FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 421

ORDERS

ENCOMPASS CORPORATION PTY LTD ACN 140 556 896 First Applicant SAI GLOBAL PROPERTY DIVISION PTY LTD ACN 089 872 286 Second Applicant | ||

AND: | INFOTRACK PTY LTD ACN 092 724 251 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Stand over for further hearing on the question of costs at 9:30 am on 26 April 2018.

2. The parties are to bring in short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons by 5 April 2018.

3. Any debate about orders be dealt with at the hearing on 26 April 2018.

4. The Respondent file and serve a submission not exceeding five (5) pages on costs within seven (7) days hereof.

5. The Applicants file and serve a five (5) page submission in response within a further seven (7) days.

6. The Respondent file and serve a three (3) page reply within a further three (3) days.

7. The reasons of the Court be embargoed until 12:00pm on 6 April 2018 and access to them be granted only to the representatives of the parties during that time.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

I. Introduction

1 The First Applicant, Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd, is the proprietor of Australian Innovation Patent 2014101164 (‘the 164 Patent’) and Australian Innovation Patent 2014101413 (‘the 413 Patent’). The Patents are very similar and are both entitled ‘Information displaying method and apparatus’. Both commence with this statement about the background to the invention:

‘The present invention relates to a method and apparatus for displaying information and in one particular example, to a method and apparatus for displaying information relating to one or more entities, to thereby provide business intelligence.’

2 The priority date for both Patents is claimed to be 25 March 2013 which is the date that standard patent application number 2013201921 was filed (‘the 921 Priority Document’). Both Patents are divisional patents derived from that document. The priority date is contested.

3 The Second Applicant, SAI Global Property Division Pty Ltd, is alleged to be the exclusive licensee of the Patents with the entitlement to exploit them in Australia.

4 The Applicants claim the Respondent, InfoTrack Pty Ltd, has infringed the Patents by the making available from its portal (www.infotrack.com.au) a computer platform entitled ‘Reveal’ from at least March 2015.

5 The Respondent admits that it has infringed the Patents, but denies that the Second Applicant is an exclusive licensee of them. It also alleges by cross-claim that both Patents are invalid and liable to be revoked. This was put on a number of bases:

1. the invention the subject of the Patents is not a manner of manufacture;

2. the Patents do not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough to allow a person skilled in the relevant art to perform it;

3. the priority date for both Patents pre-dates 25 March 2013 which, if true, is accepted by both sides to mean that the Patents are invalid by reason of self-anticipation;

4. both Patents lack novelty as a result of prior art citations;

5. both Patents lack novelty by reason of self-anticipation;

6. both Patents lack an innovative step; and

7. the First Applicant secretly used the Patents before the priority date.

6 In addition to those issues there are some preliminary issues of construction which it is necessary first to resolve in order to address the remaining issues.

II Construction

1. The Field of the Invention

7 Three experts were called to give evidence about these Patents. They were, for the Applicants, Professor Grundy and Professor Estivell-Castro, and for the Respondent, Professor Takatsuka. Although their various areas of expertise were not identical it is accurate to say that they all had expertise in software and computer engineering. They were in agreement that the field of the invention was the ‘field of information retrieval and data management including data visualisation’.

8 The Patents identify a problem existing in that field. This is the problem of data about entities existing in many disparate databases. For example, a person may be recorded as the owner of land in a database maintained by the Land Titles Office, as a director of one or more companies in the register of companies maintained by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’) and as a registered driver at a motor vehicle registry. There can be difficulties in accessing all of this information about a person in a seamless way. Some of the information is not public and some needs to be purchased.

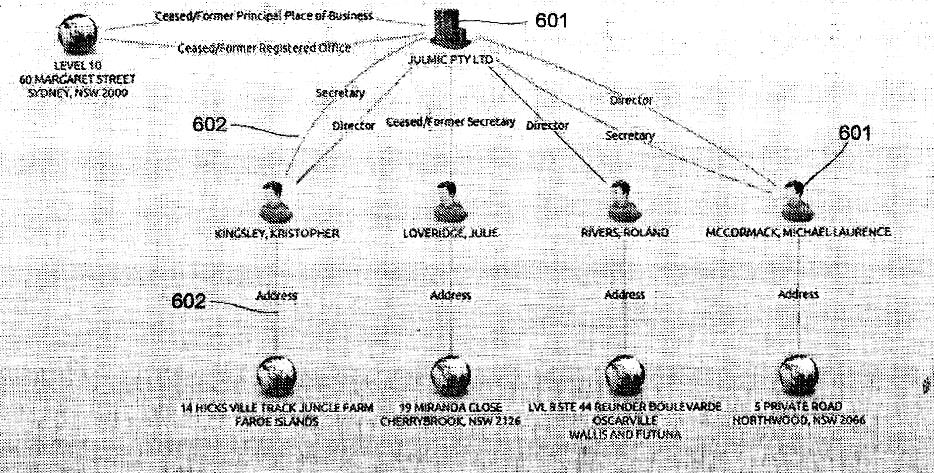

9 The difficulties in searching for information about a person in multiple disparate databases are not new. The Patents reveal at [4] that there exist in the prior art what they term federated search mechanisms. By this it is meant mechanisms which can search across multiple databases and aggregate the results. The Patents identify difficulties within these mechanisms, however. One problem is that they are not particularly user-friendly and have limited ability to store data in different formats. Another difficulty is that these mechanisms are said not to have been able to ‘evaluate business networks’. It became clear during the trial that what this meant was there was no simple way to see as a result of multiple searches what connections might exist between various entities. For example, a search of a lot of land might reveal two individual owners who might also be shown by an ASIC search to be directors of several companies one of which owned the lot immediately next door. The description of the Patents as being methods of displaying information relating to one or more entities by means of a network representation is a little abstract. At [36] of the 164 Patent (and [40] of the 413 Patent) a schematic diagram of one such network representation was given as Figure 6:

10 Another difficultly identified at [6] and [7] of the 164 Patent, of some importance in this litigation, is the fact that different databases frequently store the objects within them in different formats. One may store names with full Christian names, another with initials. In some a postcode may be stored in a separate field to a street address; in others it may be part of the same field. A related difficulty is that spelling errors inevitably intrude into databases. Together, these problems can make it difficult to be sure that one is talking about the same person when conducting a search.

11 Professors Grundy and Takatsuka in their Joint Report both gave evidence that these were the problems which the Patents were designed to address.

2. Principles

12 The relevant principles of construction are not in dispute. A useful distillation of them appears in Hely J’s reasons in Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd [2000] FCA 890; 49 IPR 331 (‘Flexible’) at 347-350 [70]-[81]. That decision has been frequently cited with approval: see, e.g., Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44]-[45]; Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; 222 ALR 155 at 168-9 [67]-[68]. I incorporate into these reasons the explication of the relevant construction principles in Flexible at [70]-[81].

13 Some of the construction issues involve the meaning of ordinary English words but a number involve technical terms upon which the Court received expert evidence. I bear in mind the ordinary caution that one should not approach issues of construction with one eye on the alleged infringements, although this may perhaps have less purchase in the present case as infringement is admitted.

3. The Patents

14 The 164 Patent begins with the background to the invention I have set out above. At [2]-[12] it gives a description of the prior art. At [3]-[9] it identifies the problems I have set out above when describing the field of the invention. At the risk of repetition these are:

information provided across multiple different data depositories makes identifying and accessing relevant information difficult;

existing mechanisms for conducting ‘federated’ searches across multiple databases and aggregating the results are not user-friendly and have limited abilities to handle data stored in different formats;

existing mechanisms are not particularly useful for identifying information relating to specific entities across multiple data sources;

information in disparate data sources is often stored in different formats and there can be a lack of consistency in spelling which can make identifying an individual difficult;

federated searches give rise to a problem of de-duplication, i.e., identical records are treated as separate when they should be removed; and

whilst mechanisms for matching names exist these have not found widespread application.

15 The 164 Patent then gives a summary of two broad forms of the invention. The first is of the invention as a method for displaying information relating to one or more entities, ‘the method including, in an electronic processing device’:

‘a) generating a network representation, the representation including:

i) a number of nodes, each node being indicative of a corresponding entity; and,

ii) a number of connections between nodes, the connections being indicative of relationships between the entities; and,

b) causing the network representation to be displayed to a user;

c) in response to user input commands, determining at least one user selected node corresponding to a user selected entity;

d) determining at least one search to be performed in respective of the corresponding entity associated with the at least one suer selected node by:

i) determining an entity type of the at least one user selected entity;

ii) displaying a list of available searches in accordance with the entity type; and

iii) determining selection of at least one of the available searches in accordance with user input commands;

e) performing the at least one search to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity by generating a search query, the search query being applied to one of the number of remote databases to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity; and,

f) causing any additional information to be presented to the user.’

16 There then follows at [14]-[28] a good deal more by way of description of this method which largely seeks to describe what happens when the user selects one or further searches. It is not necessary to dwell on the detail of this but it includes matters such as:

generating a second network representation within the first by adding further nodes;

generating further user queries;

making the user queries compatible with the underlying data sources and determining the appropriate search; and

disambiguating the retrieved data.

17 It is useful to note that this method is one which is performed using an electronic processing device.

18 The second broad form of the invention is not a method which utilises an electronic processing device but an apparatus in an electronic processing device. It is in these shorter terms:

‘[0029] In a second broad form the present invention seeks to provide apparatus for of displaying information relating to one or more entities, the apparatus including, in an electronic processing device for:

a) generating a network representation, the representation including:

i) a number of nodes, each node being indicative of a corresponding entity; and,

ii) a number of connections between nodes, the connections being indicative of relationships between the entities; and,

b) causing the network representation to be displayed to a user;

c) in response to user input commands, determining at least one user selected node;

d) determining at least one search to be performed in respective of the corresponding entity associated with the at least one user selected node by:

i) determining an entity type of the at least one user selected entity;

ii) displaying a list of available searches in accordance with the entity type; and

iii) determining selection of at least one of the available searches in accordance with the user input commands;

e) performing the at least one search to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity by generating a search query, the search query being applied to one of the number of remote databases to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity; and

f) causing any additional information to be presented to the user.’

19 Thus the two forms of the invention both involve a computer (i.e. an electronic processing device) but one is a method of using such a device and the other an apparatus consisting of such a device.

20 The 164 Patent then sets out a number of drawings. I have already set out Figure 6 at [9] above which is a network diagram. The figures are used in the detailed description of the preferred embodiments which then follow it. To the extent necessary, I will return to these below to deal with some of the construction issues.

21 The claims of the 164 Patent then follow.

22 Claim 1 is as follows:

‘1) A method of displaying information relating to one or more entities, the method including, in an electronic processing device:

a) Generating a network representation by querying remote data sources, the representation including:

i) a number of nodes, each node being indicative of a corresponding entity; and,

ii) a number of connections between nodes, the connections being indicative of relationships between the entities; and,

b) causing the network representation to be displayed to a user;

c) in response to user input commands, determining at least one user selected node corresponding to a user selected entity;

d) determining at least one search to be performed in respective of the corresponding entity associated with the at least one user selected node by:

i) determining an entity type of the at least one user selected entity;

ii) displaying a list of available searches in accordance with the entity type; and,

iii) determining selection of at least one of the available searches in accordance with user input commands;

e) performing the at least one search to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity from at least one of a number of remote data sources by generating a search query, the search query being applied to one of the number of remote databases to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity; and

f) causing any additional information to be presented to the user.’

23 Claims 2 and 3 are variations of the method described in claim 1:

‘2) A method according to claim 1, wherein performing a search includes purchasing a report from a remote data source.

3) A method according to claim 1 or claim 2, wherein the method includes presenting additional information at least in part by modifying the network representation.’

24 Claim 4 is the same as claim 1 but is a claim for an apparatus rather than a method.

25 Turning then to the 413 Patent, its terms and claims are largely the same. The principal difference between the two Patents is the presence of a purchasing step in claim 1.

4. Data sources and Databases

26 Both Patents use these expressions in a way which suggests they are referring to the same concept: see, for e.g., claim 1(e) of the 164 Patent which uses both expressions in the same sentence plainly with the same meaning. The summary of the invention at [13]-[28] uses only the language of ‘database’. But the discussion of the preferred embodiments uses both: see [47], [51], [53], [60], [70], [73], [82], [89], [92], [94], [97], and [152]. Although as a matter of ordinary language there is a difference between a database and data source (the former is one example of the latter but not vice versa) that difference is of no moment to these Patents. They are used, if not interchangeably, then with little or no regard for any formal difference. I will use ‘data source’ for the balance of these reasons. This was also the view of Professor Takatsuka.

5. ‘Electronic Processing Device’ and ‘Remote Data Sources’

27 It will be apparent from claim 1 that the method involves an ‘electronic processing device’ querying ‘remote data sources’.

28 The issue between the parties to which this construction issue relates is the extent to which the Patents are anticipated by the ‘They Rule’ platform which is available to the public on the World Wide Web. They Rule is a platform which uses network representations to demonstrate the links between the rich and powerful in the United States. Although there is debate about this to which I will return, the Respondent’s basic point is that whatever They Rule does it does not retrieve data from data sources which are under the control of third parties (much of this sentence is controversial in ways which may, at least for now, be disregarded).

29 The point of the present construction debate concerned a desire on the Applicants’ part to have the electronic processing device referred to in claim 1 be under the control of one person and the ‘remote data sources’ which are to be interrogated be under the control of another.

30 Professors Grundy and Takatsuka gave evidence about these technical expressions. They agreed on some matters:

(a) an ‘electronic processing device’ was a logical system comprised of one or more computer systems. This could be a single machine or multiple networked machines and the machines could be physical or virtual;

(b) ‘remote data source’ meant a data source which was in some way separate from the system querying it. It could be part of the same logical system as the querying system when that system, for example, was distributed over several machines. It might be physically differently located; for example, the query may originate on a local area network but the data source might be on a wide area network (WAN). Alternatively, it could mean a data source situated in a different logical system altogether such as, for example, that controlled by a third party.

31 It will be seen that viewed at a level of generality which excludes any consideration of the meaning of these expression in the claims to the Patents, the experts agreed that a remote data source could be part of the same logical system as the electronic processing device.

32 Professors Grundy and Takatsuka parted company, however, when it came to what the expression ‘remote data source’ meant in the Patents. Professor Grundy thought ‘in the context of the patents’ that ‘remote data sources’ referred to ‘third party sources’, that is to say, remote systems running on different machines that are under the control of other organisations. Professor Takatsuka disagreed. In his view ‘remote’ could refer to such a state of affairs but it could also include a mere structural or geographic separation not involving third parties.

33 Professor Grundy’s view was based on his reading of the balance of the Patents. His report drew attention to a number of particular matters.

34 First, in the description of the prior art, the specification referred to there being ‘very many electronic data collections containing information about entities’. This was said to give rise to a problem in that ‘having the information provided across multiple different repositories makes identifying and accessing relevant information difficult’. By itself, this is not persuasive. That might be one problem in the prior art but it does not entail that the claim itself is limited to such third party controlled sources. It may certainly entail that it includes them but that is a different proposition.

35 Secondly, Professor Grundy referred to [150]-[151] of the 164 Patent which is in these terms:

‘[0150] The Client Adaptors are a key component for integrating with data sources. The Client Adaptors can be configured to access any format of data storage; the common formats include Web Services over HTTPS, or directly from SQL relational databases using queries, stored procedures or object relational mapping (ORM) technologies.

[0151] In the case of direct database access, the services may be hosted in close proximity to the databases, and typically within an organisation’s existing network environment. For remote access, Encompass Client Adaptors are configured to consume Web Service methods over a secure Internet protocol.’

36 The point he made was that where the 164 Patent intended to refer to a database which was located within an organisation’s network environment this had been signalled by the use of the expression ‘direct dataset access’. But an equally consistent view is that the Patent was simply approaching the matter on the basis that direct database access (i.e. within an organisation) was just a particular instance of accessing a remote data source.

37 Thirdly, Professor Grundy thought that the manner in which the ‘Client Adaptor’ components in [149], [150] and [162] of the 164 Patent supported his view because they were referred to not only as integrating ‘remote’ data but also ‘local’ data. The paragraphs are as follows:

‘[0149] The system typically implements a data integration tier provides the integration to perform the data request and response activities from within the visualisation solution. To achieve this the processing system 210 utilizes “Client Adaptor” components that are configured for each data source and are responsible for translating the data received from the request and applying it to the visualisation model. This allows the processing system 210 to consume various types of data from local or remote hosting via Web Services, or relational database access and file system locations.

[0150] The Client Adaptors are a key component for integrating with data sources. The Client Adaptors can be configured to access any format of data storage; the common formats include Web Services of HTTPS, or directly from SQL relational databases using queries, stored procedures or object relational mapping (ORM) technologies.

…

[0152] The Web Service definition files (WSDL) describe the methods and the request and response parameters, from which the client adaptor translates in the visualisation model framework. In the case of direct database access, the database schema, view models or stored procedure APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) can be used to configure the client adaptor.’

(emphasis added)

38 Thus, so the argument ran, the specification drew a distinction between local data (accessed ‘directly’) and remote data (‘local or remote hosting’). On this view, the specification assumed that ‘remote’ was the complement of ‘local’. But another view, I think, is that these were just both examples of ‘remote data sources’ and the distinction being drawn was just to contrast the way the Client Adaptor operated.

39 A similar point was made about corresponding parts of the 413 Patent and the same observations apply.

40 Fourthly, Professor Grundy thought that claim 1 of the 164 Patent contained mechanisms for entity matching and this showed that external organisations must be involved. This was because ‘normally entities under the same application control and stored in its own database would have a common unique entity identifier’ and would have no need of entity matching. A similar point was made about claims 2 and 4 of the 413 Patent. This point requires some unpicking. The entity matching processes are probably picked up in claim 1(e). I propose to assume that Professor Grundy’s view about entities having a single common identifier within a single system forms part of the hypothetical addressee’s common general knowledge and, hence, that the material is available to determine what meaning that hypothetical address would attach to the words ‘remote data sources’ (cf Flexible at 349 [81]). The key is Professor Grundy’s use of the word ‘normally’ which signals that the proposition for which he contends is not universally true. One such case will be those organisations where an entity has not been given a single identifier across all databases. In the case of such an organisation, a process of entity matching would still be necessary, and, on that view, claim 1(e) would not need to be construed as Professor Grundy suggested.

41 Fifthly, Professor Grundy thought his view was supported by the plural references to ‘remote data sources’ in claim 1 and the description of the invention in paragraphs [82], [84] and [85]. Those paragraphs are as follows:

‘[0082] At step 510, the processing system 210 generates a search query based on the selected search and any provided search parameters, transferring the search query to a data source 205 at step 515. The data source 205 will typically be defined as part of the search with a script or other similar business rules-based process being utilised to format the search query in an appropriate way for analysis and interpretation by the respective data source 205.

…

[0084] The manner in which data analysis is performed will vary depending on the preferred implementation and the nature of the data. For example, the data may be received in the form of an XML file which includes an associated Document Type Definition (DTD) which defines the type of each field used in the data file. The type of field can then be used to identify entities as well as attributes of the entities. Thus, for example, an entity may be an individual or company with attributes of the entity including an entity name, ABN/ACN, or the like. Other entities can include addresses or contact details, other individuals, companies, or the like, as will be appreciated by a person skilled in the art. The analysis process may also involve using pattern matching and/or fuzzy logic, together with techniques for mitigating misspellings or phonic misidentification, as will be described in more detail below.

[0085] Once the processing system 210 has identified entities and relationships from the search results, the processing system generates a first network representation at step 530. The network representation is typically implemented as part of a web page allowing this to be displayed to the user at step 535, for example by having the user’s browser directed to the web page including the network representation. An example network representation is shown in Figure 6. As shown, this includes a number of nodes 601 interconnected via relationships 602. The nodes include a different icon to represent different entity types, with information regarding the entity and nature of the relationship typically being displayed as shown.’

42 It is only if one makes the additional assumption that all of the databases within an organisation are such that disambiguation and entity matching are not necessary that one could infer from these matters that external organisations must be involved. However, I can see no legitimate basis upon which I can make that assumption as a universal truth. Indeed, Professor Takatsuka expressly countenanced that such ambiguities might occur within one’s own data source. Accordingly, I do not accept this argument. A similar point was made about the 413 Patent which I would deal with in the same way.

43 Sixthly, reference was made to [47] of the 164 Patent which was said to draw a distinction between local and remote data sources:

‘[0047] The network representation may be generated in any appropriate manner, but in one example this is achieved by having the electronic processing device ascertain information regarding entities and their relationships and then executing a predetermined procedure for generating the network representation. In this regard, the information can be determined in a number of ways depending on the preferred implementation, such as by examining internal data, or by querying one or more remote data sources, such as repositories of business information, including for example, company register or the like.’

(emphasis added)

44 However, I do not think this helps Professor Grundy’s view. Indeed, to the contrary it shows that the invention takes in arrangements where both local and remote databases may be accessed. This tends to suggest that the working of claim 1 (‘remote data sources’) must encompass both.

45 Seventhly, attention was drawn to [51] of the 164 Patent:

‘[0051] At step 140, the electronic processing device performs the search. This may be achieved in any suitable manner and will depend on the search being performed, the location of stored data or the like. For example, the search may be performed of a data source located remotely to the electronic processing device, such as a remote database or other repository. In this example, the electronic processing device formats the search query and transfers this to the remote data source allowing the search to be performed. Alternatively, the electronic processing device can utilise the search to perform a search of data stored locally, for example in a database attached to the electronic processing device.’

(emphasis added)

46 However, the same point may be made about this. It suggests that the invention includes accessing of both remote and local data sources. Since the words used in claim 1 are ‘remote data sources’ this tends to suggest, rather than to disprove, that that concept includes both ideas.

47 In those circumstances, I do not agree with Professor Grundy’s interpretation of what the Patent requires. He is correct that various parts of the specifications of both Patents assume that there is a distinction available to be drawn between remote and local data sources. However, all that shows is that the invention covers both situations.

48 I conclude that where claim 1 refers to a ‘remote data source’ it is not necessary that that source forms part of a different logical system; nor, correlatively, that it need be under the control of a different organisation.

6. Purchasing Step

49 Claim 2 of the 164 Patent deals with the purchasing step this way: ‘A method according to claim 1, wherein performing a search includes purchasing a report from a remote data source’. By contrast, claim 1(e) of the 413 Patent is as follows:

‘e) performing the at least one search to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity from at least one of a number of remote data sources by purchasing a report from the remote data source; …’

50 There was a minor issue as to whether the purchasing step might be satisfied by a subscription having been previously paid. I do not think it would be. It seems clear to me that in both Patents the act of purchase comes after the search. A pre-existing subscription cannot be fitted into that language.

7. Search ‘from at least one of a number of remote data sources’

51 The origins of this dispute once again lie in They Rule which accesses only a single database.

52 As originally conceived, the debate between the parties turned on the words in claim 1(e) of the 164 Patent which required a search regarding an entity ‘from at least one of a number of remote data sources’. For the Applicants, it was said that this required a method which could provide for the search of more than one data source. For the Respondent it was said that claim 1(e) required a system which could, but need not, be able to query more than one database. Whilst it is true that it may be said as a matter of formal semantics that a selection of one remote data source is encompassed in the idea of ‘at least one of a number of remote data sources’ I do not think this is what it means as a matter of ordinary language. The Respondent’s construction results in ‘at least one of a number’ meaning ‘one of a number’. In my opinion, the reference to ‘at least one’ carries with it the idea that the method requires that one database be accessed and that there exist a capacity to access more than one.

8. Entity Matching

53 Paragraphs [7] and [8] of the 164 Patent are as follows:

‘[0007] For example, when combining information about a person from different data sources, as occurs with federated searches, it is critical that the different records do indeed refer to the same person. The decision that two or more records are likely to be the same, depends on matching different aspects in each record, such as name, address, date of birth, place of birth. The most important component is the personal name as it is always the common element across different data holdings, which inevitably will hold different combinations of personal information.

[0008] As the major element of this identification process, matching names can be fraught with difficulty. Apart from lack of consistency in recording names (middle initial or name, different name orders etc.), in many instances there are small inconsistencies in spelling names, either introduced accidentally as typographic errors, or deliberately as a means of obscuring the real identity of a person.’

54 These indicate that it is critical when information is retrieved from a data source about an entity that ‘the different records do indeed refer to the same person’. Related to that is the problem of variant or erroneous spelling.

55 The specification refers at various places to steps which may be taken to ensure that the correct entity has been retrieved. For example, at [22]-[25] in the description of one of the preferred embodiments there is description of such a matching process:

‘[0022] Typically the method includes:

a) determining search results data indicative of additional information; and,

b) analysing the search results data to identify at least one entity.

[0023] Typically the method includes identifying at least one entity by at least one of:

a) pattern matching; and,

b) fuzzy logic.

[0024] Typically the method includes identifying at least one entity by at least one of:

a) determining entity details from the search results data, the entity details including at least one of:

i) an entity name;

ii) an entity address; and,

iii) date of birth;

b) comparing the entity details to existing entity details for existing identified entities; and,

c) determining if the entity is one of the existing entities based on the results of the comparison.

[0025] Typically the method includes:

a) modifying the entity details in accordance with at least one of:

i) defined misspellings; and,

ii) phonetic equivalents; and,

b) comparing modified entity details to the existing entity details.’

56 Similarly, at [60]-[61] this appears:

‘[0060] It will be appreciated that when searching a range of different data sources, additional information may be determined in a number of different formats. Accordingly, the technique typically involves determining search results data indicative of the additional information and then analysing the search results data to identify at least one entity. The analysis process can include utilising pattern matching and/or fuzzy logic in order to identify entities and relationship defined within the search results.

[0061] For example, an entity is typically identified by determining entity details including at least one of an entity name, entity address and date of birth or incorporation, or the like, depending on the nature of entity. The entity details are then compared to details of existing entities, corresponding to existing identified entities for example in the first representation, with the entity being identified as an existing entity based on the results of the comparison. This process typically involves modifying the entity details in accordance with defined misspellings and phonetic equivalent codes so that modified entity details can be compared to existing entity details thereby preventing matches being overlooked due to misspellings, inconsistent data entry, or the like. To achieve this, the process typically involves determining a distance indicative of a difference between the entity details and the existing entity details and determining an entity to be an existing entity based on the difference. Thus, for example, this can examine a distance between names based on the differences in spelling and then using this to selectively determine whether a match exists.’

57 There are other examples too (see [106]-[107]), some of them quite detailed.

58 There is no express reference to any such process, however, in the claims to the 164 Patent. The Applicants submitted that such a requirement was implicit in claim 1(e). The names given to this process varied. In the end, the Applicants called it entity matching, although another concept, disambiguation, also seemed to be used at times.

59 Professor Grundy thought such a requirement was implicit in claim 1(e):

‘In terms of the matching or disambiguation of deduplication of entities, the claims tell me that information retrieved by the second remote data source query needs to be compared with existing entity information from the first remote data source query, so claim 1E of the 164 patent, to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity.’

60 Under cross-examination on the issue of entity matching and disambiguation he gave this evidence:

‘Mr Catterns: And it’s your position that they are not expressed in the claim, but they’re implied in the claim.

Prof Grundy: They’re implied. Again, I just note for 1 that the claim 1E, 1F and 1 – sorry – claim 3, additional information is kind of slightly more than implied, I would say, so there must be a mechanism of determining that additional information, and, obviously, the body of the claim talks about the mechanisms of that.

Mr Catterns: But the claim doesn’t specify any particular way of achieving it.

Prof Grundy: The claim doesn’t, no.’

61 Professor Takatsuka had a different view. In their joint report, Professor Grundy had expressed the view that disambiguation was required by claim 1(e), a proposition with which Professor Takatsuka did not agree. Neither used the language of entity matching. Under cross-examination, Professor Takatsuka said this about claim 1(e):

‘Mr Shavin: So if you’re to perform the “at least one search” to thereby determine additional information regarding the entity, you have to have matched the entity, don’t you?

Prof Takatsuka: Yes.

Mr Shavin: So that to give effect to the method, built into the requirement in that integer ---

Prof Takatsuka: Yes.

Mr Shavin: ---is to take reasonable steps to make sure you’ve matched the entity. And that will involve de-ambiguation, entity matching de-duplication.

Prof Takatsuka: De-ambiguation doesn’t need to happen. Matching has to happen. Yes.’

62 I take from this that the system needs, as a matter of practical operation, to check to see if the information retrieved about the entity matches the entity about which the query was made (‘entity matching’) but it does not, in order to function, need to work out which of several apparently identical entities is the correct one (i.e. which of three John Smiths is the correct one) (‘disambiguation’).

63 Evidence was also given on this topic by Mr Logeman, the designer of They Rule.

64 I deal with Mr Logeman in more detail below but for present purposes it is useful to note that, in addition to his evidence about They Rule, he is also relevantly an expert in the field. He was asked his views on this topic:

‘And do you also see the phrase “determine additional information regarding the entity”? --- Yes.

The entity there is the user selected entity in 1(c). Is that right? --- Yes

And so the electronic processing device needs to determine that the additional information relates to the same entity as the one previously identified on the network representation? --- Yes

And it might do so using perhaps the phonic code method we went through? --- Yes.

Or it might use another method? --- Yes.

But it must perform that determination? --- Yes.’

65 Mr Logeman’s views were also sought about [8] of the specification which dealt with prior art but I do not see his evidence about what the description of the prior art was driving at helps the Court in construing claim 1(e).

66 I accept in practical terms that any embodiment of the method will need to address the issue of entity matching. If an embodiment of the method does not check to see that the entity retrieved has the same name, then the method simply will not work. I do not accept, however, that this practical matter carries with it any necessity to perform disambiguation (as explained above).

67 But to say that the method will not work without such a step being taken is not to say that such a step has been claimed. For example, a patent for a windscreen wiper might assume the presence of a windscreen and the wiper might be wholly functionless without it, but this would not mean that the windscreen was part of the claims.

68 The short fact is that claim 1(e) does not refer to entity matching or disambiguation. Accepting it assumes the former, it does not as a matter of language claim it. I accept that there are many references to ideas which correspond with entity matching and disambiguation in the specification. However, those do not permit me to expand the meaning of claim 1(e) to include within its terms something which, to my mind, is not there.

69 Accordingly, I do not accept that claim 1(e) requires entity matching or disambiguation.

70 It is also necessary in this context to refer to claim 4 of the 413 Patent which is in these terms:

‘4) A method according to any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the method includes identifying a least one entity by at least one of:

a) determining entity details from the search results data, the entity details including at least one of:

i) an entity name;

ii) an entity address; and

iii) date of birth;

b) comparing the entity details to existing entity details for existing identified entities; and,

c) determining if the entity is one of the existing entities based on the results of the comparison.’

71 One’s initial impression of claim 4 is that it does involve entity matching. However, the Respondent submitted that the words ‘at least one of’ in claim 4(a) impacted on the correctness of that conclusion. The argument was that the matching required needed only to be one of name, address or date of birth. It could be of all three but this was not required by claim 4. If this were correct, so the argument ran, what was required (as opposed to what was permitted) was not really entity matching. I accept this submission.

9. ‘Search’ vs. ‘Query’

72 The experts were as one in thinking that to a person skilled in the art, these meant subtly different things. However, they also all agreed that the Patents failed to observe the difference and used them interchangeably. As such there is nothing to resolve about this.

10. ‘Performing a search includes purchasing a report from a remote data source’

73 This concerns claim 2 of the 164 Patent. Both parties accepted that the purchase had to be from the remote data source. They differed on who was required to request the purchase or to make it. Professor Grundy thought that the user had to decide to make the purchase (rather than the system); Professor Takatsuka thought not.

74 The language of claim 2 accommodates both views. The claim does not specify who must make the purchase and it can be any of the user, the system or both. All that the claim requires is that there is a purchase from the remote data source.

11. ‘Displaying a list or available searches’: Claim 1

75 It is not entirely clear that there was any dispute about this. It is likely that whatever debate there was is linked to the ‘search’ vs. ‘query’ debate which no longer exists. I will record that Professor Grundy and Professor Takatsuka both thought that a ‘search’ in this context included a null search, a proposition with which, to the extent that it matters, I agree.

III Novelty – Prior Art

1. Prior Art

76 By the time of closing submissions the Respondent relied on only two items of prior art as anticipating the Patents:

(i) the version of the search visualisation tool known as They Rule which since 2010 has been publicly available and accessible on the Internet without charge at www.theyrule.net;

(ii) They Rule read together with a United States Patent Application entitled ‘System, Method and Computer Program Product for Identifying and Displaying Inter-Relationships between Corporate Directors and Boards’, publication number US 2004/0215648 A1 (‘Marshall’).

2. Principles

77 There was no dispute that the reverse infringement test explained in Meyers Taylor Pty Limited v Vicarr Industries Limited [1977] HCA 19; 137 CLR 228 at 235 was to be applied. For the prior public publication to constitute an invalidating anticipation it must as a single prior art reference disclose each and every element of the claim. Nor is it sufficient that a prior publication contains a direction which is capable of being carried out in a manner which would infringe. Rather the prior publication must contain clear and unmistakeable directions to do what the patentee claims to have invented: General Tire & Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485-6.

78 So far as reading They Rule and Marshall together, the relevant principle is set out in s 7(1)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’) which provides that:

‘…an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of…prior art information…made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art would treat them as a single source of that information…’

79 So there needs to be a ‘relationship’ between They Rule and Marshall. Whether there is such a relationship depends very much on the circumstances of the case: Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 91 ALR 513 (‘Nicaro’) at 538 per Gummow J (Jenkinson J agreeing at 523). Nicaro at 538-539 establishes that the following matters may be relevant:

the nature of the art involved; and

the degree of connection stated in the document to exist.

80 Mere identification of prior patents will not usually suffice. Sometimes a reference to prior material will show that there is no link; sometimes, it will show the opposite. Context is all.

3. They Rule

81 They Rule was created in 2010 by Mr Logeman as an update of earlier versions of They Rule. It has the capacity to search a single third party data source called ‘LittleSis’. It also has the capacity to formulate a query on a third party site (for example, it can open a window at google.com and prepopulate the search field). But the ensuing search is done by Google and the results are returned on a Google page and not within They Rule. This is not, therefore, a method whereby They Rule conducts a search of some other data source to determine ‘additional information regarding the entity’. They Rule does not obtain any information from such searches. It does not, as claim 1(f) requires, cause the results of searches to be presented to the user. It is Google or the relevant third party site which does that. In this regard I agree with Professor Grundy and disagree with Professor Takatsuka. Consequently, They Rule does not have the capacity, in the relevant sense, to search more than one data source which is what claim 1(e) requires. Consequently, They Rule does not anticipate claim 1 of the 164 Patent or any of the other claims all of which are dependent in various ways on claim 1 or contain an equivalent to claim 1(e). The same is true of the 413 Patent.

4. They Rule and Marshall

82 I make the assumption in the Respondent’s favour, that They Rule and Marshall should be read together for the purposes of s 7(5)(b) because of the reference at [6] in Marshall to www.theyrule.net as an aspect of the prior art; and, secondly, that the temporal aspects of assessing disclosure are all resolved in the Respondent’s favour too. Even so, Marshall is of no use to the Respondent on anticipation. Marshall does not disclose an invention with the capacity to interrogate more than one data source. Most of the debate between Professors Grundy and Takatsuka on this topic related to the issue of whether the data source in Marshall needed to be remote. For the reasons I have given already, that is no longer a material inquiry.

83 Professor Grundy was of the view that Marshall involved only one data source. He drew attention to Marshall at [30] (‘access and process data stored in a database in accordance with the user input…’), [33] (‘The server side components include a webserver 204, an application server 206, a database server 208 and a database 210’) and [36] (‘Database 210 is accessed via database server 208’). To these I would add that the claims of Marshall refer to a single database.

84 Professor Takatsuka dealt with this briefly, perhaps only glancingly, in a discussion which was really directed to the issue of remoteness. He said this:

‘I understand this to mean that the data source from which data is accessed and processed can be, and in some implementations is, “remote” to the computer running the software for generating a network representation. Further, as I note in paragraph 106 above, Marshall suggests that relevant data sources will include SEC filings and news sites. In most cases, these data sources would be remote data sources (operated by third parties) because they are ordinarily accessed over a network like the Internet. However, it could also include a database operated by the provider of the network visualisation that is accessed by the system server over a network.’

85 It is probably not the case that Professor Takatsuka was intending to say that the fact that Marshall referred to SEC filings and news sites meant that it should be read as involving multiple databases. But if that was intended, I do not think Marshall supports that. The relevant part is [5] in these terms:

‘[005] In order to properly evaluate the effect that such relationships have on a given company or on an industry as a whole, one must first be able to identify them. Often, the information necessary to establish a link between a corporate director and another director or board may be mined from publicly-available sources, such as filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), news stories, or company web-sites Using this information, the interconnections may be identified and mapped out manually on a case-by-case basis. However, when the number of interconnects is large, this becomes an extremely arduous task. Moreover, this arduous task must be repeated each time information is sought for a new corporate director or board.’

86 This is not suggesting that those sources could be the data sources involved. In fact, it is saying that accessing those data sources would be unwieldy. In any event, Professor Takatsuka agreed under cross-examination that Marshall involved only one database:

‘Mr Shavin: Yes. But I’m trying to ask you a specific question, if you can follow me. The question is, is the search query being applied to one database, 210, or to one of a number of data bases, of which 201 is only one.

Prof Takatsuka: Description says one database.

Mr Shavin: Yes. Thank you. And I’m doing that without wanting to re-run the argument as to whether the database is remote or is local.

Prof Takatsuka: Sure.’

87 The experts, therefore, agree that Marshall is concerned with a system operating on a single data source. It does not disclose an invention with the capacity to search more than one data source as the 164 and 413 Patents do.

5. Conclusion

88 Neither the 164 Patent nor the 413 Patent was anticipated by They Rule with or without Marshall.

IV Novelty- Self Anticipation

1. Prior Use

89 An invention is taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of prior art information made publicly available through doing a single act: s 7(1)(a). The Respondent relied on two sets of acts:

(a) the showing of a video called the Encompass Video to participants in customer trials conducted by a firm called Veda between 28 June 2011 and 24 August 2011; and

(b) making the Encompass Video publicly available on a video hosting platform ‘Vzaar’.

2. Principles

90 In establishing an anticipatory prior use ‘[t]he question is whether an act can be identified that did in fact make the information being the integers of invention publicly available’: Damorgold Pty Ltd v JAI Products Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 31; 229 FCR 68 at 72 [11]-[12] per Bennett J. The Applicants accepted that the Encompass Video, which I will shortly explain, ‘anticipates the integers of the claims’. However, the Applicants also submitted that a person skilled in the art would not have been able to conduct the methodology revealed in the Patents. I do not accept this submission. As Ms Cochrane, junior counsel for the Respondent, succinctly put it: with these Patents, to see them is to know them. Although the video was a mock-up it revealed all that was claimed in the Patents. Whilst it did not reveal information about how the platform was working, such as entity matching and the generation of network diagrams, these were not the subject of the claims. What was claimed was a method (and in one instance an apparatus). That method was revealed by the video. To see it is, indeed, to know it. A person skilled in the art would in my view be enabled by the video to perceive, to understand and to be able practically to apply the discovery: Insta Image Pty Ltd v KD Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 139; 78 IPR 20 (‘Insta Image’) at 44 [124].

91 Accepting then that the video sufficiently discloses the integers, the question then is whether the disclosure of the video in the ways alleged made it publicly available within the meaning of s 7(1)(c). For that to be so it is necessary to show that the information became available to at least one member of the public who, in that capacity, was free in law and equity to make use of it: Insta Image at 44 [124]. This is the question to be addressed.

3. The Encompass Video

92 The evidence about this was principally given by Mr Wayne Johnson who was the co-founder of Encompass and is its Chief Executive Officer. There is one aspect of Mr Johnson’s evidence about which I have concluded he was not reliable, namely, a topic concerned with passwords. I deal with this below. My impression of his evidence, more generally, was that by and large most of his evidence was true but that he had a tendency, perhaps through excessive enthusiasm for a cause genuinely believed in, to give an account strongly favourable to Encompass. I deal with that aspect of his evidence below at [118] below. That said, and subject to the issue of passwords, I accept the broad thrust of his evidence. Where his evidence it is uncorroborated by other witnesses or documents it does need to be approached carefully.

93 Mr Johnson conceived the idea that would become the Encompass Platform in October 2010. At that time, Encompass was called Portland Analytics and was, in effect, a start-up. The only other person working with Mr Johnson was a Mr Carson and they worked out of a single office with a shared desk. Early on they decided that they needed a project partner, preferably an information broker. The first information broker they approached was Veda Advantage Ltd. Mr Johnson says that at that time he was concerned about maintaining confidentiality which is corroborated by events shortly to be described. I accept Mr Johnson’s evidence about this.

94 One difficulty that Mr Johnson had at this time was that although he had the idea for Encompass, the reality of the platform did not yet exist and, if he were to approach Veda, he needed to have something more substantial than a mere idea. He decided, therefore, to create a video of what the product would look like. Mr Johnson’s initial account of how the video was created could, I agree, have been more fulsome but I do not think he was seeking to mislead the Court about its essentials. By the end of his cross-examination the evidence showed that he and a Mr Green created the video together. Mr Green had by then (that is November 2010) been hired as Encompass’s only other employee. In subsequent documents Mr Green was described as the ‘Principal Architect’.

95 Mr Johnson denied that Mr Green had skills in coding but contemporaneous emails suggest he had some skills in that area. However, this does not seem to me to matter very much nor to be very surprising. What Mr Green was good at was the utilisation of a piece of visualisation software called i2 which was originally marketed by IBM. i2 can be used to create network representations of the kind which the Encompass platform ultimately used. Mr Green used i2 to create something which looked quite like, but was not identical with, the final form of the Encompass Platform. To do this Mr Johnson and Mr Green did searches on the ASIC and Land Titles Office registries to obtain information about some real individuals which were then loaded on to a machine. When the mock up was complete it appeared to allow for searching of the ASIC and Land Titles Office websites and the retrieval of information therefrom. But this was not what was happening. In truth only a small number of entities could be searched, the data was already on the machine and the appearance of searching an external data source was just that, an appearance.

96 An option to pay for these searches was also provided but it, too, of course was a simulation and no payment was taking place. This very limited simulation of the Encompass platform appears to have been in existence in November 2010. Mr Johnson and Mr Green then used it to create the video. This was done by Mr Green operating the system he had created to conduct what appeared to be searches of external data sources. He did so on the pre-selected entities which were the only ones which could be searched. This activity was then captured as a video file. Mr Johnson then used that file to create the video. The video consisted of some fixed slides interspersed with demonstrations of what appeared to be the Encompass platform being used to conduct apparently genuine searches. Over the top Mr Johnson inserted a voice-over.

97 The film was subsequently revised and further edited although not in ways which were suggested to be material. By 1 December 2010 the video was in the form which was tendered at trial.

98 The Applicants accepted that the video disclosed each of the claims in the Patents but not that a person skilled in the art would appreciate how to make the platform. I return to this submission below to reject it. One curiosity is that although the video was a mock-up of the ‘invention’ it nevertheless disclosed the integers. This provided the occasion for some debates between the parties. These included the question of whether the Applicants had ‘used’ the invention in creating the video.

99 One final matter should be noted. The final form of the Encompass platform did not use the i2 software which was ultimately found to be unsuitable for running the actual platform. Indeed, although the video was ready by 1 December 2010 software development for the actual platform did not begin until July 2011 when a programmer, Mr Bing Tan, was retained. In fact, the video suggested the existence of certain features which were not able to be emulated in the final form of the platform (for example, forms could not be retrieved from ASIC).

4. Veda Customer Trials

100 Mr Johnson took the video to a meeting with Veda which was held on 1 December 2010. The purpose of the meeting was to progress a potential partnership with Veda. Veda had the kinds of databases which the Encompass platform would be useful to search. The idea was to show the video to Veda to see if it would be interested.

101 Present at the meeting were Mr Johnson, Mr Carson and a Mr Wilson of Veda. Prior to showing the video to Mr Wilson, Mr Johnson says that Mr Wilson and Mr Carson signed a non-disclosure agreement. I accept this evidence; it would have been pointless to sign it after the video was shown. The non-disclosure agreement was in evidence and is dated 1 December 2010. The agreement had this recital:

‘WHEREAS, in order to facilitate such discussions and analysis, certain confidential and proprietary information, including but not limited to reports, plans, documents, software, source code, data, competitor analysis (collectively referred to herein as “Information”) may be disclosed between the parties orally or in writing.’

102 This was reflected in cl 3:

‘3. That for a period of three (3) years from the date of this agreement, disclosed information unless written consent is otherwise granted by the disclosing party, shall be restricted to those employees and persons in the receiving party’s organisation with a need to know in order to perform service specifically requested by one party or the other in order to fulfil the purpose of this agreement. Such employees or persons shall be notified of the proprietary nature of such information, and the receiving party shall use the same degree of care as it employs with its own Information, but in all events shall use at least a reasonable degree of care.’

103 I accept the Applicants’ submission that cl 3 applied to the video. I reject the Respondent’s argument that the video was not protected by the agreement because it did not have the word ‘confidential’ written on it. That submission was based on cl 2 which was as follows:

‘2. That any and all written information marked by the disclosing party as “Confidential” or “Proprietary” shall be treated by the receiving party as secret and confidential.’

104 It is true cl 2 was not engaged; however, this is irrelevant because the situation was actually governed by cl 3. Even if that were not so, it is plain that the video was being shown in circumstances where Veda was subject to an obligation of confidence: Delnorth Pty Ltd v Dura-Post (Aust) Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1225; 78 IPR 463 at 481-482 [76]. Mr Wilson was not shown the video so that he could do what he wanted without restraint. In any event, the matter was governed by cl 3.

105 Mr Wilson then brought in some other Veda employees – Mr Balk and Mr Osborne – and the video was shown a second time. Following this initial meeting further discussions took place between Mr Johnson and a Mr Samatia of Veda. By this stage Veda was seeking to assess how useful the Encompass platform might be to it. Various meetings took place. On 17 May 2011, Veda and Encompass entered into a memorandum of understanding. Under it the parties agreed to perform a joint analysis of the product. Veda wished to show the platform to some of its customers as a trial. In that regard the memorandum said this:

‘The parties have agreed the following:

• To jointly determine the requirements necessary for Veda to deploy Encompass to its customers, as part of a market trial to ultimately test customer uptake and influence on user behaviour (“the Joint Analysis”).

• The Joint Analysis must have regard to:

o Primary customer research with key sales teams and customer groups,

…’

106 On the topic of confidentiality this was said:

‘Veda and Portland confirm that they are bound by the obligations in the Non Disclosure Agreement dated 1st December 2010 (“the NDA”) and that the terms and conditions of this Memorandum of Understanding and all information disclosed pursuant to it (including the Joint Analysis) constituted Confidential Information for the purposes of the NDA, the terms of which are hereby incorporated into this Memorandum of Understanding.’

107 The effect of these provisions was that Veda continued to be obliged to maintain the confidential quality of the video. The parties expressly contemplated that some Veda customers would be exposed to the Encompass product (such as it then was) and this could only be the video. I conclude that Veda was itself obliged to ensure that those of its customers or potential customers to whom the video was shown kept its contents confidential.

108 From 28 June 2011 to 24 August 2011 Veda then conducted interviews with some of its customers (and potential customers). Present at these interviews was an Encompass contractor, Mr Fogarty, and occasionally Mr Johnson. The interviews were conducted, however, by Veda representatives. Mr Fogarty’s role seems to have been to demonstrate the video.

109 The entities which attended the interviews were Toyota Financial Services, Westpac, Macquarie Capital Finance, Victorian Consumer Affairs, Goldman Sachs, Middletons, PPB, Kemps Petersons Victoria and Kemps NSW. Ms Cochrane elicited this evidence from Mr Johnson:

‘And – but it is the fact that none of the lawyers or accountants who were shown the Encompass video during the Veda customer interviews signed a confidentiality or non-disclosure agreement with you? That’s right, isn’t it? --- Not with us.

And you never asked them to do so? --- I asked Veda around the confidentiality agreements. I think that’s in the affidavit where I had discussion with Moses Samaha. And at the time of preparing the MOU I was insistent that the reference be made to the prior existing non-disclosure agreement, also.

But you never asked the lawyer or accountants to sign one with you. That’s right isn’t it? --- I never had any contact with the lawyers, personally, with the lawyers or accountants in that process.

Yes. And then the fact is that you delegated the Veda customer interviews to a Mr Fogarty, who is a former contractor. That’s right, isn’t it?--- Correct.

And you only attended one or two of the meetings with those people? --- That’s correct.’

110 But this evidence does not establish what the relationship between Veda and its invitees was vis-à-vis the question of confidentiality. It is the Respondent as the party alleging anticipation by these interviews to prove that the attendees were free in law and equity to use the contents of the video. But that has not been shown. No witness was called by the Respondent from Veda and neither were any of the customers or potential customers. I do not know what the confidentiality obligations of the customers or potential customers were. Accordingly, the Respondent has failed to discharge its onus of proving what it alleges.

5. Display of the Video at ‘Vzaar’

111 The Respondent submitted that from 24 January 2011 the video was made available from the Vzaar platform. I accept that this has been proved at least from August 2011 but not that it has been demonstrated that the video was shown publicly.

112 As to the first proposition, the evidence establishes that Encompass sought to obtain funding from the Federal Government around August 2011. That application never proceeded but a draft of an initial application was prepared. That draft contains this statement (I have omitted an accompanying screenshot):

‘To date, PRA has developed a video tool illustrating the Encompass product as its primary marketing and demonstration tool. This is illustrated by the following screen shot. The video itself may be viewed at http://vzaar.com/videos/638893.

…

The video was filmed based on commercial software but does not allow any user interaction. It utilises and [sic] real data but this is static. A proof of concept will animate both of these elements for potential customers, allowing them, under appropriate levels of guidance, to access data from sources in which they have a particular interest and knowledge. This will enable potential customers to assess on behalf of their clients: …’

113 I infer that the video was available at http://vzaar.com/videos/638893 at this time.

114 Subsequently, in March 2012 as Encompass sought to raise share capital, it issued a confidential information memorandum to potential investors. At p 10 of that document investors were invited to view the video at a slightly different address: http://vzaar.tv/638893. Again I accept that the video was available at that site.

115 The Respondent, however, did not prove what was at either of these addresses. Neither did the Applicants, it is true, but it was not their case on this issue. I therefore simply do not know whether the site required a log-in or was instead able to be accessed by any member of the public. It was a very easy task for the Respondent to prove this simply by taking me to the site but this was not done. I accept the Applicants could have done this themselves but they did not need to since they did not bear the onus of proof.

116 I am not satisfied that the public could access the video just because it was posted at the Vzaar site.

117 As a footnote to that conclusion I should record that I do not accept Mr Johnson’s evidence that he assiduously ensured that the Vzaar page was password-protected. It became apparent that his evidence was exaggerated on this issue. He referred to the password being provided by email but no such emails were produced. This satisfied me that his evidence about passwords is unreliable but I do not find that he is necessarily lying about it. It could easily be mere exaggeration. Accordingly, I propose to disregard his evidence on this topic. This, however, does not help the Respondent discharge its onus of proof.

118 For completeness, I am aware that Mr Johnston was cross-examined on the information memorandum with some success. It contained a timeline of milestones to be achieved and those of an ungenerous disposition might say that Mr Johnston put Encompass’s achievement of some of these milestones at its very highest, perhaps even higher. Mr Shavin QC put in submissions that Mr Johnston was a ‘salesman’, a submission which I accept. His enthusiasm to get a difficult project off the ground by raising funds and his understandable enthusiasm to win this litigation both led him sometimes to overstate matters. But he was not dishonest. The effect of these observations is that one just needs to approach his evidence with a little care.

119 Lastly, I reject the Respondent’s argument that even if the site were password-protected this did not prove the confidential nature of the access. The submission misconceives the onus of proof. It was for the Respondent to show the nature of the access that was afforded from the Vzaar site. Essentially nothing beyond the existence of the site and Mr Johnson’s exaggerated evidence about the passwords has been shown. That does not show that the video was publicly available.

6. A pleading point

120 Although I have concluded that the Respondent’s anticipation case based on the video should be rejected I should record that I do not accept a further pleading point pursued by the Applicants. This point was that the pleaded use revealed by the video was the use of the Encompass platform. As the evidence showed, however, the video could not be a use of the Encompass platform which did not then exist. It was but a simulation of what the Encompass platform would look like when it was eventually produced.

121 It was then said that the Respondent’s pleaded case must fail. I do not agree. The Applicants’ initial evidence did not reveal that the video did not involve the Encompass platform. This important fact only became clear on the delivery of Mr Johnson’s second affidavit of 9 March 2017. Even then, the whole picture did not emerge until his cross-examination. No objection was taken on a pleading ground to the evidence elicited from Mr Johnson as to how the video was created. It was plain by then what the contest between the parties was. The case was conducted on the basis that it was the video which was the anticipation. It is too late to insist on the pleading when the case has been otherwise conducted. And this is so even when the Applicants insist that the Respondent is to be held to its pleading: Betfair Pty Limited v Racing New South Wales [2010] FCAFC 133; 189 FCR 356 at 374-375 [55]. In any event, the particularised act was the video so the Applicants can never have been in doubt from an evidential perspective of the case they were required to meet.

V. Innovative Step

1. Prior Art

122 An invention is patentable for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, involves an innovative step when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim: s 18(1A)(b)(ii) of the Act. It will be taken to do so unless the invention would, to a person skilled in the relevant art, in light of the general common knowledge as it existed (whether in or out of the patent area), only vary from the kinds of information set out in s 7(5) in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention. Section 7(5) of the Act provides:

‘7 Novelty, inventive step and innovative step

…

(5) For the purposes of subsection (4), the information is of the following kinds:

(a) prior art information made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

(b) prior art information made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art would treat them as a single source of that information.

…’

123 The Respondent submitted that the Patents lack an innovative step in that sense in respect of the following four documents or acts:

(a) They Rule;

(b) Marshall;

(c) Marshall and They Rule read together; and

(d) Gvelesiani.

124 The question in each case will be the same: would it appear to the person skilled in the relevant art in light of the general common knowledge as it existed before the priority date that the invention as claimed in any claim only varies from (a)-(d) in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention?

2. Principles

125 The innovative step requirement is a lower threshold than the inventive step required of a standard patent: Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC [2015] FCAFC 179; 240 FCR 85 at 117 [175] per Kenny and Beach JJ (‘Blue Gentian’). Even for an inventive step ‘a scintilla of invention’ suffices: Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] HCA 21; 235 CLR 173 at 195 [52]. For an innovative step, by contrast, what is required is ‘a real or of substance contribution to the working of the invention’; but this does not mean great or weighty: see Blue Gentian at 117 [175]. The concept of the working of the invention requires one to ask whether the variation makes a substantial contribution (in that sense) to the working of the invention as claimed. This does not require, however, proof that the invention would not work without the variation: Blue Gentian at 117 [176].

126 The question of contribution must be assessed across the full scope of the claims: Blue Gentian at 117-118 [176] (per Kenny and Beach JJ, Nicholas J agreeing on this issue at 134 [283]). It is not necessary that the variation could be described as an advantage. Substantial contribution in the requisite sense may still occur even where the variation is neutral (in terms of advantage): Blue Gentian at 118 [178].

3. They Rule

127 In their final submissions the Applicants submitted that the invention as claimed by the Patents differed from They Rule in these features which the latter lacked:

(a) They Rule had no capacity to search multiple remote data searches and could only search LittleSis;

(b) They Rule could not match an entity identified by one data source with an entity identified by another; and

(c) They Rule did not incorporate a purchasing step as was claimed in claim 2 of the 164 Patent and claim 1 of the 413 Patent.

128 I have accepted proposition (a) already. Proposition (b) is, in a sense, a corollary of proposition (a). If only one data source can be searched, entity matching does not arise. However, as I have explained above I do not accept that entity matching is part of the claims made by the Patents. I do not accept, therefore, that proposition (b) is a variation between They Rule and the invention as claimed in the Patents. I accept, on the other hand, that the purchasing step in claim 2 of the 164 Patent and claim 1 of the 413 Patent is not part of They Rule and hence is a variation.

129 The first question is whether the variation I accept in [127(a)] above contributes substantially to the working of the invention. Neither Professor Grundy nor Professor Takatsuka thought, in their joint report, that the capacity to search multiple remote data sources involved a substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

130 However, Professor Grundy subsequently changed his view. In a set of slides he prepared prior to giving his evidence he said that in the joint report he had failed to consider the invention as a whole but had just examined the matter integer by integer (this approach is consistent with the statement in Blue Gentian at 118 [176] that the ‘full scope of the claim must be considered’). He now said:

‘However, on reflection the use of this visualized network does in fact make a substantial contribution to the working of the invention as a whole in claims 1, 2 and 3.’

131 However, that does not seem to engage with the question of whether the ability to search a multiple remote data sources has such an effect. Rather, it is a statement about the visualized network which is really a different topic.

132 I do not accept, therefore, that the ability to search more than one remote data source involves a substantial contribution to the working of the invention as claimed. I should add for completeness that there was no debate between the parties about the general common knowledge.