FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Domain Register Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1603

DIRECTOR OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS VICTORIA Applicant | ||

AND: | DOMAIN REGISTER PTY LTD ACN 127 506 807 Respondent | |

Murphy J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The respondent to this proceeding, Domain Register Pty Ltd (Domain), carries on a business as a supplier of internet domain name registration services. Its business model is to send an unsolicited standard form notice (Notice) to persons who have registered a business name with a “.com.au” domain name offering to supply registration of a “.com” domain name on payment of a specified price. The applicant, the Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria (Consumer Affairs), alleged that the Notices are misleadingly similar in appearance to an invoice. Consumer Affairs adduced evidence from five people who each said that they understood the Notice to be an invoice for renewal of the registration of their existing “.com.au” domain name. They said that they paid the price specified in the belief that the Notice was an invoice, and thereby obtained registration of a “.com” domain name which they did not intend to acquire and did not want.

2 Consumer Affairs alleged that Domain’s conduct in sending the unsolicited Notices:

(a) constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct which is likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) and s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (Victoria) (ACL (Vic)) (by operation of s 8 of the Australian Consumer Law and Fair Trading Act 2012 (Vic) (ACLFTA)); and

(b) contravenes s 40(3) of the ACL because the Notice is an “invoice or other document” which states the payment sought for supplying unsolicited services but does not contain the prescribed warning statement in circumstances where Domain had no or no reasonable cause to believe that there was a right to receive the payment.

3 For the reasons I explain I am satisfied that Domain’s conduct in sending the Notices constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct which is likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 18(1) of the ACL and the ACL (Vic). I do not consider that its conduct falls within s 40(3) of the ACL and the ACL (Vic), and it does not constitute a breach of that provision.

4 Because the ACL and the ACL (Vic) are relevantly the same I will refer only to the ACL, but the contraventions relate to both Acts.

THE PARTIES

5 The Director of Consumer Affairs is a public official whose office is established by s 107 of the ACLFTA. The Director is authorised by ss 109 and 110 of the ACLFTA and by ss 228, 232, 246 and 247 of the ACL and the ACL (Vic) to bring this proceeding.

6 Domain is a company incorporated and registered in Western Australia pursuant to the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and a corporation for the purposes of s 4 of the CCA by virtue of being a trading corporation formed within the limits of Australia. It carries on a business throughout Australia (including in Victoria) as a supplier or purported supplier of services, including by offering, supplying or managing domain name registration for internet users including persons ordinarily resident in or carrying on business in Victoria.

THE EVIDENCE

7 Consumer Affairs relied on the following eight affidavits:

(a) five affidavits made by persons who received Notices sent by Domain and who allege they were misled, being:

(i) Ronald Hugh Allen affirmed 30 September 2015 (re: YarraTri Inc (YarraTri));

(ii) Katina Demetriou affirmed 29 October 2015 (re: Geelong Beauty & Wellbeing Centre (Geelong Beauty));

(iii) Jacqui Maria Archer sworn 13 November 2015 (re: George Archer Metals Pty Ltd (George Archer Metals));

(iv) Troy Maxwell Hopkins affirmed 30 September 2015 (re: Top Steel Detailing Pty Ltd (Top Steel)); and

(v) Helena Nobs sworn 21 September 2015 (re: Trend Vend Pty Ltd (Trend Vend));

(b) three affidavits by bank officers in relation to Domain’s bank account records produced on subpoena, being:

(i) Selvije Lika, a statutory compliance consultant employed by the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (ANZ) affirmed 7 December 2016 ;

(ii) Natasha Sabotkovski, a statutory compliance consultant employed by the ANZ, affirmed 9 November 2015; and

(iii) Deanne Nicole Arbuckle, a manager employed by Westpac Banking Corporation, affirmed 17 November 2016;

8 Domain relied on an affidavit by Ryan John Manning sworn 25 October 2016. He is a director of Service Desk Pty Ltd, which is responsible for processing orders and payments for Domain.

THE FACTS

9 Domain did not cross-examine any of Consumer Affairs’ witnesses and Mr Manning’s affidavit did not contradict their evidence. The parties filed an agreed statement of facts in relation to some matters. I accept the evidence of each deponent as to the primary facts asserted. I set out my view of the evidence below.

The Domain Name System

10 In the agreed statement of facts the parties explained the operation of the internet, the Domain Name System, and the eligibility for registration of “.com.au” and “.com” domain names as follows:

(a) Each internet website and web page has a unique address called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) which allows an internet user to access a website or web page by entering the URL into a browser. A domain name forms part of the URL address. Using a domain name enables an internet user to access a web page by typing in words or letters instead of the full sequence of digits comprising an Internet Protocol number (IP number). Computers which share a common part of an IP number are said to be in the same “domain”.

(b) A hierarchical system of databases called the “Domain Name System” serves to cross-reference and link domain numbers to IP numbers. The “Top Level Domains” are:

(i) “generic Top Level Domains (gTLDs), which are domain names that may, for example, end in “.com”, “.net”, “.org”, “.gov” or “.edu” and refer to commercial, network, organisation, government bodies or educational institutions respectively; and

(ii) “country code Top Level Domains” (ccTLDs), which are domain identifiers for different countries, for example, “.au” which signifies Australia and “.nz” which signifies New Zealand.

(c) The “Second Level Domains” (2LDs) are:

(i) “Open 2LDs” which, subject to eligibility rules, are open to all sectors of the community and, for example, include names ending in “.com.au” and “.net.au”; and

(ii) “Closed 2LDs” which are restricted to defined sectors. For example, names ending in “.edu.au” which is restricted to educational institutions or ending in “.gov.au” which is restricted to government agencies.

(d) By a sponsorship agreement with the not-for-profit organisation Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), .au Domain is the delegated authority for the administration of the .au ccTLD in Australia. .au Domain has contracted AusRegistry to implement the registry system.

(e) AusRegistry has the function of accrediting and licensing “registrars” which can license and register “.au” domain names and which are responsible for updating the AusRegistry database of registered domain names. A registrar may appoint a “reseller” to act as an agent for the registrar and deal directly with a proposed registrant, but a reseller cannot itself register a domain name. If the registrar approves the domain name and the application for a domain name is successful, the registry is updated so that other computers on the internet can find the new domain name.

(f) A registrant of a domain name is the exclusive licence-holder of the domain name for the period of the licence.

(g) The grant of a licence in respect of a domain name does not preclude another person from registering a similar domain name in a different gTLD or 2LD. For example, where a domain name ending in “.com.au” has been registered, a person other than the registrant may register that name in another domain such as “.com”.

Eligibility requirements for registration of a “.com.au” domain name

11 To be eligible for a domain name in the “.com.au” 2LD a registrant must be:

(a) an Australian registered company;

(b) trading under a registered business name in any Australian State or Territory;

(c) an Australian partnership or sole trader;

(d) a foreign company licensed to trade in Australia;

(e) an owner of an Australian Registered Trade Mark;

(f) an applicant for an Australian Registered Trade Mark;

(g) an association incorporated in any Australian State or Territory; or

(h) an Australian commercial statutory body.

12 To be eligible for registration a “.com.au” domain name must:

(a) exactly match or be an acronym or abbreviation of the registrant’s company or trading name, organisation or association name or trademark; or

(b) be otherwise closely and substantially connected to the registrant.

Eligibility requirements for registration of a “.com” domain name

13 There are no eligibility requirements for registration of a “.com” gTLD, which is done by or through ICANN.

Domain’s business

14 Domain’s business has at all material times included offering to provide and providing domain name registration services in respect of the “.com” domain name equivalent to a person’s existing registered “.com.au” domain name. It admits that it has at all relevant times been engaged in trade or commerce and that the relevant conduct was conduct in trade or commerce.

15 To facilitate its business Domain engaged a third party data management company to enter the names and domain name details of persons who have a license or right to use a domain name ending in “.com.au” into a database, and it used that database to generate and send Notices to those persons. In the proceeding it sought to characterise the Notices as an offer to supply domain name registration services in respect of the “.com” domain name equivalent to each person’s existing registered “.com.au” domain name, upon payment of a fee.

16 Domain is neither a registrar nor a reseller of domain names. Upon receipt of payment of the fee specified in the Notice it facilitates the registration of domain names by entering the details of the gTLD to be registered onto the website of a registrar, or the ccTLD to be registered onto the website of a reseller, and sends an electronic request to that registrar or reseller to register that domain name. It charges a fee for doing so.

17 It admitted that in the period between 1 January 2011 and 30 May 2014 (the relevant period) it sent a total of 437,819 unsolicited Notices to 301,083 persons who were the registrants of a “.com.au” domain name. It sent more than one Notice to some persons. For example, the evidence shows that Domain sent YarraTri five Notices over the relevant period.

18 During the relevant period 21,089 “.com” domain names were registered through Domain, which is 4.82% of the 437,819 Notices it sent out, or 7% of the 301,083 persons to whom Domain sent Notices.

19 At the time Domain sent out the Notices it did not know whether or not the relevant “.com” domain name was available for registration. Of the 301,083 “.com.au” domain names in respect to which it sent out Notices in the relevant period only 235,887 of them were actually available for registration (at least as at the date of Mr Manning’s affidavit). That is, approximately 65,000 of the domain names in relation to which Domain sent out Notices were unavailable. Mr Manning stated that if a recipient of the Notice paid to register a “.com” domain name which was then discovered to be unavailable Domain would refund the payment.

20 44,107 of the “.com” domain names were registered after Domain made offers to register them through the Notices, but not by way of the recipient of the Notice accepting Domain’s offer. Domain sought an inference that on the balance of probabilities a substantial majority of those 44,107 recipients decided that they wanted to acquire a “.com” domain name but chose to do so through a different service provider. I accept that the majority of persons who registered a “.com” domain name in this way did so because they wished to acquire that name, but there is no basis to infer that such acquisitions were in any way related to the Notices.

21 In the relevant period 11,238 of the businesses or organisations that registered a “.com” domain name through Domain renewed the registration.

22 Domain admitted that the Notices it sent in the relevant period included notices in substantially the same form as those it sent to YarraTri, Geelong Beauty, George Archer Metals, Top Steel and Trend Vend, as set out below.

23 It also admitted that the payment amount stated in the Notices sent to each of YarraTri, Geelong Beauty, George Archer Metals, Top Steel and Trend Vend were in respect of an unsolicited offer of services and not in respect of services that had been requested by those businesses. The position is different in relation to the second document sent to Geelong Beauty which (as Domain accepted) is an invoice for renewal of the registration of the “.com” domain name Ms Demetriou (mistakenly) earlier registered. It is unnecessary to decide whether the second document constitutes an unsolicited offer of services.

24 The Notices did not include the text “This is not a bill. You are not required to pay any money”, as provided by s 40(3) of the ACL.

Ms Demetriou’s evidence re: Geelong Beauty

25 Ms Demetriou was at all material times the owner and manager of Geelong Beauty & Wellbeing Centre, located in Geelong, Victoria. Geelong Beauty has owned the domain name www.geelongbeautyandwellbeingcentre.com.au (Geelong Beauty’s domain name) since 2009. The registrar of the domain name was at all material times Serverside IT.

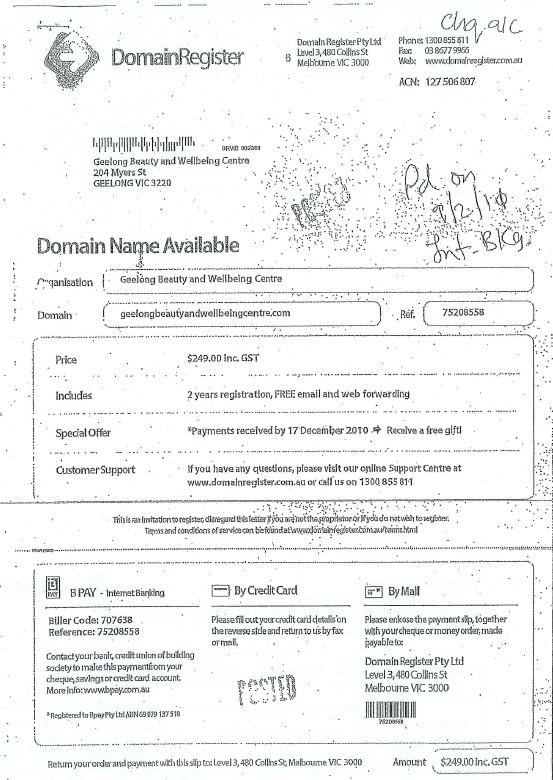

26 In about November 2010 Ms Demetriou received an unsolicited Notice by mail addressed to Geelong Beauty, from Domain. The following is an image of the Notice received (together with Ms Demetriou’s later notations):

The reverse side of the invoice provided for the recipient to complete credit card payment details and return a slip with payment.

27 As with each Notice recipient who made an affidavit on behalf of Consumer Affairs, Domain admitted that Ms Demetriou had not contacted it and had not asked it to provide any services.

28 Ms Demetriou understood the Notice to be an invoice for the renewal of the registration of Geelong Beauty’s existing domain name. She said she formed that belief because the Notice was formatted similarly to an invoice, was addressed specifically to Geelong Beauty, contained a reference number, listed a domain name (which she thought was Geelong Beauty’s domain name) and included payment options for payment of $249 for two years registration. Ms Demetriou paid the invoice on about 9 February 2011.

29 On about 2 November 2012 Ms Demetriou received a second document by mail from Domain. It is unnecessary to set out an image of this document. It suffices to note that the document has the appearance of an invoice from Domain to renew the registration of Geelong Beauty’s domain name. Although it related to the “.com” domain name that Ms Demetriou (mistakenly) earlier acquired, she understood it to be an invoice for maintenance of Geelong Beauty’s existing domain name. Domain characterised the document as an invoice. For clarity I will call it “the second invoice”.

30 The second invoice differs from the Notice in that it contains the heading “Tax Invoice” together with a due date for payment of $249 for two years registration. Otherwise, the two documents are largely the same.

31 In accordance with her usual practice Ms Demetriou stored the second invoice in a file, without immediately paying it. In about February 2013 she retrieved it and recalled that she had paid a similar invoice to Domain in 2011. She paid the second invoice on about 5 February 2013 in the belief that the payment was for maintenance of Geelong Beauty’s existing domain name.

32 On about 13 June 2013 Ms Demetriou received an invoice from Serverside IT in relation to Geelong Beauty’s domain name, and she paid that invoice.

33 Then, later in June 2013, Ms Demetriou received advice from an advisory firm with regard to Geelong Beauty’s website and the use of vouchers. That gave her cause to review the invoices she had paid to Domain and, for the first time, she noticed that the invoices did not relate to her existing domain name but to a “.com” domain name. She realised that she had paid the first and the second invoices in the mistaken belief that both related to Geelong Beauty’s existing domain name. At no time had she sought to become the registered proprietor of a “.com” domain name.

34 In about June 2013 Ms Demetriou demanded a refund from Domain. She complained that she had been tricked into paying the two invoices sent by Domain because they were unsolicited and specified that they were for a domain name which she said was “virtually indistinguishable” from Geelong Beauty’s domain name. She said that she did not want the “.com” domain name and would not have paid the invoices if she knew that they did not relate to Geelong Beauty’s existing domain name. Initially Domain’s representative refused to provide a refund but it later refunded all the money she had paid.

Mr Allen’s evidence re: YarraTri

35 Mr Allen was at all material times the voluntary Treasurer and Vice President of YarraTri Inc, a triathlon and multisport club based in Fitzroy, Victoria. He was also a supervisor at an accounting and consultancy firm in Melbourne. YarraTri has held the domain name www.yarratri.com.au (YarraTri’s domain name) since October 2010. At all material times the registrar of the domain name was an entity named Jumba which later changed its name to Uber.

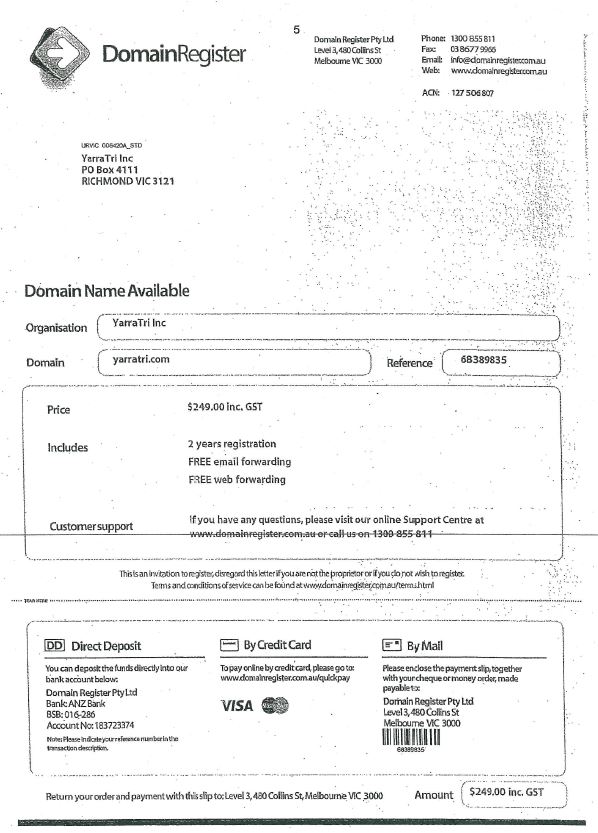

36 In about February 2013 Mr Allen received an unsolicited Notice by mail addressed to YarraTri, from Domain. The following is an image of the Notice:

37 Domain admits that YarraTri had not contacted it and had not asked it to provide any services.

38 Mr Allen was responsible for paying all invoices YarraTri received and he knew that YarraTri received an invoice in relation to domain name registration approximately every two years. He did not know the name of the registrar of YarraTri’s domain name.

39 He understood the Notice to be an invoice for renewal of YarraTri’s domain name. He formed that belief because the Notice was specifically addressed to YarraTri, it referred to a two-year period of domain name registration, it contained the domain name (which included “yarratri”), it included a reference number, and it offered different payment options to pay $249 for two years domain name registration. He consulted YarraTri’s annual accounts and noted there was no payment listed for renewal of YarraTri’s domain name for the previous financial year and thought that an invoice for renewal of the domain name was expected. He paid the invoice by direct deposit on 18 February 2013 believing that by doing so YarraTri would secure its domain name for a further two year period. He did not intend to acquire an additional “.com” domain name for YarraTri.

40 In about May 2014 YarraTri received a second invoice from Domain, in identical form to the first Notice. Mr Allen was unsure why YarraTri had received a second invoice because he had paid the earlier invoice. On 15 May 2014 he telephoned Domain and spoke with a man who identified himself as “Tim”. It is uncontentious that “Tim” is Tim Jacobson, a Domain employee or contractor. Mr Jacobson said that it did not appear as if YarraTri had paid the price specified in the Notice but Mr Allen assured him that he had done so. Mr Jacobson was then able to locate YarraTri’s payment. He said the payment had been placed into a suspense account rather than into YarraTri’s customer account because YarraTri had not included the reference number with the payment.

41 Mr Allen enquired why YarraTri’s website had continued to operate even though Domain’s records indicated that YarraTri had not paid the registration fee. Mr Jacobson explained that the invoice sent to YarraTri was to register a website that ended with a “.com” domain name which was separate from YarraTri’s existing “.com.au” domain name, and that YarraTri did not need the “.com” domain name to operate its existing website.

42 Mr Allen explained that YarraTri did not want an additional web address and asked for a refund of the $249 paid. Domain refunded YarraTri that amount the same day.

Ms Archer’s evidence re: George Archer Metals

43 Ms Archer was at all material times the receptionist at George Archer Metals Pty Ltd, a family business that supplies stainless steel products and stainless steel cutting services, where she had worked for approximately four years. George Archer Metals has held the domain name www.archermetals.com.au (George Archer Metals’ domain name) since 2011. At all material times the registrar of the domain name has been Crazy Domains.

44 Ms Archer knew that Crazy Domains invoiced George Archer Metals, but she did not help set up the website, did not have any dealings with the registrar, and had limited knowledge about website registration and maintenance.

45 In about September 2013 Ms Archer received an unsolicited Notice by mail addressed to George Archer Metals, from Domain. It is unnecessary to set out an image of the Notice. It is in the same form as the Notice sent to YarraTri (set out at [36] above), except that it is addressed to George Archer Metals, it refers to George Archer Metals Pty Ltd as the relevant organisation, it refers to the domain name “georgearchermetals.com” and it carries a different reference number.

46 Domain admitted that George Archer Metals had not contacted it and had not asked it to provide any services.

47 It was part of Ms Archer’s duties to pay the invoices received. She understood the Notice to be an invoice for renewal of George Archer Metals’ domain name because it was addressed to George Archer Metals, it contained a reference number, a domain name and various options for payment of $249 for two years of domain name registration. Because she had not previously seen an invoice from Domain, she showed the invoice to her father, John Archer, the Managing Director of the company.

48 Ms Archer compared the Notice to a previous invoice that George Archer Metals had received from Crazy Domains. She said that both invoices looked similar, both were addressed to George Archer Metals and both appeared to relate to the same domain name. She also showed the invoice to her brother, Thomas Archer, a sales representative with the company, and he told her that he did not see any “issues” with the invoice. Following those inquiries Ms Archer paid the invoice from Domain, in the belief that she was renewing George Archer Metals’ domain name. She did not intend for the company to acquire an additional domain name.

49 In about February 2014 Ms Archer received another Notice by mail addressed to George Archer Metals, from Domain. Ms Archer again understood it to be an invoice but she was confused because she knew she had made a payment to Domain only five months earlier. She examined the invoices again and realised that the domain name stated on the two Notices was www.archermetals.com rather than www.archermetals.com.au.

50 In about March 2014 Ms Archer contacted Domain and demanded a refund because she said that she had been misled and had paid the invoice in the belief that it related to George Archer Metals’ existing domain name. Domain’s representative initially refused to provide a refund. Following an email exchange on 15 May 2014, Domain agreed to make a partial refund of $199 but then refunded the full amount.

Mr Hopkins’ evidence re: Top Steel

51 Mr Hopkins was at all material times the owner and sole director of Top Steel Detailing Pty Ltd, a company that provides services including structural steel workshop drawings and tender-based estimates relating to structural steel. He had been the owner and director of Top Steel since its establishment in 2007. Top Steel holds the domain name www.topsteeldetailing.com.au (Top Steel’s domain name) which it had held for several years. During the relevant period the registrar of the domain name was NetRegistry. It sent renewal notices every two years for registration of Top Steel’s domain name. Mr Hopkins said that apart from paying those notices he had no need to deal with NetRegistry.

52 In about September or October 2013 Mr Hopkins received an unsolicited Notice by mail addressed to Top Steel, from Domain. It is unnecessary to set out an image of the Notice. It is in the same form as that sent to YarraTri (set out at [36] above), except that it is addressed to Top Steel, it refers to Top Steel as the relevant organisation, it refers to the domain name “topsteeldetailing.com” and it carries a different reference number.

53 Domain admitted that Top Steel had not contacted it and had not asked it to provide any services.

54 Mr Hopkins understood the Notice to be an invoice for renewal of Top Steel’s domain name and he put it to one side to deal with when he was less busy. When he received the invoice he thought it was around two years since he had last renewed Top Steel’s domain name, and on examining the document it appeared to him to be an invoice for such renewal. On 28 October 2013 he paid $249 to Domain in the belief that he was paying to renew Top Steel’s domain name for another two year period. He did not intend to acquire the domain name www.topsteeldetailing.com.

55 On 18 March 2014 Mr Hopkins received an email from NetRegistry which informed him that Top Steel’s domain name was due to expire on 15 June 2014 and offered to renew it. That made him suspicious about the invoice he had paid to Domain. On 27 May 2014 he telephoned Domain and spoke to Mr Jacobson. Mr Hopkins sought an explanation as to why he had paid money to Domain but had then received an invoice from NetRegistry. Mr Jacobson informed him that the Notice was an offer to register the domain name www.topsteeldetailing.com and that NetRegistry was offering to renew the domain name www.topsteeldetailing.com.au. Mr Hopkins said that he had paid Domain’s invoice in the belief that it related to Top Steel’s existing domain name and that he did not need the “.com” domain name.

56 Mr Jacobson said that Domain would provide a partial refund in the amount of $199 which it paid that day. Subsequently Domain refunded a further $50.

Ms Nob’s evidence re: Trend Vend

57 Ms Nobs was at all material times the owner and sole director of Trend Vend Pty Ltd, a company that provides services relating to vending machines. She personally manages the administrative aspects of the business, including receiving and processing all incoming mail and paying all bills and invoices. Trend Vend has held the domain name www.trendvendsydney.com.au (Trend Vend’s domain name) since Trend Vend was established in approximately March 2010. At all material times the registrar of the domain name was Digital Pacific.

58 Ms Nobs said that she spent little time dealing with Trend Vend’s domain name. She received a renewal notice every two years but apart from that she did not have any ongoing contact with Digital Pacific.

59 In October 2013 Ms Nobs received an unsolicited Notice by mail addressed to Trend Vend, from Domain. It is unnecessary to set out an image of the Notice. It is in the same form as the Notice sent to YarraTri (set out at [36] above), except that it is addressed to Trend Vend, it refers to Trend Vend as the relevant organisation, it refers to the domain name “trendvendsydney.com” and it carries a different reference number.

60 Domain admitted that Trend Vend had not contacted it and had not asked it to provide any services.

61 Ms Nobs formed the belief that the Notice was an invoice related to the registration of Trend Vend’s domain name because it looked to her like a renewal notice, it referred to a domain name with the words “trendvendsydney”, and she did not notice that there was no “.au” at the end of the domain name. On 31 October 2013 she paid Domain the price stated in the Notice, doing so in the belief that she was paying a renewal invoice for Trend Vend’s domain name. She did not intend to acquire an additional domain name.

62 In March 2014 Ms Nobs received and paid a renewal invoice from Digital Pacific for registration of Trend Vend’s domain name for a further two years. At that point she realised that the invoice she had received and paid from Domain did not relate to a renewal of Trend Vend’s domain name but related to the registration of a new domain name.

63 In mid-April 2014 Ms Nobs telephoned Domain and said that she had paid the invoice by mistake and that she thought the invoice related to the renewal of registration of Trend Vend’s domain name. She said that she never wanted the “.com” domain name and paid $249 to Domain by mistake. Domain’s representative said that it would only refund her $199 and it paid that the same day. Subsequently it refunded a further $50.

THE MISLEADING OR DECEPTIVE CONDUCT CLAIM

Legislation and legal principles

64 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

65 There is little contest between the parties as to the relevant principles and their differences lie in the application of the principles to the facts. It suffices to set out several established principles.

66 First, it is of little significance that the present case does not involve allegations of express or implied misleading representations. The meaning of “conduct” in s 18(1) of the ACL is deliberately broad so as to give it a wide application to activities that are likely to mislead or deceive consumers. It is not confined to express or implied representations: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592; [2004] HCA 60 (Butcher) at [32] (Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ), [108] (McHugh J) and [179] (Kirby J); Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Limited (2010) 241 CLR 357; [2010] HCA 31 at [15] (French CJ and Kiefel J). As the majority said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640; [2013] HCA 54 (TPG) at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ):

Conduct is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, if it has a tendency to lead into error.

67 Second, the Court’s task is to examine the impugned conduct as a whole in the light of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances to determine whether a contravention of s 18(1) has occurred. Where, as in the present case, the alleged contravention relates primarily to a document, the effect of the document must be examined in the context of the evidence as a whole. The Court is not confined to examining the document in isolation and it must have regard to all the conduct of the alleged contravener in relation to the document: Butcher at [109] (McHugh J) cited with approval in Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304; [2009] HCA 25 (Campbell) at [102] (Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

68 Third, for a contravention to be established there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and error on the part of persons exposed to it. In that sense it can be said that the prohibition in s 18 is not intended for the benefit of people who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests: TPG at [39].

69 Fourth, where, as in the present case, the conduct is directed at a broad cross-section of the public the Court must assess the conduct by reference to the class of persons likely to be affected. It is necessary for the Court:

(a) to identify the class likely to be affected by the conduct;

(b) once the relevant class is identified, to assess the matter by reference to all persons who come within the class. Where the conduct is addressed to the public at large the class will include “the astute and the gullible, the intelligent and the not so intelligent, the well-educated as well as the poorly educated, men and women of various ages pursuing a variety of locations”: Puxu Pty Ltd v Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd (1980) 31 ALR 73 (Puxu) at 93 (Lockhart J); Taco Company of Australia v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 202 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ); and

(c) to assess whether the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive by reference to the reaction of a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class to the impugned conduct. The assessment must exclude reactions to the conduct that are extreme or fanciful: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435; [2013] HCA 1 (Google) at [7] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ); Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45; [2000] HCA 12 (Campomar) at [102]-[105] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

70 The authorities indicate that it is necessary to show that a “not insignificant” proportion of the class are likely to be misled or deceived by the alleged conduct: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2004) 61 IPR 420; [2004] FCAFC 91 at [70]-[71] (Jacobson and Bennett JJ), [23] (Dowsett J); Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd (2008) 171 FCR 579; [2008] FCAFC 181 at [46] (Tamberlin J), [66] (Siopis J). As I said in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd (2014) 316 ALR 590; [2014] FCA 568 at [397]-[399], there is unlikely to be any real difference between an assessment that the ordinary or reasonable class member is likely to be misled and an assessment that a not insignificant proportion of the class are likely to be misled.

71 Fifth, whether the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class is likely to be misled or deceived may involve questions as to the characteristics or knowledge properly to be attributed to members of the class: TPG at [45] and [53].

72 Sixth, it is insufficient to show that consumers are merely confused by the conduct in order to establish a contravention. Confusion or wonderment is not necessarily coextensive with misleading or deceptive conduct: Taco Bell at 201; Google at [8].

73 Seventh, as the words “likely to mislead or deceive” in s 18(1) make clear, it is not necessary to demonstrate that a person has actually been misled or deceived to establish a contravention: Puxu at 198; Google at [6]. Nor is it determinative that a consumer formed an incorrect impression as a result of the alleged conduct. The question as to whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive is a question of fact that the Court must decide objectively for itself: Puxu at 197; Taco Bell at 202.

74 Even so, as Allsop CJ said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73; [2014] FCA 634 at [45]:

Evidence that someone was actually misled or deceived may be given weight. The presence or absence of such evidence is relevant to an evaluation of all the circumstances relating to the impugned conduct.

The Target Audience

Identifying the target audience

75 In the relevant period Domain sent out a total of 437,819 unsolicited Notices to 301,083 persons who were the registrants of a “.com.au” domain name. It admitted that the Notices it sent out were in substantially the same form as those it sent to YarraTri, Geelong Beauty, George Archer Metals, Top Steel and Trend Vend.

76 Over a three and a half year period Domain sent out a great number of unsolicited Notices in similar form to persons around Australia who had registered a “.com au” domain name, and its conduct is properly characterised as being directed to a broad cross-section of the Australian public. The eligibility requirements for registration of a “.com.au” domain name indicate that the target audience of the Notices largely comprised people carrying on businesses and companies and organisations in or connected to Australia.

The characteristics to be imputed to the target audience

77 Domain submitted, and I accept, that use of the internet permeates modern business. Such use is not limited to business proprietors and it extends to employees, many of whom are likely to spend many hours a week using the internet.

78 Domain contended that use of the internet carries with it the use of, and necessarily an appreciation of, domain names. It said that recognition of the distinction between different gTLDs such as “.com”, “.net” and “.gov” and between different ccTLDs is a necessary part of this. In this regard it submitted that the evidence of Mr Allen, Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs shows that each of them knew and understood the difference between a domain name ending in “.com” and one ending in “.com.au”, because it was not necessary to explain the difference between a “.com” and a “.com.au” domain name to them. It argued that the same conclusion should be drawn in relation to the class to which the Notices were sent. For the reasons I explain at [112]-[113] I do not accept this contention.

79 Domain argued, and I accept, that the class does not include the now small group of people who do not use the internet. Nor were the Notices sent to consumers who may be taken to have a lower level of knowledge as to the internet and domain name registration.

80 It submitted that the ordinary or reasonable class member will have read a document inviting or requesting payment with a degree of care.

81 Domain also contended that class members have a good reason to obtain the “.com” equivalent of their existing “.com.au” domain name because doing so will avoid deliberate or coincidental use of their domain name by competitors or other businesses, will prevent “cyber-squatting”, and will ensure that their business captures the maximum number of customer “hits” on the internet (because traffic to the “.com” domain name will be diverted to the “.com.au” website).

82 Domain’s submissions are not without force, but they do not adequately deal with one fundamental point. Over the course of three years it sent unsolicited Notices to approximately 301,083 persons around Australia. Notwithstanding that the Notices were sent to businesses and organisations with a “.com.au” domain name, the class to which they were sent was broad and is likely to have included a diverse cross-section of people. It included the uneducated, the inexperienced, the ignorant and the unthinking as well as the educated, the intelligent and the informed.

83 In essence Domain argued that the ordinary or reasonable class member is likely to have had a reasonably high level of knowledge and perspicacity regarding the internet and domain name registration and likely to have paid close attention to the Notice. I do not accept this.

84 First, it is likely that many recipients of the Notices are relatively unsophisticated internet users with little knowledge in relation to the system for domain name registration, save for understanding that a domain name can be registered. Such persons are unlikely to understand that very similar domain names are capable of separate registration.

85 I am confirmed in that view by the evidence of Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs. For example, Ms Demetriou ran a small business in a regional city providing a range of specialty beauty products and services, alternative therapies and beauty counselling services. In the absence of evidence (and there is little) I would not readily infer (as Domain in effect seeks) that she has a reasonably high level of knowledge about the internet and domain name registration. Such evidence as there is points away from such an inference. Nor do I consider it appropriate to attribute to her the knowledge that closely similar domain names (in Ms Demetriou’s case “geelongbeautyandwellbeingcentre.com.au” and “geelongbeautyandwellbeingcentre.com”) are capable of separate registration. Again, such evidence as there is points the other way. I take the same view in relation to the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable class member.

86 The decision in .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd (2004) 207 ALR 521; [2004] FCA 424 (.au Domain) also (in part) concerned notices sent to Australian businesses which made an offer to register the “.com” equivalent of an existing registered “.com.au” domain name. I broadly adopt the remarks of Finkelstein J at [34] where his Honour said:

Within the class from which the hypothetical individual is drawn there will be members (perhaps only a few) who know a good deal about the system of registration of domain names and members (whom I believe account for a significant number) who know little or nothing about the registration system save for the fact that a domain name can be registered. In the absence of any evidence (and there is none) I am not, however, prepared to infer that any member of any group knew of the existence or role of an accredited registrar or an appointed reseller. I am prepared to assume that some members would be aware that it is possible to obtain separate registration for substantially similar domain names such as fedcourt.gov.au, fedcourt.net.au and fedcourt.com. Conversely, there will be a significant number who will not appreciate that these different but nonetheless closely similar names are capable of separate registration.

87 I accept that there has been a huge growth in internet usage since .au Domain was decided and that many internet users will be more knowledgeable and sophisticated. However in my view there are still likely to be many members of the class in the present case who are relatively unsophisticated internet users, who have little knowledge about the registration of domain names and who do not know that it is possible to register very similar domain names merely by altering the suffix. It is likely that there are many members of the target class who know little or nothing about the role of an accredited registrar.

88 Second, the recipients of the Notices will include many employees who had nothing to do with setting up or registering the domain name of the business or organisation in which they work and are likely to have little knowledge about the identity of the registrar with which their business or organisation dealt. For example, that can be seen in relation to Mr Allen and YarraTri.

89 Third, the Notice has an appearance similar to an invoice. As a result, in many businesses the Notice was likely to be directed to those responsible for paying bills rather than to those who decide whether the business wishes to acquire a “.com” domain name. As Finkelstein J said in .au Domain at [37], that increases the risk that the reader will have little or no knowledge about the registration of domain names and that it is possible to obtain registration of very similar domain names by altering the suffix. The Notice sent to George Archer Metals is an example of this. It was dealt with by Ms Archer who seems to have been both the receptionist and the accounts payable clerk. I infer from her evidence that she was not knowledgeable in relation to domain name registration and the significance of the “.com” and “.com.au” suffixes.

90 Fourth, while some class members are likely to have read the Notice with care because it invites or requests payment, it was sent to a broad cross-section of the public many of which are unlikely to have closely read it. Many recipients are likely to have been busy and to have dealt speedily with the Notice. The degree of attention that recipients gave to the Notice is also likely to reflect the fact that for medium to large businesses the sum of $249 for two years registration of a domain name is not a significant expenditure: see.au Domain at [37].

Was Domain’s conduct misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive?

91 The question is whether Domain’s conduct in sending out the impugned Notice misled or deceived or was likely to mislead or deceive the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class to which the conduct was directed.

Domain’s contentions

92 Domain contended that its conduct did not have a tendency to lead the ordinary or reasonable member of the target class into error.

93 It noted that 235,887 of the offers it made to register “.com” domain names through the Notices have not been accepted and that the relevant “.com” domain names remain unused. On the basis that most business people pay their invoices it argued that the substantial majority of the persons who received a Notice understood it to be an offer to provide services rather than an invoice, because they did not pay it.

94 Domain submitted that the starting point for the assessment of whether the Notice is misleading is its language and form. It argued that:

(a) the Notice is a single page and that no issue of terms hidden later in a large document arises;

(b) the Notice states in large print that it is an offer to sell that domain name, for two years, to the recipient together with related services, and it identifies the relevant domain name with the suffix “.com”. It said that the Notice contains an accurate description of what it is: an offer to provide domain name registration services coupled with an order and payment slip; and

(c) the Notice does not contain a statement that it is a tax invoice, which a reasonable business person would know was required for any invoice for a taxable supply. Nor does the Notice contain a “due date” for payment which is an almost invariable part of any invoice. Domain noted that the absence of a due date is one of the many differences between the impugned Notices and the conduct considered in au. Domain.

It submitted that when the Notice is read as a whole, even casually, it is not misleading. It contended that the Notice says what it is and identifies the offer made and that the reasonable or ordinary class member is unlikely to be misled or deceived by it.

95 Domain made a number of contentions as to the evidence adduced by Consumer Affairs.

96 It argued that, while it can be accepted that each of Ms Demetriou, Mr Allen, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs formed a mistaken impression in relation to the Notice, that was for a range of different reasons. It said that their differing evidence is important to considering the significance of the misapprehension they suffered and that their misapprehension was not caused by the Notice but by mistaken assumptions they made.

97 Domain made submissions as to asserted deficiencies in the evidence of the witnesses and submitted that it does not establish that the Notices had a tendency to mislead or deceive, including that:

(a) Mr Allen noticed the reference number, payment options and that the Notice was addressed to YarraTri but apparently did not read or take in the effect of the surrounding words of the Notice. Domain submitted that his affidavit does not invite the argument that Mr Allen missed the “fine print”, and is instead evidence that he took in only parts of a one-page document. Domain also argued that Mr Allen knew that there was a difference between a “.com” and a “.com.au” domain name because he did not express surprise when Mr Jacobson asked him if YarraTri’s website had a “.com.au” domain name or a “.com” domain name;

(b) Domain argued that it was not reasonable for Ms Demetriou to conclude that the Notice was an invoice from Domain when the Notice did not have the information required of an invoice, was not expressed to be for renewal of an existing service, and contains words to the effect that it was an offer to register. It said that Ms Demetriou knew who supplied the domain name for her business and it was not Domain. It also argued that the fact that Ms Demetriou later reviewed the Notice (more than two years later) and saw that it was not an invoice for her existing “com.au” domain name shows that it was not unclear or tricky;

(c) the process which Ms Archer described is “odd” because she noticed only some parts of the information in the Notice, she missed adjacent information which was in bolder and bigger print, and she did not observe that the Notice did not include the words “tax invoice” or a due date for payment. She knew that Crazy Domains supplied George Archer Metals with its domain name and her comparison of Crazy Domains’ invoice and the Notice objectively ought to have shown up the differences. Domain also argued that when Ms Archer later reviewed the Notice she realised that the domain name stated on it was www.archermetals.com, not George Archer Metals’ existing domain name, which shows that the Notice was not misleading;

(d) it was not reasonable for Mr Hopkins to conclude that the Notice was an invoice from Domain because he knew who supplied Top Steel’s domain name and that it was not Domain. It argued that Mr Hopkins did not read significant parts of the one-page Notice in a reasonable manner and that his misapprehension arises not from any misleading conduct but from the fact that he misread the words of the Notice or reached a conclusion without reading its words; and

(e) if Ms Nobs had read the large bold type of the Notice she could not reasonably have formed the view that the Notice looked like a “renewal notice”. It submitted that had Ms Nobs followed her usual practice of noting the “due date” of each invoice by writing it in her diary she would have seen that the Notice did not have a “due date”. It argued that Ms Nobs later realised that the Notice offered registration of a domain name different to Trend Vend’s existing domain name which shows that the Notice was not misleading.

98 Domain argued that notwithstanding that each of Ms Demetriou, Mr Allen, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs initially formed a mistaken impression, when they later reviewed the Notice they understood that it was not an invoice. It submitted that this is cogent evidence that the Notice was not likely to mislead or deceive. It also contended that the evidence shows that each of Ms Demetriou, Mr Allen, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs understood the difference between a “.com” and a “.com.au” domain name because, when they became aware of their mistaken impression, it was unnecessary that the difference be explained to them.

Consideration

99 I do not accept Domain’s contentions. In my view Domain’s conduct in sending out the Notices constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct or, at least, conduct likely to mislead or deceive, in breach of s 18(1) of the ACL.

100 First, I reiterate the matters set out at [82] to [90] above. I consider Domain sought to attribute a higher level of knowledge and perspicacity to the ordinary or reasonable class member than is appropriate in the circumstances. In my view it is likely that many class members will:

(a) not understand the significance of the difference between “.com.au” or “.com” domain names and/or that it is possible to obtain separate registration for very similar domain names by using a “.com.au” or “.com” suffix;

(b) have little knowledge about the role of an accredited registrar for domain name registration or the identity of the registrar in relation to the domain name of the business or organisation in which they work. I note again that Mr Allen did not know the name of the registrar of YarraTri’s domain name, and I would be surprised if there were not many people in the class in a similar position; and

(c) not have closely read the Notice. Some, like several of Consumer Affairs’ witnesses, are busy small business owners. Some, particularly people in medium to large businesses, will not have read the Notice closely because the cost of registration is insignificant for a business of that size. Some will be accounts staff working through piles of invoices and trying to shift their work as speedily as they can. As Finkelstein J said in .au Domain at [37], where such a document is dealt with by the accounts department there is a greater risk that the reader will have little or no knowledge about the registration of domain names or the fact that it is possible to obtain registration of very similar domain names. A brief reading of the Notice will not necessarily alert the reader to the difference between the “.com” domain name in the Notice and the existing domain name of the business or organisation.

101 Second, while the text of the Notice is central, consideration of the Notice must occur in the context of the whole of the evidence. The Court is not confined to examining the Notice in isolation and it must have regard to all of Domain’s conduct in relation to it: Butcher at [109], cited with approval in Campbell at [102].

102 Domain sent out 437,819 unsolicited Notices to 301,083 persons around Australia who were the registrants of a “.com.au” domain name. Domain sought to characterise the Notices as an offer to provide services but businesses that make unsolicited offers usually do so through some form of advertisement, such as a brochure or flyer with features designed to attract and persuade the reader. Domain accepted that the Notices are functionally equivalent to an advertising flyer but they looked nothing like a brochure or flyer. It is quite unusual for a business to make an unsolicited offer by way of a bland document like the Notice with the features of an invoice and none of the usual features of a brochure or flyer. In my view that plays into the tendency of the Notices to mislead.

103 Third, a number of the components of the Notice give rise to the impression that it is an invoice rather than a form of advertising or an offer to provide services. Using the Notice sent to YarraTri as an example (see [36] above), it:

(a) is on Domain letterhead - as would appear on an invoice but would not usually appear on an advertising flyer;

(b) contains a reference number in the body of the document and on the payment slip - which suggests that the Notice refers to an existing registered customer: see .au Domain at [36];

(c) is specifically addressed and directed to YarraTri - unlike most advertising flyers which are not so addressed or personalised;

(d) is for the domain name - “yarratri.com” - a domain name very similar to the existing registered domain name of the business. A person reading the Notice quickly, or perhaps even more studiously, is unlikely to notice that the “.com” domain name offered for registration is different to the existing registered domain name: see au. Domain at [36];

(e) sets out a list of services included with the $249 price, the primary service being two years domain name registration - for many businesses that will be a relatively insignificant amount which may mean the Notice will be given a low level of attention;

(f) provides payment options of direct deposit, credit card or by mail; and

(g) contains a tear-off payment slip towards the bottom of the Notice with the words “Please enclose the payment slip, together with your cheque or money order, made payable to: Domain Register Pty Ltd, Level 3, 480 Collins Street, Melbourne VIC 3000”, as well as providing options for online payment by credit card and by direct deposit.

104 With these features, and the absence of any of the usual elements of an advertising brochure or flyer, the ordinary or reasonable class member is likely to be left with the impression that it is an invoice.

105 Fourth, Domain relied on the text of the Notice to support a submission that the Notice is just an “invitation to register”. However, the Notice is styled so as to de-emphasise that information. In small and hard to read font just before the tear-off payment slip the Notice stated:

This is an invitation to register, disregard this letter if you are not the proprietor or if you do not wish to register. Terms and conditions of service can be found at www.domainregister.com.au/terms.html.

106 Many class members are likely to have missed that information, to have given it only brief attention, or to have not taken it in sufficiently to understand its significance. Because it was given no prominence this information did not operate to qualify or dispel the misleading impression created by the appearance of the Notice. I am confirmed in this view by the fact that Ms Demetriou, Mr Allen, Ms Archer and Ms Nobs either missed this information in the Notice or did not take in its significance.

107 There was no suggestion in Consumer Affairs’ case that Domain acted with an intention to mislead or deceive, and such intention is not an element of the contravention alleged. Domain gave no explanation as to why it de-emphasised this information. It is, however, plain that Domain chose to give that significant information no prominence and that doing so was to its commercial benefit. In such circumstances it may be more readily inferred that the Notice gives or was likely to give the misleading impression that it is an invoice: TPG at [55]-[56].

108 Fifth, it is not determinative but I give some weight to the fact that Mr Allen, Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer and Ms Nobs misunderstood the Notices as invoices for renewal of the registration of their existing “.com.au” domain names rather than offers to supply registration of a “.com” domain name. The gist of their evidence is that each did so because the Notice was addressed to their business or organisation, it contained a reference number, it referred to a two-year period of domain name registration, it referred to a domain name very similar to the domain name of their business or organisation, and it had payment options in relation to the two years of domain name registration.

109 Ms Nobs also said that she did not notice that there was no “.au” at the end of the domain name set out in the Notice (which she thought to be an invoice). The other witnesses did not say whether they noticed that or not. I infer that they either did not notice the absence of the “.au” suffix or they did not understand the significance of its absence.

110 Mr Allen, Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer and Ms Nobs are from apparently different walks of life, of different ages and with different levels of education. Ms Demetriou and Ms Nobs run their own small businesses, Mr Allen is a supervisor at an accounting and consultancy firm and volunteers as the Treasurer at a sporting club, and Ms Archer works as a receptionist and accounts payable clerk in her family’s stainless steel business. Each of them was left with the impression that the Notice was an invoice. Domain chose not to challenge their evidence by cross examination and its submissions as to the deficiencies in their evidence are overstated. It was open for Domain to put on its own evidence in regard to the effect of the Notices and it chose not to do so.

111 I do not, though, give much weight to Mr Hopkins’ evidence. He knew that Domain was not the accredited registrar for his domain name of his business and his stated reasons for misunderstanding the Notice to be an invoice do not centrally relate to the Notice’s appearance.

112 Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer and Ms Nobs did eventually realise that the Notice referred to a “.com” domain name rather than their existing “.com.au” domain name. However, Ms Demetriou did not realise until she received some business advice, Ms Archer did not realise until she received another Notice from Domain only four months after paying (what she thought was) Domain’s invoice, and Ms Nobs only realised when she received a renewal notice in relation to her existing domain name. Those circumstances are quite different to the circumstances in which they received the Notice in the first place and paid the specified charge. The question is whether the Notice, in the circumstances in which it was received and considered by the recipient, had a tendency to leave the misleading impression that it was an invoice, not whether the recipient did or was likely to later realise his or her error. By that time Domain’s conduct had already drawn the recipient into its marketing web.

113 For similar reasons there is little substance in Domain’s contention that the evidence shows that Ms Demetriou, Mr Allen, Ms Archer, Mr Hopkins and Ms Nobs understood the difference between a “.com” and a “.com.au” domain name because, when they became aware of their mistaken impression, it was unnecessary that the difference be explained to them. Mr Allen and Mr Hopkins did not understand that they had mistakenly acquired a “.com” domain name until they spoke to Mr Jacobson. I infer that the difference between the domain names only became apparent to them through that conversation. Ms Demetriou, Ms Archer and Ms Nobs realised that there was a difference between the “.com” domain name on their Notice and their existing “.com.au” domain name but only some months later and after further events had taken place. As I have said, the central question is whether the Notice had a tendency to mislead in the circumstances in which it was received and considered by the recipient, not whether the recipients were likely to later realise the true position.

114 However, I accept Domain’s contention that the substantial majority of the persons to whom it sent a Notice did not understand it to be an invoice, because only 21,089 of the 301,083 persons to whom Domain sent a Notice proceeded to register a “.com” domain name through it. I am nevertheless satisfied that Domain’s conduct in sending out the unsolicited Notices was likely to mislead or deceive many members of the class. The number of recipients actually misled can only be a subset of the 21,089 persons who acquired a “.com” domain name, comprising a not insignificant number of the class, and I consider the Notice was likely to mislead or deceive a greater number than those actually misled. There is no requirement for Consumer Affairs to demonstrate that class members have actually been misled or deceived in order to establish a contravention: Puxu at 198; Google at [6].

115 I am satisfied that Domain’s conduct in sending out the unsolicited Notices was conduct which is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 18 of the ACL.

THE ALLEGED BREACH OF SECTION 40(3) OF THE ACL

The legislation

116 Section 40 of the ACL is in Division 2 which is headed “Unsolicited supplies”. It provides:

Assertion of right to payment for unsolicited goods or services

(1) [Unsolicited Goods] A person must not, in trade or commerce, assert a right to payment from another person for unsolicited goods unless the person has reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to the payment.

(2) [Unsolicited Services] A person must not, in trade or commerce, assert a right to payment from another person for unsolicited services unless the person has reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to the payment.

(3) [Invoice for unsolicited goods or services] A person must not, in trade or commerce, send to another person an invoice or other document that:

(a) states the amount of a payment, or sets out the charge, for supplying unsolicited goods or unsolicited services; and

(b) does not contain a warning statement that complies with the requirements set out in the regulations;

unless the person has reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to the payment or charge.

(4) [Onus of proof] In a proceeding against a person in relation to a contravention of this section, the person bears the onus of proving that the person had reasonable cause to believe that there was a right to the payment or charge.

117 The definition of “services” in s 2 of the ACL is broad and relevantly states:

services includes:

(a) any rights (including rights in relation to, and interests in, real or personal property), benefits, privileges or facilities that are, or are to be, provided, granted or conferred in trade or commerce;…

(Emphasis added in bold.)

118 The definition of “unsolicited services” in s 2 provides that it “means services supplied to a person without any request made by the person or on his or her behalf” (emphasis added in italics). On its face this limits “unsolicited services” to services already provided whereas the definition of “services” is not so restricted.

119 Regulation 78 in Part 6 of the Competition and Consumer Regulations 2010 (Cth) (the Regulations) sets out the prescribed warning statement to which s 40(3) refers. It provides:

(a) the warning statement must include the text “This is not a bill. You are not required to pay any money.”;

(b) the text must be the most prominent text in the document.

120 Section 10 of the ACL is a deeming provision that relevantly provides:

Asserting a right to payment

(1) [Taking actions to obtain payment] A person is taken to assert a right to payment from another person if the person:

…

(e) sends any invoice or other document that:

(i) states the amount of the payment; or

(ii) sets out the price of unsolicited goods or unsolicited services; or

(iii) sets out the charge for placing, in a publication, an entry or advertisement;

and does not contain a statement, to the effect that the document is not an assertion of a right to a payment, that complies with any requirements prescribed by the regulations.

(Emphasis in original.)

121 The requirements prescribed by the regulations are set out in reg 77 as follows:

For paragraph 10(1)(e) of the Australian Consumer Law, the following requirements are prescribed:

(a) the statement must include the text “This is not a bill. You are not required to pay any money.”;

(b) the text must be the most prominent in the document.

The proper construction of “unsolicited services” for the purposes of s 40(3)

122 Section 40(3) proscribes the conduct of sending an “invoice or other document” that states the amount of a payment or charge for supplying unsolicited goods or services and which does not contain a warning statement that complies with the requirements set out in the regulations, unless the person has a reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to the payment or charge.

123 It is uncontentious that the Notices did not contain the specified warning statement. Domain argued that the Notices did not need to contain such a statement because the Notice was not an “invoice or other document” asserting a right to payment for unsolicited services. Its primary argument is that “unsolicited services” in s 40(3) does not include services that are yet to be provided. It notes that “unsolicited services” is defined in s 2 of the ACL to mean “services supplied to a person without any request made by the person or on his or her behalf” (emphasis added). It is common ground that at the time Domain sent out the Notices it had not supplied any domain registration services to the recipients of the Notices.

124 In .au Domain at [54]-[55] Finkelstein J considered the meaning of “unsolicited services” in s 64 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA), a predecessor to s 40. Section 64 relevantly provided:

Assertion of right to payment for unsolicited goods or services or for making entry in directory

(1) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, assert a right to payment from a person for unsolicited goods unless the corporation has reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to payment.

(2A) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, assert a right to payment from a person for unsolicited services unless the corporation has reasonable cause to believe that there is a right to payment.

…

(5) For the purposes of this section, a corporation shall be taken to assert a right to a payment from a person for unsolicited goods or services… if the corporation:

…

(e) sends any invoice or other document stating the amount of the payment or setting out the price of the goods or services… and not stating as prominently (or more prominently) that no claim is made to the payment, or to payment of the price or charge, as the case may be.

125 The definitions of “services” and “unsolicited services” in the TPA and the ACL are relevantly the same.

126 In .au Domain Finkelstein J held that s 64(2A) of the TPA had no application to services which were yet to be provided. His Honour said (at [54]-[55]):

… “Unsolicited services” are confined to services which have been supplied in the past, but the definition of “services” includes those services which may be supplied in the future. Such an inconsistency cannot be allowed. The inconsistency can only sensibly be avoided by either: (1) importing into the meaning of “unsolicited services” that part of the definition of “services” that is otherwise consistent with the meaning of “unsolicited services”; or (2) not incorporating the meaning of “services” into the definition of “unsolicited services” at all on the basis that there is a contrary intention to its incorporation. It is unnecessary for me to resolve which approach is correct. It is sufficient for the purposes of this case to hold that, on either approach, s 64(2A) has no application to unprovided services.

The construction which I favour means that s 64(2A) will operate in the same way as regards unsolicited services as it does in relation to unsolicited goods. “Unsolicited goods” are defined in s 4 to mean “goods sent to a person without any request made by him or her or on his or her behalf”. The definition of “goods” does not refer to goods to be supplied. As the respondents point out, if Pincus J’s later interpretation of s 64(2A) were to be applied the prohibition against asserting a right to payment for unsolicited services would be broader than the prohibition against asserting a right to payment for unsolicited goods. There is no obvious reason why this should be so.

127 In Nominet UK v Diverse Internet Pty Ltd (2004) 63 IPR 543; [2004] FCA 1244 (Nominet UK) at [153] French J (as his Honour then was) followed Finkelstein J’s construction of s 64(2A). His Honour said that while Finkelstein J’s interpretation “may be debatable” he considered it to be “clearly open”, and considered that he should not depart from it.

128 Consumer Affairs contended that on a proper construction of s 40(3) the prohibition on sending an “invoice or other document” that states the amount of a payment or charge for supplying unsolicited services extends to services which have not been supplied at that time.

129 First, Consumer Affairs argued that the activating verb in s 40(3) is to “send” an invoice or other document, not the supplying of a service. It submitted that the word “supplying” is used to describe the object of sending the invoice or other document. It contended that s 40(2) proscribes a person from asserting a right to payment for unsolicited services and s 40(3) proscribes sending an invoice or an invoice-like document for unsolicited services.

130 Consumer Affairs argued that 40(3) is intended to complement ss 40(1) and (2) rather than to provide effectively the same outcome. It said that “unsolicited services” in 40(3) has to include services to be provided so that that section has its own standalone area of influence, otherwise it is almost entirely consumed by s 40(2) and has no work to do. On its argument there is no temporal element to s 40(3) and it applies equally to services already provided and services to be provided in the future.

131 Second, it submitted that s 40(3) is a new provision and it is not burdened by the authorities relevant to s 40(2). It argued that in view of the differences between s 40 of the ACL and s 64 of the TPA the Court is not obliged to follow the meaning given to the expression “unsolicited services” in .au Domain and Nominet UK. It contended that:

(a) s 40 of the ACL is not in the same terms as s 64 of the TPA. It said that s 64 of the TPA is equivalent to s 40(2) combined with s 10 of the ACL and that 40(3) of the ACL is new. It submitted that s 64 focused on and prohibited “assert[ing] a right to payment from another person”, which is not the equivalent of s 40(3) of the ACL which focuses on and prohibits the conduct of “send[ing] to another person an invoice or other document”;

(b) s 40(2) of the ACL (like s 64(2A) of the TPA) prohibits asserting a right to payment for unsolicited services and it uses significantly different wording to s 40(3) of the ACL. It says that the use of the phrase “for supplying…unsolicited services” in subs 40(3)(a) more readily connotes a future supply of unsolicited services than the wording in s 64(2A);

(c) the TPA did not contain an equivalent provision to s 42 of the ACL which provides:

Liability of recipient for unsolicited services

If a person, in trade or commerce, supplies unsolicited services to another person, the other person:

(a) is not liable to make any payment for the services; and

(b) is not liable for loss or damage as a result of the supply of the services.

In written submissions Consumer Affairs said that the use of the phrase “supplied unsolicited services” in s 42 suggests that the ACL contemplates that the laws in relation to unsolicited services also apply to unsolicited services that are yet to be supplied. It argued that if “unsolicited services” only meant those services that have been supplied in the past, then Parliament would not have needed to say “supplied” unsolicited services in s 42.

132 Consumer Affairs submitted that, where ambiguity arises, a construction of s 40(3) which means that it is either redundant or only covers a subset of the conduct dealt with by s 40(2) should not be preferred: Project Blue Sky v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [71] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

Consideration

133 I do not accept Consumer Affair’s submissions. I say this, first, because:

(a) the term “unsolicited services” is defined in s 2 of the ACL to mean “services supplied” to another person. Including services which are to be supplied in the future into the definition of “unsolicited services” is irreconcilable with the definition’s use of the word “supplied”: .au Domain at [54]. The approach for which Consumer Affairs contended reads out the word “supplied” from the definition which does too much harm to the language;

(b) it would have been straightforward for Parliament to use similar words in the definition of “unsolicited services” as in the definition of “services” so that it extended to unsolicited services that “are to be supplied”. It did not do so;

(c) construing “unsolicited services” in s 40(3) to relate only to services already supplied is consistent with the prohibition in the section in respect to “unsolicited goods”. The prohibition on sending an “invoice or other document” in respect to unsolicited goods only applies to goods which have been supplied at the time of sending the invoice or other document; and

(d) treating unsolicited goods and services consistently accords with the language and the structure of ss 40(1), (2) and (3) and the definitions of “unsolicited goods” and “unsolicited services” in s 2 of the ACL. I was not taken to any apparent legislative purpose for treating unsolicited goods and services differently, or to any rational reason for doing so.

134 I accept that reading “unsolicited services” in s 40(3) as limited to services that have been supplied means that there is a substantial overlap between s 40(3) and s 40(2) read with s 10 of the ACL, but that redundancy is insufficient to justify ignoring the language of the definition.

135 The essence of Consumer Affairs' contention is that s 40(3) is a new provision and its interpretation should not be burdened by the authorities in relation to s 64(2A) of the TPA which it said is the predecessor to s 40(2). However, if “unsolicited services” in s 40(3) is construed to include services yet to be supplied, then the meaning of “unsolicited services” would be different in ss 40(2) and (3). The expression “unsolicited services” must be understood in context and in my view it should be given the same meaning in ss 40(2) and (3): Project Blue Sky at [69].

136 As a matter of statutory construction I am not persuaded that the decision in .au Domain is plainly wrong and I consider it should be followed: BHP Billiton Iron Ore Pty Ltd v National Competition Council (2007) 162 FCR 234; [2007] FCAFC 157 at [86]-[89] (Greenwood J).

137 Second, while it is true that s 40 uses different language to s 64 the definitions in the TPA of “services” and “unsolicited services”, which led to the result in .au Domain and Nominet UK, remain in relevantly the same terms. The ACL has an almost identical definition of “unsolicited services” and the definition of “services” has been slightly rearranged but is unaltered in substance.

138 Consumer Affairs overstated the differences between s 40 of the ACL and s 64 of the TPA. Section 40(3) establishes a specific prohibition, but it is essentially a re-enactment of s 64(2A) of the TPA read with s 64(5)(e). Section 64(2A) prohibited a corporation from asserting a right to payment from a person for unsolicited services, subject to a proviso. Section 64(5)(e) provided that a corporation shall be taken to assert a right to payment for unsolicited services if it sends out an invoice or other document which states the amount of the payment or sets out the price without prominently stating a required warning. Although there is a change in grammatical form in s 40(3), it also prohibits, in effect, the assertion of a right to payment for unsolicited services by “send[ing] to another person an invoice or other document” which states the amount of the payment or sets out the charge without stating the required warning.

139 Third, it is correct that the TPA did not contain a provision equivalent to s 42 but Consumer Affairs’ submissions in this regard are erroneous because it misstated s 42. The section does not say “supplied unsolicited services”, and instead uses the expression “supplies unsolicited services” (emphasis added). Consumer Affairs did not press this submission in oral argument.