THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Resource Capital Fund IV LP v Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCA 41

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

NSD 277 of 2014 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | RESOURCE CAPITAL FUND V LP Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceedings be listed for mention at 9.30am on Friday, 9 February 2018.

2. The proceedings be listed for hearing on Friday, 16 February 2018 in Sydney.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PAGONE J:

1 These proceedings raise for consideration the proper tax treatment of profits made by Resource Capital Fund IV LP (“RCF IV”) and Resource Capital Fund V LP (“RCF V”), from the sale of their shares and interests in Talison Lithium Limited (“Talison Lithium”), an Australian company, in March 2013. Proceeding NSD 276 of 2014 challenges the correctness of an assessment issued by the Commissioner on 25 March 2013 to RCF IV which was sent on that day with a covering letter addressed to the General Partner of that partnership. Proceeding NSD 277 of 2014 concerns an assessment issued by the Commissioner on 25 March 2013 to RCF V which was sent on that day with a covering letter addressed to the General Partner of that partnership. Objections in both cases were lodged in the name of the partnerships and each of the proceedings was commenced in the name of the partnerships rather than in the name of any of the partners. Leave was subsequently given, however, for the General Partner of each of the partnerships to be joined as parties to the proceedings. The applicants submitted that the proper parties to the proceeding were the partners of the partnerships rather than the partnerships, which the applicants submitted did not exist as legal entities. The Commissioner maintained, in contrast, that the proper applicants in the proceedings were the partnerships as taxable entities but did not oppose the joinder of the General Partners to the proceedings to permit the General Partners to seek the relief sought in the proceedings, namely, that the objections should be allowed and the assessments set aside.

2 The formal joinder of the General Partner to each of the proceedings related to a fundamental issue between the parties about the operation of the relief afforded by the Convention between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United States of America for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income (“the United States Convention”). The Commissioner’s assessments were made under Division 5A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (“the 1936 Act”) which by s 94A provided for certain limited partnerships to be treated as companies for tax purposes. The Commissioner maintained that the provisions of Division 5A contemplated that certain limited partnerships, including RCF IV and RCF V, were to be treated as taxable entities and were able to be assessed to tax in that capacity. The Commissioner had previously assessed Resource Capital Fund III LP (“RCF III”) as a taxable entity, and RCF III had objected to the assessments but had unsuccessfully sought to obtain relief under the United States Convention: see Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Resource Capital Fund III LP (2014) 225 FCR 290 (“RCF III”). The partnership constituting the RCF III partnership had objected to the assessments, and had maintained proceedings as if RCF III were a taxpayer under Part IVC of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (“the Administration Act”). It was contended for the partners of the RCF IV and RCF V partnerships, however, that the RCF III proceedings had been conducted upon the erroneous basis that RCF III was a legal entity able to be taxed as a separate taxable entity. The Commissioner submitted, in contrast, that the assessments had properly been issued to RCF IV and RCF V as taxable entities and that the decision in RCF III had conclusively determined as a matter of law that the partnerships were taxable entities. It becomes necessary to consider, therefore, the provisions of Division 5A of the 1936 Act and whether the decision of the Full Court in RCF III decided that a limited partnership within Division 5A was a taxable entity able to be assessed as such.

3 A partnership is not a separate legal person in law distinct from the individuals who comprise it, but is, rather, an association of legal persons carrying on a business in common with a view of profit: K.L. Fletcher, The Law of Partnership in Australia (Law Book Company, 9th edition, 2007), p 3 [1.05]. In Rose v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1951) 84 CLR 118, the High Court rejected the proposition which had been put by the Commissioner in that case that the 1936 Act required a partnership to be considered as a separate legal entity separately from the individuals who composed it. At 124 the Court said in a joint judgment:

The commissioner’s case must therefore depend on making good the proposition that for the purpose of s. 36 a partnership is to be considered a separate entity distinct from the individuals who compose it, so that when the taxpayer vested what was his as an entirety in himself and his two sons as partners having co-ownership, he is to be considered for the purposes of s. 36 as having “disposed of” the property as an entirety in the assets to a distinct legal entity. A partnership is not a distinct legal entity according to English law. In Scots law a firm is a legal person distinct from the partners of whom it is composed. But in our law it is far otherwise with partnerships. “The members of these do not form a collective whole, distinct from the individuals composing it; nor are they collectively endowed with any capacity of acquiring rights or incurring obligations”: Lindley on Partnership, 11th ed. (1950), vol. 1, ch. 1, s. 4. If, therefore, a partnership is to be treated for the purpose of s. 36 as a distinct legal entity, it must be because of an assumption which the Income Tax Assessment Act requires, not because of the general law. But an examination of that Act discloses no ground for construing it as requiring that such an assumption should be made. By s. 6 the word “partnership” is defined to mean an association of persons carrying on business as partners or in the receipt of income jointly but not to include a company. Division 5 of Part III, which deals with partnerships, is based upon the view that the collective income earned by the partnership belongs according to their shares to the partners regardless of its liberation from the funds of the partnership, that is, its actual distribution. There appears to be no foundation for importing into s. 36 a conception of a partnership varying from that adopted by the general law.

In Commissioner of Taxation v Beville [1953] ALR 490 Taylor J at 492-3 also rejected a submission that proceeded from the Commissioner’s argument that a partnership should be regarded as “an entity distinct from the partners themselves” for the purposes of the 1936 Act.

4 The ordinary provisions applicable to the taxation of partnerships are found in Division 5 of the 1936 Act. Division 5 in general terms treats a partnership “as if” it were a taxpayer, but does so only for the purpose of calculating the amounts to be included in the individual returns of the partners. Section 91 obliges a partnership to furnish a return of the income of the partnership but expressly provides that the partnership is not liable to pay tax thereon. The liability, if any, to pay tax falls upon the individual partners who are obliged to include in their individual returns their share of partnership profits and who may claim in their individual returns their share of any partnership loss. Section 92 is concerned with the income to be included, and the deductions that may be allowed, by a partner by reference to the individual interest of the partner in the net income of the partnership or of the partnership loss. Section 90 contains definitions of “exempt income”, “net income”, “non-assessable non-exempt income” and “partnership loss” in relation to a partnership on the basis that each be calculated “as if” the partnership were a taxpayer who was a resident in Australia. In Tikva Investments Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1972) 128 CLR 158 Stephen J explained at 168, by reference to the decisions in Rose and Beville, that when s 90 referred to the assessable income of a partnership being calculated “as if the partnership were a taxpayer” it was doing so “for the purpose of calculation of assessable income, but for that purpose only, a new taxpayer [was] brought into existence”. His Honour went on to observe that for “all other relevant purposes” it was “with the individual members” of the partnership that the Act was concerned.

5 The decision in RCF III proceeded, however, from a basis that was different from that which had been considered in Rose, Beville and Tikva. Rose had been referred to in the submissions of the parties in RCF III, but Tikva was not referred to, and neither party had contended in those proceedings that the assessment in RCF III could only have been issued to the partners rather than to the partnership. The arguments in RCF III had, rather, proceeded from the assumption that Division 5A had created a limited partnership as a new category of taxable entity which was able to be taxed separately from the partners. The Full Court referred therefore, without argument to the contrary, at [29] to RCF III as “an independent taxable entity in Australia and liable to tax on Australian sourced income”, and at [30] to RCF III as “a separate taxable entity taxed as a company”, without that issue having been in dispute in the proceeding. The issue had not been in dispute in RCF III because in that case the contention of the applicant had been that it was the partnership as a taxable entity which was entitled to the relief afforded by the United States Convention. The Commissioner’s contrary contention had been that RCF III as a taxable entity was not entitled to the relief which was afforded by the United States Convention to the partners and, therefore, in those proceedings the parties had joined issue on whether the partnership as a taxable entity was entitled to the treaty relief, and no submission was put by either party that RCF III was not a taxable entity. An application to the High Court for special leave to appeal was rejected on the basis that the decision of the Full Court was not attended by sufficient doubt to warrant the grant of special leave, but neither party contended in the application for special leave that the partnership had not been properly assessed as a taxable entity. The decision of the Full Court was described by Crennan J in dismissing the application for special leave as a finding by the Full Court that the limited partnership was not entitled to the benefits of the United States Convention. In dismissing the application for special leave to appeal her Honour described a limited partnership, as had been the case of both parties in RCF III, as “an independent taxable entity in Australia and liable to tax on Australian sourced income”, but her Honour was not affirming a finding by that description of a contested fact.

6 The applicants in these proceedings contended, therefore, that the decision in RCF III did not determine that the partnerships were taxable entities separate from the partners and maintained that the decision in RCF III did not prevent the partners from claiming the relief afforded to the partners under the United States Convention. The doctrine of precedent does not permit this Court to disregard a binding decision of an appellate court. In Proctor v Jetway Aviation Pty Ltd [1984] 1 NSWLR 166 Moffitt P said at 177:

The obligation of every court loyally to follow decisions of any court superior to it has been often stated. At times it may appear to a judge or to an appeal court that the reasoning or absence of it in a binding decision renders that decision unsatisfactory. However, the law concerning precedent, based as it is on the need for certainty in the law, absolutely binds him to follow the precedent. He is as much bound by the law of precedent and the law so pronounced as he is by any other law. The law provides its own rules to admit of flexibility. These rules, which are part of the binding law of precedent, permit departure from prior erroneous decisions, but only in prescribed circumstances. The law binding on all does not include any right of a court to depart from a decision of a superior court and hence one binding upon it upon some basis, such as that some matter is considered to have been overlooked by the superior court or for some other reason it appears to be wrong. It does not permit it to disregard a binding decision of an appellate court on some view based on the reasoning of judges in a decision of an ultimate appellate court which does not overrule the binding decision. An example of this is provided by the reasons of some members of the High Court in Stage Club Ltd v Millers Hotel Pty Ltd which certainly did not overrule McGee or even deal with the same question.

The obligation to follow a decision on a question considered by an appellate court does not arise, however, where the court has assumed a proposition of law to be correct without addressing its mind to it even where the decision on a point of law in a particular sense was essential to the earlier decision. In Re Hetherington (deceased) [1990] Ch 1 Browne-Wilkinson VC considered whether he was bound by a decision made by the House of Lords on a question which had been considered by the House of Lords that was applicable also to the case before him. At 9-10 his Lordship said:

However, the fact remains that the House of Lords did decide that a trust for Masses was a valid trust and that under the law as we know it now to be such trusts cannot be valid unless (a) they were not illegal under the Chantries Act and (b) they were either charitable trusts or trusts of the anomalous class. The question therefore is whether I am bound by the decision made by the House of Lords to hold that in the present case the claim of the next of kin must fail.

In my judgment, I am not so bound. In Baker v. The Queen [1975] A.C. 774, Lord Diplock, after mentioning that the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council does not normally allow parties to raise for the first time on appeal a point of law not argued in the court below, said, at p. 788:

“A consequence of this practice is that in its opinions delivered on an appeal the Board may have assumed, without itself deciding, that a proposition of law which was not disputed by the parties in the court from which the appeal is brought is correct. The proposition of law so assumed to be correct may be incorporated, whether expressly or by implication, in the ratio decidendi of the particular appeal; but because it does not bear the authority of an opinion reached by the Board itself it does not create a precedent for use in the decision of other cases.”

That decision was applied in Barrs v. Bethell [1982] Ch. 294, where after quoting the passage I have read from Lord Diplock, Warner J. continued, at p. 308:

“In my judgment, the principle that, where a court assumes a proposition of law to be correct without addressing its mind to it, the decision of that court is not binding authority for that proposition, applies generally. It is not confined to decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.”

That approach coincides with some words of May L.J. in the recent Court of Appeal case of Ashville Investments Ltd. v. Elmer Contractors Ltd. [1989] Q.B. 488, 494, where he said:

“In my opinion the doctrine of precedent only involves this: that when a case has been decided in a court it is only the legal principle or principles upon which that court has so decided that binds courts of concurrent or lower jurisdictions and require them to follow and adopt them when they are relevant to the decision in later cases before those courts. The ratio decidendi of a prior case, the reason why it was decided as it was, is in my view only to be understood in this somewhat limited sense.”

In my judgment the authorities therefore clearly establish that even where a decision of a point of law in a particular sense was essential to an earlier decision of a superior court, but that superior court merely assumed the correctness of the law on a particular issue, a judge in a later case is not bound to hold that the law is decided in that sense. So therefore, in my judgment, Bourne v. Keane [1919] A.C. 815 is not decisive of the case before me.

That passage was cited with approval in the majority joint judgment of the High Court in CSR Ltd v Eddy (2005) 226 CLR 1 at 11, [13] in which their Honours said:

These events placed the Court of Appeal in a difficult position. It is of course commonplace for the courts to apply received principles without argument: the doctrine of stare decisis in one of its essential functions avoids constant re-litigation of legal questions. But where a proposition of law is incorporated into the reasoning of a particular court, that proposition, even if it forms part of the ratio decidendi, is not binding on later courts if the particular court merely assumed its correctness without argument. “[T]he presidents, … sub silentio without argument, are of no moment.”

(Footnotes omitted.)

It is important to the issues in this proceeding that at no stage had it been contended by either party in the RCF III proceedings that Division 5A did not constitute or contemplate RCF III to be a limited partnership able to be taxed as a taxable entity separately from the partners. The Commissioner in RCF III, as in the present proceedings, had assessed the limited partnership as a separate taxable entity but neither party in RCF III had argued that Division 5A either did or did not create limited partnerships as taxable entities. It was, rather, assumed by both parties in RCF III that Division 5A permitted limited partnerships to be treated as separate taxable entities. Counsel for the applicant in RCF III had contended, not that the limited partnership could not be treated as a separate taxable entity, but, rather, that the partnership as a taxable entity was entitled to the Convention relief otherwise available to the partners of the partnership. The decision in Rose was unsuccessfully referred to in that context by counsel for the applicant in support of the proposition that the partners’ entitlements under the Convention must necessarily be available to the limited partnership.

7 The view that a limited partnership might be a legal entity may also have been assumed in other proceedings in this court involving RCF IV and RCF V. RCF IV and RCF V commenced proceedings in 2013 against the Commissioner in relation to notices which had been issued by the Commissioner under s 255 of the 1936 Act, but there was no issue raised in those proceedings about whether either of the partnerships was a taxable entity: see Resource Capital Fund IV L.P. v Commissioner of Taxation (2013) 95 ATR 638; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Resource Capital Fund IV L.P. (2013) 215 FCR 1. Rule 9.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), however, permits persons claiming as partners to start a proceeding in the partnership name and, to that extent, it may not have been necessary in those proceedings to consider whether RCF IV and RCF V were suing as separate taxable entities or were the partnership names in which the partners had started their proceedings.

8 It follows from those observations, and from the way in which the issue of RCF III as a taxable entity was considered in RCF III, that the view in RCF III that the partnership in that case was a taxable entity is not binding in these proceedings. It is true that the Full Court in RCF III referred to the limited partnership in that case as being a taxable entity but the correctness of that proposition was assumed without argument. The Commissioner had assessed the limited partnership as if it were a taxpayer able to be assessed separately from the partners and the applicant in RCF III had not contested that, but had sought to maintain, rather, that the relief available to the partners under the United States Convention was available also to the limited partnership. It was no part of the case of either party at any stage in those proceedings that the limited partnership was not a taxable entity able to be assessed as the Commissioner had done. The rejection of the application for special leave to appeal by the High Court was upon the same basis and assumption which had been made by the parties and which had been adopted by this Court. Furthermore, “reasons for refusing special leave to appeal in a civil proceeding are not themselves binding authority”: Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd (2015) 256 CLR 104 at 134, [119]; see also 133 at [112]. In those circumstances the question is not foreclosed from consideration in these proceedings.

9 It becomes necessary in these proceedings to consider, therefore, whether RCF IV and RCF V are taxable entities by reason of Division 5A of the 1936 Act as was submitted by the Commissioner. The object of the Division is described by s 94A as being “to provide for certain limited partnerships to be treated as companies for tax purposes”. This provision does not purport to create a new category of legal person or purport to deem certain limited partnerships to be companies, but, rather, identifies the objective of making provision for “certain limited partnerships” to be treated for tax purposes in the same way as companies are treated for tax purposes. The “certain limited partnerships” which fall within the operation of Division 5A are all a sub-category of “limited partnerships” as defined by s 995-1 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (“the 1997 Act”). That is because subdivision B in Division 5A identifies when a limited partnership is a corporate limited partnership which is to be taxed as a company by the modifications effected by subdivision C. But a corporate limited partnership affected by these provisions must first be a “limited partnership” within the meaning of s 995-1. That section provides that a limited partnership means:

(a) an association of persons (other than a company) carrying on business as partners or in receipt of ordinary income or statutory income jointly, where the liability of at least one of those persons is limited; or

(b) an association of persons (other than one referred to in paragraph (a)) with legal personality separate from those persons that was formed solely for the purpose of becoming a VCLP, and ESVCLP, and AFOF or a VCMP and to carry on activities that are carried on by a body of that kind.

Clause (b) of the definition of “limited partnership” does not apply to RCF IV or RCF V because neither was formed solely for the purpose of becoming one of the entities mentioned in (b), and clause (a) of the definition of “limited partnership” expressly contemplates an association of persons. The section does not, in other words, purport to create a new category of legal persons but assumes that legal persons associating in the way contemplated by the definition may fall within the definition of “limited partnership” as employed in Division 5A. Section 94C is, unsurprisingly, consistent with the conception of a limited partnership being an association by dealing with the change in the composition of a limited partnership and by providing that such a change will not affect the continuity of the partnership.

10 The way in which Division 5A required the relevant limited partnerships to be treated as companies for tax purposes requires consideration of the provisions in subdivision C of Division 5A. Section 94H provides that the “income tax law” has effect in relation to a corporate limited partnership subject to the provisions which come after s 94H. For this purpose “income tax law” is defined in s 94B to mean:

(a) this Act [which is defined in s 6(1) of the 1936 Act to include the 1997 Act] (other than this Division and Division 830 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997); and

(b) an Act that imposes any tax payable under this Act; and

(c) the Income Tax Rates Act 1986; and

(d) the Taxation Administration Act 1953, so far as it relates to an Act covered by paragraph (a), (b) or (c); and

(e) any other Act, so far as it relates to an Act covered by paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d); and

(f) regulations under an Act covered by any of the preceding paragraphs.

The provisions which come after s 94H set out changes to the way in which income tax law has effect in relation to a partnership which is a corporate limited partnership in relation to a year of income. None of the provisions expressly create a new legal person or expressly provide for there to be a new taxable entity. All of the provisions in Division 5A are consistent with those which had been considered in Tikva that treated a partnership “as if” it were a separate entity for the purpose of calculation only and not for the purpose of separate assessment or, relevantly, for an additional hurdle that might disentitle the partners to any relief that they might have under a provision of a treaty.

11 Both parties drew attention to different aspects of s 94U to make competing submissions about whether Division 5A created taxable entities. Section 94U is headed “incorporation” and provides:

94U Incorporation

For the purposes of the income tax law, the partnership is taken to have been incorporated:

(a) in the place where it was formed; and

(b) under a law in force in that place.

The applicants drew attention to the words “is taken” in this provision and emphasised the deeming effect of the section, whilst the Commissioner focused upon both those words with those which followed, namely “to have been incorporated”, to submit that they indicated an intention to create a taxable entity.

12 Section 94U is primarily directed to the need to make provision to modify the income tax laws to enable a partnership to be treated as a company because a partnership is neither a company nor any other legal person. Section 94U does not make partnerships taxable legal entities but, rather, is a provision identifying the way in which the tax law is, and must be, modified for partnerships to be treated as if they were a company. That is achieved in particular by deeming a place of incorporation and by deeming that incorporation to have been under a law in force in that place. The deeming, in other words, is of a notional place of incorporation, and of a notional law in force in that place of notional incorporation, as facts which are to be assumed because the assumptions are needed to enable the statutory fiction of treating limited partnerships as if they were companies to operate effectively. The provision does not in form, effect or purpose create a taxable entity, and its legislative function is in part similar to that found in the definitions in s 90, for the purpose of Division 5, of requiring that the calculation of the income of the partnership be as if the partnership were a taxpayer who was a resident. In that case the deeming is of a residency and in the case of s 94U the deeming is of its analogue, namely, of a place of incorporation.

13 The modification effected by s 94V is of particular significance in this context because it expressly limits (or undoes) some of the other modifications to the income tax law brought about by Division 5A. Section 94V provides:

94V Obligations and offences

(1) The application of the income tax law to the partnership as if the partnership were a company is subject to the following changes:

(a) obligations that would be imposed on the partnership are imposed instead on each partner, but may be discharged by any of the partners;

(b) the partners are jointly and severally liable to pay any amount that would be payable by the partnership;

(c) any offence against the income tax law that would otherwise be committed by the partnership is taken to have been committed by each of the partners.

(2) In a prosecution of a person for an offence that the person is taken to have committed because of paragraph (1)(c), it is a defence if the person proves that the person:

(a) did not aid, abet, counsel or procure the relevant act or omission; and

(b) was not in any way knowingly concerned in, or party to, the relevant act or omission (whether directly or indirectly and whether by any act or omission of the person).

It is significant that the changes effected by s 94V are of the way in which the income tax law was to apply to the partnership when treated as a company. The section changes, in other words, the way in which the other provisions were otherwise to apply to a partnership when those other provisions would have applied to a partnership as if the partnership were a company. Amongst those changes is that the obligations that would be imposed on the partnership “are imposed instead on each partner” and that each partner is jointly and severally liable to pay any amount that would otherwise be payable by the partnership. The need for such changes to what might otherwise obtain, arises from the possibility that requiring that the income tax law be applied to the partnership “as if” the partnership were a company might otherwise have resulted in the partnership, rather than the partners, becoming liable for obligations, or becoming liable to pay any amount, that “would be” of the partnership. The section deals with the obligations and liabilities imposed or arising in relation to the application of the income tax law (as defined). Those obligations and liabilities necessarily include the obligation and liability to pay tax by an assessment. The enactment of s 94V thus tells against the Commissioner’s argument that Division 5A was intended to permit assessments to be raised to the partnership rather than to the partners, and, if it is not a complete answer to the Commissioner’s argument, it is, at very least, a strong pointer in that direction. Nothing in s 94V, or in any other provision in Division 5A, authorises the Commissioner to impose any obligation or liability upon any person other than a partner, and if there had been any doubt where the liability and obligation fell, the doubt was expressly removed by s 94V.

14 The conclusion that the corporate limited partnerships are not created as separate taxable entities is thus required by the text of the provisions, but it is also required by consideration of the purpose of the provisions. The context and purpose of a provision are important to its construction. In Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Unit Trend Services Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 523 it was said in a joint judgment at [47]:

As French CJ, Hayne, Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ said in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd: “This Court has stated on many occasions that the task of statutory construction must begin with a consideration of the [statutory] text.” Context and purpose are also important. In Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross French CJ and Hayne J said:

“The context and purpose of a provision are important to its proper construction because, as the plurality said in Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority, ‘[t]he primary object of statutory construction is to construe the relevant provision so that it is consistent with the language and purpose of all the provisions of the statute’ … That is, statutory construction requires deciding what is the legal meaning of the relevant provision ‘by reference to the language of the instrument viewed as a whole’, and ‘the context, the general purpose and policy of a provision and its consistency and fairness are surer guides to its meaning than the logic with which it is constructed’.” (emphasis of French CJ and Hayne J)

(Footnotes omitted)

Section 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) requires the interpretation of an Act that will best serve the purpose or object of the Act, whether or not that purpose or object is expressly stated in the Act. The object and purpose served by s 94V is to ensure that the partners carry the burden brought about by the application of the income tax law to the partnership as if the partnership were a company. The partnership is treated as a company for the purposes of determining how the income tax law is to apply, but the factual and legal reality remains that the partnership is not a company and that any obligations and liabilities must fall upon the individual partners. The context and purpose of s 94V is to ensure that the partners are those who bear the obligations and liability arising from treating the partnership as a company for fiscal purposes.

15 That construction is also consistent with what had been said in relation to Division 5 in Rose, Beville and Tikva, of which the legislature must be assumed to have been aware when enacting the provisions of Division 5A. The construction is consistent also with the conclusion of Gzell J in Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v McGuire (2013) 275 FLR 153 in relation to the liability of a limited partnership constituted pursuant to the Partnership Act 1892 (NSW) to pay GST. His Honour observed at [22] that the legislation had provided that the limited partnership was liable to pay to the Commissioner the running balance account deficit debt and the general interest charge, but that the limited partnership “was not a legal entity”. The provisions which were considered by his Honour, which had some similarity to s 94V of the 1936 Act, made the partners liable to pay the tax liabilities notwithstanding that their liability to contribute to the liabilities of the partnership was as between them limited to $5.

16 It is not necessary for the purpose of construing these provisions to have recourse to the explanatory memorandum relating to the introduction of Division 5A, but it is sufficient to note that the explanatory memorandum supports the construction submitted by the applicants. Chapter 4 of the explanatory memorandum accompanying the Bill enacting Division 5A was concerned with the taxation of limited partnerships as companies. The then proposed s 94A was explained in Explanatory Memorandum, Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No. 6) 1992 at 30 as follows:

The bill will amend the Principal Act to introduce taxation arrangements in new Division 5A Part III of the Act for taxing limited partnerships [clause 8].

The object of this new Division is to ensure that limited partnerships will be treated as companies for taxation purposes. This is not confined to the payment of income tax by limited partnerships, but includes all other purposes under income tax law, including the payment of tax by partners in limited partnerships; for instance, imputation and the taxation of dividends to shareholders [new section 94A].

It is clear from this explanation of the proposed objects provision, that Division 5A was intended to treat a limited partnership as a company but not that there was an intention to create a new taxable entity. The explanatory memorandum went on to consider the nature of a limited partnership under the heading “What is a limited partnership?”. In that context the explanatory memorandum referred to the definition then found in the provision proposed as s 94B and made clear that a limited partnership was “any partnership” in which the liability of at least one partner was limited. The scope of the Division, in other words, was to apply broadly and was not limited to new taxable entities. The explanatory memorandum next considered the partnerships that qualified as “corporate limited partnerships”, under the heading “Which limited partnerships are affected?”, by reference to partnerships, and made no suggestion of new taxable entities being established by the then proposed law.

17 The explanation in the explanatory memorandum at 39 of the provision proposed to deal with incorporation is instructive by explaining that the rule to deem a place and law of incorporation for a corporate limited partnership which was proposed in s 94U was needed “to clarify the operation of several provisions relating to companies, as they apply to corporate limited partnerships”. The explanatory memorandum went on to deal with the obligations and offences of limited partnerships proposed in s 94V(1) as follows:

Obligations and offences of limited partnerships

Broadly, obligations and offences of limited partnerships are taken to be those of the individual partners, with certain joint and several liabilities. The reason for this approach is that, while corporate limited partnerships are generally treated as companies for the purposes of the income tax law, this does not convert them into companies for other purposes, including criminal law, monetary claims, and so on. So the obligations and offences of limited partnerships continue to be dealt with broadly as before these amendments. The law will provide for limited partnerships in much the same way as for other partnerships.

Where, as an entity, a corporate limited partnership is subject to an obligation under the income tax law, that obligation is imposed on each of the partners, but it may be discharged by any of them [new paragraph 94V(1)(a)].

Where, as an entity, any amount is payable under the income tax law by a corporate limited partnership, the partners are jointly and severally liable to pay that amount [new paragraph 94V(1)(b)];

Where, as an entity, any offence against the income tax law would have been committed by a corporate limited partnership, each partner will be deemed to have committed the offence [new paragraph 94V(1)(c)].

[…]

These passages reveal that a purpose of the legislation was to provide for corporate limited partnerships to be treated as corporations under the income tax law upon the assumption that corporate limited partnerships were not converted into companies for other purposes. The explanatory memorandum specifically noted, as was subsequently clearly provided, that an obligation under the income tax law of a corporate limited partnership was an obligation “imposed on each of the partners”. The explanatory memorandum specifically noted, as was also subsequently clearly provided, that “any amount” that was made payable under the income tax law by a corporate limited partnership was the joint and several liability of the parties and was to be paid by them. There was no suggestion anywhere in the explanatory memorandum of any concept of “taxable entity” or of corporate limited partnerships, or of certain limited partnerships, being created as taxable entities separate from the partners.

18 The conclusion that RCF IV and RCF V are not taxable entities makes it necessary to consider who has been assessed and who is before the Court. The Commissioner has power to assess a “taxpayer”: see 1936 Act, ss 166, 166A, 167, 168, 169, 169AA, 169A, 170. Section 175A of the 1936 Act entitles a “taxpayer” who is dissatisfied with an assessment “made in relation to the taxpayer” to object against it in the manner set out in Part IVC of the Administration Act. A person dissatisfied with an objection decision made by the Commissioner may appeal to this Court against the decision pursuant to s 14ZZ(1) of the Administration Act. A “taxpayer” had formerly been defined by s 6(1) of the 1936 Act to mean “a person deriving income or deriving profits or gains of a capital nature”. The obligation to pay tax under the 1997 Act is now determined by the expression “you”, which applies to entities generally. Section 4-10 of the 1997 Act provides that “you” must pay income tax worked out by reference to your taxable income.

19 The assessments were not in form addressed to the individual partners of RCF IV and RCF V. The assessment in respect of RCF IV was addressed as follows:

Resource Capital Fund IV LP

Maples Corporate Services Ltd

Ugland House South Church Street

PO Box 308

Cayman Islands

The assessment in respect of RCF IV was sent by the Commissioner under cover of a letter dated 25 March 2013 addressed to the General Partner of RCF IV as follows:

The General Partner

Resource Capital Fund IV LP

Maples Corporate Services Ltd

Ugland House South Church Street

PO Box 308

Cayman Islands

The Commissioner’s letter described the subject matter of the letter as “Resource Capital Fund IV LP (Tax File Number 940 862 980) Assessment regarding disposal of taxable Australian property” and referred throughout to the intended recipient as “you” and informed the recipient described as “you” of having obligations to pay tax and of having rights of objection and appeal. An assessment in similar form, under cover of a letter similarly addressed, was sent by the Commissioner in respect of RCF V. The objections in each case were on forms approved by the Commissioner and identified the taxpayer in each case by reference to the name of the partnership and the applicable tax file number of the partnership. The form was accompanied by a document headed “Notice of objection against assessment” giving the name of the taxpayer as the partnership. The two proceedings in this Court were commenced in the name of the partnerships, rather than in the individual names of the partners, although, as mentioned, leave was given at a directions hearing for the General Partner in each proceeding to be added as an applicant, although, arguably, that might not have been necessary if the applications were made by the partners in their partnership name as contemplated by r 9.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

20 The applicants submitted at the hearing that the assessments, although in form addressed to limited partnerships, were to be read as addressed to the partners and that the covering letters addressed to the General Partner were to be read as addressed to the General Partner on behalf of the partners. The applicants, therefore, did not challenge the validity of the assessments because of the form in which they had been addressed, and the Commissioner did not challenge the competency of the proceeding in this court nor, of course, concede that the assessments were invalid if they were to be taken to be addressed to the limited partners of the relevant partnerships.

21 In Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Prestige Motors Pty Ltd (1994) 181 CLR 1 the High Court held that it was essential to the validity of a notice of assessment that it state the name of the taxpayer who is liable to pay the tax, and that a notice addressed to a nominated trust purporting to state the tax payable was prima facie to be understood as directed to the trustee in whom the trust assets were vested. In that case an assessment had described the taxpayer as “Prestige Toyota Trust” rather than as the trustee who was liable to pay the tax assessed. The High Court in a joint judgment, however, rejected the taxpayer’s argument that the notice of assessment was required to state the name of the taxpayer as part of the particulars of the assessment saying at 14-15:

The weakness of the respondent’s argument and, conversely, the strength of the Commissioner’s argument, is that the provisions of the Act require, not that the name of the taxpayer be stated in the notice, but that the notice be served “upon the person liable to pay the tax” (s. 174(1)). The Full Court did not regard this as a decisive consideration. That was because Hill J. concluded that s. 177(1) would fail in its purpose unless the reference to “all the particulars of the assessment” in the subsection included the name of the taxpayer. The purpose which his Honour attributed to the subsection was to avoid the need in recovery proceedings for the Commissioner to prove that the taxpayer had a particular taxable income or net income in the case of a taxpayer trustee, or to debar the taxpayer from contesting that the amount of the taxable or net income as shown in the notice was the taxpayer's income or that tax was payable thereon. However, s. 177(1) does not require that the notice state the name of the taxpayer. Furthermore, s. 177(1) is a facultative provision; if the notice does not fall within the subsection, the only consequence is that the Commissioner cannot rely upon the provision.

This leads us to the conclusion that it is not essential to the validity of a notice of assessment that it state the name of the taxpayer liable to pay the tax. But we do not consider that this conclusion is a complete answer to the question which has arisen. That is because, on the view which we take of the provisions, it is necessary that the notice should bring to the attention of the person on whom it is served that the assessment to which it relates is an assessment of that person to tax. The principal purpose of the notice of assessment is to bring to the attention of the person on whom it is served that such person is liable to pay on the due date the amount of tax assessed in the notice on the income stated in the notice. No doubt service of the notice on a taxpayer goes some way towards achieving this purpose. But whether the purpose is achieved in a given case must depend upon the form and contents of the particular notice of assessment. Thus, to take an example given by Hill J. in the Federal Court, a notice assessing A to tax but served on B instead could not stand as a notice assessing B to tax.

(Footnote omitted.)

The assessments and the other procedural steps taken in this proceeding should similarly be understood as assessments to, and as steps undertaken by, the partners by reference to their partnership name. That is consistent with s 94V(1)(a), which in terms expressly imposes obligations “on each partner” that otherwise “would be imposed” on the partnership. The express effect of s 94V(1)(a) is for the income tax laws to apply by the individual partners having the obligations which would otherwise have been imposed upon the partnership. There is no reason in the text or policy of Division 5A when read alone, or when read in the context in which it is found, to exclude from those obligations the liability to pay tax. Indeed, the natural meaning of the words in s 94V(1)(a), in the context of Division 5A, and in the context of the income tax law (as defined for the purpose of s 94V by s 94B), or by reference to policy or interpretative history, requires the inclusion of tax liabilities by assessments amongst the obligations which are made by the section to fall upon the partners “instead” of the partnership. This view also gives effect to modifications to the Administration Act effected by the definition of “income tax law” in s 94B which includes the objections and appeals provisions under Part IVC, and accommodates the power to object which is given by s 175A of the 1936 Act. The fact that the proceedings in this Court were commenced in the name of the partnership, as previously mentioned, is contemplated by r 9.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) and, if there were any doubts, the General Partners have been added as applicants to the proceedings.

22 The applicants’ submissions, however, do not fit entirely consistently with their notices of objection or their appeal statements. The written, and oral, submissions at the hearing were based upon the proposition that the partners were the relevant taxpayers and that the partnerships were not separate taxable entities, but the formal documents preceding the written and oral submissions were not so explicit. The notices of objection and appeal statements read more consistently with the proposition which had been assumed in RCF III that the limited partnership was a separate taxable entity. Thus, for example, the notice of objection for RCF IV identified the taxpayer as the partnership, and in paragraph 3.1 referred to the taxpayer as “a Cayman Islands partnership” in contra distinction to the limited partners of the taxpayer, who in paragraph 3.2 were described as US residents. The tension between the case as argued and the objections as lodged can be seen from paragraph 3.3 of the notice of objection which referred to the taxpayers as the partnerships and distinguished the taxpayer from the partners. Paragraph 3.3 stated:

Consequently, it is the limited partners not the Taxpayer that Australia is authorized to tax under the [United States Convention].

The applicants’ case in the proceeding, however, was that the applicants, that is that the taxpayers, were the partners of the partnership who claimed directly the relief available under the United States Convention although the grounds of objection may not have been entirely consistent with that case. Section 14ZZO of the Administration Act limits an appellant to the grounds stated in the taxation objection to which the decision relates unless the court otherwise orders. No application was made in either proceeding to amend the grounds of objection, but the Commissioner did not object to the arguments which were maintained on behalf of the applicants in their written and oral submissions, nor did the Commissioner contend that the applicants’ arguments did not come within the objections or the appeal statements. It is possible, however, to construe, and these reasons assume, that the notices of objection were made by the limited partners upon the basis that the references to the taxpayer in the notices of objection are to be understood, when context requires, as references to the individual limited partners and at other times to the limited partnership as apparently defined. I would, in any event, otherwise give leave for the grounds of objection to be amended for them to conform with the submissions. The parties will be heard after publication of these reasons on whether any formal orders may need to regularise, or otherwise deal with, this aspect of the proceedings.

23 The applicants submitted that a consequence of the partnerships not being taxable entities was that those members of the partnership who were residents of the United States (and who are taken to be the taxpayers who have been assessed and are taken also subsequently to have objected and to be the applicants in these proceedings), were entitled to relief from taxation liability by reason of Article 7 of the United States Convention or by reason of the Commissioner being bound by Taxation Determination 2011/25 (“the Ruling”) in its application to Article 7. The issue is of considerable commercial importance both to the applicants and to others involved in international investment in Australia because the partnerships were established as a means of attracting private equity investment from the United States. The bulk of the investors in the respective RCF partnerships were US residents who had invested as partners in specific investment funds with a common corporate structure. The decision in RCF III had been based upon the premise, as mentioned, that the corporate limited partnership was a taxable entity for Australian tax purposes and that it, as had been found at first instance by Edmonds J, was a resident of the Cayman Islands and not of the United States of America. In these proceedings, in contrast, the applicants contended that the corporate limited partnerships were not separate taxable entities but that the partners of the partnership were the taxable entities of which 97% were residents of the United States of America able to claim the relief under Article 7 of the United States Convention.

24 The Commissioner submitted that the applicants could only rely upon any restriction upon Australia’s rights to tax under the United States Convention, or upon the effect of the Ruling, if the profits from the sale by the applicants of their shares in Talison Lithium in March 2013 was not otherwise ordinary income from an Australian source within the meaning of s 6-5 of the 1997 Act. The relationship between the Australian domestic taxing provisions and the effect of international agreements is both complex and fundamental. The tax imposed under Australian law is, of course, imposed by domestic legislation but it reflects international agreements by which taxing rights are allocated in bilateral international agreements between taxing authorities. Domestic taxation occurs in the context of international agreements between sovereign countries in which taxing rights are allocated and restricted. Taxation by reference to residence and source is fundamental to many international agreements and to the Australian tax system: see S. Barkoczy, Foundations of Taxation Law (Oxford University Press, 9th edition, 2017) [9.1]. International agreements are formally given domestic force of law in Australia by their incorporation into Australian domestic law.

25 Section 6-5(3) of the 1997 Act provides that the assessable income of a foreign resident includes the ordinary income derived by the foreign resident from all Australian sources. Section 6-5(3) provides:

(3) If you are a foreign resident, your assessable income includes:

(a) the ordinary income you derived directly or indirectly from all Australian sources during the income year; and

(b) other ordinary income that a provision includes in your assessable income for the income year on some basis other than having an Australian source.

The application of this provision, and the impact of the United States Convention, and of the Ruling, requires consideration of the nature of the gain made by the partners and whether it was from an Australian source.

26 Each of the RCF IV and RCF V partnerships had one General Partner which had unlimited liability. Each also had limited partners who provided the investment capital to the partnerships. The General Partner of RCF IV was Resource Capital Associates IV LP (“the RCF IV General Partner”) and the General Partner of RCF V was Resource Capital Associates V L.P. (“the RCF V General Partner”). The General Partners of RCF IV and RCF V were responsible for the management and control of the partnerships and determined the form of investments. Each of the partnerships entered into a management agreement with RCF Management LLC (“RCF Management”) to manage the operations and investments of the partnerships through an investment committee (“the Investment Committee”).

27 RCF Management was a limited liability company incorporated in Delaware and was based in Denver, Colorado in the United States of America. RCF IV and RCV V, however, were established as limited partnerships in the Cayman Islands in accordance with the Cayman Islands Exempted Limited Partnership Law (1997 Revision) (“the ELP Law”). The reasons for this were explained by Mr Brian Dolan who was employed by RCF Management and was its in house legal counsel. Mr Dolan explained that:

10. The applicants were established as limited partnerships incorporated in the Cayman Islands for a number of reasons including:

(a) partnerships, in contrast to corporations, avoid entity-level tax for United States federal income tax purposes;

(b) capital gains earned by a partnership retain their character as capital gains rather than becoming dividend income paid to shareholders;

(c) incorporating the partnership outside the United States of America enables the limited partners to be taxed according to their individual interest determined by their proportionate ownership of the fund - that is, the fund would be “looked through” for the purposes of US revenue law; and

(d) the Cayman Islands imposes no additional tax burden on the fund in addition to its obligations to pay US taxes and allows the fund to be regulated by US securities law.

The treatment of partnerships for US tax purposes was therefore broadly the same as for Australian purposes; that is, that the taxable entities were the partners rather than the association they comprised.

28 RCF IV was formed pursuant to a written partnership agreement dated 7 July 2006 which was executed in Denver in the USA. Clause 2.1 of the RCF IV partnership agreement provided that the partners agreed to carry on an exempted limited partnership subject to the terms of the agreement in accordance with the ELP Law of the Cayman Islands. The RCF IV General Partner was identified in the RCF IV partnership agreement as the RCF IV General Partner and was a Cayman Islands limited partnership established under the ELP Law of the Cayman Islands which was formed pursuant to a written partnership agreement dated 7 July 2006 as amended and restated on 21 July 2006. The management of the RCF IV partnership was vested in the General Partner pursuant to clause 3.3.1 of the RCF IV partnership agreement. The General Partner of the RCF IV partnership was itself another partnership of which the General Partner was a limited liability company incorporated in Delaware in the United States called RCA IV GP LLC (“RCA IV GP”). RCA IV GP was added as an applicant to the proceeding on 31 August 2016. The RCF IV partnership was comprised of the RCF IV General Partner and 77 limited partners of which the Commissioner agreed 73 were resident in the United States.

29 The RCF V partnership was formed pursuant to a similar written partnership agreement dated 30 March 2009 (“the RCF V partnership agreement”) of which the General Partner was the RCA V General Partner being an exempted limited partnership established in the Cayman Islands pursuant to ELP Law. The General Partner of RCA V General Partner was RCA V GP Limited (“RCA V GP”), being a limited liability company incorporated in the Cayman Islands. The management and control of RCF V was vested exclusively in the General Partner pursuant to clauses 3.3 and 4.1 of the RCF V partnership agreement. RCA V GP was also added as an applicant to the proceedings on 31 August 2006. The RCF V partnership was comprised of a general partnership and 137 limited partners of which the Commissioner agreed 130 were resident in the United States.

30 Clause 4.1 of the RCF IV partnership agreement identified the investment objectives of the RCF IV partnership as follows:

The primary objective of the Partnership is to generate significant returns from investments in the mining and minerals industry (Portfolio Investments). The General Partner, in its sole discretion and subject to clause 4.2, will determine the form of each investment to be made by the Partnership, but it is anticipated that the investments will generally consist of secured and unsecured convertible debt securities, equity or other types of equity-related securities.

RCF Management was retained to provide management services pursuant to a management agreement entered into between it and the RCF IV partnership. Clause 3.1 of the management agreement provided that RCF Management would provide management services as follows:

3.1 Duties of the Management Company. Services to be rendered by the Management Company shall include, without limitation: (i) acting as the Fund’s investment advisor in, and manager of, the investment and reinvestment of the Fund’s assets; (ii) finding, investigating, negotiating and arranging the financing of prospective Portfolio Investments for the Fund; (iii) monitoring, reviewing, and assisting in the creation of value of, such investments; (iv) helping to realize values for the Fund by providing assistance in the sale, merger, initial public offering of, or other exit strategy for, Portfolio Companies; (v) advising as to the administration and/or management of the Fund; (vi) rendering investment research services, advice and supervision to the Fund; (vii) furnishing all administrative services to the Fund; (viii) providing the services of its members, officers and employees as directors, consultants and advisors for the Fund and Portfolio Companies; and (ix) otherwise providing assistance within the areas of expertise of its members and staff. In addition to the services of its own members and staff, the Management Company shall arrange for and coordinate the services of other professionals and consultants. The services to be rendered by the Management Company to the Fund under this Agreement are not to be deemed exclusive and, subject to limitations set forth in the Fund Partnership Agreement, the Management Company shall be free to render similar services to others. The services to be provided by the Management Company to the Fund as specified in this Section 3.1 are referred to as the “Services.”

RCF Management entered into an agreement with Resource Capital Funds Management Pty Ltd (“RCF Management (Aust)”) for the latter to provide administrative and management services to RCF Management for a fee equal to its cost plus a margin for administrative services. RCF Management (Aust) was a company incorporated in Australia with between 11 to 14 employees who had Australian residential addresses between 2007 and 2011, including Mr James McClements, Mr Ian Burvill, Mr Christopher Corbett and Mr Mason Hills.

31 The RCF IV partnership agreement and the RCF V partnership agreement both contemplated that the General Partner would have an Investment Committee to make the investment and divestiture decisions of the partnership. Between January 2007 and 25 March 2013 the Investment Committee was made up of Mr James McClements, Mr Hank Tuten, Mr Ryan Bennett, Mr Russ Cranswick, Mr Brian Dolan (until 30 June 2011), Mr Ian Burvill (until 1 March 2008), Mr David Thomas (from 30 April 2012) and Dr Ross Bhappu. Four of the six members of the Investment Committee between 23 April 2007 and 31 December 2011 lived in the United States of America and the evidence of Mr Dolan was that all of the meetings of the Investment Committee during the period that he was a member were chaired by a member who was present either in Denver, Colorado or elsewhere in the United States.

32 Dr Bhappu tendered evidence of examples of information given to investors which explained how RCF invested and monitored the progress of the investments on behalf of the partnerships including RCV IV and RCF V. The typical business activities were planned to include the active investment by RCF Management in companies and businesses in which the RCF partnerships invested. A paper prepared in 2009 of frequently asked questions and answers explained the business activities as follows:

Discuss how the Fund will monitor portfolio investments. Are there specific individuals dedicated to monitoring investments?

RCF typically remains actively involved with portfolio investments through participation on Board of Directors or by actively working with a company’s management team. The Partner or Principal responsible for sourcing the investment will typically remain involved with the investment from sourcing through to exit.

What methods if any do you use to detect early problems that may be developing in your investments?

RCF management team members sit on the boards of directors of most core portfolio companies in which a substantial investment has been made. As a director, potential problems are recognized at a very early stage and can be mitigated to the extent possible. Typically, the problems require expertise within the company that it may be lacking. RCF has been instrumental in introducing new management and expertise to portfolio companies to assist them in growing and advancing their projects. All investment companies are required to provide monthly or quarterly reports. Regular visits to each company and its projects are also undertaken.

In what situations would your firm insist on replacing the current management team at a portfolio company? How would you go about doing this?

RCF replaces or enhances management and boards of portfolio companies as required on a regular basis. Typically these changes are due to the existing team simply not having the required expertise. Changing or enhancing management teams is not uncommon and is usually done in a friendly manner where the existing portfolio company management team recognizes their limitations. Quite frequently, RCF as part of the terms and conditions for investing will require certain management team changes or additions to augment the existing team.

In extreme cases, RCF will work with other major shareholders to force a change.

Describe your post-investment monitoring process. How frequently are you in contact with company management?

An RCF management team member is typically appointed to the Board of Directors of the portfolio company. In this role, the manager is intimately involved in the company and is in weekly contact with the company's management. The manager reports to the Investment Committee on a regular basis and discusses the investment with the broader management group at work-in-progress meetings as well as formal reporting on a quarterly basis.

What percentage of portfolio companies do you plan on obtaining Board seats? What percentage of portfolio companies do you plan on obtaining Board observer status?

Board seats are taken on all core investments. Board seats are typically not taken on portfolio companies in which small strategic equity investments are made.

The business activities typically also included contemplation of the subsequent disposal of the assets acquired by the partnerships. The 2009 paper described this in the context of the exit strategies which were explained to the partners as follows:

Describe the various exit strategies you plan to use. What type of market conditions would make it difficult to execute these strategies?

The Fund's exit strategies are anticipated to follow the pattern established in the predecessor RCF Funds and will generally involve one of the following alternatives:

• Takeover of the company by another industry participant -trade sales.

• Selling equity positions into the market (secondary sales) or to large institutional buyers on a negotiated basis.

• Listing of investments on public markets (IPO's), primarily the Toronto Stock Exchange (“TSX”), the Australian Securities Exchange ("ASX") and the Alternative Investments Market in London (“AIM”). Full or partial exits may occur at the time of listing.

• Repayment of convertible debt by the company. Often the repayment of debt involves negotiations on timing and results in a small residual equity interest, which is then sold.

It is interesting to note that even in the very early years (1998-2002), during a period of low commodity prices; RCF was still able to exit approximately 20% of its portfolio holdings on an annual basis.

The 2009 paper was prepared for the RCF V partnership but Dr Bhappu agreed that the description applied also to the RCF IV partnership. In oral evidence Dr Bhappu agreed with the description of the business activity of the RCF partnerships as being that the investors would “go in, make the investment, improve the performance of the company concerned and then seek to exit within three to six years after that time, having made a profit”.

33 In April 2007 RCF Management considered a possible investment by RCF IV in the Australian tantalum and lithium businesses of Sons of Gwalia Ltd (“Sons of Gwalia”). The employees of RCF Management had begun to watch the progress of the administration of Sons of Gwalia NL since it was put into administration in about August 2004 and Mr McClements had noted at a meeting of the RCF Investment Committee on 9 January 2007 that Sons of Gwalia tantalum was “fairly active”, that an indicative expression of interest had been given on behalf of RCF, and that entities, including Farallon, Fortress and Goldman Sachs, were also interested.

34 Sons of Gwalia NL had for many years been a successful publicly listed company with a market capitalisation in excess of A$1 billion at its peak. The assets included a specialty minerals division which in 2007 were being managed by the administrators on behalf of the creditors. On 2 April 2007 an Investment Committee paper was prepared for a possible investment by the RCF IV partnership “[t]o approve the provision of a financing facility to enable the tantalum/lithium assets of Sons of Gwalia (administrators appointed) to exit the administration process and to begin operating as a standalone company” to be called Talison Holdings Ltd. The Investment Committee paper of 2 April 2007 proposed the participation by RCF IV in a consortium with Goldman Sachs, Fortress and Farallon to provide debt facilities in an amount of A$145 million to enable Talison Holdings Ltd to operate independently. On 3 April 2007 the Investment Committee met to consider the paper and the minutes recorded that Mr Tuten participated by telephone from Sydney, that Mr McClements and Mr Burvill each participated from Perth, (with Mr McClements participating by video and Mr Burvill participating by telephone), that Mr Burnett participated from Montrose by telephone, and that Messrs Cranswick, Bhappu and Dolan participated from Denver by video conference. Others participating in the meeting by invitation by video conference from Perth included Mr Peter Nicholson, Mr Mason Hills and Mr Graham Smith. During the meeting it was remarked that the facility was seen by RCF as a “loan to own” strategy giving RCF a very strong secured position and a chance to own the business if Talison Holdings Ltd did not operate as expected. The Investment Committee voted unanimously in favour of the proposal and approved the transaction.

35 On 23 April 2007 the Investment Committee met again to consider a supplementary paper prepared for the proposed investment by RCF IV. The form of the proposed investment had by then changed from one of refinancing to an acquisition of the assets of Sons of Gwalia through a company to be newly formed by a consortium constituted by Fortress, Farallon, Goldman Sachs and RCF IV. The proposal at that time was that the consortium would capitalise and finance a new holding company to enable it to make an offer to the administrators to acquire the tantalum/lithium assets of Sons of Gwalia for an amount of US$150 million on an enterprise value basis. Under this proposal RCF IV was to invest an amount of up to US$51,750,000 and to assume a contingent liability of A$9 million to assist in financing the acquisition of the assets on the terms contemplated by the supplementary paper which was considered by the Investment Committee. The Investment Committee met at 4.10 pm MDT with Messrs Bennett, Bhappu and Cranswick again participating from Denver by video conference, Mr Dolan participating from Buenos Aires by telephone conference, Mr McClements participating from Perth by video conference and Mr Tuten participating from Sydney by telephone conference. Mr Burvill was absent from the meeting but by invitation Ms Sherri Croasdale participated by telephone conference from New York, Mr Graham Smith participated from Perth and Mr Jasper Bertisen participated from Denver. The Committee unanimously approved the investment which had been proposed in the supplementary Investment Committee paper but did not consider any particular exit strategy. Dr Bhappu’s evidence was that a possible exit strategy was not considered at that time because the investment was intended to be for an indefinite period, but his evidence was not that the investment was intended to be a permanent holding of interests in the company. His evidence that an exit strategy was not considered at the April 2007 meeting was not that there had been a change in business strategy of the RCF partnerships which Dr Bhappu had agreed in evidence to include an ultimate realisation of profit by disposal.

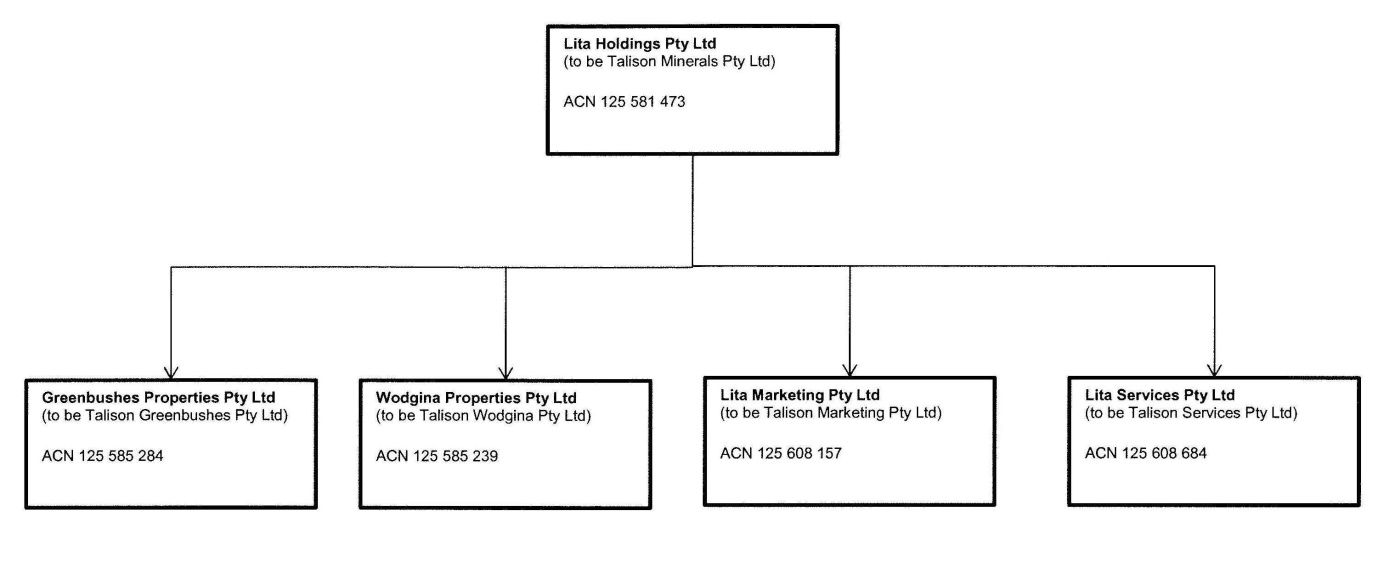

36 On 24 May 2007 Lita Holdings Pty Ltd (“Lita”) was incorporated as the vehicle for the consortium to acquire the lithium and tantalum businesses of the Sons of Gwalia. Lita subsequently changed its name to Talison Minerals Pty Ltd (“Talison Minerals”) on 28 August 2007. On 7 June 2007 Lita entered into a shareholders’ deed (“the shareholders’ deed”) with the consortium made up of RCF IV, Goldman Sachs JB Were Capital Markets Limited, DBSO DU II LLC (a Fortress entity), Mineral Investors LP (a Farallon entity) and Triumph II Investments (Ireland) Limited (a Triumph entity). The corporate structure of Lita as at 8 June 2007 may be shown diagrammatically as follows:

The shareholders’ deed between the consortium members and Lita governed the relationship between the consortium members as shareholders of Lita, and required each member of the consortium to subscribe for a certain number of shares in Lita. The shareholders’ deed was signed by Ian Burvill in Perth on behalf of the RCF IV partnership which was described in the execution provisions as “Resource Capital Fund IV LP, By Resource Capital Associates IV LP, GP, By RCA IV GP LLC”. The funds necessary to purchase RCF IV’s shares in Lita were paid from RCF IV’s account between 23 July 2007 and 30 July 2007 from RCF IV’s bank account with Silicon Valley Bank located at 3003 Tasman Drive, Santa Clara, California, USA. The shareholders’ agreement provided that the RCF IV partnership would hold 32,500,000 shares in Lita on the subscription date, representing 65% of the shares. On 7 June 2007 Lita also entered into a purchase and sale agreement with others to purchase the “business assets” (as defined) for a consideration of A$171,387,500 of “the advanced minerals mining business carried out by the Seller Group using the Business Assets”.

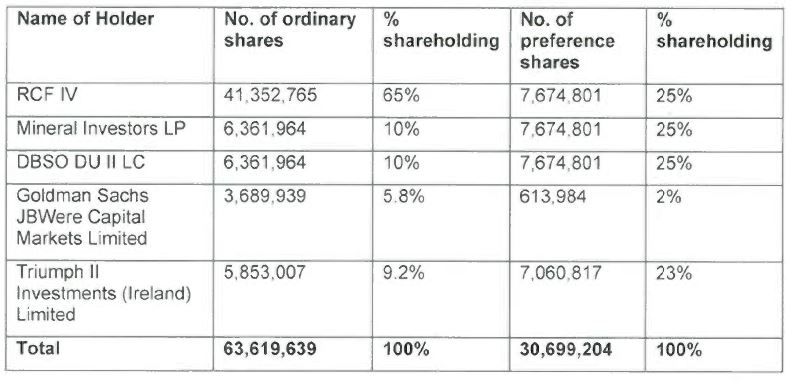

37 Further funding was provided to Lita/Talison Minerals between June 2007 and June 2010 by the members of the consortium by way of debt and equity. On 23 August 2007 the consortium members and Lita executed a deed of amendment to the shareholders’ agreement varying the number of ordinary shares and preference shares that each consortium member was required to subscribe for. Clause 2 of the deed of amendment required each member of the consortium to subscribe for the following number of shares in Lita:

The deed of amendment was signed on behalf of RCF IV in Perth by Mr Mason Hills as General Partner of Resource Capital Associate IV LP as General Partner of RCF IV. Lita issued shares to RCF IV and to each of the consortium members in accordance with its subscription obligations under the deed of amendment. In September 2007 RCF IV subscribed for a further A$9.2 million equity in Talison Minerals. In April 2008 RCF IV subscribed for a further A$9.2 million shares in Talison Minerals, bringing the total equity investment in Talison Minerals to A$59.5 million. In February 2010 RCF IV converted a letter of credit in an amount of US$8.66 million into further ordinary equity in Talison Minerals (which by then was no longer named Lita). The RCF V partnership was created in March 2009 and the limited partner of RCF V partnership also contributed funds by debt and equity in Talison Minerals.

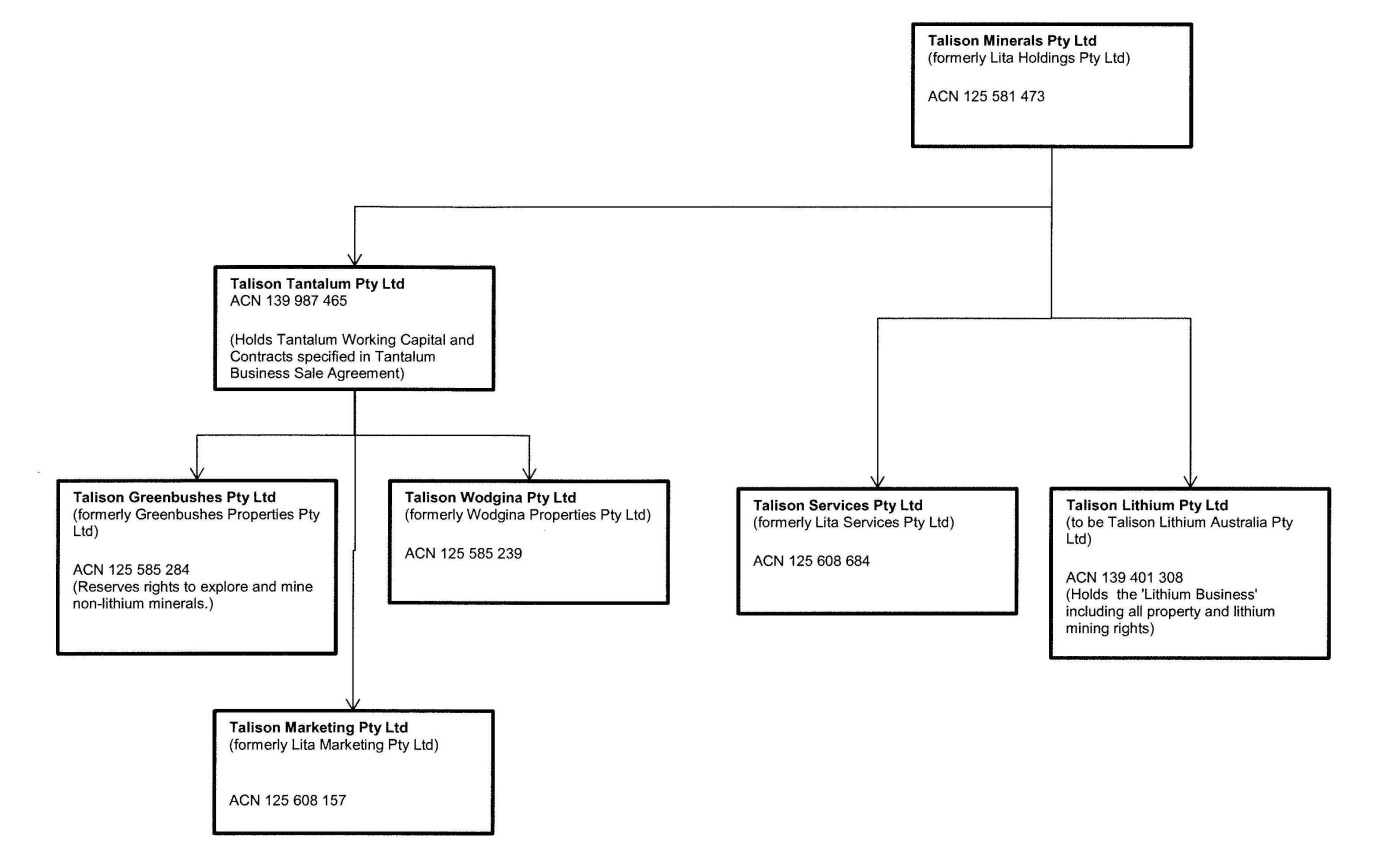

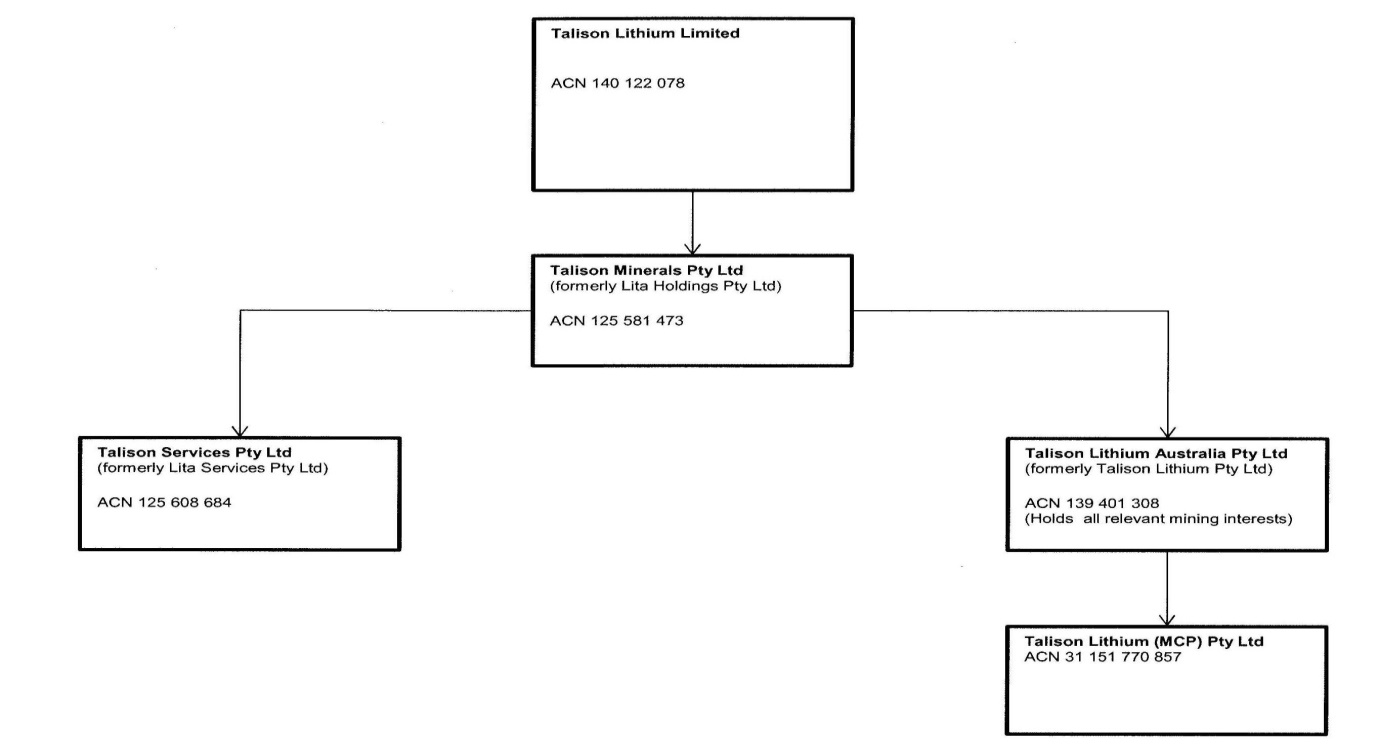

38 Talison Minerals was restructured in November 2009 and its assets were divided between Talison Tantalum Pty Ltd (“Talison Tantalum”) and Talison Lithium Pty Ltd (“Talison Lithium”). Talison Tantalum came to hold the tantalum mining business of Talison Minerals, and Talison Lithium came to hold the lithium mining business of Talison Minerals. The lithium assets of Talison Minerals which had been owned by a subsidiary, namely, Talison Greenbushes Pty Ltd (“Greenbushes”), were sold on 13 November 2009 to a then newly incorporated company called Talison Lithium Australia Pty Ltd (“TLA”) which was a wholly owned subsidiary of Talison Lithium and which, in turn, was wholly owned by Talison Minerals. The corporate structure of Talison Minerals (which had formerly been named Lita) as at 14 November 2009 may be shown diagrammatically as follows:

Under the agreement Talison Minerals transferred rights to certain tenements but reserved (under clause 9) the rights to enter any of those tenements and to explore for and to mine any minerals other than lithium on the terms set out in the reserved rights agreement entered into between Greenbushes and TLA. The non-lithium assets of Talison Minerals were sold on 13 November 2009 to another then newly incorporated company, namely, to Talison Tantalum.

39 On 19 November 2009 Talison Lithium appointed Computer Investor Services Inc (“Computershare Canada”), a Canadian company with its office in the city of Toronto, to act as the branch registrar and transfer agent in connection with the shares held in Talison Lithium, and listed Talison Lithium on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The branch register agreement was to enable holders of shares in Talison Lithium to register and to trade their shares on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The shares held in the name of RCF IV LP and RCF V LP were registered on the Canadian register as at 22 September 2010 and the shares held by RCF IV and RCF V in Talison Lithium continued to be held on the Canadian register so that they could be traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange if necessary.