FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2018] FCA 1733

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES & INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | WESTPAC BANKING CORPORATION ACN 007 457 141 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The joint application for consent orders be dismissed with no order as to costs.

2. The matter be stood over for a case management hearing on 27 November 2018 at 9.30am.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J

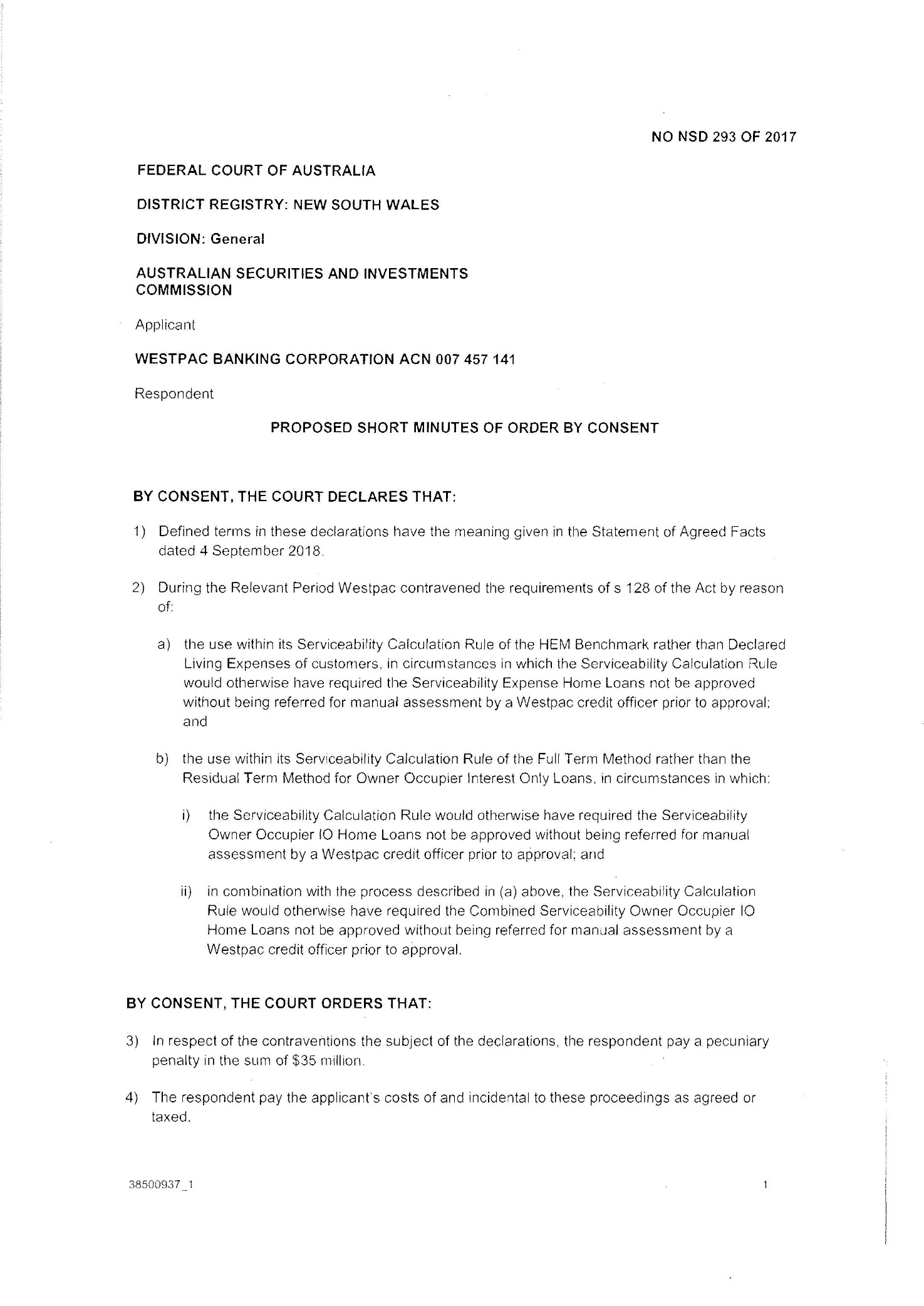

1 The Applicant and the Respondent jointly apply for the making of consent orders which would dispose of the proceeding in its entirety. They have joined in a statement of agreed facts. The proposed orders by consent are Annexure A to these reasons and the statement of agreed facts is Annexure B. The parties seek declarations of contravention and the imposition of a civil penalty of $35 million. The consideration of the proposed consent orders was not a straightforward exercise and led me to appoint amici curiae, Mr J T Gleeson SC and Ms F T Roughley, who provided great assistance in this matter.

2 For the reasons which follow, the joint application should be refused.

3 The proceeding is, in part, concerned with the manner in which the Respondent assessed the suitability of home loans for its customers in the period between 12 December 2011 and March 2015. Customers were required to provide information to the Respondent by completing an application form or providing the information through a broker. The information concerned several aspects of the customers’ financial affairs including their monthly living expenses.

4 The manner in which the Respondent made a decision about whether a home loan would be made was, to a large extent, automated by what the parties referred to as the Automated Decision System. This computerised system comprised just over 200 rules. For present purposes, only one of these rules is relevant, the Serviceability Calculation Rule. That rule created a decision-making process which turned on the calculation of what the rule referred to as the ‘Final Net Monthly Surplus/Shortfall’. This was defined to be equal to:

Final Net Monthly Surplus/Shortfall = Net Monthly Income – (Assessed Monthly Repayments + Outgoings) – (HEM Benchmark + “buffer”).

5 Without dwelling unnecessarily on the formal definition of those terms, it will be seen that the Final Net Monthly Surplus/Shortfall for each customer was not calculated using a customer’s declared living expenses but instead with the ‘HEM Benchmark’ together with a ‘buffer’. Nothing turns on the buffer and it may be disregarded.

6 The HEM Benchmark was the sum of the median expenditure on absolute basic goods and the 25th percentile expenditure on discretionary basic goods based on expenditure data gathered by the Australian Bureau of Statistics over 2009 and 2010. That data was updated quarterly to reflect the Consumer Price Index. The HEM Benchmark was also scaled for the geographic location of a customer’s intended place of residence, the number of dependants and marital status. It was not scaled for income. The HEM Benchmark therefore provided a figure for monthly living expenses which reflected the living expenses of persons in the customer’s locale with the same number of dependants and the same marital status.

7 Whether the use of such benchmarks as an input into the serviceability calculation is a good or bad idea is not a question this Court is called upon to address. What is required, however, is satisfaction that the use of the HEM Benchmark as disclosed by the statement of agreed facts is a contravention of s 128 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (‘Act’).

8 Section 128 prohibits a licensee (such as the Respondent) from, inter alia, entering into a credit contract with a consumer unless the licensee has within 90 days before the loan is advanced made an assessment that complies with s 129:

‘128 Obligation to assess unsuitability

A licensee must not:

(a) enter a credit contract with a consumer who will be the debtor under the contract; or

(aa) make an unconditional representation to a consumer that the licensee considers that the consumer is eligible to enter a credit contract with the licensee; or

(b) increase the credit limit of a credit contract with a consumer who is the debtor under the contract; or

(ba) make an unconditional representation to a consumer that the licensee considers that the credit limit of credit contract between the consumer and the licensee will be able to be increased;

on a day (the credit day) unless the licensee has, within 90 days (or other period prescribed by the regulations) before the credit day:

(c) made an assessment that:

(i) is in accordance with section 129; and

(ii) covers the period in which the credit day occurs; and

(d) made the inquiries and verification in accordance with section 130.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.’

9 What s 128 prohibits is the making of a credit contract where an assessment has not been carried out. Section 128 says nothing about the nature of an assessment other than it must be done in accordance with s 129. The prohibited acts in s 128 are therefore specified above the cincture to the provision, not below it. To labour the point, using the HEM Benchmark does not conceivably contravene s 128; it is making a credit contract without first making an assessment in accordance with s 129 which is the relevant act of contravention. As will be seen, this is important.

10 Contravention of s 128 carries a civil penalty of 2,000 penalty units but because the Respondent is a body corporate this is increased fivefold (s 167(3)(b)). The value of a penalty unit was $110 between 12 December 2011 and 27 December 2012 and $170 thereafter for the period of the alleged contraventions. The theoretical maximum penalty is therefore either $1.1 million or $1.7 million per contravention depending on whether the contravention occurred before or after 27 December 2012.

11 The parties’ agreed position on the present application is that the Respondent contravened s 128 by using the HEM Benchmark rather than the customers’ declared living expenses in calculating the Final Net Monthly Surplus/Shortfall in the Service Calculation Rule. But their agreement does not go much further than that and, in particular, does not extend to a consensus as to why it was a contravention of s 128 or which home loans entered into by the Respondent had been made in breach of s 128. As will be seen, admirable ingenuity has been applied by the parties’ advisers to the task of drafting the consent orders so as to gloss over the very real differences which exist between them. However, because the parties do not actually agree on what s 128 requires they are unable to agree on how many of the Respondent’s loans were made in contravention of it. This also makes it very difficult to judge the appropriateness of the proposed penalty of $35 million.

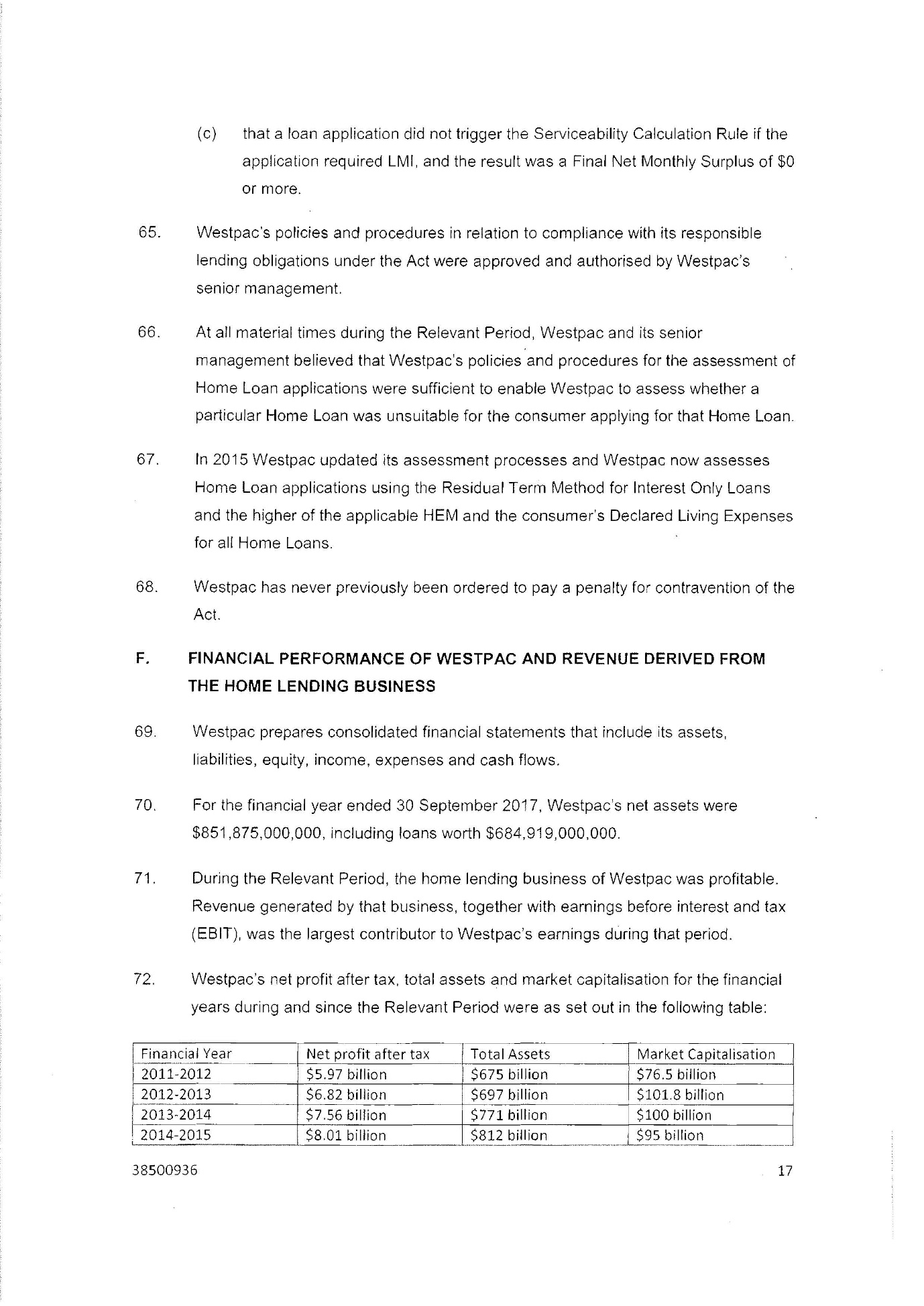

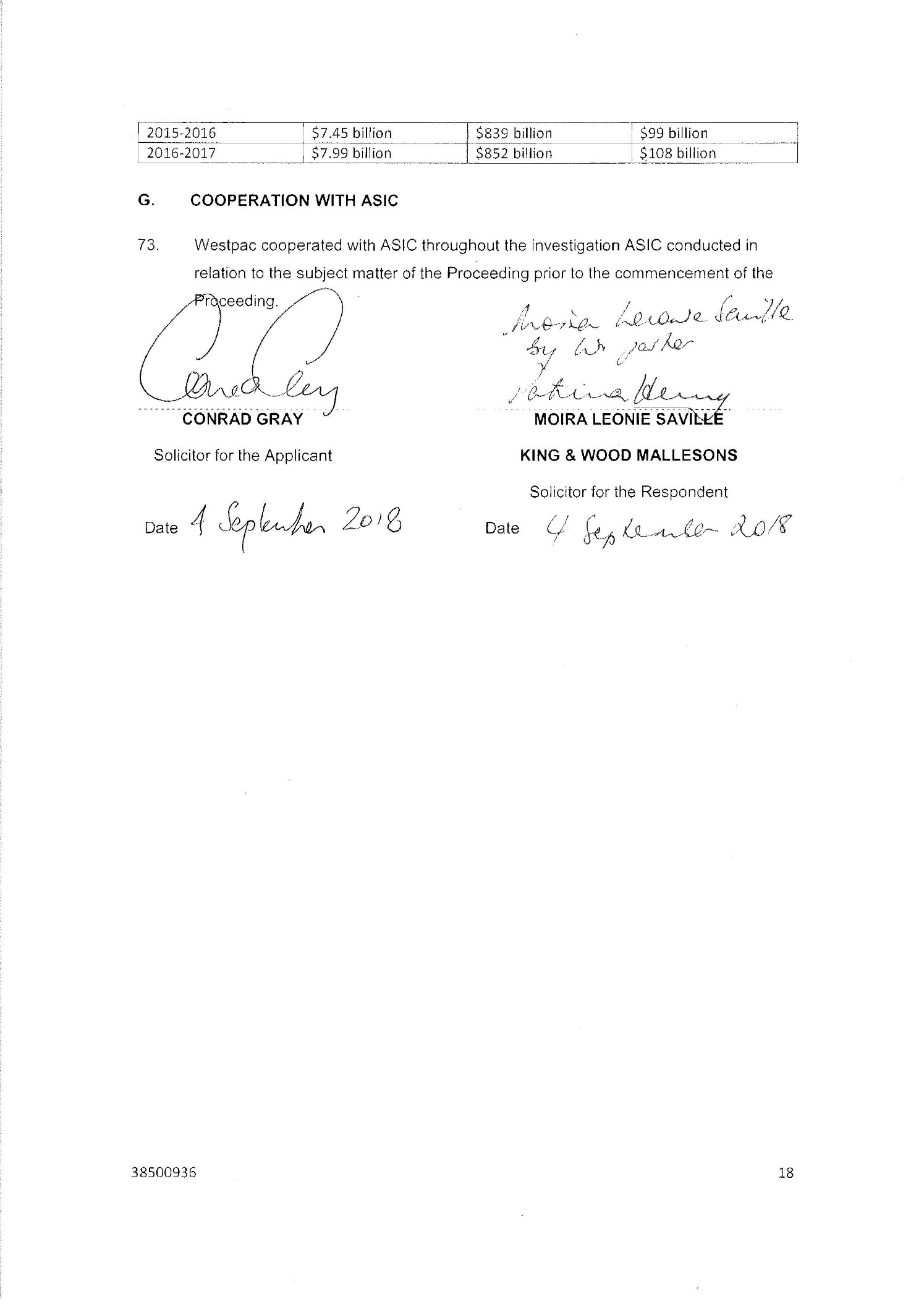

12 To grasp the scale of the problem, it is useful to start with the loans involved. Across the 3½ year period with which this case is concerned, the Respondent advanced 261,987 loans without manual assessment as a result of approvals generated by the Automated Decision Process. Each such approval was known as a conditional approval because the loan would then be referred to other business units for other (unrelated) checks.

13 Out of those 261,987 home loans there were some 211,937 where the customers had declared living expenses which were below the HEM Benchmark. That is a most interesting figure. It means that approximately 80% of the Respondent’s customers reported declared living expenses which were below the median for persons in their locale. This may suggest that Westpac’s customers reliably understate their monthly living expenses or, perhaps, that Westpac’s customers are more frugal than the general population, or even that the ABS statistics are wrong which seems unlikely and was certainly not suggested by either party.

14 There is presently no occasion, however, to confront this conundrum. What this interesting fact does mean in practice, however, is that, in relation to these 211,937 home loans the debate about the HEM Benchmark, regardless of the legalities of the situation, is something of a damp squib. This is because its utilisation inevitably led to a more conservative assessment of the customers’ creditworthiness since it calculated the Final Net Monthly Surplus on higher expenses than those that had actually been declared. This may have led some otherwise deserving loan applications to be refused or referred for manual assessment but it did not result in any which should have been refused being granted without manual assessment.

15 That leaves 50,050 (of the original 261,987) where the opposite was the case. In this approximately 20% of cases, customers had reported living expenses which were higher than the HEM Benchmark. The parties agree that, of these, the use of the customers’ declared expenses rather than the HEM Benchmark would have had no impact on the outcome of the assessment under the Serviceability Calculation Rule in some 45,009 cases. To be clear, that means that the use of the HEM Benchmark rather than declared living expenses in these cases had precisely no impact on what the course of the Respondent’s decision-making might otherwise would been.

16 However, that does leave 5,041 loans where the HEM Benchmark’s use in preference to declared living expenses would have made a difference. In these cases, the declared expenses were more than the HEM Benchmark and, if those expenses had been used instead of the HEM Benchmark, a flag would have been triggered and the customer’s application would not have been approved without referral to manual assessment. What would have happened after that manual assessment the parties have not told me. Nor have they told me whether any of these 5,041 loans were, or were not, suitable for the borrowers. This also undermines the ability of the Court to assess the reasonableness of the agreed penalty. Were the contraventions technical and harmless because the loans were suitable? Or, has significant harm been done to some or all of the 5,041 borrowers by the making of unsuitable loans? How can the Court be expected to assess the reasonableness of the proposed penalty if it be left in the dark about what the actual problem is?

17 What contraventions of s 128 do the parties agree are disclosed by these facts? This straightforward question unfortunately has no straightforward answer. Indeed, it was only after three days of hearing on this joint application for consent orders and the appointment by the Court of amici curiae to assist that the actual positions of the parties became tolerably clear.

18 The problems come into view when one examines with care the orders the parties ask the Court to make. In relation to the topic of the HEM Benchmark the parties ask the Court to make this declaration by consent (using the same terminology as is used in the statement of agreed facts):

‘2) During the Relevant Period Westpac contravened the requirements of s 128 of the Act by reason of:

a) the use within its Serviceability Calculation Rule of the HEM Benchmark rather than Declared Living Expenses of customers, in circumstances in which the Serviceability Calculation Rule would otherwise have required the Serviceability Expense Home Loans not be approved without being referred for manual assessment by a Westpac credit officer prior to approval;’

19 Immediately, one can see that there is something quite odd about this proposed declaration. Recalling that s 128 is a prohibition on entering into a credit contract with a consumer in certain circumstances, it will be seen that the declaration suffers from the small problem that it does not actually set out any conduct which could possibly contravene s 128. To contravene s 128 one needs to enter into a credit contract and there is absent from Declaration (2)(a) any reference to entry into such a contract.

20 This may sound rather technical but, as will be seen, for a number of reasons, it really is not. By s 166(3)(d) of the Act the Court is required, when it makes a declaration that a civil penalty provision such as s 128 has been contravened, to specify the conduct constituting the contravention and to do so in the declaration. The Court cannot make Declaration (2)(a) because it does not specify the conduct, i.e. the entry into the specified credit contracts, that constituted the contraventions of s 128 .

21 The fact that the proposed declaration does not identify the credit contracts which were entered into in apparent breach of s 128 is no accident. As became apparent during the hearing, it does not do so because the Applicant and the Respondent do not agree on how many credit contracts were entered into in breach of s 128. This is because they differ as to the proper construction of ss 129-130. These provide:

‘129 Assessment of unsuitability of the credit contract

For the purposes of paragraph 128(c), the licensee must make an assessment that:

(a) specifies the period the assessment covers; and

(b) assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in that period.

Note: The licensee is not required to make the assessment under this section if the contract is not entered or the credit limit is not increased.

130 Reasonable inquiries etc. about the consumer

Requirement to make inquiries and take steps to verify

(1) For the purposes of paragraph 128(d), the licensee must, before making the assessment:

(a) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; and

(b) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and

(c) take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation; and

(d) make any inquiries prescribed by the regulations about any matter prescribed by the regulations; and

(e) take any steps prescribed by the regulations to verify any matter prescribed by the regulations.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

(1A) If:

(a) the credit contract is a small amount credit contract; and

(b) the consumer holds (whether alone or jointly with another person) an account with an ADI into which income payable to the consumer is credited;

the licensee must, in verifying the consumer’s financial situation for the purposes of paragraph 128(d), obtain and consider account statements that cover at least the immediately preceding period of 90 days.

(1B) Subsection (1A) does not limit paragraph (1)(c) of this section.

(2) The regulations may prescribe particular inquiries or steps that must be made or taken, or do not need to be made or taken, for the purposes of paragraph (1)(a), (b) or (c).’

22 The Applicant’s construction says that a consumer’s financial information obtained by the licensee under s 130(1)(b) must be taken into account when the licensee carries out the assessment in s 129. If that view be correct, then the total number of contraventions will be 261,987, that is to say, every home loan entered into by the Respondent in the relevant period where it did not use the customer’s declared living expenses.

23 The Respondent’s interpretation is narrower. It says that in doing an assessment under s 129 regard must be had to a consumer’s financial information obtained under s 130 but only ‘to the extent it rationally informs the opinion of the licensee as to whether the proposed contract is unsuitable’.

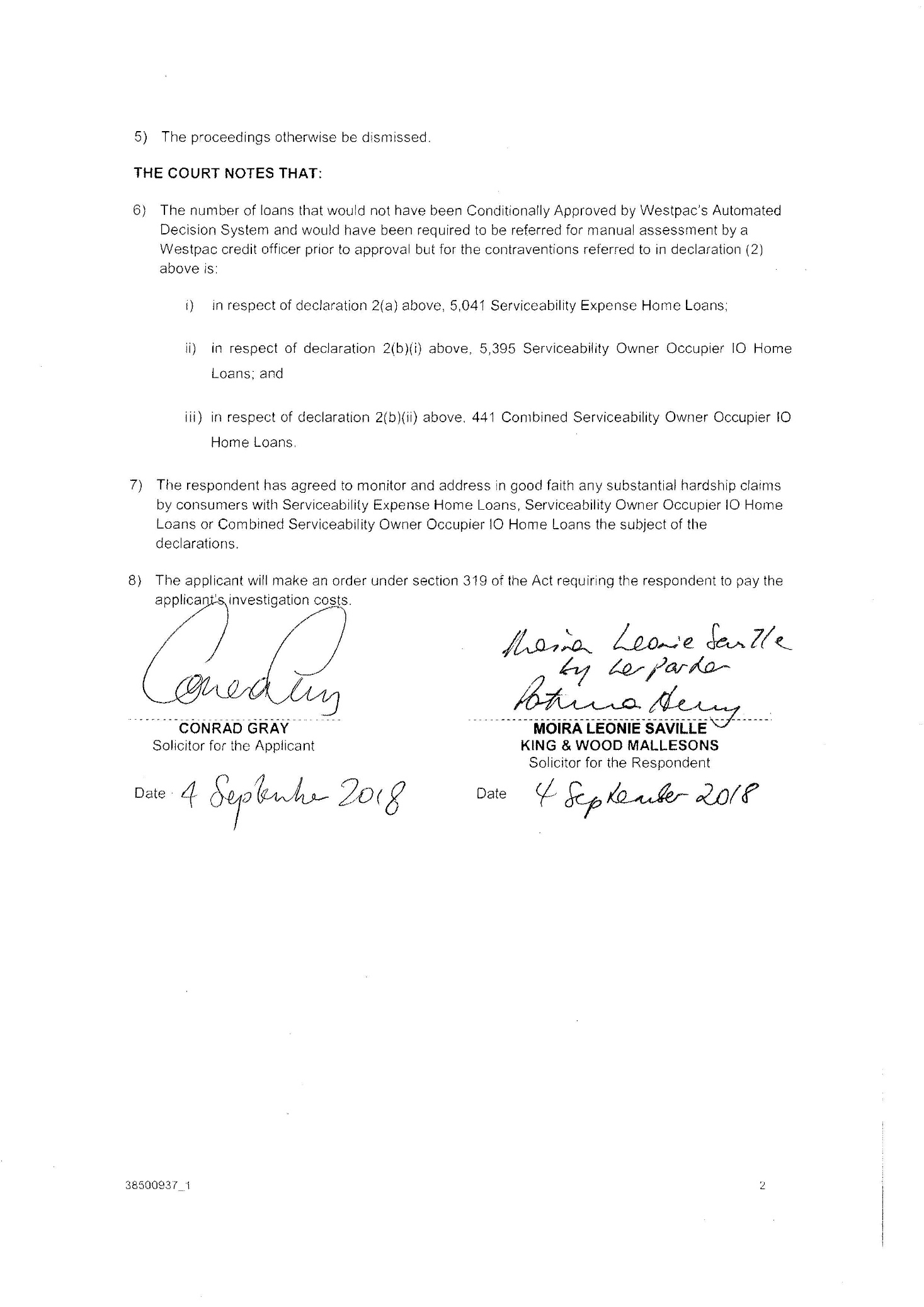

24 These two views of ss 128-130 are chalk and cheese. Nevertheless, the Applicant and the Respondent can agree that the 5,041 loans to which reference has already been made were extended in contravention of s 128. The parties do not actually say as much in the proposed orders but they do desire the Court to note an agreement they have. The proposed agreement is as follows:

‘THE COURT NOTES THAT:

6) The number of loans that would not have been Conditionally Approved by Westpac’s Automated Decision System and would have been required to be referred for manual assessment by a Westpac credit officer prior to approval but for the contraventions referred to in declaration (2) above is:

i) in respect of declaration 2(a) above, 5,041 Serviceability Expense Home Loans;’

25 Even with this curious agreement and its contrived avoidance of the word ‘contravention’, there are still difficulties identifying why it is said that the Respondent contravened s 128 by making 5,041 credit contracts without doing an assessment of the customers’ financial position. This is because the agreement refers only to loans that would not have been conditionally approved (rather than, as s 128 requires, credit contracts which were made).

26 If the declaration specified, as s 166 of the Act requires that it should, the conduct constituting the contravention then the parties would be forced to say which of the 261,987 loans involved credit contracts made in breach of s 128 and what was it about each of those credit contracts which meant that there had been no assessment under s 129.

27 In that hypothetical scenario, where the parties’ proposed declaration complied with s 166 and specified the contravention, the Respondent’s construction of ss 129-130 would lead to 5,041 contraventions specified in the declaration. As Mr Kirk SC for the Respondent explained it, this is because the Respondent accepted that it was not rational in those cases not to use the customers’ declared expenses: they were higher than the HEM Benchmark and they would have made a difference to the outcome because the customers’ application would have been referred for manual assessment. Without knowing what the outcome of the manual assessment would have been I am not sure one can necessarily even say that on the Respondent’s alternate construction. However, that quibble may be put to one side along with the fact that there is no agreed fact before me that any of these 5,041 loans was unsuitable.

28 On the other hand, on the Applicant’s construction, there would be 261,987 contraventions specified in the declaration because each time a credit contract was made without using a customer’s declared expenses, a contravention of s 128 occurred.

29 I do not propose to make the declaration sought. I simply do not accept that the conduct specified in the declaration is conduct which could possibly be a contravention of s 128. I will not declare conduct which is not unlawful to be unlawful. The contraventions of s 128, that is the entry into credit contracts, must be specified. The declaration tells one next to nothing. It could describe a bank which made 2 loans, 50,000 loans or, significantly, no loans at all. The parties’ side agreement about the 5,041 loans as set out in the proposed notation does not form part of the declaration and does not solve that problem. Correspondingly, the declaration does not provide any information about when the use of the HEM Benchmark instead of the customers’ declared living expenses is permitted and when it is not. As the parties plainly intended, this is precisely the question the declaration does not answer.

30 For completeness, it should also be noted that on each occasion this Court has been asked to impose penalties for entering into credit contracts without complying with regulatory requirements the Court has identified the contraventions in the declarations: see, for example, Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Thorn Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 704; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2018] FCA 155; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Ostrava Equities Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1064; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] FCA 926.

31 It will be apparent given all of this uncertainty that, even if the proposed declarations were made by consent, it is also quite impossible to address the appropriateness of the suggested penalty. The parties have placed no material before the Court on the joint application revealing why the Respondent decided to use the HEM Benchmark in preference to customers’ declared living expenses. Not knowing why the Respondent decided to use the HEM Benchmark in preference to customers’ declared living expenses makes it very difficult to assess how serious its conduct is and hence how appropriate a civil penalty of $35 million might be. For example, did the Respondent use the HEM Benchmark because it thought it more reliable than customers’ self-reported living expenses? Or did the Respondent use it because it did not wish to suffer the administrative burden of analysing an individual customer’s living expenses? Or was it because it wished to make as many unsuitable loans as it could? There are many other possibilities. Each discloses conduct of a differing level of seriousness. Yet the Court is asked to say that the proposed penalty is appropriate even though it knows nothing of the Respondent’s motives beyond a bland agreed fact that it acted in good faith. In the information vacuum in which the parties have left the Court, this is not possible. I invited the parties to address this issue but the invitation was declined.

32 It is unworkable to assess the reasonableness of the penalty if it is not known what is to be penalised. This problem can only be solved by the parties agreeing which credit contracts were made in contravention of s 128 and, as s 166 requires, putting the circumstances constituting that breach in the declaration. It will be obvious that to do that one party would need to accede to the other party’s view of how ss 128-130 operate. To date this has not happened. Furthermore, the Court should not be expected to approve a (record) penalty without being told why the HEM Benchmark was used by the Respondent in preference to declared living expenses. That missing fact is, with respect, the elephant in the court room.

33 I decline therefore to make the consent orders proposed in relation to the HEM Benchmark issue. In doing so, I accept the need for the Court to encourage settlements in this area but the desirability of doing so does not permit the Court to become a rubber stamp, especially where there is patent disagreement as to what conduct constitutes a contravention.

34 Separate orders were provided in relation to the Respondent’s processing of home loan applications with an interest-only period. As with the orders discussed above, the proposed declaration does not specify any conduct that constitutes a contravention of s 128. Those orders are refused for the same reasons.

I certify that the preceding thirty-four (34) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Annexure A

Annexure B