FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Pokémon Company International, Inc. v Redbubble Ltd [2017] FCA 1541

ORDERS

THE POKÉMON COMPANY INTERNATIONAL, INC. Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Contrary to sections 18(1) and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law, the website at www.redbubble.com (the Redbubble Website) contained:

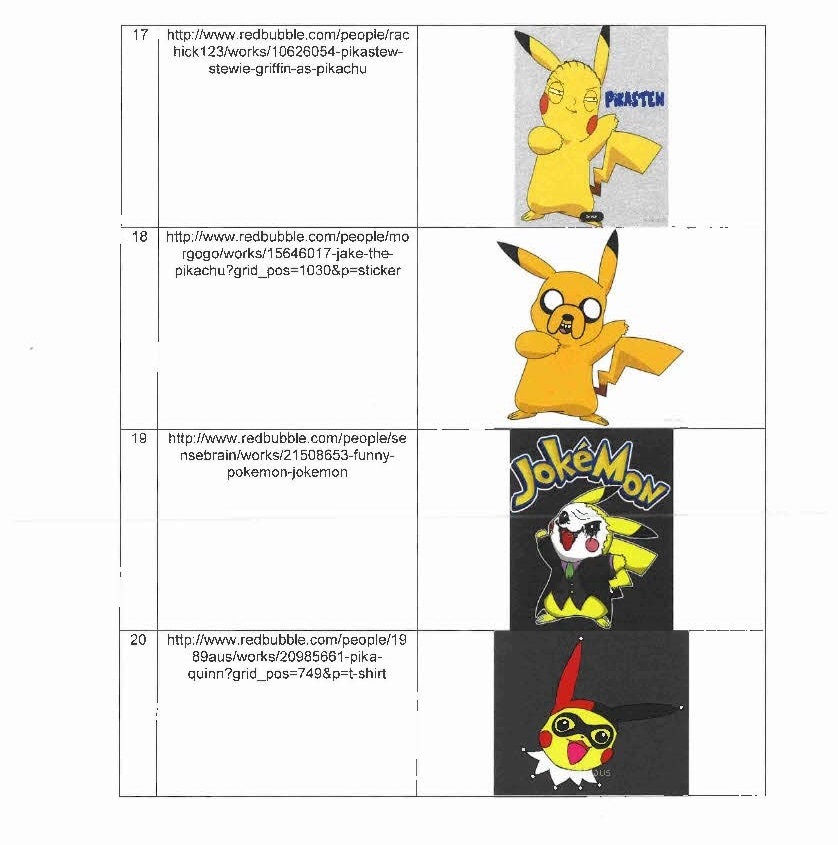

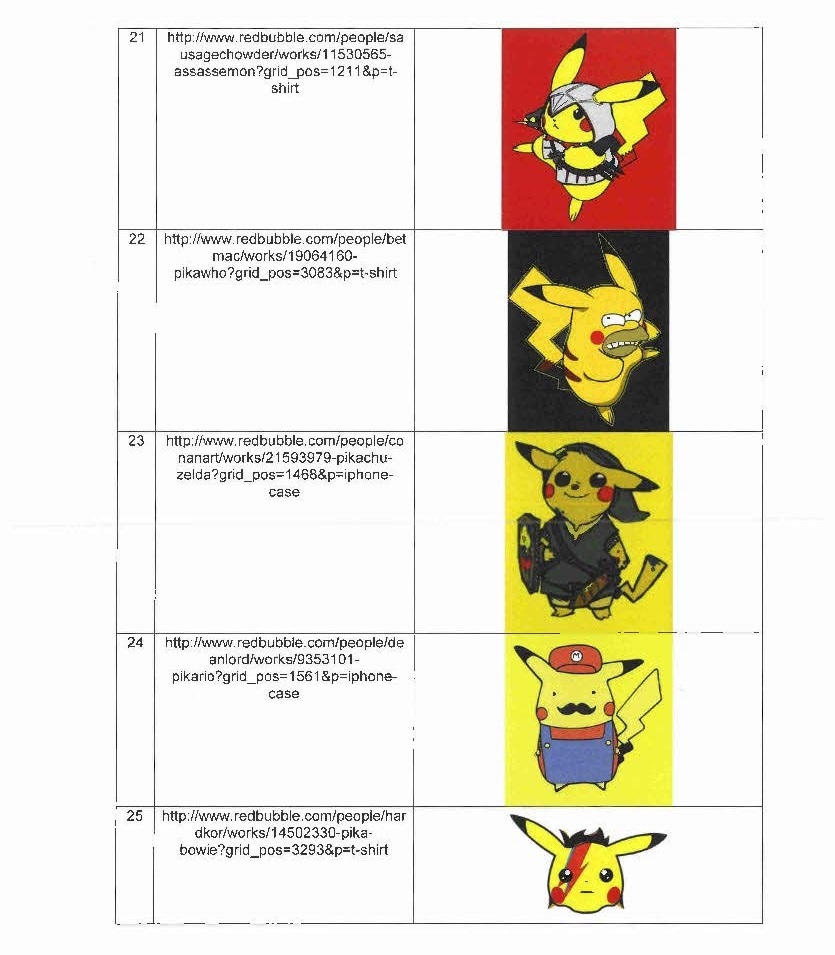

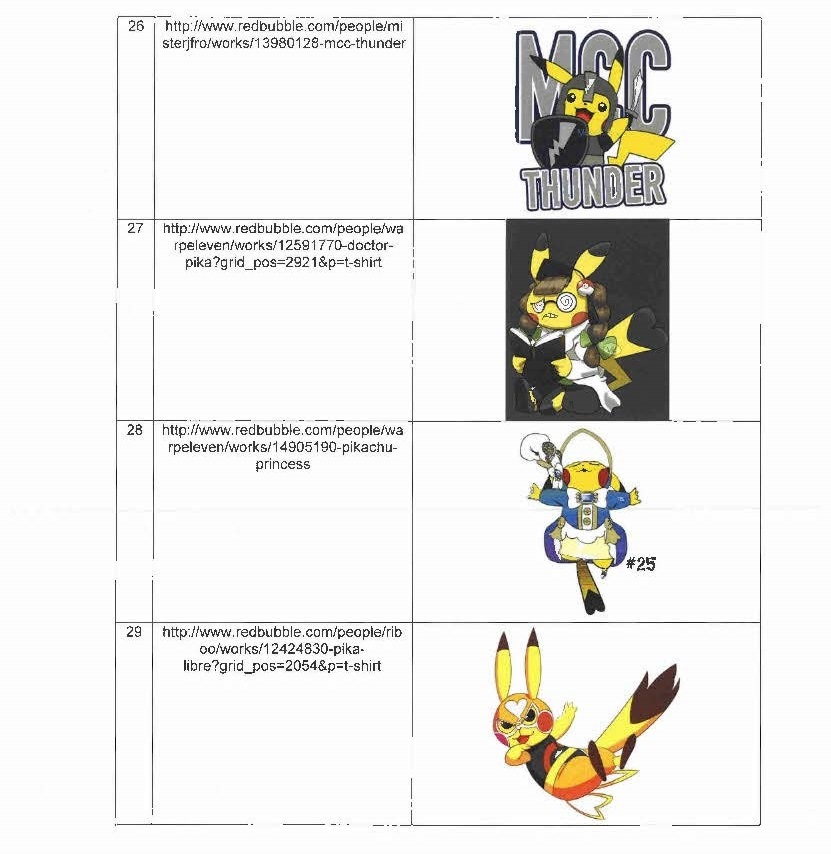

(a) representations that products available through the Redbubble Website bearing the words 'Pokémon' or 'Pokemon', or the character names or images set out in items 1-29 of Schedule 1 to this Order; and

(b) representations that products available through the Redbubble Website bearing the words 'Pokémon GO', 'Team Instinct', 'Team Mystic' or 'Team Valor', or the images set out in items 1-4 of Schedule 2 to this Order,

were supplied, licensed, associated, sponsored, approved or authorised by the Applicant or such other entity able lawfully to authorise Pokémon merchandise.

2. Contrary to sections 18(1) and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law, Google Shopping advertisements sponsored by the Respondent on the website at www.google.com (the Google Website) contained:

(a) representations that products available through the Google Website bearing the character names or images set out in items 1-12 of Schedule 1 to this Order; and

(b) representations that products available through the Google Website bearing the words 'Team Mystic' or the image set out in item 3 of Schedule 2 to this Order,

were supplied, licensed, associated, sponsored, approved or authorised by the Applicant or such other entity able lawfully to authorise Pokémon merchandise.

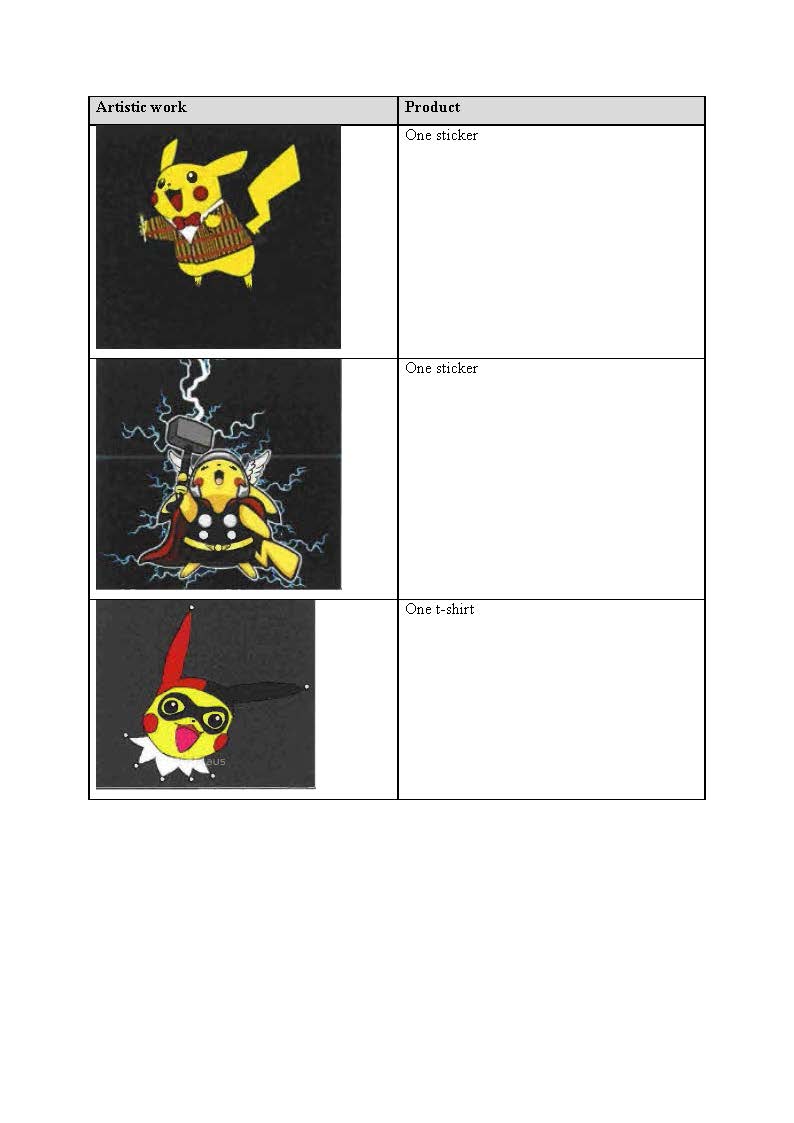

3. The Respondent infringed copyright in the artistic work in Schedule 3 to this Order by:

(a) making the artistic works in Schedule 4 to this Order available on the Redbubble Website;

(b) exhibiting, by way of trade on the Redbubble Website, articles bearing the artistic works in Schedule 4 to this Order when the Respondent knew, or ought reasonably to have known, by 25 November 2015 that:

(i) the making of the articles constituted an infringement of the copyright; or

(ii) in the case of imported articles, would, if the articles had been made in Australia by the importer, have constituted such an infringement; and

(c) authorising reproduction, in Australia, of the artistic works set out in Schedule 5 to this Order onto the products identified in that schedule.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

4. The Applicant be awarded nominal damages of $1.

5. The Respondent pay 70% of the Applicant's costs of the proceeding, excluding those costs referred to in Order 4 of the Orders made by Pagone J on 14 March 2017, such costs to be agreed or, in the absence of agreement, to be determined by the Court, in accordance with order 7 below.

6. If the parties reach agreement on the amount of costs to be paid, the parties are to notify the Court of such agreement and provide to the Court short minutes of appropriate orders to be made by consent.

7. If the parties have not reached agreement on the amount of costs to be paid by 12 noon on 19 January 2018, the parties are to notify the Court of the failure to reach agreement by 4pm on 19 January 2018, following which the amount of costs will be determined by the Court in accordance with the Costs General Practice Note (GPN-COSTS), such that:

(a) costs be awarded in a lump sum pursuant to r 40.02(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth);

(b) a Costs Summary, not exceeding 5 pages in length (omitting formal parts), be filed and served by 4pm on 16 February 2018;

(c) any Costs Response, not exceeding 4 pages in length (omitting formal parts), be filed and served by 4pm on 2 March 2018; and

(d) the proceeding be listed for a hearing before a Registrar of the Court to determine the amount of the lump sum at 9.30am on 12 March 2018 or such other time and date as the Court may order.

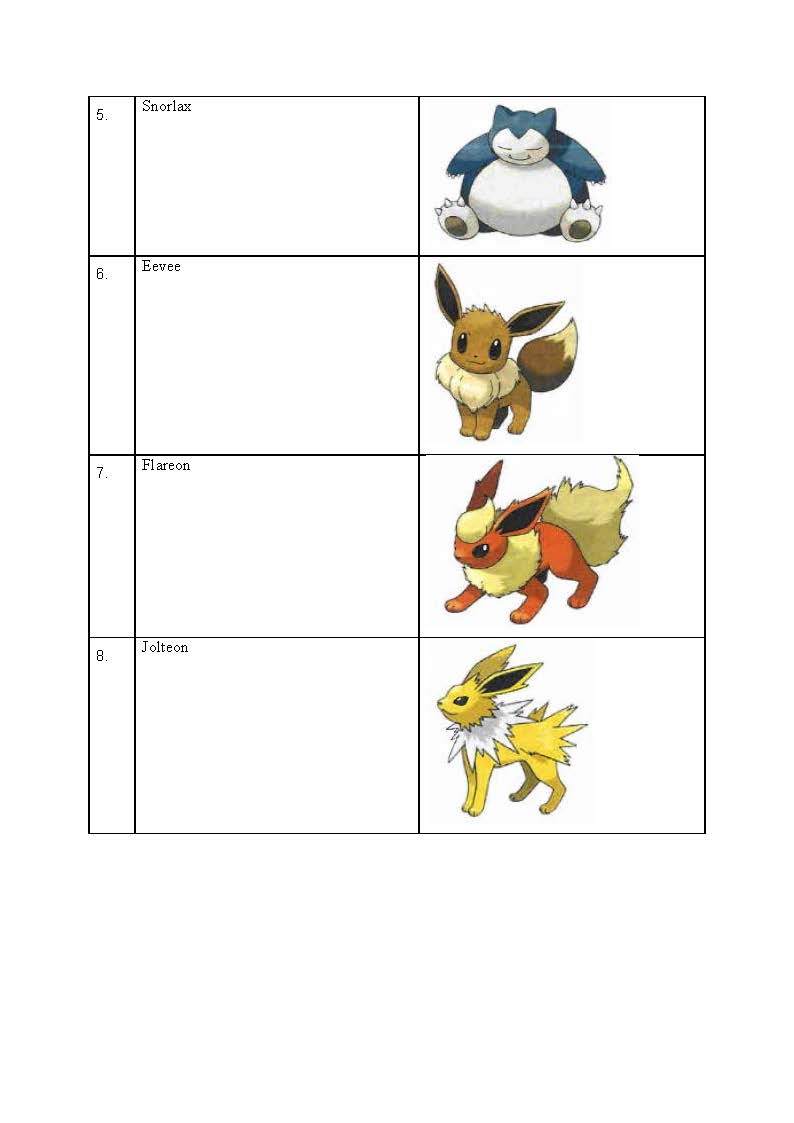

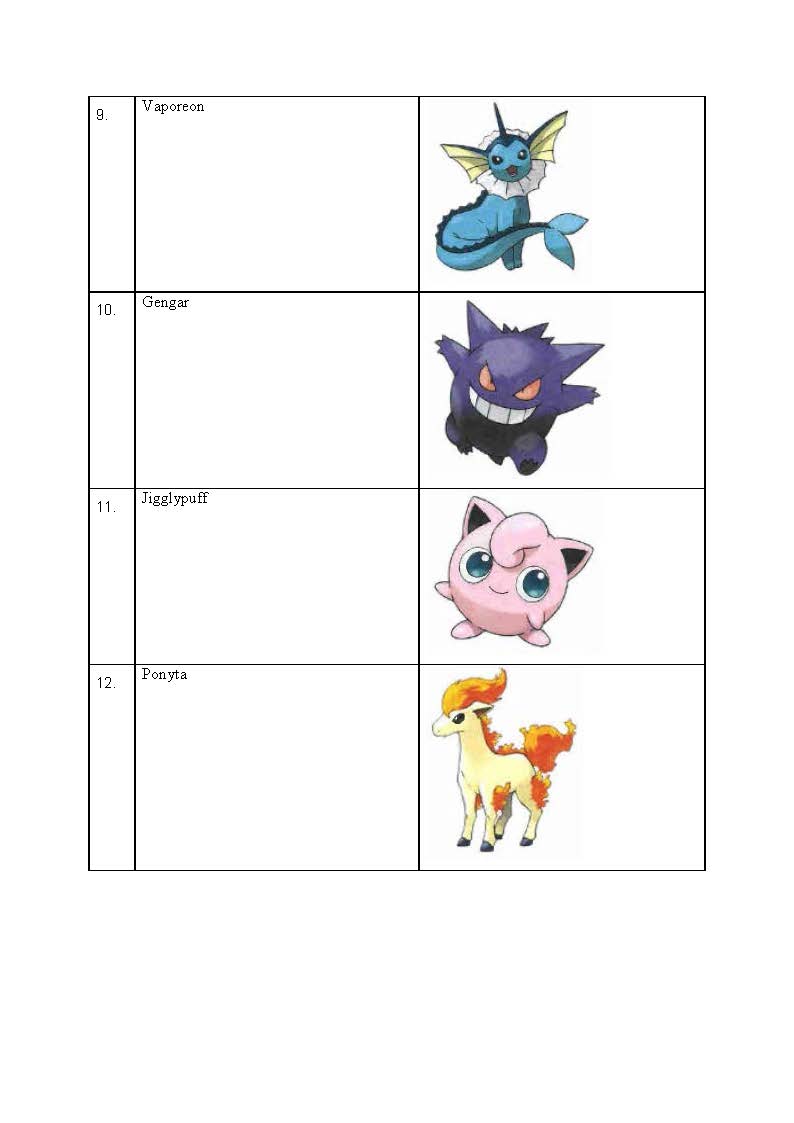

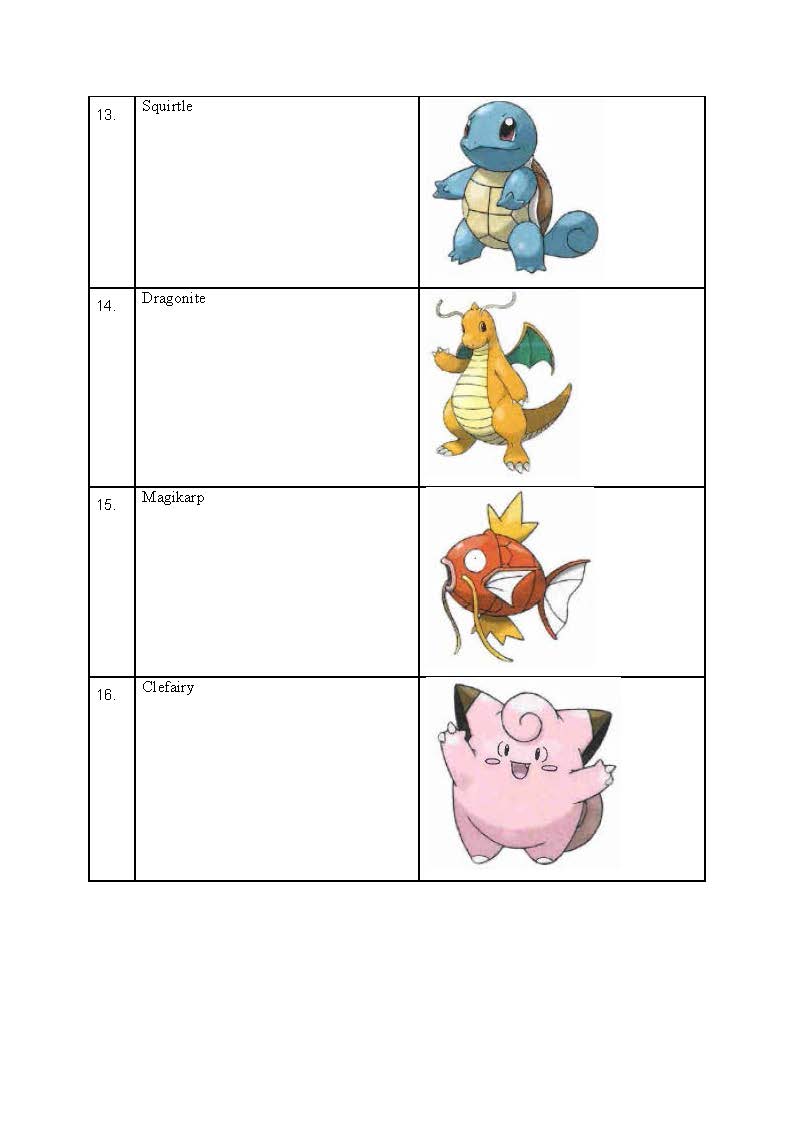

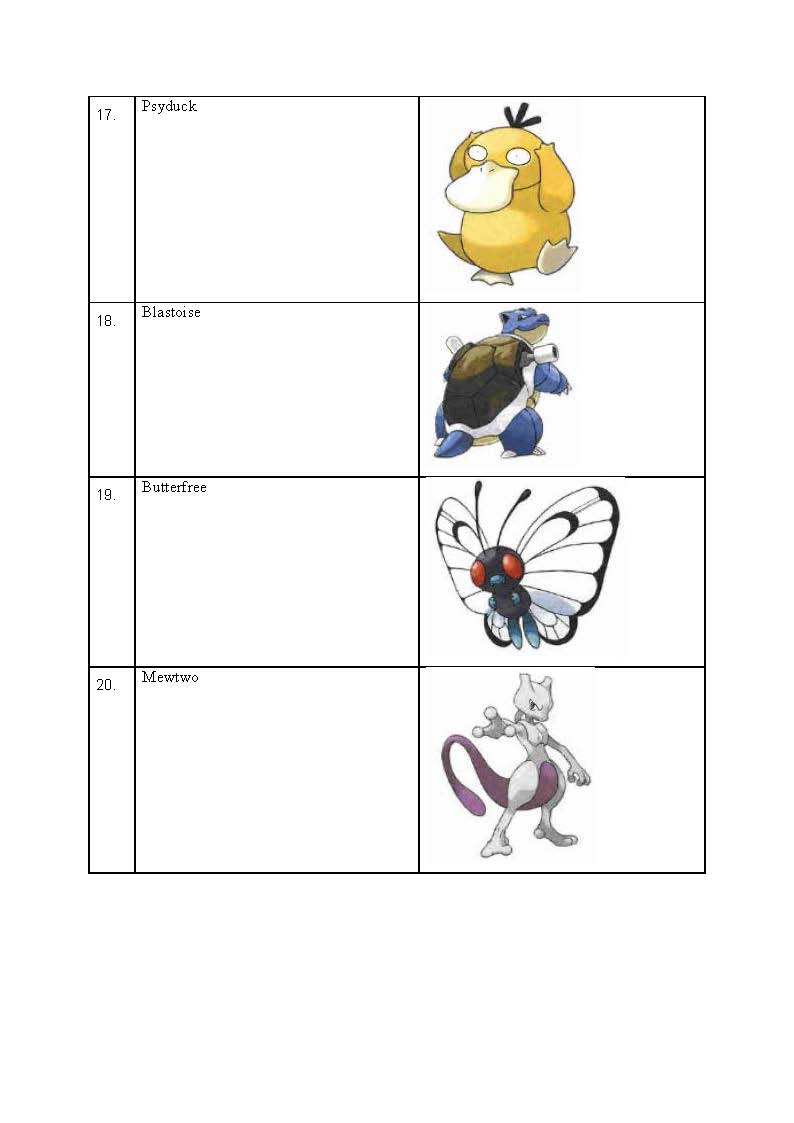

Schedule 1

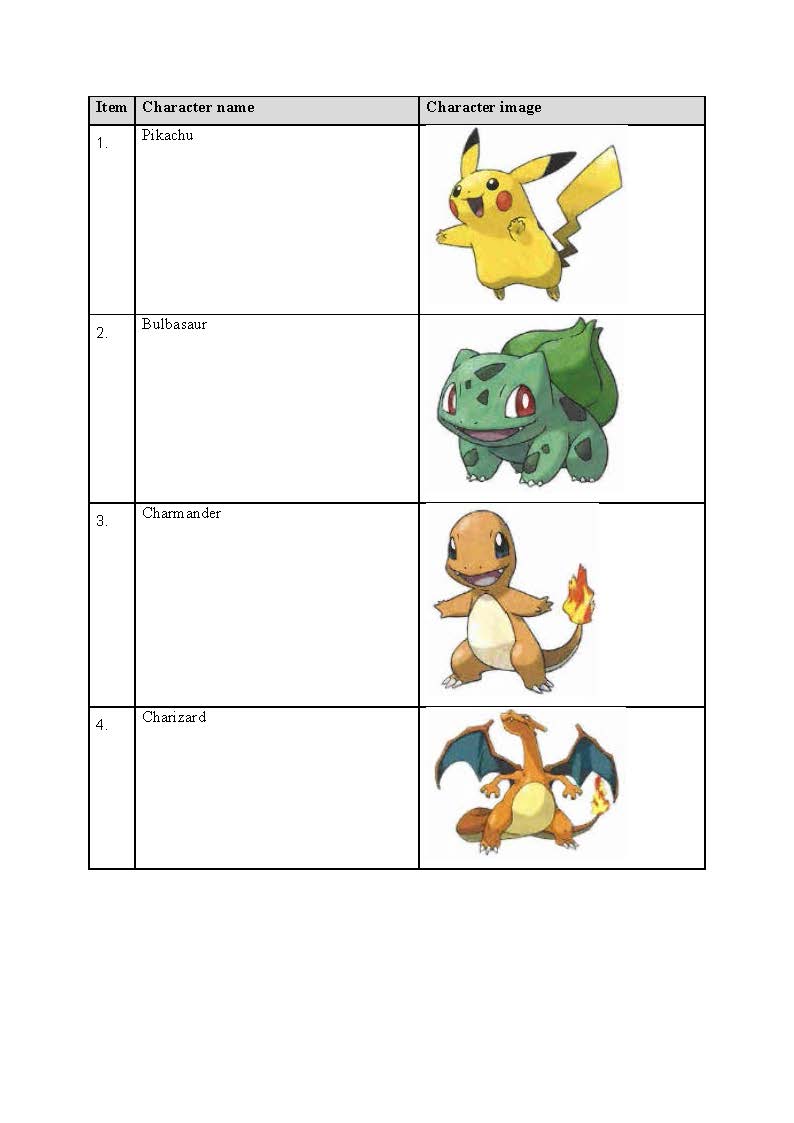

Schedule 2

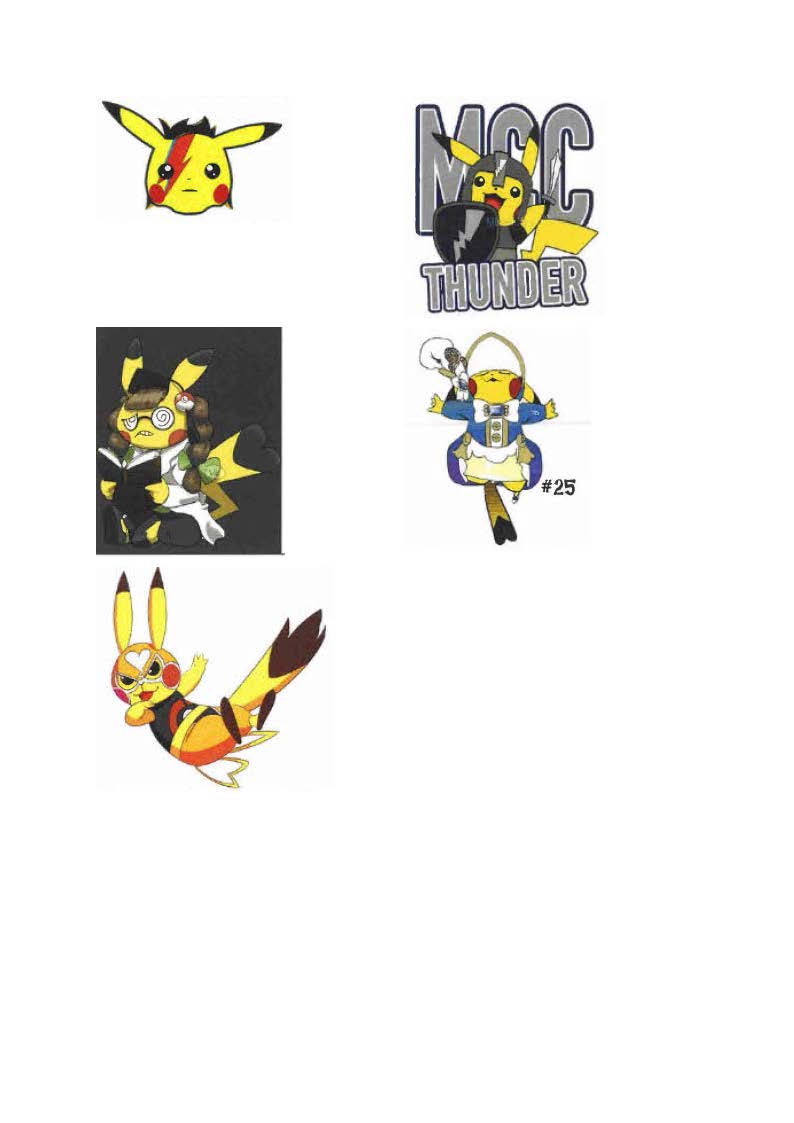

Schedule 3

Schedule 4

Schedule 5

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PAGONE J:

1 The Pokémon Company International, Inc. (“TPCi”) sues Redbubble Ltd (“Redbubble”) for alleged contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (“the Australian Consumer Law”) and for alleged breaches of copyright in the images of the Pokémon Pikachu character contrary to the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the Copyright Act”).

2 TPCi is a wholly owned subsidiary of The Pokémon Company which was established in Tokyo in April 1998 originally as the “Pokémon Center Co., Ltd”. That company was jointly owned by Nintendo Co. Ltd (“Nintendo”), Creatures Inc. and Game Freak Inc. and in April 1998 launched in Tokyo a specialist store for Pokémon merchandise which was subsequently extended across Japan. TPCi was originally incorporated in Delaware as Pokémon USA Inc. in February 2001 and since incorporation has overseen the licensing of Pokémon products outside of Asia including Australia, North America, South America, Europe and Africa. Its responsibilities include brand management, licensing of Pokémon merchandise, marketing of the Pokémon Trading Card Game, the animated Pokémon TV series, Pokémon movies and the official US Pokémon website.

3 In 1996 two Pokémon video games were released in Japan for the Nintendo Game Boy. These video games were first released in the United States in 1998, and subsequently in Australia in the same year under the names Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue, and featured Pokémon characters including Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Charmander, Charizard, Snorlax, Eevee, Flareon, Jolteon, Vaporeon, Gengar, Jigglypuff, Ponyta, Dragonite, Magikarp, Clefairy, Psyduck, Blastoise, Butterfree, Mewtwo, Vulpix and Venusaur. A wide variety of related Pokémon products were launched following the release of the video games including the Pokémon Trading Card Game, an animated TV series, movies and spin-off video game titles. The animated TV series features the Pokémon characters in the adventures of a 10 year old boy named Ash and his best friend Pikachu. Pokémon’s proceeding against Redbubble is confined to 29 of approximately 800 characters in the Pokémon universe which all have invented or concocted names that are not descriptive or generic, namely: Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Charmander, Charizard, Snorlax, Eevee, Flareon, Jolteon, Vaporeon, Gengar, Jigglypuff, Ponyta, Dragonite, Magikarp, Clefairy, Psyduck, Blastoise, Butterfree, Mewtwo, Vulpix, Sylveon, Lucario, Togepi, Umbreon, Leafeon, Glaceon, Espeon and Venusaur.

4 Redbubble Pty Ltd was founded in 2006 in Melbourne by Mr Martin Hosking, together with Mr Peter Styles and Mr Paul Vanzella, for the purpose of implementing a business idea of creating an internet marketplace throughout the world for a “print-on-demand” personalisation service for customers who wanted to purchase a product with an image or word which had been created by an artist or designer. Mr Hosking gave evidence in the proceeding and described the driving force behind the Redbubble business model as stemming from the idea of an online marketplace where designers could upload and sell their designs. On 2 February 2007 Redbubble officially launched the website at www.redbubble.com as the primary platform for the Redbubble Marketplace. It purchased the domain name in 2006 as the primary brand and domain for the Redbubble Marketplace and, according to Mr Hosking, was the first website on which artists could sell directly to customers, maintain copyright in their works, regulate their own margins, and choose the products which could be sold bearing their artworks. A blog was established at about the same time as the Redbubble website was launched.

5 An aspect of the business plan of the Redbubble Marketplace involved the means to fulfil the sale of products with an image or design uploaded onto the website by the designer or artists. The Redbubble Marketplace, in general terms, was conceived to operate by enabling artists and designers (who for convenience will usually be referred to as “the artists” without needing in this proceeding to make any qualitative finding about them as artists or designers) to upload work onto the Redbubble website which could then be applied by others (who for convenience will usually be referred to as the “fulfillers”) on products such as t-shirts, mugs and other such consumer items for sale. The Redbubble Marketplace began with only one fulfiller based in Horsham, Victoria but soon included fulfillers in other parts of the world, particularly in the United States of America, as the Redbubble website customer base grew. Redbubble experienced rapid growth between 2011 and 2015, growing from a gross transaction value of $6 million in the 2011 financial year to $88.4 million in the 2015 financial year. In April 2015 it raised $15.5 million in new capital from a group of investors to accelerate its international expansion plans and to fund other growth initiatives. On 16 May 2016 it listed on the Australian Stock Exchange and raised $30 million through an initial placement offer from the issue of new shares and a further $9.8 million from the sell-down of shares owned by existing investors. Redbubble’s market capitalisation had reached $267.7 million at the date of listing.

6 Redbubble conceded, and it was the direct evidence of Mr Hosking, that one of the risks identified from the development of the business plan was that those uploading material on the Redbubble Marketplace might infringe copyright or might upload illegal material. Redbubble sought to mitigate those risks by requiring those uploading material to agree to Redbubble’s terms of service before uploading content to the Redbubble website by terms which included (a) explicitly acknowledging that copyright protected or illegal material would not be uploaded to the Redbubble marketplace and (b) providing an indemnity to Redbubble for any copyright infringement or other illegal activity. Redbubble also established other procedures and policies which will be considered below.

7 It may be convenient to deal first with the claims by TPCi that Redbubble has breached provision of the Australian Consumer Law. Redbubble admitted that it is subject to the prohibition in Schedule 2 of the Australian Consumer Law: see s 131. Section 18(1) of Schedule 2 of the Australian Consumer Law provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

Sections 29(1)(g) and (h) provide respectively:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

[…]

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation;

[…]

Pokémon alleges that Redbubble has contravened each of these provisions by representations appearing on links it sponsors on Google and on Redbubble’s website.

8 There was substantial agreement between the parties about the details of the business operated by Redbubble in respect of which infringements were alleged. In general terms the parties agreed that the third parties described as “artists” may become registered members on the Redbubble website by visiting the website and setting up an account. The artists were then able to upload material on the Redbubble website, which Pokémon described in paragraph 32 of its statement of claim as “Redbubble artworks”, and which Redbubble agreed was uploaded on its website, although Redbubble disputed that the proper description of the material uploaded was “Redbubble artworks”. Redbubble, in other words, disputed the implication in the description that the artwork belonged to Redbubble or that Redbubble was responsible for what was uploaded onto its website. In large part such disputes stemmed from the structure of the pleadings but did not reveal substantial disagreement about the underlying process of Redbubble’s business or of the facts in the proceeding. The parties agreed that those described as artists uploaded work described as artwork onto the portfolio section of the artist’s account of the Redbubble website, and the parties agreed that the uploading occurred on the Redbubble website and that the material was saved to servers used by Redbubble which were located outside of Australia. The parties also agreed that it was a condition of registration that the artist agreed to be bound by the user agreement between the artist and Redbubble which specified, amongst other things, that the artist owned all copyright in the content of the work or had permission to use the content and all of the rights required to display, reproduce and sell the content of the work which was uploaded by the artist.

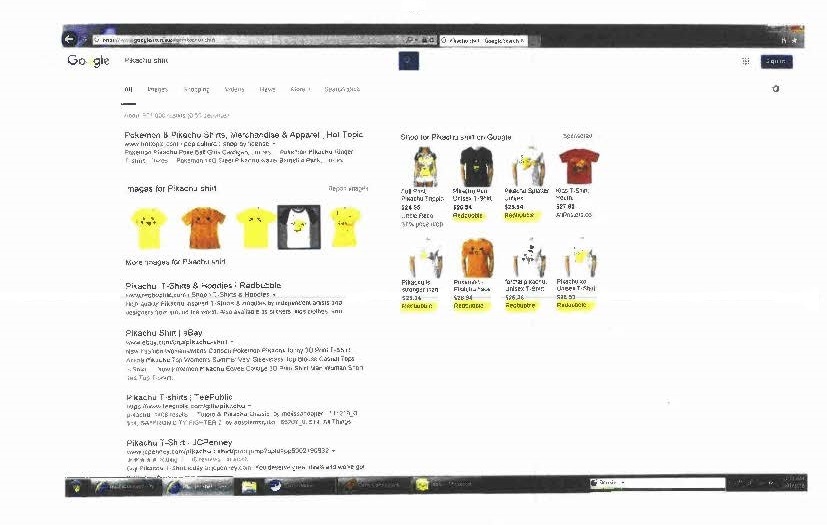

9 On 3 February 2016 searches were undertaken on the Google website on behalf of TPCi for 12 Pokémon characters. Screenshots were taken on that day of each of the searches which Redbubble agreed were accurate screenshots of the search results for each of the 12 searches that appeared as Annexure 1 to the statement of claim as the search results for the terms shown on the date and times shown on the screenshots. The screenshot for the Pikachu character at Annexure 1 to these reasons was, and may be taken, as a sufficient example of the other 11.

10 The screenshot in Annexure 1 to these reasons shows some highlighting which was made for the purposes of the proceedings, but otherwise reveals the results of the search done using Google for a Pikachu shirt. On the top left hand side is the Google URL for a Pikachu shirt. On the right hand side there are links sponsored by Redbubble for Pikachu shirts. On the left there are what the parties referred to as organic, that is non-sponsored links, including links to the Redbubble website, for Pikachu t-shirts. The layout of some of the other 11 screenshots for 3 February 2016 is different but each contains for present purposes information which is broadly to the same effect, namely, information of links sponsored by Redbubble to items connected with the Pikachu character as well as a link to the Redbubble website for products from an internet search by reference to the Pikachu character. The name Redbubble appears in both the organic search results and in the sponsored links. A person, including a consumer, who searched, for example, for a Pikachu shirt would obtain a search result that would show six Redbubble sponsored links containing Pikachu in the title, an image of a t-shirt bearing an image on the shirt and the name Redbubble under the image of the t-shirt.

11 Mr Rossi gave evidence that Google sponsored links were used by consumers searching for specific products such as a Pikachu t-shirt. Mr Rossi was the head of Paid Marketing for the Redbubble group of companies which includes the respondent. He was acquainted with how Google Shopping and the Google search engine work and has used them daily in the course of his work for Redbubble. Google Shopping is an internet search facility (or “engine”) offered by Google which allows users of the Google search engine, including potential retail consumers, to search for products online and to compare prices between products available on different electronic commerce platforms. Mr Rossi agreed that sponsored links typically contain the title of an artwork displayed on the Redbubble website, a brief description of the product, the price of the product and an image of the artwork depicted on the Redbubble website. A person searching for a particular product, such as a Pikachu t-shirt, can click on a sponsored link and will be taken directly to a page of the website containing the artwork featured on the Redbubble website. Redbubble pays for Google sponsored links to the Redbubble website and provided the information to Google in the Google sponsored links. A Redbubble sponsored link on the Google website might appear next to an advertisement for another online retailer like, in the case of another example, a retailer such as “Hot Topic” or a retailing department store with an online presence such as Target. Sponsored links are an important part of Redbubble’s marketing campaign, amongst other types of marketing, because, to use the words of Mr Rossi, they “direct traffic to products available via” Redbubble on its website.

12 Redbubble connects a data feed of products to the Google Merchant Center to enable products to show on Google Shopping as sponsored links. The Merchant Center is an online platform through which a user can create and manage shopping advertising campaigns. The connection between what Redbubble supplies and Google’s Merchant Center is through an application programming interface which does not involve any manual actions on behalf of Redbubble to update the product feed after connection. Content in certain fields on Redbubble’s product feed will automatically appear on the Google Merchant Center through the application programming interface. The fields of Redbubble’s product feed prescribed by Google in the application programming interface are:

(a) A product identification, being an individual numeric code ascribed to each product (for example, 00009012).

(b) The availability of the product, indicating whether the product is available for purchase.

(c) The brand name, being a recognisable name associated with the electronic commerce platform.

(d) The condition of the product, which in the case of all products available for purchase through the Redbubble website was “new”.

(e) A description of the product type, for example, whether the product was a unisex t-shirt together with the description provided by the artist selling the product on the Redbubble Website (for example, “watercolour painting of a fox”).

(f) The Google Product Category grouping which groups products into categories such as “apparel”.

(g) A Product Preview Image Link being a URL linking to the image of the artwork that the seller uploaded to the Redbubble website.

(h) A Product Page Link, being a URL linking to the webpage on the Redbubble website where a consumer can purchase the product from the artist.

(i) The price, being the retail price set by the artist.

(j) The Product Type, being the product types on which the artist has chosen to sell his or her artwork, for example, t-shirt, sticker or poster.

(k) The title of the artwork created by the artist.

(l) The Shipping Price.

(m) The Shipping Price Country.

13 Consumers for products which are available through the Redbubble website include consumers who might wish to purchase a t-shirt with an image of Pikachu or another Pokémon character. There was nothing on the website to indicate that Redbubble was not authorised by TPCi or other entity able to authorise others to sell products that might contain an image, or to make clear that Redbubble did not have a lawful association or authorisation of sponsorship. A person selecting a sponsored link would be directed to the Redbubble website, but a consumer directed to the Redbubble website would still not be informed of any lack of authorisation by TPCi, or by any other entity able to authorise Redbubble, in respect of any article on its website which had been downloaded by an artist containing a Pokémon character such as Pikachu. A consumer has no further need to browse the Redbubble website if he or she had selected an item on a sponsored link that appeared on the Google webpage of an item available through the Redbubble website that had been uploaded by an artist who was registered with Redbubble.

14 Redbubble controls the content of its sponsored links on Google. It allows artists registered with Redbubble to select the tags and descriptions which appear with the artwork they upload onto the Redbubble website as their own. The process leading to the offering of art for sale on the Redbubble website occurs through a computer program designed for Redbubble to operate in an automated fashion. Mr Victor Kovalev gave evidence in the proceeding of the operation of the Redbubble website. He was the Chief Technology Officer of Redbubble and described the activities leading to the sale by artists of articles with works uploaded by the artists onto the Redbubble website as taking place in a completely automated fashion from Redbubble’s perspective with no, or virtually no, human intervention on the part of Redbubble. Mr Kovalev explained that the signing up of artists, the indexing of artworks, the receipt of orders, the facilitation of transactions, the communications with suppliers relating to transactions, and all dispatch and billings were controlled by Redbubble’s software system being a suite of various “bespoke applications written by Redbubble staff and contractors” that were then executed on servers located in the United States. It is from that program which the information was fed to Google Shopping through the application programming interface as had been described by Mr Rossi.

15 Redbubble was aware, as previously mentioned, of the risk of potential infringement of copyright and other rights by artists registered through its website. Mr James Toy gave evidence of the measures adopted by Redbubble to discourage, prevent and penalise infringements and other contraventions of intellectual property and consumer rights. Mr Toy was an attorney and the assistant general counsel of the Redbubble group of companies employed by Redbubble Inc at the San Francisco office. His evidence included a description of the measures taken to prevent abuse and infringements of rights to which artists registered with Redbubble might not be entitled. Redbubble has an intellectual property policy (“the IP policy”) designed to discourage and prevent the infringement or contravention of intellectual property and consumer rights by those uploading material onto the Redbubble website. That includes a detailed user’s agreement, the existence of a content team to monitor activities on the Redbubble website and a process for owners of intellectual property rights to notify Redbubble of potential infringements to require that material be removed. The evidence was that Redbubble can, and has, identified certain keywords as negative keywords that become blocked for use by Redbubble’s registered artists. Redbubble could, in other words, have made a decision to block automatically artists from using trademarked words as tags. Mr Toy explained that doing so would be easier, cheaper and would require less effort than adopting what Redbubble considered to be the proactive measures described by Mr Toy, but the view was taken by Redbubble that blocking tags had an undesirable and disproportionate effect of preventing artists from using such words in legitimate, non-infringing ways and contexts. Redbubble, however, subsequently blocked the use of certain words, such as “Pikachu”, once it has become aware of the potential for infringement, although Mr Rossi, who was cross-examined about this, was not certain of the exact date when that had happened.

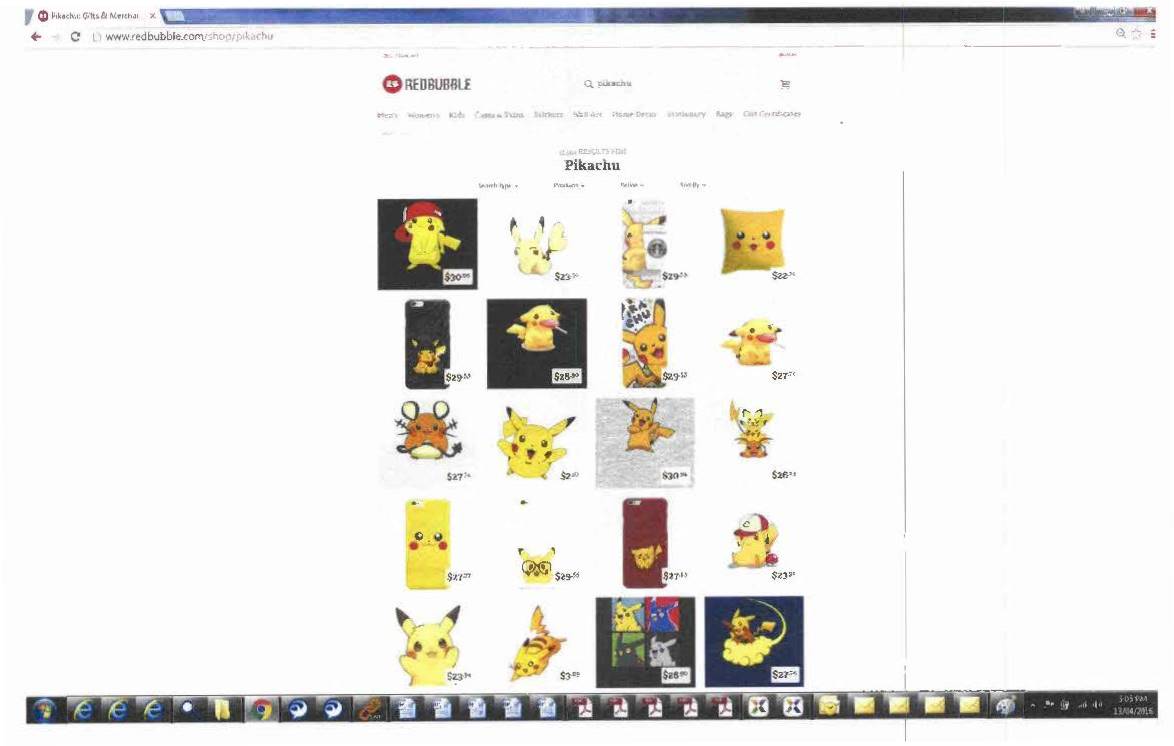

16 Pokémon complained also about the material found on the Redbubble website in addition to that found through the Google sponsored links. The Google searches, as mentioned above, also gave links to the Redbubble website other than as a sponsored link. Three experts were called to give evidence and they produced a joint report in which they summarised their opinions on propositions they had been asked to consider. The three experts were Mr Brent Coker, Mr Martin Tomitsch and Mr Anuj Luthra. Mr Luthra was the head of engineering at Redbubble and explained in the joint report that it was common for users to start searching for specific things on a search engine, like Google, and for websites matching their interest. A consumer using a Google search for a Pikachu t-shirt, or a Pikachu shirt, could thus access the Redbubble website via the organic (that is, the non-sponsored link) search links. A consumer selecting the Redbubble link would be taken to a Redbubble website of the kind shown in Annexure 2 to these reasons. On the top left hand corner of that example there appears the URL for the Redbubble shop page as it appeared on the screenshot on 13 April 2014 at 3.05pm. The body of the screenshot shows a series of characters in a shop format, which to varying degrees (except perhaps the mouse in the middle of the left hand side of the page) appear to be Pikachu related characters. The screenshot in Annexure 2 to these reasons is the beginning of the first page of the search result showing that 11,564 results were produced for the search “Pikachu” in connection with Redbubble. Comparable results were found for the other searches in respect of the other characters on which TPCi based its claim.

17 The results of the searches on the Redbubble website were to its shop page from which a consumer was able to select and purchase the product shown. The prices associated with the products available through Redbubble have some significance in TPCi’s claim against Redbubble because the prices are within the range of prices for like products sold by authorised licensees. The recommended retail price of an authorised Pokémon t-shirt is, for example, $25 and is therefore within the range of prices between $25 and $30 for comparable products which appeared on the Redbubble website from the search for Pikachu. A consumer for a product might possibly regard the fact that the price is within the range a consumer might expect to pay for a product from an authorised vendor as an indicator that the product was available for purchase from a dealer authorised by TPCi or by another entity able to authorise such dealings; a consumer would, at least, not be made suspicious about whether the product was being made available from an unauthorised dealer as might arguably occur if there were a marked disparity between the price on the website and the prices charged by authorised dealers.

18 The experts were largely in agreement that a consumer would generally use internal website search functions to find relevant pages within websites. Dr Coker opined that users who know what they are searching for would be more likely to use internal search box functions whilst users who had more open search criteria would be less likely to use the internal search box functions and more likely to use other navigation functions. Dr Tomitsch agreed that internal search functions were important and Mr Luthra conceded that most users would start from an external search engine like Google but considered that consumers using the Redbubble website would use the internal search engine to narrow their results. A consumer going onto the Redbubble website directly would find on the home page a search facility in which they could enter a name, such as Pikachu, to search for a t-shirt.

19 It was submitted on behalf of TPCi that consumers searching for Pokémon merchandise who are somewhat familiar with online shopping and search engines and with Pokémon characters, but who do not have a detailed knowledge of any client licensing arrangement, will be misled or deceived by the representations on the internet searches. In Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International (2000) 202 CLR 45 the High Court said that the effect of conduct or representations upon ordinary or reasonable members of a class must be considered where the issue is the effect of conduct on a class of persons. At [102]-[103] the Court said:

102 It is in these cases of representations to the public, of which the first appeal is one, that there enter the "ordinary" or "reasonable" members of the class of prospective purchasers. Although a class of consumers may be expected to include a wide range of persons, in isolating the "ordinary" or "reasonable" members of that class, there is an objective attribution of certain characteristics. Thus, in Puxu, Gibbs CJ determined that the legislation did not impose burdens which operated for the benefit of persons "who fail[ed] to take reasonable care of their own interests". In the same case, Mason J concluded that, whilst it was unlikely that an ordinary purchaser would notice the very slight differences in the appearance of the two items of furniture in question, nevertheless such a prospective purchaser reasonably could be expected to attempt to ascertain the brand name of the particular type of furniture on offer.

103 Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or from whom a relevant fact, circumstance or proposal was withheld, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted. In formulating this inquiry, the courts have had regard to what appears to be the outer limits of the purpose and scope of the statutory norm of conduct fixed by s 52. Thus, in Puxu, Gibbs CJ observed that conduct not intended to mislead or deceive and which was engaged in "honestly and reasonably" might nevertheless contravene s 52. Having regard to these "heavy burdens" which the statute created, his Honour concluded that, where the effect of conduct on a class of persons, such as consumers, was in issue, the section must be "regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class".

(Footnotes omitted).

In Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd (2016) 118 IPR 239 Beach J set out at [260]-[273] some non-contentious principles applicable to cases such as the present:

260 First, there is no meaningful difference between the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive”, “mislead or deceive” or “false or misleading”; see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] per Gordon J and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [40] per Allsop CJ.

261 Second, where the issue is the effect of conduct on a class of persons (rather than identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or particular conduct directed), the effect of the conduct or representations upon ordinary or reasonable members of that class must be considered (Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [102] and [103]). This hypothetical construct avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess effect or likely effect; it also avoids using those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness; it also avoids considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful. Third, the objective characteristics that one attributes to ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class may differ depending on the medium for communication being considered. There is scope for diversity of response both within the same medium and across different media.

262 Fourth, for the purposes of s 18, one must identify the relevant conduct and then consider whether that conduct, considered as a whole and in context, is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. Such conduct is not to be pigeon-holed into the framework or language of representation (cf the language of s 29).

263 Fifth, conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive if it has the tendency to lead into error (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). But conduct causing confusion or wonderment is not necessarily co-extensive with misleading or deceptive conduct (Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [8] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ). Mere confusion or wonderment will not establish misleading or deceptive conduct (Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 201 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ). In SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 169 ALR 1 at [51], the Full Court accepted that there may be evidence of initial confusion that did not result in any person seeking to commence negotiations, which would fall short of amounting to misleading or deceptive conduct.

264 Sixth, the question is whether there was a real but not remote chance or possibility that the relevant conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. To assess this one looks at the potential practical consequences and effect of the conduct.

265 Seventh, for the purposes of s 18, the words “likely to mislead or deceive” demonstrate that it is not necessary to show actual deception. Relatedly, it is not necessary to adduce evidence from persons to show that they were actually misled or deceived.

266 Eighth, there must be a sufficient nexus between the impugned conduct or apprehended conduct and the customer’s misconception or deception. As was said in SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 169 ALR 1 at [51] by French, Heerey and Lindgren JJ:

The characterisation of conduct as “misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive” involves a judgment of a notional cause and effect relationship between the conduct and the putative consumer’s state of mind. Implicit in that judgment is a selection process which can reject some causal connections, which, although theoretically open, are too tenuous or impose responsibility otherwise than in accordance with the policy of the legislation.

267 Subject to one qualification, the error or misconception must result from the respondent’s conduct and not from other circumstances for which the respondent was not responsible. But conduct that exploits or feeds into and thereby reinforces the pre-existing mistaken views of members of the relevant class may be misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

268 Ninth, conduct that is merely transitory or ephemeral where any likely misleading impression is likely to be readily or quickly dispelled or corrected does not constitute conduct that would infringe s 18 (Knight v Beyond Properties Pty Ltd (2007) 242 ALR 586 at [58] per French, Tamberlin and Rares JJ).

269 Tenth, and relatedly, it is one thing to say that the conduct must be more than transitory or ephemeral, but it is another thing to say that the conduct or its effect must endure up to some “point of sale”. There is no such requirement to establish a s 18 contravention. Relatedly, it is not necessary to show any actual or completed transaction entered into.

270 Eleventh, in determining whether a contravention of s 18 has occurred, the focus of the inquiry is on whether a not insignificant number within the class have been misled or deceived or are likely to have been misled or deceived by the respondent’s conduct. There has been some debate about the meaning of “a not insignificant number”. The Campomar formulation looks at the issue in a normative sense. The reactions of the hypothetical individual within the class are considered. The hypothetical individual is a reasonable or ordinary member of the class. Does satisfying the Campomar formulation satisfy the “not insignificant number” requirement? I am inclined to the view that if, applying the Campomar test, reasonable members of the class would be likely to be misled, then such a finding carries with it that a significant proportion of the class would be likely to be misled. But if I am wrong and that a finding of a “not insignificant number” of members of the class being likely to be misled is an additional requirement that needs to be satisfied, then I would make that finding in the present case. For a discussion of these issues, see Greenwood J’s analysis in Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 280 ALR 639 at [206] to [210] and National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2004) 61 IPR 420 at [70] and [71] per Jacobson and Bennett JJ.

271 Twelfth, in the case of a descriptive or generic word, for an applicant to make good an allegation of affiliation it may need to demonstrate that the word has acquired a secondary meaning and become distinctive of the applicant’s business. Whether a secondary meaning exists is a question of fact to be determined having regard to all the relevant contextual circumstances. It is also said that it may be difficult to establish that a descriptive name, as opposed to a concocted or invented name, has become distinctive of the applicant’s business.

272 Relatedly, however, there is no requirement under the Australian Consumer Law to show an exclusive reputation (Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (2007) 159 FCR 397 at [99] per Black CJ, Emmett and Middleton JJ). Indeed, query whether it is necessary to show a reputation at all (see Heerey J in Woodtree Pty Ltd v Zheng (2007) 164 FCR 369 at [34]). But perhaps it may be said that one need show only “[v]ery slight activities” and it can be established even without retail sales (Miki Shoko Co Ltd v Merv Brown Pty Ltd [1988] ATPR 40-858 at [49,278] per Lockhart J).

273 Thirteenth, while s 18 and s 29(1)(a), (g) and (h) have a broader scope of operation than the tort of passing off, when those sections are applied to facts asserted to give rise to a passing off then in practice a court may be guided by similar principles (see Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 227 per Stephen J).

The relevant date for assessing whether conduct amounts to misleading or deceptive conduct is the date the conduct commenced. See Flexopack [275]; Optical 88 Limited v Optical 88 Pty Limited (No. 2) & Ors (2010) 275 ALR 526, [333].

20 A significant reputation has been created in the marketplace for what might be described generally as the Pokémon brand. The Pokémon fictional universe, as mentioned above, comprises a group of more than 800 characters that players of Pokémon video games or trading card games can find, capture, train, trade, collect and use in battle against their rivals in the quest to become top Pokémon trainers. The Pokémon brand has become distinctive and is well known in its own right irrespective of who may be the legal owner: see Bodum v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 280 ALR 649 at [94], [279]; Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc [1990] RPC 341 at [406]. The reputation of the brand is associated with the name “Pokémon”, the names of the different Pokémon characters, and the distinctive images of each of those characters.

21 In 2016 Pokémon Go was released and that has also developed a substantial reputation with a distinctive Pokémon Go logo and distinctive logos for the three Pokémon Go teams, namely, Team Instinct, Team Mystic and Team Valour. Pokémon Go was designed as a game for smartphones developed by Niantic Inc in conjunction with The Pokémon Company. It is a reality game with the Pokémon characters in the players’ actual physical surroundings using GPS technology. Players of the game explore their real surroundings to find and catch Pokémon characters. The game is the same worldwide but the locations differ depending upon the location of the player. Pokémon Go was launched in Australia on 5 July 2016 and can be downloaded in Australia via the App Store and Google Play. Pokémon Go had surpassed 500 million downloads around the world by September 2016 and was said to hold the App Store record for the most downloads in the first week of a launch. The characters of Pokémon Go include Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Charmander, Charizard, Snorlax, Eevee, Flareon, Jolteon, Vaporeon, Gengar, Jigglypuff, Ponyta, Dragonite, Magikarp, Clefairy, Psyduck, Blastoise, Butterfree, Vulpix and Venusaur.

22 Pokémon has a substantial reputation in Australia and Redbubble admits that the name Pokémon is well-known in Australia. The first two Pokémon video games were, as mentioned above, released for the Nintendo Game Boy in Japan in 1996. They were first released in the United States in 1998 and subsequently, in the same year, in Australia under the names Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue. The Pokémon video games are based on a selection of Pokémon characters. More than 40 different Pokémon video games have been released in the 19 years since 1998 and many have been promoted and sold in Australia during that time. The video games sold in Australia during that period include the Pokémon Red version and the Pokémon Blue version (1998), Pokémon Yellow, Special Pikachu edition (1999), Pokémon Gold version and Pokémon Silver version (2000), Pokémon Crystal version (2001), Pokémon Diamond version and Pokémon Pearl version (2007), Pokémon X version and Pokémon Y version (2013), and Pokémon Omega Ruby and Pokémon Omega Sapphire (2014). More than 279 million video games have been sold worldwide as at February 2016 with new Pokémon video games being released approximately each year and core Pokémon video games introducing new characters being released every two to four years. Pokémon Sun and Pokémon Moon were released worldwide, including in Australia, in November 2016.

23 The Pokémon Trading Card Game has been sold in Australia by the applicant since at least 2005. The Pokémon Trading Card Game was distributed in Australia from 1999 by a third party under licence by Nintendo in America Inc. Between 2003 and 2005 it was distributed in Australia by Nintendo Australia but since 2005 it has been distributed in Australia by the applicant. More than 21.5 billion Pokémon Trading Card Game cards have been shipped to 74 countries in 11 languages as at March 2016. In oral evidence Ms Long said that new packs have been released four times a year since inception.

24 The animated television series featuring Pokémon characters in the adventures of a 10 year old boy named Ash with his best friend Pikachu have been broadcast in Australia since at least 2000. Home videos and DVDs of those television shows have been widely promoted and distributed since 2001. In cross-examination Ms Long said that there have been 20 seasons of the television series since 1998 and by 2010 there had been some 57,000 DVDs of the Pokémon television series, seasons 1-9. The series has been broadcast in Australia by free to air television and on the Cartoon Network. Season 1 aired on free to air television and on the Cartoon Network in 2000. The evidence of Ms Long was of broadcasts in Australia for most of the series and, relevantly, until the first letter of demand was sent to Redbubble by Pokémon in January 2011.

25 Pikachu featured in each of the seasons of the television series. Ms Long gave evidence of having watched most of the episodes through to the end of season 14 and that she had watched the first 50 seconds of episode 9 of season 1 at the request of counsel for Redbubble. In doing so she identified the first 50 seconds as being the opening credits which appeared in each episode of season 1 and the parties agreed that the characters which appeared in that opening sequence were the characters pleaded in the statement of claim as Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Charmander, Charizard, Blastoise, Butterfree and Venusaur. The parties also agreed that in the entirety of episode 9 the following additional Pokémon characters appeared, namely, Eevee, Flareon, Jolteon, Vaporeon, Magikarp, Psyduck and Vulpix.

26 Pokémon movies have also been sold in Australia in VHS and DVD formats via the applicant’s licensees. The characters featured in the movies have appeared in at least one movie or animated episode. Pikachu has appeared in all of them and the parties agreed that the characters which appeared in the first movie were Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Charizard, Vaporeon, Dragonite, Psyduck, Blastoise, Mewtwo, Vulpix, Togepi and Venusaur.

27 An important part of the commercial activities of the applicant is to licence the sale of merchandise connected with the Pokémon brand. The precise number, identity and prices are not important for present purposes, but it is clear from the evidence that there were significant licensed sales of products of Pokémon branded merchandise in respect of most of the pleaded Pokémon characters up to the date in January 2011 when the applicant wrote a letter of demand to Redbubble. The sales by reference to characters over the relevant period were set out in a lengthy exhibit to the affidavit of Ms Long and helpfully summarised by Counsel for TPCi in closing address. The Pikachu character featured on many Pokémon branded merchandise including plush toys, t-shirts and books. The Sylveon character was not relevant because that character was not released until 2013, although the evidence exhibited through Ms Long included sales of toys and figures in relation to that character after its release.

28 Conduct is misleading or deceptive “if it has the tendency to lead into error”: see Flexopack at [263]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2015) CLR 640 at [39]. The Redbubble website and the internet advertisements sponsored by Redbubble on Google contained representations contrary to ss 18(1), 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law that the products available through those websites were supplied, licensed, associated, sponsored, approved or authorised by TPCi or such other entity able to entitle Redbubble to make such representations. A consumer searching for one of the Pokémon characters in suit on the internet search engine provided by Google would be taken to pages of the kind annexed to these reasons. What appeared in the sponsored links differed somewhat from what appeared on the Redbubble website but in each case a consumer would see representations that artworks on products available through the Redbubble website were supplied, licensed, associated, sponsored, approved or authorised by TPCi or by another entity able lawfully to authorise Pokémon branded merchandise. The name Redbubble appeared in both the sponsored links and the Redbubble links. The words “sponsored” appeared in the case of the sponsored links above the item available for purchase, such as the red t-shirt in the top row in the Annexure 1 to these reasons. Each of the sponsored links has a price and the name of the Pokémon character used for the search such as, in the case of the example, the name “Pikachu”. The sponsored link search result for Pikachu, for example, had a white t-shirt with the word “Pikachu” in the search result together with a price and also the name “Redbubble”. A consumer obtaining that search result would be told that selecting a sponsored result would take the consumer to the sponsor, which in this case was Redbubble. A consumer would see six highlighted Redbubble sponsored links in the example in Annexure 1 containing the word “Pikachu” in the title, t-shirts bearing an image of Pikachu, and the name “Redbubble” under the image. The evidence of Mr Rossi was that Google sponsored links are used by customers searching for a specific product and that Google sponsored links are attractive to customers intending to make a purchase quickly without the effort of browsing through the Redbubble website appearing in the non-sponsored search results in Annexure 1. A potential customer taken to the Redbubble webpage as a result of clicking the sponsored link would not be told anything to suggest that Redbubble was not an authorised online retailer of Pokémon products such as the Pikachu t-shirt depicted and described in the sponsored link. The consumer arriving at the Redbubble linked page could add the item to a purchase cart and select the payment option to purchase the product directly from the Redbubble website. There was nothing on the Redbubble website to inform the consumer that there was no connection, authorised or otherwise, between Redbubble on the one hand and TPCi (or any other entity authorised to exploit Pokémon products) on the other.

29 The effect of the representations is to be considered by reference to “ordinary or reasonable members of that class” of persons to whom the representations are directed: see Flexopack at [261]; see also Campomar at [102] and [103]. In this case that class is those persons seeking to purchase products as retail customers. It was submitted for Redbubble that the only representation on the website was that articles, such as a t-shirt, were available for sale. This was submitted in part to follow from the fact “that the internet [was] awash with Pokémon characters” on other sites. Amongst those was Bulbapedia, other fan sites, Etsy and Ebay. It may be assumed that some of the relevant class of persons will have such knowledge of the Pokémon world, or the availability of Pokémon products, that the effect upon them of what appeared from the search would not have been to be misled or deceived, but, as Beach J observed at [261] in Flexopack, the “hypothetical construct avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess effect or likely effect” as well as the habitually cautious and exceptionally careless. The representations may not be made in all of the results from the internet search but the ordinary or reasonable retail consumer for Pikachu related products would have the repeated representation in a significant number of search results that what was offered through Redbubble was supplied, licensed, associated, sponsored, approved or authorised by TPCi when that was not the case. It is not an answer to a claim of contravention that the conduct may not have misled or deceived up to the point of sale: ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd at [50]; Veda Advantage Ltd v Malouf Group Enterprises Pty Ltd (2016) 241 FCR 161 at [254]; Flexopack at [269].

30 A consumer using the Redbubble internal search function would find similar representations. The experts agreed that search engines like Google are commonly used by consumers and are an important means of finding relevant pages they are searching for on websites. Mr Luthra, as mentioned, explained in the joint expert report that it was common for users to start by searching for specific things on a search engine like Google to find a website matching their interest. The Redbubble website in Annexure 1 could be accessed by choosing the organic search link on the left side of the annexure which would generally take the consumer to a Redbubble shop page. An example of the shop page is at Annexure 2 of these reasons showing 11,564 results for the search on the Redbubble website. The particulars to paragraph 43 of the statement of claim set out the relevant results for different searches of the Pokémon characters in suit. 11,564 results were identified in the case of the search for Pikachu of which some were of the kind in the screenshot in Annexure 2. The Redbubble logo appeared on its website with nothing to suggest that Redbubble was not authorised by TPCi or by any other entity able to authorise Redbubble. The price for the item was within the same range as a customer could expect to pay for the product from an authorised merchandiser consistently with the evidence of the prices sold for products by authorised Pokémon licensees. Some of the 11,564 results would not contain the representations of authorisation, connection or sanction by TPCi or other entity with the right to licence authorised products but many would, such as all those appearing in Annexure 2 except the mouse on the left on the third line.

31 A consumer wishing to locate a product directly on the Redbubble website would, according to the experts, undertake a search from the search function on Redbubble’s homepage. Dr Coker explained that a user searching for something in particular, such as a truck design, would be more likely to use the internal search box function than to browse on Google more generally. Dr Tomitsch agreed that the internal search function was important and Mr Luthra considered that most users would start at an external search function but considered that consumers using the Redbubble website would use the internal search engine to narrow their results. A person searching on the Redbubble website would thus be able to enter a name, such as “Pikachu”, and search for a t-shirt by reference to that name. Such a consumer would be directed to the relevant page enabling the purchase of the item because of the tags and titles which Redbubble allows its registered artists to use to describe their products for sale in connection with the fulfillers.

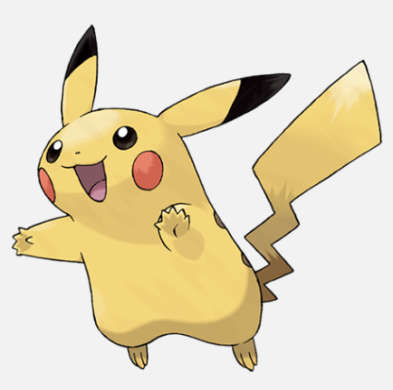

32 TPCi’s copyright case in the proceedings relied upon the artistic work depicted as Pikachu in paragraph 11(a) of the Statement of Claim, namely:

TPCi claimed to be the owner of the copyright in the Pikachu work, that copyright subsisted in it pursuant to s 32 of the Copyright Act as extended by the Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (“the International Protection Regulations”), and that the work was an original artistic work pursuant to s 10 of the Copyright Act. Redbubble admitted that the Pikachu work was an artistic work pursuant to s 10 of the Copyright Act but did not admit that TPCi was the owner of any copyright in the Pikachu work or that it was original or that copyright subsists in it pursuant to s 32 of the Copyright Act as extended by the International Protection Regulations.

33 TPCi claimed to have copyright in the Pikachu work as a published artistic work. Section 32(2) of the Copyright Act provides in the case of published artistic works:

(2) Subject to this Act, where an original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work has been published:

(a) copyright subsists in the work; or

(b) if copyright in the work subsisted immediately before its first publication--copyright continues to subsist in the work;

if, but only if:

(c) the first publication of the work took place in Australia;

(d) the author of the work was a qualified person at the time when the work was first published; or

(e) the author died before that time but was a qualified person immediately before his or her death.

TPCi’s claim of subsistence of copyright in the Pikachu work requires that the Pikachu work be original, that its first publication took place in Australia and that the author of the work was a “qualified person” within the meaning of s 32(2) as defined by s 32(4).

34 The requirement that the Pikachu work be an original artistic work within the meaning of s 32(1) of the Copyright Act will not be satisfied by a mere mechanical reproduction or a slavish copy of an earlier copyright work. The revision of an earlier original work, however, will attract independent copyright protection provided that the latter work has the requisite degree of originality over and above the earlier work. What is required to establish originality is that the subsequent work had some independent intellectual effort, although the work may have no literary merit, novelty or inventiveness: see IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458, 474, [33]; Interlego v Croner Trading (1992) 111 ALR 577, 608-609. In Digga Australia Pty Ltd v Norm Engineering Pty Ltd (2008) 166 FCR 268 Lindgren J said at [52]:

52. The following principles of law were, it appeared, not controversial on the appeal:

• The necessary skill and labour to confer originality for copyright purposes is not necessarily excluded where there is change from one medium to another, for example, a drawing of a three-dimensional object, such as a prototype: see L B (Plastics) Ltd v Swish Products Ltd [1979] RPC 551 at 568-569; Interlego AG v Tyco Industries Inc [1989] AC 217 (Interlego) at 263; Swarbrick v Burge (2004) 208 ALR 19 at [138] – [140]; Garnett K, Gillian D and Garbottle G, Copinger and Skone James on Copyright (15th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, London, 2005) (Copinger) vol 1 at [3–135].

• The owner of copyright in an original artistic work does not, simply by mechanically reproducing it, create a further original artistic work attracting copyright protection: The Reject Shop Plc v Robert Manners [1995] FSR 870 (The Reject Shop). If the position were otherwise, the way would be open for the copyright owner to “re-start” the period of copyright protection, and, indeed, to do so many times: see Interlego at 255-256, 263, 268.

• Where a copyright owner makes a mere a mere mechanical reproduction of the copyright work, the copy will not itself be an original work attracting copyright protection, but it may be seen to enjoy vicariously the benefits of the copyright protection attached to the earlier work, although only for the duration of that copyright, and only, of course, if remedies are still available in respect of that copyright: Copinger vol 1 at [3-134]; and see Interlego at 268; Biotrading & Financing OY v Biohit Ltd [1996] FSR 393 at 395-396; Biotrading & Financing OY v Biohit Ltd [1998] FSR 109 at 116-117.

• Whether successive revisions of an earlier original work will attract independent copyright protection depends on whether they have the requisite quality of originality over and above that of the earlier original work or earlier original revision: Interlego at 263; Interlego AG V Croner Trading Pty Ltd (1992) 39 FCR 348 at 378-379 per Gummow J; C&H Engineering v F Klucznik & Son Ltd (1992) 26 IPR 133 at 139.

• Where the author of a drawing makes preliminary drawings before producing the final version, the final version is not denied originality merely because it was preceded by the preliminary drawings: L A Gear Inc v Hi-Tec Sports Plc [1992] FSR 121 at 136; Biotrading & Financing OY v Biohit Ltd [1998] FSR 109 at 116-117; Copinger vol 1 at [3-133]-[3-134].

Drawings derived from earlier drawings may still be seen as distinct original artistic works sufficient to attract independent copyright, with the test for determining whether one drawing based on another attracted copyright being a visual one: see Interlego at 609. The question for the Court was stated in Interlego at 609 to be “whether a latter drawing [was] merely a copy of the earlier, or [was] a new artistic work”. In that case the Court relied upon evidence that the two works in question were “visually distinctive”: Interlego at 610. In Metricon Homes Pty Ltd v Barrett Property Group Pty Ltd (2008) 248 ALR 364 it was said at [42] that a plan would be an original artistic work in the statutory sense “if it [was] recognisably the author’s own work as opposed to a copy of another’s work or a trivial variation of another’s work”.

35 TPCi claimed copyright in the Pikachu work described as “PB&W7 - Pikachu (50/149)” in the certificate of registration issued in accordance with Title 17 of the United States Code. Evidence of originality in that work was given by Mr Monahan who was the lawyer retained by TPCi and was responsible for filing hundreds of copyright registrations in the USA for Pokémon cards each year since at least 2010, including those described as “PB&W7 - Pikachu (50/149)” in the certificate of registration. He swore an affidavit stating that he remembered the card with the image of the Pikachu work that was part of the Black and White 7 series that he filed for copyright registration. The process of registration in the United States undertaken by Mr Monahan involved him submitting an electronic registration with the image of the work. The Pikachu character was a longstanding character that had featured on a number of the Pokémon cards that he had registered over the years. He acknowledged that there were several hundred characters in the new series and that he could not recite or list them all but said that he could recognise their names when they were given to him. His evidence, however, was of being confident that the Pikachu work was not a derivative work, notwithstanding that there had been earlier depictions of Pikachu.

36 Mr Monahan was questioned closely in cross-examination about his knowledge of the creation of the works he had registered, including the Pikachu work, and his evidence can be accepted as establishing the requisite degree of originality in the Pikachu work relied upon for the copyright claim. He was asked about the investigations he undertook personally in relation to the 149 cards of the 7th series of the Black and White series to determine whether each was a derivative work or whether there was any pre-existing work and said in oral evidence in cross-examination:

After registering so many of these and in somewhat exhaustive consultation with my client, I’ve come to understand, if not to know, that the playing cards are not derivative - they are not re-hashed from the audio-visual works: that artwork is created and stands alone. So they are not compilations of other works; they are not created from animation sells; and so they are not derivative or compilation works …

He repeated his explanation that the basis of his answer was having had “extensive consultations with” his client from which he had come to “understand, if not to know that the playing card artwork [was] created without derivation or consultation to the animation work or other IP assets that exist within TPCi’s portfolio”. He conceded in cross-examination that he had not stood over the shoulder of any creator and, therefore, that he did not have direct eyewitness, or other direct, knowledge beyond that gained from “detailed consultation with the client” but that “with respect to each series of the cards, [he had] consult[ed] with the client to determine which - for instance, which Japanese card they derive[d] from, or [… where] the artwork comes from”. His specific and direct evidence was that of consulting with the client to determine that the works were made by the Japanese company and were made as the Japanese card, although, as mentioned, he did not fly personally to Japan and had not been witness to the creation process. It had been his specific professional responsibility to obtain and secure registrations in accordance with lawful entitlements and requirements. He was confident in that context of his conclusion that the Pikachu work was not a copy based upon an animation cell because of his experience over many years of consulting with the client as his professional obligations and legal duties. In specific response in cross-examination about being confident in giving evidence that the pose of Pikachu was not derivative of any other pose already published, Mr Monahan said that every investigation he had done about the card making process enabled him to say that the cards were generated on their own and were not derivative of the animation, “common poses notwithstanding”.

37 Subsistence of copyright requires also that the first publication of the work took place in Australia, but the effect of Regulation 4(1) of the International Protection Regulations is that an artistic work first published in Japan by a Japanese citizen is given the same protection under the Copyright Act as if it had first been published in Australia by an Australian resident. Regulations 4(1) and (4) provide:

Protection--Berne Convention countries, UCC countries, USA, Rome Convention countries, WPPT countries and WTO countries (Act s 184)

Work, and subject-matter other than a work, made or first published in a foreign country

(1) Subject to these Regulations, a provision of the Act that applies in relation to a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or edition first published, or a sound recording or cinematograph film made or first published, in Australia (an Australian work or subject-matter) applies in relation to a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or edition first published, or a sound recording or cinematograph film made or first published, in a Berne Convention country, a Rome Convention country, a UCC country, a WCT country, a WPPT country or a WTO country (a foreign work or subject-matter ):

(a) in the same way as the provision applies, under the Act, in relation to an Australian work or subject-matter; and

(b) as if the foreign work or subject-matter were made or first published in Australia.

[…]

(4) Subject to these Regulations, a provision of the Act relating to a work or subject-matter other than a work that applies in relation to a person who, at a material time, is resident in Australia (an Australian resident ) applies in relation to a person who, at a material time, is resident in a Berne Convention country, a Rome Convention country, a UCC country, a WCT country, a WPPT country or a WTO country (a foreign resident ):

(a) in the same way as the provision applies, under the Act, in relation to an Australian resident; and

(b) as if the foreign resident were an Australian resident.

[…].

The Pikachu work was established to have been first published in Japan, and Redbubble accepted that the author was Japanese and, therefore, that the author was a qualified person within the meaning of s 32(2), as defined by s 32(4) of the Copyright Act, and as extended by International Protection Regulations.

38 TPCi would, in any event, if it were necessary to decide the issue, have had the benefit of the presumption under s 126A of the Copyright Act by virtue of the certificate tendered by Mr Monahan. Section 126A(3) presumes the year and place of first publication of a work to be that stated in a certificate issued in a qualifying country unless the contrary is established. Section 126A(3) and (4) provide:

Foreign certificates

(3) If a certificate or other document issued in a qualifying country in accordance with a law of that country states the year and place of the first publication, or of the making, of the work or other subject matter, then that year and place are presumed to be as stated in the certificate or document, unless the contrary is established.

(4) For the purposes of this section, a document purporting to be a certificate or document referred to in subsection (3) is, unless the contrary intention is established, taken to be such a certificate or document.

A certificate of registration was relied upon in these proceedings which stated the first place of publication of the Pikachu work to have been Japan and the date of first publication to have been 15 April 2012.

39 TPCi’s claim of ownership relied upon s 126B(3) of the Copyright Act which provides that a person is presumed to have been the owner of the copyright at the time stated in a certificate or other document issued in a qualifying country in accordance with a law of that country. In that context TPCi relied upon the certificate of registration issued under the seal of the copyright office in accordance with Title 17 of the United States Code, attesting that registration had been made for the work described as “PB&W 7-Pikachu (50/149).

40 Section 126B(3) creates a presumption of ownership where a certificate issued in a qualifying country “states that a person was the owner of copyright in the work”. Section 126B(4) provides that a document “purporting to be a certificate or document referred to” in the previous subsection is taken to be such certificate or document unless the contrary intention is established. Sections 126B(3) and (4) provide:

Foreign certificates

(3) If a certificate or other document issued in a qualifying country in accordance with a law of that country states that a person was the owner of copyright in the work or other subject matter at a particular time, then the person is presumed to have been the owner of the copyright at the time, unless the contrary is established.

(4) For the purposes of this section, a document purporting to be a certificate or document referred to in subsection (3) is, unless the contrary intention is established, taken to be such a certificate or document.

The certificate relied upon by TPCi did not in terms state that TPCi was the “owner” of the copyright work. Indeed, Mr Monahan gave evidence, that a certificate of copyright registration in the United States describing a copyright claimant as an owner cannot be obtained. Mr Monahan was an experienced attorney and was the principal, as sole practitioner, of a legal practice conducted under the name Astrolabe LLC. Mr Monahan gave evidence of the registration process for copyright works in the United States as essentially a depositing arrangement where people who are the owners of copyright, or perhaps more precisely, where people who claim to be the owners of copyright, are able, if they wish, to take advantage of a registration process subject to penalties for perjury if making false claims. Mr Monahan explained that the system of registration of ownership in the United States does not confer ownership by registration but that it provided an evidentiary function for those who claimed ownership and, significantly, that claims of ownership were subject to a penalty for perjury if a false claim was made.

41 The permissive system for registration in the United States permits only the owner to be registered. Section 408(a) and (b) of the United States provisions provide:

s 408 Copyright registration in general

(a) REGISTRATION PERMISSIVE. – At any time during the subsistence of the first term of copyright in any published or unpublished work in which the copyright was secured before January 1, 1978, and during the subsistence of any copyright secured on or after that date, the owner of copyright or of any exclusive right in the work may obtain registration of the copyright claim by delivering to the Copyright Office the deposit specified by this section, together with the application and fee specified by sections 409 and 708. Such registration is not a condition of copyright protection.

(b) DEPOSIT FOR COPYRIGHT REGISTRATION – Except as provided by subsection (c), the material deposited for registration shall include –

(1) in the case of an unpublished work, one complete copy or phonorecord;

(2) in the case of a published work, two complete copies or phonorecords of the best edition;

(3) in the case of a work first published outside the United States, one complete copy or phonorecord as so published;

(4) in the case of a contribution to a collective work, one complete copy or phonorecord of the best edition of the collective work.

A system of registration which does not confer ownership is consistent with the general rules concerning the ownership of copyright in works. The general rule of ownership of copyright in a work does not depend upon registration but upon identification of the author.

42 Section 126B was inserted into the Copyright Act by the Copyright Amendment (Parallel Importation) Act 2003 (Cth) with effect from 13 May 2003. The Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum described the mischief to which it was directed as being to address the “concern about the difficulty and/or expense of proving copyright subsistence and ownership in infringement cases in Australia where evidence to the contrary is not provided”. The section was amended in 2006 by altering the effect of the provision from being prima facie evidence of the matters shown on the face of the certificate with a “stronger presumption that the statements contained on the labels, marks, certificates or other chain of ownership documents are presumed to be stated ‘unless the contrary is established’”: see Explanatory Memorandum to the Copyright Amendment Bill 2006 (Cth), paragraph 2.2. It was submitted for Redbubble, however, that the presumption created by s 126B did not, and could not, apply to a certificate of registration of the kind provided in the United States and relied upon by TPCi, because the certificate did not state in express words that the person claiming to be the owner was the owner of copyright in the works. A submission to that effect found favour in Dallas Buyers Club v iiNet (2015) 245 FCR 129 where Perram J concluded that copyright in a film had originally been owned by Dallas Buyers Club LLC and, in reaching that conclusion, disregarded the certificate produced which had also showed that it was the owner of copyright on 1 November 2013. At [35]-[36] his Honour said:

35 I infer from this evidence that the contractual arrangements which were entered into in order to bring Dallas Buyers Club into existence were made by Dallas Buyers Club LLC. From this I conclude that it was the original copyright owner. It might be noted that the only other possible candidate for the role of producer would have to be Voltage. The ISPs did not submit that the copyright was originally vested in any other entity apart from these two companies. In any event, I conclude that the copyright in the film was originally owned by Dallas Buyers Club LLC.

36 In reaching that conclusion, however, I disregard the certificate produced by Mr Wickstrom which, according to him, showed that Dallas Buyers Club LLC was the copyright owner on 1 November 2013. Although that is factually correct, the certificate does not advance this case. It is not a certificate which ‘states that a person was the owner of copyright in the work’ within the meaning of s 126B(3) of the Copyright Act so the certificate does not have prima facie effect under that provision. All that the certificate says is that Dallas Buyers Club LLC claims to be the copyright owner. This is not sufficient but, given my conclusions, neither is it relevant.

His Honour’s observations about the certificate were, strictly speaking, obiter dicta and were not necessary for the determination of the issues which had arisen before him in interlocutory proceedings. The view expressed by his Honour at [36] that the certificate was not one within the meaning of s 126B(3) of the Copyright Act because the certificate was not one which “states that person was the owner of the copyright of the work”, however, was given in a reasoned decision and should be followed unless persuaded that his Honour’s decision was clearly wrong or plainly wrong: Undershaft (No 1) Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2009) 175 FCR 150, [68]-[88]; Rawson Finances Pty Ltd v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (2010) 189 FCR 189, [56]; see also Prebble v Commissioner of Taxation (2003) 131 FCR 130. In that context it is relevant that his Honour did not appear to have the evidence about the system of registration in the United States that was in evidence in this proceeding, and that the issue before his Honour may not have been as fully argued as it was in this proceeding.

43 Whether or not a certificate or other document issued by a qualifying country “states that a person was the owner of copyright in the work” is to be determined, as his Honour in Dallas Buyers Club considered, by construing the certificate issued by the qualifying country and relied upon in the proceeding. That is consistent with the effect of s 126B(4). Whether a certificate “states that a person is the owner of copyright” in a work may appear from the certificate other than by a statement formulated by the words that a person was the owner. The purpose of s 126B(3) is to provide a mechanism to establish rebuttable evidence of ownership by production of a certificate from a qualifying country identifying the owner. The owner in the case of certificates issued in the United States is the person who claims to be the owner and, therefore, a certificate may be taken to state who is the owner by identifying the person who claims to be the owner. Ownership may be stated to be, in other words, as was the case of the certificate relied upon by TPCi in this case, by a certificate identifying the person making the claim of ownership. TPCi is clearly stated in the certificate as the claimant of ownership of the copyright work. The certificate attests to the registration of TPCi as the person claiming ownership in a system of registration entitling persons claiming ownership to be registered as claimants of ownership and who do so subject to prosecution and penalty for perjury. Section 126B(3) applies to certificates or other documents issued by a “qualifying country”, which is defined in s 10 in terms to include the United States of America. It would seem curious, therefore, that the legislature would intend to effect the purpose described in the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the enactment of s 126B(3) in terms which would exclude its application in the United States of America. That, however, (as was accepted by senior counsel for Redbubble), would be the consequence of the argument that the certificate relied upon by TPCi was not one which “state[d] that a person was the owner of copyright in the work” as was accepted by his Honour in Dallas Buyers Club. In those circumstances, I am satisfied that the certificate relied upon comes within the meaning of s 126B(3) of the Copyright Act and that I should not follow the obiter view to the contrary at [36] in Dallas Buyers Club as being clearly wrong or plainly wrong.

44 A consequence of that conclusion is that it is unnecessary to deal with some of the facts explored by senior counsel for Redbubble about authorship of the Pikachu work. TPCi did not establish ownership by evidence of authorship of the Pikachu work although there was some evidence about how the Pikachu work came to be made. It may be assumed that an individual employed by a company related to, but not being, TPCi was the author of the work, and that TPCi obtained an assignment of, or became entitled to, the copyright which was claimed in the certificate issued in accordance with Title 17 of the United States Code. None of the evidence on those matters, however, established anything to the contrary of the claim by TPCi which was made in the certificate of being the owner of the copyright in the Pikachu work. The presumptions effected by s 126B(3) of the Copyright Act may thus be relied upon to establish ownership by TPCi with effect from the date in the certificate which was stated to be 26 October 2012.