FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association v Qantas Airways Ltd [2018] FCA 1065

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN LICENCED AIRCRAFT ENGINEERS ASSOCIATION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent CHRISTOPHER TOBIN Second Respondent NICHOLAS SAUNDERS Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Amended Originating Application and the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim are dismissed.

2. The proceeding is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 The Applicant in the present proceeding is the Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association (the “Association”).

2 There are three Respondents to the proceeding. The First Respondent is Qantas Airways Limited (“Qantas”); the Second Respondent is Mr Christopher Tobin; and the Third Respondent is Mr Nicholas Saunders. At the relevant time, Mr Tobin was employed by Qantas as Manager – Sydney Aircraft Maintenance and Customer Experience; Mr Saunders was employed by Qantas as Senior Manager – Industrial Relations.

3 The proceeding has its origins in a review undertaken by Qantas in December 2015 of the number of surplus licenced aircraft maintenance engineers. It concluded that it had a surplus of 46.5 full time equivalent positions in Sydney.

4 Qantas notified the Association in January 2016 of its conclusions. Mr Stephen Purvinas, the Federal Secretary of the Association, responded by informing Qantas of his belief that there had been a contravention of the consultation requirements imposed by the Licensed Aircraft Engineers (Qantas Airways Limited) Enterprise Agreement 10 (the “Enterprise Agreement”). Meetings followed. In May 2016 Mr Purvinas repeated his concern to Qantas as to the alleged failure to consult.

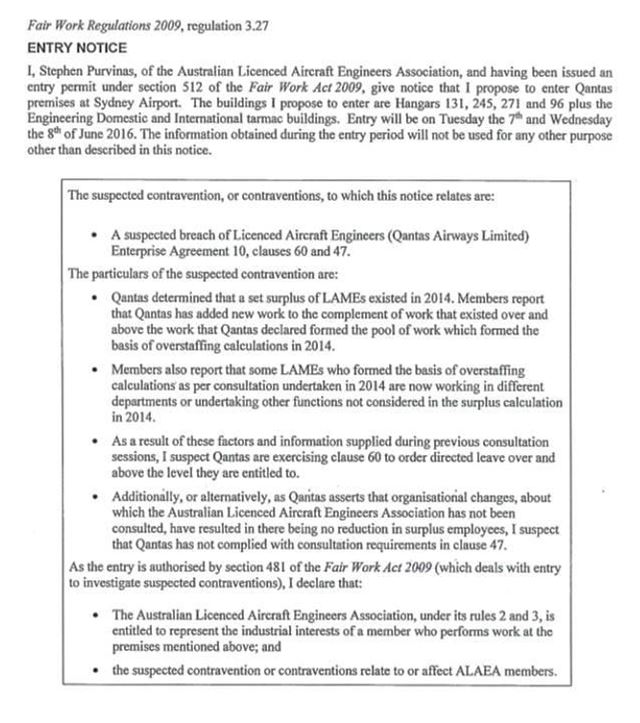

5 In June 2016, Mr Purvinas sought to exercise his right of entry as a permit holder to Qantas premises and to seek access to documents. The Entry Notice he provided to Qantas dated 3 June 2016 identified suspected contraventions of cll 47 and 60 of the Enterprise Agreement. Mr Purvinas gained entry to the premises on 7 and 8 June 2016 but no documents were produced on either occasion.

6 In September 2016, the Association filed in this Court an Originating Application seeking declaratory relief against Qantas that it had contravened ss 482 and 502 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). Declaratory relief was also sought against both Mr Tobin and Mr Saunders as to their contravention of ss 482 and 502. Messrs Tobin and Saunders were said to have been “involved in” the contraventions within the meaning of s 550 of the Fair Work Act. Further relief was also sought, including an order for the imposition of pecuniary penalties.

7 It is concluded that the proceeding should be dismissed. Qantas, it is concluded, was not required to produce and make available for copying the documents Mr Purvinas requested.

THE ENTERPRISE AGREEMENT

8 The provisions of the Enterprise Agreement which assume relevance are cll 47, 55 and 60.

9 Clause 47 provides as follows:

47. INTRODUCTION OF CHANGE

47.1 Qantas’ duty to notify

47.1.1 Where Qantas has made a definite decision to introduce major changes, including changes in minor ports, production, program, organisation, structure or technology that are likely to have significant effects on employees, Qantas shall notify the employee who may be affected by the proposed changes and at the request of the affected employee(s) the Association.

47.1.2 “Significant Effects” include termination of employment, major changes in the composition, operation or size of Qantas’ workforce or in the skills required; the elimination or diminution of job opportunities, promotion opportunities, or job tenure; the alteration of hours of work; the need for retraining or transfer of employees to other work or locations and restructuring of jobs. Provided that where this Agreement makes provision for alteration of any of the matters referred to herein an alteration shall be deemed not to have significant effects.

47.2 Qantas’ duty to consult

47.2.1 Qantas shall consult with the employees affected and at the request of the affected employee(s) the Association or other employee representative, inter alia, the introduction of the changes referred to in clause 47.1, the effects the changes are likely to have on employees, measures to avert or mitigate the adverse effects of such changes on employees and shall give prompt consideration to matters raised by the employees and/or their union or other employee representative in relation to the changes.

47.2.2 The consultation shall commence as early as practicable after a firm decision has been made by Qantas to make the changes referred to in clause 47.1.

47.2.3 For the purpose of such consultation, Qantas shall provide to the employee’s concerned and at the request of the affected employee(s) the Association or other employee representative, all relevant information about the changes including the nature of the changes proposed; the expected effects of the changes on the employees and any other matters likely to affect employees provided that Qantas shall not be required to disclose confidential information the disclosure of which would be inimical to his/her interests.

10 Clause 55 is directed to redundancies. That clause provides in part as follows (without alteration):

55. REDUNDANCY

55.1 The Company recognises the concern expressed by the employees and their representatives relating to job security and will seek to ensure that job security is maintained.

…

55.11 Definitions

55.11.1 “Employee” means a person who has been employed on a full time or part basis for a period of one year or more and does not include persons employed on a fixed term or casual basis.

55.11.2 “Redundancy” means a declaration by Qantas that an employee or employees are surplus to labour requirements because the quantity of their work has diminished.

55.11.3 “Retrenchment” means the termination of employment of an employee by Qantas for reason of redundancy.

55.11.4 “Part time employee” means an employee as defined by clause 13.3 – Permanent part time employee. All benefits of this clause will be paid on a proportionate basis.

11 Clause 60 provides as follows (without alteration):

60. SURPLUS MANAGEMENT

60.1 During the life of this Agreement, Qantas will, subject to clause 55 of this Agreement, use a program of directed annual leave and long service leave, and voluntary redundancies, as the method for the management of surplus employees covered by the Agreement, before declaring positions covered by the Agreement compulsorily redundant.

60.2 During the life of the Agreement, expressions of interest in voluntary redundancy will be invited on at least two (2) occasions each year to mitigate the effects of any leave burn program that may be in operation from time to time.

60.3 In order to facilitate the program of directed annual leave and long service leave to manage surplus employees during the life of this Agreement:

60.3.1 employees may take, and be directed by the Company to take, single days or other periods of annual leave. Any provision of this Agreement will, to the extent that the clause restricts the taking or direction of annual leave in single days or other periods, be of no effect;

60.3.2 employees may take, and be directed by the Company to take, long service leave in broken periods, including in blocks of 7,8 and/or 15 consecutive calendar days, in accordance with clause 4H.3 of Appendix H of this Agreement. Any provision of this Agreement will, to the extent that the clause restricts the taking or direction of long service leave in blocks of 7, 8 and/or 15 consecutive calendar days, be of no effect; and

60.3.3 the parties agree that Qantas directing employees to take annual leave and long service leave is in these circumstances is reasonable.

60.3.4 the parties will take such steps as are necessary to ensure the program of directed annual leave, long service leave and voluntary redundancies complies with applicable legislation.

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF LEAVE BURN & THE ISSUES CANVASSED

12 Without being exhaustive, the implementation by Qantas of its “leave burn program”, its relevance to the surplus of licenced aircraft maintenance engineers and the concerns raised by Mr Purvinas should be briefly outlined.

13 The issue in the present case can be traced back to a letter dated 5 January 2016 from Mr Tobin to Mr Purvinas, which stated in part as follows:

Dear Steve,

Leave Burn Program (Clause 60 LAME EA 10)

The purpose of this letter is to update you on the Company’s preparations for the 2016 Leave Burn Program.

Number of surplus employees

As you are aware the purpose of the Leave Burn Program is to be a “method for the management of surplus employees” covered by the Licensed Aircraft Engineers (Qantas Airways Limited) Enterprise Agreement 10. Accordingly, the Company uses the total number of surplus employees as the basis for setting leave burn targets. For the 2016 Leave Burn Program the company conducted a review of the number of surplus employees in Sydney and Melbourne as at 17 December 2015. We have summarised the changes (including the reasons for the changes) in the table below:

There then followed the assessment as to the “[e]ffective number of surplus employees as at 17 December 2015” in both Sydney and Melbourne. The letter indicated that there was a surplus of 46.5 full time equivalent employees in Sydney and no surplus in Melbourne. The letter continued in part as follows (without alteration):

Calculation of the leave burn target

…

To simplify communications and make leave planning easier for employees we will be repeating our last practice of advising employees of their total individual leave targets for the year (i.e. combined 2016 accrual and leave burn targets). Based on feedback from staff from the 2015 program, the ‘hours’ target will also be converted into a ‘work days’ target. This number will vary by section (based on the length of shifts), but represents the same number of hours for each employee.

Qantas will shortly commence communications with employees about the 2016 Program. We will also work with employees over the course of the year to ensure they meet their individual leave clearance targets. As in 2015, we will periodically review the leave burn requirements and design of the Program and may make changes based on the circumstances of the business at that time.

Should you wish, the company is willing to provide you with a face to face briefing on the 2016 Program. If you would like to accept this offer please advise of your availability to meet.

14 Mr Purvinas responded by way of email on the same day. In its entirety, that email stated as follows:

Hi Nick,

Read your letter. I think you may be breaching the consultation procedures by seeking a meeting with us to discuss leave burn but already advising staff of the outcome of the meeting in the form of time they will need to take off. The figures look incorrect to us, for example we already know that 5 maintenance watch positions are available that will be filled by Sydney LAMEs. You do know that Qantas were already heavily fined for announcing the outcome of consultation before it commenced. That being the case I immediately request that Qantas retract any notifications sent to staff asking them to declare their preferred leave blocks by the date in the communications. I’ve added Chris Nassenstein to the email chain also so should the retraction request be ignored, a judge could again say that the breach was known in advance and at the highest levels of the company.

As for a meeting, is Monday 25th Jan ok?

Cheers

Steve P

15 According to Mr Purvinas, there were “several meetings” between Qantas and the Association between January 2016 and May 2016. There was (for instance) a meeting held on 27 April 2016 when Mr Purvinas, on his account, “again raised [his] concerns that Qantas was contravening the Agreement by directing employees to take annual leave in circumstances where it was not warranted and there had not been consultation about any workplace change that necessitated a leave burn program”. He set forth his concerns in a letter dated 13 May 2016.

16 Qantas provided the following response to Mr Purvinas in a letter dated 27 May 2016 (without alteration):

We refer to your letter dated 13 May 2016 and recent meetings and correspondence with you regarding the leave burn program under the Licensed Aircraft Engineers (Qantas Airways Limited) Enterprise Agreement 10 (EA 10).

We understand that it has been the position of the ALAEA in recent months that Qantas Airways Limited (Qantas) is not entitled to continue with its leave burn program on the basis that it does not employ a surplus number of LAMEs. Your recent letter however now alleges that Qantas has ‘failed to consult the ALAEA’ and raises concerns about the ‘manner [in which Qantas] has implemented the Leave Burn Program having regard to any surplus and the leave accruals of employees’.

Your allegation that Qantas does not employ a surplus number of LAMEs has already been the subject of extensive correspondence and discussions with you. Accordingly, Qantas does not propose to comment further on this matter in this letter.

In relation to your allegation that Qantas has ‘failed to consult the ALAEA’, can you please detail the basis for your allegation so that we may properly respond, including by identifying the specific matters which the ALAEA consider to be subject to consultation and how Qantas has supposedly failed to consult in relation to each matter.

Similarly, in relation to your allegation regarding the ‘manner’ in which Qantas has implemented the leave burn program ‘having regard to any surplus and the leave accruals’, we ask that you explain what you mean by this and how and why the manner in which Qantas has implemented the leave burn program has given rise to a concern that Qantas has contravened EA 10. In providing your explanation, could you also explain why you consider the directions that have been issued to LAMEs to take period(s) of leave are not reasonable and why the amount of leave that LAMEs have been directed to take is disproportionate to the actual surplus.

Notwithstanding the above and to assist you in responding to the above matters, Qantas confirms the following information:

1 There is currently a surplus of 46.5 LAMEs;

2 All directions to take leave under the leave burn program have been issued only for the purpose of managing the surplus in the number of LAMEs;

3 Qantas is currently directing LAMEs in workgroups affected by the surplus to take period(s) of leave under the leave burn program only if the LAME’s combined annual leave and long service leave balance exceeded 240 hours as at the commencement of the program for 2016. The reason for this is that LAMEs with a lower leave balance were considered to have insufficient leave to participate in the leave burn program in 2016;

4 in determining which LAMEs should be directed to take period(s) of leave, Qantas has had regard to whether the LAME has submitted sufficient leave to fully account for their individual target under the leave burn program for 2016.

In addition, we note your request for a range of different documents. Qantas has considered your request but is of the view that the information requested including in relation to staff lists, work projections, resource allocation methodology, customer contracts and upcoming projects is either commercially sensitive information that Qantas is not in a position to provide or does not appear to be relevant to the allegations that you have made.

We look forward to receiving the information requested at your earliest convenience. Following which we would be happy to meet with you to discuss the additional concerns raised in your recent letter.

17 By the commencement of June 2016, Mr Purvinas maintained that he had “formed a firm view that it was not possible for Qantas to hold a position that Sydney was overstaffed by 46.5 LAMEs”.

18 On 1 June 2016, Mr Purvinas sent a further letter to Qantas referring to the 27 April 2016 meeting and to the 13 and 27 May 2016 correspondence. The 1 June 2016 letter continued in relevant part as follows (without alteration):

You maintain that the alleged surplus warrants what the ALAEA considers to be excessive and unlawful directions to take annual leave.

Our concerns in relation to a failure to consult include in relation to the following:

i. The missed opportunity for the parties to work together to identify opportunities to source work for ALAEA members working in Sydney.

ii. The lack of visibility on how Qantas have sourced some new work but have not adjusted the alleged surplus.

iii. That a combination of the above points may lead to ALAEA members being made redundant when all staff in Sydney exhaust accrued leave balances.

iv. That the rate at which leave is being exhausted is too great considering the matters that we could have discussed if formal consultation had occurred.

The questions raised in your correspondence are disingenuous having regard to our previous correspondence regarding this matter and our meeting on 27 April 2016.

Your correspondence has failed to allay my reasonable suspicions that Qantas is contravening the EA. Accordingly, unless you indicate by midday Friday 3 June 2016 that you intend to provide the information and documents requested by the ALAEA, I intend to exercise my Right of Entry to inspect documents.

19 There thereafter followed the giving of an Entry Notice and attendance by Mr Purvinas at the Sydney Airport premises of Qantas.

THE ENTRY NOTICE & THE DOCUMENTS SOUGHT

20 The form and content of the Entry Notice relied upon by Mr Purvinas, being that provided to Qantas on 3 June 2016, was relevantly as follows:

21 The documents to which access was sought were identified by Mr Purvinas in his affidavit as follows:

“The daily workload sheets for Sydney International Terminal for each day of the previous 6 weeks”;

“The daily workload sheets for Sydney Aircraft Maintenance for each day of the previous 6 weeks”;

“Maintenance Memo M16-1685 regarding new work for in-flight entertainment systems”;

“[T]he email sent by a manager David Perks to staff with M16-1685 attached discussing the timeframe for IFE work to be returned to Qantas”;

“[A]ny memorandum of understanding (MOU) that was in operation for the four original Sydney departments, SAM, SIO, SDO and CE as stood in 2014 when original manning calculations were made to establish how many staff were required post redundancy program”;

“[A]ny memorandum of understanding (MOU) that was in operation for the four original Sydney departments, SAM, SIO, SDO and CE (including any MOU to cover 737 reconfiguration work) as stood on 5th Jan 2016 when it is claimed that management had calculated the 2016 leave burn overstaffing level to be 46.5 additional staff”;

“[A]ny memorandum of understanding (MOU) that was in operation for the four original Sydney departments, SAM, SIO, SDO and CE (including any MOU to cover 737 reconfiguration work) on 7th June 2016”;

“[T]he Budget and Forecast (B&F) documents used by Qantas as referenced at point 1.6 of the 145 Maintenance Exposition (MOE) for all Australian departments where LAMEs work as stood in 2014 when original manning calculations were made to establish how many staff were required post redundancy program”;

“[T]he Budget and Forecast (B&F) documents used by Qantas as referenced at point 1.6 of the 145 Maintenance Exposition (MOE) for all Australian departments where LAMEs work as stood on 5th Jan 2016 when it is claimed that management had calculated the 2016 leave burn overstaffing level to be 46.5 additional staff”;

“[T]he Budget and Forecast (B&F) documents used by Qantas as referenced at point 1.6 of the 145 Maintenance Exposition (MOE) for all Australian departments where LAMEs work on 7th June 2016”; and

“[T]he documents Chris Tobin used to determine that Qantas had 46.5 additional staff to complete the projected work for 2016 as used by him on 5th January 2016”.

Mr Purvinas in his affidavit also set forth the reasons why he sought to inspect each of these classes of documents. Objection was taken to much of this evidence upon the basis that Mr Purvinas was purporting to express an “opinion” about particular matters. But no question during the proceeding was raised as to the above classes of documents being the ones to which access was sought. The objections to evidence have been noted but may be placed to one side. The resolution of the argument as to whether the documents fell within the right conferred by s 482(1)(c) of the Fair Work Act, it is concluded, is to be resolved by reference to the description of the documents provided by Mr Purvinas rather than by reference to what he thought about the relevance of the documents or how those documents could be employed to address his suspicions of contraventions.

22 Having received a copy of the Entry Notice, Qantas responded in a letter dated 6 June 2016. That letter provided in part as follows:

Reasonable suspicion and particulars of the suspected contraventions

We understand from correspondence and discussions with you this year that the ALAEA opposes the leave burn program.

Initially this was on the basis that the ALAEA asserted that a surplus did not exist, but now appears to be on the basis that there have been changes to the surplus, and Qantas has not consulted with the ALAEA in relation to each and every change. Qantas has made a number of requests for you to explain the basis on which the ALAEA makes this assertion, but, to date, no explanation has been forthcoming. Your most recent correspondence of 1 June 2016 and your entry notice of 3 June 2016 do not assist in this regard.

In circumstances where you are now seeking to exercise rights of entry in relation to this matter, it is incumbent on you (at the very least) to detail what you consider to be Qantas’s consultation obligations in relation to the leave burn program, when you say those obligations arose, and why you consider that Qantas has not met these obligations. Simply asserting a failure is not sufficient.

We also note that the ALAEA asserts that the amount of leave that LAMEs are being directed to take under the leave burn program is excessive. Again, despite a number of requests for you to explain why the ALAEA makes this assertion, only superficial explanations have been offered. For example, no attempt has been made to identify the workgroups to which the ALAEA’s concerns relate and why the amount of leave required to be burned by LAMEs in those workgroups is considered to be excessive.

In light of the above, Qantas does not accept that you are entitled to enter the buildings or exercise a right of entry under s.482 of the FW Act on 7 or 8 June 2016.

Inspection of records or documents

Based on recent correspondence, we anticipate that you are seeking to enter the identified buildings to inspect records or documents. As you are aware, you are only entitled to inspect, or make copies of, records or documents that:

1. are directly relevant to the suspected contraventions; and

2. are not non-member records or documents,

(s.482(1)(c) of the FW Act).

Given the lack of detail regarding the asserted contraventions, Qantas is presently not in a position to identify whether there are any such documents kept in the identified building (or accessible from a computer in those buildings).

Next steps

Although Qantas does not accept you have a right to enter on this occasion, Qantas is nevertheless prepared to facilitate your entry into the buildings specified in your entry notice on 7 and/or 8 June 2016. When seeking to enter please ensure that you report to security at the entrance to the Jetbase and ask for Chris Tobin, who will accompany you during your entry. Should you wish to interview any LAMEs about the suspected contravention during your entry, please let Chris know upon your arrival so that appropriate arrangements (including arranging a suitable meeting room) can be made to facilitate any such interviews. Please note that Chris will not be in a position to provide access to records or documents during your visit given the issues set out above. However, if there are specific records or documents that you wish to access following your visit, can you please provide me with a notice under s.483 of the FW Act which identifies clearly the records or documents that you are seeking access to and why you consider them to be directly relevant to a suspected contravention of EA10 (noting the issues set out above) so that any access can be facilitated in an appropriate way.

23 Mr Purvinas attended at the Qantas premises on 7 June 2016 at about 10.30am and was granted access. He interviewed some members of the Association about their working hours and the directions to take leave. He requested access to documents. There was a meeting on 7 June 2016 at about 3.00pm between Messrs Purvinas, Tobin and Saunders. According to Mr Tobin, the following conversation took place:

Mr Purvinas: I do not need to speak to any more employees. And I expect I know the outcome, but I have to ask, can I have access to:

(i) daily workload sheets for SIT for every day for the last 6 weeks;

(ii) daily workload sheets for SAM for every day for the last 6 weeks;

(iii) maintenance memo number M16-1685;

(iv) the email sent by Dave Perks to staff under his control which relates to IFE, refers to Maintenance memo M16-1685 and sets out a timeline for implement the insourcing;

(v) any MOUs for cabin experience, SAM, SIO, SDO and whichever MOU covers the 737-800 reconfiguration, as they existed at the time the surplus was first calculated in 2014, at 5 January 2016, and presently;

(vi) the budget and forecast model referred to in Part 1.6 of the 145 Maintenance exposition for all engineering departments nationally where LAMEs perform work, as these models existed at the time the surplus was first calculated in 2014, at 5 January 2016, and presently; and

(vii) any documents used by Chris Tobin when preparing his letter of 5 January 2016 to determine that 46.5 was the surplus of staff over what was required to complete the projected work for 2016.

Mr Saunders: We still don’t have sufficient particulars to properly consider your request and determine what documents you are entitled to.

Mr Purvinas: Fine, then I am ready to leave.

Mr Saunders gave a substantially similar account of the conversation.

24 Mr Purvinas again attended at the Qantas premises on 8 June 2016, was again granted access and again requested access to the documents. Mr Saunders again denied access to the requested documents. According to Mr Saunders, the following conversation took place at about 9.30am:

Mr Purvinas: I have to ask you again, will you provide me with the documents I have requested?

Mr Saunders: You have not provided any further information to put us in a position where we are able to identify which documents might be relevant to any suspected contravention.

Mr Tobin: Would you like to speak to any LAMEs today?

Mr Purvinas: Yes. I would like to speak to Bradley Cox and Peter Bacon.

Mr Purvinas then proceeded to interview some persons. At about 11.00am there was then the following conversation between Mr Purvinas and Mr Saunders:

Mr Purvinas: I have spoken to all of the LAMEs that I wish to speak to today. I suspect that I know the answer, but I am asking again, will you provide me with access to the documents that I have requested?

Mr Saunders: Qantas’s position has not changed since this morning. You have not provided us with enough information to enable Qantas to properly consider your request and determine which documents you are entitled to, and have provided no further information of the kind requested in Sandra’s letter.

Mr Purvinas: Ok then, I am finished here.

The reference to “Sandra’s letter” is a reference to the 6 June 2016 letter from Qantas.

25 The accounts given of the conversations on 7 and 8 June 2016 by Messrs Tobin and Saunders are accepted.

THE FAIR WORK ACT

26 The right of entry onto premises is addressed in Pt 3-4 of the Fair Work Act.

27 Within that Part, s 481 confers a right of entry on a permit holder to investigate suspected contraventions of the Fair Work Act or a “fair work instrument” and s 484 confers a right of entry on a permit holder for the purposes of holding discussions with employees. A “fair work instrument” includes an enterprise agreement: Fair Work Act s 12.

28 Section 481, together with a number of other provisions, should be briefly mentioned with a view to setting forth the balance sought to be struck by the Legislature when adjusting the competing rights of those seeking to exercise a statutory right of entry and the rights of occupiers; the purposes of which a statutory right of entry may be exercised; the rights that may be exercised by a permit holder; and the requirements to be satisfied when seeking to exercise those rights.

The balance struck – those seeking entry & the rights of occupiers

29 The statutory rights conferred upon permit holders are rights which diminish the common law rights of occupiers to determine who may enter and remain upon their property.

30 The statutory rights conferred, it is respectfully considered, should thus be construed no more widely than is necessary to give effect to the statutory object and purpose for which the right is conferred. When addressing s 484 of the Fair Work Act in Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union v Fair Work Australia [2012] FCAFC 85, (2012) 203 FCR 389 at 407, it was there observed:

[63] … There is much to be said for the view that the statutory right of entry conferred on a permit holder by s 484 should not be construed as conferring any greater right than is necessary to achieve the statutory objective. The common law rights of an occupier, on this approach, are only to be diminished to the extent absolutely necessary to give effect to the right conferred. Subject only to the requirement that an occupier make a “reasonable request”, the balance that the Legislature has sought to achieve between granting a statutory right of access and the consequent diminution of the common law rights of an occupier is thereby struck. An occupier, on this approach, need not be further involved itself in promoting or accommodating the interests of those seeking entry.

Justice Tracey agreed with this reasoning: [2012] FCAFC 85 at [30], (2012) 203 FCR at 400. In developing this approach, it was later observed in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Billiton Nickel West Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 991, (2017) 268 IR 355 at 364 to 365:

[37] … Although the rights conferred are “beneficial ones [which] should be construed with an eye on the important role of organisations in protecting their members” (Independent Education Union of Australia v Australian International Academy of Education Inc [2016] FCA 140 at [109] per Jessup J), they remain rights which are not “untrammelled” by legislative constraints. This approach to the construction of provisions such as s 484 sits comfortably with the well-accepted proposition that “clear and unambiguous words” are required before common law rights are abolished or modified: cf. Bropho v Western Australia (1990) 171 CLR 1 at 17 per Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ. “Statutory authority to engage in what otherwise would be tortious conduct”, it has been said, “must be clearly expressed in unmistakable and unambiguous language”: Coco v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 427 at 436 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Gaudron and McHugh JJ. See also: Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1 at [43] per French CJ.

31 The need to “balance both the rights of organisations and those of the occupier” was also referred to by Bromberg J in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCA 802, (2017) 252 FCR 198. His Honour there observed (at 209 to 210):

[47] It is apparent from the objects of Part 3-4 contained in s 480 that, in providing a regime for the exercise of rights of entry, the FW Act seeks to balance both the rights of organisations and those of the occupier: Australian Meat Industry Employees’ Union v Fair Work Australia (2012) 203 FCR 389 at [59] (Flick J, with whom Tracey J agreed); and Maritime Union of Australia v Fair Work Commission (2015) 230 FCR 15 at [15] (North, Flick and Bromberg JJ). That balance is in part reflected in the imposition of various conditions upon the exercise of a right of entry … It is also reflected in the reciprocity apparent in ss 500 and 502 which collectively provide protection to a permit holder from being hindered and obstructed but also prohibit the permit holder from hindering or obstructing another person. In each case, the prohibition is only applicable where the permit holder is “exercising … rights in accordance with [Pt 3-4]” and additionally, but only in relation to s 500, “seeking to exercise … rights in accordance with [Pt 3-4]”.

[48] On the plain meaning of the provisions, it is only where the right conferred by Pt 3-4 is exercised, that the exercise of that right receives the protection of s 502 and only where the right conferred by Pt 3-4 is, or is sought to be, exercised that that exercise is regulated by and exposed to the sanction of s 500.

The same observations may be made in respect to the right conferred by s 481.

32 The importance of the rights conferred by provisions such as ss 481 and 482 (and their predecessor provisions) and the fundamental role served by such provisions in ensuring compliance with legislative objectives in the industrial law context, has attracted not only the attention of the Courts but also of commentators: e.g., Ford WJ, “Being There: Changing Union Rights of Entry under Federal Industrial Law” (2000) 13 AJLL 1.

Section 481 – the right conferred & purpose

33 Section 481 confers the right on a permit holder to enter premises and specifies the purpose for which that right may be exercised in the following terms (excluding notes):

Entry to investigate suspected contravention

(1) A permit holder may enter premises and exercise a right under section 482 or 483 for the purpose of investigating a suspected contravention of this Act, or a term of a fair work instrument, that relates to, or affects, a member of the permit holder’s organisation:

(a) whose industrial interests the organisation is entitled to represent; and

(b) who performs work on the premises.

(2) The fair work instrument must apply or have applied to the member.

(3) The permit holder must reasonably suspect that the contravention has occurred, or is occurring. The burden of proving that the suspicion is reasonable lies on the person asserting that fact.

There has to date been little judicial consideration by this Court of s 481.

34 The “purpose” to which s 481(1) refers is a purpose objectively determined rather than subjectively determined: cf. Curran v Thomas Borthwicks & Sons Ltd (1990) 26 FCR 241 at 252 to 253. There in issue was s 286(1) of the former Industrial Relations Act 1988 (Cth), which authorised (inter alia) entry upon premises “for the purpose of ensuring the observance of an award or an order of the Commission”. With reference to that provision, Gray J concluded:

Some discussion took place in argument as to whether the purpose referred to in s 286(1) is an objective or a subjective purpose. Mr Heerey QC, who appeared with Mr Kelly of counsel for the prosecutor, referred to cases in which the word “purpose” has been construed as meaning a subjective purpose. See Tillmanns Butcheries Pty Ltd v Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union (1979) 42 FLR 331 at 348-349; and Parker Pen (Aust) Pty Ltd v Export Development Grants Board (1983) 67 FLR 234 at 242. The question is a difficult one. It is plain from the authorities cited, and from Peate v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1964) 111 CLR 443 at 469, in the judgment of Kitto J, that the word “purpose” may mean either a subjective or an objective purpose, depending upon the context in which it is used. In the context of s 286(1) of the Act, it seems to me to be more likely that the purpose required is objective, that is that a particular exercise of a right to enter, inspect or interview can be said to be related with sufficient proximity to the object of ensuring observance of an award. If that were not the case, an honestly held but wholly mistaken belief by an officer of an organisation that he or she was pursuing a course which would result in the observance of an award would be decisive of the right to enter, inspect or interview. It is unlikely that Parliament intended the section to be construed in that manner. Its ultimate purpose is to promote the observance of awards, the giving of rights of entry, inspection and interview being only a means to that end.

This view was repeated as follows by his Honour in Australian Federation of Air Pilots v Australian Airlines Ltd (1991) 28 FCR 360 at 372:

In Curran’s case … the question was discussed whether the purpose is a subjective or an objective one; that is, whether it must be shown that the particular authorised officer intended to ensure the observance of the relevant award or order, or whether the right sought to be exercised had a sufficient connection with ensuring the observance of that award or order. It was held that the purpose required is objective.

In the present case, counsel for the defendant sought to challenge the correctness of this view. They argued that an improper or ulterior purpose of the authorised officer concerned would negate the rights of entry, inspection and interview. It is unnecessary to hold that a subjective purpose is required in order to accommodate this argument. For the reasons which I gave in Curran’s case, I am of the view that the purpose contemplated by the section is an objective one. To hold that a subjective purpose is required would be to render it difficult, if not impossible in some cases, for an occupier of premises to know whether an authorised officer was entitled to enter, inspect and interview. If the purpose required is objective, at least the occupier is able to make a rational assessment as to whether the right asserted could, if exercised, lead towards ensuring the observance of a relevant award or order.

There is no reason to take a different view of the meaning of the word “purpose” in s 481(1) of the Fair Work Act.

35 The requirement in s 481(3) of the Fair Work Act that a permit holder “reasonably suspect that the contravention has occurred, or is occurring” requires (at the very least) that there be facts known to the permit holder sufficient to induce a state of suspicion in a reasonable person. The reason for qualification is that s 481(3) and the requirement that a permit holder “reasonably suspects that [a] contravention has occurred”, may permit an inquiry into those facts which the permit holder exercising the right may not be personally aware of but are nevertheless readily available for consideration upon the making of reasonable inquiries. It could well be regarded as not promoting the balance sought to be struck by the Legislature in conferring the rights set forth in Pt 3-4 of the Fair Work Act for a permit holder to confine (either deliberately or inadvertently) the ambit of the factual basis upon which he seeks to exercise such a right. The more limited the presently known facts, the more objectively reasonable a suspicion may be; the more expansive the readily available factual basis may be, the greater the difficulty there may be in demonstrating that any suspicion is “reasonably” held.

36 On any view, however, a totally unsubstantiated state of suspicion in the mind of a permit holder – albeit a state of suspicion which may otherwise be genuinely held – is not sufficient. But a suspicion founded upon an erroneous factual foundation may not mean that it is one which is not “reasonably” held. Left to one side are those circumstances, again, in which a permit holder (either deliberately or inadvertently) may (for example) refrain from making reasonable enquiries to check the correctness of the factual basis of his suspicion lest it deprive him of the right he seeks to exercise.

37 Guidance as to what is meant by a statutory requirement that there be “reasonable grounds” for a person’s belief may be gleaned from the following observations of Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ in George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 at 112:

When a statute prescribes that there must be “reasonable grounds” for a state of mind — including suspicion and belief — it requires the existence of facts which are sufficient to induce that state of mind in a reasonable person.

A little later (at 116) their Honours further observed:

The objective circumstances sufficient to show a reason to believe something need to point more clearly to the subject matter of the belief, but that is not to say that the objective circumstances must establish on the balance of probabilities that the subject matter in fact occurred or exists: the assent of belief is given on more slender evidence than proof. Belief is an inclination of the mind towards assenting to, rather than rejecting, a proposition and the grounds which can reasonably induce that inclination of the mind may, depending on the circumstances, leave something to surmise or conjecture.

These observations may also be applied to provisions such as s 481 of the Fair Work Act: cf. Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v John Holland Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 90 at [127], (2010) 186 FCR 88 at 124 per Logan J.

38 Relevant to an assessment as to whether “reasonable” grounds exist is the attitude of the occupier and any objections raised by the occupier: John Holland Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2009] FCA 786, (2009) 186 IR 408 at 461 to 462 per Greenwood J. In the context of s 768 of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth), Justice Greenwood thus reasoned as follows (at 461 to 462):

[170] Whether a person has reasonable grounds to believe that entry is not authorised involves an objective assessment of whether facts were before that person sufficient to induce a reasonable person to believe that grounds existed for denying authority to enter. That view is consistent with the approach to the notion of “reasonable grounds” in George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 and Rema Industries & Services Pty Ltd v Coad (1992) 107 ALR 374. In determining whether reasonable grounds for a belief exist, there is a relationship between the objective facts that must engender such a belief and the role, standards and duties of the person confronting the relevant facts. In this case, the officials are permit holders under the Act and Mr Dettmer is an experienced State Secretary of the AMWU. In the face of an employer’s objection to entry in the manner of 19 November 2008 and correspondence from the employer pressing that objection, a permit holder and the Unions as organisations, must necessarily give consideration to the merits of the employer’s claims and form a view as to whether the claims are well placed or not. If the Unions and the permit holders are satisfied that the claims are misplaced, the demonstrated consideration of the claims is very likely to suggest that the relevant person when seeking to enter the site had reasonable grounds for believing that entry was authorised even though events may subsequently demonstrate that entry was not authorised. Persons in the position of permit holders or officers of Unions cannot be said to have acted reasonably in the absence of reasonable investigation and enquiry into objections made and strongly pressed denying the very right of entry relied upon by those seeking entry. That follows because statutory rights of entry to premises carry with the exercise of those rights corresponding duties of enquiry to be reasonably satisfied that entry is authorised in the context of the facts and circumstances before the entry seeker. That corresponding duty is not only a function of a balance between rights and obligations but derives from Pt 15 of the Act, the objects recited in s 736 of the Act and the regime established for granting permits to enter.

Although an appeal from this decision was allowed by the Full Court (Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v John Holland Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 90, (2010) 186 FCR 88), these observations of the primary Judge continue to be apposite to s 481(3) of the Fair Work Act. Thus, a permit holder must consider any objections raised by an occupier before seeking to exercise the statutory right of entry under s 481 of the Fair Work Act.

39 Although the exercise of the right depends upon an objective assessment as to the reasonableness of the suspicion on the part of a permit holder – and not the reasonableness of any belief on the part of an occupier – it could equally be suggested that an occupier should reconsider its position of opposition in light of any response provided by the permit holder to the occupier’s objections. An assessment as to the reasonableness of the suspicion held by the permit holder may well be assisted by reference to the bases upon which the permit holder and occupier are advancing their competing positions.

Section 482 – the rights that may be exercised

40 Section 482 of the Fair Work Act sets forth as follows the rights that may be exercised by a permit holder whilst on premises (notes omitted):

Rights that may be exercised while on premises

Rights that may be exercised while on premises

(1) While on the premises, the permit holder may do the following:

(a) inspect any work, process or object relevant to the suspected contravention;

(b) interview any person about the suspected contravention:

(i) who agrees to be interviewed; and

(ii) whose industrial interests the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent;

(c) require the occupier or an affected employer to allow the permit holder to inspect, and make copies of, any record or document (other than a non-member record or document) that is directly relevant to the suspected contravention and that:

(i) is kept on the premises; or

(ii) is accessible from a computer that is kept on the premises.

(1A) However, an occupier or affected employer is not required under paragraph (1)(c) to allow the permit holder to inspect, or make copies of, a record or document if to do so would contravene a law of the Commonwealth or a law of a State or Territory.

Meaning of affected employer

(2) A person is an affected employer, in relation to an entry onto premises under this Subdivision, if:

(a) the person employs a member of the permit holder’s organisation whose industrial interests the organisation is entitled to represent; and

(b) the member performs work on the premises; and

(c) the suspected contravention relates to, or affects, the member.

Meaning of non-member record or document

(2A) A non-member record or document is a record or document that:

(a) relates to the employment of a person who is not a member of the permit holder’s organisation; and

(b) does not also substantially relate to the employment of a person who is a member of the permit holder’s organisation;

but does not include a record or document that relates only to a person or persons who are not members of the permit holder’s organisation if the person or persons have consented in writing to the record or document being inspected or copied by the permit holder.

Occupier and affected employer must not contravene requirement

(3) An occupier or affected employer must not contravene a requirement under paragraph (1)(c).

The right conferred by s 482(1)(c), it may be noted at the outset, to require an occupier to allow a permit holder “to inspect, and make copies of, any record or document (other than a non-member record or document) that is directly relevant to the suspected contravention” is a right constrained by its terms to a right to inspect and make copies of any record or document that is “directly relevant” to the suspected contravention.

41 Section 486, which appears in Subdiv C of Div 2 of Pt 3-4, it should also be noted provides as follows:

Permit holder must not contravene this Subdivision

Subdivisions A, AA and B do not authorise a permit holder to enter or remain on premises, or exercise any other right, if he or she contravenes this Subdivision, or regulations prescribed under section 521, in exercising that right.

42 Section 502, it should also be noted, provides as follows (note omitted):

Person must not hinder or obstruct permit holder

(1) A person must not intentionally hinder or obstruct a permit holder exercising rights in accordance with this Part.

(2) To avoid doubt, a failure to agree on a place as referred to in paragraph 483(5)(b), 483C(6)(b) or 483E(6)(b) does not constitute hindering or obstructing a permit holder.

(3) Without limiting subsection (1), that subsection extends to hindering or obstructing that occurs after an entry notice is given but before a permit holder enters premises.

The requirements to be satisfied – the need for an entry notice

43 Within Subdiv C, s 487 generally requires the giving of an “entry notice for the entry” to the occupier whose premises are sought to be entered. That section provides in part as follows:

Giving entry notice or exemption certificate

Entry under Subdivision A or B

(1) Unless the FWC has issued an exemption certificate for the entry, the permit holder must:

(a) before entering premises under Subdivision A—give the occupier of the premises and any affected employer an entry notice for the entry; and

(b) before entering premises under Subdivision B—give the occupier of the premises an entry notice for the entry.

(2) An entry notice for an entry is a notice that complies with section 518.

(3) An entry notice for an entry under Subdivision A or B must be given during working hours at least 24 hours, but not more than 14 days, before the entry.

An entry under s 481 is an entry under Subdiv A.

44 In Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v McDermott [2016] FCA 1147, Charlesworth J said:

[18] The combined effect of ss 484, 486 and 487 of the FW Act is that a permit holder who has not complied with the requirements of s 487 is not authorised to enter or remain on premises under s 484 of the FW Act …

Relying upon her Honour’s observations, and with specific reference to s 487, Bromberg J stated in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCA 802, (2017) 252 FCR 198 at 214 that:

[68] … where the lawful exercise of a right of entry to enter particular premises on a particular day is predicated on the giving of prior notice of the particular entry, the giving of that notice may sensibly be regarded as a precondition of the conferral of the right of entry.

45 Section 518 sets forth what are referred to as “[e]ntry notice requirements”. That section provides in relevant part as follows:

Requirements for all entry notices

(1) An entry notice must specify the following:

(a) the premises that are proposed to be entered;

(b) the day of the entry;

(c) the organisation of which the permit holder for the entry is an official.

Requirements for entry notice for entry to investigate suspected contravention

(2) An entry notice given for an entry under section 481, 483A or 483D must:

(a) specify that section as the provision that authorises the entry; and

(b) unless the entry is a designated outworker terms entry under section 483A—specify the particulars of the suspected contravention, or contraventions; and

(c) for an entry under section 481—contain a declaration by the permit holder for the entry that the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent the industrial interests of a member, who performs work on the premises, and:

(i) to whom the suspected contravention or contraventions relate; or

(ii) who is affected by the suspected contravention or contraventions; and

…

(d) specify the provision of the organisation’s rules that entitles the organisation to represent the member or TCF award worker.

Section 518(3) addresses as follows the content required of an entry notice where entry is sought pursuant to s 484:

Requirements for entry notice for entry to hold discussions

(3) An entry notice given for an entry under section 484 (which deals with entry to hold discussions) must:

(a) specify that section as the provision that authorises the entry; and

(b) contain a declaration by the permit holder for the entry that the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent the industrial interests of an employee or TCF award worker who performs work on the premises; and

(c) specify the provision of the organisation’s rules that entitles the organisation to represent the employee or TCF award worker.

That sub-section, it will be noted, imposes much the same requirements as s 518(2)(a), (c) and (d).

46 Section 521(a) of the Fair Work Act provides that the regulations may provide for the form of entry notices. Regulation 3.27 of the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) provides that the “form of an entry notice is set out in Form 2 in Schedule 3.3” of the Regulations. An entry notice gives an occupier or employer “some forewarning of the proposed entry and of its purpose”: Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2016] FCA 413 at [44] per White J. “The required content of an entry notice varies according to the purpose for which the permit holder wishes to enter the premises”: Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Stephenson [2014] FCA 1432 at [2], (2014) 146 ALD 75 at 76 per White J.

47 When addressing the terms of s 518 in Regional Express Holdings Ltd v Australian Federation of Air Pilots [2016] FCAFC 147, (2016) 244 FCR 344 at 362, Jessup J (North and White JJ agreeing) emphasised the importance of compliance with the mandatory requirements imposed by the term “must” as follows:

[53] … Under s 518, the notice of entry which the permit holder is required to give must contain a declaration by him or her that his or her organisation is entitled to represent the industrial interests of a member to whom the suspected contravention relates, or who is affected by the suspected contravention, and must “specify the provision of the organisation’s rules that entitles the organisation to represent the member”. By s 484, a permit holder may enter premises for the purposes of holding discussions with employees who perform work on the premises, “whose industrial interests the permit holder’s organisation is entitled to represent” and who wish to participate in those discussions. Here the relevant notice of entry must contain a declaration by the permit holder that his or her organisation is entitled to represent the industrial interests of an employee who performs work on the premises, and must specify the provision of the organisation’s rules that entitles the organisation to represent the employee: s 518(3).

THE FACTS & THE SUSPECTED CONTRAVENTIONS

48 Although Qantas accepts that the facts are “not particularly controversial”, it has identified a cascading series of separate reasons as to why it says the Association is not entitled to relief.

49 In very summary form, it has been concluded that:

the Entry Notice provided to Qantas on 3 June 2016 did comply with s 518(2)(b) of the Fair Work Act in that it did “specify the particulars of the suspected … contraventions” of cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement but did not comply with s 518(2)(b) in respect to the suspected contraventions of cl 47 of the Enterprise Agreement.

Mr Purvinas did in fact hold a suspicion as to contraventions of both cll 47 and 60 of the Enterprise Agreement but the requirement imposed by s 481(3) of the Fair Work Act that that suspicion be reasonable was only satisfied with respect to the suspected contravention of cl 60 – the suspicion held with respect to the suspected contravention of cl 47 was one which could not reasonably be held;

the Entry Notice provided to Qantas on 3 June 2016 did comply with s 518(2)(c) of the Fair Work Act in that it did contain a declaration that the permit holder’s organisation was “entitled to represent the industrial interests of a member, who performs work on the premises”;

the Association has failed to establish that any of the documents to which access was sought were “directly relevant” to a suspected contravention of cl 47 of the Enterprise Agreement and has only established that some of the documents sought were “directly relevant” to a suspected contravention of cl 60; and

when Mr Purvinas entered the Qantas premises on 7 and 8 June 2016 and but for the consent of Qantas, it may well be that he could not have lawfully exercised his “right” to enter those premises pursuant to s 481 but, irrespective of whether he had any such “right”, he had no “right” conferred by s 482(1)(c) to require Qantas to allow him to inspect the documents he sought.

It is the absence of any “right” conferred by s 482(1)(c), however, more so than any non-compliance with s 518(2)(b), which assumes importance.

50 Each of these conclusions should be more fully addressed.

A suspected contravention – the need for particulars

51 The right of entry conferred by s 481 and the exercise of the rights conferred by s 482 are relevantly conditioned upon the permit holder having a reasonable suspicion that there has occurred or is occurring “a suspected contravention of [the Fair Work Act], or a term of a fair work instrument”.

52 Section 481 does not require as a condition precedent to the exercise of the statutory right of entry for a contravention to have in fact occurred; it is sufficient if a permit holder “reasonably suspect[s]” that a contravention has occurred or is occurring. Section 481(1) refers to “the purpose of investigating a suspected contravention of this Act”. The exercise of the statutory right of entry is thus not made unlawful should it later be established that there has in fact been no contravention.

53 The fundamental importance of both the permit holder having a reasonable suspicion and the need for that suspicion to be held in respect to a particular “contravention” as being dual preconditions for the exercise of the right of entry is not only self-evident from the terms of s 481 itself, but is also further reinforced by the requirement in s 518(2)(b) to “specify the particulars of the suspected contravention” in the Entry Notice.

54 There is a degree of precision required by s 518(2)(b). So much is made explicit by both the term “specify” and the identification of that which is to be specified, namely “particulars” of the suspected contravention.

55 It will not be sufficient if an Entry Notice merely states that there is or has been a “suspected contravention” or even that there is or has been a “suspected contravention” of (for example) a particular clause of an enterprise agreement. A permit holder seeking to exercise a right of entry needs to provide further details to an occupier. Section 518(2)(b), it is considered, does not require a permit holder to:

“specify the particulars” as to the basis upon which the permit holder “reasonably suspect[s]” a contravention to have occurred,

but s 518(2)(b) does require a permit holder to:

“specify the particulars”, namely set forth the facts, matters and circumstances said to give rise to “the suspected contravention, or contraventions”.

Such a requirement not only imposes a discipline upon the permit holder seeking to exercise the statutory right such that the permit holder is required to focus attention upon those “particulars” which go to the “suspected contravention”; such a requirement also enables an occupier or employer whose common law rights are being displaced by the statutory right of entry to make an informed decision as to whether the statutory right is being lawfully exercised or whether the permit holder is acting in excess of the right conferred.

56 Notwithstanding the central importance of the need to identify the suspected contravention with the requisite degree of specificity, there was considerable uncertainty throughout the hearing as to the suspected contraventions which triggered the exercise of the right on 7 and 8 June 2016.

57 Whatever flexibility there may be as to the manner in which the suspected contravention is identified – and perhaps even flexibility as to whether the suspected contravention could be reformulated even after the right of entry has been exercised – it is the terms of the Entry Notice which assume central importance. The Entry Notice in the present case identified suspected contraventions of:

clause 47; and

clause 60

of the Enterprise Agreement.

58 On the facts of the present case, there was a disturbing lack of precision in the Entry Notice in the way in which the “particulars” required by s 518(2)(b) were expressed. Section 518(2)(b) need not be construed as necessarily insisting upon the same degree of precision as may be required of particulars in a pleading filed in a superior court of record. The draftsman of an Entry Notice need not have at his side a copy of Bullen & Leake & Jacob’s Precedents of Pleadings. Although the standard required of particulars in a pleading in a superior court may provide some assistance in construing s 518(2)(b), that provision is to be construed and applied in the industrial context in which rights of entry are conferred by the Fair Work Act. While there should be no insistence that the “particulars” required by s 518(2)(b) be drafted with the precision of an experienced legal practitioner drafting a pleading, the standard of particularisation required by s 518(2)(b) should not be construed with such flexibility as to provide an occupier with little (or no) idea as to whether the right sought to be exercised is a lawful exercise of statutory power.

59 So construed, it is concluded that the Entry Notice dated 3 June 2016:

properly identifies the suspected contravention in respect to cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement, that contravention being the statement of suspicion that “Qantas are exercising clause 60 to order directed leave over and above the level they are entitled to”.

Greater reservation is expressed in reaching a conclusion that “particulars” have been provided as required by s 518(2)(b) in respect to:

the suspected contravention of cl 47 of the Enterprise Agreement.

That reservation arises from the fact that the Entry Notice expresses the suspicion that “Qantas has not complied with consultation requirements in clause 47”. Presumably, there was no suspected contravention of cl 47.1 of the Enterprise Agreement; the suspected contravention is one directed to cl 47.2. Clause 47.2.1 requires consultation with respect to “inter alia, the introduction of the changes referred to in clause 47.1”, namely the introduction of “major changes”. But nowhere in the Entry Notice are those “major changes” expressly identified. That potential deficiency, however, may presently be left to one side. It may presently be accepted that the “major changes” intended to be referred to are what is identified in the Entry Notice as:

“organisational changes”;

And those “organisational changes”, it may further be presently accepted, is a reference back to:

the fact that Qantas has “added new work” and the fact that some employees who formed the basis of an earlier surplus calculation are “now working in different departments or undertaking other functions not considered in the surplus calculation”.

60 The two fundamental deficiencies in the Entry Notice and the specification of the “particulars” in respect to the suspected contravention of cl 47.2 are nevertheless to be found in the fact that:

there is no specification as to whether the suspected contravention is a failure to consult in respect to “the introduction of the changes” or “the effects the changes are likely to have on employees” or “measures to avert or mitigate the adverse effects” etc, being the non-exhaustive list of things specified in cl 47.2.1 with respect to which Qantas is required to consult; and

there is no specification as to those facts, matters and circumstances relied upon to found the suspicion as to the absence of consultation, whatever may have been the more generally expressed topic with respect to which it was said that Qantas should have consulted. There is no specification (for example) as to whether the suspected contravention is founded upon a failure to disclose information necessary for there to be meaningful consultation or founded upon a failure to “give prompt consideration to matters raised by the employees and/or their union” (cl 47.2.1).

61 With respect to the suspected contravention of cl 47.2 of the Enterprise Agreement, the Entry Notice, it is respectfully concluded, fails to “specify the particulars of the suspected contravention”. The Entry Notice, in substance, merely identifies the clause of the Enterprise Agreement which the permit holder suspects has been contravened; it does not set forth any basis upon which any such suspicion could be formed. The assertion as to a suspected contravention provides the occupier with no notice as to what should have happened or what has not happened which would give rise to the asserted suspicion as to the failure to consult.

62 It is thus concluded that the Entry Notice:

does “specify the particulars” as required by s 518(2)(b) of the Fair Work Act in respect to the suspected contraventions of cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement; but

fails to “specify the particulars” in respect to the suspected contravention of cl 47 of the Enterprise Agreement.

63 Given the conclusion that s 481(3) has not been satisfied (at least in respect to the suspected contravention of cl 47), namely the requirement that a permit holder must “reasonably suspect that the contravention has occurred, or is occurring”, it is unnecessary to consider whether the rights conferred by ss 481 and/or 482 could not lawfully be exercised in the event that there had been non-compliance with s 518(2)(b).

A suspected contravention – the need for a reasonable suspicion?

64 A further argument advanced on behalf of Qantas focussed upon the requirement imposed by s 481(3) as to the need for a permit holder to “reasonably suspect that the contravention has occurred, or is occurring”. This argument had two limbs to it, namely:

the need for the permit holder, in this case Mr Purvinas, to have in fact held such a suspicion;

and, if Mr Purvinas did in fact hold such a suspicion:

whether the facts were such that a reasonable person could form a suspicion as to there being a contravention or contraventions.

Section 481(3) of the Fair Work Act, Qantas maintains in its written submissions, “makes it clear that the burden of proving (a) that the suspicion was held (subjective) and (b) that the holding of it was reasonable (objective), lies on the person asserting the fact, being the applicant here”.

65 Each limb to this argument needs to be separately considered.

The subjective suspicion held by Mr Purvinas

66 Mr Purvinas in his affidavit sets forth considerable detail of the exchanges between himself and Qantas going to the assessment made by Qantas as to there being a “surplus” of 46.5 licenced aircraft maintenance engineers in Sydney and the pursuit by Qantas of its “leave burn” program. That detail includes correspondence and an account of meetings held.

67 One thing which clearly emerges from those exchanges is the position being consistently advanced on behalf of Qantas that any assessment as to whether there was a “surplus” of licenced aircraft maintenance engineers over the number required was a matter for Qantas to determine by reference to its “operational requirements”. One letter sent to Mr Purvinas by Qantas dated 8 April 2016 thus stated in relevant part as follows:

I refer to your letter of 1 April 2016.

Qantas does not agree with a number of the assertions contained in your letter.

Specifically, it is the position of Qantas that:

1. whether there is a surplus in the number of Licensed Aircraft Maintenance Engineers (LAMEs) covered by the LAME EA 10, is a matter to be determined by Qantas by reference to Qantas’s operational requirements;

2. there is presently a surplus in the number of LAMEs covered by EA 10 (that is, Qantas currently employs more LAMEs than it requires);

3. regardless of whether it is required to do so under the terms of EA 10, Qantas has consulted with the ALAEA on numerous occasions over the course of 2014, 2015, and 2016 in relation to surpluses, changes in operational requirements, and leave burn;

4. it is now entitled to direct LAMEs to take period(s) of leave; and

5. LAMEs who are directed by Qantas to take period(s) of leave are not required to remain on standby for the duration of the directed leave.

68 Whatever the merits of the competing positions being adopted, Mr Purvinas was steadfast in his belief that there was a potential contravention of cll 47 and 60 of the Enterprise Agreement. He expressed this belief at various parts of his affidavit and at various points of time. Paragraph [55] of his affidavit thus stated as follows:

By the start of June 2016, I felt that there was no way to resolve my concerns that Qantas was breaching the Agreement other than to exercise the powers that I hold as a right of entry permit holder under the Fair Work Act. This would allow me to enter the premises, interview members and copy documents that were relevant to my suspicion that Qantas was contravening clauses 47 and 60 of the Agreement.

Mr Purvinas then sets forth the process he then undertook to “review some information I had available from members, to check if I was well founded in my suspicions that Qantas were breaching the Agreement by forcing members on leave as part of a leave burn program” (at para [56]). After having undertaken that “review”, Mr Purvinas concluded as follows:

75. After this exercise, it was my view that Qantas had made employees redundant and implemented a leave burn program that actually reduced their staffing levels to below those required by the contracts between Qantas Engineering and Qantas Airlines, and as required by CASA. On that basis, and having regard to my discussions with Qantas throughout 2016, I formed the view that its assertion that there were 46.5 surplus LAMEs was inaccurate.

76. At this point, I decided I had sufficient evidence to at least be able to demonstrate that I had a reasonable suspicion that Qantas was in breach of clauses 60 and 47 of the Agreement.

69 But this evidence, it was submitted on behalf of Qantas, should be rejected.

70 The “unreasonableness” of the stated suspicion, the Respondents submitted, should lead to a finding that Mr Purvinas did not in fact hold his stated suspicion. The evidence relied upon to support the submission as to “unreasonableness” and the matters relied upon as leading to the finding sought were the following:

the fact that Mr Purvinas did not support “leave burn”;

the fact that there was what was characterised by the Respondents as an “obvious incentive” for Mr Purvinas to make “leave burn” as difficult for Qantas to administer as possible; and

an asserted objective on the part of Mr Purvinas of seeking a negotiation as to the “surplus” figure of 46.5 employees.

71 The factual anchor for the submission was the acknowledgement on the part of Mr Purvinas that he did not support “leave burn”. So much is apparent from the following exchange during his cross-examination:

And employees accruing lots of annual leave and long service leave is seen favourably by LAMEs because it provides a good retirement payout?—Some see it that way and some don’t.

Yes. And some LAMEs like to keep those holidays and use them at a time of their choosing?—Some guys like to take their holidays, some guys like to store them.

Okay. And as a general preference, is it your position that you prefer not to see your members have their leave directed upon them?—I don’t know if I can answer that question, really. I haven’t really – I would have to think about it.

You don’t have a view?—Well, if you ask me again maybe in a different way I might be able to give you a more succinct answer.

Is it your preference that your members don’t have annual leave as a general rule, or long service leave, forced upon them by direction?—I would prefer members not be told when to take their leave.

72 The Respondents sought to support their assertion that Mr Purvinas had such a “preference” by reference to (inter alia):

what the Respondents characterised as attempts made by Mr Purvinas to negotiate a lower surplus figure; and

an asserted “inherent unreasonableness and illogicality associated with Mr Purvinas’ stated position”.

73 These submissions by the Respondents are rejected.

74 None of the matters identified by Qantas are necessarily inconsistent with the stated suspicion held by Mr Purvinas and certainly none (or all) of them provide any sufficient basis for rejecting the evidence of Mr Purvinas. Whether or not any contravention of cll 47 and 60 of the Enterprise Agreement are ultimately made out, the evidence of Mr Purvinas should be accepted as to his holding the relevant suspicion and his continuing to hold that suspicion after the review undertaken by him immediately prior to seeking to exercise his right of entry.

75 It is concluded that Mr Purvinas did in fact hold a suspicion that cll 47 and 60 of the Enterprise Agreement had been contravened.

76 The rejection of this first limb of the argument advanced by the Respondents nevertheless leaves open the second limb – namely, the submission that a subjectively held suspicion held by Mr Purvinas was not a suspicion which could reasonably be held.

Objective reasonableness

77 It is readily understandable why s 481(3) imposes a requirement that a permit holder who seeks to enter premises pursuant to the statutory right conferred by s 481 must not only in fact hold a suspicion that there has been a contravention – or that any such contravention is continuing – but the additional requirement that the permit holder “must reasonably suspect” that the contravention has occurred or is occurring. Section 481, it is to be recalled, is the conferral of a statutory right which gives rise to a significant and serious erosion of what would otherwise be the common law right of an occupier of premises to unilaterally decide who may enter those premises. The obvious legislative intent in requiring that a permit holder “must reasonably suspect” that a contravention has occurred or is occurring is a constraint upon the statutory right which ensure that the lawfulness of the exercise of the right is not left to the unilateral and subjective judgment of the permit holder.

78 When considering the objective reasonableness of the suspicion held by Mr Purvinas, again the suspicions he held in respect to a contravention of cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement should be considered separately from his suspicion in respect to a contravention of cl 47.

Objective reasonableness – cl 60 & the use of leave entitlements

79 Not only is it concluded that Mr Purvinas did in fact hold a suspicion as to a contravention of cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement, it is further concluded that that suspicion was one which could reasonable be held. The very facts relied upon by Mr Purvinas as forming the basis of his subjective suspicion, it is concluded, also support the objective reasonableness of that suspicion.

80 At the core of the suspicion held by Mr Purvinas was his belief that Qantas was erroneous in its assessment that there was a surplus of 46.5 licenced aircraft maintenance engineers in Sydney. In the absence of any such surplus, the path of reasoning was that cl 60 could not be properly invoked by Qantas in order to implement the “leave burn” program.

81 At the core of Qantas’ position were essentially two concerns, namely its submissions:

that its assessment as to any surplus was unchallengeable. If that be accepted, cl 60 was a means available to Qantas of addressing the surplus; and

that there was a lack of information available to Mr Purvinas upon which any reasonable suspicion could be founded.

Neither of these two concerns, it is respectfully concluded, defeats the objective reasonableness of the suspicion held by Mr Purvinas.

82 Although it may be accepted for present purposes that Qantas remains free to make commercial decisions as to the scope and extent of its operations, the rights and entitlements of its employees remain those protected by the Enterprise Agreement. Qantas may, for example, ultimately decide that it has a surplus of employees and further decide to make some employees redundant. In such circumstances, Qantas may make a “declaration” that the employees are redundant in accordance with cl 55.11.2 of the Enterprise Agreement and thereafter an employee may exercise the appeal right conferred by cl 55.13.12 of that Agreement.

83 In issue in the present proceeding, however, is not the extent to which Qantas retains an untrammelled commercial right to make such decisions as it sees fit or even, ultimately, its freedom to unilaterally direct employees to take leave. In different proceedings, where the factual context may well be different and where different issues are raised for resolution, the position now being advocated on behalf of Qantas may prove to be correct. About that, nothing is presently said.

84 What is also not in issue in the present proceeding is whether there has in fact been a contravention of cl 60 of the Enterprise Agreement.