FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Manado (on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group) v State of Western Australia [2017] FCA 1367

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 1 February 2018, or such further time as allowed by the Court, the parties file and serve any application for the determination of any of the matters referred to in [628], [645], [656], [670] and [734] which are not agreed between the parties.

2. Subject to the resolution of the matters referred to in [1], on a date to be fixed, the parties file and serve proposed orders and a draft determination reflecting these reasons for judgment.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NORTH J:

1 Before the Court are three applications for a determination of native title in the mid-Dampier Peninsula in Western Australia.

2 Application WAD 359 of 2013, Ernest Damien Manado and others on behalf of the Bindunbur Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia and others, the Bindunbur application, was filed on 20 September 2013. It was a combination of that application with two later applications, WAD 425 of 2013 and WAD 94 of 2014.

3 Application WAD 357 of 2013, Rita Augustine and others on behalf of the Jabirr Jabirr Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia and others, the Jabirr Jabirr application, was filed on 23 September 2013. It took the place of an earlier application, WAD 124 of 2010, which was filed on 20 May 2010 by the same people over the same land.

4 Application WAD 374 of 2013, JR (Deceased) and others on behalf of the Goolarabooloo Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia and others, the Goolarabooloo application, was filed on 4 October 2013.

5 The Bindunbur, Jabirr Jabirr and Goolarabooloo applications were heard together. The Bindunbur applicants were referred to as the first applicant, the Jabirr Jabirr applicants as the third applicant, and the Goolarabooloo applicants as the fourth applicant.

6 The respondents which took an active part in the combined proceeding were the State of Western Australia, the first respondent, the Commonwealth, the second respondent, and the Shire of Broome which was referred to as such.

2. THE PROPOSED NATIVE TITLE CLAIM HOLDING GROUPS

7 The members of the proposed Bindunbur Native Title Holding Group comprise the descendants, including by adoption, of 45 apical ancestors who were members of a society which comprised or included people who identified themselves respectively by one or more of the labels Jabirr Jabirr, Ngumbarl (Nyombal), Nyul Nyul or Nimanbur. The apical ancestors relied on are:

1. Murrjal

2. Dorothy Kelly

3. Liddy Kenagai

4. Liddy Skinner

5. Bornal

6. William Wallai & Mary Nelagumia

7. Senanus

8. Frank Walmandu & granddaughter Sophie McKenzie

9. Jimmy Bulongi (aka Frank Dinghi)

10. Nabi

11. Appolonia

12. Dorothy

13. Agnes Imbarr

14. Deborah & Jacky

15. Ethel Jacky

16. Alice Daradara

17. Matilda

18. Louisa

19. Milare & Kelergado

20. Flora

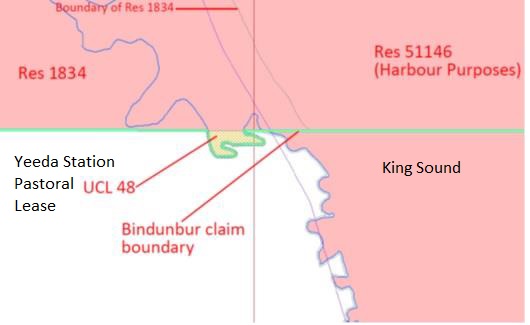

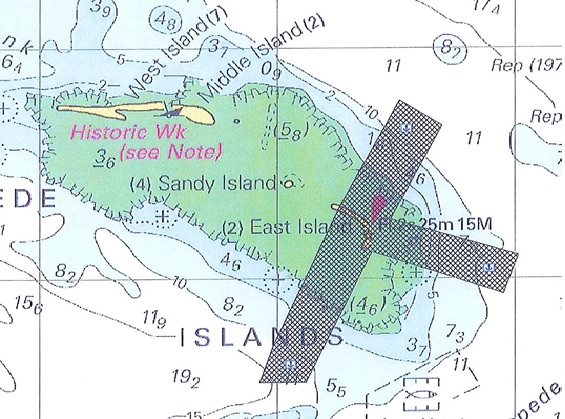

21. Madeline

22. Malambor (Tjanganbor)

23. Walmandjin & son Ringarr Augustine

24. Alice Kotonel Wright

25. Bismarck

26. Kokanbor and Felix Nortingbor and Victor

27. Abraham Kongudu

28. Narcis Yumit

29. Peter Biyarr

30. Anselem and Patrick (brothers)

31. Patrick Mouda

32. Kandy

33. Mary and Din Din

34. Jidnyambala and Bobby Ah Choo

35. Fred/Friday Walmadayin.

8 The members of the proposed Jabirr Jabirr Native Title Holding Group comprise the descendants of 24 apical ancestors who identified themselves as Jabirr Jabirr and/or Ngumbarl. The apical ancestors are:

1. Gardarlagan

2. Frank Dinghi, aka Jimmy Bulingi

3. Appolonia, mother of Gerard, Theresa, Josephine and Ester

4. Nabi

5. Dorothy, sister of Senanus

6. Marry Nelagumia

7. Appolonia, sister of Mary Nelagumia

8. Wallai William

9. Agnes Imbarr

10. Fred/ Friday Walmadang

11. Murjal, sister of Senanus

12. Sophie, mother of Kay McKenzie and others

13. Frank Walmandu, brother of Senanus

14. Flora, sister of Matilda

15. Louisa, aka Djauradjaura, sister of Matilda

16. Madeline, sister of Matilda

17. Matilda, mother of Josephine Torres and others

18. Bornal

19. Liddy

20. Dorothy Kelly

21. Walamandjjn

22. Alice Darada

23. Jacky and Deborah

9 The members of the proposed Goolarabooloo Native Title Holding Group are described in Schedule 2 to the determination proposed by the Goolarabooloo as follows:

[T]hose living Aboriginal persons who

1. (a) are the descendants, including by adoption, of Paddy Roe and Mary Pikalili; or

(b) are the descendants, including by adoption, of one or more of the apical ancestors of the other traditional rights holders referred to in paragraph 37 of the Fourth Applicant's SFIC [Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions]; or

(c) are connected to the Determination Area through rai (rayi), or who are descended from a person connected to the Determination Area through rai (rayi)

AND who are recognised by other native title holders as having realised their rights through knowledge, association and familiarity with the Determination Area gained in accordance with the traditional laws and customs of the native title holders; or

2. hold mythical or ritual knowledge and experience of the Determination Area, and who are responsible for places, areas and things of mythological or ritual significance in the Determination Area and who are recognised by other native title holders under their relevant traditional laws and customs as having native title in the Determination Area.

10 Paragraph 37 of the Goolarabooloo’s Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions (SFIC) referred to above provides:

The Fourth Applicant contends that some of the native title rights and interests referred to in paragraph 36 may be jointly held with other members of the regional society who are connected to the land and waters of the Goolarabooloo claim area by the traditional laws and customs of the region (“other traditional rights holders”). The other traditional rights holders are understood to

(a) predominantly identify themselves as Jabirr Jabirr or Ngumbarl persons.

(b) include members of the WAD 357 / 2013 claim group and the WAD 359 / 2013 claim group.

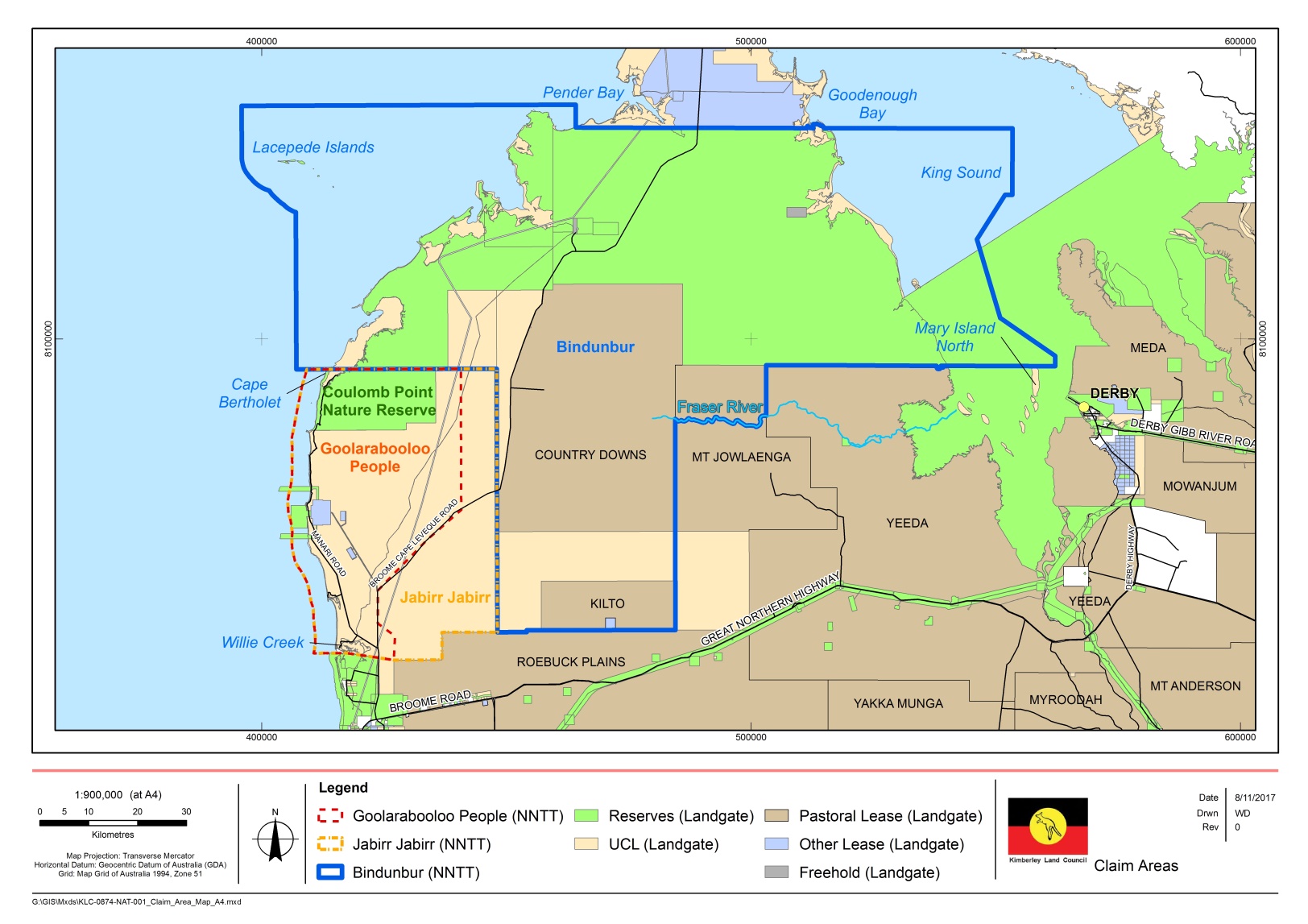

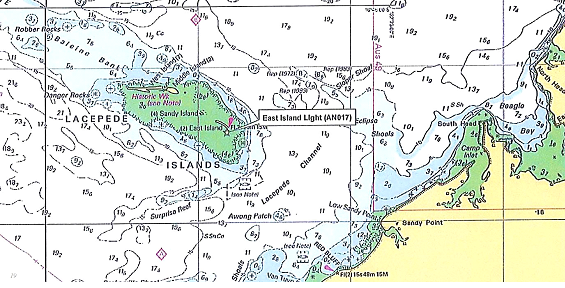

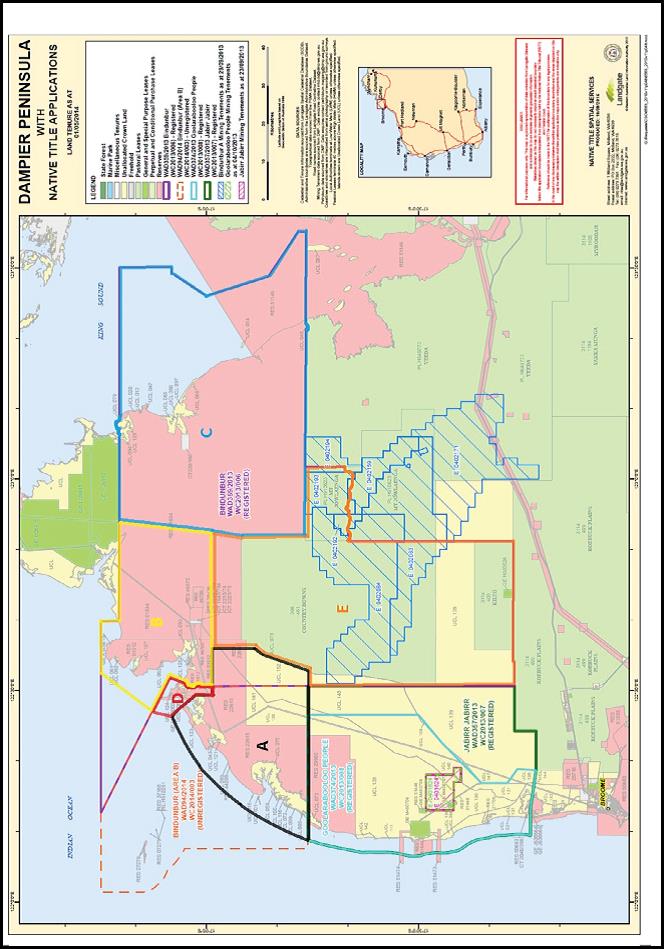

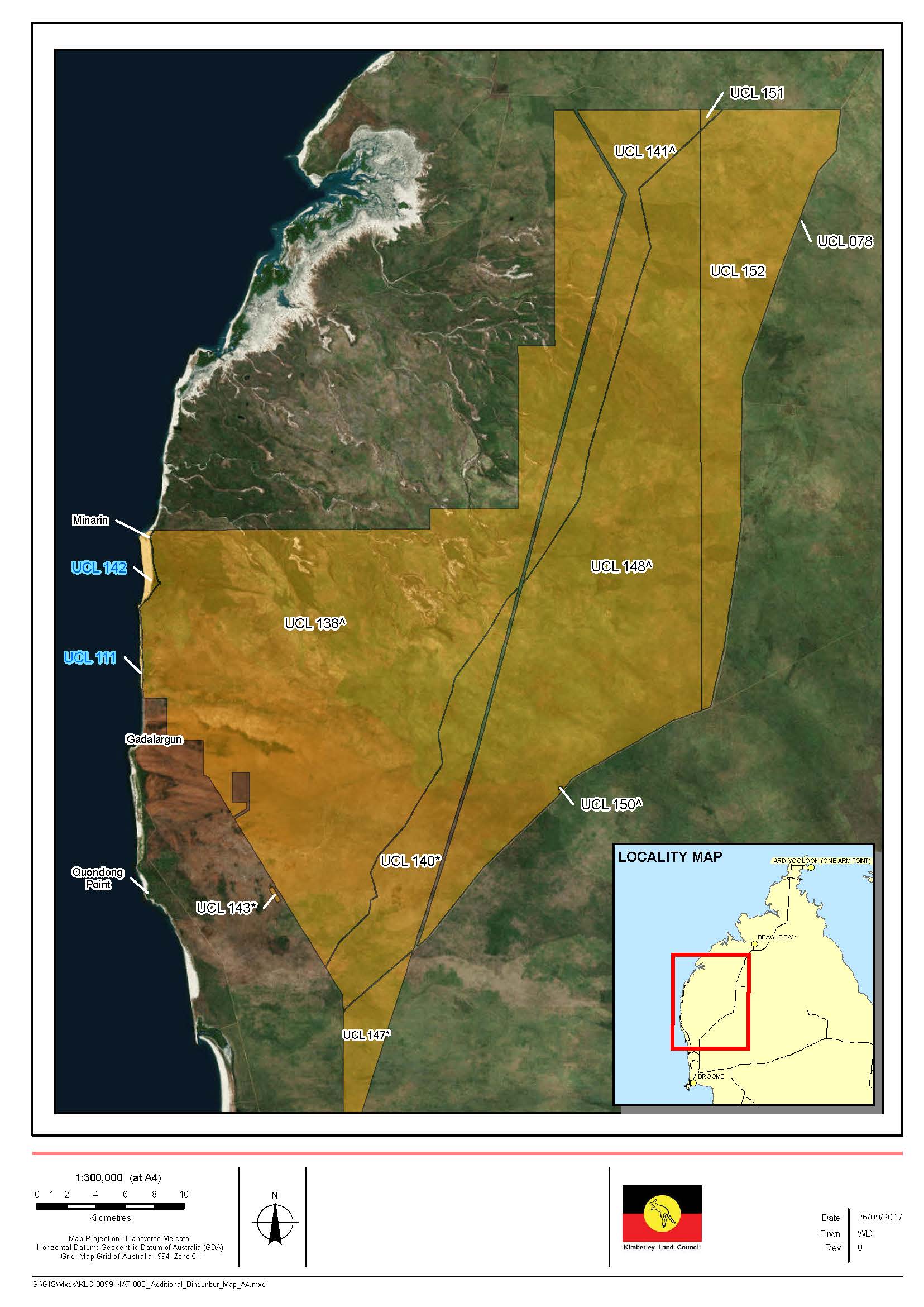

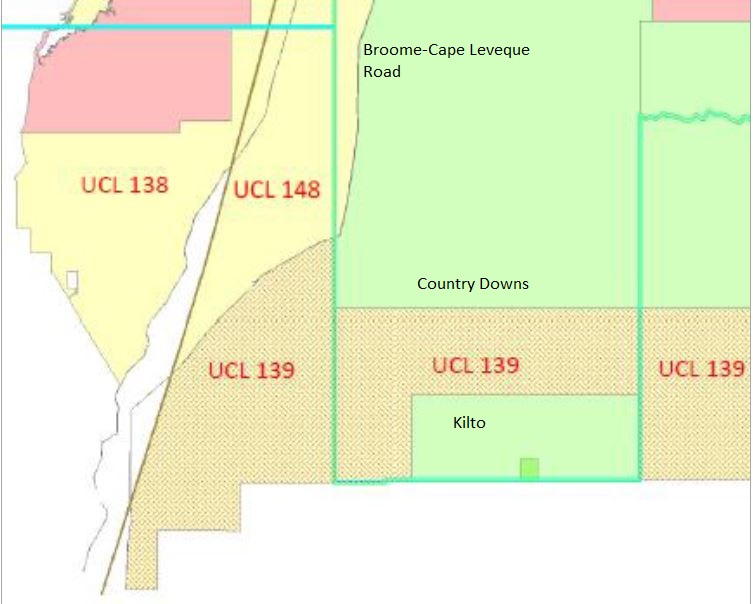

11 The area of each application is shown on the following map which was provided by the Kimberly Land Council (KLC), the representative of the Bindunbur applicants:

12 The following description used in conjunction with the above map is intended to assist the reader to gain a general, but not precise, understanding of the places in the application areas and make it easier to follow some of the later geographical references in these reasons for judgment.

13 The Bindunbur application covers the area starting at Cape Bertholet on the northern boundary of the Coulomb Point Nature Reserve, going north off shore to a point just north of the Lacepede Islands, then east past a portion of Pender Bay, across to the southern side of Goodenough Bay on the east cost of the mid-Dampier Peninsula, out into King Sound, then generally south in King Sound towards Derby, turning west then south at a point to meet up with the upper reaches of the Fraser River, then west again along the Fraser River, then south almost to the Great Northern Highway, then west to a point which extended northward runs parallel to the Broome-Cape Leveque Road, then west to meet up with Cape Bertholet.

14 The Jabirr Jabirr application covers the area from off-shore at Willie Creek tracking off-shore north along the western coast of the mid-Dampier Peninsula to Cape Bertholet, then east along the southern Bindunbur application area boundary, then south along the western Bindunbur application boundary, and generally west from the south western boundary of the Bindunbur application area back to Willie Creek.

15 The Goolarabooloo application covers an area entirely within the Jabirr Jabirr application area, but does not include all of the Jabirr Jabirr application area. The western boundary of the Goolarabooloo application area is the same as the western boundary of the Jabirr Jabirr application area. The southern boundary of the Goolarabooloo application area is the same as the southern boundary of the Jabirr Jabirr application area except that it turns north about halfway between the western and eastern boundaries of the Jabirr Jabirr application area. The eastern boundary of the Goolarabooloo area at the southern end generally follows the Broome-Cape Leveque Road until the boundary tracks directly north to meet the northern boundary about half way between the north east corner of Coulomb Point Nature Reserve and the western boundary of the Bindunbur application area. The northern boundary then turns west along the southern boundary of the Bindunbur application area boundary to Cape Bertholet.

16 The Aboriginal population of the mid-Dampier Peninsula, both historically and today, has been concentrated in the coastal areas. That is explained largely by the ready availability of food sources from the reefs which exist particularly on the western coastline of the application areas. The central area of the mid-Dampier Peninsula is savannah country. There are a number of lakes which fill seasonally. There are also springs which provide fresh water year round. However, on the whole, the conditions for living are more accommodating along the coastal areas.

4. ADJOINING NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATIONS

17 To the immediate south of the three application areas is the Yawuru native title determination area, which was recognised in Rubibi Community v Western Australia (No 6) [2006] FCA 82 (Rubibi). That determination was upheld by the Full Court in Western Australia v Sebastian [2008] FCAFC 65.

18 To the immediate south east of the Bindundur application area is the Nyikina Mangala native title determination area, which was the subject of a consent determination in Watson on behalf of the Nyikina Mangala People v State of Western Australia (No 6) [2014] FCA 545 (Watson).

19 To the immediate north of the Bindunbur application area is the Bardi and Jawi native title determination area, which was recognised in Sampi v Western Australia (No 3) [2005] FCA 1716 (Sampi No 3). The trial judge’s reasons for the determination were published in Sampi v State of Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 (Sampi No 1). The trial judge found that native title did not exist in certain coastal areas within the claim area. An appeal against that finding was allowed in part by the Full Court in Sampi on behalf of the Bardi and Jawi People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2010] FCAFC 99 (Sampi FC).

20 The evidence and submissions in this proceeding were heard over a period of 21 months, comprising 44 hearing days. The following summary of the hearing dates is adapted from the Bindunbur applicants’ submissions on connection.

21 On 21 September 2015, opening statements were made in Broome.

22 Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witnesses gave evidence on country between 22 September and 26 September 2015, then in Broome between 29 September and 2 October 2015, and then at at Lombadina, a community north of the application areas in the Bardi and Jawi native title determination area, on 5 October and 7 October 2015, and also at Beagle Bay on 6 October 2015.

23 On 8 October and 9 October 2015, Bindunbur, Jabirr Jabirr and Goolarabooloo witnesses gave evidence in Broome.

24 Goolarabooloo witnesses gave evidence on country between 29 March and 1 April 2016. Then, Goolarabooloo, Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witnesses gave evidence in Broome between 4 April and 8 April, and between 11 April and 14 April 2016.

25 When necessary, restricted evidence was given on country and in Broome during closed sessions, at which women and non-initiated Aboriginal men were not present.

26 On 21 and 23 September 2016, opening statements on extinguishment were made in Perth. Oral evidence on extinguishment was also given on those dates. On 23 September 2016, expert evidence was given in Perth, then in Broome between 26 and 28 September 2016.

27 Between 28 November and 2 December 2016, expert anthropological evidence was given concurrently in Broome.

28 Between 10 April and 13 April 2017, closing submissions on connection were made in Perth.

29 Between 28 June and 29 June 2017, closing submissions on extinguishment were made in Perth.

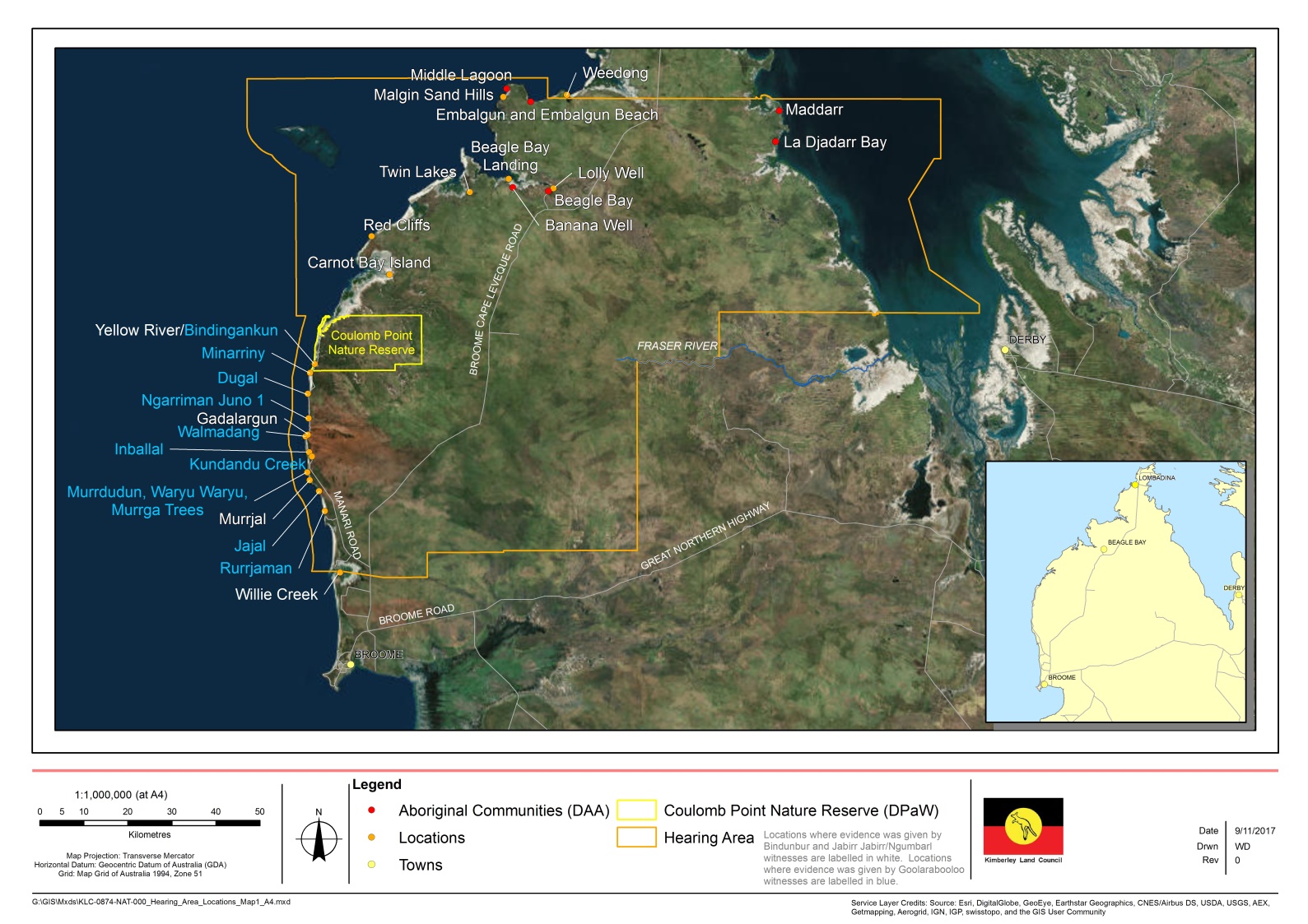

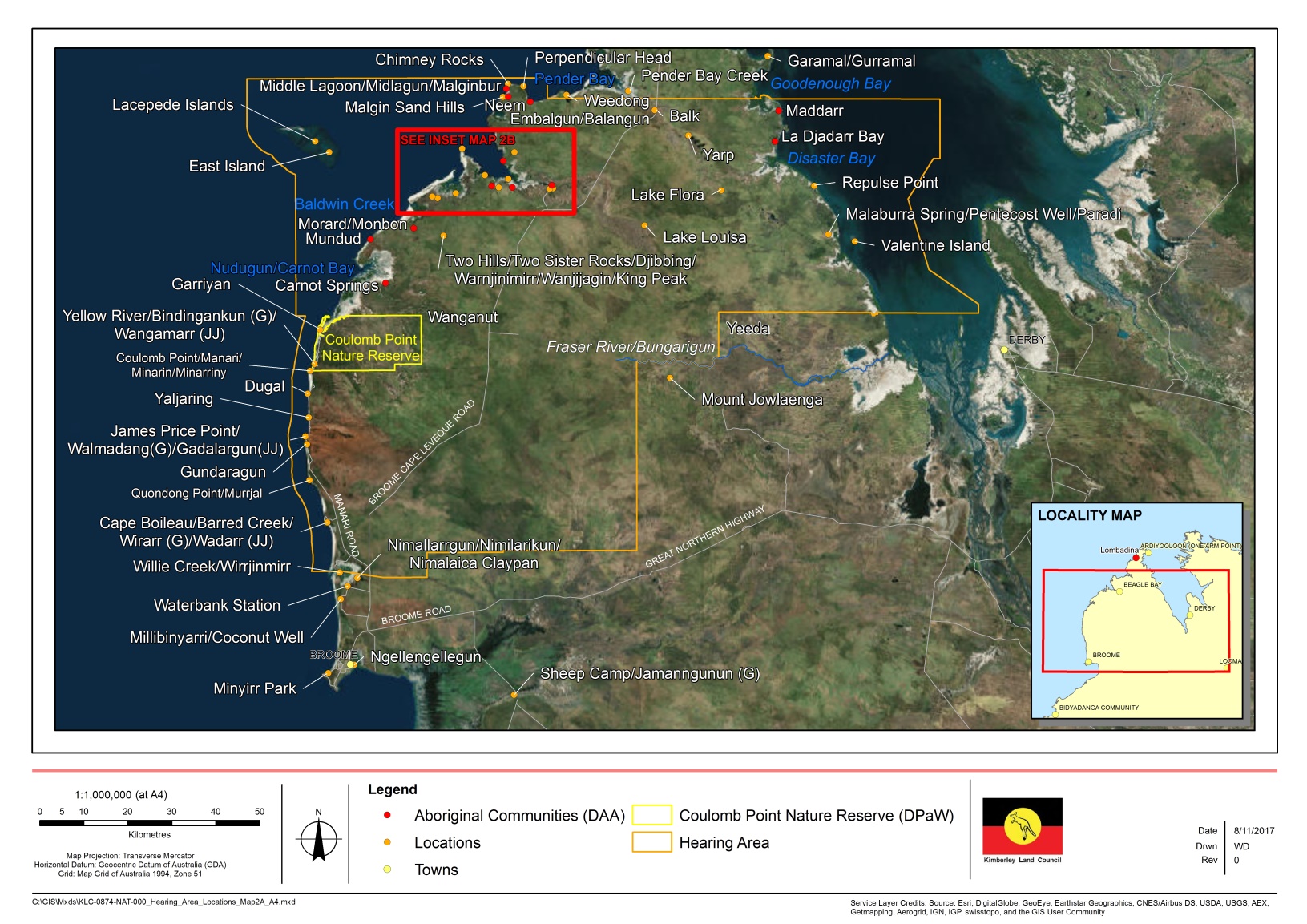

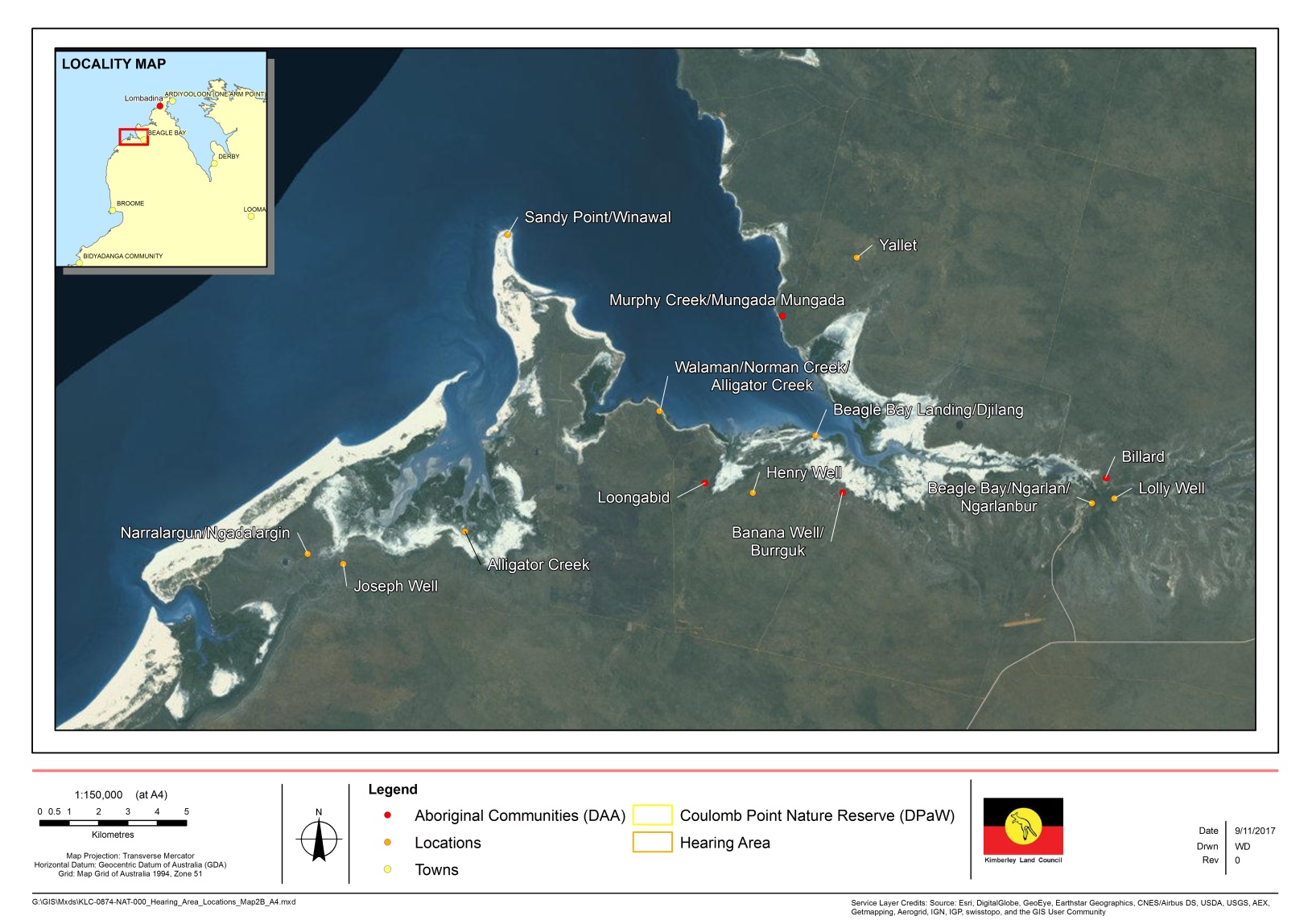

30 The map below, prepared by the KLC and agreed to by the parties, shows the on country hearing locations:

6. THE STRUCTURE OF THESE REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

31 The broad division of subjects in these reasons for judgment is between issues concerned with the connection of the applicants to the application areas and issues concerned with the extinguishment of native title.

32 The parties filed comprehensive written submissions in respect of each of the questions of connection and of extinguishment. A large measure of agreement between the parties emerged in the process of the exchange of submissions and in the course of the hearing. The areas of agreement will be reflected in the terms of the determination ultimately made by the Court. It is not intended to canvas agreed matters in these reasons for judgment, but rather to confine the discussion to the resolution of matters still in contest.

33 The major connection issue addressed in these reasons for judgment is the application made by the Goolarabooloo applicants for native title in the Goolarabooloo application area. That claim is opposed by all the other parties.

34 The Goolarabooloo application rests on the story of the arrival in part of the Jabirr Jabirr application area of Mr P Roe and his wife MP in about 1930. Mr P Roe was an Nyikina man and his wife was a Karijarri woman. The family of Mr P Roe hold the belief that he was given the role of custodian of the Goolarabooloo application area shortly after his arrival by the old people then living in the area. Mr P Roe acquired ritual and mythological knowledge and became a ritual leader in the Northern Tradition and a senior Law man. Mr P Roe and his wife MP had two daughters, Teresa and Margaret. Ms Teresa Roe is now a senior Law woman. She acquired rayi from around Bindingankun, Yellow River.

35 The Goolarabooloo applicants claimed native title rights and interests in several ways. First, they claimed rights and interests by reason of descent from Mr P Roe. Then, they claimed rights and interests by succession following the custodianship granted by the old people of the area to Mr P Roe. Each of these pathways, so it was argued, entitled the Goolarabooloo applicants to native title rights and interests in the entire Goolarabooloo application area. Then, the Goolarabooloo applicants claimed native title rights and interests by reason of the acquisition of ritual and mythological knowledge, first by Mr P Roe and then, in the present day, by his grandsons, Mr Phillip Roe, Mr Richard Hunter and Mr Daniel Roe. Finally, they claimed native title rights and interests from the rayi connection of Ms Teresa Roe. These latter two pathways do not create entitlements in all of the Goolarabooloo people or to the entirety of the Goolarabooloo application area.

36 The Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants, with whom the State and the Commonwealth agreed, denied that the applicable traditional laws and customs entitled the Goolarabooloo applicants to native title rights and interests.

37 Thus, the terms of the applicable traditional laws and customs relating to the acquisition of rights in land was the central connection issue for consideration in the proceeding.

38 Two further issues relating to connection are raised by the applications. First, there is a dispute between the Bindunbur applicants and the State as to whether native title exists in relation to the Lacepede Islands and the surrounding seas which is dealt with in section 13 of these reasons for judgment. Second, there is a dispute between the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr applicants on the one hand, and the State on the other, as to whether the determination should identify land holders by reference to language groups. That matter is dealt with in section 14 of these reasons for judgment.

39 Following consideration of the connection issues, the extinguishment issues are dealt with in sections 15 – 25 of these reasons for judgment. A summary of those issues is set out in section 15 of these reasons for judgment.

7. WHO GAVE EVIDENCE ON CONNECTION ISSUES?

40 The present case illustrates an important feature about native title litigation, particularly in respect of issues of connection. From about 20 years of experience of native title litigation it has been rightly recognised by the Court that the primary source of evidence of the connection of Aboriginal people to land is evidence from those people themselves. That is partly because the laws and customs which govern the acquisition of rights and interests in land has not generally been written down. The tradition is oral. The rules are handed down from generation to generation. Old people have the responsibility in Aboriginal culture of explaining the rules governing their people by educating younger people. Some of that education is imparted through ritual in ancient ceremonial practice. Some is imparted more informally by sitting and speaking and interacting with old people over many years. Knowledge acquired of the laws and customs is highly valued among Aboriginal people. Deep knowledge of the rules governing the society and particularly stories about the creation of the country is a mark of authority among the people.

41 Where the tradition has been recorded in the past by early anthropologists the record has been of variable quality. The improvement in more recent times is probably explained by the developing professionalism over years in the discipline of anthropology, and also by reference to the quality of some of the practitioners. Where the tradition has been recorded by others, such as police authorities or missionaries, the record is often less reliable in that the record was coloured by some of the attitudes of the times adverse to Aboriginal people.

42 Perhaps most significantly for non-Aboridinal judges, the oral evidence of Aboriginal people is usually more able to convey the nature of the spiritual beliefs from which the laws and customs derive and which bind the people to the land. The way in which such evidence is given often displays the extent to which the tradition is both deeply held and is a living tradition governing the everyday lives of the witnesses.

43 Anthropologists perform a very useful role in native title applications. They may set out the scholarship of past anthropologists in the area and provide a professional critique of that body of work to aid the Court’s assessment of it. Often the anthropologists have engaged in fieldwork, sometimes over decades, which allows them to gather the information from members of a claim group and place that information in the context of wider learning about Aboriginal social structures in Australia. Whilst the assistance of anthropologists has been of great assistance to the Court in the development of native title jurisprudence, it is important that the voice of Aboriginal people themselves is acknowledged as the primary source of information about them.

44 In the present case, a large number of the members of the Bindunbur, Jabirr Jabirr and Goolarabooloo claim groups gave evidence. They covered a great range of age, seniority, knowledge and experience. They conveyed to the Court a strong sense of the traditional laws and customs of the people and the fact that the laws and customs are a living and dynamic body of principles governing their society. Even though the formal positions of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr, on the one hand, and the Goolarabooloo, on the other, were opposed, there was a high level of, although not complete, consistency in the evidence of all the Aboriginal witnesses. All of the Aboriginal witnesses were credible and gave evidence honestly, to the best of their memory and knowledge. As a body of evidence it was impressive. The case is largely resolved on the basis of the evidence they gave. It is therefore appropriate to set out in these reasons something about each of those witnesses before addressing their evidence on each of the contested issues.

45 The Bindunbur applicants led evidence from 44 Aboriginal witnesses in relation to the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr application areas. Of those witnesses, 25 gave oral and affidavit evidence. The remaining 19 witnesses gave oral evidence at sites on country. The Jabirr Jabirr applicants did not lead any separate evidence, but instead relied on the evidence led by the Bindunbur applicants, including from people who identified as Jabirr Jabirr, in relation to the Jabirr Jabirr application area. The Goolarabooloo applicants led evidence from 11 Aboriginal witnesses in relation to the Goolarabooloo application area. Nine of those witnesses gave oral and affidavit evidence, and two witnesses gave oral evidence at on country sites. The Goolarabooloo also led lay evidence from two non-Aboriginal witnesses, although only one of those non-Aboriginal witnesses gave oral evidence.

46 This section of these reasons for judgment provides a brief biographical snapshot of each lay witness who gave evidence in these proceedings. Witnesses’ connections to country outside of the application areas have not been included in these snapshots in the interests of brevity. Further, witnesses’ descriptions of the extent of their country has been simplified. The summaries of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witnesses have been adapted from the summary provided in the Bindunbur applicants’ submissions on connection.

47 During the course of the hearing, counsel for the applicants addressed the Aboriginal lay witnesses by their first names. That practice was followed by other counsel and by the Court. In part that practice is explained by the relative informality of on country hearings. It has become usual for that practice to be reflected in the reasons for judgment in native title cases. The practice has not been applied to non Aboriginal witnesses. The Court noted this differential treatment and in the present case consulted the parties as to how the witnesses should be referred to in these reasons for judgment. The consensus among Aboriginal witnesses was that they be treated in the same way as non-Aboriginal witnesses. Consequently, that is the approach taken in these reasons for judgment.

48 The two maps below show some of the main places which are mentioned in the following descriptions of the Aboriginal witnesses and which are mentioned throughout the reasons for judgment:

Mr Stephen (Marbrulla) Victor

49 Mr Stephen Victor is a Nyul Nyul man through both his parents. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Stephen Victor was born in 1944. His father Stanley Victor was the son of Nyul Nyul apical Victor. Mr Stephen Victor gave evidence that his country through Victor is Ngarlanbur, the area where Beagle Bay community is now located. Mr Stephen Victor’s mother was Rosie Waini, whose father was Bonaventure. Bonaventure’s father was Nyul Nyul apical Kandy. Mr Stephen Victor gave evidence that his country through Kandy is the area from Perpendicular Head right down to Embalgun and Weedong and down to Yarp.

50 He lives in Beagle Bay and has a nearby outstation on Ngarlanbur at Billard. He has nine children and 22 grandchildren.

Ms Neenya Tesling

51 Ms Neenya Tesling is a Nyul Nyul and Jabirr Jabirr woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born in 1950 in Broome. Ms Neenya Tesling was raised by Dominic Charles, whose mother was Alberta Augustine, daughter of Martha, whose mother was Jabirr Jabirr apical Flora, whose parents were Jabirr Jabirr apicals Milare and Kelergado. Alberta Augustine was the niece of Nyul Nyul apical Ringarr Augustine. Ms Neenya Tesling gave evidence that her main country is Banana Well (Burrguk), through Alberta Augustine. She acknowledges her connection to Jabirr Jabirr but does not identify as Jabirr Jabirr.

52 Ms Neenya Tesling spent her childhood between Sunday Island, Djarindjin and Beagle Bay. She now lives in Broome. She has raised four children.

Ms Margaret Mary Smith (nee Clement)

53 Ms Margaret Smith is a Nyul Nyul woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. Ms Margaret Smith was born in 1942 at Beagle Bay. Her father was Clement Mouda, whose father was Nyul Nyul apical Patrick Mouda. She gave evidence that her country is Malginbur, also called Malgin country or Midlagun.

54 Ms Margaret Smith grew up at Beagle Bay. She still travels to Malginbur three or four times a year with her family. She has 10 children, and many grandchildren and some great grandchildren.

Ms Cecilia (Cissy) Mary Churnside

55 Ms Cissy Churnside is a Nyul Nyul and Nimanbur woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. Ms Cissy Churnside was born in 1951 at Beagle Bay. Her mother was Magdalene Williams (nee Kelly), whose grandfathers were Nyul Nyul apicals Abraham Kongudu and Felix Nortingbor. Felix was married to Nyul Nyul apical Madeline. Ms Cissy Churnside gave evidence that her country through Felix is Ngarlanbur, and that her country through Abraham is Binduk and Walaman Creek and Loongabid area. She also gave evidence that she has connections to Winawal through Madeline and to Garamal through her father Lawrence Williams, who was a Nimanbur man.

56 Ms Cissy Churnside and her family have a block at Yallet on her country. She has five grandchildren.

Mr Anthony Lee Bevan

57 Mr Lee Bevan is a Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Lee Bevan was born in 1975. His mother is Ms Esther Bevan, the daughter of Anthony Joseph Nicolas (Balangun or Budjun) who is the son of Nyul Nyul apical Kandy. He gave evidence that his country through his mother is called Embalgun (Balangun) which runs from Chimney Rocks to Pender Bay Creek.

Mr Otto Keith Dan

58 Mr Otto Dan is a Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1956 at Beagle Bay. His mother is Mary Martina Louisa Dann, whose father was Ami Dann, the son of Aloyisius. He gave evidence that his country through his grandfather was Winawal.

59 Mr Otto Dan has lived in Arnhem Land since 1977.

Mr Alec Aloysius (Billawitj) Dann

60 Mr Alec Dann is a Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Alec Dann was born in 1957. His father was Albert, the son of Ami, whose father was Aloysius, the son of Nyul Nyul apical Tjangadabul. Mr Alec Dann gave evidence that his country through Tjangadabul is the Winawal area.

61 Mr Alec Dann grew up at Beagle Bay until he was 10.

Mr Gerard Sebastian

62 Mr Gerard Sebastian is a Nyul Nyul man. He was born in 1959 in Broome. His mother was Molly Sebastian, whose father was Jibarji Sebastian, son of Nyul Nyul apical Patrick Mouda. Mr Gerard Sebastian gave evidence that his country through Patrick is Malgin (Midlagun).

63 Mr Gerard Sebastian has lived in the Kimberley all of his life. From 1986 to 2014, Mr Gerard Sebastian lived on country with his family. He has seven children and six grandchildren.

Mr Frederick (Freddie) Charles

64 Mr Freddie Charles is a Nyul Nyul man. His father is Dominic Charles, whose mother was Alberta Augustine, a daughter of Nyul Nyul apical Ringarr. He gave oral evidence at Banana Well that his country through Ringarr is the area around Banana Well. His older sister is Nyul Nyul witness Ms Neenya Tesling.

Ms Philomena (Mena) Lewis

65 Ms Mena Lewis is a Nyul Nyul woman. Her grandfathers were Nyul Nyul apicals Abraham Kongudu and Felix Nortingbor. She gave oral evidence at Beagle Bay landing and Lolly Well that her country through Abraham is the coast around Beagle Bay, and that her country through Felix is Ngarlanbur.

Mr Bruno Alphonse Dann

66 Mr Bruno Dann is a Nyul Nyul man. He is a member of the Dann family through his mother who is sister to Nyul Nyul witness Mr Otto Dan’s mother. He gave evidence that the Dann family’s country is Winawal. He gave oral evidence at Twin Lakes where he harvests gubinge, and where he has lived for the last 15 years.

Mr Benedict Victor

67 Mr Benedict Victor is a Nyul Nyul man. He is the son of Nyul Nyul witness Mr Stephen Victor. He gave oral evidence at Lolly Well that his country through his great grandfather, Nyul Nyul apical Victor, is Ngarlanbur.

Mr Cameron Victor

68 Mr Cameron Victor is a Nyul Nyul man. He is the grandson of Nyul Nyul witness Mr Stephen Victor. He gave oral evidence at Beagle Bay Oval that his country through Mr Stephen Victor’s ancestor Nyul Nyul apical Victor is the Lolly Well area.

Ms Ta’Marrah O’Reeri

69 Ms Ta’Marrah O’Reeri is a Nyul Nyul woman. She is the granddaughter of Nyul Nyul witness Mr Stephen Victor. She gave oral evidence at Lolly Well that she is connected to that area through her great grandfathers, Nyul Nyul apicals Felix Nortingbor and Victor.

Ms Fiona Mary Smith

70 Ms Fiona Smith is a Nyul Nyul woman. She is a daughter of Nyul Nyul witness Ms Margaret Smith and a descendant of Nyul Nyul apical Patrick Mouda. She gave oral evidence at Middle Lagoon.

Ms Deborah Sebastian

71 Ms Deborah Sebastian is a Nyul Nyul woman. She was born in 1963. She is part of the Sebastian and Clements family. She gave oral evidence at Middle Lagoon and Malgin Sand Hills that her country is Midlagun bur. She has eight grandchildren.

Mr Kimberley Francis Smith

72 Mr Kimberley Smith is a Nyul Nyul man. He is the son of Nyul Nyul witness Ms Margaret Smith, who is a descendant of Nyul Nyul apical Patrick Mouda. He gave oral evidence at Malgin Sand Hills. He lives in Kununurra and has six children and two grandchildren.

Mr Willy Smith

73 Mr Willy Smith is a Nyul Nyul man. He is the brother of Nyul Nyul witness Mr Stephen Victor, and was brought up and adopted by Mr Stephen Victor’s parents. He gave oral evidence at Embalgun that his country is the area around Embalgun where he has an outstation.

Ms Esther Bevan

74 Ms Esther Bevan is a Nyul Nyul woman. She was born in 1948. She is the daughter of Anthony Joseph Nicolas (Balangun or Budjun) who is the son of Nyul Nyul apical Kandy. She gave oral evidence at Embalgun that her country through Kandy is Embalgun and Balangun. She is the mother of Nyul Nyul witnesses Mr Lee Bevan and Mr Albert Wiggan.

Mr Albert Wiggan

75 Mr Albert Wiggan is a Nyul Nyul man. His mother is Nyul Nyul witness Ms Esther Bevan, and his brother is Nyul Nyul witness Mr Lee Bevan. He gave evidence that he has been through the Law. He gave oral evidence at Embalgun Beach and Weedong.

Mr Ernest Damien Manado

76 Mr Damien Manado is a Nimanbur and Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Damien Manado was born in 1955. His father was Gerard Manado, son of Mr Jerome Manado whose mother was Nimanbur apical Mary. Mr Damien Manado is also a descendant of Regina Kelly who was Mr Jerome Manado’s wife. Regina Kelly was the daughter of Nyul Nyul apicals Dorothy Kelly and Abraham Kongodu. Mr Damien Manado gave evidence that his country through Mary is Madarr and Disaster Bay to Repulse Point area and down to Fraser River, and that his country through Dorothy Kelly and Abraham Kongodu is Norman Creek back towards Loongabid, up to Murphy Creek and inland past Henry Well, including Banana Well.

77 Mr Damien Manado spent time in Derby, Broome, Beagle Bay and Djarindjin as a child. His sister is Nimanbur witness Manjella Manado. He has five children and 15 grandchildren.

Mr Henry Ah Choo

78 Mr Henry Ah Choo is a Nimanbur man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. His father was Nimanbur apical Bobby Ah Choo, whose father was Nimanbur apical Jidnyambala. He gave evidence that his father’s country is Djanbir Nyiwalgarra, the area between Fraser River and Valentine Island and the Malaburra Spring area.

79 Mr Henry Ah Choo was born in 1944. He worked as a crocodile shooter and pearler around the coast of Nimanbur country as a young man.

Mr Paul Cox

80 Mr Paul Cox is a Nimanbur man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Paul Cox was born in 1930 at Beagle Bay. His mother was Lena Manado and his grandmother was Nimanbur apical Mary. Mr Paul Cox gave evidence that his country through his mother is Madarr, La Djadarr and Disaster Bay, right past Goodenough Bay to Garramal (Garamal) which is a shared area between Nimanbur and Bardi.

81 Mr Paul Cox has lived at Beagle Bay most of his life. He had four children and has many grandchildren and great grandchildren, including his great grandson, Nimanbur, Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr witness Mr Ninjana Walsham.

Ms Ann Majella Manado

82 Ms Majella Manado is a Nimanbur woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. Ms Majella Manado was born in 1952. Her father was Gerard Manado, whose father was Mr Jerome Manado, son of Nimanbur apical Mary. Ms Majella Manado gave evidence that her country through Mary is from Garamal to Fraser River and inland to Balk. Ms Majella Manado is also a descendant of Nyul Nyul woman Regina Kelly whose grandfather was Nyul Nyul apical Abraham Kongodu. Ms Majella Manado has not chosen to go Nyul Nyul way.

83 Ms Majella Manado has lived at La Djadarr and then Madarr since around 1984. She has 17 grandchildren and one great grandchild.

Mr Lawrence (Laurie) John Cox

84 Mr Laurie Cox is a Nimanbur man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1955. His father was Matthew Cox, whose mother was Lena Manado, daughter of Nimanbur apical Mary. He gave evidence that his country through Mary is from Garamal to Fraser River.

85 Mr Laurie Cox has spent his whole life at Beagle Bay and La Djadarr. He has seven children and 17 grandchildren.

Mr Jerome Manado

86 Mr Jerome Manado is a Nimanbur man. He is a descendant of Nimanbur apical Mary. He is a younger brother of Nimanbur witnesses Ms Majella Manado and Mr Damien Manado. He gave oral evidence at Madarr.

Mr Aaron Edward Cox

87 Mr Aaron Cox is a Nimanbur man. At the time he gave evidence he was nearly 26 years old. He gave oral evidence at La Djadarr that his connection to country was through his father’s father, Nimanbur man Theodore Cox.

Ms Carlene Trace Cox

88 Ms Carlene Cox is a Nimanbur woman. She is the daughter of Nimanbur witness Mr Laurie Cox. She gave oral evidence at La Djadarr where she lives with her three children.

Mr P Sampi

89 Mr P Sampi passed away during the hearing of these proceedings. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1932 near the Catholic Mission in Lombadina. He was the only Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr witness who was not a member of one or both of those application groups. He was a very senior Bardi man who was initiated in Bardi and Yawuru Law. Mr P Sampi gave evidence about the initiation ceremonies and stages of the Law in the application areas. He also gave evidence about madja, or Law bosses, and galud, or senior Law bosses. Mr P Sampi gave evidence that he was a galud in Bardi law.

Ms Rita Augustine (Gadalargun) (nee Kelly)

90 Ms Rita Augustine is the most senior Jabirr Jabirr and Ngumbarl woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born near Denham Station in 1934. Her mother’s mother was Ngumbarl Jabirr Jabirr apical Murrjal, and Murrjal’s mother was Ngumbarl Jabirr Jabirr apical Gadalargun. Ms Rita Augustine’s maternal grandfather, and Murrjal’s partner, was Jabirr Jabirr apical Bobbi Blanki. Ms Rita Augustine gave evidence that her country through Murrjal and Gadalargun is Willie Creek, Barred Creek, Quondong, James Price Point and Minarin. Ms Rita Augustine gave evidence that her country through Bobbi Blanki is Narralargun (Ngadalargin), north of Carnot Bay through to Winawal.

91 As a child, Ms Rita Augustine lived with Murrjal and Gadalargun in Ngumbarl country. She spent three years in the Derby Leprosarium with other Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr old people. After being discharged from the Leprosarium, Ms Rita Augustine was taken to Beagle Bay where she married a Nyul Nyul man, Mr Henry Augustine. She has twelve children and many grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Ms Cecilia (Cissy) Djiagween

92 Ms Cissy Djiagween is a very senior Jabirr Jabirr woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born in 1936 at Beagle Bay. Her mother was Jabirr Jabirr apical Senanus. Senanus’ parents were Jabirr Jabirr apicals William Wallai and Mary Nelagumia. Her father’s mother’s mother was Jabirr Jabirr apical Bornal. Ms Cissy Djiagween gave evidence that her country through Mary Nelagumia is Carnot Bay. She also gave evidence that her country through William Wallai is Mundud, and that her country through Bornal is Minarin.

93 Ms Cissy Djiagween lived in Beagle Bay up to the age of about five or six, when she went to live in Broome. She has lived there ever since, apart for about four years in the late 1950s when she returned to Beagle Bay. She has nine children, most of whom have children and grandchildren of their own.

Mr Henry Augustine Jr

94 Mr Henry Augustine Jr is a Jabirr Jabirr, Ngumbarl and Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Henry Augustine Jr was born in 1967. Mr Henry Augustine Jr’s mother is Jabirr Jabirr and Ngumbarl witness Ms Rita Augustine. Mr Henry Augustine Jr gave evidence that his country through his mother is Jabirr Jabirr country, particularly the Ngumbarl area from Murrjal down to Willie Creek. Mr Henry Augustine Jr’s father is Nyul Nyul man Mr Henry Augustine Sr, whose father was Nyul Nyul apical Ringarr Augustine, son of Nyul Nyul apical Walamandjin. Mr Henry Augustine Jr gave evidence that his country through his father is Ringarr burr, which encompasses Walaman (Norman Creek) back along the southern coastline of Beagle Bay to Beagle Bay community, and south to Gundaragun.

95 Mr Henry Augustine Jr was raised at Beagle Bay where he now lives. He has two children and three grandchildren.

Mr Rodney Augustine

96 Mr Rodney Augustine is a Jabirr Jabirr, Ngumbarl and Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Rodney Augustine was born in 1973. His mother is Jabirr Jabirr and Ngumbarl witness Ms Rita Augustine. His father was Nyul Nyul man Mr Henry Augustine Sr.

97 Mr Rodney Augustine attended high school in Broome, and then lived in Tardun and Melbourne. He returned to Broome in early 2015.

Mr Walter Koster

98 Mr Walter Koster is a Jabirr Jabirr man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Walter Koster was born in 1972. Mr Walter Koster’s mother is Kay Koster, the daughter of Antonia, whose mother was Jabirr Jabirr apical Senanus. Mr Walter Koster gave evidence that his country through his mother is Jabirr Jabirr country, particularly Carnot Bay which is known as Nudugun.

99 Mr Walter Koster has lived at Beagle Bay since the 1980s, and visits his country around Carnot Bay every weekend. He has six children and one granddaughter.

Ms Mary Tarran

100 Ms Mary Tarran is a Jabirr Jabirr woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born in 1959. Ms Mary Tarran’s mother is Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Cissy Djiagween. Ms Mary Tarran gave evidence that she is connected to three different areas of Jabirr Jabirr country, namely, Carnot Bay through Jabirr Jabirr apical Mary Nelagumia, Mundud through Jabirr Jabirr apical William Wallai, and Minarin through her grandfather Bunduk, his mother Lika and her mother Jabirr Jabirr apical Bornal.

101 Ms Mary Tarran’s family have had an outstation at Mundud since the 1990s.

Ms Patricia (Pat) Gwen Torres

102 Ms Pat Torres is a Jabirr Jabirr woman. She was born in 1956 in Broome. Ms Pat Torres’ mother was Mary Theresa Barker (nee Torres), daughter of Jabirr Jabirr apical Matilda, whose parents were Jabirr Jabirr apicals Milare and Kelergado. Ms Pat Torres gave evidence that her country through Milare is Minarin, and her country through Kelergado is Winawal.

103 Ms Pat Torres’ family have two blocks on Winawal. She has lived on one of those blocks, Milare Community, for nine years. She has five children and five grandchildren.

Mr Alphonse Balacky

104 Mr Alphonse Balacky is a Ngumbarl, Jabirr Jabirr and Nyul Nyul man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1975. Mr Alphonse Balacky’s mother’s mother is Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Rita Augustine. Mr Alphonse Balacky gave evidence that his country through Ms Rita Augustine’s ancestor, Jabirr Jabirr apicals Murrjal and Gadalargun, is southern Jabirr Jabirr around Gadalargun and Murrjal. Mr Alphonse Balacky’s mother’s father was Mr Henry Augustine Sr, son of Nyul Nyul apical Ringarr. Mr Alphonse Balacky gave evidence that his country through Ringarr is the south side of Beagle Bay from Norman Creek up to Beagle Bay community. Mr Alphonse Balacky’s father, Mr Damien Balacky Snr, was a Goolarabooloo witness.

105 Mr Alphonse Balacky gave evidence that he is an initiated Law man for Jabirr Jabirr. He has six children.

Mr Anthony Watson

106 Mr Anthony Watson is a Jabirr Jabirr man. He was born in 1971. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He gave evidence that his mother was Agnes, daughter of Antonia, whose mother was Jabirr Jabirr apical Senanus. His country through Senanus is Jabirr Jabirr country, focusing on Carnot Bay up to Morard.

107 Mr Anthony Watson’s family have blocks at Morard and Monbon in the Carnot Bay area. Since 29 September 2014 he has been the chairperson of the KLC.

Ms Elizabeth (Betty) Dixon

108 Ms Betty Dixon is a Jabirr Jabirr woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born in 1952. Her mother was Mary Josephine Torres, the daughter of Jabirr Jabirr apical Matilda and granddaughter of Jabirr Jabirr apicals Keleragado and Milare. Ms Betty Dixon gave evidence that her country through Matilda is Winawal.

109 Ms Betty Dixon had eight children with Jabirr Jabirr witness Mr Dixon. In 1985, she and Mr Dixon got a lease over a block at Carnot Bay. She has been living in Broome since 2006.

Mr Ninjana Walsham

110 Mr Ninjana Walsham is a Nimanbur, Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1994. He is the great grandson of Nimanbur witness Mr Paul Cox. Mr Ninjana Walsham’s mother is Nimanbur, Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Devina Cheryl Cox, the daughter of Lorna Kelly Cox who was the granddaughter of Ngumbarl Jabirr Jabirr apical Murrjal. Mr Ninjana Walsham gave evidence that his country through his great-grandfather, Mr Paul Cox, is the Nimanbur burr. He gave evidence that his country through his grandmother, Lorna Kelly Cox, is Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr country.

111 Mr Ninjana Walsham was raised by his great grandfather Mr Paul Cox at Beagle Bay.

Mr James Kelly

112 Mr James Kelly is a Ngumbarl man. Mr James Kelly’s mother Ida is a sister of Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Rita Augustine. He gave oral evidence at Gadalargun that he has a connection to that place through his great-grandmother Ngumbarl Jabirr Jabirr apical Murrjal and her mother, Ngumbarl Jabirr Jabirr apical Gadalargun.

113 Mr James Kelly gave evidence that he has been through Law. He was grown up by Mr P Roe, Paddy Sebastian, and PR’s daughter Selma (Thelma).

Mr G Dixon

114 Mr G Dixon passed away during the hearing of these proceedings. He was a Jabirr Jabirr man and was married to Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Betty Dixon. His mother’s father was Jabirr Jabirr apical Frank Dinghi, also known as Frank Dixon. Mr Dixon gave oral evidence at Red Cliffs.

Ms Deanne Williams

115 Ms Deanne Williams is a Jabirr Jabirr woman. Her mother Elaine is a daughter of Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Rita Augustine. She gave evidence that she has links to country through Ms Rita Augustine’s ancestors, Jabirr Jabirr apicals Murrjal and Gadalargun, and Bobby Blanki. She gave oral evidence at Red Cliffs.

Ms Devina Cheryl Cox

116 Ms Devina Cheryl Cox is a Nimanbur, Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr woman. Her grandmother is Jabirr Jabirr witness Ms Rita Augustine. Her grandfather is Nimanbur witness Mr Paul Cox. She is the mother of Nimanbur, Ngumbarl and Jabirr Jabirr witness Mr Ninjana Walsham. She has an outstation near Red Cliffs called Bungard. She gave oral evidence at Red Cliffs.

Ms Teresa Roe

117 Ms Teresa Roe is a very senior Goolarabooloo woman. She gave oral and affidavit evidence. She was born around 1936 at Waterbank Station. She is the daughter of Goolarabooloo apicals Mr P Roe, a Nyikina man, and his wife MP, a Karajarri woman. Ms Teresa Roe gave evidence that her rayi, a spirit child, is from Bindingankun, which is therefore a special place for her, and that because her rayi is from Jabirr Jabirr country that she is a Jabirr Jabirr person. She also gave evidence that her country is from Bindingankun to Barred Creek.

118 Ms Teresa Roe had 10 children, two of whom, Mr Phillip Roe and Mr Ronald Roe, were Goolarabooloo witnesses. A third son, Mr J Roe, was a named applicant in the Goolarabooloo application but passed away before the hearing of these proceedings. She has many grandchildren, four of whom, Mr Jason Roe, Mr Errol Roe, Mr Daniel Roe and Mr Brian Councillor, were Goolarabooloo witnesses. Ms Teresa Roe’s sister Margaret had nine children, who Ms Teresa Roe grew up. One of Margaret’s children, Mr Richard Hunter, is a Goolarabooloo witness, as is one of Margaret’s grandchildren, Mr Terrence Hunter Jr.

Mr Phillip James Roe

119 Mr Phillip Roe is a senior Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1960 in the Old Native Hospital in Broome. His mother is Ms Teresa Roe. Mr Phillip Roe is married to Agnes, a Nimanbur woman, with whom he has six children and 15 grandchildren. He gave evidence that Mr P Roe was handed the right to look after the country from around OTC, through Willie Creek to round Yellow River and Spring Creek, and that that right was then passed on to Mr P Roe’s family, including Mr Phillip Roe.

120 Mr Phillip Roe gave evidence that he is a Law boss for the Northern Tradition. Mr Phillip Roe gave evidence that he and Mr Richard Hunter speak for ululong, a stage in the initiation ritual in the Northern Tradition, as far as the OTC law grounds. He has a camp at Walmadang (Walmadany).

Mr Richard Hunter

121 Mr Richard Hunter is a senior Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1957 at the Old Native Hospital in Broome. His mother was Margaret Hunter (nee Roe), a daughter of Goolarabooloo apicals Mr P Roe and his wife MP. Mr Richard Hunter gave evidence that along with his cousin Mr Phillip Roe, he is responsible for looking after Goolarabooloo country, which is the area between Garriyan and Ngellengellegun.

122 Mr Richard Hunter gave evidence that he is a Law boss for the Northern Tradition. He has a daughter, who lives in Port Hedland.

Mr Terrence Hunter Jr

123 Mr Terrence Hunter Jr is a Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1980 in Port Hedland. Mr Terrence Hunter Jr’s father is Terry Hunter Sr, son of Margaret Hunter (nee Roe). He gave evidence that Goolarabooloo country is as far as Mr P Roe walked, from Barred Creek to Carnot Bay.

124 Mr Terrence Hunter Jr gave evidence that he was initiated in the Northern Tradition, and works on the Lurujarri Heritage Trail. He gave evidence that he does most of the talking on the Lurujarri Heritage Trail from Walmadang to Bindingankun. He has four children.

Mr Brian John Councillor

125 Mr Brian Councillor is a Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1978 in Broome. His father was Willie Roe, son of Ms Teresa Roe. He was brought up by Mr P Roe. He gave evidence that his country through Mr P Roe is from Broome to Carnot Bay. Mr Brian Councillor’s partner is a Nyul Nyul woman whose country is Winawal.

126 Mr Brian Councillor gave evidence that he is initiated in the Northern Tradition, and works on the Lurujarri Heritage Trail. He has a daughter.

Mr Jason David Roe

127 Mr Jason Roe is a Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1977 in Broome. His father was Patrick Roe, son of Ms Teresa Roe. Mr Jason Roe’s brothers, Mr Daniel Roe and Mr Errol Roe, are both Goolarabooloo witnesses. He gave evidence that his family speaks for the country from Bindingankun (Bidingangun) to Minyirr Park in Broome.

128 Mr Jason Roe gave evidence that he is initiated in the Northern Tradition. He works with the Yawuru as a cultural advisor and cultural monitor, working from Minyirr through OTC to Willie Creek. He has two sons.

Mr Ronald Leslie Roe

129 Mr Ronald Roe is a Goolarabooloo man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in 1958 at the Old Native Hospital in Broome. His mother is Ms Teresa Roe. His brother Mr Phillip Roe was also a Goolarabooloo witness. He gave evidence that Goolarabooloo country runs from Broome to Bindingankun.

130 Mr Ronald Roe gave evidence that he has not been through the Law. He works on the Lurujarri Heritage Trail, as the logistics officer and cook. He has two children.

Mr Daniel Roe

131 Mr Daniel Roe is a Goolarabooloo man. His father was Patrick Roe, son of Ms Teresa Roe. Mr Daniel Roe’s brothers, Mr Errol Roe and Mr Jason Roe, are both Goolarabooloo witnesses. He gave oral evidence at Dugal that one of his sons has a rayi from Dugal, and that as a result his son has responsibility for the area from Walmadang to Minari.

132 Mr Daniel Roe gave evidence that he is initiated in the Northern Tradition. He has four children.

Mr Errol Roe

133 Mr Errol Roe is a Goolarabooloo man. His father was Patrick Roe, son of Ms Teresa Roe. His brothers, Mr Daniel Roe and Mr Jason Roe, are both Goolarabooloo witnesses. Mr Errol Roe gave oral evidence at Minarriny, Dugal and Jajal that his great-grandfather was made a custodian for the country in the Goolarabooloo application area.

134 Mr Errol Roe gave evidence that he is initiated in the Northern Tradition.

Mr Damien Balacky Sr

135 Mr Damien Balacky Sr is a Bardi man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He is not a member of the Goolarabooloo application group. He was born around 1952 in Djarindijn near Lombadina. Mr Damien Balacky Sr’s son, Mr Alphonse Balacky, is a Jabirr Jabirr and Bindunbur witness.

136 Mr Damien Balacky Sr gave evidence that he is a galud, or Senior Law boss in the Northern Tradition.

Mr Vincent Angus

137 Mr Vincent Angus is a Jawi man. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He is not a member of the Goolarabooloo application group. He was born in 1954. Mr Vincent Angus has a number of family ties to the Goolarabooloo application group. Topsy Roe, Mr P Roe’s sister, was married to Mr Vincent Angus’s grandfather, Lockie Bin Sali. Goolarabooloo witness Mr Richard Hunter’s father, Jimmy Hunter, was Mr Vincent Angus’s first cousin, and was brought up by Mr Vincent Angus’s mother from the age of three or four. Mr Vincent Angus was married to Bernadette Kelly, a Ngumbarl woman. The Kelly family, including the Augustine and Nicholas families from Beagle Bay, are his in-laws.

138 Mr Vincent Angus gave evidence that he is a madja, or Law boss, in the Northern Tradition.

Mr Folmer Frans Hoogland

139 Mr Frans Hoogland is a non-Aboriginal witness for the Goolarabooloo. He gave oral and affidavit evidence. He was born in the Netherlands in 1943 and migrated to Australia in 1968. Mr Frans Hoogland gave evidence that he arrived in Broome in the mid-1970s, and began working for Mr P Roe around 1980 to document the places and sites making up the song cycle in and around the Goolarabooloo application area.

140 Mr Frans Hoogland gave evidence that he is not initiated in the Northern Tradition. In 1988, he was involved with Mr P Roe in setting up the Lurujarri Heritage Trail.

Ms Ketrina Ray Keeley

141 Ms Ketrina Ray Keeley is a non-Aboriginal witness for the Goolarabooloo. She works for the Goolarabooloo Millibinyarri Indigenous Corporation in an administrative capacity. She affirmed an affidavit dated 8 July 2015 annexing a bundle of photographs which show Goolarabooloo witnesses involved in the practice of traditional ceremonies.

142 Nine witnesses were called by the parties to the proceeding to give expert evidence in relation to connection by the parties to the proceedings.

143 Five anthropologists gave evidence concurrently over five days in Broome. They also participated in an Experts’ Conference in August 2015. Each of the five primary anthropologists filed an expert report on connection issues in 2015, and a supplementary report in 2016 responding to issues raised at the Experts’ Conference, in particular, assessing what came to be known as the “PR story”.

144 The other four expert witnesses, namely, an anthropologist dealing with the genealogical data, a historian, an anthropologist and archaeologist dealing with heritage protection, and a professor of ethnography specialising in discourse analysis, gave oral evidence individually in addition to filing expert reports.

145 What follows is a brief summary of the qualification, experience and approach of each of the expert witnesses.

146 The Bindunbur applicants called four expert witnesses on connection issues. Those expert witnesses were called on behalf of both the cases for the Bindunbur applicants and the Jabirr Jabirr applicants.

Dr James Weiner

147 Dr Weiner is an anthropologist who received his PhD in 1984 from the Australian National University. He was Professor of Anthropology at the Universities of Adelaide (1994-1998) and St. Andrews (2008-2010).

148 Dr Weiner has conducted native title research as a consultant, primarily in Queensland and Western Australia, since 1998. That research has included the submission of full connection reports in seven native title claims across Australia. Dr Weiner has previously conducted research in the application areas on behalf of the KLC. That previous research included a desktop study in 2011, and a series of cultural mapping meetings in 2012.

149 Dr Weiner conducted four field trips to the Dampier Peninsula area in 2013 and 2014, comprising a total of 51 days of travel. The only Goolarabooloo application group member Dr Weiner interviewed was the late Mr J Roe. Dr Weiner submitted a primary report, dated 1 April 2015 and a supplementary report, dated 15 August 2016, a notice of change of opinion dated 24 September 2016 and a further supplementary expert report dated 25 November 2016. He also participated in the five day hearing of the concurrent evidence.

Mr Geoffrey Bagshaw

150 Mr Bagshaw is an anthropologist with an honours degree in anthropology and has practised as a consultant anthropologist for 29 years across Australia. He has been involved as a senior researcher, expert witness, advisor or peer reviewer in 20 separate native title claims and has been appointed as an expert anthropologist by the Court twice in 2002 and 2003.

151 Mr Bagshaw has previously undertaken extensive research in and around the Dampier Peninsula since 1994, including periods of fieldwork. He authored the main expert anthropologist’s report for the applicant in both the Bardi and Jawi native title claim and the Karajarri native title claim. As the Court appointed expert anthropologist, he also authored a fieldwork-based report in the Djabera-Djabera native title claim, which was coextensive with much of the same lands and waters under consideration in the present proceedings.

152 Mr Bagshaw conducted two field trips to the Dampier Peninsula area in 2013 and 2014, comprising a total of 36 travel days. He also conducted further telephone interviews with Aboriginal residents of the Dampier Peninsula. The only member of the Goolarabooloo application group to whom he spoke was the late Mr J Roe. He also spoke to Mr Vincent Angus, a Bardi man who gave evidence for the Goolarabooloo applicants. Mr Bagshaw submitted a primary report, dated April 2015, and a supplementary report, dated August 2016. He also participated in the five day hearing of the concurrent evidence.

Ms Catherine Wohlan

153 Ms Catherine Wohlan is an anthropologist. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Australian National University. She has previously been a senior anthropologist at the KLC and a lecturer in Aboriginal studies at the University of Notre Dame in Broome. She has been a consultant anthropologist since 1998.

154 In 2012, Ms Wohlan was engaged by the KLC to create a new digital genealogical database for the purposes of native title claims for the Nyul Nyul, Jabirr Jabirr, Nimanbur and the then-proposed Mid-Dampier Peninsula claim. In these proceedings, Ms Wohlan submitted an expert report, dated 2 April 2015, which detailed the methodology employed to identify, assemble and update the genealogical data presented in the genealogical database.

Dr Fiona Skyring

155 Dr Fiona Skyring is an historian. She received her PhD in 1998 from the University of Sydney. From 1999 to 2005 she was employed by the KLC as a historian. She has prepared historical reports for native title applicants and reviewed historical records in relation to Aboriginal land rights in Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria. Dr Skyring provided expert evidence regarding the history of the Bardi and Jawi application area in Sampi No 1. She also provided expert historical evidence in the Yawuru claim in Rubibi.

156 Dr Skyring submitted a report, dated April 2015, detailing the post-sovereignty history of the application areas.

Dr Janelle White

157 Dr Janelle White was the only expert witness called by the Jabirr Jabirr applicants. She is an anthropologist. She received her PhD in applied anthropology in 2012 from the University of South Australia and has been working in Aboriginal Australia for almost 15 years, primarily in the area of Aboriginal community consultation and development. She has previously spent nine months working on native title.

158 Dr White conducted research over a period of six months from the end of 2014 to the beginning of 2015. She conducted four trips to country. She was unable to speak to any members of the Goolarabooloo application group. Dr White submitted a primary report, dated April 2015, a supplementary report, dated August 2016, and a change of opinion report dated 24 November 2016. She also participated in the five day hearing of concurrent evidence.

159 The Goolarabooloo applicant called three expert witnesses in relation to connection issues.

Professor Scott Cane

160 Professor Scott Cane is an anthropologist who has been working in the field with Aboriginal people since 1980. He holds a PhD in the material culture, traditional settlement and subsistence patterns of Aboriginal people around Balgo Hills Mission in the Great Sandy Desert. He has prepared connection materials and opinions in relation to 16 separate native title claims. He has also conducted a considerable amount of archaeological research across Australia.

161 Professor Cane’s engagement with the Kimberley has been limited. He first visited the area in 1980, which included a visit to the Goolarabooloo application area. In 2012 he was asked by the State of Western Australia to provide advice regarding the interests of Law bosses in relation to proposed developments at James Price Point.

162 Professor Cane conducted three fieldwork visits to the application areas, comprising a total of 27 travel days. Apart from one informal interview with members of the Bin Sali, Pigram and Torres families who he identified as Jabirr Jabirr on the beach at Yellow River, he did not speak to any members of the Jabirr Jabirr or Bindunbur application groups. Professor Cane submitted a primary report, dated 29 June 2015, a supplementary report, dated 18 August 2016, and a change of opinion report dated 19 September 2016. He also participated in the five day hearing of concurrent evidence.

Professor Stephen Muecke

163 Professor Stephen Muecke is Professor of Ethnography at the University of New South Wales. He has worked as an academic ethnographer since 1975. He was awarded a PhD by the University of Western Australia in 1981. His PhD was entitled “Australian Aboriginal Narratives in English: A Study in Discourse Analysis”, and involved working with Mr P Roe and other senior Aboriginal men in the West Kimberley. Professor Muecke has published two books featuring stories by Mr P Roe, Gularabulu (Fremantle Press, 1983) and Reading the Country (Fremantle Press, 1984). He is currently working on a project funded by the Australian Research Council documenting the Lurujarri Trail country north of Broome, using his notes and recordings of Mr P Roe.

164 Professor Muecke submitted an expert report, dated 1 April 2015.

Mr Nicholas Green

165 Mr Nicholas Green is an anthropologist and archaeologist. He holds a Master of Arts and a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology and Prehistory from the Australian National University. He has 35 years professional experience as an anthropologist and archaeologist for Government, non-Aboriginal organisations and Aboriginal organisations. He has undertaken extensive fieldwork with Aboriginal people, including in the Kimberley, mostly on heritage related work. Mr Green worked with Mr P Roe between 1980 and 1984 on the protection of Aboriginal sites, which included an ethnographic survey along the Kimberley coast north and south of Broome.

166 Mr Green submitted an expert report, dated 2 April 2015.

1.2.5 State of Western Australia witnesses

Professor Peter Sutton

167 Professor Peter Sutton is an anthropologist. He was the only expert witness called by the State of Western Australia on connection issues. Professor Sutton was awarded a PhD in anthropology in 1979 by the University of Queensland. He has carried out fieldwork in Aboriginal Australia since 1969, and has assisted in some sixty or more land claim cases, including native title claims. He is currently an Affiliate Professor, at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide.

168 Professor Sutton did not carry out any anthropological field work with any members of the application groups. He submitted a primary report, dated 15 July 2015, and submitted a supplementary report, dated 15 August 2016. He also participated in the five day hearing of concurrent evidence.

1.2.6 Some general considerations concerning some of the expert evidence

169 The expert anthropologists whose views were centrally relevant to the determination of the issues concerning the traditional laws and customs about the acquisition of rights and interests in land were Mr Bagshaw, Dr Weiner, Dr White, Professor Sutton, and Professor Cane.

170 All those experts have had considerable experience in the native title area. Dr White is somewhat more junior in the profession. Each of the others is recognised as preeminent in their profession. The experience of each of the five experts was reflected in the high quality of the reports written by them and in the evidence given by them.

171 One feature of the expert evidence should be explained. The written reports of Mr Bagshaw, Dr Weiner, Dr White and Professor Sutton generally supported the conclusion that the Goolarabooloo applicants have not acquired rights and interests in land under traditional laws and customs.

172 That expert view also reflected the evidence of the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr Aboriginal witnesses. Furthermore, as will be explained later in these reasons for judgment, properly understood, it also reflected the evidence of most of the Goolarabooloo Aboriginal witnesses.

173 The written reports of Professor Cane, however, reflected the conclusion that the Goolarabooloo applicants have acquired rights and interests in land under traditional laws and customs. The case of the Goolarabooloo applicants stated in their SFIC followed the approach articulated by Professor Cane in his written reports.

174 However, some of the foundations of Professor Cane’s approach have not been accepted by the Court.

175 In concurrent evidence Professor Cane made several concessions which went to the heart of his approach and undermined the conclusions he had expressed in his written reports.

176 On some other matters central to his reasoning, the factual basis upon which he relied could not be made out.

177 The Bindunbur applicants, in particular, attacked the evidence of Professor Cane, in essence, on the basis that he had acted as an advocate for the Goolarabooloo applicants and thereby compromised his professional judgment.

178 In the end, as explained later in these reasons for judgment, the evidence of Mr Bagshaw, Dr Weiner, Dr White and Professor Sutton, where it conflicts with the evidence of Professor Cane, has been preferred.

179 That does not mean that Professor Cane’s professional role was compromised.

180 Professor Cane is a clever, enthusiastic and empathetic person, as well as a very accomplished professional. His reports and evidence reflected all these attributes.

181 Professor Cane certainly viewed the circumstances favourably to the Goolarabooloo applicants where possible. His enthusiasm for that view may have coloured his assessment of some of the necessary underlying factual judgements. He may also have been too ready to transpose his deep knowledge of the Western Desert social structures to the different circumstances of the mid-Dampier Peninsula. However, when faced with this criticism, he accepted his limitations where he thought the criticism was justified. It is apparent that Professor Cane had sympathy for the history of the Roe family. The thesis he proposed took into account the story that Mr P Roe had been given a role by the old people of the area and that he had undertaken that role. It also took into account that he was recognised as a man with ritual and mythological knowledge and was accepted as a senior Law man. It further took into account that Mr P Roe was a spokesperson for his people and a bridge between them and the European authorities. Mr P Roe initiated the Lurujarri Heritage Trail which has been in operation since and which has provided cultural education to both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people about the culture and stories relating to the coastline of the Goolarabooloo application area. Professor Cane took into account that the Roe family have been participants in the community for over 80 years. He also took into account the role in Law that is now performed by Mr P Roe’s grandsons, Mr Phillip Roe, Mr Richard Hunter and Mr Daniel Roe. There is an element in Professor Cane’s analysis which suggests that fairness requires that traditional law and custom must have a way of including the Roe family as holders of rights to land in view of their historical role. Professor Cane’s view was sympathetic to the Goolarabooloo applicants. It was not necessarily unprofessional for that reason.

8. HISTORY OF THE APPLICATION AREA

182 The consequences of white settlement, of the pearling industry, of the coming of missions to the area, and of the removal of children had serious impacts on the Bindunbur, Jabirr Jabirr and Ngumbarl people of the area at the time. The movement of people away from their country figures in the arguments addressed later in these reasons for judgment about the claimed succession of the Goolarabooloo applicants to land in the Goolarabooloo application area. The development of Aboriginal land rights in the 1960s and 1970s and the passing of the NTA in 1992 also had effects on the Bindunbur, Jabirr Jabirr and Goolarabooloo people relevant to this proceeding. Indeed, the schism between the Bindunbur and Jabirr Jabirr people on the one hand, and the Goolarabooloo people on the other was explained by some witnesses as a result of the gas hub dispute in 2009. The account of these events is outlined in this section of these reasons for judgment and is largely adapted from the report of Dr Skyring.

183 The first recorded observations of Aboriginal people on the Dampier Peninsula occurred in the latter half of the seventeenth century. In 1644, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman landed just south of Carnot Bay and observed Aboriginal people there.

184 The next recorded observation of Aboriginal people in the region occurred in 1687-88 at Cygnet Bay, just north of the application areas and within the Bardi and Jawi native title determination area. French J, as he then was, recorded that interaction in Sampi No 1 as follows:

644. William Dampier, the English maritime explorer, sailed the vessels Cygnet and Roebuck from the Philippines to England in 1687 and in the course of that voyage landed on the north west shore of King Sound at Cygnet Bay. He recorded observations of the Aborigines of the area including his often quoted description of them as ‘the miserablest people in the world’. He recorded that as they ran away from his anchored ship they called out the word ‘gurri’. This was said by the applicants’ linguist expert, Dr Metcalfe, to be consistent with the Bardi word ‘ngaari’ which refers to a malevolent spirit. The people whom Dampier saw at Cygnet Bay lived in groups of 20 to 30. They had no houses and, according to Dampier, no boats and no canoes. Dr Skyring however noted that later European explorers recorded the Aborigines use of rafts made from tree trunks.

645. Dampier observed the use of stone fish traps and that, at low tide, the people would seek cockles, mussels and periwinkles. Whether the catch was small or large:

‘... everyone has his part, the young and tender as well as the old and feeble.’

He saw little in the way of weaponry but some of the people had wooden swords and others a kind of lance. He described the sword as ‘a piece of Wood shaped somewhat like a Cutlass’. The lance was ‘a long straight Pole, sharp at one end and hardened afterwards by heat’. Dampier and his crew remained ashore at Cygnet Bay for about two months. The first landing was accidental due to his taking a route home from the Philippines which was south of the regular route and being forced by winds even further south.

185 In 1801, Nicholas Baudin led a French scientific expedition that travelled north up the Western Australian coast from Cape Leewin. Roughly 50 kilometres north of Broome, around James Price Point, Baudin recorded:

The land running down to the shore was two distinct colours. In some places it was a rather bright red; in others there was very white sand, which seemed to indicate easy landing.

Throughout the afternoon we saw a great number of fires all along the coast. But some of them were so large, that it seemed to us that they could not be where the natives were. They were probably conflagrations in some parts of the forest, for there was so much smoke that it blotted out the sky.

186 Then, in 1821, Phillip P. King sailed along the western coast of the Dampier Peninsula in the Bathurst. He wrote of the country between Carnot Bay and Point Coulomb:

[T]he smokes of fires have been noticed at intervals every four or five miles along the shore, from which it may be inferred that this part of the coast is very populous.

187 Dr Skyring concluded from these sources that Aboriginal people occupied the application areas prior to sovereignty. However, she noted that none of these records identified Aboriginal people by language or tribe. This total lack of ethnographic detail was explained by the fact that the goals of the Europeans were strictly mercantile or cartographic.

188 Justice French recorded the formal history of the colonisation of Western Australia in Sampi No 1 as follows:

650. … In April 1829 Captain Fremantle raised a British flag at the Swan River and claimed for the British Crown the remainder of the continent not included in the Colony of New South Wales. On 18 June 1829, James Stirling, the first Governor of the new colony, read a proclamation declaring the western part of the continent to be British territory and its inhabitants and colonists subject to the laws of England.

189 At [653], French J noted that at the time of sovereignty in 1829, there were no European settlements in the Kimberley. The first visit to the region after sovereignty was in 1837, when Commander J. Lort Stokes travelled on the HMS Beagle to explore the north-west coast. French J noted Stokes’ observations as follows:

654. Stokes’ account of his explorations included observations of the coast north of Roebuck Bay along the Dampier Peninsula coastline in January 1838. The coast seemed particularly populated between Roebuck and Beagle Bays. The smoke from native fires was constantly to be seen. In all cases these signs of human existence were confined to the neighbourhood of the sea …

190 At [668], French J noted that pastoral companies began operating in the southern Kimberley near present-day Broome in the 1860s. By 1883, there was sufficient activity in the region for Broome and Derby to be proclaimed as towns. At [670], French J noted that in 1908, an Aborigines Inspector recorded that there were 5 pastoral stations between Broome and Cygnet Bay. Three of these collectively employed on a permanent basis 43 Aboriginal people, and supported a further 13 “indigents”. However, by about 1930 most of that land had become mission grants or reserve land for the use and benefit of Aboriginal people.

191 According to Dr Skyring’s report, the first European settlements in the application areas were pearling camps along the coast. Pearl shell was first found on the north west coast in 1861. The first documented account of encounters between colonists and Aboriginal people in the mid-Dampier Peninsula was Alexander Forrest’s 1879 land expedition from south of Roebuck Bay to Beagle Bay. By that time, Beagle Bay had become a ‘lay-up’ camp for the pearl luggers, and some Aboriginal men Forrest met on his expedition spoke some broken English, and indicated that they had been out to sea with the pearlers. Forrest also recorded that colonists were at that time exploiting the guano deposits on the Lacepede Islands.

192 Dr Skyring noted that the pearling industry was “corrupt and violent, and rife with allegations that Aboriginal divers laboured under the same conditions as slavery”. She then quoted from a 1915 history of the region written by Joseph Sykes Battye:

During the years 1875, 1876 and 1879, pearling yielded a rich result notwithstanding the many disastrous storms and the strict regulations made by the government concerning the employment of aborigines and Malays as divers. That these regulations were necessary is evident from the instances of cruelty and ill-treatment that were recorded in the newspapers. The trade seems to have had the effect of brutalising those connected with it, and though pearlers were compelled by Act and regulations to observe certain conditions in their treatment of divers, the conditions appear to have been honoured in the breach rather than in the observance. Supervision over a wide area at sea was necessarily difficult, and it was then easily possible for a disreputable trader to treat his divers as slaves, and to work them almost to the point of death during the twelve month’s engagement which the Act allowed.

Dr Skyring further noted that recruitment of Aboriginal labour included coerced labour and kidnap. Aboriginal women and girls were also kidnapped to work both as divers and as sex slaves for the pearlers.

193 By the 1890s, the role of Aboriginal men in the pearling industry had changed. Thursday Island pearlers had brought with them indentured crews from Southeast Asia and Japan who were competent at “dress diving”, thus displacing the Aboriginal “skin divers” who dived without protective gear. Aboriginal people continued to be employed in the shore-based aspects of pearling, such as shelling and packing. Despite attempts by white authorities to prevent interaction between the predominantly Asian pearl crews and Aboriginal people along the Dampier Peninsula coast, widespread trade developed between the two groups during this period. Dr Skyring described the trade as follows:

116. … The trade included Aboriginal people exchanging fish and seafood for goods from Asian pearling workers, as well as finding and carting wood and water for the pearling crews in exchange for food such as rice, and other goods like tobacco and liquor. Some of the trade with the Asian pearling workers involved Aboriginal women exchanging sex for clothing, jewellery and food … nearly all of the records from this period were created by white men in positions of authority, usually police or representatives of the Aborigines Department, and they always described interaction between Aboriginal women and Asian men as ‘immoral’. The white authors of the historical accounts labelled Asian men as a ‘contaminating’ influence. From this perspective they regarded any interaction as bad and something which should be prevented. Even though the historical record indicated there were permanent relationships between Aboriginal women and Asian men, with Asian men supporting their Aboriginal families, white commentators nearly always described such relationships as prostitution.

Dr Skyring noted that the white Australian authorities, without exception, condemned the trade between local Aboriginal people and the Asian crewmen. Police patrols were regularly dispatched up the coast of the Dampier Peninsula to disrupt the barter trade. Some of those patrols forcibly moved Aboriginal people away from coastal creeks, including by slaughtering Aboriginal dogs or threatening Aboriginal people with gaol. Despite this, the coastal trade continued into the twentieth century, with one constable noting in 1903 that Aboriginal people would leave the missions that had been established in Beagle Bay and Disaster Bay to camp near the luggers because they got better rations from the pearling crewmen than from the missionaries.

194 The arrival of Christian missionaries on the Dampier Peninsula would eventually have an enormous affect on the lives of the Aboriginal people in the region, including a direct affect on the families of the Aboriginal witnesses in these proceedings.