FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 1

ORDERS

GLAXOSMITHKLINE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD First Applicant GLAXOSMITHKLINE CONSUMER HEALTHCARE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Applicant | ||

AND: | RECKITT BENCKISER (AUSTRALIA) PTY LIMITED Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 8 February 2018, the applicants file and serve a draft of the Orders which they consider appropriately reflect Reasons for Judgment published this day (8 January 2018) by Foster J (GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 1).

2. In the event that it disagrees with the applicants’ proposed Orders, by 15 February 2018, the respondent file and serve a draft of the Orders which it considers appropriately reflect the said Reasons for Judgment.

3. Each party may support its draft with a written submission of no more than three (3) pages in length.

4. The form of relief to be granted in order to give effect to the said Reasons for Judgment be determined on the papers after 15 February 2018.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

FOSTER J:

1 The applicants, GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd and GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (together, Glaxo), have for some considerable time marketed and sold, and continue to market and sell, a suite of over-the-counter (OTC) pain relief medications under the product name “Panadol”. The active ingredient in all Panadol products is paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen).

2 Until 7 September 2015, the first applicant was the entity which marketed and sold Panadol-branded products in Australia. Since 7 September 2015, those activities have been conducted by the second applicant.

3 Both applicants claim the relief specified in their Fast Track Originating Application filed herein on 11 September 2015 (Application).

4 The respondent, Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Limited (Reckitt), also markets and sells a brand of OTC pain relief medication under the product name “Nurofen”. Reckitt supplies a number of different products under the Nurofen product name. The active ingredient common to all Nurofen products is ibuprofen.

5 In August 2015, Reckitt commenced a comparative advertising campaign (campaign) in which it compared Nurofen and ibuprofen with Panadol and paracetamol. Glaxo alleges, amongst other things, that, in that campaign, Reckitt represented that:

(a) Nurofen is better than paracetamol for common headaches.

(b) Nurofen gives faster pain relief more effectively for common headaches than does paracetamol.

(c) Nurofen is better than Panadol for common headaches.

(d) Nurofen gives faster pain relief more effectively for common headaches than does Panadol.

(e) Nurofen and ibuprofen perform in a superior manner to Panadol or paracetamol in delivering pain relief for headaches including tension-type headaches (TTH).

6 Glaxo contends that, at the time when Reckitt’s campaign was conducted, there was no adequate foundation in scientific knowledge for the representations which Reckitt is alleged to have made during its campaign. As a consequence, Glaxo claims that Reckitt has engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) and has made false representations in contravention of s 29(1)(a) and s 29(1)(g) of the ACL.

7 In its Application, Glaxo claims declaratory relief, a permanent injunction restraining the campaign and the making of claims similar to those made in the campaign, an order for corrective advertising, damages or compensation, interest and costs. It also claims unspecified orders under s 237 of the ACL. No particulars of any specific orders sought under that section were provided. During final address, Glaxo abandoned its claim for an order requiring corrective advertising.

8 This proceeding has quite a history in this Court. That history is recounted in an interlocutory judgment which I delivered on 7 October 2016 (GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1196 (Glaxo No 1)). It is not necessary to repeat that history in these Reasons.

9 On 15 October 2015, I ordered, pursuant to r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011, that all questions of whether there has been any contravention of the ACL and the nature and form of any declaratory and injunctive relief to be granted to the applicants including relief by way of corrective advertising (the separate questions) be determined separately from and prior to all other issues. After the separate questions have been answered and any consequential orders made, the claims for relief which will remain are Glaxo’s claims for pecuniary relief and s 237 orders. These claims will only need to be addressed if Glaxo is successful in the first part of the case.

10 The proceeding was removed from the Fast Track on 3 February 2016 as a result of delays caused by difficulties with an expert witness whom Reckitt had hoped to call at the hearing of the separate questions.

11 On 15 December 2015, Reckitt gave the following undertaking to the Court, namely:

… that, on a without admissions basis, it will:

(a) From 21 December 2015 to the commencement of the hearing, suspend the advertising campaign referred to in paragraphs 3 and 14 of the Amended Fast Track Statement, including, without limitation, all:

(i) Television commercial advertising;

(ii) Printed material including magazine and newspaper articles;

(iii) Point of sale advertising at Woolworths, IGA and Metcash stores;

(iv) Point of sale advertising at approximately 5,200 pharmacies; and

(v) Outdoor advertising;

(b) Use its best endeavours to withdraw:

(i) Point of sale advertising at Coles stores scheduled to commence on 16 December 2015;

(ii) Point of sale advertising at Chemist Warehouse stores scheduled to commence on 4 January 2016.

12 On 9 June 2016, the solicitors for Reckitt gave notice to the solicitors for Glaxo that Reckitt intended to resume the campaign immediately after the commencement of the hearing of the separate questions which, by then, had been fixed to commence on 25 October 2016.

13 This notification provoked the second applicant into filing an Interlocutory Application on 5 July 2016 (Glaxo’s Interlocutory Application) by which the second applicant sought to restrain Reckitt from resuming the campaign until after the Court has determined the separate questions. In Glaxo No 1, I treated these claims for interlocutory injunctive relief as having been made by both applicants.

14 For the purposes of Glaxo’s Interlocutory Application, Reckitt conceded that there was a serious question to be tried or prima facie case in respect of Glaxo’s claims for final injunctive relief made in its Application. As a consequence of that concession, in Glaxo No 1, I did not need to consider whether Glaxo had established such a serious question or prima facie case nor did I need to assess the strength of that serious question or prima facie case (Warner-Lambert Co LLC v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 106 IPR 218 at 239 [97]).

15 By Glaxo No 1, I granted injunctive relief restraining the further conduct of the campaign by Reckitt until the final determination of the separate questions. That interlocutory relief remains in place.

Glaxo’s Case and the Issues for Trial

16 Glaxo’s contentions are set out in its Amended Fast Track Statement filed on 16 October 2015 (AFTS). Its claims for relief are specified in its Application. I have summarised those claims at [7] above.

17 Reckitt’s responses to Glaxo’s contentions are set out in its Fast Track Response to Amended Fast Track Statement filed on 22 October 2015 (Response).

18 At pars 11 to 13 of the AFTS, Glaxo describes its business of marketing and selling its Panadol-branded products and Reckitt’s business of marketing and selling its Nurofen-branded products. Those contentions are all admitted.

19 At par 14 of the AFTS, Glaxo describes the elements of the campaign. It claims that, from at least August 2015, Reckitt undertook an advertising and promotional campaign throughout Australia across different media comprising written materials in the form of Annexures A to E to the Application and also comprising a television commercial a DVD copy of which was tendered in evidence before me and marked as Exhibit B (TVC). The written materials were published in serial publications such as Women’s Health magazine, professional journals including the Australian Journal of Pharmacy and in retail catalogues. Those materials were also deployed in in-store advertising, outdoor advertising and promotional banners. The TVC was broadcast over both free-to-air and subscription television channels. Attached to these Reasons for Judgment and marked as Annexures A to E respectively is a true copy of each of Annexures A to E to the Application.

20 The TVC comprised twelve frames.

21 The first seven frames comprised depictions of a person or, alternatively, a robotic model suffering from a headache with each depiction synchronised with a voice-over comment as follows:

Frame No | Comment |

1 | When you have a headache |

2 | you want fast, effective relief. |

3 | Use Nurofen |

4 | to target headaches |

5 | at the source |

6 | of pain |

7 | fast. |

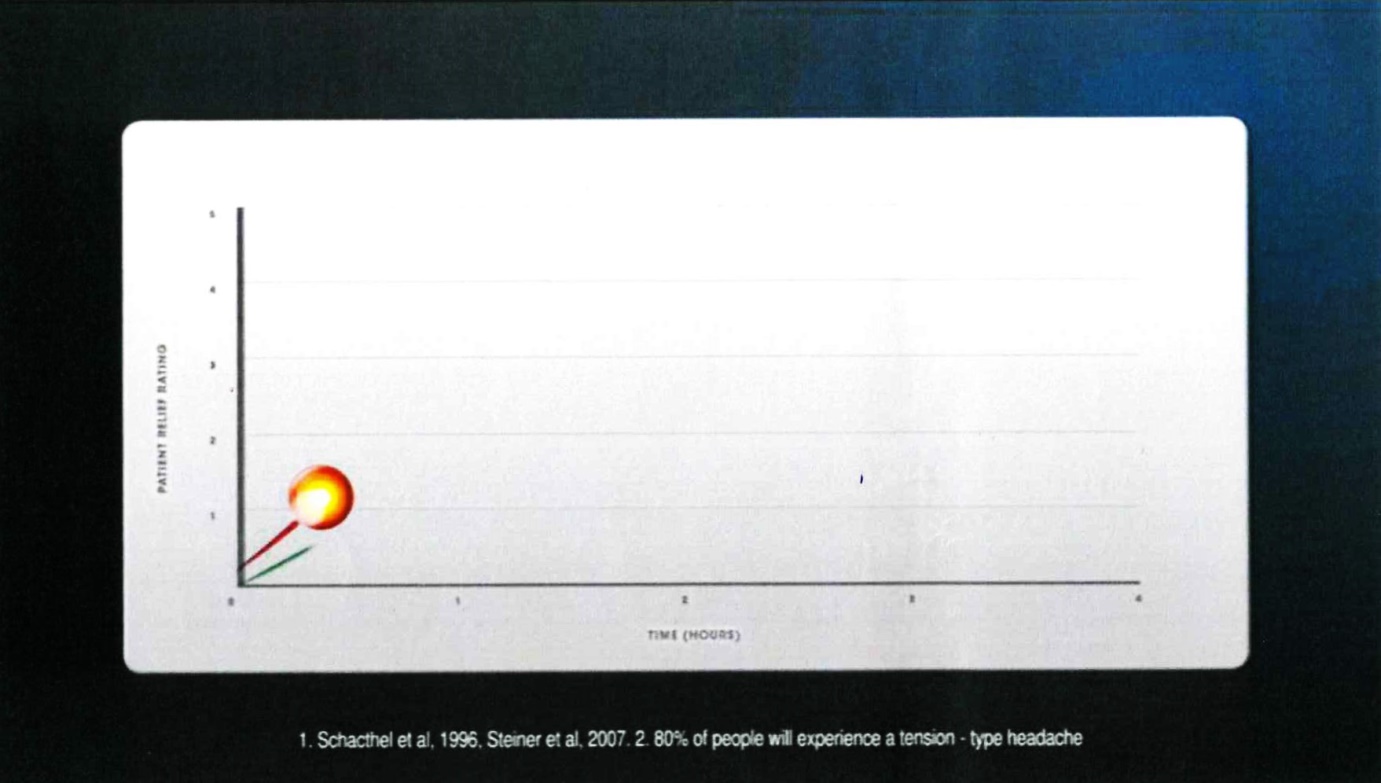

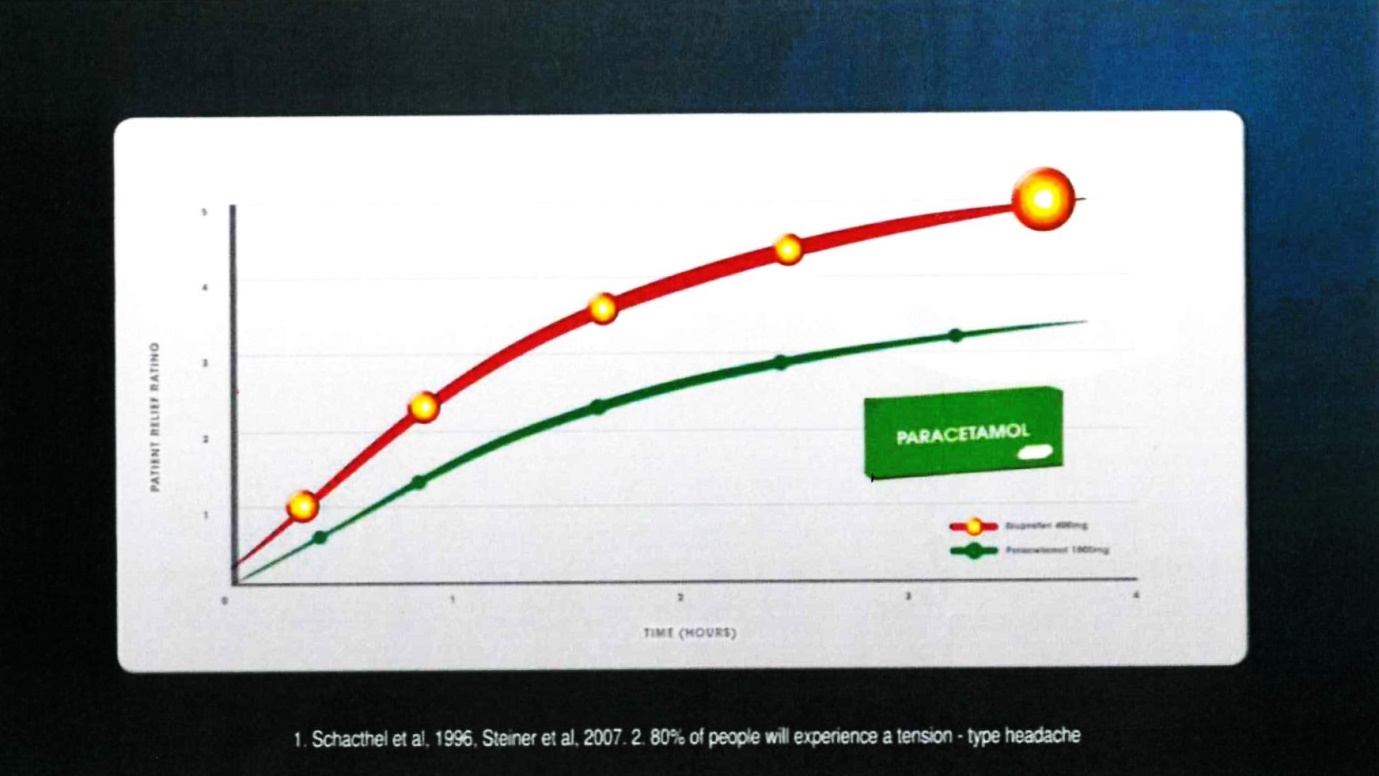

22 Frame 8 comprised:

The voice-over comment accompanying that frame was: “In a clinical study,”.

23 The notes under the graph were in the following terms:

1. Schacthel [sic] et al, 1996, Steiner et al, 2007. 2. 80% of people will experience a tension-type headache

24 Frame 9 comprised:

The voice-over comment accompanying that frame was: “Nurofen was found to be superior to paracetamol”.

25 The notes under the graph were in the following terms:

1. Schacthel [sic] et al, 1996, Steiner et al, 2007. 2. 80% of people will experience a tension-type headache

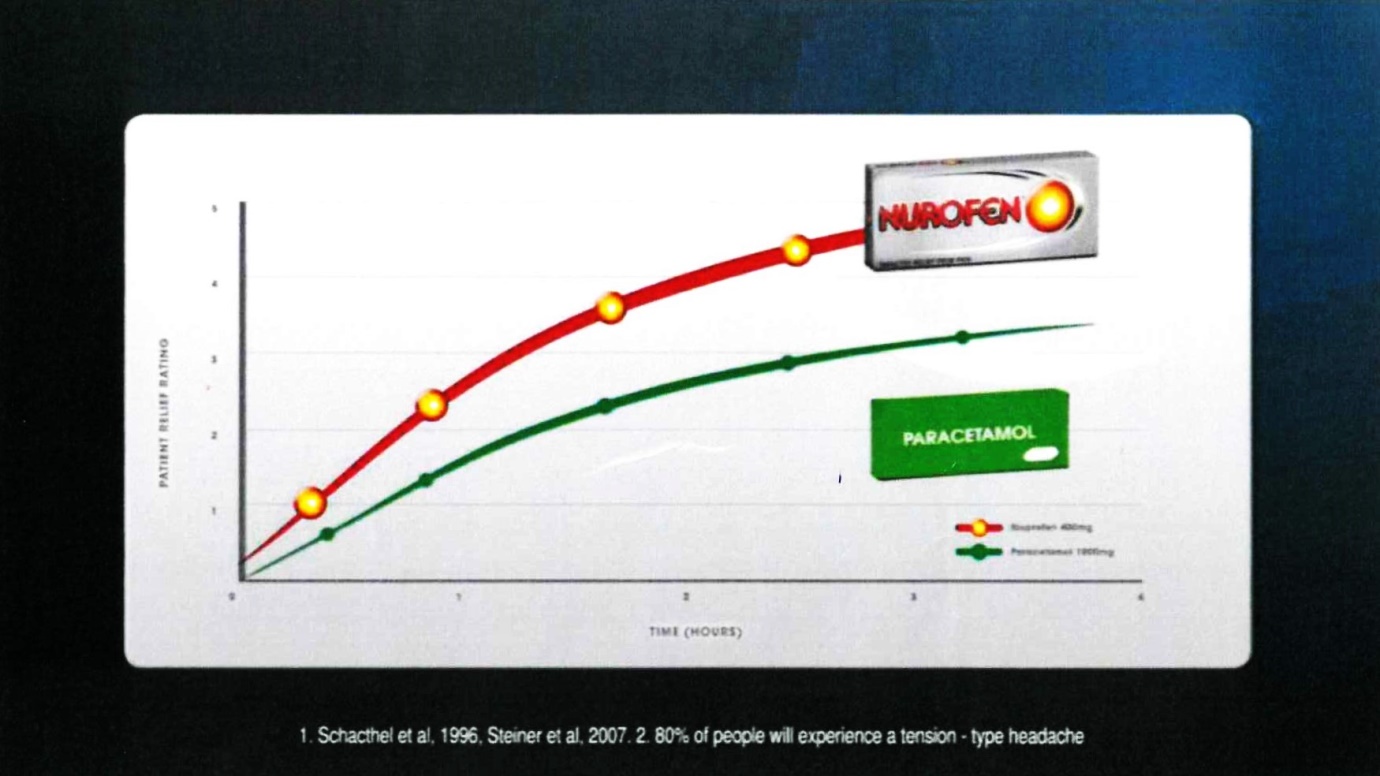

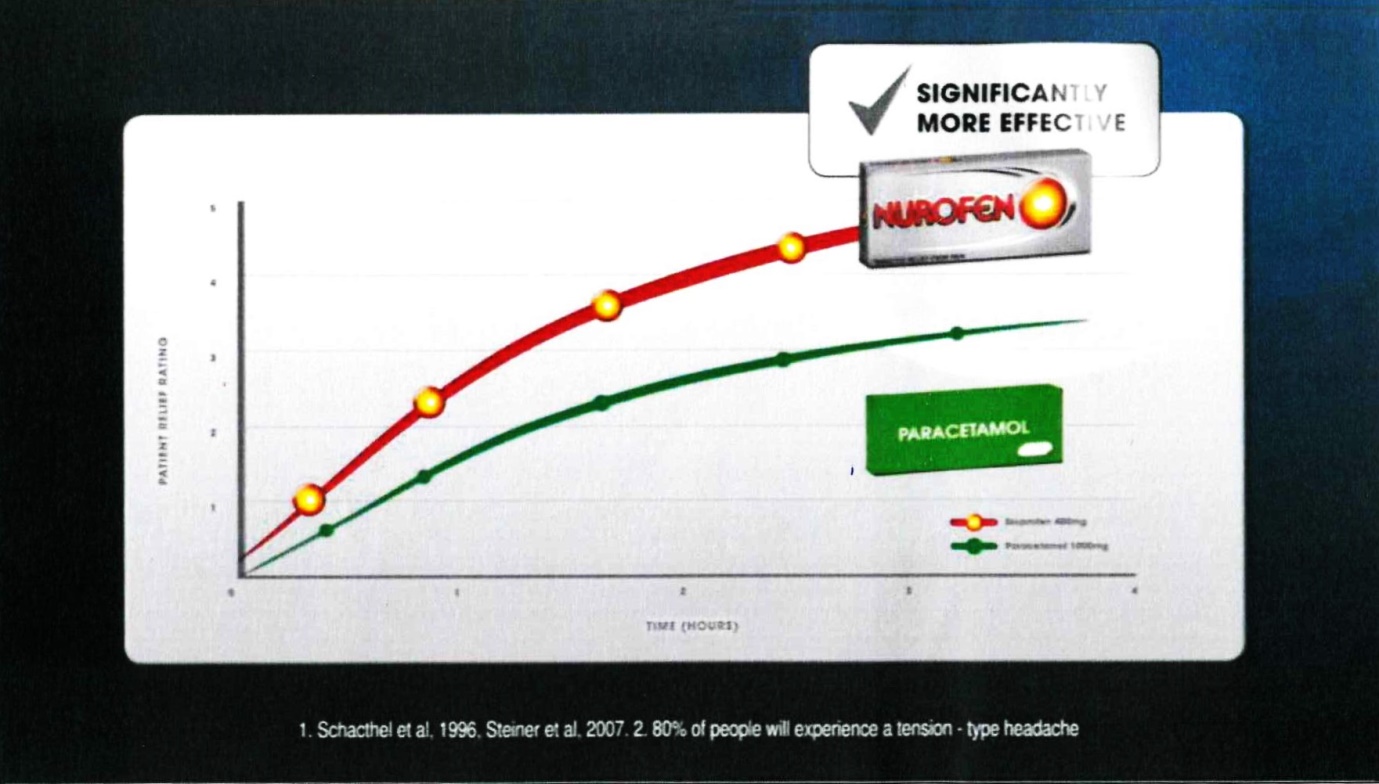

26 Frame 10 comprised:

The voice-over comment accompanying that frame was: “for treating tension-type headaches”.

27 The notes under the graph were in the following terms:

1. Schacthel [sic] et al, 1996, Steiner et al, 2007. 2. 80% of people will experience a tension-type headache

28 Frame 11 comprised:

The voice-over comment accompanying that frame was: “providing more effecting pain relief”.

29 The notes under the graph were in the following terms:

1. Schacthel [sic] et al, 1996, Steiner et al, 2007. 2. 80% of people will experience a tension-type headache

30 Frame 12 comprised:

The voice-over comment accompanying that frame was: “And for faster relief than standard Nurofen, try Nurofen Zavance”.

31 The notes under the graph set out in each of frames 8, 9, 10 and 11 were in the same terms.

32 The note under the packages depicted in frame 12 was in the following terms:

3. Moore et al, 2014, Norholt et al, 2011, Scheler et al, 2007.

33 Glaxo’s descriptions of the elements of the campaign which I have outlined at [19] to [32] above are all admitted by Reckitt in its Response.

34 At par 15 of the AFTS, Glaxo alleges:

In the Respondent’s advertising material, the Respondent has conveyed to Australian consumers any or all of the following representations:

(a) Nurofen is better than Panadol;

(b) Nurofen is superior to Panadol;

(c) Nurofen is better than Panadol for common headaches;

(d) Nurofen is superior to Panadol for common headaches;

(e) Nurofen is better than paracetamol;

(f) Nurofen is superior to paracetamol;

(g) Nurofen is better than paracetamol for common headaches;

(h) Nurofen is superior to paracetamol for common headaches;

(i) Nurofen is superior to paracetamol for tension-type headaches;

(j) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than Panadol;

(k) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than paracetamol;

(l) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than Panadol for common headaches;

(m) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than paracetamol for common headaches.

Particulars

(i) The Respondent’s advertising material in Annexures A B, C, D, E and F conveys a message that “Nurofen” is “better” (or “superior”) to “paracetamol” and, especially, “Panadol”. The terms “better” and “superior” are relevantly unqualified. The comparative connection with Panadol comes about because of the use of images of the Panadol product, as well as through the reputation of Panadol as Australia’s leading brand of paracetamol. The claims of betterness or superiority (including the more particular claims of “faster pain relief” and “more effective”) are reinforced both by the accompanying footnotes (which suggest that there is some scientific basis for the claims) and the graph (which shows the larger, brighter, red and yellow Nurofen line in a dominant position above the smaller, green Panadol line).

(ii) Further particulars may be provided.

35 At par 5 of its Response, Reckitt admits that its advertising materials did, in fact, convey the representations alleged in subpars (c), (d), (g), (h), (i), (l) and (m) of par 15 of the AFTS (the admitted representations). It denies that those materials conveyed the representations alleged in subpars (a), (b), (e), (f), (j) and (k) (the disputed representations). Reckitt argues that, in the campaign, its advertising and promotional activities were directed only to lauding the benefits of Nurofen and ibuprofen as analgesics which deliver pain relief in respect of headaches. Reckitt contends that the representations which it made did not relate to relieving pain caused by other ailments.

36 There is, therefore, an issue as to whether any of the advertising materials deployed in the campaign conveyed any of the following more general representations:

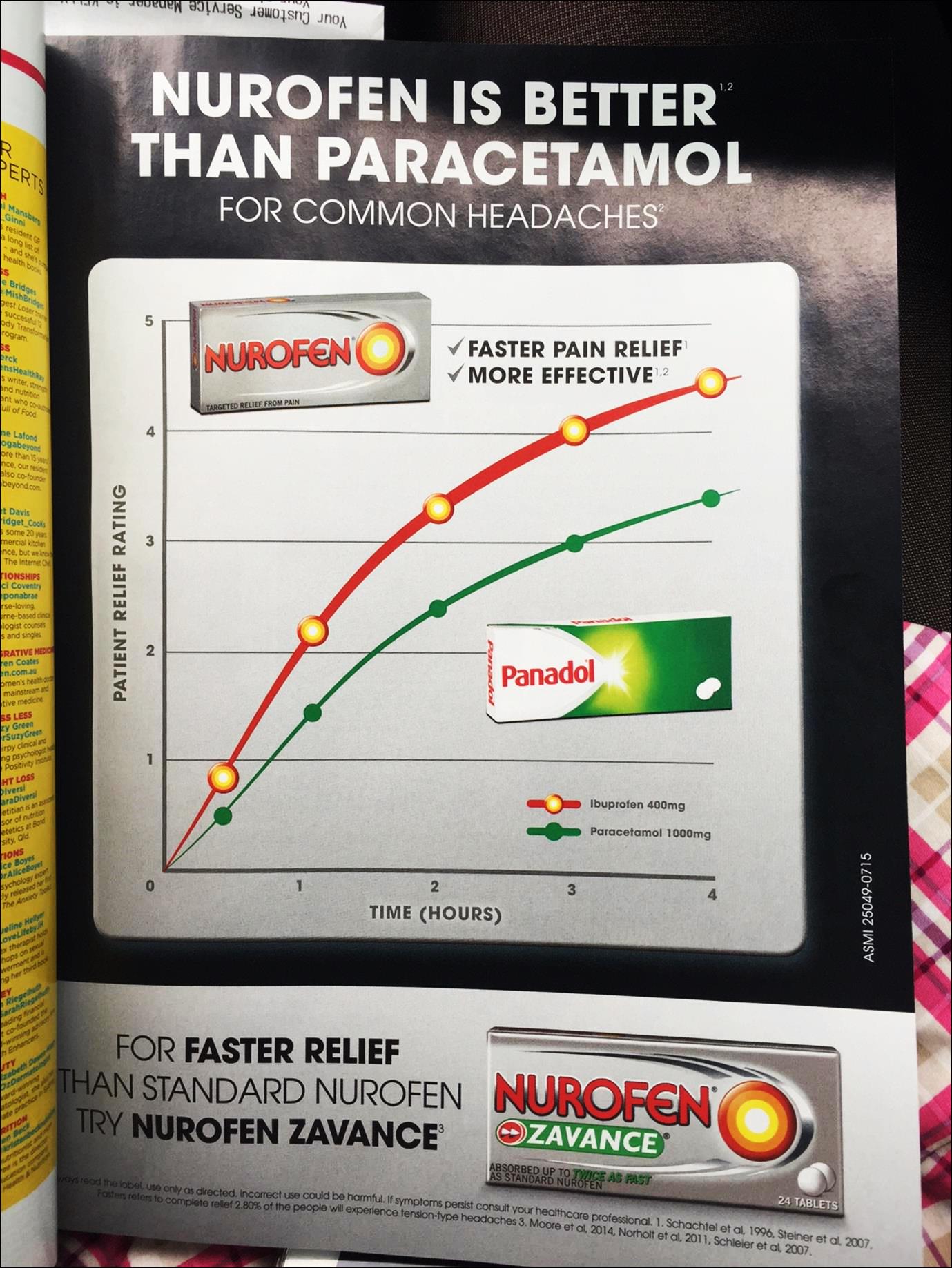

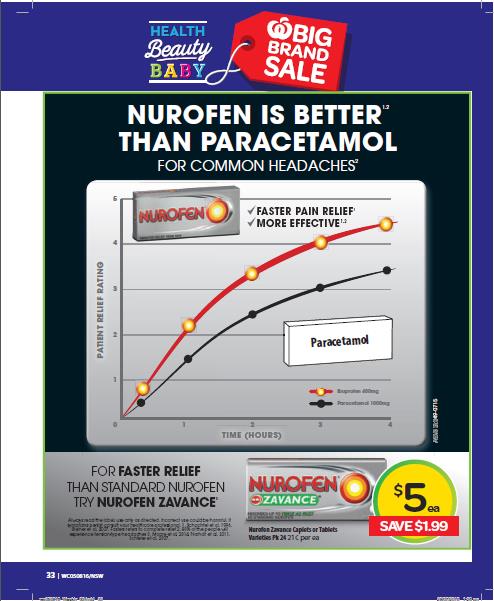

(i) Nurofen is better than Panadol;

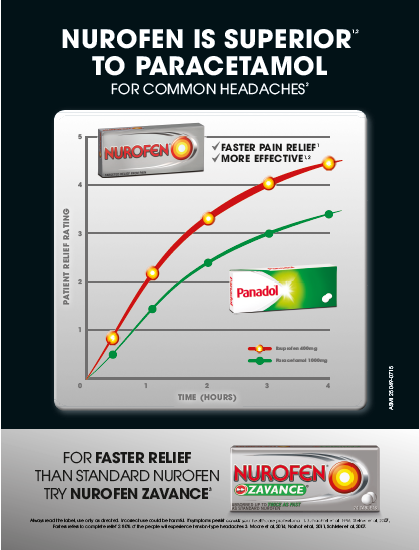

(ii) Nurofen is superior to Panadol;

(iii) Nurofen is better than paracetamol;

(iv) Nurofen is superior to paracetamol;

(v) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than Panadol;

(vi) Nurofen gives faster pain relief and is more effective than paracetamol;

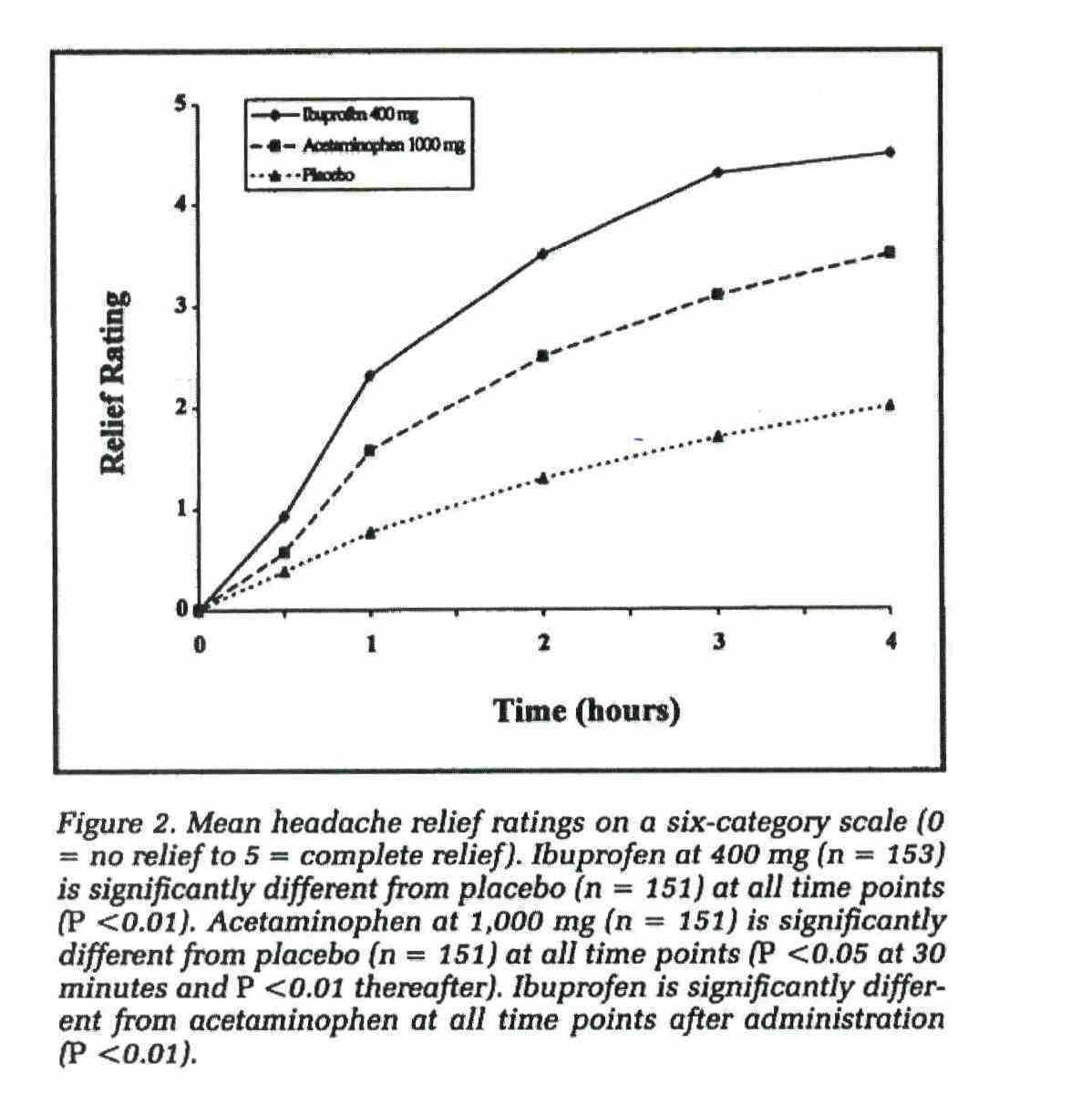

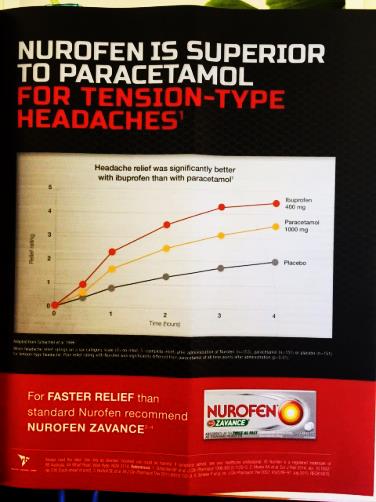

The above representations comprise the disputed representations. Reckitt contends that all of the representations which were made by it in the campaign were confined to representations about relieving pain from common headaches (including TTH) and that none of the representations conveyed by the impugned advertising and promotional materials related to the relief of pain generally or to the relief of pain caused by other conditions or ailments.

37 Paragraphs 15A, 15B, 15C and 15D of the AFTS are in the following terms:

15A In relation to each representation pleaded in sub-paragraphs 15(a) through (m) above (each a Paragraph 15 Representation), a further representation that that Paragraph 15 Representation applies to all or practically all consumers [is made].

15B In relation to each Paragraph 15 Representation, a further representation that there is a current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge for that Paragraph 15 Representation [is made].

15C Each Paragraph 15 Representation is, alternatively, a representation that a consumer who takes the recommended dose of Nurofen will receive a benefit asserted by that Paragraph 15 Representation compared to the benefit that the consumer would receive were he or she to take the recommended dose of Panadol/paracetamol.

15D Each of the representations pleaded in paragraph 15C above is a representation with respect to a future matter, and the Applicants rely on s 4 of the Australian Consumer Law.

38 In answer to the allegations made by Glaxo in those paragraphs, Reckitt:

(a) Does not admit that any of the advertising materials conveyed the additional representation that the claims made therein applied for the benefit of all or practically all consumers in Australia;

(b) Admits that, by publishing the impugned advertising materials, it represented that there was an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge at all times in the period August to December 2015 for the claims which it made in those materials;

(c) Contends that, in respect of each of those representations which the Court ultimately finds was conveyed by Reckitt’s advertising materials, there was, in fact, an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge current at the time when each of them was made;

(d) Denies the allegations made at par 15C of the AFTS; and

(e) Denies that any of the representations alleged in par 15 of the AFTS was a representation with respect to a future matter and thus takes issue with the proposition that Glaxo can rely upon s 4 of the ACL as an aid to proving its case.

39 At par 16 of the AFTS, Glaxo alleges that, at no time during the campaign, was there a current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge for any of the representations alleged in par 15 of the AFTS. Glaxo provided the following particulars of that ultimate contention:

Particulars

(i) The Respondent’s advertising material relies on Schachtel BP, Furey SA, Thoden WR, “Non prescription Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen in the Treatment of Tension-Type Headache” (1996) 36 J Clin Pharmacol 1120-1125. Schachtel did not compare commercially available Nurofen with commercially available Panadol.

(ii) The current body of evidence in relation to the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol for the treatment of tension-type headaches is reflected in at least the following published review: Moore RA, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Straube S, Bendtsen L, “Evidence for efficacy of acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache: methodological critique of randomised trials for oral treatments” (2014) 155 Pain 2220-8;

(iii) The current body of evidence supports the Applicants’ contention that paracetamol and ibuprofen have a similar efficacy in patients with tension-type headache.

(iv) Further particulars may be provided.

40 At par 10 of its Response, Reckitt takes issue with the allegations made by Glaxo in par 16 of the AFTS. It says:

In relation to the matters set out in paragraph 16 of the Statement, the Respondent:

(a) says that there is an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge for the representations made by the Respondent as admitted in paragraph 5 above in its advertising material in Annexures A, B, C, D, E and F to the Statement;

(b) says that the current body of scientific knowledge in respect of the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) is set out in the study authored by Schachtel BP, Furey SA and Thoden WR and published as “Non prescription Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen in the Treatment of TensionType Headache” – (1996) 36 J Cin Pharmacol 1120-1125 (the Schachtel Study);

(c) says that it is immaterial that Schachtel Study “did not compare commercially available Nurofen with commercially available Panadol” because it compared ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) and those are the active ingredients of, respectively, Nurofen and Panadol, as set out in paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Statement;

(d) says that the Schachtel Study established that ibuprofen was superior to paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen);

(e) says that during the course of the submissions made by the parties to both the ASMI Complaints Panel and the Appeal ASMI Complaints Panel (both of those Panels are identified below), the Applicant expressly conceded that the Schachtel Study established that ibuprofen was superior to paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen);

(f) says that the study authored by Moore RA, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Straube S, Bendtsen L and published as “Evidence for efficacy of acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache: methodological critique of randomised trials for oral treatment” – (2014) 155 Pain 2220-8 (the Moore Study) does not represent the current body of scientific knowledge in respect of the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen)

(g) says that:

(i) the Moore Study merely reviewed earlier studies, both published and unpublished;

(ii) the Moore Study identified three studies as providing data of a head-tohead comparison between the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), being the Schachtel Study, a study known as the Packman Study and an unpublished study identified as NL9701;

(iv) the Moore Study reported that the Schachtel Study, was a study of high quality and rated it as 5/5 on the Oxford Quality Scale;

(v) the Packman Study is irrelevant [for] the purpose of considering the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) because it evaluated a liquigel form of ibuprofen;

(vi) the NL9701 Study was not published and was not the subject of peer review and cannot, without more, displace the results set out in the Schachtel Study; and

(iv) the Moore Study did not, in any way, displace the results set out in the Schachtel Study;

(h) says that during the course of the submissions made by the parties to both the ASMI Complaints Panel and the Appeal ASMI Complaints Panel (both of those Panels are identified below), the Applicant expressly conceded that the Packman Study was not a study which could be taken into account for the purpose of considering the comparative efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen); and

(i) otherwise denies the matters set out therein.

41 At par 16A of the AFTS, Glaxo alleges that Nurofen is not suitable for all or practically all consumers in Australia. At par 11 of its Response, Reckitt admits this allegation.

42 Glaxo goes on to allege at par 17 and par 18 of the AFTS that the representations alleged in par 15 of the AFTS were false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive at the times when they were made and thus that, by making those representations, Reckitt contravened ss 18, 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(g) of the ACL. Those allegations are all denied by Reckitt.

43 At par 19 of the AFTS, Glaxo alleges that the contravening conduct is continuing. I interpolate here that, for the reasons explained at [11]–[15] above, the alleged contravening conduct ceased on 15 December 2015.

44 At pars 16 to 28 of its Response, Reckitt raises a defence of preclusion or estoppel against Glaxo in respect of all of its claims for relief made in this proceeding based upon the proposition that the substance of the claims made by Glaxo in this proceeding was rejected by two panels of the Australian Self Medication Industry (ASMI) when raised as the basis of a complaint made by Glaxo to ASMI against Reckitt in November 2014. At the hearing before me, Reckitt abandoned its preclusion and estoppel defences but nonetheless continued to rely upon the facts and circumstances of Glaxo’s ASMI complaint against Reckitt as matters relevant to the disposition of the present dispute.

45 The following issues for trial arise:

(a) Whether, by the advertising materials deployed in the campaign, Reckitt made any of the disputed representations and, if so, which disputed representations were made by it.

(b) Whether any of the advertising materials also conveyed the representation that the claimed benefits or superiority of ibuprofen applied to all or practically all consumers.

(c) Whether any of the representations which are ultimately found by the Court to have been made by Reckitt were with respect to a future matter or future matters and, if so, which.

(d) Whether Glaxo has established that there was no current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge for any one or more of the representations found by the Court to have been made by Reckitt and, if so, for which such representations was there no such foundation in scientific knowledge.

(e) In the event that Glaxo establishes that Reckitt contravened the ACL by conducting the campaign, what relief (if any) should be granted at this stage.

The Relevant Legal Principles

46 At pars 18 to 29 of its Opening Outline of Submissions, Glaxo summarised the relevant legal principles governing the issues calling for determination in the present case. It did so by reference to the judgment of Wigney J in Australian Olympic Committee Inc v Telstra Corp Ltd [2016] FCA 857 at [132]. An appeal from his Honour’s judgment was dismissed. In the course of their Reasons for Judgment (Australian Olympic Committee, Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited [2017] FCAFC 165 at [73]), the Full Court noted that neither party submitted on appeal that his Honour’s summary of the relevant principles was defective in some way. The Full Court was content to proceed upon the basis that his Honour’s summary was correct.

47 Paragraphs 18 to 29 of Glaxo’s Opening Outline of Submissions were in the following terms:

18. Section 18 of the ACL is not limited to misleading and deceptive representations; cf s 29(1). The question is whether the respondent’s conduct, which may include acts, omissions, statements or silence, is misleading or likely to mislead or deceive: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 655 [49] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

19. Conduct is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead a person into error, or to believe what is in fact false. Conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility that it will have that effect: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87-88. It is insufficient for the impugned conduct to only cause confusion or wonderment: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 87 [106] citing the judgment of a majority of the Full Court in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 170; (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 201 (per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ).

20. The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is an objective question of fact that is to be determined on the basis of the conduct of the respondent as a whole viewed in the context of all relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. Viewing isolated parts of the conduct of a party “invites error”: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty (2004) 218 CLR 592 at 625 [109] (per McHugh J); Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 341-342 [102] (per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

21. The question involves the characterisation of the relevant conduct. Evidence that persons have in fact been misled or deceived by the conduct is not an essential element, however, it can in some cases be relevant and material: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198 (per Gibbs CJ).

22. The tendency of the conduct or representation to mislead or deceive is to be considered or tested against the ordinary or reasonable members of the class to whom the representation was made or the conduct directed. The question is whether a substantial, or at least a reasonably significant, number of that class is likely to be misled or deceived: see Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380 at [336]-[342]. The focus on ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class of consumers means, in effect, that possible extreme, unreasonable or illogical reactions can be put to one side.

23. It is not necessary to prove that the respondent intended to mislead or deceive, however evidence of such an intention may constitute evidence that the conduct was likely to succeed in misleading or deceiving, and may make a finding of contravention more likely: Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 at 666 (per Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ).

24. Where the conduct or representation is in the form of an advertisement, the “dominant message” or “general thrust” of the advertisement is important. It is nevertheless important to have regard to the whole advertisement because context is or may be important. It may also be relevant to have regard to the external context in which a consumer is likely to view an advertisement: TPG Internet at 653-655 [45]-[49] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

25. Where the conduct or representation is in the form of words, it would be wrong to fix on some words and ignore others which may provide relevant context and give meaning to the impugned words. It is necessary to have regard to the whole document: Butcher at 638-639 [152] (per McHugh J).

26. While there are no special principles that apply to comparative advertising, factual assertions made by an advertiser must be true and accurate: Gillette Australia Pty Ltd v Energizer Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 193 ALR 629 at 633 [20] per Heerey J, at 640 [43] per Lindgren J and at 654 [91]-[93] per Merkel J.

27. A comparative, as distinct from a unilateral, promotion of a product necessarily indicates that the advertisement is not mere advertising puff, but involves representations of fact which are either true or false: Gillette (at 641 [44] per Lindgren J, referring to the authorities cited at 640 [43]). An advertiser can lawfully compare a particular aspect of its product favourably with the same aspect of a competitor’s product provided the factual assertions are not untrue or misleading half-truths: Gillette (at 634 [22] per Heerey J). See also Stuart Alexander & Co (Interstate) Pty Ltd v Blenders Pty Ltd (1981) 53 FLR 307 at 310 per Lockhart J and Duracell Aust Pty Ltd v Union Carbide Aust Ltd (1988) ATPR ¶40-918 at 49,861 per Burchett J.

28. In assessing the impact of television commercials, the observations of Merkel J in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Optus Communications Ltd (1996) 36 IPR 515 are particularly apposite. Of the advertisements before him in that case, his Honour said:

“They will be seen by the casual but not overly attentive viewer viewing a free-to-air program with only a marginal interest in the advertisements shown between the segments of the program. In that context it will be the first impressions conveyed to that viewer, rather than an analysis of the cleverly crafted constituent parts of the commercial, which will be determinative.”

Telstra (1996) 36 IPR 515 at 523-524; as applied in the context of corrective advertising in Medical Benefits Fund of Australia v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1 at 23 [60] per Stone J (with whom, Moore J and Mansfield J relevantly agreed).

29. It is misleading conduct to make comparative efficiency claims that imply they were made on a scientific basis when, in fact, there is no proper scientific basis for making those claims: see Colgate Palmolive Pty Ltd v Rexona Pty Ltd (1981) 58 FLR 391; 37 ALR 391 per Lockhart J. Further, it can be misleading to make a statement which implies that there is an adequate scientific foundation in scientific knowledge to justify it [when] taken in its context the scientific statement quoted does not provide a proper foundation: Sterling Winthrop Pty Ltd v Boots Co (Aust) Pty Ltd (1995) 32 IPR 361 at 365 per Tamberlin J.

48 In its Opening Outline, Reckitt accepted much of what had been submitted on behalf of Glaxo in its Opening Outline. Reckitt submitted (correctly) that, when the Court comes to assess advertising of the kind under consideration in the present case, it is the dominant message which will be of crucial importance (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73 at 81 [41]).

49 Reckitt also submitted (correctly) that, where claims are made of a scientific nature, proof that there is no scientific foundation or no adequate scientific foundation for those claims may be sufficient to establish that the claims are misleading.

50 In Janssen Pharmaceutica Pty Ltd v Pfizer Pty Ltd (1985) 6 IPR 227, Burchett J said at 234:

It was submitted by counsel for the respondent that the applicant had failed to prove positively that Vermox would not ever produce a migratory reaction in worms, and that a statement could not be said to be false or misleading within s 52 without such proof, there being no onus on the respondent to prove the truth of the statement. Of course it is correct that the onus is on the applicant, but it seems to me that proof that there is no scientific foundation for a statement in the realm of a science may be sufficient proof that the statement is misleading.

This will be so where in its context the statement must be, or is likely to be, taken as implying that there is an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge to enable it to be made; cf Colgate Palmolive Pty Ltd v Rexona Pty Ltd (1981) 37 ALR 391. I think the present is such a case. It is not without significance that the statement is made in a video distributed through pharmacies by a pharmaceutical company professing expertise in the area. The video represents its information as available to one who does research in appropriate libraries, and professes to be “presented as a service to the community by Pfizer” (these words are on the cover of the video, which also contains the sub-title “Worms — Knowledge and Treatment”).

51 In Sterling Winthrop Pty Ltd v Boots Co (Australia) Pty Ltd (1995) 32 IPR 361 at 365, Tamberlin J said:

It can be misleading for a corporation which disseminates information not to put forward sufficient information to avoid the possibility that the recipient may be misled; cf Fraser v NRMA Holdings Ltd (1994) 124 ALR 548; ATPR 41-346 at 42,529–30. It can also, in my view, be misleading to make a statement which implies that there is an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge to justify it when taken in its context the scientific statement quoted does not provide a proper foundation; cf Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd v Rexona Pty Ltd (1981) 37 ALR 391; ATPR 40-242; 58 FLR 391; Duracell Australia Pty Ltd v Union Carbide Australia Ltd (1988) 14 ALR 293; ATPR 40-918; Janssen Pharmaceutical Pty Ltd v Pfizer Pty Ltd (1986) ATPR 40-654.

52 Justice Bennett expressed similar views in Johnson & Johnson Pacific Pty Ltd v Unilever Australia Ltd (No 2) (2006) 70 IPR 574 at 594 [105]:

Unilever has represented to the consumer that the preference exhibited by Holiday Skin users is supported by the “use test”. The study was silent as to the preference of Holiday Skin users under the age of 25, who represented a substantial proportion of those users. The onus is on Johnson to establish that the representation was misleading and deceptive but, following Burchett J’s observations in Janssen Pharmaceutical Pty Ltd v Pfizer Pty Ltd (1985) 6 IPR 227 at 234, if Johnson establishes that there is no foundation in the study for a statement in the advertisements, that may be sufficient proof that the statement is misleading. As his Honour recognised, the question is whether the context in which the representation is made implies that adequate foundation exists for making it.

53 Glaxo claims that, in all of the advertising and promotional materials, Reckitt makes statements of present and past fact as well as statements which are with respect to future matters. Glaxo relies upon a line of authority exemplified by the reasoning of Goldberg J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Purple Harmony Plates Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1062 at [18] where his Honour said:

I am satisfied that the representations relied upon by the Commission have been made in the company’s brochure and on the website. Almost all the representations were in terms which made them representations with respect to future matters. There were not merely representing matters of present or past fact; rather they were couched in terms that represented that the products presently possessed characteristics and benefits, the characteristics and benefits had been demonstrated to exist in the past and would be maintained and enjoyed in the future. Put shortly, the representations were saying that if a person was to buy the relevant product, it would display the relevant characteristic or produce the relevant benefit in the future after the purchase was made: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) (1999) 95 FCR 302 at 332.

54 Similar reasoning was applied by Lindgren J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) (1999) 95 FCR 302 at 331–332 [123]–[126] and by Dowsett J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Danoz Direct Pty Ltd (2003) 60 IPR 296 at 324 [126].

55 A representor who makes a representation with respect to a future matter which is challenged in Court must bring forward evidence that there were reasonable grounds for the making of that representation at the time that it was made if it wishes to avoid the presumptive consequences of engaging the operation of s 4 of the ACL. In the present case, Reckitt relies upon selected elements of the body of scientific knowledge current as at the time the relevant representations were made as constituting the necessary reasonable grounds. In effect, in the present case, the implied representation pleaded at par 15B of the AFTS captures the same idea or notion that underpins the legal requirement that there be reasonable grounds to support claims made with respect to future matters. The parties seem to accept in the present case that, once the Court has determined what representations were made by the impugned advertising and promotional materials, the question of whether or not those representations breached the ACL as alleged will be determined by the answer to a further question, namely, whether there was a current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge to support the claims being made. If there was such a foundation, Glaxo’s case will fail. If there was not such a foundation, the conduct in question will be misleading or deceptive. Here, once there was some evidence tending to support a conclusion that such a foundation existed, the onus of proving that it did not support the claims made rests upon Glaxo.

The Parties’ Relevant Businesses

56 At the hearing, Glaxo read two affidavits affirmed by Keri-jane Jacka, being her affidavits of 6 November 2015 and 11 December 2015. Glaxo also tendered the exhibits to those affidavits. The facts and matters addressed in this section of these Reasons are all taken from the evidence of Ms Jacka. They have been supplemented or corrected in a few minor respects by evidence led from Ms Ensor, an employee of Reckitt. Neither Ms Jacka nor Ms Ensor was cross-examined. These facts and matters were not seriously in dispute.

57 Ms Jacka commenced her employment with Glaxo in January 2014. As at the date of the separate questions hearing, she had been employed by Glaxo for almost three years. In November 2015, Ms Jacka was Head of Category & Shopper Marketing ANZ at Glaxo. At that time, she supervised a team of 11 people, five of whom focussed on OTC pain relief products. She said she was responsible for:

(a) Developing and embedding category growth drivers and adapting and adopting the global Glaxo plans to the Australian and New Zealand markets;

(b) Ensuring that the Market Activation Plan process, which is Glaxo’s annual market plan process, is followed and developing annual Channel Plans with the Glaxo sales team, which plans are tailored to each retail channel and customer;

(c) Developing Glaxo’s “go to market” plans. Matters to be addressed as part of this function include price, promotion, range, visibility and communications for all Glaxo product categories including shelf initiatives and trials with key customers; and

(d) Creating and presenting customer presentations in partnership with the sales and marketing departments at Glaxo.

58 A matter of particular interest to Ms Jacka and her team is shopper behaviour. For the purpose of gaining an accurate understanding of such behaviour, Ms Jacka and her team study and analyse consumption data including consumption data relating to competitors’ products and the wider category dynamics. Most of this data is provided to Glaxo from external sources which Glaxo judges as reliable.

59 At pars 14–21 of her first affidavit, Ms Jacka described the OTC pain relief market in Australia. That market consists of a range of pain relief medicines that can be purchased without prescription. The products sold in that market are not confined to products which restrict their efficacy claims to pain relief for common headaches (including TTH). The products are marketed as providing pain relief in respect of pain caused by a number of ailments.

60 The OTC pain relief market in Australia comprises two major brands, being Panadol and Nurofen, as well as a number of smaller brands, pharmacy owned brands and generic brands. In late 2015, Panadol and Nurofen together held approximately 71% of the OTC adult everyday pain relief market. At that time, that total market share was not split between Panadol and Nurofen 50/50 but was split in a ratio of approximately 46% to 54%.

61 The OTC pain relief category is the largest consumer health care category serviced by Glaxo. In addition to Panadol branded products, in that category, Glaxo sells stronger pain management brands such as Panadeine, Panafen and Voltaren.

62 OTC pain relief products are sold in Australia through pharmacies and grocery outlets (which include supermarkets). The grocery channel also includes, as far as Glaxo is concerned, petrol stations and convenience stores.

63 Glaxo’s pain relief portfolio contains both products for use by adult consumers and products for use by children. In Australia, there is a Panadol children’s range, which is available for use by children aged one month to 12 years.

64 Of the pain relief products available for purchase for use by adult consumers, certain Glaxo products are only available for purchase as OTC products in pharmacies because of regulatory requirements. These products are:

(a) Panadol Osteo;

(b) Panadol Extra, which contains paracetamol and caffeine;

(c) Panadeine, which contains codeine; and

(d) Panafen Plus, which contains ibuprofen and codeine.

65 The remaining products are available for sale OTC in both pharmacy and grocery in pack sizes of less than 20 tablets/caplets. For any packaging of more than 20 tablets/caplets, the product is only available for sale OTC in pharmacies, again because of regulatory requirements.

66 There is a range of active ingredients of the products that sit within this category. However, the active ingredient is either paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) or ibuprofen. Other active ingredients include aspirin and diclofenac sodium.

67 Common brand names of products containing paracetamol include Panadol, Herron Paracetamol, Panamax, Chemist Own and Dymadon. Common brand names for products containing ibuprofen include Nurofen, Advil and Chemist’s Own.

68 At par 21 of her first affidavit, Ms Jacka said:

There are two different types of adult OTC pain relief products. These are:

(a) Everyday pain relief – That is, products that consumers stock in their medicine cabinet that are needed in the event of common aches and pains that can be purchased OTC. The common brands in this category include Panadol, Nurofen, Heron [sic] and Advil; and

(b) Strong pain relief – That is, products aimed at the relief of acute pain conditions, being more severe every day aches and pains, such as migraines. For example, Panadine [sic] is [Glaxo’s] codeine based product used for strong pain including migraines. Common brands in this category include Panadine [sic], Nurofen Plus and Panamax.

69 Panadol has been supplied by Glaxo in Australia since 1959. It has a long heritage. It is a well-known and clearly identifiable product. It has very strong brand equity. Each year the manufacturing plant at Glaxo produces more than 50 million packs of Panadol and over 5 million bottles of paediatric liquids.

70 The active ingredient, common to all Panadol products, is paracetamol. The recommended OTC dose is 1,000 mg.

71 The following Panadol sub-brands are supplied in Australia for use by adults and are presented in the typical green packaging used for Panadol products:

(a) Panadol Tablets/Caplets;

(b) Panadol Rapid Caplets;

(c) Panadol Rapid soluble tablets;

(d) Panadol Mini Caps;

(e) Panadol Optizorb Caplets;

(f) Panadol Optizorb Tablets;

(g) Back and neck pain – Caplets;

(h) Panadol back and neck pain – long lasting; and

(i) Panadol Osteo.

72 In addition to the above products, Panadol Extra is also supplied in Australia for use by adults. Panadol Extra contains caffeine as an additional active ingredient and is presented in red packaging, rather than the typical green packaging used for the other Panadol products referred to above.

73 Each of these products is available in different pack sizes, with the Panadol Rapid Caplets also available in a Handipack, which is a slim easy to carry pack.

74 In an average grocery retailer (typically Coles, Woolworths and independents), the following Panadol sub-brands are available for purchase:

(a) Panadol Tablets;

(b) Panadol Rapid Caplets;

(c) Panadol Optizorb Caplets; and

(d) Panadol Optizorb Tablets.

75 A smaller range of these products is typically available in petrol and convenience stores.

76 In pharmacies, all Panadol sub-brands are generally available for purchase.

77 Panadol is typically sold in packaging which is green, white and red, the predominant colour of which is usually green. I set out below an illustration of the art work appearing on the packaging for Panadol Tablets. That artwork typifies most Panadol packaging.

78 Reckitt supplies Nurofen as an OTC ibuprofen pharmaceutical in Australia.

79 Nurofen is marketed under a number of different sub-brands and formats including Nurofen tablets and caplets and Zavance formulation. The active ingredient common to all Nurofen products is ibuprofen and the recommended single OTC dose is 400 mg.

80 As at December 2015, the sub-brands in the Nurofen adult pain range included:

(a) Nurofen – available in tablets or caplets;

(b) Nurofen caplets for migraine pain;

(c) Nurofen caplets for tension headache;

(d) Nurofen caplets for period pain; and

(e) Nurofen caplets for back pain.

81 Nurofen is generally sold through the same channels as Panadol.

82 Information received by Ms Jacka in her capacity as Head of Category & Shopper Marketing ANZ for Glaxo established that, in the 12 months ending 23 August 2015, the total value of the OTC pain relief market in Australia was $580.54 million.

83 At pars 48–68 of her first affidavit, Ms Jacka described how shoppers buy products in the OTC pain relief category and discussed the drivers to purchase products in that category.

84 At par 48 and par 49 of her first affidavit, Ms Jacka said:

I make a distinction between ‘consumers’ and ‘shoppers’ when talking about the OTC pain relief category. Specifically, within [Glaxo] we talk about the ‘path to purchase’. This starts with a consumer who is at home or out and about who may see some advertising for a product on, for example, television, online or when commuting (for example, on billboards or bus stops). It is the consumer who has the need for the product and who ultimately consumes that product. When that consumer considers buying the product they become a ‘shopper’, either for themselves or for another consumer who may be the person with the need. This is where in-store advertising and promotion becomes important.

The consumer and shopper can be the same person but are often different people. For example, a husband buying a product for his wife or children. The shopper is aware of the consumer’s needs but is not necessarily the consumer themselves.

85 Data received by Ms Jacka in the course of her employment at Glaxo also demonstrated that 82% of purchases of OTC pain relief products in grocery stores are planned while 91% of purchases of such products in pharmacies are planned. In Ms Jacka’s opinion, this means that those products are either on a shopping list as part of the shopper’s regular shop or people buy them to have them readily available in the event of a sudden onset of pain. When the pain is more severe, OTC products in the pain relief category can also be an emergency/distress purchase usually at a pharmacy or wherever is most convenient. OTC pain relief products are generally not an impulse buy, according to Ms Jacka.

86 Other data made available to Ms Jacka established that, generally speaking, purchasers of OTC pain relief medications purchase such products every 60.3 days.

87 Ms Jacka explained certain market research conducted for Glaxo and the implications of that research at pars 55–74 of her first affidavit. She said that when a consumer is considering purchasing an OTC pain relief product, that consumer is presented with a number of choices, including brand; format (eg tablets or caplets); pack size; and claims made by the manufacturer. Market research conducted for Glaxo established that the first thing which consumers do is to decide between a strong pain product from the pharmacist or everyday pain relief product from the shelf. The decision pathway then differs, depending upon the initial choice made. For example, within the “strong” pain category, brand is important. Within the “everyday” pain category, active ingredient is the most important.

88 Glaxo’s market research revealed that pain strength and active ingredient are the highest ranking attributes to shoppers in pharmacies. Brand also plays a role followed by whether the product is perceived as long lasting and fast acting. Long lasting and fast acting are often seen as important attributes because consumers want a product to work and to ease their pain as quickly as possible.

89 Glaxo’s market research also revealed that, in the grocery channel, a shopper’s first purchase decision is driven by the active ingredient followed by brand and then whether the product is fast acting. The option to choose between a strong pain product and an everyday pain relief product is not an option in supermarkets, as strong pain products can only be purchased in pharmacies due to regulatory requirements.

90 Market research conducted for Glaxo in July 2013 revealed that, of the top five functional needs for consumers with headaches/migraines, “fast acting” was the need perceived by Australian consumers as the most important need. In the three months leading up to July 2013, Panadol was the most popular brand for consumers with headaches/migraines followed by Nurofen.

91 An expression used within the OTC pain relief category is the concept of “repertoire shoppers”. These are shoppers who are willing to purchase and who, in fact, do purchase from time to time both ibuprofen and paracetamol products or shop between the two products. This behaviour could be because the purchase is for different household members, for different occasions or needs or because of other influences upon the purchase decision (eg price or in-store display). Overall, almost a third of consumers purchase both ibuprofen and paracetamol based products. In the pharmacy channel, almost half of paracetamol shoppers are loyal, while 40% of shoppers purchase both ibuprofen and paracetamol based products.

92 At par 68 of her first affidavit, Ms Jacka said:

In addition to repertoire shoppers, there are also always new consumers and shoppers entering the market. While people may have been consumers in the past, they may become new shoppers due to a change in household/personal circumstances. For example, when they move out of home or if people get divorced and historically their partner was the shopper for the household. New consumers also enter the market. For example, when babies are born, when children become adults or when adults discover they have a new condition, such as arthritis or start experiencing headaches for the first time, that needs to be treated.

93 In Ms Jacka’s view, some of the advertising materials under challenge in the present case targeted Australian consumers generally while others were more directed to trade purchasers (such as pharmacists).

94 Ms Jacka said that Australian consumers looking to purchase everyday pain relief products available OTC were likely to associate or equate Panadol with paracetamol.

95 Reckitt read and relied upon an affidavit affirmed by Emma Ensor on 2 December 2015. At the time she affirmed that affidavit, Ms Ensor was the Category Manager – Healthcare of Reckitt.

96 In her affidavit (at pars 33–39), Ms Ensor described the campaign. She said that the printed advertisements described by her in those paragraphs had been published in the following magazines since about early August 2015:

(a) Better Homes and Gardens;

(b) New Idea;

(c) Who;

(d) That’s Life; and

(e) Women’s Health.

97 The printed advertisements referred to by Ms Ensor are those which comprise Annexures A to D to the Application.

98 It is not necessary to refer in detail to other aspects of Ms Ensor’s evidence. However, in one particular respect, Ms Ensor took issue with the evidence of Ms Jacka. She claimed that the product images in the printed advertisements under challenge in this case represented the standard product offer for Nurofen and Panadol, being Nurofen tablets/caplets and Panadol tablets/caplets. She did not accept that the advertising had implications for all of the sub-brands of Panadol. Ms Jacka had asserted that the impugned advertisements represented both Panadol and Nurofen as umbrella brands with the consequence that the representations were considered by her to have general application across the entire suite of Panadol branded products and thus to have a detrimental effect upon all of the sub-brands of Panadol. This evidence was admitted as a submission only.

The Representations

99 In this section of these Reasons, I will describe the impugned advertisements in a little more detail, will consider the relevant class or classes of consumers to whom the advertisements were directed and determine what representations or messages were conveyed to such consumers by the advertisements. In the course of addressing these matters, I will determine the first three issues for trial identified at subpars (a), (b) and (c) of [45] above.

The Impugned Advertisements

Print Advertisements (Annexures A, B and D to the Application)

100 These print advertisements are also annexed to these Reasons for Judgment as Annexures A, B and D.

101 These print advertisements were published in the magazines identified at [96] above. Those magazines are purchased predominantly by women. They appeal to purchasers of all ages. An advertisement in the form of Annexure B also appeared in a Woolworths’ catalogue published in early August 2015.

102 The print advertisements which comprise Annexures A and B are substantially the same. In each case, the advertisement commences with the large block printing in prominent font of the words “NUROFEN IS BETTER THAN PARACETAMOL”. In addition, immediately under those words in smaller block lettering and less bold font, the words “FOR COMMON HEADACHES” appear. These latter words are not as conspicuous as the headline text. Nonetheless, they are clear enough and, given their position in the advertisement, operate to qualify the headline text. Immediately under those words, a graph appears. The only difference between the graph in Annexure A and the graph in Annexure B concerns the packaging which appears below the half way point towards the right hand side of the graph. In Annexure A there is depicted Panadol green and white packaging whereas in Annexure B there is depicted a plain white package with the word “Paracetamol” written on it. The Nurofen packaging depicted at the top left hand side of the graph is the packaging for “standard” Nurofen as distinct from Nurofen sub-products and Nurofen Zavance. In the top right hand corner of the graph, just to the right of the Nurofen packaging, there appear the following words in block letters and bold type:

FASTER PAIN RELIEF 1

MORE EFFECTIVE 1, 2

The graph then depicts a relationship between the impact of Nurofen (the red line) on pain and the impact of Panadol or paracetamol (as the case may be) on pain (the green line). Both the red and green lines shown on the graph terminate near the four hour point. Immediately underneath the graph, there is reference to Nurofen Zavance and a statement to the effect that that product provides faster relief than standard Nurofen. Underneath the reference to Nurofen Zavance, the following text appears:

Always read the label, use only as directed. Incorrect use could be harmful. If symptoms persist, consult your healthcare professional. 1. Schachtel et el, 1996, Steiner et al, 2007, Faster refers to complete relief 2. 80% of the people will experience tension-type headaches 3. Moore et al, 2014, Norholt et al, 2011, Schleier et al, 2007.

103 The print advertisement which is Annexure D to these Reasons is identical to the advertisement which is Annexure A to these Reasons with the exception that the very first claim at the top of the advertisement reads “NUROFEN IS SUPERIOR TO PARACETAMOL” instead of the words “NUROFEN IS BETTER THAN PARACETAMOL”.

104 The graph which appears in Annexures A, B and D tells the reader that what is being compared is standard Nurofen with standard Panadol (in Annexures A and D) and standard Nurofen with paracetamol (in Annexure B) when administered in doses of 400 mg and 1000 mg respectively.

105 The text “FASTER PAIN RELIEF” at the top of the graph, the text of footnote 1 (“Faster refers to complete relief”), the manner in which the lines on the graph itself are depicted and the text “MORE EFFECTIVE” at the top of the graph, when considered together as part of the whole message or series of messages conveyed to a reader of the advertisement, represent to a reasonable but not overly sophisticated reader of average intelligence that Nurofen, when taken as directed, provides complete relief from common headache pain faster than Panadol does and faster than paracetamol does and does so at a rate which is more effective at all points along the path from the point when the correct dosage is administered to the point when complete relief is achieved. It is in these senses that Nurofen is said to be “superior to” or “better than” both Panadol and paracetamol.

Print Advertisement (Annexure C to the Application)

106 This advertisement was published in the publication Retail Pharmacy in August 2015 and in the Australian Journal of Pharmacy in September 2015.

107 In this advertisement, Reckitt deploys red, black and white colours. The first words which appear in the advertisement are in white block letters and comprise: “NUROFEN IS SUPERIOR TO PARACETAMOL”. Immediately under those words, the following words appear in red block letters: “FOR TENSION-TYPE HEADACHES 1”. Underneath these words, a graph appears which is in a form which is slightly different from the graph which appears in Annexures A, B and D to these Reasons. It more closely reproduces the graph which is part of Figure 2 in the Schachtel Study referred to in the advertisements and in the AFTS (Schachtel et al: Nonprescription Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen in the Treatment of Tension-Type Headache (J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 36:1120–1125) (The Schachtel Study)). At the top of the graph, the following words appear: “Headache relief was significantly better with ibuprofen than with paracetamol1”. The three lines depicted on the graph are identified as ibuprofen 400 mg (the red line), paracetamol 1000 mg (the yellow line) and the placebo (the grey or purple line). Immediately underneath the graph, the following words appear:

Adapted from Schachtel et al, 1996.1

Mean headache relief ratings on a six-category scale (0 = no relief, 5 = complete relief) after administration of Nurofen (n = 153), paracetamol (n = 151) or placebo (n = 151) for tension-type headache. Pain relief rating with Nurofen was significantly different from paracetamol at all time points after administration (p < 0.01).1

108 Underneath this text there is a reference to Nurofen Zavance. Underneath the depiction of a Nurofen Zavance package, the following text appears:

Always read the label. Use only as directed. Incorrect use could be harmful. If symptoms persist, see your healthcare professional. ® Nurofen is a registered trademark of RB Australia, 44 Wharf Road, West Ryde, NSW 2114. References: 1. Schachtel BP et al. J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 36(12): 1120-5. 2. Moore RA et al. Eur J Pain 2015; 19(2): 187-92. 3. Norholt SE et al Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 49(12): 722-9. 4. Schleier P et al Int. J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 45(2): 89-97, July 2015, RECB10076.

109 In my view, the representations conveyed by the print advertisement which is Annexure C to these Reasons are substantially the same as the representations conveyed by the other print advertisements (Annexures A, B and D). It is noteworthy that, in Annexure C, in the text which appears immediately under the graph, Reckitt claims that the pain relief rating was significantly different from paracetamol (ie better than paracetamol) “at all time points after administration”. Such a claim is not made explicitly in the advertisements which comprise Annexures A, B and D. However, as I have already said (at [105] above), I am of the view that, on a fair reading and appreciation of those advertisements, such a claim is nonetheless made in each of them.

In-Store Advertising (Annexure E to the Application)

110 The material which appears at Annexure to the Application is the form of in-store advertising utilised by Reckitt. It is essentially the same as Annexure B.

The TVC

111 I have already described the TVC to some extent at [21]–[32] above. I will not repeat the contents of those paragraphs here, although a reader of these Reasons for Judgment needs to keep the contents of those paragraphs in mind when reading this section of these Reasons.

112 The TVC starts with the depiction of an actor with a headache and the voice-over commences “When you have a headache”. The image of the actor then changes into a computerised model with a depiction of pain in its head—indicated through highlighting of that area—and the voice-over continues: “you want fast effective relief”.

113 A standard Nurofen package is then depicted on screen and the voice-over continues: “Use Nurofen”.

114 Throughout this opening 12 second period of the TVC, there is text appearing at the bottom of the screen stating “Always read the label, use only as directed. Incorrect use could be harmful. If symptoms persist consult your healthcare professional.” That text moves across the screen quickly and is difficult to read because the print size is small.

115 After Nurofen packaging is depicted on the screen, the image changes to a depiction of light which then passes through the model. These images are accompanied by the voice-over “to target headaches /at the source /of pain /fast”.

116 Following the images of the model, a graph appears with the X axis titled “Patient Relief Rating” and the Y axis “Time (Hours)”. Two graphs are then plotted as the voice-over states “In a clinical study, /Nurofen was found to be superior to paracetamol /for common headaches”. During the final stages of the plotting of the graph, the image of Nurofen and green packages labelled “Paracetamol” appear on screen. The paracetamol packaging brings to mind Panadol. The voice-over then continues “providing faster”—then when the graph has reached the four hour time period a caption appears on screen stating “faster complete relief than paracetamol”. The voice-over continues “and more effective pain relief”—and the caption on screen changes to “significantly more effective”. Again, all when the graph has reached the four hour point. These stages of the TVC are quite rapid, taking only a few seconds to be completed. The predominant image on screen is the graph and the impression of superiority depicted by the projection of the Nurofen (red) line over the Panadol (green) line. It is difficult to make out the descriptions of the X and Y axes on the graph.

117 Throughout the depiction of the graph, a footnote appears stating: “1. Schachtel et al 1996, Steiner et al, 2007. 2. 80% of people will experience a tension-type headache”. This is available for only a short time and is difficult to read and absorb in the time available.

118 The last stage of the TVC depicts a packet of Nurofen and a packet of Nurofen Zavance with the text and voice-over stating “For faster relief than standard Nurofen, try Nurofen Zavance”. Throughout the depiction of the two Nurofen products, a footnote appears stating “3. Moore et al, 2014, Norholt et al, 2011, Schleier et al, 2007”.

119 Reckitt submitted that the following matters are apparent from the TVC:

(a) At all times it is only standard Nurofen which is compared with paracetamol. None of the sub-brands of Nurofen or of Panadol are referred to or depicted;

(b) The reference to Nurofen Zavance is made in connection with a comparison between standard Nurofen and Nurofen Zavance only. Nurofen Zavance is not compared with Panadol or any paracetamol product;

(c) The comparison undertaken in the TVC is limited to the speed and efficacy with which each product ameliorates the pain from common headaches only (including TTH) and does not purport to make any comparison as to the speed or efficacy of either product in relation to other ailments;

(d) The reference to “a clinical study” is clearly a reference to the Schachtel Study;

(e) The Schachtel Study does support the proposition that Nurofen was found to be superior to paracetamol in treating pain from common headaches and TTH;

(f) The comparison is clearly made in respect of a four hour time frame and the claims for faster and more effective pain relief relate to a four hour time frame. A fair appreciation of the messages conveyed by the TVC when the graph is on screen is that Nurofen provides complete relief more quickly within that time frame than does Panadol or paracetamol; and

(g) The comparison depicted in the TVC accurately mirrors the findings of the Schachtel Study.

120 With the exception of the contentions noted at subpars (e), (f) and (g) of [119] above, I think that Reckitt’s submissions which I have recorded at [119] above are correct.

The Relevant Target Consumers

121 The campaign comprised mass-market advertising being a television commercial, print advertising in magazines purchased by a broad cross-section of the public, print advertising in supermarket catalogues, point-of-sale advertising in retail outlets and outdoor advertising on billboards and at bus stops and train stations (Annexures A, B, D and E and the TVC) and trade advertising directed to pharmacists (Annexure C).

122 Nurofen, Panadol and the other paracetamol-based products referred to at [67] above are marketed and perceived by consumers in Australia as OTC products which provide relief from pain caused by a number of ailments commonly experienced by human beings of both genders and across all age groups from teens to the elderly. Included within those ailments is pain from common headaches including TTH.

123 Consumers often purchase such products for themselves but they also purchase them for other persons with whom they live or whom they know. Consumers will purchase such medicines to have them readily available in order to deal immediately with the onset of pain which is treatable by taking such medicines. Sometimes purchases will be made in order to treat an emergency.

124 Some consumers are loyal to a particular active ingredient (eg either ibuprofen or paracetamol), are loyal to a particular brand or shop for either or both active ingredients depending upon the ailment to be treated and the perception of the particular consumer as to the suitability of one product over another for the treatment of that ailment. Some consumers are new to the market. Within this latter group, some will pay close attention to the purchase and others will act more on impression. The products are relatively inexpensive. Although the level of engagement in respect of such products will not generally be high, most consumers will not purchase such products on impulse but will devote some thought to the decision which they ultimately make. Consumers are likely to be influenced by advertising of the type undertaken by Reckitt in the present case.

125 In Australia, there is strong brand awareness amongst consumers in respect of both Nurofen and Panadol. There is also a strong awareness of the active ingredient in each of those products.

126 In Australia, consumers tend to equate paracetamol with Panadol and vice versa. Panadol’s green and white packaging is very well known.

127 These OTC medicines are offered for sale in a large number of retail outlets located throughout Australia including supermarkets, petrol stations and pharmacies.

128 Print advertisements of the kind forming part of Reckitt’s campaign will not be studied closely by consumers. They will be looked at briefly but sufficiently to enable a reader of them to form an accurate impression of the main messages conveyed by the advertisements. Consumers are unlikely to read and absorb the footnoted material in detail, at least beyond noticing its general import including that, in part, it refers to scientific papers.

129 Those who watch the TVC will also be looking to gain an impression of the main points as the TVC progresses. Indeed, the TVC in the present case moves through the twelve frames quite quickly. The dominant messages come from the voice-over comments and the frames which show the graph.

130 In light of the above, and bearing in mind the contents of the print advertisements, the in-store advertising and the TVC, I think that the mass media advertisements are directed to those members of the public at large who are suffering from or who think that, at some time in the future, they may suffer from common headaches including TTH and who, for those reasons, wish to purchase an OTC everyday pain relief product such as Nurofen or Panadol in order to treat such pain. That target audience also includes those persons who shop for such products on behalf of or for the benefit of others.

131 I do not accept Glaxo’s submission to the effect that the target consumers comprise any person likely to want or to buy OTC analgesics for the treatment of pain caused by a range of ailments with an emphasis on those who suffer from common headaches. While it is true that both Nurofen and Panadol are marketed as medicines which provide relief from pain caused by a number of ailments including common headaches, this does not mean that the advertisements in the present case convey representations of the more general kind alleged by Glaxo. In my judgment, the representations made by Reckitt by means of the advertisements all relate to relief from pain caused by common headaches including TTH. In the case of the print advertisements, this is made clear by the bold text at the top of each advertisement and, in the case of the TVC, this is made clear by the contents of the voice-over material and the focus on the head of both the human and the model depicted in the TVC.

132 The trade advertisements (Annexure C) published in professional journals are directed to pharmacists. The intention here is obviously to persuade pharmacists of the superiority of Nurofen over Panadol in the hope that those pharmacists will promote Nurofen in preference to Panadol including, in particular, in answer to enquiries from customers as to which product provides faster and more effective relief from headache pain.

The Representations

133 It follows from [99]–[132] above that I do not consider that, by conducting the campaign, Reckitt made any of the disputed representations (as to which, see [35] and [36] above). Such representations as were actually made were made in respect of pain caused by common headaches including TTH and not in respect of pain caused by other ailments.

134 Reckitt admits that it made each and every one of the admitted representations (as to which, see [34] and [35] above). It also admits that, by the advertisements deployed in the campaign, it represented that, at the time when each of those representations was made, there was a current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge to support each such representation.

135 Notwithstanding Glaxo’s formulation of the representations said to have been conveyed by the impugned advertisements and notwithstanding Reckitt’s acceptance of that formulation in the respects identified at [34], [35], [38(b)] and [41] above, I think that the representations actually conveyed by those advertisements may be more appropriately and succinctly expressed as follows:

(a) By the impugned advertisements, Reckitt expressly represented that Nurofen, and thus ibuprofen, when taken in the recommended dose and as directed by the manufacturer, generally delivers faster and more effective relief from pain caused by common headaches including TTH than does Panadol or paracetamol.

(b) For the reasons stated in (a) above, by the impugned advertisements, Reckitt also expressly represented that Nurofen is better than Panadol and paracetamol for the treatment of common headaches including TTH and performs in a superior manner to Panadol and paracetamol in delivering pain relief for such headaches.

(c) By the impugned advertisements, Reckitt impliedly represented that, at the time when it conducted the campaign (August to December 2015), there was a current adequate foundation in scientific knowledge to support the representations set out in subpars (a) and (b) above.

Falsity

Introduction

136 The representations which I have distilled from the advertisements and promotional materials and set out at [135] above are representations of past and present fact. In addition, as already noted at [53] and [54] above, a number of judges in this Court have held that representations of this type, in particular when made in respect of certain specified therapeutic qualities of substances or products, are also representations with respect to future matters. That is, when claims of this type are made, the representor is regarded as stating to those to whom the representations are made: “If you take this substance or use this product as directed you will gain the benefits claimed”. Here, the claims are that, if consumers take Nurofen as directed, they will obtain relief from the pain which they may be suffering from a common headache, faster and more effectively than they would experience if they took Panadol or paracetamol instead.

137 Because Glaxo argued that the representations which I have set out at [135] above were also made with respect to future matters, it relied upon s 4 of the ACL. By making this submission, Glaxo sought to avail itself of the evidentiary advantages provided to an applicant by that section. In SPAR Licensing Pty Ltd v MIS Qld Pty Ltd (2014) 314 ALR 35 at 54–57 [67]–[74], I explained the import of s 51A of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) which more or less covered the same ground as s 4 of the ACL. It is an evidentiary provision only and does not reverse the legal or persuasive burden which the applicant bears of establishing that reasonable grounds for making the representations did not exist (see also Crowley v WorleyParsons Ltd [2017] FCA 3 at [71]).

138 Here, Reckitt claims that it had reasonable grounds for making the representations which I have found it made because the Schachtel Study supported the representations set out at subpars (a) and (b) of [135] above and constituted the necessary current foundation in scientific knowledge claimed by it thus establishing that the representation set out at subpar (c) of [135] above was true at the time when it was made.

139 Insofar as the representations which I have set out at [135] above constitute representations of past and present fact, Glaxo must prove that each representation was false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive at the time when it was made. Insofar as those representations were made with respect to future matters, Glaxo must prove that Reckitt did not have reasonable grounds for making those representations at the time when they were made ie throughout the period from early August 2015 to 15 December 2015. In the present case, both parties agree that the question of whether the requisite reasonable grounds existed for the representations will be decided by the answer to a further question, namely, whether the claims made in the campaign can be supported by an adequate foundation in scientific knowledge current throughout that period. In this regard, Reckitt relied upon the results of the Schachtel Study, the fact that no other clinical trial proved the opposite of those results or put those results in doubt and its success before the ASMI panels.

140 I think that this material was sufficient to satisfy the requirements of s 4 of the ACL so that the ultimate onus of proving the absence of reasonable grounds remained with Glaxo unaided by the presumptions referred to in s 4 of the ACL. Glaxo relied upon much the same scientific materials as were relied upon by Reckitt in order to establish its ultimate proposition—absence of reasonable grounds. Glaxo sought to place a very different interpretation upon those materials based upon the evidence of Professor Somogyi.

141 Glaxo makes an additional criticism of the impugned advertisements. It contends that ibuprofen and thus Nurofen is not suitable for consumption by all or practically all consumers looking for relief from pain caused by common headaches. Glaxo claims that this fact is not made clear in the impugned advertisements and that, for this reason, the advertisements are misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.