FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meriton Property Services Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1305

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | MERITON PROPERTY SERVICES PTY LTD (ACN 115 511 281) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for hearing as to remedies.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 TripAdvisor, Inc (TripAdvisor) operates an online travel site comprising several regional websites. This proceeding concerns the Australian regional website with the website address “www.tripadvisor.com.au” (the TripAdvisor website).

2 Consumers may post reviews of accommodation properties on the TripAdvisor website via a TripAdvisor account or a Facebook account. Additionally, as discussed below, consumers who have stayed at a hotel or other accommodation may be invited by email to leave a review.

3 A consumer review consists of an overall rating out of five, a title for the review, and a written review of a minimum of 100 characters. Reviews are posted on a page of the TripAdvisor website dedicated to the relevant property, with the most recently submitted reviews generally appearing first. TripAdvisor gives an overall rating (out of five) for each property. Although these are displayed as circles or bubbles, for ease of expression I will refer to these as ‘stars’ in these reasons. Thus a property may be rated one-star, two-star, etc, with five-star being the best rating. The TripAdvisor website also ranks all the properties of a given type in a particular geographical area (eg, 1 out of 54, 2 out of 54, etc). TripAdvisor uses an algorithm to rate and rank the properties, based on the quality, recency and quantity of reviews.

4 TripAdvisor offers a service to accommodation providers called “Review Express”. This service allows participating accommodation providers to send an email (through TripAdvisor) to guests who have stayed at a property inviting those guests to post a review of their stay on TripAdvisor. The accommodation provider provides the email addresses of its guests to TripAdvisor, and TripAdvisor sends email invitations to those guests on behalf of the accommodation provider. The email invitation provides a simple and streamlined mechanism for guests to post a review. The evidence indicates that using Review Express substantially increases the number of reviews about a property.

5 The respondent (Meriton) conducts a business of offering serviced apartment accommodation at (at least) 13 properties in Queensland and New South Wales. These properties appear on the TripAdvisor website. During the period November 2014 to October 2015 (the relevant period), Meriton participated in the Review Express service offered by TripAdvisor. On a weekly basis, Meriton provided TripAdvisor with the email addresses of guests who had stayed at its properties and TripAdvisor sent email invitations to these guests to post a review. However, rather than sending TripAdvisor the email addresses of all guests who had stayed at its properties (other than those who had requested that their details not be provided), Meriton adopted the following two practices:

(a) The first practice was to add the letters “MSA” (which stand for Meriton Serviced Apartments) to the front of the email addresses of certain guests. This rendered the email address invalid. This practice was applied to guests who had made a complaint or were otherwise considered likely to have had a negative experience at a Meriton property. I will refer to this practice as the MSA-masking practice.

(b) The second practice was to withhold from TripAdvisor the email addresses of all the guests who had stayed at a property during a period of time when there had been a major service disruption (such as the lifts not working, no hot water, etc). I will refer to this practice as the bulk withholding practice.

6 The effect of both practices was the same: the guest or guests did not receive an email invitation to post a review on TripAdvisor through the Review Express system. In the case of the MSA-masking practice, the email sent by TripAdvisor to the guest was not received because the email address was invalid. In the case of the bulk withholding practice, TripAdvisor did not receive the group of email addresses and so no emails were sent to those guests.

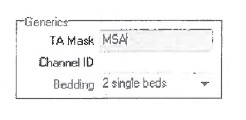

7 Towards the end of the relevant period, the method of masking the email addresses of individual guests changed. With the introduction of a new property management system (the software used to manage guest bookings and accounts), a field called “TA Mask” was created, and the letters “MSA” could be inserted into this field. In such cases, the email address of the guest was automatically not selected for provision to TripAdvisor. I will refer to this also as the MSA-masking practice in these reasons.

8 The practices were engaged in deliberately and systematically by Meriton during the relevant period. Front line staff were instructed to add the letters “MSA” to the email address of any guest who complained. This practice was standard across the organisation and, from January 2015, was reflected in Meriton’s standard operating procedure for checking out a guest. In relation to the bulk withholding practice, hotel managers would request that all email addresses be withheld for a particular time period and the State Manager for the relevant State would decide, on a case by case basis, whether to withhold the email addresses. In the event, the practice was engaged in on many occasions during the relevant period.

9 These practices were contrary to TripAdvisor’s guidelines or rules for using Review Express, as appearing on the TripAdvisor website. Those guidelines stated that participating accommodation providers should ask all guests for permission to email them, and send Review Express emails to everyone who consents. Further, TripAdvisor stated on the website that selectively emailing guests who are most likely to write positive reviews was considered to be a fraudulent practice.

10 The applicant (the ACCC) alleges that by engaging in the conduct described above, Meriton contravened ss 18 and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Australian Consumer Law). Section 18(1) provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. Section 34 relevantly provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics or the suitability for their purpose of any services.

11 Meriton essentially accepts that it engaged in the practices described above and that it ought not to have done so. Meriton also accepts that the practices were carried out for the purpose of preventing certain guests from receiving an invitation to review Meriton properties via Review Express, with the intention of reducing the likelihood that those guests would leave a review.

12 However, Meriton disputes that the practices had the effect, or the likely effect, alleged by the ACCC. In brief terms, the ACCC alleges that the practices had the effect, or likely effect, of reducing the number of recent negative reviews and that, by doing so, Meriton: improved (or was likely to have improved) the relative number of favourable compared to unfavourable reviews; and/or improved or maintained (or was likely to have improved or maintained) the ratings or rankings of Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website. The ACCC alleges that Meriton thereby created (or was likely to have created) a more positive or favourable impression of the standard, quality or suitability of its accommodation services. Meriton submits that the ACCC has not established that the practices had this effect or likely effect.

13 In my view, for the reasons that follow, the impugned practices had the effect of reducing the number of negative reviews of the Meriton properties appearing on the TripAdvisor website. The impugned practices also had the effect of improving the relative number of favourable reviews compared to unfavourable reviews of the Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website. I do not think it is established that the impugned practices affected the rating of the properties. However, at least in some cases, the impugned practices affected the ranking of the Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website. In summary, I find that the MSA-masking practice and the bulk withholding practice created a more positive or favourable impression of the quality or amenity of the Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website.

14 Further, for the reasons that follow, I consider that Meriton engaged in conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law. I also consider that Meriton engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the characteristics and the suitability for their purpose of the accommodation services provided by Meriton.

Procedural matters

15 The proceeding was commenced by originating application. By this document, the ACCC seeks: declaratory relief under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth); orders for injunctive relief under s 232 of the Australian Consumer Law; disclosure orders, corrective publication orders and orders requiring Meriton to implement a compliance program under s 246 of the Australian Consumer Law; orders for pecuniary penalties under s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law; and costs.

16 The ACCC’s case is set out in an amended concise statement (the concise statement). Meriton’s response is contained in its response to the amended concise statement (the concise response). The concise statement refers to Meriton conducting a business, in trade or commerce, of offering serviced apartment accommodation at properties in at least 13 locations in Queensland and New South Wales (defined as the “Meriton properties”).

17 The concise statement includes a description of the TripAdvisor website and the Review Express service. In response, Meriton accepts that TripAdvisor provided a website broadly as described in the concise statement during the relevant period and that it included reviews of properties operated by Meriton. However, Meriton states that it is not privy to the structure or organisation of the TripAdvisor website, does not have access to the algorithms or methods of assessment it operates or applies, and cannot admit the particular matters of fact alleged by the ACCC.

18 The ACCC alleges, in [14] of the concise statement, that during the relevant period, Meriton identified guests whom it considered likely to have had a negative experience at a Meriton property or who, during the course of their stay, had made a complaint, and who Meriton considered likely to submit a negative review to TripAdvisor about a Meriton property. At [15] of the concise statement, the ACCC alleges:

When providing the set of consumer email addresses to TripAdvisor for the purpose of the Review Express service, Meriton deliberately “masked” the email addresses of these guests (the masking practice) by:

(a) inserting the letters “MSA” at the front of the guest’s email address (or in the relevant area of Meriton’s booking system) before using the Review Express service, so that the email address would be invalid and the guest would not receive the Review Express email; or

(b) failing to send to TripAdvisor (when using the Review Express service) email addresses for guests who had stayed at a Meriton property during a period when the property had been adversely affected by an infrastructure or essential service failure, or by some other incident,

so that these guests would not be invited by TripAdvisor to submit a review via Review Express.

19 Although the ACCC’s concise statement uses the label “masking practice” to refer to both practices described in the above paragraph, as set out above I will use the expressions “MSA-masking practice” and “bulk withholding practice” to describe the two practices.

20 The ACCC gives examples of the masking practice in [16] of the concise statement and alleges, in [17], that Meriton’s employees implemented the masking practice with the knowledge, and at the direction, of Meriton’s senior management. It is alleged, in [19], that Meriton deliberately implemented the masking practice with the intention of reducing the likelihood of guests submitting negative reviews of Meriton properties to TripAdvisor, and improving or maintaining the rating of Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website. In [20] of the concise statement, the ACCC alleges:

The masking practice had the effect, or likely effect, of reducing the number of recent negative reviews of the Meriton properties submitted to TripAdvisor because consumers who had been identified as likely to give a negative review and who were subject to the masking practice were not contacted by TripAdvisor. This:

(a) improved, or was likely to improve, the relative number of favourable reviews compared to unfavourable reviews of Meriton properties that would have otherwise been posted; and/or

(b) improved or maintained, or was likely to improve or maintain, TripAdvisor ratings of Meriton properties,

and thereby created, or was likely to create, a more positive or favourable impression of the standard, quality or suitability of accommodation services provided by Meriton properties on consumers who used the TripAdvisor website to find suitable accommodation.

21 Although [19] and [20] of the concise statement use the expression “rating” and not “ranking”, the case was conducted on the basis that these allegations concern both rating and ranking (as described earlier in these reasons).

22 The ACCC alleges, in [23] of the concise statement, that by implementing the masking practice, Meriton engaged in conduct that was:

(a) misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law; and/or

(b) liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics and/or suitability for their purpose of the accommodation services at the Meriton apartments in contravention of s 34 of the Australian Consumer Law.

23 It is also alleged, in [24], that as a result of Meriton’s conduct in implementing the masking practice, consumers who accessed the pages of the TripAdvisor website dedicated to the Meriton properties for the purpose of evaluating, comparing and choosing accommodation during the relevant period, were misled or were likely or liable to be misled about: the nature, characteristics and/or suitability of the Meriton properties for their purposes; and the nature, characteristics and/or suitability of the Meriton properties in comparison to competing accommodation providers.

24 In its concise response, Meriton states that at all relevant times Meriton encouraged all guests at its properties to post reviews on the TripAdvisor website by, among other steps, displaying information about the website in all guest rooms, at its reception desks and check-in facilities, and in ‘flyers’ provided to guests.

25 In its concise response, Meriton also states that, at a date prior to the relevant period, for reasons unconnected with TripAdvisor, Meriton introduced a practice of deliberately “masking” email addresses by adding the letters “MSA” to those email addresses with the intention and effect that users of those email addresses would not receive automated emails from Meriton or anyone else to whom Meriton provided those email addresses, while permitting specific emails to be sent to them by removing the additional letters at the time of sending. Meriton states that the reasons for instituting this practice included:

(a) Where the guest had requested that they not be included in automated emails or that their addresses not be provided to third parties. Such requests were sometimes made en bloc (for example, by the New South Wales Police Force, or by film and television companies booking rooms on behalf of a number of participants in a ‘shoot’) and sometimes individually.

(b) Where the email address associated with the booking was not that of the guest, for example where a travel agent or a person organising a wedding or other function booked multiple rooms for different guests.

(c) Where a guest had been the subject of complaints of anti-social behaviour and had been asked to leave or told they would not be invited to return to the property for future stays. Meriton did not wish such guests to receive advertising or special offers in relation to its accommodation.

26 In [7]-[9] of its concise response, Meriton states as follows in response to the ACCC’s case:

7. During the relevant period Meriton did seek to identify guests whom it considered likely to have had a negative experience at a Meriton property or who, during the course of their stay, had made a complaint. It did so for the purposes of improving customer service and responding to those negative experiences and complaints and it did so respond.

8. There were occasions during the relevant period when members of staff of the Respondent applied the masking practice or invited their colleagues to apply it for purposes other than those for which it had been established including for the purpose of preventing the guest receiving a further invitation to review the property via TripAdvisor’s review express automated email.

9. The conduct identified in paragraph 8 did not have the effect or the likely effect of communicating any misleading representation to any consumer or of making any false representation concerning the standard, quality or suitability of accommodation services provided by Meriton.

27 In response to [15] of the ACCC’s concise statement, Meriton states:

19. In answer to paragraph 15 the Respondent repeats paragraphs 6 to 9 above and otherwise:

19.1 admits that it inserted the letters “msa” at the front of some guests emails (or in the relevant area of Meriton’s booking system) during the relevant period;

19.2 [a]dmits that some such email addresses with the letters ‘msa’ added were among those sent to TripAdvisor as part of its Review Express process;

19.3 admits that on some occasions it did not send email addresses to TripAdvisor in respect of some guests which had stayed at a Meriton property including some who had stayed during a period when the property had been adversely [affected] by an infrastructure or essential service failure.

The Respondent otherwise denies paragraph 15.

28 Meriton admits that staff who added the letters “MSA” to the email addresses of some guests were likely to have done so within the scope of their actual or apparent authority and that such conduct was engaged in by Meriton for the purposes of s 139B(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act.

29 Meriton denies the allegations in [20] of the concise statement. Meriton also states as follows at [27]:

The Respondent denies that as a result of its conduct in the relevant period that consumers who accessed the pages of the TripAdvisor website were misled or likely or liable to be misled about the nature, characteristics and/or suitability of the Meriton properties for their purposes and the nature, characteristics and/or suitability of the Meriton properties in comparison to competing providers. Further, the Respondent denies that the allegations in paragraphs 23 and 24 are capable of giving rise to liability on the part of the Respondent under ss 18 and/or 34 of the ACL.

30 The proceeding was set down for hearing on liability. Although the proceeding was commenced in the Victoria District Registry of the Court, following an oral application by Meriton at a case management hearing, I decided that the trial should take place in Sydney.

31 In its outline of opening submissions, Meriton stated that it “accepts that it did engage in both forms of conduct alleged (masking and non-forwarding of groups of email addresses) – and that it ought not to have done so”. The outline stated: “Meriton also accepts that both the practices of masking and non-forwarding were done for the purpose of preventing the guest from receiving a further invitation to review the property via TripAdvisor’s Review Express automated email … and that it was done with the intention of reducing the likelihood that the owners of those email addresses would leave a review”. Meriton also asked the Court to note its “commitment not to repeat the conduct”.

The hearing

32 At the hearing, the ACCC led evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Gerard O’Shaughnessy, an Assistant Director employed by the ACCC. Mr O’Shaughnessy’s affidavit evidence included screen captures of the TripAdvisor website with information about Review Express and the ranking of properties.

(b) Laura Elliott, a solicitor employed by the ACCC’s solicitors. Ms Elliott prepared two affidavits. Her first affidavit included screen captures of reviews that had been posted about Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website. Her second affidavit included screen captures from the Booking.com website, and further screen captures of reviews on the TripAdvisor website.

(c) Professor Edward C Malthouse, an expert witness. Professor Malthouse is the Theodore R and Annie Laurie Sills Professor of Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University, Illinois, United States of America. He prepared two reports. His first report dealt with, among other things: the impact of online reviews on purchasing decisions; the effect of automatic email invitations to post an online review; the likely effect (on matters such as the number of positive reviews, and rating) of Meriton using Review Express in accordance with its terms; and the likely effect (on such matters) of the masking practice alleged by the ACCC. Professor Malthouse prepared a second report, which was responsive to a report of Christopher Emmins, an expert called by Meriton.

33 Meriton led evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Carol Nazha, an employee of Meriton with responsibility, during the relevant period, for dealing with customer feedback (including feedback received through online reviews). Ms Nazha was first employed by Meriton in May 2014 as the Administration Co-ordinator. In December 2014, the title of that role was changed to Service Ambassador. In June or July 2015, she was promoted to the position of Training Co-ordinator (training employees on customer service), being a role in the Human Resources department. Although Belinda Adams became the Online Reputation Supervisor at this time, Ms Nazha continued to oversee TripAdvisor until the end of October 2015. Subsequently, Ms Nazha became the Talent and Culture Officer for the Meriton group of companies (the Meriton group).

(b) Albert Chan, the Operations Manager – New South Wales for the serviced apartments division of the Meriton group, a position he has held since June 2014.

(c) Christopher Emmins, an expert witness. Mr Emmins is a consultant based in the United Kingdom who specialises in the investigation, verification and resolution of issues regarding the factual content of internet sites. Mr Emmins prepared two affidavits, each annexing a report. Mr Emmins’s first report, in broad terms, dealt with the effects or likely effects of Meriton’s use of Review Express and its implementation of masking practices. Mr Emmins’s second affidavit and report sought to address certain issues that had been raised by the ACCC in relation to his first report at an interlocutory hearing during the week before the commencement of the trial.

34 Each of the above witnesses was cross-examined. Mr O’Shaughnessy and Ms Elliott gave evidence by video-link from Melbourne. The other witnesses gave evidence in person in Sydney.

35 I make the following preliminary observations about the evidence of the witnesses:

(a) Mr O’Shaughnessy’s evidence was of a confined nature. There was no cross-examination as to credit and I accept his evidence.

(b) Ms Elliott’s evidence was also of a confined nature. Again, there was no cross-examination as to credit and I accept her evidence.

(c) Professor Malthouse impressed me as a truly independent witness with a thorough and reasoned explanation for his opinions. He made appropriate concessions during cross-examination and presented as a witness who was endeavouring to assist the Court. I will consider his evidence further in the context of the specific issues discussed below.

(d) Ms Nazha made significant concessions during the course of cross-examination, which enhanced the credibility of her evidence. Her responses to questions during her oral evidence appeared to be honestly given. I generally accept her evidence.

(e) Mr Chan at times displayed reluctance in answering questions put to him during cross-examination. On some occasions, questions had to be put to him several times before he answered them. However, Mr Chan did make some significant concessions during cross-examination. To the extent that there were differences between Mr Chan’s affidavit evidence and oral evidence, I generally prefer his oral evidence. To the extent that there were differences between Ms Nazha’s evidence and that of Mr Chan, I generally prefer Ms Nazha’s evidence. I will consider whether to accept Mr Chan’s evidence in the context of considering specific factual issues, later in these reasons.

(f) Mr Emmins did not detail some aspects of his research (either in his reports or in his notebook) making it difficult to test some of his conclusions. He did not keep a contemporaneous copy (whether electronic or hard copy) of the website pages or reviews he examined in the course of his research, again making it difficult to test some of his conclusions. During cross-examination, he was taken to drafts of his first report and to correspondence he exchanged with Meriton’s in-house counsel in the course of preparing that report. In a number of instances, substantial matters that had been included in drafts of the report were taken out before the report was finalised. Although he explained some of these changes on the basis that he was cautioned by Meriton’s in-house counsel not to be seen as attacking TripAdvisor, this did not seem to explain all of the changes. Some aspects of the correspondence suggest he may not fully have appreciated the independence required of an expert witness. On the other hand, during the course of cross-examination Mr Emmins made significant concessions and conveyed an understanding of the independence required of an expert witness. I will consider his evidence further in the context of the specific issues set out below.

36 It is convenient to note at this point that Meriton did not call Matthew Thomas, who was Meriton’s National Manager during the relevant period and is now the General Manager of Meriton and a director of the Meriton group, to give evidence. The ACCC submits that inferences should be drawn in respect of Mr Thomas’s unexplained absence in accordance with the principles in Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298. I will deal with this issue later in these reasons.

Evidentiary rulings

37 Two evidentiary issues were not resolved during the trial and need to be dealt with in this judgment. I will deal with each in turn.

38 The first issue concerns certain documents in the Court Book that were not tendered during the hearing. The question is whether, as contended for by Meriton, they should be admitted into evidence. At the conclusion of the trial it was arranged that the parties would prepare and provide to the Court a list of the documents in the Court Book that had not gone into evidence. Subsequently, by email dated 29 June 2017, the ACCC’s solicitors provided a copy of the Court Book index in which they had identified in red highlighting the documents that the ACCC considered could be removed from the Court’s copy of the Court Book. However, it was also indicated that Meriton considered that certain additional documents should be retained in the Court’s version of the Court Book. Subsequently, by email of the same date, Meriton identified the documents that it considered should be included in evidence “as they either complete the included tabs or because reference was made to these documents in the evidence either explicitly or implicitly”. The relevant tab numbers in the Court Book were: 15, 19, 27, 61, 76, 86, 92, 113, 121, 123, 132, 138, 148, 151, 154 and 155. (Tab 142 is not included in this list as it went into evidence by agreement between the parties.) Given the difference of position between the parties, I made orders for each party to file and serve a short submission regarding: whether Meriton should be granted leave to re-open its case to tender the documents set out in Meriton’s email dated 29 June 2017; and, if so, whether the documents should be admitted into evidence. Having considered the submissions filed by the parties, I consider that each of these documents should be admitted into evidence (as a new exhibit, namely exhibit R14) on the basis that they were included in the ACCC’s tender bundle and there was perhaps some ambiguity during the trial as to whether such documents would go into evidence if Meriton wanted to rely on them (even if the ACCC did not). To the extent that leave to re-open is required, I would grant that leave. However, in circumstances where there was no witness evidence about these documents, the weight to be given to them may be limited. I also note that none of these documents was referred to in the submissions.

39 The second issue concerns a number of reports obtained by Meriton from a subscription service known as “TrustYou” (the TrustYou Reports). TrustYou is a service that collects and analyses guest reviews of accommodation on the internet. During the trial, objection was taken by the ACCC, on the ground of hearsay, to the admission into evidence of the TrustYou Reports. Meriton contended that the reports should be admitted under the business records exception to the hearsay rule in s 69 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). This was contested. In the circumstances, for practical reasons, so as not to hold up the trial, I provisionally admitted the TrustYou Reports, and the evidence based on those reports, and said that I would reach a final view as to admissibility and weight in the judgment. The ACCC subsequently indicated, in the course of closing submissions, that it sought the exclusion of the evidence under s 135 of the Evidence Act.

40 In relation to the TrustYou Reports, which are annexures CN-4 and CN-5 to Ms Nazha’s second affidavit, Ms Nazha gave the following evidence (which I accept):

(a) In her second affidavit, Ms Nazha stated that Meriton is a “subscriber to a computer system which is a feedback platform known as ‘TrustYou’”, and that TrustYou collects and analyses guest reviews, surveys and social posts from all across the web every week and provides subscribers with access to a program that allows the subscriber to view data analytics that “provide feedback as to what guests are saying in relation to the subscriber’s hotel”. She stated that: the person who originally subscribed to TrustYou on behalf of Meriton was Codie Beard; although Mr Beard is no longer working at Meriton, his Meriton email address was still used to log in to the system; and as a result, reports generated on Meriton’s account state that they were “[g]enerated by Codie Beard” (when in fact this was not the case).

(b) Ms Nazha stated in that affidavit that, on 3 May 2017, she caused a search to be made on Meriton’s TrustYou account for a report (referred to as a “dashboard”) on guest feedback across the web throughout the period November 2014 to October 2015 in relation to six particular Meriton serviced apartment properties, namely those located at: Bondi Junction; Campbell Street, Sydney; Danks Street, Waterloo; Parramatta; Pitt Street, Sydney; and World Tower. She stated that a report was generated and printed by her in relation to each individual property (being the reports comprising annexure CN-4). In cross-examination, Ms Nazha said that a dashboard was a collation of the online guest feedback that Meriton had received, including performance scores, and that it was a combination of material from Booking.com, TripAdvisor, Facebook, and “basically anything online that has our feedback on it”. She said that she exported the property dashboards for each of the hotels identified in her affidavit, printed them, and gave them to Meriton’s in-house counsel. Ms Nazha said that she did this at the request of Meriton’s in-house counsel, and that they asked her to do it “[f]or the court case” (which I take to be a reference to this proceeding).

(c) Ms Nazha stated in her second affidavit that, on 10 May 2017, she caused a further search to be made on Meriton’s TrustYou account, in order to generate a report on guest feedback across the web throughout the period November 2014 to October 2015 in relation to the Meriton serviced apartment at Kent Street, Sydney. This report was annexure CN-5 to her affidavit.

(d) Ms Nazha said in cross-examination that she first heard of TrustYou in early 2016.

41 The documents that comprise annexures CN-4 and CN-5 to Ms Nazha’s second affidavit also appear under tab 10 of the documents accompanying Mr Emmins’s first report. In this report, Mr Emmins stated that he was familiar with TrustYou and that it was an industry standard ‘big data’ source that provides analytical information to hotel businesses on the online reviews of hotels that are published on multiple websites. He stated that he regarded the data from TrustYou as being “accurate, expert and reliable”. Mr Emmins was not challenged on this evidence, and Professor Malthouse (who made comments about the TrustYou Reports in his second report) did not suggest otherwise. I therefore accept this evidence of Mr Emmins regarding TrustYou.

42 It is relevant to note the way in which Meriton seeks to rely on the TrustYou Reports. The reports were relied on by Mr Emmins in sections 8, 9, 10 and 11 of his first report essentially to support the proposition that there was significant consistency during the relevant period between the volume of reviews posted, and the ratings, on Booking.com and the TripAdvisor website in relation to three properties at or about the times of certain major service disruptions referred to in the concise statement. Mr Emmins expressed the opinion that, given that there could have been no interference with the Booking.com results (in the sense of the masking practices alleged by the ACCC), this indicates that the actions by Meriton employees did not discernibly affect review volume or ratings. Mr Emmins relied on the TrustYou dashboard reports for Meriton’s Bondi Junction, Kent Street and Pitt Street properties. There is a dashboard report for each of these properties. Mr Emmins principally relied on information contained on the first and second pages of each report. These pages contain two graphs:

(a) The first graph, headed “Overall score”, provided a score for the particular Meriton property on Booking.com, TripAdvisor and other websites over the period of time covered by the report (the Overall Score Graph). For example, the score for Meriton’s Bondi Junction on TripAdvisor was about 90 for most of the period covered by the dashboard report. The evidence does not explain how the score was derived, but it appears open to infer (and I will proceed on the basis that) it is simply the rating on TripAdvisor converted to a score out of 100. Thus a rating of 4.5 out of 5 stars on TripAdvisor appears to have been converted to a score of 90. I note that in his second report, Professor Malthouse proceeded on the basis that the score reflected the rating. It is unclear whether the score is an average of the rating over a period of time (eg, for a month).

(b) The second graph, headed “New reviews”, dealt with the number of new reviews of the particular Meriton property, apparently on a month-by-month basis (see Professor Malthouse’s second report at [2.4]), on Booking.com, TripAdvisor and other websites (the New Reviews Graph). Although it is a little difficult, given the small size of the graph, to ascertain a precise number for each month on each website, the graph indicates, at least approximately, the number of new reviews of the property per month on each website.

43 Section 59(1) of the Evidence Act provides that evidence of a previous representation made by a person is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact that it can reasonably be supposed that the person intended to assert by the representation. Such a fact is, in Part 3.2 of the Act, referred to as an “asserted fact”: s 59(2). The expression “previous representation” is defined in the Dictionary for the Act as meaning a representation made otherwise than in the course of giving evidence in the proceeding in which evidence of the representation is sought to be adduced. The expression “representation” is in turn defined in the Dictionary as including (among other things) an express or implied representation (whether oral or in writing). Section 59 is considered not to apply to machine-generated information in respect of which there is no human input on the basis that it refers to a representation “made by a person”: see Odgers S, Uniform Evidence Law (12th ed, Thomson Reuters, 2016), [EA.59.150]; Heydon JD, Cross on Evidence (10th Aust ed, Lexis Nexis Butterworths, 2015), [35560].

44 There are a number of exceptions to the hearsay rule, including the business records exception in s 69 of the Evidence Act. Section 69 relevantly provides as follows:

(1) This section applies to a document that:

(a) either:

(i) is or forms part of the records belonging to or kept by a person, body or organisation in the course of, or for the purposes of, a business; or

(ii) at any time was or formed part of such a record; and

(b) contains a previous representation made or recorded in the document in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business.

(2) The hearsay rule does not apply to the document (so far as it contains the representation) if the representation was made:

(a) by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact; or

(b) on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply if the representation:

(a) was prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian or overseas proceeding; or

(b) was made in connection with an investigation relating or leading to a criminal proceeding.

45 In Roach v Page (No 27) [2003] NSWSC 1046, Sperling J said at [11]: “The thinking behind the section is clear enough. Things recorded or communicated in the course of the business and constituting or concerning business activities are likely to be correct. There is good reason for the courts to afford to such records the same kind of reliability as those engaged in business operations customarily do.” The word “kept” in s 69(1)(a) has been construed as meaning “retained or held”: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich (2005) 216 ALR 320 at [190]. In relation to s 69(1)(b), a representation may be made or recorded in a document for the purposes of a business, even though it is not made by an officer of the business: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd (No 1) (2012) 207 FCR 448 at [45]-[50]. In relation to s 69(3), it has been observed that it is an unusual use of language to refer to the “preparing” of a representation, but the intention is clear enough; the reference is to the person who prepared, formulated, shaped or framed the terms in which the representation was made; and this will typically, perhaps always, be or include the maker of the representation: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Advanced Medical Institute Pty Ltd (2005) 147 FCR 235 at [25]. Further, the person who “obtains” the representation is the person who seeks the representation or procures it to be made: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Advanced Medical Institute Pty Ltd at [26]-[27].

46 Section 135 of the Evidence Act provides that the Court may refuse to admit evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might: be unfairly prejudicial to a party; be misleading or confusing; or cause or result in undue waste of time.

47 Before addressing directly the application of these provisions, I make some further observations about the TrustYou Reports. There is no evidence about how TrustYou derived the figures that appear in the Overall Score Graph and the New Reviews Graph in each dashboard report. In all likelihood, a computer was utilised to obtain the relevant information from the internet, and an algorithm was used to determine the scores and the number of new reviews. Apart from programming the relevant software, there may have been no or very little human involvement in this process. Based on the way in which Mr Emmins relied on the TrustYou Reports, it would seem that the following facts are sought to be established: first, that the scores for the particular property on Booking.com and TripAdvisor during the period covered by the dashboard report were as set out in the Overall Score Graph; and, secondly, that the number of new reviews for the particular property on Booking.com and TripAdvisor for each month covered by the report were as set out in the New Reviews Graph.

48 It may be observed that the information in these graphs is quite rudimentary. It is merely the score for the property on Booking.com and TripAdvisor (among other online sites) over a period of time, and the number of new reviews of the property posted on the websites each month. It may also be observed that the information is closely concerned with the conduct of Meriton’s business. It is information of a type that could have been collected by a member of Meriton’s staff during the period covered by the report. Instead, as is no doubt increasingly common these days, Meriton subscribed (for a fee) to a service that collected the information and made it available to Meriton. Although on this occasion Ms Nazha accessed the TrustYou database and exported information for the period November 2014 to October 2015, it would have been open to Meriton to have accessed the database and exported comparable reports on a regular basis during the relevant period (and it may have done so).

49 With these matters in mind, I turn to the legislative provisions. Although there is no real issue between the parties that the TrustYou Reports contain hearsay representations within the meaning of s 59, it is necessary to examine briefly why this is the case. As discussed above, in all likelihood there was significant computer involvement in the collection of the data and generation of information in the two graphs. Nevertheless, there was at least some human input by way of guests posting reviews (including with their star rating of the property): see, by analogy, Hansen Beverage Co v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd (2008) 75 IPR 505; [2008] FCA 406 at [125] (although reversed on appeal, this does not affect the reasoning on this issue). Underlying the data in the graphs are previous representations by guests that they: had reviewed the property; and gave the property a particular rating. On this basis, the material in the graphs is prima facie inadmissible under the hearsay rule.

50 The question then is whether the TrustYou Reports fall within the business records exception in s 69. The TrustYou Reports were created by Ms Nazha accessing the subscription service and creating and exporting the reports. Given that each of the reports contained information concerning Meriton’s business, it may be inferred that they were retained by Meriton as part of the records of its business. In my view, each report forms part of the records kept by Meriton in the course of and for the purposes of its business. Accordingly, I consider the requirements of s 69(1)(a) to be satisfied. Section 69(1)(b) requires that the document “contains a previous representation made or recorded in the document in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business”. I consider that the previous representations (as identified in [49] above) were recorded in the reports for the purposes of Meriton’s business. Accordingly, the requirements of s 69(1)(b) are satisfied.

51 Section 69(2) provides that the hearsay rule does not apply to the document if the representation was made: (a) by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact; or (b) on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact. Here, the previous representations (as identified in [49] above) were made by the guests of Meriton’s properties, who had personal knowledge of the asserted facts. Accordingly, s 69(2) is satisfied.

52 Section 69(3) provides that subsection (2) does not apply if the representation was prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian proceeding. Importantly, the focus here is on the representation rather than the document. Although it is true that the TrustYou dashboard reports were created and exported by Ms Nazha for and in connection with an Australian proceeding (being this proceeding), the representations (as identified in [49] above) were not prepared or obtained for or in connection with the proceeding. They were obtained by TrustYou in advance of, and not in connection with, this proceeding.

53 For these reasons, I consider the TrustYou Reports to be admissible as business records pursuant to s 69.

54 It remains to consider s 135. As indicated above, I accept the unchallenged evidence that the data from TrustYou is “accurate, expert and reliable”. I have described, above, the nature of the material relied on by Mr Emmins in the TrustYou Reports. It is principally the information contained in the Overall Score Graph and the New Reviews Graph in the dashboards reports for the three properties he examines. While there are a number of difficulties with drawing conclusions from this data (as described in Professor Malthouse’s second report and discussed below), I consider these to be matters going to weight and to the evaluation of Mr Emmins’s opinions rather than admissibility. Taking these matters into account, I do not consider the probative value of the evidence to be substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might: be unfairly prejudicial to the ACCC; be misleading or confusing; or cause or result in undue waste of time. Accordingly, I do not exclude the evidence under s 135. It follows that I admit into evidence the TrustYou Reports and the evidence based on those reports.

Findings of fact

55 The following findings of fact are based on the affidavit evidence, oral evidence and documents admitted into evidence. I will deal separately, later in these reasons, with the question whether the impugned conduct had the effect alleged by the ACCC in [20] of the concise statement.

Meriton

56 During the relevant period, Meriton carried on a business of providing serviced apartment accommodation at (at least) 13 properties in New South Wales and Queensland. The expressions “serviced apartments” and “hotels” were used interchangeably in the evidence to describe the accommodation provided by Meriton at the properties, and I will similarly use the expressions interchangeably in these reasons.

57 Star Ratings Australia, an independent assessor that rates accommodation providers (hotels, motels, serviced apartments, caravan parks, etc) and provides accredited star ratings, assessed the Meriton properties in 2014. The evidence includes the assessment reports provided by Star Ratings Australia. For example, Meriton’s Broadbeach property was assessed as four stars (out of five). It is important to emphasise that the stars used in these assessment reports represent an independent assessment of the property against objective criteria. This is to be distinguished from the circles or bubbles (which I am referring to for ease of expression as ‘stars’) on the TripAdvisor website. In the latter case, the rating is produced by a TripAdvisor algorithm, based on customers’ online reviews of the property.

58 Mr Chan referred in his affidavit to the following Meriton properties that are identified in the concise statement:

(a) Bondi Junction;

(b) World Tower;

(c) Kent Street;

(d) Danks Street;

(e) Campbell Street;

(f) Pitt Street;

(g) Broadbeach; and

(h) Parramatta.

59 Mr Chan stated in his affidavit that, during the relevant period, the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of each of these properties did not deteriorate in any substantial or material respect.

60 Ms Nazha annexed to her second affidavit a document created from the business records of Meriton that identified how many reservations were made during the 2015 year and the method or channel by which they were made (eg, TripAdvisor, Meriton’s direct website, Expedia.com, Booking.com, etc). This table indicates the scale of Meriton’s business and the relative proportions of bookings made through different methods. For example, during the 2015 year, approximately 306,000 reservations were made. Of these, 94,315 were made through Meriton’s brand website and 138,977 were made through Booking.com.

The TripAdvisor website

61 TripAdvisor conducts an online travel site that assists consumers to choose (among other things) accommodation. Mr Chan accepted in cross-examination that the following statement reflected Meriton’s opinion about TripAdvisor: “It’s the world’s largest travel site, helping millions of visitors every month plan the perfect trip”.

62 The TripAdvisor website includes a page for each property, a rating for the property (out of five, including half stars), a ranking for the property (compared against all properties of the same type) in the geographical area, and reviews of the property (with the most recent reviews generally appearing first). Reviews include the reviewer’s rating for the property out of five stars (not including half stars). It appears that the reviewer has the option to rate the property, not only overall, but also with respect to particular aspects such as value, location, room quality and cleanliness. The reviews initially appear with only about four lines of text visible. The reviews can be ‘expanded’ (by clicking on “More”) to show the full text of each review. The reviews in evidence have a notation at the end to the following effect: “This review is the subjective opinion of a TripAdvisor member and not of TripAdvisor LLC.”

63 The evidence does not include a detailed description of the algorithms used by TripAdvisor to determine the rating and ranking of a property. However, an indication of the matters taken into account by the property ranking algorithm during the relevant period is provided by the following extracts from the TripAdvisor website, explaining a change to the algorithm made in early 2016.

64 The Frequently Asked Questions section of the TripAdvisor website, under the heading “Changes to the TripAdvisor Popularity Ranking Algorithm”, included the following statements:

Why We Changed the Popularity Ranking Algorithm

Over the past decade, the volume of reviews and opinions on TripAdvisor has increased exponentially – from six million in 2006 to over 350 million in 2016. Today, travellers are adding 200 new contributions to the site every minute.

Due to the speed at which travellers are sharing their experiences on TripAdvisor, we found instances where a newly listed property was able to skyrocket to the top of the rankings on relatively few 5-bubble reviews. We called these properties “fast-risers”. Over time, TripAdvisor travellers would submit more reviews on the fast-risers, causing them to settle into more stable, accurate rankings. Unfortunately, while this transition was happening, TripAdvisor consumers may not have been seeing the most accurate rankings for the destination. Fast-risers would temporarily enjoy higher positions before falling significantly in the rankings, and other businesses would appear lower than they would have otherwise.

To improve our site experience for travellers and businesses alike, we’ve enhanced our Popularity Ranking algorithm. The enhanced ranking results in a more accurate representation of a business’s performance over time. These changes were not undertaken lightly and were carefully designed and tested to improve our rankings algorithm in some very specific ways, while maintaining the accurate standings of existing properties with great reputations among TripAdvisor members.

…

How the Enhanced Popularity Ranking Algorithm Works

Our goal was to design an enhanced algorithm where a property settles into a stable ranking more quickly and avoids the fast-riser behaviour. The Popularity Ranking continues to be based on the quality, recency and quantity of reviews that a business receives from travellers. …

Quality

The bubble ratings provided by travellers as part of their reviews continue to be used to rank properties. All other things being equal, a property with more 4- and 5-bubble ratings will rank higher than a business with lower bubble ratings.

Recency

We believe that recent reviews are more valuable to our travellers than older reviews. They give a more accurate representation of the current experience at the property. To take this into account, we continue to give more consideration to fresh reviews over those that were written in the past. This means that reviews – even excellent ones – that are more dated will not count as much towards a property’s ranking as a review written last week. Even though these reviews do not have as much weight in the ranking, they are still visible to travellers in the Traveller Rating bar chart, in the overall bubble rating on each listing as well as in the review history.

Quantity

The number of reviews is a critical indicator to TripAdvisor travellers about a property. TripAdvisor consumers read multiple reviews to help form a balanced opinion on a business and tend to have more confidence in their decisions when they see agreement across a large set of fellow travellers’ reviews.

…

(Emphasis added.)

65 On the basis of the above description, it is to be inferred that, even before this change, and during the relevant period, the property ranking algorithm took into account the quality of reviews, the recency of reviews and the quantity of reviews in ranking properties in a particular geographical area. Although there was a change to the algorithm, the above extract (and in particular the emphasised words) indicates that these matters were already taken into account before the change. Although the evidence does not contain a description of the rating algorithm, I would infer that similar matters were taken into account in rating a property (that is, that the rating of properties was also based on the quality of the reviews, the recency of reviews and the quantity of reviews).

Descriptions of Meriton properties on the TripAdvisor website

66 Meriton provided descriptions of each of its properties to TripAdvisor for inclusion on the TripAdvisor website. During the relevant period, these descriptions were available for view on the website. Screenshots of these descriptions were annexed to Mr Chan’s affidavit. Mr Chan stated in the affidavit that, based on his own personal experience and observations of each of the properties, the descriptions of these properties were accurate and fair descriptions of the nature, characteristics and suitability of the properties during the relevant period.

Review Express

67 Central to this case is the service provided by TripAdvisor to accommodation providers known as Review Express. During the relevant period, the TripAdvisor website included a page headed “The complete Review Express guide”. This page included the following explanation of Review Express:

Looking for an easy way to get more reviews for your business? Try Review Express – the review collection tool that TripAdvisor created based on feedback from hospitality businesses like yours. It’s free for all types of properties, i.e. no Business Listings subscription or TripConnect™ campaign required.

With Review Express, you’ll create and send professional-looking e-mails that encourage guests to write reviews of your business. These e-mails can be customised with your property’s branding. There’s also a Review Express dashboard that provides in-depth analysis and tracking to help you fully optimise your campaigns.

On average, regular Review Express users see an uplift of 33% in the amount of TripAdvisor reviews for their property. Read on to learn how easy it is to start using Review Express for your business.

…

Send E-mail

In this step, add the e-mail addresses of the guests you’d like to reach. Have just a few addresses? Type them into the text box. If you have lots of e-mails to send, upload a spreadsheet of up to 1,000 e-mail addresses using the file upload box. Review Express will accept .CSV or .XLS files up to 5MB in size. If you’re sending e-mails to guests in different languages, be sure to set up a new message and upload just those addresses for that campaign.

Keep in mind, TripAdvisor takes fraud and privacy very seriously. The addresses you submit must belong to people who have visited your property and you must have permission to e-mail them. You cannot have a personal relationship with any of the recipients and they cannot be offered any incentives for reviews. Finally, avoid selectively e-mailing only the guests you believe will write positive reviews. Review Express e-mails should be consistently sent to all guests – properties are often happily surprised by the results.

Once you’ve added your recipients, review and click the three notices at the bottom of the page. Then, hit “Send”. Your e-mails will be sent within 24 hours. Reviews that you receive through Review Express will have a label indicating they were collected in partnership with your property.

…

(Emphasis added.)

68 As indicated in the last sentence of the above extract, reviews posted through Review Express have a label indicating that they were collected in partnership with the property. There are many examples in evidence of reviews that include the sentence, near the bottom of the review, “Review collected in partnership with this hotel”. It was common ground that this notation appears when a review was posted following an email invitation through Review Express. Immediately after this notation, an information symbol appears. If the consumer clicks on that symbol, the following statement appears: “This business uses tools provided by TripAdvisor (or one of its official Review Collection Partners) to encourage and collect guest reviews, including this one”.

69 During the relevant period, the TripAdvisor website included a page (located within the Help Centre) addressing the question: “What is considered fraud?” This page stated as follows:

Visitors to TripAdvisor have the expectation that the site will provide them with unbiased reviews and content for accommodations, attractions, restaurants and other venues. Travellers who wish to share their personal experiences with the TripAdvisor community provide this content.

TripAdvisor is committed to ensuring the integrity of the content it collects and provides to its global community of travellers and businesses.

Any attempts to mislead, influence or impersonate a traveller is considered fraudulent, and is subject to penalties. This may include but is not limited to:

- Attempts by an owner or agent of a property to boost the reputation of a business by:

• Writing a review for their own business, or for any property the reviewing party owns, manages, or has a financial interest in.

• Utilising any optimisation company, marketing organisation, or third party to submit reviews.

• Impersonating a competitor or a guest.

• Offering incentives in exchange for reviews, including discounts, upgrades or any special treatment.

• Asking friends or relatives to write positive reviews.

• Submitting reviews on behalf of guests.

• Copying comment cards and submitting them as traveller reviews.

• Selectively soliciting reviews (by e-mail, surveys or any other means) only from guests who have had a positive experience.

• Pressuring travellers to remove a negative review on TripAdvisor.

• Asking guests to remove their reviews in return for a discount or incentive.

• Prohibiting or discouraging guests from posting negative or critical reviews of their experience.

…

(Emphasis added.)

70 Further, during the relevant period, the TripAdvisor website included a page headed “9 common Review Express concerns”. The ninth of these dealt with selectivity:

Can I be selective and only send Review Express emails to guests who are likely to write positive reviews?

You should ask all guests for permission to email them, and send Review Express emails to everyone who consents. Selectively emailing guests who are most likely to write positive reviews is considered a fraudulent practice and may result in penalties for your property. For more information, click here. Keep in mind – properties are often surprised by the amount of positive feedback they receive … after all, the average TripAdvisor review rating is 4.12 bubbles out of 5.

(Emphasis added.)

Meriton’s participation in Review Express

71 It appears from the document discussed in the next paragraph below, that Meriton commenced its participation in Review Express in about August 2013.

72 In November 2014, TripAdvisor provided Meriton with a presentation on the performance of Review Express to date. This took the form of a PowerPoint presentation. The “Executive Summary” page stated:

Meriton has had a massive benefit from instituting a formal review collection program

• 65% more reviews per property per month

• 90% of properties saw overall rating

• 67% saw increase in overall ranking → 5 are #1 in their GEO

• 60% increase in page views per property per month

(Errors in original.)

73 The next page of the presentation was headed “Summary Activity to Date” and included figures for such matters as the total number of email invitations sent for each property, the “Click-Thru Rate” (which would appear to refer to the recipient clicking on the hyperlink in the email invitation), the number of reviews left through Review Express, the rank of the property at the start of the period (probably referring to the introduction of Review Express) and the rank at the end of the period (probably, about October 2014). In a number of cases, the rank had improved significantly. For example, Meriton World Tower had gone from a rank of “7 out of 188” to a rank of “3 out of 183”. The rank of each of the 13 Meriton properties identified in the presentation at the end of the period was as follows:

(a) Bondi Junction – 1 out of 9;

(b) World Tower – 3 out of 183;

(c) Pitt Street – 13 out of 183;

(d) Parramatta – 1 out of 10;

(e) Waterloo – 14 out of 183;

(f) Kent Street – 10 out of 183;

(g) Broadbeach – 2 out of 22;

(h) Southport – 1 out of 4;

(i) Campbell Street – 2 out of 183;

(j) Brisbane on Adelaide Street – 3 out of 160;

(k) Zetland, Sydney – 9 out of 183;

(l) Brisbane on Herschel Street – 1 out of 160; and

(m) North Ryde – 1 out of 6.

74 A slide headed “Program has delivered more reviews, at higher average ratings” indicates that the program launch (probably when Meriton started using Review Express) was in August 2013. The next slide, headed “Properties are generating on average more reviews per month due to Review Express”, indicates that there were (on average) 23 reviews per month before and 55 reviews per month after. I take it that these statements refer to before and after Meriton started using Review Express. It is to be inferred that participation in Review Express substantially increased the number of reviews on TripAdvisor of Meriton’s properties.

75 During the relevant period, Meriton provided (or uploaded) email addresses to TripAdvisor for Review Express on a regular basis, approximately weekly.

Reviews of Meriton properties on TripAdvisor

76 Ms Nazha gave evidence (which I accept) that, during the relevant period, approximately 30 new reviews a day were posted on TripAdvisor in respect of the Meriton serviced apartments or hotels.

77 Mr Chan gave evidence (which I accept) that, from about October 2014 to October 2015, Meriton received approximately 52,000 online guest reviews in relation to its properties, and that TripAdvisor reviews accounted for 20% of these. On the basis of these figures, it seems that, from October 2014 to October 2015, Meriton received approximately 10,000 TripAdvisor reviews.

78 Mr Chan also gave evidence, which I accept, that the TripAdvisor reviews during that period had a reputation index of 92.8%. He explained that a reputation index is a percentage rating compiled by “ReviewPro” (a commercial service) by a formula that analyses each review on TripAdvisor to summarise the effect of those reviews. Mr Chan said that he knew from his own observations that a reputation index from ReviewPro of 92.8% indicated a very high level of positive reviews.

79 Ms Nazha said in her first affidavit that: in her role as Administration Co-ordinator (subsequently, Service Ambassador) her responsibility was primarily to deal with customer feedback; and a large part of that feedback was received through online reviews, such as on the TripAdvisor website. Ms Nazha said that each morning she would log in to the business listing screen for Meriton on the TripAdvisor website and log the number of reviews received and the number of reviews yet to be responded to. She said that she would identify any negative reviews (which Ms Nazha said during cross-examination was a one, two or three-star review (out of five)), or any negative comments in positive reviews (ie, four or five-star reviews), and put the following procedure into effect. First, she would forward the negative review or the negative comment to the hotel manager of the relevant property and ask the manager to investigate the issues and seek to identify the relevant booking (ie, the guest) using internal clues within the review. She did this because part of her task was to respond to reviews via the TripAdvisor site. Next, Ms Nazha would ask the manager to investigate the cause of the complaint and respond to her. Ms Nazha stated that there is a facility for a hotel to respond to any review on TripAdvisor by posting a comment below the review. She stated that her invariable practice was to respond to every review of a Meriton property on TripAdvisor (this applied both to positive and negative reviews). Ms Nazha said during cross-examination that she did not herself contact guests directly (ie, by email or phone); this was something done by the hotel manager. Ms Nazha stated that when the hotel manager had spoken to a guest who had left a negative review, or made a negative comment in a positive review, the manager would report back to her and she would treat the matter as closed. I accept Ms Nazha’s evidence as set out in this paragraph.

80 The evidence includes a number of cases where Meriton (usually the hotel manager) contacted a guest who had left a negative review. In some of these cases the guest was offered compensation to address a matter about which they had complained in the review. In some cases, the guest was asked to, and agreed to, amend or remove the review.

81 Ms Nazha prepared a weekly report on activity on TripAdvisor, using a template that was already established when she joined Meriton. The report set out, for each property, matters such as the ranking, the total number of reviews, the overall distribution of positive and negative reviews, and any negative comments received over the course of the past week. This report was provided to management.

82 Ms Nazha said during cross-examination that sometimes reviews posted on TripAdvisor would breach TripAdvisor’s guidelines, for example if they were “hearsay”. She said (and I accept) that she would dispute the review with TripAdvisor and, in some cases, it would remove the review.

83 During the relevant period, Meriton received awards from TripAdvisor, a matter that it publicised on its own website. The evidence includes a page from the Meriton website with the heading “Australia’s Most Awarded Hotel Brand”, the date 21 January 2015, and a large TripAdvisor logo. The following text appears:

On Wednesday, six of Meriton Serviced Apartments’ 13 locations were recognised in the annual Travellers’ Choice awards from TripAdvisor, the world’s number one guest-review website. For the 13th year, TripAdvisor has highlighted the world’s top properties based on millions of traveller reviews.

Meriton Serviced Apartments properties won six spots in Australia’s Top 25 Hotels, and represent five of the South Pacific’s Top 25 Hotels, with Meriton Serviced Apartments World Tower, Campbell Street, North Ryde, Brisbane on Herschel Street, Brisbane on Adelaide Street and Southport all getting the nod – making Meriton the most awarded hotel brand in Australia.

…

84 Ms Nazha accepted during cross-examination that Meriton promoted itself by reference to the awards it had received from TripAdvisor.

The MSA-masking practice (up to August 2015)

85 Ms Nazha stated in her first affidavit that, when she joined Meriton (in May 2014), the company was already using Review Express to generate automatic emails to guests asking for their feedback.

86 Ms Nazha stated in that affidavit that, at the time she joined Meriton, it had an existing policy of sometimes adding the letters “MSA” to the beginning of the email address of some guests in Meriton’s booking records, for various reasons, to prevent automatic emails being received by the person. During cross-examination, Ms Nazha stated that Mr Beard (the Marketing Manager at Meriton) had said to her that the normal practice was to place the letters “MSA” in front of the email address of any guest who complained. Ms Nazha agreed that the email masking practice had been introduced before she started working at Meriton, and was well under way at the time she commenced. I accept Ms Nazha’s evidence as set out in this paragraph.

87 Ms Nazha stated in her first affidavit that, in her experience, the two most common reasons for adding the letters “MSA” were that the guest had complained, or that the guest was blacklisted, for example because he or she had been evicted from the hotel. However, in cross-examination, Ms Nazha accepted that overwhelmingly the most common reason for adding the letters “MSA” was because the guest had complained. Ms Nazha stated in her affidavit that she did see the letters added for other reasons, such as because the guest asked not to be contacted, but that these reasons were less common. I accept Ms Nazha’s oral evidence in preference to her affidavit evidence on this matter.

88 Ms Nazha stated in her first affidavit that adding the letters “MSA” to the email addresses of guests who had complained “was common knowledge and practice across all management and front line staff”. In cross-examination, she said that the task of putting the letters “MSA” in front of a guest’s email address (so as to invalidate it) was that of front line employees, such as guest service agents, the managers on duty, indeed, everyone who was checking the guests in and out. I accept Ms Nazha’s evidence as set out in this paragraph.

89 Ms Nazha indicated in her evidence during cross-examination that the MSA-masking practice was applied even in cases where a complaint had been resolved. She was asked why she considered it necessary to mask even where the issues had been resolved. She answered that she was “just following [her] instructions from [her] management team”. I accept this evidence.

90 Ms Nazha stated in her affidavit, in the context of having instructed staff to add the letters “MSA” to email addresses, that her intention was to comply with Meriton’s policy and “to reduce the likelihood that a review would appear that did not reflect the true quality of the service offered”. While I consider that Ms Nazha’s intention was to reduce the likelihood that a negative review would appear, I doubt that her thought process at the time included that such a review would not “reflect the true quality of the service offered”.

91 Ms Nazha accepted during cross-examination that her understanding was that the “MSA-masking policy” and the “bulk suppression of email policy” existed “to prevent, so far as possible, these guests being invited by TripAdvisor through the Review Express process to submit reviews”. She accepted that this was, to her knowledge, the understanding of everyone at Meriton. She said that the policies were not secret within Meriton.

92 On the basis of the evidence set out in [85]-[91] above, I find as follows.

(a) From at least May 2014, Meriton adopted a practice of masking the email addresses of guests who complained.

(b) The method of masking was to add the letters “MSA” to the beginning of a guest’s email address, thus invalidating it. (As discussed below, the method changed in about September 2015.) While the letters “MSA” were added in some other cases, overwhelmingly the most common reason was because the guest had complained.

(c) The practice was standard across the whole of the organisation. It was implemented by front line staff, ie, at the hotel level rather than at head office.

(d) The practice was adopted on the instructions of management.

(e) The effect of masking an email address by adding the letters “MSA” was that the email address was invalid. This meant that the guest would not receive an email invitation through Review Express to post a review on TripAdvisor.

(f) Meriton’s intention in adopting the practice was to reduce the likelihood of negative reviews being posted on TripAdvisor.

93 On 20 November 2014, Ms Nazha sent an email to all hotel managers in New South Wales, with the subject “Masking Emails”, as follows:

Hi Team,

In order to ensure complaints are not carried onto TripAdvisor, I strongly recommend that each property add a ‘Email MSA’d’ column in their duty log spreadsheet as seen attached (this is just an example).

Of course this won’t eliminate negative reviews completely, but at least it will streamline masking guest bookings more effectively and capture all guests who have recorded a complaint.

MSA Kent Street have recently implemented this showing great results with their reviews so I wanted to share it across all properties as well.

Any questions please don’t hesitate to ask.

(Emphasis added.)

94 Ms Nazha accepted in cross-examination that by “great results with their reviews” she meant far fewer negative reviews. In re-examination, Ms Nazha said (and I accept) that this was based on her own observation rather than research.

95 Attached to that email was a template spreadsheet headed “Handover – Follow up”, which included a column headed “Email MSA’d”. Ms Nazha said during cross-examination (and I accept) that: she did not prepare this spreadsheet; she noticed that the hotel at Kent Street was using it; and she raised this matter with Mr Chan, who suggested that she send it to all the hotel managers.

96 In January 2015, Meriton updated its standard operating procedure for check out. This document expressly referred to the masking of email addresses, as the third of nine steps to be carried out by front line staff, in the following terms:

Ask guest if they enjoyed their stay, if positive pass a Trip advisor feedback card to guest requesting them to post feedback online and if negative mask guest email by adding MSA to the beginning of guest email address and discuss concerns.

(Emphasis added.)

At the foot of this document, there is a space for staff members to sign. Above the space for the signature, the following statement appears: “I understand that should I not follow this standard correctly that disciplinary action will occur”.

97 Ms Nazha said in cross-examination (and I accept) that although the masking procedure was well under way at the time she joined Meriton in May 2014, it was not in writing before January 2015. I take it from this evidence that the inclusion of the above statement in the standard operating procedure for check out, in January 2015, merely formalised what had already been the standard practice for some time, including the whole of the relevant period for the purposes of this proceeding.

98 Ms Nazha said during cross-examination that when she was checking Meriton’s TripAdvisor reviews, and saw a review from Review Express, she would question why the email address had not been masked if the guest had reported the issue during their stay. Ms Nazha explained that she could tell if the review was from Review Express by the notation “Review collected in partnership with this hotel” at the bottom of the review. Ms Nazha said that she was told by Mr Chan, Mr Thomas and Mr Beard on numerous occasions that it was part of her job to follow up the failure to put the letters “MSA” in front of the guest’s email address in such cases. I accept Ms Nazha’s evidence as set out in this paragraph.

99 On 5 March 2015, the hotel manager for Kent Street sent an email to others at Meriton, copied to Ms Nazha, as follows:

Hi team,

Please be advised we have just received a new 3 star review this morning.

I believe I have found the booking and the details are (booked via TA):

…

Christina can you please check this room, I believe it would still have the old carpet.