FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Commonwealth v Reid [2018] FCA 579

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES:

1. That in the period 2 December 2015 to 11 April 2016, the Respondent (Mr Reid) contravened s 131(1) of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) (the “VET Act”) on 20 occasions because he created or otherwise obtained 4 bogus VET qualifications in his own name concerning Management, Project Management, Marketing and Local Government Administration and:

(a) provided each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications to a company providing recruitment and human resources services to local governments (namely, Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd) and purported to hold each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications as a legitimate VET qualification; and

(b) on 4 separate occasions, provided each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications to a prospective employer (namely, Central Queensland University) and purported to hold each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications as a legitimate VET qualification.

2. That in the period 2 December 2015 to 11 April 2016, Mr Reid contravened s 125 of the VET Act on 20 occasions because he created or otherwise obtained 4 fabricated qualifications in his own name concerning Management, Project Management, Marketing and Local Government Administration. Mr Reid provided them to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd on 1 occasion and Central Queensland University on 4 occasions and on each occasion falsely represented that each of the 4 qualifications was a legitimate VET qualification issued to him by a registered training organisation.

3. That in the period 14 April 2014 to 16 May 2016, Mr Reid contravened s 125 of the VET Act on a total of 57 occasions by making 12 job applications and representing in each that he held multiple VET qualifications when in fact he did not hold those VET qualifications as follows:

(a) On 15 April 2014, he applied to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd for a role in Local Government and falsely represented that he held 10 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Workplace Education, Business Administration, Public Administration, Frontline Management and Sports Coaching.

(b) On 22 May 2014, he applied to Central Queensland Institute of TAFE for the position of Training Business Manager and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Local Government and Information Technology.

(c) On 3 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Coordinator, Counselling Careers & International Student Support and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Local Government and Information Technology.

(d) On 3 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Commercial Manager and falsely represented that he held 7 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Business Administration, Public Administration and Frontline Management.

(e) On 16 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Marketing Officer and falsely represented that he held 7 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Business Administration, Public Administration and Frontline Management.

(f) On 2 December 2015, he applied to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd for a role in Local Government and falsely represented that he held 3 VET qualifications concerning Local Government.

(g) On 17 December 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Coordinator, Counselling, Careers & International Student Support and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

(h) On 17 December 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Discipline Manager – Hospitality & Early Childhood and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

(i) On 3 February 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Deputy Director – Facilities and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

(j) On 18 March 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Government Relations Adviser and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

(k) On 11 April 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Head of Campus Noosa and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

(l) On 16 May 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Business Coordinator and falsely represented that he held 2 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty of $75,705 pursuant to s 137 of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) for the contraventions described in the above declarations.

2. The Respondent is to pay the costs of the Applicant in an agreed sum of $70,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 In September 2017, the Commonwealth of Australia filed in this Court an Originating Application and Statement of Claim. The Respondent to that proceeding is Mr Andrew Scott Reid. An Amended Statement of Claim was filed in 24 October 2017

2 The Commonwealth alleged that Mr Reid had, over a period of more than two years, contravened ss 125 and 131 of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) (the “VET Act”). Declaratory relief was sought together with an order for the payment of pecuniary penalties.

3 In November 2017, a Defence was filed. Mr Reid admitted the allegations of fact made against him.

4 A Statement of Agreed Facts was filed in December 2017. A Supplementary Statement of Agreed Facts was filed a few days later.

5 Given the acceptance on the part of Mr Reid of the allegations of fact, written submissions have been filed proceeding upon the basis of the appropriate quantum of penalties to be imposed. The Commonwealth in its written Outline of Submissions suggested penalties in the range of $86,520 to $112,000. During oral submissions, Counsel on behalf of the Commonwealth submitted that it was appropriate to revise the suggested range to a range of $75,705 to $98,000. Counsel on behalf of Mr Reid has submitted that an appropriate penalty is $75,705 and that such a penalty would not be “oppressive”.

6 It is concluded that a penalty of $75,705 should be imposed pursuant to s 137 of the VET Act and made payable to the Commonwealth. There should also be declaratory relief.

THE VET ACT

7 The objects of the VET Act are set forth in s 2A of the Act as follows:

Objects

The objects of this Act are:

(a) to provide for national consistency in the regulation of vocational education and training (VET); and

(b) to regulate VET using:

(i) a standards-based quality framework; and

(ii) risk assessments, where appropriate; and

(c) to protect and enhance:

(i) quality, flexibility and innovation in VET; and

(ii) Australia’s reputation for VET nationally and internationally; and

(d) to provide a regulatory framework that encourages and promotes a VET system that is appropriate to meet Australia’s social and economic needs for a highly educated and skilled population; and

(e) to protect students undertaking, or proposing to undertake, Australian VET by ensuring the provision of quality VET; and

(f) to facilitate access to accurate information relating to the quality of VET.

8 A “VET Qualification” is defined in s 3 as follows:

VET qualification means a testamur, relating to a VET course, given to a person confirming that the person has achieved learning outcomes and competencies that satisfy the requirements of a qualification.

9 Section 125 provides as follows:

Civil penalty—making false or misleading representation relating to VET course or VET qualification

A person contravenes this section if:

(a) the person makes a representation that relates to:

(i) all or part of a VET course; or

(ii) a course that is held out as being a VET course; or

(iii) part of a course that is held out as being part of a VET course; or

(iv) a VET qualification; or

(v) a qualification that is held out as being a VET qualification; and

(b) the representation is false or misleading in a material particular.

Civil penalty: 120 penalty units.

10 Section 131 provides as follows:

Civil penalty—using a bogus VET qualification or VET statement of attainment

(1) A natural person contravenes this subsection if:

(a) the person obtains a qualification; and

(b) the person knows, or a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to know, that the qualification is not a VET qualification; and

(c) the person purports to hold the qualification as a VET qualification.

Civil penalty: 240 penalty units.

(2) A natural person contravenes this subsection if:

(a) the person obtains a statement of attainment; and

(b) the person knows, or a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to know, that the statement is not a VET statement of attainment; and

(c) the person purports to hold the statement as a VET statement of attainment.

Civil penalty: 240 penalty units.

11 Section 137 provides in relevant part as follows:

Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court may impose pecuniary penalty

…

Court may order wrongdoer to pay pecuniary penalty

(2) If the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court is satisfied that the wrongdoer has contravened the civil penalty provision, the court may order the wrongdoer to pay to the Commonwealth for each contravention the pecuniary penalty that the court determines is appropriate (but not more than the amount specified for the provision).

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(3) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court must have regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found to have engaged in any similar conduct by the court in proceedings under this Act.

…

Conduct contravening 2 or more provisions

(5) If conduct contravenes 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Act against a person for the contravention of any one or more of those provisions. However, the person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty for the same conduct.

12 Section 141 provides in relevant part as follows:

Continuing and multiple contraventions of civil penalty provisions

…

(3) Proceedings against a person for any number of orders to pay pecuniary penalties for contraventions of a civil penalty provision that are founded on the same facts, or form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character, may be joined.

(4) The Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court may make a single order to pay a pecuniary penalty for all the contraventions described in subsection (3), but the penalty must not exceed the sum of the maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for each of the contraventions.

13 As s 2A of the VET Act makes apparent, an object of the Act is to safeguard the quality and integrity of the vocational education and training (“VET”) sector in Australia. Extracted from the Statement of Agreed Facts, a “snapshot” of that sector in 2016 revealed that:

• 4.2 million students were enrolled in the VET system in Australia.

• Almost ¼ of all 15 to 64 year-olds living in Australia were undertaking accredited training in the VET sector.

• Of the students enrolled in the VET system, 46.5% were female, 4% were indigenous and 4.3% were students with a disability. Additionally, 4% of students were overseas or international students.

• There were 4,279 Australian training providers made up of 4,036 registered training organisations and 243 non-registered training organisations (such as community education providers and schools).

• There were about 17 million subject enrolments in private providers. Of that, approximately 32% of those enrolments were funded by Commonwealth or State funds, and approximately 68% were funded by private tuition fees.

• There were also about 8.5 million subject enrolments at TAFE institutes. Of that, approximately 72% of these enrolments were funded by Commonwealth or State funds.

14 There has to date only been one prior decision concerning the quantification of penalties under the VET Act: Commonwealth of Australia v Restar [2016] FCA 657 (“Restar”).

THE ADMITTED CONTRAVENTIONS

15 The conduct of Mr Reid which gave rise to the contraventions occurred between April 2014 and May 2016.

16 The conduct essentially arose from:

his fabrication of four certificates, identified as the “Reid Certificates”, being certificates purporting to show that Mr Reid held an Advanced Diploma of Management (Human Resources); an Advanced Diploma of Project Management; an Advanced Diploma of Marketing; and a Diploma of Local Government Administration. Mr Reid used these fabricated certificates in applying for employment positions between December 2015 and April 2016; and

the making of false representations in job applications on 12 separate occasions in the period between April 2014 and May 2016. The false representations were that he held VET qualifications which he did not hold.

17 The certificates, which have been admitted by Mr Reid to have been fabricated, attracted allegations in the Amended Statement of Claim as to contraventions of both s 125 (at paras [59] to [73]) and contraventions of s 131(1) (at paras [22], [28], [34], [40] and [46]). In the alternative to the alleged contraventions of s 131(1), the Amended Statement of Claim also pleads (at paras [47] to [58]) that Mr Reid contravened s 131(2). In the context of the admissions made with respect to the contraventions of s 131(1), it is unnecessary to consider the alleged contraventions of s 131(2).

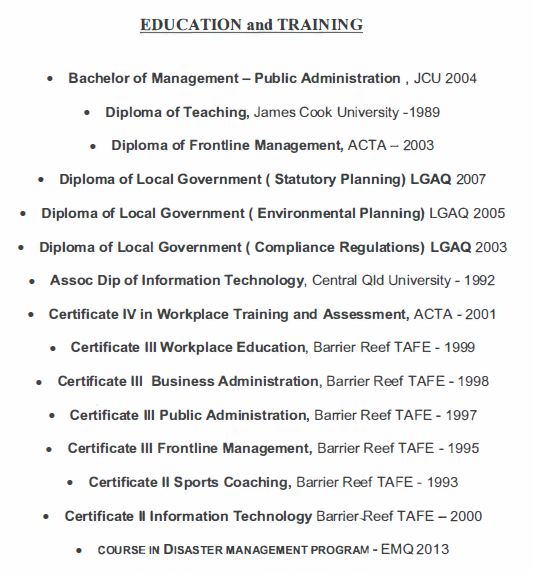

18 The making of the false representations only attracted allegations in the Amended Statement of Claim as to contraventions of s 125 (at paras [81], [87], [93], [99], [105], [111], [117], [123], [129], [135], [141] and [147]). By way of example, in April 2014 Mr Reid applied for a role in Local Government with the Jupiter Corporation. As part of his Resume submitted in support of that application, Mr Reid included the following:

None of the “Certificates” there referred to were the same as the “Reid Certificates”. The allegations made in respect to the April 2014 contraventions centred upon only some of the professed qualifications set forth in his Resume. Those allegations were expressed in the Amended Statement of Claim as follows:

77. The application documents provided by Mr Reid to Jupiter Corporation stated that he held the following qualifications:

77.1. Diploma of Local Government (Statutory Planning) LGAQ 2007;

77.2. Diploma of Local Government (Environmental Planning) LGAQ 2005;

77.3. Diploma of Local Government (Compliance Regulations) LGAQ 2003;

77.4. Associate Diploma of Information Technology, CQU 1992;

77.5. Certificate III Workplace Education, Barrier Reef TAFE, 1999;

77.6. Certificate III in Business Administration, Barrier Reef TAFE, 1998;

77.7. Certificate III Public Administration, Barrier Reef TAFE 1997;

77.8. Certificate III Frontline Management, Barrier Reef TAFE 1995;

77.9. Certificate II Sports Coaching, Barrier Reef TAFE 1993; and

77.10. Certificate II Information Technology, Barrier Reef TAFE 2000.

78. By including those qualifications in his application documents, Mr Reid held out that each of the qualifications was a VET qualification.

79. By providing those application documents to Jupiter Corporation in the context of that application for employment, Mr Reid represented to Jupiter Corporation, in respect of each of those qualifications, that he held that qualification as a VET qualification.

80. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraph 75 above, each of those representations was false.

81. By reason of the matters pleaded above, Mr Reid contravened s 125(v) of the [VET Act] in respect of each of those representations in relation to his application for a role in Local Government.

The short point of present relevance is that care needs to be taken in identifying the nature of the conduct which attract the allegations as to contraventions of s 125 as opposed to the conduct which attract the allegations as to contraventions of s 131(1). Section 125 is directed at false or misleading “representation[s]” as to (inter alia) VET qualifications, whereas s 131(1) is directed at false “VET qualification[s]”, being false testamurs or like documents. Care also needs to be taken to identify those particular “qualifications” which are the subject of the alleged contraventions. Not all of the professed qualifications set forth in Mr Reid’s Resume, for example, have attracted adverse allegations.

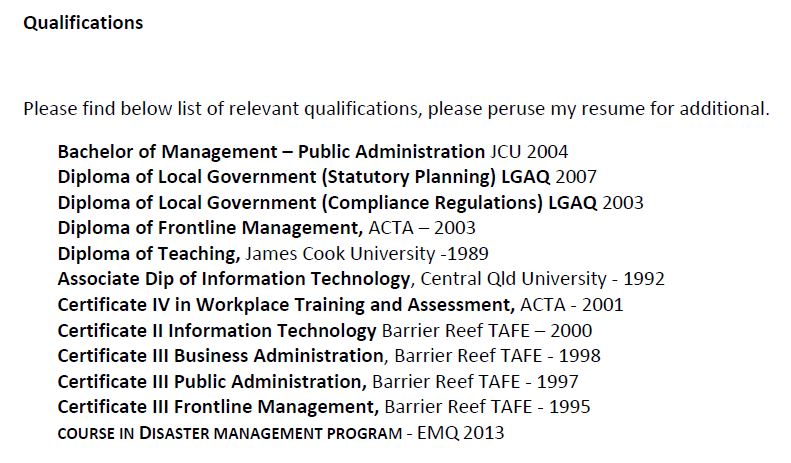

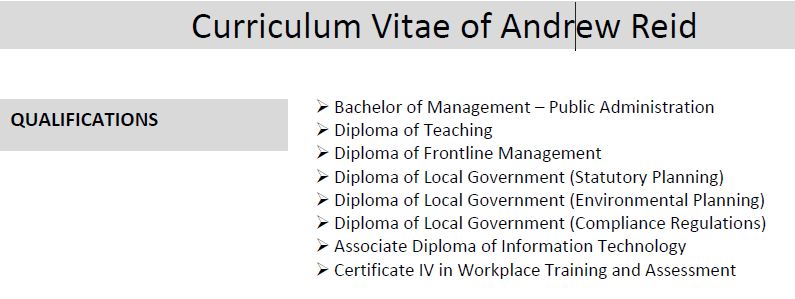

19 By way of further example, in March 2015 Mr Reid applied for the position of Commercial Manager at Central Queensland University. In making that application he submitted a letter to the “[p]anellists” in which he stated:

My CV is enclosed as proof that I have the educational background, professional experience, and track record that Council is seeking.

The application further stated (without alteration):

Mr Reid’s Curriculum Vitae provided in part as follows:

Again, care needs to be taken in identifying which of these professed qualifications attracted allegations as to contraventions of s 125. Those which attracted the adverse allegations of the Commonwealth were identified in para [95] of the Amended Statement of Claim.

20 The tale of deliberately misleading and deceptive conduct persistently pursued by Mr Reid over a two year period need not be repeated.

THE QUANTUM OF PENALTIES TO BE IMPOSED

21 These simple facts gave rise to:

20 contraventions of both s 131(1) and s 125; and

57 contraventions of s 125.

If each of these contraventions is separately considered the total maximum penalty that could be imposed is $2,056,800.

22 The starting point for an assessment as to the quantum of penalties to be imposed in the present case must be s 137(3) of the VET Act. That subsection identifies four specific matters to which the Court “must have regard” when “determining the pecuniary penalty” – but further provides that the Court “must have regard to all relevant matters”, including those specifically identified.

23 During the course of submissions, reference was made by Counsel for both the Commonwealth and for Mr Reid (perhaps not surprisingly) to Restar [2016] FCA 657 and to other authorities of both this Court and the High Court which have addressed the general approach to be pursued when quantifying a civil penalty arising under other Commonwealth legislative regimes. Those submissions were well made. It is considered that valuable guidance as to the approach to be pursued when quantifying a penalty under the VET Act may be gleaned from both the terms of s 137(3) and from those other authorities which address the imposition of civil penalties in other legislative contexts.

24 Given the acceptance on the part of Mr Reid that the principles to be applied were those advocated on behalf of the Commonwealth, it is unnecessary to set forth in any great detail those other authorities. But some brief reference should be made to them. An issue not explored in the present case was whether the express terms of s 137(3) warranted some different approach to that pursued in those other authorities.

25 One difference, however, which was implicitly accepted by Counsel for both Mr Reid and the Commonwealth was that the Court when “determining the pecuniary penalty” to be imposed under the VET Act “must have regard” to each of the four matters set forth in s 137(3).

Civil penalties – guidance from other legislative contexts

26 If the terms of s 137(3) are presently left to one side, the centrally relevant purpose sought to be achieved by the imposition of a civil penalty is the objective of “deterrence” – the objective of both specific deterrence of the particular contravener and the general deterrence of others from engaging in like conduct: cf. Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46, (2015) 258 CLR 482 at 506. French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ there concluded:

[55] No less importantly, whereas criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation, the purpose of a civil penalty, as French J explained in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [[1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152], is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance:

“Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Trade Practices Act] … The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.”

(Footnotes omitted.)

27 Many other decisions of this Court set forth other considerations of relevance when quantifying a civil penalty. One authority frequently cited as a convenient summary of those matters is the decision of Tracey J in Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080 at [14], (2007) 166 IR 14 at 18 to 19 (“Fitzpatrick”). His Honour was there called upon to quantify penalties for admitted contraventions of the Transport Workers Award 1998. His Honour there adopted as a “non-exhaustive range of considerations” which may be taken into account the following:

the nature and extent of the conduct which led to the breaches.

the circumstances in which that conduct took place.

the nature and extent of any loss or damage sustained as a result of the breaches.

whether there had been similar previous conduct by the respondent.

whether the breaches were properly distinct or arose out of the one course of conduct.

the size of the business enterprise involved.

whether or not the breaches were deliberate.

whether senior management was involved in the breaches.

whether the party committing the breach had exhibited contrition.

whether the party committing the breach had taken corrective action.

whether the party committing the breach had cooperated with the enforcement authorities.

the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigation and enforcement of employee entitlements and

the need for specific and general deterrence.

As his Honour has subsequently pointed out, “[e]ach of these considerations has the potential to have both an ameliorative and aggravating impact in the course of the instinctive synthesis process”: Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCA 1213 at [16]. See also: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Ingham (No 2) [2018] FCA 263 at [59] to [66] per Rangiah J.

28 When consideration is given to the matters identified as of relevance to the facts and circumstances of each individual case, it has also been further recognised that the process of fixing the quantum of penalties necessarily remains a process of “instinctive synthesis”: Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8 at [27] to [28], [55] and [78], (2008) 165 FCR 560 at 567 to 568 per Gray J, 572 and 577 per Graham J (“Australian Ophthalmic Supplies”); Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd (No 4) [2017] FCA 580 at [35] per Gilmour J. Most recently, in Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53 (“Flight Centre”), in the context of considering the quantum of penalties to be imposed in respect to contraventions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ observed:

[55] The Court has on a number of recent occasions discussed the operation of s 76 of the Act: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159 and Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (the Agreed Penalties Decision) [2017] FCAFC 113. No substantive question of principle was raised by the parties in submissions. The factors to be taken into account have been canvassed by the parties. There is no requirement for any introductory discussion of principle, other than to say that the task is one that is evaluative, taking into account all the circumstances of the case, not to be reached mechanically or by some illusory process of exactitude, but rather by evaluation that is articulated to a point (but no further) that is useful and meaningful. One starts the process by giving proper weight to the statutory maximum as referable to the most serious kind of contravention. We have given particular regard to the maximum penalty here under s 76: $10 million.

The assessment of Mr Reid’s penalty – s 137 & deterrence

29 There is a substantial overlap between the matters to which the Court “must have regard” by reason of s 137(3) and the matters identified by Tracey J in Fitzpatrick.

30 Each of these matters should be briefly addressed.

The nature & extent of the contraventions – s 137(3)(a)

31 The “nature and extent of the contravention[s]” referred to in s 137(3)(a) of the VET Act has its counterpart in those matters identified by Tracey J in Fitzpatrick.

32 On the facts of the present case, Mr Reid has admitted to 77 legally identifiable contraventions. But with reference to these contraventions, there remains the necessity to:

avoid imposing multiple penalties for identical conduct: s 137(5). In the present case, the same conduct in relation to the “Reid Certificates” gave rise to contraventions of both s 125 and s 131. The Commonwealth does not seek separate penalties for the contraventions of ss 125 or 131(2), but only with respect to the contraventions of s 131(1); and

group together so many of the legally distinct contraventions into what may properly be characterised as a single “course of conduct”. On the facts of the present case, the Commonwealth submits (and the Court accepts) that the 77 contraventions fall into 17 courses of conduct. With respect to those contraventions concerning the fabricated “Reid Certificates”, there were 5 separate courses of conduct, being each of the separate occasions upon which Mr Reid used those certificates. With respect to the remaining 57 contraventions, there were 12 separate courses of conduct, being each of the occasions upon which Mr Reid made separate applications for employment supported by false representations.

The Commonwealth submits that the starting range of penalties that should be imposed in respect to the 17 courses of conduct is $154,500 to $200,000.

Any loss or damage – s 137(3)(b)

33 Unlike the case in Restar ([2016] FCA 657 at [41]), and for the purposes of s 137(3)(b) of the VET Act, there is no substantive evidence in the present case as to “any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravention[s]”.

The circumstances in which the contraventions took place – s 137(3)(c)

34 For the purposes of s 137(3)(c) of the VET Act and the mandate there to have regard to “the circumstances in which the contravention[s] took place”, it is concluded that:

the conduct of Mr Reid over a two year period manifested a persistent and total disregard for the requirements of the VET Act and the conduct was pursued for the selfish purpose of gaining advantage at the expense of the objects and purposes of the VET Act, in circumstances where Mr Reid had significant knowledge of and experience in the VET sector and was aware of the VET Act and the need to comply with it; and

the conduct pursued by Mr Reid manifested a total contempt for the integrity of the VET Sector and selfishly exploited the willingness of employers to rely upon his fabricated certificates and false representations.

35 As acknowledged by Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ in Flight Centre:

[37] The ACCC rejected as a matter of principle the relevance of any belief that unlawful conduct is innocent. Of course a recognition that the conduct is unlawful is a serious aggravating factor; but the converse is not correct as a matter of principle – that innocence is an ameliorating factor.

On the other hand, Mr Reid:

co-operated with the Commonwealth, albeit only really from that point of time when the present proceeding was commenced; and

has now accepted and fully acknowledged his wrongdoing, as evidenced by his co-operation. That co-operation, it may be noted, extended to an acceptance of the factual allegations being made against him at a point of time prior to any indication being given to him as to the range of penalties the Commonwealth would be seeking.

Previous similar conduct – s 137(3)(d)

36 For the purposes of s 137(3)(d) it has been agreed between the parties that Mr Reid has not “previously been found by a court to have contravened ” the VET Act.

All relevant matters – s 137(3)

37 Although not expressly listed in s 137(3) as a consideration to which the Court “must have regard”, it is nevertheless concluded that the relevance of “deterrence” looms large and remains a primary consideration when quantifying any penalty or penalties to be imposed under the VET Act: cf. Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46 at [55], (2015) 258 CLR 482 at 506 per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ.

38 Deterrence may possibly fall within s 137(3)(d) as a factor of relevance when “determining the pecuniary penalty”. In any event, both specific and general “deterrence” remain “relevant matters” within the meaning of the opening phrase of that subsection.

39 Given the extent of the agreement between the Commonwealth and Mr Reid, it is presently sufficient to set forth in summary form the following conclusions as to both general and specific deterrence:

the consideration of general deterrence looms large by reason of the necessity to preserve the integrity of the Australian Qualifications Framework and to protect the interests of those who rely upon the VET system. There is an accepted need to deter those who may be tempted to create fabricated qualifications, especially where there are financial benefits to be thereby obtained; and

the consideration of specific deterrence no longer looms large given the co-operation on the part of Mr Reid and the acceptance of his wrongdoing. The Commonwealth contends, and the Court accepts, that there is no need to increase any penalty which would otherwise be appropriate to secure general deterrence in order to secure specific deterrence on the part of Mr Reid.

The quantification process

40 In such circumstances, and accepting that any process of quantification or assessment is a process of “instinctive synthesis” (cf. Australian Ophthalmic Supplies), it is concluded that the quantification of penalties should:

be at the lower end of the range suggested by the Commonwealth and that the sum of $154,500 should be further discounted by 30% (namely the percentage ultimately advanced by Counsel on behalf of the Commonwealth during the course of the hearing and not the initial 20% advanced in the written submissions) to a resultant sum of $108,150 by reason of the co-operation of Mr Reid.

With reference to the totality principle, the Commonwealth further submits (and the Court accepts) that in respect to the sum of $108,150:

there should be a further reduction of 30% leading to a resultant sum of $75,705.

41 The sum of $154,500, it should be noted, is calculated by reference to 5 separate courses of conduct in respect to the s 131(1) contraventions and 7 courses of conduct in respect to the s 125 contraventions. Penalties are not sought in respect to all contraventions. Of present relevance is that the individual penalties that are sought represent an appropriate percentage of the statutory maximum that could be imposed in respect to a single contravention. Different contraventions, the Commonwealth correctly submits, attract different penalties. The manner of calculation of $154,500 and the percentage of the maximum penalty that could be imposed for a single contravention may be summarised as follows:

Section 131(1) | |||

Date of job application | Penalty imposed | Percentage of maximum (for one contravention) | |

2 December 2015 | $20,000 | 46% | |

17 December 2015 | $20,000 | 46% | |

3 February 2016 | $20,000 | 46% | |

18 March 2016 | $20,000 | 46% | |

11 April 2016 | $20,000 | 46% | |

Total:$100,000 | |||

Section 125 | |||

15 April 2014 | $7,500 | 37% | |

22 May 2014 | $12,000 | 59% | |

3 March 2015 | $5,000 | 25% | |

3 March 2015 | $5,000 | 25% | |

16 March 2015 | $5,000 | 25% | |

17 December 2015 | $5,000 | 23% | |

16 May 2016 | $15,000 | 69% | |

Total: $54,500 | |||

Total:$154,500 | |||

42 Although little is known as to Mr Reid’s financial circumstances, it may nevertheless be inferred that a penalty – even at that reduced amount – will certainly serve as a very real deterrence to him and also serve as a deterrent to all those in the same or similar position. Even if it were to be inferred that payment of the penalty may render Mr Reid insolvent, such a prospect “must not prevent the Court from doing its duty for otherwise the important object of general deterrence will be undermined”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v High Adventure Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 247 at [11], [2006] ATPR 42-091 at 44,564 per Heerey, Finkelstein and Allsop JJ. Any inability to pay a penalty is a factor of “limited relevance”: Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations v Matcham (No 2) [2014] FCA 27 at [250], (2014) 97 ACSR 412 at 443 per Jacobson J. See also: Clean Energy Regulator v MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 at [147] to [149] per Foster J; Restar at [43] to [45] per Flick J; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Arnold (No 2) [2015] FCA 34 at [200] to [204], (2015) 324 ALR 59 at 104 to 105 per Edmonds J.

CONCLUSIONS

43 Mr Reid should be ordered to pay a single penalty in the sum of $75,705 in respect to his contraventions. Section 141(4) of the VET Act is the source of authority for the making by this Court of “a single order to pay a pecuniary penalty for all the contraventions”.

44 The Commonwealth is also entitled to the declaratory relief substantially in the form set forth in the Originating Application. This Court may make declarations upon the basis of an agreed statement of facts (Comcare v Linfox Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 61 at [11], (2015) 144 ALD 593 at 596 to 597 per Flick J; Restar at [28] per Flick J), as is the course pursued in the present proceeding.

45 It was agreed that Mr Reid should pay costs in the agreed sum of $70,000.

THE COURT DECLARES:

1. That in the period 2 December 2015 to 11 April 2016, the Respondent (Mr Reid) contravened s 131(1) of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) (the “VET Act”) on 20 occasions because he created or otherwise obtained 4 bogus VET qualifications in his own name concerning Management, Project Management, Marketing and Local Government Administration and:

1.1 provided each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications to a company providing recruitment and human resources services to local governments (namely, Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd) and purported to hold each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications as a legitimate VET qualification; and

1.2 on 4 separate occasions, provided each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications to a prospective employer (namely, Central Queensland University) and purported to hold each of the 4 bogus VET qualifications as a legitimate VET qualification.

2. That in the period 2 December 2015 to 11 April 2016, Mr Reid contravened s 125 of the VET Act on 20 occasions because he created or otherwise obtained 4 fabricated qualifications in his own name concerning Management, Project Management, Marketing and Local Government Administration. Mr Reid provided them to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd on 1 occasion and Central Queensland University on 4 occasions, and on each occasion falsely represented that each of the 4 qualifications was a legitimate VET qualification issued to him by a registered training organisation.

3. That in the period 14 April 2014 to 16 May 2016, Mr Reid contravened s 125 of the VET Act on a total of 57 occasions by making 12 job applications and representing in each that he held multiple VET qualifications when in fact he did not hold those VET qualifications as follows:

3.1 On 15 April 2014, he applied to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd for a role in Local Government and falsely represented that he held 10 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Workplace Education, Business Administration, Public Administration, Frontline Management and Sports Coaching.

3.2 On 22 May 2014, he applied to Central Queensland Institute of TAFE for the position of Training Business Manager and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Local Government and Information Technology.

3.3 On 3 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Coordinator, Counselling Careers & International Student Support and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Local Government and Information Technology.

3.4 On 3 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Commercial Manager and falsely represented that he held 7 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Business Administration, Public Administration and Frontline Management.

3.5 On 16 March 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Marketing Officer and falsely represented that he held 7 VET qualifications concerning Local Government, Information Technology, Business Administration, Public Administration and Frontline Management.

3.6 On 2 December 2015, he applied to Jupiter Corporation Pty Ltd for a role in Local Government and falsely represented that he held 3 VET qualifications concerning Local Government.

3.7 On 17 December 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Coordinator, Counselling, Careers & International Student Support and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

3.8 On 17 December 2015, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Discipline Manager – Hospitality & Early Childhood and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

3.9 On 3 February 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Deputy Director – Facilities and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

3.10 On 18 March 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Government Relations Adviser and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

3.11 On 11 April 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Head of Campus Noosa and falsely represented that he held 4 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

3.12 On 16 May 2016, he applied to Central Queensland University for the position of Business Coordinator and falsely represented that he held 2 VET qualifications concerning Information Technology and Local Government.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty of $75,705 pursuant to s 137 of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) for the contraventions described in the above declarations.

2. The Respondent is to pay the costs of the Applicant in an agreed sum of $70,000.

I certify that the preceding forty five (45) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Flick. |

Associate: