibiting the article in public;

if the importer knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article would, if the article had been made in Australia by the importer, have constituted an infringement of the copyright.

(2) In relation to an accessory to an article that is or includes a copy of a work, being a copy that was made without the licence of the owner of the copyright in the work in the country in which the copy was made, subsection (1) has effect as if the words “the importer knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that” were omitted.

11 Section 38 provides:

Infringement by sale and other dealings

(1) Subject to Division 3, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, in Australia, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright:

(a) sells, lets for hire, or by way of trade offers or exposes for sale or hire, an article; or

(b) by way of trade exhibits an article in public;

if the person knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article constituted an infringement of the copyright or, in the case of an imported article, would, if the article had been made in Australia by the importer, have constituted such an infringement.

(2) For the purposes of the last preceding subsection, the distribution of any articles:

(a) for the purpose of trade; or

(b) for any other purpose to an extent that affects prejudicially the owner of the copyright concerned;

shall be taken to be the sale of those articles.

(3) In this section:

“article” includes a reproduction or copy of a work or other subject-matter, being a reproduction or copy in electronic form.

12 Section 115 provides:

Actions for infringement

(1) Subject to this Act, the owner of a copyright may bring an action for an infringement of the copyright.

(2) Subject to this Act, the relief that a court may grant in an action for an infringement of copyright includes an injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the court thinks fit) and either damages or an account of profits.

(3) Where, in an action for infringement of copyright, it is established that an infringement was committed but it is also established that, at the time of the infringement, the defendant was not aware, and had no reasonable grounds for suspecting, that the act constituting the infringement was an infringement of the copyright, the plaintiff is not entitled under this section to any damages against the defendant in respect of the infringement, but is entitled to an account of profits in respect of the infringement whether any other relief is granted under this section or not.

(4) Where, in an action under this section:

(a) an infringement of copyright is established; and

(b) the court is satisfied that it is proper to do so, having regard to:

(i) the flagrancy of the infringement; and

(ia) the need to deter similar infringements of copyright; and

(ib) the conduct of the defendant after the act constituting the infringement or, if relevant, after the defendant was informed that the defendant had allegedly infringed the plaintiff’s copyright; and

(ii) whether the infringement involved the conversion of a work or other subject-matter from hardcopy or analog form into a digital or other electronic machine-readable form; and

(iii) any benefit shown to have accrued to the defendant by reason of the infringement; and

(iv) all other relevant matters;

the court may, in assessing damages for the infringement, award such additional damages as it considers appropriate in the circumstances.

Consideration for relief for electronic commercial infringement

(5) Subsection (6) applies to a court hearing an action for infringement of copyright if the court is satisfied that:

(a) the infringement (the proved infringement) occurred (whether as a result of the doing of an act comprised in the copyright, the authorising of the doing of such an act or the doing of another act); and

(b) the proved infringement involved a communication of a work or other subject-matter to the public; and

(c) because the work or other subject-matter was communicated to the public, it is likely that there were other infringements (the likely infringements) of the copyright by the defendant that the plaintiff did not prove in the action; and

(d) taken together, the proved infringement and likely infringements were on a commercial scale.

(6) The court may have regard to the likelihood of the likely infringements (as well as the proved infringement) in deciding what relief to grant in the action.

(7) In determining for the purposes of paragraph (5)(d) whether, taken together, the proved infringement and the likely infringements were on a commercial scale, the following matters are to be taken into account:

(a) the volume and value of any articles that:

(i) are infringing copies that constitute the proved infringement; or

(ii) assuming the likely infringements actually occurred, would be infringing copies constituting those infringements;

(b) any other relevant matter.

(8) In subsection (7):

“article” includes a reproduction or copy of a work or other subject-matter, being a reproduction or copy in electronic form.

13 Section 196 provides:

Assignments and licences in respect of copyright

(1) Copyright is personal property and, subject to this section, is transmissible by assignment, by will and by devolution by operation of law.

(2) An assignment of copyright may be limited in any way, including any one or more of the following ways:

(a) so as to apply to one or more of the classes of acts that, by virtue of this Act, the owner of the copyright has the exclusive right to do (including a class of acts that is not separately specified in this Act as being comprised in the copyright but falls within a class of acts that is so specified);

(b) so as to apply to a place in or part of Australia;

(c) so as to apply to part of the period for which the copyright is to subsist.

(3) An assignment of copyright (whether total or partial) does not have effect unless it is in writing signed by or on behalf of the assignor.

(4) A licence granted in respect of a copyright by the owner of the copyright binds every successor in title to the interest in the copyright of the grantor of the licence to the same extent as the licence was binding on the grantor.

Background facts and evidence

14 Dempsey Group, through its subsidiary Domestic Textile Corporation Ltd (“DTC”), has its products manufactured through a range of manufacturers, one of which is Yantai. Dempsey Group first started having products manufactured by Yantai in 2009 and Yantai, on average, has manufactured between 100–115 new and repeated products for Dempsey Group each year. Yantai began supplying Dempsey Group with the Constantinople product in September 2013, the Bosphorus product in July 2014 and the Rimona product in January 2016.

15 Yantai manufactures for a number of other well-known companies and its other customers, until recently, included Spotlight. Spotlight had been a customer of Yantai since 2008 but it stopped using Yantai following Dempsey Group’s infringement claim.

16 Spotlight buyers came to Yantai’s showroom in Shandong Province, China, twice yearly to arrange commission-manufacturing. Dempsey Group’s case is that at one of those visits, which took place on 29 April 2016, the Spotlight buyers were taken to the third floor of Yantai’s premises, where Yantai’s commission-manufactured products were displayed under the names of the commissioning clients. It is claimed that the Spotlight buyers expressed particular interest in products of Dempsey Group displayed under a “Bed Bath N’ Table” sign and that one of the buyers, Ms Kellie Howitt, selected three items from the Bed Bath N’ Table display, which were from the Rimona, Bosphorus and Constantinople ranges, and asked that they be brought to the meeting room where she discussed the products to be commission-manufactured with the Yantai representatives, including three to be based on the Dempsey products with modifications to the surface designs. The three Spotlight products said to be based on the Dempsey products are the products which became known as KOO Jarvis, KOO Remy and KOO Taj, which Yantai is said to have manufactured according to Spotlight’s specifications. Dempsey Group’s case is that Ms Howitt was told by Mr Thomas Chen, a Yantai representative who attended at the meeting, that Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright in the products selected by Ms Howitt and that the Spotlight buyers knowingly instructed Yantai to copy Dempsey Group’s proprietary designs. Mr Chen was called as a witness by Dempsey Group.

17 Spotlight’s witnesses, who included Ms Howitt, gave a very different account of the visit and meeting. On their accounts the Spotlight buyers did not know and had no reason to suspect that the designs they selected were based on artistic works in which Dempsey Group owned the copyright. In short, Spotlight’s case is that the Spotlight products came into existence through Spotlight’s conventional buying process and if the Spotlight products do reproduce a substantial part of the Dempsey artistic works, that happened as a result of Yantai’s careless (or opportunistic) conduct, rather than any wrongdoing on the part of Spotlight.

The evidence about Spotlight’s buying process

18 Ms Howitt gave unchallenged evidence about Spotlight’s buying process. Ms Howitt is employed by Spotlight as a wholesale buyer of bed linen and has been in that position since about May 2015. Prior to working at Spotlight she worked in a number of similar roles for other retail businesses and has about 15 years’ experience in this type of role. The role includes sourcing, developing and selecting multiple product ranges for sheet sets, quilt cover sets, bed cushions, coverlets, bed spreads and flannelette sheets. She is responsible for developing up to 150 new product designs every six months and as part of this work, she goes on between two and four overseas buying trips every year.

19 Ms Howitt gave the following description of a typical buying trip: a typical buying trip first involves the development of inspiration or mood boards before leaving Australia which identify themes, colours, looks or trends that will form the basis of Spotlight’s bed linen designs for seasonal or fashion products. Spotlight also stocks plain or standard types of designs which are often present in the range on an ongoing basis. The types of themes that might appear on a mood board are bohemian, tropical, botanical or coastal and, when developing seasonal or fashion products, Ms Howitt may also place emphasis on a particular colour. The purpose of the mood board is to focus her mind on particular style themes, rather than to act as a prescriptive list of particular items that she needs to purchase. The mood boards do not limit the types of designs that she might ultimately purchase on that buying trip.

20 The second stage of a typical buying trip involves travelling to Europe or the United States to visit trade shows and retail stores to identify new market trends relating to products and customer experiences, such as store layouts, ticketing (that is, small product specific signage) and the positioning of products in stores. During this stage of the buying trip Ms Howitt also gathers inspiration for new products and collects samples to take to Spotlight’s vendors. She looks for samples that comprise patterns, colours and textures that she believes could sell well in Spotlight’s stores as bed linen. She does not collect samples in Australia for this purpose. A sample may take any form and can be clothing items, curtain fabrics, swimsuits and even non-textile goods like porcelain dinner plates.

21 Once she has collected samples, she takes them to Spotlight’s vendors in China. She uses the samples she has collected as either a colour reference or a design reference. The colour references are useful because she sometimes finds it difficult to describe a particular colour accurately to Spotlight’s vendors, most of whom are based in China, as she is dealing with people for whom English is not a first language. She uses design references to help describe visual features and textures to vendors. In order to discuss these concepts with vendors she finds it useful to have physical samples that she can use to illustrate the type of design she is trying to achieve.

22 Ms Howitt gave the following description about the process of ordering products. At meetings with vendors she discusses samples, relevant colour references or design references, and the types of products that she wants to buy. In addition to the samples she has collected during her buying trip, vendors may also show her sample products which may be physical samples on display in their showroom or images of other products in catalogues. The discussions with vendors usually occur at the vendor’s showroom premises. She instructs vendors to create a design by reference to the samples discussed during their meeting and when this happens she does not provide detailed instructions on how the new design should look or where particular visual features should be placed. She does not spend a lot of time on the detail of a potential design, and relies on the vendors to do this work. The sort of instructions she provides to the vendors are general and they often relate to her observations about what has been successful from a sales perspective in recent years in Spotlight stores. She stated that the types of general instructions she provides include that:

(a) a particular visual feature (such as a picture of a bird) in a sample be retained;

(b) a particular design style (like patchworks) is to be used;

(c) a particular level of colour brightness be applied – for example a washed out look, a gradually fading light to dark colour spectrum or bold and bright colours; and

(d) particular design features be omitted if they will increase the purchase price to a point that will exceed her budget, such as a trim like a tassel or an embroidery feature.

23 Her evidence was that, with any design shown to her by vendors, she relies on the vendor to tell her if Spotlight can purchase products bearing the exact design or whether it should be used as an inspiration only, like the samples she collects from overseas. In many cases she only uses a sample provided by a vendor for inspiration. Following these discussions the vendors then send pricing proposals by email for the products that have been discussed. She then places orders for a selection of those products based on what she can afford to buy within the constraints of her budget.

24 Ms Howitt stated that Spotlight’s vendors tend to operate out of large showrooms that display both their own designs and those of their customers. Typically she walks through the showrooms and picks up samples from the display floor before sitting down with a vendor to discuss designs. During the meeting itself, she often lines up some of the samples along the floor roughly to imitate a store shelf at a Spotlight store. By doing that she gets a feel for how the various samples might come together as a product range and she then considers whether any elements of a relevant mood board are missing. Typically she places design reference samples next to each other in a back row and any colour reference samples are placed in front of them in a front row. This allows her to mix and match design themes with colours.

25 The discussions she has with the vendors during those meetings are interactive and move at a fairly quick pace. She gave evidence, by way of example, that sometimes a representative of a vendor suggests that a proposed range could be improved by adding another sample from the vendor’s range, or sometimes she realises that the proposed range is missing an aspect of the mood board and she asks the vendor to provide some additional samples to fill the gap. She also collects relatively simple designs from the vendors’ display rooms that do not correspond to a mood board or require a shelf simulation line up. She simply gives the samples to the vendor representatives that she is working with and asks them to offer her a price for them.

26 Spotlight does not receive any end products or price lists during a buying trip, nor are any orders made during the trip. After the meetings, the vendors send her a written proposal by email that incorporates details of the products discussed and pricing information. These documents usually include computer aided design drawings of the proposed designs that Ms Howitt understands are produced by the vendor’s in-house designers.

27 She deposed that sometimes she receives price lists from a vendor in iterations. This is usually done at her request because she wants pricing for some products urgently. When she reviews a price list from a vendor her primary concern is with the prices themselves rather than the details of the designs that are presented. She then responds by placing an order for the products that she wants to buy. Those products are then manufactured by the vendor and shipped to Australia (and the other countries where Spotlight has stores) for distribution.

The buying trip in April 2016

28 Ms Howitt gave evidence that she went on a buying trip in April 2016 to source a new collection of bed linen products. Before she went, she developed mood boards for this trip with Ms Corinne Rico Estrada. Ms Rico Estrada was Spotlight’s then Business Development Manager – Manchester and Ms Howitt reported directly to her. Ms Howitt’s evidence was that their inspiration for the products that later became known as KOO Jarvis, KOO Remy and KOO Taj was drawn from a number of looks including bohemian, tropical, botanical and coastal. She said that she did not retain a copy of those mood boards.

29 On about 21 April 2016, Ms Howitt and Ms Rico Estrada travelled to Los Angeles to collect sample products and spent approximately three days there. On 25 April 2016 they travelled to Shanghai, China and met with other buyers from Spotlight, who included Ms Carla Frische and Ms Aruna Singh.

30 On 29 April 2016, Ms Howitt, Ms Rico Estrada, Ms Frische and Ms Singh travelled together to visit Yantai’s showroom. Ms Howitt deposed that she had visited Yantai’s premises and placed orders with Yantai in the past and had an established working relationship with a number of its staff.

Yantai’s showroom

31 Yantai’s showroom consists of four levels. The uncontroversial evidence was that at the relevant time, the first floor (at ground level) displayed infant/children’s bed linen products. The main showroom, located on the second floor, displayed products and textiles designed by Yantai and also had a meeting room. The third level consisted of products and designs that Yantai manufactured for its retailer customers. This room was separated into individual retailer spaces consisting of a made-up display bed, with some products unpackaged to display the textile design and shelving units stacked with the retailer’s packaged bed linen products displayed in the form in which they were dispatched, including brand name and price tag. Mr Chen described the display area as “like a retail store”. The individual retailer spaces included a Bed Bath N’ Table display area under a sign labelled “Bed Bath N’ Table”. The fourth level displayed special fabric and products designed by Yantai.

The visit to Yantai on 29 April 2016

32 Evidence about what happened at the visit on 29 April 2016 was given by Mr Chen for Dempsey Group and by Ms Howitt, Ms Rico Estrada, and Ms Frische for Spotlight.

33 Mr Chen described himself as the owner, general manager and legal representative of Yantai. He gave evidence that present at the visit from Spotlight were Ms Howitt, Ms Rico Estrada, Ms Frische and Ms Singh and from Yantai were himself, Ms Ellie Gao (a designer), Mr Sean Yuan (a merchandise operator) and the sample manager (who spoke no English). His recollection was that the visit lasted “a little bit over three hours” and he was present the whole time but for two short bathroom breaks.

34 Mr Chen’s account was that Mr Yuan collected the Spotlight buyers from their hotel and they arrived around 9.00am. They went upstairs and walked through the sample room on the second floor and arrived at the meeting room where they were greeted. The Spotlight buyers chose some samples from the second floor, then went to the third floor where they expressed particular interest in the samples shown on the bed in the Bed Bath N’ Table display. Ms Howitt asked him which were the most popular, bestselling products of Bed Bath N’ Table. He asked his colleague Mr Frank Jia, who was responsible for the sales of Dempsey Group’s products, to provide images of those products.

35 In the meantime, Ms Howitt took samples of products from the Bed Bath N’ Table display shelf, which included the Rimona, Bosphorus and Constantinople products, and asked for the Rimona sample to be opened up and displayed on the bed. Ms Howitt started discussing the design with Reng Shing (another Yantai designer) at which point Ms Gao said to Mr Chen in Chinese: “This belong to DTC. Be careful”, and Mr Chen then said to Ms Howitt in English: “Be careful – this belong to DTC”. Mr Chen said that no-one paid attention. Ms Howitt asked the Yantai staff to bring the samples she had selected from the Bed Bath N’ Table display to the meeting room. As the Rimona sample had been opened, one of the Yantai staff fetched a packaged sample from the store room. On Mr Chen’s evidence they spent around 20 minutes at the Bed Bath N’ Table display. The Spotlight buyers then picked some other samples from that floor and went down to the second floor where they chose some samples from Yantai’s own design patterns before going into the meeting room.

36 In the meeting room, Mr Chen showed Ms Howitt images of the five bestselling products sent to him by Mr Jia. Ms Howitt was said to be very happy because the three samples she had selected were among the images. The Spotlight buyers spent around an hour laying out the various samples and fabrics from Yantai’s showroom and the samples and products they had brought with them, and then a discussion took place for approximately one to two hours principally between Ms Howitt, Reng Shing and Ms Gao as to the specific products that Spotlight wanted Yantai to manufacture. Mr Chen said that about 13 products in total were discussed, which included four products based on the Bed Bath N’ Table samples. It was also his evidence that during that discussion he repeated that the samples were DTC’s and that there was a copyright issue “but no-one paid attention”.

37 In cross-examination, Mr Chen agreed that:

(a) Ms Howitt had never before made a request to see the bestselling designs of another retailer;

(b) he knew that Dempsey Group owned the copyright in the artistic works of the Rimona, Bosphorus and Constantinople products; and

(c) he did not tell the Spotlight buyers that Yantai could not manufacture the products that became known as the KOO Jarvis, KOO Remy and KOO Taj products because of Dempsey Group’s copyright in the Dempsey products.

38 Ms Howitt’s evidence was that in addition to Mr Chen, Ms Gao and Mr Yuan, Mr Sam Wang, the account manager, was also present. On her recollection the meeting lasted around two and a half hours. She spent very little time on the first floor, then around one hour on the second floor collecting samples and around ten minutes on the third floor. Her evidence was that she briefly inspected this room to gain intelligence about market trends, but did not choose any samples from this level. They then went to the meeting room where they discussed the samples that the Spotlight buyers had chosen and the samples they brought with them. On her recollection, they were around 30 minutes in the meeting room. Ms Howitt laid out the samples with design references in the back row and colour references in the front row and then looked to see whether there were any gaps in design and colour.

39 On Ms Howitt’s evidence, Mr Chen was only present for about half of the meeting and he came in and out of the meeting several times. Mr Wang and Mr Yuan were in the room most of the time (but both of them occasionally left temporarily). Ms Howitt led the discussion but Ms Rico Estrada, Ms Frische and Ms Singh were also present. Ms Rico Estrada oversaw the discussion and occasionally contributed, but was generally an observer rather than an active participant. Ms Howitt occasionally asked Ms Frische for some feedback on the designs they were discussing, but she was not otherwise actively involved in the discussion. Ms Singh was in the room during the meeting but she did not participate in the discussions.

40 Ms Howitt recalled that about a dozen samples were discussed. She recalled that after the meeting she ordered the KOO Jarvis, KOO Remy and KOO Taj products amongst others, including one which would become a product called KOO Lottie.

41 Her evidence was that the KOO Remy product was based on a sample that Yantai provided to her, not on a sample that she selected from the showroom. She said that the samples she had selected were very intricate and detailed and she needed something a bit cleaner, and so Yantai presented her with the sample. Ms Howitt used that sample as a design reference and as she liked the colour she did not use a separate colour reference but asked Yantai to create a design “inspired” by the sample. The notation recorded by Yantai in relation to this product was that Yantai was to “creat[e] a design”. In cross-examination Ms Howitt said that she could not recall whether she asked about the copyright in the design but she repeated her evidence that the sample was not presented to her as a Bed Bath N’ Table design and she denied that she asked for changes to be made because she knew that Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright in the design.

42 Her evidence was that the KOO Taj product was based on an unmarked sample she had selected from a display bed on the second floor showroom which she used as a design reference and as she liked the colour she did not use a separate colour reference. She stated that she really liked the patchwork and that patchwork sells very well for Spotlight, so she asked Yantai to create a design for them using the sample as a design reference. The notation recorded by Yantai in relation to this product was that Yantai was to “creat[e] a design” based on the sample. In cross-examination Ms Howitt said that she could not recall whether she asked about the copyright in this design but she repeated her evidence that the sample was taken from the showroom on the second floor and she denied that she asked for changes to be made because she knew that Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright in the design.

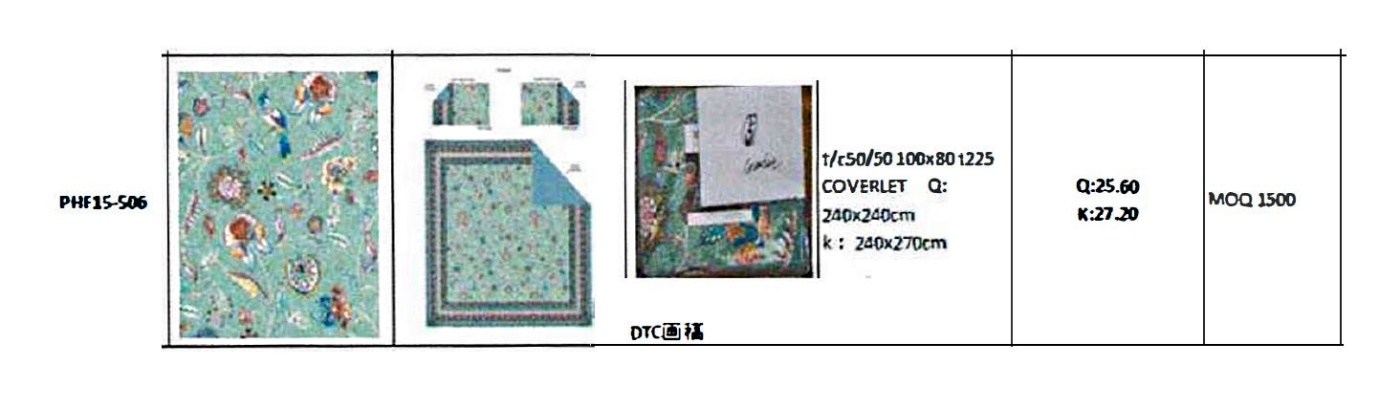

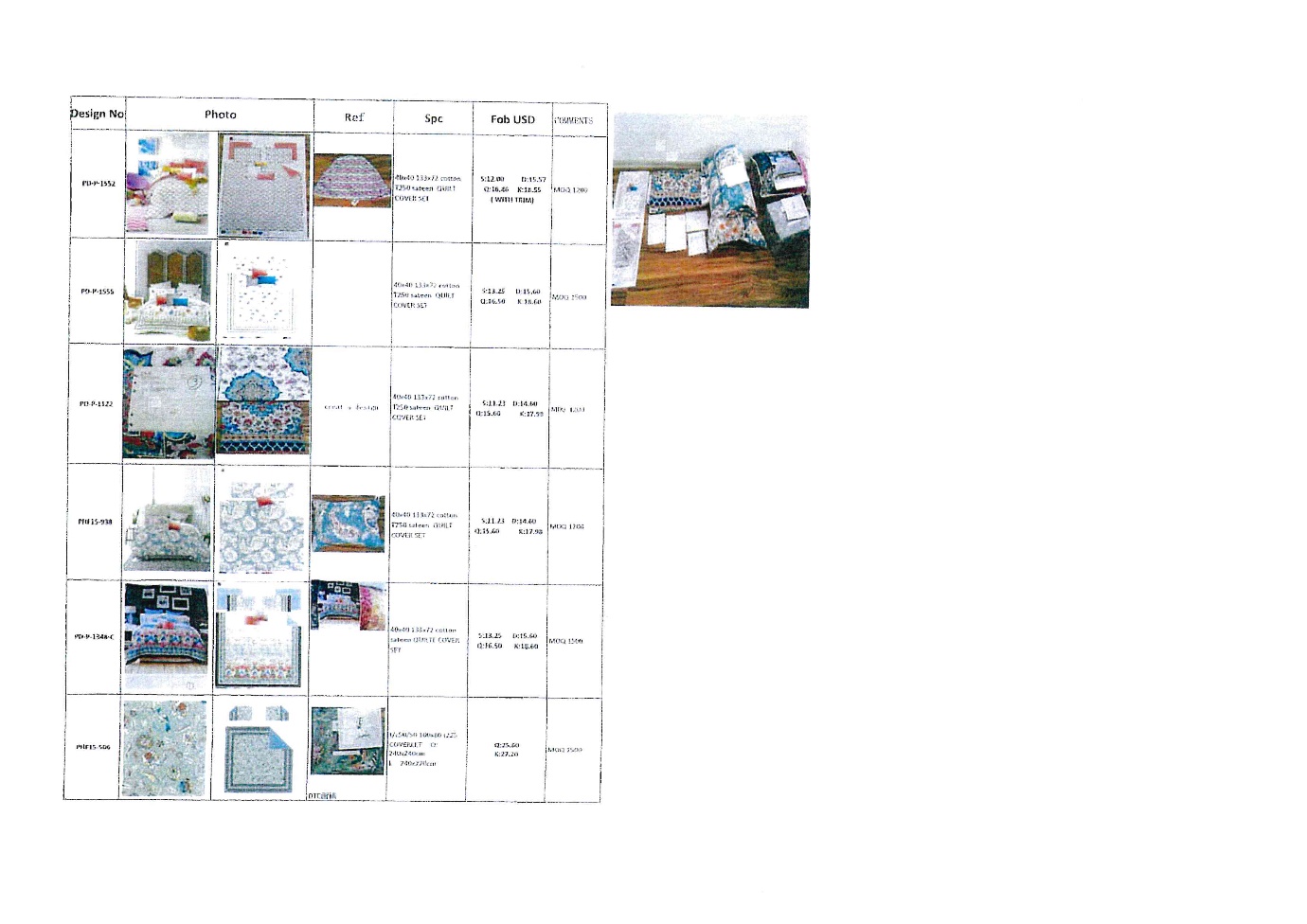

43 Her evidence was that she did not view any design reference samples during the meeting relating to the KOO Jarvis product. She had selected a computer aided design of a quilt cover from Yantai but she did not like the colours so she asked them to recolour that design for her. On her evidence, the first time that she saw the design that became KOO Jarvis was when she received a spreadsheet from Yantai on 29 April 2016 (“the first Yantai spreadsheet”). The complete spreadsheet is attached at Annexure C. The relevant row in that spreadsheet is next to the reference PHF15-506, which is extracted below for convenience.

44 Ms Howitt acknowledged that she had seen the sample that appears in the photograph in the third column, which is a sample of the Rimona product, which, she said, was in its packaging. She knew at the time that it was a MORGAN & FINCH product and that this was a house brand of Bed Bath N’ Table but she said she did not see it out of its packaging and she used it only as a colour reference for the design which became the sample referred to as PD-P-1348-C in the first Yantai Spreadsheet and not as a design reference for the KOO Jarvis product. Asked in examination in chief as to whether she recalled any instructions she gave about the process of recolouring, she said:

Yes. I had seen a quilt cover in its packet, and the ground colour was beautiful. So I had requested that Yantai Pacific refer to the ground colour of another quilt cover within – and asked them to recolour based on the ground colour of the [computer aided design].

45 She also gave evidence that when she received the first Yantai Spreadsheet she did not suspect that the designs depicted in the photos in the first two columns next to the reference PHF15-506 had any similarities to the design of the MORGAN & FINCH product. She said she chose PHF15-506 over PD-P-1348-C because she liked it more. It was put to Ms Howitt in cross-examination, and she denied, that she used the insert in the packaging of the MORGAN & FINCH product as a design reference. Ms Howitt was also cross-examined on whether she had asked about copyright in the design when she received the first spreadsheet. Ms Howitt’s evidence was that she did not, nor did she ask when she received the second spreadsheet (see [51]) or placed the order.

46 In cross-examination Ms Howitt also denied that:

(a) she had spent 20 minutes at the Bed Bath N’ Table display on the third floor;

(b) she asked Mr Chen which were Bed Bath N’ Table’s bestselling designs;

(c) she selected the three Dempsey products from the display area on the third floor;

(d) she asked for those samples to be taken to the meeting room;

(e) Mr Chen showed her images of Bed Bath N’ Table’s bestselling designs;

(f) she was pleased because three of the samples she had selected were amongst the

estsellers;

(g) Mr Chen told her to be careful because Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright in the designs;

(h) she knew that the samples used for the KOO Taj and KOO Remy designs were Bed Bath N’ Table’s products; and

(i) she knew what the Rimona design looked like because she asked the Yantai representatives to display it on the bed at the Bed Bath N’ Table display.

47 Ms Rico Estrada corroborated Ms Howitt’s evidence that Mr Wang was at the meeting and that Mr Chen was not with them throughout the whole of the meeting but came and went. Ms Rico Estrada was unable to recall who selected the samples that were used to create the designs for the Spotlight products but her evidence was that the Spotlight buyers did not make any selection from the third floor, but only from the second floor showroom. When it was put to her in cross-examination that Ms Howitt selected Bed Bath N’ Table products from the third floor of the showroom and Mr Chen told Ms Howitt that Bed Bath N’ Table owned the copyright in those products, she said that was not correct and no selection was made from the third floor.

48 Ms Frische’s evidence was that until the end of 2016 she visited Yantai regularly on buying trips and Mr Chen took the lead role for Yantai. She gave only very general evidence about the visit. She could not recall any of the samples that her colleagues brought to the meeting or selected from the range presented by Yantai nor could she recall whether the staff of Yantai who attended the meeting presented any additional samples during the course of the meeting. But she did recall that Mr Wang was also present. She stated that her role during the meeting was quite passive. She observed and listened as Ms Howitt discussed particular products with Yantai’s representatives and she assessed whether that product was likely to sell well in New Zealand, Singapore and Malaysia.

49 Ms Rico Estrada and Ms Frische also each gave evidence that they generally relied on Mr Chen and his staff to advise them as to which samples Spotlight could use.

The order

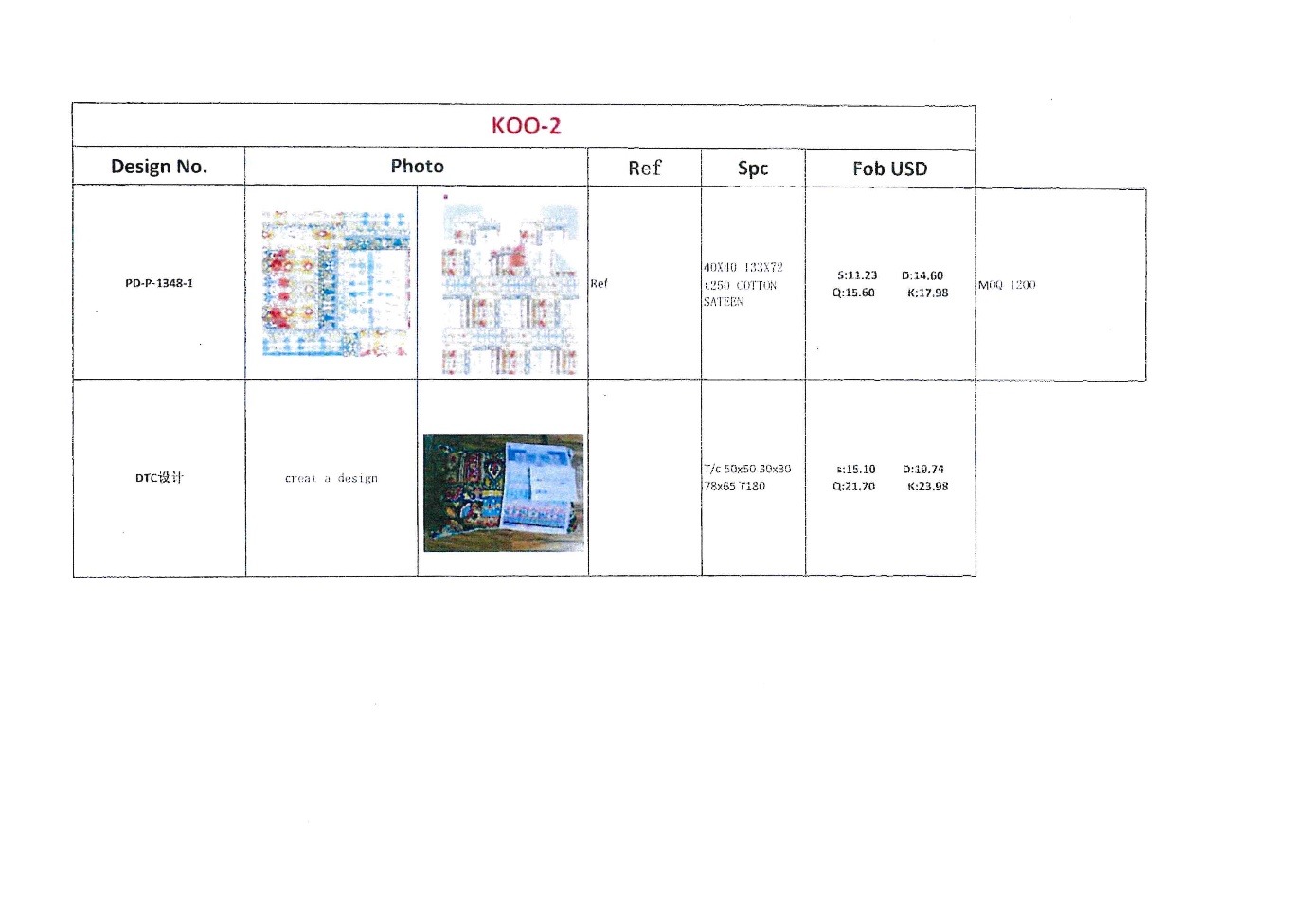

50 The first Yantai Spreadsheet was sent by Mr Chen to Ms Howitt on 29 April 2016. KOO Jarvis is PHF15-506. KOO Remy is PD-P-1122 and KOO Taj is in the last row “DTC [Chinese character]”. The Chinese character means “design”.

51 On 9 May 2016 Ms Howitt received an email from Mr Wang attaching a second spreadsheet that included images of all the product designs and samples that had been discussed during the April 2016 meeting along with pricing information (“the second Yantai spreadsheet”). The second Yantai spreadsheet contained the same product images and pricing information as the first Yantai spreadsheet and consistent, but slightly more detailed, information about product specifications. The second spreadsheet also contained information about a number of additional products that were not covered by the first Yantai spreadsheet.

52 On 7 June 2016, Ms Howitt placed orders based on these proposals, including for the Spotlight products. She ordered the following quantities for each of the Spotlight products:

(a) 320 double bed sized quilt cover sets;

(b) 1,300 queen bed sized quilt cover sets;

(c) 950 king bed sized quilt cover sets; and

(d) 650 European pillowcases.

53 Each quilt set included a quilt cover and two standard size pillow cases.

54 Order forms were sent by Ms Howitt to Mr Wang on 8 June 2016 and samples were sent to Ms Howitt on or around 2 July and 5 July 2016.

55 Between 21 and 22 June 2016, Ms Howitt exchanged a series of emails with Mr Wang about the KOO Lottie product that Ms Howitt had ordered based on a sample that she said that she collected from the second floor showroom. On Mr Wang informing her that the design had previously been sold to Bed Bath N’ Table, Ms Howitt cancelled the order.

56 Ms Howitt approved the samples by emails to Mr Wang on 8 July (KOO Jarvis and KOO Taj) and 3 August 2016 (KOO Remy).

57 On 8 August 2016, Ms Howitt received an email from Mr Wang that stated (among other things):

I knew that we had got the REMY photo for the insert.

But we found problem in some place of the design,

So we make the changes as the attachment.

(errors in original)

58 The “problem” referred to in Mr Wang’s email was not explained to Ms Howitt at the time and she did not ask for an explanation.

Notification of Dempsey Group’s claims

59 On about 30 November 2016, the CEO of Spotlight, Mr Quentin Gracanin, told Mr David Windsor, the general counsel of Spotlight, that Mr Jonathan Dempsey, the managing director of Dempsey Group, had contacted him and complained that the Spotlight products infringed Dempsey Group’s copyright.

60 Mr Dempsey’s evidence was that, in an attempt to avoid a legal dispute with Spotlight and considering the impending Christmas shopping period, he telephoned Mr Gracanin on 29 November 2016. On 30 November 2016 he sent an email to Mr Gracanin attaching images of the Rimona, Bosphorus and Constantinople designs, stating that all three designs were original artwork produced by Dempsey Group’s design team and that Dempsey Group had files of the creation if required. Mr Dempsey asked Mr Gracanin to discuss the matter with his team and to come back to him as to how they handled it, stating “clearly we will also want to know the source of the product and the contact as we will need to ensure that it is not being sold elsewhere”. Mr Gracanin responded by reply email stating that he had forwarded all the information to the relevant “merch team, our GM of Spotlight and our in-house legal counsel” and that somebody would respond/contact Mr Dempsey once they had investigated. Mr Dempsey asked that they get back to him in the next day or two.

61 Mr Windsor’s evidence was that after his discussion with Mr Gracanin, he emailed Mr Dempsey asking him to provide some evidence that Dempsey Group owned the copyright in the Dempsey products. Mr Dempsey responded on 2 December 2016 by email attaching documents in support of proof of ownership. Mr Windsor also spoke to Ms Rico Estrada and Ms Howitt and asked them to contact Yantai and enquire about the origins of the designs which they had applied to the Spotlight products.

62 On 6 December 2016 Mr Dempsey again expressed Dempsey Group’s wish that the matter be “wrapped up as none of us need this at this time of the year!”

63 On 13 December 2016, Mr Windsor received a letter of demand addressed to him in his capacity as Spotlight’s general counsel from DLA Piper on Dempsey Group’s behalf formally alleging that the Spotlight products infringed copyright owned by Dempsey Group in the Dempsey products. Mr Dempsey’s evidence was that as he had not been able to resolve matters with Spotlight he instructed DLA Piper to send the letter. He deposed that the Christmas and New Year periods are the most significant sales periods of the year for Dempsey Group and bed linen retailers generally, during which time Dempsey Group’s weekly sales are generally twice that of its weekly sales in the other months. Spotlight also engaged its solicitors, Cornwall Stodart.

64 Ms Howitt’s evidence was that she had a meeting scheduled for 21 December 2016 at Spotlight’s headquarters with Mr Varouj Mouradian, Yantai’s Australian general manager, and Ms Simona Sparano, who she understood to be a designer. The original purpose of that meeting was to discuss purchasing products. Ms Howitt’s evidence was that during the meeting she told Mr Mouradian that Bed Bath N’ Table had accused Spotlight of infringing its copyright in the designs that appear on products that Yantai had supplied to Spotlight. She asked for an explanation and Mr Mouradian told her that he did not know anything about the Spotlight products and he would ask Mr Chen about them. Mr Windsor was also at that meeting and he gave similar evidence.

65 By letter dated 20 December 2016, Cornwall Stodart informed DLA Piper that Spotlight did not admit any liability in relation to the alleged infringing conduct but undertook once its current stock of Spotlight products was exhausted to the effect that it would cease sales and production of the Spotlight products.

66 DLA Piper responded with a letter to Cornwall Stodart dated 22 December 2016 in which it was stated:

Our client has been in contact with Yantai, and we are instructed that representatives of Spotlight visited the Yantai showroom in April 2016. At that time, the Spotlight representatives became aware of the Dempsey Artistic Works and, upon being informed they were proprietary designs, requested modifications to same so as to form the Spotlight [p]roducts.

67 Mr Windsor deposed that to the best of his knowledge this was the first occasion on which it had been asserted to anyone at Spotlight that its buyers had been told that the designs they were shown were owned by Dempsey (or any third party) or that they had requested that the designs be modified and applied to create the Spotlight products.

68 On 23 December 2016, Ms Howitt sent an email to Mr Mouradian asking him if he had spoken with Mr Chen. Mr Mouradian responded by email of 23 December 2016 in which he advised that Mr Chen had “reconfirmed” that when Ms Howitt visited their showroom in April she asked to be shown the bestsellers of Bed Bath N’ Table and that they showed her pillowcases and inserts from Bed Bath N’ Table. The email stated:

HI KELLIE

I HAVE SPOKEN TO THOMAS FEW MINUTES AGO, AND DISCUSSED AT LENGTH THE HISTORY OF THESE THREE DESIGNS.

THOMAS RECONFIRMED THE FOLLOWING:

1) WHEN YOU VISITED THEIR SHOWROOM IN APRIL, YOU HAVE ASKED TO BE SHOWN THE BEST SELLERS OF BED BATH AND TABLE.

THEY HAVE SHOWED YOU PILLOW CASES AND INSERTS FROM BED BATH AND TABLE.

YOU HAVE REQUESTED FROM PACIFIC HOME FASHION TO PRODUCE ARTWORK FOR FEW DESIGNS WITHIN THE SAME LOOK.

2) UNFORTUNATELY, UNAWARE OF THE COPYRIGHT LAWS IN AUSTRALIA, THEIR [INTERPRETATION] OF SAME LOOK WAS WRONG, BECAUSE THEIR COUNTER SKETCHES WERE TOO CLOSE TO BED BATH AND TABLE DESIGNS. THEY HAVE SUBMITTED TO YOU THE NEW ARTWORK, AND YOU HAVE APPROVED THE SKETCHES, AND GAVE THEM THE ORDER TO PROCEED WITH BULK, WHICH THEY DID.

3) THEY ACCEPT THE ARTWORKS SUBMITTED WERE TOO CLOSE TO BBT DESIGNS, CONSEQUENTLY THEY ARE RESPONSIBLE, AND ARE NEGOTIATING WITH BED BATH AND TABLE TO SOLVE THIS PROBLEM.

PART OF THE SOLUTION OF THIS PROBLEM, BBT HAVE ASKED FOR SPOTLIGHT TO STOP SELLING THESE THREE DESIGNS. EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY, WHICH IS VERY MUCH WITHIN THE RIGHT OF BBT

AND I AM ASKING YOU ON BEHALF OF [YANTAI] TO ACTIVATE THAT IMMEDIATELY.

YOU ALSO NEED TO ASK THE STORES TO RETURN ANY STOCK THEY HAVE OF THESE 3 DESIGNS BACK TO YOUR WAREHOUSE. AND ONCE YOU HAVE ALL THE STOCK BACK TOGETHER WITH ANY STOCK IN YOUR WAREHOUSE, PLEASE ADVISE US , AND PACIFIC HOME FASHION WILL REFUND YOU THE COST OF THE GOODS AND WILL SHIP IT BACK TO CHINA TO BE DESTROYED

I DO APOLOGISE FOR THE INCONVENIENCE CAUSED.

IF YOU HAVE ANY FURTHER QUESTIONS, PLEASE DO NOT HESITATE TO CONTACT ME

(errors in original)

69 This email copied in Mr Windsor, Mr Wang and Ms Sparano.

70 When Mr Windsor received this email he was already in the country with his family for Christmas. He did not take any action until the next working day, which was 28 December 2016. At 10.41am that day he sent an email to Ms Rico Estrada and Ms Howitt asking that the Spotlight products be removed from all stores in Australia and overseas. He deposed that he took this step because of the email received from Mr Mouradian on 23 December 2016.

71 The recall process was commenced and on 29 December 2016, in a periodic internal electronic newsletter that Spotlight distributes to all of its stores called “Spotlight on Communication”, there was a removal notice stating that the Spotlight products must be removed.

72 In January 2017, Spotlight sent further communications to stores reiterating the recall instructions and conducted store audits to ensure that the recall process was being complied with. As part of this process it came to Mr Windsor’s attention that some Spotlight stores had not fully complied with the recall. About this time, Mr Windsor caused steps to be taken to ensure that if any of the Spotlight products were scanned through the Spotlight store point of sale system, a message would be displayed to direct the store attendant not to complete the sale.

73 In February 2017, Mr Windsor took further steps to ensure that Spotlight stores had complied with the recall he had initiated. He instructed Ms Kendra Hounsell, who was Spotlight’s Stock Integrity Manager at that time, to take over supervision of the recall. To implement these instructions, Ms Hounsell decided that it was appropriate to individually telephone the store managers at each of Spotlight’s stores (which then totalled 123). She undertook this process with her colleague, Ms Hang Nguyen. They completed this task between 9 and 14 February 2017. During these calls, they instructed the store managers to “walk the floor” looking for relevant stock and, if any was found, to set it aside for return. The upshot of this process was that:

(a) Spotlight was holding 7033 units in its distribution centres;

(b) there were 54 units still held in stores to be returned (including 41 European pillowcases);

(c) there were 26 units still held in stores as lay-by items (including 4 European pillowcases); and

(d) Ms Hounsell and Ms Nguyen had not been able to account for 143 units (including 41 European pillowcases).

These figures include stock from overseas stores.

74 Further, as a part of Spotlight’s standard stocktake procedures in 2017, Ms Hounsell also identified that a total of 35 units had been sold between 16 January 2017 and 19 July 2017.

75 In August 2017, Mr Windsor brought the recall process to a close by “naming and shaming” within Spotlight the stores that had failed to comply adequately with the recall.

76 At a time that was not specified in the evidence, Spotlight also ceased doing business with Yantai.

77 In written submissions, Dempsey Group’s case was put as follows:

38. The recall was unsatisfactory.

(a) First, KOO Remy on appeared on shelves the week commencing 26 December 2016, being almost four weeks after Spotlight were put on notice of Dempsey Group’s rights on 29 November 2016.

(b) Second, Spotlight Products remained in the stores throughout the crucial Christmas/New Year sales period. On 4 and 6 January 2017, employees of Dempsey Group were able to purchase Spotlight Products in stores in Queensland and South Australia.

(c) Third, as at 13 January 2017, there were 2,734 units of Spotlight Products still in stores (albeit some in New Zealand).

(d) Fourth, thirty-three Australian stores (which is over one third of Spotlight’s Australian Stores) sold Spotlight Products between 16 January 2016 and 19 July 2017.

(e) Fifth, as at 24 August 2017, five Australian Stores still had stock on hand.

(f) Sixth, sales of the Spotlight Products continued until the 2017/2018 financial years.

39. Mr Windsor admitted in cross-examination that he discussed the Dempsey Group’s allegations with Ms Howitt and Ms Estrada within days of the Dempsey Group contacting Spotlight on 29 November 2016. However, no attempt was made to contact Yantai until 21 December 2016, over 2 1/2 weeks later, and then only to speak with a representative of Yantai with no knowledge of the issue, who could do nothing more than to obtain information from Thomas Chen. In cross-examination Mr Windsor’s explanation for the delay was that he did not deal with vendors directly and Ms Howitt’s explanation for the delay was that she assumed there were legal aspects being discussed. Over that period Spotlight failed to respond to correspondence of Dempsey Group who then referred the matter to their lawyers DLA Piper who wrote to Spotlight on 13 December 2016. A substantive response was not received from Spotlight’s lawyers until 20 December 2016.

40. More than 70% of Spotlight’s sales of the Spotlight Products occurred after it was put on notice by Dempsey Group of its rights in the Dempsey Products.

(errors in original)

Destruction of recalled Spotlight products

78 On 16 February 2018, Dempsey Group agreed to the Spotlight products (save for some samples) being destroyed prior to the completion of the proceeding, conditional upon its lawyers being provided with a “Certificate of Destruction” which would include photographs of the product delivered up for destruction, confirmation of the number of products destroyed and the date of destruction. Destruction occurred on 14 and 16 March 2018 and copies of certificates of destruction received from Superior Waste, photographs and information regarding the number of products destroyed and the dates of destruction were provided to Dempsey Group’s solicitors on 21 May 2018. Dempsey Group’s case is that the destruction was not in accordance with the agreement in that the Spotlight products were destroyed without products delivered up for destruction photographed or an accounting of the number of units that were destroyed. The “Certificate of Destruction” also stated that the type of burial was “controlled face burial – 1 meter [sic]” whereas, it was said, Spotlight had previously stated that the burial would be to a depth of two to three metres.

Did Ms Howitt know that the Spotlight products were based on Dempsey products in which Dempsey Group had copyright?

79 Dempsey Group submitted that the Court should prefer the evidence of Mr Chen over the evidence of Spotlight’s witnesses as to what occurred at the visit in April 2016.

80 It was submitted that Ms Howitt did not adequately explain why only the Dempsey products (Bosphorus and Constantinople) had a “creat[e] a design” notation on the spreadsheet when Yantai produced designs for other products shown on the first spreadsheet which were very similar to the designs on which they were based, such as the “boat sample” and a paisley design. It was submitted that her evidence – that she did not order those designs – did not explain why, in the meeting, she had not directed modifications to those samples which both made it to the first spreadsheet, the purpose of which was to reflect the design choices already made at the meeting. As the evidence established though, both samples appeared in the spreadsheet because they were discussed at the meeting and not, as asserted, because the choice of design had already been made. There was no evidence about what was discussed about those samples and, in the absence of such evidence, there is no reason to doubt the reliability of Ms Howitt’s evidence or the credibility of her explanations as to why she asked for designs to be created for the products based on the Constantinople and Bosphorus samples: in relation to Constantinople because she wanted a different patchwork design and in relation to Bosphorus because she did not want the design presented to her (which on her evidence she had not selected but which had been selected for her by Yantai’s staff).

81 Another inconsistency was said to be:

… in order to explain why she made modifications to the Bosphorus, Ms Howitt asserted, “Well, I never order from their showroom”... Yet, in relation to another two products on the [priority] Print Costing List, [Ms Howitt] contradicted this:

And - well, looking at page 824, the first picture there?---Yes.

No request to create a design?---The black and white?

Yes?---That was one of their designs.

What about the third down?---That was one of their designs.

82 The premise of that submission appears to be that the two Yantai products referred to were ordered by Spotlight without modification, but it was not established that Ms Howitt placed orders for either of those Yantai products.

83 It was further submitted that Ms Howitt’s evidence that the Rimona product was only ever used as a “colour sample” was untenable. In written submissions, it was put:

In relation to the Dempsey Group’s Rimona product, Ms Howitt admits recognizing [Bed Bath N’ Table’s] MORGAN & FINCH trade mark on the packaging but denies ever seeing the full design. Mr Chen’s evidence is that a Rimona quilt cover was displayed on a bed, at her request, in the Profile Room. Even if Mr Chen’s version is not accepted, Ms Howitt’s own photograph shows that the packaged Rimona Product which was brought to the Meeting Room had a photo insert in which the detail of the quilt is visible. In the second photograph taken by Ms Howitt of the products in the meeting room the white paper has been moved so that the photo insert is visible.

Ms Howitt’s position that the Rimona product was only ever used as a “colour sample” is untenable. In the meeting room, it was denoted with a priority number “(5)” and the word “coverlet”. It also appeared on the Priority Print Costing List with the specification “coverlet”. Moreover, Ms Howitt 'signed off’ on three documents which illustrated the Rimona Product in a [computer aided design] Drawing and/or in the MORGAN & FINCH packaging. Her explanation that Rimona was only a colour sample is unconvincing when one de-constructs the “line up” photo in the Priority Print Costing List - None of the other items in the front row have anything to do with colour and the Rimona product has a note “5 coverlet” stuck on it.

(errors in original)

84 The “line-up” photo was a reference to a photo which appears on the page of the first Yantai spreadsheet showing the three Dempsey products. There is an unfairness in the submission because the line-up photo only covers those products shown on that page of the spreadsheet and self-evidently is not a photo of the full line up of all the samples that Ms Howitt arranged. Furthermore, contrary to the submission that none of the items shown in the front row of that photo had anything to do with colour, Ms Howitt identified that the first vertical row has a computer aided design with a colour reference on top. The appearance of that colour sample at the front was consistent with her evidence that when she arranges samples the design reference is at the back and the colour reference is at the front. Consistent with Ms Howitt’s evidence, the photo also shows a design at the back which Ms Howitt had given evidence was a computer aided design of a quilt cover provided by Yantai in a colour that she did not like. The colouring of the product shown as PD-P-1348C on the first spreadsheet is also consistent with Ms Howitt’s version of events. In view of these consistencies, Ms Howitt’s evidence that she used the MORGAN & FINCH packaged product only as a colour sample for the product shown as PD-P-1348C is tenable. If only used for that purpose, Ms Howitt’s evidence that she did not see the MORGAN & FINCH product unpackaged or pay attention to the design as shown on the image of the packaging is also tenable.

85 Reliance was also placed on the email from Mr Mouradian to Ms Howitt and Mr Windsor of 23 December 2016 which, it was said, was consistent with Mr Chen’s version. In cross-examination Ms Howitt had agreed that she did not, at the time, correct Mr Mouradian. However, the evidentiary value goes no further than as a record of what Mr Mouradian was told by Mr Chen at a time after the dispute had arisen. It does not provide independent corroboration of Mr Chen’s version. I also place no weight on the fact that Ms Howitt did not correct Mr Mouradian at the time. In cross-examination Ms Howitt explained that she did not take issue with Mr Mouradian because the lawyers, by then, had become involved and she was “having as little as possible to do with any Yantai Pacific team staff members”. I accept that explanation as credible, given that by then general counsel at Spotlight was involved in the matter and lawyers had been engaged by both parties.

86 There are a number of reasons for preferring the evidence of Ms Howitt over the evidence of Mr Chen.

87 First, I accept the evidence of the Spotlight witnesses, and find, that Mr Wang was present at the meeting. There is no reason to doubt the reliability of the Spotlight witnesses’ recollection in that regard. Mr Wang was not called as a witness and there was no other evidence put before the Court which would indicate that Mr Wang was not at the visit.

88 Secondly, I place weight on what transpired when it came to the attention of Ms Howitt that the KOO Lottie design was a design in which Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright and Ms Howitt cancelled the order. Also consistently Ms Howitt gave evidence that in about early September 2016 following another buying trip and visit to Yantai’s showroom she became aware that another Spotlight purchase order was based on a design that Yantai had already sold to another Australian retailer. As a result she cancelled the relevant orders and placed revised orders. She sent an email to Mr Mouradian on about 21 September 2016 which stated, amongst other things:

As you know we are very disappointed that you have shown us designs that have already been sold to other Australian retailers.

We have raised this with you previously, so this is the second time that this has happened.

Please note that if this happens again, we will have no choice but to stop all future business with Yantai Pacific.

89 A similar incident transpired on a third occasion. Ms Howitt’s evidence was that between August 2016 and January 2017 she worked with Mr Mouradian and Mr Wang for the purpose of placing an order with Yantai for the purchase of a bed linen design which she gave the name of KOO Elite Dianna. The design was presented to her by Mr Mouradian during one of his regular meetings with Ms Howitt at Spotlight’s headquarters. She placed an order for it after requesting some alterations to darken the colour of the blue background in email correspondence. On 5 January 2017 Mr Mouradian sent her an email that stated that the original version of that design was already on the market in Australia and belonged to another retailer. In consequence Ms Howitt also cancelled that order.

90 The materiality of these three incidences within that short time frame is that on each occasion it was Yantai’s fault that purchase orders by Spotlight used designs which belonged to other retailers and on each occasion when brought to the attention of Ms Howitt she cancelled the order.

91 Thirdly, Dempsey Group’s reliance on the annotation “DTC” in the rows of the first Yantai spreadsheet sent by Yantai to Spotlight following the April 2016 meeting relating to the KOO Taj product does not advance Dempsey Group’s case about knowledge that Spotlight had or ought to have had. Ms Howitt’s evidence was that she did not know what this acronym stood for at the time and she only became aware that it was connected with Dempsey Group in the course of this dispute. The evidence of Ms Rico Estrada and Ms Frische was to the same effect.

92 Fourthly, I do not find it plausible that Mr Chen, having twice told the Spotlight buyers that Bed Bath N’ Table had copyright in the three samples, nonetheless allowed the samples to be used as the basis for the Spotlight products. Tellingly, prior to the April 2016 meeting, Yantai had been placed on notice on several occasions that Dempsey Group asserted intellectual property rights in its designs and that Dempsey Group would take action against any suppliers that supplied Dempsey Group designs to other traders. Mr Chen was cross-examined at length about his awareness of this and the documents which Yantai had received from Dempsey Group concerning that matter:

MR MERRICK: And that’s a standard-form copyright notice that Yantai received many times from Dempsey Group?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

…

MR MERRICK: Thank you. Now, just in paragraph 1 – when you read this document, you understood that to be an assertion that Dempsey Group owns all of the intellectual property in the designs it provides to Yantai.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

…

MR MERRICK: When you read that, you knew – didn’t you – that it was saying to you that you must not sell Dempsey Group’s designs to any other trader.

THE INTERPRETER: I know I can’t sell. I didn’t sell the Dempsey Group’s products.

…

MR MERRICK: Yes. And when you read that – when you received these documents, you understood that Dempsey Group was saying to you, if you contravene these obligations, Dempsey Group might make a claim against Yantai.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And having received this copyright notice on many occasions, Yantai agreed – didn’t it – to abide by these terms.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes. We agreed.

…

MR MERRICK: Yes. Now, when you received this letter in about June 2015, you understood that what was being said to you in the first paragraph is that, if you sold Dempsey Group’s designs to someone else, they might take action against you.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And can I just ask this. When you received this letter in June 2015, you understood what it meant; didn’t you.

THE INTERPRETER: I know.

…

MR MERRICK: Yes. And having read those three paragraphs to refresh your memory – when you received this letter and read those paragraphs, you understood very clearly – didn’t you – that the Dempsey Group vigorously protected its intellectual property rights?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And you understood that, if you as a supplier to the Dempsey Group were involved in selling Dempsey Group’s designs to another trader, Dempsey Group might take legal action against Yantai.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

…

MR MERRICK: Sure. I’m sorry, your Honour. We will take this in little steps, Mr Chen. I’ve taken you to three documents which set out your obligations to the Dempsey Group in relation to intellectual property. Do you recall those documents?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And you know – don’t you – that those documents require you not to sell the Dempsey Group’s designs to other traders.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And you wouldn’t knowingly sell one of the Dempsey Group’s designs to another trader, would you.

THE INTERPRETER: I won’t sell Dempsey’s design to other merchandiser.

…

MR MERRICK: I see. Thank you. Now, just want to cover off a few things with you, Mr Chen. As at April 2016, you knew that Yantai was not supposed to sell the Dempsey Group’s designs to other traders. You knew that.

THE INTERPRETER: Yes. I knew.

93 In response to questioning from the Bench, Mr Chen agreed that he was aware that the Spotlight buyers were looking at the Dempsey products and talking about changes they wanted made by Yantai and that he was aware that copyright existed in the Dempsey designs. Mr Chen gave the following answer:

THE INTERPRETER: But I did mention twice during the meeting… the buyer from the Spotlight, Katie, and asked us to change the design – for example – change the layout and some elements – for example – change this flower to another flower and take away the bird, but the colour, tone and the whole feeling shouldn’t change. And also, our relationship – because the Spotlight kept changing their buyer, our relationship wasn’t that good. They will have lots of requirements, and we felt hard to refuse. And also, we don’t know how much change we made that there won’t be any copyright issue exist in Australia; then we rely on Spotlight’s legal team and the buyer to make this decision.

94 I do not find that answer credible. Mr Chen’s account is contradicted by his own conduct. He was dealing with a Spotlight buyer with whom he had had many prior dealings and whom he knew was very experienced. Mr Chen also agreed in cross-examination that in his previous dealings with Ms Howitt she had never made a request of the type he now attributes to her and he was plainly on notice from Dempsey Group that Yantai could not sell Dempsey Group’s designs to other traders. Mr Chen agreed that he did not tell the Spotlight buyers that Yantai could not supply the Bed Bath N’ Table designs to Spotlight. Having regard to those matters, his version of events, in my view, is simply not credible.

95 The events which followed the 29 April 2016 meeting further make Mr Chen’s account of the meeting implausible. It was Mr Chen who, on 29 April 2016, following the meeting, sent the first Yantai spreadsheet to Ms Howitt by email with the statement “[t]hanks very much for your like our design and product”. Mr Chen’s account is inconsistent with sending a spreadsheet containing products that Yantai was offering to manufacture for Spotlight which Mr Chen, on his evidence, knew were products in which Dempsey Group had the copyright.

96 Further, Mr Chen advanced evidence that during the meeting, Spotlight’s buyers gave “very detailed” instructions about the products in dispute. However, there was no evidence of those instructions from Yantai. The best that Mr Chen could do was point to some (illegible) scraps of paper which appear in some of the photographs in evidence. Beyond a notation which reads “coverlet”, Mr Chen was not able to provide any evidence of these detailed instructions. This lends further support to Spotlight’s account of the meeting being more reliable.

97 Fifthly, I accept the submission that Mr Chen cannot be viewed as an impartial witness. Yantai has already lost Spotlight as a customer and the evidence was that Yantai is subject to the threat of a legal claim by Dempsey Group in relation to the subject matter of this dispute. Dempsey Group generates a significant amount of revenue (approximately US$8–9 million per annum) for Yantai and Mr Chen described Dempsey Group as a “very important customer”. Mr Chen’s email exchange with the head of Buying and Product Development at Dempsey Group, Ms Kate Mackie, in December 2016 confirmed this in terms:

MR MERRICK: Your Honour just bear with me for a moment; just back with this email, Mr Chen, I’ve just got one other thing to ask you about. You see towards the bottom of the page you say:

I am really scare of such issues. I really worried. I lost the reputation in Dempsey Company.

Do you see that?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

MR MERRICK: And what you were saying there is that you were very concerned that your company’s involvement with the Spotlight products would create an issue for you with the Dempsey Group.

THE INTERPRETER: These are two issues. First, I was concerned I don’t want these two customers have any trouble, and second, I don’t want to lose my reputation with Dempsey.

98 Sixthly, the account advanced by Mr Chen is also contradicted by an email sent by Mr Chen to Ms Mackie on 21 December 2016 in response to an email from Ms Mackie to Mr Chen sent on 19 December 2016 in which Ms Mackie advised that Dempsey Group was in dispute with Spotlight over three designs that were direct copies of Dempsey Group’s designs. Ms Mackie wrote that they thought that Spotlight had directed their supplier to copy their products but Spotlight was disputing that there was copyright infringement and had advised Dempsey Group that Yantai was the supplier of their versions of Dempsey Group’s designs which were shown to them in a visit to the Yantai showroom. Ms Mackie sought an explanation as to how this came to be “when you are aware of how aggressively we protect our Intellectual Property”. In his reply email, Mr Chen stated:

I am very sorry for that. That is my company problem

I just called back to China. Checked with our spotlight team. The manager said we supplied those three designs to Spotlight on Sep. and He also mentioned DTC team Frank asked such question weeks ago. But he didn’t tell the truth story to Frank. He doesn’t know the copy right is a serious problem.

Spotlight came to yantai at end of April and they saw your products in our show room. And they wanted that. Our team told them that designs below to DTC .but they give some instruction and idea to change. Our guy just followed.

am very apologise that is my management problem.

(errors in original)

99 Consistently in the 23 December 2016 email from Mr Mouradian to Spotlight, Yantai also took responsibility for submitting artworks that were too close to the Bed Bath N’ Table designs.

100 The weight of the evidence supports Spotlight’s account rather than Mr Chen’s account. The reliability of Ms Howitt’s evidence was corroborated by Ms Frische and Ms Rico Estrada to the extent that they were able to recall events or participated in the meeting. On Mr Chen’s account, Ms Gao and Mr Yuan were both present at the meeting but neither of them gave evidence and the failure to call them was unexplained. In the circumstances it is reasonable to draw a Jones v Dunkel inference from the failure to call them as witnesses.

101 Accordingly I find that the Spotlight buyers did not know that the samples on which the Spotlight products were based were Dempsey products which held the copyright in those designs until put on notice on 29 November 2016.

ISSUE 1: whether Dempsey Group has established that it is the owner of the Constantinople artistic work

102 The issue here concerns the ownership of the Constantinople artistic work (s 35 of the Act). Dempsey Group’s case is that it owns the copyright in the Constantinople artistic work as a result of the assignment of copyright in an artistic work denoted as “AW 48778GT” created by Artwork Design (M/C) Limited, a UK company, which Artwork Design assigned to Dempsey Group pursuant to a deed of assignment dated 10 February 2014.

103 It was submitted for Spotlight that the Constantinople artistic work upon which Dempsey Group sues is different to the assigned work and there was no evidence about the authorship of the Constantinople artistic work. The only evidence put forward about this matter was in paragraph 42 of the affidavit of Ms Mackie sworn 14 September 2017 which was struck out on the basis that it was opinion evidence and speculative.

104 Dempsey Group argued that it is apparent from an inspection of the Constantinople product that the assigned artwork is repeated in the Constantinople product with inconsequential changes in scale. Dempsey Group argued in the alternative that if the differences have resulted in a new work being created, it is reasonable for the Court to infer that the changes were done by the Dempsey Group in-house design team and the Court should find on that basis that Dempsey Group owns the copyright in the Constantinople artistic work.

105 Although the assigned copyright artwork can be seen to be employed in the Constantinople product, the Constantinople product contains more detail which does not appear in the copy of the signed copyright artwork attached to the deed of assignment. The Constantinople product displays more features than the features displayed in the copy of the assigned copyright artwork annexed to the deed of assignment. I am not satisfied on the visual inspection that the Constantinople product is just a scaled down version of the assigned artwork or that the differences are inconsequential as submitted by Dempsey Group. However in my view it is reasonable to infer that the changes to the design were effected by Dempsey Group’s in-house design team. Although the deed of assignment was not made until February 2014, the evidence was that Mr Dempsey and Ms Mackie visited Artwork Design’s store at the Heimtextil trade fair in Germany in January 2013 and selected the artwork (and other artwork) for which Artwork Design sent an invoice to Ms Mackie at Bed Bath N’ Table dated 14 January 2013 and that the Constantinople product was sold in Bed Bath N’ Table stores from October 2013. The evidence left unexplained as to why the deed of assignment was not entered into until February 2014 and not when the invoice was actually paid, but the absence of that evidence does not detract from the inference that the changes were made by the Dempsey Group in-house design team. There is nothing in the evidence which would suggest that the changes were made by some third party. Accordingly I find on the evidence that Dempsey Group is the owner of the Constantinople artistic work.

ISSUE 2: whether the Spotlight products reproduce a substantial part of any of Dempsey Group’s artistic works in suit

106 The right to reproduce an artistic work in a material form and communicate the work to the public is the exclusive right of the copyright owner pursuant to s 31(1)(b) of the Act, and, by s 36(1) of the Act, the copyright in an artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia any of the acts comprised in the copyright, or authorises another to do so. By s 14(1), acts done in relation to a substantial part of the work are deemed to be done in relation to the whole. The combined effect of those sections is that only Dempsey Group (or someone authorised by it) has the right to reproduce the Dempsey Group artistic works, or a substantial part of them, in a material form or to communicate them to the public.

107 The following principles of law were not in controversy:

(a) copyright in an original work protects the particular form of expression used by the author, rather than the underlying idea: IceTV v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458 at [28] (“IceTV”);

(b) the copying must be sufficiently substantial to constitute infringement;

(c) the legal standard is imprecise;

(d) the question of whether a substantial part of a copyright work has been taken is a question of fact to be determined in the circumstances of each case: IceTV at [32];

(e) whether a substantial part of a copyright work has been taken is to be assessed in a qualitative sense rather than quantitatively: IceTV at [30]; and

(f) in determining whether the quality of what is taken makes it a substantial part, it is important to consider whether the taken portion is an essential or material part of the work, and the essential or material features should be ascertained by reference to the elements that made the work an original artistic work: Elwood Clothing Pty Ltd v Cotton On Clothing Pty Ltd (2008) 172 FCR 580 (“Elwood”) at [66].

108 Spotlight argued that the case put by Dempsey Group did not focus sufficiently on the precise form of expression of the artistic works but rather focused on the Spotlight products conveying a similar feel to the artistic works. It was argued that in approaching the matter in this way, Dempsey Group was, in effect, seeking to stretch copyright to protect the idea of its products rather than their particular form of expression. Dempsey Group argued that, contrary to this submission, the Full Court in Elwood noted that elements which contributed to the “look and feel” of an artistic work may be protectable aspects of expression. At [76]–[78] the Full Court reasoned: