FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Oakmoore Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1170

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Palram Australia, being a company which acquires and supplies profiled polycarbonate roof sheeting (“polycarb”) to retail stores, large commercial users and on-sellers (together, “commercial purchasers”) in Australia:

1.1 between around December 2010 and February 2012, acquired polycarb from the first respondent (“EGR”), on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia, which conduct had the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the market in which polycarb was supplied to commercial purchasers in Australia, and thereby contravened s 47(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (“CCA”) by engaging in the practice of exclusive dealing, as defined in s 47(4) of the CCA; and

1.2 between around February 2012 and February 2013, acquired polycarb from EGR, on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia, which conduct had the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the market in which polycarb was supplied to commercial purchasers in Australia, and thereby contravened 47(1) of the CCA by engaging in the practice of exclusive dealing, as defined in s 47(4) of the CCA.

2. Ms Horesh, being a director of Palram Australia having knowledge of all of the matters set out in declarations 1(a) and 1(b) above, and having been knowingly concerned in that conduct of Palram Australia, was involved in Palram Australia’s contraventions of the CCA described in 1(a) and 1(b) above, within the meaning of s 75B(1)(c) of the CCA.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary Penalty

3. Palram Australia pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $3,500,000 in respect of the contraventions referred to in declarations 1.1 and 2 above, within 90 days of the date of this order.

Competition Law Compliance Training Program

4. Within three months of the date of this order, Palram Australia will establish a compliance program, for employees and other persons involved in its business, including directors, to ensure their awareness of the responsibilities and obligations under Part IV of the CCA, that complies with each of the requirements specified in annexure A to these orders.

Disqualification order

5. Pursuant to s 86E(1) of the CCA, that Ms Horesh be disqualified from managing corporations for a period of three years from the date of these orders.

Costs

6. Palram Australia make a contribution to the ACCC’s costs in the amount of $250,000, to be paid within 30 days of the date of these orders.

Proceedings against Palram Industries

7. The proceedings against the fourth respondent (“Palram Industries”) be dismissed, with Palram Industries bearing its own costs of and incidental to the proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

GLEESON J:

Introduction

1 This is a second application for consent orders in this civil penalty proceeding, in which the applicant (“ACCC”) seeks relief in connection with alleged anticompetitive conduct and exclusive dealing between certain suppliers of profiled polycarbonate roof sheeting (“polycarb”) to retail stores, large commercial users and on-sellers in Australia in the period from approximately December 2008 to June 2013 in contravention of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (previously the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)) (“CCA”).

2 The application concerns the second, fourth and sixth respondents.

3 The judgment on the first application was in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Oakmoore Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1169 (“earlier judgment”). That judgment concerns the third respondent (“Ampelite”) and the seventh respondent (“Mr Verhagen”). The first respondent (“EGR”) and the fifth respondent (“Mr Horwill”), EGR’s managing director, are defending the proceeding.

4 The second respondent (“Palram Australia”) carries on business in in Australia as an acquirer and supplier of polycarb (among other products).

5 The fourth respondent (“Palram Industries”) is a publicly listed company incorporated in Israel and the parent company of Palram Australia. The ACCC does not press the allegations made against Palram Industries in the proceeding.

6 The sixth respondent (“Ms Horesh”) is, and was at all material times, a director of Palram Australia. In these reasons, I will refer to Palram Australia and Ms Horesh as the “Palram parties”.

7 Palram Australia has admitted two contraventions of s 47 of the CCA. Ms Horesh has admitted that she was knowingly concerned in and involved in Palram Australia’s contraventions of the CCA, within the meaning of s 75B(1)(c) of the CCA.

8 The ACCC, Palram Australia and Ms Horesh (“parties”) have reached agreement as to the terms of relief to be sought from the Court to resolve the proceeding. While recognising that the question of relief remains at the Court’s discretion, those parties asked the Court to make declarations of the admitted contraventions; an order for the payment of pecuniary penalties totalling $3.5 million by Palram Australia; an order that Ms Horesh be disqualified from managing corporations for a period of three years; an order that Palram Australia make a contribution to the ACCC’s costs in the amount of $250,000; and an order that Palram Australia establish a competition law compliance program.

9 In support of their application for these orders, the parties relied on joint submissions and a statement of agreed facts, each dated 2 March 2018. For reasons set out below, I rejected the Palram parties’ application for non-publication orders in relation to portions of the joint submissions and the statement of agreement facts.

10 The factual basis for my decision on this application is contained in the statement of agreed facts which is annexed to these reasons. The agreed facts are different in important respects from the facts upon which the earlier judgment is based. As appears from that judgment, Ampelite and Mr Verhagen admitted to different contraventions of the CCA and made a separate application for orders by consent, including orders for the payment of pecuniary penalties.

11 As I noted in my earlier judgment, the public interest in parties resolving civil penalty matters with regulators such as the ACCC was reaffirmed by the High Court in Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate; Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (“CFMEU case”) at [46] as follows (full citations added):

[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills [[1981] FCA 156; (1981) 37 ALR 256] and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods [[1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285], such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

12 For the reasons set out below, I am satisfied that the Court has power to make the proposed orders and that it is appropriate to make the orders sought. My reasons substantially adopt the joint submissions made by the parties.

Relevant provisions of the CCA: Exclusive dealing

13 At the relevant times, s 47 of the CCA provided relevantly:

(1) Subject to this section, a corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in the practice of exclusive dealing.

...

(4) A corporation also engages in the practice of exclusive dealing if the corporation:

(a) acquires, or offers to acquire, goods or services; or

(b) acquires, or offers to acquire, goods or services at a particular price;

on the condition that the person from whom the corporation acquires or offers to acquire the goods or services or, if that person is a body corporate, a body corporate related to that body corporate will not supply goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description, to any person, or will not, or will not except to a limited extent, supply goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description:

(c) to particular persons or classes of persons or to persons other than particular persons or classes of persons; ….

14 Palram Australia has admitted that:

(1) between around December 2010 and February 2012, it acquired polycarb from EGR, on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers (being retail stores, large commercial users and on-sellers) that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia, which conduct had the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the market in which polycarb was supplied to commercial purchasers in Australia, and thereby contravened s 47(1) of the CCA by engaging in the practice of exclusive dealing, as defined in s 47(4) (“first contravention”); and

(2) between around February 2012 and February 2013, it acquired polycarb from EGR, on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia, which conduct had the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the market in which polycarb was supplied to commercial purchasers in Australia, and thereby contravened s 47(1) by engaging in the practice of exclusive dealing, as defined in s 47(4) (“second contravention”).

Application for non-publication orders

15 At the hearing, the Palram parties sought orders protecting certain information contained in the joint submissions and the agreed facts pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (“Federal Court Act”). The orders were sought on the basis that the information was commercially sensitive such that, if competitors were to have access to the information, Palram would be placed at a competitive disadvantage.

16 As explained below, relevant factors in considering the appropriateness of the proposed pecuniary penalty include:

(1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(2) the size and financial position of Palram Australia; and

(3) the degree of Palram Australia’s market power, as evidenced by its market share.

17 Information of the kind that the Palram parties seek to protect is routinely published in the Court’s reasons for making orders following a finding that a party has contravened Pt IV of the CCA. As the ACCC’s submissions observed, this is unsurprising because it is information that goes to fundamental facts in the setting of an appropriate penalty. In particular, the ACCC was unable to identify any case in which a Court has made a non-publication order with respect to the amount of a company’s revenue when imposing a pecuniary penalty.

18 Recently, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Acquire Learning & Careers Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 602 (“Acquire Learning”), Murphy J made orders including for the payment of pecuniary penalties by consent for contraventions of the Act. In support of the application for the orders, the parties had tendered confidential information as to the revenue, profitability and asset position of the respondent. At the time of tender, Murphy J made orders pursuant to ss 37AF and 37AG of the Federal Court Act for the financial information to be treated as confidential except to the extent that his Honour considered it necessary or appropriate to refer to the information in his Honour’s reasons for judgment. At [78] and [79], Murphy J set out information concerning the respondent’s revenue and profitability, his Honour presumably considering this to fall within the carve-out to the confidentiality orders.

Legal framework concerning non-publication orders

19 Section 37AF provides relevantly:

(1) The Court may, by making a suppression order or non-publication order on grounds permitted by this Part, prohibit or restrict the publication or other disclosure of:

...

(b) information that relates to a proceeding before the Court and is:

(i) information that comprises evidence or information about evidence; or

…

(iv) information lodged with or filed in the Court.

(2) The Court may make such orders as it thinks appropriate to give effect to an order under subsection (1).

20 Section 37AE provides:

In deciding whether to make a suppression order or non-publication order, the Court must take into account that a primary objective of the administration of justice is to safeguard the public interest in justice.

21 By s 37AG(1)(a), the Court may make a suppression order or non-publication order on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice. By s 37AG(2), a suppression order or non-publication order must specify the ground or grounds on which the order is made. By s 37AJ(1), a suppression order or non-publication order operates for the period decided by the Court and specified in the order. By s 37AJ(2), in deciding the period for which an order is to operate, the Court is to ensure that the order operates for no longer than is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose for which it is made.

22 The onus on the party seeking to persuade the Court to make an order under s 37AF is a heavy one: Oreb v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2016] FCA 321 at [80]. Mere embarrassment, inconvenience, annoyance or unreasonable or groundless fears will not suffice: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cascade Coal (No 1) [2015] FCA 607 at [30]. In Solahart Industries Pty Ltd v Solar Shop Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 700 at [116], Perram J said (in considering the application of s 50, the predecessor to s 37AF):

[T]his risk must be real and the evidence compelling because the order reversing the ordinary principle of open justice is not to be made lightly. The requirement of s 50 is not inconvenience or suspicion or concern; it is necessity and only proof positive of necessity will enliven the power.

23 Commercial confidentiality alone is not enough to justify a non-publication order. There must also be a real risk of commercial harm flowing from disclosure: Betfair Pty Ltd v Racing New South Wales (No 5) [2009] FCA 1011 at [9]. In Motorola Solutions, Inc v Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 17 at [8] and [9], Perram J said:

[8] It might be thought that the mere protection of commercial-in-confidence information … fits less comfortably within the statutory words ‘necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice’. But this Court has held in a number of cases that commercial sensitivity can be an appropriate basis for making a suppression or non-publication order: see Australian Broadcasting Commission v Parish (1980) 29 ALR 228 at 235 per Bowen CJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1082 at [23] per Greenwood J; Cyclopet Pty Ltd v Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation [2012] FCA 1326 at [7] per Jacobson J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 1430 (‘Air New Zealand (No 3)’) at [35]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Origin Energy Electricity Ltd [2015] FCA 278 (‘Origin Energy’) at [148] per Katzmann J; ASE16 v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2016] FCA 321 at [93] per Markovic J.

[9] There are cogent reasons for this which have variously been described in those cases, but they are generally associated with preserving the integrity of the litigious process, likely to be jeopardised if commercial competitors could benefit from court ordered production of trade secrets by parties to a suit. That said, it is important to recall that the order must be necessary to protect the administration of justice. It can readily be imagined that a carte blanche approach to applications for s 37AF orders for which commercial confidentiality is claimed as a basis, would jeopardise the interest the public has in being able to access court documents under the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) or to engage meaningfully with reasons published by the Court… [T]he safeguarding of that interest as a primary objective of the administration of justice is a mandatory consideration for the Court…

24 The Palram parties pressed for orders under s 37AF even if the information was required for the judgment (except in relation to Ms Horesh’s kibbutz allowance as it was not likely to be something to which the Court would need to refer).

Confidential information

25 The information in respect of which the orders were sought was:

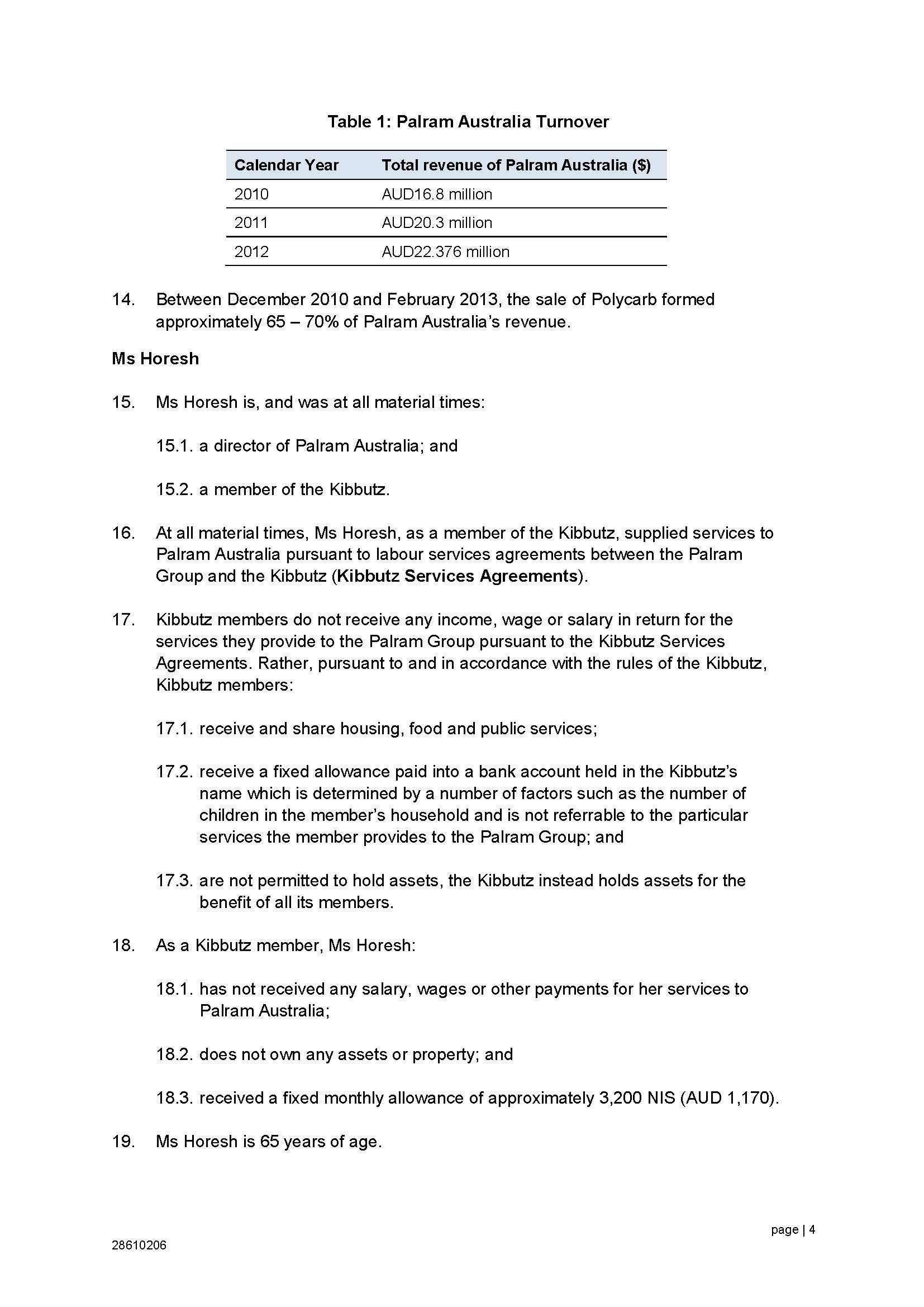

(1) Palram Australia’s annual revenue for each of 2010, 2011 and 2012 stated in Table 1 of the statement of agreed facts and paras 29.2, 29.3.2, 30.2, 30.3.2 and 66 of the joint submissions (“revenue information”);

(2) the proportion of Palram Australia’s revenue during the period December 2010 to February 2013 derived from the sale of polycarb stated in para 14 of the statement of agreed facts and para 66 of the joint submissions (“revenue percentage information”);

(3) the amount of the fixed monthly allowance received by Ms Horesh as member of Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan (“Kibbutz”) stated in para 18.3 of the statement of agreed facts (“Kibbutz allowance information”);

(4) Palram Australia’s estimate of the proportion of total sales of polycarb in the distribution market (as defined at para 35 of the statement of agreed facts) during the period December 2010 to February 2013 comprised of its sales stated in para 36 of the statement of agreed facts and para 68 of the joint submissions (“sales percentage information”);

(5) the approximate value of the polycarb purchased by Palram Australia from EGR:

(a) during the period between December 2010 and January 2012, stated in para 68 of the statement of agreed facts; and

(b) during the period between February 2012 and February 2013, stated in para 82 of the statement of agreed facts (“value information”).

Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence

26 In support of the application, the Palram parties relied upon an affidavit of Ms Ravit Birnbaum-David, chief legal officer of Palram Industries and in-house legal counsel for Palram Australia, affirmed 4 March 2018.

27 At the Court’s request, the ACCC made submissions concerning the application. The ACCC contended that the proposed orders should be refused because the evidence did not satisfy the requisite standard for the making of an order pursuant to s 37AF. The ACCC objected to the admissibility of portions of Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence as inadmissible opinion evidence, questioning her relevant knowledge and experience. I allowed the evidence but permitted cross-examination.

28 In her affidavit, Ms Birnbaum-David gave reasons why, in her opinion, disclosure of the information over which protection was sought (apart from the Kibbutz allowance information) would be likely to provide a commercial and competitive advantage to industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers to the commercial and competitive disadvantage of Palram Australia.

Revenue information and revenue percentage information

29 Concerning the revenue information, Ms Birnbaum-David stated relevantly:

12. The Revenue Information relates to the period 2010 to 2012. In my experience, experienced industry participants are aware of the rates of growth experienced in the industry over time and of significant developments in the industry, such as particular companies winning or losing significant customer contracts. With this awareness, in my view, experienced industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will likely be able to determine Palram Australia’s approximate current annual revenue by reference to the Revenue Information.

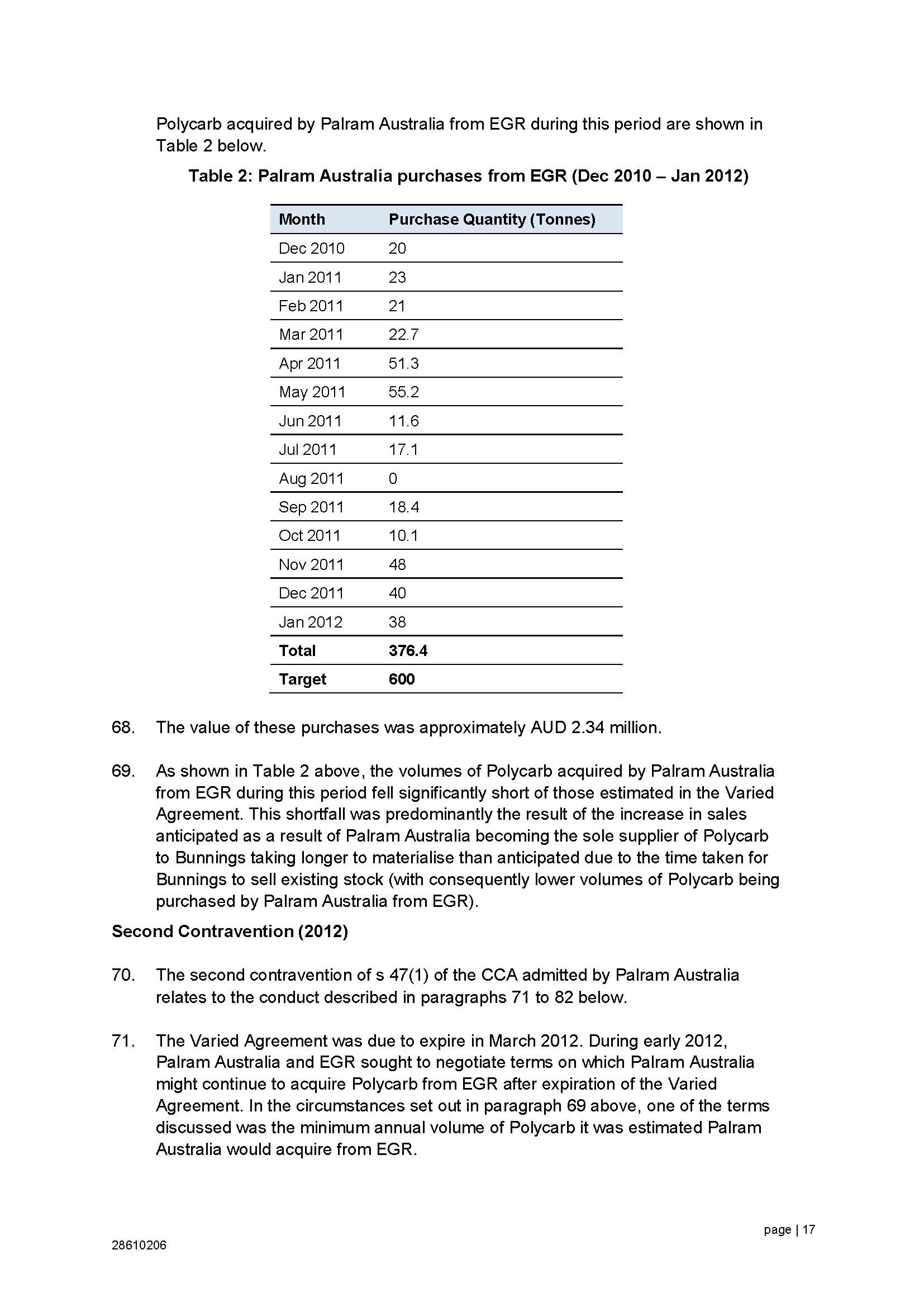

13. Disclosure of the Revenue Information to industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will thereby:

(a) make available to these participants detailed (otherwise confidential) commercial information about Palram Australia’s size, financial performance and operations;

(b) likely enable these participants to calculate Palram Australia’s approximate profitability;

(c) (together with the Revenue Percentage Information) enable these participants to calculate Palram Australia’s market share, this information being confidential and commercially sensitive for the reasons outlined in paragraphs 18 to 20 below, given that the value of total sales in the Distribution Market (as defined in paragraph 35 of the Statement of Agreed Facts) during the same period is stated in paragraph 36 of the Statement of Agreed Facts and in paragraph 68 of the Joint Submissions;

(d) likely enable these participants to estimate the value of Palram Australia’s key customer contracts, including by comparing changes in Palram Australia’s revenue during the period 2010 to 2012 against facts set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts concerning Palram Australia winning a tender process to supply a major (ongoing) retailer customer in late 2010;

(e) possibly enable these participants to estimate the prices charged by Palram Australia to the key customers referred to in paragraph 13(d) above, for example, if the industry participants are able to estimate the volume of sales made to those customers; and

(f) thereby provide a commercial and competitive advantage to these participants (to Palram Australia’s commercial and competitive disadvantage), by making available to them otherwise confidential, commercial information which they will be able to use in the course of their dealings with Palram Australia and each other.

30 The revenue percentage information is sales of polycarb as an approximate percentage range of Palram Australia’s revenue between December 2010 and February 2013.

31 In her affidavit, Ms Birnbaum-David stated:

15. The Revenue Percentage Information relates to the period 2010 to 2013. In my experience, experienced industry participants are aware of significant developments in the industry such as material changes in the types of products supplied by particular distributors. With this awareness, in my view, experienced industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will likely be able to determine the approximate proportion of Palram Australia’s revenue currently derived from the sale of Polycarb by reference to the Revenue Percentage Information.

16. Disclosure of the Revenue Percentage Information to industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will thereby:

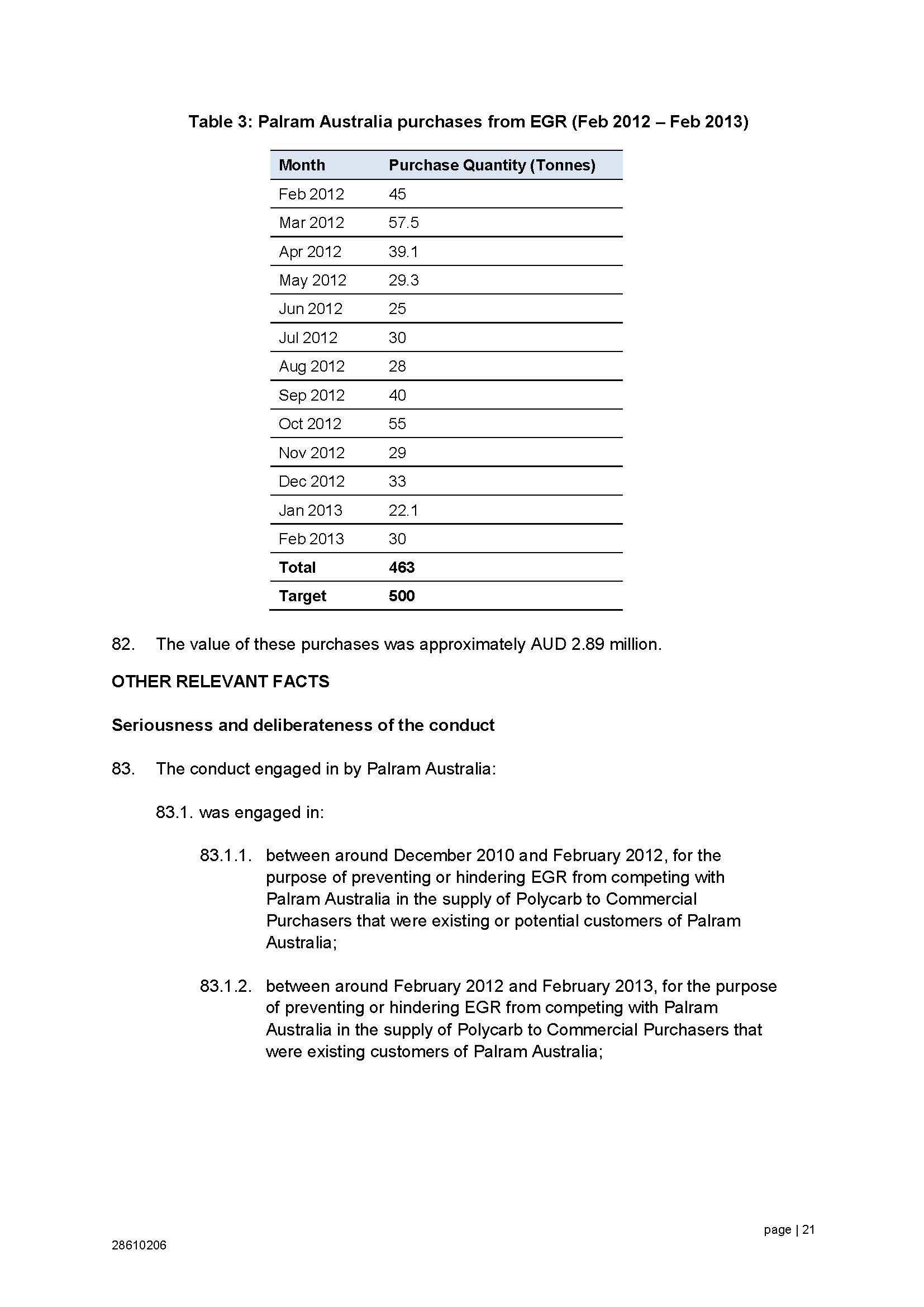

(a) make available to these participants detailed (otherwise confidential) commercial information about the relative contributions made by different categories of products sold by Palram Australia towards Palram Australia’s revenue and thereby (some measure of) the relative financial importance of these different products to Palram Australia’s business;

(b) (together with the Sales Percentage Information) enable these participants to calculate Palram Australia’s approximate annual revenue, this information being confidential and commercially sensitive for the reasons outlined in paragraphs 11 to 13 above, given that the value of total sales in the Distribution Market (as defined in paragraph 35 of the Statement of Agreed Facts) during the same period is stated at paragraph 36 of the Statement of Agreed Facts and in paragraph 68 of the Joint Submissions;

(c) (together with the Revenue Information) enable these participants to calculate Palram Australia’s market share, this information being confidential and commercially sensitive for the reasons outlined in paragraphs 18 to 20 below, given that the value of total sales in the Distribution Market (as defined in paragraph 35 of the Statement of Agreed Facts) during the same period is stated at paragraph 36 of the Statement of Agreed Facts and in paragraph 68 of the Joint Submissions;

(d) thereby provide a commercial and competitive advantage to these participants (to Palram Australia’s commercial and competitive disadvantage), by making available to them otherwise confidential, commercial information which they will be able to use in the course of their dealings with Palram Australia and each other.

32 In cross-examination, Ms Birnbaum-David was asked to explain how she would estimate Ampelite’s current prices if she knew Ampelite’s revenue six years ago. Mr Birnbaum-David did not answer the question directly. Eventually, she gave a lengthy response which was expressed in general terms and which emphasised “distribution margin” which, according to Ms Birnbaum-David was well known in the industry (although she did not state the well-known figure). The explanation also depended on knowledge of quantities sold.

33 When asked to agree that the statement of agreed facts and the joint submissions did not disclose the “distribution margin”, Ms Birnbaum-David answered non-responsively, stating that the information included quantities of purchases from EGR. Ms Birnbaum-David agreed that there was no information as to total quantities of polycarb acquired by Palram Australia and gave a non-responsive answer when asked to accept that there was no information as to total quantities of polycarb sold by Palram Australia during the 2010 to 2012 period (being the relevant period).

34 Eventually, Ms Birnbaum-David agreed that the only way that it would be possible to attempt to estimate prices from revenue information was by also knowing the total volume of sales from which the revenue was derived.

35 I have difficulty accepting Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence at face value where she did not give her evidence in a straightforward manner and her evidence as to her experience of matters affecting the Australian market was expressed at a high level and in the nature of assertion. Some of the difficulties in Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence may have reflected a difficulty communicating in English, which appeared not to have been her first language, and accordingly, I do not find that her non-responsive evidence was deliberately obstructive. However, I am not prepared to accept Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence as to the inferences able to be drawn from the revenue information without a plausible explanation of the underlying reasoning process that would be applied.

36 In particular, Ms Kate Morgan SC, senior counsel for the respondents, argued that I should accept Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence that the relevant market is “highly stable” so that the historical nature of the information could readily be used to draw inferences to Palram Australia’s future detriment. However, Ms Birnbaum-David’s affidavit did not give evidence to that effect. Rather, she asserted that experienced industry participants were aware of rates of growth in the industry over time and significant developments in the industry from which they could determine current figures from the historical ones. The basis of this assertion was not clear. Ms Birnbaum-David did not give evidence of her particular experience of the relevant market, saying only that she had participated in negotiations and other commercial dealings with a range of industry participants on behalf of Palram Australia. I was therefore not satisfied that I should accept that the information that is sought to be protected is of continuing commercial significance.

37 Accordingly, I am not satisfied that the revenue information could be used to draw reliable inferences as to Palram Australia’s current and likely future revenue. Further, I am not satisfied by Ms Birnbaum-David’s evidence that disclosure of the information would confer a significant commercial and competitive advantage to other industry participants in the absence of evidence of total sales and without precise evidence about the distribution margin that was said to be well-known.

Sales percentage information

38 The relevant information is Palram Australia’s estimate of the proportion of total sales of polycarb in the distribution market during the period December 2010 to February 2013 comprising an approximate total annual sales figure and an approximate percentage figure.

39 Ms Birnbaum-David gave the following evidence in her affidavit concerning the sales percentage information:

19. … In my experience, experienced industry participants are aware of significant developments in the industry, such as particular companies winning or losing significant customer contracts. With this awareness, in my view, experienced industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will likely be able to determine Palram Australia’s Current Sales Percentage Estimate by reference to the Sales Percentage Information.

20. Disclosure of the Sales Percentage Information to industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will thereby:

(a) make available to these participants information about Palram Australia’s market position, size, financial performance and operations;

(b) (together with the estimated value of total annual sales in the Distribution Market stated in para 36 of the Statement of Agreed Facts and in para 68 of the Joint Submissions) enable these participants to calculate:

(i) the approximate revenue Palram Australia derives from its sales of Polycarb, this information being confidential and commercially sensitive for the reasons outlined in paragraphs 14 to 16 above; and

(ii) (together with the Revenue Percentage Information) Palram Australia’s approximate annual revenue, this information being confidential and commercially sensitive for the reasons outlined in paragraphs 11 to 13 above; and

(c) thereby provide a commercial and competitive advantage to these other industry participants (to Palram Australia’s commercial and competitive disadvantage), by making available to them otherwise confidential, commercial information which they will be able to use in the course of their dealings with Palram Australia and each other.

40 As I have not accepted that revenue information, without more, would confer a significant commercial and competitive advantage to other industry participants, it follows that I do not accept that this information (said to enable inferences to be drawn about Palram Australia’s revenue) would confer such an advantage.

Value information

41 The value information comprises approximate dollar figures for specified quantities of polycarb purchased by Palram Australia from EGR during the periods between December 2010 and January 2012 and between February 2012 and February 2013.

42 Mr Birnbaum-David’s evidence was that:

22. Disclosure of the Value Information to industry participants, including Palram Australia’s competitors, customers and potential customers, will:

(a) (together with the actual and average monthly volumes of Polycarb purchased by Palram Australia from the First Respondent (EGR) during the period between December 2010 and February 2013 stated in the Statement of Agreed Facts and Joint Submissions) disclose to these participants the specific price paid by Palram Australia to EGR for Polycarb manufactured by EGR and supplied to Palram Australia;

(b) thereby:

(i) make available to industry participants detailed information about Palram Australia’s cost base, which estimate may in turn to be used to inform competitive pricing strategies;

(ii) give industry participants detailed insight into the margins achieved by Palram Australia on the supply of Polycarb in circumstances where, in my experience, experienced industry participants will likely be able to determine or, at the very least, accurately estimate the prices at which Palram Australia supplied Polycarb to its customers; and

(iii) give industry participants detailed insight into the prices at which Palram Australia supplies Polycarb to its customers, both during the relevant period and currently, in circumstances where the prices at which Palram Australia is able to supply Polycarb is approximately equivalent to those which it paid to acquire Polycarb and where current prices are approximately equivalent to those offered during the relevant period; and

(c) thereby provide a commercial and competitive advantage to these other industry participants (to Palram Australia’s commercial and competitive disadvantage), by making available to them otherwise confidential, commercial information which they will be able to use in the course of their dealings with Palram Australia and each other, including by Palram Australia’s competitors to inform competitive pricing strategies targeted at Palram Australia’s customers and potential customers and by Palram Australia’s customers and potential customers in negotiating supply terms , including price.

43 Ms Birnbaum-David agreed that the majority of polycarb that is supplied to Palram Australia comes from its parent company, Palram Industries. She said that it was possible to infer from the price charged by EGR to Palram Australia five years ago, the price charged by Palram Industries to Palram Australia now. Ms Birnbaum-David said that every supplier of polycarb to a distributor is charging about the same price, saying “there’s a market price of that”. Neither of these assertions was corroborated or accepted by the ACCC. I am not prepared to accept them without more probative evidence.

44 Accordingly, I do not accept that the approximate amounts paid by Palram Industries to EGR are currently relevant information about Palram Australia’s cost basis, or that the information could confer a commercial or competitive advantage on other industry participants.

Conclusions concerning revenue information, revenue percentage information, sales percentage information and value information

45 For the reasons give above, I am not satisfied that the information is of continuing commercial significance. If I am wrong, I am not satisfied that disclosure of the information is likely to cause a significant commercial and competitive disadvantage to Palram Industries.

46 Accordingly, I am not satisfied that a non-publication order in respect of this information is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice.

Kibbutz allowance information

47 The basis of the application to restrict access to this information was the personal and private nature of the information and the fact that it will not otherwise be disclosed. Having regard to the authorities set out above, these matters do not warrant a conclusion that a non-publication order in respect of this information is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice.

Relief

Declarations

48 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21(1) of the Federal Court Act: see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-438 per Gibbs J (“Forster”); Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission [1992] HCA 10; (1992) 175 CLR 564 at 581-582 per Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ; and Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (No 2) [1993] FCA 105; (1993) 41 FCR 89 at 99.

49 In Forster, at 437-438 (quoting Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448 per Dunedin LJ), Gibbs J stated that before making a declaration three requirements should be satisfied:

(1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(3) there must be a proper contradictor.

50 Each of these requirements is satisfied in this case. The proposed declarations relate to conduct that contravenes the CCA and the matters in issue have been identified and particularised by the parties with precision: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [35].

51 It is in the public interest for the ACCC to seek to have the proposed declarations made and for the proposed declarations to be made: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; (2007) ATPR 42-140 at [6] (“ACCC v CFMEU”). There is a significant legal controversy in this case which is being resolved, and the ACCC, as the public regulator under the CCA, has a genuine interest in seeking the declaratory relief.

52 Palram Australia and Ms Horesh are proper contradictors because both are respondents and are the subject of the proposed declarations. They therefore have an interest in opposing the making of the proposed declarations.

53 Where declarations are sought by consent, the Court’s discretion is not supplanted; however, the Court will not usually refuse to give effect to terms of settlement by declining to make orders where they are within jurisdiction and are otherwise unobjectionable: Acquire Learning at [96] per Murphy J referring to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Econovite Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 964 at [11] per French J (as his Honour then was).

54 The form of declarations ordered should not speak merely of the terms used in the CCA, without giving any content to those expressions and without indicating the gist of the findings made: Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 (“Rural Press”) at [89]-[90]. The proposed declarations contain sufficient indication of how and why the relevant conduct contravened the CCA: BMW Australia Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2004] FCAFC 167; (2004) 207 ALR 452 at [35], quoting Rural Press at [90].

55 Finally, having regard to the reasoning in ACCC v CFMEU at [5], the declarations sought are appropriate because they serve to:

(1) record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

(2) vindicate the ACCC’s claims that Palram Australia contravened the CCA, and that Ms Horesh was knowingly concerned, and involved, in those contraventions;

(3) assist the ACCC to carry out the duties conferred upon it by the CCA;

(4) inform the public about the contravening conduct of Palram Australia and Ms Horesh; and

(5) deter other corporations from contravening the CCA.

56 In the circumstances, it is appropriate for the Court to indicate its disapproval of the conduct of Palram Australia and Ms Horesh by making the declarations sought.

Pecuniary penalties

57 The parties seek an order that Palram Australia pay pecuniary penalties totalling $3,500,000 in relation to the two admitted contraventions, pursuant to s 76(1)(a) of the CCA.

58 In determining a penalty of appropriate deterrent value, s 76(1) of the CCA requires the Court to have regard to “all relevant matters including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under” Pt VI of the CCA, relevantly, to have engaged in any similar conduct.

59 The central consideration in determining pecuniary penalties is deterrence, both general and specific, because penalties must be set at such a level as to not merely be seen as “an acceptable cost of doing business”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [65]-[66]; Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [62] (“Optus v ACCC”); NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 292-293 (“NW Frozen Foods”).

60 Achieving a penalty of appropriate deterrent value is the purpose of having regard to all relevant factors, and of having recourse to the tools of analysis used when exercising the penalty fixing discretion, including the “course of conduct” (or “one transaction” principle) and the “totality” principle, both of which are referred to in more detail below.

61 The assessment of pecuniary penalties under s 76 of the CCA involves a similar process to that of criminal sentencing as described in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 (“Markarian”): see Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 118 at [43]. It involves assessing the relevant factors and synthesising a conclusion as to the appropriate penalty. The following propositions are derived from the reasons of Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ in Markarian at [27] to [39]:

(1) assessment of the appropriate penalty is a discretionary judgment based on all relevant factors but that careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick;

(2) it will rarely be appropriate for a court to start with the maximum penalty and proceed by making a proportional deduction from that maximum and the court should not adopt a mathematical approach of increments or decrements from a predetermined range, or assign specific numerical or proportionate value to the various relevant factors; and

(3) since the law strongly favours transparency, accessible reasoning is necessary in the interests of all, and, while there may be occasions where some indulgence in an arithmetical process will better serve the end, it does not apply where there are numerous and complex considerations that must be weighed.

62 Matters relevant to the assessment of a pecuniary penalty were also addressed by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd (1991) ATPR 41-076, 52, 152-52, 153. They are:

(1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(2) the amount of loss or damage caused;

(3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place;

(4) the size of the contravening company;

(5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market;

(6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

(8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

(9) whether the company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

63 Those matters were approved and expanded upon with the following additional considerations in NW Frozen Foods and J McPhee & Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365; (2000) 172 ALR 532:

(1) whether similar conduct has occurred in the past;

(2) the effect of the conduct on the functioning of the market and other economic effects of the conduct;

(3) the financial position of the contravening company; and

(4) whether the conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

64 In the CFMEU case, the plurality explained the desirability of the Court accepting an agreed proposed penalty, provided the Court is persuaded that what is proposed is appropriate, at [57] and [58] as follows:

[57] … [I]n civil proceedings there is generally very considerable scope for the parties to agree on the facts and upon consequences. There is also very considerable scope for them to agree upon the appropriate remedy and for the court to be persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy. Accordingly, settlements of civil proceedings are commonplace and orders by consent for the payment of damages and other relief are unremarkable. So are court-approved compromises of proceedings on behalf of infants and persons otherwise lacking capacity, court-approved custody and property settlements, court-approved compromises in group proceedings and court-approved schemes of arrangement. More generally, it is entirely consistent with the nature of civil proceedings for a court to make orders by consent and to approve a compromise of proceedings on terms proposed by the parties, provided the court is persuaded that what is proposed is appropriate.

[58] Possibly, there are exceptions to the general rule. There is, however, no reason in principle or practice why civil penalty proceedings should be treated as an exception. Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and, for the reasons identified in Allied Mills, highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty. To do so is no different in principle or practice from approving an infant’s compromise, a custody or property compromise, a group proceeding settlement or a scheme of arrangement.

65 At [64], their Honours adverted to the relevance of submissions made on behalf of the regulator as follows:

[I]t is consistent with the purposes of civil penalty regimes … and therefore with the public interest, that the regulator take an active role in attempting to achieve the penalty which the regulator considers to be appropriate and thus that the regulator’s submissions as to the terms and quantum of a civil penalty be treated as a relevant consideration.

Maximum penalties

66 Section 76(1A) of the CCA provides that the maximum penalty payable by a corporation for each act or omission to which the section applies, is the greatest of:

(1) $10 million (s 76(1A)(b)(i)); or

(2) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate (and any body corporate related to the body corporate) has obtained directly or indirectly from, and that is reasonably attributable to, the act or omission – three times the value of that benefit (s 76(1A)(b)(ii)); or

(3) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit – 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the period of 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred (s 76(1A)(b)(iii)).

67 Logan J explained the operation of s 76(1A) (as it stood at 1 January 2007) in the following way in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Limited (No 3) [2014] FCA 292; (2014) 234 FCR 325 at [8]:

[I]f it can be shown by the Commission that [a person has] obtained, directly or indirectly, a benefit that is reasonably attributable to a particular contravention, the body corporate can, depending upon the value of the benefit or size of its annual turnover, as defined, be exposed to a maximum penalty greater than $10 million in respect of that contravention.

68 In applying the statutory test set out in s 76(1A)(b) of the CCA, the applicable maximum penalties for each act or omission by Palram Australia are set out below.

Palram Australia’s first contravention

69 The maximum penalty for each act or omission by Palram Australia comprising the first contravention is $10 million, on the following basis:

(1) having regard to s 76(1A)(b)(ii), the parties cannot quantify benefits to Palram Australia of its contravening conduct because the extent to which that conduct resulted in deterring EGR from supplying or offering to supply Polycarb to commercial purchasers who were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia is unknown;

(2) Palram Australia’s turnover for the 12 month period ending February 2012 for the purposes of s 76(5) was approximately $20.3 million (s 76(1A)(b)(iii)); and

(3) the greatest of:

(b) 10% of the annual turnover of Palram Australia during the period of 12 months ending February 2012, being approximately $2.03 million,

is $10 million (s 76(1A)(b)(i), (iii)).

Palram Australia’s second contravention

70 The maximum penalty for each act or omission by Palram Australia comprising the second contravention is $10 million, on the following basis.

(1) having regard to s 76(1A)(b)(ii), the parties cannot quantify benefits to Palram Australia of its contravening conduct because the extent to which that conduct resulted in deterring EGR from supplying or offering to supply Polycarb to commercial purchasers who were existing customers of Palram Australia is unknown;

(2) Palram Australia’s turnover for the 12 month period ending February 2013 for the purposes of s 76(5) was approximately $22.376 million (s 76(1A)(b)(iii)); and

(3) the greatest of:

(a) $10 million; or

(b) 10% of the annual turnover of Palram Australia during the period of 12 months ending February 2013, being approximately $2.2376 million,

is $10 million (s 76(1A)(b)(i), (iii)).

Ms Horesh

71 The ACCC does not press its application for pecuniary penalties against Ms Horesh.

72 At all material times, Ms Horesh was a member of a kibbutz, an Israeli collective community.

73 In accordance with the rules of the kibbutz of which she is a member, Ms Horesh did not (and does not) own any assets or property. Instead, the kibbutz holds assets for the benefit of all its members, and provides shared housing, food and public services to those members.

74 Ms Horesh also did not (and does not) receive any salary, wages or other payments for her services to Palram Australia which were provided pursuant to labour services agreements between the Palram Group and the kibbutz.

75 Having regard to these matters, the only order sought in relation to Ms Horesh is an order that she be disqualified from managing corporations for a period of three years pursuant to s 86E(1) of the CCA. That order is considered below.

Relevant factors

The nature and extent of the conduct and the circumstances in which it took place

A. First contravention (December 2010 to February 2012)

76 The first contravention related to a variation dated 15 December 2010 (“variation”) to an earlier agreement entered into by Palram Australia and EGR on 24 March 2009.

77 On 24 March 2009, Palram Australia and EGR entered into a supply agreement, pursuant to which EGR manufactured polycarb to be purchased by Palram Australia (“supply agreement”). The agreement was executed by Ms Horesh, on behalf of Palram Australia, and Mr Horwill, on behalf of EGR.

78 The supply agreement was for an initial term of three years, but could be terminated without cause by either party on 60 days’ written notice on each 12 month anniversary. Palram Australia purchased polycarb from EGR under the terms of that agreement throughout the balance of 2009 and into 2010. Neither EGR nor Palram Australia sought to terminate the supply agreement during the period of its operation.

79 The supply agreement specified an estimated volume consumption of 300 tonnes per annum (subject to change based on Palram Australia’s actual sales).

80 Between around 12 April 2009 and 31 July 2009, the polycarb purchased by Palram Australia from EGR was supplied to Burnside Plastics, who then supplied it to commercial purchasers. On around 1 August 2009, Palram Australia acquired the distribution business and assets of Burnside Plastics and commenced distributing Polycarb to commercial purchasers who had previously acquired polycarb from Burnside Plastics. From this time, Burnside Plastics ceased distributing polycarb and the polycarb purchased from EGR was supplied by Palram Australia directly to commercial purchasers.

81 During the second half of 2010, Bunnings Warehouse, a large international hardware chain, conducted a review of its polycarb range, and invited Palram Australia to submit a proposal for the supply of polycarb to it. The proposal submitted by Palram Australia specified that some of the polycarb it sought to supply to Bunnings would be manufactured in Australia by EGR. Palram Australia viewed maintaining an adequate source of local supply as important to Bunnings’ choice of sole supplier.

82 In this context, EGR sought to negotiate an increase in the volume of polycarb that Palram Australia would acquire from EGR under the supply agreement. EGR also sought to be included as a named joint supplier to Bunnings in any agreement reached between Palram Australia and Bunnings for the supply of polycarb.

83 Between around July and December 2010, representatives of EGR and representatives of Palram Australia engaged in a series of negotiations about the demands described at [82]. Throughout these negotiations, representatives of EGR (in particular, Mr Horwill) made repeated statements to Palram Australia, to the effect that if Palram Australia did not agree to increase the volume of polycarb it would acquire from EGR in the event that its proposal to Bunnings was successful, then EGR would commence supplying polycarb directly to commercial purchasers that were existing and potential customers of Palram Australia in competition with Palram Australia.

84 The joint submissions referred to these statements (and other statements) as “threats”. I prefer not to use that word, which may imply incorrectly that Palram Australia’s contravening conduct is less serious because it was responsive to the misconduct of others. In oral submissions, Ms Morgan SC clarified that the Palram parties did not intend to traverse their admissions of contraventions of the CCA.

85 These statements were made in various oral and written communications, predominantly between Mr Horwill, Mr Rees and Ms Horesh. For example, on 22 July 2010, Mr Horwill sent an email to Ms Horesh which stated:

Just to clarify my position, if we are both successful … [with] Bunnings, I will require more business than 150 tonnes.

As Simon will tell you, Bunnings want to buy directly from EGR, but I have advised them that we work through Palram because you have distribution.

If we don’t get enough of the Bunnings Business we would have to go direct, which as you know is not what I want to do.

Let’s hope we get ALL the Bunnings business and there is enough to share around.

86 The parties identified the communications set out in paras 45 to 46, and 48 to 62 of the statement of agreed facts as other relevant communications.

87 On 15 December 2010, Mr Rees executed the variation on behalf of Palram Australia. The variation provided that, in the event that Palram Australia was granted the Bunnings sole supply contract, Palram Australia would increase the minimum quantity of polycarb it estimated it would acquire per annum from EGR from 300 tonnes to 600 tonnes. The variation expired on 24 March 2012 but could be terminated without cause by either party on 60 days’ written notice on 24 March 2011. Neither EGR nor Palram Australia sought to terminate the variation on 24 March 2011.

88 On or about 18 December 2010, Bunnings informed Palram Australia that it had been successful in its bid to become the sole supplier of polycarb to Bunnings.

89 Pursuant to the varied supply agreement (“varied agreement”) and the communications set out in paras 45 to 47, 49 to 52 and 54 to 62 of the statement of agreed facts, Palram Australia then engaged in the conduct which constituted the first contravention, namely:

(1) acquiring Polycarb from EGR between around December 2010 and February 2012;

(2) on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, Polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia; and

(3) for the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the distribution market within the meaning of s 47(10) of the CCA (i.e., for the purpose of preventing, hindering or substantially deterring EGR from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia).

90 By so doing, it engaged in exclusive dealing within the meaning of s 47(4) of the CCA, and thereby contravened s 47(1) of the CCA.

91 The amount of polycarb acquired from EGR by Palram Australia during the period of the first contravention was approximately 376 tonnes. The shortfall between this amount and the target amount of 600 tonnes under the varied agreement was predominantly the result of delays in realising the increase in sales Palram Australia anticipated it would achieve upon becoming the sole supplier of Polycarb to Bunnings, due to the time taken for Bunnings to sell existing stock (with consequently lower volumes of polycarb being purchased by Palram Australia from EGR).

B. Second contravention (February 2012 to February 2013)

92 The second contravention occurred in the context of the impending expiration of the varied agreement in March 2012.

93 From early 2012, EGR commenced taking active steps to supply polycarb to commercial purchasers, including employing two sales managers and a business development manager to (amongst other things) market polycarb manufactured by EGR under the brand “Polysun”.

94 At the same time, EGR and Palram Australia also sought to negotiate terms on which Palram Australia might continue to acquire polycarb from EGR after expiration of the varied agreement.

95 Again, representatives of EGR (in particular, Mr Horwill) made repeated statements to Palram Australia during these negotiations to the effect that EGR would seek to supply polycarb to commercial purchasers who were existing customers of Palram Australia in competition with Palram Australia, if Palram Australia did not agree to various matters.

96 On 25 January 2012, Ms Horesh telephoned Mr Horwill, Mr Bell and Mr McLellan of EGR. During that call, a discussion to the following effect took place:

(1) Ms Horesh said that Palram Australia would consider signing another supply agreement with EGR, for approximately 500 tonnes per year of polycarb, depending on the market’s demands;

(2) Mr Horwill asked what period of time Palram Australia intended to sign for;

(3) Ms Horesh said she personally preferred a year by year revolving agreement, and she saw it as a long term agreement, but Palram Australia had not yet discussed the fine details of such an agreement;

(4) Mr Horwill repeated numerous times that he demanded 1,000 tonnes and he could not understand why Palram Australia could not give this to him; and

(5) Mr Horwill said the bottom line was that if this was Palram’s final answer, then he would do his utmost to demolish or destroy all Palram Australia’s efforts to win Bunnings. He was fed up with his current position, he wanted to become the number one retail supplier in Australia and there was no reason why he would not be.

97 On 29 January 2012, Mr Horwill telephoned Ms Horesh. During that call, Mr Horwill said words to the following effect:

(1) he wanted to make sure Ms Horesh understood how serious he was. If Palram would not give him what he wanted, he would destroy them in the Australian market; and

(2) on top of the sales manager he had already employed, Mr Horwill was interviewing that coming Wednesday the top sales manager from Laserlite, who wanted to work in Queensland; and as of Thursday, he would have those two gentleman working for him, knocking on everyone’s door in Australia.

98 The parties identified the communications set out in paras 73, 74 and 76 of the statement of agreed facts as other relevant communications.

99 On 3 February 2012, Ms Horesh participated in a telephone conversation with Mr Horwill and another representative of EGR, Mr McLellan. This conversation is described in an internal Palram email sent by Ms Horesh on 5 February 2012 as follows:

We have talked (Arnon and I) to Rod Horwill and Simon McLallen [sic] of EGR on Friday. We have agreed to purchase 500 tons annually (March 2012 through February 2013) from EGR which will include our needs for the Greca profile in 5 colours (Bronze, Solar Grey, Clear, Opal and Cream) In Australia [sic]. The nature of the agreement will be similar to the previous supply agreement we have signed with them, on a yearly basis.

No penalties are involved if we failed to meet this target.

Our promise was a gentlemen’s promise. We gave our word, so we should try and meet this target. We have also mentioned that we might check other markets to which we could send some of that quantity.

Rod said that we will probably meet him in the market place but he will not interfere with our markets. This is his promise to Palram.

100 Pursuant to the communications set out in paras 73 to 78 of the statement of agreed facts, Palram Australia then engaged in the conduct which constituted the second contravention, namely:

(1) acquiring polycarb from EGR between around February 2012 and February 2013;

(2) on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia;

(3) for the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the distribution market within the meaning of s 47(10) of the CCA (i.e., for the purpose of preventing, hindering or substantially deterring EGR from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia).

101 By so doing, it engaged in exclusive dealing within the meaning of s 47(4) of the CCA, and thereby contravened s 47(1) of the CCA.

102 The amount of Polycarb acquired from EGR by Palram Australia during the period of the second contravention was approximately 463 tonnes.

The size and financial position of the contravenor

103 Palram Australia is a smaller mid-sized company, with warehouses and office facilities in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide. During the period between approximately December 2010 and February 2013, Palram Australia had approximately 35 employees. It now has approximately 50 employees.

104 Palram Australia’s annual turnover during the relevant period was between around $17 and $22 million per annum. Between December 2010 and February 2013, the sale of Polycarb formed approximately 65% to 70% of Palram Australia’s revenue.

105 Palram Australia’s sole shareholder was Palram Industries, a publicly listed company incorporated in Israel which has listed share capital of approximately $9.4 million. While a penalty is not being sought against the parent company, the size of the parent cannot be ignored when assessing the penalty that should be imposed on its subsidiary: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 559; (2002) 190 ALR 169 at [40].

Degree of market power, as evidenced by market share and ease of entry into the market

106 Palram Australia estimates that during the period December 2010 to February 2013, total annual sales of polycarb in the distribution market were approximately $42 million (on average per annum) and that Palram Australia’s sales amounted to approximately 30% of total sales.

107 During the period December 2010 to February 2013, there were three substantial distributors of polycarb in the distribution market, Palram Australia, Ampelite and Laserlite. Palram Australia estimates that these three suppliers made up more than approximately 90% of total annual sales of polycarb in the distribution market.

108 EGR commenced taking active steps to supply polycarb to commercial purchasers in early 2012, but did not rival the market share of the three substantial suppliers just referred to during the relevant period.

Whether the conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert

109 The conduct constituted serious contraventions of the CCA.

110 The conduct was engaged in by Palram Australia:

(1) between around December 2010 and February 2012, for the purpose of preventing, hindering or substantially deterring EGR from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia; and

(2) between around February 2012 and February 2013, for the purpose of preventing, hindering or substantially deterring EGR from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia.

111 The conduct comprising each of the first and second contraventions involved numerous individual acquisitions of polycarb from EGR, in accordance with the conditions, and for the purposes, described at [89(2)]-[89(3)] and [100(2)]-[100(3)]above.

112 It was undertaken to advance Palram Australia’s commercial interests in maintaining its commercial purchaser customers and the revenue derived by it from those customers.

113 Palram Australia also engaged in the conduct described above:

(1) to ensure that it maintained an adequate local source of supply, this being a factor Palram Australia viewed as important to Bunnings’ decision to appoint Palram Australia as its sole supplier of polycarb; and

(2) in circumstances where, throughout the period 2008 to 2012, EGR made repeated and persistent statements to Palram Australia to the effect that if Palram Australia did not acquire particular volumes of polycarb from EGR, EGR would take steps to distribute polycarb to Palram Australia’s commercial purchaser customers, including the statements reproduced in the statement of agreed facts.

114 The conduct was also covert in the sense that, while at least some of Palram Australia’s customers knew that it acquired polycarb from EGR, the condition on which Palram Australia did so was not public or known to Palram Australia’s customers.

Loss or damage

115 The parties cannot quantify the extent to which Palram Australia’s conduct in acquiring polycarb from EGR on the conditions set out in [89(2)] and [100(2)] above for the purpose of preventing, hindering or substantially deterring EGR:

(1) between around December 2010 and February 2012, from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia; and

(2) between around February 2012 and February 2013, from competing with Palram Australia in the supply of polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing customers of Palram Australia,

resulted in deterring EGR from supplying or offering to supply polycarb to those customers.

Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level

116 Palram Australia’s conduct involved the most senior management of Palram Australia, including Ms Horesh (who was a director of Palram Australia throughout the relevant period), and Mr Rees (who was the general manager of Palram Australia from on or around 1 August 2009). It also involved the most senior management of EGR (in particular, Mr Horwill).

Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the CCA, similar conduct in the past

117 Neither Palram Australia nor Ms Horesh has been previously found by a court to have contravened any provision of the CCA or to have engaged in similar conduct.

118 Since in or about January 2016, Palram Australia has:

(1) had a compliance policy and ethical code of conduct in relation to the CCA, with which employees are required to comply; and

(2) conducted regular annual internal CCA compliance training.

Co-operation

119 Palram Australia and Ms Horesh have provided appreciable co-operation to the ACCC, including by:

(1) engaging with and providing certain documents and extensive submissions voluntarily to the ACCC during the course of the ACCC’s investigation and following the commencement of proceedings;

(2) engaging from an early stage in good faith discussions with the ACCC about resolving the proceedings;

(3) assisting in the preparation of the statement of agreed facts;

(4) consenting to the proposed orders; and

(5) assisting in preparing and agreeing to the joint submissions regarding the alleged contraventions.

120 Co-operation with authorities in the course of investigations and subsequent proceedings is a mitigating factor that has in almost all previous cases resulted in a reduction of the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. A reduction on this account reflects the fact that such co-operation:

(1) is usually evidence of contrition and an acceptance of responsibility;

(2) increases the likelihood of co-operation in a way that furthers the object of the legislation;

(3) frees up the regulator’s resources, thereby increasing the likelihood that other contravenors will be detected and brought to justice; and

(4) reflects a willingness to facilitate the course of justice: Clean Energy Regulator v MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 (“MT Solar”) at [118] citing NW Frozen Foods at 293-294; Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; [2004] ATPR 41-993 at [55]; and Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70; (2008) 168 FCR 383 at [73]-[74] (“Mornington Inn”).

Comparable decisions

121 In The Queen v Pham [2015] HCA 39; (2015) 256 CLR 550 at [28], the plurality considered the use of comparable cases in the context of criminal sentencing proceedings and emphasised that the consistency that is sought is consistency in the application of the relevant legal principles. Prior cases do not set a “tariff” to be applied for particular types of contraventions, nor do they confine the Court’s discretion: Comcare v Transpacific Industries Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 500; (2015) 146 ALD 637 at [269].

122 In NW Frozen Foods at 295:

(1) it was noted that “[a] hallmark of justice is equality before the law, and, other things being equal, corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties”;

(2) but, that in the context of the CCA, “other things are rarely equal”; and

(3) that “[c]ases are authorities for matters of principle; but the penalty found to be appropriate, as a matter of fact, in the circumstances of one case cannot dictate the appropriate penalty in the different circumstances of another case”.

123 The ACCC and Palram Australia have not been able to identify any strictly comparable decisions. The Full Court has recognised that referring to penalties imposed in other cases involving vastly different circumstances can be of limited assistance: Optus v ACCC at [60].

“Course of conduct” principle

124 The ACCC and Palram Australia recognise that the various individual acquisitions comprising each of the first and second contraventions could be treated as separate contraventions. However, the parties submit, and I accept, that each act comprising Ampelite’s contraventions took place in the context of a wider course of conduct. This means that the Court may, if it considers it appropriate in the circumstances of the case, have regard to the “course of conduct” principle. In Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1, Middleton and Gordon JJ explained that principle at [39]-[42] as follows :

(1) where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality;

(2) its application requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality”, which is necessarily a factually specific enquiry;

(3) it is one of the applicable sentencing principles that guide the Court in the exercise of its sentencing discretion; and

(4) it is a tool of analysis which the Court is not compelled to use, as the exercise of its sentencing discretion remains a matter of judgment to be exercised according to the facts of each case and having regard to conflicting sentencing objectives.

125 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) ATPR 42-557 at [424] (“Cement Australia”), the Full Court recently confirmed that identifying whether multiple contraventions constitute a single course of conduct, or separate instances of conduct, is of paramount importance “so as to ensure that an appropriate deterrent effect is achieved by the imposition of the penalty or penalties in respect of [the] particular conduct”. This is because the “deterrent effect in respect of a civil penalty (at both a specific and general level) is measured by reference to the nature of the conduct for which it is imposed”.

126 The Full Court further considered the application of the principle in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 254 FCR 68. At [148] and [149] (“ABCC v CFMEU”), the Court stated:

[148] The important point to emphasise is that, contrary to the Commissioner's submissions, neither the course of conduct principle nor the totality principle, properly considered and applied, permit, let alone require, the Court to impose a single penalty in respect of multiple contraventions of a pecuniary penalty provision. There is no doubt that, in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should consider whether the multiple contraventions arose from a course or separate courses of conduct. If the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct, the penalties imposed in relation to the contraventions should generally reflect that fact, otherwise there is a risk that the respondent will be doubly punished in respect of the relevant acts or omissions that make up the multiple contraventions. That is not to say that the Court can impose a single penalty in respect of each course of conduct. Likewise, there is no doubt that in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should, after fixing separate penalties for the contraventions, consider whether the aggregate penalty is excessive. If the aggregate is found to be excessive, the penalties should be adjusted so as to avoid that outcome. That is not to say that the Court can fix a single penalty for the multiple contraventions.

[149] In an appropriate case, however, the Court may impose a single penalty for multiple contraventions where that course is agreed or accepted as being appropriate by the parties. It may be appropriate for the Court to impose a single penalty in such circumstances, for example, where the pleadings and facts reveal that the contraventions arose from a course of conduct and the precise number of contraventions cannot be ascertained, or the number of contraventions is so large that the fixing of separate penalties is not feasible, or there are a large number of relatively minor related contraventions that are most sensibly considered compendiously. As revealed generally by the reasoning in [Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 326 ALR 476], there is considerably greater scope for agreement on facts and orders in civil proceedings than there is in criminal sentence proceedings. As with agreed penalties generally, however, the Court is not compelled to accept such a proposal and should only do so if it is considered appropriate in all the circumstances.

127 The ACCC and Palram Australia submitted that the first and second contraventions have different factual and legal characteristics so as to give rise to two separate and distinct courses of conduct, each of which should be separately penalised.

128 The first contravention arose out of the varied agreement and related to communications between Palram Australia and EGR in the context of Bunnings’ range review in the second half of 2010. At this time, EGR was not yet active as a distributor of polycarb to commercial purchasers. The relevant contravening conduct involved Palram Australia acquiring polycarb from EGR between around December 2010 and February 2012, on the condition that EGR would not supply, or seek to supply, polycarb to commercial purchasers that were existing or potential customers of Palram Australia. The first contravention involved a large number of discrete acquisitions of polycarb during the period around December 2010 to February 2012. There is a close factual and legal interrelationship between each of these acquisitions, as they were all made pursuant to the same agreement containing the relevant condition. In these circumstances, ACCC and Palram Australia jointly submitted that it is appropriate to impose a single penalty for the first contravention, including because it would be impractical to fix separate penalties for each of the individual acquisitions in relation to the first contravention.