FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited [2018] FCA 360

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | H.J. HEINZ COMPANY AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 004 200 319 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter is adjourned for further submissions to a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WHITE J:

[1] | |

[4] | |

[7] | |

[23] | |

[30] | |

[48] | |

[52] | |

[55] | |

[72] | |

Some general observations concerning the pleaded representation | [73] |

[79] | |

Was the Berries Product Healthy Food Representation false or misleading? | [105] |

[105] | |

[116] | |

[132] | |

[140] | |

Is the Berries Product beneficial to the health of children aged 1-3 years? | [148] |

[150] | |

Consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables and healthy eating habits | [178] |

[184] | |

[191] | |

[196] | |

Conclusion on whether the Berries Product is beneficial to the health of toddlers | [232] |

[247] | |

[260] | |

[263] | |

[271] | |

[279] | |

[314] |

1 The respondent, H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited (Heinz), is a well-known manufacturer and supplier of food products. This judgment concern three products in the Heinz “Little Kids” range with the name Shredz which Heinz supplied as appropriate for children in the 1-3 year age group.

2 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the ACCC) alleges that the packaging of each product contravened ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL) (Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CC Act)). It seeks declarations, injunctions, the imposition of civil penalties, publicity orders and compliance program orders in respect of the alleged contraventions.

3 Heinz denies each of the allegations. On the agreement of the parties, the Court ordered that the issues of liability be heard and determined before the issues concerning the relief (other than the declarations) claimed by the ACCC.

4 The three products were “Heinz Little Kids fruit & veg SHREDZ berries apple & veg” (the Berries Product), “Heinz Little Kids fruit & veg SHREDZ peach apple & veg” (the Peach Product) and “Heinz Little Kids fruit & chia SHREDZ strawberry & apple with chia seeds” (the Fruit and Chia Product) (collectively, the Products). They were manufactured in New Zealand by a contractor to Heinz, Taura Natural Ingredients Ltd (Taura). Each Product was a homogenous blend of ingredients derived from fruit and vegetables (save that the Fruit and Chia Product included a small amount (3%) of chia seeds).

5 Heinz had commenced selling the Berries Product and the Peach Product in July 2013 but these proceedings are concerned with the packaging it used in the period between August 2013 and 18 May 2016. Heinz sold the Fruit and Chia Product between January 2016 and 18 May 2016. Heinz informed its customers on 19 May 2016 that there would no further sales of any of the Products and it seemed to be common ground that sales of them had then ceased.

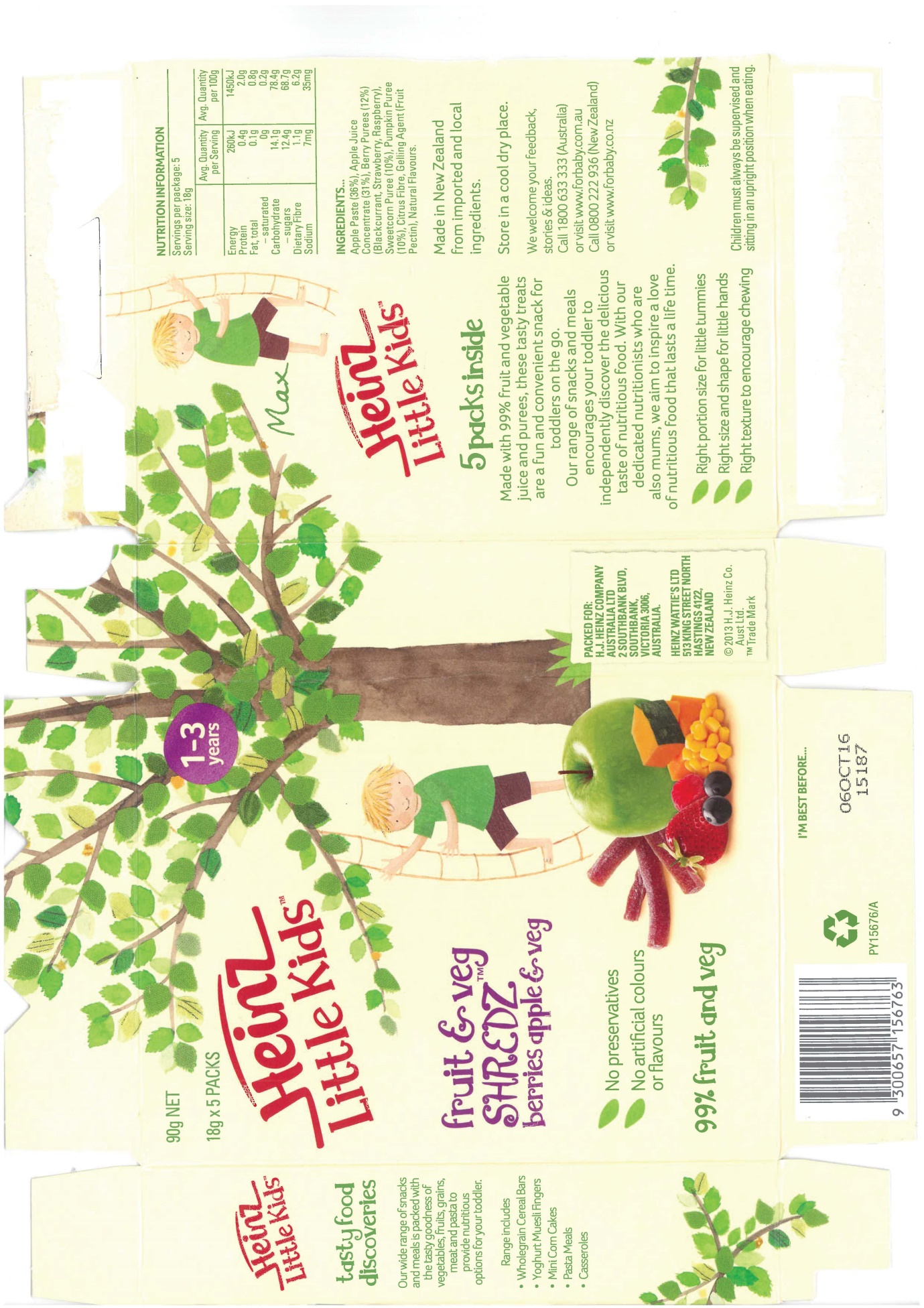

6 Each of the Products was sold in a light cardboard box 145 mm high, 110 mm wide and 30 mm deep. Each box contained five individually wrapped 18 g packets, and each packet contained several sticks of the product (38 mm x 3 mm x 3 mm), which were said by one witness to be similar in texture and taste to confectionery jubes. Several of the witnesses spoke of the Products having a stickiness similar to that of dried fruit.

7 The packaging for each Product was of a generally similar kind. It is convenient to describe first the box for the Berries Product. It had a large stylised picture of a tree on the front. Two stylised images of a smiling boy climbing a rope ladder were on the front and back and, in one case, the ladder was attached to one of the tree’s branches. The picture of the tree continued around the right hand side of the box and continued on the reverse side. At the base of the tree (and on its left) on the front of the box was a coloured photograph of an apple, a strawberry, a raspberry, two blackcurrants, some sweetcorn kernels, and two slices of pumpkin alongside four of the sticks of the Berries Product. The sticks of the Berries Product are at the rear of the photograph with the effect that the depicted fruit and vegetables are more prominent. To the upper left of this picture were the words “Heinz Little Kids™” and underneath that:

fruit & veg

SHREDZ™

berries apple & veg

8 The front of the box contained the words “99% fruit and veg” and above that the words “No preservatives” and “No artificial colours or flavours”. Finally, the front of the box stated prominently “1-3 years”, indicated the product’s weight (90 g net), and indicated that it was made up of five packs each of 18 g.

9 The reverse side of the box contained the following (in smaller fonts than used on the front):

Heinz

Little Kids™

5 packs inside

Made with 99% fruit and vegetable

juice and purees, these tasty treats

are a fun and convenient snack for

toddlers on the go.

Our range of snacks and meals

encourages your toddler to

independently discover the delicious

taste of nutritious food. With our

dedicated nutritionists who are

also mums, we aim to inspire a love

of nutritious food that lasts a life time.

Right portion size for little tummies

Right portion size for little tummies

Right size and shape for little hands

Right size and shape for little hands

Right texture to encourage chewing

Right texture to encourage chewing

10 The reverse side of the box also listed the ingredients of the Berries Product and provided some information in a panel under the heading “Nutrition Information”, to which I will return shortly. The lists of ingredients and of nutrients are required under the Food Standards Code. One side of the box included the following:

Heinz

Little Kids™

tasty food discoveries

Our wide range of snacks

and meals is packed with

the tasty goodness of vegetables, fruits, grains,

meat and pasta to

provide nutritious

options of your toddler.

Range includes

• Wholegrain Cereal Bars

• Yoghurt Muesli Fingers

• Mini Corn Cakes

• Pasta Meals

• Casseroles

11 An unfolded copy of the packaging for the Berries Product is attached as Appendix A to these reasons.

12 The box for the Peach Product was essentially the same, save only that the fruit and vegetables pictured at the foot of the stylised tree on this box were an apple, a slice of peach, some sweetcorn kernels and two slices of pumpkin alongside the four sticks of the Peach Product. To the upper left of this fruit were the words:

fruit & veg

SHREDZ™

peach apple & veg

13 The packaging for the Fruit and Chia Product was in the same style but with some differences. On this box, the items pictured at the foot of the tree were an apple, two strawberries, some chia seeds and four sticks of the Fruit and Chia Product. Immediately to the left of these items was a panel with the heading “Just the Good Stuff …”. At the left hand side of the panel was a stylised icon with the words “No Nasties”, “Naturally Sweet” and “Fruit”. Next to the icon, were three entries:

• No artificial colours, flavours or preservatives

• 99% from fruit ingredients and chia seeds

• Naturally sweetened with fruit ingredients

14 The reverse side of the Fruit and Chia Product box also contained a stylised panel with the heading “Just the Good Stuff …”. This panel contained four icons opposite which were the following entries:

• No artificial colours, flavours or preservatives

• 99% from fruit ingredients and chia seeds

• Naturally sweetened with fruit ingredients

• Finger food for fine motor skill development

15 Unlike the boxes for the Berries Product and the Peach Product, the Fruit and Chia Product box did not contain on its front in free standing form the words “No preservatives” and “No artificial colours or flavours” but, as noted, the words “No artificial flavours or preservatives” comprised the first entry in the panel on the front of the box.

16 The reverse side of the Fruit and Chia Product box did not contain the two descriptive paragraphs under the subheading “5 packs inside” which are included on the boxes for the Berries Product and the Peach Product (see above at [9]).

17 There were some differences in the colours used in the three product boxes. I think it fair to describe the colours on each of the boxes as bright and attractive.

18 The ingredients of the Products listed on the reverse side of the boxes can be summarised as follows:

Ingredients | Berries Product % | Peach Product % | Fruit & Chia Product % |

Apple paste | 36 | 36 | 51 |

Apple juice concentrate | 31 | 34 | 35 |

Berry purees | 12 | - | - |

Sweetcorn puree | 10 | 10 | - |

Pumpkin puree | 10 | 10 | - |

Citrus fibre | % not stated | % not stated | % not stated |

Gelling agent (fruit pectin) | % not stated | % not stated | % not stated |

Natural flavour(s) | % not stated | % not stated | % not stated |

Peach paste | - | 9 | - |

Strawberry puree | - | - | 7 |

Lemon juice concentrate | - | - | % not stated |

Chia seeds | - | - | 3 |

Natural colour extracts (carrot, blackcurrant) | - | - | % not stated |

Total | 99 | 99 | 97 |

19 As noted earlier, the boxes for each Product also contained a panel headed “Nutrition Information”. Each indicated that there were five “servings” per package and that the serving size was 18 g. The “nutrition information” in the panel for each Product can be summarised as follows:

Berries Product | Peach Product | Fruit & Chia Product | ||||

Avg. Quantity per serving | Avg. Quantity per 100g | Avg. Quantity per serving | Avg. Quantity per 100g | Avg. Quantity per serving | Avg. Quantity per 100g | |

Energy | 260kJ | 1,450kJ | 260kJ | 1440kJ | 260kJ | 1430kJ |

Protein | 0.4g | 2.0g | 0.4g | 2.1g | 0.4g | 2.0g |

Fat - Total | 0.1g | 0.8g | 0.1g | 0.8g | 0.4g | 2.1g |

Fat - saturated | 0g | 0.2g | 0g | 0.1g | 0g | 0.3g |

Carbohydrate - sugars | 14.1g 12.4g | 78.4g 68.7g | 14.1g 12.4g | 78.1g 69.1g | 13.3g 12.2g | 74.1g 67.6g |

Dietary Fibre | 1.1g | 6.2g | 1.2g | 6.4g | 1.4g | 7.8g |

Sodium | 7mg | 35mg | 7mg | 35mg | 6mg | 30mg |

20 The evidence from the expert nutritionists, to whom I will refer later, indicates that the required nutrients in food include proteins, fats, carbohydrates, dietary fibre, vitamin A, vitamin C, potassium and magnesium.

21 As can be seen, the nutrition panels indicated that approximately two-thirds of each Product was sugar. However, an analysis carried out in March 2016 at the request of the ACCC solicitors indicated that the Products comprised, respectively, 62-63%, 66% and 62% sugar.

22 The ingredients information and the nutrition information on the boxes were in a relatively small font and, in particular, in a font which was smaller than all the other printing on the front and rear of the boxes.

23 The ACCC pleads that the statements and images on the box of each Product conveyed representations to the effect that the Product:

(a) is of an equivalent nutritional value to the natural fruit and vegetables depicted on the packaging (the Nutritional Value Representation);

(b) is a nutritious food and is beneficial to the health of children aged 1-3 years (the Healthy Food Representation); and/or

(c) encourages the development of healthy eating habits for children aged 1-3 years (the Healthy Habits Representation).

There is one qualification to this summary of the alleged representations. That is that the pleaded Nutritional Value Representation in respect of the Fruit and Chia Product refers only to the natural fruit depicted on the packaging. It was not suggested that this slight difference in form was material to the determination of the issues in the trial.

24 The parties commonly used the term “toddlers” for children aged 1-3 years, and in these reasons I will do likewise.

25 Each of the pleaded representations is alleged to contravene ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

26 Intention is not an element of contraventions of ss 18, 29(1) and 33. It is not necessary for the ACCC to prove that a respondent intended to make false or misleading statements. However, the ACCC alleges that Heinz knew, or ought to have known, that each of the Products was not a nutritious food, nor equivalent to the nutritional value of the fruit and vegetables depicted on the boxes, and that each Product discouraged the development of healthy eating habits in toddlers. The ACCC also alleges that Heinz knew, or ought to have known, that the packaging conveyed the pleaded representations and that those representations were false or misleading. These are serious allegations, attracting in an obvious way, the application of s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). It was the subject of considerable evidence at the trial.

27 I will defer consideration of the ACCC submissions concerning the knowledge of Heinz until after I have made findings concerning the allegations that the pleaded representations were made and that they were false or misleading. In the view I take of the matter, it will not be necessary to make findings concerning some of the evidence bearing on this aspect of the matter.

28 It is pertinent to keep in mind that the issue for the Court’s determination is whether (a) the specific representations alleged by the ACCC were made and, if so, (b) whether they were misleading or deceptive or, in the case of s 33, liable to mislead in the manner pleaded. The Court is not required to determine some of the other issues canvassed in some of the submissions including whether the Products had an inappropriate amount of sugar per se, whether they should be purchased as part of a sensible purchasing decision, whether it would be sensible for a parent or carer to give the Products to their children as an alternative to fruit and vegetables, and whether Heinz could have done more to reduce the sugar content of the Products. Nor is the Court required to consider whether the packaging was misleading or deceptive in other ways which, at times, the ACCC evidence and submissions seemed to suggest, for example, that it was misleading or deceptive for Heinz to describe Products as “fruit and veg” and “99% fruit and veg” rather than “sugarised fruit and vegetables” or “sugary fruit and vegetables” or in some other way to indicate that the Products comprised fruit and vegetables with concentrated sweetness.

29 Further still, the issues in the trial concerning the alleged misleading or deceptive nature of the pleaded representations are not to be resolved by reference to the Healthy Star Rating system being implemented in Australia and New Zealand nor by reference to the Nutrition Profiling Scoring Criterion established under the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code.

The statutory provisions and principles

30 Section 18 of the ACL provides (relevantly):

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

31 Section 29(1) of the ACL provides (relevantly):

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services has sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits …

32 Section 33 of the ACL provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

33 The ACCC alleges that each of the pleaded representations was misleading or deceptive or liable to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) by reason of five features to which I will refer shortly.

34 The ACCC alleges that Heinz contravened s 29(1)(a) by making statements on the Products’ packaging which contained false or misleading representations that the Products were of a “particular … quality, value or composition”, and that it contravened subs 1(g) by making false or misleading representations that the Products had “uses and/or benefits”.

35 The ACCC alleges that Heinz contravened s 33 by making statements on the packages which were liable to mislead the public as to the “nature and/or “characteristics” of the Products and as to “the suitability for their purpose”.

36 By reason of s 224 of the ACL, contraventions of ss 29 and 33 attract a liability to pecuniary penalties.

37 The principles which the Court applies when considering alleged contraventions of s 29(1) and s 33 of the ACL are settled. Section 29 of the ACL is the counterpart to s 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). It was common ground that the case law developed in relation to s 53 may be applied in relation to s 29. It was also common ground that, despite the slight differences in language between the terms “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” used in s 18 of the ACL and the term “false or misleading” used in s 29(1), the terms have the same meaning: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14], cited with approval by Allsop CJ in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2015) 317 ALR 73 at [40]. It has, however, been held that conduct which is “liable to mislead” (being the term used in s 33) applies to a narrower range of conduct than does conduct which is “likely to mislead or deceive” (being the term used in s 18): Coles Supermarkets at [44] and the cases cited therein. Under s 33, what is required is that there be an actual probability that the public would be misled: Trade Practices Commission v J&R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 339.

38 Provisions such as ss 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL are remedial in character and so should be construed so as to give the fullest relief which the fair meaning of their language would allow: Accounting Systems 2000 (Developments) Pty Ltd v CCH Australia Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 470 at 503; New South Wales Lotteries Corporation Pty Ltd v Kuzmanovski [2011] FCAFC 106, (2011) 195 FCR 234 at [105].

39 A representation will be false if it is contrary to the relevant fact and misleading if it has a tendency to lead into error. The causing of confusion or questioning is insufficient; it is necessary to establish that the ordinary or reasonable consumer is likely to be led into error: Coles Supermarkets at [39].

40 The question of whether conduct, including conduct by way of representations, contravenes ss 29 or 33 of the ACL is one of fact to be determined by an objective consideration in the light of all the relevant surrounding circumstances: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198-9; Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [109].

41 The application of ss 29 and 33 requires the Court to identify the conduct said to be false or misleading or liable to mislead and then to consider separately whether the conduct was false or misleading or liable to mislead: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [89].

42 Consideration of the conduct as a whole in its proper context may require consideration of the type of market, the manner in which the goods or services are sold, the habits and characteristics of purchasers in that market as well as of any relevant disclaimers or explanations: Coles Supermarkets at [41]. It also includes any relevant disclaimers, qualifications or explanations: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty at [49]. When the impugned conduct involves representations to the public at large or to a section of the public, such as prospective retail purchasers of a product or service, regard must be had to the effect of the representations on “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers. The range of persons in such a class may be quite broad and may include the intelligent as well as the less intelligent, and those who are well educated as well as those who are less literate.

43 In many cases, the words and images used in advertising or promotional material are capable of conveying different meanings. In such cases, the question is whether the meaning said to be false or misleading is reasonably open and may be drawn by a significant number of persons to whom the representation was addressed. Thus, in CPA Australia Ltd v Dunn [2007] FCA 1966; (2007) 74 IPR 495 at [28], Weinberg J said:

Statements that are capable of more than one meaning may be misleading or deceptive provided that the meaning for which the applicant contends is one that would be reasonably open, and might be drawn by a significant number of those to whom the representation is made. In the same way, a statement may contain a representation that is implied, rather than express. That is why a statement that is literally true can be misleading or deceptive.

(Citation omitted)

44 In Coles Supermarkets at [46], Allsop CJ quoted with approval the following statement by Hill J in Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 FCR 1 at 50:

Where, as in the present case, the advertisement is capable of more than one meaning, the question of whether the conduct of placing the advertisement in a newspaper is misleading or deceptive conduct must be tested against each meaning which is reasonably open. This is perhaps but another way of saying that the advertisement will be misleading or likely to mislead or deceive if any reasonable interpretation of it would lead a member of the class, who can be expected to read it, into error …

Allsop CJ went on to say at [47], that “if any one or more of the reasonably available different meanings is misleading, the conduct may well be misleading or deceptive, or false and misleading”.

45 Generally speaking, however, the class will not include those who fail to take reasonable care for their own interests: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12, (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [101]-[103]; Coles Supermarkets at [43].

46 In cases in which the conduct and representations are to the public generally and concern simple advertising, the absence of individuals saying that they were misled will usually be of little significance. In such circumstances, the Court can carry out an objective assessment of the advertising and promotional material itself without evidence from individual witnesses: Coles Supermarkets at [45].

47 In assessing advertising material, the “dominant message” of the material will be of crucial importance: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2014] HCA 54, (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [45]; Coles Supermarkets at [47].

The relevant class of purchasers

48 In the present case, Heinz acknowledged that the relevant class of retail purchasers comprised the parents and carers of children aged 1-3 years. It submitted, however, that the class should be confined to those parents and carers shopping for snack foods, as opposed to meals, for children aged 1-3 years. In support of this submission, Heinz referred to the evidence indicating that many of its direct customers were the major retailers and to the evidence that these retailers displayed the Products in the sections of their stores containing children’s food. Ms Rigas (Heinz’s Scientific and Regulatory Affairs Specialist) said that these Heinz products were located in the supermarkets next to “other snacking options”.

49 Heinz submitted that understanding the class in this confined way meant that the “target audience” would understand the Products to be a processed snack product, as distinct from fresh fruit and vegetables. Its submissions did not elaborate the significance of that particular distinction. In my opinion, the “target audience” would have readily understood that the Products were not fresh fruit and vegetables, and instead a processed product.

50 I do not consider that it is realistic to confine the class of purchasers in the way for which Heinz contended. The ordinary reasonable purchaser in a supermarket does not usually undertake a shopping expedition for the purpose only of purchasing snacks. Such purchases are much more commonly made in the course of a more general shopping trip involving the purchase of a range of products and, in particular, foods of different kinds. There may be some stores in which the products are so different that it can be said that representations are made to purchasers of one kind of product only. An example may be a whitegoods store which sells both televisions and refrigerators. It may be natural to understand the “target audience” to which promotional material concerning these products is directed as being the prospective purchasers of each individual product. Such a distinction does not seem apt, however, in the context of a food product presented for sale in a supermarket. Accordingly, I accept the ACCC submission that the relevant class of persons comprises the parents or carers of toddlers who are shopping in a supermarket as part of their weekly or other periodic food shopping.

51 It is not necessary for the ACCC to establish that all persons in this class would have been misled or deceived. The relevant enquiry is whether a significant number or, as it is sometimes put, a “not insignificant number” may have been misled or deceived: Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 181, (2008) 171 FCR 579 at [46] (Tamberlin J); Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 98, (2011) 280 ALR 639 at [209] (Greenwood J, with whom Tracey J agreed).

52 The ACCC led expert evidence from two witnesses, Dr Stanton and Professor Manton. Heinz led expert evidence from three witnesses, Dr Barclay, Associate Professor Lucas and Mr Shrapnel. I will defer assessment of them as witnesses until later in these reasons.

53 Heinz led evidence from five of its employees who were involved to a greater or lesser extent in the development of the Products and the packaging, or at least in matters bearing upon the guidelines concerning the development of both. These were Ms Weaver, Ms Hodson, Ms Russell, Ms Tatt and Ms Rigas. All have qualifications in nutrition and/or dietetics.

54 As will be seen, in the view I take of the matter, issues of the credibility of these witnesses do not loom large in my decision. However, in case it becomes necessary, I indicate now that I considered Ms Tatt and Ms Rigas, and for the most part, Ms Russell, to be honest and reliable witnesses who had gone about their tasks within Heinz in a conscientious manner. I agree with the ACCC that the evidence of Ms Hodson and Ms Weaver was to an extent marked by defensiveness, and an unwillingness to make concessions which they perceived to be contrary to the interest of Heinz. While it is understandable that those who perceive their own performance to be in question in a trial will, to an extent, respond in such a way, I would, had it been necessary to do so, been cautious about accepting as reliable some aspects of their evidence.

The Berries Product Nutritional Value Representation

55 Although the evidence bearing on the ACCC representations in respect of the Products had much in common, it is convenient to consider first the Nutritional Value Representation with respect to the Berries Product.

56 The first issue is whether an ordinary and reasonable reader of the words and images on the packaging would have understood it to convey the nutritional value representation alleged by the ACCC, namely, that the Berries Product “is of an equivalent nutritional value to the natural fruit and vegetables depicted on the packaging”. At the heart of this pleaded representation is the term “equivalent nutritional value”.

57 As already noted, the ACCC does not (and could not) allege that the representation concerning nutritional value was conveyed expressly. It alleges that the representation was conveyed by implication. The ACCC said that the implication arose from the prominent photograph of the fruit and vegetables, the location of the depicted fruit and vegetables next to the picture of the Berries Product, and from the proximity of both to the words “99% fruit and veg”. The ACCC emphasised these words submitting that “if something is 99% of something else, it’s the same as – as good as”.

58 It is established, as noted above, that a representation may be conveyed by words and images. For this reason, the submission by Heinz that the term “nutritional value” does not appear on the box, let alone any term like “equivalent nutritional value”, while obviously correct, does not preclude the alleged representation having been conveyed.

59 Heinz also submitted that the ordinary and reasonable consumer may not even understand the concepts of nutritional value and equivalent nutritional value. Its submission was that an understanding of these concepts required a degree of technical knowledge which could not be expected of the ordinary consumer. This requires a finding as to the sense in which the ordinary and reasonable parents or carers of 1-3 year olds would understand the term “nutrition” and its cognates.

60 It may readily be accepted that the majority of ordinary and reasonable purchasers of toddler foods do not have the same detailed knowledge of matters bearing on the nutrition of a food as do qualified dieticians and nutritionists who have undertaken tertiary study. They may not be able to list the nutrients which are necessary in a healthy diet to which reference was made earlier. However, the ordinary and reasonable consumer does not require the level of knowledge of a qualified nutritionist in order to have an understanding of the concepts of “nutrition”, “nutritional value” and equivalents. In my view, the consumers would understand the terms in a non-technical way, that is, that “nutrition” and “nutritional value” refer to the extent to which a food is nourishing in the sense of being a source of the nutrients which sustain life. Such consumers will understand that some foods are more nutritious than others and many will have a general understanding of the constituents which make food nutritious. Many will be accustomed to making comparisons of different foods.

61 I consider that this submission of Heinz involved an underestimation by it of the capacity of the ordinary and reasonable consumers or potential consumers of its products. I reject its submission to the effect that, because the ordinary and reasonable consumer does not have an understanding of those concepts, the Berries Product packaging cannot be understood as conveying a representation about “nutritional value” or “comparative nutritional value”.

62 Heinz also emphasised that the packaging depicted different fruit and vegetables and, further, fruit and vegetables in different sizes. There were four fruits (apple, strawberry, raspberry and blackcurrant) and two vegetables (pumpkin and sweetcorn). The fruits were whole fruits but the pumpkin consisted of slices and the sweetcorn of some kernels. It pointed out that the depicted sweetcorn could be cooked or uncooked. Heinz submitted that this variety of fruit and vegetables, the differing sizes and the possible difference in the cooked state of the sweetcorn militated against the ordinary consumer having an understanding that it was representing that the Berries Product was of equivalent nutritional value to the depicted fruit and vegetables. The submission (which was seemingly inconsistent with Heinz’s first submission) was that the ordinary and reasonable consumer would understand that the varieties of fruit and vegetables and the difference in their quantities and qualities would, or may well have, differing nutritional values, making it unlikely that the consumer would understand that any representation regarding equivalence was being made in respect of the combination.

63 In part, this submission of Heinz may have been responsive to an ACCC submission that “feeding a packet of Shredz Products to a toddler is a nutritious option which provides the toddler with the equivalent nutritional benefit as portions of the fresh fruit and vegetables depicted on the packaging” (emphasis added).

64 However, I do not regard this Heinz submission as persuasive. It seemed to involve an overly literal view of the ACCC allegation and, in particular, seemed to assume that the ACCC is alleging a representation of exact equivalence. While that is one possible interpretation of the ACCC allegation, I do not regard it as the appropriate understanding. It is more natural to understand the ACCC to be alleging that a representation of generalised equivalence was made. The diversity of the fruit and vegetables and their quantities does not mean that consumers could not have understood Heinz to be making a representation about overall equivalence in a generalised way.

65 Nevertheless, I accept Heinz’s overall submission concerning the Berries Product Nutritional Value Representation. In my opinion, ordinary and reasonable purchasers, or potential purchasers, would not have understood the aspects of the packaging to which the ACCC referred to be conveying a statement about the nutritional value of the Berries Product compared with the nutritional value of the depicted fruit in its raw state, let alone that these values were equivalent. The consumers would, in my opinion, have readily understood that the Berries Product was a processed product and would have understood that a representation was being made that it was derived, at least principally, from the depicted ingredients. They would not have understood the Product to be in the form of fresh fruit and vegetables. The pictures of the sticks of the Berries Product would have confirmed that impression.

66 Contrary to the ACCC submission, the reference to “99% fruit and veg” is not a representation as to the product being a percentage of something else. In its ordinary meaning, it is a representation about the ingredients of the Product. Consumers well understand that the processing of multiple ingredients will change the ingredients. They would not expect that, despite the processing, nutritional equivalence would be preserved. Consumers would not expect Heinz to be making a representation to that effect.

67 Consumers are accustomed to seeing manufactured products promoted with images of wholesome ingredients, without this giving rise to an expectation that the products are equivalent in nutritional value to the depicted ingredients.

68 In these circumstances in particular, I consider it more likely that the ordinary and reasonable consumer would have understood the aspect of the packaging on which the ACCC relies to be conveying a representation that the Berries Product was a composite Product derived from the depicted fruit and vegetables, ie, that it was fruit based as distinct from having some other derivation, and that this gave it a “goodness” like that of the depicted fruit and vegetables. The words “99% fruit and veg” would have added to that understanding of the effect of the packaging. The ordinary and reasonable consumer may well have understood the package to convey a representation that the Product was nutritious in a way which was similar to the way in which fresh fruit and vegetables are nutritious and therefore good for toddlers. However, in my view, such a consumer would not have understood Heinz to be making a representation concerning the comparative nutritional value of the Berries Product, let alone a representation that its nutritional value was “equivalent” to that of the depicted fruit and vegetables.

69 I reach the same conclusion with respect to the packaging of the Peach Product which was, in the respects which are material for present purposes, identical to the packaging of the Berries Product. Although there are some differences in the packaging of the Fruit and Chia Product, the ACCC did not contend that these are material, and so the same conclusion applies in respect of that Product also.

70 As I am not satisfied that the Nutritional Value Representations were made, it is not necessary to consider whether they were false or misleading or liable to mislead. I indicate, however, that had I regarded the Nutritional Value Representations as having been made, I would not have found that the ACCC had established that they were misleading or deceptive.

71 Accordingly, I conclude that the ACCC’s allegations concerning the Nutritional Value Representation fail with respect to all three Products.

The Berries Product Healthy Food Representation

72 The ACCC alleges that the packaging of the Berries Product conveyed a representation that it is a nutritious food and beneficial to the health of children aged 1-3 years. Its case was that the representation was conveyed by the packaging as a whole and, in particular, by the repeated use of the word “nutritious” or its cognates.

Some general observations concerning the pleaded representation

73 As counsel for Heinz noted, the subject matter of this alleged representation is the intrinsic quality of the Berries Product, rather than its quality relative to other foods.

74 The Healthy Food Representation is a form of composite representation involving two distinct concepts: “nutritious food” and “beneficial to the health of children”. Heinz submitted that this meant that the ACCC had to establish that the packaging conveyed both of the pleaded limbs and that, if it failed to establish that either limb was conveyed, the allegation based on the Healthy Food Representation would fail altogether. I accept that submission and reject the ACCC submission that the ordinary reasonable consumer would have understood the two limbs of the pleaded representation as being conveyed disjunctively.

75 Initially, the ACCC submitted that there was very little difference between the concepts of “nutritious food” and “beneficial to the health of children”. There is an obvious overlap between the two concepts as it will commonly (but not always) be the case that a food which is nutritious will also be beneficial to the healthy growth and development in children. However, the ACCC also submitted that, if “nutritious food” is understood as limited to food containing nutrients, the term “beneficial to the health of children” would have a wider meaning.

76 Ultimately, the ACCC submission was that the representation conveyed was that the Berries Product was both nutritious and beneficial to the health of children and that, if the Court accepted that that was so, it would establish falsity by showing that one or other or both limbs was false. Heinz accepted that, if the Court was satisfied that the composite representation was conveyed, the ACCC case would succeed even if it could establish the falsity of only one of the two limbs.

77 Both limbs of the Healthy Food Representation are positive in nature. In particular, the representation that the Berries Product is “beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years” is not to be regarded as synonymous with “not detrimental to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years”. To make out falsity of the second limb, the ACCC need establish only that the Berries Product is not beneficial to the health of these children. It does not have to establish that it is in fact detrimental to their health.

78 A food may be beneficial to the health of those who consume it even if it has some disadvantages. The presence of some undesirable features may not, of itself, mean that the food is not beneficial to consumers’ health.

Was the Healthy Foods Representation conveyed?

79 Apart from the heading to the panel containing the nutrition information, the box of the Berries Product uses the word “nutritious” or a cognate four times. None of these usages is on the front of the packaging. The reverse side includes the following:

Our range of snacks and meals encourage your toddler to independently discover the delicious taste of nutritious food. With our dedicated nutritionists who are also mums, we aim to inspire a love of nutritious food that lasts a life time.

(Emphasis added)

One of the side panels states:

Our wide range of snacks and meals is packed with the tasty goodness of vegetables, fruits, grains, meat and pasta to provide nutritious options for your toddler.

(Emphasis added)

80 Heinz noted that each usage of the word “nutritious” or its cognate occurred with reference to the Little Kids range of snacks and meals and not with specific reference to the Berries Product.

81 Heinz submitted that ordinary and reasonable consumers can be expected to read at least the front and reverse sides of the box. I accept that most ordinary reasonable consumers would look at the prominent parts of both sides of the box, but consider it unlikely that this would extend in most cases to the Nutrients and Ingredients panels. That is especially so given that most consumers will be looking at the box in the press of a supermarket aisle. I will refer again to this aspect shortly.

82 Next, Heinz noted that the packaging contains express claims about the Berries Product such as “99% fruit and veg”, “No preservatives”, and “No artificial colours or flavours”. It submitted that ordinary and reasonable consumers would give the greatest weight to these statements, especially as they appear on the front of the packaging and concern the particular Product, in contrast to the statements on the back of the box about the Little Kids range more generally.

83 Thirdly, Heinz submitted that ordinary and reasonable consumers would understand that it intended the Berries Product to be consumed as a snack or as a treat. It relied for this submission on the statement on the front of the box that it contained five packs each of 18 g, the visual depiction of the Product sticks, and the description of the Product on the reverse side as “tasty treats” and “a fun and convenient snack for toddlers on the go”.

84 Fourthly, Heinz submitted that ordinary reasonable consumers would observe and take account of the contents of the Nutrition Information and Ingredients panels. By reading these panels, the ordinary reasonable consumer would understand that a serve of the Berries sticks contained on average 68.7% sugar, that it comprised primarily fruit paste, fruit and vegetable purees, and apple juice concentrate, and that it also contained dietary fibre, protein, fat, sodium and carbohydrates other than sugar.

85 Heinz submitted that, having regard to each of these four matters, the ordinary reasonable consumer would not have understood the word “nutritious” on the back and side of the box as conveying a representation that the Product was “nutritious food and beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years”. Heinz developed this submission by saying:

At most, to the extent that the ordinary or reasonable consumer understands the packaging as conveying anything about the nutritional attributes of the products, it would be no more than that the products were a nutritious snack for children aged 1 to 3, in the sense described on the front of the packaging, namely that:

(a) in relation to the Berries and Vegetables Sticks and Peach and Vegetables Sticks, they are made from 99% fruit and vegetable ingredients and do not contain any preservatives or any artificial colours or flavours, as expressly stated on the front of the packaging; and

(b) …

(Emphasis in the original)

86 In part, this submission seemed to draw a distinction between a representation that an item is a nutritious “food” and a representation that an item is a nutritious “snack”, and suggested that any representation conveyed by the packaging of the Berries Product was of the latter kind only. To the extent that Heinz did seek to make this distinction, I regard it as artificial in the present context. A snack is just one form by which food is consumed. The ordinary reasonable consumer does not regard a snack as being something other than food. Furthermore, it is common experience that many 1-3 year olds consume food by “grazing” in a series of snacks rather than in regular meals. In the description of the Berries Product on the reverse side of the packaging of the Berries Product, Heinz itself did not distinguish between food and snacks. It said that its range of “snacks and meals” encourages toddlers to discover the delicious taste of nutritious “food”. It went onto to say that it sought to inspire a love of nutritious “food” which lasts a lifetime. Further, and in any event, the representation alleged by the ACCC can just as easily be understood as a representation that the Berries Product is a nutritious food, in the form of a snack, and beneficial to the health of toddlers.

87 Heinz also sought to show that the Health Food Representation was not conveyed by reference to the matters upon which the ACCC relies for its claim that the representation was false or misleading, namely, that the Berries Product:

(1) is high in sugar;

(2) has a low moisture content;

(3) has a low satiety value;

(4) is high in kilojoules per gram; and/or

(5) has a sticky texture and is therefore likely to increase the risk of poor dental health in children aged 1-3 years.

It submitted that, because this was the ACCC case on falsity, the ACCC had to establish that the ordinary reasonable consumer would understand the packaging as conveying a representation that the Berries Product was a nutritious food and beneficial to the health of toddlers in the same sense, that is, as representing that it was high in sugar, had a low moisture content and so on. The Heinz submission was as follows:

[The ACCC] seeks to persuade the Court that the ordinary or reasonable consumer would give the terms “nutritious food” and “beneficial to health” a lay meaning, yet seeks to prove that the products were not “nutritious foods and beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years” by expert evidence (principally from an expert nutritionist), who does not apply a lay meaning of these terms but instead refers to issues such as the moisture content and satiety value of the products. There is an obvious difficulty for the ACCC in reconciling its asserted meaning of the terms “nutritious food” and “beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 years” in the first stage of its case with the meaning that it assigns those words in the second stage of its case to attempt to demonstrate falsity.

…

The ACCC cannot do so, particularly in circumstances where the amount of sugar and kilojoules per 100 g in the products were listed on the packaging. The packaging said nothing about moisture content, satiety value or stickiness of the products, or about dental health. There is no plausible basis for a finding that the packaging of any of the products conveyed that the products were nutritious and beneficial to the health of children aged 1 to 3 in the sense pleaded by the ACCC.

88 In my opinion, this particular submission is without merit. The manner by which a representation may be proved to be false does not control the content or meaning of the representation. There is no reason in logic or principle why the ACCC cannot prove the falsity of a representation concerning the quality of a product by resort to expert evidence concerning features of the product about which the consumer may be unware or have overlooked. It is commonly the case that the features of a product which make representations about it misleading are revealed only by expert investigation or analysis.

89 In my opinion, Heinz’s present submission with reference to the Nutrition Information and Ingredients panels is similar to that which was rejected by the High Court in ACCC v TPG in respect of the less prominent qualification to the offer featured in TPG’s advertisement. The plurality noted, at [47], that there are circumstances in which prospective customers cannot be expected to pay the same close attention to an advertisement which can be expected of judges obliged to scrutinise them for the purposes of legal proceedings. In particular, there are circumstances in which persons absorb only “the general thrust” of the advertisement and that, while the attention given by the ordinary and reasonable person to an advertisement may be perfunctory, it is not to be equated with a failure on the part of the target audience to take reasonable care of the their own interests. Later, the plurality said:

[51] [T]his is not a case where the tendency of TPG’s advertisements to lead consumers into error arose because the target audience might be disposed, independently of TPG’s conduct, to attend closely to some words of the advertisement and ignore the balance. The tendency of TPG’s advertisements to lead consumers into error arose because the advertisements themselves selected some words for emphasis and relegated the balance to relative obscurity. To acknowledge, as the Full Court did, that “many persons will only absorb the general thrust” is to recognise the effectiveness of the selective presentation of information by TPG. The Full Court erred in failing to appreciate the implication of that finding.

[52] It was common ground that when a court is concerned to ascertain the mental impression created by a number of representations conveyed by one communication, it is wrong to attempt to analyse the separate effect of each representation. But in this case, the advertisements were presented to accentuate the attractive aspect of TPG’s invitation relative to the conditions which were less attractive to potential customers. That consumers might absorb only the general thrust or dominant message was not a consequence of selective attention or an unexpected want of sceptical vigilance on their part; rather, it was an unremarkable consequence of TPG’s advertising strategy. In these circumstances, the primary judge was correct to attribute significance to the “dominant message” presented by TPG’s advertisements.

90 As noted earlier, the information in the Nutrition Information and Ingredients panels is in a smaller font that that used for the other printing on the packaging. The other features to which I referred earlier are much more prominent and, in my opinion, more likely to create an impression in the consumer’s mind.

91 In any event, it is ordinary experience that information of this kind is not read or absorbed in any detail at the time of purchasing decision of products of this kind. Such decisions commonly have to be made in a supermarket aisle in the course of a larger shopping expedition and sometimes amidst the press of other children for whom the purchaser is responsible or of other customers. Having regard to these circumstances, it would not be realistic to suppose that the ordinary reasonable consumer reads, let alone absorbs, the information in the Nutrition and Ingredients panels with the level of detail which the Heinz submission supposed.

92 Many of the ordinary and reasonable purchasers of the Berries Product are likely to be similar to the ordinary and reasonable member of the class of prospective purchasers of bread in supermarkets to whom Allsop CJ referred in ACCC v Coles Supermarkets at [43]:

In a context such as the present, the purchasing of a staple such as bread in a supermarket, the ordinary or reasonable person may be intelligent or not, may be well educated or not, will not likely spend any time undertaking an intellectualised process of analysis, will often be shopping for many other items, and will be likely affected by an intuitive sense of attraction rather than by any process of analytical or logical choice.

93 The conclusion that a particular representation was conveyed may be more readily reached when it is made in terms apt to create the particular mental impression in the representee intended by the representor: ACCC v TPG at [55]; Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd v Clipso Electrical Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 60, (2017) 122 IPR 395 at [240]. The ACCC submitted that this principle was applicable in the present case because it was apparent that Heinz had intended, by its packaging of the Berries Product, to create an impression that it was nutritious and healthy in the minds of its potential customers.

94 In support of this submission, the ACCC referred to a number of Heinz’s internal documents. The first was a presentation made to Heinz by The Nielsen Company on 15 June 2012 entitled “Playschool (Little Kids Snacks)”. The Nielsen Company provided the report at a time when Heinz was considering new initiatives under the Heinz Little Kids brand and was seeking to assess their viability. One of the products was “Fruit Chewies”, as the Shredz sticks were then known. At a later time they were given the name “Fruit Juicies”. The Neilsen Company had carried out market research including a survey of potential purchasers. It reported that there was “an opportunity to dial up on health/nutrition” as this was “an important driver for those interested in the range”. By itself, I regard this evidence as being of only slight evidentiary value as there is no express evidence that Heinz expressly adopted or endorsed the recommendation of The Neilsen Company.

95 Next, the ACCC noted that the packaging of the Products had changed following a project undertaken within Heinz entitled “Project Totes” in late 2012 and early 2013. Ms Weaver described Project Totes as a “brand refresh” which involved “looking at the attributes of products and what they represented”. Ms Weaver did not accept that the packaging had been changed so as to promote a message of nutrition and health, asserting that instead Heinz sought to have “fun and convenient and toddler-appropriate packaging”. I regarded that evidence of Ms Weaver as unconvincing, and do not accept it. Heinz’s own document entitled “Project TOTES Update” indicated that part of the image it sought to create for the Little Kids range of products was that they were nutritious and healthy. With reference to the depictions used on the Products, the Project Totes Update identified the tree as symbolising “source of food, nature, healthy growth” and that the overall illustration “communicates essence of toddlerhood – Innocence, Energy, Joy”.

96 Thirdly, the ACCC referred to a Heinz document entitled “Heinz Infant FY14 comms briefing” dated 8 January 2013. This appears to be a Heinz internal briefing which, amongst other things, compared the messages conveyed by contemporaneous packages used for Little Kids Products with the proposed new packaging. It supports the conclusion that Heinz’s intention was to present its Little Kids range as both nutritious and healthy. In relation to the packaging then being used, the document reported under the heading “WHAT’S NOT WORKING”:

• Bright colours dialling up artificiality, sugar and additives

• Small ingredient visual failing to reinforce taste and naturalness

• Girl character lacking meaning, not transporting active, playful, independent essence of toddler life stage

• Product appearance lacking appeal

• Nutritional claims too small

(Emphasis in the original)

97 With respect to the new form of packaging (being of the same style used for the Products) the briefing stated under the heading “WHAT’S WORKING”:

• Tree symbolising strong benefits; natural, health, slow growth, freshness, healthy outdoor lifestyle (aspiring to mums who are fighting to get their kids outside)

• Earthy colouring dialling up organic cues (natural)

• Scene communicating essence of childhood: carefree, energetic, healthy, fun

• Drawing style perceived as sophisticated and warm (detail communicating love and care)

The new pack is emotionally engaging (telling a story) and strongly delivers on natural product benefits …

(Emphasis in the original)

98 In my view, the latter two documents support an inference that the general intention by Heinz with respect to the packaging of the Little Kids products was to promote them as both nutritious and healthy.

99 However, it is not necessary to rely upon Heinz own internal statements regarding the purpose of its packaging. Even a reasonably cursory examination of the packaging indicates that Heinz was promoting the Berries Product as being healthy and nutritious and that ordinary reasonable consumers would have understood that that was so. This is evident from the imagery and colours used as well as from the wording on the packaging.

100 In my opinion, there is no difficulty in concluding that the combination of imagery and words on the packaging conveyed to ordinary reasonable consumers both limbs in the Berries Product Healthy Food Representation. The imagery includes the depictions of an active healthy young boy engaged in tree climbing in conjunction with the prominent pictures of wholesome fresh fruit and vegetables. The tree itself conveys an image of natural and healthy growth. The prominent statements that the Product comprises 99% fruit and vegetables together with the pictures of the fruit and vegetables conjure up impressions of nutritiousness and health. The impression of naturalness and goodness is reinforced by the statement that the fruit and vegetables have not been adulterated by preservatives or artificial colours or flavours. The description of the Berries Product on the reverse side of the packaging under the heading “5 packs inside” reinforces the representation conveyed by the imagery and words on the front the packaging. The first sentence emphasises that the Berries Product comprises 99% fruit and vegetables and that it is appropriate for toddlers “on the go”. This suggests that the Product has the “goodness” needed for active healthy children. Any tendency which the word “treats” may have had to suggest that the Product was a sweet treat (like, say, confectionery) is negated by the reference which follows almost immediately to the Product being a “snack”. In the second sentence, Heinz placed the Product as part of its range of “snacks and meals”. This reinforces the implication that, by eating the Berries Product, toddlers will be consuming a nutritious food. The third sentence conveys Heinz’s aspiration to encourage a love of nutritious food with the implicit representation that the Berries Product is of that kind. The reference to Heinz’s “dedicated nutritionists who are also mums” conveys implicitly that those responsible for the Product know, by both training and practical experience as parents, that the Product is wholesome and nourishing. It lends credibility to the claim that the Product is both nutritious and healthy.

101 The information in the Nutrition Information and Ingredients panels does not detract from this overall impression. I accept that many ordinary reasonable consumers who are interested in providing their children with healthy food would have regard to these panels. But there would be many with the same interest who would respond in a more impressionistic way, especially in the press of the supermarket aisle. In many respects the Ingredients and Nutritional Information panels, especially given their smaller font, are in the nature of the “fine print”. In my view, the eye of ordinary reasonable consumers generally is likely to pass over them and to respond to the dominant message conveyed by the more prominent words and imagery.

102 It follows that I do not accept the submission of Heinz that the packaging conveyed no more than that the Berries Product was a nutritious snack for toddlers in the limited sense that it was derived from fruit and vegetables and did not include preservatives, artificial colours or flavours.

103 Although the view of Heinz’s own employees is not of course decisive, I note that Ms Weaver (Heinz’s Nutrition Specialist for Australia and New Zealand) said that she had thought that the packaging of the Berries Product and of the Peach Product represented that they were “a nutritious food … part of a healthy diet”. Ms Weaver had been involved in the assessment of the claims which could be made of the packaging. Ms Weaver’s evidence was close to an acknowledgement that the packaging contained both limbs of the ACCC’s pleaded Healthy Food Representation, but not exactly so. For completeness, I also note that earlier Ms Weaver had said that while she considered the Berries Product and the Peach Product to be nutritious, she “wouldn’t make the link that they were specifically beneficial to health”.

104 I am satisfied that the packaging of the Berries Product does convey a representation that it is a nutritious food and beneficial for the health of children aged 1-3 years. A not insignificant number (at the least) of ordinary reasonable consumers would have understood it in this way. The ACCC has established both limbs of the composite representation it alleges.

Was the Berries Product Healthy Food Representation false or misleading?

105 As already noted, the ACCC’s pleaded case is that the Berries Product Healthy Food Representation was false or misleading because it:

(a) is high in sugar;

(b) has a low moisture content;

(c) has a low satiety value;

(d) is high in kilojoules per gram; and/or

(e) has a sticky texture and is therefore likely to increase the risk of poor dental health in children aged 1-3 years.

106 Satiety, to which (c) refers, is the feeling of being satisfied by the consumption of food after the initial feeling of fullness subsides. Some foods are rapidly digested and absorbed giving rise of a feeling of hunger relatively soon. Others, including fresh fruit and vegetables, give a feeling of substantial fullness for longer.

107 The kilojoule to which (d) refers is the metric unit of energy. All foods containing protein, fats and carbohydrates (including dietary fibre) contribute energy to the diet of humans. Water does not provide any energy. Energy density is the number of kilojoules per 100 g of a food. Foods with a high water/moisture content have a low energy density, and vice versa. In common parlance, the term “calorie” is often used as the unit of measurement of the energy value of a food. One calorie is equivalent approximately to four kilojoules.

108 The ACCC’s pleading as to falsity did not distinguish between the two limbs of the pleaded representation. The effect, as I understand it, was that the ACCC relied on all of the pleaded matters as a basis for the falsity of each limb. However, as the evidence emerged it became apparent that some matters did not bear on the nutrition of the Products (moisture content, satiety value and texture) whereas those matters did bear on whether the Products were beneficial to the health of toddlers.

109 The ACCC submissions as to falsity raised some matters which went beyond its pleaded case. In particular, it submitted that the Berries Product was an “unnecessary” part of a toddler’s diet because the nutrients it does provide are “amply provided by the fruits and vegetables recommended as essential foods for children – and without the concentration of sugars”. An allegation to that effect (if to be relied upon as a free standing matter) should have been pleaded with appropriate particulars. Such particularisation would have informed an assessment of the matters said to make the representation misleading or deceptive. I accept Heinz’s submission that it may also have led to further evidence had this been part of the ACCC’s pleaded case. That being so, I uphold the Heinz submission that the ACCC should not be able to depart from its pleaded case. Accordingly, I will not include a lack of necessity as a free standing matter supporting the falsity of the Healthy Food Representation.

110 However, that does not mean that the issue of necessity is of no relevance at all. I accept the ACCC submission that it is relevant to consideration of the Heinz submission that the Products are beneficial to the health of toddlers because they are a source of some essential nutrients. The evaluation of that submission involves implicitly consideration of whether the Products provide a source of nutrients which would otherwise be lacking in a child’s diet. To that limited extent, the evidence and submissions bearing on the issue of necessity are relevant.

111 The ACCC also relied on other matters which Heinz submitted were beyond its pleading, namely, the high energy density of the Product and its resemblance to confectionery. I accept the Heinz submission concerning the latter but not the former. As already noted, the energy density of a food is usually expressed as the number of kilojoules per 100 g. It correlates with its fat and water content. The greater the amount of fat the higher the energy density. The lower the water content, the higher the energy density. The ACCC did plead that the Products were high in kilojoules per gram. This was an express pleading concerning energy density. I also observe in this respect that Heinz requested both Dr Barclay and Mr Shrapnel to address the issue of energy density.

112 As will be seen later, I also consider that the ACCC submissions concerning the effect of consumption of the Products on the development of healthy eating habits and, in particular, on consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables, do not relate to matters within its pleaded case of falsity of the Healthy Foods Representation.

113 A particular focus of the ACCC case was on the high sugar content and the lack of dietary fibre. Heinz submitted that concentrated sweetness, to which the ACCC’s expert witness Dr Stanton referred, was not part of the ACCC’s pleaded case. In my view, that submission involves an unduly narrow view of the ACCC plea that the Berries Product is “high in sugar”.

114 The ACCC had not pleaded specifically that the Berries Product lacked or was low in dietary fibre. It submitted, however, that this was a corollary of the high level of sugar. Dr Barclay, to whom I will refer shortly, confirmed the correlation between these elements when he said of the Berries Product, that “overall, the nutrient profile clearly reflects the use of apple juice concentrate in the ingredients, increasing the free sugars content and decreasing the fibre content”. Dr Barclay also explained that the dietary fibre is removed during the processing of concentrating the juice. Accordingly, I consider it appropriate to take account of the low dietary fibre in the sense that it is a corollary of the high sugar but not otherwise.

115 Some of Heinz’s submissions were to the effect that the ACCC case, insofar as it concerned the effect on dental health, was confined to the sticky texture of the Products. In my opinion, that submission also involves an unduly narrow view of the ACCC’s pleading and I do not accept it. There is no reason to suppose that the effect on dental health was not one of the matters to which the issue of high sugar content related.

Nutrition and health benefits: The expert witnesses

116 In relation to the nutritional value and health benefits of the Products, the ACCC led expert evidence from Dr Rosemary Stanton. Dr Stanton is a well-qualified nutritionist with considerable experience. In addition, she has published extensively in the area of nutrition, including authoring a textbook concerning food for children. Between 2008 and 2012, Dr Stanton was a member of the working party established by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to develop the Dietary Guidelines for Australians. She was also a member of the working party of the NHMRC which developed the “Infant Feeding Guidelines for Health Workers”. It is obvious that Dr Stanton is able to speak with authority in the area of diet and nutrition, including the diet and nutrition of children.

117 I considered that Dr Stanton gave her evidence in an appropriate manner. She was careful to expose in her first report a matter which could possibly impact on the Court’s assessment of her independence. I am satisfied that generally I can act on Dr Stanton’s opinions and conclusions.

118 Heinz led evidence from Dr Alan Barclay and Mr Bill Shrapnel. Dr Barclay is a Consultant Dietician. He too is well-qualified and has considerable experience, although not as extensive as that of Dr Stanton. I accept that he has the expertise to express the opinions which he has in the trial.

119 However, for reasons which I will elaborate below, I have less confidence in Dr Barclay’s opinions than I do in Dr Stanton’s. At the general level, I thought that there was a certain amount of argumentativeness in Dr Barclay’s evidence and that at times he had a tendency to shape his evidence so as to favour the position of Heinz as the party calling him.

120 I will refer shortly to assumptions which Dr Barclay made concerning the extent of free sugars in the Products which I consider to be unsound and which seem to have resulted in an underestimation by him of these amounts. Another matter giving rise to my reservations about his evidence appears in the opinion which he expressed concerning the relationship between the intake of free sugars and body weight:

Finally, it is worth noting that the WHO determined that the evidence about the relationship between free sugars intake and body weight is based on “low and moderate quality evidence” (9) and that the systematic review and meta-analysis that underpinned the 2015 Guideline “Sugars intake for adults and children” determined that “Trials in children, which involved recommendations to reduce intake of sugar sweetened foods and beverages, had low participant compliance to dietary advice; these trials showed no overall change in body weight.” (25). In other words, despite popular perception, there is little evidence to support a link between free sugars consumption and body weight in children.

(Emphasis added)

121 The reference (25) given by Dr Barclay in this passage is to Morenga, Mallard and Mann (2013) “Dietary sugars and body weight: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies” BMJ 346:e7492.

122 The passage from that article quoted by Dr Barclay is incomplete. When read in full, a different conclusion emerges. Immediately after the passage quoted by Dr Barclay, the article continued:

However, in relation to intakes of sugar sweetened beverages after one year follow-up in prospective studies, the odds ratio for being overweight or obese increased was 1.55 (1.32 to 1.82) among groups with the highest intake compared with those with the lowest intake. Despite significant heterogeneity in one meta-analysis and potential bias in some trials, sensitivity analyses showed that the trends were consistent and associations remained after these studies were excluded.

(Emphasis added)

123 In the very next paragraph of the article, the authors expressed the following conclusion:

Among free living people involving ad libitum diets, intake of free sugars or sugars sweetened beverages is a determinant of body weight.

(Emphasis added)

124 Later, the authors said, at 7:

The extent to which population based advice to reduce sugars might reduce risk of obesity cannot be extrapolated from the present findings, because few data from the studies lasted longer than ten weeks. However, when considering the rapid weight gain that occurs after an increased intake of sugars, it seems reasonable to conclude that advice relating to sugars intake is a relevant component of a strategy to reduce the high risk of overweight and obesity in most countries.

(Emphasis added)

125 Given these conclusions in the very same article to which Dr Barclay had referred, his statement that “there is little evidence to support a link between free sugars consumption and body weight in children” does not seem appropriate. Dr Barclay’s selective quotation from the article in question was one of the matters which undermined my confidence in his opinions generally.

126 Mr Shrapnel does not have the same academic qualifications as do Dr Stanton and Dr Barclay but he does have extensive experience as consultant nutritionist. It emerged during Mr Shrapnel’s cross-examination that he has a continuing association with the sugar industry in Australia. Mr Shrapnel is a consultant nutritionist providing assistance to the Sugar Research Advisory Service (SRAS) which is funded by Sugar Australia. One of the functions of the SRAS is promoting the dissemination of information about sugars to health professionals, including dieticians. Sugar Australia is an industry body with Australia’s leading sugar refineries as its members. I think it fair to infer that Sugar Australia has an interest in the promotion of sugar consumption or at least avoidance of a decline in consumption. Mr Shrapnel did not disclose these involvements in his written report.

127 These matters gave rise to concerns as to the extent to which Mr Shrapnel was truly independent.

128 These concerns were increased by other matters. In the past, Mr Shrapnel maintained a website with the name “Sceptical Nutritionist”. He was the “Sceptical Nutritionist”. The website contained the following explanation of its purpose:

The Sceptical Nutritionist is my response to the dogma that has found its way into advice about healthy eating. Even well respected scientific organisations and nutritionists now weave ideological view points into advice that is supposed to be evidence-based nutrition.

129 Mr Shrapnel acknowledged that he holds “fairly conservative scientific views” and that he is often seen as a “contrarian”. It seems that Mr Shrapnel insists on rigorous proof before accepting that a cause and effect relationship may exist and that he had a tendency to be sceptical of evidence which, although pointing to the existence of such a relationship, fell short of the standard he considered appropriate.

130 Mr Shrapnel’s general view is that sugar of itself has not been shown to be harmful: it is only when it is taken in excess that it may be so.

131 The mere fact that Mr Shrapnel may hold opinions which are unpopular in the field of nutrition does not of course mean that his views are of no weight. However, I consider that caution is appropriate before acting on Mr Shrapnel’s opinions. He is to an extent a participant in the activities of the sugar industry, which it can be inferred is concerned with the promotion, or at least the defence, of the consumption of sugar. Further, the premises upon which his opinions are based seem to involve questioning of at least some commonly accepted matters.

132 In order to provide a setting for some of the findings which follow, it is necessary to make some findings concerning the process of manufacture of the Berries Product. For this purpose, I rely principally on the material supplied by Heinz in response to a notice issued by the ACCC under s 155 of the CC Act and on a Product Information Form (PIF) dated 17 October 2012.

133 Each of the Products was manufactured for Heinz in New Zealand by Taura. It supplied the PIF to Heinz.

134 In its response to the s 155 notice, Heinz identified the raw materials used by Taura for the Berries Product as apple paste, apple juice concentrate, berry purees, raspberry puree, sweetcorn puree, pumpkin puree and natural flavours. The Heinz response did not specify the means by which the apple juice concentrate was obtained but it is reasonable to infer, and I do, that it resulted from a process of dehydration of natural apple juice. The raspberry puree and some of the strawberry puree (being two of the berry purees identified) were described in the Heinz response as “concentrated” and again I infer that these were obtained by a process which included dehydration. The pumpkin and some of the sweet corn purees were described as “UHT” which is the commonly used acronym for “Ultra Heat Treatment”. This suggests that they too had been subject to a process of dehydration.

135 Although the packaging for the Berries Product indicated that its principal ingredient was apple paste (36%), the PIF provided by Taura indicated that the ingredient was instead “Concentrated apple puree, Ascorbic Acid”. Ms Russell, a senior research and development technologist employed by Heinz, said that it had been a decision by Heinz to call this ingredient a paste rather than a puree. She described the process by which the puree/paste was obtained as the mashing of peeled and cored apples followed by dehydration until the product had the viscosity of a paste. Ascorbic acid was then added to avoid browning of the paste.

136 It was common ground that the effect of the dehydration of the ingredients was to increase the amount of sugar as an overall proportion in the ingredients. Another and related effect was to increase the energy density of the ingredient because, when the moisture is removed, it is the macronutrients containing the calories which remain.

137 In addition to the use of ingredients in concentrated form, Taura’s manufacturing process involved further concentration. Heinz described that process as follows:

Taura uses a patented technology process, URC®, to manufacture the Products. The individual Shredz pieces are produced using a unique rapid concentration process of a homogenous blend of the ingredients … The speed of the concentration process ensures the URC® pieces retain their typical flavour and colour.

(Emphasis added)

138 Taura provided a document setting out the separate steps in this process. This included:

Raw materials are batch blended together. Batches are standardised for Brix and pH. Inline filter screens (CCP1) are used to reduce and eliminate foreign matter.