FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Table of Corrections | |

Para [47], the date “21 October 2014” has been amended to read “21 October 2015” |

ORDERS

First Applicant RIVERSUB PTY LTD (ACN 164 963 544) AS TRUSTEE OF THE TANDON FAMILY TRUST Second Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent MICHAEL ALLOUCHE Second Respondent THE RETAIL GROUP (DARLINGHURST) PTY LTD (ACN 145 281 732) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding stand over to 9.30am on 23 February 2018 for the hearing of any argument in relation to costs and for the making of final orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NICHOLAS J:

1 The first applicant (“Mr Shah”) is the sole director of the second applicant (“Riversub”). Riversub is the corporate trustee of the Tandon Family Trust (“The Tandon Trust”). The first respondent (“Mr Hagemrad”) and the second respondent (“Mr Allouche”) were, at all material times, the directors and shareholders of the third respondent (“RGD”) which is a company now in liquidation. Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche are cousins.

2 The central issue in this case is whether, as Mr Shah alleges, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche fraudulently inflated the sales figures for a Subway franchise (“the Haymarket franchise”) situated at 762 George Street, Haymarket, prior to offering it for sale. The applicants’ claim is based on s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) rather than the tort of deceit but there is no doubt that the statutory cause of action relied upon, at least as the case was developed at the trial, is founded on the proposition that Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche deliberately and dishonestly created fake sales that were included in sales records upon which they knew prospective purchasers would rely.

3 Mr Allouche was not represented at the hearing of the proceeding nor did he give evidence. The applicants were granted leave to proceed against Mr Allouche pursuant to r 30.21 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

4 Leave to proceed against RGD was neither sought nor granted and the applicants’ proceeding against that company remains stayed pursuant to s 471B or the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

5 In December 2009 Mr Shah acquired the right to operate a Subway franchise in McGraths Hill. He acquired the right to operate two other Subway franchises, one in Windsor in June 2011, and the other in Riverstone in October 2013. Mr Shah’s evidence was that he had operated all three Subway stores relatively successfully.

6 In May 2015 Mr Shah was considering the possibility of acquiring another Subway franchise. He made enquiries of a business broker who he knew, Mr Peter Li. Mr Li, or a company with which he was associated, carried on business under the name Nexus Business Broking. He was attempting to sell the Haymarket franchise. The business premises at which the Haymarket franchise was conducted was sub-leased by Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche from a company associated with the franchisor known as Subway Realty Pty Ltd (“Subway Realty”) which had itself acquired a lease of the property in or about October 2013. The franchise agreement between the franchisor, Subway Systems Australia Pty Ltd (“Subway Systems”) is dated 30 October 2008. Subway Systems operated the franchise agreement in Australia pursuant to a licence agreement between it and Doctor’s Associates Inc, a US corporation with its principal office in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. It is not necessary to refer to the terms of the franchise agreement.

7 It is not clear what role RGD played in the operating of the Haymarket franchise. It was not a party to either the franchise agreement or the sub-lease of the premises at which the business was conducted both of which were in Mr Hagemrad’s and Mr Allouche’s names. Further, the income from the business was deposited into one of two bank accounts (“the Westpac accounts”) one of which was in the name of RGD and the other in the name of another company called The Retail Group (CBD) Pty Ltd which became known as Cohort D Pty Ltd (“Cohort D”). Cohort D is also in liquidation.

8 Mr Hagemrad gave evidence that he held 50% of the shares in RGD and that Mr Allouche owned the other 50%. However, Mr Hagemrad also gave evidence that he and Mr Allouche had a “silent partner” by the name of Brett Howland who had a one third interest in the Haymarket franchise. Mr Hagemrad’s evidence indicated that Mr Howland acquired this interest as a result of him having contributed to the costs of the fit-out of the Haymarket franchise store. There was evidence that in excess of $200,000 was spent in fitting out the Haymarket franchise in late 2013 and that Mr Howland paid $100,000 towards this expense.

9 On 5 May 2015 Mr Li forwarded by email to Mr Shah a number of documents. These consisted of what is referred to in the email as “Intro Pack for 762 George Street in Sydney”, a “Combo on from 21/4” [sic] and “WISR with hourly reading”. I will refer to these documents as the “Intro Pack”, “the Combo”, and the “WISR” respectively. “WISR” is shorthand for “Weekly Inventory & Sales Report”.

10 The first page of the “Intro Pack” consisted of a memorandum apparently written by Mr Li which included the following:

The Subway franchise is one of the biggest and most popular franchises in Australia. Capitalising on the health-food craze, it is the leading menu choice for individuals seeking quick, made-to-order, affordable, tasty and nutritious meals that the whole family can enjoy.

This well established Subway Shop is located in the city of Sydney on the popular and busy George Street, Haymarket. Situated next to Central Station, Paddy’s Market, shopping arcades, commercial buildings, entertainment venues and UTS, this well established store is a safe investment for growth and profit. Popular with businessmen and students, the store is opened everyday from breakfast to dinner to meet the demands.

The store is fitted with the latest Subway models so no extra spending on fit-outs is required. Plenty of support and training is provided from the Headquarters.

Boasting an excellent lease term and rent conditions and potential for further growth this is an amazing offer.

• Well-established Subway – store in Sydney’s CBD – George Street, Haymarket

• Located on main street, surrounded by commercial buildings, residential developments, Paddy’s Market, UTS, shopping centres and entertainment venues

• Opened everyday – profitable and easy maintenance (no prior exp needed)

• Large customer base

• Only a year old!

• Excellent lease term and conditions

Asking Price: $580K

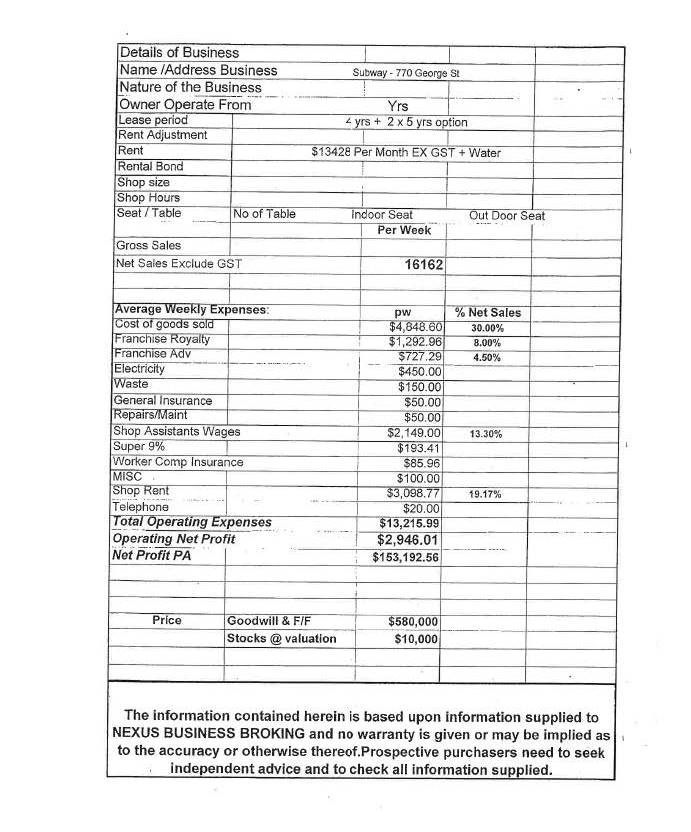

11 The second page of the “Intro Pack” consisted of relevant financial information presented in the form of a table followed by a disclaimer. A copy of the second page is reproduced in schedule A to these reasons.

12 The sales figures in Mr Li’s table includes the figure of $16,162, nett weekly sales. This figure is a gross sales figure representing average weekly takings excluding GST.

13 Mr Li’s table also describes the various average weekly operating expenses totalling $13,215.99 used to derive the nett profit figures. The nett weekly operating profit is shown as $2,946.01 per week and $153,192.56 per annum.

14 The disclaimer appearing immediately below the table states:

The information contained herein is based upon information supplied to NEXUS BUSINESS BROKING and no warranty is given or may be implied as to the accuracy or otherwise thereof. Prospective purchasers need to seek independent advice and to check all information supplied.

15 Mr Shah said in his evidence that he did not read this disclaimer. I doubt this is correct. I think it is more than likely that he did read it but that he did not attribute much significance to it.

16 Although I think it likely that Mr Shah read the disclaimer, in my view nothing at all turns on this. The disclaimer would have assumed more significance had Mr Shah also made a claim against Mr Li or his company. But given the nature of the allegations made against Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche, the fact that Mr Shah read the disclaimer is not something I regard as of any real significance.

17 I should add that although I have not accepted Mr Shah’s evidence on this point, I generally regarded him as an honest witness.

18 There were two Combo Reports that Mr Li supplied to Mr Shah as part of the Intro Pack, the first dated 6 March 2015, and the second dated 24 April 2015. As I will explain, Combo Reports and the WISRs include various sales summaries generated electronically from sales information captured at the point of sale. Subway utilises an automated proprietary system that links sales information complied by a store’s cash register to a computer system at Subway’s headquarters in the United States. This system is used to generate electronic reports, such as Combo Reports, that can then be made available to each of the franchisees. The system provides a means by which the franchisor and the franchisee may keep an accurate and up to date record of sales transactions which can be used to monitor the performance of each store and to calculate royalties payable by the franchisee to the franchisor. Subway franchisees pay a royalty to the franchisor of 8% of sales (exclusive of GST). They also pay an advertising levy equal to 4.5% of sales (exclusive of GST).

19 The Combo Report dated 6 March 2015 included monthly sales information for each of the 2013 and 2014 calendar years and sales information for January and February of the 2015 calendar year. It also included weekly sales and accounting information for the weeks ending 3 February, 10 February, 17 February, 24 February and 3 March 2015. The Combo Report dated 24 April 2015 included monthly sales figures through to March 2015 and weekly sales accounting information for the weeks ending 24 March, 31 March, 7 April, 14 April and 21 April 2015.

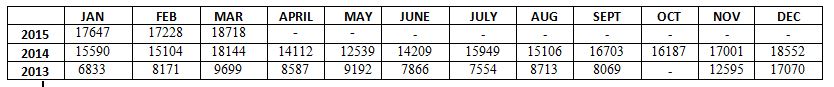

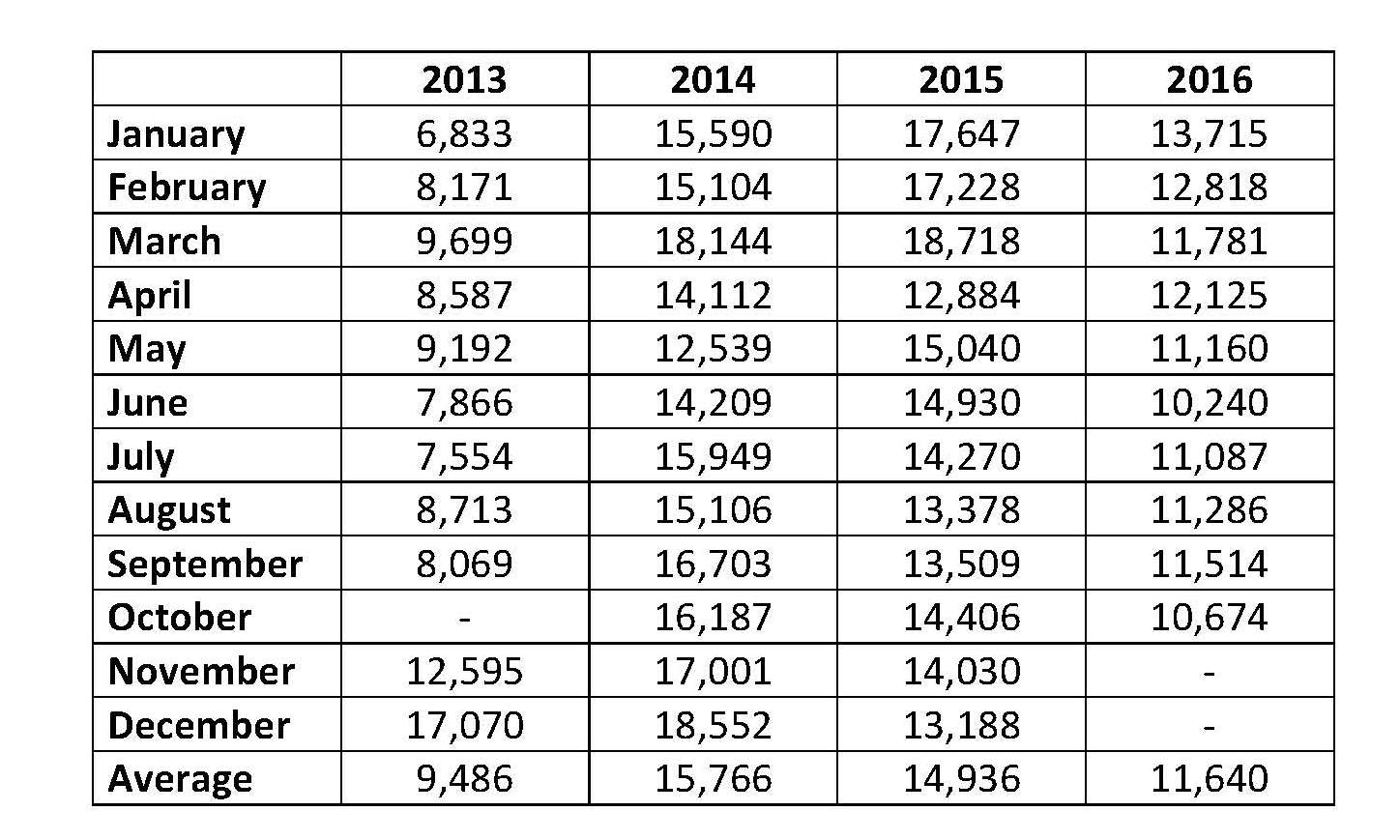

20 The Combo Report dated 24 April 2015 disclosed the following average weekly and monthly sales figures for each month in the period January 2013 to March 2015:

21 Mr Li’s figure of $16,162 for nett weekly sales is the average of weekly sales in the 12 month period April 2014 to March 2015 as shown in the Combo Report.

22 Before committing to purchase the Haymarket franchise, Mr Shah studied the Intro Pack and Combo Reports provided. On two or three occasions Mr Shah and his wife also sat on George Street, across the road from the Haymarket store, between 11am and 2pm to observe the foot-traffic during lunchtime. Mr Shah gave evidence, which I accept, that these investigations did not cause him to believe that the sales figures in the Intro Pack were not genuine.

23 Mr Shah offered to buy the subway Haymarket franchise for $500,000 plus stock to a maximum value of $6,000. In making this offer Mr Shah says that he relied on Mr Li’s average weekly sales figure of $16,162 and the Combo Reports included in the Intro Pack. According to Mr Shah, the main reason he decided to purchase the franchise was the profit and sales; Mr Li’s summary disclosed an annual profit of approximately $150,000 and weekly sales of $16,000 exclusive of GST.

24 There is evidence that suggests that Mr Shah also had access to one or more Combo Reports or WISRs which included average weekly sales for the April, May and June of 2015. The average figure for weekly sales for the period January to June 2015 based on this material was $16,305 per week. That is a slightly higher figure than that appearing in Mr Li’s table but it is one calculated over a 6 month rather than a 12 month period. What is significant for present purposes is that the figure that Mr Shah apparently relied on when deciding to offer to buy the franchise ($16,305 per week) was slightly higher than that appearing in the Intro Pack ($16,162 per week).

25 On 2 June 2015 the solicitors for Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche (Paramonte Legal) forwarded a draft contract of sale to Mr Shah’s solicitors (Lodhia Lawyers). On 5 June 2015 Lodhia Lawyers responded, confirming they acted for the purchaser and seeking various amendments to the contract. None of the proposed amendments (which included some proposed additional warranties to be given by the seller) are of any particular relevance to the issues in the case. However, it is worth noting that Lodhia Lawyers did not seek the inclusion of any warranty in respect of sales or profitability or any amendment to the “entire agreement” provision (cl 2) that was included in the draft contract and the contract ultimately executed by the parties.

26 On 10 June 2015 Paramonte Legal responded to Lodhia Lawyers’ requests for amendments. Some amendments were agreed, but most were not.

27 On 16 June 2015 Lodhia Lawyers wrote to Paramonte Legal outlining that they had been instructed to insist on various further changes. Again, none of these changes are of any particular relevance to the issues in this case.

28 Apparently Mr Shah had some discussions in relation to the draft contract with Mr Hagemrad or Mr Allouche because Paramonte Legal wrote to Lodhia Lawyers on 22 June 2015 advising that the clients had been liaising directly in relation to the amendments that had been proposed.

29 On or about 16 July 2015 the applicants entered into a contract with the respondents for the sale of Subway Haymarket to Mr Shah for a price of $500,000 exclusive of stock to be determined by stocktake on the day of completion to a maximum value of $6,000.

30 RGD is a party to the contract and is identified as a seller in the description of the parties. However, cl 1.1 defines the seller as Mazem Hagemrad and Michael Allouche. Similarly, Mr Shah and Riversub as trustee for the Tandon Trust are also described as the buyer. However, cl 1.1 defines the buyer as Jimitkumar Shah.

31 The evidence did not provide any detailed explanation of the role played by either RGD or Riversub. Although these entities were party to the contract, the evidence indicates that Subway requires that its franchisees be natural persons who own the franchise and lease and occupy the business premises. In any event, I am satisfied that under the terms of the contract, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche were the sellers, and Mr Shah was the purchaser.

32 The following clauses of the contract are of particular relevance:

2. ENTIRE AGREEMENT

(a) The Buyer enters and completes this Agreement solely as a result of its own due diligence, investigations, inquiries and advice.

(b) This Agreement records the entire agreement between the parties as to its subject matter.

(c) Any prior or collateral agreement related to the subject matter of this Agreement is rescinded by this Agreement. The parties release each other from all claims in respect of any prior or collateral agreement.

(d) Any representation not expressly warranted in this Agreement is withdrawn. The parties do not rely upon any representation that is not expressly warranted in this Agreement. The parties release each other from all claims in respect of any representation that is not expressly warranted in this Agreement.

(e) The Buyer will not bring any claim unless it is based solely on and limited to the express provisions of this Agreement.

3. CONDITIONS PRECEDENT

3.1 Conditions

Clauses 6 and 8 do not become binding on the parties and have no force and effect, and Completion cannot occur unless:

(a) The Buyer enters into a franchise agreement with the Franchisor and the Franchisor grants the Buyer unconditional approval;

(b) The Buyer provides the Seller with Written confirmation that the Franchisor:

(i) has agreed to the transaction contemplated in this Agreement; and

(ii) Subway has assigned/transferred the License to the Buyer;

(c) Unconditional approval of the business loan secured by all assets of the business and fixed and floating charge of the company to the extent those assets formed part thereof.

(collectively the “Conditions”)

3.2 Satisfaction of the Conditions

The parties must use all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the Conditions are satisfied as soon as possible and in any event before the Completion Date.

3.3 Notice in relation to satisfaction of the Conditions

Within 1 Business Day after becoming aware of the satisfaction of a Condition, the Buyer must notify the Seller accordingly and provide the Seller with reasonable evidence that the Condition has been satisfied.

3.4 Waiver of Conditions

The Buyer may waive the Condition in its absolute discretion if it provides the Seller with written notice confirming such waiver.

3.5 Date

In the event that the above conditions in Clause 3 are not fulfilled by the time being 180 days from the date of this Agreement, the Buyer is entitled to rescind this Agreement and the Deposit must be refunded in full.

33 Clause 4.1 provided that completion of the contract would take place 14 days after satisfaction of the conditions presented or at such other time as is agreed by the parties in writing.

34 Clause 13.1 provided:

13. PERIOD BEFORE COMPLETION

13.1 Conduct of the Business

Before Completion the Seller must:

(a) conduct the Business in accordance with normal and prudent practice;

(b) use all reasonable efforts to maintain the profitability and value of the Business;

(c) pay the creditors of the Business in the normal course of the Business and in accordance with those creditors’ terms of trade;

(d) use the Assets with reasonable care and maintain the Assets in good repair and working condition up to Completion (fair wear and tear excepted); and

(e) maintain a similar quantity, frequency, style and quality of advertising as was maintained by the Seller immediately before the date of this Agreement.

35 Clause 27 also included the following warranties given by the seller to the buyer:

27. SELLER WARRANTIES

(i) the Seller has full authority and capacity to enter into this Agreement and sell the business;

(ii) the business including chattels, fittings, fixtures and furniture, goodwill, software of the business, licences are not subject to any charge, encumbrance, lease, mortgage or other liability or security unless they are discharged on or prior to completion;

(iii) The equipment is in proper working order;

(iv) There is no subsisting breach by the Seller of a lease, licence, franchise agreement or other agreement with a third party which would entitle the Lessor, Franchisor or a third party to terminate the franchise agreement, licence agreement or any other agreement in connection to the business which would entitle the Lessor, Franchisor or third party to terminate all or any of the abovementioned agreements or refuse to grant an option an option to renew or refuse to transfer the benefit of all or any of the agreement to the Buyer;

(v) The Seller has complied with all requirements under legislation including but not limited to Acts, bylaws, awards, instruments, regulations or rules or conditions of consent relating to the business, licence and franchise;

(vi) There is no current dispute or litigation relating to the business, licence and franchise between the Seller and any other person including lessor, franchisor, supplier of goods or services to the business, current or former employees, council, government departments or accredited certifiers;

(vii) Anything attached to the business sale agreement is accurate;

(viii) There are no workers compensation claims by any employees of the business for the past three years.

Additional Vendor’s Warranty

The Vendor warrants the following:-

i) The seller has fully authority and capacity to enter into this Agreement;

ii) The Company has absolute title to the Business;

iii) The Business is not subject to any charge, encumbrance, mortgage or other liability or security;

iv) The Plant and Equipment of the Business is in proper working order;

v) The Business does not include any stock-in-trade acquired on terms that property in it does not pass until payment has been made;

vi) There is no subsisting breach by the Company of the Lease and Franchise Agreement and any other commercial agreement with third party;

vii) The Company has complied with all requirements under legislation relating to the Business;

viii) There is no current dispute or litigation relating to the Business between the Seller, the Company, the Lessor, the Franchisor or any other person;

ix) Anything attached to this Agreement is accurate and complete;

x) There are no workers compensation claims by any employees of the Business of the past 3 years;

xi) These promises are made as at the date of this Agreement and are also made as at Completion; and

xii) If the seller becomes aware before Completion of any fact which makes a promise in this clause incorrect or misleading, the Seller must disclose the fact to the Buyer before Completion.

The Seller also warrants conducting the Business until Completion and it is an essential provision of this Agreement that the Company must, between the date of this Agreement and Completion:-

(i) Maintain the goodwill of the Business and carry on Business in a proper and Business like way;

(ii) Stay in possession of the Business and the premises, ensuring the Business is run as a going concern;

(iii) Maintain the equipment in the same state of repair as at the contract date (except for any fair wear and tear); and

(iv) Comply with the Lease and Franchise Agreement terms up to and including the date of Completion.

36 Not much appears to have happened in connection with the sale of the franchise between the time of exchange of contracts in July 2015 until October 2015. The evidence suggests that the parties were taking steps to arrange for the franchisor to give its approval to the transfer of the franchise to Mr Shah and that this took several months. In any event, on 11 October 2015 Mr Shah sent an email to Mr Hagemrad requesting a copy of the latest Combo Report and roster. Mr Hagemrad responded the following day providing him with a copy of a Combo Report dated 9 October 2015. It is apparent from Mr Hagemrad’s email that he was expecting settlement to occur in the next couple of days.

37 On 14 October 2015 Mr Hagemrad forwarded further documentation to Mr Shah. This included WISRs for May and June 2015.

38 According to Mr Shah, he examined the Combo Report dated 9 October 2015 and noticed that the sales were down about 10% for the last three months compared to July, August and September. According to the Combo Report, the average weekly sales for the months of June, July, August and September 2015 were $14,930, $14,270, $13,625 and $14,802 respectively. The weekly average for the period January to October 2015 was shown in the Combo Report as $15,450 per week.

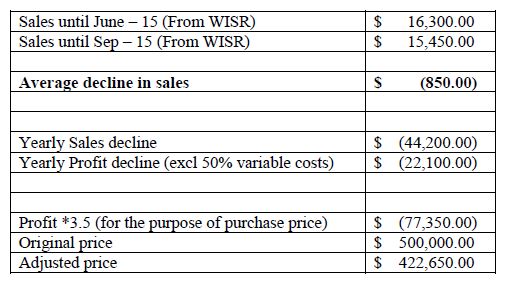

39 On 15 October 2015 Mr Shah contacted Mr Li seeking to negotiate a reduction in the purchase price. In an email to Mr Li, Mr Shah drew attention to the difference between the average weekly sales of $16,305 in a Combo Report dated 5 June 2015 (an extract from which appears in his email to Mr Li) and the Combo Report dated 9 October 2015 which disclosed average weekly sales of $15,540. It is not apparent when Mr Shah obtained access to the Combo Report dated 5 June 2015. Nevertheless, the circumstances in which Mr Shah deployed it when seeking a reduction in the purchase price based on a comparison of these two Combo Reports suggests that he had access to it prior to the exchange of contracts in July 2015. In any event, I do not think anything turns on this.

40 On 14 October 2015 Mr Shah sent the following email to Mr Li:

Hi Peter

I have thought about sales decline and here is my response.

While I understand the reason for decline, I still have to go by what it says on the WISR. Also, I am not keen to investigate on this decline and also it will be hard to believe this week’s sales because if they can do cash sales, then there are chances they can create fake sales as well. So, I will never be able to get accurate numbers.

So, its best that I look at numbers on WISR and work on that.

I am proposing below price reduction. Please let me know what you and Vendors think. If we are unable to reach an agreement then I will have to involve Akash and consider further options.

Thanks

Jimit

“Akash” is a reference to Mr Shah’s solicitor, Mr Lodhia.

41 There are several points to note about this email.

42 First, Mr Shah says that he understands the reason for the decline. I am not certain what it is he was referring to here because he seems to have been given two different explanations for the decline in sales. His evidence was that Mr Allouche told him that some cash sales were not registered and that some cash was being pocketed. However, Mr Shah also accepted that Mr Hagemrad had a conversation with him at around this time in which Mr Hagemrad attributed the decline in sales to the light rail works.

43 Secondly, Mr Shah’s email does suggest that he understood that there was a possibility that Mr Allouche or Mr Hagemrad, in addition to not recording some cash sales, might also “create fake sales as well”. This is a significant remark given the allegations now made by Mr Shah against Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche.

44 Thirdly, Mr Shah made the point to Mr Li that he still had to rely on the WISRs. His email indicates that he used the WISRs to ascertain the decline in sales to which he pointed in seeking a price reduction of $77,350. I take this to mean that Mr Shah believed he had no alternative other than to rely on the WISRs. Mr Shah gave evidence that he thought the revised average weekly sales were between $15,000 and $15,500.

45 The various discussions concerning the decline in sales culminated in a further agreement whereby Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche agreed to accept $40,000 less for their franchise. The evidence does not indicate whether this further agreement was reduced to writing. In any event, it constituted, in substance, a variation to the contract signed in July 2015.

46 As previously mentioned, the settlement of the sale of the franchise occurred on 21 October 2015 from which date Mr Shah took control of the business. At about this time he also took an assignment of Mr Hagemrad’s and Mr Allouche’s sub-lease of the premises.

47 The evidence indicates that on 21 October 2015 $424,651.69 representing the balance of the proceeds of the sale of the Haymarket franchise to Mr Shah was deposited into the Westpac account in the name of Cohort D. The evidence also suggests that two amounts totalling $430,000 were on the following day withdrawn from that account and paid to Mr Allouche and Mr Howland.

48 Mr Shah gave evidence that if he had known before he signed the contract to buy the business that the average sales were between $11,000 and $12,000 per week, then he would not have bought the business. He did not give any evidence as to what he would have done had the average weekly sales been in excess of $12,000.

49 It is important to note that Mr Shah’s case related to the accuracy of the financial documentation upon which he relied. In particular, it is his case, that had he known that the actual takings of the business averaged less than $12,000 over the period that Mr Li calculated his average of $16,162 he would not have bought the business. In short, his case is that he was duped into buying the business by false financial information provided to him by Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche (either directly or through Mr Li) that included fraudulently inflated sales figures.

50 Mr Shah’s case, as it was opened, and as it was developed in the cross examination of Mr Hagemrad, was that beginning in about May or June of 2014, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche caused fake credit sales to be registered in respect of which no cash was ever received. Thus, the case advanced against Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche was, in substance, a case of fraud, in which both Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche willingly participating in a dishonest scheme designed to inflate their sales figures.

51 It is not disputed by Mr Hagemrad that the discrepancies between amounts registered and amounts banked were as shown in Exhibit F, which I discuss in more detail below. However, while Mr Shah claims that these discrepancies were a result of Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche creating fake sales that never generated any revenue, Mr Hagemrad says that all of the so-called fake sales were genuine, but that Mr Allouche wrongly classified these as credit rather than cash sales so that he could pocket the cash that was received.

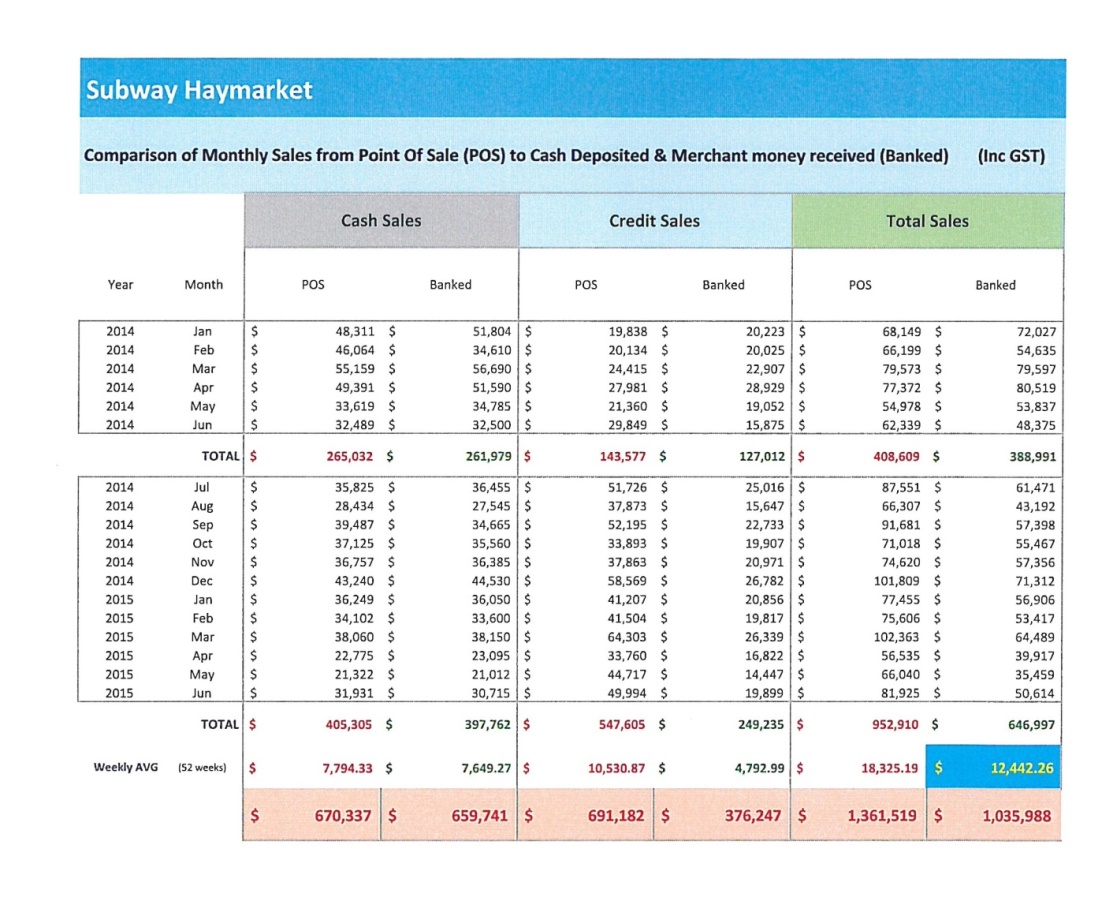

52 In support of his case, Mr Shah points to the differences between the value of the point of sale transactions registered between June 2014 and June 2015 compared to the amount actually banked. The following table (extracted from Exhibit F) shows the difference between the registered point of sales transactions and the amount banked for each of the months from January 2014 to June 2015. It also shows what proportion of the total sales were registered as cash sales and credit sales. Cash sales involved receipt of cash whereas credit sales involve the debiting of a credit or debit card with the proceeds of sale being credited to the Westpac accounts at some later time. The figures are all inclusive of GST.

Table 1

53 It is apparent from this table that the average weekly sales for the fifty two weeks in the period July 2014 to June 2015 were $18,325 whereas the amount actually received into the Westpac accounts for the business over the same period averaged only $12,442 per week. The difference between what was registered in sales over that twelve month period ($952,910) and what was actually received over that period ($646,997) is $305,913.

54 On its face, if one assumes that the amounts actually received by the business were all banked into the relevant accounts, this indicates that recorded sales for the twelve months up to and including June 2015 were approximately $866,282 (exclusive of GST) whereas the actual cash received was approximately $588,179 (exclusive of GST). It would follow that sales for the twelve months through to June 2015 were overstated by approximately $278,103 after allowance is made for GST. Again, on its face, it would appear that the actual sales have been overstated by approximately 30%.

55 Mr Hagemrad’s case is that the actual sales of the business were as reported in the Combo Reports. However, he says that beginning in around June 2014, through until the time the business was transferred to Mr Shah in October 2015, Mr Allouche was removing cash from the business. He did this, according to Mr Hagemrad, by recording some of the cash sales as credit sales and keeping for himself the cash received from those sales. Since the sales that Mr Allouche falsely recorded as credit sales were in fact cash sales, there never was any payment received from a financial service provider in respect of them. Mr Hagemrad says that, in this way, Mr Allouche stole large sums of money from the business which, as outlined above, would appear to have totalled to approximately $300,000 over the twelve month period through to June 2015 and in excess of $400,000 through to the end of September 2015. In his evidence Mr Hagemrad said he believed the amount stolen was in the vicinity of $250,000 – $350,000. To put the scale of this in context, it will be remembered that Mr Li’s figures indicated that the annual profit was about $153,000.

56 The evidence included a Combo Report dated 7 October 2016 (Exhibit 8) which included monthly sales information for the Haymarket franchise for the period January 2012 through to October 2016 which I have extracted below (Table 2). This covers a period when the business was being operated by Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche, and a period when it was being operated by Mr Shah (late October 2015 to October 2016). It does not include any sales figures for the month of October 2013 which is when Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche moved the business from its original premises situated in Oxford Street, Paddington to the new premises in George Street, Haymarket.

Table 2

57 I think the figures for the period January through to October 2013 can be disregarded on the basis that the business was being conducted during that period from different premises. For the same reason I would disregard the average sales figure for the 2013 year. The figure for October 2016 ($10,675) appears to represent sales for only a part of October. Accordingly, the sales figure for October 2016 are likely to be significantly understated.

58 In relation to the period November 2013 to October 2016, there are a number of points to make. First, by my calculation, average weekly sales for the period November 2013 to May 2014 (inclusive) were approximately $15,000. I regard this as quite significant in that it is not suggested by Mr Shah (consistent with the figures appearing in Table 1) that the respondents were during that period engaged in the alleged fraudulent scheme. Secondly, in the same period there were months in which sales exceeded $17,000 (December 2013 and March 2014).

59 In my view, a comparison of the average weekly sales figures for the period November 2013 to May 2014 or June 2014 to the average weekly sales figures for the second half of 2014, does not provide any basis for inferring that the sales figures for the second half of 2014 were artificially inflated as Mr Shah alleges. In fact, the second best month in the 2014 calendar year was March (average $18,144 per week) which was prior to the commencement of the alleged fraudulent scheme and only slightly less than the highest figure achieved that year in December (average $18,552 per week).

60 In his evidence Mr Shah made the point that it is not appropriate to look at results achieved in individual months, and that it is necessary to look at sales on an annual basis. There is some force in this observation. However, I do not accept that it is not useful to look at average weekly figures for individual months especially when assessing the capacity of the business to generate revenue or when looking at the extent to which revenue was liable to fluctuate from month to month. Thus, in December 2013 and March 2014 (before the alleged fake sales are said to have been made) the business showed that it was capable of generating more than $17,000 in a single month, a figure that was never achieved after Mr Shah took charge of the business.

61 The principal evidence to which Mr Shah points to in support of his case are the discrepancies between the sales recorded in the Combo Reports and banking records referred to in Table 1 and the sales he achieved in the period November 2015 to October 2016 as disclosed in Table 2. It is not suggested that the sales reported by Mr Shah during the period November 2015 to October 2016 are anything but accurate.

62 The evidence does not include any analysis of the costs of goods sold with a view to demonstrating that a substantial percentage (approximately 30%) of the sales disclosed in the Combo Reports were likely to be fake. This is an area where expert evidence might well have revealed whether the costs of goods sold were at levels consistent with the creation of a substantial number of fake sales.

63 On Mr Shah’s case, Mr Allouche (in collaboration with Mr Hagemrad) created large numbers of fake sales with a view to obtaining a higher price for the Haymarket franchise. On Mr Hagemrad’s case, Mr Allouche stole large sums of money from the business over an extended period (somewhere between 12 and 18 months). In the absence of any evidence from Mr Allouche (who, as I have mentioned, was not represented at the hearing) that provides any alternative explanation for the differences between the level of recorded sales and the payments received into the Westpac accounts, I am satisfied that either Mr Shah or Mr Hagemrad must be correct. Either Mr Allouche engaged in acts of dishonesty of a serious kind that involved stealing large sums of money from the business that he operated with Mr Hagemrad or he participated in a dishonest scheme with Mr Hagemrad to inflate the sales figures by recording fake sales that made the business appear more profitable than it actually was.

64 Mr Wood, who appeared for Mr Hagemrad, placed reliance on the well-known principles discussed in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336. In Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd (1992) 110 ALR 449, Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ said at 449-450:

The ordinary standard of proof required of a party who bears the onus in civil litigation in this country is proof on the balance of probabilities. That remains so even where the matter to be proved involves criminal conduct or fraud. On the other hand, the strength of the evidence necessary to establish a fact or facts on the balance of probabilities may vary according to the nature of what it is sought to prove. Thus, authoritative statements have often been made to the effect that clear or cogent or strict proof is necessary “where so serious a matter as fraud is to be found”. Statements to that effect should not, however, be understood as directed to the standard of proof. Rather, they should be understood as merely reflecting a conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct and a judicial approach that a court should not lightly make a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, a party to civil litigation has been guilty of such conduct. As Dixon J commented in Briginshaw v Briginshaw:

The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved …

There are, however, circumstances in which generalisations about the need for clear and cogent evidence to prove matters of the gravity of fraud or crime are, even when understood as not directed to the standard of proof, likely to be unhelpful and even misleading. In our view, it was so in the present case.

(footnotes omitted)

65 Their Honours noted that both the plaintiff and the defendants in that case were alleged to have falsified the sales records of a business that the plaintiff (Neat Holdings) purchased from the first respondent (Karajan). Their Honours said at 451:

In that context, as the learned trial judge said, “the real issue in [the] case boil[ed] down to who is telling the truth about the turnover”. In other words, the real issue in the case was not whether there had been deliberate falsification of the takings of the business. It was whether the deliberate falsification of takings figures had been on the part of the respondents or on the part of Neat Holdings. When an issue falls for determination on the balance of probabilities and the determination depends on a choice between competing and mutually inconsistent allegations of fraudulent conduct, generalisations about the need for clear and cogent proof are likely to be at best unhelpful and at worst misleading. If such generalisations were to affect the proof required of the party bearing the onus of proving the issue, the issue would be determined not on the balance of probabilities but by an unbalanced standard. The most that can validly be said in such a case is that the trial judge should be conscious of the gravity of the allegations made on both sides when reaching his or her conclusion. Ultimately, however, it remains incumbent upon the trial judge to determine the issue by reference to the balance of probabilities.

66 It is not suggested in the present case that Mr Shah has understated sales he made at the Haymarket franchise. So the forensic contest is not quite the same as that with which the High Court was concerned. Nevertheless, in the present case both Mr Shah and Mr Hagemrad allege that they are the victims of fraud, on Mr Shah’s case, by Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche, and, on Mr Hagemrad’s case, by Mr Allouche alone. In those circumstances, I think that the High Court’s observations at 451 are apposite. Accordingly, I approach this case on the basis Mr Shah is required to prove his case on the balance of probabilities, conscious of the gravity of the allegations made against Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche but also conscious of the gravity of allegations made by Mr Hagemrad against Mr Allouche. Of course, I am mindful that the evidence given by Mr Hagemrad was not contradicted by any evidence from Mr Allouche.

67 Mr Wood pointed to some evidence to suggest that the relevant decline in sales may be attributable to various factors including (i) the relocation of a bus stop near the Haymarket franchise, (ii) light rail works in George Street, (iii) the removal of outdoor seating, and (iv) failing to take advantage of catering opportunities.

68 Mr Hagemrad gave evidence that there was a bus stop situated near the Haymarket franchise, about 40 or 50 metres away on the same side of the road. I accept that evidence. I also accept that the bus stop was moved in October 2015 along with other bus stops along George Street which were relocated onto other streets when the buses routes were changed to make way for the light rail works.

69 Mr Hagemrad also gave evidence that he had a conversation with Mr Shah concerning the bus stop but that he could not recall the details of that conversation or when it occurred. He said he mentioned the importance of the bus stop to Mr Hagemrad during this conversation. It was not put to Mr Shah in cross-examination that he had any such conversation with Mr Hagemrad and, in those circumstances, I am not inclined to accept Mr Hagemrad’s evidence that he had any conversation with Mr Shah about the bus stop. Nevertheless, I am satisfied that the bus stop made a positive contribution to the operation of the Haymarket franchise in terms of pedestrian traffic and store visibility.

70 Mr Shah was quick to point out that the bus stop was removed in October 2015 whereas sales began to decrease in about June 2015. This is not quite right because sales in June 2015 were actually higher than they were in June 2014. However, I accept that between July 2015 and October 2015 sales were significantly lower than what they had been in those months in 2014.

71 As I have explained, the evidence indicates that Mr Hagemrad told Mr Allouche in October 2015 that there had been a decline in sales as a result of the “Sydney Light Rail” project. In July 2015 the consortium responsible for the design and construction of the Sydney Light Rail project issued notices to residents and businesses that were to be affected by work that the consortium planned to carry out between July and September 2015. The work was described as “investigation works in the CBD – 17 July to 17 September 2015 (Day and night time work)”. Details of the proposed work and its impact was described in these terms:

Details of work activities

Survey works - involves paint marking the road surface and opening a small number of service access lids to record existing buried utilities. Works will also include surveying roadways and footpaths with hand held equipment.

Geotechnical investigations - includes drilling and excavating the road surface and footpaths to establish existing ground conditions and characteristics.

Potholing works - involves excavation of the road surface and footpaths to identify existing services; followed by reinstatement of the area.

Equipment and vehicles for this work may include radar detection and survey equipment, flood lights, vacuum excavation trucks, coring and drilling machines, saw cutters, road grinders, water carts and traffic control vehicles.

How will it affect me?

You may experience some noise and dust during these works. Every effort will be made to minimise the impact to residents and businesses while work is undertaken and no work will take place on Friday or Saturday nights.

Where required, any dust generating activities will be watered down and vehicles will be switched off when not in use to minimise noise.

Traffic changes and detours

All roads will remain open during these works, with limited localised traffic management in place to assist motorists, pedestrians and cyclists.

Access to buildings, driveways and pedestrian footpaths will be maintained.

72 There was no evidence to indicate that the work described in the July 2015 notice extended beyond October 2015 or that the sales of the Haymarket franchise were impacted by any other work associated with the Sydney Light Rail project at any time up to the date of the trial of the proceeding.

73 Mr Hagemrad said that he had discussions in July 2015 with Mr Shah in which he emphasised the importance of the outdoor seating at the Haymarket franchise. He gave evidence that he told Mr Shah that the outdoor seating (and associated signage) was extremely important for the visibility of the business. He also told Mr Shah that he could not transfer the necessary permit to him and that Mr Shah would need to lodge his own application with council for a permit for the outdoor seating. Mr Hagemrad gave evidence that he went past the Haymarket franchise two or three times in early 2016 and noticed that there was no outside seating. I accept Mr Hagemrad’s evidence on these issues.

74 Mr Shah did not deny these conversations took place and I accept that they did occur. His evidence was that the outdoor setting was used through until sometime in February 2016 when a council officer required that it be removed because Mr Shah had not obtained the necessary permit. Mr Shah said that he obtained a permit in April 2016. Accordingly, I am satisfied that there was no outdoor seating in use at the Haymarket franchise from sometime in February 2016 to sometime in April 2016.

75 Again, there is no expert evidence to indicate what effect the absence of outdoor seating in the period February 2016 to April 2016 may have had on sales. However, it is clear from Table 2 that sales in February and March 2015 averaged between $17,0000 and $19,000 per week and they appear to be two of the three or four busiest months of that year.

76 I am satisfied that the absence of outdoor seating in February, March and April 2016, would have helped to drag down the average weekly sales in the 2016 calendar year. It is not possible for me to quantify the loss of revenue occasioned by the lack of any outdoor seating during those months, but I am satisfied that it is likely to have had a modest adverse impact on the business.

77 There was also some evidence to indicate that Mr Shah may not have followed up on some catering opportunities. In particular, there was some evidence to indicate that Mr Shah failed to pursue leads with a number of customers including World Projects and Travelcorp. The evidence in relation to these matters was scant and I am not satisfied that the decline in revenue that occurred from November to December 2015 and January to September 2016 is explained by any failure on Mr Shah’s part to exploit any of these opportunities.

78 The decline in the sales experienced by the Haymarket franchise must be seen in the light of Mr Shah’s renegotiation of the contract price. Mr Shah affirmed and completed the contract in October 2015 with a knowledge of the reported sales through to September 2015. In his email to Mr Li of 14 October 2015 Mr Shah claimed that there had been an average decline in average sales of $850. He decided to proceed with the purchase at the reduced price on the basis that the average weekly sales were between $15,000 and $15,500.

79 I am satisfied that the evidence shows that the business was in decline in the three or four months leading up to completion of the sale to Mr Shah and that he was aware of this. Whether or not this decline was due to the commencement of the light rail works, as Mr Hagemrad claimed in his discussions with Mr Shah in October 2015, or was attributable to one of the other four factors is not readily apparent. What is clear, however, is that the impact of the removal of the bus stop was not likely to be felt until October 2015, the same month in which Mr Shah took control of the business.

80 I am satisfied that the removal of the bus stop was likely to have a material effect on Mr Shah’s business. Whether or not it provides a complete explanation for the significant decline in monthly sales that occurred in the period November 2015 to October 2016 is more difficult to say. Neither side called any expert evidence addressing this question and all I am left with are the competing assertions of Mr Shah and Mr Hagemrad, the fact that the buses ceased to run along George Street in October 2015, and the significant decline in sales that took place from about that time onwards.

81 It seems to me that the removal of the bus stop near the Haymarket franchise and the re-routing of the buses that had until then travelled along George Street and stopped near the Haymarket franchise is likely to have made some contribution to the decline in sales in the months of November and December 2015 and January to October 2016. However, the proposition that the decline in sales of the Haymarket franchise when it was under Mr Shah’s management when compared to prior periods under Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche’s management is wholly attributable to the removal of the bus stop or any one or more of the other four factors referred to above is not one that I am willing to accept. While the re-routing of the buses in October 2015 and the absence of outdoor seating in early 2016 are likely to have contributed to the decline in revenue, I do not think they can fully explain the significant decline in revenue that Mr Shah experienced.

82 Mr Hagemrad gave evidence that he took no steps to stop Mr Allouche from stealing the takings of the business because of the close relationship he had with Mr Allouche and the close relationship between Mr Allouche’s family and Mr Hagemrad’s family. I did not find this explanation convincing. I find it almost inconceivable that Mr Hagemrad would have permitted Mr Allouche to misappropriate such large sums of money from the business over a period of 12 or 18 months without taking steps to stop him from doing so.

83 In his evidence Mr Hagemrad said that he had a closed circuit television (“CCTV”) recording of Mr Allouche stealing from the business. His evidence as to when he first reviewed the CCTV recordings that established that it was Mr Allouche who was stealing money was rather vague. Exactly what the CCTV recording he referred to showed was not revealed. He did not seek to introduce it into evidence as one might expect him to have done if it corroborated his version of events. Nor was there any other contemporaneous evidence before me to indicate that Mr Hagemrad complained to Mr Allouche about any alleged theft of money during 2014 or 2015.

84 Mr Hagemrad was asked a number of times when he first realised that Mr Allouche was stealing money from the business. He said that he initially realised that “something was going on” in mid-2014. Mr Hagemrad said:

I initially realised something was going on mid-2014. I then undertook my own investigations and came to the realisation early 2015 that that was actually occurring, and it was – it was him. I wasn’t aware who was doing it initially.

85 He was asked how he became aware that Mr Allouche was taking money. It was at this point that he first mentioned the CCTV recordings. When asked when he first examined the CCTV recordings and observed that Allouche was stealing money, he said that this occurred in mid to late 2014:

… but my observations were – it took me about almost six months to crystallise the fact that it was occurring, given the nature of our relationship, your Honour, it – it was quite a significant situation I had to deal with that I had never been faced before – with before.

86 Mr Hagemrad said in his evidence that he realised something was going on in mid-2014 but that he did not come to understand that Mr Allouche was stealing money until early 2015. He told me that it took “almost six months to crystallise the fact that it was occurring”.

87 In the course of his cross-examination Mr Hagemrad gave the following evidence:

In fact, the combo reports could not be right because if they were the business would not be losing money, it would be making substantial amounts of money. That’s right, isn’t it?---The business wasn’t losing money.

So are you saying that the business was profitable except your cousin was, instead, taking thousands of dollars out every week?---Yes, I am.

And you’re quite happy to put tens of thousands of dollars of your own money into the business rather than put a stop to that?---At the time, like I said, how I dealt with it was the best way I thought to do so. Whether it’s correct or incorrect, I don’t know. If I were facing it again I can’t say I wouldn’t do the same thing again, but unfortunately, this situation, I have no idea how to deal with.

Mr Hagemrad, that’s simply untrue, isn’t it? There was no stealing on that scale from Mr Allouche, was there?---No, that’s incorrect.

You and Mr Allouche had decided that you would sell this loss making business in about mid-2014, didn’t you?---No, that’s incorrect.

And you and he had decided to inflate the figures using the POS system to make it favourable to a potential purchaser. That’s right, isn’t it?---No, that’s incorrect.

Because if you needed cash for the business you wouldn’t put in your own money of the amounts that you were putting in, you would simply stop Mr Allouche from taking those moneys in the first place. That’s right, isn’t it?---In a perfect world that’s how I would have loved to have dealt with it. Unfortunately I dealt with it with – the best way I thought at the time.

Now, if I can ask you to move - - -

HIS HONOUR: Which was what? Just let him continue to take money from the business?---Your Honour, once again I can’t stress how deep this relationship goes into the family and - - -

Yes, but my question is that your way of dealing with this was just to let him keep taking money from the business. Is that fair to say?---At the time it wasn’t – my focus wasn’t on the money. My focus was solely on how do I deal with this situation? How do I deal with the family behind it? The financial aspect was not my priority at the time.

So what’s the answer to my question? You were content to let him keep taking money from the business?---At the time, yes, your Honour.

That’s from, when, late 2014 right through till the time you completed on the sale, is that right?---Yes. I mean, I assumed he was – I had confronted him and the hope was that he would stop his actions but I had no way of dealing with it otherwise. I mean, the sale was the best way to sever our relation - - -

88 The evidence established that throughout most of 2014 and 2015 the business was in a dire financial state. Mr Hagemrad’s evidence was that although the business experienced cash flow problems as a result of Mr Allouche’s stealing, it was at all times profitable. As a result of what Mr Hagemrad characterised as “cash flow problems” it was necessary for him to pay some of the business expenses using his personal credit cards and using money that he obtained from a bank account in his wife’s name. This included approximately $45,000 transferred from accounts in his wife’s name between March and May 2015. He also gave evidence that he met during this period with Mr Allouche and Mr Howland on various occasions to discuss the cash flow difficulties at which time Mr Howland was requested to contribute additional funds to help keep the business running. Mr Hagemrad, according to his evidence, said nothing to Mr Howland about Mr Allouche’s misappropriations.

89 In his evidence Mr Hagemrad asserted that Mr Allouche misappropriated the proceeds of the sale of the business. There is some documentary evidence that indicates that Mr Hagemrad complained about this alleged misappropriation in early 2016 when, I infer, he took steps to have RGD and Cohort D wound up in a proceeding in the Supreme Court of New South Wales (“the Supreme Court Proceedings”) that he commenced against those companies, Mr Allouche and Mr Howland. There is no direct evidence as to what the outcome of those proceedings was although I infer that winding up orders were made against RGD and Cohort D. But the evidence does not indicate that Mr Hagemrad was at that stage asserting that Mr Allouche had ever stolen cash received from customers.

90 It is apparent from evidence given by Mr Hagemrad during cross-examination that he made an affidavit (apparently sworn on 24 March 2016) in support of his application for relief in the Supreme Court Proceedings. It is also apparent from his oral evidence that he said in his affidavit that Mr Howland provided funds for the fit-out of the Haymarket store and that he was an equal partner in the business. According to Mr Hagemrad’s oral evidence, he deposed in his affidavit that in 2015 “the franchise business was losing substantial amounts of money” and that, during a meeting with Mr Allouche and Mr Howland, he said to them:

We have been in a dire situation for some time, my personal credit card is now loaded with business expenses, and I have been unable to reimburse those expenses. I am also facing significant interest, fees and charges due to these business expenses and don’t’ how we’re going to account for these fees.

No part of the affidavit was tendered in evidence.

91 If the affidavit contained any suggestion that the losses referred to by Mr Hagemrad were anything other than trading losses, or, more particularly, that they represented nothing more than cash flow difficulties experienced by a profitable business then I would have expected to have seen the affidavit (or some relevant part) put into evidence or for the matter to have been explored in re-examination. In his oral evidence before me Mr Hagemrad claimed that “[o]n paper, the business was flourishing”. He volunteered this to me when answering the following questions:

HIS HONOUR: Just to understand this – so you’re saying he’s really just misclassifying a transaction as a credit sale rather than a cash sale?---That’s correct, your Honour.

All right. And you say that wouldn’t affect the viability of the business?---No. No, he’s still recording - - -

Because basically either the money is being received in cash or it has been received by a – from a bank?---That’s correct. That’s correct.

And in light of that, why has all this additional money been put into the business over the preceding 12-month period?---Because that cash – he’s removing that cash and taking it for himself. So the actual liquid cash position of the business has been affected. On paper, the business in [sic] flourishing, but when you remove that surplus cash, if that surplus cash was actually banked, then we wouldn’t have an issue; however, he was removing that money; taking it for his own purposes. So the liquid capital – sorry – liquid cash position of the business was affected, hence why there was so much working capital that had to be put back in.

So each week your earnings – your cash earnings – it doesn’t matter whether they’re from credit card or cash sales – were – what – some thousands of dollars under what they should have been?---That’s correct. Yes, your Honour.

DR GREINKE: And you say that you only found out about or started to suspect in late 2014?---That’s correct.

We’re talking November, December or earlier than that?---I think, around about August or thereabouts.

I do not accept any of this evidence. I am satisfied that it is false.

92 The bank statements for the Westpac accounts show that the account balance fell from $50,000 in January 2014 to $2,442 in June 2014. From July 2014 onwards, the Westpac accounts were regularly overdrawn and, from early 2015, direct debits against those accounts were regularly rejected. By May 2015, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche had been issued with formal breach notices by Subway Systems for outstanding rent ($33,786.56), royalties ($7,353.91) and advertising fees ($4,074.70). In May 2015, the landlord and its agent, Ray White, issued a letter threatening to take possession of the Haymarket store and to change the locks if the rental and water usage arrears were not paid by Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche within 14 days. Another formal breach notice was given to them by Subway Systems in August 2015.

93 Mr Hagemrad was asked about a deposit of $5,000 made by Mr Howland to one of the Westpac accounts on 12 August 2015. Mr Hagemrad accepted that this deposit was made after he asked Mr Howland to put more money into the business. Mr Hagemrad then gave this evidence about his dealings with Mr Howland:

So – and you’ve asked him to put more money into the business?---I have.

And what was the reason you gave him on this occasion for why the money had to go in?---It was the same as the previous reason. I believe it was the same conversation. He just did it – did it in two – two payments. Yes.

HIS HONOUR: […] He’s a one-third partner in the business under your handshake arrangement?---Yes. That’s correct.

And you asked him to put more money into the business without disclosing to him that your partner is stealing money?---There was [sic] questions asked, and we had some discussions, and I was trying to work out how to put it to him. I ended up sending him an email sometime later.

DR GREINKE: The truth is, isn’t it, Mr Hagemrad, that you asked Mr Howland to put money into the business because it was making losses, and you needed to address the cash flow; that’s the truth, isn’t it?---No.

It didn’t have anything to do – the state of the business didn’t have anything to do with your brother taking money out of the business, did it?---My cousin. But no.

It is not apparent from the evidence when the email referred to by Mr Hagemrad in this evidence was sent or what it said. The email (if there ever was one) never went into evidence.

94 I reject as false Mr Hagemrad’s evidence that the Haymarket franchise was profitable and that the cash flow difficulties experienced by the business in 2014 and 2015 were due to Mr Allouche stealing money from the business. In my view, this is not the true explanation for the serious cash flow problems that the business experienced in that period.

95 In general, disbelief of evidence given by a witness as to the existence of a particular state of affairs does not afford evidence of the non-existence of that state of affairs. However, as was recognised in Steinberg v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1975) 134 CLR 640, Gibbs J (as his Honour then was), this will not always be so. His Honour said at 694:

The question that then arises, however, is whether it was right to conclude, as his Honour did, that the shares in the company were bought to enable the purchasers to acquire the land for the main or dominant purpose of profit-making by sale. The fact that a witness is disbelieved does not prove the opposite of what he asserted: Scott Fell v. Lloyd [(1911) 13 CLR 230, at p. 241]; Hobbs v. Tinling (C.T.) & Co. Ltd. [[1929] 2 KB 1, at p. 21]. It has sometimes been said that where the story of a witness is disbelieved, the result is simply that there is no evidence on the subject (Jack v. Smail [(1906) 2 CLR 684, at p. 698]; Malzy v. Eichholz [[1916] 2 KB 308, at p. 321]; Ex parte Bear; Re Jones [(1945) 46 SR (NSW) 126, at p.128], but although this is no doubt true in many cases it is not correct as a universal proposition. There may be circumstances in which an inference can be drawn from the fact that the witness has told a false story, for example, that the truth would be harmful to him; and it is no doubt for this reason that false statements by an accused person may sometimes be regarded as corroboration of other evidence given in a criminal case: Eade v. The King [34 CLR 154, at p. 15]; Tripodi v. The Queen [(1961) 104 CLR 1]. Moreover, if the truth must lie between two alternative states of fact, disbelief in evidence that one of the state of facts exists may support the existence of the alternative state of facts: Lee v. Russell [[1961] WAR 103, at p. 109].

96 Lee v Russell [1961] WAR 103 was a decision of the Full Court of Supreme Court of Western Australia in which it was held that where one of two alternative states of fact must be true and the other false, disbelief in evidence which affirms the truth of one, may support the existence of the other. In that case the trial judge disbelieved evidence given by Tilbrook that Russell (the deceased driver of a motor vehicle in which they were travelling) showed no signs of intoxication prior to a crash in which Russell was killed and Tilbrook was injured. D’Arcy J (Jackson SPJ and Virtue J concurring) said at 109:

Counsel for the appellant then invited attention to paragraph 12 of the judgment in which the learned trial judge said that he would not have accepted the evidence of Southern and Pearson [expert witnesses called by the defendant] as intended to show that Russell would have been exhibiting marked indicia of intoxication, had that evidence stood alone, but that it supported an impression he had gained in listening to Tilbrook 's evidence. The learned trial judge then states that while he found Tilbrook a truthful witness in general, he disbelieved him because of the manner in which he testified when he said he observed nothing to suggest that Russell was affected by alcohol. Counsel submitted that this gave no support to the conclusion suggested by the evidence of Southern and Pearson because the rejection of that portion of Tilbrook's evidence could not afford proof that Tilbrook did, in fact, observe that Russell was affected. He cited as authority, if indeed authority be necessary for so obvious a proposition, the observation of Griffiths, C.J., in Scott Fell v. Lloyd (1911), 13 CLR 230, at p. 241.

The dictum, which relates to the fallacy of relying on disbelief in the testimony of a witness as providing positive support for the proposition that the contrary of such testimony is true, clearly has no application where the testimony affirms the truth of one of two alternative states of fact, one of which must be true and the other must be false, and where consequently disbelief in the evidence that one of the states of fact exists of necessity supports the existence of the other as a matter of logical inference.

The present case is one of this character and accordingly the learned trial judge's reasoning cannot in any way be impugned. The first stage in the analysis of the process of inference by which he reached his conclusion was his consideration of Tilbrook 's evidence in cross-examination that he was not taking much notice of Russell's condition. This evidence, on a question of credibility, the judge rejects as untrue, from which the conclusion necessarily followed that Tilbrook was taking notice, which indeed is suggested in his examination in chief. If he was taking notice, as the learned trial judge found, either Russell was showing signs of drink or not. Those are the only alternatives. The learned trial judge's disbelief in Tilbrook's positive evidence that he could see no signs of insobriety in Russell entitled, and indeed required him, to draw the inference which he, in fact, drew that Tilbrook observed such signs.

97 In Broken Hill Proprietary Company Ltd v Waugh (1988) 14 NSWLR 360 at 366, Clarke JA (with whom Kirby P and Hope J agreed) noted that Barwick CJ in Steinberg seemed to regard the proposition in support of which Gibbs J cited Lee v Russell as doubtful. Having quoted from D’Arcy J’s judgment at 109 Clarke JA said at 366:

Barwick CJ seemed to regard this proposition as doubtful but even if it be accepted as correct there is no basis for its application in this case. In the first place the positive inference is dependent upon disbelief of the existence of one or two alternative states of fact. Hence it is not applicable unless the judge disbelieves the evidence which is given. That is, that he finds that the witness is lying. Mere inability to accept the evidence because, for instance, the judge doubted the accuracy of the witness's recall or thought that he may have been confused could not, in my opinion, provide the foundation for a positive finding that the contrary was true. The learned Master in this case did not express his disbelief in the respondent's evidence nor did he imply it.

I do have some difficulty with the facts of Lee v Russell. It does not seem to me to have been a case involving true alternative states of fact. It is not easy to see how the trial judge’s rejection of Tilbrook’s testimony that he did not see in Russell signs of intoxication is evidence that Russell was indeed intoxicated.

98 The present case is very different. It was not suggested by Mr Hagemrad that Mr Allouche may have been recording fake sales (along the lines alleged by Mr Shah) without Mr Hagemrad’s knowledge. Rather, his sole answer to Mr Shah’s allegation was to deny it and instead seek to explain away the discrepancies between the Combo Reports and the banking records on the basis that these were brought about by Mr Allouche’s fraudulent misclassification of cash sales as credit sales.

99 My rejection of Mr Hagemrad on the basis that his evidence was false raises the question of what else might explain both the cash flow problems and the differences between what was recorded in the Combo Reports and the bank statements. The only other explanation open is that there were significant sales transactions recorded that never generated any cash. I think this is a case in which the factual circumstances that lead to my rejection of Mr Hagemrad’s evidence provide a strong basis for inferring that the latter explanation is more likely than not correct: see Calvin v Carr [1977] 2 NSWLR 308 at 328 per Rath J.

100 I am satisfied that the true explanation for the cash flow problems experienced by the Haymarket franchise was the poor trading performance of the business. I am also satisfied that the banking records for the period June 2014 to October 2015 provide a much more reliable record of the takings of the business during that period than the Combo Reports and that the Combo Reports significantly overstate the sales that were made from about May 2014 to September 2015. I am satisfied that this is more likely than not the result of fake sales that were registered by either Mr Allouche or Mr Hagemrad or both.

101 I am also satisfied that each of Mr Allouche and Mr Hagemrad knew of the fake sales and that they were created in order to falsely inflate the sales figures so that they could obtain a better price for the Haymarket franchise when they came to sell it. Mr Hagemrad said in his evidence that he first made the decision to sell the business in about December 2014 or January 2015. I do not accept that evidence. I think it is more likely that Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche decided to sell the business in mid-2014 when the business was facing significant cash flow problems.

102 On the question of reliance, I am satisfied that if (as I have found) the actual average weekly sales for the Haymarket franchise were in the vicinity of $12,000 per week then Mr Shah would never have agreed to purchase the Haymarket franchise.

103 Mr Wood placed considerable reliance on the contract entered into by Mr Shah including cl 2. It includes an “entire agreement” provision and an acknowledgement by the purchasers that they are not relying upon any representation that is not expressly warranted in the contract. It also purports to withdraw any representation previously made that is not expressly warranted in the contract and further provides for a mutual release in respect of all claims made in respect of any such representation.

104 Mr Wood submitted that the fact that Mr Shah signed the contract including that clause was a relevant circumstance that indicates that Mr Shah did not rely on the Combo Reports and that any misrepresentation conveyed by the provision of those documents to Mr Shah was not the cause of his loss. I do not accept that submission.

105 With regard to “exclusion” or “no reliance” clauses, French CJ observed in Campbell v Back Office Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [31]:

Where the impugned conduct comprises allegedly misleading pre-contractual representations, a contractual disclaimer of reliance will ordinarily be considered in relation to the question of causation. For if a person expressly declares in a contractual document that he or she did not rely upon pre-contractual representations, that declaration may, according to the circumstances, be evidence of non-reliance and of the want of a causal link between the impugned conduct and the loss or damage flowing from entry into the contract. In many cases, such a provision will not be taken to evidence a break in the causal link between misleading or deceptive conduct and loss. The person making the declaration may nevertheless be found to have been actuated by the misrepresentations into entering the contract. The question is not one of law, but of fact.

(footnotes omitted)

106 In the present case I am satisfied that Mr Shah relied on the Combo Reports notwithstanding what appeared in the disclaimer accompanying the Intro Pack and that he signed a contract (which he understood himself to be bound by) containing the extensive “no reliance” and related provisions found in cl 2. I am mindful that at all relevant times Mr Shah had the benefit of legal and accounting advice, that he took the opportunity to observe the operations of the Haymarket franchise with his wife on a number of occasions, and that he was alive to the possibility that the Combo Reports might include some “fake sales”. Nevertheless, I have no doubt that Mr Shah relied on the Combo Reports and that, had he known that the Combo Reports overstated the actual sales of the business in the period to which they related to the tune of approximately 30%, he would never have agreed to make the purchase, or at least not at a price that Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche would have been willing to accept.

107 Further, I do not think that by placing reliance on the Combo Reports Mr Shah acted unreasonably or that he failed to take proper care of his own interests. The evidence in this case, from both Mr Shah and Mr Hagemrad, is that Combo Reports are treated by franchisees and prospective purchasers of a Subway franchise as important and reliable records of a Subway store’s sale performance. As Mr Shah put it in his oral evidence, a “combo report is like a bible for a Subway store” and is one of the first documents that the purchaser asks for when considering whether or not to purchase a Subway franchise.

108 I am satisfied that the first and second respondents engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by providing (directly and through Mr Li) Combo Reports to Mr Shah that misrepresented sales for the Haymarket franchise in circumstances where they knew those documents were likely to be relied on by Mr Shah.

109 This brings me to the question of the amount of Mr Shah’s damages.

110 Damages arising from the purchase of a business as a result of a misleading or deceptive statement are assessed by reference to the difference between the value of the business at the date of purchase and the price paid for the business. Although the court values the business at the date when the applicants suffered the relevant loss, it must also consider subsequent events for the purpose of considering whether they also give a reliable indication or reflection of such loss: see Kizbeau Pty Limited v WG & B Pty Limited (1995) 184 CLR 281 at 296.

111 The evidence in relation to the value of the business at the time of purchase is rather scant. The valuation expert retained by Mr Shah was not called. Instead, Dr Greinke tendered the expert report filed by Mr Hagemrad of Mr Michael Ozich. There was no objection to that document, and Mr Ozich was not required for cross-examination.

112 It was submitted on behalf of Mr Shah that the Haymarket franchise was of no value because the business was incapable of making a profit. Although Mr Wood disputed that the business was worthless, he accepted, consistently with Mr Ozich’s expert report, that if the nett weekly sales (exclusive of GST) for the business were any less than $11,200 then the business was essentially worthless.

113 I do not accept Dr Greinke’s submission. In my view, the business should be valued on the basis of its trading performance as at October 2015 which was when Mr Shah re-negotiated the contract. Recognising that it is impossible to be exact in this exercise, I am satisfied that the business was by that time one achieving actual nett sales (exclusive of GST) of about $12,000 per week based upon the probable actual sales figures for the preceding 12 months.

114 According to Mr Ozich’s report, on the assumption that the nett weekly sales (exclusive of GST) for the business were $13,000, the business was worth approximately $230,000. On the assumption that the nett weekly sales (exclusive of GST) were $11,200 he valued the business at $40,000. Mr Ozich’s report does not specify a valuation for the business if the average weekly sales (exclusive of GST) were approximately $12,000.

115 Doing the best I can given the limitations of the valuation evidence, I am satisfied that the business was likely to have a value of approximately $160,000 in October 2015, and I propose to assess damages on that basis. This includes an allowance for the value of stock. The difference between the amount paid by Mr Shah ($460,000) and the true value of the business ($160,000) as at October 2015 is $300,000 which represents the amount of Mr Shah’s loss excluding any interest component.

116 With regard to the matter of proportionate liability, I am satisfied that each of Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche were concurrent wrongdoers who fraudulently caused the economic loss the subject of Mr Shah’s claim. Accordingly, I am satisfied that s 87CC(1)(b) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) applies. On that basis there will be a judgment entered against Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche for the whole of the proven loss.