FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

H. Lundbeck A/S v Sandoz Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1797

ORDERS

First Applicant LUNDBECK AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 070 094 290) Second Applicant | ||

AND: | SANDOZ PTY LTD (ACN 075 449 553) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 21 November 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to order 2, until 5.00pm on 28 November 2018, pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice under s 37AG(1)(a), there be no disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the reasons for judgment delivered on the date of this order in proceedings NSD 647 of 2014 and NSD 826 of 2016 (Proceedings) to any person other than to the external solicitors, expert accounting witnesses, and counsel for the parties in the Proceedings and Lundbeck In-house Counsel and Sandoz In-house Counsel (as defined in the Confidentiality Agreement dated 30 May 2017).

2. The reasons for judgment may be provided to the Patent Office in relation to the Application for Licence to Exploit an Invention made by the Respondent to the Patent Office on 18 December 2013, provided that the Commissioner of Patents makes a direction under regulation 4.3(2)(a) and / or 4.3(2)(b) that the reasons for judgment will not be open to public inspection pending the making of any confidentiality orders referred to in order 6.

3. By 4.00pm on 28 November 2018 any party wishing to claim that any part of the reasons for the judgment should be subject to a further confidentiality order is to notify the Associate to Jagot J and the other parties, by email of the claim including:

(a) details of the matter claimed to be confidential;

(b) a short statement of the reasons the matter is said to be confidential; and

(c) a statement identifying whether the claimant consents to the confidentiality claim being determined by Jagot J on the basis of the email or seeks an oral hearing.

4. If no notice by email is received in accordance with order 3, the reasons for judgment will be published forthwith.

5. If notice is received in accordance with order 3, the reasons for judgment will be published forthwith with the claimed confidential matter redacted pending determination of the confidentiality claim.

6. The parties are to confer and, by 4.00pm on 5 December 2018, are to propose in a joint email (including agreed and disagreed matters) to the Associate to Jagot J further directions to enable the matter to be finalised, including orders to enable the expert accounting witnesses to confer and provide a further joint report, if necessary, in respect of any outstanding issues having regard to the reasons for judgment.

7. Pursuant to rule 36.03(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the time within which a party may file and serve any notice of appeal from judgment in these proceedings be extended to and for a period of 21 days after the publication of the reasons for judgment pursuant to orders 4 or 5, or the date of the determination of any outstanding issues raised by the expert accounting witnesses in any further joint report pursuant to order 6, whichever is later.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NSD 824 of 2016 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | CNS PHARMA PTY LTD (ACN 121 515 400) Applicant | |

AND: | SANDOZ PTY LTD (ACN 075 449 553) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 21 November 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to order 2, until 5.00pm on 28 November 2018, pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice under s 37AG(1)(a), there be no disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the reasons for judgment delivered on the date of this order in proceedings NSD 647 of 2014 and NSD 826 of 2016 (Proceedings) to any person other than to the external solicitors, expert accounting witnesses, and counsel for the parties in the Proceedings and Lundbeck In-house Counsel and Sandoz In-house Counsel (as defined in the Confidentiality Agreement dated 30 May 2017).

2. The reasons for judgment may be provided to the Patent Office in relation to the Application for Licence to Exploit an Invention made by the Respondent to the Patent Office on 18 December 2013, provided that the Commissioner of Patents makes a direction under regulation 4.3(2)(a) and / or 4.3(2)(b) that the reasons for judgment will not be open to public inspection pending the making of any confidentiality orders referred to in order 6.

3. By 4.00pm on 28 November 2018 any party wishing to claim that any part of the reasons for the judgment should be subject to a further confidentiality order is to notify the Associate to Jagot J and the other parties, by email of the claim including:

(a) details of the matter claimed to be confidential;

(b) a short statement of the reasons the matter is said to be confidential; and

(c) a statement identifying whether the claimant consents to the confidentiality claim being determined by Jagot J on the basis of the email or seeks an oral hearing.

4. If no notice by email is received in accordance with order 3, the reasons for judgment will be published forthwith.

5. If notice is received in accordance with order 3, the reasons for judgment will be published forthwith with the claimed confidential matter redacted pending determination of the confidentiality claim.

6. The parties are to confer and, by 4.00pm on 5 December 2018, are to propose in a joint email (including agreed and disagreed matters) to the Associate to Jagot J further directions to enable the matter to be finalised, including orders to enable the expert accounting witnesses to confer and provide a further joint report, if necessary, in respect of any outstanding issues having regard to the reasons for judgment.

7. Pursuant to rule 36.03(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the time within which a party may file and serve any notice of appeal from judgment in these proceedings be extended to and for a period of 21 days after the publication of the reasons for judgment pursuant to orders 4 or 5, or the date of the determination of any outstanding issues raised by the expert accounting witnesses in any further joint report pursuant to order 6, whichever is later.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

1. The claims

1 These reasons for judgment explain why I have decided that the applicants’ claims for patent infringement and misleading and deceptive conduct against the only remaining respondent should succeed and be subject to an award of damages calculated in a manner generally consistent with the approach of the accountant called by the applicants, but subject to a discount of 30% to take account of all relevant risks associated with the past hypothetical cash-flows which underlie the assessment of damages.

2. The essential facts

2 H Lundbeck A/S (referred to as Lundbeck A/S or Lundbeck DN) is the patentee of Australian patent 623144 (the 144 patent or the Lexapro patent). Lundbeck Australia Pty Ltd (referred to as Lundbeck AU), a subsidiary of Lundbeck A/S, claims to be the exclusive licensee of the 144 patent. Lundbeck AU sells Lexapro and Cipramil in Australia which are manufactured by and purchased from Lundbeck A/S. CNS Pharma Pty Ltd is a subsidiary of Lundbeck AU which sells a generic version of Lexapro in Australia known as Esipram which is also manufactured by and purchased from Lundbeck A/S.

3 Lundbeck A/S and Lundbeck AU, when there is no need to distinguish between them, are referred to in these reasons as Lundbeck.

4 The 144 patent is dated 13 June 1989 and thus its term of 20 years under s 67 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) meant that, if the term was not extended, the patent would expire on 13 June 2009.

5 Lundbeck A/S applied to extend the term of the 144 patent on 22 December 2003. The Commissioner of Patents granted the extension so that the 144 patent would not expire until 13 June 2014. Alphapharm Pty Ltd contended to the Commissioner that the extension was invalid and that the only extension which could have been granted was until 9 December 2012. The Commissioner agreed with Alphapharm’s contention and scheduled a hearing to decide if the Commissioner should amend the extended term to 9 December 2012.

6 Alphapharm commenced a proceeding to revoke claims 1 to 6 of the 144 patent and to remove the extension of term until 13 June 2014 from the Register of Patents. Lundbeck commenced a proceeding to prevent the Commissioner from amending the Register by contending that a relevant regulation was invalid. Lundbeck also cross-claimed against Alphapharm for infringement of the 144 patent.

7 On 1 March 2006 Lindgren J dismissed Lundbeck’s application contending invalidity of the regulation: H Lundbeck A/S v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCA 163; (2006) 150 FCR 269. In so doing Lindgren J exposed the competing positions of the parties. Lundbeck relied on the registration of escitalopram oxalate on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on 16 September 2003 as the relevant date for the extension. This is known as the Lexapro registration (Lexapro being the brand name of Lundbeck’s escitalopram oxalate product). Alphapharm contended that the relevant date was that on which citalopram hydrobromide was registered on the ARTG, being 9 December 1997. This is known as the Cipramil registration (Cipramil being the brand name of Lundbeck’s citalopram hydrobromide product). As Lindgren J explained at [13]:

Subsection 71(2) of the Act provides that an application for an extension of term must be made during the term of the patent and within six months of the latest of the following dates:

‘(a) the date the patent was granted;

(b) the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain, or consist of, any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subs 70(3);

(c) the date of commencement of [s 71].’

In this case, on either of the competing views the latest of those three dates is that referred to in para (b). If the date referred to in para (b) was, as Lundbeck contends, 16 September 2003, Lundbeck had until 16 March 2004 in which to apply for the extension, and therefore its application made on 22 December 2003 was within time. If, on the other hand, the date referred to in para (b) was, as Alphapharm contends, 9 December 1997, Lundbeck had only until 9 June 1998 in which to apply for an extension, and, therefore, its application on 22 December 2003 was made out of time.

8 On 19 May 2006 the Commissioner decided to amend the Register “to insert the correct extension of the term of the patent, that is 9 December 2012”: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2006] APO 18; (2006) 69 IPR 629 at [35].

9 In the meantime or thereafter, more proceedings were commenced. Arrow Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd brought a claim for revocation of claims 1 to 6 of the 144 patent and rectification of the Register by removing the extension of term and recording that the 144 patent will expire on 13 June 2009 or, in the alternative, 9 December 2012. Sandoz Pty Ltd also brought a claim for revocation of claims 1 to 6 of the 144 patent and rectification of the Register by removing the extension of term. Sandoz’s proceeding was settled and discontinued. Lundbeck A/S and Lundbeck AU entered into a deed of settlement with Sandoz in February 2007.

10 Lindgren J determined the Lundbeck, Alphapharm and Arrow proceedings on 24 April 2008: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008] FCA 559; (2008) 76 IPR 618 (Lindgren J judgment). These proceedings are referred to in various documents and submissions as the Alphapharm proceedings. In short, Lindgren J dismissed Alphapharm’s and Arrow’s claims for revocation of all but claim 5 of the 144 patent and found that Alphapharm had infringed claims 1, 3, and 6 of the 144 patent. He also held that the extension of term was invalid as the relevant date under s 71(2) was the date of the Cipramil registration, with the consequence that reference to any extension of term of the 144 patent should be removed.

11 Lindgren J made orders on 19 June 2008. By order 6 Lindgren J ordered rectification of the Register to remove any reference to an extension of term of the 144 patent. By order 7, order 6 was stayed pending determination of an appeal to the Full Court on Lundbeck giving undertakings the terms of which are not now relevant.

12 On 11 June 2009 the Full Court (Emmett, Bennett and Middleton JJ) dismissed Lundbeck’s appeal against order 6 concerning removal of any reference to an extension of term of the 144 patent. The majority (Bennett and Middleton JJ) also dismissed Alphapharm’s and Arrow’s claims for revocation of claims 1 to 6: see H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 70; (2009) 177 FCR 151 (FFC#1).

13 The Full Court made orders on 12 June 2009 which stayed order 6 of Lindgren J’s 19 June 2008 orders until determination of any application for special leave to appeal to the High Court on the basis of Lundbeck undertaking not, before determination of any such application, commencing or threatening proceedings against any person for infringement of the 144 patent in respect of conduct engaged in after 13 June 2009.

14 Accordingly, as at 12 June 2009:

(1) The Full Court had held in FFC#1 that all purported extensions of term of the 144 patent, be it to 9 December 2012 or 13 June 2014, were invalid.

(2) Order 6 had been made removing any reference to an extension of the term of the 144 patent from the Register.

(3) Order 6 had been stayed on the basis of Lundbeck not commencing or threatening to commence infringement proceedings for conduct after 13 June 2009.

(4) Without any extension of term of the 144 patent, that patent would expire at the end of its 20 year term on 13 June 2009.

15 Also on 12 June 2009 Lundbeck A/S applied for an extension of time in which to make an application to extend the term of the 144 patent to 9 December 2012 based on the Cipramil registration. For this purpose the time for making the extension of term application had to be extended to 12 June 2009, being the date on which Lundbeck A/S also applied for the extension of term of the 144 patent to 9 December 2012.

16 On 13 June 2009, pursuant to s 67 of the Patents Act, the 20 year term of the 144 patent ended.

17 From Monday, 15 June 2009 onwards, Apotex Pty Ltd, Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd and Sandoz supplied generic escitalopram oxalate products in Australia.

18 On 11 December 2009 the High Court refused the applications for special leave to appeal.

19 On 9 February 2010 the Register was rectified to remove reference to the extension of term of the 144 patent.

20 Alphapharm, Apotex and Sandoz opposed the extension of time application before the Commissioner, as did Sigma. Sigma was subsequently acquired by the Aspen group of which Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd is part.

21 On 1 June 2011 the Commissioner decided to extend the time for the making of an application to extend the term of the 144 patent based on the Cipramil registration until 9 December 2012: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2011] APO 36; (2011) 92 IPR 628.

22 Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen appealed against the Commissioner’s decision to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (the AAT). On 4 December 2012, the AAT affirmed the Commissioner’s decision granting the extension of time: Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2012] AATA 851; (2012) 132 ALD 648.

23 On 18 November 2013 the Full Court dismissed the appeals against the AAT’s decision: Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2013] FCAFC 129; (2013) 216 FCR 508 (FFC#2).

24 In the meantime Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen had filed oppositions to the extension of term of the 144 patent and had applied under s 223(9) of the Patents Act for licences to exploit the 144 patent during its extended term, should its term be extended.

25 On 25 June 2014 the Commissioner granted the extension of term of the 144 patent to 9 December 2012: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2014] APO 41; (2014) 109 IPR 323.

26 On 26 June 2014 Lundbeck commenced infringement proceedings against Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen. On 30 May 2016 CNS Pharma also commenced proceedings against those entities seeking declarations that, by the sale, offering for sale and supply of escitalopram products during the term of the 144 patent, they engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct. Accordingly, CNS Pharma sought damages for the loss it claims to have suffered during the patent term as a result of the alleged acts of infringement by the generic parties.

27 Having granted special leave to appeal, on 5 November 2014 the High Court dismissed Alphapharm’s appeal against the Full Court’s orders dismissing the appeal to it by a 3:2 majority: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2014] HCA 42; (2014) 254 CLR 247.

28 Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen appealed against the Commissioner’s decision to extend the term of the 144 patent and, on 6 November 2014, Rares J dismissed this appeal: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2014] FCA 1185; (2014) 110 IPR 59 (the Rares J judgment).

29 Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen appealed against Rares J’s orders dismissing the appeal and on 22 September 2015 the Full Court dismissed that appeal: Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2015] FCAFC 138; (2015) 234 FCR 306 (FFC#3).

30 Alphapharm, Apotex, Sandoz and Aspen applied for, but on 11 March 2016 were refused, special leave to appeal to the High Court against the orders in FFC#3.

31 On 5 August 2016 Lundbeck A/S applied for an order that the Commissioner had no power to determine the applications for licences under s 223(9) of the Patents Act.

32 On 21 October 2016 I held that Alphapharm and Aspen were not estopped or precluded by the doctrine of abuse of process from raising the status of Lundbeck AU as an exclusive licensee or not of the 144 patent: H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1232.

33 On 3 February 2017 Beach J held that the Commissioner did have the power to determine the licence applications and made declarations reflecting this conclusion: H Lundbeck A/S v Commissioner of Patents [2017] FCA 56; (2017) 249 FCR 41.

34 Before the first tranche of the hearing of the current matters commenced, the claims against and by Alphapharm were discontinued. The claim against Aspen was also subsequently discontinued after the first tranche of the hearing. During the second tranche of the hearing, the claims between Lundbeck and Apotex settled. As a result, the sole remaining respondent is Sandoz.

35 The fact that Sandoz alone remains as a respondent creates some practical difficulty. To explain, Sandoz did not challenge the validity of the 144 patent, but it did defend Lundbeck’s infringement proceedings on various grounds including the proper construction of the 144 patent. In so doing Sandoz relied on Apotex’s expert evidence and submissions. Apotex’s submissions about construction were part of its case that the 144 patent is invalid or, if valid, should be construed in a manner which meant that Apotex’s products (and thus also Sandoz’s products) did not infringe. As noted, however, the proceedings against Apotex settled, but only after the hearing in relation to the invalidity and the proper construction of the 144 patent.

36 I sought clarification of Sandoz’s position. Sandoz said that it pressed its non-infringement argument based on the proper construction of the 144 patent as articulated by Apotex, but did not contend the patent was invalid as a result of any particular construction.

37 The difficulty is that given that the hearing took place in the way that it did it is not possible to identify the construction argument other than in the context of Apotex’s invalidity argument. As a result, in these reasons for judgment I refer to and deal with Apotex’s invalidity argument, but I do so only for the purpose of explaining my conclusions about Sandoz’s construction and associated non-infringement argument. Sandoz’s construction argument relied on one aspect of Apotex’s case, which may be described as the “separated, isolated or pure” (+)-enantiomer argument. Sandoz did not adopt Apotex’s so-called “molecule” construction argument. However, in order to understand the competing constructions, and thus Sandoz’s position as the sole remaining respondent, it is necessary to explain all aspects of Apotex’s arguments.

38 Sandoz also adopted other submissions of various generic parties about certain issues. For ease of reference I have attributed all of those submissions in these reasons to Sandoz but, in reality, many of the submissions were made by one or other generic party before the cases against them were settled and which Sandoz adopted.

3. Apotex’s challenge to validity of the 144 patent

3.1 The grounds of the challenge

39 During the first tranche of the hearing, Apotex contended that claims 1 and 3 of the 144 patent were invalid on three grounds.

40 The first ground was that the invention claimed in claims 1 and 3 was not a patentable invention as the invention was not novel as required by s 18(1)(b)(i) of the Patents Act by reason of the publication of Australian Patent No. 509445 (the 445 or Citalopram patent) on or about 13 July 1978.

41 The second ground was that if claim 1 of the 144 patent, on its proper construction, is limited to the “separated or isolated or pure (+)-enantiomer of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1-(4'-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile with nothing else present”, then the invention claimed in claims 1 and 3 is not fairly based on matter described in the specification as required by s 40(3) of the Patents Act.

42 The third ground was that if claim 1 of the 144 patent, on its proper construction, is not so limited then the term “(+) enantiomer of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1-(4'-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile” in claim 1 is not clear and claims 1 and 3 therefore do not comply with s 40(3) of the Patents Act.

43 Although Apotex’s cross-claim referred to the 1990 Patents Act, as it explained in its written submissions, validity, but not infringement, is to be decided under the provisions of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) (the 1952 Act). This was not in dispute so it suffices to adopt Apotex’s submission about this issue as follows:

Lindgren J [in the Lindgren J judgment] explained the continued relevance of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) (1952 Act) at [54]-[55]. This was clarified by Middleton J in Eli Lilly and Company Limited v Apotex Pty Ltd [[2013] FCA 214] (2013)100 IPR 451 at [7]-[18], referring in particular to reg 23.26 of the Patents Regulations 1991, and to ss 233 and 234 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Act).

For the reasons noted by Middleton J at [16], by a combination of s 228(7) and reg 23.26(2), when a patent has been granted under the Act on an application made under the 1952 Act, the 1952 Act applies to validity but not to infringement.

44 To the extent relevant to the present matter, the requirement that an invention be novel, and that claims be clear and fairly based on the matter described in the specification under the 1952 Act involve the same considerations as under the 1990 Act.

45 It is unnecessary to record the uncontroversial scientific facts about stereochemistry, enantiomers, citalopram and escitalopram. There is no material dispute about these matters.

46 Nor is it necessary to summarise the 144 and 445 patents. This exercise has been done repeatedly in the previous decisions, which are an essential part of the background to the current dispute.

3.2 Construction of claim 1

47 The Lindgren J judgment identifies the background to the Alphapharm proceedings in uncontroversial terms at [1] to [8]. His Honour said:

1 These four proceedings, which were heard together, relate to Australian patent No 623144 (the Patent or the Australian Escitalopram Patent) held by H Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck), a Danish pharmaceutical company.

2 Lundbeck applied for the Patent on 13 June 1989. The application was a Convention application and was said in the application to be based on application No 8814057 for a patent made in the United Kingdom on 14 June 1988 (the UK Escitalopram Patent – see [79] below). The title of the invention in the Patent is: “(+)-Enantiomer of citalopram and process for the preparation thereof”.

3 Citalopram is a molecule patented by Lundbeck which is used for the treatment of depression. Citalopram is a chiral molecule, a racemic mixture (or racemate) comprising in equal measure two enantiomers. Enantiomers are non-superimposable mirror images of each other. They are designated “(+)” or “(–)” based on a particular physical property referred to below, and “R” or “S” based on their three-dimensional structure. The correlation between the (+) or (–) and the R or S designations can only be determined, however, through experimentation.

4 In the case of citalopram, experimentation subsequent to the priority date has shown that the (+)-enantiomer is in fact the S-enantiomer. It is commonly referred to as “S-citalopram”, and has the International Nonproprietary Name “escitalopram”.

5 The Patent discloses processes for obtaining escitalopram, and data showing that (+)-citalopram is therapeutically more active than citalopram itself, and more than 100 fold more active than (-)-citalopram.

6 The 20 year term of the Patent was due to expire on 13 June 2009. The term has, however, been extended as discussed at [28] ff below.

7 Citalopram is an invention claimed in Australian patent No 509,445 (the Australian Citalopram Patent) dated 5 January 1977, the term of which was sixteen years commencing on that date. The Australian Citalopram Patent was, in turn, said in the application to be based on the application No 1486/76 for a patent filed in Great Britain on 14 January 1976 (the UK Citalopram Patent). The title of the invention in the Australian Citalopram Patent is “phthalanes”, a class of compounds that includes citalopram.

8 In various ways, the proceedings before the Court raise issues concerning the relationship between citalopram and escitalopram. Broadly, the issues can be separated into those that relate to patentability (raised in the proceedings brought by Alphapharm Pty Ltd (Alphapharm) and Arrow Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (Arrow) for revocation of the Patent), infringement (a cross-claim in Alphapharm’s revocation proceeding) and regulatory aspects (all four proceedings).

48 Lindgren J identified the claims of the 144 patent as follows:

9 The Patent comprises six claims. …

10 The six claims are as follows:

1. (+)-1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1-(4’-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile and non-toxic acid addition salts thereof.

2. The pamoic acid salt of (+)-1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1-(4’-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile.

3. A pharmaceutical composition in unit dosage form comprising as an active ingredient, a compound as defined in claim 1, together with a pharmaceutically accepta[ble] carrier or excipient.

4. A pharmaceutical composition in unit dosage form comprising, as an active ingredient, the compound of claim 2, together with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier or excipient.

5. A pharmaceutical composition in unit dosage form, according to claim 3 or 4, wherein the active ingredient is present in an amount from 0.1 to 100 milligram per unit dose, together with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier or excipient.

6. A method for the preparation of the compound of claim 1, which comprises:

(a) reacting a compound of the formula

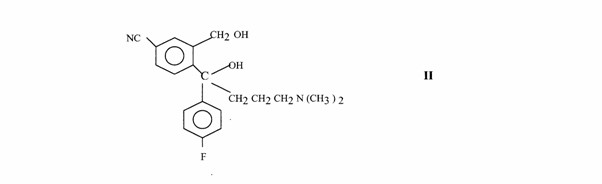

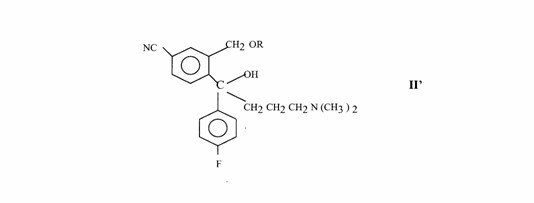

with an enantiomerically pure acid derivative as an acid chloride, anhydride or labile ester, subsequently separating the resolved intermediate enantiomer for (+)-citalopram having the formula

wherein R is a labile ester group; by HPLC or fractional crystallization, and then treating said intermediate enantiomer with strong base: or

(b) reacting a compound of formula II with the enantiomer of an optically active acid affording the pure enantiomer salt of the compound of formula II for (+)-citalopram, and subsequently performing ringclosure via a labile ester by reacting the pure enantiomer of formula II as a base with an activated acid with simultaneous addition of a base and, if desired, transferring the (+)-citalopram obtained to a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof.

49 Lindgren J construed claim 1 of the 144 patent to mean (+)-citalopram. He stated his conclusion as follows:

116 The symbol (+)- in claim 1 (and in claim 2) indicates the particular enantiomer that is distinguished by the feature of rotating plane-polarised light to the right (under standard conditions – see Section G below). The property of rotating plane-polarised light to the right (clockwise) or to the left (anticlockwise) which distinguishes one enantiomer from the other and each from the racemate, is able to be detected only when that enantiomer is present other than as a part of the racemate. This is because when in a racemic mixture, the polarisation of light by each enantiomer is “cancelled out” by the other enantiomer, and there is thus no net polarisation of light. The skilled addressee in 1988 would have understood claim 1 to refer specifically to (+)-citalopram.

117 In the absence of a context permitting otherwise, the skilled addressee would not have understood the claim to the invention of (+)-citalopram to refer to that compound merely as part of the unresolved racemate. Rather, the skilled addressee would have understood the claim to the invention of (+)-citalopram to refer to that compound as something that had an existence independent of that of the racemate.

50 His Honour’s reasoning included the following:

118 The only context that I take into account in arriving at this conclusion is that it was part of common general knowledge:

• that racemates contained in equal parts (+) and (–) enantiomers;

• that the enantiomers of a racemate were potentially separable, and it was a possibility that an enantiomer might have a stable existence as a compound distinct from being part of the racemate;

• that some racemates had in fact been resolved into their separate enantiomers; and

• that racemates were commonly represented by the symbol (±) to indicate the presence of both enantiomers.

119 It is not that the (+)-citalopram compound does not exist when it is part of the racemate. The skilled addressee would understand that it exists whether a part of the racemate or apart from it, and that the purpose of the (+) symbol is only to distinguish it from the (–)-enantiomer and from its being merely part of the racemate or of some other mixture. The (+) or (–) symbol, devoid of any context suggesting otherwise, implies distinctness from the racemate.

…

123 So, the unqualified reference to the (+)-enantiomer of citalopram in claim 1 refers to something different from that enantiomer as an indistinguishable part of the unresolved racemate.

51 Lindgren J noted the expert evidence relevant to construction at [128]–[140], which founded his Honour’s conclusion at [138] that “chemists at the priority date and now would understand the bare formula of claim 1 to require a compound that was at least 95% pure (+)-citalopram”. Otherwise, in reaching his conclusions as to the proper construction of claim 1, Lindgren J had regard to the body of the specification at [141]–[142]. After rejecting various submissions as to the relevance of other matters, Lindgren J said at [153]:

In summary, the reference in claim 1 to (+)-1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1-(4’-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile is a specific reference to the enantiomer of citalopram that rotates plane-polarised light to the right, and, there being no context suggesting a different possibility, is not apt to refer to the (+)-enantiomer merely as present in the racemate.

52 In FFC#1 Bennett and Middleton JJ were in the majority and Emmett J was in dissent.

53 Apotex argued that the decision of the majority about construction of claim 1, and that of Lindgren J, depended on expert evidence. Thus Apotex pointed to Bennett J’s observation in FFC#1 at [150] that the “[t]he primary judge was entitled to accept the evidence that the skilled addressee would read claim 1 as referring to the isolated (+)-enantiomer. In the context of the whole of the specification, this was in contrast to the (+)-enantiomer as present in the racemate or in a mixture with the (–)-enantiomer” and to what Middleton J said at [252]:

Claim 1 simply identifies the substance (+)-enantiomer. The construction I prefer does not involve reading into claim 1 a limitation of “independently existing” or “existing independently” of the racemate any more than it expands the context in which the (+)-enantiomer is to be found. The mere reference to (+)-enantiomer in claim 1 without more indicates that it is the separated or the isolated enantiomer that is claimed. In other words, it is implicit in the way claim 1 is worded, where the Patent is entitled “(+)-Enantiomer of Citalopram and process for the preparation thereof”, that the claim is only to the isolated or separated (+)-enantiomer.

54 I am not persuaded that the Lindgren J judgment or FFC#1, insofar as the issue of construction is concerned, depended on expert evidence. As Lindgren J’s reasons disclose, he relied on certain contextual matters at [118], but those matters were not in dispute on the evidence. He also had regard to the body of the specification. But his conclusion did not depend on resolving any contested issue of expert evidence. Nor should anything in the reasoning of Bennett or Middleton JJ in FFC#1 be understood as suggesting to the contrary.

55 To the extent [131]–[138] of Bennett J’s reasons were relied upon by Apotex, it is apparent that her Honour was recording common ground other than with respect to the 95% purity issue to which Lindgren J referred at [138].

56 Given this, I am not persuaded by Apotex’s submissions that the construction of claim 1 reached in FFC#1 depended on expert evidence, with the consequence that I am not bound by that construction. To the contrary, I consider Lundbeck to be correct that claim 1 has been conclusively construed in FFC#1 as Lindgren J proposed in [153] of the Lindgren J judgment. In reaching this conclusion Bennett J, having confirmed that Lindgren J was correct at [150], said this at [151]:

That is, claim 1 is to the separated or isolated or pure (+)-enantiomer.

57 These words “separated or isolated or pure” have taken on their own life in this matter but it is best to understand now that Bennett J was doing nothing more than affirming that Lindgren J’s conclusion at [153] was correct.

58 In FFC#3, to which Apotex and Sandoz were parties, the Full Court (Bennett, Nicholas and Yates JJ) had to revisit the issue of construction. FFC#3 involved an appeal against the Rares J judgment in which Rares J had dismissed the generic parties’ appeal against the Commissioner’s decision extending the term of the 144 patent until 9 December 2012. Rares J recorded the generic parties’ case on appeal at [6] of the Rares J judgment:

(1) the pharmaceutical substance per se disclosed in claim 1 of the patent was the pure, isolated or separated form of the molecule, being the (+)-enantiomer, for the purposes of s 70(2) of the Act, and that that pure form of the molecule was not included in the goods registered as “CIPRAMIL Citalopram hydrobromide 20mg tablet blister pack” on the ARTG with a start date of 9 December 1997 for the purposes of s 70(3). The Cipramil tablets were produced as an exploitation of the properties of the racemate (the per se issue);

(2) the requirement of s 70(4) of the Act, that the term of the patent had not previously been extended, could not be satisfied because the term of the patent in suit had been previously extended to 13 June 2014 by the delegate and that extension had been recorded in the Register of Patents on 17 June 2004, although, subsequently, on 19 June 2008, Lindgren J had ordered under s 192 of the Act that the Register be rectified by removing the extension of time, and the Full Court upheld that decision (the prior extension issue);

(3) the delegate erred because he exceeded his function of deciding the opposition under s 75(2) by also proceeding to grant the challenged extension of time under s 76(1)(b) of the Act, before this appeal had been determined (the erroneous grant issue).

59 Section 70 of the Patents Act, as referred to in these paragraphs provides that:

(1) The patentee of a standard patent may apply to the Commissioner for an extension of the term of the patent if the requirements set out in subsections (2), (3) and (4) are satisfied.

(2) Either or both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

(a) one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

(b) one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

(3) Both of the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances:

(a) goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods;

(b) the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

(4) The term of the patent must not have been previously extended under this Part.

…

60 In FFC#3 the Full Court had to deal with the Lindgren J judgment and FFC#1 (referred to in FFC#3 as the Decision). After referring to claim 1 of the 144 patent, the Full Court in FFC#3 said at [15]:

In essence, in the Decision, the majority concluded that the claim was to the separated enantiomer and that the claim was not anticipated by the Cipramil Patent which described the racemate, as the racemate did not describe or disclose ‘the pure or isolated (+)-enantiomer’, nor was there anything to tell the skilled addressee to resolve the racemate into the two enantiomers, or how to do so. The majority also concluded that the racemate “contained” the (+)-enantiomer for the purposes of s 70(3)(a) of the Act.

61 The Full Court also referred in [18] to “some relevant aspects of the background chemistry which are not in dispute”, in these terms:

• (+)-citalopram is the (+)-enantiomer of citalopram;

• (+)-citalopram is also known as (S)-citalopram or escitalopram;

• Citalopram is a racemic mixture that contains equal amounts of the (+) and (–) enantiomers of citalopram;

• Citalopram and escitalopram are different chemical entities with different physical properties and different pharmacological activities.

62 The undisputed nature of this evidence is confirmed by the following statement of the Full Court at [19]:

The background chemistry has been described in some detail in the Decision and does not need to be repeated.

63 This accords with my conclusion above that, insofar as expert evidence was relevant to claim 1, it was evidence that was not in dispute in FFC#1.

64 The Full Court also rejected the arguments of the generic parties (repeated here by Apotex) about the reasoning in FFC#1. To understand this aspect of the matter, it is necessary to record the submissions which were rejected in FFC#3. The Full Court recorded the following:

47 Alphapharm accepts that the (+)-enantiomer is a pharmaceutical substance. The essence of its argument is that in the Decision, the subject matter of the claim was construed as the separated, isolated or pure enantiomer, which introduces a further criterion or limitation such that the claim is no longer a claim to the enantiomer per se. This is because the requirement that it be the substance per se means that there must be no further criterion (News Limited v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited (2003) 215 CLR 563 at [56]). Of course, it says, Cipramil cannot “contain” the separated molecule, the molecule free of the racemate, so it follows that what is contained in Cipramil is not the subject matter of the claim. Putting Alphapharm’s submissions another way, for the pharmaceutical substance per se the subject of the claim to comply with the requirements of s 70(2)(a) of the Act, it would be the isolated enantiomer and there are no goods included in the ARTG containing the pharmaceutical substance as required by s 70(3)(a) because the racemate contains the (+)-enantiomer and the (-)-enantiomer together.

48 Accordingly, Alphapharm submits, Lundbeck is not entitled to an extension of term of the Patent.

49 Alphapharm does not challenge the construction of the claim as adopted by the majority in the Decision. It says that the construction of the claim means that s 70(2)(a) is not satisfied. It points to the conclusion in the Decision that the racemate did not anticipate the separated enantiomer because it did not describe or disclose the separated or isolated or pure enantiomer and says that this means that it could not contain that enantiomer.

50 The issue, as distilled in this appeal, is whether the Decision demonstrates that the claim was held to include the criterion that the (+)-enantiomer was isolated or pure, either as an additional integer or by way of limitation. If so, Alphapharm contends, the claim is not to the molecule or to the compound. If it were, it says, the Lundbeck Full Court would have found, as did Emmett J who characterised the claim as a claim to the molecule, that it was anticipated by the Cipramil Patent which claimed the racemate.

65 The Full Court rejected these submissions including in the following paragraphs:

72 At [151], Bennett J said: ‘[t]hat is, [the claim] is to the separated or isolated or pure (+)-enantiomer’. It is apparent that, in context, her Honour was not considering levels of purity, as is made clear from the Decision at [157] to [160]. At [157] Bennett J expressly rejected the suggestion that the claim imported a limitation of purity. In that context her Honour drew a distinction between a limitation of purity and an ‘isolated, separated enantiomer, not in a mixture or in a racemate’.

73 It is quite clear that those words “isolated” and “pure” were not intended to add a further qualification or limitation to the claim. Rather, they imported the concept of “separate”, as is evident from [149] where her Honour said:

The invention is also said to be concerned with a method to resolve the racemate into the individual isomers. While the specification refers to the enantiomers, in the plural, it is in the context of their separate identity.

74 Her Honour then referred to the evidence that the skilled addressee would read the claim as referring to the isolated (+)-enantiomer, in contrast to the (+)-enantiomer as present in the racemate or in a mixture with the (–)-enantiomer. Clearly, in context, the word “isolated” referred to a resolution of the racemate into the separate enantiomers…

75 Turning to the alleged anticipation by the racemate disclosed and claimed in the Cipramil Patent, Bennett J said (at [194]) that while the skilled addressee knew that the racemate could be resolved into enantiomers, there was nothing to tell him or her to do so. Her Honour also noted that the Cipramil Patent was silent as to the means of obtaining the enantiomers. That is, Bennett J drew a distinction between the enantiomers unseparated or unresolved in the racemate and separated to yield the (+)-enantiomer of the claim. Justice Bennett took the view that the question that must be asked is whether Cipramil contained the same pharmaceutical substance per se disclosed and claimed in the Patent, namely the (+)-enantiomer.

76 Justice Bennett agreed with Lindgren J that the racemate was a good that contained the pharmaceutical substance (+)-citalopram. This reasoning constituted acceptance of (+)-citalopram as a pharmaceutical substance per se.

…

78 The construction of the claim, as understood by the skilled reader, does not import a limitation of purity. This is also made clear in the reasons of Middleton J. His Honour agreed with the reasons of Bennett J and dealt specifically with the submission that Lindgren J had impermissibly added integers that are not found in the claim. His Honour said at [252] that the claim ‘simply identifies the substance (+)-enantiomer’.

79 This construction did not involve reading into the claim a limitation of “independently existing” or “existing independently” of the racemate any more than it expands the context in which the (+)-enantiomer is to be found. Any reference to the (+)-enantiomer in the claim indicates that it is the separated or isolated enantiomer that is claimed. In other words, it is implicit in the way that the claim is worded, where the Patent is entitled ‘(+)-enantiomer of citalopram and processes for the preparation thereof’, that the claim is only to the isolated or separated (+)-enantiomer.

80 Accordingly, on the construction of the claim determined in the Decision, there is no further limitation imported into that claim. That was the clear conclusion of Bennett and Middleton JJ in the Decision. It is also consistent with their Honour’s reasoning and conclusion as to s 70 of the Act and as to whether citalopram, the racemate, contained the pharmaceutical substance per se, being the (+)-enantiomer or escitalopram disclosed and claimed in the Patent.

66 Turning to the submissions in FFC#3 the Full Court said this:

82 Alphapharm submits that, because of the evidence accepted by Lindgren J that a skilled person looking at the structure of citalopram would have recognised the presence of two enantiomers and would have been able to depict them, a claim to the enantiomer per se would necessarily have been invalid. Alphapharm then submits that in order to find that the (+)-enantiomer citalopram was novel, Lindgren J and Bennett and Middleton JJ construed the claim as being not to the enantiomer itself but rather to the enantiomer further defined or limited by the requirement that it be separated or isolated or pure. This ignores the wording of the claim, which does not import, in terms, the limitation that it be “isolated” (cf D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc (2014) 313 ALR 627 at [1]).

83 It also ignores the reasoning of each of Lindgren J, Bennett and Middleton JJ in concluding that the racemate did not anticipate the (+)-enantiomer. This was not because the claim should be read as being to the isolated enantiomer but, as explained in the Decision at [193]–[195], the disclosure of the racemate was not a disclosure to the skilled addressee of the (+)-enantiomer. As explained at [193], the skilled addressee would have understood that (±)-citalopram (the racemate) consisted of the (+)-enantiomer and the (-)-enantiomer and would have been able to identify the formulae for the enantiomers but would not have known in the absence of experimentation which was the (+)-enantiomer and which was the (-)-enantiomer. That is, there was no prior disclosure of the enantiomer independently existing. As Bennett J explained at [194], the skilled addressee knew that the racemate could be resolved into the enantiomers but there was nothing to tell him or her to do so. It could not even be said that there were clear and unmistakable directions to obtaining the enantiomers. Accordingly, it does not follow that a claim to the enantiomer per se would necessarily have been invalid.

…

88 Alphapharm also contends that Lundbeck had submitted in the Lundbeck Full Court that the requirement of ‘separated or isolated or pure’ was part of the text of the claim perceived by reading ‘the (+) symbol’. It relies upon the fact that this submission was accepted by Lindgren J at [119] and [123] and on the emphasis on the (+) symbol in Bennett J’s reasons. However, again, Alphapharm ignores Bennett J’s reasoning generally and specifically in rejecting a limitation as to purity (at [157]). Similarly, Middleton J stated that he was not reading into the claim a limitation of “independently existing” (at [252]). However, Alphapharm submits that this is because Lindgren J and Bennett and Middleton JJ considered that the integer or limitation did not need to be read into the claim as it was already part of the claim. Alphapharm also submits that separation, isolation and purification each refers to a process so that the claim is not to the enantiomer in itself, which it repeats would not have been novel, but only to the enantiomer when separated or isolated or purified.

…

91 In seeking to describe the difference between the racemate containing the two enantiomers and the claim to one of the enantiomers, Bennett and Middleton JJ used expressions such as “pure”, “isolated” and “separated”, the same language used by Lindgren J. Another way of describing the subject matter of the claim was ‘specific reference to the (+)-enantiomer, distinct from the (-)-enantiomer and not as present in the racemate mixture’ (the Decision at [131]). In seeking to differentiate between the racemate and the (+)-enantiomer, the word “itself” could just as easily have been used and would have carried the same meaning in context.

92 Justices Bennett and Middleton did not read into the claim an additional integer, nor did they add something to the words of the claim. Their reasoning was that the claim is to the (+)-enantiomer and nothing else. The term “pharmaceutical substance per se” simply means the pharmaceutical substance “in itself”. In Boehringer, Heerey J observed that per se meant ‘by or in itself’ ‘intrinsically’ or ‘essentially’ (at [7]). The Full Court approved that approach on appeal (at [37]).

93 Semantics aside, it is clear that the claim describes a pharmaceutical substance per se. The substance was, as explained by Lindgren J at [536], a new chemical entity. The racemate and the (+)-enantiomer had different physico-chemical interactions manifested in different pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (the Decision at [234]). The claim is to (+)-citalopram, irrespective of how it is produced. The isolated (+)-enantiomer plainly qualifies as a pharmaceutical substance per se and the primary Judge was correct in concluding that it satisfies s 70(2)(a) of the Act.

94 As pointed out by Lundbeck, Alphapharm’s submission that Bennett and Middleton JJ construed the claim to include an additional integer or a limitation, such that the claim was no longer to the (+)-enantiomer as a pharmaceutical substance per se, is wholly inconsistent with their Honours’ conclusion that the subject matter of the claim satisfied s 70(2)(a) of the Act, such that Lundbeck was entitled to an extension of term based upon Cipramil but not on Lexapro.

…

96 It is clear from the Decision that the expressions such as “separated or isolated or pure” did not import any concept of degree of purity. Quite clearly, Bennett J used the expression as a hendiadys, to explain that the (+)-enantiomer alone was claimed – without the (-)-enantiomer or the racemate. That is, it was the enantiomer itself. Put another way, it was the enantiomer per se.

67 In short, I agree with Lundbeck that Apotex and Sandoz, as parties to FFC#3, are subject to an issue estoppel with respect to the proper construction of claim 1 of the 144 patent. Apotex (and thus Sandoz) is not at liberty to argue, as they did, that claim 1 should be construed as Emmett J, in dissent proposed, in FFC#1. The construction of claim 1 in accordance with FFC#1 and FFC#3 was an essential or indispensable step leading to the dismissal of the appeal in FFC#3. The construction was not based on disputed expert evidence but uncontentious common ground between the parties as to the background science and the terms of the claim construed in the context of the specification as a whole.

68 Even if these conclusions were incorrect, Apotex’s argument that the evidence is different in the present case is unpersuasive. In short, Apotex relies on the evidence of the experts whom Lundbeck called, Professor Stephen Davies and Dr Alan Robertson, about infringement of the 144 patent to support its case. As Apotex argued, Professor Davies and Dr Robertson, in their evidence as to infringement, looked at the relevant information to identify the mere presence of the (+)-enantiomer. According to Apotex, this is “powerful evidence” that the construction of claim 1 in the Lindgren J judgment, FFC#1 and FFC##3 is wrong and that, rather, claim 1 claims the molecule, the (+)-enantiomer whether or not that molecule is in a mixture, racemic or otherwise, and irrespective of the degree of purity of the mixture.

69 I do not accept these submissions. Their evidence, taken as a whole, is inconsistent with these propositions. It was not put to Professor Davies or Dr Robertson during the course of these proceedings that the evidence they gave about infringement was inconsistent with the evidence they gave to the effect that they understood claim 1 to mean the (+)-enantiomer separate from the racemic mixture. The only difference between their evidence, and the approach in FFC#3 was that, in common with Lindgren J, they remained of the view that claim 1 would be read by the person skilled in the art as permitting chiral impurity provided that 95% purity was achieved. Bennett J (and thus Middleton J) rejected this in FFC#1 at [154]–[160]. In so doing, however, their Honours did not suggest that 100% chiral purity was required.

70 Apotex’s arguments to the contrary are not persuasive. As Lundbeck submitted, it was common ground that it is not possible to separate a racemic mixture into 100% pure (+)-enantiomer and (−)-enantiomer. This fact did not mean that Professor Davies and Dr Robertson accepted that claim 1 claimed the molecule, the (+)-enantiomer whether or not it exists in a mixture. Their evidence was to the opposite effect, that claim 1 refers to the separate enantiomer which will not be 100% pure because 100% separation cannot be achieved. When dealing with the issue of infringement, to the contrary of Apotex’s submission, their evidence is not to be understood as focusing on the mere presence of the (+)-enantiomer in the alleged infringing products. Their focus was the presence of the separated (+)-enantiomer which, as the evidence disclosed, was the active ingredient in the respondent’s allegedly infringing products to a very high level of purity. Indeed, the evidence was that it would be near impossible to achieve chiral impurity of the kind posited by Apotex (6% (−)-enantiomer) without simply adding back the requisite amount of the racemic mixture. As Dr Robertson said, to separate the (+)-enantiomer to the high level of purity possible (over 99%) then to add back in the racemate to achieve a lower level of purity would be perverse. Yet Apotex’s approach to construction depends on this kind of reading of the 144 patent, as well as FFC#1 and FFC#3 (despite, it must be said, FFC#3 containing a clear and cogent explanation of how FFC#1 cannot be understood as was proposed in that case and as Apotex proposes again in the present case).

71 Apotex’s contrary submissions relied on propositions which, in the circumstances had to be, but were not put to Professor Davies or Dr Robertson or otherwise focus on aspects of their evidence taken out of context. For this reason the fact that Dr Robertson did not give evidence before Lindgren J is immaterial. His evidence, understood fairly and in context, did not support Apotex’s molecule construction. The submission unfairly confuses Dr Robertson’s evidence identifying the (+)-enantiomer as the “particular molecule” with Apotex’s case that claim 1 means the (+)-enantiomer whether or not in a mixture. It is plain that Dr Robertson did not accept any such suggestion and that he understood claim 1 to mean the separated (+)-enantiomer (albeit that it could never be 100% pure) and not the (+)-enantiomer within a racemic mixture. Nothing Dr Robertson said in the joint report supports the contrary proposition put by Apotex.

72 Nor was there any material difference between the evidence given by Professor Davies before Lindgren J and in the present case. He too remained of the view that claim 1 had nothing to do with the (+)-enantiomer in the racemic mixture. He cannot be fairly criticised for taking into account the Full Court’s rejection of his view that claim 1 would be understood as involving a purity of at least 95% in FFC#1. It became apparent that Professor Davies’ view remained that a skilled addressee would understand claim 1 as involving the separated (+)-enantiomer to at least 95% purity.

73 It is unnecessary to address the evidence of Dr Richard Oppenheim on these matters in detail. Dr Oppenheim agreed that the (+)-enantiomer could not be separated from the racemate to achieve 100% pure (+)-enantiomer. He, wrongly, believed that FFC#1 required claim 1 to be understood as requiring 100% purity, relying on Bennett J’s reference to “separated or isolated or pure”. This belief is not supported by a reasonable reading of FFC#1 and, on no view, can survive the reasoning in FFC#3 which rejected this very proposition.

74 Leaving aside all these matters, Apotex did not confront the fact that the same construction issue has been the subject of extensive consideration in the Lindgren J judgment, FFC#1 and FFC #3. The argument that claim 1 means the molecule, the (+)-enantiomer whether or not it exists within the racemic mixture has been repeatedly rejected. The further argument (which Sandoz adopted) that, assuming this to be so, claim 1 means the (+)-enantiomer in a form which is 100% pure was also comprehensively rejected in FFC#3 and, in any event, was not open on a fair reading of FFC#1. Given this, why a different approach should be taken in the present matter is not apparent. The submission that the previous decisions relied on expert evidence which is different in the present case, as noted, is without real substance. Ultimately, Apotex (and thus Sandoz) gave no cogent reason to support its case on construction but merely ran the same arguments which have bene repeatedly rejected in the previous decisions.

75 Once this is recognised, Apotex’s other arguments, based on the specification as filed and as amended, provide no support to its case. The point Apotex attempted to make, that where the specification intends to refer to purity it does so expressly, involves a premise about claim 1 which has been repeatedly rejected, that it is concerned with purity in distinction from the separated (+)-enantiomer.

76 For these reasons Apotex’s molecule construction must be rejected. However, the rejection of this construction does not mean that claim 1 claims 100% pure separated (+)-enantiomer (as Sandoz would have it). It claims simply the separated (+)-enantiomer.

77 Apotex (and thus Sandoz) claimed that there is a fundamental contradiction between the fact that the term of the 144 patent was extended (which required the conclusion that Cipramil contained the substance, under s 70(3)(a) of the Patents Act) and the Full Court’s construction of claim 1 in FFC#1 and FFC#3 that “reads ‘(+)-citalopram’ as defining something that is ‘separated, isolated or pure’ and ‘not in a racemate or mixture’ with (–)-citalopram”. Leaving aside the fact that these submissions depended on giving a meaning to “separated, isolated or pure” in the Full Court decisions which they do not bear, the purpose of this submission is not apparent. To the extent it is intended to support the proposition that the Full Court’s construction of claim 1 is wrong, I do not see the contradiction. The fact that Cipramil contains the (+)-enantiomer within the meaning of s 70(3)(a) is a judicially determined fact, not now open to question. It is a fact, moreover, which accords with the evidence in the present case. While Professor Davies’ evidence about the nature of the racemic mixture included concepts that I can best describe as involving an appreciation of chemical ontology far beyond that which would be attributed to the skilled addressee, nothing he said (or could have said), undermines the unassailable conclusion that founded the grant of the extension of term of the 144 patent. The construction of claim 1 which has prevailed in all previous cases, and which I also accept, is not inconsistent with this conclusion. The asserted inconsistency is a construct of Apotex’s making, which pre-supposes both the correctness of its molecule construction and that the claimed (+)-enantiomer carries with it the concept of purity when it does not. All that has ever been said by previous cases, of current relevance, is that it is inherent within the very concept of the (+)-enantiomer that it is separated. This has never carried the freight which Apotex sought to attach to it.

3.3 Clarity

78 Apotex proposed that if claim 1 is construed as the Full Court in FFC#1 and FFC#3 would have it, and without any limitation as to purity, then the claim must fail for lack of clarity because the boundaries of claim 1 cannot be ascertained. It cannot be known what level of purity would infringe claim 1 because there is no apparent standard by which the claim can be interpreted. The 95% purity standard which Professor Davies proposed, and which Lindgren J accepted, was rejected in FFC#1 at [157]–[160] and is not advanced by Lundbeck in the present case. In any event, whether the proposed 95% purity is chemical, enantiomeric, optical or isomeric is unknown as Bennett J noted at [127] of FFC#1.

79 Sandoz, I note, did not adopt this aspect of Apotex’s argument or, at the least, did not do so for the purpose of asserting that claims 1 and 3 of the 144 patent are invalid. To ensure that my reasoning for rejecting Sandoz’s construction argument is properly exposed I deal with the clarity issues which Apotex raised below.

80 According to Apotex Bennett J’s observation in FFC#1 at [159] was prophetic. Bennett J said:

The construction contended for by Lundbeck also raises questions of clarity and uncertainty of infringement.

81 Her Honour was not referring to her preferred construction, however. She was referring to Lundbeck’s then proposed construction that involved a limitation on the level of purity of 95%. Bennett J (and Middleton J) rejected this limitation because the claim was to the separated enantiomer, the specification referred not to 95% enantiomeric purity (Lundbeck’s then case), but 99.6% and 99.9% optical purity having been achieved in Example 1. Her Honour was not saying that her own preferred construction involved a lack of clarity. Nor was she saying that the claim meant the separated (+)-enantiomer at 100% purity of any kind.

82 Apotex said that this was not a mere puzzle at the edge of a claim, as referred to in General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Co [1972] RPC 457 at 515. The skilled addressee, in the present case, cannot determine where the edge lies but, for the claim to be clear, the skilled addressee must know how much (−)-enantiomer would be too much and infringe the claim.

83 Contrary to these submissions, I am persuaded that this is precisely the kind of matter to which the observations in General Tire at 515–516 apply. It was there said that:

It is clear in our judgment that the question whether the patentee has sufficiently defined the scope of his claims is to be considered in relation to the facts of each case, that allowance is to be made for any difficulties to which the circumstances give rise, and that all that is required of the patentee is to give as clear a definition as the subject matter admits of. It is also clear in our judgment that, while the court is to have regard to all the relevant facts, the issue of definition is to be considered as a practical matter and little weight is to be given to puzzles set out at the edge of the claim which would not as a practical matter cause difficulty to a manufacturer wishing to satisfy himself that he is not infringing the patent. We accept also that definition of the scope of a claim is not necessarily insufficient because cases may arise in which it is difficult to decide whether there has been infringement or not provided the question can be formulated which the court has to answer in the issue of infringement.

84 As Lundbeck also noted, in Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 37; (1982) 41 ALR 471 at 476, the Full Court (Bowen CJ, Deane and Ellicott JJ) said this:

The essential features of the product or process for which it claims a monopoly are to be determined not as a matter of abstract uninformed construction but by a common sense assessment of what the words used convey in the context of then-existing published knowledge.

85 Approaching the present case as a practical matter, it must be accepted that it was common ground for those skilled in this area of stereochemical synthesis that 100% purity of any kind was not achievable. None of the experts suggested that they did not know that the (+)-enantiomer meant the separated (+)-enantiomer. Professor Davies and Dr Robertson explained that in order to obtain the (+)-enantiomer at some level of purity less than the very high levels disclosed in both the specification and, for that matter, the generic parties’ own batch analyses of their products, it would be necessary to add back in the racemic mixture. The commercial or practical purpose of such an exercise is not apparent. As noted, Dr Robertson described this as perverse, as it is.

86 Approached from a common sense perspective, in light of the knowledge which would be attributed to the skilled addressee of the 144 patent, the claim is clear. It is a claim to the separated (+)-enantiomer. As such, the racemic mixture, citalopram, falls outside the scope of the claim. As the skilled addressee would know the separated (+)-enantiomer cannot exist in a form that is 100% pure. There will always be trace, trivial or insignificant amounts of the (−)-enantiomer present. It does not matter what descriptor is used. The fact is that, to the person skilled in the art, the presence of insignificant amounts of the (−)-enantiomer is immaterial. Neither Professor Davies nor Dr Robertson (nor, for that matter, Dr Oppenheim once he put to one side what he incorrectly understood FFC#1 to mean) had any difficulty in identifying the separated (+)-enantiomer. They did not need to be instructed about any specific percentage tolerance to know when they were dealing with the (+)-enantiomer in contrast to the racemate.

87 Apotex’s attempt to blur the boundaries of the claim by referring to Professor Davies’ evidence about 95% purity is unsustainable. The fact that Professor Davies would read the claim as permitting up to 5% enantiomeric impurity (a proposition with which Dr Robertson agreed in oral evidence) does not render the claim unclear. This qualification was rightly rejected in FFC#1. Further, it was clear from the evidence of Professor Davies and Dr Robertson as a whole that they did not consider any specific percentage qualification was essential in order to understand the claim. They addressed the issue because they had been instructed to do so as a result of the dispute between the parties about what “separated, isolated or pure”, as used in FFC#1, meant. This question, of what the majority in FFC#1 meant by this reference, was nothing more than a distraction. As discussed, it is apparent from FFC#1 that the majority were not saying that the (+)-enantiomer had to be 100% pure. But nor were they saying that, as a result, the (+)-enantiomer as claimed was the same as the racemate. Nor were they saying that claim 1, as construed in FFC#1, was or would be unclear.

88 Once this is accepted, it is apparent that Apotex’s (and thus Sandoz’s) recourse to various percentages of (−)-enantiomer, such as 96%, 95% or 94%, involves the creation of a hypothetical construct divorced from the reality of the relevant science. The skilled addressee would not have any difficulty in knowing when the claim was infringed. If the act involves the (+)-enantiomer, the acts are within the monopoly claimed.

3.4 Novelty

89 Again, Sandoz did not claim that the 144 patent was invalid for lack of novelty, but explaining Apotex’s arguments and why I reject them may assist in understanding why I also reject Sandoz’s construction and non-infringement arguments.

90 Apotex’s novelty case may be shortly stated. Its principal case was that if its molecule construction is accepted, there is no question that claim 1 (and dependent claims) of the 144 patent will lack novelty because of the 445 or Citalopram patent. Its alternative case was that if the claimed invention in claim 1 of the 144 patent is merely the separated (+)-enantiomer then the 445 patent, nevertheless, deprives the claimed invention in claim 1 of the 144 patent of novelty.

91 Apotex submitted that the fact that the 445 patent does not refer to citalopram as having two enantiomers, the (+)-enantiomer and the (−)-enantiomer is irrelevant. The 445 patent disclosed the structural formula of citalopram which, to the skilled addressee, also disclosed that it was a racemic mixture consisting of equal amounts of the (+)-enantiomer and the (−)-enantiomer. The only matter not disclosed in the 445 patent, submitted Apotex, is the method of separating the two enantiomers, which is disclosed in and the subject of claim 6 of the 144 patent.

92 According to Apotex:

(1) “[w]ith respect to Lindgren J, and the majority in the 2009 Full Court, it is an error to ask whether the prior art contains a direction to the skilled addressee to resolve a racemate into enantiomers, or discloses a means of doing so…”; and

(2) “[t]he acceptance by Lindgren J (at [171]) and Bennett J (FFC #1 at [193]), that ‘the skilled but non-inventive addressee would have understood that [racemic] (±)-citalopram consisted of the (+)-enantiomer and the (–)-enantiomer…’ concludes the inquiry as to the novelty of claim 1, if Apotex’s … submissions on construction are accepted”.

93 Lundbeck’s answer to Apotex’s novelty challenge involves three aspects.

94 One, the issue of novelty was decided in the Lindgren J judgment and FFC#1, and there is no reason to depart from the conclusions there reached. The novelty challenge before Lindgren J was the same as that put by Apotex in these proceedings. It failed before Lindgren J and on appeal. Nothing has changed and the reasoning therein should be followed.

95 Two, in any event, Apotex is estopped from challenging the novelty of the 144 patent because it was a party to FFC#3 and the proper construction of claim 1 of the 144 patent, on which Apotex’s novelty challenge depends, was an essential aspect of the reasoning in FFC#3 on which the judgment depends.

96 Three, the evidence in the present case means that it is not open to conclude that claim 1 of the 144 patent is invalid because the claimed invention was not novel.

97 Lundbeck’s second proposition may be rejected immediately. Apotex’s novelty challenge does not depend on its molecule construction being accepted. Apotex also contends that, on the construction which has prevailed thus far and which I also accept, the 445 patent destroys the novelty of the invention claimed in claim 1 (and dependent claim 3) of the 144 patent. Accordingly, there is no relevant issue estoppel which arises from FFC#3.

98 Lundbeck’s first and third propositions, however, are persuasive and I accept them. I do not accept that Lindgren J and the majority in FFC#1 erred in rejecting the challenge to the novelty of the invention claimed in claim 1 of the 144 patent. Apotex’s arguments are the same as those Lindgren J rejected at [169]–[171] of the Lindgren J judgment. As Lindgren J said at [171]:

The Australian Citalopram Patent did not refer to “enantiomers”. It did not expressly or by implication otherwise disclose the individual enantiomers. It disclosed the racemate and enabled the obtaining of it. Whether this anticipated the present invention turns on my construction of the Patent – see Section C above. The skilled but non-inventive addressee reading the Australian Citalopram Patent would have understood that (±)-citalopram consisted of the (+)-enantiomer of citalopram and the (-)-enantiomer, each as to 50%, and would have been able to identify the formulae for the S and R enantiomers, but would not have known, in the absence of experimentation, which was (+) and which was (-). These facts would not, however, point specifically to the independent existence of the enantiomers which is, according to my construction of the Patent specification, of the essence of claim 1. If I had construed claim 1 as referring to (+)-citalopram when present in the unresolved racemate, the Australian Citalopram Patent would have been an anticipation. But because of my construction outlined at Section C above, a person taught by the Australian Citalopram Patent, although taught to desire to obtain the racemate, would not be taught to desire to obtain the specific (+)-enantiomer in its own right.

99 In FFC#1 Bennett J, with whom Middleton J agreed, said this:

193 The prior citalopram patent described the racemate. It did not describe the pure or isolated (+)-enantiomer. There is no anticipation unless the disclosure of the racemate was, to the skilled addressee, a disclosure of the (+)-enantiomer. As the primary judge pointed out at [171], the skilled but non-inventive addressee would have understood that (±)-citalopram consisted of the (+)-enantiomer and the (–)-enantiomer and would have been able to identify the formulae for the S and R enantiomers but would not have known in the absence of experimentation which was the (+)-enantiomer and which the (–)-enantiomer. As his Honour said, these facts would not point specifically to the independent existence of the enantiomers. They did not disclose an invention which, if performed, would necessarily infringe the Patent.

194 It is the case that the skilled addressee knew that the racemate could be resolved into the enantiomers but there was nothing to tell him or her to do so. Further, the prior citalopram patent was silent as to the means of obtaining the enantiomers and there were different methods available to try to do so. There were no clear and unmistakable directions to obtain the enantiomers. Some of the available methodology may have been successful, other methods may not.

195 The prior citalopram patent does not render claim 1 of the Patent not novel. It follows that it does not render claims 2, 3, 4 and 5 not novel.

100 To my mind, this reasoning involves no error. There being no material difference in the evidence in the present case about the knowledge to be attributed to the skilled addressee, there is no proper foundation for any different conclusion. Apotex appeared to accept that there is no direction of any kind to make the (+)-enantiomer. Its case is that, consistent with the alternative tests of clear direction or clear description in General Tire at 485–486, the (+)-enantiomer is clearly described in the 445 patent because the skilled addressee would know that the racemate includes equal parts of the (+)-enantiomer and (−)-enantiomer. But as Lindgren J and the majority in the Full Court reasoned, knowing that the racemate includes equal parts of the (+)-enantiomer and (−)-enantiomer but not knowing which was the (+)-enantiomer and which the (–)-enantiomer, how to obtain either one, or why anyone might wish to obtain either one is hardly a clear description of the (+)-enantiomer which could be said to have made the claimed invention “apparent to the skilled addressee”, as referred to be Bennett J in FFC# 1 citing Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Company [1990] FCA 37; (1990) 91 ALR 513 at 529. Nor did the 445 patent, as Apotex argued, make known the invention claimed in the 144 patent or enable that invention to be “read out of the prior publication”, as referred to in Hill v Evans (1862) 1A IPR 1 at 6. Nor, from the 445 patent, would the skilled addressee clearly infer the existence of the claimed invention in claim 1 of the 144 patent, being the separated (+)-enantiomer, as referred to by Bennett J in FFC#1 at [169] and [171], citing in support C Van der Lely NV v Bamfords Ltd [1963] RPC 61.

101 It is for these reasons that, having identified the relevant principles, Bennett J rejected the appeal on the lack of novelty ground. Yet Apotex’s argument involves accepting that while her Honour identified the very same principles upon which Apotex relied, her Honour nevertheless failed to apply those principles. The reality is that, properly applied, the principles simply do not support the asserted lack of novelty of the invention in claim 1 of the 144 patent.

102 Apart from this, I accept Lundbeck’s submission that the expert evidence in the present case does not support the asserted lack of novelty. Adopting Lundbeck’s submissions in this regard, Professor Davies said that the 445 patent did not disclose the invention claimed in claim 1 of the 144 patent because, so far as the 445 patent is concerned:

i. the structures that are depicted are racemic;

ii. there is no three dimensional information which discloses independently existing enantiomers;

iii. the (+)-enantiomer is a different material from the racemate and has different properties to the racemate; and

iv. there is nothing which tells him to resolve the racemate or how to resolve the racemate.

103 I also accept Professor Davies’ evidence that figure 1 in the 445 patent does not describe individual enantiomers because it provides no stereochemical descriptor. While the existence of the two enantiomers could be conceived of as a “sort of paper exercise”, they could not be identified and nothing could be known about them, not even whether they could be brought into existence separate from each other. Further the racemate and the (+)-enantiomer had to be understood to be “different materials”, with “different physical properties”, “different melting points”, “different solubility rates” and, perhaps, different therapeutic benefits.