FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Gram Engineering Pty Ltd v Bluescope Steel Ltd [2018] FCA 539

ORDERS

GRAM ENGINEERING PTY LTD (ACN 002 193 311) Applicant | ||

AND: | BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 April 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of these orders, the parties are to submit agreed or competing short minutes of order in accordance with the reasons for judgment including as to costs or a proposed timetable if there is any dispute about costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

1 Summary

2 The remaining issue in this matter is the assessment of damages the respondent, Bluescope Steel Limited, should pay to compensate the applicant, Gram Engineering Pty Ltd, for Gram’s loss as a result of Bluescope’s infringement of Gram’s registered design relating to a fencing panel sheet.

3 In Gram Engineering Pty Ltd v Bluescope Steel Ltd [2013] FCA 508; (2013) 106 IPR 1 Jacobson J decided that Bluescope had infringed Gram’s registered design. A subsequent appeal was dismissed in Bluescope Steel Ltd v Gram Engineering Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 107; (2014) 313 ALR 311.

4 On 6 June 2013 Jacobson J declared that:

In applying an obvious imitation of Australian Registered Design No. 121344S (the Design) to the fencing panel sheet product known as the “Smartascreen Panel” (a sample of which is Exhibit D in this proceeding) (Smartascreen Panel), and by selling, offering and keeping for sale the Smartascreen Panel during the period 16 April 2005 to 8 February 2010 (the Period), the Respondent has infringed the Design during the Period.

5 Jacobson J also made the following direction:

The proceeding be listed for directions at a date to be fixed in respect of all issues yet to be heard and determined in the proceeding including the issues relating to any pecuniary relief, the steps relating to the Applicant’s election as to an enquiry as to damages or an account of profits and whether or not, and if so, how, the enquiry or account should be referred to a referee to be selected by the parties.

6 It is common ground that by s 156 of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (the 2003 Act), the provisions of the Designs Act 1906 (Cth) (the 1906 Act) apply to both infringement and relief as the Design was registered under the 1906 Act. The declaration made on 6 June 2013 reflected s 30 of the 1906 Act which deemed infringement of a registered design to occur if a person, without the licence or authority of the owner of the design, applies the design or any fraudulent or obvious imitation of the design to any article in respect of which the design is registered. Section 32B of the 1906 Act provides that the relief that a court may grant in an action for the infringement of the monopoly in a registered design includes an injunction and either damages or an account of profits.

7 On 4 August 2016, Gram elected to pursue pecuniary relief in the form of damages.

8 I have decided judgment should be entered for Gram in the amount of $2,078,338 which is based on my assessment that 25% of Bluescope’s sales of Smartascreen, and associated posts, rails and caps and Smartascreen accessories represent lost sales of Gram’s product, GramLine, and associated posts, rails and caps and GramLine accessories. Further, pre-judgment interest should be awarded from 16 April 2005 onwards at the rate provided for in Part 2 of Interest on Judgments Practice Note (GPN-INT). I have decided that interest should be calculated on Gram’s pre-tax loss of profits. It is not appropriate that there be a reduction of interest on account of the fact that Gram could only have accrued interest on 70% of its profits due to its liability to pay PAYG tax each month at the company rate of 30%. Costs should be reserved.

Findings of and about infringement of the Design

9 Jacobson J noted the following:

35 The Design for which Gram applied on 8 February 1994 was registered on 26 August 1994 and expired 16 years later on 8 February 2010.

36 The article for which the Design was registered was a “fencing panel sheet”. ….

37 The Design contained a statement of monopoly “in the features of shape and/or configuration of a fencing panel sheet as illustrated in the accompanying representations”. It also stated that “in considering the extent of the monopoly protection, the longitudinal extent of the article is to be disregarded”.

38 The Design representations which accompanied the registration were as follows:-

10 In rejecting Bluescope’s challenge to the validity of the Design, Jacobson J concluded that the Design involved a combination of features that were sufficiently distinctive to defeat the challenge to validity (at [272]), noting, in particular, the distinctive shape or configuration of the Design’s sawtooth profile (at [298]).

11 At [324] Jacobson J said:

In my opinion, when the Smartascreen panel is viewed as a whole the dominant visual feature is the repeating sawtooth profile consisting of six pans or modules, and the amplitude, wavelength and angles. These features give it a striking physical similarity to the Design and the GramLine product. This is so notwithstanding the difference in the Smartascreen panel consisting of the ridge/valley effect and the micro-fluting. In my opinion those features are comparatively slight and are not sufficient to detract from the overall visual picture of the Design and the GramLine product which I have described above.

12 At [340] he concluded that the “coincidence of market and design pressures in the appearance of the Smartascreen panel point in favour of a finding of obvious imitation”.

Gram, Bluescope, the fencing market and the infringing product

The beginning of steel fencing

13 Since at least the mid-1970s one option for privacy fencing for residential properties in Australia has been painted steel fencing. At this time, John Lysaght (Australia) Pty Ltd, a corporation ultimately absorbed into Bluescope’s corporate predecessor, BHP Billiton Limited, began offering a steel fencing product called “Trimdek”. Bluescope’s Building Components Division included a business unit branded as Lysaght which continued to supply steel fencing for residential purposes under the Lysaght name.

14 At all times Lysaght has used painted steel known as Colorbond in its products. Colorbond is a trade mark under which Bluescope’s (or BHP’s) steel has been sold since 1966.

15 In these reasons Bluescope and Lysaght are interchangeable, although it is apparent that because Bluescope markets its fencing and related products under the Lysaght name many of the witnesses refer to Lysaght and Bluescope as if they were separate entities.

Gram before the infringement

16 Ronald Mann, the principal of Gram, has been involved in the fencing industry since 1975 under the business and then corporate name of Gram Engineering. According to Mr Mann the dominant participants in the steel fencing market until 1983 were Lysaght and Monier (subsequently known as Stramit). Because Gram maintained stock on hand it could fill customers’ orders quickly and the business expanded. By 1986 Gram was offering its own coloured steel fencing system known as “Colorline”.

17 Mr Mann conceived of new fence profiles including a saw tooth or zig-zag profile from 1993. His aim was to create a profile which looked the same from both sides so that one neighbour did not end up with the “good side” of the fence and the other the “bad side”. These designs were registered on 26 August 1994 and included Australian Registered Design No. AU121344S. The commercial manifestation of this design is the product “GramLine” which Gram started to sell from September 1995. GramLine was made from Colorbond until late 2005. Gram sold the posts, rails and caps, as well as other products that were necessary to install GramLine fences. It also sold accessories which were designed to be used with GramLine including lattice screens, gates, ball posts and the like. In common with Lysaght, Gram supplied but did not install its fences.

18 Until 1997 Gram distributed its products from its factory sites and through resellers in New South Wales (NSW) only, where its manufacturing sites are located. Resellers are separate businesses. They are also referred to in these reasons as stockists. Resellers purchase fencing products (and other home building products) wholesale from suppliers such as Lysaght and Gram. Some resellers also offer a fencing installation service but many do not. The resellers sell products to builders, developers, installers and end customers (the homeowners).

19 From 1997 on Gram expanded by starting to sell into new markets via a network of resellers as follows:

from 1997, into Queensland;

from 1997, into Victoria;

from 1997, into Western Australia, particularly Perth; and

from June 2005, into Tasmania.

20 Gram’s records disclose that its main resellers in Queensland included Accolade Fencing, Cut Price Fencing, Watson Fencing and Pine (from 2008), Millers Hardware (from 2008), and Factory Direct Fencing (from 2006). Its main resellers in Victoria included New Style Fencing Pty Ltd, KPKC Pty Ltd trading as Begonia City Fencing, AAA Fencing Pty Ltd, Universal Fencing, Stramit Building, A-Preston and Macedon Fencing. Its main resellers in Western Australia included AA Fencing Enterprises and Stramit Building in Perth. Its main reseller in Tasmania was Quality Steel Fencing and Stramit Building in Hobart and Launceston. Gram did not enter the South Australian market until 2009.

21 As a result of continued expansion of Gram’s business, Gram opened various new factory premises in Smithfield, NSW. In 2001 Gram also acquired a prime-mover to make local deliveries in the Sydney area. From 2004 to 2006, Gram acquired more trucks to make deliveries of its products along the east coast including to Melbourne and Brisbane. After purchasing its second roll-forming machine in 1986 and expanding the business, Gram had a peak number of 60 employees in its Sydney factory in 2003. According to Mr Mann, Gram currently has around 50 employees in Sydney and 10 in other distribution branches elsewhere.

22 At all times Mr Mann operated Gram on the basis that it should have strict quality control of roll forming the fencing panels, stock on hand to be able to meet customer’s needs immediately, minimal borrowings, expand only when profits would allow rather than through borrowing, and that Gram should compete on quality not on price. Gram did not extend credit terms to customers but required payment before delivery, with any credit to be approved by Mr Mann.

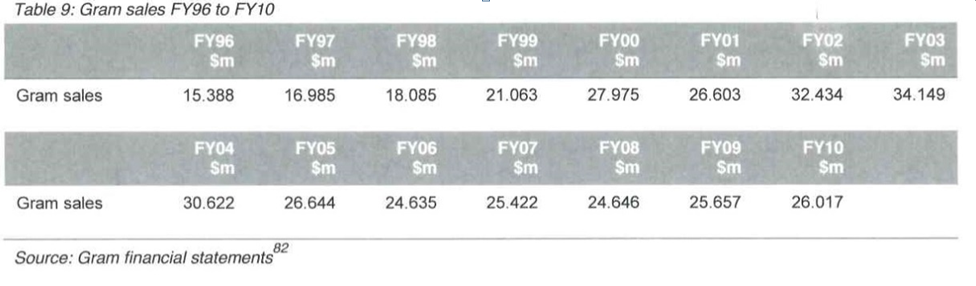

23 Gram’s total sales, including its Colorline and GramLine products, increased substantially up to 2003 but then declined as the following table 9 prepared by one of the experts, Michael Hill, shows.

24 Gram’s financial records disclose that by 2002, despite its expansion program outside of NSW from 1997, 85% of its total sales of all products were in NSW. Mr Mann saw Gram as the market leader in Sydney. As will be apparent from the discussion below, by 2001, so did Bluescope.

25 Gram’s records disclose that GramLine was substantially outselling Colorline by no later than 1998, by which time around 60% to 70% of sales were of GramLine and around 30% to 40% of sales were of Colorline. During the infringement period Mr Hill calculated that the sales of GramLine to Colorline were about 77% GramLine to 23% Colorline.

26 During the period of infringement, the proportion of Gram’s total sales represented by GramLine and associated GramLine products, as calculated by Mr Hill, was around 66%.

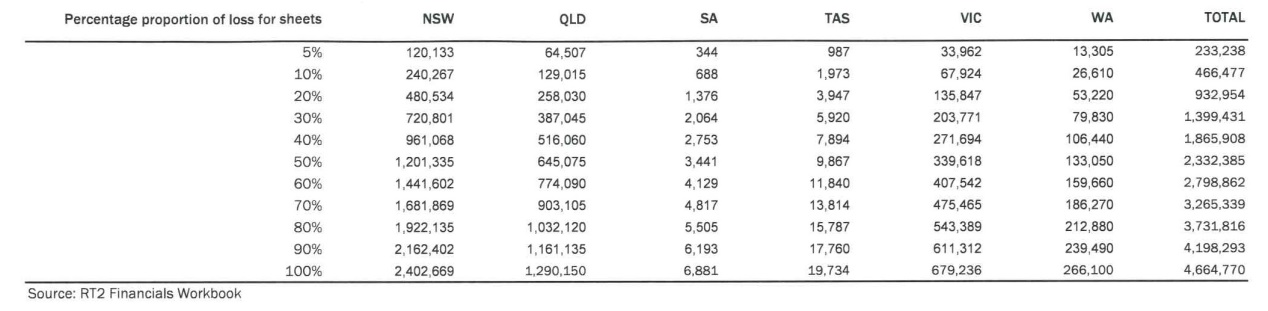

Gram’s total sales of all products before and during the period of Bluescope’s infringing conduct and on a State-by-State basis are shown in the following table which Mr Hill prepared from Gram’s records:

Gram’s total sales of all products before and during the period of Bluescope’s infringing conduct and on a State-by-State basis are shown in the following table which Mr Hill prepared from Gram’s records:

27 It will be apparent that these tables also show Gram’s total sales before and after 2002, which is when Bluescope started selling Smartascreen.

28 As noted, Gram’s fencing products were made with Colorbond steel until late 2005. Bluescope offered a materials warranty on Colorbond steel. Gram also provided a warranty on its fencing products, which it continued to do after ceasing to use Colorbond. According to Mr Mann, Gram began offering a warranty when Lysaght started to offer a warranty on its steel fencing products.

29 Gram charged separately for both wholesale and other deliveries of its products.

30 Gram’s typical advertising brochures before it stopped using Colorbond steel were prepared in conjunction with Bluescope. The registered trade mark “Colorbond” was prominent in these brochures. Gram’s products were identified as “Premium Colorbond Fencing”. GramLine was marketed with the logo “The good side is both sides”, reflecting the fact that GramLine appeared the same from both sides as a result of the sawtooth profile. The marketing of GramLine included statements such as:

• All our Colorbond® fencing products are made from durable, high strength Bluescope® Colorbond® pre-painted steel, backed by Bluescope’s 10 year fence warranty.

• GramLine® Colorbond® steel fencing was designed and engineered to last with both neighbours in mind.

• Exclusively manufactured from Bluescope® steel.

…

BEWARE OF IMITATIONS

• Make sure it’s made from Coolorbond® Steel! Look for the branding on your infill sheets, posts & rails ensuring you are purchasing an Australian Colorbond® product.

• Imported imitations are not backed by the strength & integrity of Australia’s leading steel company Bluescope® Steel Ltd.

Bluescope before the infringement

31 Bluescope (or its corporate predecessor, BHP), through its Lysaght business, also provided Colorbond steel fencing including its original Trimdek product (which became known as Neetascreen). Lysaght’s range included a variety of steel building products; most made using Bluescope produced steel, but also sold some products manufactured by third parties. In terms of fencing, Lysaght operated mainly in the wholesale market under the Lysaght trade name, selling its fencing products to retailers such as Bunnings, Jim’s Fencing and Mitre 10 who would then on-sell it. Lysaght also had its own branches from which it sold its fencing products, along with other home building products including to retail customers.

32 I infer that BHP and Bluescope maintained the trading name of Lysaght for its steel products because that trading name had existed for over 100 years in the building industry. Lysaght has its national head office in NSW and has other State head offices in Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia. In each of these locations Lysaght has one main branch and a large storage site. It also has about 30 additional retail branches nationally.

33 Lysaght had a number of branches in metropolitan Sydney including its main branch at Arndell Park (which was also the manufacturing site), as well as branches at Penrith, Campbelltown, and Parramatta. It also sold into regional NSW and the Australian Capital Territory (the ACT) through its own regional branches (including in Newcastle, Coffs Harbour, Tamworth, Dubbo and Cardiff, Batemans Bay and Queanbeyan) and through key resellers. Key Lysaght resellers included Coffs Metal Market Pty Ltd in Coffs Harbour, Pinus Sawmills Pty Ltd in Queanbeyan, Speedline Fencing Pty Ltd in Newcastle, Bluedog Fences Australia in Tamworth, Alcatraz Fencing Pty Ltd in south Sydney, and WR Engineering Pty Ltd in Canberra. Another reseller, Playsafe Fencing Pty Ltd, in the south of Sydney, mainly stocked Gram products but also stocked some Lysaght products so it could meet customer’s requests for those products.

34 Lysaght had eight of its own retail branches in Queensland from 2006 (in Cairns, Townsville, Mackay, Rockhampton, South Brisbane, Toowoomba, Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast). Lysaght’s key resellers in Queensland included AAA Fencing & Supplies Matnal Pty Ltd on the Gold Coast, Superior Fences and Gates Treloar Investments Pty Ltd on the north side of Brisbane, and South Burnett Fencing Better Boundaries Pty Ltd servicing the Nanango and Kingaroy regions. Lysaght also sold to Ruby Developments Pty Ltd, the developer of retirement villages in Queensland and the Mac Services Group, which established mining camps in regional Queensland.

35 Lysaght had three of its own retail branches in Victoria in Campbellfield, Geelong and Dandenong South. However, unlike in Queensland, most sales in Victoria were through resellers rather than from Lysaght’s own branches. Lysaght’s main resellers in Victoria included Surf City Fencing in Geelong, Oz Colour Fencing in Laverton North, Universal Fencing in Bendigo, and New Colour Fencing in Hallam.

36 Lysaght also exported its fencing products to Climar Industries in the United Kingdom and Topline Trading Ltd in New Zealand.

37 In common with Gram, Lysaght did not seek to compete on price, but quality and service. Unlike Gram it offered standard 30 or 60 day credit terms. Lysaght offered a warranty on its fencing products, in addition to the materials warranty on the Colorbond steel given by Bluescope. Lysaght did not charge separately for wholesale deliveries but, like Gram, charged for other deliveries.

The fencing market generally

38 It is apparent from the evidence that the steel fencing market involved some major suppliers (Bluescope, Gram, Metroll and Stratco) who all had substantial market shares, albeit focused in different locations.

39 Gram had started and developed in Sydney and had achieved an estimated 50% market share in Sydney by 2001, but had been expanding into the other States through resellers.

40 Bluescope sold through its Lysaght arm, which had Lysaght branches and Lysaght resellers including what it considered to be the best regional coverage in NSW perhaps matched only by Metroll.

41 Stratco was also a national business but appears not to have been particularly strong in Sydney or NSW (Mr Mann did not consider them to be a major competitor for example), but was considered by Bluescope to be its major competitor in Queensland.

42 By the beginning of the infringement period, NSW was a mature market for steel fencing and also by far the largest market in terms of volume and money, I infer because of Sydney’s population and associated residential development. The other States were not mature markets and, while much smaller in terms of volume and money than NSW, were expanding throughout the infringement period.

43 On a national basis, the amount of steel fencing used for residential purposes grew by just over 45% between 2001 and 2010. Over much the same period, the value of the steel fencing market grew by about 55%. The main growth areas were Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia. NSW remained the dominant market in terms of consumption and thus sales, but did not experience as much growth as Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia between 2001 and 2010.

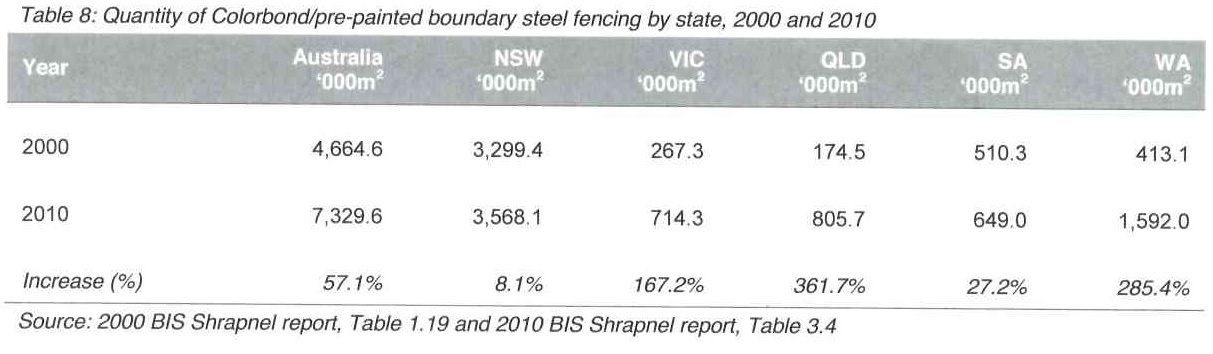

44 The following table, also prepared by Mr Hill, shows the growth in the amount of Colorbond and painted steel fencing used between 2000 and 2010.

45 This table also shows the substantial size of the NSW market compared to the other States.

46 As noted, the major suppliers sold product direct from branches to developers, builders and installers (who were usually regular customers) and retail or end customers, and also sold wholesale to resellers, some of whom were also installers. These resellers also sold to developers, builders and installers (who were usually regular customers) and retail or end customers. As such, Lysaght branches might compete with Lysaght resellers depending on location and Gram branches might compete with Gram resellers depending on location. And, as necessarily follows, Gram and Bluescope were competing not only for resellers but also customers of resellers, albeit that the level of competition varied depending on location (Gram being particularly strong in Sydney and thus NSW).

47 Location was an important factor in competition as between branches and resellers. As Mr Mann said, in metropolitan areas it was desirable that Gram’s selling locations be about half an hour’s driving distance apart or else they would compete with each other. Installers, in particular, needed metropolitan selling locations to be convenient to them as they would mostly collect the stock they required for the day from the supply location in the morning (noting that Gram and Lysaght both charged for non-wholesale deliveries). This also meant having stock on hand was critical, both Mr Mann for Gram and employees from Bluescope noting that they had to have stock on hand to meet demand because a quick supply of product was expected in the market.

48 In regional areas, the evidence indicates, as might be expected, that sale locations generally competed over a greater geographic area than in metropolitan areas given the wide distribution of the locations.

The infringing conduct

49 In common with Gram, which had increased its sales substantially between the mid-1990s and 2000, Bluescope had also experienced continuous growth in its fencing sales over the same period. By 2000 Bluescope believed it had about 30% of the national steel fencing market on a value basis. However, unlike Gram, its sales revenue went down materially in 2001 due to the GST and a downturn in the residential building market. The same impact on Gram is not apparent which continued to grow strongly until 2003.

50 Emma Marlin held the position of Business Development Manager for fencing products in the Marketing Division of Bluescope from 1999 to 2001. Ms Marlin prepared an internal discussion paper in April 2001 titled “Market Justification for New Fence Infill Profile”. This paper recorded Bluescope’s material decline in revenue from steel fencing products including in NSW which was important because NSW represented 41% of Bluescope’s total fencing revenue. Ms Marlin said:

During the last year our market share has fallen by approximately 3% (to 27%) due to a weakening in our competitive position. Our major competitors, Gram and Metroll now offer an infill sheet that looks the same from both sides and aggressively promote them as being superior to our traditional Neetascreen infill sheet. They have also improved the strength of their posts to nearly match our own and this has eroded another of our key points of differentiation. These product innovations have enabled our competitors to successfully gain market share at the expense of BHP Building Products and it is anticipated they will continue to do so as competition intensifies in the depressed residential sector.

51 Ms Marlin’s discussion paper continued:

Competition (symmetrical infill sheets):

Gram Engineering

Product: GramLine (‘saw tooth’ profile)

Width: 2365mm panel (3 sheets)

Feed: 940mm, .35bmt, doublesided Colorbond XFP

Manufactured: Smithfield, Sydney

Brochure: Appendix A

Gram is a formidable competitor in the national fencing market and is believed to be the largest Colorbond fencing manufacturer with approximately 35% share nationally. They are particularly strong in NSW where they are estimated to have at least 50% share. Gram Engineering is well positioned to gain further share inroads through either expansion into other States or through the appointment of new Stockists.

GramLine was launched approximately five years ago and is widely perceived to be the best sheet currently available on the market. They have successfully created this perception by actively lobbying builders and developers and promoting directly to end-users that their sheet is better than traditional infill sheets (including Neetascreen) because it looks the same on both sides and therefore eliminates disputes between neighbours.

…

Their success in developing a position of product superiority has greatly assisted their efforts in appointing new Stockists and gaining market share from BHP Building Products.

Metroll:

Product: Metline (square paling type profile)

Width: 2350mm panel (3 sheets)

Feed: 940mm, .35bmt, doublesided Colorbond XFP

Manufactured: Campbelltown, Sydney

Brochure: Appendix B

Metroll released Metline in Sydney approximately a year ago and promote it as the “the new fencing solution for the new millennium … it’s a great fence whichever way you look at it”.

To date, they appear to be struggling to make inroads into Gram’s market share in NSW. This is most likely due to a weak distribution base in the Sydney metro region (Metroll’s larger Sydney metro stockists refused to purchase from the Sydney operation, preferring to deal with the Newcastle branch!) and apparently they have been plagued by quality problems (poor lapping). These issues combined with a market that traditionally is slow to adopt new profiles have lessened the Metroll threat in the short-term. However, the product is regarded by many as being more attractive than the GramLine product, so the longer term threat should not be underestimated.

52 Ms Marlin concluded:

Final design options:

Two designs were selected as being worthy of a more detailed appraisal, currently referred to as ‘Cascade 2000’ and ‘Paling 2000’.

…

• don’t infringe other manufacturers’ Design Registrations (confirmed by BHP Intellectual Property Group)

…

• Cascade 2000 has a similar appearance to GramLine (sawtooth style profile) and hence it is felt that the product will be readily accepted in the market (remembering that the fencing market is traditionally slow to accept new profiles). It is likely the profile will be considered an acceptable substitute in new housing developments currently dominated by GramLine.

• Paling 2000 has a similar appearance to a paling fence (the dominant material in the Australian fencing market) and strong vertical lines. It is considered to be visually striking, and many feel it is a significant step forward in Colorbond fence design. However, it is probable that the market acceptance would be slower than that of Cascade 2000.

53 Cascade 2000 became known as Smartascreen, which is the product Jacobson J found to infringe Gram’s Design. Jacobson J found as follows:

10 The GramLine fencing sheet was very successful commercially. By 2002 the GramLine range held approximately 35% to 40% of the Australian market for fencing panel sheets. Between 1995 and 2005 Gram purchased almost all of its steel requirements for the GramLine sheet and assorted products from Bluescope and its predecessor.

11 In about the middle of 2002 Bluescope launched its own symmetrical sawtooth or zig-zag fencing panel sheet under the brand name "Smartascreen". There is no escape from the proposition that the Smartascreen fencing panel sheet is very similar in appearance to the GramLine product. In particular, the Smartascreen sheet consists of a six pan sawtooth profile of very similar shape and configuration to the GramLine product, and to Gram's Design.

12 It is also plain that Mr Mann was aware of the similarity at or about the time when the Smartascreen product was launched. Nevertheless, Gram did not institute proceedings against Bluescope until 2011 when the present application and the initial version of the Statement of Claim were filed.

54 Jacobson J also recorded this part of Ms Marlin’s evidence:

185 Ms Marlin was cross-examined on the Discussion Paper, and in particular on her statement that the market would readily accept the Cascade 2000 because of its similar appearance to the GramLine product. The following exchange took place at T 422:-

Thank you. Then just in relation to the phrase you've got "something that would be accepted within the market", one of the reasons you later, in 2001, chose the Cascade 2000 as that it would be readily accepted within the market? --- Yes.

And the reason you thought it would be readily accepted in the market was that it had a similar appearance to GramLine and GramLine's sawtooth profile? --- Yes.

That's why you thought it would be accepted in the market? --- Yes. I thought that the market is very, very slow to accept new products. I think that has been shown time and time again in the fencing market. I did have, in my affidavit, a confidential annexure which I'm happy to talk about, but there is obviously some commercial sensitivities in that.

But I think you were accepting from me that what you thought was, at the time when you chose Cascade in 2001, that it would be readily accepted because it had a similar appearance to GramLine? --- Yes.

And what do you take - when you agree with that, what are you agreeing with - the phrase "similar appearance", what do you take that to mean? --- Well it does have a zigzag profile. There's no doubt about that. That's not to say it's the same at all, but this market is very, very slow to accept new products. Our Neetascreen product, to this day, is still our biggest and most popular selling product because it's very widely accepted in the market. You know, it is difficult to make inroads with new products.

And that similarity of appearance was something you were aware of when, in April, you recommended the selection of Cascade 2000? --- Not so much that. It was just that we knew it would be accepted. Our customers would accept it - that they felt that they would have a product that they could compete with.

Because it conveyed a similar impression of shape? --- It had a - yes - zigzag shape.

Well, it also had similar proportions, didn't it? --- I don't know that that came into my thinking.

55 Although Bluescope started selling Smartascreen in mid-2002, the infringement period is from 16 April 2005 to 8 February 2010. This is because of the limitation period (six years) and the fact that Gram did not commence this proceeding until 2011.

56 According to Mr Mann, when he first heard about Smartascreen, he contacted Gram’s account managers for purchasing of steel from Bluescope, Carl Perry and/or Mark Flint. As soon as he was shown a sample of Bluescope’s saw-tooth fencing panel infill sheet (which became Smartascreen), Mr Mann considered it to be a copy of GramLine. Mr Mann also gave evidence that he met with Mr Perry and/or Mr Flint about Smartascreen and his ongoing relationship with Bluescope as a purchaser of Bluescope Colorbond steel. In that context, Mr Perry and/or Mr Flint prepared a PowerPoint presentation dated 6 August 2002. This presentation recorded that Gram’s purchase of Bluescope Colorbond steel had more than doubled between 1998 and 2002 (to 14,000 tonnes per year). It recorded Gram’s share of the national painted steel fencing market as 37.8%. It also set out as a proposed future arrangement in these terms:

Potential way’s forward

The Desireable future – UNIFIED not FRAGMENTED

To achieve this future

- Gram Engineering supplies LYSAGHTS with GRAMLINE® infills

- LYSAGHTS supplies Gram Engineering post & rail frames &/or the new profile.

- Both companies sell each others products under a common marketing strategy & promotional program

- All three companies define a strategy and to go forward by way of business models, in geographical locations and a plan to grow.

Make COLORBOND® Steel fencing the residential boundary fence of choice throughout Australia.

TARGET to double the fence market within 5 years.

57 Bluescope suggested to Mr Mann in cross-examination that Gram prepared this document, which Mr Mann denied. I accept Mr Mann’s evidence. I consider the document was a marketing exercise by Bluescope, but in so doing Bluescope was seeking to identify Gram’s concerns about what Mr Mann (rightly, as it turned out) considered to be a copy of Gram’s Design and a possible way forward. In this sense, the document does reflect information and proposals that Gram had put to Bluescope. It is thus an internal marketing document of both Bluescope and Gram representing an ideal vision of how Bluescope and Gram might go forward in business together despite what Mr Mann considered to be Bluescope’s infringement of the Design (about which Mr Mann was correct).

58 This idealised vision was never realised, as by late 2005 Bluescope was still selling Smartascreen and Gram had decided to end its commercial relationship with Bluescope by importing its steel from Taiwan, thereby ending its use of Colorbond steel in its products. After this, Gram changed its marketing to remove references to Colorbond. Instead, it said:

All GramLine Steel Privacy Fencing:

• Is manufactured from Quality, Certified, Tested Prepainted Hi-Tensile Steel.

…

GUARANTEE

• The complete GramLine branded range is backed by our exclusive GramLine Plain English 10 year Steel Warranty.

• This ensures you Peace of Mind with the GramLine branded range.

59 Bluescope, via its Lysaght business, marketed Smartascreen along with its other products including Neetascreen (formerly Trimdek) from 2002. Bluescope’s marketing for Smartascreen noted the symmetrical profile, saying things such as:

• “Something special is about to happen between you and your neighbours”

• “Your side looks smarter…and so does your neighbours”;

• “Smarter than your average fence”; and

• “It lets you and your neighbours both enjoy the same great design, because it’s identical both sides”.

60 Bluescope sold substantial numbers of Smartascreen. According to Robert Todorcevski, Bluescope’s National Manager Finance – Building Components, between 15 April 2005 and 8 February 2010, Bluescope sold 2,354,481 lineal metres of Smartascreen infill panels and 4,182,821 lineal metres of steel for the related Smartascreen posts and rails. Mr Todorcevski calculated Bluescope’s gross sales of its Smartascreen infill panels between 2005 and 2010 in the sum of $30,377,796 and associated posts and gross sales of the rails needed to install Smartascreen in the same period in the sum of $11,184,178.

61 Mr Todorcevski was cross-examined about the differences between these figures and his initial evidence which showed even greater gross sales. Mr Todorcevski’s explanation, that his initial calculations had inadvertently included sales of a different walling product which was also described using the prefix “Smarta”, was convincing and I accept it. I also consider that his method of searching for all invoices disclosing a sale of Smartascreen was reasonable given that fencing products are only one of Bluescope’s product lines. While it is possible that Mr Todorcevski missed a relevant sale, this is mere speculation. It involves similar speculation to characterise Mr Todorcevski’s evidence of sales of Smartascreen related products as “low” because of the possibility that a person might have purchased a product related to Smartascreen separately from purchasing Smartascreen. While Mr Todorcevski accepted this as a possibility, as he was bound to do given that he could never exclude the possibility, it is nothing more than speculation. There is no evidence of such an event. Moreover, the event appears inherently unlikely. Smartascreen infill panels had to be sold with Smartascreen post and rails. Smartascreen discretionary additions such as gates and lattices also had to form part of the fence as erected. The possibility of retrofitting a Smartascreen fence with gates or lattice or some other product cannot be eliminated, but it seems far more likely that sales of such items were contemporaneous with the sale of the Smartascreen infill panels.

62 For these reasons I consider Mr Todorcevski’s evidence about the sales of Smartascreen should be accepted. Otherwise, sales of posts and rails and discretionary accessories associated with Smartascreen were the subject of subsequent agreement (which is another reason why characterising Mr Todorcevski’s evidence of sales as “low” is unpersuasive). What Mr Todorcevski’s evidence does show is that Bluescope sold substantial quantities of Smartascreen throughout the infringement period. Even though Neetascreen remained Bluescope’s biggest seller, Smartascreen was plainly a major product for Bluescope.

Other steel fencing products

63 Mr Tanks, Lysaght’s State Sales Manager for Queensland and the Northern Territory, identified Bluescope’s three main steel fencing profiles during the infringement period as Neetascreen, Smartascreen and Miniscreen. Neetascreen (formerly Trimdek) has been sold for nearly 40 years and remains Bluescope’s best-selling fence profile. Bluescope introduced Miniscreen as a premium product, sold at a higher price than Neetascreen and Smartascreen, in 2003. The evidence indicates that no-one considered Miniscreen to be a major product which directly competed with GramLine probably because of the premium price of Minscreen and that it did not appear the same from both sides due to the use of a rail on one side. Given Ms Marlin’s paper, there can be no doubt that Bluescope intended Smartascreen to compete with GramLine on the basis that Smartascreen would be likely to be substituted for GramLine in new housing developments which GramLine “dominated” (in Ms Marlin’s words).

64 Smartascreen was manufactured at Bluescope’s Emu Plains site in Sydney and shipped to its distributors from that site.

65 In addition to the two non-infringing Bluescope profiles, Mr Tanks identified other steel fencing products sold during the infringement period. Stratco (Australia) Pty Ltd sold four profiles of which one, Wavelok, was symmetrical in the sense that it appeared the same from both sides, but was not a sawtooth design. This profile, however, was not released until 2006 and, as Ms Marlin said, the market was slow to adopt new profiles. Metroll Pty Ltd also sold four profiles of which one, Metline, has the same appearance from both sides, but as Ms Marlin had also noted in 2001, Metroll’s symmetrical product was “struggling to make inroads into Gram’s market share in NSW” because Metroll had a “weak distribution base in the Sydney metro region (Metroll’s larger Sydney metro stockists refused to purchase from the Sydney operation, preferring to deal with the Newcastle branch!)” and had been “plagued by quality problems (poor lapping)”.

66 Mr Mann also noted that in 2008 Metroll released a symmetrical fence using a sawtooth profile and Gram took proceedings against Metroll for design infringement. Metroll ceased using this sawtooth design in 2009. Mr Mann said that this Metroll product was a copy of GramLine. It was on the market for about a year. It was removed from the market in 2009 as a result of a mediation between Gram and Metroll in proceedings which Gram took for design infringement.

67 Mr Tanks also identified Dunn & Farrugia Pty Ltd, Steeline Pty Ltd, and Fielders Pty Ltd as other steel fencing providers but it is apparent that the latter two must be minor suppliers.

68 Jacqueline Wall, Bluescope’s NSW Pricing Manager, had particular experience in NSW and the ACT. She identified Bluescope’s main competitors in Sydney as Gram, Stratco, Metroll and Dunn & Farrugia. According to Ms Wall, Stratco had three or four branches in Sydney, two regional NSW branches and a branch in the ACT. Metroll had one branch in Sydney but regional branches in Dubbo, Lismore, Warners Bay, Tamworth and Wagga Wagga, near to some of Bluescope’s Lysaght branches in regional NSW. She said Dunn & Farrugia opened in Penrith in 2005 providing Colorbond steel fencing at aggressively low prices.

69 Jeff Finnegan, a Business Development Manager for Bluescope in NSW, was involved with Dunn & Farrugia. According to Mr Finnegan, Dunn & Farrugia, a new entrant to the supply market, started using Colorbond steel in 2004 and from 2005 to 2010 had a network of branches in NSW and resellers in NSW, Victoria and Queensland. By 2007 Dunn & Farrugia also had started a comprehensive marketing campaign, assisted by Bluescope, both online and through a range of print media. Dunn & Farrugia’s main profile was called ColorMAX Trimdek, which did not appear the same from both sides, but in 2007 it introduced ColorMAX Reflect which did appear the same from both sides. Mr Finnegan identified Dunn & Farrugia’s competitors as Lysaght, Gram, Metroll and Stratco, as well as some others who are not otherwise mentioned and I infer must be localised or minor competitors.

70 Accordingly, during the infringement period, the suppliers which had a product that appeared the same from both sides were Gram from 1995 (GramLine), Bluescope from 2002 (Smartascreen), Stratco from 2006 (Wavelok), and Dunn & Farrugia from 2007 (ColorMAX Reflect), Dunn & Farrugia being a newcomer to the market starting in Sydney in 2004, only a year before the start of the infringement period.

71 Andrew Cook, Bluescope’s State Sales Manager for Lysaght in Victoria and Tasmania, identified Bluescope’s main competitors in Victoria as Metroll and Gram. Gram had a large reseller in Ballarat, an area in which Bluescope did not have a branch or reseller. Bluescope had large resellers in Geelong (Surf City Fencing), Laverton North (Oz Colour Fencing), and Bendigo (Universal Fencing), whereas Gram did not have resellers in those areas. Metroll had three branches, in Delacombe near Ballarat, Moolap near Geelong and Laverton North, and a network of resellers and multiple manufacturing bases in Melbourne and regional Victoria. Mr Cook did not think Stratco and Stramit were major competitors, due to fencing being only a small component of their businesses in Victoria.

72 In Mr Mann’s view, Stratco “has never been a big company in fencing”. I infer that he considered his main competitors to be Metroll and Bluescope.

73 Mr Mann, in common with Bluescope, considered that Dunn & Farrugia sold at aggressively low prices.

74 Bluescope’s premium Miniscreen product which was only introduced in 2003 had an infill profile that was the same from each side, but was constructed with a rail that appeared on one side only. In Mr Mann’s words, Miniscreen was “a good-side-bad-side product. It doesn’t sell much in the marketplace, even though it’s heavily promoted”.

Gram and Bluescope during the infringement period

75 Gram’s evidence included summaries of sales, identifying its major customers, in Queensland, Victoria, Western Australia, Tasmania and South Australia. Gram did not provide similar sales evidence identifying its main customers in NSW, despite NSW being its major market (as noted, around 85% of Gram’s sales were in NSW during the infringement period, although it had begun expanding into other States in 1997). Gram’s evidence also did not identify any customer of Gram that stopped buying GramLine and instead bought Smartascreen. In contrast, Mr Mann did identify a customer of Gram located in Bankstown NSW that stopped buying GramLine and instead bought Metroll fences. He also said that two major customers (wholesale customers as they are resellers), STY Fencing and New Style Fencing from Victoria, stopped buying GramLine and bought Metroll’s Metfence in 2008/2009 (the product that Metroll withdrew from the market after about a year). As Mr Mann put it:

STY Fencing was a client of ours in that period. They probably switched to Metroll on price on that product [Metfence], yes.

…

And do you have a recollection or not as to whether STY Fencing and New Style Fencing were major distributors in Victoria of the Metfence product in 2009? --- Which one is Metfence?

That’s the Metroll product which was what you referred to as a copy of yours, being a sawtooth design? --- Okay. That’s the one which is a copy. Okay. Well, I know they were dealing with Metroll, because they stopped dealing with me in that period.

So in 2009 is this the position: that STY Fencing and New Style Fencing stopped dealing with your GramLine product and bought Metroll’s Metfence product instead? --- Yes.

Right. Thank you. And they did so in substantial quantities, correct? --- Yes.

76 Otherwise Mr Mann gave this evidence about Gram’s markets and customers.

• … our main states were New South Wales – the main state – then Victoria, then Queensland, and we’re now represented in Western Australia to a big degree.

• I sold to several companies in Victoria on a distributor basis, including one called New Style Fencing… they’re no longer a client of ours, except for bits and pieces in Melbourne.

• Five Star Fencing, which is a business I bought… was our first branch [located in Prestons, NSW, operating throughout the infringement period].

• …we could sell to anyone anywhere if they wanted our product. We would help them get our product if they wanted our product. If we couldn’t – if we couldn’t send them to a closer place, it could help them without them dealing directly with us. So we had – it was whatever they wanted as clients. If they wanted us, then we wanted to help them.

• We tried to set up branches in Sydney that are actually within half an hour of each other, that’s our dream, but you – if you set them up too close, then you have conflict between branches, so we try and aim at half-hour centres. We used to have a distributor in Bankstown. He’s now with other people; one of which is Metroll. And so he’s the half-hour, and then there’s an hour to Peakhurst, so we try to have them, you know, in reasonable area of each other. We don’t like to have people on top of each other when they’re distributors.

• [In Queensland] In the period, we had one on the southside called Topdog Fencing, so, you know, we also had our branch in the middle and in – I should restate myself, the one at Deception Bay which is called Accolade, I’m not sure where it was called, but it was in the middle of Brisbane because that’s where we had our branch, and, therefore, Accolade was not far from the centre of Brisbane. We had a client at Caboolture. We had a client near a place called Deception Bay, called Millers Hardware.

• [As to Topdog Fencing]… I don’t remember when they were a client and when they stopped being a client, but they were in that area – the south of Brisbane area.

• Between 2005 and 2010, Gram had a large reseller in Ballarat; correct? --- Yes – Begonia was their name.

• But Gram didn’t have a reseller in Bendigo? --- Universal Fencing was a client of ours.

• You didn’t have a reseller in or within half an hour’s drive of Laverton North, did you? --- New Style Fencing were a good client, and I had – I had AAA Fencing, Macedon Fencing. I didn’t have everybody in Melbourne where I wanted to have them. I didn’t have everything covered, but my business was growing…

• Now, in Brisbane, you did not have a distributor in the south Brisbane area between 2005 and 2010, did you? --- When was Topdog buying my product?

• You did have Accolade Fencing in the suburb of Virginia, in north Brisbane, didn’t you? --- Is that where they were? Yes. Then, I did.

• Then, in Sydney, your Sydney branch was based in Smithfield between 2005 and 2010? --- Yes.

77 There was also evidence that during the infringement period, after Gram stopped using Colorbond steel, its prices for GramLine were lower than Bluescope’s prices for Smartascreen, but the materiality of that difference is not apparent. Both were more expensive, for example, than Dunn & Farrugia which appears to have undercut competitors on price. Having entered the market in 2004, it must be inferred that Dunn & Farrugia had to develop the kind of distribution network that Gram and Bluescope had already developed.

78 According to Bluescope, leaving aside NSW where Gram did not provide evidence of its major buyers, of the top 215 customers who purchased Smartascreen across Australia during the infringement period, six were also customers of Gram’s. Bluescope noted as follows:

These six customers are as follows (bearing in mind that for Gram’s sales, the figure represents sales of all Gram products, and not just GramLine):

(a) Fence Co in Queensland, to which Gram sold up to $80,664 of products and BlueScope sold $57,783 of Smartascreen products during the Period.

(b) New Style Fencing in Victoria, which was a major customer of Gram’s until 2009 at which time it commenced purchasing and supplying Metroll Metfence product in large quantities. During the Period, Gram sold to New Style Fencing $6,135,565 of products, and BlueScope sold to it $13,131 of Smartascreen products.

(c) Universal Fencing in Bendigo, Victoria, to which Gram sold $14,970 in products (Gram’s evidence is silent as to which particular products) and BlueScope sold $263,933 of Smartascreen products during the Period. Mr Cook gave unchallenged evidence to the effect that Universal Fencing was a substantial distributor for Lysaght and sold a large volume of Lysaght fencing during the Period, stocking approximately $200,000 worth of Lysaght Fencing at any given time and only stocked other suppliers’ products if it was specifically asked to do so. Gram did not have a substantial distributor in Bendigo. Universal also required Colorbond. For these reasons, it is highly unlikely that Gram would have captured the Smartascreen sales made to Universal during the Period..

(d) McNamara Fencing in South Australia, to which Gram commenced selling after June 2008 and to which Gram sold $12,325 of products and BlueScope sold $2,789 of Smartascreen products during the period.

(e) Midalia Steel (Mandurah) in Western Australia, to which Gram commenced selling after June 2009 and to which Gram sold $412 of products and BlueScope sold $1,297 of Smartascreen products.

(f) Midalia Steel (Welshpool) in Western Australia, to which Gram commenced selling after June 2007 and to which Gram sold $39,520 of products and BlueScope sold $261 of Smartascreen products.

79 The customers in at least (a) to (d) above are resellers and thus wholesale customers whose purchases from Bluescope must have reflected the demand from their own customers.

80 Mr Tanks, Lysaght Queensland, said that Bluescope increased its marketing efforts for Colorbond steel fencing generally from 2006 aiming to take market share from timber fencing which had been dominant in Queensland until the early 2000s. I note that Stratco, Metroll and Dunn & Farrugia used Colorbond steel in their products and, as such, along with Lysaght would have benefited from this general marketing push.

81 Lysaght’s Colorbond fences were marketed emphasising Colorbond, its strength, quality, and warranty support. In Mr Tanks’ experience while in Lysaght’s Rocklea branch most customers asked for a Colorbond fence rather than a particular profile, but requests for specific profiles did occur, perhaps around 10% of the time. Customers, particularly installers, required stock to be available when they needed it, often collecting the stock for an installation on the same day. In South Brisbane, where Lysaght’s Rocklea branch was located, Mr Tanks perceived Lysaght’s main competitors were Metroll and Stratco because they had branches within 10km. Because of the number of its branches in Brisbane, Mr Tanks thought Stratco was Lysaght’s main competitor, noting Stratco also advertised heavily in the area including for its symmetrical Wavelok profile. Metroll also had a branch in south-west Brisbane and thus was also a competitor. Gram did not have a branch in Brisbane but distributed through a reseller Accolade Fencing in North Brisbane about 35km from Rocklea which, I infer, explains why Mr Tanks did not perceive Gram to be a major competitor. Contrary to Mr Tanks’ perception, Gram must have been a major competitor of Lysaght based on Gram’s sales in Queensland during the infringement period.

82 In regional Queensland, Lysaght had seven branches and Mr Tanks believed no other competitor had the same coverage. Metroll had branches in Cairns, Townsville, Rockhampton, Bundaberg, the Gold Coast, Toowoomba and the Sunshine Coast. Stratco had branches in Bundaberg, the Gold Coast, Toowoomba and the Sunshine Coast. One Gram reseller, Cut Price Fencing, was located on the Gold Coast, near a Lysaght reseller AAA Fencing.

83 Mr Tanks said Lysaght offered deliveries up to 800kms from its branches every two to three days. It also had large resellers such as Mitre 10 who had national agreements with Lysaght. I note that Gram also offered deliveries, the only apparent difference being that Lysaght did not charge separately for wholesale deliveries but did charge separately for other deliveries and Gram charged separately for all deliveries. While some Lysaght wholesale customers said they preferred not to be charged separately for deliveries, I do not infer that Lysaght gave free wholesale deliveries - the delivery price would have been part of Lysaght’s overall costs to wholesale customers, which some of its customers preferred.

84 According to Mr Tanks he had regular communications with customers, mainly the installers who collected products every morning from Lysaght’s Rocklea branch. Don and Brian from Neighbourhood Fencing “liked dealing with us because they didn’t live far away from us”, “they wanted somewhere that was in close proximity to where they lived, but also where their jobs were, which was usually in that local south-west Brisbane area”, and as they did not want to pay a delivery fee they preferred to collect their products each day as required. According to Mr Tanks:

… they chose us – there was some of our competitors that were close to us. They chose us essentially because – they told me that they could place an order either on the day, or the day before, and they knew that they would get what they wanted the following day, when they wanted to pick it up, because we had a full range in stock there, to make up their order, whereas others didn’t. The – they placed a lot of emphasis on the brand and warranty; that they only wanted to sell Colorbond fencing, because they thought that they had BlueScope Steel behind them.

…they did tell me that the brand Colorbond was an important aspect of why they bought from us, and they put a lot of value in the warranty that came with – not just the Lysaght structural warranty of the fence, but also the BlueScope warranty on the Colorbond material.

…

They told me on several occasions that they liked dealing with us because they could send their end-user customers in to have a look at the displays that we had set up. And because the majority of their work was in that south-west Brisbane area, a consumer to come to see us at Rocklea was – was much easier for them to say, “If you want to get a picture of what it looks like, you can go here and have a look at it. This is who supplies our material.”

…

…they told me that they liked dealing with us because of the flexibility – the relationship we had and the flexibility that we had with their credit terms. So most of our account customers, like Brian and Don, would run a 30-day account; however, on occasion, depending on jobs they were doing, they would – there were several occasions where I had to ring them to talk to them about their credit, because they may have gone over their credit limit and they may have had to pay early. And there was other occasions where they had to come and speak to me because there may have been a job that was, you know, significantly bigger, and they hadn’t been paid yet to pay their account to us on time, and they might have needed five or seven days leeway to pay that account. So we had a fairly good relationship with most of our customers like that, where – like, Brian and Don would – if they knew they were going to have an issue with payment, our credit flexibility – they could come and talk to me about it and we could sort it out between the two of us.

85 Daniel Norman, a one man installer:

… he liked the Lysaght – the – the structure and the – and the ease of putting it together. He liked the – the structural – I suppose how solid our fence was. He – he didn’t think that others that he had seen were as solid. Whether that was his opinion, I don’t know, but that’s – that was sort of his words to me quite often.

…he placed a lot of emphasis on the brand with Colorbond, because the installers would usually get their marketing material – so a range of brochures they would carry around with them. They would get them from us so that they could then pass them on to the consumers that they were trying to sell a fence to. So Daniel had a pretty big emphasis on the fact that he could come to us and get that sort of marketing material pretty readily. And we would have things like colour chips and brochures and – and installation brochures that he could pass on to his customers.

… He discussed with me, on occasion, the – his ability to either stay within the credit terms or what flexibility we had to go outside of those credit terms. So he – again, he was a one-man operation and, you know, cashflow sometimes was an issue and he would talk to us about the flexibility, that we had to accommodate what he needed to do.

86 Brian from Fences R Us, “was based around the southwest region of Brisbane as well. He – his big emphasis was on the fact that he could place an order with us today and he could come in and pick it up tomorrow and he knew that we were going to have the stock in the colour that he wanted and he could get everything at the one time”. Further:

… I had conversations with him because I was involved in actually setting up his account with the credit terms and that flexibility of credit terms was something that he had told me he valued.

87 Mr Tanks also dealt with a handful of Jim’s Fencing franchisees, saying:

The ones that we dealt with were mainly from either the southern or the western side of Brisbane. Again, the credit terms with the Jim’s Fencing franchisees, some of them were different in that they had a different credit limit, but they still had 30 day accounts, and again, it was all about proximity to where they either ran their business out of or where their jobs were and the fact that they could place an order and come and pick it up the next day and they were assured that the stock would be there.

…

…because we had an informal agreement with Jim’s Fencing that covered a couple of states, they gave us a list of their franchisees in Queensland and I would follow up on those franchisees, and as I said, in Brisbane, we had a handful, probably five, that dealt with us regularly. There was an amount that didn’t deal with us and, in my conversations with them to ask why, it was pretty much that we were too far away. So a guy from the northside of Brisbane said, you’re too far away. I’m not going to drive all that way just to pick up my fencing.

88 A Lysaght reseller, AAA Fencing on the Gold Coast, told Mr Tanks:

… They placed a lot of value on the branding of Colorbond and the associated warranties for their end user customers. They also placed a lot of value, she told me, on the ability to be able to source the orders on short lead times. They were on the Gold Coast, so they could get pretty much the product that they wanted either in 24 or 48 hours on fairly short notice and, again, because they were – they were a little bit different to the installers, so they had a bigger account in regard to credit limit, but that also was something that she emphasised as being important to their business.

89 AAA Fencing also considered Gram a competitor through its reseller Cut Price Fencing on the Gold Coast, the owner saying to Mr Tanks:

…on occasion… just like any business probably getting annoyed with a competitor she said to me that, you know, Cut Price Fencing were a bit of a thorn in her side as far as, you know, competition in the market place.

90 Harry Treloar of Superior Fences & Gates on the north side of Brisbane:

spoke to [Mr Tanks] on a number of occasions about the importance that he placed on the Colorbond brand and the associated warranties. He placed a lot of value on the fact that he could get the stock from us on the short lead times, and similar to AAA he placed a lot of value on the fact that with Lysaghts he had a 30 day trading account and our, I suppose, flexibility for him over a number of years of being a long-standing customer.

91 Mr Treloar also “spoke to [Mr Tanks] on several occasions about Accolade Fencing being a competitor of his”, Accolade being a Gram reseller.

92 Mr Tanks said the principals of BP & CJ Jenner on the south side of Brisbane:

… placed a lot of emphasis on the Colorbond brand and the warranties that went with it, and essentially Barry worked probably 80 per cent exclusively for one particular builder doing his new homes, and that builder used Colorbond Fascia gutter and roofing that was supplied through us, and his builder and Barry wanted to, I suppose, have a very BlueScope, a very Colorbond brand theme to their estates.

93 South Burnett Fencing servicing the Nanango and Kingaroy regions “placed a great deal of value on our Toowoomba branch’s service …and the fact that we went to that region twice a week with regular deliveries”, according to Mr Tanks.

94 Mr Tanks said Ruby Developments, the developer of retirement villages in Queensland, “placed a lot of emphasis on the fact that he was getting a Colorbond fence that was backed up by the BlueScope warranties”.

95 Topline Trading Limited, being an importer from New Zealand, told Mr Tanks “we won’t go to Stratco and Metroll, because they exist in New Zealand, and that they didn’t think they would be doing them any favours in importing product against their own brand over in New Zealand, and they came to Lysaghts because they knew that we were part of BlueScope and that we supplied Colorbond”.

96 Mr Tanks’ experience with end customers was that they would often ask for Colorbond fencing. Perhaps 10% asked for a specific profile. He could not recall a customer who wanted to buy Smartascreen deciding to buy Neetascreen but accepted it was possible this had occurred, although said that it would have been rare if it did. He said Neetascreen outsold Smartascreen three to one.

97 Mr Tanks recognised that Lysaght’s Queensland competitors included Accolade and Cut Price Fencing, as they were near Lysaght distributors and competing with them, but did not conceive of them as Gram distributors (which they were). According to Mr Tanks:

… because of Stratco’s huge marketing push and consumer awareness, I would think that they would have sold – they would have done everybody some damage with Wavelok. Wavelok was a good profile, and I – I don’t know the numbers, because I don’t work for Stratco.

98 As noted, Wavelok was introduced in 2006, whereas GramLine had been on the market since 1995 and Smartascreen since 2002, when according to Ms Marlin, the market is slow to accept new profiles. It is also apparent that Stratco was a major competitor in Queensland but did not have the same presence in NSW.

99 Mr Tanks agreed that Metroll’s symmetrical product “had a problem with the lapping, and there was an obvious gap in it” (noting that this is not a reference to the product that Metroll released in 2008 and withdrew in 2009 as a result of a mediation with Gram).

100 Ms Wall, Lysaght NSW, identified the Sydney metropolitan area as a key market. She thought that there was not as much competition to Lysaght in regional NSW because Lysaght had a strong distribution network throughout NSW and the ACT. In Sydney she believed that the main competitors of Lysaght were Gram, Metroll, Stratco and Dunn & Farrugia. As to Dunn & Farrugia, I infer that its inroads into the market would have been small initially and then increased during the latter part of the infringement period, particularly after 2007 when it released its symmetrical fence.

101 Most customers, in Ms Wall’s experience while working in Lysaght branches, asked for a Colorbond fence but she agreed that some people came in looking for a specific profile they had seen in a brochure, including the symmetrical profile. In some instances, the symmetrical profile was the selling point. Ms Wall must be referring to end customers in the main here, as I infer that wholesale customers, installers, builders and developers would have known about available profiles.

102 According to Ms Wall, Climar Industries, an export company, said it “wanted to source from BHP building products because they made their fences from Colorbond steel”. Alcatraz Fencing in south Sydney said it bought “Lysaght product because it was made from Colorbond steel. We offered a strength and – strength and material warranty. We had a good delivery service. We offered credit terms”. WR Engineering’s Wayne Read, located in Canberra, said “the reason he purchased from Lysaght was because we had a Colorbond fence made from – sorry – a Lysaght fence made from Colorbond material. And that we had – we offered a good delivery service, and that we offered credit terms”. Playsafe Fencing in the south of Sydney was a big distributor of Gram, about 90% according to Ms Wall, but stocked Lysaght Colourbond “because they wanted to be able to offer a Colorbond product when people came in the door and specifically asked for it”.

103 Ms Wall gave another example as follows:

We had a particular fencer, Bob. He used to come from Bob’s Fencing, Bob Fawkes from Bob’s Fencing. He used to regularly come in, often of an afternoon, and I would discuss with him what work he had on, why he was buying Lysaght, and his reason for buying from Lysaght and from Arndell Park was that it was – he liked the Lysaght system. It was made from Colorbond steel. We had good stocks and we gave him credit terms.

104 Ms Wall said this was typical of her discussions with installers who said they bought from Lysaght “because it was a Lysaght fence made from Colorbond steel, that there was a warranty, both a material and a performance warranty, that we had good stocks in a variety of colours and sizes that they could pick up. We had the – we could also pack individual orders for them if they required so they didn’t have to buy in bulk and we offered credit terms”.

105 Ms Wall agreed that Bluescope’s Smartascreen was intended to compete with GramLine because GramLine was popular in NSW, Gram having about 50% of the Sydney steel fencing market in 2001. Ms Wall had seen Ms Marlin’s paper at around the time it was prepared and knew that Bluescope’s market share had fallen between 2000 and 2001 by about 3%. Ms Wall said this was due to the GST, the downturn in the residential market, and GramLine’s popularity, as well as that of Metroll, and their associated marketing. She agreed that Bluescope anticipated that Gram and Metroll would continue to erode Bluescope’s market share unless something was done, and “the purpose of the production of Smartascreen was to arrest that slide” in market share. She agreed that the strengths of Smartascreen were that it was symmetrical, it overcame potential neighbour disputes, it was a strong profile, able to withstand wind gusts, and was new. Ms Wall marketed the Smartascreen profile by reference to these advantages. I should also note that, while new, Smartascreen was an obvious imitation of GramLine which had been on the market since 1995 when the market was slow to accept new profiles and Bluescope must be inferred to have intended that Smartascreen would be used instead of GramLine in new housing developments.

106 Ms Wall, like Ms Marlin, considered Gram to be a formidable competitor in the national fencing market which, in 2001, held a greater share of the national fencing market than Bluescope did. She agreed that, having built up its branch network in NSW from 2004, from 2006 Bluescope increased its marketing efforts for fencing, accepting that there was at that time “a significant push within Bluescope to increase its marketing efforts around its fencing products” to increase its sales and market share. She agreed that the marketing of Smartascreen within this overall push of its fencing products was intended to divert customers from GramLine to Smartascreen. In so doing, she considered that by 2002, when Smartascreen was introduced, Gram had an extensive distribution network, a short lead time for delivery, active marketing of GramLine and its other products, a good colour range, and a good product in GramLine, and thus was likely to continue to acquire market share in the national market.

107 Mr Cook, Lysaght Victoria, identified key competitors in Victoria as Gram and Metroll. He also said that he often spoke to key resellers in Victoria including the principal of Universal Fencing in Bendigo who said:

… the price needed to be market competitive. It was critical that the product was a Colorbond product. The credit terms were very critical in his ability to continue to trade with us. Speed of delivery and stock availability were also very important, and the integrity of the product when it arrived, so undamaged.

108 The principal of Farrell Fencing in Echuca said much the same thing. STY Metals in Wangaratta (different from STY Fencing) said “the price needed to be market competitive. It must be Bluescope product and he needed his credit terms available to him. It needed to be fast turnaround and have stock available, and the product needed to be delivered undamaged”. Don Sparks Steel Supplies in Albury and Wodonga also said similar things about why they bought from Lysaght, as did Jackal Fencing in Bendigo.

109 Mr Cook agreed Gram had outlets in Melbourne at Sunshine West, but was not otherwise familiar with Gram’s Victorian resellers other than a large reseller in Ballarat, Begonia City Fencing.

110 Mr Finnegan, who dealt with Dunn & Farrugia for Lysaght, said that the owner of that business told him that “Colorbond brought inquiries and customers to his business”.

111 Wayne Read owns and operates WR Engineering Pty Ltd, a supplier and installer of home improvement products including Bluescope’s Lysaght Colorbond steel fencing in Canberra. According to Mr Read, after the bushfires in 2003, the popularity of steel fencing grew in Canberra. WR Engineering’s main competitors were Tymlock Fencing Solutions and Robertson’s Tanks. They were competitors because their outlets were close to that of WR Engineering. Tymlock sold Metroll products and Robertson’s Tanks sold Gram’s products. Dunn & Farrugia entered the ACT market in 2009 or 2010 by opening an outlet in Queanbeyan and WR Engineering lost a lot of its commercial customers to Dunn & Farrugia who sold at a much lower price than others including WR Engineering. This is near the end of the infringement period and confirms my inference that, having started in Sydney in 2004, Dunn & Farrugia had to build up the kind of network Gram already had in place by 2001. As noted, Dunn & Farrugia also did not have a symmetrical fence available until 2007. Otherwise, Mr Read said that WR Engineering has a lot of repeat customers and referrals from customers for whom it has previously installed a fence.

112 Because Stratco and Metroll also sold Colorbond fencing, WR Engineering focused its marketing on the fact that it sold Lysaght Colorbond fencing, and was the only supplier in the Canberra area doing so (at least until Pinus Sawmills began supplying Lysaght fencing products in 2007). Customers (I infer end customers) of WR Engineering generally asked for a Colorbond fence without specifying which profile they wanted. When Gram stopped using Colorbond, WR Engineering used this as part of its marketing. WR Engineering preferred Lysaght as a supplier to Gram because Mr Read believed Colorbond to be a better product. Also, Gram required cash on delivery whereas Lysaght offered credit for 60 days and Gram’s price was not inclusive of freight for wholesale customers whereas Lysaght’s price was inclusive of freight for wholesale customers such as WR Engineering. WR Engineering also had a long relationship with Lysaght which was part of its marketing, which it did not want to change.

113 Before Smartascreen was introduced WR Engineering offered Bluescope’s Neetascreen product. Mr Read had pushed Bluescope to develop a fence which looked the same on both sides which would be a neighbour friendly product like those of Stratco and Metroll (and, of course, Gram). From this, I infer that Mr Read perceived a demand for a symmetrical product from his customers but note that Stratco’s symmetrical product was not released until 2006. In Mr Read’s words, a neighbour friendly profile would make it easier for him to ensure a sale if the neighbours were in dispute. Neetascreen looked different on each side and, I infer, one side was generally perceived to be less attractive than the other (as, if not, there would be no demand for a fence which appeared to be the same from both sides). Neetascreen, however, was WR Engineering’s biggest seller, probably representing around 70% of its steel fencing sales. If Smartascreen had not been available, Mr Read believed he would not have acquired GramLine but might have acquired a neighbour friendly profile from Stratco or Metroll who both used Colorbond steel and offered terms similar to Lysaght.

114 Mr Read also gave evidence that his biggest customer was the ACT Government which “stipulated that they wanted the timber fencing replaced with Colorbond fencing and they wherever possible wanted it to be Colorbond Australian made”.

115 According to Mr Read “the sawtooth profile [Smartascreen] took away from our Neetascreen sales, so potentially the customer was going to buy a Colorbond fence but [if] they choose Neetascreen or Smartascreen was then a choice”. Some customers chose Smartascreen because they had an issue with a neighbour and there was an “argument about who was going to get the good side and who was going to get the bad side”, in which event the symmetrical profile of Smartascreen was a significant selling point. Mr Read accepted that Robertson’s Tanks, which sold GramLine, was in direct competition with WR Engineering given the proximity of the outlets. He accepted also that his competitors extended beyond Canberra into Queanbeyan, Bungendore and Braidwood and Cooma and the Monaro generally, including Goulburn and Yass.

116 Mr Read confirmed that after the 2003 bushfires in the ACT the demand for steel fencing increased, both for replacement fencing and new fencing. Further, that sales of Smartascreen included accessories such as Smartascreen lattices and gates, screws, caps, flashing, lugs, cement and the like. He accepted that between 2005 and 2010 there had been a steady demand for Smartascreen, although the majority of the work was matching to an existing fence. WR Engineering had matched a Smartascreen fence with an existing GramLine fence. This occurred probably once a month.

117 Doug Reid owns and operates Pinus Sawmills in Queanbeyan, which supplies home improvement products including fencing. Until the early 2000s Pinus Sawmills sold only timber fencing. Then the market sought steel fencing and Pinus Sawmills purchased Lysaght Colorbond steel fencing to meet the demand from 2001. Mr Reid considered his two main competitors to be Gram (via the reseller, Robertson’s Tanks) and Metroll which operated in the region in which Pinus Sawmills is located. He considered Stratco to be a minor competitor, which accords with the evidence of Mr Mann.

118 According to Mr Reid, his competitive advantages included same day delivery and free freight on Lysaght products whereas Gram and Metroll charged for wholesale delivery. As noted, I do not infer that Lysaght gave free delivery to wholesale customers. It did not separately charge for freight to wholesale customers which some wholesale customers preferred. From time to time Mr Reid lost customers based on price, as Gram and Stratco’s products are cheaper than Lysaght Colorbond products. Pinus Sawmills’ main customers are local installers as Pinus Sawmills does not install fencing. Between 2005 and 2010, Pinus Sawmills had a base of about 20 main repeat customers to whom they offered credit terms of 30 days. Mr Reid noticed the increased demand for fencing in the region after the 2003 bushfires. In the early 2000s steel fencing was about 3% of sales but by 2010 it was about 30%. The most popular product of Pinus Sawmills in the range was Neetascreen but some customers preferred the Smartascreen profile because it looked the same from both sides which “speeded up” the sale process. Although Mr Reid had been approached to sell both Gram and Metroll products, he was happy with the product, service and price offered by Lysaght which included favourable credit terms, strong marketing support and a good product with reliable service over a lengthy period. If Lysaght ceased supplying Pinus Sawmills, Mr Reid believed that Metroll offered the most similar relationship to Lysaght and also used Colorbond steel.

119 Mr Reid confirmed that his fencing customers were a relatively small number of installers who were repeat customers at his and other outlets. He said people did ask for a symmetrical profile from time to time during 2005 to 2010 but Neetascreen was the preferred product. If they were after a symmetrical profile, however, the customer, mostly a fencing installer, would not buy Neetascreen but Smartascreen. They would do so because the end customer wanted a symmetrical profile, usually because of an issue with a neighbour. While this did not occur frequently, it did occur and Pinus Sawmill’s sales of Smartascreen were not insignificant compared to Neetascreen.