FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2018] FCA 941

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA (ACN 123 123 124) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiff has leave to file in court an Originating Process in the form submitted to the chambers of Beach J on 31 May 2018 (Originating Process).

2. The Originating Process be heard instanter.

3. Declarations be made in the form of Annexure A to these orders (the declarations).

4. Pursuant to para 12GBA(1)(b) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) and in respect of the attempted contraventions the subject of paragraph 2 of the declarations, the defendant pay a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $5 million, to be paid to the Commonwealth of Australia within 14 days of this order.

5. The defendant pay the plaintiff’s costs of and incidental to these proceedings.

6. The proceedings otherwise be dismissed.

AND THE COURT OTHERWISE NOTES THAT:

7. The defendant has given to the plaintiff an enforceable undertaking which is material to the consideration of penalty, and which provides for the defendant to take certain steps and to pay $15 million into a fund that is to be applied to the benefit of the community.

8. The plaintiff proposes to issue to the defendant a direction under s 91 of the ASIC Act requiring the defendant to pay the plaintiff’s investigation costs.

9. The plaintiff and the defendant have agreed that the aggregate of:

(a) the costs of establishing the fund as referred to in paragraph 7 above;

(b) the plaintiff’s investigation costs referred to in paragraph 8 above; and

(c) the plaintiff’s costs of and incidental to these proceedings which are the subject of order 5 above,

is the sum of $5 million.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A – Declarations

1. In these declarations, the following definitions apply:

(a) CBA means Commonwealth Bank of Australia;

(b) ASIC Act means the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth);

(c) BAB means a Bill of Exchange, as defined in s 8 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1909 (Cth), which has been accepted by a bank and bears the name of the accepting bank as acceptor, and which obliges the bank to pay a specified sum to the holder of the bill on the date that it matures;

(d) BAB Futures means futures contracts traded on the ASX 24 futures exchange. Under the contract, one party agrees to buy and the other party agrees to sell a 3 month Prime Bank Bill at an agreed price on the expiry of the contract;

(e) Bank Bill Market means the market for trading of Prime Bank Bills through interdealer brokers;

(f) BBSW means the Bank Bill Swap Reference Rate which, in turn, means the trimmed, average mid-rate of the observed best bid/best offer for Prime Bank Bills for certain tenors on each Sydney business day published by the Australian Financial Markets Association Limited;

(g) Corporations Act means the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth);

(h) Counterparties means entities which, at the relevant time, were:

(i) counterparties to FRAs, interest rate swaps and BAB Futures to which CBA was also a party;

(ii) not “listed public companies” within the meaning of subs 12CB(5) of the ASIC Act; and

(iii) not participants in the Bank Bill Market;

(i) FRA means a Forward Rate Agreement where the parties agree to exchange interest rate payments on the settlement date based on the difference between an agreed contract rate and a settlement rate;

(j) Interest rate swap means an arrangement whereby two parties contractually agree to exchange interest rate cash flows by reference to a nominal underlying principal sum;

(k) NCD means a certificate issued by a bank evidencing an interest bearing deposit with the issuing bank for a fixed term, which entitles the holder of the certificate to payment of a specified sum by that bank on the date that the certificate matures;

(l) Prime Bank Bills means NCDs and BABs;

(m) Schedule A Dates means the dates referred to in Schedule A.

Attempted contraventions of s 12CB of the ASIC Act

2. The Court declares that:

(a) on each of the Schedule A Dates, by transacting or seeking to transact via brokers by way of sale or purchase of Prime Bank Bills on the Bank Bill Market, CBA attempted to affect where BBSW set in circumstances where:

(i) the BBSW was, and was known by CBA to be, a key benchmark and reference interest rate for the pricing and revaluation of Australian dollar loans, bills, derivatives, securities and other instruments, which was widely regarded by the market as independent, objective and transparent, and determined based upon prices for Prime Bank Bills formed by the competitive forces of supply and demand;

(ii) CBA knew that if the attempt to affect where BBSW set were successful:

(A) CBA’s BBSW rate set risk exposure would have been advantaged; and

(B) Counterparties who had a BBSW rate set risk exposure opposite to that of CBA may have been detrimentally affected;

(b) the conduct in (a) was conduct in trade or commerce and in connection with the acquisition or supply or possible acquisition or supply of financial services to a person (other than a listed company);

(c) by the conduct in (a), CBA attempted, within the meaning of para 12GBA(1)(b) of the ASIC Act, to engage in conduct which would be in all the circumstances unconscionable in contravention of subs 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act.

Contraventions of paras 912A(1)(a) and (f) of the Corporations Act

3. The Court declares that:

(a) by engaging in the conduct specified in paragraph 2 above, and

(b) by failing to have in place, on the Schedule A Dates, adequate policies and procedures requiring CBA staff to abstain from conduct of the nature referred to in paragraph 2(a), and

(c) by failing to have in place, on the Schedule A Dates:

(i) adequate policies and procedures for supervising and monitoring the conduct of CBA staff;

(ii) adequate supervision of the conduct of CBA staff; and

(iii) adequate monitoring of the conduct of CBA staff,

CBA failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its Australian Financial Services Licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly and, thereby, contravened para 912A(1)(a) on each of the Schedule A Dates.

4. The Court declares that by failing to adequately train CBA staff not to engage in the conduct referred to in paragraph 2(a), CBA failed to ensure that on the Schedule A Dates CBA staff were adequately trained to provide financial services and thereby contravened para 912A(1)(f).

Schedule A

(a) 3 February 2012

(b) 9 February 2012

(c) 15 March 2012

(d) 9 May 2012

(e) 15 June 2012

BEACH J:

1 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has brought these proceedings against the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) making various claims with respect to market manipulation and unconscionable conduct said to have been engaged in by the CBA concerning trading in Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market during the period 31 January 2012 to 5 June 2012 (the relevant period).

2 ASIC and CBA have now agreed to resolve the proceedings, subject to my determination of the appropriate penalty and approval of the declarations and other orders sought.

3 The parties have jointly submitted that I ought to make orders that include:

(a) first, declarations of the contraventions admitted by CBA, namely, that on each of the relevant contravention dates:

(i) CBA attempted to engage in conduct which if carried out as intended would have been unconscionable in contravention of s 12CB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth);

(ii) CBA failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its Australian Financial Services Licence were provided efficiently and fairly and thereby contravened para 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth); and

(iii) CBA failed to ensure that its traders were adequately trained to provide financial services and thereby contravened para 912A(1)(f) of the Corporations Act;

(b) second, the imposition of a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $5 million pursuant to para 12GBA(1)(b) of the ASIC Act in respect of five attempted contraventions of s 12CB of the ASIC Act;

(c) third, an order that CBA pay ASIC’s costs of and incidental to the proceedings; and

(d) fourth, an order that the proceedings otherwise be dismissed.

4 In support of their joint position the parties have provided me with proposed orders and a statement of agreed facts pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). I have set out the statement of agreed facts as a schedule to these reasons, excluding its annexures. For the most part, it is not necessary to repeat what is set out therein. I would also note that save for any CBA specific matters, the statement of agreed facts largely correlates with my own analysis of the operation of the Bank Bill Market, trading in Prime Bank Bills, the setting of BBSW and the terms and operation of relevant financial instruments that I have discussed in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) [2018] FCA 751 (ASIC v Westpac (No 2)).

5 Further, as part of the resolution of the proceedings, CBA has agreed to give an enforceable undertaking to ASIC pursuant to s 93AA of the ASIC Act. CBA will execute the enforceable undertaking following the making of my orders. The enforceable undertaking will provide for CBA to pay the sum of $15 million into a fund that is to be applied for the benefit of the community. I have taken that proposed undertaking into account in assessing the pecuniary penalty that is to be imposed.

6 Now whilst the quantum of any pecuniary penalty is ultimately a matter for me, the parties have submitted that an appropriate total amount for the pecuniary penalties under para 12GBA(1)(b) is $5 million. The parties also agree that the quantum of ASIC’s costs including its investigative costs which CBA should pay is $5 million.

7 In summary, I have determined that a pecuniary penalty fixed in the sum of $5 million is appropriate. That sum together with the other payments all totalling $25 million should be an adequate denouncement of and deterrence against the unacceptable trading behaviour of individuals within CBA that ought to have known better and a bank that ought to have better supervised its personnel.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

8 Now although I will not repeat what is set out in the statement of agreed facts it is appropriate to highlight some CBA specific aspects. Capitalised expressions used in these reasons are as defined in the statement of agreed facts unless I have defined them separately.

9 CBA is one of Australia’s largest companies. As at 30 June 2017, it had a market capitalisation of $143 billion, its net operating income exceeded $26.1 billion and its net profit after tax was $9.9 billion. At all material times, CBA has held an Australian Financial Services Licence.

10 During the relevant period, CBA was structured to include the following divisions:

(a) Group Treasury (Treasury); and

(b) Institutional Banking and Markets (Markets).

11 Treasury was responsible for managing CBA’s AUD liquidity and wholesale funding requirements. Treasury was structured into smaller business units, relevantly including Liquidity Operations (LOPS) and Portfolio Risk Management (also known as Asset & Portfolio Management or Asset & Liquidity Management) (ALM).

12 During the relevant period LOPS employees and officers based in Australia relevantly included: John Pilkington – Head of LOPS; Roman Groblicki – Dealer Specialist Short End Portfolio, LOPS; and Mark Hulme – Chief Dealer, LOPS.

13 It was the policy of CBA that responsibility for providing instructions to Brokers for the conduct of transactions in the Bank Bill Market during the BBSW Rate Set Window and determining CBA’s view of the mid-rate of the yield for Prime Bank Bills for submission to AFMA was centralised in a single position, the Bills Trader. During the relevant period, Mr Mark Hulme was the principal Bills Trader.

14 Markets serviced CBA’s major corporate, institutional and government clients. Markets derived revenue by trading in the name of CBA in financial products with counterparties, both through financial markets and otherwise, whilst managing CBA’s own risks arising from that trading and any holdings of financial products.

15 Within Markets was a desk known as the Swaps Desk or Swaps. During the relevant period, the employees of Swaps traded in and held books of financial products, including BBSW Referenced Products. Swaps traded in and held Prime Bank Bills, with a face value maximum holding limit of $1 billion. Swaps traded in the Bank Bill Market by providing instructions to the Bills Trader. During the relevant period the profitability of Swaps’ trading books was an important metric by which Swaps’ performance was measured at the close of each business day. The employees of Swaps were based in Australia and included, at all material times: Peter Psihoyos, who was the Head of Swaps, and Grant Barnes – Chief Dealer, Swaps.

16 Swaps entered into BBSW Referenced Products with counterparties including FRAs and interest rate swaps.

17 CBA was aware that its counterparties to BBSW Referenced Products comprised entities which did not participate in the Bank Bill Market and who were not listed public companies.

18 CBA supplied and acquired BBSW Referenced Products, including FRAs, interest rate swaps and loans which were referenced to BBSW. The entry into and the obtaining of rights and the assumption of obligations under FRAs and interest rate swaps involved the provision by Swaps of financial services covered by CBA’s Australian Financial Services Licence for the purposes of paras 912A(1)(a) and (f) of the Corporations Act. In entering into FRAs and interest rate swaps, and in obtaining rights and assuming obligations under them, in the relevant period, Swaps supplied or acquired a financial service to or from the counterparty to the FRA or the swap for the purposes of s 12CB of the ASIC Act.

19 On each Sydney business day during the relevant period the books managed by Treasury and Swaps held BBSW Referenced Products and consequently the earnings of those books were affected by the rate at which the BBSW for different tenors set. The principal value of the products so affected is referred to as the Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure and Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure.

20 During the relevant period, on a given Sydney business day the books managed by Swaps contained BBSW Referenced Products in relation to which:

(a) an obligation to pay an amount of money would be quantified when the relevant BBSW was set on that day;

(b) the amount payable by Swaps to the counterparty or the amount payable by the counterparty to Swaps depended upon the rate at which the relevant BBSW was set on that day; and

(c) the profit and loss of the books managed by Swaps was affected by movement in BBSW on that day.

21 In the relevant period, Swaps employees and LOPS employees were from time to time aware of the BBSW Rate Set Exposure of each other’s desk through communications with employees of that desk.

22 The statement of agreed facts specifies conduct which occurred on five dates between 31 January 2012 and 15 June 2012. On each of these occasions, CBA engaged in conduct that amounted to an attempted contravention of subs 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act. Such occasions comprised one attempt on each of 3 February 2012, 9 February 2012, 15 March 2012, 9 May 2012 and 15 June 2012, and each in respect of 3 month Prime Bank Bills (the Contravention Dates).

23 On each of the Contravention Dates, by transacting or seeking to transact via brokers by way of sale or purchase of Prime Bank Bills on the Bank Bill Market, CBA attempted to affect where BBSW set on that day, that is to say acted with an intention to seek to achieve that result.

24 The facts set out in the statement of agreed facts establish the attempt and the necessary intentional component. First, the relevant communications between CBA employees on or around each of the Contravention Dates disclose an intention to seek to change or influence where BBSW set on each Contravention Date through transacting in the Bank Bill Market. Second, CBA traded or sought to trade in the Bank Bill Market on the Contravention Dates with an intention of that nature. The communications predominantly involved employees on CBA’s two desks: LOPS (within Treasury) and Swaps (within Markets). Moreover, on each of the Contravention Dates, CBA’s Bills Trader acted as its “single face to the market”, giving instructions to brokers in relation to CBA’s trading in the Bank Bill Market.

25 I am satisfied that CBA’s conduct on the Contravention Dates involved the taking of steps towards contravention of subs 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act.

26 First, the BBSW was known to be a highly significant benchmark and reference interest rate for the pricing and revaluation of Australian dollar loans, bills, derivatives, securities and other instruments, which benchmark was regarded by the market as independent, objective and transparent, and determined based upon prices for Prime Bank Bills formed by the competitive forces of supply and demand.

27 Second, CBA was a Prime Bank and a Bank Bill Market participant and accordingly enjoyed the ability and advantage to issue and trade Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market, which privileged position was unavailable to counterparties who were not Prime Banks and participants in the Bank Bill Market. It abused that privilege.

28 Third, as a member of AFMA, CBA agreed to abide by the AFMA Code of Ethics and was encouraged to use the AFMA Code of Ethics as the basis to develop and implement more detailed procedures to effect within CBA the objectives of the AFMA Code of Ethics. The AFMA Code of Ethics set out the minimum standards, principles and rules of behaviour applicable to AFMA members in the conduct of their businesses. The AFMA Code of Ethics required its members to conduct their trading activities in a fair and orderly manner, maintain the integrity of financial markets and not carry out trading that would interfere with normal supply and demand dynamics in the market for a financial product. The present case is yet another example of a disconformity between the theoretical purity of documented codes of ethics and how they are applied, if at all, in the harsh reality of the marketplace.

29 Fourth, on each of the Contravention Dates both Treasury and Swaps had a net BBSW rate set exposure that may have been advantaged if the attempt made had been successful.

30 Fifth, on each of the Contravention Dates there were counterparties to BBSW Referenced Products with CBA that were not listed public companies and were not Bank Bill Market participants who had an opposite total BBSW exposure to that of CBA, who may have been detrimentally affected if the attempt had been successful.

31 Finally, on this aspect of the matter I do not conclude and the parties have not agreed that CBA’s trading of Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market on any of the Contravention Dates changed where the BBSW set on those dates. But so not to find is not to deny the attempt that was made by CBA on each of the Contravention Dates.

32 Let me deal with another matter.

33 At all material times, CBA maintained a number of policies and procedures applying to the conduct of its officers and employees. But whilst these policies were directed towards compliance, they were not adequate to address CBA’s impugned conduct.

34 The attempted contraventions arose out of conduct of certain CBA staff including senior management who did not prevent or give instructions to prevent the conduct referred to in the statement of agreed facts. Nor did CBA ensure that there were in place structures, systems and procedures for the prevention of that conduct.

35 CBA did not actively monitor trading by Swaps and LOPS in Prime Bank Bills to ensure that they did not trade with a purpose of changing the rate at which BBSW set which, if successful, might have detrimentally affected certain counterparties of CBA.

36 Finally, in terms of the factual background, the statement of agreed facts has also set out a range of additional facts including the following matters.

37 First, if CBA’s conduct referred to in the statement of agreed facts had been successful in changing where BBSW set, counterparties with an opposite rate set exposure to Swaps may have paid more to CBA or received less from it (as the case may be).

38 Second, from mid-2012 ASIC undertook inquiries of BBSW Panellists including CBA in relation to their involvement in the BBSW rate set process, and subsequently conducted an investigation into conduct including trading by CBA.

39 Third, since the conduct and behaviour described in the statement of agreed facts, there has been a change to the mechanism by which BBSW is calculated. On 1 January 2017 the ASX became the BBSW rate administrator, and more recently it has introduced a new mechanism.

40 On 21 May 2018 a new waterfall methodology was introduced by the ASX for the calculation and publication of the BBSW in each relevant tenor on each business day. Let me summarise some of its elements.

41 A volume weighted average price (VWAP) calculation is now the primary method used to determine the BBSW rate for each tenor for each business day. The calculation is performed over all eligible primary and secondary market transactions in Prime Bank Bills (including NCDs) transacted within the rolling maturity pool, throughout the BBSW rate set window. There are various points to note. First, the VWAP calculation is based upon actual transactions and traded yields. It is not based upon estimates of the best bids/best offers. Second, the BBSW rate set window is the broader period of 8.30 am to 10.00 am. Third, all eligible trades transacted bilaterally or through inter-dealer brokers during the BBSW rate set window must be reported and provided to the Benchmark Administrator for inclusion in the calculation. Such reporting of eligible trades must occur by 10.15 am. Fourth, the VWAP calculation is then performed over all eligible transactions observed within the BBSW rate set window for each tenor to provide the BBSW for each relevant tenor. This is then published at 10.30 am.

42 But if a BBSW rate cannot be validly calculated under the VWAP method for a particular tenor, for example, because the thresholds for each of the minimum volume ($ millions), minimum number of transactions and minimum number of counterparties have not been met, then the national best bid and offer (NBBO) calculation method is to be used to calculate the BBSW for that tenor. Further, in the event that a BBSW rate cannot be validly calculated under the NBBO method for a particular tenor, then the fall-back calculation waterfall is to be used.

43 In essence, the new calculation method is based upon actual market transactions, actual traded prices, a greater number of transactions and a longer BBSW rate set window. If the BBSW was previously susceptible to manipulation, the recent changes have substantially now minimised that risk.

LEGISLATIVE REGIME

44 The statement of agreed facts provides an adequate foundation for establishing that by engaging in the conduct referred to in that statement, CBA attempted to engage in conduct, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or acquisition of financial services that was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable. By reason of that matter, on five occasions, CBA attempted to contravene subs 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act.

45 Paragraph 12GBA(1)(b) of the ASIC Act provides that a pecuniary penalty can be imposed for attempted contraventions of, inter-alia, s 12CB. Section 12GBA is in relevantly analogous terms to s 76 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), which was considered by Toohey J in Trade Practices Commission v Tubemakers of Australia Ltd (1983) 47 ALR 719; [1983] FCA 99. Whilst s 76 concerned penalties in respect of Pt IV of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), the fact that the words of s 76 and s 12GBA are relevantly identical means that I can appropriately draw upon his Honour’s analysis where he drew on the concept of attempt in the criminal law to identify the relevant principles applicable to attempts giving rise to civil pecuniary liability. Toohey J identified (at 736) the actus reus of an attempt as the doing of:

an act which is a step towards the commission of the specific [contravention], which is immediately and not merely remotely connected with the commission of it, and the doing of which cannot reasonably be regarded as having any other purpose than the commission of the specific [contravention].

46 It is also necessary to establish intent in the sense of a purpose to bring about that which is attempted. This applies to the step taken by Swaps and LOPS personnel on the identified Contravention Dates in making bids and offers on the Bank Bill Market and trading with the intention of influencing where BBSW would set so as to reduce the amount payable to, or increasing the amount payable by, Swaps’ counterparties.

47 The substantive provision in respect of which there are admissions of attempted contravention is subs 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act. I have analysed s 12CB and the predecessor version of s 12CC in ASIC v Westpac (No 2) at [2162] to [2181] and my discussion therein should be taken as being incorporated in these reasons.

48 ASIC and CBA also agree that CBA failed in its obligations under paras 912A(1)(a) and (f) of the Corporations Act. I have also analysed these provisions in ASIC v Westpac (No 2) at [2347] to [2351] and [2490] respectively and I incorporate that discussion in these reasons.

49 Let me now turn to two aspects of the relief or orders sought, namely:

(a) whether declaratory relief should be given; and

(b) whether a pecuniary penalty should be ordered, and if so its amount.

DECLARATORY RELIEF

50 I have a broad discretionary power to make declarations, inter-alia, under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), and in my view it is appropriate to make declarations in this case.

51 First, ASIC, as the Commonwealth agency responsible for enforcing the ASIC Act, has a real interest in seeking the proposed declarations.

52 Second, the declarations have been framed to reflect the factual foundation before me and the basis on which CBA’s conduct contravened the relevant statutory provisions.

53 Moreover, CBA has admitted that it made bids, offers and traded in the Bank Bill Market on the specified occasions in an attempt to affect the AFMA submission process through which the BBSW would be set on the Contravention Dates and so that the BBSW would set to its advantage. Now although I have not found that the bids and/or offers actually impacted where the BBSW set on any of those occasions, CBA’s admissions are sufficient to disclose each of the elements of an attempted contravention of s 12CB of the ASIC Act on each such occasion.

54 In respect of each of the Contravention Dates, I am satisfied that CBA’s conduct, if the intended outcome of each attempt had been successful, would have been unconscionable having regard to:

(a) the vulnerability of certain CBA counterparties to CBA’s conduct;

(b) CBA’s knowledge as to the status and function of BBSW as a central reference interest rate in Australian financial markets and for financial products supplied by CBA;

(c) Swaps’ intention to profit at the expense of its counterparties; and

(d) the potential that counterparties may have been detrimentally affected were CBA to have been successful in changing where BBSW set in a way that advantaged itself.

55 I am also satisfied that the conduct was in trade or commerce and in connection with the supply or acquisition of financial services being dealings in FRAs and interest rate swaps.

56 Third, there is substantial utility in making the declarations sought. They will identify conduct that constituted attempted contraventions of subs 12CB(1), mark my disapproval of those attempted contraventions, assist ASIC in carrying out its duties and deter other persons from engaging in attempted contraventions. Generally, the making of declarations will serve the public interest.

57 Finally on this aspect, I am satisfied that I should make declarations of contraventions of paras 912A(1)(a) and (f) of the Corporations Act. The factual substratum for such declarations is identified in the statement of agreed facts. The admitted conduct is contrary to the efficient and fair provision of financial services. CBA’s policies, procedures and systems were inadequate. The public was entitled to expect that CBA would take reasonable steps to comply with its statutory obligations. Its systems failed to ensure efficiency and fairness in the provision of financial services.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

58 In my view it is appropriate for a pecuniary penalty to be ordered against CBA in respect of the attempted contraventions of subs 12CB(1) identified in the statement of agreed facts. The penalty ought be in the total amount of $5 million. Let me elaborate on some relevant principles.

59 Relevantly to the present context, the power to order a pecuniary penalty arises under para 12GBA(1)(b) of the ASIC Act. In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, subs 12GBA(2) of the ASIC Act provides:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Subdivision to have engaged in any similar conduct.

60 The maximum pecuniary penalty payable under subs 12GBA(1) is, in respect of a provision of Subdivision C or D and if the person is a body corporate, 10,000 penalty units: subs 12GBA(3) item 2. At the time of the attempted contraventions that I am dealing with, a penalty unit was $110: Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), subs 4AA(1). Accordingly, the maximum penalty for each attempted contravention that I am concerned with is $1,100,000. Therefore, the maximum penalty for the five attempted contraventions is $5,500,000. Now I would note that the penalty unit rate has since increased, but the relevant and lower rate that I am required to apply is that which was in place at the time of the relevant conduct.

61 The principles relevant to the determination of pecuniary penalties are not in doubt. Let me make some brief observations.

62 Now criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation. But the purpose of a civil penalty is primarily protective in promoting the public interest in compliance, and to be achieved through both specific and general deterrence. A pecuniary penalty must put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene. Its level must be fixed to ensure that the penalty is not to be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business. As I have said, both specific and general deterrence are important. The need for specific deterrence is informed by the attitude of the contravener to the contraventions, both during the course of the contravening conduct and in the course of the proceedings. And the need for general deterrence is particularly important when imposing a penalty for a contravention which is difficult to detect.

63 The fixing of a pecuniary penalty involves the identification and balancing of all the factors relevant to the contravention and the circumstances of the defendant, and the making of a value judgement as to what is the appropriate penalty in light of the purposes and objects of a pecuniary penalty that I have just explained. Relevant factors usefully enumerated by the parties before me include the following:

(a) the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate or reckless conduct by the corporation, as opposed to negligence or carelessness;

(b) the number of contraventions, the length of the period over which the contraventions occurred, and whether the contraventions comprised isolated conduct or were systematic;

(c) the seniority of officers responsible for the contravention;

(d) the capacity of the defendant to pay, but only in the sense that whilst the size of a corporation does not of itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed, it may be relevant in determining the size of the pecuniary penalty that would operate as an effective specific deterrent;

(e) the existence within the corporation of compliance systems, including provisions for and evidence of education and internal enforcement of such systems;

(f) remedial and disciplinary steps taken after the contravention and directed to putting in place a compliance system or improving existing systems and disciplining officers responsible for the contravention;

(g) whether the directors of the corporation were aware of the relevant facts and, if not, what processes were in place at the time or put in place after the contravention to ensure their awareness of such facts in the future;

(h) any change in the composition of the board or senior managers since the contravention;

(i) the degree of the corporation’s cooperation with the regulator, including any admission of an actual or attempted contravention;

(j) the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties;

(k) the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention; and

(l) whether the corporation has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in the past.

64 Moreover, attention must be given to the maximum penalty for the contravention. Further, where contravening conduct is not so grave as to warrant the imposition of the maximum penalty, I am bound to consider where the facts of the particular conduct lie on the spectrum that extends from the least serious instances of the offence to the worst category.

65 Further, in cases involving an attempted contravention, the fact that the attempt did not proceed to an actual contravention, and therefore did not involve actual loss or damage, is one factor reducing its level of seriousness. That result also follows from para 12GBA(2)(a), which requires that regard be had to any loss or damage suffered as a result of the relevant act or omission. But it is relevant to determining the gravity or seriousness of an attempt to consider what might have been the result if the attempt had been successful.

66 Let me now say something about the course of conduct, totality and parity principles.

67 The course of conduct principle has been applied in the civil pecuniary penalty context. I repeat what I said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [21] to [25] to the following effect:

In determining the appropriate penalty for multiple contraventions, there are two related principles to consider: the “totality” principle and the “course of conduct” principle.

As I have explained, the totality principle requires that the total penalty for related offences not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved taking into account all factors. The principle operates to ensure that the penalties to be imposed, considered as a whole, are just and appropriate.

Contrastingly, the “course of conduct” principle gives consideration to whether the contraventions arise out of the same course of conduct to determine whether it is appropriate that a single overall penalty should be imposed that is appropriate for the course of conduct. It has a narrower focus. The principle was explained in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 194 IR 461 at [39] per Middleton and Gordon JJ:

It is a concept which arises in the criminal context generally and one which may be relevant to the proper exercise of the sentencing discretion. The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factually specific inquiry. Bare identity of motive for commission of separate offences will seldom suffice to establish the same criminality in separate and distinct offending acts or omissions. (emphasis in original)

But even if the contraventions are properly characterised as arising from a single course of conduct, I am not obliged to apply the principle if the resulting penalty fails to reflect the seriousness of the contraventions. The principle does not restrict my discretion as to the amount of penalty to be imposed for the course of conduct. Further, the maximum penalty for the course of conduct is not restricted to the prescribed statutory maximum penalty for any single contravening act or omission (i.e. $1.1 million); the respondents’ submission to the contrary is rejected.

Further, the “course of conduct” principle does not have paramountcy in the process of assessing an appropriate penalty. It cannot of itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions of the ACL. Further, its application and utility must be tailored to the circumstances. In some cases, the contravening conduct may involve many acts of contravention that affect a very large number of consumers and a large monetary value of commerce, but the conduct might be characterised as involving a single course of conduct. Contrastingly, in other cases, there may be a small number of contraventions, affecting few consumers and having small commercial significance, but the conduct might be characterised as involving several separate courses of conduct. It might be anomalous to apply the concept to the former scenario, yet be precluded from applying it to the latter scenario. The “course of conduct” principle cannot unduly fetter the proper application of s 224.

68 My views on the totality principle are also adequately summarised in the above passage.

69 As for the parity principle, this requires that “persons or corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties” (Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited (2017) 123 ACSR 341; [2017] FCA 1338 at [96] per Jagot J).

70 Let me now apply these principles to the present case.

71 In my view and in the exercise of my powers under subs 12GBA(1), it is appropriate to order that CBA pay a total pecuniary penalty of $5 million for the five attempted contraventions.

72 The maximum total penalty available for all five contraventions is $5,500,000. Such a penalty is reserved for contraventions so grave as to warrant the maximum prescribed penalty. But the attempted contraventions here are serious and warrant the imposition of a penalty of $5 million.

73 The following matters demand that a penalty towards the upper end of the available range be imposed. First, CBA’s conduct was deliberate in the sense that it was engaged in with the intention of achieving an outcome proscribed by the ASIC Act, and was not transparent to counterparties. Second, there were multiple occasions over a period spanning approximately five months. Third, CBA’s conduct involved relatively senior staff. Fourth, the conduct was not prevented by CBA policies and systems or by its senior management. Fifth, none of the relevant employees or senior executives had been adequately trained about the implications of attempts to influence the BBSW for their compliance with CBA’s policies. Sixth, CBA’s conduct was engaged in for the purpose of profiting CBA in circumstances where CBA knew that if successful, it may have gained at the expense of others who were vulnerable. Seventh, it is necessary to ensure that to attempt to contravene the ASIC Act is not more profitable than paying a penalty. Eighth, CBA is one of Australia’s largest public listed companies. As at 30 June 2017 it had a market capitalisation of $143 billion and statutory net profit after tax of 30 June 2017 of $9.9 billion. Notwithstanding its size, any penalty should operate as some deterrent to CBA within the context of those resources. Ninth, the penalty provides parity with the penalties that ANZ and NAB were ordered to pay in ASIC v National Australia Bank Limited, once one ratchets them down for the lesser number of contraventions.

74 More generally, the penalty should serve a general deterrence purpose. There is a significant public interest in the proper functioning of Australia’s financial markets and the financial services industry. Further and as I have said, general deterrence is particularly important when imposing a penalty for a contravention which is difficult to detect.

75 Further, the penalty will also serve a specific deterrence purpose. Whilst the manner in which BBSW is set has changed as I have explained earlier, and whilst CBA has taken steps including through the offer to enter into the enforceable undertaking and the admission of attempted contraventions, which indicate that it is unlikely that CBA would repeat the specific conduct that I have discussed, the levying of a significant penalty should operate as an appropriate specific deterrent.

76 Engaging in the necessary intuitive synthesis, I am satisfied that an appropriate penalty is one towards the upper end of the available range. In the circumstances, I will fix a pecuniary penalty for the contraventions in the amount of $5 million.

77 I will make orders and declarations in the terms set out at the outset of these reasons. In essence, so to do will involve CBA in paying the sum of $25 million in total being:

(a) $5 million by way of a pecuniary penalty;

(b) $15 million under an enforceable undertaking for the creation of a separate fund for the benefit of the community; and

(c) $5 million for ASIC’s costs.

I certify that the preceding seventy-seven (77) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate:

SCHEDULE

STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS

A. INTRODUCTION

1. For the purposes of this proceeding only, this Statement of Agreed Facts (Agreed Document) is made jointly by the Plaintiff, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), and the Defendant, Commonwealth Bank of Australia (ACN 123 123 124) (CBA) pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act).

B. INTERPRETATION

2. The Relevant Period in this Agreed Document means from 31 January 2012 to 15 June 2012.

3. Use of the present tense in this Agreed Document is intended to include the past tense unless otherwise stated.

4. A reference to Bank Bills means Negotiable Certificates of Deposit (NCD) and Bank Accepted Bills (BAB).

C. BANK BILLS, PRIME BANK BILLS AND THE OPERATION OF THE BANK BILL MARKET

5. A NCD is a certificate issued by a bank evidencing an interest bearing deposit with the issuing bank for a fixed term, which entitles the holder of the certificate to payment of a specified sum (Face Value) by the bank on the date that the certificate matures.

6. A BAB is a bill of exchange as defined in s 8 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1909 (Cth), which has been accepted by a bank and bears the name of the accepting bank as acceptor, and which obliges the bank to pay the Face Value of the bill to the holder of the bill on the date that it matures.

7. NCDs and BABs are instruments by which a bank, including a Prime Bank (as defined in paragraph 34 below), may borrow funds for a short term, usually for a period of no longer than 12 months.

8. The price of Bank Bills is inverse to their yield. All other things being equal, the higher the yield of a Bank Bill, the cheaper it is. Further, all other things being equal, the lower the yield of a Bank Bill, the more expensive it is.

9. NCDs issued by a Prime Bank and BABs accepted by a Prime Bank are referred to in this Agreed Document as Prime Bank Bills. At all material times, Prime Bank Bills were issued for terms (or “tenors”) of one, two, three, four, five and six months.

10. Prime Bank Bills were recognised by participants in the Bank Bill Market as being of the highest quality with regard to liquidity, credit and consistency of relative yield and were thus able to be traded on a fungible or homogeneous basis.

11. In the Relevant Period, Prime Bank Bills were traded in one of two ways, through interdealer brokers acting as intermediaries by quoting prices at which their respective clients would buy (bid) or sell (offer) Prime Bank Bills as counterparties to and from other participants in the market (Bank Bill Market), or in direct trades between counterparties.

12. ICAP Broker Proprietary Limited (ICAP) and Tullett Prebon (Australia) Proprietary Limited (Tullett) were the two interdealer brokers who were operative in Bank Bill Market in the Relevant Period (Brokers).

13. Trading in the Bank Bill Market during the Relevant Period was usually done by “voice broking” – that is, by participants giving verbal instructions to brokers and the brokers verbally executing transactions between themselves (broker to broker). Participants communicated and gave instructions to brokers via telephone lines which connected each participant to his or her individual broker(s). The telephone lines through which participants communicated with brokers were often connected to speaker boxes, known as “squawk boxes”, at both the participant’s and the broker’s end.

14. In the Relevant Period, for the purposes of trading Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market, CBA had a broker at each of Tullett and ICAP.

15. In the Relevant Period, at or shortly after the time of participants making bids and offers for Prime Bank Bills through the Brokers, each of the Brokers posted the best and most recent bid and offer for Prime Bank Bills of all tenors on their separate electronic systems (that is, one system showing bids and offers through ICAP and one system showing bids and offers through Tullett). This information, once posted, became accessible by, and visible to, participants in the Bank Bill Market with access to the relevant electronic system(s).

16. At all material times during the Relevant Period, trades in Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market were conducted by reference to the yield and tenor of the Prime Bank Bills the subject of the transaction.

17. On each trading day, there was a period of increased liquidity in the Bank Bill Market from shortly before to shortly after 10.00 am (BBSW Rate Set Window). The duration of the BBSW Rate Set Window changed from day to day and was usually for a period of a few minutes before 10.00 am to a few minutes after 10.00 am. Bids and offers made by Bank Bill Market participants during the BBSW Rate Set Window were responsive to bids and offers made by other participants in a dynamic market process. Trading during the BBSW Rate Set Window was often frenetic.

18. Participation in the Bank Bill Market was restricted to wholesale clients under the terms of the brokers’ relevant AFS Licences. During the Relevant Period, Tullett and ICAP did not offer Prime Bank Bill brokerage services to retail clients.

19. Participants traded in the Bank Bill Market for a number of reasons, including to fulfil their obligations to AFMA as a market maker in the Bank Bill Market, management of their funding and liquidity compliance requirements, reduction of their interest rate risk and to realise a profit on a trading position.

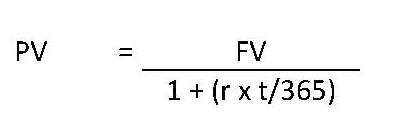

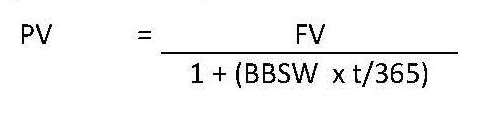

20. Prime Bank Bills traded at a discount to Face Value, to reflect the fact that their holder would only receive the Face Value on the maturity date. The discount to Face Value was calculated on the basis of simple interest (or simple discounting) according to the following pricing discount formula (Pricing Formula) identified in the NTI Conventions published by the AFMA through the NTI Committee:

Where: | |

PV = | Present value (price) |

FV = | Face value |

r = | Per annum yield to maturity |

t = | Time to maturity in days |

Where the yield used to price a Bank Bill in BBSW, the formula for the price (present value) of the Bank Bill is:

21. In the Relevant Period, each Broker issued daily confirmations to Bank Bill Market participants of trades executed through it. However, because the manner in which the Brokers recorded trading information, including the absence of sufficiently precise time, volume and price data for individual trades, it is difficult to recreate the course of trading on any day. Prime Bank Bill trades executed in the Bank Bill Market before noon were for settlement the same day. Trades after noon were for settlement the following day.

22. At all material times, the making by CBA of bids and offers to buy or sell Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market was conduct in trade or commerce for the purposes of subs 12CB(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act).

D. BBSW REFERENCE RATE

23. At all material times, there was a suite of benchmark interest rates in Australian financial markets known as the BBSW. A BBSW was published for each relevant tenor of Prime Bank Bills. The BBSW was understood during the Relevant Period to be a key benchmark interest rate in the financial markets in Australia published by the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA), being a rate independently and transparently determined by reference to bids and offers for trading in Prime Bank Bills.

24. BBSW was widely regarded by the market as independent, objective and transparent and determined based on prices for Prime Bank Bills formed by the competitive forces of supply and demand.

25. BBSW was used as a benchmark and reference interest rate for the pricing and revaluation of Australian dollar loans, bills, derivatives, securities and other instruments including Forward Rate Agreements (defined at paragraph 39 below) and Australian dollar interest rate swaps (defined at paragraph 40 below). Annual turnover in Australian dollar interest rate swaps and Forward Rate Agreements in 2011-12 was $9.8 trillion and $6.1 trillion respectively.

26. At all material times, AFMA established and maintained a procedure entitled “Bank Bill Swap Reference Rate Procedures” (BBSW Procedures) which outlined (amongst other things) the calculation mechanism for the BBSW, the contingency BBSW rate setting mechanism and the responsibilities of the BBSW Committee, which was responsible for procedures relevant to administering the BBSW.

27. Annexed and marked “A” is a copy of the BBSW Procedures applicable during the Relevant Period.

28. During the Relevant Period, the process for the calculation of the BBSW on each Sydney business day was prescribed in the BBSW Procedures as follows:

(a) on each Sydney business day, AFMA received submissions relating to the bid and offer rates of Prime Bank Bills from panellists who were participants in the Bank Bill Market (BBSW Panellists) who had inputted their submissions into the AFMA data system;

(b) AFMA required each BBSW Panellist to make a submission to AFMA by 10.05 am Sydney time on each Sydney business day as to the Panellist’s view as to the mid-point of the bid and offer rates at which Prime Bank Bills in each tenor were trading at 10.00 am on each trading day;

(c) following the receipt of submissions from the BBSW Panellists, the highest and lowest mid-rates submitted for each tenor were eliminated until a maximum of eight submissions remained; and

(d) the BBSW for that day was calculated, or “set”, by AFMA by eliminating the highest and lowest mid-rates from the eight remaining mid-rates and ascertaining, to four decimal places, the average of the six remaining mid-rates for each tenor.

29. At all material times, AFMA published the BBSW from approximately 10.10 am on each Sydney business day and it was made available to subscribers to the BBSW service by information vendors, such as Bloomberg or Reuters, shortly after approximately 10.10 am on the day of calculation, and to the general public on the following day.

30. At all material times, the BBSW was calculated and published by AFMA for the one, two, three, four, five and six month tenors.

E. AFMA

31. AFMA published the AFMA “Code of Ethics and Code of Conduct” (AFMA Code of Ethics).

32. The AFMA Code of Ethics set out the minimum standards, principles and rules of behaviour applicable to AFMA members in the conduct of their business. The AFMA Code of Ethics required AFMA members to:

(a) conduct their trading activities in a fair and orderly manner;

(b) maintain the integrity of financial markets; and

(c) not carry out trading that:

(i) would interfere with the normal supply and demand factors in the market for a financial product;

(ii) had the potential to create artificial markets or prices; or

(iii) was not based on a genuine trading or commercial intention.

33. As a member of AFMA, CBA agreed to abide by, among other things, the AFMA Code of Ethics published by AFMA from time to time and was encouraged to use the AFMA Code of Ethics as a basis to develop and implement more detailed procedures to effect the objectives of the AFMA Code of Ethics at CBA.

F. PRIME BANKS

34. AFMA specified and administered the process for the election and recognition of banks which were designated by AFMA as “Prime Banks”. Participants in the Bank Bill Market included Prime Banks and many other banks and financial institutions which were not Prime Banks.

35. At all material times, CBA was elected and recognised by AFMA as a Prime Bank, as were the other major Australian banks: Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, National Australia Bank Limited and Westpac Banking Corporation.

G. BBSW REFERENCED PRODUCTS

36. In the Relevant Period, CBA issued, entered into and held financial products under which the rights or obligations of the parties referenced or were influenced by or derived from the BBSW for a relevant tenor on a particular day or days.

37. Other entities also entered into and held such products.

38. Such financial products issued, entered into and held by CBA included:

(a) Interest Rate Swaps; and

(b) Forward Rate Agreements (FRAs)

(BBSW Referenced Products).

39. A FRA is an agreement in which the parties agree to exchange interest rate payments on the settlement date based on the difference between an agreed contract rate (the “fixed” side) and a settlement rate (ordinarily, BBSW in the particular tenor on the future settlement date based on a nominal sum). The settlement rate is not fixed or known at the date of agreement and is therefore often referred to as a “floating rate”. A FRA has a payer and a receiver. The “payer” pays the fixed rate on the settlement date (and receives the settlement rate); the “receiver” receives the fixed rate (and pays the settlement rate).

40. An interest rate swap is an agreement between two counterparties to exchange interest payments based on a specified notional amount at two different interest rates, often a fixed rate and a floating rate on a periodic basis for an agreed period of time. One of the most common interest rate swap is a “fixed and floating” swap, under which the counterparties exchange fixed rate payments for floating rate payments at periodic intervals. The parties exchange cash payments based on the interest differential between the fixed rate and the floating rate applied to the notional principal amount. During the Relevant Period, the BBSW was regularly referenced as the floating rate under fixed and floating swaps. For example, a fixed and floating swap for a term of two years might require an exchange of payments every 3 months based on a fixed rate and a floating rate referenced to the 3 month BBSW.

41. The BBSW Referenced Products were each a “financial product” for the purposes of the ASIC Act and a “financial product” for the purposes of Ch 7 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).

H. RELEVANT REGULATORY OBLIGATIONS OF CBA

42. At all material times, CBA provided, and CBA continues to provide, a broad range of banking and financial services in Australia including retail, business and institutional banking.

43. CBA holds an Australian Financial Services Licence (Number 234945) and authority to carry on banking business under s 9 of the Banking Act 1959 (Cth). Annexed and marked “B” is the AFS Licence.

44. In the Relevant Period, CBA was subject to prudential regulation of its banking business. The regulation included Prudential Standards promulgated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) under s 11AF of the Banking Act relating to:

(a) interest rate risk in its banking book (IRRBB) which required it to have in place a framework for measuring, monitoring and managing its IRRBB (under Prudential Standard APS 117);

(b) market risk (including interest rate risk) on trading book positions (Trading Book Risk) which required it to have in place systems for measuring, monitoring and managing general and specific market risk (including interest rate risk) on trading book positions (under Prudential Standard APS 116), and

(c) liquidity which required it to ensure that it had sufficient liquidity to meet its obligations as they fell due (under Prudential Standard APS 210).

45. At all material times during the Relevant Period, CBA supplied to and acquired from counterparties BBSW Referenced Products.

I. ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE OF CBA IN THE RELEVANT PERIOD

46. In the Relevant Period, CBA’s Australian business was structured to include two relevant divisions, being Institutional Banking and Markets (Markets) and Group Treasury (Treasury), both located in Australia.

47. Treasury was primarily responsible for managing CBA’s AUD liquidity, and wholesale funding requirements.

48. Treasury was structured into smaller business units, relevantly including Liquidity Operations (LOPS) and Portfolio Risk Management (also known as Asset & Portfolio Management or Asset & Liquidity Management) (ALM).

49. LOPS managed CBA’s short term funding and prudential liquidity requirements and traded in and held books of financial products, including BBSW Referenced Products.

50. LOPS managed the liquidity portfolio, which was a prudentially regulated asset book that CBA was required to maintain in accordance with APS 210 (APRA’s Prudential Standard APS 210 (Liquidity)). APS 210 required CBA to ensure that it had sufficient liquidity to meet its obligations as they fell due. LOPS managed a portfolio of liquid assets which included, among other products, Bank Bills, floating rate notes and derivative products. Employees within LOPS measured and monitored CBA’s compliance with the liquidity requirements for CBA’s Australian balance sheet. Employees and officers within LOPS made decisions each business day whether to issue Bank Bills for sale, and, if so, in what volume.

51. During the Relevant Period LOPS employees and officers based in Australia relevantly included:

(a) John Pilkington – Head of LOPS;

(b) Roman Groblicki – Dealer Specialist Short End Portfolio, LOPS; and

(c) Mark Hulme – Chief Dealer, LOPS.

52. During the Relevant Period, it was CBA’s policy that responsibility for providing instructions to Brokers for the conduct of transactions in the Bank Bill Market during the BBSW Rate Set Window and determining CBA’s view of the mid-rate of the yield for Prime Bank Bills for submission to AFMA was centralised in a single position known as the Bills Trader. During the Relevant Period, Mr Hulme was the principal Bills Trader.

53. ALM managed the interest rate risk of CBA’s non-traded balance sheet using transfer pricing to consolidate risk into Treasury and hedging the residual mismatch between assets and liabilities using swaps, futures and options.

54. Markets serviced CBA’s major corporate, institutional and government clients. Markets derived revenue by trading in the name of CBA in financial products with counterparties, both through financial markets and otherwise, while managing CBA’s own risks arising from that trading and any holdings of financial products.

55. Markets was structured into smaller business units or desks, relevantly including Interest Rate Swaps (Swaps), Interest Rate Options (IRO) and Short Term Interest Rate Trading (STIRT).

56. Swaps, IRO and STIRT traded in and held books of financial products, including BBSW Referenced Products.

57. Swaps traded in and held Prime Bank Bills, with a face value maximum holding limit of $1B. Swaps traded in the Bank Bill Market by providing instructions to the Bills Trader.

58. At all material times during the Relevant Period, the profitability of Swaps’ trading books was an important metric by which Swaps’ performance was measured at the close of each business day.

59. During the Relevant Period Markets employees and officers based in Australia relevantly included:

(a) Peter Psihoyos – Head of Swaps; and

(b) Grant Barnes – Chief Dealer, Swaps.

60. At all material times, the employees of LOPS and Swaps referred to in paragraphs 51 and 59 above (CBA Traders) were representatives of CBA for the purposes of para 912A(1)(ca) of the Corporations Act.

61. During the Relevant Period, CBA knew that counterparties to BBSW Referenced Products included entities;

(a) which did not participate in the Bank Bill Market; and

(b) which were not listed public companies within the meaning of subs 12CB(5) of the ASIC Act.

62. At all material times, the entry into, and obtaining of rights and assumption of obligations under certain BBSW Referenced Products, including FRAs and interest rate swaps, involved the provision by Swaps of financial services covered by the AFS Licence for the purposes of paras 912A(1)(a) and (f) of the Corporations Act.

63. In entering into certain BBSW Referenced Products, including FRAs and interest rate swaps, and in obtaining rights and assuming obligations under them, Swaps supplied or acquired a financial service to or from the counterparty to the FRA or interest rate swap for the purposes of s 12CB of the ASIC Act.

64. The Market Risk Oversight division within the Market Risk Management Group was responsible for:

(a) oversight of traded and non-traded market risk, operational risk and compliance within Markets;

(b) setting and monitoring trading and credit limits; and

(c) investigation of significant limit breaches.

J. CBA’S CONDUCT POLICIES

65. CBA established and maintained a number of policies and procedures (collectively, CBA Conduct Policies), which policies were applicable throughout the Relevant Period including on 3 February 2012, 9 February 2012, 15 March 2012, 9 May 2012 and 15 June 2012 (Contravention Days):

(a) CBA: Statement of Professional Practice, Market Risk Manual, Group Market Risk Policy, Trading Book Policy Statement, Group Liquidity and Funding Policy, Group Traded Market Risk Standards, Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book Standards, Group Conflicts of Interest Policy (from at least February 2011);

(b) Markets: Code of Conduct, Risk Appetite Statement, Trading Delegations Manual, Front Office Dealing Manual, Market Misconduct Policy, Market Risk Management and Non-Trading Personnel, Traded Market Risk: Limit Excess and Information Trigger Escalation Procedures and Conflicts of Interest Policy; and

(c) Treasury: Group Funding Delegations Mandate, ALM Delegations Mandate, LOPS Traded and Non-Traded Market Risk Delegations Manual, Risk Mandate and Portfolio Risk Management Mandate.

66. In the Relevant Period, CBA staff were required to adhere to the CBA Conduct Policies applicable to them.

67. As part of CBA’s Conduct Policies, CBA required all Markets and Treasury staff, inter alia, to:

(a) comply with the law in all activities;

(b) maintain very high standards of professional integrity, conduct and absolute honesty;

(c) act in a manner which will enhance the reputation of CBA;

(d) know their job, instructions applying to it, follow directions, exercise and not exceed authorities and discretions delegated;

(e) not misuse CBA’s technology and communication facilities in any unlawful, improper or offensive manner;

(f) act in the best interests of clients, and treat them fairly and equitably;

(g) not put the interests of CBA ahead of clients, not put the interests of one client ahead of others and not use client knowledge to advance CBA’s own interests;

(h) identify actual or potential conflicts of interest and manage them to ensure the quality, honesty and integrity of CBA; and

(i) report incidents or suspected incidents of market misconduct and conflicts of interest.

68. In the Relevant Period, CBA failed to have in place adequate policies and procedures requiring CBA staff not to engage in conduct of the nature referred to in section N.

69. On each of the Contravention Days CBA failed to have in place:

(a) adequate policies and procedures for supervising and monitoring the conduct of CBA staff;

(b) adequate supervision of the conduct of CBA staff; and

(c) adequate monitoring of the conduct of CBA staff,

in order to prevent conduct of the nature referred to in section N.

70. At all material times during the Relevant Period, none of the CBA Traders and other staff had been trained adequately about the implications of attempts to affect where BBSW set for their compliance with the policies referred to above.

71. During the Relevant Period, CBA did not actively monitor trading by Swaps and LOPS in Bank Bills to ensure that there was no attempt to affect where BBSW set which if successful may detrimentally affect certain counterparties, including clients of CBA.

72. CBA failed to ensure that on each of the Contravention Days, CBA staff were adequately trained not to engage in the conduct referred to in section N.

K. CBA’S EXPOSURE TO BBSW IN THE RELEVANT PERIOD

73. On each Sydney business day in the Relevant Period, the books managed by Swaps held one or more BBSW Referenced Products, in respect of which CBA’s earnings on its Australian balance sheet and trading book (including the amount of payments that would be received or paid by CBA and/or changes in the economic value of the product) would be affected by the rate at which the BBSW of a particular tenor was set on that day.

74. As a consequence of paragraph 73, on each of the Contravention Days the earnings of the books managed by Swaps in Markets were affected by the rate at which the BBSW for different tenors set. The principal value of the products so affected is referred to in this Agreed Document as the Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure.

75. On each of the Contravention Days, CBA had either of the following Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure positions:

(a) a “long” net Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure in the 3 month tenor, meaning that the net profit of the books managed by Swaps would be increased (or the loss minimised) if the BBSW of that tenor was set by AFMA at a higher rate on that day; and correspondingly the profit would be decreased (or loss increased) if the BBSW of that tenor was set by AFMA at a lower rate on that day; or

(b) a “short” net Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure in the 3 month tenor, meaning that the profit of the books managed by Swaps would be increased (or the loss minimised) if the BBSW of that tenor was set by AFMA at a lower rate on that day and correspondingly the profit would be decreased (or loss increased) if the BBSW of that tenor was set by AFMA at a higher rate on that day.

76. On each of the Contravention Days CBA knew that:

(a) the rights and obligations of CBA to counterparties under its BBSW Referenced Products which reset on those days were affected by the movement in the BBSW in the relevant tenor on those days; and

(b) CBA’s net earnings in Australia were affected by reason of the movement in the BBSW in the relevant tenor on those days.

77. In the Relevant Period, employees and officers in Markets were able to ascertain the Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure from CBA’s systems, and did so on each of the days identified as a Contravention Day.

78. On each Sydney business day in the Relevant Period the Australian earnings of the books managed by Treasury were also affected by the rate at which the BBSW for different tenors set. The principal value of the products so affected is referred to in this Agreed Document as the Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure. The Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure was not systematically provided to employees and officers in Swaps, but on the Contravention Days, employees or officers of Swaps were aware of the Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure through communications with employees and officers in Treasury.

79. CBA also had a long or short exposure once the books of the various desks in Markets and in Treasury were aggregated.

L. COUNTERPARTIES TO BBSW REFERENCED PRODUCTS

80. On each of the Contravention Days on which there was a net long 3 month Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure, CBA was party to one or more BBSW Referenced Products in respect of which a counterparty had an opposite exposure to the 3 month BBSW arising under that product on the Contravention Day, in which event:

(a) if a payment was required to be made by CBA to the counterparty, the payment would have been decreased if the 3 month BBSW set higher on that Contravention Day; and

(b) if a payment was required to be made by the counterparty to CBA, the payment would have been increased if the 3 month BBSW set higher on that Contravention Day.

81. On the Contravention Day on which there was a net short 3 month Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure, CBA was party to one or more BBSW Referenced Products in respect of which a counterparty had an opposite exposure to the 3 month BBSW arising under that product on the Contravention Day in which event:

(a) if a payment was required to be made by CBA to the counterparty, the payment would have been decreased if the 3 month BBSW set lower on that Contravention Day; and

(b) if a payment was required to be made by the counterparty to CBA, the payment would have been increased if the 3 month BBSW set lower on that Contravention Day.

82. On each of the Contravention Days, CBA was a party to one or more BBSW Referenced Products in respect of which a counterparty may have had an exposure to the 3 month BBSW arising under that product on the Contravention Day that was directionally the same as the net exposure of Swaps on the Contravention Day.

83. On each Contravention Day the counterparties with an opposite exposure to the 3 month BBSW referred to in paragraphs 80 and 81 above comprised counterparties that were not listed public companies and that were not participants in the Bank Bill Market.

M. COMMUNICATIONS

84. In the Relevant Period, some employees in Markets and in Treasury communicated with each other by:

(a) telephone;

(b) email; and

(c) instant chat communications in real time.

N. CONTRAVENTION DAYS

3 and 9 February 2012

85. On 31 January 2012 an email exchange between Mr Hulme and Mr Barnes occurred in which:

(a) Mr Hulme requested and obtained Swaps BBSW positions so Treasury could “avoid any days where [Swaps] may need high sets” and requested Mr Barnes provide Swaps rateset ladder for 1, 3 and 6 BBSW for the next 3 months;

(b) Mr Barnes responded “The next week we get short on rate set in general, and then start to get long through the 7th to the 13th, the 9th and 10th are our two main days for a higher set”;

(c) Mr Hulme stated, “based on what we can see we’ll look to do our main buying on 3rd, 6th and 7th. Will leave the screen alone on 9th and 10th and just buy any residual requirements off screen without affecting BBSW. If you need any stock to sell on 9th or 10th let me know. Our preference for any selling would be 9th if that suits”;

(d) Mr Barnes responded “happy to buy some on the 3rd if ok to sell 9th and leave 10th alone”.

86. On 3 February 2012, at a time prior to 9.55 am on that day CBA knew that:

(a) Swaps had a net short Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $2,721,906,556; and

(b) Treasury had a net short Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $136,521,370.

87. On 3 February 2012, Mr Barnes instructed Mr Hulme to buy Prime Bank Bills for Swaps in the BBSW Rate Set Window.

88. On 3 February 2012, CBA purchased 90-day Prime Bank Bills with a Face Value of $800,000,000 in the Bank Bill Market, a substantial majority of which were purchased during the BBSW Rate Set Window.

89. CBA’s trading accounted for approximately 76% of the Face Value of Prime Bank Bills traded in the Bank Bill Market in that tenor on 3 February 2012.

90. Approximately $560,000,000 of those Bank Bills were acquired for Swaps.

91. On 3 February 2012, after the BBSW Rate Set Window, Mr Davies of CBA asked Mr Barnes “did our upstairs just smack the rate set?” to which Mr Barnes responded “don’t confuse our friendly swap desk with our balance sheet”. Mr Barnes in an email headed Swaps Desk Rate Sets stated to Mr Hulme “Thanks for that, pretty good result”.

92. On 3 February 2012, CBA:

(a) intended that CBA’s bids and trades would be observed by BBSW Panellists;

(b) intended that BBSW Panellists who observed the CBA bids and trades would submit lower yields to AFMA that day and BBSW would accordingly set lower;

(c) knew that if the attempt to affect where BBSW set were successful Swaps would have been obliged to pay less than it otherwise would pursuant to the payment obligations CBA had under the instruments giving rise to Swaps’ net short BBSW Rate Set Exposure; and

(d) knew that counterparties did not know of CBA’s conduct and could not, by themselves or their related entities, take steps to address the conduct or the potential detrimental effect of the conduct, if the attempt to affect where BBSW set were successful.

93. On 9 February 2012, CBA knew that:

(a) Swaps had a net long Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $2,891,000,000; and

(b) Treasury had a net long Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $233,990,914.

94. On 9 February 2012, Mr Barnes:

(a) intended to sell the Prime Bank Bills bought on 3 February 2012 into the BBSW Rate Set Window on 9 February 2012; and

(b) instructed Mr Groblicki to sell Prime Bank Bills in the BBSW Rate Set Window.

95. On 9 February 2012 CBA sold 90-day Prime Bank Bills with a Face Value of $700,000,000 in the Bank Bill Market a substantial majority of which were sold during the BBSW Rate Set Window.

96. CBA’s trading accounted for approximately 62% of the Face Value of Prime Bank Bills traded in the Bank Bill Market in that tenor on 9 February 2012.

97. Approximately $440,000,000 of those 90-day Prime Bank Bills were sold for Swaps.

98. On 9 February 2012, CBA:

(a) intended that CBA’s offers and trades would be observed by BBSW Panellists;

(b) intended that BBSW Panellists who observed the CBA offers and trades would submit higher yields to AFMA that day and BBSW would accordingly set higher;

(c) knew that if the attempt to affect where BBSW set were successful, Swaps would have been entitled to receive more money than it otherwise would pursuant to the payment obligations counterparties had under the instruments giving rise to Swaps’ net long BBSW Rate Set Exposure; and

(d) knew that counterparties did not know of CBA’s conduct and could not, by themselves or their related entities, take steps to address the conduct or the potential detrimental effect of the conduct, if the attempt to affect where BBSW set were successful.

15 March 2012

99. On 15 March 2012, CBA knew that:

(a) Swaps had a net long Swaps BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $4,069,000,000; and

(b) Treasury had a net long Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the 3 month BBSW on that day of approximately $543,644,332.

100. On 15 March 2012, at 9.31 am, an email exchange between Mr Hulme and Mr Barnes occurred in which Mr Barnes communicated to Mr Hulme words to the effect that he had better sell all of Swaps’ Prime Bank Bills into the BBSW Rate Set Window and that he was “happy to lose it all at 47”. Mr Hulme warned “you’re gonna get run over potentially that’s the thing”, to which Mr Barnes responded “… I’m happy to just see how we go. So work me 20s but just at 47”.

101. On 15 March 2012, Mr Barnes instructed Mr Hulme to sell Prime Bank Bills in the BBSW Rate Set Window.

102. On 15 March 2012, CBA sold 90-day Prime Bank Bills with a Face Value of $140,000,000 in the Bank Bill Market a substantial majority of which were sold during the BBSW Rate Set Window.

103. CBA’s trading accounted for approximately 25% of the Face Value of Prime Bank Bills traded in the Bank Bill Market in that tenor on 15 March 2012.

104. All of those 90-day Prime Bank Bills were sold for Swaps.

105. After the BBSW Rate Set Window, Mr Hulme reported to Mr Psihoyos that “I sold some at 47 and 46 and that’s where we held it at 46 basically”.

106. On 15 March 2012, CBA:

(a) intended that CBA’s offers and trades would be observed by BBSW Panellists;